Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

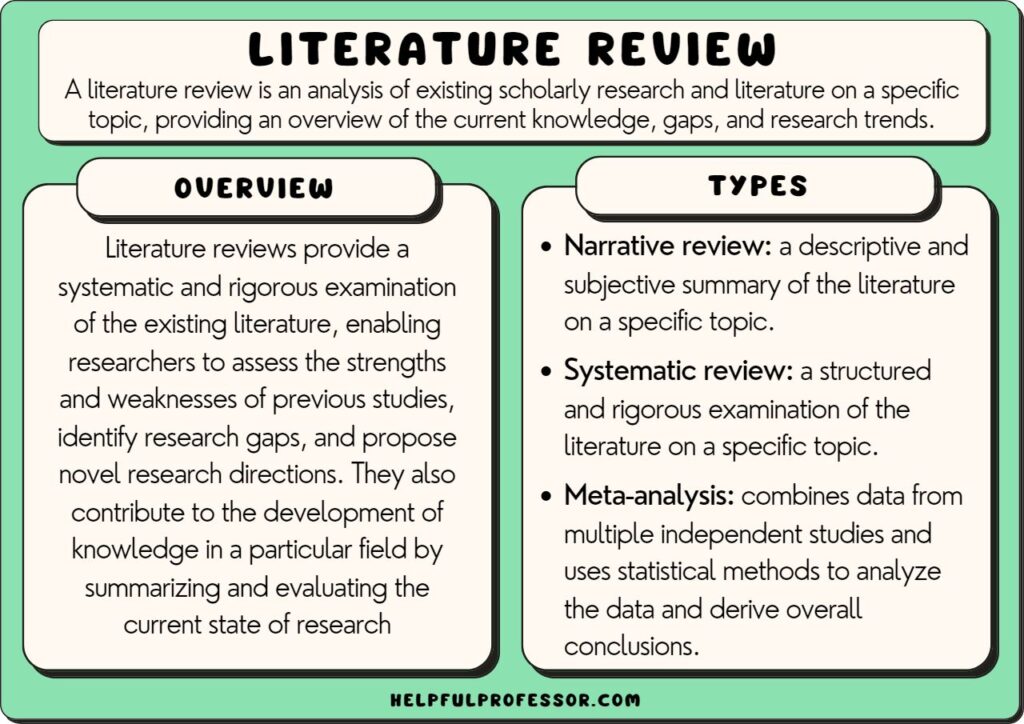

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, how paperpal’s research feature helps you develop and..., how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., how to write a successful book chapter for..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you..., how to write a hypothesis types and examples , measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students, why traditional editorial process needs an upgrade.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Literature Review Guide: Examples of Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- How to start?

- Search strategies and Databases

- Examples of Literature Reviews

- How to organise the review

- Library summary

- Emerald Infographic

All good quality journal articles will include a small Literature Review after the Introduction paragraph. It may not be called a Literature Review but gives you an idea of how one is created in miniature.

Sample Literature Reviews as part of a articles or Theses

- Sample Literature Review on Critical Thinking (Gwendolyn Reece, American University Library)

- Hackett, G and Melia, D . The hotel as the holiday/stay destination:trends and innovations. Presented at TRIC Conference, Belfast, Ireland- June 2012 and EuroCHRIE Conference

Links to sample Literature Reviews from other libraries

- Sample literature reviews from University of West Florida

Standalone Literature Reviews

- Attitudes towards the Disability in Ireland

- Martin, A., O'Connor-Fenelon, M. and Lyons, R. (2010). Non-verbal communication between nurses and people with an intellectual disability: A review of the literature. Journal of Intellectual Diabilities, 14(4), 303-314.

Irish Theses

- Phillips, Martin (2015) European airline performance: a data envelopment analysis with extrapolations based on model outputs. Master of Business Studies thesis, Dublin City University.

- The customers’ perception of servicescape’s influence on their behaviours, in the food retail industry : Dublin Business School 2015

- Coughlan, Ray (2015) What was the role of leadership in the transformation of a failing Irish Insurance business. Masters thesis, Dublin, National College of Ireland.

- << Previous: Search strategies and Databases

- Next: Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://ait.libguides.com/literaturereview

Literature Review Example/Sample

Detailed Walkthrough + Free Literature Review Template

If you’re working on a dissertation or thesis and are looking for an example of a strong literature review chapter , you’ve come to the right place.

In this video, we walk you through an A-grade literature review from a dissertation that earned full distinction . We start off by discussing the five core sections of a literature review chapter by unpacking our free literature review template . This includes:

- The literature review opening/ introduction section

- The theoretical framework (or foundation of theory)

- The empirical research

- The research gap

- The closing section

We then progress to the sample literature review (from an A-grade Master’s-level dissertation) to show how these concepts are applied in the literature review chapter. You can access the free resources mentioned in this video below.

PS – If you’re working on a dissertation, be sure to also check out our collection of dissertation and thesis examples here .

FAQ: Literature Review Example

Literature review example: frequently asked questions, is the sample literature review real.

Yes. The literature review example is an extract from a Master’s-level dissertation for an MBA program. It has not been edited in any way.

Can I replicate this literature review for my dissertation?

As we discuss in the video, every literature review will be slightly different, depending on the university’s unique requirements, as well as the nature of the research itself. Therefore, you’ll need to tailor your literature review to suit your specific context.

You can learn more about the basics of writing a literature review here .

Where can I find more examples of literature reviews?

The best place to find more examples of literature review chapters would be within dissertation/thesis databases. These databases include dissertations, theses and research projects that have successfully passed the assessment criteria for the respective university, meaning that you have at least some sort of quality assurance.

The Open Access Thesis Database (OATD) is a good starting point.

How do I get the literature review template?

You can access our free literature review chapter template here .

Is the template really free?

Yes. There is no cost for the template and you are free to use it as you wish.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

What will it take for you to guide me in my Ph.D research work?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Literature review

How to write a literature review in 6 steps

How do you write a good literature review? This step-by-step guide on how to write an excellent literature review covers all aspects of planning and writing literature reviews for academic papers and theses.

How to write a systematic literature review [9 steps]

How do you write a systematic literature review? What types of systematic literature reviews exist and where do you use them? Learn everything you need to know about a systematic literature review in this guide

What is a literature review? [with examples]

Not sure what a literature review is? This guide covers the definition, purpose, and format of a literature review.

15 Literature Review Examples

Literature reviews are a necessary step in a research process and often required when writing your research proposal . They involve gathering, analyzing, and evaluating existing knowledge about a topic in order to find gaps in the literature where future studies will be needed.

Ideally, once you have completed your literature review, you will be able to identify how your research project can build upon and extend existing knowledge in your area of study.

Generally, for my undergraduate research students, I recommend a narrative review, where themes can be generated in order for the students to develop sufficient understanding of the topic so they can build upon the themes using unique methods or novel research questions.

If you’re in the process of writing a literature review, I have developed a literature review template for you to use – it’s a huge time-saver and walks you through how to write a literature review step-by-step:

Get your time-saving templates here to write your own literature review.

Literature Review Examples

For the following types of literature review, I present an explanation and overview of the type, followed by links to some real-life literature reviews on the topics.

1. Narrative Review Examples

Also known as a traditional literature review, the narrative review provides a broad overview of the studies done on a particular topic.

It often includes both qualitative and quantitative studies and may cover a wide range of years.

The narrative review’s purpose is to identify commonalities, gaps, and contradictions in the literature .

I recommend to my students that they should gather their studies together, take notes on each study, then try to group them by themes that form the basis for the review (see my step-by-step instructions at the end of the article).

Example Study

Title: Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations

Citation: Vermeir, P., Vandijck, D., Degroote, S., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Mortier, E., … & Vogelaers, D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International journal of clinical practice , 69 (11), 1257-1267.

Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ijcp.12686

Overview: This narrative review analyzed themes emerging from 69 articles about communication in healthcare contexts. Five key themes were found in the literature: poor communication can lead to various negative outcomes, discontinuity of care, compromise of patient safety, patient dissatisfaction, and inefficient use of resources. After presenting the key themes, the authors recommend that practitioners need to approach healthcare communication in a more structured way, such as by ensuring there is a clear understanding of who is in charge of ensuring effective communication in clinical settings.

Other Examples

- Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review (Reith, 2018) – read here

- Examining the Presence, Consequences, and Reduction of Implicit Bias in Health Care: A Narrative Review (Zestcott, Blair & Stone, 2016) – read here

- A Narrative Review of School-Based Physical Activity for Enhancing Cognition and Learning (Mavilidi et al., 2018) – read here

- A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents (Dyrbye & Shanafelt, 2015) – read here

2. Systematic Review Examples

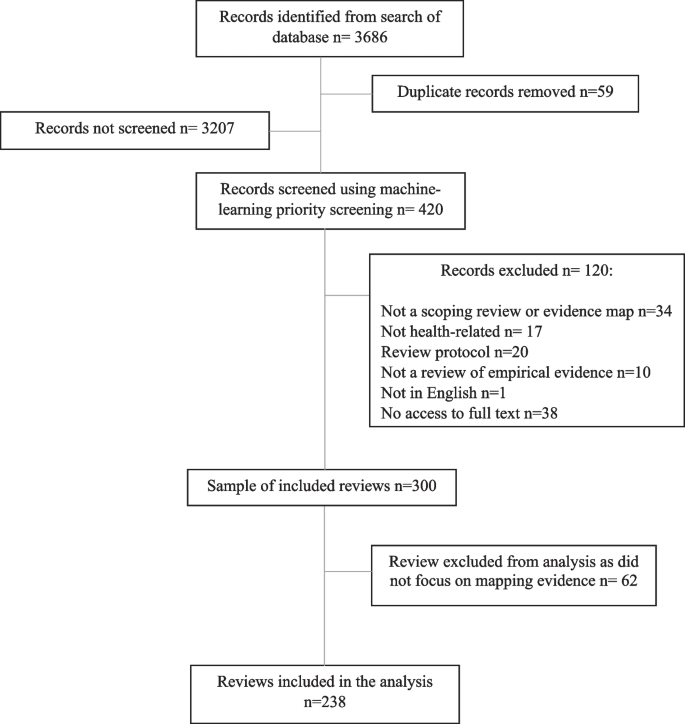

This type of literature review is more structured and rigorous than a narrative review. It involves a detailed and comprehensive plan and search strategy derived from a set of specified research questions.

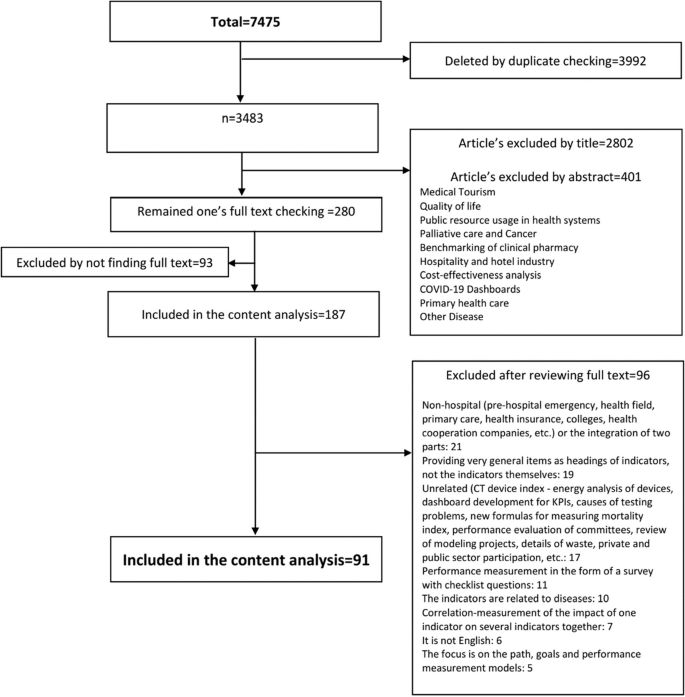

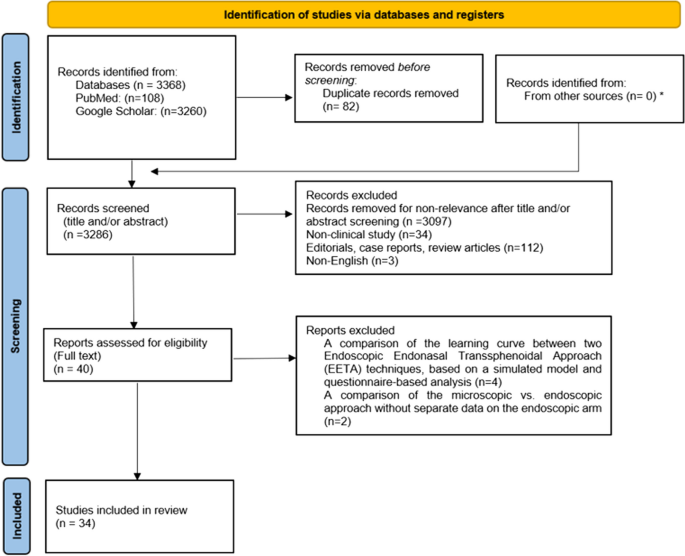

The key way you’d know a systematic review compared to a narrative review is in the methodology: the systematic review will likely have a very clear criteria for how the studies were collected, and clear explanations of exclusion/inclusion criteria.

The goal is to gather the maximum amount of valid literature on the topic, filter out invalid or low-quality reviews, and minimize bias. Ideally, this will provide more reliable findings, leading to higher-quality conclusions and recommendations for further research.

You may note from the examples below that the ‘method’ sections in systematic reviews tend to be much more explicit, often noting rigid inclusion/exclusion criteria and exact keywords used in searches.

Title: The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review

Citation: Roman, S., Sánchez-Siles, L. M., & Siegrist, M. (2017). The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends in food science & technology , 67 , 44-57.

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092422441730122X

Overview: This systematic review included 72 studies of food naturalness to explore trends in the literature about its importance for consumers. Keywords used in the data search included: food, naturalness, natural content, and natural ingredients. Studies were included if they examined consumers’ preference for food naturalness and contained empirical data. The authors found that the literature lacks clarity about how naturalness is defined and measured, but also found that food consumption is significantly influenced by perceived naturalness of goods.

- A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018 (Martin, Sun & Westine, 2020) – read here

- Where Is Current Research on Blockchain Technology? (Yli-Huumo et al., 2016) – read here

- Universities—industry collaboration: A systematic review (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015) – read here

- Internet of Things Applications: A Systematic Review (Asghari, Rahmani & Javadi, 2019) – read here

3. Meta-analysis

This is a type of systematic review that uses statistical methods to combine and summarize the results of several studies.

Due to its robust methodology, a meta-analysis is often considered the ‘gold standard’ of secondary research , as it provides a more precise estimate of a treatment effect than any individual study contributing to the pooled analysis.

Furthermore, by aggregating data from a range of studies, a meta-analysis can identify patterns, disagreements, or other interesting relationships that may have been hidden in individual studies.

This helps to enhance the generalizability of findings, making the conclusions drawn from a meta-analysis particularly powerful and informative for policy and practice.

Title: Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s Disease Risk: A Meta-Meta-Analysis

Citation: Sáiz-Vazquez, O., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubillos-Landa, S., Pacheco-Bonrostro, J., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease risk: a meta-meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 10(6), 386.

Source: https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10060386

O verview: This study examines the relationship between cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Researchers conducted a systematic search of meta-analyses and reviewed several databases, collecting 100 primary studies and five meta-analyses to analyze the connection between cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease. They find that the literature compellingly demonstrates that low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels significantly influence the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

- The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research (Wisniewski, Zierer & Hattie, 2020) – read here

- How Much Does Education Improve Intelligence? A Meta-Analysis (Ritchie & Tucker-Drob, 2018) – read here

- A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling (Geiger et al., 2019) – read here

- Stress management interventions for police officers and recruits (Patterson, Chung & Swan, 2014) – read here

Other Types of Reviews

- Scoping Review: This type of review is used to map the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available. It can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right, or as a precursor to a systematic review.

- Rapid Review: This type of review accelerates the systematic review process in order to produce information in a timely manner. This is achieved by simplifying or omitting stages of the systematic review process.

- Integrative Review: This review method is more inclusive than others, allowing for the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research. The goal is to more comprehensively understand a particular phenomenon.

- Critical Review: This is similar to a narrative review but requires a robust understanding of both the subject and the existing literature. In a critical review, the reviewer not only summarizes the existing literature, but also evaluates its strengths and weaknesses. This is common in the social sciences and humanities .

- State-of-the-Art Review: This considers the current level of advancement in a field or topic and makes recommendations for future research directions. This type of review is common in technological and scientific fields but can be applied to any discipline.

How to Write a Narrative Review (Tips for Undergrad Students)

Most undergraduate students conducting a capstone research project will be writing narrative reviews. Below is a five-step process for conducting a simple review of the literature for your project.

- Search for Relevant Literature: Use scholarly databases related to your field of study, provided by your university library, along with appropriate search terms to identify key scholarly articles that have been published on your topic.

- Evaluate and Select Sources: Filter the source list by selecting studies that are directly relevant and of sufficient quality, considering factors like credibility , objectivity, accuracy, and validity.

- Analyze and Synthesize: Review each source and summarize the main arguments in one paragraph (or more, for postgrad). Keep these summaries in a table.

- Identify Themes: With all studies summarized, group studies that share common themes, such as studies that have similar findings or methodologies.

- Write the Review: Write your review based upon the themes or subtopics you have identified. Give a thorough overview of each theme, integrating source data, and conclude with a summary of the current state of knowledge then suggestions for future research based upon your evaluation of what is lacking in the literature.

Literature reviews don’t have to be as scary as they seem. Yes, they are difficult and require a strong degree of comprehension of academic studies. But it can be feasibly done through following a structured approach to data collection and analysis. With my undergraduate research students (who tend to conduct small-scale qualitative studies ), I encourage them to conduct a narrative literature review whereby they can identify key themes in the literature. Within each theme, students can critique key studies and their strengths and limitations , in order to get a lay of the land and come to a point where they can identify ways to contribute new insights to the existing academic conversation on their topic.

Ankrah, S., & Omar, A. T. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), 387-408.

Asghari, P., Rahmani, A. M., & Javadi, H. H. S. (2019). Internet of Things applications: A systematic review. Computer Networks , 148 , 241-261.

Dyrbye, L., & Shanafelt, T. (2016). A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Medical education , 50 (1), 132-149.

Geiger, J. L., Steg, L., Van Der Werff, E., & Ünal, A. B. (2019). A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. Journal of environmental psychology , 64 , 78-97.

Martin, F., Sun, T., & Westine, C. D. (2020). A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018. Computers & education , 159 , 104009.

Mavilidi, M. F., Ruiter, M., Schmidt, M., Okely, A. D., Loyens, S., Chandler, P., & Paas, F. (2018). A narrative review of school-based physical activity for enhancing cognition and learning: The importance of relevancy and integration. Frontiers in psychology , 2079.

Patterson, G. T., Chung, I. W., & Swan, P. W. (2014). Stress management interventions for police officers and recruits: A meta-analysis. Journal of experimental criminology , 10 , 487-513.

Reith, T. P. (2018). Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: a narrative review. Cureus , 10 (12).

Ritchie, S. J., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2018). How much does education improve intelligence? A meta-analysis. Psychological science , 29 (8), 1358-1369.

Roman, S., Sánchez-Siles, L. M., & Siegrist, M. (2017). The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends in food science & technology , 67 , 44-57.

Sáiz-Vazquez, O., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubillos-Landa, S., Pacheco-Bonrostro, J., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease risk: a meta-meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 10(6), 386.

Vermeir, P., Vandijck, D., Degroote, S., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Mortier, E., … & Vogelaers, D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International journal of clinical practice , 69 (11), 1257-1267.

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology , 10 , 3087.

Yli-Huumo, J., Ko, D., Choi, S., Park, S., & Smolander, K. (2016). Where is current research on blockchain technology?—a systematic review. PloS one , 11 (10), e0163477.

Zestcott, C. A., Blair, I. V., & Stone, J. (2016). Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: a narrative review. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations , 19 (4), 528-542

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Social-Emotional Learning (Definition, Examples, Pros & Cons)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is Educational Psychology?

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ What is IQ? (Intelligence Quotient)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Literature Review: What is a Literature Review?

- Sample Searches

- Examples of Published Literature Reviews

- Researching Your Topic

- Subject Searching

- Google Scholar

- Track Your Work

- Citation Managers This link opens in a new window

- Citation Guides This link opens in a new window

- Tips on Writing Your Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Research Help

Ask a Librarian

Chat with a Librarian

Lisle: (630) 829-6057 Mesa: (480) 878-7514 Toll Free: (877) 575-6050 Email: [email protected]

Book a Research Consultation Library Hours

Not Just for Graduate Students!

A literature review is an in-depth critical analysis of published scholarly research related to a specific topic. Published scholarly research (the "literature") may include journal articles, books, book chapters, dissertations and thesis, or conference proceedings.

A solid lit review must:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you're developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Why Conduct a Literature Review?

- to distinguish what has been done from what needs to be done

- to discover important variables relevant to the topic

- to synthesize and gain new perspective

- to identify relationships between ideas and practices

- to establish the context of the topic

- to rationalize the significance of the problem

- to enhance and acquire subject vocabulary

- to understand the structure of the subject

- tp relate ideas and theory to applications

- to identify main methodologies and research techniques that have been used

- to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-art development

Questions to Consider

- What is the overarching question or problem your literature review seeks to address?

- How much familiarity do you already have with the field? Are you already familiar with common methodologies or professional vocabularies?

- What types of strategies or questions have others in your field pursued?

- How will you synthesize or summarize the information you gather?

- What do you or others perceive to be lacking in your field?

- Is your topic broad? How could it be narrowed?

- Can you articulate why your topic is important in your field?

- Next: Sample Searches >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 3:34 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.ben.edu/lit-review

Kindlon Hall 5700 College Rd. Lisle, IL 60532 (630) 829-6050

Gillett Hall 225 E. Main St. Mesa, AZ 85201 (480) 878-7514

- Study resources

- Calendar - Graduate

- Calendar - Undergraduate

- Class schedules

- Class cancellations

- Course registration

- Important academic dates

- More academic resources

- Campus services

- IT services

- Job opportunities

- Mental health support

- Student Service Centre (Birks)

- Calendar of events

- Latest news

- Media Relations

- Faculties, Schools & Colleges

- Arts and Science

- Gina Cody School of Engineering and Computer Science

- John Molson School of Business

- School of Graduate Studies

- All Schools, Colleges & Departments

- Directories

- My Library Account (Sofia) View checkouts, fees, place requests and more

- Interlibrary Loans Request books from external libraries

- Zotero Manage your citations and create bibliographies

- E-journals via BrowZine Browse & read journals through a friendly interface

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver Request a PDF of an article/chapter we have in our physical collection

- Course Reserves Online course readings

- Spectrum Deposit a thesis or article

- WebPrint Upload documents to print with DPrint

- Sofia Discovery tool

- Databases by subject

- Course Reserves

- E-journals via BrowZine

- E-journals via Sofia

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver

- Intercampus Delivery of Bound Periodicals/Microforms

- Interlibrary Loans

- Spectrum Research Repository

- Special Collections

- Additional resources & services

- Loans & Returns (Circulation)

- Subject & course guides

- Open Educational Resources Guide

- General guides for users

- Evaluating...

- Ask a librarian

- Research Skills Tutorial

- Quick Things for Digital Knowledge

- Bibliometrics & research impact guide

- Concordia University Press

- Copyright Guide

- Copyright Guide for Thesis Preparation

- Digital Scholarship

- Digital Preservation

- Open Access

- ORCID at Concordia

- Research data management guide

- Scholarship of Teaching & Learning

- Systematic Reviews

- How to get published speaker series

- Borrow (laptops, tablets, equipment)

- Connect (netname, Wi-Fi, guest accounts)

- Desktop computers, software & availability maps

- Group study, presentation practice & classrooms

- Printers, copiers & scanners

- Technology Sandbox

- Visualization Studio

- Webster Library

- Vanier Library

- Grey Nuns Reading Room

- Book a group study room/scanner

- Study spaces

- Floor plans

- Room booking for academic events

- Exhibitions

- Librarians & staff

- University Librarian

- Memberships & collaborations

- Indigenous Student Librarian program

- Wikipedian in residence

- Researcher-in-Residence

- Feedback & improvement

- Annual reports & fast facts

- Annual Plan

- Library Services Fund

- Giving to the Library

- Webster Transformation blog

- Policies & Code of Conduct

The Campaign for Concordia

Library Research Skills Tutorial

Log into...

- My Library account (Sofia)

- Interlibrary loans

- Article/chapter scan

- Course reserves

Quick links

How to write a literature review

Examples of a published literature review.

Literature reviews are often published as scholarly articles, books, and reports. Here is an example of a recent literature review published as a scholarly journal article:

Ledesma, M. C., & Calderón, D. (2015). Critical race theory in education: A review of past literature and a look to the future. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 206-222. Link to the article

- Privacy Policy

Home » Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and Examples

Literature Review – Types Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Literature Review

Definition:

A literature review is a comprehensive and critical analysis of the existing literature on a particular topic or research question. It involves identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing relevant literature, including scholarly articles, books, and other sources, to provide a summary and critical assessment of what is known about the topic.

Types of Literature Review

Types of Literature Review are as follows:

- Narrative literature review : This type of review involves a comprehensive summary and critical analysis of the available literature on a particular topic or research question. It is often used as an introductory section of a research paper.

- Systematic literature review: This is a rigorous and structured review that follows a pre-defined protocol to identify, evaluate, and synthesize all relevant studies on a specific research question. It is often used in evidence-based practice and systematic reviews.

- Meta-analysis: This is a quantitative review that uses statistical methods to combine data from multiple studies to derive a summary effect size. It provides a more precise estimate of the overall effect than any individual study.

- Scoping review: This is a preliminary review that aims to map the existing literature on a broad topic area to identify research gaps and areas for further investigation.

- Critical literature review : This type of review evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the existing literature on a particular topic or research question. It aims to provide a critical analysis of the literature and identify areas where further research is needed.

- Conceptual literature review: This review synthesizes and integrates theories and concepts from multiple sources to provide a new perspective on a particular topic. It aims to provide a theoretical framework for understanding a particular research question.

- Rapid literature review: This is a quick review that provides a snapshot of the current state of knowledge on a specific research question or topic. It is often used when time and resources are limited.

- Thematic literature review : This review identifies and analyzes common themes and patterns across a body of literature on a particular topic. It aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature and identify key themes and concepts.

- Realist literature review: This review is often used in social science research and aims to identify how and why certain interventions work in certain contexts. It takes into account the context and complexities of real-world situations.

- State-of-the-art literature review : This type of review provides an overview of the current state of knowledge in a particular field, highlighting the most recent and relevant research. It is often used in fields where knowledge is rapidly evolving, such as technology or medicine.

- Integrative literature review: This type of review synthesizes and integrates findings from multiple studies on a particular topic to identify patterns, themes, and gaps in the literature. It aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge on a particular topic.

- Umbrella literature review : This review is used to provide a broad overview of a large and diverse body of literature on a particular topic. It aims to identify common themes and patterns across different areas of research.

- Historical literature review: This type of review examines the historical development of research on a particular topic or research question. It aims to provide a historical context for understanding the current state of knowledge on a particular topic.

- Problem-oriented literature review : This review focuses on a specific problem or issue and examines the literature to identify potential solutions or interventions. It aims to provide practical recommendations for addressing a particular problem or issue.

- Mixed-methods literature review : This type of review combines quantitative and qualitative methods to synthesize and analyze the available literature on a particular topic. It aims to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research question by combining different types of evidence.

Parts of Literature Review

Parts of a literature review are as follows:

Introduction

The introduction of a literature review typically provides background information on the research topic and why it is important. It outlines the objectives of the review, the research question or hypothesis, and the scope of the review.

Literature Search

This section outlines the search strategy and databases used to identify relevant literature. The search terms used, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and any limitations of the search are described.

Literature Analysis

The literature analysis is the main body of the literature review. This section summarizes and synthesizes the literature that is relevant to the research question or hypothesis. The review should be organized thematically, chronologically, or by methodology, depending on the research objectives.

Critical Evaluation

Critical evaluation involves assessing the quality and validity of the literature. This includes evaluating the reliability and validity of the studies reviewed, the methodology used, and the strength of the evidence.

The conclusion of the literature review should summarize the main findings, identify any gaps in the literature, and suggest areas for future research. It should also reiterate the importance of the research question or hypothesis and the contribution of the literature review to the overall research project.

The references list includes all the sources cited in the literature review, and follows a specific referencing style (e.g., APA, MLA, Harvard).

How to write Literature Review

Here are some steps to follow when writing a literature review:

- Define your research question or topic : Before starting your literature review, it is essential to define your research question or topic. This will help you identify relevant literature and determine the scope of your review.

- Conduct a comprehensive search: Use databases and search engines to find relevant literature. Look for peer-reviewed articles, books, and other academic sources that are relevant to your research question or topic.

- Evaluate the sources: Once you have found potential sources, evaluate them critically to determine their relevance, credibility, and quality. Look for recent publications, reputable authors, and reliable sources of data and evidence.

- Organize your sources: Group the sources by theme, method, or research question. This will help you identify similarities and differences among the literature, and provide a structure for your literature review.

- Analyze and synthesize the literature : Analyze each source in depth, identifying the key findings, methodologies, and conclusions. Then, synthesize the information from the sources, identifying patterns and themes in the literature.

- Write the literature review : Start with an introduction that provides an overview of the topic and the purpose of the literature review. Then, organize the literature according to your chosen structure, and analyze and synthesize the sources. Finally, provide a conclusion that summarizes the key findings of the literature review, identifies gaps in knowledge, and suggests areas for future research.

- Edit and proofread: Once you have written your literature review, edit and proofread it carefully to ensure that it is well-organized, clear, and concise.

Examples of Literature Review

Here’s an example of how a literature review can be conducted for a thesis on the topic of “ The Impact of Social Media on Teenagers’ Mental Health”:

- Start by identifying the key terms related to your research topic. In this case, the key terms are “social media,” “teenagers,” and “mental health.”

- Use academic databases like Google Scholar, JSTOR, or PubMed to search for relevant articles, books, and other publications. Use these keywords in your search to narrow down your results.

- Evaluate the sources you find to determine if they are relevant to your research question. You may want to consider the publication date, author’s credentials, and the journal or book publisher.

- Begin reading and taking notes on each source, paying attention to key findings, methodologies used, and any gaps in the research.

- Organize your findings into themes or categories. For example, you might categorize your sources into those that examine the impact of social media on self-esteem, those that explore the effects of cyberbullying, and those that investigate the relationship between social media use and depression.

- Synthesize your findings by summarizing the key themes and highlighting any gaps or inconsistencies in the research. Identify areas where further research is needed.

- Use your literature review to inform your research questions and hypotheses for your thesis.

For example, after conducting a literature review on the impact of social media on teenagers’ mental health, a thesis might look like this:

“Using a mixed-methods approach, this study aims to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes in teenagers. Specifically, the study will examine the effects of cyberbullying, social comparison, and excessive social media use on self-esteem, anxiety, and depression. Through an analysis of survey data and qualitative interviews with teenagers, the study will provide insight into the complex relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes, and identify strategies for promoting positive mental health outcomes in young people.”

Reference: Smith, J., Jones, M., & Lee, S. (2019). The effects of social media use on adolescent mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(2), 154-165. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.03.024

Reference Example: Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range. doi:0000000/000000000000 or URL

Applications of Literature Review

some applications of literature review in different fields:

- Social Sciences: In social sciences, literature reviews are used to identify gaps in existing research, to develop research questions, and to provide a theoretical framework for research. Literature reviews are commonly used in fields such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, and political science.

- Natural Sciences: In natural sciences, literature reviews are used to summarize and evaluate the current state of knowledge in a particular field or subfield. Literature reviews can help researchers identify areas where more research is needed and provide insights into the latest developments in a particular field. Fields such as biology, chemistry, and physics commonly use literature reviews.

- Health Sciences: In health sciences, literature reviews are used to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments, identify best practices, and determine areas where more research is needed. Literature reviews are commonly used in fields such as medicine, nursing, and public health.

- Humanities: In humanities, literature reviews are used to identify gaps in existing knowledge, develop new interpretations of texts or cultural artifacts, and provide a theoretical framework for research. Literature reviews are commonly used in fields such as history, literary studies, and philosophy.

Role of Literature Review in Research

Here are some applications of literature review in research:

- Identifying Research Gaps : Literature review helps researchers identify gaps in existing research and literature related to their research question. This allows them to develop new research questions and hypotheses to fill those gaps.

- Developing Theoretical Framework: Literature review helps researchers develop a theoretical framework for their research. By analyzing and synthesizing existing literature, researchers can identify the key concepts, theories, and models that are relevant to their research.

- Selecting Research Methods : Literature review helps researchers select appropriate research methods and techniques based on previous research. It also helps researchers to identify potential biases or limitations of certain methods and techniques.

- Data Collection and Analysis: Literature review helps researchers in data collection and analysis by providing a foundation for the development of data collection instruments and methods. It also helps researchers to identify relevant data sources and identify potential data analysis techniques.

- Communicating Results: Literature review helps researchers to communicate their results effectively by providing a context for their research. It also helps to justify the significance of their findings in relation to existing research and literature.

Purpose of Literature Review

Some of the specific purposes of a literature review are as follows:

- To provide context: A literature review helps to provide context for your research by situating it within the broader body of literature on the topic.

- To identify gaps and inconsistencies: A literature review helps to identify areas where further research is needed or where there are inconsistencies in the existing literature.

- To synthesize information: A literature review helps to synthesize the information from multiple sources and present a coherent and comprehensive picture of the current state of knowledge on the topic.

- To identify key concepts and theories : A literature review helps to identify key concepts and theories that are relevant to your research question and provide a theoretical framework for your study.

- To inform research design: A literature review can inform the design of your research study by identifying appropriate research methods, data sources, and research questions.

Characteristics of Literature Review

Some Characteristics of Literature Review are as follows:

- Identifying gaps in knowledge: A literature review helps to identify gaps in the existing knowledge and research on a specific topic or research question. By analyzing and synthesizing the literature, you can identify areas where further research is needed and where new insights can be gained.

- Establishing the significance of your research: A literature review helps to establish the significance of your own research by placing it in the context of existing research. By demonstrating the relevance of your research to the existing literature, you can establish its importance and value.

- Informing research design and methodology : A literature review helps to inform research design and methodology by identifying the most appropriate research methods, techniques, and instruments. By reviewing the literature, you can identify the strengths and limitations of different research methods and techniques, and select the most appropriate ones for your own research.

- Supporting arguments and claims: A literature review provides evidence to support arguments and claims made in academic writing. By citing and analyzing the literature, you can provide a solid foundation for your own arguments and claims.

- I dentifying potential collaborators and mentors: A literature review can help identify potential collaborators and mentors by identifying researchers and practitioners who are working on related topics or using similar methods. By building relationships with these individuals, you can gain valuable insights and support for your own research and practice.

- Keeping up-to-date with the latest research : A literature review helps to keep you up-to-date with the latest research on a specific topic or research question. By regularly reviewing the literature, you can stay informed about the latest findings and developments in your field.

Advantages of Literature Review

There are several advantages to conducting a literature review as part of a research project, including:

- Establishing the significance of the research : A literature review helps to establish the significance of the research by demonstrating the gap or problem in the existing literature that the study aims to address.

- Identifying key concepts and theories: A literature review can help to identify key concepts and theories that are relevant to the research question, and provide a theoretical framework for the study.

- Supporting the research methodology : A literature review can inform the research methodology by identifying appropriate research methods, data sources, and research questions.

- Providing a comprehensive overview of the literature : A literature review provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge on a topic, allowing the researcher to identify key themes, debates, and areas of agreement or disagreement.

- Identifying potential research questions: A literature review can help to identify potential research questions and areas for further investigation.

- Avoiding duplication of research: A literature review can help to avoid duplication of research by identifying what has already been done on a topic, and what remains to be done.

- Enhancing the credibility of the research : A literature review helps to enhance the credibility of the research by demonstrating the researcher’s knowledge of the existing literature and their ability to situate their research within a broader context.

Limitations of Literature Review

Limitations of Literature Review are as follows:

- Limited scope : Literature reviews can only cover the existing literature on a particular topic, which may be limited in scope or depth.

- Publication bias : Literature reviews may be influenced by publication bias, which occurs when researchers are more likely to publish positive results than negative ones. This can lead to an incomplete or biased picture of the literature.

- Quality of sources : The quality of the literature reviewed can vary widely, and not all sources may be reliable or valid.

- Time-limited: Literature reviews can become quickly outdated as new research is published, making it difficult to keep up with the latest developments in a field.

- Subjective interpretation : Literature reviews can be subjective, and the interpretation of the findings can vary depending on the researcher’s perspective or bias.

- Lack of original data : Literature reviews do not generate new data, but rather rely on the analysis of existing studies.

- Risk of plagiarism: It is important to ensure that literature reviews do not inadvertently contain plagiarism, which can occur when researchers use the work of others without proper attribution.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 19, Issue 1

- Reviewing the literature

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Joanna Smith 1 ,

- Helen Noble 2

- 1 School of Healthcare, University of Leeds , Leeds , UK

- 2 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queens's University Belfast , Belfast , UK

- Correspondence to Dr Joanna Smith , School of Healthcare, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK; j.e.smith1{at}leeds.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102252

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Implementing evidence into practice requires nurses to identify, critically appraise and synthesise research. This may require a comprehensive literature review: this article aims to outline the approaches and stages required and provides a working example of a published review.

Are there different approaches to undertaking a literature review?

What stages are required to undertake a literature review.

The rationale for the review should be established; consider why the review is important and relevant to patient care/safety or service delivery. For example, Noble et al 's 4 review sought to understand and make recommendations for practice and research in relation to dialysis refusal and withdrawal in patients with end-stage renal disease, an area of care previously poorly described. If appropriate, highlight relevant policies and theoretical perspectives that might guide the review. Once the key issues related to the topic, including the challenges encountered in clinical practice, have been identified formulate a clear question, and/or develop an aim and specific objectives. The type of review undertaken is influenced by the purpose of the review and resources available. However, the stages or methods used to undertake a review are similar across approaches and include:

Formulating clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, for example, patient groups, ages, conditions/treatments, sources of evidence/research designs;

Justifying data bases and years searched, and whether strategies including hand searching of journals, conference proceedings and research not indexed in data bases (grey literature) will be undertaken;

Developing search terms, the PICU (P: patient, problem or population; I: intervention; C: comparison; O: outcome) framework is a useful guide when developing search terms;