| Our research reveals two almost diametrically opposite descriptions of performance in project delivery in South Africa. The first is a description of failure and its characteristics. The second is a number of accounts of success in current project delivery. It appears that there has been much improvement on their earlier failures. For completeness, descriptions of the two performances are discussed starting with an article entitled: “South Africa: Why Have All the Rural Tech Projects Failed?” by Kathryn Cave, Editor at IDG Connect dated 21 June 2013 [1]. We shall discuss the reported reasons for the failure and also other failed projects. According to her, poor planning and implementation, as described below, was the main reason. The author reported scepticism in the planning and implementation of major projects. Quoting Schofield, she wrote: Nearly every government plan talks about what will be achieved at the end of 10, 20, 40 years - none of them is held to account for steps along the way. [South Africa is] small on delivery, poor at executing the plans, lousy at monitoring progress and ironing out the problems that arise along the way. This summarised the views of the then Vice Chairman of Africa ICT Alliance (Africa Information & Communication Technologies Alliance). His comments were made on the National ICT Plan and the Universal Service and Access Agency (USAASA). The aim of the plan was described as follows: "This state-owned entity of government aims to ensure that every man, woman and child whether living in the remote areas of the Kalahari or in urban areas of Gauteng will be able to connect, speak, explore and study using ICT” He commented that the organisation was “sitting on billions of Rands that it does not know how to spend ... and what has been spent has achieved little.” They include the following: Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipality (NMBMM) -South Africa Metro bus purchase Integrated Public Transport System (IPTS) February 2015 R2 billion ZAR (approximately $130 million) Sixty buses purchased at a cost of R100 million (ZAR) in 2009 have turned to a failed project. They were purchased as part of a programme to refresh municipal bus service in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. They were used during the 2010 Soccer World Cup but up to 2018 they were still parked. The bus purchase was part of a larger R2 billion ($130 million) project to implement a Bus Rapid Transit system in Port Elizabeth, which started in 2008. Sadly, they are yet to be used in operation. The problems identified are as follows: ■ The specification was wrong, and this resulted in the purchase of buses that are too large for the driving lanes. ■ There was a failure to identify the need to drop passengers off on “central islands,” which resulted in the doors ending up on the wrong side of the bus. It was reported that from 2008 to 2013 the project had been through five different engineering companies and four project managers. Whilst this was worrying, it was better that efforts were being made to resolve the issues than the project being abandoned as it could happen in some other African countries. Contributing factors to project failure included: ■ Poor requirements management ■ Lack of attention to detail (resulting in faulty requirements) ■ Dysfunctional decision making ■ Failure to engage stakeholders ■ High staff turnover levels Sentech was the first company in South Africa to launch a wireless broadband service, introducing services in the 3-5GHz band under the brand MyWireless in 2002. However, due to poor financial operations there was only a limited rollout to parts of Johannesburg, Cape Town, Durban, Pretoria and Nelspruit. It was eventually abandoned. Causes of failure of the Sentech’s MyWireless in South Africa: In October 2010, Sentech could not collect more than 60% of the money that it was owed. Its former leadership went aground amidst accusations of mismanagement, and the auditor-general was concerned they could not pay their bills to creditors. The MyWireless product was terminated in 2009 after the company proved it was unable to compete with better-resourced private-sector operators in the retail consumer market. To worsen the situation, Sentech could not organise itself to make a presentation to parliament’s portfolio committee on communications. It is relevant to observe that in spite of the failures they experienced, Sentech Limited had been reorganised to a successful State-Owned Enterprise (SOE) operating in the broadcasting signal distribution and telecommunications sectors and reporting to the Minister of Telecommunication and Postal Services. Probably, one of the positive lessons that could be taken away from the story of Sentech is that in spite of a temporary failure, an African company, like a company in developed countries, could be turned around if it was reorganised with changes in its management and if it was properly funded from the start before being left to operate independently. On 9 March 1997, Bill Gates reportedly launched the “Digital Villages” concept in the black township of Soweto, which had made headline news by its mass uprising in 1977. This township suffered and probably still suffers from extreme poverty. It was reported in the a daily newspaper in Spokane, Washington, USA, that when Gates visited in 1997, “a computer could cost as much as a house” and few people would think of going online. The centre launched was South Africa’s first free access “Digital Village,” funded by Microsoft, local computer companies and US development organisation, Africare. The concept was that the $100,000 computer package, housed in the Chiawelo Community Centre, should give the township’s poor residents a link to the information age. As part of the opening, Gates observed a class from the local Elsie Ngidi primary school using computers for the first time, before reportedly telling a crowd of 200: “Soweto is a milestone. There are major decisions ahead about whether technology will leave the developing world behind. This is to close the gap.” It was reported that even by 2013, there was hardly any evidence of the “Digital Villages” across South Africa. “[They] worked well for a while but collapsed as soon as the sponsors stopped funding the activities - the community had failed to make the use of technology self-sustaining.” A one-time Vice Chairman of Africa ICT Alliance, Adrian Schofield, explained: “What should have been a model for others to follow became a failure. This is a common outcome, where there is no long-term follow through” [4]. However, the report of the complete collapse of the concept in all of South Africa appears not well founded. It was likely that the computer package, housed in the Chiawelo Community Centre, might have failed but there were other Digital Villages, based on the concept, in other areas of South Africa. Some of these are discussed in the next paragraphs.

Microsoft, Comparex Africa, Anglo Platinum, Telkom Foundation and the Digital Partnership joined forces through the Kopano Joint Venture to equip three Rustenburg schools with technology. The computer centres were officially opened and handed over to the school communities by Andile Ngcaba, the Director-General, Department of Communications during a ceremony at Sedibelo Middle School in Moruleng, Rustenburg, on 23 May 2003. Microsoft presented the following business plan and guideline for how the company implemented the establishment of “Digital Villages” in South Africa. This has been adapted and modified for this publication. When a suitable centre has been identified, the community will be engaged in negotiations and discussions on the project. The following actions should be taken: ■ A committee comprising the partners and the community is established. ■ The community members are trained and prepared for the takeover once they are ready and the business partners have completed their term as per agreement. ■ An agreement is drafted to specify the roles and responsibilities of the business partners and the community members. This is done to define the relationship to prevent any misunderstanding. ■ Funding of the Digital Village, in both the present and future, is discussed and planned. ■ Microsoft approaches its business partners to donate hardware. Joint venture programmes are encouraged to ensure that hardware is available for the project. Other joint venture initiatives cover administrative costs, training and the future planning for the centre. To ensure sustainability of the project, the following actions are embarked upon: ■ Training: As already stated, the established committee members are trained and assisted to prepare for the self-maintenance and operation of the centre. ■ The students are encouraged to form computer clubs and contribute towards the usage of the centre. ■ Adults are expected to contribute a minimal sum of money to be registered as members of the centre. ■ The committee is assisted to open a bank account where these contributions will be deposited. ■ A Trust Fund will be established to allow the committee to raise funds on behalf of the centre. ■ The viability of a particular centre will be evaluated on an agreed and regular basis and will be subject to the continued interest of all parties. They are as follows: ■ Annual evaluation is conducted, and recommendations are made for further improvement of the centres. Relevant stakeholders will be identified, and participation is invited where applicable. ■ The project is considered successful in communities where evidence of commitment, achievement, organisation and structure is present. ■ The support of the community is assessed through the number of paid-up memberships, the number of regular attendees and the trainees per courses offered at the centre. The Microsoft-operated Digital Villages concept is a classic illustration of planning a project, properly resourcing it and providing resources for its follow-up when it goes into operation. This is followed by regular monitoring of its performance to ensure that the project deliverables do not fail. It could be a model to be adapted according to local requirements in providing foreign aided services to the developing world. The concept espoused in the Digital Villages programme exemplifies the suggestions being made in this book on how to achieve success and sustainability of projects and project deliverables. TechCentral, 28 March 2011.

In this section, project failures in some industries are examined. These are representative of failures in most industries in Africa. The causes of failures and lessons that could be learnt to prevent reoccurrence should be some of the takeaway points from this section. Name omitted deliberately. | |

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Examples of Failed Projects in South Africa

DOI link for Examples of Failed Projects in South Africa

Click here to navigate to parent product.

This chapter examines two almost diametrically opposite descriptions of performance in project delivery in South Africa. The first is a description of failure and its characteristics. The second is a number of accounts of success in current project delivery. The chapter discusses the reported reasons for the failure and also other failed projects. According to her, poor planning and implementation, as described below, was the main reason. The centre launched was South Africa’s first free access “Digital Village,” funded by Microsoft, local computer companies and US development organisation, Africare. Microsoft, Comparex Africa, Anglo Platinum, Telkom Foundation and the Digital Partnership joined forces through the Kopano Joint Venture to equip three Rustenburg schools with technology. Microsoft presented the following business plan and guideline for how the company implemented the establishment of “Digital Villages” in South Africa.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Enter your search term

*Limited to most recent 250 articles Use advanced search to set an earlier date range

Sponsored by

Saving articles

Articles can be saved for quick future reference. This is a subscriber benefit. If you are already a subscriber, please log in to save this article. If you are not a subscriber, click on the View Subscription Options button to subscribe.

Article Saved

Contact us at [email protected]

Forgot Password

Please enter the email address that you used to subscribe on Engineering News. Your password will be sent to this address.

Content Restricted

This content is only available to subscribers

REAL ECONOMY NEWS

sponsored by

- LATEST NEWS

- LOADSHEDDING

- MULTIMEDIA LATEST VIDEOS REAL ECONOMY REPORTS SECOND TAKE AUDIO ARTICLES CREAMER MEDIA ON SAFM WEBINARS YOUTUBE

- SECTORS AGRICULTURE AUTOMOTIVE CHEMICALS CONSTRUCTION DEFENCE & AEROSPACE ECONOMY ELECTRICITY ENERGY ENVIRONMENTAL MANUFACTURING METALS MINING RENEWABLE ENERGY SERVICES TECHNOLOGY & COMMUNICATIONS TRADE TRANSPORT & LOGISTICS WATER

- SPONSORED POSTS

- ANNOUNCEMENTS

- BUSINESS THOUGHT LEADERSHIP

- MINING WEEKLY

- SHOWROOM PLUS

- PRODUCT PORTAL

- MADE IN SOUTH AFRICA

- PRESS OFFICE

- WEBINAR RECORDINGS

- COMPANY PROFILES

- VIRTUAL SHOWROOMS

- CREAMER MEDIA

- BACK COPIES

- BUSINESS LEADER

- SUPPLEMENTS

- FEATURES LIBRARY

- RESEARCH REPORTS

- PROJECT BROWSER

Article Enquiry

Infrastructure projects fail when procurement is pursued administratively rather than strategically

Email This Article

separate emails by commas, maximum limit of 4 addresses

Photo by Creamer Media

As a magazine-and-online subscriber to Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly , you are entitled to one free research report of your choice . You would have received a promotional code at the time of your subscription. Have this code ready and click here . At the time of check-out, please enter your promotional code to download your free report. Email [email protected] if you have forgotten your promotional code. If you have previously accessed your free report, you can purchase additional Research Reports by clicking on the “Buy Report” button on this page. The most cost-effective way to access all our Research Reports is by subscribing to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa - you can upgrade your subscription now at this link .

The most cost-effective way to access all our Research Reports is by subscribing to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa - you can upgrade your subscription now at this link . For a full list of Research Channel Africa benefits, click here

If you are not a subscriber, you can either buy the individual research report by clicking on the ‘Buy Report’ button, or you can subscribe and, not only gain access to your one free report, but also enjoy all other subscriber benefits , including 1) an electronic archive of back issues of the weekly news magazine; 2) access to an industrial and mining projects browser; 3) access to a database of published articles; and 4) the ability to save articles for future reference. At the time of your subscription, Creamer Media’s subscriptions department will be in contact with you to ensure that you receive a copy of your preferred Research Report. The most cost-effective way to access all our Research Reports is by subscribing to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa - you can upgrade your subscription now at this link .

If you are a Creamer Media subscriber, click here to log in.

9th September 2020

By: Terence Creamer

Creamer Media Editor

Font size: - +

An analysis of public infrastructure delivery in South Africa, prepared for consideration by the National Planning Commission (NPC), identifies the quality of procurement and client-delivery management as the main differentiators between those projects that have succeeded in recent years and those that have failed.

Prepared by engineers Dr Ron Watermeyer and Dr Sean Phillips the analysis shows that, when a public-sector client adopts a strategic, rather than an administrative, stance to the design, procurement and implementation of infrastructure projects, value for money is typically secured.

By contrast, when no distinction is made between the procurement of infrastructure and the acquisition of general goods and services and when that procurement is led by finance departments rather than at an enterprise level, led by the CEO, projects tend to run over budget and behind schedule.

In their paper, the authors juxtapose several megaprojects, such as Eskom’s Medupi and Kusile, which have fallen short of original cost and schedule estimates, against two project-delivery success stories: the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producer Procurement Programme (REIPPPP) and Strategic Integrated Project 14 (SIP 14), which involved the building of two new universities.

Under the REIPPPP, government’s Independent Power Producer (IPP) Office oversaw the procurement, through seven bidding rounds, of 6 422 MW of renewables capacity, built by 112 IPPs at a cost of R209.7-billion.

Under SIP 14, the Department of Higher Education and Training employed the University of the Witwatersrand as its implementation agent for the construction of new campuses in Nelspruit, Mpumalanga and Kimberley, in the Norther Cape. Facilities for the first intake of students were delivered within 28 months of a political decision being taken in 2011. The costs deviation was also modest, despite the project proceeding before many of the contracts had been priced.

Phillips and Watermeyer tell Engineering News that, in the case of the REIPPPP, the quality of the procurement process run by the IPP Office resulted in the development of trust in the procurement process by developers and financiers. This, in turn, contributed to a marked reduction in the cost of renewable energy through successive bid rounds.

Key strengths of the new universities project, meanwhile, arose from client governance and organisational ownership practices, which provided effective direction and oversight of the organisation’s infrastructure delivery programme.

In both instances, there was also CEO-level client leadership, which helped ensure that a strategic and tactical approach was adopted throughout.

“Value for money is realised when the value proposition that was set for the project at the time that a decision was taken to invest in a project is as far as possible realised,” the authors explain.

For those megaprojects that ran well over budget and behind schedule the gap between what was intended and what was achieved is material:

- The Gauteng Freeway Improvement Programme cost R17.4-billion rather than the R11.4-billion initially estimated;

- The Gautrain budget increase from an original estimate of R6.8-billion to R25.2-billion;

- The capital cost of Transnet’s New Multi-Product Pipeline grew from an estimate of R12.7-billion to R30.4-billion;

- While Eskom’s Medupi and Kusile projects surged from initial estimates of R70-billion and R80-billion respectively to R208-billion-plus for Medupi and about R240-billion for Kusile.

Most of these projects have also seriously lagged their original delivery schedules.

In their paper, the authors highlight a direct linkage between the role played by the

client, or the organisation initiating the project and playing the role of the client, and infrastructure project outcomes regardless of size, complexity and location.

“The root cause of project failure or poor project outcomes can most often be attributed to a lack of governance and poor procurement and delivery management practices, all of which are under the control of the client,” Watermeyer and Phillips aver.

They acknowledge that poor project outcomes were exacerbated by corruption, but argue that the scope for corrupt practices increases in instances where procurement is conducted as an administrative rather than a strategic function and where the project implementors, the engineers, are excluded from procurement design and implementation.

“The major contributor to disappointing infrastructure project outcomes lies in inappropriate procurement practices, or the processes which initiate, create and fulfil contracts, and the absence of delivery management, or the critical leadership role played by a knowledgeable client to plan, specify, procure and deliver infrastructure projects efficiently and effectively, resulting in value for money.”

Phillips and Watermeyer add that “overly bureaucratised” procurement processes that emphasis compliance and box-ticking have not only made systems more costly, burdensome, ineffective and prone to fraud, but have also become entrenched.

Aligning South Africa’s investment profile to the National Development Plan’s objective of increasing gross fixed capital formation to 30% of gross domestic by 2030, with public infrastructure contributing 10%, will require significant changes to the procurement practices. Having spike at 8% of GDP in the run-up to the FIFA World Cup, public infrastructure had since fallen markedly to about 5%.

Phillips argues that initiating a recovery requires an acknowledgement in government, including the National Treasury, that infrastructure procurement is materially different from the acquisition of standard, well-defined and readily scoped and specified goods and services.

Instead it involves the procurement, programming and coordination of a network of suppliers of goods and services to collectively deliver or alter an asset on a site in accordance with specific client requirements and objectives.

Therefore, for infrastructure projects the prevailing supply-chain management practice in the public sector, which locates infrastructure procurement within financial processes and makes it a back office rather than a strategic function disconnected from operational line management, is not fit for purpose.

Watermeyer and Phillips acknowledge that it will take time to rebuild the capability of the public sector client, but hope that their input to the NPC could begin having an immediate influence as government seeks to use infrastructure investment as a way of reigniting the Covid-19-afflicted South African economy.

In parallel, however, they believe that a sustainable course correction could be supported through beefing up the language of the Procurement Bill, which is currently serving before lawmakers.

“Chapter 7 of the Bill is currently a blank canvas and is opened ended as everything is reliant on an instruction relating to an unknown infrastructure procurement and delivery management standard. We believe that the chapter needs to embed the principles for infrastructure procurement and delivery management.”

These principles, Phillips and Watermeyer explain, should include having all parts of the organisation that play a role in infrastructure delivery working together in a coordinated, efficient and effective manner to ensure that infrastructure delivery is managed as a long-term and strategic function, led by the CEO, rather than an administrative one.

“In this way, the institution can take ownership of infrastructure delivery and ensure delivery is managed as an enterprise.”

Edited by Creamer Media Reporter

Research Reports

Latest Multimedia

Latest News

South African leader in Steel -Racking, -Shelving, and -Mezzanine flooring. Universal has innovated an approach which encompasses conceptualising,...

In 1958 John Deere Construction made its first introduction to the industry with their model 64 bulldozer.

sponsored by

Press Office

Announcements

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa) Receive daily email newsletters Access to full search results Access archive of magazine back copies Access to Projects in Progress Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1 PLUS Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

MAGAZINE & ONLINE

R1500 (equivalent of R125 a month)

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

All benefits from Option 1

Electricity

Energy Transition

Roads, Rail and Ports

Battery Metals

CORPORATE PACKAGES

Discounted prices based on volume

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation

- South Africa

Examples of Failed Projects in South Africa

- In book: Achieving Successful and Sustainable Project Delivery in Africa (pp.37-44)

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

No full-text available

To read the full-text of this research, you can request a copy directly from the author.

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- PRINCE2 Agile®

- PRINCE2 Agile® German

- PRINCE2® German

- Management of Portfolios (MoP)®

- Management of Risk (M_o_R)®

- APMG-International AgilePM®

- APMG-International Change Management™

- APMG-International Better Business Cases™

- APMG International Project Planning & Control™ (PPC)

- APMG-International Managing Benefits™

- APMG-International PPS™

- Finance for Non Financial Managers

- APMG International Earned Value™

- Project Management Essentials

- Programme Management Essentials

- Portfolio Management Essentials

- Risk Management Essentials

- Certified Associate in Project Management (CAPM)®

- Project Management Professional (PMP)®

- Agile Certified Practitioner (PMI-ACP)®

- Risk Management Professional (RMP)®

- Program Management Professional (PgMP)®

- Scrum (Agile Business Consortium)

- Microsoft Project

- Praxis Framework™

- Online (with exam)

- Classroom (with exam)

- Blended learning (with exam)

- Virtual (with exam)

- Plus pack (with exam)

- The history of PRINCE2

- What should I study next?

- How can PRINCE2® 7TH Edition benefit you?

- What is PRINCE2 Infographic

- PRINCE2 Agile® definition

- PRINCE2 Agile® qualifications and training

- What should I do next?

- How PRINCE2 Agile® can benefit you?

- Understanding PRINCE2 Agile Whitepaper

- PRINCE2 Agile® F&P e-learning course outline: English

- PRINCE2 Agile Practitioner classroom course outline: English

- What is MSP® programme management?

- MSP® qualifications and training

- How MSP® can benefit you?

- MSP Benefits Plan

- MSP Risk Management Strategy

- MSP Blueprint

- Management of Portfolios (MoP)® qualifications and training

- How Management of Portfolios (MoP)® can benefit you?

- MOP Foundation & Practitioner Blended

- MoP Foundation Classroom

- MoP Foundation Online

- P3O® qualifications and training

- 10 Reasons to adopt P3O

- What is P3O and what can it do for you?

- P3O Foundation & Practitioner Blended

- Management of Risk (M_o_R)® definition

- Management of Risk (M_o_R)® qualifications and training

- Management of Risk (M_o_R)® history

- How Management of Risk (M_o_R)® can benefit you?

- How can M_o_R help you Manage Risk

- Applying M_o_R for Public services

- Corporate Governance and M_o_R

- MoV® definition

- MoV® qualifications and training

- MoV® history

- How MoV® can benefit you?

- MoV Foundation Online

- Online (without exam)

- APMG-International AgilePM® qualifications and training

- AgilePM Process Map

- AgilePM Foundation and Practitioner Blended

- AgilePM Foundation Online

- APMG-International Change Management™ qualifications and training

- How APMG-International Change Management™ can benefit you?

- Top 5 Tips Change Management & The Middle Managers

- APMG-International Change Management Practitioner Classroom

- APMG-International Change Management Foundation and Practitioner Classroom

- APMG-International Better Business Cases™ qualifications and training

- How APMG-International Better Business Cases™ can benefit you?

- APMG-International Managing Benefits™ qualifications and training

- How APMG-International Managing Benefits™ can benefit you?

- APMG-International Managing Benefits Practitioner Classroom

- APMG-International Managing Benefits Foundation and Practitioner Classroom

- APMG-International Managing Benefits Foundation Classroom Flyer

- Programme & Project Sponsorship (PPS) Classroom

- Programme & Project Sponsorship (PPS) Online

- Finance for Non Financial Managers qualifications and training

- Better Business Cases Practitioner Classroom Flyer

- Better Business Cases Foundation e-learning course outline

- APMG-International Better Business Cases Foundation & Practitioner Blended

- APMG International Earned Value™ qualifications and training

- How APMG International Earned Value™ can benefit you?

- APM definition

- APM qualifications and training

- RPP and ChPP information

- The APM Project Fundamentals Qualification Classroom Private

- The APM Project Fundamentals Qualification e-learning Private

- The APM Project Management Qualification (PMQ) Classroom Private

- Classroom (without exam)

- Certified Associate in Project Management (CAPM)® qualifications and training

- Project Management Professional (PMP)® qualifications and training

- How Project Management Professional (PMP)® can benefit you?

- Project Management Professional (PMP) classroom flyer

- Agile Certified Practitioner (PMI-ACP)® qualifications and training

- How Agile Certified Practitioner (PMI-ACP)® can benefit you?

- Program Management Professional (PgMP)® qualifications and training

- How Program Management Professional (PgMP)® can benefit you?

- Scrum (Agile Business Consortium) qualifications and training

- How Scrum (Agile Business Consortium) can benefit you?

- Praxis Framework™ qualifications and training

- Praxis Foundation course outline

- Praxis Practitioner course outline

- Praxis F&P course outline

- Agile and Scrum Foundation (ASF)

- Agile Scrum Master (ASM®)

- ITIL German

- Applied Business Architecture

- Service Management Essentials

- ITIL 4 FAQs

- ITIL 4 syllabus changes

- What is ITIL 4 Infographic

- Transforming IT Service Management Knowledge Into Practice With ITIL Practitioner

- The ITIL glossary of terms, definitions and acronyms

- ITIL Foundation Online

- Virtual (without exam)

- Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP®)

- Business Analyst

- BCS qualifications and training

- How BCS can benefit you?

- Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP®) qualifications and training

- How Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP®) can benefit you?

- Lean Six Sigma for Services

- Lean Six Sigma

- Lean Management

- Lean Six Sigma for Services qualifications and training

- How Lean Six Sigma for Services can benefit you?

- Lean Six Sigma for Services - Champion

- Lean Six Sigma for Services - Green Belt

- Lean Six Sigma for Services - Yellow Belt

- Automation Testing

- Practical Application Workshop

- Introduction to Cyber Security

- Cyber Security Expert

- Artificial Intelligence

- Robotic Process Automation

- Business Analytics

- Data Science

- Big Data and Hadoop

- Data Analyst

- Microsoft Azure

- Cloud Architect

- Digital Marketing

- Mobile Marketing

- Content Marketing

- Web Analytics

- Business Skills:

- Communication:

- Personal Effectiveness:

Learn more for less - up to 25% off! Click here to view all courses

- Blog categories

- Company Updates

- Learning and Development

- Diversity, Equality and Inclusion

- Project Management

- Software Testing

- Cloud Computing

- Mobile and Software Development

- AI and Machine Learning

- Big Data and Analytics

- Business and Leadership

- Business Analysis

10 failed projects and the lessons learned

By ilx team | 19 august 2019.

Every project teaches lessons with its successes and failures. Best practice courses highlight the importance of developing a mind-set of continuous learning from the outset of the project. In this blog we’ll look at 10 major public project failures and the lessons learnt from these mistakes.

Why should we analyse projects that failed?

Failed projects provide valuable lessons. Analysing failures can help to pinpoint weaknesses in project planning, execution, or team dynamics. By dissecting what went wrong, project teams can gain insights into the mistakes that were made and avoid repeating the same errors in the future.

Embracing failure as a learning opportunity fosters a culture of continuous improvement, which leads project teams to become more resilient, adaptable, and innovative.

10 projects that failed:

1. apple lisa.

In the early days of Apple, Lisa was the first GUI computer marketed at personal business users. It was supposed to be the first desktop computer that incorporated the now famous mouse, and a 5 MHz, 1MB RAM processor – the fastest of its kind back in 1983.

However, the project was a big failure. Only 10,000 computers were sold. It was such as failure that Steve Jobs was taken off the project and allocated to another project, the Macintosh. Apple Lisa overpromised and under-delivered, with a price-performance ratio that was significantly worse than had been expected.

Lesson learned:

The importance of stakeholder collaboration and transparency.

2. Crystal Pepsi

The early 1990s saw the trend for ‘light’ drinks emerge. In 1992, Pepsi launched Crystal Pepsi , a soft drink that tasted similar to regular Pepsi but was clear-coloured. Initially sales were good, mainly due to the curiosity factor, but soon dropped away to the point where Crystal Pepsi was withdrawn from the market just 2 years later.

The mistake of David Novak, creator of Cystal Pepsi — and Pepsi itself — was making too many assumptions about the product and market demand. Novak was even told by the bottlers that the drink needed to taste more like Pepsi. Unfortunately, he didn’t listen.

Don’t make assumptions about your audience. Leverage everyone’s expertise and verify statements before considering them fact.

3. Ford Edsel

It’s not often that Ford gets it wrong, but in the case of the Edsel , they failed on a big scale. Ford wanted to close the gap with General Motors and Chrysler. Having spent $250 million and 10 years developing the Edsel, by the time it came to the market the trend was for more compact cars.

Launched in 1957, the Edsel was considered overpriced, over-hyped, too big, and unattractive. By 1959, production was ceased.

Update a project’s business case and schedule during its lifecycle.

4. Computerised DMV

In the 1990s, the DMV tried to computerise their department to track drivers’ licences and vehicle registrations.

But after 6 years and $44 million, as well as ‘putting all their eggs into one basket’ with Tandem Computers, they discovered their computers were actually slower than the ones they replaced. On top of that, a state audit found that the DMV was violating contracting laws and regulations.

Processes should be followed, and any legal or regulatory constraints must be included in the project plan.

5. J.C. Penney’s 2011 rebrand

To wean customers away from their reliance on coupons, J.C. Penney introduced simpler price points and colour-coded price tags, and ran a marketing campaign to promote this strategy.

Customers found the new pricing structure confusing, and many items advertised never went on sale. Revenues dropped significantly and J.C. Penney had to admit failure.

The impact a lack of stakeholder and market research can have on a project.

6. Airbus A380

When the Airbus A380 was launched in 2007, much was expected of the airplane, but just 10 years later, they were being sold for no more than spare parts. The expected game-changer led to Airbus struggling to secure deals with airlines.

The A380 was expensive to produce, and Airbus’s production teams didn’t communicate and used different CAD programs. That mistake alone cost $6.1 billion . Furthermore, the second-hand market was non-existent because the planes were simply too big for any airline to make back their invested money.

The impact of poor internal communication and a business case that was built on initial sales, taking the second-hand market for granted.

7. Montreal’s Highway 15 overpass

In 2016, Montreal city officials found that an overpass for Highway 15 didn’t align with the design for the new Champlain Bridge nearby, which was also undergoing redevelopment.

So just a year after being built, the $11 million overpass was torn down . While changing design criteria can have expensive knock-on effects, there was an apparent lack of communication between projects here.

A lack of programme management meant the bridge and the overpass for the same highway were being constructed without the other being considered. The long-term planning and internal communication suffered as a result.

8. Knight Capital

The company’s stock market algorithm released in 2012 with code from an earlier build. It took just 30 minutes for a software glitch to see the company lose a massive $440 million and be forced into a merger a year later.

Although their CEO, Thomas Joyce, implied that the software bug could have happened to anyone, it is very likely that poor software development and inadequate testing models are more to blame for the defect in their trading algorithm.

Project targets and deadlines must be realistic to be achievable. Rushing a product can cause mistakes to be made.

9. Target’s failed entry into Canada

When Target said they were expanding into Canada, 81% of Canadian shoppers expressed interest in visiting them. It should have been a resounding success, but it wasn’t. Less than 2 years later, Target’s Chairman and CEO announced they were pulling out of Canada , closing all 133 stores.

Target misjudged the Canadian customer. Their stores did not feature the same low prices as the US stores, there were serious supply and distribution problems, and they opened too many stores too quickly.

The need for better resource and supply planning, as well as the impact of ineffectively managing stakeholder expectations.

10. Afghan forest camo pattern

Afghanistan’s landscape features around 2% woodland, yet this didn’t stop the US government from spending $28 million of taxpayers’ money on ‘forest’ pattern uniforms for the Afghan National Army. It was only chosen because the Afghan Defence Minister liked the design.

Ultimately, these were never used, so the money and uniforms were completely wasted. That particular forest pattern required a paid licence, while many patterns already owned by the army were more suitable for Afghanistan’s landscape.

Poor management led to a serious oversight, which stakeholder engagement and quality control would have prevented.

Common warning signs of a failing project

Throughout the 10 failed projects we’ve highlighted above, there are a number of common themes. Identifying and being mindful of these warning signs can help you avoid making the same mistakes.

Lack of interest

One warning sign may be stakeholder not attending meetings or providing feedback, as well as allocated tasks not being completed on time. It’s the project managers role to track assignments and ensure a high level of communication at all times. If you believe stakeholders are losing interest, call a meeting to reiterate the value of the project.

Learn more about how support (or lack of) from internal and external stakeholders can make or break a project.

Poor communication

It’s easy for members of the project team to become ‘lost’ and out of the loop with project progress, decisions, and reviews. Project managers should have a communication plan and automate as much as they can. This ensures everyone involved in the project is kept up-to-date constantly.

Discover how effective communication is essential to the success of projects, programmes and portfolios.

Lack of transparency

The more you try to cover up a problem or issue, the less transparency you have and the greater the problem becomes. Be honest. Issues do arise and the best way forward is to identify them as early as possible, notify stakeholders, including sponsors and customers, and work closely with them to resolve the issue.

Scope and budget creep

Don’t start the project until all the stakeholders are on the same page. Always ensure everyone has the scope statement to work from.

Find out how you can ensure your project budgets are based on reliable projections to avoid scope and budget creep .

Poor management oversight

Ensure everyone’s roles and responsibilities are well-defined. The project manager is accountable to other stakeholders.

How ILX can help train project managers

There will always be project failures. The key is to identify them as early as possible and work to resolve them before it’s too late, allowing you to minimise the damage.

It is a project manager’s responsibility to lead by example, and learn from other people’s mistakes. Training in one of our project management courses such as PRINCE2® , AgilePM® or APM PMQ , is a great way to help you develop these skills and improve your leadership qualities.

Free downloads

Megaprojects—mega failures? The politics of aspiration and the transformation of rural Kenya

- Special Issue Article

- Open access

- Published: 13 April 2021

- Volume 33 , pages 1069–1090, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Detlef Müller-Mahn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5266-195X 1 ,

- Kennedy Mkutu 2 &

- Eric Kioko 3

15k Accesses

15 Citations

35 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Megaprojects are returning to play a key role in the transformation of rural Africa, despite controversies over their outcome. While some view them as promising tools for a ‘big push’ of modernization, others criticize their multiple adverse effects and risk of failure. Against this backdrop, the paper revisits earlier concepts that have explained megaproject failures by referring to problems of managerial complexity and the logics of state-led development. Taking recent examples from Kenya, the paper argues for a more differentiated approach, considering the symbolic role infrastructure megaprojects play in future-oriented development politics as objects of imagination, vision, and hope. We propose to explain the outcomes of megaprojects by focusing on the ‘politics of aspiration’, which unfold at the intersection between different actors and scales. The paper gives an overview of large infrastructure projects in Kenya and places them in the context of the country´s national development agenda ‘Vision 2030′. It identifies the relevant actors and investigates how controversial aspirations, interests and foreign influences play out on the ground. The paper concludes by describing megaproject development as future making, driven by the mobilizing power of the ‘politics of aspiration’. The analysis of megaprojects should consider not only material outcomes but also their symbolic dimension for desirable futures.

Les mégaprojets jouent à nouveau un rôle clé dans la transformation de l'Afrique rurale, en dépit de leurs résultats controversés. Si certains les considèrent comme des outils prometteurs permettant un «grand pas » vers la modernisation, d’autres critiquent leurs multiples effets néfastes et leur risque d’échec. Dans ce contexte, l'article revisite des concepts antérieurs qui ont expliqué les échecs des mégaprojets en faisant référence aux problèmes de complexité managériale et à la logique du développement dirigé par l'État. L’article s’inspire d’exemples récents au Kenya et fait un plaidoyer pour une approche différenciée, en prenant en compte le rôle symbolique que jouent les mégaprojets d'infrastructure dans les politiques de développement orientées vers l'avenir en tant qu'objets d'imagination, de vision et d'espoir. Nous proposons d’expliquer les résultats des mégaprojets en nous concentrant sur la «politique de l’aspiration», qui se trouvent au croisement entre les différents acteurs et les différentes envergures. L’article donne un aperçu des grands projets d’infrastructure au Kenya et les positionne dans le contexte du programme de développement national du pays, «Vision 2030». Il identifie les acteurs concernés et examine la manière dont les aspirations, intérêts et influences étrangères controversés s’articulent sur le terrain. L’article conclut en décrivant le développement des mégaprojets comme étant créateur d’avenir, sous l’impulsion du pouvoir fédérateur de la «politique de l’aspiration». L'analyse des mégaprojets doit tenir compte non seulement des résultats matériels, mais également de leur dimension symbolique qui forge un avenir attrayant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Are Mega Projects Inherently Undemocratic? Field Narratives from Mega Projects Sites in Bangladesh

The Challenge of Megacities in India

Scientific and institutional capacity for complex development of the russian arctic zone in the medium and long term perspectives

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Africa is currently witnessing an unprecedented boom of investments in large infrastructure projects, commonly referred to as megaprojects. New roads, railways, airports, deepwater harbours, power lines, dams and irrigation schemes are mushrooming all over the continent. Megaproject development, as it seems, is implemented with the force of bulldozers, cutting corridors of economic growth into rural hinterlands and pushing the frontiers of modernization towards the margins. This present phase of spatial development began shortly after the year 2000, accompanied by large-scale land acquisitions and a ‘new scramble for Africa’ (Carmody 2011 ), and gained momentum when China announced its Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 (Chen 2016 ). A growing body of literature provides interpretations of the historical legacies of the ‘infrastructure scramble’ (Enns and Bersaglio 2019 ), highlighting the return of state-led development visions (Mosley and Watson 2016 ), modernist logics (Dye 2019 ), green economy (Bergius et al. 2020 ) and other forms of land investments (Lind et al. 2020 ), the emergence of a state-building frontier (Stepputat and Hagmann 2019 ) and the underlying fascination for ‘dreamscapes of modernity’ (Jasanoff and Kim 2015 ; Müller-Mahn 2020 ). Yet the resurrection of megaprojects is hard to understand in so far as large-scale projects have long been criticized for notorious under-performance and cost overrides, a phenomenon described as the ‘megaprojects paradox’ (Flyvbjerg et al. 2003 ). Against this backdrop, the question arises as to how we can explain the renewed fascination for ‘thinking big’ in spatial development, and the often rather meagre outcomes of megaprojects.

This paper takes cases from Kenya to investigate the political rationality and performance of megaprojects in the context of national development. Kenya is a particularly telling example, since it is the country with the highest concentration of large infrastructure projects in East Africa (Enns 2017 ). In line with a neoliberal, investor-friendly tradition, successive Kenyan governments have attempted to attract foreign and domestic capital, and to channel funds into showpieces of progress. Development corridors play an important role in this context, while national planning envisions transformation into a middle-income country. Recent studies have highlighted various aspects of corridor development in East Africa, such as territorial restructuring (Greiner 2016 ), societal exclusion and inclusion (Chome 2020 ), complex rural responses (Enns 2017 , 2019 ), diverse forms of knowledge production and resistance by rural land users (Enns and Bersaglio 2020 ), the use of discursive tactics and spatial imagination (Aalders 2020 ), and the importance of corridors as instruments for the expansion of global value chains (Dannenberg et al. 2018 ).

The paper contributes to the debate on megaproject development by highlighting an aspect, which has attracted relatively little attention. We propose to view megaprojects as huge constructions that explicitly affect the future, or more specifically, as tools of ‘future-making’ in the sense proposed by Appadurai ( 2013 ). Appadurai distinguishes anticipation, imagination and aspiration as cultural practices that make the future an issue in the present. While anticipation refers to probabilities, and imagination to designs and collectively held beliefs, aspiration aims at desirable futures, possibilities and hope. Thus, we assume that aspiration is important for understanding how megaprojects are conceived and performed as promises of future improvements, as pathways to modernity, and—to use a metaphor—as ‘beacons of hope’. We propose to consider megaproject development as part of the ‘politics of aspiration’, in which hope is produced and performed in public debates, political negotiations, and planning processes.

The history of large-scale projects in Africa saw a first boom after independence, when national development followed visions of modernity and state-driven development and was aimed at rapid societal transformation (Scott 1998 ). The character of large infrastructure projects changed substantially after the neoliberal turn in the 1980s. With the roll-back of the state, ‘the envisioning of megaprojects was limited to those that could at least be partially funded by the private sector’ (Schindler et al. 2019 : 2). Today, megaprojects are back on the political agenda, but embedded in complex institutional settings. They involve governmental and non-governmental actors, the private sector and international funding agencies, resulting in a more decentralized and partially fuzzy governance structure (Mosley and Watson 2016 ).

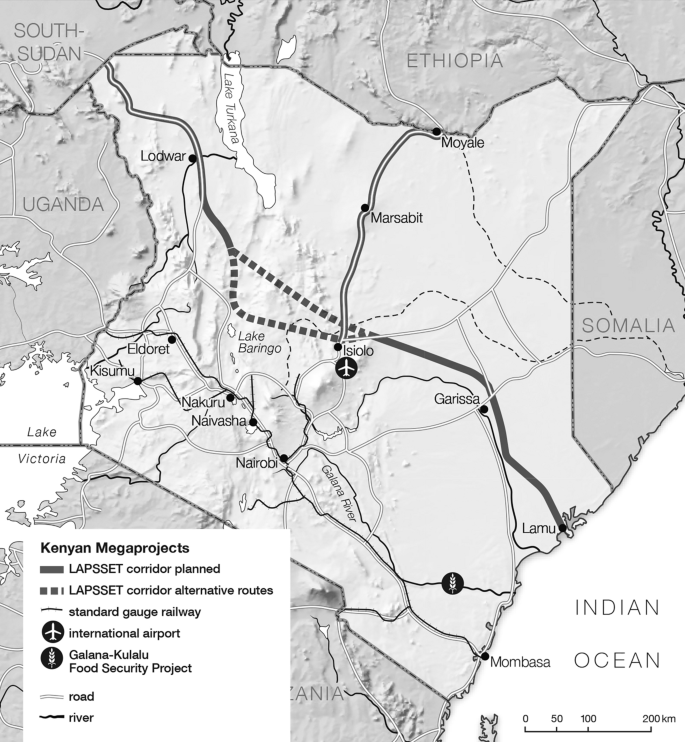

We will first explain our conceptual framework in respect of the so-called ‘megaproject paradox’ and the significance of aspiration. Then we will present three cases of megaprojects in Kenya: the standard gauge railway from Mombasa to Nairobi, the LAPSSET corridor with the construction of an international airport and an abattoir at Isiolo, and the Galana-Kulalu Food Security Project. In the discussion, we will come back to the question formulated in the title of this paper by looking at the relationship between the politics of aspiration and the outcome of such megaprojects.

Conceptual explanations for the success or failure of megaprojects

The history of problematic megaprojects may be traced back to the Tower of Babel, which became a metaphor for over-ambitious construction schemes ending up in chaos. Until today, megaproject developments arouse ambivalent feelings, fluctuating between enthusiasm and scepticism. James Scott ( 1998 ), in his seminal work entitled Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed , presents a number of cases exemplifying the ‘fiasco’ and even ‘full-fledged disaster’ of large state-led projects. Yet there are no absolute criteria for characterizing a project as ‘mega’ or as a failure, since these are both relative terms. Megaprojects may be viewed as huge development schemes which are particularly ambitious, expensive, and difficult to manage, with a tendency to fail to meet the initial objectives (Schindler et al. 2019 ). On the basis of a literature review, we distinguish four conceptual approaches to explaining the outcome of megaprojects.

The first of these four approaches focuses on the complexity of large-scale engineering projects, which are generally difficult to manage and control (Salet et al. 2013 ). Flyvbjerg et al. ( 2003 ) present a number of spectacular multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects, such as the Channel Tunnel, Denver International Airport, and other examples in the Global North, which started with high-flying expectations and ended up with extreme cost-overruns. The examples highlight the gap between promises and achievements, a phenomenon the authors call the ‘megaprojects paradox’. They argue that the disappointing performance of megaprojects is not accidental, but part of the project logic. Exaggerated promises, weak governance structures, lack of control, and insufficient accountability serve to generate exceedingly high profits. In sub-Saharan Africa, this combination of problems is all too common (Sobják 2018 ).

A second line of explanation links the outcome of megaprojects to political regimes and the state. Scott ( 1998 ) relates the failure of large-scale development schemes to a combination of several elements culminating in ‘high modernism’, i.e. a system of beliefs that relies on science and technology, the transformation of nature, and the power of authoritarian states. On the basis of case studies of large schemes from various parts of the world, including an example from Tanzania, Scott argues that ‘it is the systematic, cyclopean shortsightedness of high-modernist agriculture that courts certain forms of failure’ (Scott 1998 : 264). State-led, top-down projects do not work, because they do not fit into local conditions. This argument is supported by recent studies on high-modernist megaprojects on the African continent. Van der Westhuizen ( 2007 ), for example, points to the importance of political symbolism to explain the costly construction of Gautrain, a metropolitan high-speed train network in South Africa, which was aimed not only at improving public transport but also at presenting South Africa as a modern state on the occasion of the 2010 Football World Cup. Ballard ( 2017 ) interprets housing schemes in South Africa as attempts to strengthen the legitimacy of the state, especially in the context of upcoming elections. This explains why housing megaprojects serve other interests beyond their material dimension. Ballard and Rubin ( 2017 ) attribute the shift from small to big housing schemes to the ‘megaprojects policy turn’ in South Africa in the years 2014–2015. In a similar vein, Hannan and Sutherland ( 2014 ) explore controversies around urban megaprojects in Durban, South Africa, which they attribute to conflicts between short- and long-term goals, and between pro-poor and pro-growth orientations. Projects are criticized for high economic risk, frequent delays, lack of transparency and accountability, and as ‘elite playing fields’ (Hannan & Sutherland 2014 : 2).

A third argument points to the vulnerability of megaprojects in the context of social and economic change. Ansar et al. ( 2017 ) give an overview of ‘theories of big’, which they interpret as a tendency to undertake ever bigger projects under conditions of economies of scale. They argue that, contrary to their ambitious goals, big projects are characterized by a particularly high degree of ‘fragility’ due to their exposure to uncertainties. The authors conclude that ‘to automatically assume that “bigger is better”, which is common in megaproject management, is a recipe for failure’ (Ansar et al. 2017 : 3).

Finally, a fourth approach highlights the symbolic dimension of large-scale infrastructure projects, especially regarding their role as symbols of progress and focal points of aspiration. Megaprojects capture the imagination, they are ‘imagined before they come to exist’ (Schindler et al. ( 2019 : 2), and in doing so, they create ‘imagined futures’ (Beckert 2016 ) which serve as pacemakers of development. Imagined futures may become effective drivers of change, if the imagination is shared by a sufficiently large number of actors, based on the promises of transformation, and the ‘enchantments of infrastructure’ (Harvey and Knox 2012 ). The power of megaprojects comes not only from their physical impact but also from the power they exert over the minds of the people affected by rural transformation. Thus, they may be considered as aspirational projects aiming at ‘dreamscapes of modernity’ (Jasanoff and Kim 2015 ; Müller-Mahn 2020 ). Such aspirations promote speculation and jostling for position, which can easily lead to conflicts (Elliot 2016 ). Further, interference with land rights, ecology and social conditions may lead to project delays if these injustices are protested. Lastly, the projects may be impractical, since they are largely driven by elite imaginations with little attention to participatory processes involving the local communities. This suggests that local input is not only morally desirable but also practically necessary (Stetson 2012 ; Mkutu et al. 2019 ).

Development planning in Kenya

The first megaproject in Kenya was the nearly 600-mile-long railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria, constructed in 1896–1901, which aimed to consolidate British control in the region and succeeded in opening up the southern part of Kenya (Jedwab et al. 2015 ). In the postcolonial period, there was an intermittent focus on infrastructural development as a driver of economic growth. After independence, Kenya’s economic policy was formulated as African socialism Footnote 1 —although it was in fact a mixed economic policy, focusing chiefly on high potential areas (Zelezer 1991 ). Later policies briefly favoured redistributive ideals, and then donor-driven structural adjustment policies took over in the 1980s in which the private sector and civil society were seen as key drivers of growth. Policies produced during this period were aimed at employment opportunities in industry and agriculture, while roads, power and water supply were prioritized. Industrialization continued to be emphasized in the 1990s and again in the 2000s.

The year 2008 saw the creation of Kenya’s Vision 2030 whose aim was the pursuit of global competitiveness and prosperity in order to offer Kenyans a high quality of life by 2030. Key features of the plan include investment in the arid and semi-arid lands (ASAL), focusing on infrastructural development to connect different parts of the country through roads, railways, ports, airports, waterways and telecommunications, which would then stimulate private sector investments. The first medium-term plan (MTP) of Vision 2030 (2008–2013) outlined the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport (LAPSSET) Corridor project. According to claims by the LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority, the corridor will ‘inject between 2 and 3% of GDP into the [Kenyan] economy’. Officials further estimate that LAPSSET might even yield higher growth rates ‘of between 8 and 10% of GDP when generated and attracted investments finally come on board’. Footnote 2 These claims lie behind the project slogan: ‘Building Africa’s Transformative and Game Changer Infrastructure to Deliver a Just and Prosperous Kenya’. As Browne ( 2015 :7) rightly points out, LAPSSET ‘echoes the modernist developmental approach of African governments in the 1960s but differs from the infrastructural visions of the past in both its magnitude and rationale’. It is part of a continent-wide ambitious development vision, which copies models of transboundary integration and modernization from Europe and North America (Chome et al. 2020 ).

In 2012, in line with Vision 2030, the government produced Sessional Paper No. 8 of 2012 ‘National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Northern Kenya and other Arid Lands’, which deliberately focused on reversal of the previous policy of concentrating development efforts on high potential areas. The paper articulated the need to close the gap between these areas and the rest of the country, while at the same time protecting and promoting the mobility and institutional arrangements which are so essential to productive pastoralism amidst the threat of climate change and the need for food security. The paper acknowledged the potentials of ASAL regarding cross-border trade, livestock, tourism, natural minerals and renewable energy, with special mention of the LAPSSET project.

The second MTP (2013–2017) continued to emphasize infrastructure development, amongst others, while the third MTP (2018–2022) prioritizes a so-called Big Four Agenda: food security (which includes irrigation and development of the blue economy), affordable housing, affordable healthcare for all and manufacturing (which includes creation of special economic and industrial parks and increasing agro-processing). Additionally, it proposes oil and minerals development, and the expansion and modernizing of infrastructure. These plans are considered inclusive by virtue of the devolved structure now in place following Kenya´s 2010 constitution.

One problem with this timeline of Kenya’s visions is that implementation is characteristically poor (Zelezer 1991 ). Referring specifically to the LAPSSET project, Browne ( 2015 ) comments that there have been delays in implementation, confused and sometimes contradictory announcements, and many concerns over land grabbing and compensation issues, as well as social and environmental impacts, raised by a very active civil society. Below, we present a number of case studies as examples of megaproject development in Kenya.

The case of the Standard Gauge Railway

The 485 km long Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Nairobi to Mombasa was completed in 2017 as Kenya’s largest infrastructure project since independence. Footnote 3 It was funded and built by the Chinese at a cost of $3.2 billion US dollars loaned from China Exim Bank and is also operated by the Chinese. Footnote 4 As of June 2019, Kenya owes $6.5 billion to China following the further extension of the railway to Naivasha, Footnote 5 but China declined further loans to take the railway to Kisumu as originally planned. Footnote 6 The project has been mired in controversy due to the non-competitive manner in which the Chinese company was awarded the tender. Footnote 7

The final terminus of the SGR is to be a dry port in Maai Mahiu near Naivasha town, partially occupying land which was privately grabbed by high ranking politicians. Footnote 8 Around 40 km away in Suswa town, Narok County, 405 ha of land is being set aside for an industrial park. Footnote 9 The SGR was intended to recoup its costs through cargo transportation, although so far it is mainly a passenger service. In September 2019, the Cabinet Secretary for Infrastructure issued a directive that all cargo be transported by rail on the new railway from Mombasa to Nairobi and on to Naivasha, thus, bypassing Mombasa town. This met with strong protests over the loss of thousands of jobs in clearing and forwarding agencies, and in the fuel and transport sectors, and a shrinkage of Mombasa’s economy by over 16%. Footnote 10 The directive was subsequently officially suspended in October 2019, Footnote 11 likely due to pressure from elites who own trucking companies operating between Kenya and the Great Lakes countries. Footnote 12

A World Bank report highlights numerous negative impacts of the SGR project in Narok, such as increasing crime and prostitution, pollution and deforestation, with particularly severe consequences for local pastoralists. Footnote 13 An estimated 10,000 families are expected to be displaced by the inland container depot and associated developments. A Maasai community went to court to oppose the developments, saying that the 1619 ha they were offered to replace their land is insufficient. Footnote 14 The shaky provisions for compensation of community-land owners have been described, but the enactment of the Land Value Index Act (2018) has made it even more difficult to get timely and adequate compensation. The Act is meant to prevent delays over compensation disputes by allowing the government to go ahead with the project as cases are resolved, but there are concerns that this could also allow community rights to be overridden more easily. Further, the Act only recognizes the market value of the land, and it only acknowledges permanent occupiers, which is insensitive to pastoralist realities and the value of the land for pastoralist livelihoods. Currently, compensation is marred by corruption, including the taking of bribes by Maasai elites. Footnote 15 Furthermore, some influential persons, including members of parliament, have bought land cheaply from locals and sold it at exorbitant prices to the Chinese company constructing the SGR. In Suswa, one man’s farm was bought for KES 40,000 (USD 400) and sold on for millions. It is expected that land sales will continue to increase in the area in which former Maasai group ranches have been extensively subdivided. Footnote 16 When interviewed, a Maasai elder explained his fears concerning the loss of pasture and water in the Kedong valley in which Suswa town is located:

Changes are coming, the previous life we were living seems to be gone… We might have to start zero grazing (bringing cattle feed), when Kedong is gone… Now we are being pushed out. What will happen? People will suffer...our living will be like Kibera (slum in Nairobi). Footnote 17

This case illustrates how weak land laws allow elites to benefit from infrastructure developments at the expense of marginalized citizens. Poor planning of such a huge project, which is at the same time dominated by elite visions, caused the project to become a financial failure and transferred the debt burden to future generations of Kenyan taxpayers.

LAPSSET projects: Isiolo International Airport and Abattoir

Like the SGR, projects in the LAPSSET corridor such as the upgrading of the small airfield of Isiolo to an international airport have raised temperatures over land rights, with irregularities in respect of land acquisition, resettlement and compensation. Covering an area of 260 ha, the airport terminal lies in Isiolo County, while the runway extends into Meru County. The total cost for the Kenyan government amounts to 27 million US dollars. At its opening, the airport was heralded as a ‘game changer’ for the economy of the northern counties. However, the airport, which had been built for over 6000 passengers per week, currently operates far below its capacity, handling only one small weekly flight (Atieno 2019 ). Moreover, the airport is still not equipped to handle commercial or cargo flights because it lacks a control tower, landing lights and a sufficiently long runway. Footnote 18 One of the immediate challenges has been the downturn in the global demand for the soft drug miraa (also known as khat ), which was banned in Europe in 2017. The plant is grown widely in Meru, and it was anticipated that the trade in miraa would benefit greatly from the facility. Another challenge has been delay in the completion of the Isiolo abattoir, to be discussed below (Atieno 2019 ). Thus, the current failure of the airport is related to its complex interdependency with other segments of the LAPSSET megaproject.

The airport was built on trust land—an old designation referring to land owned on a communal basis, often by pastoralist groups, and held in trust by local authorities. Such land was compulsorily acquired by the government or grabbed by elites, sometimes in league with local councils, as rights holders were rarely aware of their rights to consultation, appeal and compensation or relocation, and had little capacity to fight for them. The Land Act of 2012 and the Community Land Act of 2016 re-designated trust land as community land and strengthened the legal framework for its users, providing for registration by communities. This will protect them against land grabbing and allow direct compensation in the event of compulsory government acquisition. However, the process of implementation of this law is slow, even as the pace of change in northern Kenya is rapid.

In 2004, a team of councillors and elders was appointed to look at the number of people who would be affected by the airport project. Footnote 19 A ballot process for which people paid KES 1000 (USD 10) was used to allocate replacement plots to displaced residents. However, initial estimates of those displaced swelled, and the situation became increasingly complicated. Outsiders also benefited from allocations. Footnote 20 In a World Bank report, a former county council administrator described the confusion:

The initial 700 were to be relocated to Mwangaza, but the number increased over time to 1,500. As a result, some of the people were relocated to Kiwanjani location (Wabera Ward) but there were only 450 plots, and 50 squatters were already occupying the area, so approximately 400 in number were to move to Chechelesi, which had 1,900 plots. However, although the ballot was done, no land has yet been given out. Tension resulting from political interference and the change of leadership meant that even the Mwangaza area has not yet been occupied by the allocated people …. It’s now more than politics and has turned into a blame game. Footnote 21

The process was marred by delays and also by double allocation of new plots, which is the result of both corruption and confusion. The situation was further complicated by devolution. Several plots were acquired by elites following the passing of the mantle from the former Isiolo County Council to the County Government in 2013. A bishop estimated that there were around 100 internally displaced households as a result of the flawed relocations, and he believed that the new county government had behaved irregularly. Chiefs and ward administrators concurred that the county government had grabbed and consolidated 10 to 20 plots that were balloted, and later prepared a new fake map to facilitate the sale or gift of the plots to their cronies, especially in the Chechelesi area. Illegally produced and invalid documents were given out. In the words of a local chief, ‘the problem is corruption within the land office’.

Several respondents warned of the potential for ethnopolitical conflict as a result of the airport expansion. The runway extends into Nyambene in Meru County, where people who lost their land for construction purposes have been compensated, while those affected in Isiolo have not, because here the land was trust land. This plays into an existing volatile boundary dispute between Isiolo and Meru counties which has already been exacerbated as a result of LAPSSET, since the boundary determines which county benefits from compensation and economic development in the disputed area.

Interestingly, a top official from the Vision 2030 directorate denied in an interview that genuine people had not been compensated and reiterated that LAPSSET is a game changer with positive effects for the local population. Footnote 22 This viewpoint fails to acknowledge that not everyone is a winner from this project, and that shared prosperity may remain a dream due to institutional weaknesses, corruption, elite capture and pre-existing ethnopolitical competition.

Another example to illustrate the complexity of activities tied into the LAPSSET corridor is the construction of an abattoir at Isiolo town. Isiolo Holding Ground (also known as Livestock Marketing Division or LMD) is a 124,200 ha site, occupying parts of Burat and Oldonyiro wards, and bordering Laikipia, Samburu and Meru counties (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock Development and Marketing, 2006). It was established by the colonial government as a disease control buffer zone for protecting settlers’ cattle from pastoralist cattle migrating southwards during times of drought, and for quarantining and livestock marketing purposes. The ground continues to be used for quarantining and disease screening, as well as fattening and watering, but for some years it has not been operating as effectively as intended, due to poor management, land claims and overgrazing. It is occupied by a number of users including different armed pastoral groups belonging to Dorobo ( iltorrobo , hunter gatherers turned Maasai), Samburu, Turkana, Meru and settled Somali communities.

In line with other planned developments in northern Kenya, the new abattoir is expected to boost the economy of the north through meat export and to allow farmers to receive direct payment for their livestock without being exploited by middlemen. It has the capacity to slaughter 1000 sheep and goats, 200 cows and 100 camels daily. Realization of the vision was delayed due to lack of funds provided by the previous county government and poor workmanship, but there are hopes that private investment and World Bank funds may help to make up the shortfall. Footnote 23 In an interview, an official from the LAPSSET Corridor Development Authority was very positive about the potential for international export of animal products, saying that ‘this abattoir will be one of the major economic achievements that can facilitate growth along this corridor especially within the pastoralist counties’.

In contrast to the airport, there was a general sense of optimism and hope amongst many community members regarding the abattoir. It may be that this aspect of Vision 2030 is truly appropriate to local needs and more likely to bring shared prosperity, once the problems have been overcome. Further, its potential success does not rely on other infrastructural developments, although it does harmonize with the airport plans. Some concerns remain, however, such as a potential rise in conflict due to the large number of people from different ethnic groups settled in the LMD, so that the improved market for livestock could potentially exacerbate cattle raiding for cash. Footnote 24 Lastly, Isiolo abattoir was initially envisioned to serve the neighbouring counties, but the governments of three other counties have decided to build their own.

Galana-Kulalu: a failed ‘million-acre’ food security project

Large-scale agricultural development schemes are not new in Kenya. From the mid-1950s, the colonial government sets up the Perkerra, Hola and Mwea-Tebere irrigation schemes on ‘native reserves’. After independence, the Ministry of Agriculture took over the management of these projects, and in 1966, the National Irrigation Board (NIB) Footnote 25 was established with the mandate to develop, improve and manage national irrigation schemes in Kenya (Ngigi 2002 ). NIB spearheaded the development of Ahero, Bunyala, West Kano and Bura irrigation schemes between the mid-1970s and early 1980s.

Closely related to these projects is the million-acre idea, which is traceable to the early 1960s when focus shifted to the re-Africanization project dubbed the ‘million-acre settlement scheme’. It targeted lands that the colony had previously set aside for European settlement (Bradshaw 1990 ; Chambers 1969 ; Kanyinga 2009 ; Leo 1981 ). The million-acre scheme aimed at land redistribution and conferment of tenure rights on indigenous communities for settlement and agricultural development, while the large irrigation schemes were a response to food security challenges and the management of risks associated with unpredictable rainfall patterns. Irrigation and settlement schemes are driven by the politics of aspiration, because their purpose goes beyond addressing the underlying challenges. Essentially, they are central to the realization of the independence dream and are, thus, designed to win the support of the masses and to draw potential international development aid. The big promises justified external financing of such projects. For example, between 1977 and 1986, the World Bank financed the Bura Irrigation Project to the tune of USD 40 million.

To what extent have these centralized projects lived up to expectations? About six decades on, most public irrigation schemes in Kenya perform way below average (Muema et al. 2018 ). Ngigi ( 2002 ) notes that ‘the intended benefit of improving the living standards, to say the least, has not been realised’ and that some, like Bura, are no longer functional. Moreover, some irrigation schemes and large-scale agricultural investments are linked to human rights abuses especially through land dispossession (Otieno 2016 ). However, central to the failure of these schemes is the complexity of management and control as exemplified by Flyvbjerg et al. ( 2003 ). Bradshaw ( 1990 ) blames this on challenges around ownership, management, uneven resource distribution, water allocation and scarcity, which contribute to underdevelopment.