How to Start Writing Fiction: The Six Core Elements of Fiction Writing

Jack Smith and Sean Glatch | June 14, 2023 | 4 Comments

Whether you’ve been struck with a moment of inspiration or you’ve carried a story inside you for years, you’re here because you want to start writing fiction. From developing flesh-and-bone characters to worlds as real as our own, good fiction is hard to write, and getting the first words onto the blank page can be daunting.

Daunting, but not impossible. Although writing good fiction takes time, with a few fiction writing tips and your first sentences written, you’ll find that it’s much easier to get your words on the page.

Let’s break down fiction to its essential elements. We’ll investigate the individual components of fiction writing—and how, when they sit down to write, writers turn words into worlds. Then, we’ll turn to instructor Jack Smith and his thoughts on combining these elements into great works of fiction. But first, what are the elements of fiction writing?

Introduction to Fiction Writing: The Six Elements of Fiction

Before we delve into any writing tips, let’s review the essentials of creative writing in fiction. Whether you’re writing flash fiction , short stories, or epic trilogies, most fiction stories require these six components:

- Plot: the “what happens” of your story.

- Characters: whose lives are we watching?

- Setting: the world that the story is set in.

- Point of View: from whose eyes do we see the story unfold?

- Theme: the “deeper meaning” of the story, or what the story represents.

- Style: how you use words to tell the story.

It’s important to recognize that all of these elements are intertwined. You can’t build the setting without writing it through a certain point of view; you can’t develop important themes with arbitrary characters, etc. We’ll get into the relationship between these elements later, but for now, let’s explore how to use each element to write fiction.

1. Fiction Writing Tip: Developing Fictional Plots

Plot is the series of causes and effects that produce the story as a whole. Because A, then B, then C—ultimately leading to the story’s climax , the result of all the story’s events and character’s decisions.

If you don’t know where to start your story, but you have a few story ideas, then start with the conflict . Some novels take their time to introduce characters or explain the world of the piece, but if the conflict that drives the story doesn’t show up within the first 15 pages, then the story loses direction quickly.

That’s not to say you have to be explicit about the conflict. In Harry Potter, Voldemort isn’t introduced as the main antagonist until later in the first book; the series’ conflict begins with the Dursley family hiding Harry from his magical talents. Let the conflict unfold naturally in the story, but start with the story’s impetus, then go from there.

2. Fiction Writing Tip: Creating Characters

Think far back to 9th grade English, and you might remember the basic types of story conflicts: man vs. nature, man vs. man, and man vs. self. The conflicts that occur within stories happen to its characters—there can be no story without its people. Sometimes, your story needs to start there: in the middle of a conversation, a disrupted routine, or simply with what makes your characters special.

There are many ways to craft characters with depth and complexity. These include writing backstory, giving characters goals and fatal flaws, and making your characters contend with complicated themes and ideas. This guide on character development will help you sort out the traits your characters need, and how to interweave those traits into the story.

3. Fiction Writing Tip: Give Life to Living Worlds

Whether your story is set on Earth or a land far, far away, your setting lives in the same way your characters do. In the same way that we read to get inside the heads of other people, we also read to escape to a world outside of our own. Consider starting the story with what makes your world live: a pulsing city, the whispered susurrus of orchards, hills that roil with unsolved mysteries, etc. Tell us where the conflict is happening, and the story will follow.

4. Fiction Writing Tip: Play With Narrative Point of View

Point of view refers to the “cameraman” of the story—the vantage point we are viewing the story through. Maybe you’re stuck starting your story because you’re trying to write it in the wrong person. There are four POVs that authors work with:

- First person—the story is told from the “I” perspective, and that “I” is the protagonist.

- First person peripheral—the story is told from the “I” perspective, but the “I” is not the protagonist, but someone adjacent to the protagonist. (Think: Nick Carraway, narrator of The Great Gatsby. )

- Second person—the story is told from the “you” perspective. This point of view is rare, but when done effectively, it can create a sense of eeriness or a personalized piece.

- Third person limited—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator usually writes from the perspective of one or two characters.

- Third person omniscient—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator knows what is happening in each character’s heads and in the world at large.

If you can’t find the right words to begin your piece, consider switching up the pronouns you use and the perspective you write from. You might find that the story flows onto the page from a different point of view.

5. Fiction Writing Tip: Use the Story to Investigate Themes

Generally, the themes of the story aren’t explored until after the aforementioned elements are established, and writers don’t always know the themes of their own work until after the work is written. Still, it might help to consider the broader implications of the story you want to write. How does the conflict or story extend into a bigger picture?

Let’s revisit Harry Potter’s opening scenes. When we revisit the Dursleys preventing Harry from knowing about his true nature, several themes are established: the meaning of family, the importance of identity, and the idea of fate can all be explored here. Themes often develop organically, but it doesn’t hurt to consider the message of your story from the start.

6. Fiction Writing Tip: Experiment With Words

Style is the last of the six fiction elements, but certainly as important as the others. The words you use to tell your story, the way you structure your sentences, how you alternate between characters, and the sounds of the words you use all contribute to the mood of the work itself.

If you’re struggling to get past the first sentence, try rewriting it. Write it in 10 words or write it in 200 words; write a single word sentence; experiment with metaphors, alliteration, or onomatopoeia . Then, once you’ve found the right words, build from there, and let your first sentence guide the style and mood of the narrative.

Now, let’s take a deeper look at the craft of fiction writing. The above elements are great starting points, but to learn how to start writing fiction, we need to examine the craft of combining these elements.

Primer on the Elements of Fiction Writing

First, before we get into the craft of fiction writing, it’s important to understand the elements of fiction. You don’t need to understand everything about the craft of fiction before you start keying in ideas or planning your novel. But this primer will be something you can consult if you need clarification on any term (e.g., point of view) as you learn how to start writing fiction.

The Elements of Fiction Writing

A standard novel runs between 80,000 to 100,000 words. A short novel, going by the National Novel Writing Month , is at least 50,000. To begin with, don’t think about length—think about development. Length will come. It is true that some works lend themselves more to novellas, but if that’s the case, you don’t want to pad them to make a longer work. If you write a plot summary—that’s one option on getting started writing fiction—you will be able to get a fairly good idea about your project as to whether it lends itself to a full-blown novel.

For now, let’s think about the various elements of fiction—the building blocks.

Writing Fiction: Your Protagonist

Readers want an interesting protagonist , or main character. One that seems real, that deals with the various things in life we all deal with. If the writer makes life too simple, and doesn’t reflect the kinds of problems we all face, most readers are going to lose interest.

Don’t cheat it. Make the work honest. Do as much as you can to develop a character who is fully developed, fully real—many-sided. Complex. In Aspects of the Novel , E.M Forster called this character a “round” characte r. This character is capable of surprising us. Don’t be afraid to make your protagonist, or any of your characters, a bit contradictory. Most of us are somewhat contradictory at one time or another. The deeper you see into your protagonist, the more complex, the more believable they will be.

If a character has no depth, is merely “flat,” as Forster terms it, then we can sum this character up in a sentence: “George hates his ex-wife.” This is much too limited. Find out why. What is it that causes George to hate his ex-wife? Is it because of something she did or didn’t do? Is it because of a basic personality clash? Is it because George can’t stand a certain type of person, and he didn’t realize, until too late, that his ex-wife was really that kind of person? Imagine some moments of illumination, and you will have a much richer character than one who just hates his ex-wife.

And so… to sum up: think about fleshing out your protagonist as much as you can. Consider personality, character (or moral makeup), inclinations, proclivities, likes, dislikes, etc. What makes this character happy? What makes this character sad or frustrated? What motivates your character? Readers don’t want to know only what —they want to know why .

Usually, readers want a sympathetic character, one they can root for. Or if not that, one that is interesting in different ways. You might not find the protagonist of The Girl on the Train totally sympathetic, but she’s interesting! She’s compelling.

Here’s an article I wrote on what makes a good protagonist.

Also on clichéd characters.

Now, we’re ready for a key question: what is your protagonist’s main goal in this story? And secondly, who or what will stand in the way of your character achieving this goal?

There are two kinds of conflicts: internal and external. In some cases, characters may not be opposing an external antagonist, but be self-conflicted. Once you decide on your character’s goal, you can more easily determine the nature of the obstacles that your protagonist must overcome. There must be conflict, of course, and stories must involve movement. Things go from Phase A to Phase B to Phase C, and so on. Overall, the protagonist begins here and ends there. She isn’t the same at the end of the story as she was in the beginning. There is a character arc.

I spoke of character arc. Now let’s move on to plot, the mechanism governing the overall logic of the story. What causes the protagonist to change? What key events lead up to the final resolution?

But before we go there, let’s stop a moment and think about point of view, the lens through which the story is told.

Writing Fiction: Point of View as Lens

Is this the right protagonist for this story? Is this character the one who has the most at stake? Does this character have real potential for change? Remember, you must have change or movement—in terms of character growth—in your story. Your character should not be quite the same at the end as in the beginning. Otherwise, it’s more of a sketch.

Such a story used to be called “slice of life.” For example, what if a man thinks his job can’t get any worse—and it doesn’t? He started with a great dislike for the job, for the people he works with, just for the pay. His hate factor is 9 on a scale of 10. He doesn’t learn anything about himself either. He just realizes he’s got to get out of there. The reader knew that from page 1.

Choose a character who has a chance of undergoing change of some kind. The more complex the change, the better. Characters that change are dynamic characters , according to E. M. Forster. Characters that remain the same are static characters. Be sure your protagonist is dynamic.

Okay, an exception: Let’s say your character resists change—that can involve some sort of movement—the resisting of change.

Here’s another thing to look at on protagonists—a blog I wrote: https://elizabethspanncraig.com/writing-tips-2/creating-strong-characters-typical-challenges/

Writing Fiction: Point of View and Person

Usually when we think of point of view, we have in mind the choice of person: first, second, and third. First person provides intimacy. As readers we’re allowed into the I-narrator’s mind and heart. A story told from the first person can sometimes be highly confessional, frank, bold. Think of some of the great first-person narrators like Huck Finn and Holden Caulfield. With first person we can also create narrators that are not completely reliable, leading to dramatic irony : we as readers believe one thing while the narrator believes another. This creates some interesting tension, but be careful to make your protagonist likable, sympathetic. Or at least empathetic, someone we can relate to.

What if a novel is told in first person from the point of view of a mob hit man? As author of such a tale, you probably wouldn’t want your reader to root for this character, but you could at least make the character human and believable. With first person, your reader would be constantly in the mind of this character, so you’d need to find a way to deal with this sympathy question. First person is a good choice for many works of fiction, as long as one doesn’t confuse the I-narrator with themselves. It may be a temptation, especially in the case of fiction based on one’s own life—not that it wouldn’t be in third person narrations. But perhaps even more with a first person story: that character is me . But it’s not—it’s a fictional character.

Check out my article on writing autobiographical fiction, which appeared in The Writer magazine. https://www.writermag.com/2018/07/31/filtering-fact-through-fiction/

Third person provides more distance. With third person, you have a choice between three forms: omniscient, limited omniscient, and objective or dramatic. If you get outside of your protagonist’s mind and enter other characters’ minds, you are being omniscient or godlike. If you limit your access to your protagonist’s mind only, this is limited omniscience. Let’s consider these two forms of third-person narrators before moving on to the objective or dramatic POV.

The omniscient form is rather risky, but it is certainly used, and it can certainly serve a worthwhile function. With this form, the author knows everything that has occurred, is occurring, or will occur in a given place, or in given places, for all the characters in the story. The author can provide historical background, look into the future, and even speculate on characters and make judgments. This point of view, writers tend to feel today, is more the method of nineteenth-century fiction, and not for today. It seems like too heavy an authorial footprint. Not handled well—and it is difficult to handle well—the characters seem to be pawns of an all-knowing author.

Today’s omniscience tends to take the form of multiple points of view, sometimes alternating, sometimes in sections. An author is behind it all, but the author is effaced, not making an appearance. BUT there are notable examples of well-handled authorial omniscience–read Nobel-prize winning Jose Saramago’s Blindness as a good example.

For more help, here’s an article I wrote on the omniscient point of view for The Writer : https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/omniscient-pov/

The limited omniscient form is typical of much of today’s fiction. You stick to your protagonist’s mind. You see others from the outside. Even so, you do have to be careful that you don’t get out of this point of view from time to time, and bring in things the character can’t see or observe—unless you want to stand outside this character, and therein lies the omniscience, however limited it is.

But anyway, note the difference between: “George’s smiles were very welcoming” and “George felt like his smiles were very welcoming”—see the difference? In the case of the first, we’re seeing George from the outside; in the case of the second, from the inside. It’s safer to stay within your protagonist’s perspective as much as possible and not describe them from the outside. Doing so comes off like a point-of-view shift. Yet it’s true that in some stories, the narrator will describe what the character is wearing, tell us what his hopes and dreams are, mention things he doesn’t know right now but will later—and perhaps, in rather quirky stories, the narrator will even say something like “Our hero…” This can work, and has, if you create an interesting narrative voice. But it’s certainly a risk.

The dramatic or objective point of view is one you’ll probably use from time to time, but not throughout your whole novel. Hemingway’s “Hills like White Elephants” is handled with this point of view. Mostly, with maybe one exception, all we know is what the characters say and do, as in a play. Using this point of view from time to time in a longer work can certainly create interest. You can intensify a scene sometimes with this point of view. An interesting back and forth can be accomplished, especially if the dialogue is clipped.

I’ve saved the second-person point of view for the last. I would advise you not to use this point of view for an entire work. In his short novel Bright Lights, Big City , Jay McInerney famously uses this point of view, and with some force, but it’s hard to pull off. In lesser hands, it can get old. You also cause the reader to become the character. Does the reader want to become this character? One problem with this point of view is it may seem overly arty, an attempt at sophistication. I think it’s best to choose either first or third.

Here’s an article I wrote on use of second person for The Writer magazine. Check it out if you’re interested. https://www.writermag.com/2016/11/02/second-person-pov/

Writing Fiction: Protagonist and Plot and Structure

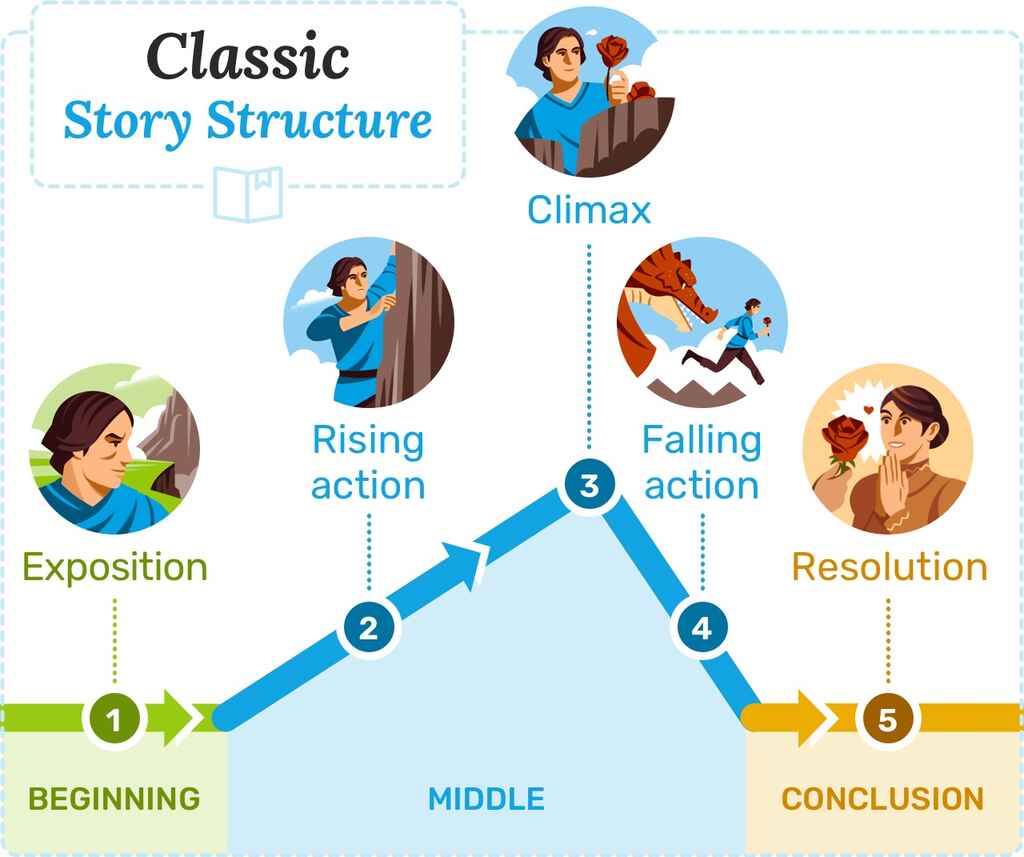

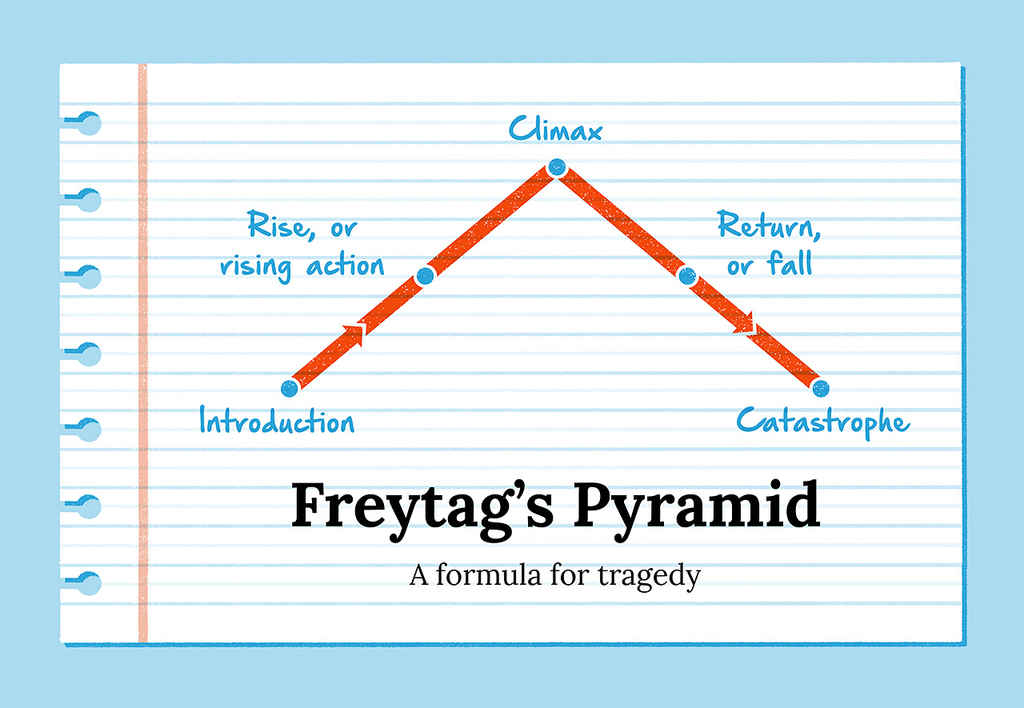

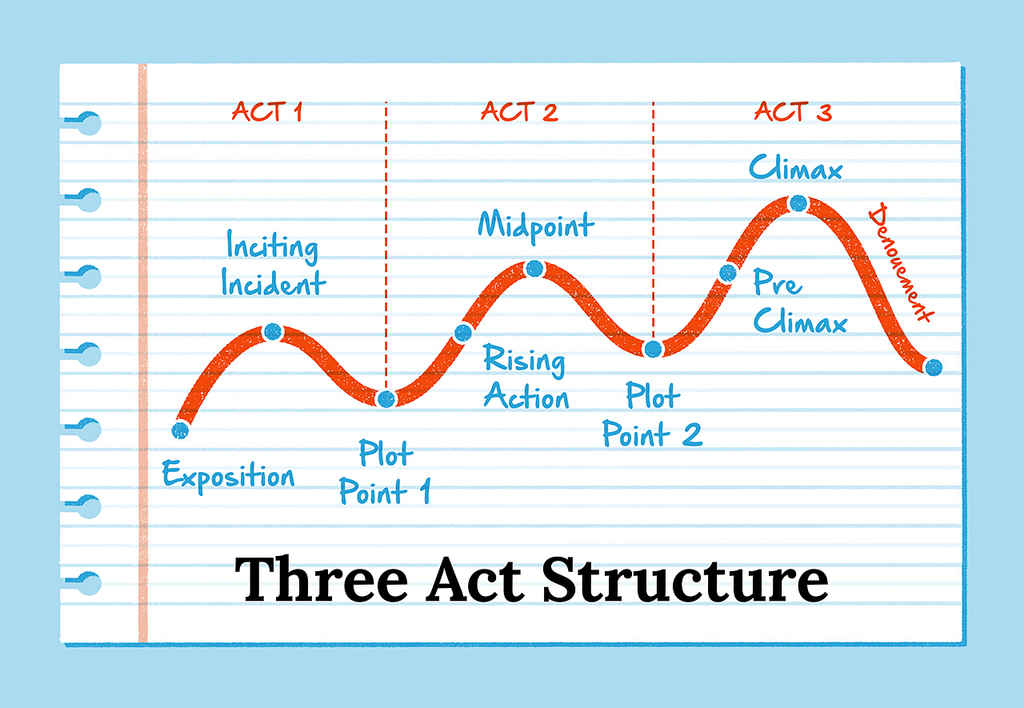

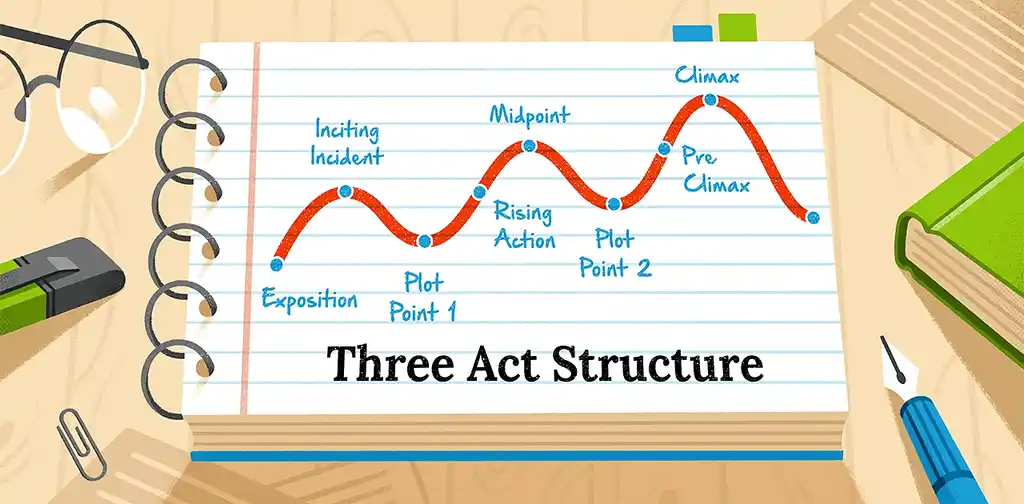

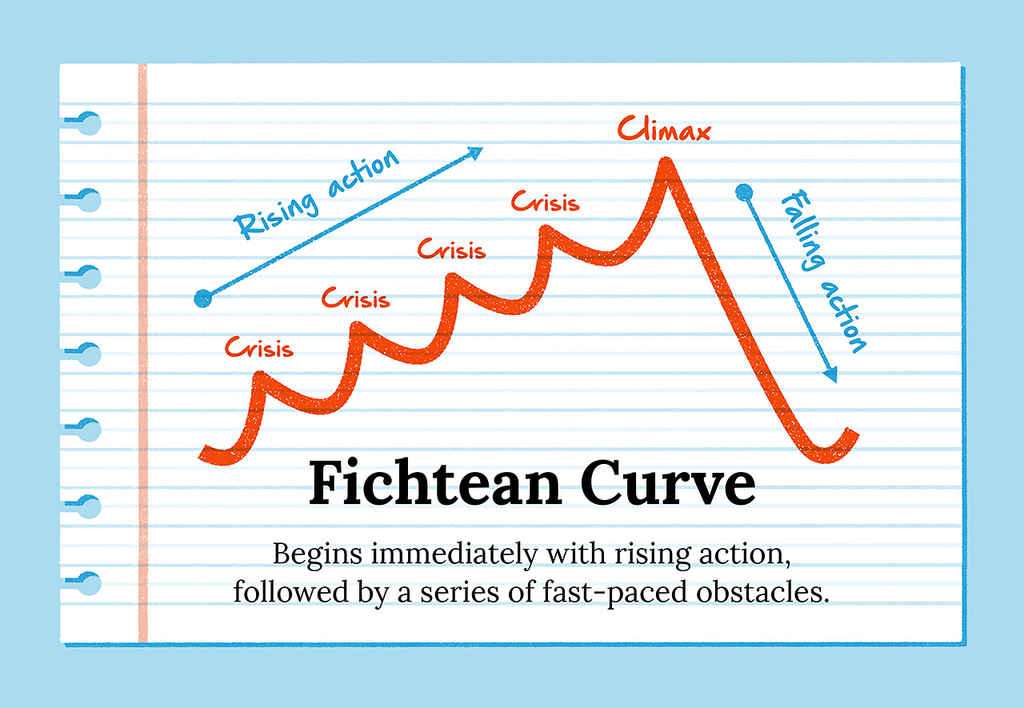

We come now to plot, keeping in mind character. You might consider the traditional five-stage structure : exposition, rising action, crisis and climax, falling action, and resolution. Not every plot works this way, but it’s a tried-and-true structure. Certainly a number of pieces of literature you read will begin in media re s—that is, in the middle of things. Instead of beginning with standard exposition, or explanation of the condition of the protagonist’s life at the story’s starting point, the author will begin with a scene. But even so, as in Jerzy Kosiński’s famous novella Being There , which begins with a scene, we’ll still pick up the present state of the character’s life before we see something that complicates it or changes the existing equilibrium. This so-called complication can be something apparently good—like winning the lottery—or something decidedly bad—like losing a huge amount of money at the gaming tables. One thing is true in both cases: whatever has happened will cause the character to change. And so now you have to fill in the events that bring this about.

How do you do that? One way is to write a chapter outline to prevent false starts. But some writers don’t like plotting in this fashion, but want to discover as they write. If you do plot your novel in advance, do realize that as you write, you will discover a lot of things about your character that you didn’t have in mind when you first set pen to paper. Or fingers to keyboard. And so, while it’s a good idea to do some planning, do keep your options open.

Let’s think some more about plot. To have a workable plot, you need a sequence of actions or events that give the story an overall movement. This includes two elements which we’ll take up later: foreshadowing and echoing (things that prepare us for something in the future and things that remind us of what has already happened). These two elements knit a story together.

Think carefully about character motivations. Some things may happen to your character; some things your character may decide to do, however wisely or unwisely. In the revision stage, if not earlier, ask yourself: What motivates my character to act in one way or another? And ask yourself: What is the overall logic of this story? What caused my character to change? What were the various forces, whether inner or outer, that caused this change? Can I describe my character’s overall arc, from A to Z? Try to do that. Write a short paragraph. Then try to write down your summary in one sentence, called a log line in film script writing, but also a useful technique in fiction writing as well. If you write by the discovery method, you probably won’t want to do this in the midst of the drafting, but at least in the revision stage, you should consider doing so.

With a novel you may have a subplot or two. Assuming you will, you’ll need to decide how the plot and the subplot relate. Are they related enough to make one story? If you think the subplot is crucial for the telling of your tale, try to say why—in a paragraph, then in a sentence.

Here’s an article I wrote on structure for The Writer : https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/revision-grammar/find-novels-structure/

Writing Fiction: Setting

Let’s move on to setting . Your novel has to take place somewhere. Where is it? Is it someplace that is particularly striking and calls for a lot of solid description? If it’s a wilderness area where your character is lost, give your reader a strong sense for the place. If it’s a factory job, and much of the story takes place at the worksite, again readers will want to feel they’re there with your character, putting in the hours. If it’s an apartment and the apartment itself isn’t related to the problems your character is having, then there’s no need to provide that much detail. Exception: If your protagonist concentrates on certain things in the apartment and begins to associate certain things about the apartment with their misery, now there’s reason to get concrete. Take a look, when you have a chance, at the short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” It’s not an apartment—it’s a house—but clearly the setting itself becomes important when it becomes important to the character. She reads the wallpaper as a statement about her own condition.

Here’s the URL for ”The Yellow Wall-Paper”: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/theliteratureofprescription/exhibitionAssets/digitalDocs/The-Yellow-Wall-Paper.pdf

Sometimes setting is pretty important; sometimes it’s much less important. When it doesn’t serve a purpose to describe it, don’t, other than to give the reader a sense for where the story takes place. If you provide very many details, even in a longer work like a novel, the reader will think that these details have some significance in terms of character, plot, or theme—or all three. And if they don’t, why are they there? If setting details are important, be selective. Provide a dominant impression. More on description below.

If you’re interested, here’s a blog on setting I wrote for Writers.com: https://writers.com/what-is-the-setting-of-a-story

Writing Fiction: Theme and Idea

Most literary works have a theme or idea. It’s possible to decide on this theme before you write, as you plan out your novel. But be careful here. If the theme seems imposed on the work, the novel will lose a lot of force. It will seem—and it may well be—engineered by the author much like a nonfiction piece, and lose the felt experience of the characters.

Theme must emerge from the work naturally, or at least appear to do so. Once you have a draft, you can certainly build ideas that are apparent in the work, and you can even do this while you’re generating your first draft. But watch out for overdoing it. Let the characters (what they do, what they say) and the plot (the whole storyline with its logical connections) contribute on their own to the theme. Also you can depend on metaphors, similes, and analogies to point to the theme—as long as these are not heavy-handed. Avoid authorial intrusion, authorial impositions of any kind. If you do end up creating a simile, metaphor, or analogy through rational thinking, make sure it sounds natural. That’s not easy, of course.

Writing Fiction: Handling Scenes

Keep a few things in mind about writing scenes. Not every event deserves a whole scene, maybe only a half-scene, a short interaction between characters. Scenes need to do two things: reveal character and advance plot. If a scene seems to stall out and lack interest, in the revision mode you might try using narrative summary instead (see below).

Good fiction is strongly dramatic, calling for scenes, many of them scenes with dialogue and action. Scenes need to involve conflict of some kind. If everyone is happy, that’s probably going to be a dull scene. Some scenes will be narrative, without dialogue. You need some interesting action to make these work.

Let’s consider scenes with dialogue.

The best dialogue is speech that sounds natural, and yet isn’t. Everything about fiction is an artifice, including speech. But try to make it sound real. The best way to do this is to “hear” the voices in your head and transcribe them. Take dictation. If you can do this, whole conversations will seem very real, believable. If you force what each character has to say, and plan it out too much, it will certainly sound planned out, and not real at all. Not that in the revision mode you can’t doctor up the speech here and there, but still, make sure it comes off as natural sounding.

Some things to think about when writing dialogue: people usually speak in fragments, interrupt each other, engage in pauses, follow up a question with a comment that takes the conversation off course (non sequiturs). Note these aspects of dialogue in the fiction you read.

Also, note how writers intersperse action with dialogue, setting details, and character thoughts. As far as the latter goes, though, if you’ll recall, I spoke of the dramatic point of view, which doesn’t get into a character’s mind but depends instead on what characters do and say, as in a play. You may try this point of view out in some scenes to make them really move.

One technique is to use indirect dialogue, or summary of what a character said, not in the character’s own words. For instance: Bill made it clear that he wasn’t going to the city after all. If anybody thought that, they were wrong .

Now and then you’ll come upon dialogue that doesn’t use the standard double quotes, but perhaps a single quote (this is British), or dashes, or no punctuation at all. The latter two methods create some distance from the speech. If you want to give your work a surreal quality, this certainly adds to it. It also makes it seem more interior.

One way to kill good dialogue is to make characters too obviously expository devices—that is, functioning to provide background or explanations of certain important story facts. Certainly characters can serve as expository devices, but don’t be too heavy-handed about this. Don’t force it like the following:

“We always used to go to the beach, you recall? You recall how first we would have breakfast, then take a long walk on the beach, and then we would change into our swimsuits, and spend an hour in the water. And you recall how we usually followed that with a picnic lunch, maybe an hour later.”

This sounds like the character is saying all this to fill the reader in on backstory. You’d need a motive for the utterance of all of these details—maybe sharing a memory?

But the above sounds stilted, doesn’t it?

One final word about dialogue. Watch out for dialogue tags that tell but don’t show . Here’s an example:

“Do you think that’s the case,” said Ted, hoping to hear some good news. “Not necessarily,” responded Laura, in a barky voice. “I just wish life wasn’t so difficult,” replied Ted.

If you’re going to use a tag at all—and many times you don’t need to—use “said.” Dialogue tags like the above examples can really kill the dialogue.

Writing Fiction: Writing Solid Prose

Narrative summary : As I’ve stated above, not everything will be a scene. You’ll need to write narrative summary now and then. Narrative summary telescopes time, covering a day, a week, a month, a year, or even longer. Often it will be followed up by a scene, whether a narrative scene or one with dialogue. Narrative summary can also relate how things generally went over a given period. You can write strong narrative summary if you make it specific and concrete—and dramatic. Also, if we hear the voice of the writer, it can be interesting—if the voice is compelling enough.

Exposition : It’s the first stage of the 5-stage plot structure, where things are set up prior to some sort of complication, but more generally, it’s a prose form which tells or informs. You use exposition when you get inside your character, dealing with his or her thoughts and emotions, memories, plans, dreams. This can be difficult to do well because it can come off too much like authorial “telling” instead of “showing,” and readers want to feel like they’re experiencing the world of the protagonist, not being told about this world. Still, it’s important to get inside characters, and exposition is often the right tool, along with narrative summary, if the character is remembering a sequence of events from the past.

Description : Description is a word picture, providing specific and concrete details to allow the reader to see, not just be told. Concreteness is putting the reader in the world of the five senses, what we call imagery . Some writers provide a lot of details, some only a few—just enough that the reader can imagine the rest. Consider choosing details that create a dominant impression—whether it’s a character or a place. Similes, metaphors, and analogies help readers see people and places and can make thoughts and ideas (the reflections of your character or characters) more interesting. Not that you should always make your reader see. To do so might cause an overload of images.

Check out these two articles: https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/the-definitive-guide-to-show-dont-tell/ https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/figurative-language-in-fiction/

Writing Fiction: Research

Some novels require research. Obviously historical novels do, but others do, too, like Sci Fi novels. Almost any novel can call for a little research. Here’s a short article I wrote for The Writer magazine on handling research materials. It’s in no way an in-depth commentary on research–but it will serve as an introduction. https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/research-in-fiction/

For a blog on novel writing, check this link at Writers.com: https://writers.com/novel-writing-tips

For more articles I’ve published in The Writer , go here: https://www.writermag.com/author/jack-smith/

How to Start Writing Fiction: Take a Writing Class!

To write a story or even write a book, fiction writers need these tools first and foremost. Although there’s no comprehensive guide on how to write fiction for beginners, working with these elements of fiction will help your story bloom.

All six elements synergize to make a work of fiction, and like most works of art, the sum of these elements is greater than the individual parts. Still, you might find that you struggle with one of these elements, like maybe you’re great at writing characters but not very good with exploring setting. If this is the case, then use your strengths: use characters to explore the setting, or use style to explore themes, etc.

Getting the first draft written is the hardest part, but it deserves to be written. Once you’ve got a working draft of a story or novel and you need an extra set of eyes, the Writers.com community is here to give feedback: take a look at our upcoming courses on fiction writing, and check out our talented writing community .

Good luck, and happy writing!

I have had a story in my mind for over 15 years. I just haven’t had an idea how to start , putting it down on print just seems too confusing. After reading this article I’m even more confused but also more determined to give it a try. It has given me answers to some of my questions. Thank you !

You’ve got this, Earl!

Just reading this as I have decided to attempt a fiction work. I am terrible at writing outside of research papers and such. I have about 50 single spaced pages “written” and an entire outline. These tips are great because where I struggle it seems is drawing the reader in. My private proof reader tells me it is to much like an explanation and not enough of a story, but working on it.

first class

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How to Write Fiction

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Fiction Writing Fundamentals

First steps , key elements, how to write compelling stories, drafting and revising, how to share and publish your work, resources for teaching fiction writing, additional writing resources .

From the earliest cave paintings to Harry Potter, human beings have been fascinated by storytelling. Writing fiction, the act of "fashioning or imitating" according to the Oxford English Dictionary, has played a part in that imaginative exercise for millennia. Through the written word, authors express ideas and emotions and share compelling narratives. This guide is a collection of dozens of links about the process of writing fiction that we have researched, categorized, and annotated. You'll learn how to define "fiction" and what its forms are, discover resources to help you write and publish stories, and find ideas for teaching creative writing.

The umbrella category of "fiction" covers short stories and 500,000-word Victorian novels, heart-pounding thrillers and epic poetry. Before you dive into the process of creating your own fiction, it’s important to know what the term means and what its main forms are. Below, you'll find resources to ground you in an understanding of fiction's history and many genres.

What is Fiction?

"Fiction" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's entry on fiction offers a broad definition of the term, along with sections on fiction's formats, genre fiction, literary fiction, and links for further exploration.

"Memoir vs. Fiction" ( The Pen & The Pad )

This article from a writing website offers a short breakdown of the differences between memoir and fiction, including use of facts, protagonists and point of view, use of detail, and purpose.

"Fiction v. Nonfiction" (Criticalreading.com)

Dan Kurland's critical reading website offers a quick list of the differences between fiction and nonfiction, along with a list of the major categories of fiction writing.

"The Benefits of Fiction vs. Nonfiction" (Reddit)

This archived subreddit is filled with comments on the benefits of fiction and nonfiction, as well as the uses of these two different types of writing.

"What is Fiction?" (PBS Digital Studios via YouTube)

This eleven-minute video from the Idea Channel digs into the philosophical underpinnings of the term "fiction," outlining the differences between fiction and reality.

"Fiction Forms" (Wikipedia)

This Wikipedia category page describes the different forms of fiction, from epistolary novels to blog fiction, with links to more information on each form.

The Forms of Fiction (Amazon)

This (lengthy) classic book by John Gardner and Lennis Dunlap breaks down the short story form into a series of different categories, explaining the differences between each one.

"Different Types of Fiction" ( The Writer's Cookbook Blog)

This blog post offers a fairly comprehensive list of the different types of fiction, organized in a way that “won’t make your head explode,” according to the author.

"The Meaning of Genre in Literature" ( Owlcation )

This article will help you understand the difference between form and genre, using the construction of a building as a useful analogy in comparing the two.

"Defining Genre" ( The Editor's Blog )

This blog post provides an overview of what genre in fiction is, along with a link to a second post that touches on all the major genres in fiction.

"List of Writing Genres" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia’s list of genres is divided into those pertaining to fiction and nonfiction, with an explanation of how “genre” fiction differs from “literary” fiction.

"What’s Your Genre?: A High-Level Overview for Writers" (JaneFriedman.com)

This post from a publishing industry professional discusses the role genre plays in the book industry and how it affects categories, sales, and marketing.

"Sub-Genre Descriptions" ( Writer's Digest )

This post lists all of the various sub-genres within the major genre classifications, with a quick description of what they typically entail.

As the resources above make clear, works of fiction vary in length, form, and genre. Your piece might be 500 words (flash fiction) or 500,000 words (like some novels). You might choose to write a mystery, romance, or fantasy piece. Even within genres, authors write for different ages and audiences. You also need to decide on a point of view—should your story be told from the first person perspective, or from the vantage point of an omniscient narrator? The resources below will introduce you to the many choices writers of fiction must make.

How to Choose a Form

"Should You Write a Novel or Short Story" ( Writer's Digest )

This article lists five things you should keep in mind as you decide whether your story should be a full-length novel or a short story.

"How to Choose the Right Medium for Your Story" (Literary Hub)

This piece, authored by a film and television writer who also dabbles in other forms, discusses the different skill sets required for writing in each literary form, and the storytelling opportunities afforded by each one.

“Is it Better to Be a Short Story Writer or a Novelist?” (British Council)

This article by Northern Irish author Paul McVeigh weighs the pros and cons of writing short stories and novels, and describes the challenges of each.

"8 Reasons You Should be Writing Short Stories" (TCK Publishing)

This list, geared towards self-published or independently published writers, discusses the benefits of writing short stories—both for your craft, and your bottom line.

How to Pick a Genre

"What Type of Book Should You Write?" (Quizony)

Use this not-so-serious quiz about your favorite characters, opening lines, and more to help get you brainstorming on the type of book you should write.

"How to Choose a Genre When Writing" ( Writer's Digest )

In this post on the Writer’s Digest site, bestselling writer Catherine Ryan Hyde discusses how to choose a genre when writing fiction, and how that genre often chooses you.

How to Identify Your Audience

"How to Find Your Ideal Reader" ( The Book Designer )

This article by author Cathy Yardley discusses how to identify the audience for your fiction book by figuring out exactly what type of book you are writing.

"How Authors Can Find Their Ideal Reading Audience" (JaneFriedman.com)

This post by writing coach and author Angela Ackerman offers tips for identifying the audience you’re writing for and connecting with your readers.

"Finding a Target Audience for Your Book in 3 Steps" ( Reedsy )

This post outlines the process of finding the “right” readers for your book, understanding their perspective, and figuring out how to connect to them via platforms like Goodreads.

"Do You Know Who Your Audience is?" ( Writer Unboxed )

This post from writer Dan Blank suggests that you choose your ideal audience before you start crafting your story. Blank emphasizes that most stories are not universal.

How to Choose a Perspective

"First, Second, and Third Person" (QuickandDirtyTips.com)

Grammar Girl reads this article by Geoff Pope, which is a no-nonsense guide to the different perspectives that writing can take, paired with a discussion of when each is commonly used.

"First-Person POV vs. Third-Person POV" (Youtube)

This short video from bestselling author K.M. Weiland focuses on deciding whether a first-person or third-person perspective is better for your book.

"1st vs 3rd Person—Which is Best?" ( Novel Writing Help )

This short post debunks some common misconceptions about when you “have to” use first or third person, with links to longer in-depth pieces on each perspective.

"What Point of View Should You Use in Your Novel?" ( Writer's Digest )

This article from the Writer's Digest site focuses on different writing perspectives and contains bulleted lists of the advantages and disadvantages of using each point of view.

Fiction writing can be broken down into a few key elements, including setting (where the story takes place), characters (who the story is about), dialogue (what characters say), plot (what happens in the story), and theme (what the story is ultimately about). Masterful fiction writers are able to incorporate each element seamlessly into a narrative whole. The resources in this section will help you get to know these terms.

"Setting" (Wikipedia)

This Wikipedia article offers a quick description of setting and its role, along with a comprehensive list of links to more about specific subtypes of setting.

"Setting: The Place and Time of Story" ( The Editor's Blog )

This blog post will help you learn what exactly setting accomplishes in fiction, including grounding characters. It discusses the different elements that make up setting.

"Discover the Basic Elements of Setting in a Story" ( Writer's Digest )

This post from Writer's Digest offers a quick look at 12 of the important elements of setting. These include population, historical importance, and climate.

"Story Setting Ideas" ( Now Novel )

This blog post offers a few examples of effective settings, from J.K. Rowling’s Hogwarts to the Victorian England of Charles Dickens's Hard Times .

"Dialogue" (Wikipedia)

This Wikipedia article provides a comprehensive overview of dialogue, including how it has been used historically in a variety of literary forms.

"What is Dialogue in Literature?" ( Writing Explained )

If you're looking for a short post offering both a definition and examples of dialogue, this is a good place to start. The post explains the difference between internal and external dialogue.

"Dialogue" ( The Editor's Blog )

Check out this post on what dialogue is and what it accomplishes. The article includes some tips at the end about best practices for writing dialogue.

"Dialogue Definition" (LitCharts)

The LitCharts guide to dialogue offers a definition of the term, and is followed by examples of successful dialogue in fiction and a brief discussion of dialogue’s function.

"Character (Arts)" (Wikipedia)

Head to Wikipedia for a succinct definition of fictional characters and an explanation of types (such as flat, round, dynamic, static, etc.).

"Types of Character in Fiction" (Lexiconic.net)

This list of common categories of characters in fiction includes protagonists and antagonists, and is accompanied by a quick list of ways that character can be revealed in a text.

"Seven Common Character Types" ( Fiction Factor)

Here, you'll find a list of seven types of characters commonly found in fiction, along with an explanation of the roles these kinds of characters typically play in the story.

"Characters in Fiction" (Little Bit of Lit via Youtube)

This eight-minute video defines "character," discusses types of characterization (such as indirect), and lists a few different character types.

"Plot (Narrative)" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's entry on "plot" offers a definition of the term and a description of some common literary frameworks that writers can use.

"What is a Plot?" ( Writing Explained )

In this blog post, you'll find a concise explanation of the typical elements of plot, along with a discussion of its function, a few popular examples, and more.

"Plot" ( Literary Devices )

This article from a site devoted to explicating literary terms discusses the five main components of plot and offers a few examples of plot in literature.

"Plot Structure" (SlideShare)

SlideShare offers this 10-part slideshow on the different elements of plot (including exposition, rising action, and climax) and discusses some common conflicts in fiction.

"Theme (narrative)" (Wikipedia)

Wikipedia's entry on theme introduces you to the term through a brief definition and a discussion of two separate techniques used in writing to express themes.

"Elements of Fiction: Theme" ( Find Your Creative Muse )

This blog post defines themes, explains how they are revealed, and gives some popular examples of how they are used in literature. It also offers some links to resources for writing fiction.

"A Handy Guide to the Most Common Themes in Literature" ( The Writers Academy Blog)

This post from the Penguin Random House writing blog defines theme and lists some common themes in literature. Learn about themes such as "crime doesn't pay" and "coming of age."

"Grasping Themes in Literature" (Scholastic)

Check out this round-up of common themes in literature, which is accompanied by lesson ideas and suggestions for other media that are helpful in teaching theme.

Now that you're familiar with the fundamentals of plot, character, setting, theme, and dialogue, you're ready to fashion these elements into a compelling narrative. The resources below offer questions and suggestions for worldbuilding, character development, crafting dialogue, and more. As you refine your writing skills, remember that even stories that seem effortlessly created involved hundreds of small choices on the author's part, and went through a number of drafts.

How to Choose a Setting

"Fantasy Worldbuilding Questions" (Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America)

Here, you'll find a comprehensive list of questions you can ask yourself about the setting you’re developing. These questions will help you flesh out your world's culture, rules, and norms.

Subreddit on Worldbuilding

You can discuss anything and everything about worldbuilding on this forum, from choosing character names to coming up with different governments for your world.

"7 Deadly Sins of Worldbuilding" ( Gizmodo )

This post lists common mistakes you can make in worldbuilding—choices that will knock readers out of the reading experience and make your characters seem pointless.

"World Building" (YouTube)

This video, one in a series of lectures by Brandon Sanderson about writing novels, focuses on worldbuilding and how to do so successfully.

How to Write Engaging Dialogue

"Writing Dialogue: 10 Tips to Help You" (YouTube)

In this 17-minute video, graphic novelist and children's book author and illustrator Mark Crilley draws images as he explains his top 10 tips for writing engaging dialogue.

"Keys to Realistic Dialogue" ( Writer's Digest )

This piece is the first in a two-part post by author Eleanore D. Trupkiewicz on common problems in writing dialogue and how to fix them.

"Writing Dialogue: Tips and Exercises" ( Reedsy )

This post offers a series of eight tips on how to write dialogue, including Elmore Leonard's suggestion never to use verbs other than "said" to "carry dialogue." The post also includes four dialogue writing exercises for authors.

"Tips for Writing Dialogue" (Center for Fiction)

This post discusses the three forms of dialogue (summary, indirect speech, and direct quotation) followed by succinct advice on how best to write dialogue between characters.

How to Develop Characters

"8 Ways to Write Better Characters" ( Writer's Digest )

This in-depth article by writer Elizabeth Sims includes eight ways to help conceptualize your characters and delve deeper into their psyches.

"How to Build a Character" (Jtellison.com)

Get tips from New York Times bestselling author J.T. Ellison on how to build a compelling character, and hear insights on her own process for developing characters.

"How to Create a Character Profile" ( Writer's Write )

This article includes an extensive character checklist to help you flesh out your characters' background, hobbies, relationships, and more.

"Character Chart for Fiction Writers" (EpiGuide.com)

This printable, fill-in-the-blank chart from EpiGuide.com helps writers brainstorm about all aspects of their characters in order to get to know them.

How to Craft Plot

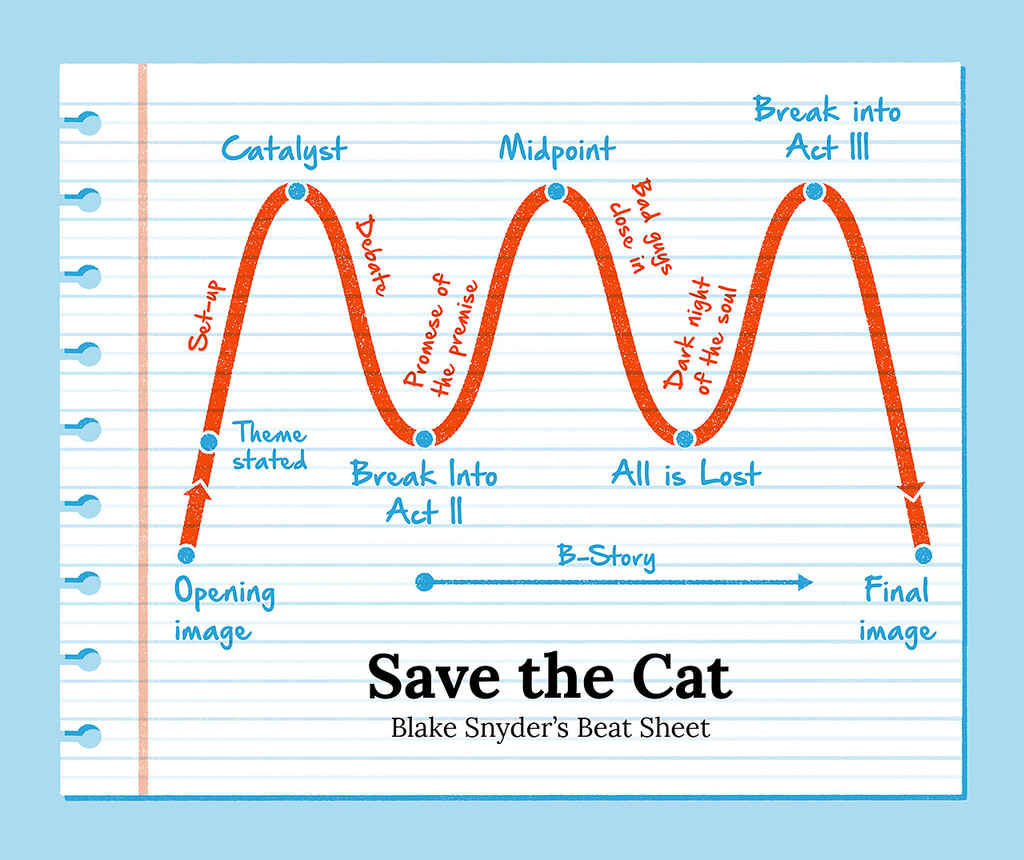

"'Save the Cat' Beat Sheet" (Tim Stout)

Based on the book Save the Cat! (originally for screenwriters), this post offers a list of the “beats” that each narrative must contain in order to tell its story most effectively.

The Moral Premise Blog: Story Structure Craft

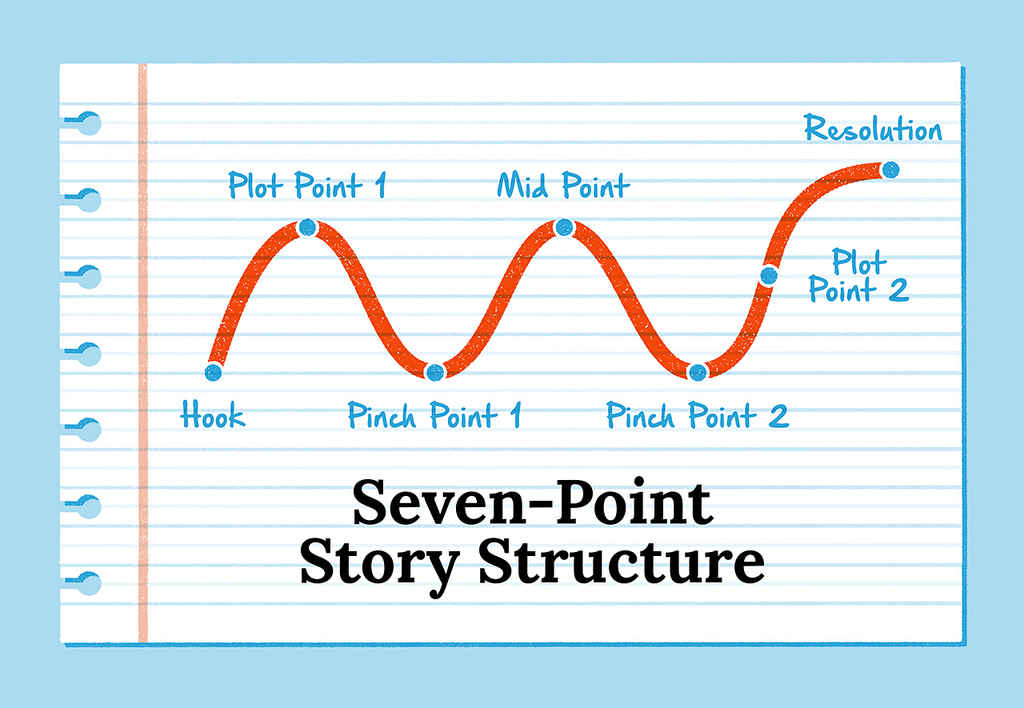

This blog by producer Stan Williams, author of The Moral Premise , contains diagrams of different ways to structure a book, including his well-known “story diamond.”

"Novel in 30 Days Worksheet Index" ( Writer's Digest )

This Writer's Digest post is a round-up of nine different worksheets you can download and use to help outline and plan your novel.

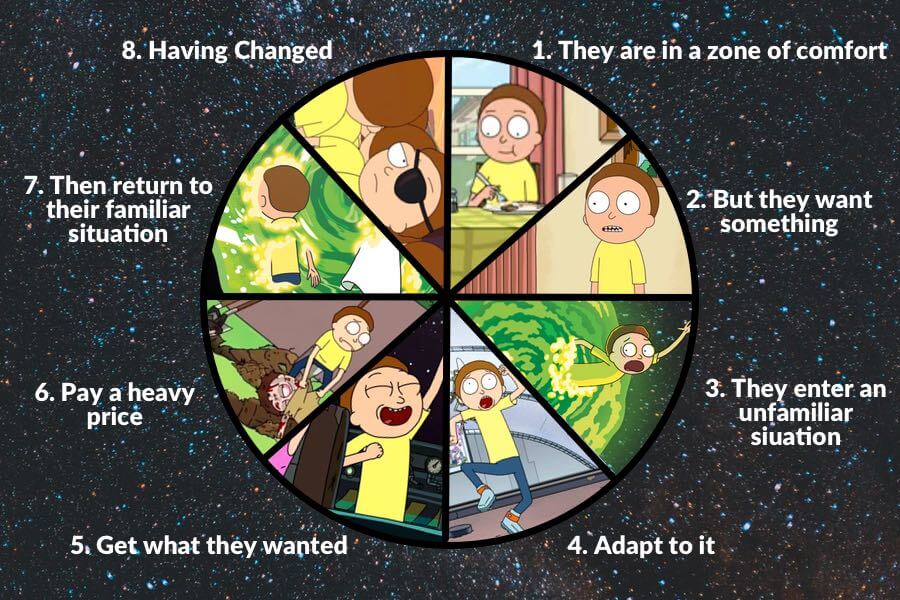

"How to Plot Your Novel Using Dan Harmon's Story Circle" (YouTube)

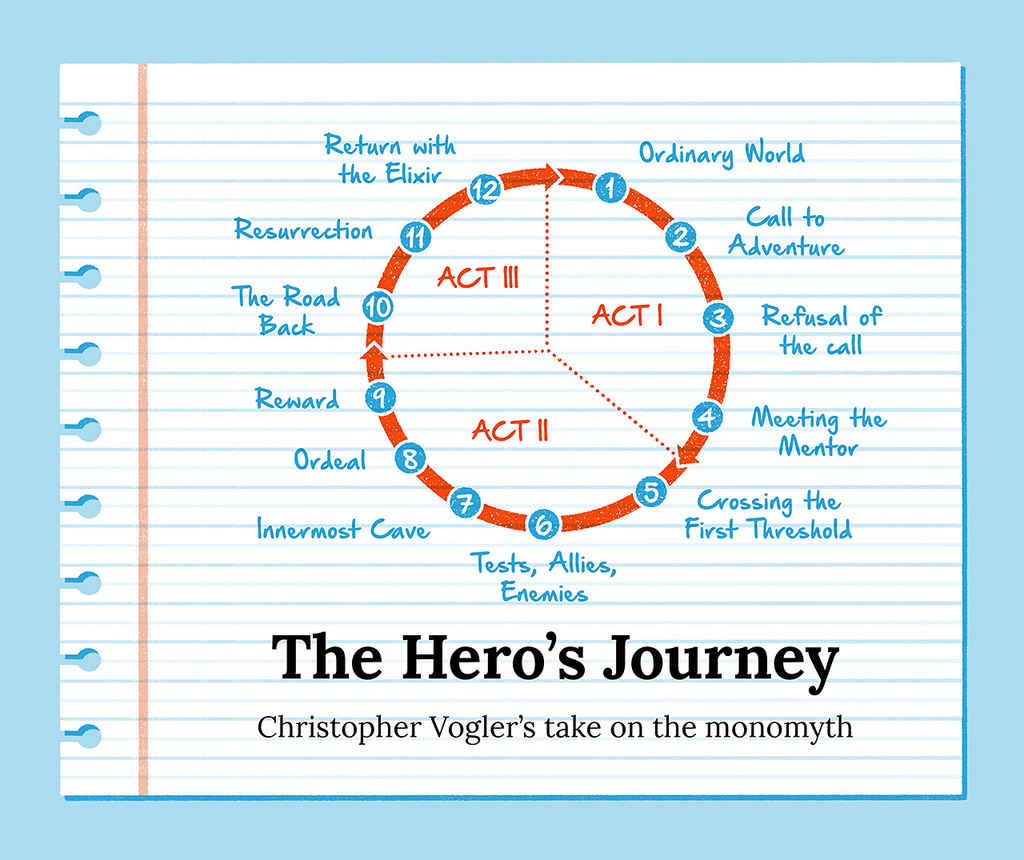

This 15-minute video describes how to use another popular plotting tool, Dan Harmon’s story circle (based off of Joseph Campbell’s book The Hero with a Thousand Faces ), to plot your novel.

How to Choose and Use Themes

"How to Choose Good Themes for Stories" ( Now Novel )

Read these five tips on choosing the best themes for your story from the Now Novel site. Suggestions include matching themes with characters' personalities and goals and examining how great authors have treated similar ideas.

"When Choosing Themes, Write What You Don’t Know" ( The Write Practice )

This brief article will help you narrow down which theme you should choose to write about based on what issues you are interested in.

"Exploring Theme" ( Writer's Digest )

In this excerpt from the book Story Engineering, hosted on the Writer's Digest site, Larry Brooks defines theme and explains why it is so important in writing.

"How to Choose and Build a Powerful Theme for Your Story" ( Well-Storied )

This page offers both a podcast episode and an article on how to pick the best theme for your story, and makes suggestions for how to thread that theme through a narrative.

Writing a short story or novel can be a labor-intensive process. Even once a full draft is complete, a writer is rarely ready to send it out into the world. Instead, successful writers spend time revising and editing their work with feedback from trusted readers. Below, you'll find resources to help you write a first draft, revise that draft, overcome writer's block, and prepare a final draft.

How to Write a First Draft

"10 Rules for Writing Fiction" ( The Guardian )

This collection of 10 top tips for writing fiction from famous writers (including Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman, and Jonathan Franzen) is based on Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules of Writing.

The Writer Files (Rainmaker.fm)

This podcast features interviews with a variety of writers on their wring process, tricks, and tips, and how to tap into both creativity and productivity.

Writing Excuses Podcast

This podcast is hosted by four authors and has over ten seasons. It features 15-minute episodes that cover all parts of the writing process.

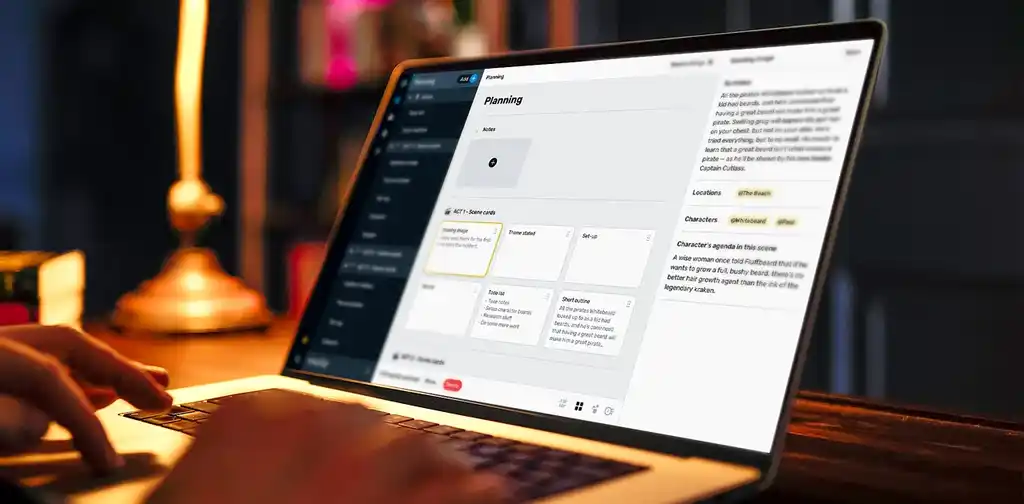

This program gives authors an alternative to a traditional Word program, and has helpful features like movable scenes, notecards, and tagging.

How to Overcome Writer’s Block

"How to Beat Writer’s Block" ( The New Yorker )

This article from The New Yorker offers an introduction to the term “writer’s block” and ways that writers have combatted it successfully.

"Strategies for Overcoming Writer’s Block" (Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

This page from a college writing center looks at some ineffective and effective ways to combat writer’s block, along with a brief description of why it occurs.

"Other Strategies for Getting Over Writer’s Block" (Purdue OWL)

This article offers quick strategies for getting over writer’s block when drafting your novel, along with suggestions for how you can get started on a piece.

"How Professional Writers Beat Writer’s Block" ( The Writer)

Writermag.com rounded up these five interviews with leading professional authors on how they’ve learned to get past writer’s block.

How to Edit Your First Draft

"4 Levels of Editing Explained" ( The Book Designer )

This article touches on the different types of editing that a book requires. It is aimed towards writes looking to hire independent editors for developmental editing, copy editing, etc., but is helpful for anyone looking to improve a manuscript.

"Revision Checklist" (Nathan Bransford)

This checklist from popular blogger, writer, and former agent Nathan Bransford notes important things to keep in mind when revising your novel.

"Revision Techniques" ( The Narrative Breakdown )

On this podcast episode, Cheryl Klein (a senior editor at Arthur A. Levin Books who worked on Harry Potter ), details some of her revision techniques.

"A Month of Revision" ( Necessary Fiction )

This post focuses on the necessary steps in the revision process and a realistic timeline, and includes links to numerous other blog posts on revision at the bottom.

How to Prepare a Final Draft

"Editing Checklist" (ReadWriteThink)

Use this printable PDF as a checklist for both writers and peer editors when tracking any errors in grammar, punctuation, spelling, and capitalization.

"How to Edit" ( Live Write Breathe )

This comprehensive editing guide for fiction writers contains instructions on carrying out all the major phases of revising a manuscript.

"How Do You Know When Your Book is Finished?" ( Electric Lit )

Here, the monthly advice column The Blunt Instrument offers suggestions for determining when works of fiction and works of poetry are “complete.”

"How Do You Know When You’re Ready to Submit?" ( Writer's Digest )

This article tackles the question of how to know when it's time to stop tweaking your work, and time send the manuscript into the world.

"How to Format a Fiction Manuscript for Submission" (YouTube)

This detailed 15-minute video explains how to format a manuscript using industry standards before sending it off to publishers and agents.

A number of options exist to get a writer’s work into the hands of readers. Writers can choose to share their work immediately with online communities, meet in person with critique partners, enter writing contests, hire an agent, or independently submit their work for publication online or in print. The resources below will help you evaluate your options and make an informed decision.

Fiction Writing Communities

Wattpad is an online fiction-writing community where you can post and share your stories immediately, tagging them with plot elements or settings so other readers can find them and comment.

Like Wattpad, Figment is an online fiction-writing community where you can post your work, get feedback from other readers, and comment on others' work.

Absolute Write Water Cooler

On this online bulletin board, writers of all genres and experiences discuss writing, publishing, and everything in between. The site facilitates discussion by offering categories with forums, threads, and individual posts.

This forum, run by Amazon, is a place for writers to discuss their work and ask advice about promotion and self-publishing. You'll need to register in order to comment.

Fiction Writing Contests

"Writing Contests, Grants, and Awards" (Poets & Writers)

This searchable database of contests and more, from the nation's largest nonprofit organization serving creative writers, allows you to narrow by entry fee, genre, and deadline.

"31 Free Writing Contests" ( The Write Life )

This writing website offers a list of competitions in all different genres that have no entry fee for submission, but come with the possibility of a cash prize.

"Art and Writing Competitions" (Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth)

This list of art and writing competitions is geared toward younger writers, and contains links to each competition’s website. This link will direct you to the "creative writing" tab, but there are also options for journalism, essay, and visual arts competitions.

"Your Perfect Cover Letter" ( The Review Review )

This article discusses both how to craft and format a cover letter for a literary submission. It does so by walking you through a hypothetical example by "Emerging Writer."

How to Get a Short Story Published Online

Writers can use this resource to find short story markets, track their submissions, and find upcoming deadlines for short story markets.

"Where to Submit Short Stories" ( The Write Life )

Check out The Write Life 's round-up of 23 places accepting short stories, including prestigious and paying markets like The New Yorker .

"Literary Magazines" (Poets & Writers)

Here, you'll find a searchable database of literary magazines that accept short stories, with information on the magazines’ genres and reading periods.

"Get Inside the Top 30 Short Story Markets" ( Writer's Digest )

This top 30 list of the best outlets for short fiction is broken down by categories such as “Best Bets for Beginners” and “You’re in the Money.”

How to Get a Book Published in Print

Querytracker

On this website, you can search for agents by genre and see whether they are open to queries. You'll also find comments from writers on their response times.

Query Shark

Literary agent Janet Reid critiques queries on her blog, offering feedback on subsequent drafts until she gets to the point where she would have requested more material.

The Essential Guide to Getting Your Book Published (Amazon)

This book on how to navigate publishing your book touches not only on traditional approaches, but also on new avenues like self-publishing, crowdfunding, and more.

Publishing 101: A First-Time Author’s Guide to Getting Published (Amazon)

This book by industry veteran Jane Friedman explains how editors evaluate your work, and how best to approach agents and editors in order to land a book deal.

Resources abound for designing creative writing classes at all levels. Classroom activities allow students to practice their skills on-demand, while homework exercises give students time to construct their narratives on their own time. Below, you'll find a curated list of lesson planning ideas from publishers, TED-Ed, Teachers Pay Teachers, and more.

Classroom Activities

"Writing Fiction" ( Teaching Ideas )

This education website offers lesson plans and ideas for teachers on all different topics within the fiction writing framework (and on a wide range of other subjects, as well).

"Resource Topics: Teaching Writing" (National Writing Project)

This page provides links to a number of resources for teaching different aspects of creative writing, including a conversation about the future of creative writing pedagogy.

"Creative Writing Lesson Plans" ( The English Teacher )

On this webpage, you'll find a list of short lesson ideas, each with related exercises, that teachers can use to shape their curriculum.

"Creative Writing Resources" ( TeacherVision )

TeacherVision hosts a list of printable fiction writing resources, broken down by grade level, that can be used to shape classroom activities.

"Creative Writing Resources and Lesson Plans" (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This popular education website (designed by teachers, for teachers) has a section devoted to creative writing resources. You'll find lesson plans and activities that are searchable by price, resource type, and grade level.

Homework Exercises

"Short Fiction: A Write It Activity" (Scholastic)

This activity includes interactive tutorials, exercises, message boards, links, and more—including an opportunity for students to submit their work at the end.

"365 Creative Writing Prompts" ( ThinkWritten )

This comprehensive list of short prompts (hosted by a website with tabs on publishing, author marketing, and writing prompts) will get students’ ideas flowing for a short exercise or a story.

What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers (Amazon)

This handbook for writers by Anne Bernays and Pamela Painter contains more than 75 exercises for writers of all levels of experience.

"Creative Writing Prompts That You Can Do In 10 Minutes" (TED-Ed blog)

Use this list of short creative writing prompts to generate ideas for writing. The text is excerpted from the book 642 Tiny Things to Write About .

A number of other resources exist for those looking to develop their writing skills. Consider participating in writing retreats, writing workshops devoted to publishing, and online creative classes, or reading books and listening to podcasts on the subject. The resources gathered here can help you grow as a writer, and will teach you more about the process of sharing your work.

In-person Creative Writing Classes, Workshops, and Retreats

Gotham Writers

This well-known organization provides both in-person classes in NYC and online writing classes led by writers on topics such as “How to Get Published” and “Novel Writing.”

Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI)

This organization offers conferences and networking opportunities for writers of children’s and young adult literature. Other genre-specific writers’ organizations, such as the American Crime Writers League and Horror Writers Association, offer similar workshops.

"Conferences and Residencies Database" (Poets & Writers)

Check out this database for a comprehensive list of conferences and residencies currently available. It is searchable by event type, state, price, and title.

"Guide to Writing Programs" (Association of Writers & Writing Programs)

This database of writing programs, including undergraduate programs and MFAs, is searchable by genre, state, and type of degree.

Online Creative Writing Classes and Workshops

National Novel Writing Month

This website is all about November’s NaNoWriMo, in which writers challenge themselves to write 50,000 words in one month. It contains forums, inspiration, and more.

Courses on Creative Writing (Coursera)

This site offers online classes where you can watch lectures, complete exercises, and even receive feedback for your work (depending on whether you choose a free or paid option).

"The Best Online Writing Courses" (TCK Publishing)

TCK Publishing offers this round-up of different creative writing courses. The webpage describes what you learn, who the instructor is, and what the cost is (many of them are free).

Brandon Sanderson Lectures (YouTube)

This YouTube "playlist" is made up of American fiction writer Brandon Sanderson's lectures for a course at BYU, which covers all aspects of working through a novel.

Top-rated Books on Creative Writing

You Are a Writer (So Start Acting Like One) (Amazon)

Writer Jeff Goins covers a variety of topics on the writing life, including self-doubt, how to improve your writing, and how to get published.

Stephen King’s On Writing (Amazon)

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is part memoir of Stephen King's life as a writer, and part “toolkit” for writers trying to improve their craft.

The Elements of Style (Amazon)

William Strunk Jr. and E.B. White authored this no-nonsense guide to writing clearly and well. It covers the fundamentals of syntax. This book is now in its fourth edition.

Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life (Amazon)

This national bestseller from author Anne Lamot is comprised of a series of essays on the process of writing (from beginning to write to technical details) and her life as a writer.

Fiction Writing Websites

"How to Write Fiction" (WikiHow)

This fully illustrated guide to writing fiction includes sections on generating ideas, creating mindmaps for possible plotlines, and common pitfalls to avoid.

Writer’s Digest

The popular writing magazine Writer's Digest hosts this website, which focuses exclusively on helping writers connect to the best writing resources, learn the craft of writing, and get published.

Writing Forward

This creative writing blog offers tips and tricks for writing, along with resources for online writing exercises, resources, and much more.

Literary Rambles

This website is devoted exclusively to providing information about children’s book authors, agents, and publishers. It includes interviews with many key industry players on what they’re looking for in a manuscript.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1924 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,556 quotes across 1924 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

How to Write Fiction: 9 Steps From a Bestselling Novelist

By jerry jenkins.

Guest Post by Jerry Jenkins

That you’ve landed here tells me you have a story—a message you want to share with the world. You just need to know how to begin.

Writing fiction isn’t about rules or techniques or someone else’s ideas. It’s about your story well told.

Writing a novel can be overwhelming.

I’ve written nearly 200 books (two-thirds of them novels) and have enjoyed the kind of success most writers only dream of. But the work never gets easier.

I’ve found no shortcuts, but following certain steps help me create books in which my readers can get delightfully lost.

Is that the kind of novel you want to write?

Table of Contents

9 Steps to Writing Captivating Fiction

- Come up with a great story idea.

- Create realistic and memorable characters.

- Choose a story structure.

- Home in on the setting.

- Write your rough draft.

- Grab your reader from the get-go.

- Trigger the theater of your reader’s mind.

- Maintain your reader’s attention with cliffhangers.

- Write a resounding, satisfying ending.

Want to sell more books? Click here to get your free copy of 8 Simple Secrets to Big Book Sales on Amazon

Step #1 — come up with a great story idea..

Do you struggle to generate ideas?

Maybe you have a message to share but no story idea to help you convey it.

Ideas are everywhere. You have to learn to recognize the germ of an idea that can become a story .

My first novel was about a judge who tries a man for a murder that the judge committed.

That’s all I had—along with its obvious ramifications.

I knew guilt. I recalled being caught in a lie. So I could imagine the ultimate dilemma—desperate to hide the truth while being assigned to oversee its coming to light.

That imagining became Margo , the novel that launched my fiction career.

I know a story idea has legs when it stays with me and grows.

I find myself sharing the idea with my family, embellishing the story more every time I tell it. If it loses steam, it’s because I’ve lost interest in it and know readers would too.

But if it holds my interest, I nourish and develop it until it becomes a manuscript and eventually a book .

Always carry something on which you can record ideas, electronic or old school. (I like the famous Moleskine notebooks.)

Jot or dictate ideas that strike at any moment for these elements:

- Anything that might expand your story

And if you’re still having trouble conjuring an idea, see Step #2 below for an exercise writers everywhere have told me works to stimulate their thinking almost every time.

Step #2 — Create realistic and memorable characters.

Ironically, Fiction (though you know its definition) must be believable , even if it’s set in a land far, far away or centuries before or since now.

That means characters must feel real and relatable so readers will buy your premise.

If you don’t know where to begin, consider creating characters who are composites of people you know.

You might use one person’s gender, another’s looks, another’s personality, another’s voice …

Now here’s that exercise I promised above:

Imagine you’re at a rural intersection in the middle of nowhere. Maybe there are cornfields all around.

A Greyhound bus appears on the horizon and rumbles to a stop. One passenger disembarks.

Now ask yourself who this character is:

- Male or female?

- Young or old?

- Rich or poor?

- Laden with luggage or empty-handed?

- Are they waiting to be picked up or heading somewhere on foot?

- Where are they going?

- Are they escaping someone or something?

- Are they running to someone or something?

By now you should have an idea of a main character and, bottom line, start imagining a story.

You need a villain too, but be fair to him (or her; I use he inclusively to mean both genders and avoid the awkward repetition of he/she; I know the majority of writers—and readers—are women).

So what do I mean by “be fair to your villain”?

Simply this: don’t allow him to be one-dimensional (evil just because he’s the bad guy).

In real life, villainous people rarely recognize themselves as evil. They think everyone else is wrong!

Give him real, credible motivations for doing what he does. That doesn’t make him right, but it can make him real and believable.

One thing that contributed to the success of my Left Behind series was that I determined early on to have credible, skeptical characters.

It’s so easy to build straw men and shoot down their arguments and logic like shooting fish in a barrel.

Make them credible! Give them opinions and arguments that are hard to counter.

Give your skeptical reader someone he can identify with and force him to acknowledge you were fair to his side.

Our goal as writers should be that the stories and characters we create will live in the hearts of readers for years.

How you develop your characters will make or break your story .

Outliners have an advantage here, and we Pantsers (who write by the seat of our pants as a process of discovery) do well to learn from them.

Outliners map out the backstory of each character, getting to know them before starting to write.

Some even conduct imaginary interviews, simply asking the characters about themselves. Readers will never see most of what comes from this information, but it does inform the writing.

Whether you get to know your characters in advance or allow them to reveal themselves as you write, make them human, vulnerable, and flawed—eventually heroic and inspiring.

Just don’t make them perfect. Nobody relates to perfect .

Consider some of literature’s most memorable characters—Jane Eyre, Scarlett O’Hara, Atticus Finch, Ebenezer Scrooge, Huckleberry Finn, Katniss Everdeen, Harry Potter.

Here are heroes of both genders, vastly different personalities, widely varying ages, and even from different centuries. But look what they have in common:

- They’re larger than life but also universally human

- They see courage not as lack of fear but rather the ability to act in the face of fear

- They learn from failure and rise to great moral victories

Compelling characters like these make the difference between a memorable story and a forgettable one.

Keys to Developing a Memorable Character

1. Introduce him by name as soon as possible.

Your lead character should be the first person on stage, and the reader should be able to connect with him.

His name should reflect his heritage and maybe even hint at his personality. In The Green Mile , Stephen King named a weak, cowardly character Percy Wetmore. Naturally, we treat heroes with more respect.

2. Give readers a look at him.

You want readers to clearly picture your character in their minds, but don’t make the mistake of forcing them to see him exactly as you do.

While rough height, hair color, and maybe eye color should be established—as well as whether he is athletic or not—does it really matter whether your reader visualizes your hero as Brad Pitt or Leonardo DiCaprio or your heroine as Gwyneth Paltrow or Charlize Theron?

Now, similar to what I’ll advise later about rendering settings, it’s better to layer in your character’s looks through dialogue and action rather than using description as a separate element.

Whether you’re an Outliner or a Pantser, the more you know about your character, the better you will tell your story.

- Nationality and ethnicity?

- Scars? Piercings? Tattoos? Imperfections? Deformities?

- Tone of voice? Accent?

- Mannerisms, unique gestures, tics, anything else that would set him apart?

Avoid the mistake of trying to include in your manuscript everything you know about your character.

But on the other hand, the more you know, and the more you know, the more plot ideas that might emerge.

The better acquainted you are with your character, the better your readers will come to know and care about him.

3. Give him a backstory.

Backstory is everything that has happened in your character’s life before page one of chapter one. What has made him the person he is today?

Things you should know, whether or not you include them in your story:

- When, where, and to whom he was born

- Brothers and sisters and where he fits in the family

- His educational background

- Political leanings

- Skills and talents

- Spiritual life

- Best friend

- Romantic relationship, if any

- Personality type

- Anger triggers

- Joys, pleasures

- And anything else relevant to your story

4. Make him real.

Even superheroes have flaws and weaknesses. For Superman, it’s Kryptonite. For Indiana Jones, snakes.

Perfect characters are impossible to identify with. But don’t make his flaws deal breakers—they should be forgivable, understandable, identifiable, but not irredeemable.

For instance, don’t make him a wimp, a coward, or a doofus (like a cop who either misplaces his weapon or forgets to load it).

Create a character with whom your reader can relate, someone vulnerable who subtly exhibits strength of character and potential heroism.

Does your character show respect to a waitress and recognize her by name?

Would he treat a cashier the same way he treats his broker?

If he’s running late but witnesses an emergency, does he stop and help?

Some call these pet-the-dog moments , where an otherwise bigger-than-life personality does something out of character—something that might be considered beneath him.

And you can add real texture to your narrative by even giving your villain a pet-the-dog moment.

5. But also give him heroic potential. In the end, he must rise to the occasion and score a great moral victory.

So he needs to be both extraordinary and relatable. He can’t remain a victim for long.

He can and should face obstacles and adversity, but he should never act the wimp or appear cowardly.

Give him qualities—or at least potential—that captivates the reader and compels him to keep reading. For example:

- an underdog with surprising resolve that allows him to rise to the occasion

- a character who reveals the hint of a hidden strength or ability and later uses it to win the day

Make him heroic and you make him unforgettable.

6. Emphasize his inner life as well.

The outward trouble, quest, challenge—whatever drives the story—is one thing. But every bit as important is your character’s internal conflict .

What keeps him awake at night?

- What’s his blind spot?

- What are his secrets?

- What embarrasses him?

- What is he passionate about?

Mix and match details from people you know—and yourself—to create both the inner and outer person.

When he faces a life or death situation, you’ll know how he should respond.

7. Draw upon your own experience.

The fun of writing fiction is getting to embody the characters we create.

I can be a young girl, an old man, a boy, a father, a grandmother, of another race, a villain, of a different political or spiritual persuasion, etc. The possibilities are endless.

Become your character .

Imagine yourself in every situation he finds himself, facing every dilemma, answering every question—how would you react if you were your character?

If your character finds himself in danger, even if you’ve never experienced something so terrible, you can imagine it.

Think back to the last time you felt in danger, multiply that times a thousand, and become your character.

- Imagine being at home alone and hearing footsteps across the floor above.

- Have you ever had your child go missing?