The Sheridan Libraries

- Public Health

- Sheridan Libraries

- Literature Reviews + Annotating

- How to Access Full Text

- Background Information

- Books, E-books, Dissertations

- Articles, News, Who Cited This, More

- Google Scholar and Google Books

- PUBMED and EMBASE

- Statistics -- United States

- Statistics -- Worldwide

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- Copyright This link opens in a new window

- Evaluating Information This link opens in a new window

- RefWorks Guide and Help This link opens in a new window

- Epidemic Proportions

- Environment and Your Health, AS 280.335, Spring 2024

- Honors in Public Health, AS280.495, Fall 23-Spr 2024

- Intro to Public Health, AS280.101, Spring 2024

- Research Methods in Public Health, AS280.240, Spring 2024

- Social+Behavioral Determinants of Health, AS280.355, Spring 2024

- Feedback (for class use only)

Literature Reviews

- Organizing/Synthesizing

- Peer Review

- Ulrich's -- One More Way To Find Peer-reviewed Papers

"Literature review," "systematic literature review," "integrative literature review" -- these are terms used in different disciplines for basically the same thing -- a rigorous examination of the scholarly literature about a topic (at different levels of rigor, and with some different emphases).

1. Our library's guide to Writing a Literature Review

2. Other helpful sites

- Writing Center at UNC (Chapel Hill) -- A very good guide about lit reviews and how to write them

- Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources (LSU, June 2011 but good; PDF) -- Planning, writing, and tips for revising your paper

3. Welch Library's list of the types of expert reviews

Doing a good job of organizing your information makes writing about it a lot easier.

You can organize your sources using a citation manager, such as refworks , or use a matrix (if you only have a few references):.

- Use Google Sheets, Word, Excel, or whatever you prefer to create a table

- The column headings should include the citation information, and the main points that you want to track, as shown

Synthesizing your information is not just summarizing it. Here are processes and examples about how to combine your sources into a good piece of writing:

- Purdue OWL's Synthesizing Sources

- Synthesizing Sources (California State University, Northridge)

Annotated Bibliography

An "annotation" is a note or comment. An "annotated bibliography" is a "list of citations to books, articles, and [other items]. Each citation is followed by a brief...descriptive and evaluative paragraph, [whose purpose is] to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited."*

- Sage Research Methods (database) --> Empirical Research and Writing (ebook) -- Chapter 3: Doing Pre-research

- Purdue's OWL (Online Writing Lab) includes definitions and samples of annotations

- Cornell's guide * to writing annotated bibliographies

* Thank you to Olin Library Reference, Research & Learning Services, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY, USA https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

What does "peer-reviewed" mean?

- If an article has been peer-reviewed before being published, it means that the article has been read by other people in the same field of study ("peers").

- The author's reviewers have commented on the article, not only noting typos and possible errors, but also giving a judgment about whether or not the article should be published by the journal to which it was submitted.

How do I find "peer-reviewed" materials?

- Most of the the research articles in scholarly journals are peer-reviewed.

- Many databases allow you to check a box that says "peer-reviewed," or to see which results in your list of results are from peer-reviewed sources. Some of the databases that provide this are Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts.

What kinds of materials are *not* peer-reviewed?

- open web pages

- most newspapers, newsletters, and news items in journals

- letters to the editor

- press releases

- columns and blogs

- book reviews

- anything in a popular magazine (e.g., Time, Newsweek, Glamour, Men's Health)

If a piece of information wasn't peer-reviewed, does that mean that I can't trust it at all?

No; sometimes you can. For example, the preprints submitted to well-known sites such as arXiv (mainly covering physics) and CiteSeerX (mainly covering computer science) are probably trustworthy, as are the databases and web pages produced by entities such as the National Library of Medicine, the Smithsonian Institution, and the American Cancer Society.

Is this paper peer-reviewed? Ulrichsweb will tell you.

1) On the library home page , choose "Articles and Databases" --> "Databases" --> Ulrichsweb

2) Put in the title of the JOURNAL (not the article), in quotation marks so all the words are next to each other

3) Mouse over the black icon, and you'll see that it means "refereed" (which means peer-reviewed, because it's been looked at by referees or reviewers). This journal is not peer-reviewed, because none of the formats have a black icon next to it:

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: RefWorks Guide and Help >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 10:04 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/public-health

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Subject Research

- Public Health

- Literature reviews

Public Health: Literature reviews

Created by health science librarians.

- Sciwheel & Citation managers

- Data & software

- Grey literature

- Popular search strategies

Section Objective

What is a literature review, clearly stated research question, search terms, searching worksheets, boolean and / or.

- Systematic reviews

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Sciences and Engineering

- Epidemiology

- Health Behavior

- Health Policy and Management

- Maternal and Child Health

- Public Health Leadership

The content in the Literature Review section defines the literature review purpose and process, explains using the PICO format to ask a clear research question, and demonstrates how to evaluate and modify search results to improve the accuracy of the retrieval.

A literature review seeks to identify, analyze and summarize the published research literature about a specific topic. Literature reviews are assigned as course projects; included as the introductory part of master's and PhD theses; and are conducted before undertaking any new scientific research project.

The purpose of a literature review is to establish what is currently known about a specific topic and to evaluate the strength of the evidence upon which that knowledge is based. A review of a clinical topic may identify implications for clinical practice. Literature reviews also identify areas of a topic that need further research.

A systematic review is a literature review that follows a rigorous process to find all of the research conducted on a topic and then critically appraises the research methods of the highest quality reports. These reviews track and report their search and appraisal methods in addition to providing a summary of the knowledge established by the appraised research.

The UNC Writing Center provides a nice summary of what to consider when writing a literature review for a class assignment. The online book, Doing a literature review in health and social care : a practical guide (2010), is a good resource for more information on this topic.

Obviously, the quality of the search process will determine the quality of all literature reviews. Anyone undertaking a literature review on a new topic would benefit from meeting with a librarian to discuss search strategies. A consultaiton with a librarian is strongly recommended for anyone undertaking a systematic review.

Use the email form on our Ask a Librarian page to arrange a meeting with a librarian.

The first step to a successful literature review search is to state your research question as clearly as possible.

It is important to:

- be as specific as possible

- include all aspects of your question

Clinical and social science questions often have these aspects (PICO):

- People/population/problem (What are the characteristics of the population? What is the condition or disease?)

- Intervention (What do you want to do with this patient? i.e. treat, diagnose)

- Comparisons [not always included] (What is the alternative to this intervention? i.e. placebo, different drug, surgery)

- Outcomes (What are the relevant outcomes? i.e. morbidity, death, complications)

If the PICO model does not fit your question, try to use other ways to help be sure to articulate all parts of your question. Perhaps asking yourself Who, What, Why, How will help.

Example Question: Is acupuncture as effective of a therapy as triptans in the treament of adult migraine?

Note that this question fits the PICO model.

- Population: Adults with migraines

- Intervention: Acupuncture

- Comparison: Triptans/tryptamines

- Outcome: Fewer Headache days, Fewer migraines

A literature review search is an iterative process. Your goal is to find all of the articles that are pertinent to your subject. Successful searching requires you to think about the complexity of language. You need to match the words you use in your search to the words used by article authors and database indexers. A thorough PubMed search must identify the author words likely to be in the title and abstract or the indexer's selected MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) Terms.

Start by doing a preliminary search using the words from the key parts of your research question.

Step #1: Initial Search

Enter the key concepts from your research question combined with the Boolean operator AND. PubMed does automatically combine your terms with AND. However, it can be easier to modify your search if you start by including the Boolean operators.

migraine AND acupuncture AND tryptamines

The search retrieves a number of relevant article records, but probably not everything on the topic.

Step #2: Evaluate Results

Use the Display Settings drop down in the upper left hand corner of the results page to change to Abstract display.

Review the results and move articles that are directly related to your topic to the Clipboard .

Go to the Clipboard to examine the language in the articles that are directly related to your topic.

- look for words in the titles and abstracts of these pertinent articles that differ from the words you used

- look for relevant MeSH terms in the list linked at the bottom of each article

The following two articles were selected from the search results and placed on the Clipboard.

Here are word differences to consider:

- Initial search used acupuncture. MeSH Terms use Acupuncture therapy.

- Initial search used migraine. Related word from MeSH Terms is Migraine without Aura and Migraine Disorders.

- Initial search used tryptamines. Article title uses sumatriptan. Related word from MeSH is Sumatriptan or Tryptamines.

With this knowledge you can reformulate your search to expand your retrieval, adding synonyms for all concepts except for manual and plaque.

#3 Revise Search

Use the Boolean OR operator to group synonyms together and use parentheses around the OR groups so they will be searched properly. See the image below to review the difference between Boolean OR / Boolean AND.

Here is what the new search looks like:

(migraine OR migraine disorders) AND (acupuncture OR acupuncture therapy) AND (tryptamines OR sumatriptan)

- Search Worksheet Example: Acupuncture vs. Triptans for Migraine

- Search Worksheet

- << Previous: Popular search strategies

- Next: Systematic reviews >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 1:21 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.unc.edu/publichealth

Public Health

- COVID-19 Resources This link opens in a new window

- Define Your Topic

- Searching Strategies

- Types of Resources

- Other Types of Scholarly Articles

- Finding Op-Eds

Literature Review

- Qualitative Research

- Web Resources

- LibX This link opens in a new window

- Reload Button

- Virtual Private Network (VPN)

- Google Scholar Settings

- Articles & Databases

- Data & Statistics This link opens in a new window

- Data Visualization Tools This link opens in a new window

- Films and videos

- Infographics This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Reviews This link opens in a new window

- Stay Current with Research

- Tenure and Promotion Resources This link opens in a new window

- Theses & Dissertations This link opens in a new window

- Bills, Laws and Public Policies

- Biostatistics

- Complementary & Alternative Medicine

- Consumer Health

- Epidemiology

- Evidence-Based Medicine

- Environmental Health Law

- Fact-checking resources

- Family Science

- Government Information

- Health Behavior Theory

- History of Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Kinesiology

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

- Statistics This link opens in a new window

- Tests and Measurement Instruments

- Citation Styles

- Citation Managers

- Academic Integrity

- Books on different types of professional writing

- Health Sciences Libraries in DC area

- Library Award for Undergraduate Research

- For faculty

- Class materials

- What is a literature review?

- Tutorial - text and video

- Tips for better writing

What exactly is a Literature Review?

A literature review describes, summarizes and analyzes previously published literature in a field. What you want to do is demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of what the "conversation" about this topic is, identify gaps in the literature, present research pertinent to your ideas and how your research fits in with, changes, elaborates on, etc., the present conversation.

BOOKS - Literature Review and how to write it

BOOKS - Research Methods

Research Methods at a Glance

This information on basic business research methods is in part adapted from the book Field Guide to Nonprofit Program Design, Marketing and Evaluation by Carter McNamara (Call number: HD62.6 .M36).

Research Methods in General

Research Methods in Public Health

- The Literature Review: A Research Journey This guide from the Harvard School of Education is an introduction to the basics of conducting a literature review.

- How to cite effectively and improve readability of your paper?

Improve your writing

The Academic Phrasebank is a general resource for academic writers. It aims to provide you with examples of some of the phraseological ‘nuts and bolts’ of writing organized according to the main sections of a research paper or dissertation:

- Introducing work - e.g Evidence suggests that X is among the most important factors for …

- Referring to sources - e.g. A number of authors have considered the effects of … (Smith, 2003; Jones, 2004).

- Describing methods - e.g. Different methods have been proposed to classify … (Johnson, 2021; Petersen, 2019; Appel, 2017).

- Reporting results - e.g. Interestingly, the X was observed to …

- Discussing findings - e.g. A strong relationship between X and Y has been reported in the literature.

- Writing conclusions - e.g. One of the more significant findings to emerge from this study is that …

Additional examples from Academic Phrasebank are below:

Before explaining these theories, it is necessary to …

In a similar case in America, Smith (2021) identified …

This is exemplified in the work undertaken by Smith (2021) ...

Recent cases reported by Smith et al . (2021) also support the hypothesis that …

This section has reviewed the three key aspects of …

In summary, it has been shown from this review that …

- << Previous: Finding Op-Eds

- Next: Qualitative Research >>

- Last Updated: May 14, 2024 12:14 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/PublicHealth

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Searching the public health & medical literature more effectively: literature review help.

- Getting Started

- Articles: Searching PubMed This link opens in a new window

- More Sources: Databases, Systematic Reviews, Grey Literature

- Organize Citations & Search Strategies

- Literature Review Help

- Need More Help?

Writing Guides, Manuals, etc.

Literature Review Tips Handouts

Write about something you are passionate about!

- About Literature Reviews (pdf)

- Literature Review Workflow (pdf)

- Search Tips/Search Operators

- Quick Article Evaluation Worksheet (docx)

- Tips for the Literature Review Workflow

- Sample Outline for a Literature Review (docx)

Ten simple rules for writing a literature review . Pautasso M. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(7):e1003149. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

Conducting the Literature Search . Chapter 4 of Chasan-Taber L. Writing Dissertation and Grant Proposals: Epidemiology, Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2014.

A step-by-step guide to writing a research paper, from idea to full manuscript . Excellent and easy to follow blog post by Dr. Raul Pacheco-Vega.

Data Extraction

Data extraction answers the question “what do the studies tell us?”

At a minimum, consider the following when extracting data from the studies you are reviewing ( source ):

- Only use the data elements relevant to your question;

- Use a table, form, or tool (such as Covidence ) for data extraction;

- Test your methods and tool for missing data elements, redundancy, consistency, clarity.

Here is a table of data elements to consider for your data extraction. (From University of York, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination).

Critical Reading

As you read articles, write notes. You may wish to create a table, answering these questions:

- What is the hypothesis?

- What is the method? Rigorous? Appropriate sample size? Results support conclusions?

- What are the key findings?

- How does this paper support/contradict other work?

- How does it support/contradict your own approach?

- How significant is this research? What is its special contribution?

- Is this research repeating existing approaches or making a new contribution?

- What are its strengths?

- What are its weaknesses/limitations?

From: Kearns, H. & Finn, J. (2017) Supervising PhD Students: A Practical Guide and Toolkit . AU: Thinkwell, p. 103.

Submitting to a Journal? First Identify Journals That Publish on Your Topic

Through Scopus

- Visit the Scopus database.

- Search for recent articles on your research topic.

- Above the results, click “Analyze search results."

- Click in the "Documents per year by source" box.

- On the left you will see the results listed by the number of articles published on your research topic per journal.

Through Web of Science

- Visit the Web of Science database.

- In the results, click "Analyze Results" on the right hand side.

- From the drop-down menu near the top left, choose "Publication Titles."

- Change the "Minimum record count (threshold)," if desired.

- Scroll down for a table of results by journal title.

- JANE (Journal/Author Name Estimator) Use JANE to help you discover and decide where to publish an article you have authored. Jane matches the abstract of your article to the articles in Medline to find the best matching journals (or authors, or articles).

- Jot (Journal Targeter) Jot uses Jane and other data to determine journals likely to publish your article (based on title, abstract, references) against the impact metric of those journals. From Yale University.

- EndNote Manuscript Matcher Using algorithms and data from the Web of Science and Journal Citation Reports, Manuscript Matcher identifies the most relevant and impactful journals to which one may wish to submit a manuscript. Access Manuscript Matcher via EndNote X9 or EndNote 20.

- DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) Journal Lookup Look up a journal title on DOAJ and find information on publication fees, aims and scope, instructions for authors, submission to publication time, copyright, and more.

Writing Help @UCB

Here is a short list of sources of writing help available to UC Berkeley students, staff, and faculty:

- Purdue OWL Excellent collection of guides on writing, including citing/attribution, citation styles, grammar and punctuation, academic writing, and much more.

- Berkeley Writing: College Writing Programs "Our philosophy includes small class size, careful attention to building your critical reading and thinking skills along with your writing, personalized attention, and a great deal of practice writing and revising." Website has a Writing Resources Database .

- Graduate Writing Center, Berkeley Graduate Division Assists graduate students in the development of academic skills necessary to successfully complete their programs and prepare for future positions. Workshops and online consultations are offered on topics such as academic writing, grant writing, dissertation writing , thesis writing , editing, and preparing articles for publication, in addition to writing groups and individual consultations.

- Nature Masterclass on Scientific Writing and Publishing For Postdocs, Visiting Scholars, and Visiting Student Researchers with active, approved appointments, and current UC Berkeley graduate students who are new to publishing or wish to refresh their skills. Part 1: Writing a Research Paper; Part 2: Publishing a Research Paper; Part 3: Writing and Publishing a Review Paper. Offered by Visiting Researcher Scholar and Postdoc Affairs (VSPA) program; complete this form to gain access.

Alternative Publishing Formats

Here is some information and tips on getting your research to a broader, or to a specialized, audience

- Creating One-Page Reports One-page reports are a great way to provide a snapshot of a project’s activities and impact to stakeholders. Summarizing key facts in a format that is easily and quickly digestible engages the busy reader and can make your project stand out. From EvaluATE .

- How to write an Op-ed (Webinar) Strategies on how to write sharp op-eds for broader consumption, one of the most important ways to ensure your analysis and research is shared in the public sphere. From the Institute for Research on Public Policy .

- 10 tips for commentary writers From UC Berkeley Media Relations’ 2017 Op-Ed writing workshop.

- Journal of Science Policy and Governance JSPG publishes policy memos, op-eds, position papers, and similar items created by students.

- Writing Persuasive Policy Briefs Presentation slides from a UCB Science Policy Group session.

- 3 Essential Steps to Share Research With Popular Audiences (Inside Higher Ed) How to broaden the reach and increase the impact of your academic writing. Popular writing isn’t a distraction from core research!

The Politics of Citation

"One of the feminist practices key to my teaching and research is a feminist practice of citation."

From The Digital Feminist Collective , this blog post emphasizes the power of citing.

"Acknowledging and establishing feminist genealogies is part of the work of producing more just forms of knowledge and intellectual practice."

Here's an exercise (docx) to help you in determining how inclusive you are when citing.

Additional Resources for Inclusive Citation Practices :

- BIPOC Scientists Citation guide (Rockefeller Univ.).

- Conducting Research through an Anti-Racism Lens (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries).

- cleanBib (Code to probabilistically assign gender and race proportions of first/last authors pairs in bibliography entries).

- Balanced Citer (Python script guesses the race and gender of the first and last authors for papers in your citation list and compares your list to expected distributions based on a model that accounts for paper characteristics).

- Read Black women's work;

- Integrate Black women into the CORE of your syllabus (in life & in the classroom);

- Acknowledge Black women's intellectual production;

- Make space for Black women to speak;

- Give Black women the space and time to breathe.

- CiteASista .

- << Previous: Organize Citations & Search Strategies

- Next: Need More Help? >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 3:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/publichealth/litsearch

Majority of Youth Are Willing to Answer Questions About Their Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity

Dean’s note: this pride month, reaffirming the dignity of lgbtqia+ populations, literature reviews ..

A literature review is systematic examination of existing research on a proposed topic (1). Public health professionals often consult literature reviews to stay up-to-date on research in their field (1–3). Researchers also frequently use literature reviews as a way to identify gaps in the research and provide a background for continuing research on a topic (1,2). This section will provide an overview of the essential elements needed to write a successful literature review.

Collecting Articles

A literature review is systematic examination of existing research on a proposed topic (1). Public health professionals often consult literature reviews to stay up-to-date on research in their field (1–3). Researchers also frequently use literature reviews as a way to identify gaps in the research and provide a background for continuing research on a topic (1,2). This section will provide an overview of the essential elements needed to write a successful literature review.

Do not hesitate to reach out to a reference librarian at the BUMC Alumni Medical Library for assistance in collecting your research.

Reviewing the Research

After selecting the articles for your review, read each article and takes notes to keep track of each paper (3). One way to effectively take notes is to create a table listing each article’s research question, methods, results, limitations, etc. Once you have finished reading the articles, critically think about why each one is important to your discussion (1,2,4). Try to group articles based on similar content, such as similar study populations, methods, or results (4). Most literature reviews do not require you to organize your articles in a certain manner; however, you should think about how you would logically tie your articles together so that you are analyzing them, not simply summarizing each article (4).

Organizing your Review

While there is no standard organization for a literature review, literature reviews generally follow this structure (1,3):

- Introduction. The introduction should identify a research question and relate it to a public health topic. The significance of the public health problem and topic should be described.

- Body. The body of a literature review should be organized so that the review flows logical from one subtopic to another subtopic. Consider breaking this section into the following sections:

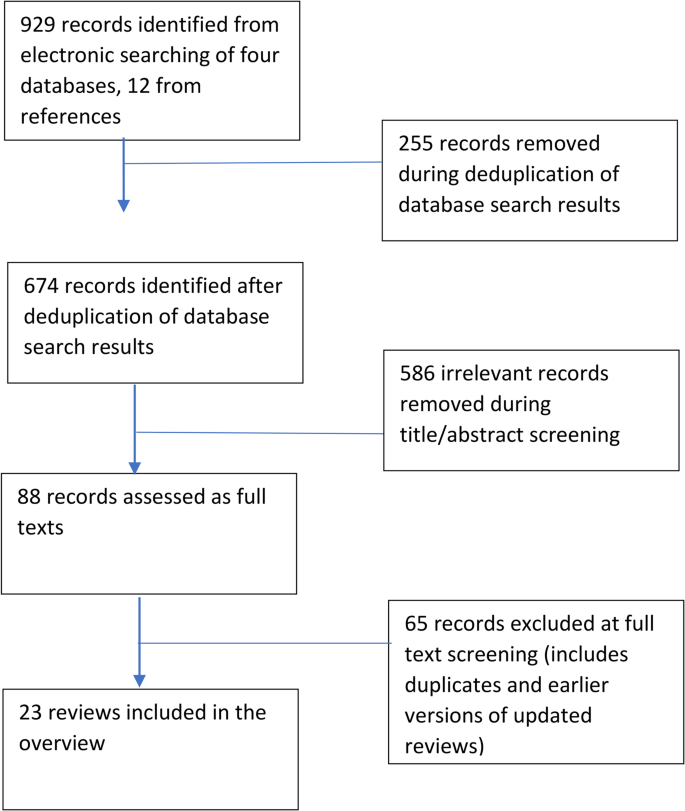

- Methods. Describe how you obtained your articles. Be sure to include the names of search engines and key words used to generate searches. Detail your inclusion and exclusion criteria (i.e. did not fit your definition of your outcome). Consider creating a flow chart to illustrate your search process.

- Results/Discussion. Explain what the literature says about your question. What did the studies find? Is their conflicting evidence? What are the limitations of the current studies? What gaps exist in the literature? What are the outstanding research questions? A table of your studies can be a great tool to summarize of the essential information.

- Conclusion. Review your findings and how they relate to your research questions. Use this space to propose needs in the research, if appropriate.

Collecting articles, reviewing your research, and organizing your review are the first steps toward writing a literature review. Reading examples of peer-reviewed literature reviews is an excellent way to brainstorm how to organize your research and tables.

Additional Resources

The following resources also provide a more in-depth discussion on writing literature reviews:

- Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review (requires BU Kerberos Login)

- Handout on Writing Literature Reviews from UNC Writing Center

- Tips for Writing a Public Health Literature Review from Tulane University

- Get the Lit: The Literature Review Video from Texas A&M University Writing Center

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Literature Reviews [Internet]. The Writing Center. [cited 2014 Jul 15]. Available from: http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/literature-reviews/

- Tips for writing a public health literature review [Internet]. Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine 1. Department of Community Health Sciences; [cited 2014 Jul 15]. Available from: http://tulane.edu/publichealth/mchltp/upload/Writing-Lit-review.pdf

- Pautasso M. Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013 Jul 18;9(7):e1003149.

- Get Lit: The Literature Review [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2014 Jul 15]. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1hG99HUaOk&feature=youtube_gdata_player

Public Health: LITERATURE REVIEWS

- WELCOME TO THE PUBLIC HEALTH RESEARCH GUIDE!

- PH COURSE BOOKS & MOVIES

- RESEARCH DATABASES

- DATA SOURCES

- PUBLIC HEALTH JOURNALS

- HEALTH EQUITY & CRIMINAL JUSTICE

- GLOBAL HEALTH

- COMMUNTY ACTION FOR HEALTH

- LITERATURE REVIEWS

SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

- EXAM RESOURCES

- HOW TO USE & ACCESS LIBRARY TOOLS & RESOURCES

This page contains resources to help you with your literature reviews.

To find more resources, search in the TUC Library Catalog using a keyword search. For example, if you need information about literature reviews, use the keywords *literature reviews* and you will be presented with many more books--both print and electronic.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES

Information about getting started with your research and the various research methods and can be found on the R esearch Methods page.

Information about systematic reviews can be found on the Systematic Reviews page.

WHAT IS A LITERATURE REVIEW? (9:38)

This short video covers all you need to know about what a literature review is and why it is important. It goes over the various steps and gives tips and insight on the process.

HOW TO WRITE A LITERATURE REVIEW: 3-MINUTE STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE (3:04)

HOW TO READ & COMPREHEND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ARTICLES (5:03)

This 5-minute video tutorial from the University of Minnesota will give you a brief overview of how to read research articles to get the most understanding of them while saving you time.

BOOKS ON LITERATURE REVEWS

CONTACT ME FOR HELP

HOW TO READ EVIDENCE-BASED MEDICINE PAPERS

- << Previous: RESEARCH METHODS

- Next: SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 11:58 AM

- URL: https://libguides.tu.edu/mph

Public Health Research Experiences

- Welcome: Use the Resources

- Choosing a Topic

- Building a Literature Review

- Search Strategies & Tutorials

- Picking Databases

- Checking What You Find

- Zotero: Using a Citation Manager

The Purpose of the Literature Review

More about Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students From NCSU Libraries, this 9 minute video tutorial (with a transcript) explores the purpose, expectations, and structure of a literature review.

- What Is a Literature Review Describes how literature reviews help both the researcher and the reader. (a section in the book Scientific Inquiry in Social Work )

- Lesson 5.1: Types of Evidence and Literature Reviews (part of chapter 5 in the book The DNP Project Workbook: A Step-by-Step Process for Success )

- Sources Included in a Literature Review (part of Chapter 6 in the book Understanding Nursing Research: Building an Evidence-Based Practice )

- The sections Exploring and Refining Your Question through Accessing Journal Literature (part of Chapter 6 in the book How to Write Your Nursing Dissertation )

- Evaluating the Literature (part of chapter 7 in the book Introduction to Nursing Research: Incorporating Evidence-Based Practice )

- Critically Appraising and Assessing the Quality of the Literature (part of chapter 5 in the book Literature Reviews and Synthesis: A Guide for Nurses and Other Healthcare Professionals )

- << Previous: Choosing a Topic

- Next: Search Strategies & Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Aug 25, 2023 9:53 AM

- URL: https://mcphs.libguides.com/public_health_research_experiences

- Queen's University Library

- Research Guides

Public Health

- Writing Literature Reviews

- Evidence-Informed Decision Making

- Defining the Question

- Grey Literature

- Appraising Sources

Introduction

The review article, e-books @ bracken, print books @ queen's library locations, relevant articles, bibliography, related guides.

- Systematic Reviews & Other Syntheses

Article Spotlight

Improving the reliability and accessibility of narrative review articles ( Byrne, 2016 ):

- Is the review article required/important?

- Was the conduct of literature searches defined?

- Were literature citations appropriate and balanced?

- Were original references cited?

- Was information summarised correctly?

- Were studies critically evaluated?

- Are there adequate tables/figures/diagrams?

- Will the review help readers entering the field?

- Does the review expand the body of knowledge?

“ The literature review comes in many shapes and sizes. It is widely used across disciplines because it offers a useful snapshot of the state of research on a particular topic. It provides background and helps to frame research questions and findings in empirical articles, theses, or dissertations. A literature review can also stand alone as an article, providing a valuable overview for those with an interest in the topic. Entire journals are devoted to publishing literature reviews. …

Whether a reviewer is writing about biology or sociology, conducting a qualitative or quantitative review, preparing a literature review as a part of another piece of work, or as its own stand-alone article, every good reviewer of literature must successfully filter large amounts of information into a condensed report that allows others to understand what is currently known about a specific topic ” (Pan, 2016).

Purpose: To summarize and synthesize research that has been done on a particular topic. A review emphasizes important findings in a field and may identify gaps or shortcomings in the research. As it describes and evaluates the studies of others, its primary focus is on what the research has demonstrated through the methodologies and results of study and experimentation.

Audience: Usually a science journal’s broadest readership because a review is more general in its focus than a research article.

- Introduction – introduces the topic and its significance and provides a brief preview of the sub-topics or major trends to be covered in the paper.

- Body – presents a survey of the stages or significant trends in the research. Studies are discussed in groups or clusters often identified with subheadings. To develop the body, the writer must determine criteria for grouping: will studies be clustered according to major advances in the research (chronological development) or areas of consensus or lack of consensus in the field? Will the body highlight similarities and differences in the findings in terms of methods, results, and/or the focus of research studies? *Tips : The body should contain both generalizations about the set of studies under review (written in the present tense) and citations of specific studies (past tense) to identify and verify observed trends. Topic and concluding sentences of paragraphs and/or sections should synthesize research findings and may show differences and similarities or points of agreement/disagreement.

- Conclusion – provides a final general overview of what is known and what is left to explore in the field This section may discuss practical implications or suggest directions for future research.

Distinguishing Elements: The review article is largely descriptive in that it identifies trends or patterns in an area of research across studies. However, analysis is required as the writer offers an interpretation of the state of knowledge in the field, perhaps calling attention to an issue in the field, proposing a theory or model to resolve it, or suggesting directions for future research. As well, unlike research papers that feature functional headings related to the IMRAD format, the review article uses topical or content headings to indicate the sections of the review.

From Types and Conventions of Science Writing by The Writing Centre at Queen's University.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review . PLoS Computational Biology , 9 (7), e1003149 .

- Define a Topic and Audience

- Search and Re-search the Literature

- Take Notes While Reading

- Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

- Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

- Be Critical and Consistent

- Find a Logical Structure

- Make Use of Feedback

- Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

- Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Baker, J. D. (2016). The purpose, process, and methods of writing a literature review . Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal, 103(3), 265-269.

Specific purposes of literature reviews are to:

- Provide a theoretical framework for the specific topic under study;

- Define relevant or key terms and important variables used for a study or manuscript development;

- Provide a synthesized overview of current evidence for practice to gain new perspectives and support assumptions and opinions presented in a manuscript using research studies, quality improvement projects, models, case studies, and so forth;

- Identify the main methodology and research techniques previously used; and

- Demonstrate the gap (distinguishing what has been done from what needs to be done) in the literature, pointing to the significance of the problem and need for the study or building a case for the quality improvement project to be conducted.

Baker, J. D. (2016). The purpose, process, and methods of writing a literature review . Association of Operating Room Nurses Journal, 103(3), 265-269.

Byrne, J. A. (2016). Improving the peer review of narrative literature reviews . Research integrity and peer review, 1(1), 12.

Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Routledge.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review . PLoS Computational Biology, 9(7), e1003149.

- << Previous: Appraising Sources

- Next: Managing Citations & Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 1, 2024 9:56 AM

- Subjects: Health Sciences , Public Health Sciences

- Tags: public health

- University of Detroit Mercy

- Health Professions

Health Services Administration

- Writing a Literature Review

- Find Articles (Databases)

- Evidence-based Practice

- eBooks & Articles

- General Writing Support

- Creating & Printing Posters

- Research Project Web Resources

- Statistics: Health / Medical

- Searching Tips

- Streaming Video

- Database & Library Help

- Medical Apps & Mobile Sites

- Faculty Publications

Literature Review Overview

What is a Literature Review? Why Are They Important?

A literature review is important because it presents the "state of the science" or accumulated knowledge on a specific topic. It summarizes, analyzes, and compares the available research, reporting study strengths and weaknesses, results, gaps in the research, conclusions, and authors’ interpretations.

Tips and techniques for conducting a literature review are described more fully in the subsequent boxes:

- Literature review steps

- Strategies for organizing the information for your review

- Literature reviews sections

- In-depth resources to assist in writing a literature review

- Templates to start your review

- Literature review examples

Literature Review Steps

Graphic used with permission: Torres, E. Librarian, Hawai'i Pacific University

1. Choose a topic and define your research question

- Try to choose a topic of interest. You will be working with this subject for several weeks to months.

- Ideas for topics can be found by scanning medical news sources (e.g MedPage Today), journals / magazines, work experiences, interesting patient cases, or family or personal health issues.

- Do a bit of background reading on topic ideas to familiarize yourself with terminology and issues. Note the words and terms that are used.

- Develop a focused research question using PICO(T) or other framework (FINER, SPICE, etc - there are many options) to help guide you.

- Run a few sample database searches to make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow.

- If possible, discuss your topic with your professor.

2. Determine the scope of your review

The scope of your review will be determined by your professor during your program. Check your assignment requirements for parameters for the Literature Review.

- How many studies will you need to include?

- How many years should it cover? (usually 5-7 depending on the professor)

- For the nurses, are you required to limit to nursing literature?

3. Develop a search plan

- Determine which databases to search. This will depend on your topic. If you are not sure, check your program specific library website (Physician Asst / Nursing / Health Services Admin) for recommendations.

- Create an initial search string using the main concepts from your research (PICO, etc) question. Include synonyms and related words connected by Boolean operators

- Contact your librarian for assistance, if needed.

4. Conduct searches and find relevant literature

- Keep notes as you search - tracking keywords and search strings used in each database in order to avoid wasting time duplicating a search that has already been tried

- Read abstracts and write down new terms to search as you find them

- Check MeSH or other subject headings listed in relevant articles for additional search terms

- Scan author provided keywords if available

- Check the references of relevant articles looking for other useful articles (ancestry searching)

- Check articles that have cited your relevant article for more useful articles (descendancy searching). Both PubMed and CINAHL offer Cited By links

- Revise the search to broaden or narrow your topic focus as you peruse the available literature

- Conducting a literature search is a repetitive process. Searches can be revised and re-run multiple times during the process.

- Track the citations for your relevant articles in a software citation manager such as RefWorks, Zotero, or Mendeley

5. Review the literature

- Read the full articles. Do not rely solely on the abstracts. Authors frequently cannot include all results within the confines of an abstract. Exclude articles that do not address your research question.

- While reading, note research findings relevant to your project and summarize. Are the findings conflicting? There are matrices available than can help with organization. See the Organizing Information box below.

- Critique / evaluate the quality of the articles, and record your findings in your matrix or summary table. Tools are available to prompt you what to look for. (See Resources for Appraising a Research Study box on the HSA, Nursing , and PA guides )

- You may need to revise your search and re-run it based on your findings.

6. Organize and synthesize

- Compile the findings and analysis from each resource into a single narrative.

- Using an outline can be helpful. Start broad, addressing the overall findings and then narrow, discussing each resource and how it relates to your question and to the other resources.

- Cite as you write to keep sources organized.

- Write in structured paragraphs using topic sentences and transition words to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

- Don't present one study after another, but rather relate one study's findings to another. Speak to how the studies are connected and how they relate to your work.

Organizing Information

Options to assist in organizing sources and information :

1. Synthesis Matrix

- helps provide overview of the literature

- information from individual sources is entered into a grid to enable writers to discern patterns and themes

- article summary, analysis, or results

- thoughts, reflections, or issues

- each reference gets its own row

- mind maps, concept maps, flowcharts

- at top of page record PICO or research question

- record major concepts / themes from literature

- list concepts that branch out from major concepts underneath - keep going downward hierarchically, until most specific ideas are recorded

- enclose concepts in circles and connect the concept with lines - add brief explanation as needed

3. Summary Table

- information is recorded in a grid to help with recall and sorting information when writing

- allows comparing and contrasting individual studies easily

- purpose of study

- methodology (study population, data collection tool)

Efron, S. E., & Ravid, R. (2019). Writing the literature review : A practical guide . Guilford Press.

Literature Review Sections

- Lit reviews can be part of a larger paper / research study or they can be the focus of the paper

- Lit reviews focus on research studies to provide evidence

- New topics may not have much that has been published

* The sections included may depend on the purpose of the literature review (standalone paper or section within a research paper)

Standalone Literature Review (aka Narrative Review):

- presents your topic or PICO question

- includes the why of the literature review and your goals for the review.

- provides background for your the topic and previews the key points

- Narrative Reviews: tmay not have an explanation of methods.

- include where the search was conducted (which databases) what subject terms or keywords were used, and any limits or filters that were applied and why - this will help others re-create the search

- describe how studies were analyzed for inclusion or exclusion

- review the purpose and answer the research question

- thematically - using recurring themes in the literature

- chronologically - present the development of the topic over time

- methodological - compare and contrast findings based on various methodologies used to research the topic (e.g. qualitative vs quantitative, etc.)

- theoretical - organized content based on various theories

- provide an overview of the main points of each source then synthesize the findings into a coherent summary of the whole

- present common themes among the studies

- compare and contrast the various study results

- interpret the results and address the implications of the findings

- do the results support the original hypothesis or conflict with it

- provide your own analysis and interpretation (eg. discuss the significance of findings; evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the studies, noting any problems)

- discuss common and unusual patterns and offer explanations

- stay away from opinions, personal biases and unsupported recommendations

- summarize the key findings and relate them back to your PICO/research question

- note gaps in the research and suggest areas for further research

- this section should not contain "new" information that had not been previously discussed in one of the sections above

- provide a list of all the studies and other sources used in proper APA 7

Literature Review as Part of a Research Study Manuscript:

- Compares the study with other research and includes how a study fills a gap in the research.

- Focus on the body of the review which includes the synthesized Findings and Discussion

Literature Reviews vs Systematic Reviews

Systematic Reviews are NOT the same as a Literature Review:

Literature Reviews:

- Literature reviews may or may not follow strict systematic methods to find, select, and analyze articles, but rather they selectively and broadly review the literature on a topic

- Research included in a Literature Review can be "cherry-picked" and therefore, can be very subjective

Systematic Reviews:

- Systemic reviews are designed to provide a comprehensive summary of the evidence for a focused research question

- rigorous and strictly structured, using standardized reporting guidelines (e.g. PRISMA, see link below)

- uses exhaustive, systematic searches of all relevant databases

- best practice dictates search strategies are peer reviewed

- uses predetermined study inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to minimize bias

- aims to capture and synthesize all literature (including unpublished research - grey literature) that meet the predefined criteria on a focused topic resulting in high quality evidence

Literature Review Examples

- Breastfeeding initiation and support: A literature review of what women value and the impact of early discharge (2017). Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives

- Community-based participatory research to promote healthy diet and nutrition and prevent and control obesity among African-Americans: A literature review (2017). Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities

- Vitamin D deficiency in individuals with a spinal cord injury: A literature review (2017). Spinal Cord

Resources for Writing a Literature Review

These sources have been used in developing this guide.

Resources Used on This Page

Aveyard, H. (2010). Doing a literature review in health and social care : A practical guide . McGraw-Hill Education.

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (n.d.). Writing a literature review . Purdue University. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/writing_a_literature_review.html

Torres, E. (2021, October 21). Nursing - graduate studies research guide: Literature review. Hawai'i Pacific University Libraries. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://hpu.libguides.com/c.php?g=543891&p=3727230

- << Previous: General Writing Support

- Next: Creating & Printing Posters >>

- Last Updated: May 21, 2024 11:23 AM

- URL: https://udmercy.libguides.com/hsa

Still accepting applications for online and hybrid programs!

- Skip to content

- Skip to search

- Accessibility Policy

- Report an Accessibility Issue

Literature Reviews

Sample Literature Review (annotated)

Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Alumni and Donors

- Community Partners and Employers

- About Public Health

- How Do I Apply?

- Departments

- Findings magazine

Student Resources

- Career Development

- Certificates

- Internships

- The Heights Intranet

- Update Contact Info

- Report Website Feedback

Prevention & Community Health: Literature Review

- Find Articles

- Maternal & Child Health

- Literature Review

- Test/Survey/Measurement Tools

- Peer-Reviewed Tips

- Types of Studies

- Systematic Review

Good Place to Start: Citation Databases

Interdisciplinary Citation Databases:

A good place to start your research is to search a research citation database to view the scope of literature available on your topic.

TIP #1: SEED ARTICLE Begin your research with a "seed article" - an article that strongly supports your research topic. Then use a citation database to follow the studies published by finding articles which have cited that article, either because they support it or because they disagree with it.

TIP #2: SNOWBALLING Snowballing is the process where researchers will begin with a select number of articles they have identified relevant/strongly supports their topic and then search each articles' references reviewing the studies cited to determine if they are relevant to your research.

BONUS POINTS: This process also helps identify key highly cited authors within a topic to help establish the "experts" in the field.

Begin by constructing a focused research question to help you then convert it into an effective search strategy.

- Identify keywords or synonyms

- Type of study/resources

- Which database(s) to search

- Asking a Good Question (PICO)

- PICO - AHRQ

- PICO - Worksheet

- What Is a PICOT Question?

Web Resources

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a comprehensive and up-to-date overview of published information on a subject area. Conducting a literature review demands a careful examination of a body of literature that has been published that helps answer your research question (See PICO). Literature reviewed includes scholarly journals, scholarly books, authoritative databases, primary sources and grey literature.

A literature review attempts to answer the following:

- What is known about the subject?

- What is the chronology of knowledge about my subject?

- Are there any gaps in the literature?

- Is there a consensus/debate on issues?

- Create a clear research question/statement

- Define the scope of the review include limitations (i.e. gender, age, location, nationality...)

- Search existing literature including classic works on your topic and grey literature

- Evaluate results and the evidence (Avoid discounting information that contradicts your research)

- Track and organize references

- How to conduct an effective literature search.

- Social Work Literature Review Guidelines (OWL Purdue Online Writing Lab)

What is PICO?

The PICO model can help you formulate a good clinical question. Sometimes it's referred to as PICO-T, containing an optional 5th factor.

Seminal Works: Search Key Indexing/Citation Databases

- Google Scholar

- Web of Science

TIP – How to Locate Seminal Works

- DO NOT: Limit by date range or you might overlook the seminal works

- DO: Look at highly cited references (Seminal articles are frequently referred to “cited” in the research)

- DO: Search citation databases like Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar

Search Example

- << Previous: Web Links

- Next: Software >>

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 10:50 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/prevention_and_community_health

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

Public Health Nursing

- How to run your search

Selected titles to help you write a literature review

What is a literature review, systematic literature searching, your search strategy, search strategy elements, tools to help you focus your topic.

- Using One Search

- Specialist Resources for Public Health Nursing

- Evaluating Health Sources

- Keeping track of your sources

- Writing and Referencing

Scribbr (2020) How to write a literature review: 3 minute step-by-step guide. Available at: https://youtu.be/zIYC6zG265E (Accessed: 29 June 2021).

A literature review is a formal search and discussion of the literature published on a topic. Such reviews have different purposes, some providing an overview as a learning exercise. Most literature reviews are related to research activity, focus on scholarly and research publications and how this evidence relates to a specific research question or hypothesis.

Machi and McEvoy (2016, p.23) consider the review process as a critical thinking activity:

- Select a topic (Recognize and define a problem);

- Develop tools of argumentation (Create a process for solving the problem);

- Search the literature (Collect and compile information);

- Survey the literature (Discover the evidence and build the argument);

- Critique the literature (Draw conclusions);

- Write the thesis (Communicate and evaluate the conclusions).

Machi, L.A. and McEvoy, B.T. (2016) The literature review: six steps to success. London; Corwin.

Leite, D., Padilha, M., and Cecatti, J. G. (2019) 'Approaching literature review for academic purposes: The Literature Review Checklist', Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil) , 74 , e1403. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2019/e1403

- Systematic literature searching You might be an undergraduate who wants to improve the quality of their searches, a postgraduate deciding on a dissertation topic, or a PhD student conducting a systematic literature review as part of your thesis. Or, you might be a member of staff conducting systematic search as part of your academic work, grant application, or Knowledge Transfer Partnership (KTP) programme. This guide is your practical companion, offering insights and strategies to navigate the intricacies of systematic searching work.

Literature reviews are often conducted as an introduction to a research project. However, they can also be used to gain an overview of the publications or research or evidence available as an introduction to a topic.

For the latter, you will be expected to develop a systematic search strategy to identify and locate the most relevant material (Aveyard, 2019). This means including, as part of your text, the keywords and resources used for your review and the decisions made regarding your selection of materials.

Aveyard, H. (2019) Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide.4th edn. London: Open University Press, McGraw-Hill Education.

Your search strategy incorporates all the decisions made while selecting items for your literature review.

Themes and keywords

- What are the separate elements of your topic/search?

- Which are the principal key words or search terms for each element?

- Are there obvious alternative search terms that should be included? For example, 'international' could also be described as 'global' or 'worldwide'.

Your initial searches on the topic will help you ascertain relevant search terms.

- Which types of material are you including in your review? This can be restricted to research articles or encompass policy papers, textbooks, reports, conference presentations, blogs and more.

- Which bibliographic resources are most relevant to your topic, and the types of material identified above? Options include bibliographic databases and Google Scholar (journal and research papers); the library's OneSearch (books, exemplars and more), Google or other general search engines (policy papers, blogs ...).See Specialist Resources for links to CINAHL and other bibliographic services.

Additional selection criteria

- Does a specific date range for publication apply?

- Are you only interested in a specific scenario or environment?

- Are you focusing on a specific population?

Please remember:

- Your decision making will be influenced, in part, by the restricted nature of your assignment and related timescale.

- You will be accessing and reading multiple items for each assignment. Some of these will be relevant throughout our programme, or in other contexts. See the Keeping Track of your Sources page on this guide for advice on noting details methodically.

There are several tools available to help researchers formulate a robust research question or hypothesis. These may be helpful in refining your topic and developing a search strategy for your assignments.

- << Previous: How to run your search

- Next: Using One Search >>

- Last Updated: May 17, 2024 1:29 PM

- URL: https://uws-uk.libguides.com/PHN

University of Illinois Chicago

University library, search uic library collections.

Find items in UIC Library collections, including books, articles, databases and more.

Advanced Search

Search UIC Library Website

Find items on the UIC Library website, including research guides, help articles, events and website pages.

- Search Collections

- Search Website

Literature Reviews in Public Health: Home

Public health databases.

View the Public Health Research Guide to view suggestions of databases and websites to search for your literature review.

Literature Review Materials

Use this Excel spreadsheet to track your search and keep your literature review organized.

The accompanying PDF file provides detailed guidelines for conducting a comprehensive literature review.

Have questions about using these materials, or suggestions for improving them? Contact Kim Whalen .

- Literature Review Workbook Use this spreadsheet to keep track of your literature search. Last updated 2/6/2018. DrPH and MHA students: contact me for a version of this workbook adapted to your field.

- Steps in Planning and Implementing a Literature Search

Presentation Slides & Recordings

Literature Review presentation materials available for download and personal use. E-mail Prof Kim Whalen, the librarian for public health, at [email protected] with questions or to schedule a one-on-one conversation.

- Capstone Literature Review Workshop [2018] Library research & writing skills workshop presented on 2/7/2018.

- Capstone Literature Review Workshop [2017] Library research & writing skills workshop presented on 1/31/2017.

- Writing Seminar Presentation 3/29/2016

- Literature Review Workshop 2/16/2016 Slides from PHSA Literature Review Workshop on 2/16/2016.

- 10/27/15 Presentation Slides from class presentation on 10/27/15.

Recommended Reading

These books, available through the library catalog , are recommended for further reading on the literature review process.

Library Faculty

Systematic Review Information

- Systematic Review Search Workbook Use this Excel workbook to document your searches and track results. If you are not conducting a systematic review, use the "Literature Review Workbook" (left).

- EPID 594 Slides 9/7/16 Presentation to EPID 594 course introducing principles & techniques of systematic review searching.

- EPID 594 Slides 9/14/16 Second week's presentation to EPID 594 - searching grey literature and other means of finding evidence.

- Last Updated: May 28, 2024 3:42 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uic.edu/phlitreviews

Global Public Health Research Guide: Literature Reviews

Literature reviews.

- Types of Research Articles

- Database Tutorials

- Medical Reference

- Interlibrary Loans

- Web Resources

- Exporting to PubMed & Web of Science

- RefWorks & Word

- Sharing and Collaborating

What is a Literature Review and Why Do one?

A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Different Approaches to Writing Literature Reviews

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

Adapted from: https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/literature-reviews/ ; https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/literaturereview

What is a Literature Review?

This handout will explain what a literature review is and offer insights into the form and construction of a literature review in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

OK. You've got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a "thumbs up" or "thumbs down" as you leaf through the pages. "Literature review" done. Right?

Wrong! The "literature" of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. "Literature" could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

What is a literature review, then?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

But how is a literature review different from an academic research paper?

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper will contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

Why do we write literature reviews?

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper's investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers.

Who writes these things, anyway?

Literature reviews are written occasionally in the humanities, but mostly in the sciences and social sciences; in experiment and lab reports, they constitute a section of the paper. Sometimes a literature review is written as a paper in itself.

If your assignment is not very specific, seek clarification from your instructor:

- Roughly how many sources should you include?

- What types of sources (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should you summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should you evaluate your sources?

- Should you provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find models

Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word "review" in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read are also excellent entry points into your own research.

Narrow your topic

There are hundreds or even thousands of articles and books on most areas of study. The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good survey of the material. Your instructor will probably not expect you to read everything that's out there on the topic, but you'll make your job easier if you first limit your scope.

And don't forget to tap into your professor's (or other professors') knowledge in the field. Ask your professor questions such as: "If you had to read only one book from the 70's on topic X, what would it be?" Questions such as this help you to find and determine quickly the most seminal pieces in the field.

Consider whether your sources are current

Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. Information even two years old could be obsolete. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period. Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not.

Find a focus

A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized. This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. No. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. Do they present one or different solutions? Is there an aspect of the field that is missing? How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Do they reveal a trend in the field? A raging debate? Pick one of these themes to focus the organization of your review.

Construct a working thesis statement

Then use the focus you've found to construct a thesis statement. Yes! Literature reviews have thesis statements as well! However, your thesis statement will not necessarily argue for a position or an opinion; rather it will argue for a particular perspective on the material. Some sample thesis statements for literature reviews are as follows:

The current trend in treatment for congestive heart failure combines surgery and medicine.

More and more cultural studies scholars are accepting popular media as a subject worthy of academic consideration.

Consider organization

You've got a focus, and you've narrowed it down to a thesis statement. Now what is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? And in what order should you present them? Develop an organization for your review at both a global and local level: