Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the 31 literary devices you must know.

General Education

Need to analyze The Scarlet Letter or To Kill a Mockingbird for English class, but fumbling for the right vocabulary and concepts for literary devices? You've come to the right place. To successfully interpret and analyze literary texts, you'll first need to have a solid foundation in literary terms and their definitions.

In this article, we'll help you get familiar with most commonly used literary devices in prose and poetry. We'll give you a clear definition of each of the terms we discuss along with examples of literary elements and the context in which they most often appear (comedic writing, drama, or other).

Before we get to the list of literary devices, however, we have a quick refresher on what literary devices are and how understanding them will help you analyze works of literature.

What Are Literary Devices and Why Should You Know Them?

Literary devices are techniques that writers use to create a special and pointed effect in their writing, to convey information, or to help readers understand their writing on a deeper level.

Often, literary devices are used in writing for emphasis or clarity. Authors will also use literary devices to get readers to connect more strongly with either a story as a whole or specific characters or themes.

So why is it important to know different literary devices and terms? Aside from helping you get good grades on your literary analysis homework, there are several benefits to knowing the techniques authors commonly use.

Being able to identify when different literary techniques are being used helps you understand the motivation behind the author's choices. For example, being able to identify symbols in a story can help you figure out why the author might have chosen to insert these focal points and what these might suggest in regard to her attitude toward certain characters, plot points, and events.

In addition, being able to identify literary devices can make a written work's overall meaning or purpose clearer to you. For instance, let's say you're planning to read (or re-read) The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis. By knowing that this particular book is a religious allegory with references to Christ (represented by the character Aslan) and Judas (represented by Edmund), it will be clearer to you why Lewis uses certain language to describe certain characters and why certain events happen the way they do.

Finally, literary techniques are important to know because they make texts more interesting and more fun to read. If you were to read a novel without knowing any literary devices, chances are you wouldn't be able to detect many of the layers of meaning interwoven into the story via different techniques.

Now that we've gone over why you should spend some time learning literary devices, let's take a look at some of the most important literary elements to know.

List of Literary Devices: 31 Literary Terms You Should Know

Below is a list of literary devices, most of which you'll often come across in both prose and poetry. We explain what each literary term is and give you an example of how it's used. This literary elements list is arranged in alphabetical order.

An allegory is a story that is used to represent a more general message about real-life (historical) issues and/or events. It is typically an entire book, novel, play, etc.

Example: George Orwell's dystopian book Animal Farm is an allegory for the events preceding the Russian Revolution and the Stalinist era in early 20th century Russia. In the story, animals on a farm practice animalism, which is essentially communism. Many characters correspond to actual historical figures: Old Major represents both the founder of communism Karl Marx and the Russian communist leader Vladimir Lenin; the farmer, Mr. Jones, is the Russian Czar; the boar Napoleon stands for Joseph Stalin; and the pig Snowball represents Leon Trotsky.

Alliteration

Alliteration is a series of words or phrases that all (or almost all) start with the same sound. These sounds are typically consonants to give more stress to that syllable. You'll often come across alliteration in poetry, titles of books and poems ( Jane Austen is a fan of this device, for example—just look at Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility ), and tongue twisters.

Example: "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers." In this tongue twister, the "p" sound is repeated at the beginning of all major words.

Allusion is when an author makes an indirect reference to a figure, place, event, or idea originating from outside the text. Many allusions make reference to previous works of literature or art.

Example: "Stop acting so smart—it's not like you're Einstein or something." This is an allusion to the famous real-life theoretical physicist Albert Einstein.

Anachronism

An anachronism occurs when there is an (intentional) error in the chronology or timeline of a text. This could be a character who appears in a different time period than when he actually lived, or a technology that appears before it was invented. Anachronisms are often used for comedic effect.

Example: A Renaissance king who says, "That's dope, dude!" would be an anachronism, since this type of language is very modern and not actually from the Renaissance period.

Anaphora is when a word or phrase is repeated at the beginning of multiple sentences throughout a piece of writing. It's used to emphasize the repeated phrase and evoke strong feelings in the audience.

Example: A famous example of anaphora is Winston Churchill's "We Shall Fight on the Beaches" speech. Throughout this speech, he repeats the phrase "we shall fight" while listing numerous places where the British army will continue battling during WWII. He did this to rally both troops and the British people and to give them confidence that they would still win the war.

Anthropomorphism

An anthropomorphism occurs when something nonhuman, such as an animal, place, or inanimate object, behaves in a human-like way.

Example: Children's cartoons have many examples of anthropomorphism. For example, Mickey and Minnie Mouse can speak, wear clothes, sing, dance, drive cars, etc. Real mice can't do any of these things, but the two mouse characters behave much more like humans than mice.

Asyndeton is when the writer leaves out conjunctions (such as "and," "or," "but," and "for") in a group of words or phrases so that the meaning of the phrase or sentence is emphasized. It is often used for speeches since sentences containing asyndeton can have a powerful, memorable rhythm.

Example: Abraham Lincoln ends the Gettysburg Address with the phrase "...and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the Earth." By leaving out certain conjunctions, he ends the speech on a more powerful, melodic note.

Colloquialism

Colloquialism is the use of informal language and slang. It's often used by authors to lend a sense of realism to their characters and dialogue. Forms of colloquialism include words, phrases, and contractions that aren't real words (such as "gonna" and "ain't").

Example: "Hey, what's up, man?" This piece of dialogue is an example of a colloquialism, since it uses common everyday words and phrases, namely "what's up" and "man."

An epigraph is when an author inserts a famous quotation, poem, song, or other short passage or text at the beginning of a larger text (e.g., a book, chapter, etc.). An epigraph is typically written by a different writer (with credit given) and used as a way to introduce overarching themes or messages in the work. Some pieces of literature, such as Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick , incorporate multiple epigraphs throughout.

Example: At the beginning of Ernest Hemingway's book The Sun Also Rises is an epigraph that consists of a quotation from poet Gertrude Stein, which reads, "You are all a lost generation," and a passage from the Bible.

Epistrophe is similar to anaphora, but in this case, the repeated word or phrase appears at the end of successive statements. Like anaphora, it is used to evoke an emotional response from the audience.

Example: In Lyndon B. Johnson's speech, "The American Promise," he repeats the word "problem" in a use of epistrophe: "There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem."

A euphemism is when a more mild or indirect word or expression is used in place of another word or phrase that is considered harsh, blunt, vulgar, or unpleasant.

Example: "I'm so sorry, but he didn't make it." The phrase "didn't make it" is a more polite and less blunt way of saying that someone has died.

A flashback is an interruption in a narrative that depicts events that have already occurred, either before the present time or before the time at which the narration takes place. This device is often used to give the reader more background information and details about specific characters, events, plot points, and so on.

Example: Most of the novel Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë is a flashback from the point of view of the housekeeper, Nelly Dean, as she engages in a conversation with a visitor named Lockwood. In this story, Nelly narrates Catherine Earnshaw's and Heathcliff's childhoods, the pair's budding romance, and their tragic demise.

Foreshadowing

Foreshadowing is when an author indirectly hints at—through things such as dialogue, description, or characters' actions—what's to come later on in the story. This device is often used to introduce tension to a narrative.

Example: Say you're reading a fictionalized account of Amelia Earhart. Before she embarks on her (what we know to be unfortunate) plane ride, a friend says to her, "Be safe. Wouldn't want you getting lost—or worse." This line would be an example of foreshadowing because it implies that something bad ("or worse") will happen to Earhart.

Hyperbole is an exaggerated statement that's not meant to be taken literally by the reader. It is often used for comedic effect and/or emphasis.

Example: "I'm so hungry I could eat a horse." The speaker will not literally eat an entire horse (and most likely couldn't ), but this hyperbole emphasizes how starved the speaker feels.

Imagery is when an author describes a scene, thing, or idea so that it appeals to our senses (taste, smell, sight, touch, or hearing). This device is often used to help the reader clearly visualize parts of the story by creating a strong mental picture.

Example: Here's an example of imagery taken from William Wordsworth's famous poem "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud":

When all at once I saw a crowd, A host of golden Daffodils; Beside the Lake, beneath the trees, Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Irony is when a statement is used to express an opposite meaning than the one literally expressed by it. There are three types of irony in literature:

- Verbal irony: When someone says something but means the opposite (similar to sarcasm).

- Situational irony: When something happens that's the opposite of what was expected or intended to happen.

- Dramatic irony: When the audience is aware of the true intentions or outcomes, while the characters are not . As a result, certain actions and/or events take on different meanings for the audience than they do for the characters involved.

- Verbal irony: One example of this type of irony can be found in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado." In this short story, a man named Montresor plans to get revenge on another man named Fortunato. As they toast, Montresor says, "And I, Fortunato—I drink to your long life." This statement is ironic because we the readers already know by this point that Montresor plans to kill Fortunato.

- Situational irony: A girl wakes up late for school and quickly rushes to get there. As soon as she arrives, though, she realizes that it's Saturday and there is no school.

- Dramatic irony: In William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet , Romeo commits suicide in order to be with Juliet; however, the audience (unlike poor Romeo) knows that Juliet is not actually dead—just asleep.

Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition is the comparing and contrasting of two or more different (usually opposite) ideas, characters, objects, etc. This literary device is often used to help create a clearer picture of the characteristics of one object or idea by comparing it with those of another.

Example: One of the most famous literary examples of juxtaposition is the opening passage from Charles Dickens' novel A Tale of Two Cities :

"It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair …"

Malapropism

Malapropism happens when an incorrect word is used in place of a word that has a similar sound. This misuse of the word typically results in a statement that is both nonsensical and humorous; as a result, this device is commonly used in comedic writing.

Example: "I just can't wait to dance the flamingo!" Here, a character has accidentally called the flamenco (a type of dance) the flamingo (an animal).

Metaphor/Simile

Metaphors are when ideas, actions, or objects are described in non-literal terms. In short, it's when an author compares one thing to another. The two things being described usually share something in common but are unalike in all other respects.

A simile is a type of metaphor in which an object, idea, character, action, etc., is compared to another thing using the words "as" or "like."

Both metaphors and similes are often used in writing for clarity or emphasis.

"What light through yonder window breaks? It is the east, and Juliet is the sun." In this line from Romeo and Juliet , Romeo compares Juliet to the sun. However, because Romeo doesn't use the words "as" or "like," it is not a simile—just a metaphor.

"She is as vicious as a lion." Since this statement uses the word "as" to make a comparison between "she" and "a lion," it is a simile.

A metonym is when a related word or phrase is substituted for the actual thing to which it's referring. This device is usually used for poetic or rhetorical effect .

Example: "The pen is mightier than the sword." This statement, which was coined by Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1839, contains two examples of metonymy: "the pen" refers to "the written word," and "the sword" refers to "military force/violence."

Mood is the general feeling the writer wants the audience to have. The writer can achieve this through description, setting, dialogue, and word choice .

Example: Here's a passage from J.R.R. Tolkien's The Hobbit: "It had a perfectly round door like a porthole, painted green, with a shiny yellow brass knob in the exact middle. The door opened on to a tube-shaped hall like a tunnel: a very comfortable tunnel without smoke, with panelled walls, and floors tiled and carpeted, provided with polished chairs, and lots and lots of pegs for hats and coats -- the hobbit was fond of visitors." In this passage, Tolkien uses detailed description to set create a cozy, comforting mood. From the writing, you can see that the hobbit's home is well-cared for and designed to provide comfort.

Onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia is a word (or group of words) that represents a sound and actually resembles or imitates the sound it stands for. It is often used for dramatic, realistic, or poetic effect.

Examples: Buzz, boom, chirp, creak, sizzle, zoom, etc.

An oxymoron is a combination of two words that, together, express a contradictory meaning. This device is often used for emphasis, for humor, to create tension, or to illustrate a paradox (see next entry for more information on paradoxes).

Examples: Deafening silence, organized chaos, cruelly kind, insanely logical, etc.

A paradox is a statement that appears illogical or self-contradictory but, upon investigation, might actually be true or plausible.

Note that a paradox is different from an oxymoron: a paradox is an entire phrase or sentence, whereas an oxymoron is a combination of just two words.

Example: Here's a famous paradoxical sentence: "This statement is false." If the statement is true, then it isn't actually false (as it suggests). But if it's false, then the statement is true! Thus, this statement is a paradox because it is both true and false at the same time.

Personification

Personification is when a nonhuman figure or other abstract concept or element is described as having human-like qualities or characteristics. (Unlike anthropomorphism where non-human figures become human-like characters, with personification, the object/figure is simply described as being human-like.) Personification is used to help the reader create a clearer mental picture of the scene or object being described.

Example: "The wind moaned, beckoning me to come outside." In this example, the wind—a nonhuman element—is being described as if it is human (it "moans" and "beckons").

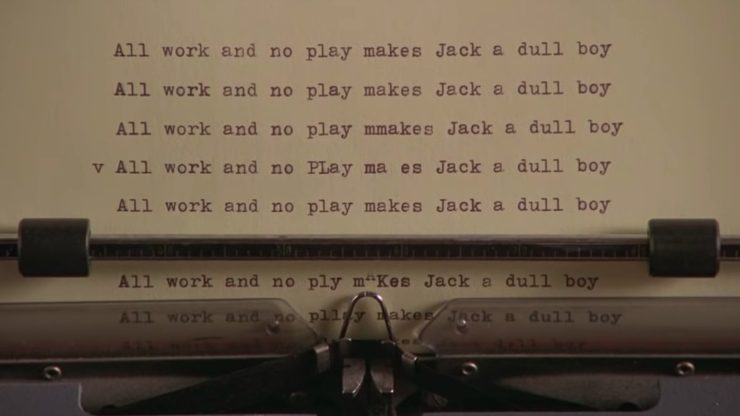

Repetition is when a word or phrase is written multiple times, usually for the purpose of emphasis. It is often used in poetry (for purposes of rhythm as well).

Example: When Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote the score for the hit musical Hamilton, gave his speech at the 2016 Tony's, he recited a poem he'd written that included the following line:

And love is love is love is love is love is love is love is love cannot be killed or swept aside.

Satire is genre of writing that criticizes something , such as a person, behavior, belief, government, or society. Satire often employs irony, humor, and hyperbole to make its point.

Example: The Onion is a satirical newspaper and digital media company. It uses satire to parody common news features such as opinion columns, editorial cartoons, and click bait headlines.

A type of monologue that's often used in dramas, a soliloquy is when a character speaks aloud to himself (and to the audience), thereby revealing his inner thoughts and feelings.

Example: In Romeo and Juliet , Juliet's speech on the balcony that begins with, "O Romeo, Romeo! Wherefore art thou Romeo?" is a soliloquy, as she is speaking aloud to herself (remember that she doesn't realize Romeo's there listening!).

Symbolism refers to the use of an object, figure, event, situation, or other idea in a written work to represent something else— typically a broader message or deeper meaning that differs from its literal meaning.

The things used for symbolism are called "symbols," and they'll often appear multiple times throughout a text, sometimes changing in meaning as the plot progresses.

Example: In F. Scott Fitzgerald's 1925 novel The Great Gatsby , the green light that sits across from Gatsby's mansion symbolizes Gatsby's hopes and dreams .

A synecdoche is a literary device in which part of something is used to represent the whole, or vice versa. It's similar to a metonym (see above); however, a metonym doesn't have to represent the whole—just something associated with the word used.

Example: "Help me out, I need some hands!" In this case, "hands" is being used to refer to people (the whole human, essentially).

While mood is what the audience is supposed to feel, tone is the writer or narrator's attitude towards a subject . A good writer will always want the audience to feel the mood they're trying to evoke, but the audience may not always agree with the narrator's tone, especially if the narrator is an unsympathetic character or has viewpoints that differ from those of the reader.

Example: In an essay disdaining Americans and some of the sites they visit as tourists, Rudyard Kipling begins with the line, "Today I am in the Yellowstone Park, and I wish I were dead." If you enjoy Yellowstone and/or national parks, you may not agree with the author's tone in this piece.

How to Identify and Analyze Literary Devices: 4 Tips

In order to fully interpret pieces of literature, you have to understand a lot about literary devices in the texts you read. Here are our top tips for identifying and analyzing different literary techniques:

Tip 1: Read Closely and Carefully

First off, you'll need to make sure that you're reading very carefully. Resist the temptation to skim or skip any sections of the text. If you do this, you might miss some literary devices being used and, as a result, will be unable to accurately interpret the text.

If there are any passages in the work that make you feel especially emotional, curious, intrigued, or just plain interested, check that area again for any literary devices at play.

It's also a good idea to reread any parts you thought were confusing or that you didn't totally understand on a first read-through. Doing this ensures that you have a solid grasp of the passage (and text as a whole) and will be able to analyze it appropriately.

Tip 2: Memorize Common Literary Terms

You won't be able to identify literary elements in texts if you don't know what they are or how they're used, so spend some time memorizing the literary elements list above. Knowing these (and how they look in writing) will allow you to more easily pinpoint these techniques in various types of written works.

Tip 3: Know the Author's Intended Audience

Knowing what kind of audience an author intended her work to have can help you figure out what types of literary devices might be at play.

For example, if you were trying to analyze a children's book, you'd want to be on the lookout for child-appropriate devices, such as repetition and alliteration.

Tip 4: Take Notes and Bookmark Key Passages and Pages

This is one of the most important tips to know, especially if you're reading and analyzing works for English class. As you read, take notes on the work in a notebook or on a computer. Write down any passages, paragraphs, conversations, descriptions, etc., that jump out at you or that contain a literary device you were able to identify.

You can also take notes directly in the book, if possible (but don't do this if you're borrowing a book from the library!). I recommend circling keywords and important phrases, as well as starring interesting or particularly effective passages and paragraphs.

Lastly, use sticky notes or post-its to bookmark pages that are interesting to you or that have some kind of notable literary device. This will help you go back to them later should you need to revisit some of what you've found for a paper you plan to write.

What's Next?

Looking for more in-depth explorations and examples of literary devices? Join us as we delve into imagery , personification , rhetorical devices , tone words and mood , and different points of view in literature, as well as some more poetry-specific terms like assonance and iambic pentameter .

Reading The Great Gatsby for class or even just for fun? Then you'll definitely want to check out our expert guides on the biggest themes in this classic book, from love and relationships to money and materialism .

Got questions about Arthur Miller's The Crucible ? Read our in-depth articles to learn about the most important themes in this play and get a complete rundown of all the characters .

For more information on your favorite works of literature, take a look at our collection of high-quality book guides and our guide to the 9 literary elements that appear in every story !

These recommendations are based solely on our knowledge and experience. If you purchase an item through one of our links, PrepScholar may receive a commission.

Hannah received her MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan and holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Southern California. From 2013 to 2015, she taught English in Japan via the JET Program. She is passionate about education, writing, and travel.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Common literary devices, such as metaphors and similes, are the building blocks of literature, and what make literature so enchanting. Language evolves through the literary devices in poetry and prose; the different types of figurative language make literature spark in different ways.

Consider this your crash course in common literary devices. Whether you’re studying for the AP Lit exam or looking to improve your creative writing, this article is crammed with literary devices, examples, and analysis.

What are Literary Devices?

- Personification

- Juxtaposition

- Onomatopoeia

- Common Literary Devices in Poetry

- Common Literary Devices in Prose

- Repetition Literary Devices

- Dialogue Literary Devices

- Word Play Literary Devices

- Parallelism Literary Devices

- Rhetorical Devices

Let’s start with the basics. What are literary devices?

Literary devices take writing beyond its literal meaning. They help guide the reader in how to read the piece.

Literary devices are ways of taking writing beyond its straightforward, literal meaning. In that sense, they are techniques for helping guide the reader in how to read the piece.

Central to all literary devices is a quality of connection : by establishing or examining relationships between things, literary devices encourage the reader to perceive and interpret the world in new ways.

One common form of connection in literary devices is comparison. Metaphors and similes are the most obvious examples of comparison. A metaphor is a direct comparison of two things—“the tree is a giant,” for example. A simile is an in direct comparison—“the tree is like a giant.” In both instances, the tree is compared to—and thus connected with—something (a giant) beyond what it literally is (a tree).

Other literary devices forge connections in different ways. For example, imagery, vivid description, connects writing richly to the worlds of the senses. Alliteration uses the sound of words itself to forge new literary connections (“alligators and apples”).

By enabling new connections that go beyond straightforward details and meanings, literary devices give literature its power.

What all these literary devices have in common is that they create new connections: rich layers of sound, sense, emotion, narrative, and ultimately meaning that surpass the literal details being recounted. They are what sets literature apart, and what makes it uniquely powerful.

Read on for an in-depth look and analysis at 112 common literary devices.

Literary Devices List: 14 Common Literary Devices

In this article, we focus on literary devices that can be found in both poetry and prose.

There are a lot of literary devices to cover, each of which require their own examples and analysis. As such, we will start by focusing on common literary devices for this article: literary devices that can be found in both poetry and prose. With each device, we’ve included examples in literature and exercises you can use in your own creative writing.

Afterwards, we’ve listed other common literary devices you might see in poetry, prose, dialogue, and rhetoric.

Let’s get started!

1. Metaphor

Metaphors, also known as direct comparisons, are one of the most common literary devices. A metaphor is a statement in which two objects, often unrelated, are compared to each other.

Example of metaphor: This tree is the god of the forest.

Obviously, the tree is not a god—it is, in fact, a tree. However, by stating that the tree is the god, the reader is given the image of something strong, large, and immovable. Additionally, using “god” to describe the tree, rather than a word like “giant” or “gargantuan,” makes the tree feel like a spiritual center of the forest.

Metaphors allow the writer to pack multiple descriptions and images into one short sentence. The metaphor has much more weight and value than a direct description. If the writer chose to describe the tree as “the large, spiritual center of the forest,” the reader won’t understand the full importance of the tree’s size and scope.

Similes, also known as indirect comparisons, are similar in construction to metaphors, but they imply a different meaning. Like metaphors, two unrelated objects are being compared to each other. Unlike a metaphor, the comparison relies on the words “like” or “as.”

Example of simile: This tree is like the god of the forest. OR: This tree acts as the god of the forest.

What is the difference between a simile and a metaphor?

The obvious difference between these two common literary devices is that a simile uses “like” or “as,” whereas a metaphor never uses these comparison words.

Additionally, in reference to the above examples, the insertion of “like” or “as” creates a degree of separation between both elements of the device. In a simile, the reader understands that, although the tree is certainly large, it isn’t large enough to be a god; the tree’s “godhood” is simply a description, not a relevant piece of information to the poem or story.

Simply put, metaphors are better to use as a central device within the poem/story, encompassing the core of what you are trying to say. Similes are better as a supporting device.

Does that mean metaphors are better than similes? Absolutely not. Consider Louise Gluck’s poem “ The Past. ” Gluck uses both a simile and a metaphor to describe the sound of the wind: it is like shadows moving, but is her mother’s voice. Both devices are equally haunting, and ending the poem on the mother’s voice tells us the central emotion of the poem.

Learn more about the difference between similes and metaphors here:

Simile vs. Metaphor vs. Analogy: Definitions and Examples

Simile and Metaphor Writing Exercise: Tenors and Vehicles

Most metaphors and similes have two parts: the tenor and the vehicle. The tenor refers to the subject being described, and the vehicle refers to the image that describes the tenor.

So, in the metaphor “the tree is a god of the forest,” the tenor is the tree and the vehicle is “god of the forest.”

To practice writing metaphors and similes, let’s create some literary device lists. grab a sheet of paper and write down two lists. In the first list, write down “concept words”—words that cannot be physically touched. Love, hate, peace, war, happiness, and anger are all concepts because they can all be described but are not physical objects in themselves.

In the second list, write down only concrete objects—trees, clouds, the moon, Jupiter, New York brownstones, uncut sapphires, etc.

Your concepts are your tenors, and your concrete objects are your vehicles. Now, randomly draw a one between each tenor and each vehicle, then write an explanation for your metaphor/simile. You might write, say:

Have fun, write interesting literary devices, and try to incorporate them into a future poem or story!

An analogy is an argumentative comparison: it compares two unalike things to advance an argument. Specifically, it argues that two things have equal weight, whether that weight be emotional, philosophical, or even literal. Because analogical literary devices operate on comparison, it can be considered a form of metaphor.

For example:

Making pasta is as easy as one, two, three.

This analogy argues that making pasta and counting upwards are equally easy things. This format, “A is as B” or “A is to B”, is a common analogy structure.

Another common structure for analogy literary devices is “A is to B as C is to D.” For example:

Gordon Ramsay is to cooking as Meryl Streep is to acting.

The above constructions work best in argumentative works. Lawyers and essayists will often use analogies. In other forms of creative writing, analogies aren’t as formulaic, but can still prove to be powerful literary devices. In fact, you probably know this one:

“That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet” — Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare

To put this into the modern language of an analogy, Shakespeare is saying “a rose with no name smells as a rose with a name does.” The name “rose” does not affect whether or not the flower smells good.

Analogy Writing Exercise

Analogies are some of the most common literary devices, alongside similes and metaphors. Here’s an exercise for writing one yourself.

On a blank sheet of paper: write down the first four nouns that come to mind. Try to use concrete, visual nouns. Then, write down a verb. If you struggle to come up with any of these, any old word generator on the internet will help.

The only requirement is that two of your four nouns should be able to perform the verb. A dog can swim, for example, but it can’t fly an airplane.

Your list might look like this:

Verb: Fall Nouns: Rain, dirt, pavement, shadow

An analogy you create from this list might be: “his shadow falls on the pavement how rain falls on the dirt in May.

Your analogy might end up being silly or poetic, strange or evocative. But, by forcing yourself to make connections between seemingly disparate items, you’re using these literary devices to hone the skills of effective, interesting writing.

Is imagery a literary device? Absolutely! Imagery can be both literal and figurative, and it relies on the interplay of language and sensation to create a sharper image in your brain.

Imagery is what it sounds like—the use of figurative language to describe something.

Imagery is what it sounds like—the use of figurative language to describe something. In fact, we’ve already seen imagery in action through the previous literary devices: by describing the tree as a “god”, the tree looks large and sturdy in the reader’s mind.

However, imagery doesn’t just involve visual descriptions; the best writers use imagery to appeal to all five senses. By appealing to the reader’s sense of sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell, your writing will create a vibrant world for readers to live and breathe in.

The best writers use imagery to appeal to all five senses.

Let’s use imagery to describe that same tree. (I promise I can write about more than just trees, but it’s a very convenient image for these common literary devices, don’t you think?)

Notice how these literary device examples also used metaphors and similes? Literary devices often pile on top of each other, which is why so many great works of literature can be analyzed endlessly. Because imagery depends on the object’s likeness to other objects, imagery upholds the idea that a literary device is synonymous with comparison.

Imagery Writing Exercise

Want to try your hand at imagery? You can practice this concept by describing an object in the same way that this article describes a tree! Choose something to write about—any object, image, or idea—and describe it using the five senses. (“This biscuit has the tidy roundness of a lady’s antique hat.” “The biscuit tastes of brand-new cardboard.” and so on!)

Then, once you’ve written five (or more) lines of imagery, try combining these images until your object is sharp and clear in the reader’s head.

Imagery is one of the most essential common literary devices. To learn more about imagery, or to find more imagery writing exercises, take a look at our article Imagery Definition: 5+ Types of Imagery in Literature .

5. Symbolism

Symbolism combines a lot of the ideas presented in metaphor and imagery. Essentially, a symbol is the use of an object to represent a concept—it’s kind of like a metaphor, except more concise!

Symbols are everywhere in the English language, and we often use these common literary devices in speech and design without realizing it. The following are very common examples of symbolism:

A few very commonly used symbols include:

- “Peace” represented by a white dove

- “Love” represented by a red rose

- “Conformity” represented by sheep

- “Idea” represented by a light bulb switching on

The symbols above are so widely used that they would likely show up as clichés in your own writing. (Would you read a poem, written today, that started with “Let’s release the white dove of peace”?) In that sense, they do their job “too well”—they’re such a good symbol for what they symbolize that they’ve become ubiquitous, and you’ll have to add something new in your own writing.

Symbols are often contextually specific as well. For example, a common practice in Welsh marriage is to give your significant other a lovespoon , which the man has designed and carved to signify the relationship’s unique, everlasting bond. In many Western cultures, this same bond is represented by a diamond ring—which can also be unique and everlasting!

Symbolism makes the core ideas of your writing concrete.

Finally, notice how each of these examples are a concept represented by a concrete object. Symbolism makes the core ideas of your writing concrete, and also allows you to manipulate your ideas. If a rose represents love, what does a wilted rose or a rose on fire represent?

Symbolism Writing Exercise

Often, symbols are commonly understood images—but not always. You can invent your own symbols to capture the reader’s imagination, too!

Try your hand at symbolism by writing a poem or story centered around a symbol. Choose a random object, and make that object represent something. For example, you could try to make a blanket represent the idea of loneliness.

When you’ve paired an object and a concept, write your piece with that symbol at the center:

The down blanket lay crumpled, unused, on the empty side of our bed.

The goal is to make it clear that you’re associating the object with the concept. Make the reader feel the same way about your symbol as you do!

6. Personification

Personification, giving human attributes to nonhuman objects, is a powerful way to foster empathy in your readers.

Personification is exactly what it sounds like: giving human attributes to nonhuman objects. Also known as anthropomorphism, personification is a powerful way to foster empathy in your readers.

Think about personification as if it’s a specific type of imagery. You can describe a nonhuman object through the five senses, and do so by giving it human descriptions. You can even impute thoughts and emotions—mental events—to a nonhuman or even nonliving thing. This time, we’ll give human attributes to a car—see our personification examples below!

Personification (using sight): The car ran a marathon down the highway.

Personification (using sound): The car coughed, hacked, and spluttered.

Personification (using touch): The car was smooth as a baby’s bottom.

Personification (using taste): The car tasted the bitter asphalt.

Personification (using smell): The car needed a cold shower.

Personification (using mental events): The car remembered its first owner fondly.

Notice how we don’t directly say the car is like a human—we merely describe it using human behaviors. Personification exists at a unique intersection of imagery and metaphor, making it a powerful literary device that fosters empathy and generates unique descriptions.

Personification Writing Exercise

Try writing personification yourself! In the above example, we chose a random object and personified it through the five senses. It’s your turn to do the same thing: find a concrete noun and describe it like it’s a human.

Here are two examples:

The ancient, threadbare rug was clearly tired of being stepped on.

My phone issued notifications with the grimly efficient extroversion of a sorority chapter president.

Now start writing your own! Your descriptions can be active or passive, but the goal is to foster empathy in the reader’s mind by giving the object human traits.

7. Hyperbole

You know that one friend who describes things very dramatically? They’re probably speaking in hyperboles. Hyperbole is just a dramatic word for being over-dramatic—which sounds a little hyperbolic, don’t you think?

Basically, hyperbole refers to any sort of exaggerated description or statement. We use hyperbole all the time in the English language, and you’ve probably heard someone say things like:

- I’ve been waiting a billion years for this

- I’m so hungry I could eat a horse

- I feel like a million bucks

- You are the king of the kitchen

None of these examples should be interpreted literally: there are no kings in the kitchen, and I doubt anyone can eat an entire horse in one sitting. This common literary device allows us to compare our emotions to something extreme, giving the reader a sense of how intensely we feel something in the moment.

This is what makes hyperbole so fun! Coming up with crazy, exaggerated statements that convey the intensity of the speaker’s emotions can add a personable element to your writing. After all, we all feel our emotions to a certain intensity, and hyperbole allows us to experience that intensity to its fullest.

Hyperbole Writing Exercise

To master the art of the hyperbole, try expressing your own emotions as extremely as possible. For example, if you’re feeling thirsty, don’t just write that you’re thirsty, write that you could drink the entire ocean. Or, if you’re feeling homesick, don’t write that you’re yearning for home, write that your homeland feels as far as Jupiter.

As a specific exercise, you can try writing a poem or short piece about something mundane, using more and more hyperbolic language with each line or sentence. Here’s an example:

A well-written hyperbole helps focus the reader’s attention on your emotions and allows you to play with new images, making it a fun, chaos-inducing literary device.

Is irony a literary device? Yes—but it’s often used incorrectly. People often describe something as being ironic, when really it’s just a moment of dark humor. So, the colloquial use of the word irony is a bit off from its official definition as a literary device.

Irony is when the writer describes something by using opposite language. As a real-life example, if someone is having a bad day, they might say they’re doing “ greaaaaaat ”, clearly implying that they’re actually doing quite un-greatly. Or a story’s narrator might write:

Like most bureaucrats, she felt a boundless love for her job, and was eager to share that good feeling with others.

In other words, irony highlights the difference between “what seems to be” and “what is.” In literature, irony can describe dialogue, but it also describes ironic situations : situations that proceed in ways that are elaborately contrary to what one would expect. A clear example of this is in The Wizard of Oz . All of the characters already have what they are looking for, so when they go to the wizard and discover that they all have brains, hearts, etc., their petition—making a long, dangerous journey to beg for what they already have—is deeply ironic.

Irony Writing Exercise

For verbal irony, try writing a sentence that gives something the exact opposite qualities that it actually has:

The triple bacon cheeseburger glistened with health and good choices.

For situational irony, try writing an imagined plot for a sitcom, starting with “Ben lost his car keys and can’t find them anywhere.” What would be the most ironic way for that situation to be resolved? (Are they sitting in plain view on Ben’s desk… at the detective agency he runs?) Have fun with it!

9. Juxtaposition

Juxtaposition refers to the placement of contrasting ideas next to each other, often to produce an ironic or thought-provoking effect. Writers use juxtaposition in both poetry and prose, though this common literary device looks slightly different within each realm of literature.

In poetry, juxtaposition is used to build tension or highlight an important contrast. Consider the poem “ A Juxtaposition ” by Kenneth Burke, which juxtaposes nation & individual, treble & bass, and loudness & silence. The result is a poem that, although short, condemns the paradox of a citizen trapped in their own nation.

Just a note: these juxtapositions are also examples of antithesis , which is when the writer juxtaposes two completely opposite ideas. Juxtaposition doesn’t have to be completely contrarian, but in this poem, it is.

Juxtaposition accomplishes something similar in prose. A famous example comes from the opening A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of time.” Dickens opens his novel by situating his characters into a world of contrasts, which is apt for the extreme wealth disparities pre-French Revolution.

Juxtaposition Writing Exercise

One great thing about juxtaposition is that it can dismantle something that appears to be a binary. For example, black and white are often assumed to be polar opposites, but when you put them next to each other, you’ll probably get some gray in the middle.

To really master the art of juxtaposition, try finding two things that you think are polar opposites. They can be concepts, such as good & evil, or they can be people, places, objects, etc. Juxtapose your two selected items by starting your writing with both of them—for example:

Across the town from her wedding, the bank robbers were tying up the hostages.

I put the box of chocolates on the coffee table, next to the gas mask.

Then write a poem or short story that explores a “gray area,” relationship, commonality, or resonance between these two objects or events—without stating as much directly. If you can accomplish what Dickens or Burke accomplishes with their juxtapositions, then you, too, are a master!

10. Paradox

A paradox is a juxtaposition of contrasting ideas that, while seemingly impossible, actually reveals a deeper truth. One of the trickier literary devices, paradoxes are powerful tools for deconstructing binaries and challenging the reader’s beliefs.

A simple paradox example comes to us from Ancient Rome.

Catullus 85 ( translated from Latin)

I hate and I love. Why I do this, perhaps you ask. I know not, but I feel it happening and I am tortured.

Often, “hate” and “love” are assumed to be opposing forces. How is it possible for the speaker to both hate and love the object of his affection? The poem doesn’t answer this, merely telling us that the speaker is “tortured,” but the fact that these binary forces coexist in the speaker is a powerful paradox. Catullus 85 asks the reader to consider the absoluteness of feelings like hate and love, since both seem to torment the speaker equally.

Another paradox example comes from Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

“To be natural is such a very difficult pose to keep up.”

Here, “natural” and “pose” are conflicting ideas. Someone who poses assumes an unnatural state of being, whereas a natural poise seems effortless and innate. Despite these contrasting ideas, Wilde is exposing a deeper truth: to seem natural is often to keep up appearances, and seeming natural often requires the same work as assuming any other pose.

Note: paradox should not be confused with oxymoron. An oxymoron is also a statement with contrasting ideas, but a paradox is assumed to be true, whereas an oxymoron is merely a play on words (like the phrase “same difference”).

Paradox Writing Exercise

Paradox operates very similarly to literary devices like juxtaposition and irony. To write a paradox, juxtapose two binary ideas. Try to think outside of the box here: “hate and love” are an easy binary to conjure, so think about something more situational. Wilde’s paradox “natural and pose” is a great one; another idea could be the binaries “awkward and graceful” or “red-handed and innocent.”

Now, situate those binaries into a certain situation, and make it so that they can coexist. Imagine a scenario in which both elements of your binary are true at the same time. How can this be, and what can we learn from this surprising juxtaposition?

11. Allusion

If you haven’t noticed, literary devices are often just fancy words for simple concepts. A metaphor is literally a comparison and hyperbole is just an over-exaggeration. In this same style, allusion is just a fancy word for a literary reference; when a writer alludes to something, they are either directly or indirectly referring to another, commonly-known piece of art or literature.

The most frequently-alluded to work is probably the Bible. Many colloquial phrases and ideas stem from it, since many themes and images from the Bible present themselves in popular works, as well as throughout Western culture. Any of the following ideas, for example, are Biblical allusions:

- Referring to a kind stranger as a Good Samaritan

- Describing an ideal place as Edenic, or the Garden of Eden

- Saying someone “turned the other cheek” when they were passive in the face of adversity

- When something is described as lasting “40 days and 40 nights,” in reference to the flood of Noah’s Ark

Of course, allusion literary devices aren’t just Biblical. You might describe a woman as being as beautiful as the Mona Lisa, or you might call a man as stoic as Hemingway.

Why write allusions? Allusions appeal to common experiences: they are metaphors in their own right, as we understand what it means to describe an ideal place as Edenic.

Like the other common literary devices, allusions are often metaphors, images, and/or hyperboles. And, like other literary devices, allusions also have their own sub-categories.

Allusion Writing Exercise

See how densely you can allude to other works and experiences in writing about something simple. Go completely outside of good taste and name-drop like crazy:

Allusions (way too much version): I wanted Nikes, not Adidas, because I want to be like Mike. But still, “a rose by any other name”—they’re just shoes, and “if the shoe fits, wear it.”

From this frenetic style of writing, trim back to something more tasteful:

Allusions (more tasteful version): I had wanted Nikes, not Adidas—but “if the shoe fits, wear it.”

12. Allegory

An allegory is a story whose sole purpose is to represent an abstract concept or idea. As such, allegories are sometimes extended allusions, but the two common literary devices have their differences.

For example, George Orwell’s Animal Farm is an allegory for the deterioration of Communism during the early establishment of the U.S.S.R. The farm was founded on a shared goal of overthrowing the farming elite and establishing an equitable society, but this society soon declines. Animal Farm mirrors the Bolshevik Revolution, the overthrow of the Russian aristocracy, Lenin’s death, Stalin’s execution of Trotsky, and the nation’s dissolution into an amoral, authoritarian police state. Thus, Animal Farm is an allegory/allusion to the U.S.S.R.:

Allusion (excerpt from Animal Farm ):

“There were times when it seemed to the animals that they worked longer hours and fed no better than they had done in [Farmer] Jones’s day.”

However, allegories are not always allusions. Consider Plato’s “ Allegory of the Cave ,” which represents the idea of enlightenment. By representing a complex idea, this allegory could actually be closer to an extended symbol rather than an extended allusion.

Allegory Writing Exercise

Pick a major trend going on in the world. In this example, let’s pick the growing reach of social media as our “major trend.”

Next, what are the primary properties of that major trend? Try to list them out:

- More connectedness

- A loss of privacy

- People carefully massaging their image and sharing that image widely

Next, is there something happening at—or that could happen at—a much smaller scale that has some or all of those primary properties? This is where your creativity comes into play.

Well… what if elementary school children not only started sharing their private diaries, but were now expected to share their diaries? Let’s try writing from inside that reality:

I know Jennifer McMahon made up her diary entry about how much she misses her grandma. The tear smudges were way too neat and perfect. Anyway, everyone loved it. They photocopied it all over the bulletin boards and they even read it over the PA, and Jennifer got two extra brownies at lunch.

Try your own! You may find that you’ve just written your own Black Mirror episode.

13. Ekphrasis

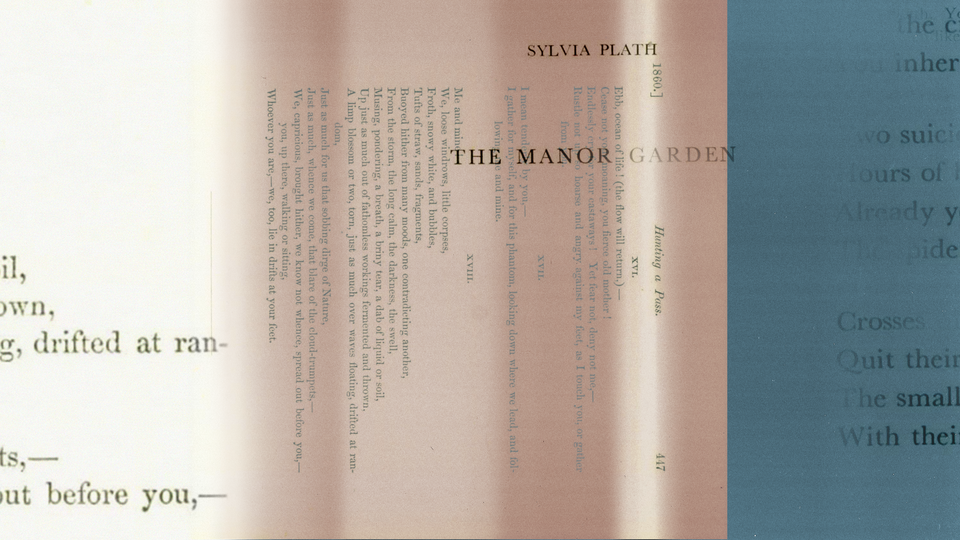

Ekphrasis refers to a poem or story that is directly inspired by another piece of art. Ekphrastic literature often describes another piece of art, such as the classic “ Ode on a Grecian Urn ”:

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede Of marble men and maidens overwrought, With forest branches and the trodden weed; Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral! When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.”

Ekphrasis can be considered a direct allusion because it borrows language and images from other artwork. For a great example of ekphrasis—as well as a submission opportunity for writers!—check out the monthly ekphrastic challenge that Rattle Poetry runs.

Ekphrasis writing exercise

Try your hand at ekphrasis by picking a piece of art you really enjoy and writing a poem or story based off of it. For example, you could write a story about Mona Lisa having a really bad day, or you could write a black-out poem created from the lyrics of your favorite song.

Or, try Rattle ‘s monthly ekphrastic challenge ! All art inspires other art, and by letting ekphrasis guide your next poem or story, you’re directly participating in a greater artistic and literary conversation.

14. Onomatopoeia

Flash! Bang! Wham! An onomatopoeia is a word that sounds like the noise it describes. Conveying both a playfulness of language and a serious representation of everyday sounds, onomatopoeias draw the reader into the sensations of the story itself.

Onomatopoeia words are most often used in poetry and in comic books, though they certainly show up in works of prose as well. Some onomatopoeias can be found in the dictionary, such as “murmur,” “gargle,” and “rumble,” “click,” and “vroom.” However, writers make up onomatopoeia words all the time, so while the word “ptoo” definitely sounds like a person spitting, you won’t find it in Merriam Webster’s.

Here’s an onomatopoeia example, from the poem “Honky Tonk in Cleveland, Ohio” by Carl Sandburg .

The onomatopoeias have been highlighted in bold. These common literary devices help make your writing fresh, interesting, and vivid, creating a sonic setting that the reader can fall into.

Learn more about onomatopoeias here!

Onomatopoeia Writing Exercise

Onomatopoeias are fun literary devices to use in your work, so have fun experimenting with them. In this exercise, take a moment to listen to the noises around you. Pay close attention to the whir of electronics, the fzzzzzzz of the heater, the rumbling of cars on the street, or the tintintintintin of rain on the roof.

Whatever you hear, convert those sounds into onomatopoeias. Make a list of those sounds. Try to use a mix of real words and made up ones: the way you represent noise in language can have a huge impact on your writing style .

Do this for 5 to 10 minutes, and when you have a comprehensive list of the sounds you hear, write a poem or short story that uses every single word you’ve written down.

If you built your political campaign off of wordplay, would you be punning for president?

A pun is a literary device that plays with the sounds and meanings of words to produce new, often humorous ideas. For example, let’s say you used too much butter in your recipe, and it ruined the dish. You might joke that you were “outside the margarine of error,” which is a play on the words “margin of error.”

Puns have a rich literary history, and famous writers like Shakespeare and Charles Dickens, as well as famous texts like The Bible, have used puns to add depth and gravity to their words.

Pun Writing Exercise

Jot down a word or phrase that you commonly use. If you’re not sure of what to write down, take a look at this list of English idioms . For example, I might borrow the phrase “blow off steam,” which means to let out your anger.

Take any saying, and play around with the sounds and meanings of the words in that saying. Then, incorporate the new phrase you’ve created into a sentence that allows for the double meaning of the phrase. Here’s two examples:

If I play with the sound of the words, I might come up with “blowing off stream.” Then, I would put that into a sentence that plays with the original meaning of the phrase. Like: “Did you hear about the river boat that got angry and went off course? It was blowing off stream.”

Or, I might play with the meanings of words. For example, I might take the word “blowing” literally, and write the following: “someone who cools down their tea when they’re angry is blowing off steam.”

Searching for ways to add double meanings and challenge the sounds of language will help you build fresh, exciting puns. Learn more about these common literary devices in our article on puns in literature .

16–27. Common Literary Devices in Poetry

The following 12 devices apply to both poetry and prose writers, but they appear most often in verse. Learn more about:

- Metonymy/Synecdoche

- Alliteration

- Consonance/Assonance

- Euphony/Cacophony

12 Literary Devices in Poetry: Identifying Poetic Devices

28–37. Common Literary Devices in Prose

The following 10 devices show up in verse, but are far more prevalent in prose. Learn more about:

- Parallel Plot

- Foreshadowing

- In Media Res

- Dramatic Irony

10 Important Literary Devices in Prose: Examples & Analysis

38–48. Repetition Literary Devices

Though they have uncommon names, these common literary devices are all forms of repetition.

- Anadiplosis

- Anaphora (prose)

- Antanaclasis

- Antimetabole

- Antistrophe

- Epanalepsis

Repetition Definition: Types of Repetition in Poetry and Prose

49–57. Dialogue Literary Devices

While these literary elements pertain primarily to dialogue, writers use euphemisms, idioms, and neologisms all the time in their work.

- Colloquialism

How to Write Dialogue in a Story

58–67. Word Play Literary Devices

The following literary devices push language to the limits. Have fun with these!

- Double Entendre

- Malapropism

- Paraprosdokian

- Portmanteau

Word Play: Examples of a Play on Words

68–72. Parallelism Literary Devices

Parallelism is a stylistic device where a sentence is composed of equally weighted items. In essence, parallel structure allows form to echo content. Learn all about this essential stylistic literary device below.

- Grammatical parallelism

- Rhetorical parallelism

- Synthetic parallelism

- Antithetical parallelism

- Synonymous parallelism

Parallelism Definition: Writing With Parallel Structure

73–112. Rhetorical Devices

Rhetorical devices are literary devices intended to persuade the reader of something. You might have heard of ethos, pathos, and logos, but do you know your aposiopesis from your hyperbaton?

Many literary devices can also be considered rhetorical devices. After all, a metaphor can convince you of something just as well as a syllogism. Nonetheless, the following 40 rhetorical/literary devices will sharpen your style, argumentation, and writing abilities.

- Anacoluthon

- Polysyndeton

- Procatalepsis

- Reductio ad Absurdum

- Amplification

- Antiphrasis

- Overstatement

- Adnomination

- Aposiopesis

- Circumlocution

Common Rhetorical Devices List: The Art of Argument

Master These Common Literary Devices With Writers.com!

The instructors at Writers.com are masters of literary devices. Through masterful instruction and personal expertise, our instructors can help you add, refine, and improve your literary devices, helping you craft great works of literature. Check out our upcoming courses , and join our writing community on Facebook !

Sean Glatch

96 comments.

Very nice the litrery divices

Brilliant litery devices

Love this article thank you

My stoonts confess to having trouble with “poultry”.

I love this literary term it help a lot

thank you this was life-changing

Broaden the vucablry it does

Very effectively and simply elaborated

I am trying think of the specific literary structure based on loosely assembled episodes set within the framework of a journey: it is not quixotic, peripatetic, itinerant…always on the tip of my tongue. Help!

enjoyed this (and learned some new things, too). HB

Wow, very educating and nice! Quite helpful

It is very nice visiting this site.

This was put together profoundly; thank you! As a writer, you can never learn enough. I will begin incorporating these into my stories. Words can’t express how helpful this was, and it was very efficiently put together as well, so kudos to that!

I’m so happy this article helped you, Jalen! Happy writing!

Thank you for this article! It really helped a lot! hands up to the good samaritan of understanding literature :D.

But I would have one last question: Would any sort of intertextuality be considered an Allusion? (Also when you refer to the author for example?)

Great questions! That’s a great way to think about allusion–any sort of intertextuality is indeed allusive. In fact, your use of “Good Samaritan” is an allusion to the Bible, even if you didn’t mean it to be!

And yes, because an allusion is anything referential, then a reference to another author also counts as an allusion. Of course, it can’t be directly stated: “She’s reading Shakespeare” doesn’t count, but “She worships the Immortal Bard” would be an allusion. (It’s also an allusion to the story of the same name by Isaac Asimov).

I’m glad to hear our article was helpful. Happy reading!

This will help! Thanks!

There is also Onomatopoeia, you can make the list 45

This article really helped me, the techniques are amazing, and the detail is incredible. Thank you for taking your time to write this!

I’m so glad this was helpful, Gwen! Happy writing!

this was useful 🙂 thanks

I love personification; you can do so much with it.

Hi, I’m really sorry but I am still confused with juxtaposition.

Hi Nate! Juxtaposition simply describes when contrasting ideas are placed next to each other. The effect of juxtaposition depends on the ideas that are being juxtaposed, but the point is to surprise or provoke the reader.

Take, for example, the opening line of Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Here, happy and unhappy families are being juxtaposed, and the contrast between the two is meant to provoke the reader and highlight the differences between those families. This juxtaposition sets up the novel as a whole, which often discusses themes of family and happiness (among many other themes).

I hope this helps!

very nice indeed

[…] 33 Common Literary Devices: Definitions, Examples, and Exercises […]

[…] 44 Common Literary Devices: Definitions, Examples, and Exercises […]

Thanks a lot for this it was really nice, good and fun to read it and it was really helpful for me as a student👔so please keep up with the good work 😉🌹💖😚😍💝💞💐

VERY GOOD READ I LOVED IT SO MUCH YAY QUEEEEEEEENNNNNN

Really helping. It’s a wonderful article

O mother Ghana, teach your children to change their negative attitudes towards you and what you have Please which literary device is this?

The device employed here is called apostrophe, which is when the writer addresses something not actually present for literary effect. Read more about it at this link .

This was very effective towards my writing and my family really enoyed seeing how much I had learnt. Thanks a lot.

so irony is literally sarcasm then

Sometimes! Sarcasm is a form of verbal irony.

Verbal irony occurs when a person intentionally says the opposite of what they mean. For example, you might say “I’m having the best day ever” after getting hit by a car.

Sarcasm is the use of verbal irony with the intent of mocking someone or something. You might say “Good going, genius” to someone who made a silly mistake, implying they’re not a genius at all.

Hope that makes sense!

Love this article! I used to struggle in my literature class, but after reading though this article, I certainly improved! Thanks! However, I have one question I really need your help with- Can I assume that a phrase which is the slightest bit plausible, a hyperbole? For example, a young elementary student who is exceptionally talented in basketball, to such an extent that he was quite famous nation-wide, said that he would be the next Lebron James although he was still very young. Would this be considered as a hyperbole? It would be great if you can help me with this.

That’s a great question! Although that claim is certainly exaggerated, it probably wouldn’t be hyperbole, because the child believes it to be true. A hyperbole occurs when the writer makes an exaggerated statement that they know to be false–e.g. “I’ve been waiting a billion years for this.”

Of course, if the child is self-aware and knows they’re just being cheeky, then it would be hyperbole, but I get the sense that the child genuinely believes they’re the next Lebron. 🙂

I’m glad this article has helped you in your literature class!

That makes a lot of sense, thanks for your reply!

Sorry, I have another question related to hyperbole. This is an extract from Animal Farm:

“Squealer was sent to make the necessary explanation to the others. ‘Comrades!’ he cried. ‘You do not imagine, I hope, that we pigs are doing this in a spirit of selfishness and privilege? Many of us actually dislike milk and apples. I dislike them myself. Our sole object in taking these things is to preserve our health. Milk and apples (this has been proved by Science, comrades) contain substances absolutely necessary to the well being of a pig. We pigs are brain-workers. The whole management and organisation of this farm depend on us. Day and night we are watching over your welfare. It is for your sake that we drink that milk and eat those apples. Do you know what would happen if we pigs failed in our duty? Jones would come back! Yes, Jones would come back! Surely, comrades,’ cried Squealer almost pleadingly, skipping from side to side and whisking his tail, ‘surely there is no one among you who wants to see Jones come back?’ Now if there was one thing that the animals were completely certain of, it was that they did not want Jones back. When it was put to them in this light, they had no more to say. The importance of keeping the pigs in good health was all too obvious.”

May I know if the speech made by Squealer in this extract is a hyperbole, gaslight (I’m not sure if this is a literary device), or some other device(s)? I know this is very wordy so you can take your time, no rush.

(I am doing a chapter analysis of chapter 3 in Animal Farm)

By the way, if you have written any other articles, please let me know! I would like to read them, thanks!

Take a look at writers.com/writing-tips for our archive on the craft of writing!

It wouldn’t be hyperbole, as a hyperbole is usually a word or phrase, not an entire passage of text. It’s better to analyze this passage in terms of its rhetorical strategies: Squealer is appealing to nebulous ideas like Science and the return of Jones–appeals to logos and pathos, despite there being a lack of evidence.

These strategies are logical fallacies: arguments that are easily disproven through reasoning, but which often resonate when people don’t employ critical thinking. Some of the fallacies here are “appeal to fear” and the “false dilemma” that Jones will return if the pigs don’t eat apples and milk (this is also a “red herring”).

I can’t provide much more help than this, as I don’t want to write your assignment for you, but I’m happy to point you in this direction, because understanding how logical fallacies are abused is essential to being an informed reader and citizen. 🙂

Ok, thanks for your reply!

Thank you! I am studying for an English final and this was a life saver!

My pleasure, Isla, good luck on your final!

I have a literature exam coming up,so this was much needed.Thank you!

Indeed this has been of great help to me.

I am so greatful of this website it really helps me a lot about myself and my family

This is awesome

This website is very useful to understand litery devices…

thanks it was helpful

Hi what is the name of the literary device where you name a character after their personality eg. Mr Knighley, Miss honey or Miss Trunchball? Thank you

That’s called an “aptronym”!

Mind blowing indeed. I had no idea there were so many names for patterns I hear people use with words. This lis is great as is. I am using it to probe further into what they are. I would only suggest that if the time ever allowed for someone to provide a brief detail or definition to each it would save a lot of time for many like me. None the less, I am grateful for the work provided. Thank you.

It awesome and amazing

It is personification as well as apostrophe, as Sean suggested. Ghana (the nation, I am assuming) is personified as a mother who is able to teach her citizens (children) to change their negative attitudes towards her.

Helped alot😊

This has truly helped me alot. Definitely great

Thanks so much, I never knew the list to this was as tall as everest, way back in school I didn’t take lit lessons serious and forgot everything til it came to mind to revise these devices And here google landed me, and thanks again so much.

This is awesome,it truly help me alot

It was great fun I had an amazing time doing the literary exercises and they helped so much. They really expanded my knowledge of the entire topic it was a wonderful thing to read, it will definitely help me with any English essay I have in the future.

It was very helpful. I must say that I have a better understanding of these literary devices. It was wonderful reading them.

I am overjoyed in knowing that we have different types of literary devices in literature. Thank you for this interesting article.

This is excellent and amazing.

This information was very useful Appreciated 🤗🙏

Thank you so much, I was literarily dying because of my English final!! I needed all these literal devices.

This article has really elevated me in the world of Literature.Thanks sir

This information is very important to me in my education . Thank you very much.

The articles are well written and the concepts well explained to the understanding of a beginner. The simplified way the author explained every term makes the article not only an interesting read but also a good note for teaching.

The litrarery device is the best way to get a knowledge in education

I liked it and the English is understandable

Can Dystopia be considered a kind of literary device?

Thank you so much for this! It helped me get ready for my English exam.

Best of luck on your exam, Olive!

Thank you so much! I learned so much that I can use in my upcoming assignments for writing.

Thank you so much . I learned so much understanding of my semester exams

Exactly this was really really helpful to everyone including me

[…] https://writers.com/common-literary-devices […]

Great definition and examples

I love this so much

[…] 112 Common Literary Devices: Definitions, Examples, and Exercises […]

This was Uber helpful! BUT, I do wish that we got more examples, and I can see why you made it shorter. If you put examples for all of them, then this would be really long.

Thanks! So detailed

Yah! That’s really the fact.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Find at OUP.com

- Google Preview

The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (3 ed.)

Chris baldick.

“This dictionary’s virtues and its plain-spokenness make it ... as apt to the bedside table as to the desk: Dr Baldick is a Brewer for specialized tastes” - Times Literary Supplement

The best-selling Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (formerly the Concise dictionary) provides clear, concise, and often witty definitions of the most troublesome literary terms from abjection to zeugma. Now available in a new, fully updated and expanded edition, it offers readers increased coverage of new terms from modern critical and theoretical movements, such as feminism, and schools of American poetry, Spanish verse forms, life writing, and crime fiction.

It includes extensive coverage of traditional drama, versification, rhetoric, and literary history, as well as updated and extended advice on recommended further reading and a pronunciation guide to more than 200 terms. New to this fully revised edition are recommended entry-level web links. Boasting over 1,200 entries, it is an essential reference tool for students of literature in any language.

Bibliographic Information

Affiliations are at time of print publication..

Chris Baldick is Professor of English at Goldsmiths’ College, University of London. He has written widely on nineteenth-century literature and is the editor of The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales .

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

- All Contents

Access to the complete content on Oxford Reference requires a subscription or purchase. Public users are able to search the site and view the abstracts and keywords for each book and chapter without a subscription.

Please subscribe or login to access full text content.

If you have purchased a print title that contains an access token, please see the token for information about how to register your code.

For questions on access or troubleshooting, please check our FAQs , and if you can''t find the answer there, please contact us .

abridgement

Absurd, the, academic drama, acatalectic, accentual verse, adventure story, aestheticism, front matter, publishing information, general links for this work, pronunciation.

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 11 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|195.158.225.244]

- 195.158.225.244

Character limit 500 /500

Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, what are literary devices.