Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

POVERTY IN PAKISTAN: A REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Related Papers

The Pakistan Development Review

DR. MAQBOOL HUSSAIN SIAL

The key development objective of Pakistan, since its existence, has been to reduce poverty, inequality and to improve the condition of its people. While this goal seems very important in itself yet is also necessary for the eradication of other social, political and economic problems. The objective to eradicate poverty has remained same but methodology to analysing this has changed. It can be said that failure of most of the poverty strategies is due to lack of clear choice of poverty definition. A sound development policy including poverty alleviation hinges upon accurate and well-defined measurements of multidimensional socio-economic characteristics which reflect the ground realities confronting the poor and down trodden rather than using some abstract/income based criteria for poverty measurement. Conventionally welfare has generally been measured using income or expenditures criteria. Similarly, in Pakistan poverty has been measured mostly in uni-dimension, income or expenditur...

Dr. Tanweer Ul Islam

Asad Zaman , Taseer Salahuddin

Abstract: Traditionally poverty has been understood only as 'lack of income'. However, with the passage of time it was realized that poverty is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon. Mahboob-ul-Haq (1973) and Sen (1975) argued that development is about enlarging human capabilities, rather than only acquisition of wealth. The purpose of this research is to argue that poverty being multidimensional in nature, cannot be properly measured by unidimensional (income or calorie based) poverty measures.

Dr. Tanweer Islam

This paper argues for the multidimensional measurement of poverty in Pakistan particularly in the context of Millennium Development Goals. It critically examines the Poverty Scorecard, which was recently introduced by the Government of Pakistan for the identification of poor households under the Benazir Income Support Programme. By employing the Alkire and Foster measure to analyze household data from two provinces, Khyber-Pakhtoonkhwah3 and Punjab, it provides an alternative method to estimate multidimensional poverty and identify poor households. The paper also investigates the relationship between household consumption and multidimensional poverty. It contrasts the results obtained by using a multidimensional measurement of poverty with those of the official poverty line. The limitations of the official poverty line are identified and the role of household consumption in explaining deprivations is discussed.

Arif Naveed

This paper argues for the multidimensional measurement of poverty in Pakistan particularly in the context of Millennium Development Goals. It critically examines the Poverty Scorecard, which was recently introduced by the Government of Pakistan for the identification of poor households under the Benazir Income Support Programme. By employing the Alkire and Foster measure to analyze household data from two provinces, Khyber-Pakhtoonkhwah (the re-named North-West Frontier Province) and Punjab, it provides an alternative method to estimate multidimensional poverty and identify poor households. The paper also investigates the relationship between household consumption and multidimensional poverty. It contrasts the results obtained by using a multidimensional measurement of poverty with those of the official poverty line. The limitations of the official poverty line are identified and the role of household consumption in explaining deprivations is discussed.

Maria José Santos

Sandr Harrell

MaxForce Keto:-https://www.healthdietalert.com/maxforce-keto/ I've had mediocre results with MaxForce Keto. That is not going to be a lecture on MaxForce Keto, although you might need to give that stuff quite a few thought. You should develop a mental picture of MaxForce Keto. Visit here to get more details>>https://www.healthdietalert.com/maxforce-keto/

Elias Safatly

RELATED PAPERS

Ammar Belal

Mebrahten N G U S E Abrha

Publica: Jurnal Pemikiran Administrasi Negara

Revi Pravira Pangestuti

Luis Picado-Santos

ELVIRA M R PEDROSA

Carmen Valero-Garcés

Aquatic Sciences and Engineering

Esat Kocaman

Pediatric Emergency Care

Michael Dean

2007 IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Signal Processing

Luis Moreno

Mark Borres

Revista Cubana de Salud Publica

LUIS ALIRIO LOPEZ GIRALDO

Nawaf Abu-Khalaf

Jurnal Fisioterapi dan Rehabilitasi

Linda Aprilia

Lo Stato dell'Arte 19

Mary Serraiocco

Jahrbuch Kirchliches Buch- und Bibliothekswesen

Georg Schrott

Medicina y Laboratorio

Maria Angelica Sotomayor

Florida Entomologist

Sebastião Lourenço Assis Júnior

mira jovanovska

Ecological Modelling

John Joseph

Eduardo Colina Navarrete

Suresh Tiwari

Amal Ilmiah : Jurnal Pengabdian Kepada Masyarakat

Desy Liliani Husain

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Exploring the impact of energy consumption on poverty in Pakistan: evidence from the asymmetric ARDL approach

- Research Article

- Published: 08 November 2023

- Volume 30 , pages 120250–120265, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Tahira Saddique 1 ,

- Ramsha Saleem 1 ,

- Assad Ullah ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5365-0224 2 &

- Azaz Ali Ather Bukhari 3

112 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

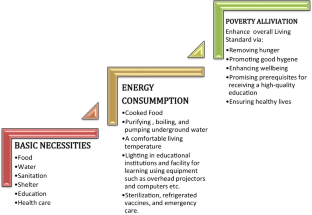

This research work contributes to the literature by examining the role of energy consumption in mitigating poverty via decomposing energy consumption into its positive and negative components, covering the period spanning from 1985 to 2017. To accomplish this objective, this study employs the nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) approach recently popularized by Shin et al., ( 2014 ). The NARDL approach is well-suited to our study becuase of its capability to delineate hidden asymmetries. The empirical findings reveal the prevalence of long-run associations among the studied variables. The outcomes show that an increase (decrease) in energy consumption combats (augments) poverty in Pakistan. The empirical findings underscore that the decreasing effect of energy consumption on poverty is found to be more promising than its increasing effect, both in the long and short run. Based on the empirical outcomes, we suggest that the policymakers, and other stakeholders should consider the asymmetric or nonlinear behavior of the studied variables for better poverty policy-making in Pakistan.

Graphical Abstract

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Analysis of environmental degradation mechanism in the nexus among energy consumption and poverty in Pakistan

How does energy poverty affect economic development? A panel data analysis of South Asian countries

Deciphering the moderation influence of economic policy uncertainty in the dynamics of energy poverty-government expenditure nexus in SSA

Data availability.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abdur Khorshed A (2010) Nexus between electricity generation and economic growth in Bangladesh. Asian Soc Sci 6(12):16–22

Google Scholar

Ali H, Sharif I (2020) Investment, Poverty and Growth Nexus in Pakistan: Empirical Evidence from ARDL Modeling Approach to Co-Integration. J Quant Methods 4(1):154–177

Article Google Scholar

Alam S (2010) Globalization, Poverty and environmental degradation: sustainable development in Pakistan. J Sustain Dev 3(3). https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v3n3p103

Alhassan AK, Okwanya I, Moses O (2015) Economic linkages between, energy consumption and poverty reduction: implication on sustainable development in Nigeria. Int J Innov Soc Sci Humanit Res 3(2):1131–1120

Ang JB (2007) CO 2 emissions, energy consumption, and output in France. Energy Policy 35(10):4772–4778

ADB (2010) Clean energy in Asia: case studies of ADB investments in low-growth. ADB, Manila

Antai AS, Udo AB, Ikpe IK (2015) A VAR analysis of the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth in Nigeria. J Econ Sustain Dev 6(12):1–12

Bazelian M, Yumkella K (2015) Why energy poverty is the real energy crises. World Economic Forum. Available at: http://www.weforum.org . Accessed 25 Dec 2022

Betto F, Garengo P, Lorenzoni A (2020) A new measure of Italian hidden energy poverty. Energy Policy 138:111237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2019.111237

Bildirici M, Türkmen NC (2015) Nonlinear causality between oil and precious metals. Resour Policy 46:202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2015.09.002

Black P (2003) Assessment for learning: putting it into practice. Open University Press, Buckingham, UK

Boukhatem J (2016) Assessing the direct effect of financial development on poverty reduction in a panel of low- and middle-income countries. Res Int Bus Financ 37:214–230

Dhaoui A, Chevallier J, Ma F (2020) Identifying asymmetric responses of sectoral equities to oil price shocks in a NARDL model. Stud Nonlinear Dyn Econom 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1515/snde-2019-0066

Dollar D, Kraay A (2001) Growth is good for the poor. J Econ Growth 7. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020139631000

Dubois U (2014) Energy consumption and poverty reduction in Africa. Afr J Sustain Dev 2(16). https://www.iaee.org/en/publications/proceedingsabstractpdf.aspx?id=12324

Farid A, Rehman N, Farid K (2016) Growing external debt in Pakistan and its implication for poverty. J Soc Sci Hum 1(1 & 2):55–71

Gillani YM, Rehman H, Gill RA (2009) Unemployment, poverty, inflation and crime nexus: co-integration and causality analysis of Pakistan. Pakistan Econ Soc Rev 47(1):79–98

Goozee H (2018) Energy, poverty and development: a primer for the sustainable development goals: Working Paper International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG), Brasilia

Harrison A (2006) Globalization and poverty. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper (No. w12347)

Holmberg S, Rothstein B, Nasiritousi N (2009) Quality of government: what you get. Annu Rev Polit Sci 12:135–161

Hosier RH, Dowd J (1987) Household fuel choice in Zimbabwe: an empirical test of the energy ladder hypothesis. Resour Energy 9:347–361

Hussein MA, Filho WL (2012) Analysis of energy as a precondition for improvement of living conditions and poverty reduction in Sub Saharan Africa. Sci Res Essays 7(30):2656–2666

Janvry AD, Sadoulet E (2016) Development economics: theory and practice. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, London

Kaidi N, Mensi S (2019) Financial development, income inequality, and poverty reduction: democratic versus autocratic countries. J Knowl Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-019-00606-3

Kakar KZ, Khilji AB, khan JM (2011) Globalization and economic growth: evidence from Pakistan. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Economica 7(3)

Karim KM, Zouhaier H, Adel BH (2013) Poverty, governance and economic growth. J Gov Regul 2(3):19–24

Kaygusuz K (2011) Energy services and energy poverty for sustainable rural development. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 15(2):936–947 (Elsevier)

Kheir VB (2018) The nexus between financial development and poverty reduction in Egypt. Rev Econ Political Sci. https://doi.org/10.1108/reps-07-2018-003

Khobai H (2020) Renewable energy consumption and unemployment in South Africa. Int J Energy Econ Policy

Kousar S, Ahmed F, Pervaiz A, Zafar M, Abbas S (2020) A panel co-integration analysis between energy consumption and poverty: new evidence from South Asian countries. Stud Appl Econ 38(3)

Kroon BVD, Brouwer R, Van Beukering PJH (2013) The energy ladder: theoretical myth or empirical truth? Results from a meta-analysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 20:504–513. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032112006594 . Accessed 12 Nov 2022

Kwon HJ, Kim E (2014) Poverty reduction and good governance: examining the rationale of the millennium development goals. Dev Chang 45(2):353–375

Leach G (1992) The energy transition. Energy Policy 20(2):116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-4215(92)90105-b

Legros G, Havet I, Bruce N, Bonjour S (2009) The energy access situation in developing countries: a review focusing on the least developed countries and Sub-Saharan Africa. World Health Organ 142:32–1

Majeed MT (2011) Trade, poverty and employment: empirical evidence from Pakistan. Forman J Econ Stud 2011(6):103–117

Masera OR (2000) From linear fuel switching to multiple cooking strategies: a critique and alternative to the energy ladder model. World Dev 28(12):2083–2103

Mogale TM (2005) Local governance and poverty reduction in South Africa (I). Prog Dev Stud 5(2):135–143

Moses OK, Okwanya I, Alhassan A (2015) Economic linkages between, energy consumption and poverty reduction: implication on sustainable development in Nigeria. Int J Innov Soc Sci Humanit Res 3(2):1131–1120

Murtaza G, Faridi MZ (2015) Causality linkages among energy poverty, income inequality, income poverty and growth: a system dynamic modelling approach. JSTOR 54(4):407–425

Nkomo J (2017) Energy use, poverty and development in the SADC. J Energy Southern Afr 18(3):10–17

Odhiambo NM (2010a) Is financial development a spur to poverty reduction? Kenya’s experience. J Econ Stud 37(3):343–353

Odhiambo NM (2010b) Finance-investment-growth nexus in South Africa: an ARDL-bounds testing procedure. Econ Change Restruct 2010(43):205–219

Okwanya I, Abah PO (2018) Impact of energy consumption on poverty reduction in Africa. CBN J Appl Stat 9(1):105–139

Paolo F, Enrico S (2006) Openness, economic reforms, and poverty: globalization in developing countries. J Dev Areas 39(2): 129–151. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4193008

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Economet 16(3):289–326

Qadir N, Majeed M (2018) Does trade openness cause marginalization in Pakistan? Pakistan Econ Rev (Summer 2018):30–51

Rana S (2016) Forty percent Pakistanis live in poverty. The express tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/1126706/40-pakistanis-live-poverty . Accessed 03 Dec 2022

Rahman ZU, Ahmad M (2019) Modeling the relationship between gross capital formation and CO 2 (a) symmetrically in the case of Pakistan: an empirical analysis through NARDL approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:8111–8124

Article CAS Google Scholar

Roddis S (2000) The role of women in the traditional energy sector: gender inclusion in an energy project. Africa Region Findings and Good Practice Infobriefs; No. 152. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9848

Sakanko MA, David J (2018) The relationship between poverty and energy use in Niger State. UMYUK J Econ Dev 1(3):139–154. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330713455 . Accessed 06 Nov 2022

Santos DS, Hino AAF, Höfelmann DA (2019) Iniquities in the built environment related to physical activity in public school neighborhoods in Curitiba, Paraná State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 35(5):e00110218. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311x00110218

Sarker AE, Rahman MH (2007) The emerging perspective of governance and poverty alleviation: a case of Bangladesh. Public Organiz Rev 7(2):93–112

Shin Y, Yu B, Greenwood-Nimmo M (2014) Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In W. Horrace, and R. Sickles (Eds.), The Festschrift in Honor of Peter Schmidt.: Econometric Methods and Applications (pp. 281–314). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-8008-39

Siddique H, Majeed M, Shehzadi I (2019) Impact of political instability on economic growth, poverty and income inequality. Pakistan Business Review 20:825–839

Saddique T, Saleem R, Ullah A, Amjad M (2022) The moderating role of PER capita income in energy consumption-poverty nexus: empirical evidence from Pakistan. 002190962211060. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096221106091

Sovacool BJ (2012) The political economy of energy poverty: a review of key challenges. Energy Sustain Dev 16(3):272–282

Tsaurai K (2021) Energy consumption-poverty reduction nexus in BRICS Nations. Int J Energy Econ Policy

Toda HY, Yamamoto T (1995) Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. J Econom 66(1–2):225250. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01616-8

Umair A, Abdul G, Awan DA (2019) Impact of globalization on poverty in Pakistan. 5:624-644

UNDP (2012) Energy to move rural Nepal out of poverty: the rural energy development programme model in Nepal. UNDP, Kathmandu. United Nations Development Program

United Nation Development Program (2007) Making globalization work for all. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/publications/undp-annual-report-2007

United Nations Development Programme (1954) Statistics of the human development report. UNDP 1954

WIN (2005) Household energy, indoor air pollution and health impacts: status report for Nepal. Kathmandu: Winrock International Nepal

World Bank (1985) Energy assessment status report: Nepal. World Bank, Washington, DC. (Report No. 028/84). The World Bank

World Bank (2015) Pakistan Country Profile. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available at http://Data.Worldbank.Org/Country/Pakistan . Accessed 02 Oct 2022

World Bank (2003) Energy and poverty reduction: proceedings from a multi-sector and multi-stakeholder workshop - how can modern energy services contribute to poverty reduction? World Bank, Washington, DC

World Bank (2018) The World Bank Annual Report Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30326 . Accessed 3 Oct 2022

World Health Organization (2006) The world health report working together for health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf . Accessed 10 Oct 2022

Yasmin B, Jehan Z, Chaudhary MA (2006) Trade liberalization and economic development: evidence from Pakistan. Lahore J Econ 11(1)

Yousaf H, Ali I (2014) Determinants of poverty in Pakistan. Int J Econ Empir Res (IJEER) 2(5):191–202

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Lahore College for Women University, Lahore, Pakistan

Tahira Saddique & Ramsha Saleem

School of Economics and Management, Hainan Normal University, Haikou, China

Assad Ullah

Department of Economics, University of Narowal, Narowal, Punjab, Pakistan

Azaz Ali Ather Bukhari

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

TS conceived the idea, wrote original draft, and finished formal analysis. RS supervised the article and contributed towards conceptual and computational part of the study. AU and AAAB revised the literature review section and verified the methodology. All authors discussed the results and reviewed and finalized the draft.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Assad Ullah .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval.

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Roula Inglesi-Lotz

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Saddique, T., Saleem, R., Ullah, A. et al. Exploring the impact of energy consumption on poverty in Pakistan: evidence from the asymmetric ARDL approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 30 , 120250–120265 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30494-9

Download citation

Received : 04 January 2023

Accepted : 11 October 2023

Published : 08 November 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-30494-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Energy consumption

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2024

Implementation of a clinical breast exam and referral program in a rural district of Pakistan

- Russell Seth Martins 1 ,

- Aiman Arif 2 na1 na2 ,

- Sahar Yameen 2 ,

- Shanila Noordin 2 ,

- Taleaa Masroor 3 ,

- Shah Muhammad 2 ,

- Mukhtiar Channa 2 ,

- Sajid Bashir Soofi 2 &

- Abida K. Sattar 2 , 4

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 616 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

31 Accesses

Metrics details

The role of clinical breast examination (CBE) for early detection of breast cancer is extremely important in lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) where access to breast imaging is limited. Our study aimed to describe the outcomes of a community outreach breast education, home CBE and referral program for early recognition of breast abnormalities and improvement of breast cancer awareness in a rural district of Pakistan.

Eight health care workers (HCW) and a gynecologist were educated on basic breast cancer knowledge and trained to create breast cancer awareness and conduct CBE in the community. They were then deployed in the Dadu district of Pakistan where they carried out home visits to perform CBE in the community. Breast cancer awareness was assessed in the community using a standardized questionnaire and standard educational intervention was performed. Clinically detectable breast lesions were identified during home CBE and women were referred to the study gynecologist to confirm the presence of clinical abnormalities. Those confirmed to have clinical abnormalities were referred for imaging. Follow-up home visits were carried out to assess reasons for non-compliance in patients who did not follow-through with the gynecologist appointment or prescribed imaging and re-enforce the need for follow-up.

Basic breast cancer knowledge of HCWs and study gynecologist improved post-intervention. HCWs conducted home CBE in 8757 women. Of these, 149 were warranted a CBE by a physician (to avoid missing an abnormality), while 20 were found to have a definitive lump by HCWs, all were referred to the study gynecologist (CBE checkpoint). Only 50% (10/20) of those with a suspected lump complied with the referral to the gynecologist, where 90% concordance was found between their CBEs. Follow-up home visits were conducted in 119/169 non-compliant patients. Major reasons for non-compliance were a lack of understanding of the risks and financial constraints. A significant improvement was observed in the community’s breast cancer knowledge at the follow-up visits using the standardized post-test.

Conclusions

Basic and focused education of HCWs can increase their knowledge and dispel myths. Hand-on structured training can enable HCWs to perform CBE. Community awareness is essential for patient compliance and for early-detection, diagnosis, and treatment.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy (barring skin cancers) and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [ 1 , 2 ]. According to GLOBOCAN 2022, 2.3 million new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022, with 666,103 patients dying from the disease [ 3 ]. Moreover, the incidence and mortality of breast cancer is expected to increase by 40% and 50% respectively by 2040 [ 3 ]. The rise in incidence is particularly steep in Asia, with these countries also seeing a significantly younger age of onset compared to the Western world [ 4 , 5 ]. In Pakistan, one in every nine women suffers from breast cancer, with the country having one of the highest incidence rates in the region (around 2.5 times higher than neighboring countries such as Iran and India) [ 6 , 7 ]. Breast cancer accounts for more than 20% of all malignancies in Pakistan, and almost half of all cancers in women [ 8 ].

The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasized the role of early diagnosis of symptomatic breast cancer as a more feasible and economical strategy as compared to screening in resource-constrained countries [ 9 , 10 ]. Screening for breast cancer allows for detection of breast cancer at an earlier stage (especially when small enough to remain undetectable on clinical examination) and leads to significantly better management outcomes and less treatment expenditure [ 1 , 9 ]. While screening aims to identify lesions in asymptomatic and healthy individuals who have yet to develop clinical manifestations of disease, early detection of symptomatic breast cancer seeks to recognize individuals at an earlier stage than when they would otherwise present, allowing for more timely management and potentially better oncologic outcomes [ 9 ].

Early diagnosis and treatment are a cornerstone of efforts to reduce cancer-associated mortality in developed countries. In the United States (US), fewer than 20% of cancers present with advanced disease [ 11 ]. Data from Pakistan presents a stark contrast, with more than half of patients presenting with locally advanced or metastatic disease [ 11 ]. Mammography is the most effective screening modality for breast cancer in high-income countries. Multiple breast cancer screening trials have reported a reduction breast cancer-related mortality up to 25% among women undergoing mammography screening [ 12 ]. However, it remains under-utilized as a screening tool, both in developing and developed countries. Reasons for this range from misconceptions regarding screening methods, techniques, and radiation to lack of insurance or a care provider and fear of recall imaging, overdiagnosis leading to unnecessary biopsies and treatment and side effects [ 13 , 14 ]. In the US, more than 75% of eligible women are screened for breast cancer via mammography [ 15 ]. In a lower-middle-income country (LMIC) like Pakistan, access to investigations such as mammogram, breast ultrasound and needle biopsy is limited due to lack of availability of machines and trained personnel, lack of awareness and financial limitations (75% of healthcare financing in Pakistan is out-of-pocket and over one-third of the population lives below the poverty line) [ 16 , 17 ]. In addition, conservative sociocultural norms and religious factors also prevent women from seeking routine healthcare [ 18 ]. Given the lack of healthcare access coupled with a largely conservative culture, community outreach programs with home visits may be the ideal system for bringing initial breast cancer recognition home to the rural communities, enabling early confirmation of disease and initiation of treatment. Similar outreach programs have met with considerable success in other aspects of healthcare. These include programs improving screening and prevention of malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV and those targeting improvement maternal and neonatal mortality [ 19 , 20 ]. Thus, screening, and early detection interventions implemented in LMICs like Pakistan must take into account the local healthcare systems and social structures.

Clinical breast examination (CBE) is recommended as the preferred approach for early detection of symptomatic and clinically detectable breast cancer in LMICs such as Pakistan. It consists of inspection and palpation of the breasts and regional (axillary, supraclavicular, infraclavicular and cervical) lymph nodes of the patient in a sitting and supine position [ 21 ]. It can be readily performed by a primary care physician to identify abnormal breast findings and determine the need for further evaluation.[ 22 ], [ 23 ] In fact, while mammography is expected to miss over 20% of breast cancers, CBE is able to detect 3–45% of these false negative cases [ 24 , 25 , 26 ].

Due to the aforementioned sociocultural barriers towards mammographic breast screening in Pakistan, it is vital that early detection interventions employ more feasible methods such as CBE. Thus, the objective of this study was to describe the outcomes of a community outreach breast education, home CBE and referral program for early recognition of breast abnormalities and improvement of breast cancer awareness in a rural district of Pakistan. We conducted a community outreach and referral program where home CBE visits were conducted by trained healthcare workers (HCWs) for early detection of breast signs and symptoms, in a rural district of Pakistan. Women who had clinical abnormalities detected upon examination were then referred for further evaluation. During these visits, the women were also educated regarding breast cancer management. In this study, we report our results and experiences with this program. We believe that it is important to reinforce that early detection interventions for breast cancer may be implemented in LMICs like Pakistan using CBE as the preferred approach. Given that most patients with breast cancer present with advanced disease, CBE may be able to identify characteristic breast changes earlier and allow for timely treatment of the tumor at earlier stages [ 27 ].

Materials and methods

Study design and setting.

A quasi-experimental study was carried out over September 2021 - September 2022 in Sindh, Pakistan. The study team was primarily based at Aga Khan University (AKU) in Karachi, Sindh, while the field location where the community outreach program was implemented was situated in the Dadu district of Sindh, Pakistan. The Aga Khan University is an academic tertiary care private hospital and a health services agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN) in Pakistan. This study featured a collaboration between the Departments of Surgery and Maternal and Child Health at AKU. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical review committee at AKU.

The Dadu district covers 19,070 km 2 in interior Sindh and is divided into four sub-divisions which are further divided into Union Councils (UC). The UC is the smallest administrative unit of Pakistan. The field location of our study consisted of five UCs within the Johi subdivision of the Dadu district. Some census data of the five included UCs, as collected by the AKU for local projects, are shown in Table 1 . Approximately 48.7% of the population is female. As of 2021, it has 47 Basic Health Units (BHU) and 5 Rural Health Centers (RHC) with a total of 503 beds (BHUs and RHCs are first-level primary healthcare facilities that serve rural populations). The doctor -to-patient ratio is 1:6,030, nurse-to-patient ratio is 1:39,629, and bed-to-patient ratio is 1:3,309 [ 28 ].

Study population and sample size calculation

The total population within the five target UCs was 64,023. Our target sub-population consisted of all adult women ≥ 18 years of age. Using an estimated 20% prevalence of abnormal CBE according to a similar study conducted in Tajikistan [ 29 ], 80% power, 95% confidence level, and design effect of 2, we calculated the minimum required sample size to be 547 individuals. This was inflated by 100% to mitigate against extreme rates of individuals being lost to follow-up, which we anticipated to be a significant real-world challenge, yielding a final minimum required sample size of 1,094. Cluster convenience sampling was used to identify women in the community.

Training workshop and outreach program

The study schema consisted of the following interventions in sequence as described:

Training of Health Care Workers (HCWs) : Non-physician HCWs received training at AKU, Karachi in September – October 2021. This specialized training program was designed to enhance HCWs’ skills in identifying suspicious breast problems, making appropriate and timely referrals, and improving general knowledge regarding breast cancer. This training was conducted and overseen by an attending breast surgeon at AKU. HCWs were taught how to perform clinical breast examinations (CBEs) and engaged in hands-on practice sessions with simulated breast disease models and real patients in clinics. In addition, the HCWs were educated regarding general knowledge regarding breast cancer, with special emphasis on treatment, evaluation and commonly held misconceptions among the public. Pre and post-intervention surveys were administered to evaluate improvement in knowledge.

Community outreach program with home visits : The HCWs were deployed into the community in the Johi subdivision in October 2021. The initial series of home visits took place between October 2021 to February 2022, with the HCWs performing home visits in groups of two. Each visit began with an introductory and informed consent-seeking debriefing, followed by CBE of all consenting adult women belonging to a household, an assessment of baseline breast cancer-related knowledge, and lastly, a brief, standardized educational intervention delivered verbally (Supplement). For each CBE performed, a checklist of examination findings was completed. In the event of any abnormal finding, a referral to a local gynecologist within Johi was made. All interactions during the home visits were conducted in the Sindhi language, which is the native language of the region.

Visit to the local gynecologist : Patients who complied with their referral (for a palpable breast concern) were evaluated by a gynecologist at the local District Health Quarter. The gynecologist repeated a CBE on all referred patients in order to validate the HCWs’ examination findings. All eligible patients were then referred for breast imaging, either mammography or ultrasound, to the nearest facility within Johi.

Follow-up home visits : The HCWs attempted to conduct follow-up home visits for all women who were non-compliant with initial referral to a gynecologist. These follow-up visits took place six months after the initial series of home visits. Patients were questioned as to the reasons for their non-compliance with referral using a self-designed structured questionnaire (Supplement: Sect. 4 ). In addition, the breast cancer-related knowledge survey was re-administered to the women to gauge improvement in knowledge since the educational intervention delivered at the initial home visits. Finally, the importance of complying with referral for future evaluation, diagnosis and management was re-emphasized to all patients.

Validation of Data Collection Tools :

CBE checklist : This was a self-designed checklist (Supplement: Sect. 3 ) that included all the important components of a CBE, including a brief history of relevant symptoms (pain, discharge), breast inspection (skin changes, or changes in breast size, shape, or symmetry, and nipple changes), and breast palpation (presence of lumps in the axilla or breast).

Breast cancer-related knowledge survey : Separate surveys were administered to the HCWs and the women within the general community (Supplement: Sects. 2 and 3 ). Both surveys were designed by faculty within the Section of Breast Surgery at AKU. Prior to its use, the survey for women within the community was pretested amongst 30 local women for content, comprehensibility, and language. Minor adjustments were made on the basis of this pilot procedure.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York). Descriptive analysis was performed whereby categorical values were reported using frequencies and percentages. McNemar’s test was used to compare changes in knowledge across the multiple administrations of the breast cancer-related knowledge surveys. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant for all the analysis.

Education and training of the HCWs

A total of 8 HCWs were trained. Tables 2 and 3 show the changes in breast cancer-related knowledge after the educational and training intervention for the HCWs. The absolute percentage increase in HCWs who correctly believed that breast cancer can occur in men, and in women despite breast feeding their children, was 50%. In addition, the percentage of respondents who believed that women with a painless lump should visit a healthcare professional increased from 87.5 to 100%. The absolute percentage of HCWs who correctly identified painless lump and bloody nipple discharge as a symptom suspicious of breast cancer increased by 12.5% and those that identified dimpling of skin as a suspicious symptom increased by 25%. The percentage of HCWs who correctly believed that a tissue biopsy could be used to diagnose breast cancer increased from 62.5 to 87.5%.

Implementation of the outreach program

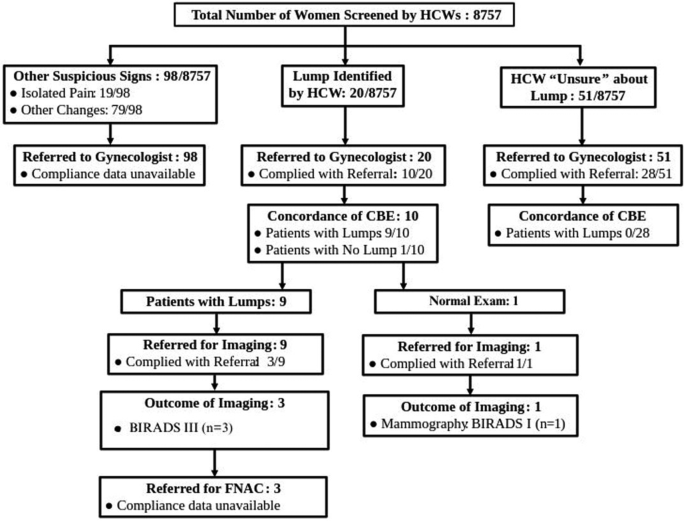

A total of 8,757 women were screened by the HCWs in the field during initial series of home visits. A palpable breast lump was identified in 20/8,757 women, while other palpable or visible breast concerns warranting further evaluation were identified in 98/8,757 women. In addition, HCWs were unsure about the presence of a lump in 51/8,757 women. Keeping a low threshold for seeking a physician’s evaluation and prompt referrals, these 169/8,757 patients were all referred to a gynecologist for further examination. However, only 38/169 patients (ten with a palpable breast lump and 28 for which the HCWs exercised caution-either noted other breast concerns or were unsure) complied with initial referral to the gynecologist. Out of the 28 patients (where HCWs noted breast concerns or were unsure about a lump), none were found to have a lump on the gynecologist’s CBE examination. Out of the ten patients in which the HCWs had positively identified the breast lumps, nine patients (90% concordance) were confirmed to have a breast lump on the gynecologist’s CBE. However, all these ten patients were referred for imaging with only 4 of them complying. Amongst these 4 patients who had breast imaging, one patient had BI-RADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) category I finding (i.e. negative imaging) and 3 patients had BI-RADS category III findings (Lump with extremely low probability of malignancy). The outcomes of the CBE and referral program are illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Outcomes of community outreach Breast referral program. HCW: Health Care Workers; CBE: Clinical Breast Examination; FNAC: Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology

At the follow-up home visits to the 131 patients who had been non-compliant with initial referral, the most common reasons for non-compliance were assessed by the HCWs ( Table 4 ). The most common reasons for non-compliance were a belief that follow-up was not important (42.0%), lack of money to visit the gynecologist (24.4%), not having anyone to accompany them (9.2%), long distance to travel for the appointment (7.6%).

Increase in community awareness regarding breast cancer

A comparison of the women’s knowledge regarding breast cancer at the time of initial visit and later at follow-up is shown in Table 5 . The percentage of women who had heard of breast cancer increased from 54.6 to 100%, the percentage of women who were aware that breast cancer was treatable increased from 32.8 to 61.3%. The percentage of women understood the need to consult a healthcare professional upon finding a lump increased from 50.4 to 94.1%.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of the real-world implementation of a large-scale clinical breast examination and referral community outreach program in a rural district of Pakistan. Secondarily, we also explored the feasibility of delivering basic breast cancer-related knowledge to the community via non-physician HCWs. This program was the first of its kind for breast cancer detection in the country. The key positive takeaways from our experience were that it is: (i) possible to train non-physician HCWs to perform a comprehensive CBE and identify examination findings warranting referral and further evaluation, (ii) practically feasible to implement a large-scale community outreach program with home-visits for mass detection of breast cancer, (iii) possible to increase community knowledge and awareness for breast cancer by imparting education at the home-visits when CBE was performed. However, we encountered several real-world challenges that precluded the full realization of this outreach program’s impact. Only 50% of women initially identified by the HCWs as having a breast lump followed through with referral to the gynecologist, and only 40% of women followed up with subsequent referral for imaging. None of the patients eventually referred for histopathological evaluation ended up complying with the referral. However, prior experience with a similar program by the AKDN in Tajikistan demonstrated that with appropriate follow-ups, breast cancer may be detected in up to 0.2% of the women in the community [ 29 ]. Although this rate is slightly lower than the reported incidences of mammographic screening-detected breast cancers in the literature (0.5–0.8%), it underscores the potential for success of CBE-based programs as an early detection strategy in low-resource communities [ 30 , 31 ].

Accuracy of CBE by non-physician HCWs and effectiveness of educational interventions

Overall, the theoretical frameworks and foundations of this large-scale clinical breast examination and referral community outreach program were observed to be largely successful. We were able to achieve a high degree of concordance (90%) between the CBE findings of the HCWs and the gynecologist, indicating that it is possible and feasible to leverage HCWs for the early detection of symptomatic breast cancer. Another study carried out in Malawi to train community laywomen to conduct CBE in the community showed 88% concordance between CBE performed by the HCWs and those performed by the physicians [ 32 ]. This is exceedingly important in a LMIC like Pakistan, where the ratio of physicians to population is a major impediment to healthcare access. In Pakistan, there are only 170,000 general practitioners to serve a population of over 230 million individuals. Thus, a major bottleneck for the delivery of high quality breast cancer-related healthcare is the timely initial identification of these patients from the community. Utilizing existing community outreach frameworks, such as the Lady Health Worker (LHW) Program, cite which was in Pakistan in 1994 [ 33 , 34 ]. While the LHW Program was initially developed for promoting family planning and maternal health, the model has been adapted for other major public health interventions such as immunizations and basic preventative healthcare. These LHWs are salaried and recognized as part of the healthcare workforce. Since LHWs are recruited from within the community itself, one of the major strengths of such a program is their ability to deliver culturally appropriate healthcare to populations with limited access to healthcare facilities. Thus, based on the successful training of HCWs in our study, we believe that the LHW Program model can be effectively adapted for the early recognition of breast abnormalities in women who would otherwise go undetected. However, it is important to know that the training of the HCWs in our study was performed by a fellowship-trained breast surgeon at a tertiary care hospital in one of the major cities of Pakistan. To ensure the feasibility, uptake, and growth of our model throughout the underserved regions of the country, it is important that a certain degree of sustainability is achieved. In future iterations of this model, we plan to assess the effectiveness of cascade learning with peer-to-peer teaching. In such a model, HCWs initially trained by a breast surgeon will subsequently assume the role of trainers themselves and teach other HCWs/LHWs how to perform a CBE. Interestingly, the study conducted in Malawi trained non-HCWs to serve as “Breast Health Workers”, highlighting the potential to leverage non-HCW professionals to perform a health-related role in communities with low HCW-to-patient ratios [ 32 ].

Community education and awareness

Despite the successful and rigorous implementation of the CBE and referral community outreach program, the Achilles’ heel of this project was the pervasive lack of community awareness regarding the importance of following up with referrals. This was compounded by other sociocultural barriers such as financial constraints, transportation issues, and a lack of family support to visit the healthcare facility. Thus, it is important that future iterations of similar public health interventions be cognizant of these challenges and seek to mitigate them to the best of their ability. Indeed, the most modifiable of these obstacles is the lack of awareness which can be countered by greater community education during home visits, with a particular focus on emphasizing the potential consequences of non-compliance with diagnostic evaluations. Our results demonstrated the feasibility of educating HCWs to subsequently serve as teachers for the community, and that the newly gained knowledge remained reasonably intact even at a follow-up of six months. A study in Vietnam showed that repeated breast cancer-related educational interventions were successful in increasing compliance with referrals for breast cancer evaluation. [ 35 ] In addition, a more robust follow-up system including frequent interaction and monitoring of patients could help boost compliance with referrals and better continuity of care. For example, routinely scheduled phone calls could be made to the patient as a reminder to follow-up with their referrals. Moreover, for women who are not able to comply with their referrals because of the absence of a family member to accompany them, arrangements may be made whereby LHWs could accompany them as their attendants.

The other challenges, however, harken to well-known and longstanding problems with the healthcare system in Pakistan, where most of the population is unable to afford even basic healthcare. In such a setting, Universal Healthcare Coverage (UHC) emerges as the only viable solution to the masses. An attempt at such a system, the Sehat Sahulat Program (SSP; translates to Health Facility Program) was introduced in 2016 by the provincial government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, one of the five provinces of Pakistan [ 36 ]. The SSP was designed to cover a broad range of health conditions and services, including breast cancer diagnosis and evaluation. While the program was met with success in its initial years, and even expanded into some of the other provinces, instability in the political and economic infrastructures of Pakistan have limited its growth, uptake, and effectiveness. Ideally, mass community interventions for early breast cancer detection such as ours could be integrated with UHC programs such as SSP to ensure patient compliance, continuity of care, and maximization of invested resources most effectively.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that we would like to acknowledge. Firstly, we were unable to calculate a study participation rate as the HCWs did not record the number of informed refusals that they received from women in the community. Secondly, as mentioned earlier, compliance with referrals was exceedingly poor and limited the realization of the true impact of the program. Thirdly, given the limited number of HCWs included, we were unable to perform statistical comparisons to evaluate the improvement in HCWs knowledge. Lastly, the evaluation of the long-term impact and sustainability of the program was limited, presumably due to the influence of sociocultural barriers on the health-seeking behaviors of the women.

This study describes the real-world implementation of a large-scale clinical breast examination and referral community outreach program in a rural district of Pakistan. Our study highlights the importance of CBE programs in early recognition of breast abnormalities/lumps, in regions where mammography is not feasible. Such training programs may lay the foundation for improved provider and community awareness, and examination at the patient’s doorstep and initiate referrals. However, for such programs to ultimately lead to earlier detection of breast cancer/downstaging of disease, community awareness and political buy-in from governmental stakeholders would be critical. Lastly, for such a program to have a truly national impact and be sustainable, more widespread training of HCWs using cascade learning and peer-to-peer teaching models would be necessary.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available since the Ethical Review Committee guidelines does not allow institutional data to be dispersed. However, the data is available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

Global Cancer Observatory

United States

Lower-Middle-Income Country

World Health Organization

Clinical Breast Examination

Aga Khan University

Union Council

Healthcare Workers

Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System

Lady Health Worker

Universal Health Coverage

Wilkinson L, Gathani T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1130):20211033.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

2022 G. Cancer Today: World Health Organization; 2022 https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/en/dataviz/tables?mode=population&cancers=20&types=1

Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, et al. Current and future burden of breast cancer: global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 2022;66:15–23.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ali A, Manzoor MF, Ahmad N, Aadil RM, Qin H, Siddique R, et al. The Burden of Cancer, Government Strategic policies, and challenges in Pakistan: a Comprehensive Review. Front Nutr. 2022;9:940514.

Lin CH, Chuang PY, Chiang CJ, Lu YS, Cheng AL, Kuo WH, et al. Distinct clinicopathological features and prognosis of emerging young-female breast cancer in an east Asian country: a nationwide cancer registry-based study. Oncologist. 2014;19(6):583–91.

Moore MA, Ariyaratne Y, Badar F, Bhurgri Y, Datta K, Mathew A, et al. Cancer epidemiology in South Asia - Past, present and future. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(Suppl 2):49–66.

PubMed Google Scholar

Raza S, Sajun SZ, Selhorst CC. Breast Cancer in Pakistan: identifying local beliefs and knowledge. J Am Coll Radiol. 2012;9(8):571–7.

Badar F, Faruqui ZS, Uddin N, Trevan EA. Management of breast lesions by breast physicians in a heavily populated South Asian developing country. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(3):827–32.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Management-Screening NCD. D.a.T. Guide to cancer early diagnosis 2017 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guide-to-cancer-early-diagnosis . [Accessed June 20, 2023].

Organisation. W.H. WHO position paper on mammography screening. 2014.

Zeeshan S, Ali B, Ahmad K, Chagpar AB, Sattar AK. Clinicopathological features of Young Versus older patients with breast Cancer at a single Pakistani Institution and a comparison with a National US database. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–6.

Løberg M, Lousdal ML, Bretthauer M, Kalager M. Benefits and harms of mammography screening. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):63.

Jones TP, Katapodi MC, Lockhart JS. Factors influencing breast cancer screening and risk assessment among young African American women: an integrative review of the literature. J Am Association Nurse Practitioners. 2015;27(9):521–9.

Article Google Scholar

Mascara M, Constantinou C. Global perceptions of women on breast Cancer and barriers to Screening. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23(7):74.

Services, U.S.D.o.H.a.H. Increase the proportion of females who get screened for breast cancer 2021 https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/cancer/increase-proportion-females-who-get-screened-breast-cancer-c-05/data . [Accessed 28-06-2023].

Bank W. Out-of-Pocket Expenditure (% of current health expenditure) - Pakistan 2023 https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS . [Accessed 28-06-2023].

Bank W. Poverty & Equity Brief Pakistan. 2023 April 2023.

Gutnik LA, Matanje-Mwagomba B, Msosa V, Mzumara S, Khondowe B, Moses A, et al. Breast Cancer screening in low- and Middle-Income countries: a perspective from Malawi. J Glob Oncol. 2016;2(1):4–8.

Metwally AM, Abdel-Latif GA, Mohsen A, El Etreby L, Elmosalami DM, Saleh RM, et al. Strengths of community and health facilities based interventions in improving women and adolescents’ care seeking behaviors as approaches for reducing maternal mortality and improving birth outcome among low income communities of Egypt. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):592.

Moh DR, Bangali M, Coffie P, Badjé A, Paul AA, Msellati P. Community Health Workers. Reinforcement of an Outreach Strategy in Rural areas aimed at improving the integration of HIV, Tuberculosis and Malaria Prevention, Screening and Care into the Health Systems. Proxy-Santé Study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:801762.

Lynn S, Bickley PGS, Richard M, Hoffman, Rainier P. Soriano. Bates’ Guide to physical examination and history taking Thirteenth Edition. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2024.

Google Scholar

Kearney AJ, Murray M. Breast Cancer screening recommendations: is Mammography the only answer? J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2009;54(5):393–400.

McDonald S, Saslow D, Alciati MH. Performance and reporting of clinical breast examination: a review of the literature. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(6):345–61.

Barton MB, Harris R, Fletcher SW. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have breast cancer? The screening clinical breast examination: should it be done? How? Jama. 1999;282(13):1270–80.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Klein S. Evaluation of palpable breast masses. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(9):1731–8.

Cady B, Steele GD Jr., Morrow M, Gardner B, Smith BL, Lee NC, et al. Evaluation of common breast problems: guidance for primary care providers. CA Cancer J Clin. 1998;48(1):49–63.

Miller AB, Baines CJ. The role of clinical breast examination and breast self-examination. Prev Med. 2011;53(3):118–20.

Bureau Of Statistics Pdd. Government of Sindh. Health Profile Of Sindh; 2021.

Buribekova R, Shukurbekova I, Ilnazarova S, Jamshevov N, Sadonshoeva G, Sayani S, et al. Promoting clinical breast evaluations in a Lower Middle-Income Country setting: an Approach toward achieving a sustainable breast Health Program. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–8.

Grabler P, Sighoko D, Wang L, Allgood K, Ansell D. Recall and Cancer Detection Rates for Screening Mammography: finding the Sweet Spot. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208(1):208–13.

Service NCRaA. Screen-Detected Breast Cancer 2009 [ http://www.ncin.org.uk/publications/data_briefings/screen_detected_breast_cancer#:~:text=17%2C045%20cancers%20were%20detected%20 .

Gutnik L, Moses A, Stanley C, Tembo T, Lee C, Gopal S. From community laywomen to breast Health workers: a pilot training model to implement clinical breast exam screening in Malawi. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0151389.

Hafeez A, Mohamud BK, Shiekh MR, Shah SA, Jooma R. Lady health workers programme in Pakistan: challenges, achievements and the way forward. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(3):210–5.

Jalal S. The lady health worker program in Pakistan—a commentary. Eur J Pub Health. 2011;21(2):143–4.

Ngan TT, Jenkins C, Minh HV, Donnelly M, O’Neill C. Breast cancer screening practices among Vietnamese women and factors associated with clinical breast examination uptake. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(5):e0269228.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Forman R, Ambreen F, Shah SSA, Mossialos E, Nasir K. Sehat sahulat: a social health justice policy leaving no one behind. Lancet Reg Health - Southeast Asia. 2022;7.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Russell Seth Martins and Aiman Arif contributed equally to this work.

Sahar Yameen and Shanila Noordin contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Division of Thoracic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, Hackensack Meridian Health Network, Nutley, NJ, 08820, USA

Russell Seth Martins

Aga Khan University, Karachi, 74800, Pakistan

Aiman Arif, Sahar Yameen, Shanila Noordin, Shah Muhammad, Mukhtiar Channa, Sajid Bashir Soofi & Abida K. Sattar

Department of Surgery, John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, 21218, USA

Taleaa Masroor

Department of Surgery, Link Building The Aga Khan University, Karachi, 74800, Pakistan

Abida K. Sattar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AKS was responsible for study conceptualization, design of the study. Project administration was overseen by AKS and SBS. Development of the curriculum and training of healthcare workers was conducted by AKS. Implementation of the study protocols and the acquisition of data was performed by SY, SN, SM, and MC. TM and RSM were responsible for formal analysis and data curation. AA was responsible for writing the original draft of the manuscript. Critical review and editing of the manuscript were conducted by RSM, AKS and AA. SM and MC were responsible for the supervision of the project on the field and AKS and SBS were responsible for the supervision of the entire project. AKS was involved in all aspects from conception and design, through implementation, monitoring, internal audits, study coordination, data analysis, manuscript concept, and critical review. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Abida K. Sattar .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Committee at Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi. Informed consent was taken from all study participants after debriefing them regarding the study. The reference number for the study was 2020-2047-14276.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was taken from all study participants as part of the informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Martins, R.S., Arif, A., Yameen, S. et al. Implementation of a clinical breast exam and referral program in a rural district of Pakistan. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 616 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11051-7

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2024

Accepted : 26 April 2024

Published : 10 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11051-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breast cancer

- Clinical breast exam

- Healthcare workers

- Community outreach program

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2024

Diabetes, life course and childhood socioeconomic conditions: an empirical assessment for Mexico

- Marina Gonzalez-Samano 1 &

- Hector J. Villarreal 1

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1274 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

158 Accesses

9 Altmetric

Metrics details

Demographic and epidemiological dynamics characterized by lower fertility rates and longer life expectancy, as well as higher prevalence of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, represent important challenges for policy makers around the World. We investigate the risk factors that influence the diagnosis of diabetes in the Mexican population aged 50 years and over, including childhood poverty.

This work employs a probabilistic regression model with information from the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) of 2012 and 2018. Our results are consistent with the existing literature and should raise strong concerns. The findings suggest that risk factors that favor the diagnosis of diabetes in adulthood are: age, family antecedents of diabetes, obesity, and socioeconomic conditions during both adulthood and childhood.

Conclusions

Poverty conditions before the age 10, with inter-temporal poverty implications, are associated with a higher probability of being diagnosed with diabetes when older and pose extraordinary policy challenges.

Peer Review reports

One of the major public health concerns worldwide is the negative consequences that the demographic (with its epidemiological) transition could bring. This demographic transition is driven by increasing levels of life expectancy (caused by technological innovation and scientific breakthroughs in many cases) and decreasing fertility rates. While during the 20th century, the main health concerns were related to infectious and parasitic diseases, at the present time, non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as diabetes, constitute a harsh burden in terms of economic and social impact. NCDs most commonly affect the health of adults and the elderly. The economic and social costs associated with NCDs increase sharply with age. These patterns have implications for economic growth, poverty-reduction efforts and social welfare [ 1 ].

Mexico’s demographic trends are reflecting a significant shift over the past decades, much like those observed globally. In 1950, the fertility rate stood at 6.7 children per woman, and the proportion of the population aged 60 or over was about 2%. Since the 1970s, there has been a considerable decrease in fertility rates; by 2017, it had dropped to 2.2 children per woman [ 2 ]. Even more pressing, according to CONAPO Mexico had a total fertility rate of 1.91 during 2023 [ 3 ]. Alongside the declining fertility, the aging population is becoming a more prominent feature in Mexico’s demographic profile. In 2017, individuals aged 60 and over constituted around 10% of the population. Forecasts for 2050 project that this figure will more than double, with those 60 and over representing 25% of the total population. These trends suggest substantial changes in Mexico’s population structure, with implications for policy-making in areas such as healthcare, pensions, and workforce development [ 2 ].

Regarding NCDs, in 2017 13% of the Mexican adult population suffered from diabetes, which is twice the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average and it is also the highest rate among its members. Some of the risk factors associated with this disease are being overweight or obese, unhealthy diets and sedentary lifestyles. In 2017 72.5% of the Mexican population was overweight or obese [ 4 ] and the country had the highest OECD rate of hospital admissions for diabetes. During the period of 2012 to 2017, the number of hospital admissions for amputations related to this condition, increased by more than 10%, which suggests a deterioration in quality and control of diabetes treatments [ 4 ]. Moreover, it is estimated that diabetes prevalence will continue with its upward trend; forecasts anticipate that in 2030 there will be around 17.2 million people in Mexico with this condition [ 5 ].

Despite the increasing proportion of older people, most of the research regarding the effects of socioeconomic conditions on health focuses on economically active populations. Those which do consider older people, do not investigate length factors such as childhood conditions [ 6 , 7 ]. In this sense, the Social Determinants of Health (SDH) throughout the Life Course approach provide a framework to ponder and direct the design of public policies on population aging and health [ 8 , 9 ]. They focus on well-being and the quality of life of populations from a multi-factorial perspective [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

In this study, we explore the impact of childhood and adulthood conditions and other demographic and health aspects on diabetes among older people. The literature has proposed several mechanisms through which the mentioned drivers could operate. In general, these approaches imply that satisfactory socioeconomic outcomes for adults may relatively atone for poor socioeconomic conditions in early childhood [ 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Poverty conditions during the first years of life have critical implications, and yet children are twice as likely to live in poverty as adults [ 16 , 17 ]. On the other hand, poverty is known to be closely linked to NCDs such as diabetes. According to [ 13 ], NCDs are expected to obstruct poverty reduction efforts in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) by increasing costs associated with health care. Moreover, the costs resulting from NCDs such as diabetes could deplete household incomes rapidly and impulse millions of people into poverty [ 16 ].

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has highlighted the consequences of what it describes as the “invisible epidemic”: non-communicable diseases. NCDs are the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 71% or 41 million of the annual deaths globally. The majority (85%) of NCD deaths among people under 70 years of age occur in low and middle-income countries [ 17 ].

According the World Health Organization (WHO), SDH are non-medical factors that influence health outcomes, such as the circumstances in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the broader set of forces and systems that shape the conditions of daily life Footnote 1 .

These forces include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms and policies, and political systems [ 11 , 18 ]. In this regard, SDH have an important influence on health inequities in countries of all income levels. Health and disease follow a social gradient, that is, the lower the socioeconomic status, a lesser health is expected [ 11 , 18 ].

On the other hand, the Life Course perspective distinguishes the opportunity to inhibit and control illnesses at key phases of life from preconception to pregnancy, infancy, childhood, adolescence, and through adulthood. This does not follow the health model where an individual is healthy until disease occurs, the trajectory is determined earlier in life. Evidence suggests that age related mortality and morbidity can be anticipated in early life with factors such as maternal diet [ 19 ] and body composition, low childhood intelligence, and negative childhood experiences acting as antecedents of late-life diseases [ 13 ].

The consequential diversity in the capacities and health needs of older people is not accidental. They are rooted in events throughout the life course and SDH that can often be modified, hence opening intervention opportunities. This framework is central in the proposed “Healthy Aging”. According to WHO [ 20 ], Healthy Aging is “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age”.

In this way, the Life Course and SDH approaches allow to better distinguish how social differences in health are perpetuated and propagated, and how they can be diminished or assuaged through generations. Several research efforts suggest that age related mortality and morbidity can be predicted in early life with aspects such as maternal nutrition, low childhood intelligence, difficult childhood experiences acting as antecedents of late-life diseases [ 13 ]. The Life Course acknowledges the contribution of earlier life conditions on adult health outcomes [ 15 , 21 ]. In addition, SDH have an important influence on inequality and, therefore, on people’s well-being and quality of life [ 22 ]. Trends in health literacy across life are also influenced by various SDH such as income, educational level, gender and ethnicity [ 23 ].

Finally, though the research that links early life conditions and health outcomes in adulthood is scarce in low and middle-income countries, our study aims to address the gaps in knowledge regarding the impact of childhood socioeconomic conditions on long-term health outcomes, including the prevalence of non-communicable diseases in LMICs. We specifically focus on the incidence of diabetes in Mexico. Advocating for early-life targeted interventions, we highlight the critical need to address the root causes of NCDs to reduce their impact on the most vulnerable groups. Utilizing data from the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS), which provides comprehensive health, demographic, and socioeconomic information on individuals aged 50 and older, as well as details on their childhoods (before the age of 10) and family health backgrounds [ 24 ], our research emphasizes the importance of developing targeted interventions on early life course stages.

Health, childhood and adulthood conditions

Multiple studies highlight that childhood experiences can influence patterns of disease, aging, and mortality later in life [ 10 , 11 , 16 , 20 , 25 ]. The conditions in health and its social determinants accumulate over the life course. This process initiates with pregnancy and early childhood, continues throughout school years and the transition to working life and later in retirement. The main priority should be for countries to ensure a good start in life during childhood. This requires at least adequate social and health protection for women, plus affordable good early childhood education and care systems for infants [ 11 ].

However, demonstrating links between childhood health conditions and adult development and health is complex. Frequently, researchers do not have the data necessary to distinguish the health effects of changes in living standards or environmental conditions with respect to childhood illnesses [ 26 ]. A study conducted in Sweden, concluded that reduced early exposure to diseases is related to increases in life expectancy. Additionally, research with data from two surveys of Latin America countries found associations between early life conditions and disabilities later in life. In this sense, the study suggests that older people who were born and raised in times of poor nutrition and a higher risk of exposure to infectious diseases, were more likely to have some disability. In a survey in Puerto Rico, it was observed that the probability of being disabled was greater than 64% for people who grew up in poor conditions than for those who grew up in good conditions. Another survey that considered seven urban centers in Latin America found that the probability of disability was 43% higher for those with disadvantaged backgrounds, than for those with favorable ones [ 26 ].

Recent studies have focused on childhood circumstances to explain later life outcomes [ 12 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. These research findings have shown the importance of considering socioeconomic aspects during childhood, including child poverty from a multidimensional perspective [ 12 ], as a determinant of health status of adults and health disparities. When disadvantaged as children, irreversible effects on health show-up frequently. One clear example is the association of socioeconomic aspects during childhood with type 2 diabetes and obesity in adulthood [ 32 , 33 ].

The future development of children is linked to present socioeconomic levels and social mobility in adulthood [ 27 ]. Some studies [ 28 , 34 , 35 ] indicate that the effects of childhood exposure to lower socioeconomic status or conditions of poverty on health in old age may persist independently of upward social mobility in adulthood. Hence, children who grow up in poverty are more likely to present health problems during adulthood, while those who did not grow up in poverty have a higher probability of remaining healthy.

Another important consideration regards developmental mismatches [ 36 ]. Their article emphasizes how developmental and evolutionary mismatches impact the risk of diseases like diabetes. There could be a disparity between the early life environment and the one encountered in adulthood, turning adaptations that were once beneficial into risk factors for non-communicable diseases. High-calorie diets and sedentary lifestyles could trigger diabetes prevalence.

If these connections between early life and health in old age can be established firmly, it is expected that aging people in low and middle-income countries have another disadvantage regarding elders in developed countries, including a higher risk of developing health problems in old age and frequently multiple NCDs [ 26 ]. Under this context, the effective management of NCDs such as diabetes is crucial, and childhood living standards would be a variable to ponder [ 26 , 37 ]. Work related to the Life Course approach has emphasized the importance of considering socioeconomic aspects during childhood, including poverty [ 12 ] as a determinant of adult health status and its disparities [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ].

Data and methods

Data source.

The Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) is a national longitudinal survey of adults aged 50 years and over in Mexico. The baseline survey has national, urban, and rural representation of adults born in 1951 or earlier. It was conducted in 2001 with follow-up interviews in 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018 and 2021 [ 38 ]. New samples of adults were added in 2012 and 2018 to refresh the panel. The survey includes information on health measures (self-reports of conditions and functional status), background (education and childhood living conditions), family demographics, and economic measures. The MHAS (Mexican Health and Aging Study) is partly sponsored by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (grant number NIH R01AG018016) in the United States and the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) in Mexico. Data files and documentation are public use and available at www.MHASweb.org .

In this research, the analysis was based on data from the survey conducted in 2018 (it was the most recent when the project started, later the 2021 survey became available). The study focused exclusively on participants who were aged 50 or older at the time of the 2018 survey. To minimize response bias, the study included only observations from direct interviewees, excluding proxy respondents, and particularly those who completed the section of the questionnaire pertaining to “Childhood Characteristics before the age of 10 years” Footnote 2 . Furthermore, to expand the sample size, individuals who first joined the survey during the 2012 cycle were identified, utilizing data from both the 2012 and 2018 surveys [ 39 ]. After locating the same individuals in both datasets, responses related to childhood conditions from the 2012 survey were extracted and integrated into the 2018 dataset. Biases in the samples were not found. This approach resulted in a total sample size of 8,082 observations.

In addition, we selected a suite of predictor variables to provide a comprehensive examination of the demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related characteristics within our sample (Table 1 ). The cohort consists of 8,082 participants with males exhibiting a marginally higher mean age (58.3 years) compared to females (56.7 years). In terms of educational achievement, males attained a slightly higher level of schooling, averaging 8.3 years, as opposed to 7.6 years for females.