An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Oral Maxillofac Pathol

- v.24(2); May-Aug 2020

Non-Hodgkins lymphoma – A case report and review of literature

Sasidhar singaraju.

Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Rishiraj College of Dental Sciences and Research Centre, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India

Shubham Patel

Ashish sharma, medhini singaraju.

Lymphomas are solid tumors of the immune system and include 14% of all head and neck malignancies. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) are a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders originating in B-, T-, or natural killer T-cells. They have a wide range of histological appearances and clinical features at presentation, which can make diagnosis difficult. A 58-year-old male patient presented with a 1-month history of swelling in the upper right back tooth region, which developed after extraction. On intraoral examination, there was small nodular lesion proliferation from the extracted socket. Biopsy specimen on histological examination revealed sheets of small round cells with hyperchromatic nucleus resembling lymphoblast. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) confirms the NHL of T-cell origin. This article is an attempt to correlate the clinical presentation and histological importance of small round cell tumors of the jaw and to discuss the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors. Typically, a multimodal approach is employed, and the principal ancillary technique that have been found to be useful in classification is IHC.

INTRODUCTION

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of malignancies arising from lymphocytes. Over recent years, improved clinical, pathological and molecular data have helped guide an evolution in the classification of lymphomas that is reflected in the 2016 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification. This recognizes >40 mature B-cell neoplasms and >25 mature T-cell and natural killer (NK)-cell neoplasms.[ 1 ] Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) includes all lymphomas, except Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL). During the past three decades, there have been consistent reports of an increase in the incidence of NHL worldwide. The incidence rates are about 1.5 times higher in men than in women. The average age at diagnosis is about the sixth decade of life, although certain subtypes of NHL, such as Burkitt lymphoma and lymphoblastic lymphoma, have been diagnosed at a younger age.[ 2 ]

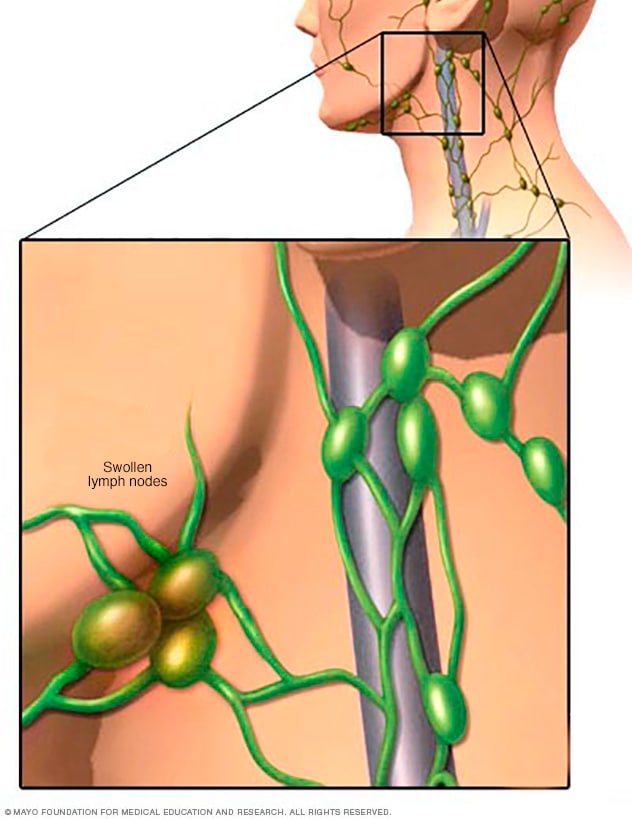

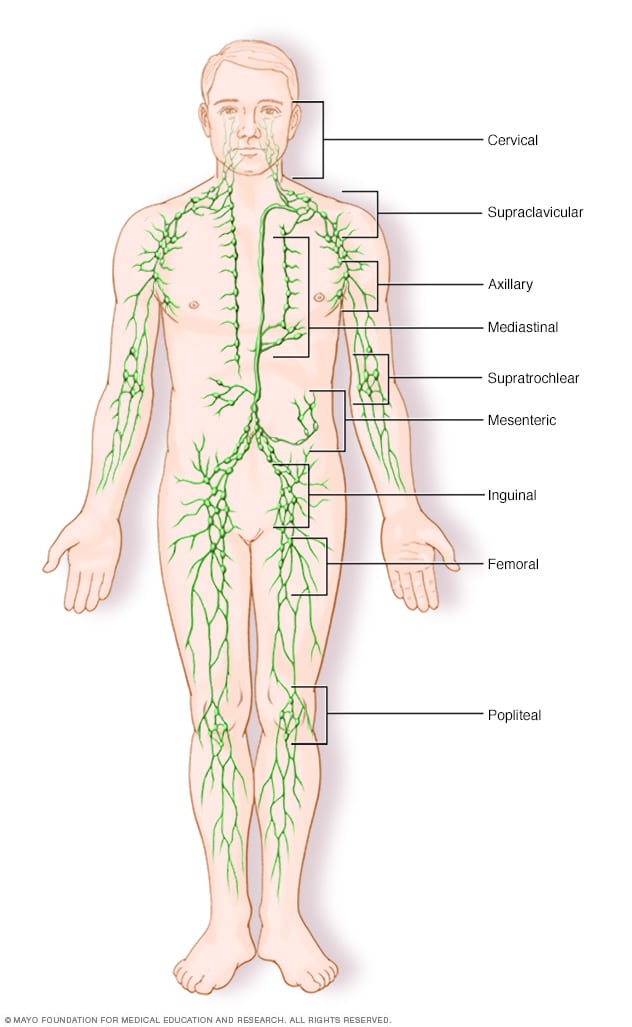

Lymphomas present themselves as enlarged nontender lymph nodes but may involve extranodal regions, commonly involving the gastrointestinal tract and head and neck. Extranodal involvement is much less common in HL than in NHL.[ 3 ]

Recent advances in molecular genetics have significantly deepened our understanding of the biology of these diseases. The introduction of gene expression profiling, especially has led to the discovery of novel oncogenic pathways involved in the process of malignant transformation. Equally important, these analyses have identified novel molecular lymphoma subtypes that are histologically indistinguishable.[ 4 ] There is a significant distinction in the clinical course of germinal center B-cell-like, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and activated B-cell-like DLBCL, as they have a huge variation in the survival rates after standard treatment.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old male patient reported to the college with a chief complaint of swelling and pain in gums in the right upper back tooth region for the past 1 month. Lesion initially started as a small swelling and gradually increased to the present size. Medical history was positive for epistaxis a month back and blood on coughing for 1 month. The patient also gave a history of extraction 2 months in that region after he noticed a loosening of his teeth, which was uneventful. Family history was noncontributory. Extraoral examination revealed mild swelling in the middle-third of the face on the right side [ Figure 1 ].

Extraoral photograph showing mild extraoral swelling on the right side of the face

Intraorally, single large, noduloproliferative growth was seen on the right maxillary ridge, extending from the right second premolar region to maxillary tuberosity area and also up to mid-palate region not crossing the midline [ Figure 2 ]. It was tender on palpation. There was presence of soft-tissue mass protruding from the extraction socket behind 14. The overlying mucosa was reddish pink. The swelling was sessile with ill-defined borders, reddish pink in color and was firm in consistency. Regional lymph nodes were not palpable.

Intraoral swelling seen on the right maxillary ridge

Based on the history and clinical findings, a provisional diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma of maxillary antrum with a differential diagnosis carcinoma of maxillary antrum was made.

A series of radiological and routine hematological investigations were performed. Radiological investigation included orthopantomography and paranasal sinus view. The orthopantomograph revealed loss of maxillary antral bone with ragged borders on the right side. The bone loss is evident up till the floor of the right orbit. There was presence of soft-tissue shadow over the alveolar ridge with complete destruction of the alveolar bone on the right side. Coronoid and condylar processes were normal [ Figure 3a ]. Para nasal sinuses view showed destruction of the superior, lateral, and facial wall of the right maxillary antrum, expansion of the malar bone on the right side laterally with involvement of middle and inferior nasal conchae medially. Furthermore, there was destruction of the right infraorbital margin with the haziness of both antra [ Figure 3b ]. Routine hemogram analysis, urine analysis, and X-ray chest were normal. The patient was negative for HIV and hepatitis B virus.

(a) Orthopantomograph, (b) PNS view

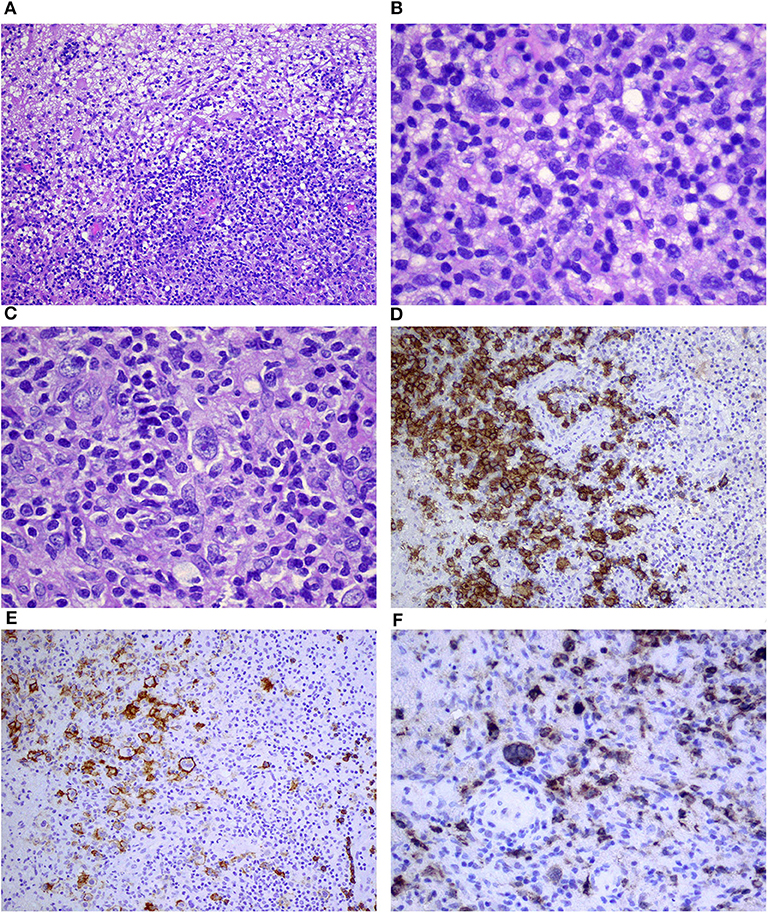

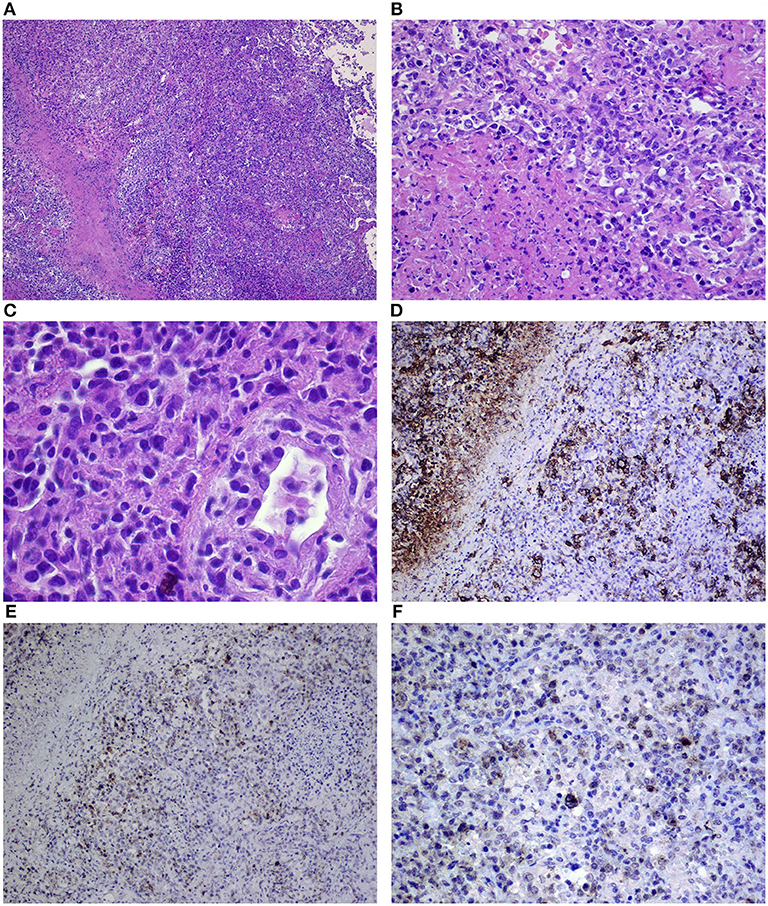

Incisional biopsy under local anesthesia was done. Microscopic pictures revealed squamous mucosa with underlying connective tissue composed of diffuse, uniform monotonous proliferation of small, round cells with large darkly staining nucleus, and little eosinophilic cytoplasm resembling lymphocytes in loose fibrocellular stroma and comedo necrosis suggestive of lymphoproliferative disease [ Figure 4 ].

(a-c) Photomicrographs showing squamous mucosa with underlying connective tissue composed of lymphocytes in loose fibrocellular stroma (H&E stain), (a) ×4, (b) ×10, (c) ×10

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed [ Figure 5 ]. Markers used were CD45 and CD20 which revealed CD45 positivity in tumor cell indicating the tumor cell is hematopoietic in origin and was CD20 negative indicating that it is not B-lymphocytic in origin.

(a and b) CD45, (immunohistochemistry stain, ×4, ×40) (c and d) CD20 (immunohistochemistry stain, ×4, ×40)

Based on the above findings, a diagnosis of NHL of T-cell origin was made.

Surgical excision of the lesion was done under general anesthesia, and postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy were planned. A follow-up of 2 years revealed no local relapse.

Malignant small round cell tumors is a term used for tumors composed of malignant round cells that are slightly larger or double the size of red blood cells in air-dried smears. This group of neoplasms is characterized by small, round, relatively undifferentiated cells. They generally include Ewing's sarcoma, peripheral neuroectodermal tumor, rhabdomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, NHL, retinoblastoma, neuroblastoma, hepatoblastoma, and nephroblastoma. Other differential diagnoses of small round cell tumors include small cell osteogenic sarcoma, undifferentiated hepatoblastoma, granulocytic sarcoma, and intraabdominal desmoplastic small round.[ 5 ] Accurate diagnosis of these cancers is essential because the treatment options, responses to therapy, and prognoses vary widely depending on the diagnosis, and therefore, investigations are needed.

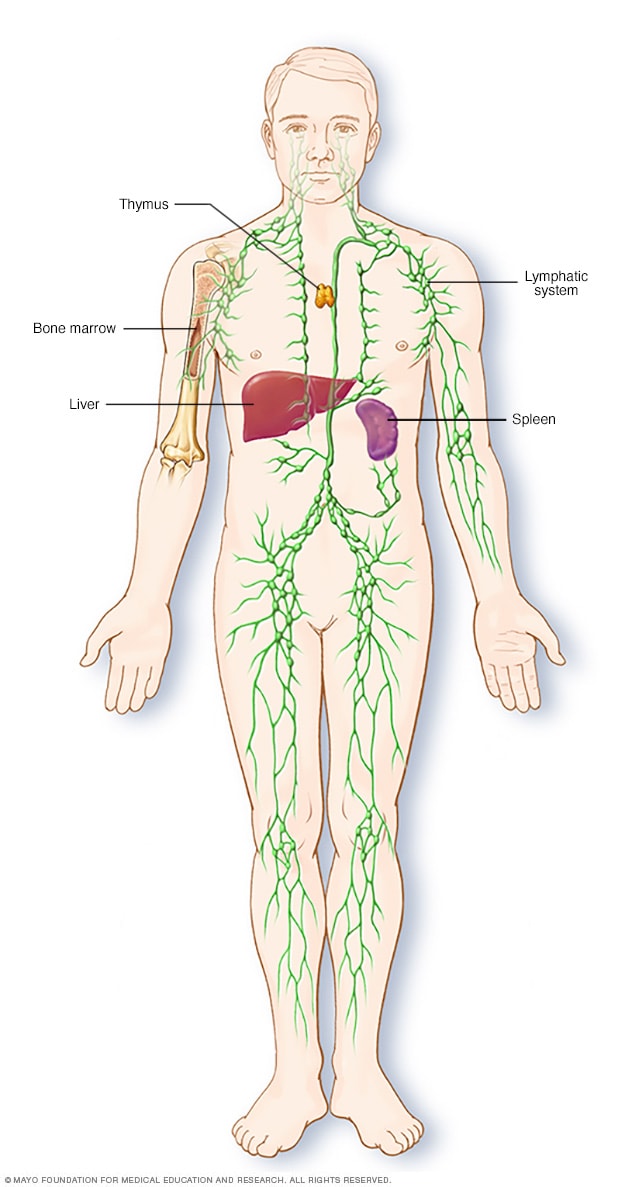

Lymphoma is a general term for a complex group of malignancies of the lymphoreticular system. These malignancies initially arise within the lymphatic tissues and may progress to an extranodular mass (NHL) or to a nontender mass or masses in a lymph node region (HL) that later may spread to other lymph node groups and involve the bone marrow. Lymphoma in the oral soft tissues usually presents as an extranodal, soft to firm asymptomatic lesion, although the mass may also be painful.[ 6 ]

The WHO modification of the Revised European–American Lymphoma Classification recognizes three major categories of lymphoid malignancies, which are B-cell lymphoma, T-cell/NK cell lymphoma, and Hodgkin's lymphoma. NHL is one of the possible cancers in the head-and-neck region, and among extranodal NHLs, this is the second most common site after the gastrointestinal tract. In the head and neck, Waldeyer's ring is the most common site of origin and may be accompanied by cervical node involvement. Nose, paranasal sinus, orbits, and salivary glands are other possible organs affected in decreasing order of frequency, with rare spread to the regional lymph nodes.[ 3 ] NHL has long been recognized as a heterogeneous group of disorders based on clinical presentation, morphological appearance, and response to therapy. In recent years, the use of immunological and molecular biological techniques has led to important advances in our knowledge of lymphocyte differentiation and has provided the basis for a better understanding of the cellular origin and pathogenesis of NHL.[ 6 ] Various types of NHL represents neoplastic cells arrested at various stages in the normal differentiation scheme or the gain of a proliferative or anti-apoptotic abnormality, whose precise phenotype depends on the developmental stage, at which the lymphocyte is affected.

T-cell NHLs are uncommon malignancies that represent approximately 12% of all lymphomas.[ 7 ] There are no characteristic clinical features of lymphomas of the oral region, and they depend on the site of the swelling, the lymph node involvement, and/or the presence of metastasis. The most common beginning symptoms are local mass, pain or discomfort, dysphagia or sensation of a foreign body in the throat, in the case of tonsillar NHL.[ 3 ] T-cell NHL commonly presents with extranodal disease and often contains varying amounts of necrosis/apoptosis on biopsy specimens, making differentiation between a reactive process and lymphoma challenging. Immunophenotypic, cytogenetic, and molecular analyses have enhanced diagnostic capabilities and improved classification and prognostication for T-cell NHL. There are 28 different established and provisional mature T-cell/NK cell entities in the 2016 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms, broadly subdivided into two groups: peripheral T-cell lymphoma and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.[ 8 ]

IHC is an integral part of the diagnostic chematopathology. IHC with various antibodies identifies the specific lineage and developmental stage of the lymphoma. Panel of markers is decided based on morphologic differential diagnosis (no single marker is specific), which includes leukocyte common antigen (LCA), B-cell markers (CD20 and CD79a), T-cell markers (CD3 and CD5), and other markers such as CD23, bcl-2, CD10, cyclinD1, CD15, CD30, ALK-1, and CD138 (based on cytoarchitectural pattern).[ 9 ]

Basic immunohistochemistry panel for non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Expression of CD45 (LCA) rules out an epithelial tumor and suggests the tumor is of hematopoietic origin.

NHL is further subclassified based on the stage of maturation (immature vs. mature) and the cell of origin (B-cell, T-cell, or NK cell).

- CD20 is the most widely used pan-B-cell marker

- CD3 is the most commonly used pan-T-cell antigen

- CD4 is for helper T-cells, CD8 for suppressor cells, and CD57 for NK cells.

In our case, apart from epistaxis and blood after coughing, the patient did not show any other specific signs. Extraoral examination revealed mild facial asymmetry. Primary lymphomas are more common in females. However, in our case, it was an old-aged male. The occurrence of NHL is common in developed countries than developing nations. Among the developing nations, few of the Middle Eastern nations show moderate-to-high intensity. In a study, it was uncovered that the average age-adjusted rate of incidence and percentage of annual change in adjusted rates of age for NHL by sex in five cities of India showed a statistically significant increase in number over a period of two decades.[ 10 ]

The management of NHL affecting head and neck relies on the Ann Arbor staging. An indolent assortment might be treated with radiation therapy alone, whereas a disseminated variety requires a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Isolated lesions are managed by surgical enucleation. However surgery is combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy for better results. The prognosis of the disease depends on the stage of the disease, which has reported 5-year survival rate for 50% of cases in the maxilla and mandible.[ 10 ]

Small round cell tumors are difficult to distinguish by light microscopy, and currently, no single test is available, which can precisely distinguish these tumors. Hence to confirm the diagnosis, pathologists should go for several other techniques like IHC. IHC for individual protein markers is used to establish the diagnosis in many instances, and its accuracy rate is also quite satisfactory. Thus, IHC can be helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis of small round cell tumors, so as the treatment outcome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

- Sign In to save searches and organize your favorite content.

- Not registered? Sign up

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Subscriptions

- Join E-mail List

Patient Case Studies and Panel Discussion: Lymphoma

- Get Citation Alerts

- Download PDF to Print

A heterogeneous group of diseases, lymphomas encompass a range of diagnoses that call for varied treatment approaches. Although some lymphomas require minimal intervention for cure or remission, others can be very difficult to treat and are associated with poor outcomes. At the NCCN 2019 Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies, a panel of experts used 3 case studies to develop an evidence-based approach for the treatment of patients with lymphomas. Moderated by Ranjana H. Advani, MD, the session focused on peripheral T-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Lymphomas are a heterogeneous group of diseases with a range of diagnoses that require varied treatment approaches. Although some lymphomas require minimal intervention for cure or remission, others can be difficult to treat and are associated with poor patient outcomes. At the NCCN 2019 Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies, a panel of experts identified clinical challenges in managing patients with lymphoma. Moderated by Ranjana H. Advani, MD, Saul A. Rosenberg Professor of Lymphoma, Stanford Cancer Institute, the session focused on 3 case studies, which were used to develop an evidence-based approach for treatment of these patients. Panelists included Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, MMSc, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center; Mrinal Dutia, MD, The Permanente Medical Group; Richard I. Fisher, MD, Fox Chase Cancer Center; and Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

- Patient Case Study 1: Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma

In the first case study, a 44-year-old woman presented with a dry, nonproductive cough that she had been experiencing for 2 to 3 months, intermittent bouts of severe shortness of breath, decreased appetite, and a 20-pound weight loss. Chest radiograph revealed mild bilateral pleural effusion and bilateral pulmonary nodules, with the largest nodule measuring 5 cm in the right upper lobe. The patient was admitted for further evaluation, and additional testing was performed (see Figure 1 for results). Bone marrow evaluation revealed no morphologic abnormalities, but complex cytogenetics and the same T-cell clone was found as in the lung biopsy. Therefore, a diagnosis was made of stage IVB peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) with T-follicular helper (TFH) phenotype most consistent with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL).

Patient case study 1: results of further testing.

Abbreviations: NGS, next-generation sequencing; RUL, right upper lobe; SUV, standard uptake value; VATS, video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Citation: Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17, 11.5; 10.6004/jnccn.2019.5028

Dr. Advani explained that this “complicated terminology” comes from recent updates to the WHO classification for PTCL. 1 , 2 Furthermore, she explained that in recent years, advances in molecular biology have helped elucidate the underlying genetic complexity of PTCL and identify mutations and signaling pathways involved in lymphomagenesis. Importantly, many of the same genetic changes observed in AITL are also seen in PTCL not otherwise specified (NOS) that manifest a TFH phenotype. For this designation, the neoplastic cells should express at least 2 or 3 TFH-related antigens, including PD-1, CD10, BCL6, CXCL13, ICOS, SAP, and CCR5.

One potential treatment regimen to use in this patient population is CHOP (cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/vincristine/prednisone), which is associated with complete response (CR) rates of 50% to 60% in non–anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) and a 5-year overall survival rate of 40% to 60%. According to Dr. Advani, patients with low International Prognostic Index (IPI) scores perform significantly better; however, relapse is associated with poor patient outcomes. “The ongoing challenge is to achieve higher CR rates and to translate those remissions into long-term survival,” said Dr. Advani.

Another treatment option is the CHOEP regimen, which adds etoposide to CHOP. Retrospective studies suggest that outcomes may be better than historical data with CHOP. 3 – 5 In a prospective trial, the Nordic group evaluated the role of autologous stem cell transplantation after patients achieved a CR/partial response with CHOEP. 6 At a median follow-up of 5 years, the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) rates for AITL were 49% and 52%, respectively, and 38% and 47% for PTCL-NOS, respectively.

Finally, the phase III ECHELON-2 study was the first prospective trial in PTCL to show an OS benefit over CHOP. 7 Frontline therapy for CD30-positive PTCL comparing brentuximab vedotin + cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin/prednisone (BV-CHP) versus CHOP led to a significant improvement in PFS and OS for patients, with a comparable safety profile. The FDA subsequently approved brentuximab vedotin in combination with CHP for adults with previously untreated systematic ALCL or other CD30-expressing PTCL, including AITL and PTCL-NOS. “Based on these data, currently BV-CHP should be the standard regimen for untreated ALCL and other histologies that are CD30-postive,” said Dr. Advani.

In the current case study, the patient received treatment with CHOEP and growth factor support. However, after 2 cycles, PET/CT scan showed no change in lung lesions with a worsening of right-sided pleural effusion (Deauville score 5). Thoracentesis of the pleural effusion was negative for infection but positive for abnormal T-cell population, with morphologic and immunophenotypic findings consistent with the initial diagnosis of PTCL with TFH phenotype most consistent with AITL. The patient was then started on single-agent brentuximab vedotin every 3 weeks. After 4 cycles, PET/CT scan revealed marked improvement in all lesions (Deauville score 4) and was continued on brentuximab vedotin for an additional 4 doses. PET/CT after 8 cycles revealed the resolution of lung nodules and adenopathy in the right axilla with increased metabolic activity (Deauville score 4).

Currently, 4 agents are FDA-approved for use in relapsed/refractory PTCL: pralatrexate, romidepsin, belinostat, and brentuximab vedotin. Aside from brentuximab vedotin use in ALCL, however, overall response rates are low. Brentuximab vedotin has been evaluated in relapsed/refractory AITL, showing an ORR of 54%. 8 Responses did not correlate with level of CD30 expression.

Although no randomized studies have analyzed the role of consolidative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, data from the prospective COMPLETE study suggested improved outcomes in patients with PTCL AITL and PTCL-NOS. 9 On the other hand, said Dr. Advani, data from the LYSA study do not support the use of autologous stem cell transplant for upfront consolidation in patients with PTCL-NOS, AITL, or ALK-ALCL who have achieved a complete or partial response after induction. 10

“If patients are young and have achieved remission or even a partial response, most of us tend to transplant because outcomes with relapsed disease are very poor,” Dr. Advani concluded. “None of the approved drugs are home runs. The best chance you get is your first chance.”

- Patient Case Study 2: Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma

In the second case study, a 21-year-old woman presented with severe cough and weight loss. Physical examination showed dilated veins on the anterior chest wall and no palpable peripheral lymphadenopathy. Chest radiograph revealed right-sided pleural effusion and a large mediastinal mass measuring 10.8 cm. Additional testing was performed. PET/CT scan showed a bulky anterior mediastinal mass with SUV max of 24.1 and subcarinal and right hilar adenopathy. However, no evidence of disease was observed below the diaphragm. Bone marrow biopsy was negative. Mediastinoscopy with a biopsy of the mass showed diffuse lymphoid proliferation of intermediate-size atypical cells positive for CD20, CD79A, PAX5, CD30 (dim), MUM1, BCL2, and BCL6, and negative for CD10, BCL1, and EBER. Florescence in situ hybridization was negative for MYC , BCL2 , and BCL6 rearrangements. The final diagnosis of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) was made.

According to Dr. Advani, current treatment choices for PMBL are CHOP + rituximab (R-CHOP) with radiotherapy versus more intensive regimens, such as dose-adjusted etoposide/prednisone/vincristine/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin + rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R), without radiotherapy. In one study of DA-EPOCH-R with median follow-up of 8.4 years, PFS and OS were both 90%. 11 Another retrospective multicenter analysis that stratified patients by frontline regimen of either DA-EPOCH-R or R-CHOP showed a higher complete response with DA-EPOCH-R (84% vs 70%; P =.046), but the patients in this arm were also more likely to experience treatment-related toxicities. 12 At 2 years, 89% of patients in the R-CHOP arm and 91% of those in DA-EPOCH-R arm were still alive. Despite these similar outcomes, the consensus among panelists was that DA-EPOCH-R was the preferred option.

The patient in the current case report was started on DA-EPOCH-R, with an initial favorable response: interim imaging showed a reduction in size of the anterior mediastinal mass (5 x 6.3 x 9.6 cm) and resolution of left upper pulmonary nodules. The patient continued on DA-EPOCH-R for 4 additional cycles. PET/CT scans 4 weeks posttreatment revealed a metabolically inactive, irregularly shaped anterior mediastinal mass (5.5 x 4 x 5.2 cm) and a focal area of low metabolic activity within the mass (SUV max 3.5; Deauville score 4). She was asymptomatic, and the decision was made to follow with observation. After 2 months, PET/CT scans showed a stable mediastinal mass with increased metabolic activity (SUV max 6). Biopsy of the mediastinal mass was performed and immunohistochemistry results were consistent with relapsed PMBL; immunohistochemistry showed 30% of large cells were CD20- and CD30-positive.

“With PMBL, most of the cures are from initial therapy,” said Dr. Advani. “Salvage rates in recurrent/refractory disease are quite poor.” Overall response rates in PMBL are 25% versus 48% for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and 2-year overall survival is only 15% versus 24%, respectively. 13

Although CD19 CAR T-cell therapy has been approved, said Dr. Advani, there are very limited data on its use in relapsed/refractory PMBL. According to Jeremy S. Abramson, MD, MMSc, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, and Director of the Lymphoma Center, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, the limited available data are indeed encouraging in relapsed/refractory PMBL, and are “looking similar” to those for third-line treatment in DLBCL. Currently 3 randomized clinical trials are evaluating CAR T-cells versus autologous stem cell transplant (the current standard of care) as second-line therapy for relapsed/refractory DLBCL, PMBL, and high-grade B-cell lymphomas, and these trials may ultimately change the standard of care in these patients.

Another treatment option for use in patients with relapsed/refractory PMBL is immune checkpoint inhibitors. Pembrolizumab has shown response rates of 40% to 50% and is now approved by the FDA for use in the third-line and beyond. 14 Furthermore, combination brentuximab vedotin + nivolumab showed even more robust activity, with an overall response rate of 73%. 15

The patient in this case study received 5 cycles of pembrolizumab, and PET/CT scans showed a complete metabolic response.

- Patient Case Study 3: From Follicular Lymphoma to DLBCL

In the last case study, a 48-year-old man presented with enlarged lymph nodes in his left neck and right groin measuring up to 2 cm. He was asymptomatic and had no evidence of B symptoms. Laboratory test results were all normal. Excisional biopsy of the left cervical node showed follicular lymphoma (grade 1–2). PET/CT scan revealed left cervical, axillary, and right external iliac and inguinal adenopathy, with the largest node measuring 1.0 x 2.0 cm (SUV max 5.5). There was no splenomegaly or effusions. Bone marrow biopsy showed normal trilineage hematopoiesis. The diagnosis of stage IIIA follicular lymphoma (grade 1–2) was made, with a Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score of 1. Panelists agreed that the best approach for this patient was watchful waiting. Therapy was deferred, and the patient was followed with observation.

Two years later, the patient presented with enlarging lymph nodes in his left neck. He was anxious and had mild fatigue. Results of laboratory tests were normal. PET/CT scan showed increased adenopathy above and below the diaphragm, with the largest node (right external iliac node) measuring 3.4 x 2.8 cm (SUV max 8.4). A biopsy of the right external iliac node was performed, with results showing follicular lymphoma (grade 1–2).

Panelists agreed that observation was an acceptable approach for an asymptomatic patients diagnosed with follicular lymphoma with low-volume disease. However, the patient opted for 4 doses of weekly rituximab. Repeat PET/CT (3 months posttreatment with rituximab) showed that most lymph nodes had resolved. Three years later, the patients presented with a new severe pain in the low back radiating down his right leg. MRI of the L-spine showed a T1 hypointense infiltrative mass replacing the L3 vertebral body. A core biopsy of right psoas mass showed that his follicular lymphoma had transformed to DLBCL, germinal center B-cell–like subtype, with double expressors of MYC >40% and BCL2 >50% and MYC translocation–negative, and expression of Ki67 was 90%. IPI score was 4.

Andrew D. Zelenetz, MD, PhD, Professor of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, explained the unique biology of the “double-expressor” phenotype in DLBCL. “This is the one circumstance where DA-EPOCH-R may have a distinct benefit,” he said. “However, in the absence of MYC translocation, it is not clear that overexpression of MYC, which is biologically driven without the translocation, shows a benefit from this intensive regimen.”

The patient received 6 cycles of DA-EPOCH-R with 4 doses of intrathecal methotrexate. Results of interim and end-of-therapy PET scans showed a metabolic complete response (Deauville score 2).

Double-hit and double-expressor lymphomas tend to have inferior outcomes with R-CHOP therapy, Dr. Advani stated. Several retrospective studies and one prospective trial suggest improved outcomes with intensive chemotherapy for double-hit lymphomas. 16 – 18 “Patients with a very high IPI, advanced-stage disease, or extranodal involvement are the ones that I consider good candidates for DA-EPOCH-R,” she said, and also noted that double-expressor DLBCLs have a higher risk of central nervous system (CNS) relapse independent of CNS-IPI.

The patient in the current case study had a CNS-IPI of 3 and an 11% cumulative incidence of CNS relapse at 2 years. Data support some form of CNS prophylaxis, 19 Dr. Advani concluded, but the jury is still out regarding optimal treatment for double-expressor non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Swerdlow SH , Campo E , Pileri SA , et al. . The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms . Blood 2016 ; 127 : 2375 – 2390 .

- Search Google Scholar

- Export Citation

Hildyard C , Shiekh S , Browning J , Collins GP . Toward a biology-driven treatment strategy for peripheral T-cell lymphoma . Clin Med Insights Blood Disord 2017 ; 10 :1179545X17705863.

Cederleuf H , Bjerregard Pedersen M , Jerkeman M . The addition of etoposide to CHOP is associated with improved outcome in ALK+ adult anaplastic large cell lymphoma: a Nordic Lymphoma Group study . Br J Haematol 2017 ; 178 : 739 – 746 .

Schmitz N , Trümper L , Ziepert M , et al. . Treatment and prognosis of mature T-cell and NK-cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients with T-cell lymphoma treated in studies of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group . Blood 2010 ; 116 : 3418 – 3425 .

Janikova A , Chloupkova R , Campr V , et al. . First-line therapy for T cell lymphomas: a retrospective population-based analysis of 906 T cell lymphoma patients . Ann Hematol 2019 ; 98 : 1961 – 1972 .

d’Amore F , Relander T , Lauritzsen GF , et al. . Up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: NLG-T-01 . J Clin Oncol 2012 ; 30 : 3093 – 3099 .

Horwitz S , O’Connor OA , Pro B , et al. . Brentuximab vedotin with chemotherapy for CD30-positive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (ECHELON-2): a global, double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial . Lancet 2019 ; 393 : 229 – 240 .

Horwitz SM , Advani RH , Bartlett NL , et al. . Objective responses in relapsed T-cell lymphomas with single-agent brentuximab vedotin . Blood 2014 ; 123 : 3095 – 3100 .

Park SI , Horwitz SM , Foss FM , et al. . The role of autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas in first complete remission: Report from COMPLETE, a prospective, multicenter cohort study . Cancer 2019 ; 125 : 1507 – 1517 .

Fossard G , Broussais F , Coelho I , et al. . Role of up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma for patients in response after induction: an analysis of patients from LYSA centers . Ann Oncol 2018 ; 29 : 715 – 723 .

Melani C , Advani R , Roschewski M , et al. . End-of-treatment and serial PET imaging in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma following dose-adjusted EPOCH-R: a paradigm shift in clinical decision making . Haematologica 2018 ; 103 : 1337 – 1344 .

Shah NN , Szabo , Huntington SF , et al. . R-CHOP versus dose-adjusted R-EPOCH in frontline management of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: a multi-centre analysis . Br J Haematol 2018 ; 180 : 534 – 544 .

Kuruvilla J , Pintilie M , Tsang R , et al. . Salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation are inferior for relapsed or refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma compared with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma . Leuk Lymphoma 2008 ; 49 : 1329 – 1336 .

Zinzani PL , Ribrag V , Moskowitz CH , et al. . Safety and tolerability of pembrolizumab in patients with relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma . Blood 2017 ; 130 : 267 – 270 .

Zinzani PL , Santoro A , Gritt G , et al. . Nivolumab combined with brentuximab vedotin for relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma: efficacy and safety from the phase II CheckMate 436 study [published online August 9, 2019] . J Clin Oncol . doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01492

Petrich AM , Gandhi M , Jovanovic B , et al. . Impact of induction regimen and stem cell transplantation on outcomes in double-hit lymphoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis . Blood 2014 ; 124 : 2354 – 2361 .

Oki Y , Noorani M , Lin P , et al. . Double hit lymphoma: the MD Anderson Cancer Center clinical experience . Br J Haematol 2014 ; 166 : 891 – 901 .

Dunleavy K , Fanale MA , Abramson JS , et al. . Dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab) in untreated aggressive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with MYC rearrangement: a prospective, multicentre, single-arm phase 2 study . Lancet Haematol 2018 ; 5 : e609 – 617 .

Savage KJ , Slack GW , Mottok A , et al. . Impact of dual expression of MYC and BCL2 by immunohistochemistry on the risk of CNS relapse in DLBCL . Blood 2016 ; 127 : 2182 – 2188 .

Disclosures: Dr. Advani has disclosed that she has received grant/research support from Agensys, Inc., Celgene Corporation, Forty Seven, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP, Kura Oncology, Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., Pharmacyclics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Seattle Genetics, Inc.; received consulting fees from AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Bayer HealthCare, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Kite Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Cell Medica, Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc.; and is a scientific advisor for AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Bayer HealthCare, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Kite Pharma, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Cell Medica, Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, Inc. Dr. Abramson has disclosed that he receives consulting fees from AbbVie, Inc., Bayer HealthCare, Celgene Corporation, EMD Serono, Genentech, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Kite Pharma, and Roche Laboratories, Inc. Dr. Dutia has disclosed that she has no interests, arrangements, affiliations, or commercial interests with the manufacturers of any products discussed in this article or their competitors. Dr. Fisher has disclosed that he receives consulting fees from Celgene Corporation and PRIME. Dr. Zelenetz has disclosed that he received consulting fees from AbbVie, Inc., Amgen Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, Celgene Corporation, Gilead Sciences, Inc., Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Adaptive Biotechnologies Corporation, Genentech, Inc./Roche Laboratories, Inc., and Pharmacyclics; is a scientific advisor for AbbVie, Inc., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, and MorphoSys AG; and receives grant/research support from BeiGene, Gilead Sciences, Inc., MEI Pharma Inc., and Roche Laboratories, Inc.

Article Sections

- View raw image

- Download Powerpoint Slide

Article Information

- Get Permissions

- Similar articles in PubMed

Google Scholar

Related articles.

| All Time | Past Year | Past 30 Days | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abstract Views | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Full Text Views | 10616 | 2526 | 211 |

| PDF Downloads | 6141 | 1628 | 157 |

| EPUB Downloads | 0 | 0 | 0 |

- Advertising

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Permissions

© 2019-2024 National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Powered by:

- [195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Case studies of elderly patients with non-hodgkin's lymphoma.

Share and Cite

Luminari, S.; Federico, M. Case Studies of Elderly Patients with Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Hematol. Rep. 2011 , 3 , e7. https://doi.org/10.4081/hr.2011.s3.e7

Luminari S, Federico M. Case Studies of Elderly Patients with Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Hematology Reports . 2011; 3(s3):e7. https://doi.org/10.4081/hr.2011.s3.e7

Luminari, Stefano, and Massimo Federico. 2011. "Case Studies of Elderly Patients with Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma" Hematology Reports 3, no. s3: e7. https://doi.org/10.4081/hr.2011.s3.e7

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2021

A case report of COVID-19 in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Owrang Eilami 1 ,

- Max Igor Banks Ferreira Lopes 2 ,

- Ronaldo Cesar Borges Gryschek 3 &

- Kaveh Taghipour ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3839-2607 4

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 21 , Article number: 809 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

1 Citations

8 Altmetric

Metrics details

The current literature is scarce as to the outcomes of COVID-19 infection in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients and whether immunosuppressive or chemotherapeutic agents can cause worsening of the patients’ condition during COVID-19 infection.

Case presentation

Our case is a 59-year-old gentleman who presented to the Emergency Department of the Cancer Institute of Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil on 10th May 2020 with a worsening dyspnea and chest pain which had started 3 days prior to presentation to the Emergency Department. He had a past history of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma for which he was receiving chemotherapy. Subsequent PCR testing demonstrated that our patient was SARS-CoV-2 positive.

In this report, we show a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the middle of chemotherapy, presented a mild clinical course of COVID-19 infection.

Peer Review reports

Since the first identification of COVID-19 in an outbreak in Wuhan China in December 2019 COVID-19 has quickly spread worldwide and was declared a worldwide pandemic on 11th March 2020. The clinical presentation of COVID-19 is variable with a clinical spectrum ranging from asymptomatic to life-threatening clinical presentation [ 1 ]. One would expect immunocompromised patients would be at high risk of complications from COVID-19 infection, however, there have been reports of variable clinical presentation and clinical course within this subgroup of patients [ 2 ]. Currently the data regarding risk and outcome of infection by SARS-CoV-2 in lymphoma patients is scarce and variable. Lymphoma patients present an interesting subgroup as they typically receive immunosuppressive and chemotherapy drugs during their treatment. We are presenting a case of symptomatic COVID-19 with comorbid non-Hodgkin's lymphoma who was receiving chemotherapy and subsequently recovered from COVID-19 infection.

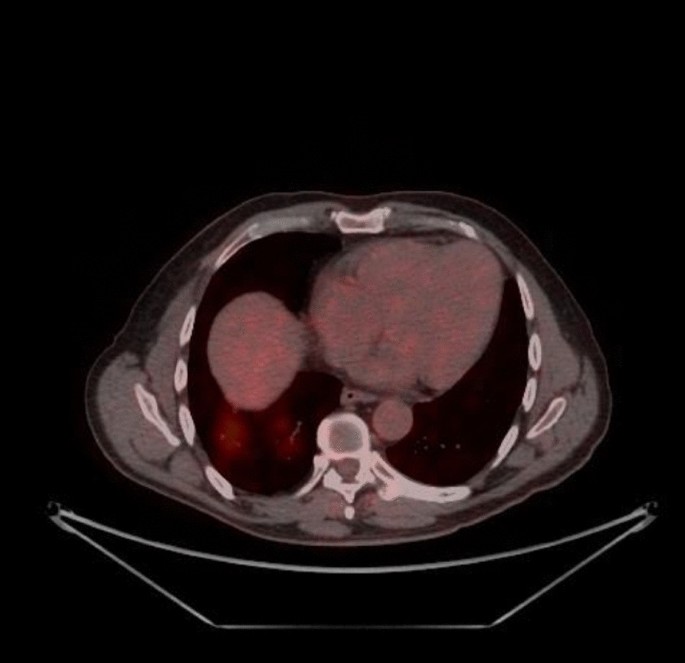

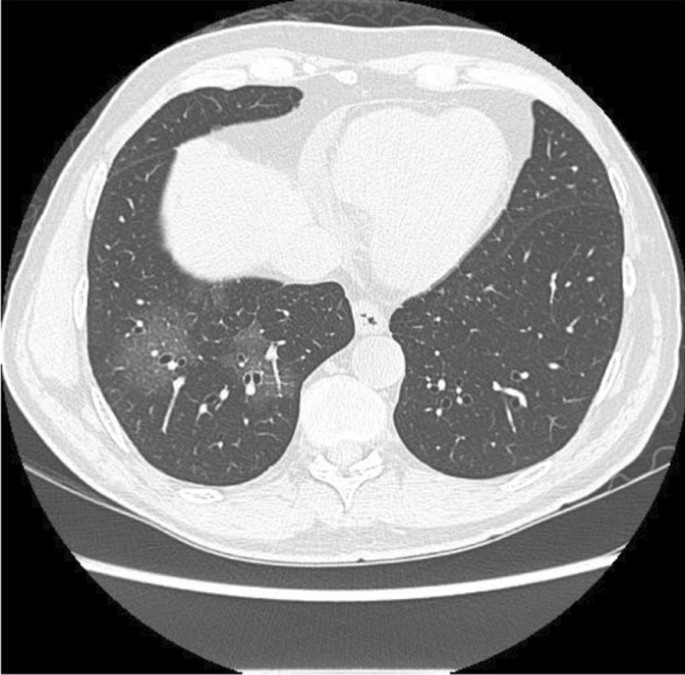

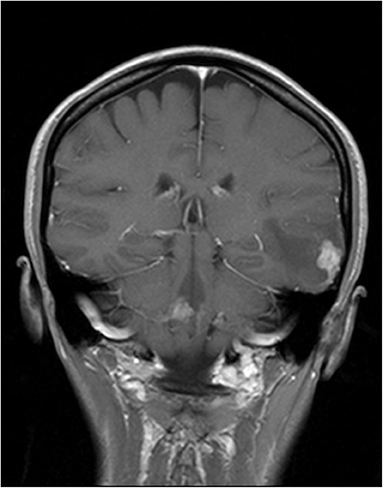

Our patient is a 59-year-old gentleman who presented to the Emergency Department of the Cancer Institute of Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil on 10th May 2020 with worsening dyspnea and chest pain for the last 3 days. Five months prior to presentation he had been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and previously, on April 29th during a routine follow-up hospital admission for his lymphoma, he had a routine PET CT (Fig. 1 ) and chest CT scan (Fig. 2 ) performed for lymphoma follow-up showing bilateral ground-glass lung lesions with less than 25% of lung involvement suggestive of COVID-19 infection. Subsequent COVID-19 PCR revealed that the patient was COVID-19 positive, however as he was asymptomatic, he was discharged.

PET-CT 29/04: appearance of multiple areas of discrete opacity bilateral in pulmonary parenchyma, predominating in the base (SUVmax: 3.7-right base. The comparative analysis with a previous examination of 03/18/2020 shows: the degree of glycolytic hypermetabolism persists without significant variation associated with reduced dimensions, in heterogeneous tissue formation. The findings are compatible with uptake above mediastinal, but below or equal to uptake in the liver with nodal or extranodal sites with or without a residual mass indicating a non-progressive disease with a complete metabolic response to lymphoma treatment. The appearance of multiple areas of ground-glass opacities sparse by the bilateral pulmonary parenchyma, predominantly at the right base, suspicious for viral pneumonia

Computed tomography of the chest without the administration of the intravenous contrast medium—pulmonary ground-glass opacities and foci of consolidation, sometimes associated with septal thickening, with multifocal distribution, bilateral and predominantly peripheral. The estimated extent of involvement in pulmonary tomography is less than 50%

Comorbidities presented were systemic arterial hypertension treated with losartan 50 mg bid and non-insulin-dependent diabetes treated with 60 mg of gliclazide per day and metformin 850 mg q8h.

The past medical history of our patient includes the diagnosis of lymphoma on December 1st, 2019, after an exploratory laparotomy due to perforating acute abdomen resulting in enterectomy of the perforated segment (15 cm resection) plus manual end-to-end anastomosis + Barker peritoniostomy (due to hemodynamic instability). On December 5th—a second look abdominal surgery was performed with wall closure and mesh placement. The lymphoma was classified as diffuse large cells non-Hodgkin lymphoma—CD20 negative. The patient started CHOP chemotherapy [cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone] with cycles every 21 days last on April 16th and three cycles of intrathecal methotrexate (MTX) chemotherapy last on March 16th.

Eleven days following discharge from the patient's first admission, the patient’s condition worsened. Subsequently on 10th of May 2020, the patient presented with worsening cough, dyspnea and chest pain to the Emergency Department of the Cancer Institute of Hospital das Clínicas da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. Due to the patients deteriorating condition the patient was admitted to hospital.

During his latest hospital stay, he was prescribed ceftriaxone 2 g QD for seven days, azithromycin 500 mg QD for five days, enoxaparin 40 mg QD, oseltamivir 75 mg bid for two days (until the result of SARS-CoV-2 RT PCR positive). He received pneumocystis prophylaxis with sulfamethoxazole 400 mg + trimethoprim 80 mg and acyclovir 200 mg QD for herpes simplex prophylaxis. A second chest CT scan was performed (Fig. 3 ) which demonstrated an increase in the extension and attenuation of pulmonary opacities compared with the patient’s previous chest CT scan (Fig. 2 ). The patient’s clinical condition was stable without any worsening of clinical condition and biochemical markers (Table 1 ) during his hospital stay and maximum oxygen intake of 3L/min by nasal cannula. The oxygen supplementation was titrated and interrupted on May 13th. On May 19th, the patient was discharged. At that time, a second nasal SARS-CoV-2 RT PCR was performed and resulted in a negative result.

Computed Tomography of the Chest without the administration of the intravenous contrast medium—these set of findings is suggestive of the inflammatory process, and the viral etiology must be included in the etiological differential, particularly COVID-19. Regarding the PET-CT 29/04/2020 exam, there was an increase in the extension and attenuation of pulmonary opacities

Discussion and conclusion

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma presents a dilemma to healthcare professionals as there is concern that chemotherapeutic and immunosuppressive treatment which is a pillar of cancer therapy may lead to a worsening of comorbid COVID-19 infections.

The current literature is scarce as to the outcomes of COVID-19 infection in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients and whether immunosuppressive or chemotherapeutic agents can cause worsening of the patients’ condition during COVID-19 infection. Our case of a 59-year-old gentleman with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presents a glimpse and discussion of current assumptions of this subgroup of patients and comorbid COVID-19 infection because contrary to our expectations the patient had a benign clinical course without any evidence of worsening of symptoms that are contrary to our experience with other infections that are often more frequent and more severe in cancer and hematological malignancy patients.

The clinical presentation of our patient was that he had progressive dyspnea without fever. Only on the 4th day following admission the patient developed fever which is in contrast to a retrospective study by Zhang et al. conducted in Wuhan, China of 28 COVID-19-infected cancer patients which had shown that fever was present in 82.1% of patients followed by dry cough in 81% of patients and dyspnea in 50% of patients [ 3 ]. In another retrospective study by Yang et al. of 52 cancer patients with COVID-19 the common presenting symptoms were: fever (25%), dry cough (17.3%), chest distress (11.5%), and fatigue (9.6%) [ 4 ].

In a study by Chen and colleagues of 128 hospitalized patients with hematological cancer in two centers in Wuhan China it was shown that there was no significant difference in the case rate between in hematological malignancy patients versus non hematological malignancy patients [ 5 ]. Furthermore, patients with hematological malignancy had more severe disease and increase fatality when infected by COVID-19. In a study by Yigenoglu et al. of 740 COVID-19 patients with hematological malignancy it was shown that the length of hospital and ICU admission were higher in patients with hematological malignancy compared to patients without cancer [ 6 ]. However, the length of hospital stays and ICU stay was similar between groups. In a case report of 4 patients by Bellmann-Weiler et al. All 4 patients had COVID-19 infection with comorbid hematological malignancy all recovered from COVID-19 and were discharged. The authors noted that hyperinflammatory associated organ failure may be less pronounced in hematological malignancies due to treatment related immunosuppression [ 7 ]. In an observational study by Norsa et al. of 522 patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Northern Italy it was observed that of these patients none were admitted to hospital with SARS-CoV-2 proven infection and none of the patients with IBD in this study was affected by a complicated SARS-CoV-2–related pneumonia [ 8 ]. The authors concluded that the data suggest that patients receiving immunosuppressive treatments could be at lower risk of developing severe symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection.

It is well-known that systemic inflammation and the resulting cytokine cascade is an important pathophysiological mechanism in the development of COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress [ 9 ]. The resulting therapies for COVID-19 have been aimed at reducing systemic inflammation. In a study by Lee et al. On 800 patients who had a diagnosis of cancer and symptomatic COVID 19 they were unable to find that cancer patients on active cytotoxic chemotherapy were at increased risk of mortality from COVID-19 compared to those cancer patients not on chemotherapy [ 10 ].

Unfortunately, data on COVID-19 among cancer patients is still scarce, with few described cases. Along with the small sample size of only Chinese patients, there is a large amount of heterogeneity due to several cancer types and different oncologic treatments. Despite this, not all cases were fully described, with many of them already in cancer remission with no clear immunosuppression. Most of the studies included patients with a history of negative predictive factors like smoking and older age, which may explain worse outcomes of COVID-19 infection.

In conclusion, although cancer patients with COVID-19 are expected to have a more unsatisfactory outcome, data remains scarce. We are still learning from this outbreak, and international collaboration is necessary to describe better the characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 disease among cancer patients. In this report, we show a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the middle of chemotherapy, presented a mild clinical course of COVID-19 infection. More information is still needed concerning specific cancer types and the impact of chemotherapy on COVID-19.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Corona virus disease 2019

Polymerase chain reaction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-corona virus-2

Twice daily

Positron emission tomographic computed tomography scan

Cluster of differentiation 20

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone and methotrexate

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

García LF. Immune response, inflammation, and the clinical spectrum of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.01441 .

Fung M, Babik JM. COVID-19 in immunocompromised hosts: what we know so far. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(2):340–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa863 .

Zhang L, Zhu F, Xie L, Wang C, Wang J, Chen R, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a retrospective case study in three hospitals within Wuhan, China. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):894–901.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Yang F, Shi S, Zhu J, Shi J, Dai K, Chen X. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of cancer patients with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2067–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25972 .

He W, Chen L, Chen L, Yuan G, Fang Y, Chen W, et al. COVID-19 in persons with haematological cancers. Leukemia. 2020;34(6):1637–45.

Yigenoglu TN, Ata N, Altuntas F, Bascı S, Dal MS, Korkmaz S, Namdaroglu S, Basturk A, Hacıbekiroglu T, Dogu MH, Berber İ, Dal K, Erkurt MA, Turgut B, Ulgu MM, Celik O, Imrat E, Birinci S. The outcome of COVID-19 in patients with hematological malignancy. J Med Virol. 2021 Feb;93(2):1099-104. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.26404 .

Bellmann-Weiler R, Burkert F, Schwaiger T, Schmidt S, Ludescher C, Oexle H, Wolf D, Weiss G. Janus faced course of COVID-19 infection in patients with hematological malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejh.13470 .

Norsa L, Indriolo A, Sansotta N, Cosimo P, Greco S, D’Antiga L. Uneventful course in patients with inflammatory bowel disease during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 outbreak in Northern Italy. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):371–2.

Coperchini F, Chiovato L, Croce L, Magri F, Rotondi M. The cytokine storm in COVID-19: an overview of the involvement of the chemokine/chemokine-receptor system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;53:25–32.

Lee LYW, Cazier J-B, Angelis V, Arnold R, Bisht V, Campton NA, et al. COVID-19 mortality in patients with cancer on chemotherapy or other anticancer treatments: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1919–26.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Infectious Diseases and Family Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Owrang Eilami

Department of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases, Central Institute, Hospital das Clínicas, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Max Igor Banks Ferreira Lopes

Associate Professor of Infectious Diseases, Hospital das Clínicas,, School of Medicine, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Ronaldo Cesar Borges Gryschek

Department of Family Medicine, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Kaveh Taghipour

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Case history, patient data, lab data and radiological images collected by: OE, MIBFL, RCBG; Manuscript written by: OE and KT; Editing: OE and KT; All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kaveh Taghipour .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

Additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Eilami, O., Lopes, M.I.B.F., Gryschek, R.C.B. et al. A case report of COVID-19 in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. BMC Infect Dis 21 , 809 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06472-2

Download citation

Received : 16 April 2021

Accepted : 01 July 2021

Published : 12 August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06472-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Immunosuppressed

BMC Infectious Diseases

ISSN: 1471-2334

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2017

Primary adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature

- Nanik Ram 1 ,

- Owais Rashid 1 ,

- Saad Farooq 2 ,

- Imran Ulhaq 1 &

- Najmul Islam 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 11 , Article number: 108 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

5036 Accesses

16 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Lymphomas are cancers that arise from the white blood cells and have been traditionally divided into two large subtypes: Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. B-cell lymphoma is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma; almost 85% of patients with lymphoma have this variant. Lymphomas can potentially arise from any lymphoid tissue located in the body; however, primary adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma is extremely rare. We report the history, examination findings, and laboratory results of a 50-year-old man diagnosed with a primary left adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old Pakistani man presented to our hospital with progressively increasing pain and fullness in the left upper quadrant of his abdomen, generalized weakness, easy fatigability, and decreased appetite of 1.5 months’ duration. On examination, he had a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg with no postural drop, a pulse rate of 106 beats/minute, and no fever. His past medical history was significant for pulmonary tuberculosis 2 years earlier, for which he received antituberculous therapy. Computed tomography revealed a heterogeneous enhancing soft tissue density mass in the left adrenal gland. It measured 7.1 × 5.6 × 9.5 cm. Further laboratory workup revealed the following levels: sodium 135 mEq/L, potassium 4.5 mEq/L, lactate dehydrogenase 905 IU/L, renin 364 IU/ml, aldosterone 5.79 ng/dl, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate 79.20 μg/dl, urinary vanillylmandelic acid 6.4 mg/24 hours, and a low-dose overnight dexamethasone suppression test result of 3.20 μg/dl. The patient underwent left adrenalectomy. Histopathological test results showed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Immunohistochemical stains were strongly positive for CD20 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1. The patient’s Ki-67 (Mib-1) index was approximately 80%. He received a total of six cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone chemotherapy (rituximab was not given, owing to financial constraints) and was routinely followed pre- and postchemotherapy at our hematology clinic with complete blood count and serum lactate dehydrogenase evaluations. The patient responded to chemotherapy and is currently doing well.

Conclusions

Primary adrenal lymphoma is an extremely rare but rapidly progressive disease. It generally carries a poor prognosis, partly because an optimal treatment protocol has not yet been established. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to establish the best treatment option and increase overall survival.

Peer Review reports

The American Cancer Society estimated that more than 70,000 new cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) would be diagnosed in 2016 [ 1 , 2 ]. Although lymphomas arise mainly from lymph nodes, primary extranodal NHL occurs in at least 25% of the cases [ 3 ]. The adrenal gland can be secondarily involved in around 4% of the patients; however, primary adrenal NHL is extremely rare and accounts for less than 1% of all NHL cases [ 4 ]. Primary adrenal lymphoma (PAL) is histologically proven lymphoma of one or both adrenal glands in patients with no prior history of lymphoma. If other organs or lymph nodes besides the adrenal glands are involved, the adrenal lesion must be unequivocally dominant [ 5 ].

PAL occurs predominantly in males in the sixth to seventh decades of life. Most commonly, this lymphoma is a nongerminal center-type diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which is present in 70% to 80% of the patients [ 6 ]. Patients present with abdominal or lumbar pain; fever; weight loss; and signs of adrenal insufficiency such as hypotension, hyponatremia, fatigue, skin hyperpigmentation, and vomiting [ 7 ]. In occasional instances, it may also be an incidental finding on imaging studies obtained for other purposes, and it is frequently bilateral and bulky at the time of presentation. Several etiological factors, such as Epstein-Barr virus infection, genetic defects in p53 and c-kit, and immune dysregulation, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of this disease [ 5 , 7 ]. Laboratory investigations often show elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), β 2 -microglobulin, C-reactive protein, and ferritinemia, which signify high levels of inflammation associated with PAL [ 6 ].

The prognosis of this condition is generally considered to be poor because PAL is an aggressive disease and progresses rapidly. An average 1-year survival as low as 20% has been reported; however, owing to the rare nature of this disease, prognostic factors are difficult to elucidate [ 5 ].

A 50-year-old Pakistani man known to have had diabetes for 21 years presented to our hospital with progressively increasing pain and fullness in the left upper quadrant of his abdomen, generalized weakness, easy fatigability, and decreased appetite of 1.5 months’ duration. He also complained of nausea and early satiety and had a weight loss of 8 kg over this period. On examination, he was found to have a blood pressure of 140/80 mmHg with no postural drop, a pulse rate of 106 beats/minute, and no fever. His physical examination was otherwise unremarkable. His past medical history was significant for pulmonary tuberculosis 2 years earlier, for which he received antituberculous therapy.

The patient had initially presented at another university hospital 3 weeks earlier. At that time, a laboratory workup and computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen with contrast enhancement were done. Although the results of his complete blood count and renal function test were normal, CT of the abdomen showed a heterogeneous enhancing soft tissue density mass in the left adrenal gland. The mass measured 7.1 × 5.6 cm in transverse and anteroposterior diameter, and the craniocaudal extent of the mass was 9.5 cm. Medially, the mass was abutting the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries, and posteroinferiorly, it was bordering the renal vessels. Paraaortic lymphadenopathy was also present, with the largest one measuring 1.6 cm (Fig. 1 ).

Computed tomography of the patient showing a large left adrenal mass

Further laboratory workup revealed the following levels: sodium 135 mEq/L, potassium 4.5 mEq/L, LDH 905 IU/L, renin 364 IU/ml, aldosterone 5.79 ng/dl, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate 79.20 μg/dl, urinary vanillylmandelic acid 6.4 mg/24 hours, and a low-dose overnight dexamethasone suppression test result of 3.20 μg/dl. The patient was referred to our urology clinic for surgical removal of his mass. He underwent a left adrenalectomy at the urology clinic on 4 March 2016. Histopathological analysis revealed DLBCL (Figs. 2 and 3 ). The results of immunohistochemical stains were strongly positive for CD20 and negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, and cyclin D1. His Ki-67 (Mib-1) index was approximately 80% (Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Low-power view of the lesion showing diffuse sheets of neoplastic cells (hematoxylin and eosin stain)

High-power view of the lesion showing large-sized neoplastic cells with pleomorphic nuclei, variably prominent nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. Frequent mitotic figures are also noted (hematoxylin and eosin stain)

CD20 immunohistochemical stain (pan-B) is strongly positive for neoplastic cells

Ki-67 immunohistochemical stain highlights a markedly raised proliferative index in the neoplastic lymphoid population

For further management, the patient was referred to our hematology clinic and was planned for a rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy regimen starting on 18 March 2016. He received a total of six cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP; rituximab was not given, owing to financial constraints) and was routinely followed pre- and postchemotherapy at the hematology clinic with complete blood count and serum LDH evaluations. Positron emission tomography (PET) performed on 24 March 2016 showed metabolically active residual disease over the left adrenal bed. Subcentimetric fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) deposits were seen in the patient’s L5, L2, and T12 vertebrae, suggestive of marrow infiltration. No evidence of hypermetabolic nodal, hepatic, or splenic involvement was appreciated. However, the patient responded to chemotherapy and is currently doing well. He gained around 8 kg of weight and is following his routine daily activities. A recent PET scan revealed that the previously seen hypermetabolic foci along the left crus, left proximal paraaortic region, and foci of FDG uptake in the lumbar and thoracic vertebrae were not appreciable. The patient’s Deauville 5-point scale score was 0 (complete metabolic response).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing a case of primary adrenal NHL in Pakistan. Our patient was a man in his fifth decade of life, which, on the basis of published literature, is a relatively young age to have this disease. We treated our patient with a regimen of CHOP; rituximab was not included, owing to financial constraints. Even without rituximab, our patient showed a complete response to therapy. Because primary adrenal NHL is a rare disease, optimal treatment has not yet been established. CHOP or CHOP-like regimens were traditionally used before the introduction of rituximab, with generally dismal results (overall survival between 20% and 50%) [ 7 ]. In the largest study to date on PAL, involving 31 patients given an R-CHOP chemotherapy regimen, complete remission and overall response rates were 54.8% and 87.0%, respectively. Surprisingly, no difference was found in overall survival between unilateral and bilateral NHL of the adrenal gland [ 8 ]. Our patient also underwent adrenalectomy; however, the two largest studies to date showed no survival benefit in patients who underwent adrenalectomy as compared with those who were treated with chemotherapy alone [ 6 , 8 ].

In another study involving 28 patients with PAL, 64% of the patients were treated with a CHOP regimen, 50% with an R-CHOP regimen, and 18% had chemotherapy with doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone. The overall survival was 61.6%; however, it was 100% for those who received autologous stem cell transplants, which suggests that this may prolong survival [ 6 ]. The Ki-67 index was high in our patient (80%). Ichikawa et al . reported this index to be greater than 70% in seven patients with primary adrenal DLBCL. They treated all of these patients with rituximab-containing chemotherapy and reported a 2-year survival rate of 57%, although none of the patients died as a result of advancement of lymphoma [ 9 ]. These authors suggested that rituximab-containing chemotherapy with central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis with methotrexate may be a good treatment option for primary adrenal NHL. Kim et al . reported CNS relapses or progression in four patients, none of whom had received intrathecal prophylaxis [ 8 ].

For our patient, we opted for CT as the initial imaging modality and then confirmed the diagnosis via histology of the resected adrenal gland. Grigg et al . suggested that though magnetic resonance imaging and CT findings can be highly suggestive of NHL, a biopsy should be done for diagnosis. Staging should involve a PET or gallium scan, and in patients with elevated LDH levels, a lumbar puncture should also be done [ 7 ].

According to the International Prognostic Index (IPI), our patient was in the low- to intermediate-risk category, which has an estimated 5-year survival of 51%. However, this scoring system is not specific to PAL; thus, it may be inaccurate in predicting overall survival. Kim et al . found that neither high-risk IPI score nor advanced-stage disease according to the Ann Arbor system had any impact on the overall survival; therefore, they suggested a modified IPI scoring system and a revised staging system, which resulted in significantly improved predictability of overall survival [ 9 ]. The modified scoring and staging criteria may prove beneficial in risk stratification of patients with primary adrenal NHL and also guide treatment.

No protocol for specific treatment in cases of a primary adrenal NHL has yet been established, and multiple authors have used a combination of modalities, including surgery and chemotherapy. Ichikawa et al . argued that perhaps one of the reasons for the poor prognosis is that many patients were previously treated with chemotherapy not containing rituximab and did not receive CNS prophylaxis, which may have decreased overall survival [ 9 ].

PAL is a rare but rapidly progressing disease that should be treated aggressively. Rituximab-containing chemotherapy such as R-CHOP has shown promise by increasing the overall survival of patients with this disease. R-CHOP combined with CNS prophylaxis and autologous stem cell transplant may further increase overall survival, but further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to establish the best treatment option and decide whether surgery and radiation have a role in the management of PAL.

Abbreviations

Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

Central nervous system

Computed tomography

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Fluorodeoxyglucose

International Prognostic Index

Lactate dehydrogenase

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- Primary adrenal lymphoma

Positron emission tomography

Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone

Vinjamaram S, Estrada-Garcia DA, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: practice essentials [updated 22 Sep 2016]. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/203399-overview . Accessed 30 Sep 2016.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016. https://old.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-047079.pdf . Accessed 6 Jul 2016.

Google Scholar

Kashyap R, Mittal B, Manohar K, Harisankar C, Bhattacharya A, Singh B, et al. Extranodal manifestations of lymphoma on [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT: a pictorial essay. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11:166–74.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Metser U, Goor O, Lerman H, Naparstek E, Even-Sapir E. PET-CT of extranodal lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:1579–86.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rashidi A, Fisher SI. Primary adrenal lymphoma: a systematic review. Ann Hematol. 2013;92:1583–93.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Laurent C, Casasnovas O, Martin L, Chauchet A, Ghesquieres H, Aussedat G, et al. Adrenal lymphoma: presentation, management and prognosis. QJM. 2017;110:103–9.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Grigg AP, Connors JM. Primary adrenal lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2003;4:154–60.

Kim YR, Kim JS, Min YH, Hyunyoon D, Shin HJ, Mun YC, et al. Prognostic factors in primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of adrenal gland treated with rituximab-CHOP chemotherapy from the Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL). J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:49.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ichikawa S, Fukuhara N, Inoue A, Katsushima H, Ohba R, Katsuoka Y, et al. Clinicopathological analysis of primary adrenal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: effectiveness of rituximab-containing chemotherapy including central nervous system prophylaxis. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2:19.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Sabeeh Siddique for providing the histological figures with explanations.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, because no datasets were generated or analyzed during the present study.

Authors’ contributions

NR conceived of the study and helped to draft the manuscript. OR and SF were involved in patient care and helped write the case presentation. IU and NI also helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, Section of Endocrinology, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Nanik Ram, Owais Rashid, Imran Ulhaq & Najmul Islam

Aga Khan University, Stadium Road, Karachi, Pakistan

Saad Farooq

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Owais Rashid .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ram, N., Rashid, O., Farooq, S. et al. Primary adrenal non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 11 , 108 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1271-x

Download citation

Received : 10 November 2016

Accepted : 21 March 2017

Published : 15 April 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1271-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Adrenal mass

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Clinical analysis of 20 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and autoimmune hemolytic anemia

A retrospective study.

Editor(s): Bush., Eric

Department of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi, PR China.

∗Correspondence: Ji-cheng Zhou, Department of Hematology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, 6 Shuang Yong Road, Nanning 530021, Guangxi, PR China (e-mail: [email protected] ).

Abbreviations: AIHA = autoimmune hemolytic anemia, AIHA/NHL = AIHA associated NHL, AITL = angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, BCL-U = B-cell lymphoma-unclassified, BMB = bone marrow biopsy, BMS = bone marrow smears, CLL/SLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocyte lymphoma, CR = complete remission, LBMI = lymphoma bone marrow infiltration, MCL = mantle cell lymphoma, MZBL = marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, NHL = non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, PR = partial remission.

How to cite this article: Zhou Jc, Wu Mq, Peng Zm, Zhao Wh, Bai Zj. Clinical analysis of 20 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and autoimmune hemolytic anemia: a retrospective study. Medicine . 2020;99:7(e19015).

This work was supported by research grants from National Natural science of China (Grant No.81700172), Guangxi Natural Science Foundations (Grant No.2016GXNSFBA380059) and Medical and Health Suitable Technology Development and Application Project of Guangxi (Grant No. S201685).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.