- Home div.mega__menu -->

- Guiding Principles

- Assessment Cycle

- Equity in Assessment

- FAQs About Assessment

- Learning Outcomes & Evidence

- Undergraduate Learning Goals & Outcomes

- University Assessment Reports

- Program Assessment Reports

- University Survey Reports

- Assessment in Action

- Internal Assessment Grant

- Celebrating Assessment at LMU

- Assessment Advisory Committee

- Workshops & Events

- Assessment Resources

- Recommended Websites

- Recommended Books

- Contact div.mega__menu -->

Oral Presentation Example Rubric

Oral Presentation Example Rubric Outcome: Students will graduate with the ability to give professional presentations. Work Product: Oral presentation

| Outcome/Skills | Advanced | Developing | Emerging |

| Idea development, use of language, and the organization of ideas are effectively used to achieve a purpose. | A. Ideas are clearly organized, developed, and supported to achieve a purpose; the purpose is clear. B. The introduction gets the attention of the audience. C. Main points are clear and organized effectively. D. Supporting material is original, logical, and relevant (facts, examples, etc.). E. Smooth transitions are used. F. The conclusion is satisfying. G. Language choices are vivid and precise. H. Material is developed for an oral rather than a written presentation. | A. The main idea is evident, but the organizational structure may need to be strengthened; ideas may not always flow smoothly. B. The introduction may not be well-developed. C. Main points are not always clear. D. Supporting material may lack in originality or adequate development. E. Transitions may be awkward. F. The conclusion may need additional development. G. Language is appropriate, but word choices are not particularly vivid or precise. | A. Idea “seeds” have not yet germinated; ideas may not be focused or developed; the main purpose is not clear. B. The introduction is undeveloped or irrelevant. C. Main points are difficult to identify. D. Inaccurate, generalized, or inappropriate supporting material may be used. E. Transitions may be needed. F. The conclusion is abrupt or limited. G. Language choices may be limited, peppered with slang or jargon, too complex, or too dull. |

| The nonverbal message supports and is consistent with the verbal message. | A. The delivery is natural, confident, and enhances the message — posture, eye contact, smooth gestures, facial expressions, volume, pace, etc. indicate confidence, a commitment to the topic, and a willingness to communicate. B. The vocal tone, delivery style, and clothing are consistent with the message. C. Limited filler words (“ums”) are used. D. Clear articulation and pronunciation are used. | A. The delivery generally seems effective—however, effective use of volume, eye contact, vocal control, etc. may not be consistent; some hesitancy may be observed. B. Vocal tone, facial expressions, clothing and other nonverbal expressions do not detract significantly from the message. C. Filler words are not distracting. D. Generally, articulation and pronunciation are clear.

| A. The delivery detracts from the message; eye contact may be very limited; the presenter may tend to look at the floor, mumble, speak inaudibly, fidget, or read most or all of the speech; gestures and movements may be jerky or excessive. B. The delivery may appear inconsistent with the message. C. Filler words (“ums,”) are used excessively. D. Articulation and pronunciation tend to be sloppy. |

| Idea development, use of language, and the organization of ideas for a specific audience, setting, and occasion are appropriate. | A. Language is familiar to the audience, appropriate for the setting, and free of bias; the presenter may “code-switch” (use a different language form) when appropriate. B. Topic selection and examples are interesting and relevant for the audience and occasion. C. Delivery style and clothing choices suggest an awareness of expectations and norms. | A. Language used is not disrespectful or offensive. B. Topic selection and examples are not inappropriate for the audience, occasion, or setting; some effort to make the material relevant to audience interests, the occasion, or setting is evident. C. The delivery style, tone of voice, and clothing choices do not seem out-of-place or disrespectful to the audience. | A. Language is questionable or inappropriate for a particular audience, occasion, or setting. Some biased or unclear language may be used. B. Topic selection does not relate to audience needs and interests. C. The delivery style may not match the particular audience or occasion—the presenter’s tone of voice or other mannerisms may create alienation from the audience; clothing choices may also convey disrespect for the audience. |

Rubric is a modification of one presented by: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. (1998). Oral presentation rubric . Retrieved October 23, 2008 from http://www.nwrel.org/assessment/pdfRubrics/oralassess.PDF

Creating an Oral Presentation Rubric

In-class activity.

This activity helps students clarify the oral presentation genre; do this after distributing an assignment–in this case, a standard individual oral presentation near the end of the semester which allows students to practice public speaking while also providing a means of workshopping their final paper argument. Together, the class will determine the criteria by which their presentations should–and should not–be assessed.

Guide to Oral/Signed Communication in Writing Classrooms

To collaboratively determine the requirements for students’ oral presentations; to clarify the audience’s expectations of this genre

rhetorical situation; genre; metacognition; oral communication; rubric; assessment; collaboration

- Ask students to free-write and think about these questions: What makes a good oral presentation? Think of examples of oral presentations that you’ve seen, one “bad” and one “good.” They can be from any genre–for example, a course lecture, a museum talk, a presentation you have given, even a video. Jot down specific strengths and weaknesses.

- Facilitate a full-class discussion to list the important characteristics of an oral presentation. Group things together. For example, students may say “speaking clearly” as a strength; elicit specifics (intonation, pace, etc.) and encourage them to elaborate.

- Clarify to students that the more they add to the list, the more information they have in regards to expectations on the oral presentation rubric. If they do not add enough, or specific enough, items, they won’t know what to aim for or how they will be assessed.

- Review the list on the board and ask students to decide what they think are the most important parts of their oral presentations, ranking their top three components.

- Create a second list to the side of the board, called “Let it slide,” asking students what, as a class, they should “let slide” in the oral presentations. Guide and elaborate, choosing whether to reject, accept, or compromise on the students’ proposals.

- Distribute the two lists to students as-is as a checklist-style rubric or flesh the primary list out into a full analytic rubric .

Here’s an example of one possible rubric created from this activity; here’s another example of an oral presentation rubric that assesses only the delivery of the speech/presentation, and which can be used by classmates to evaluate each other.

| — Follow us on .

PowerPoint Rubric

* Primary sources can include original letters and diaries, personal observations, interviews, first-hand accounts, newspaper articles, magazine articles, journal articles, Web pages, audio recordings, video productions and photography. Examples of Other Rubrics

Presentation Rubric for a College Project We seem to have an unavoidable relationship with public speaking throughout our lives. From our kindergarten years, when our presentations are nothing more than a few seconds of reciting cute words in front of our class…  ...till our grown up years, when things get a little more serious, and the success of our presentations may determine getting funds for our business, or obtaining an academic degree when defending our thesis.  By the time we reach our mid 20’s, we become worryingly used to evaluations based on our presentations. Yet, for some reason, we’re rarely told the traits upon which we are being evaluated. Most colleges and business schools for instance use a PowerPoint presentation rubric to evaluate their students. Funny thing is, they’re not usually that open about sharing it with their students (as if that would do any harm!). What is a presentation rubric?A presentation rubric is a systematic and standardized tool used to evaluate and assess the quality and effectiveness of a presentation. It provides a structured framework for instructors, evaluators, or peers to assess various aspects of a presentation, such as content, delivery, organization, and overall performance. Presentation rubrics are commonly used in educational settings, business environments, and other contexts where presentations are a key form of communication. A typical presentation rubric includes a set of criteria and a scale for rating or scoring each criterion. The criteria are specific aspects or elements of the presentation that are considered essential for a successful presentation. The scale assigns a numerical value or descriptive level to each criterion, ranging from poor or unsatisfactory to excellent or outstanding. Common criteria found in presentation rubrics may include:

“We’re used to giving presentations, yet we’re rarely told the traits upon which we’re being evaluated. Well, we don’t believe in shutting down information. Quite the contrary: we think the best way to practice your speech is to know exactly what is being tested! By evaluating each trait separately, you can:

I’ve assembled a simple Presentation Rubric, based on a great document by the NC State University, and I've also added a few rows of my own, so you can evaluate your presentation in pretty much any scenario! CREATE PRESENTATIONWhat is tested in this powerpoint presentation rubric. The Rubric contemplates 7 traits, which are as follows:  Now let's break down each trait so you can understand what they mean, and how to assess each one: Presentation Rubric How to use this Rubric?:The Rubric is pretty self explanatory, so I'm just gonna give you some ideas as to how to use it. The ideal scenario is to ask someone else to listen to your presentation and evaluate you with it. The less that person knows you, or what your presentation is about, the better. WONDERING WHAT YOUR SCORE MAY INDICATE?

As we don't always have someone to rehearse our presentations with, a great way to use the Rubric is to record yourself (this is not Hollywood material so an iPhone video will do!), watching the video afterwards, and evaluating your presentation on your own. You'll be surprised by how different your perception of yourself is, in comparison to how you see yourself on video.  Related read: Webinar - Public Speaking and Stage Presence: How to wow? It will be fairly easy to evaluate each trait! The mere exercise of reading the Presentation Rubric is an excellent study on presenting best practices. If you're struggling with any particular trait, I suggest you take a look at our Academy Channel where we discuss how to improve each trait in detail! It's not always easy to objectively assess our own speaking skills. So the next time you have a big presentation coming up, use this Rubric to put yourself to the test! Need support for your presentation? Build awesome slides using our very own Slidebean . Related videoUpcoming eventsHow to close a funding round, financial modeling bootcamp, popular articles.  Slidebean Helped USports Tackle A Complex Financial Model 35+ Best Startup Pitch Deck Examples + Free PDF downloads Let’s move your company to the next stage 🚀Ai pitch deck software, pitch deck services.  Financial Model Consulting for Startups 🚀 Raise money with our pitch deck writing and design service 🚀 The all-in-one pitch deck software 🚀 This guide explores top companies like Slidebean, 4th and King, Slide Genius, Sketch Deck, and Canva, comparing their strengths, drawbacks, and pricing to help you make an informed decision. Discover why Slidebean is the industry’s preferred choice and the best pitch deck company.  This article will guide you on creating effective pitch deck slides, including essential do’s and don’ts, common red flags, must-haves, and real-life examples from companies that have successfully raised venture capital.  This is a functional model you can use to create your own formulas and project your potential business growth. Instructions on how to use it are on the front page.  Book a call with our sales teamIn a hurry? Give us a call at Rubric Best Practices, Examples, and TemplatesA rubric is a scoring tool that identifies the different criteria relevant to an assignment, assessment, or learning outcome and states the possible levels of achievement in a specific, clear, and objective way. Use rubrics to assess project-based student work including essays, group projects, creative endeavors, and oral presentations. Rubrics can help instructors communicate expectations to students and assess student work fairly, consistently and efficiently. Rubrics can provide students with informative feedback on their strengths and weaknesses so that they can reflect on their performance and work on areas that need improvement. How to Get StartedBest practices, moodle how-to guides.

Step 1: Analyze the assignmentThe first step in the rubric creation process is to analyze the assignment or assessment for which you are creating a rubric. To do this, consider the following questions:

Step 2: Decide what kind of rubric you will useTypes of rubrics: holistic, analytic/descriptive, single-point Holistic Rubric. A holistic rubric includes all the criteria (such as clarity, organization, mechanics, etc.) to be considered together and included in a single evaluation. With a holistic rubric, the rater or grader assigns a single score based on an overall judgment of the student’s work, using descriptions of each performance level to assign the score. Advantages of holistic rubrics:

Disadvantages of holistic rubrics:

Analytic/Descriptive Rubric . An analytic or descriptive rubric often takes the form of a table with the criteria listed in the left column and with levels of performance listed across the top row. Each cell contains a description of what the specified criterion looks like at a given level of performance. Each of the criteria is scored individually. Advantages of analytic rubrics:

Disadvantages of analytic rubrics:

Single-Point Rubric . A single-point rubric is breaks down the components of an assignment into different criteria, but instead of describing different levels of performance, only the “proficient” level is described. Feedback space is provided for instructors to give individualized comments to help students improve and/or show where they excelled beyond the proficiency descriptors. Advantages of single-point rubrics:

Disadvantage of analytic rubrics: Requires more work for instructors writing feedback Step 3 (Optional): Look for templates and examples.You might Google, “Rubric for persuasive essay at the college level” and see if there are any publicly available examples to start from. Ask your colleagues if they have used a rubric for a similar assignment. Some examples are also available at the end of this article. These rubrics can be a great starting point for you, but consider steps 3, 4, and 5 below to ensure that the rubric matches your assignment description, learning objectives and expectations. Step 4: Define the assignment criteriaMake a list of the knowledge and skills are you measuring with the assignment/assessment Refer to your stated learning objectives, the assignment instructions, past examples of student work, etc. for help. Helpful strategies for defining grading criteria:

Step 5: Design the rating scaleMost ratings scales include between 3 and 5 levels. Consider the following questions when designing your rating scale:

Step 6: Write descriptions for each level of the rating scaleArtificial Intelligence tools like Chat GPT have proven to be useful tools for creating a rubric. You will want to engineer your prompt that you provide the AI assistant to ensure you get what you want. For example, you might provide the assignment description, the criteria you feel are important, and the number of levels of performance you want in your prompt. Use the results as a starting point, and adjust the descriptions as needed. Building a rubric from scratchFor a single-point rubric , describe what would be considered “proficient,” i.e. B-level work, and provide that description. You might also include suggestions for students outside of the actual rubric about how they might surpass proficient-level work. For analytic and holistic rubrics , c reate statements of expected performance at each level of the rubric.

Well-written descriptions:

Step 7: Create your rubricCreate your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle. Rubric creators: Rubistar , iRubric Step 8: Pilot-test your rubricPrior to implementing your rubric on a live course, obtain feedback from:

Try out your new rubric on a sample of student work. After you pilot-test your rubric, analyze the results to consider its effectiveness and revise accordingly.

Example of an analytic rubric for a final paper

Example of a holistic rubric for a final paper

Single-Point Rubric

More examples:

Technology Tools: Rubrics in Moodle

Tools with rubrics (other than Moodle)

Other resources

Grading RubricsA rubric, or “a matrix that provides levels of achievement for a set of criteria” (Howell, 2014), is a common tool for assessing open-response or creative work (writing, presentations, performances, etc.). To use rubrics effectively, instructors should understand their benefits, the types and uses of rubrics, and their limitations. Benefits of RubricsThe criteria identified in the matrix differs with the subject matter, the nature of the assignment, and learning objectives, but all rubrics serve three purposes.

Types of RubricsThere are two basic types of rubrics. Holistic rubrics provide an overall description of work at various levels of achievement. For instance, separate paragraphs might describe “A,” “B”, “C,” and “D” -level papers. A holistic rubric might help instructors communicate the interrelationships of the elements of an assignment. For instance, students should understand that a fully persuasive research paper not only has strong argument and evidence but is also free of writing errors. These rubrics offer structure but also afford flexibility and judgment in grading.  Holistic Rubric Template

Analytic rubrics provide more detailed descriptions of achievement levels of distinct components of the assignment. For instance, the components of thesis, evidence, coherence, and writing mechanics might each be described with two to three sentences at each of the achievement levels. Such rubrics help instructors and students isolate discrete skills and performance. These rubrics limit the grader’s discretion and potentially offer greater consistency. Analytic Rubric Template

Whether designing a holistic or analytic rubric, the descriptions of student achievement levels should incorporate common student mistakes. This saves time as it reduces the need for long-hand feedback that is time-consuming and often hard for students to read (Stevens and Levi, 2013). For either type of rubric, the achievement level may be indicated with evaluative shorthand (e.g., Excellent, Good, Fair, Poor) or grade labels (A, B, C, D). In many cases, rubrics also provide the point totals possible with overall level (holistic) or each component (analytic). Using RubricsDeveloping a rubric requires identifying and weighing the different elements of an assignment. The relative weight given to any category should reflect the learning objectives. For instance, if the learning objectives focus on interpreting and using evidence, the weight of the grade should not fall on rudimentary skills, like grammar and syntax. At the same time, rubrics can help instructors articulate and implement developmental goals. For example, using the same elements for two or more iterations of an assignment, the rubric for an earlier submission can place more weight on writing mechanics, while more weight can be placed on higher-order skills for a later submission. Rubrics can be used as summative or formative assessment . Used as summative assessment, rubrics give concrete rationale for the grade that students receive. Used as formative assessment, rubrics help both instructors and students monitor the areas in which students are succeeding and struggling. For best use of rubrics as formative assessment, grading should be accompanied by clear, improvement-oriented feedback (Wylie et al., 2013). Additionally, instructors can require students to use the rubric as a checklist that they turn in with their work. This may help students better monitor the quality of their work before submitting it (Treme, 2017). Technology can aid in developing and using rubrics. Canvas provides a rubric generator function that gives options for assigning point value, adding comments, and describing criteria for the assignment. To access it, go to the “assignments” page, click on the assignment, and select “add rubric.” A technologically-developed rubric like those in Canvas ensures greater consistency in assigning grades (Moyer, 2015). LimitationsNo rubric is a complete substitute for reasoned judgment. While instructors strive to remove arbitrariness in grading, expert discernment is always an ingredient in assessment. Despite their air of objectivity, rubrics involve significant subjectivity—for instance, in the decisions about the relative weight or the descriptions of elements of student work. Nor are rubrics a “silver bullet” for achieving high academic performance. Baseline knowledge and prior academic performance are still greater factors in student achievement (Howell, 2014: 406). Nonetheless, rubrics are a useful tool for promoting consistency, transparency, and objectivity and can have positive outcomes for instructors and students. Howell, R. J. (2014). Grading rubrics: Hoopla or help? Innovations in Education and Teaching International , 51 (4): 400-410. Kryder, L. G. (2003). Grading for speed, consistency, and accuracy. Business Communications Quarterly , 66 (1): 90-93. Moyer, Adam C., William A. Young II, Gary R. Weckman, Red C. Martin, and Ken W. Cutright. “Rubrics on the Fly: Improving Efficiency and Consistency with a Rapid Grading and Feedback System.” Journal of Teaching and Learning with Technology , 4, no. 2 (2015): 6-29. Stevens, D., & Levi, A. (2013). Introduction to rubrics: an assessment tool to save grading time, convey effective feedback, and promote student learning (Second edition.). Sterling, Virginia: Stylus. Treme, Julianne. “An Op-Ed Grading Rubric: Improving Student Output and Professor Happiness.” NACTA Journal , 61, no. 2 (2017): 181-183. White, Krista Alaine, and Ella Thomas Heitzler. “Effects of Increased Evaluation Objectivity on Grade Inflation: Precise Grading Rubrics and Rigorously Developed Tests.” Nurse Educator , 43, no. 2 (2018): 73-77. Wylie, Caroline and Christine Lyon. “Using the Formative Rubrics, Reflection and Observation Tools to Support Professional Reflection on Practice.” Formative Assessment for Teachers and Students (2013).  Academy for Teaching and LearningMoody Library, Suite 201 One Bear Place Box 97189 Waco, TX 76798-7189

Center for Excellence in TeachingHome > Resources > Group presentation rubric Group presentation rubricThis is a grading rubric an instructor uses to assess students’ work on this type of assignment. It is a sample rubric that needs to be edited to reflect the specifics of a particular assignment. Students can self-assess using the rubric as a checklist before submitting their assignment. Download this file Download this file [63.74 KB] Back to Resources Page Oral Presentation RubricSelect the box which most describes student performance. Alternatively you can "split the indicators" by using the boxes before each indicator to evaluate each item individually.

Mailing AddressPomona College 333 N. College Way Claremont , CA 91711 Get in touchGive back to pomona. Part of The Claremont Colleges Rubric for Evaluating Student Presentations

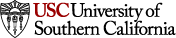

Make Assessing Easier with a RubricThe rubric that you use to assess your student presentations needs to be clear and easy to read by your students. A well-thought out rubric will also make it easier to grade speeches. Before directing students to create a presentation, you need to tell them how they will be evaluated with the rubric. For every rubric, there are certain criteria listed or specific areas to be assessed. For the rubric download that is included, the following are the criteria: content, eye contact, volume and clarity, flow, confidence and attitude, visual aids, and time. Student Speech Presentation Rubric Download Assessment Tool Explained in Detail Content : The information in the speech should be organized. It should have an engaging introduction that grabs the audience’s attention. The body of the speech should include details, facts and statistics to support the main idea. The conclusion should wrap up the speech and leave the audiences with something to remember. In addition, the speech should be accurate. Teachers should decide how students should cite their sources if they are used. These should be turned in at the time of the speech. Good speakers will mention their sources during the speech. Last, the content should be clear. The information should be understandable for the audience and not confusing or ambiguous. Eye ContactStudents eyes should not be riveted to the paper or note cards that they prepare for the presentation. It is best if students write talking points on their note cards. These are main points that they want to discuss. If students write their whole speech on the note cards, they will be more likely to read the speech word-for-word, which is boring and usually monotone. Students should not stare at one person or at the floor. It is best if they can make eye contact with everyone in the room at least once during the presentation. Staring at a spot on the wall is not great, but is better than staring at their shoes or their papers. Volume and ClarityStudents should be loud enough so that people sitting in the back of the room can hear and understand them. They should not scream or yell. They need to practice using their diaphragm to project their voice. Clarity means not talking too fast, mumbling, slurring or stuttering. When students are nervous, this tends to happen. Practice will help with this problem. When speaking, the speaker should not have distracting pauses during the speech. Sometimes a speaker may pause for effect; this is to tell the audience that what he or she is going to say next is important. However, when students pause because they become confused or forget the speech, this is distracting. Another problem is verbal fillers. Student may say “um,” “er” or “uh” when they are thinking or between ideas. Some people do it unintentionally when they are nervous. If students chronically say “um” or use any type of verbal filler, they first need to be made aware of the problem while practicing. To fix this problem, a trusted friend can point out when they doing during practice. This will help students be aware when they are saying the verbal fillers. Confidence and AttitudeWhen students speak, they should stand tall and exude confidence to show that what they are going to say is important. If they are nervous or are not sure about their speech, they should not slouch. They need to give their speech with enthusiasm and poise. If it appears that the student does not care about his or her topic, why should the audience? Confidence can many times make a boring speech topic memorable. Visual AidsThe visual that a student uses should aid the speech. This aid should explain a facts or an important point in more detail with graphics, diagrams, pictures or graphs. These can be presented as projected diagrams, large photos, posters, electronic slide presentations, short clips of videos, 3-D models, etc. It is important that all visual aids be neat, creative and colorful. A poorly executed visual aid can take away from a strong speech. One of the biggest mistakes that students make is that they do not mention the visual aid in the speech. Students need to plan when the visual aid will be used in the speech and what they will say about it. Another problem with slide presentations is that students read word-for-word what is on each slide. The audience can read. Students need to talk about the slide and/or offer additional information that is not on the slide. The teacher needs to set the time limit. Some teachers like to give a range. For example, the teacher can ask for short speeches to be1-2 minutes or 2-5 minutes. Longer ones could be 10-15 minutes. Many students will not speak long enough while others will ramble on way beyond the limit. The best way for students to improve their time limit is to practice. The key to a good speech is for students to write out an outline, make note cards and practice. The speech presentation rubric allows your students to understand your expectations.

Curriculum & RequirementsIn this section.

Embarking on a liberal arts and sciences education at Puget Sound means engaging in an integrated and demanding introduction to a life of intellectual inquiry. Throughout your academic career, you’ll learn to understand yourself, understand the diversity of intellectual approaches to understanding our world, and increase your awareness of your place in a broader context. Over four years of study, you’ll build a foundation for lifelong learning. Core Curriculum As a student at Puget Sound, you will complete a core curriculum consisting of two first-year seminars in fall and spring, courses in three divisions, interdisciplinary connections courses, courses on knowledge and power, and experiential learning. Your first year experience will introduce you to the academic and collaborative skills you will need to succeed in college, while providing close mentoring to chart your course. You'll begin to explore our divisions of Arts and Humanities, Social Sciences, and Natural Sciences, while learning about power and knowledge production, languages, and engage in an experiential learning program such as study abroad, an internship, and/or summer research. Finally, you’ll go beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries to understand the interrelationship of fields of knowledge by exploring how they form connections to illuminate real-world issues and problems. The First Year Experience

These first-year seminars may not be used to meet major, minor, or emphasis requirements, Divisional requirements, or other core requirements. Students may not enroll in them after fulfilling the requirement. The Continuing Core

A new Core Curriculum for 2024-25At Puget Sound, you don’t just get a major, you get a unique perspective on the world. Our core curriculum is rooted in the tradition of the liberal arts, so no matter what you choose to study, you’ll have opportunities throughout your undergraduate education to explore branches of knowledge you never even knew existed.  Graduation Requirements As a top-tier university, we hold our students to the highest standards of academic excellence. Students who complete the following requirements will be awarded a baccalaureate degree:

*0.67 unit minimum for transfer students. Declaring a Major Each student declares a major by the end of their second year through the Office of Academic Advising and will be responsible for meeting the requirements. An academic major requires a minimum of 8 units within that department or program, of which 4 units must be in residence credit. While a minimum 2.0 cumulative GPA is required to graduate, some departments or programs may require a higher GPA for the completion of a major or minor. In addition to a major, a student may choose to declare more than one major or a minor. An academic minor requires a minimum of 5 units, of which 3 units must be residence credit. Courses graded pass/fail may not be counted toward their minor requirement. Related Links

Core Curriculum and Graduation Requirements Prior to 2024-2025The text below pertains to the previous Core Curriculum and Graduation Requirements for students matriculating prior to the 2024-2025 academic year. As a student at Puget Sound, you will complete a core curriculum consisting of courses from eight core areas of study. Each course counts as one unit toward your eight-unit core requirement. You will first gain a foundational study of college-level writing, speaking, and research practices, while beginning to study five academic approaches to understanding the world. Finally, you’ll go beyond traditional disciplinary boundaries to understand the interrelationship of fields of knowledge by exploring connections between these approaches. Seminar in Scholarly Inquiry (Year 1)

Five Approaches to Knowing (Years 1–3)

Interdisciplinary Experience (Years 3–4)

* Note: The Language Graduation Requirement changed for the 2023-24 academic year. Students on the 2022-23 or prior Bulletins must fulfill their language requirement in one of the following ways:

© 2024 University of Puget Sound 3MT: Three Minute Thesis Eighth AnnualThe graduate college is pleased to sponsor the eighth annual three minute thesis (3mt) competition for graduate-student researchers..

This annual event is an opportunity for students to build their communication skills by creatively describing their research in ways that make it relatable and relevant to a non-specialist audience.One static slide may be used while speaking for up to three minutes. timelines and guidelines are listed below. enjoy the videos of past award winners’ presentations, or an entire final round of competition ..

What is 3MT?Three Minute Thesis (3MT) celebrates the exciting research conducted by master’s or Ph.D. students around the world. Developed by The University of Queensland, the competition cultivates students’ academic, presentation, and research communication skills. Presenting in a 3MT competition increases students' capacity to explain their research in three minutes in a language appropriate to a non-specialist audience. Competitors are allowed one PowerPoint slide, but no other resources or props. EligibilityParticipants must be currently enrolled in a master's or doctoral degree program that requires students to conduct their own research (dissertation or thesis). Three participants will be recognized with awards. The winner of the final competition receives a $500 Ubill scholarship and may be asked to represent the university in other 3MT events. A scholarship of $250 will be awarded to the final competition's Runner Up and People’s Choice Award winner. The Graduate College will also raffle off two travel grants worth $200 each, as well as one U-Bill scholarship worth $200 for participants in their final year of graduate school. Every participant will have the opportunity to cultivate their presentation, research, and academic skills. Judging CriteriaWinners will be determined by a panel of judges using the official 3MT competition rubrics. Judges for the initial heats will be invited from the Iowa State University faculty and staff and the local community. Judges for the final competition will be well-known Iowa constituents. At every level of the competition, each competitor will be assessed on the judging criteria listed below. Each criterion is equally weighted and has an emphasis on audience. Comprehension and Content

Engagement and Communication

Successful competitors will spend adequate time on each element of the presentation without rushing while emphasizing the significance and application of his/her research and leaving the audience wanting to learn more. Presentation FeedbackFor feedback on your 3MT slide or the speech you are planning to incorporate into your 3MT presentation, please make an appointment with a writing consultant at the Center for Communication Excellence. 3MT Committee ( [email protected] ):

Past 3MT Winners2022 awardees.

2022 Final Round Participants

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Beginning Developing Proficient Mastery. 2 3 4. A. Content. Topic lacks relevance or focus; presentation contains multiple fact errors. Topic would benefit from more focus; presentation contains some fact errors or omissions. Topic is adequately focused and relevant; major facts are accurate and generally complete.

The goal of this rubric is to identify and assess elements of research presentations, including delivery strategies and slide design. • Self-assessment: Record yourself presenting your talk using your computer's pre-downloaded recording software or by using the coach in Microsoft PowerPoint. Then review your recording, fill in the rubric ...

Oral Presentation Grading Rubric Name: _____ Overall Score: /40 Nonverbal Skills 4 - Exceptional 3 - Admirable 2 - Acceptable 1 - Poor Eye Contact Holds attention of entire audience with the use of direct eye contact, seldom looking at notes or slides. Consistent use of direct eye

Oral Presentation: Scoring Guide. 4 points - Clear organization, reinforced by media. Stays focused throughout. 3 points - Mostly organized, but loses focus once or twice. 2 points - Somewhat organized, but loses focus 3 or more times. 1 point - No clear organization to the presentation. 3 points - Incorporates several course concepts ...

Example 1: Discussion Class This rubric assesses the quality of student contributions to class discussions. This is appropriate for an undergraduate-level course (Carnegie Mellon). Example 2: Advanced Seminar This rubric is designed for assessing discussion performance in an advanced undergraduate or graduate seminar.

Oral Presentations Scoring Rubric. Oral presentations are expected to completely address the topic and requirements set forth in the assignment, and are appropriate for the intended audience. Oral presentations are expected to provide an appropriate level of analysis, discussion and evaluation as required by the assignment.

Oral Presentation Rubric Criteria Unsuccessful Somewhat Successful Mostly Successful Successful Claim Claim is clearly and There is no claim, or claim is so confusingly worded that audience cannot discern it. Claim is present/implied but too late or in a confusing manner, and/or there are significant mismatches between claim and argument/evidence.

Organization. Logical, interesting, clearly delineated themes and ideas. Generally clear, overall easy for audience to follow. Overall organized but sequence is difficult to follow. Difficult to follow, confusing sequence of information. No clear organization to material, themes and ideas are disjointed. Evaluation.

Example 1: Oral Exam This rubric describes a set of components and standards for assessing performance on an oral exam in an upper-division history course, CMU. Example 2: Oral Communication. Example 3: Group Presentations This rubric describes a set of components and standards for assessing group presentations in a history course, CMU.

Oral Presentation Example Rubric Outcome: Students will graduate with the ability to give professional presentations. Work Product: Oral presentation

Presentation is a planned conversation, paced for audience understanding. ... Rubric for Formal Oral Communication ... M.E., & Freed, J.E. (2000). Learner-centered assessment on college campuses: Shifting the focus from teaching to learning (pp. 156-157). Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, MA. Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence, Carnegie Mellon ...

Create a second list to the side of the board, called "Let it slide," asking students what, as a class, they should "let slide" in the oral presentations. Guide and elaborate, choosing whether to reject, accept, or compromise on the students' proposals. Distribute the two lists to students as-is as a checklist-style rubric or flesh ...

The introduction presents the overall topic and draws the audience into the presentation with compelling questions or by relating to the audience's interests or goals. ... University of Wisconsin - Stout — Schedule of Online Courses, Online Certificate Programs, and Graduate Degree. Readings on Authentic Assessment. Examples of Other Rubrics ...

A typical presentation rubric includes a set of criteria and a scale for rating or scoring each criterion. The criteria are specific aspects or elements of the presentation that are considered essential for a successful presentation. The scale assigns a numerical value or descriptive level to each criterion, ranging from poor or unsatisfactory ...

Oral Presentation Rubric 4—Excellent 3—Good 2—Fair 1—Needs Improvement Delivery • Holds attention of entire audience with the use of direct eye contact, seldom looking at notes • Speaks with fluctuation in volume and inflection to maintain audience interest and emphasize key points • Consistent use of direct eye contact with ...

indicated transitions in presentation topic or focus. Included transitions to connect key points but often used fillers such as um, ah, or like. Included some transitions to connect key points but over reliance on fillers was distracting. Presentation was choppy and disjointed with a lack of structure. Conclusion evaluation but over the 25

Step 7: Create your rubric. Create your rubric in a table or spreadsheet in Word, Google Docs, Sheets, etc., and then transfer it by typing it into Moodle. You can also use online tools to create the rubric, but you will still have to type the criteria, indicators, levels, etc., into Moodle.

A rubric, or "a matrix that provides levels of achievement for a set of criteria" (Howell, 2014), is a common tool for assessing open-response or creative work (writing, presentations, performances, etc.). To use rubrics effectively, instructors should understand their benefits, the types and uses of rubrics, and their limitations. Benefits of Rubrics The criteria identified in the matrix ...

> Group presentation rubric. Group presentation rubric. This is a grading rubric an instructor uses to assess students' work on this type of assignment. It is a sample rubric that needs to be edited to reflect the specifics of a particular assignment. ... University of Southern California Los Angeles, CA 90089-1691 [email protected] (213) 740 ...

Oral Presentation Rubric. Select the box which most describes student performance. Alternatively you can "split the indicators" by using the boxes before each indicator to evaluate each item individually. Effectively uses eye contact. Speaks clearly, effectively and confidently using suitable volume and pace.

Speaker has excellent posture. 10. Eye contact may focus on only one member of the audience or a select few members. Mildly distracting nervous habits are present but do not override the content. 5. Very little eye contact is made with the audience. It may sound like the speaker is reading the presentation.

Rubric adapted by Ethan Brooks-Livingston, Instructor of History, Catawba Valley Community College, as part of the 2021-2022 UNC World View Global Fellows ... Instructional Design and Technology Services, SC&I, Rutgers University, 4/2014 Group Presentation Rubric (Unit 2 Lesson 3) Criteria Unsatisfactory -Beginning Developing Accomplished ...

Example 8 - Poster Presentation Rubric. Characteristics to note in the rubric: Language is descriptive, not evaluative. Labels for degrees of success are descriptive ("Expert" "Proficient", etc.); by avoiding the use of letters representing grades or numbers representing points, there is no implied contract that qualities of the paper will "add ...

The rubric for evaluating student presentations is included as a download in this article. In addition, the criteria on the rubric is explained in detail. The criteria included on this rubric is as follows: content, eye contact, volume and clarity, flow, confidence and attitude, visual aids, and time. In addition, you will find plenty of helpful hints for teachers and students to help make the ...

As a top-tier university, we hold our students to the highest standards of academic excellence. Students who complete the following requirements will be awarded a baccalaureate degree: Complete University Core Requirements. Specific courses satisfying core requirements are listed on Puget Sound's website and in the Bulletin.

Every participant will have the opportunity to cultivate their presentation, research, and academic skills. Judging Criteria. Winners will be determined by a panel of judges using the official 3MT competition rubrics. Judges for the initial heats will be invited from the Iowa State University faculty and staff and the local community.

state's scoring rubric criteria. Rigorously evaluates each application through thorough review of the written proposal, a substantive in-person interview with each qualified applicant, and all appropriate due diligence to examine the applicant's experience and capacity, conducted by knowledgeable and competent evaluators.