- Open access

- Published: 23 June 2022

Menstrual hygiene practices and associated factors among Indian adolescent girls: a meta-analysis

- Jaseela Majeed 1 ,

- Prerna Sharma 2 ,

- Puneeta Ajmera ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6237-2235 3 &

- Koustuv Dalal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7393-796X 4

Reproductive Health volume 19 , Article number: 148 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

12k Accesses

12 Citations

Metrics details

Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) and practices by adolescent females of low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are a severe public health issue. The current systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled proportion of the hygiene practices, menstrual problems with their associated factors, and the effectiveness of educational interventions on menstrual hygiene among adolescent school girls in India.

PRISMA checklist and PICO guidelines were used to screen the scientific literature from 2011 to 2021. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to assess the quality of studies. Four themes were developed for data analysis, including hygiene practices, type of absorbent used, menstruation associated morbidities and interventions performed regarding menstruation. Eighty-four relevant studies were included and a meta-analysis, including subgroup analysis, was performed.

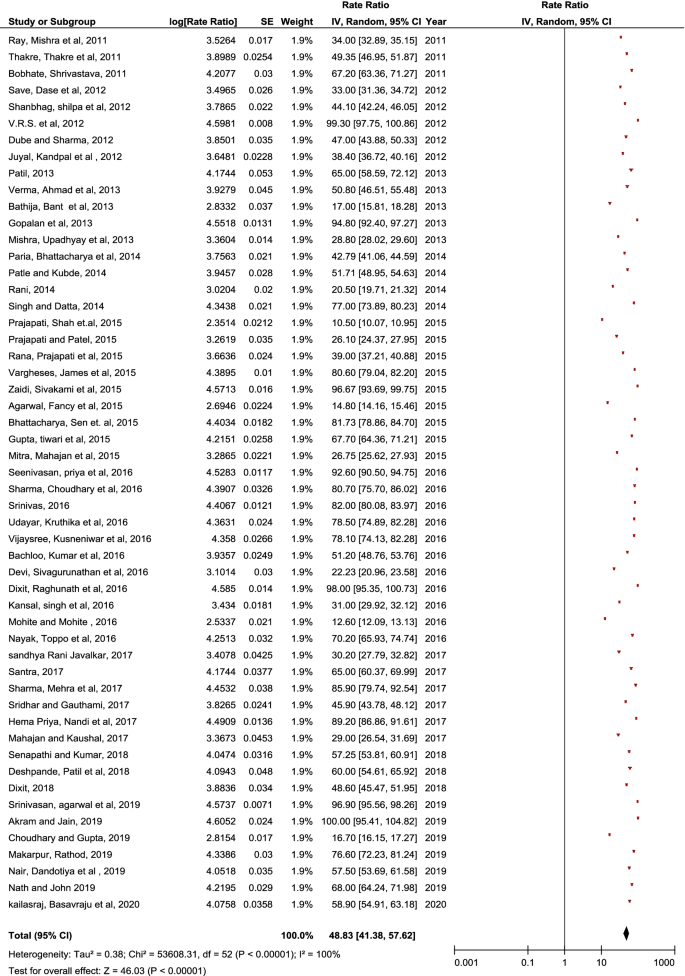

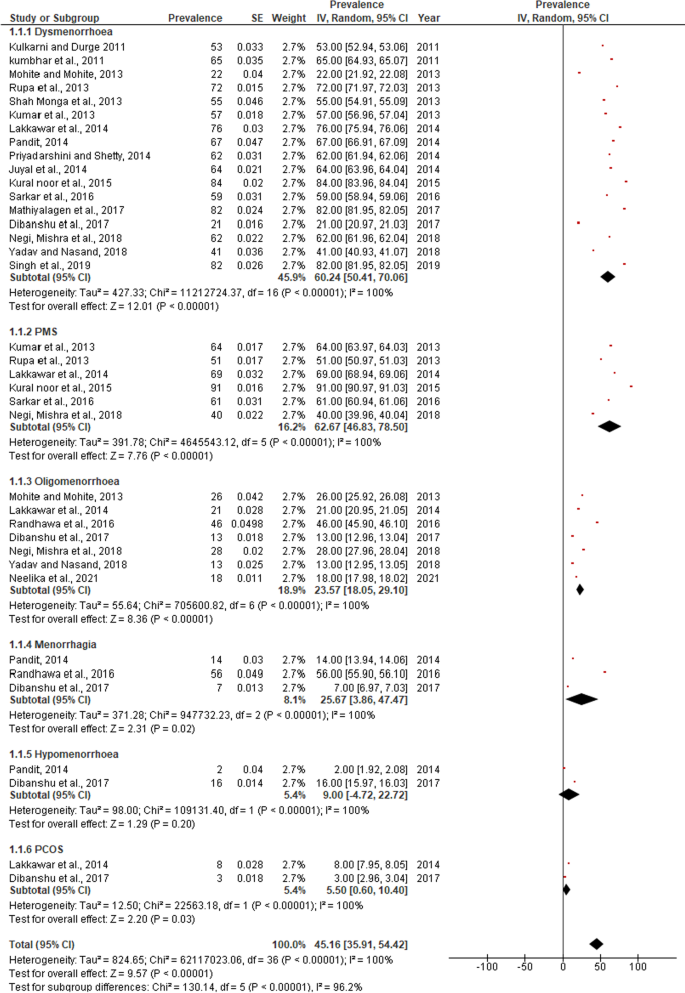

Pooled data revealed a statistically significant increase in sanitary pad usage “(SMD = 48.83, 95% CI = 41.38–57.62, p < 0.00001)” and increased perineum practices during menstruation “(SMD = 55.77, 95% CI = 44.27–70.26, p < 0.00001)”. Results also reported that most prevalent disorders are dysmenorrhea “(SMD = 60.24, 95% CI = 50.41–70.06, p < 0.0001)”, Pre-menstrual symptoms “(SMD = 62.67, 95% CI = 46.83–78.50, p < 0.00001)”, Oligomenorrhea “(SMD = 23.57, CI = 18.05–29.10, p < 0.00001), Menorrhagia “(SMD = 25.67, CI = 3.86–47.47, p < 0.00001)”, PCOS “(SMD = 5.50, CI = 0.60–10.40, p < 0.00001)”, and Polymenorrhea “(SMD = 4.90, CI = 1.87–12.81, p < 0.0001)”. A statistically significant improvement in knowledge “(SMD = 2.06, 95% CI = 0.75–3.36, p < 0.00001)” and practice “(SMD = 1.26, 95% CI = 0.13–2.65, p < 0.00001)” on menstruation was observed. Infections of the reproductive system and their repercussions can be avoided with better awareness and safe menstruation practices.

Conclusions

Learning about menstrual hygiene and health is essential for adolescent girls' health education to continue working and maintaining hygienic habits. Infections of the reproductive system and their repercussions can be avoided with better awareness and safe menstruation practices.

Plain language summary

Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) and practices by adolescent females of low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are severe problems for girls, parents, society, and policymakers. Menstrual-related problems are widespread among adolescent girls in India. Different menstrual abnormalities are found in different populations, suggesting socio-cultural and regional variation. Menstrual abnormalities and disorders are frequently linked to physical, mental, social, psychological, and reproductive issues, affecting adolescents' daily lives and their families lives by various psychosocial problems such as anxiety. We have the intention to compile, summarise, and critically analyse peer-reviewed and published scientific evidence from 2011 to 2021 on menstrual hygiene management methods used, most typical menstrual morbidities and their associated factors among Indian adolescent girls, and to evaluate the evidence for existing interventions like educational programs and absorbent distribution. Program planners and policymakers could use the findings of this study to build relevant initiatives to incorporate safe MHM in the country so that interventions can be designed taking into account the current needs of adolescent girls to reduce menstrual morbidities and improve their quality of life. A statistically significant improvement in knowledge and practice on menstruation was observed. Learning about menstrual hygiene and health is an essential aspect of adolescent girls’ health education to continue working and maintaining hygienic habits. Infections of the reproductive system and their repercussions can be avoided with better awareness and safe menstruation practices.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The onset of menstruation (menarche) is one of the most significant transformations that girls go through during their adolescent years. Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) and practices by adolescent females of low and middle-income countries (LMICs) are a severe concern [ 1 , 2 ]. Studies show that more than 50% of girls follow unsatisfactory MHM in LMICs, with rural areas having a higher percentage than urban areas [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Efficacious MHM requires access to clean absorbents and facilities for changing, cleaning or disposing of them as required, and soap and water for cleansing the body and the absorbents used during menstruation [ 5 ]. Hygiene-related practices during menstruation can lead to an increase in the risk of developing reproductive tract infections. Poor menstrual hygiene has a direct or indirect impact on the Sustainable Development Goals (3, 4, 5 and 6) and achieving them is critical for the overall development of these young adolescents and the country [ 6 ]. Although menstruation is a normal part of life, and it is associated with several myths and misunderstandings that might negatively affect health [ 7 ]. Menstruation is still seen as something repulsive or dirty in Indian society [ 8 ]. MHM is a severe problem in India for school-aged teenagers due to a lack of safe, sanitary facilities and limited or no sanitary hygiene products. As a result, many girls drop out of school due to a shortage of menstrual hygiene products and services [ 6 ].

Menstrual-related problems are widespread among adolescent girls in India. Different types of menstrual abnormalities are found in different populations, suggesting socio-cultural and regional variation [ 9 ]. Sixty-four per cent of girls have at least one menstrual-related issue [ 10 ]. In the age group of 10–19 years, poor menstrual hygiene and lack of self-care are critical drivers of morbidity and other problems. Some of the issues are urinary tract infections (UTI), scabies in the vaginal area, atypical abdominal pain, absence from school, and pregnancy complications [ 11 ]. Studies report that out of an estimated 113 million adolescent girls in India, around 68 million adolescent girls attend roughly 1.4 million schools. Poor MHM practices and cultural taboos are viewed to be barriers to their school attendance [ 12 , 13 ]. Menstrual abnormalities and disorders are frequently linked to physical, mental, social, psychological, and reproductive issues, affecting adolescents’ daily lives and their families' live through various psychosocial problems such as anxiety [ 14 ].

To recognise the importance of promoting menstruation hygiene practices, the Government of India is undertaking many activities to raise awareness about the pivotal role that good MHM plays in enabling adolescent girls and women to achieve their full potential. A scheme was introduced in August 2011 to provide sanitary napkins at subsidised prices to adolescent girls in rural areas [ 15 ] as their reproductive health decisions today will impact the health and well-being of future generations and their community. On May 28, Menstrual Hygiene Day is observed to raise awareness of the problems that women and girls suffer as a result of their menstruation and to promote solutions that address these problems. Despite India’s efforts, a significant portion of adolescent girls lack prior knowledge of the menstrual cycle and associated hygienic habits, resulting in poor menstrual hygiene practices [ 16 ].

Numerous studies have been undertaken across India to assess the prevalence of MHM and its associated variables among adolescent schoolgirls. The results of these investigations were inconsistent and subject to significant variations. Also, various systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been conducted on MHM, incorporating either cross-sectional, case–control or interventional studies. To the best of our knowledge, we could not find any systematic review that has included all types of studies on MHM in the Indian context. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled proportion of the hygiene practices, menstrual problems with their associated factors, and the effectiveness of educational interventions on menstrual hygiene among adolescent schoolgirls in India. The intention is to compile, summarise, and critically analyse peer-reviewed and published evidence from 2011 to 2021 on MHM methods used, most typical menstrual morbidities and their associated factors among Indian adolescent girls, and evaluate the evidence for existing interventions like educational programs and absorbent distribution. Program planners and policymakers could use the findings of this study to build relevant initiatives to incorporate safe MHM in the country so that interventions can be designed taking into account the current needs of adolescent girls to reduce menstrual morbidities and improve their quality of life.

The design and methodology for this systematic review and meta-analysis are developed and reported as per the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)” checklist [ 17 ]. The PICO guidelines [ 18 ] were used to determine eligibility requirements.

Data sources and search strategy

One junior researcher (PS) and one senior researcher (PA) independently searched scientific literature in July 2021 to identify peer-reviewed published studies from 2011 to 2021 on menstrual hygiene, menstrual abnormalities and their associated factors and the effectiveness of education programmes among adolescent girls in India. Various combinations of keywords, “menstruation, hygiene, abnormalities, disease, morbidity, prevalence, associated factors, education, intervention and association” were administered. These search terms were combined with Boolean operators OR and AND to broaden or narrow the search. Additional studies were included by searching randomly in the databases. We limited the search results to Indian studies and further checked the original and review articles' reference lists that the initial search yielded to identify additional full-text articles. The search strategy used for different databases is presented in Table 1 .

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria Peer-reviewed journal articles written in English comprising original observational and interventional studies that reported menstrual morbidities such as dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), menorrhagia, polymenorrhagia, and oligomenorrhoea, along with articles incorporating the importance of education on menstruation from 2011 to 2021among Indian adolescent schoolgirls were included.

Exclusion criteria Systematic and narrative reviews, studies not performed on the Indian population, project reports, economic analysis, unpublished research and policy analysis have been excluded from this systematic review.

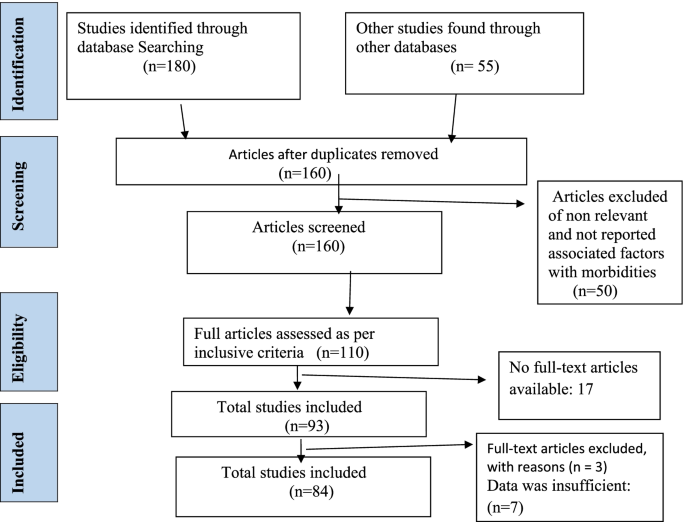

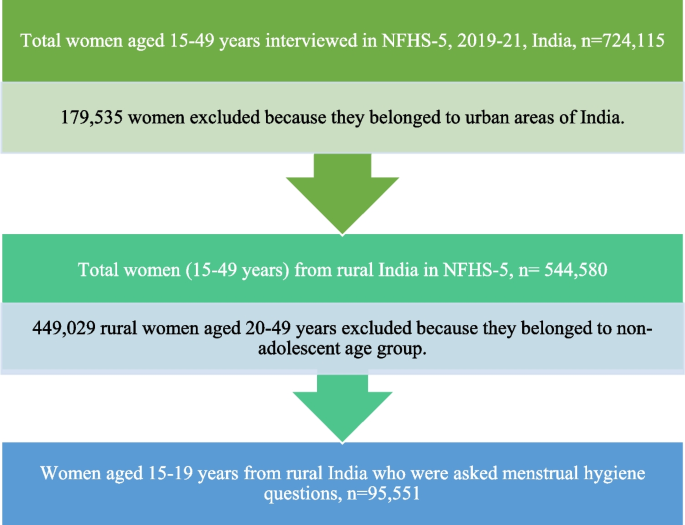

Study selection All the retrieved articles from each database found throughout the search process were noted, duplicates were deleted, and titles, abstracts, and complete publications were evaluated against eligibility criteria. The researchers screened the titles of the studies and their abstracts according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two senior researchers rechecked data through repetitive meetings and all the disagreements and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. PRISMA flow diagram for data identification, screening, inclusion and exclusion is presented in Fig. 1 .

PRISMA flow chart

Data extraction

Data were extracted by designing the data extraction form, which includes the constituents like information about the publication, i.e., author(s) and year, location of study, the state of India where the study was performed, sample size, study procedure, menstrual hygiene practices, types of menstrual irregularities, common menstrual disorders and role of education on menstruation.

Data synthesis

Revman 5.4 was used for statistical analysis (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The meta-analysis included only papers that generated sufficient data on any pre-determined outcome measures. Because it is a more traditional methodology that compensates for the fact that study heterogeneity can differ more than by chance, a random-effects model was adopted to generate pooled effect sizes since we expected much heterogeneity. This approach assumes that the studies included are selected from ‘populations’ of research systematically different from one another (heterogeneity). The prevalence estimated from the included research varied due to random error among studies (fixed effects model) and genuine variance in prevalence from one study to the next. The data at the end of the intervention were retrieved for both the intervention and control groups. MS Excel was used for data synthesis.

Quality assessment

The authors used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale to assess the quality of studies included in the review [ 19 ]. The standard of observational and interventional studies was assessed using this scale. This scale uses a “star” system (with a maximum of nine stars for cross-sectional studies and seven stars for intervention-based studies) to rate the quality of a study in three areas: participant selection, study group comparability, and interest outcome determination.

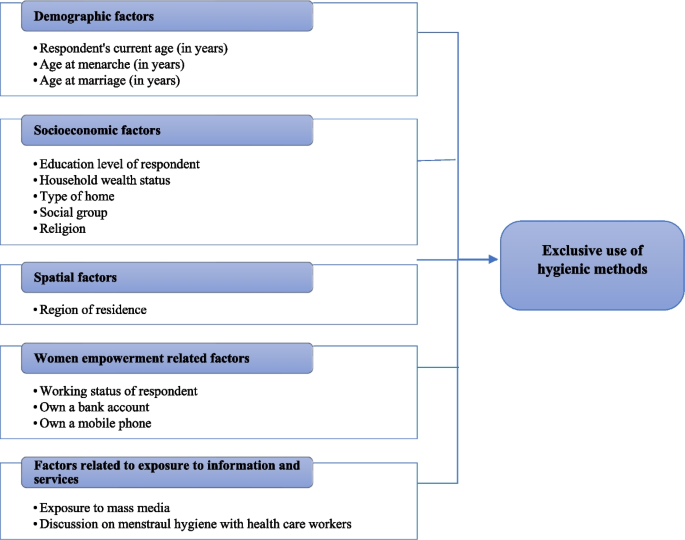

Characteristics and quality assessment of studies

The studies conducted from 2011 to 2021 intending to evaluate the menstrual hygiene practices, were screened and the most typical menstrual morbidities and their associated factors among young girls were identified. A total of 84 relevant studies reporting hygiene practices during menstruation by adolescent girls and menstrual morbidities and associated factors in India were obtained after removal of duplication and studies that did not fulfil inclusion criteria. Data collected from 84 studies were scrutinised and codes were created based on our objective and heterogeneity. Codes were again analysed and patterns among them were identified. Also, we thoroughly reviewed the literature on menstrual hygiene and associated factors to identify existing and emerging themes. Finally, we developed the following four themes for the final data analysis:

Type of absorbent used during menstruation

Hygiene practices during menstruation, mhm associated morbidities.

Interventions performed to improve knowledge and practices regarding menstruation

A complete description of all the studies, including demographic details, setting, interventions, methodology and outcomes based on four themes, are presented in Additional file 1 : Tables S1–S3. Quality assessment of included studies using Newcastle–Ottawa Assessment Scale shows that studies mainly were of low to moderate quality (Additional file 1 : Table S4).

Fifty-three studies with adequate information were included in the meta-analysis to study the use of sanitary pads by Indian adolescent girls during menstruation. Pooled data revealed a statistically significant increase in sanitary pad usage as an absorbent “(SMD = 48.83, 95% CI = 41.38–57.62, p < 0.00001)” (Fig. 2 ).

Pooled usage of sanitary pad as absorbent by Indian adolescent girls

Pooled data from fifteen studies reported a statistically significant “(SMD = 55.77, 95% CI = 44.27–70.26, p < 0.00001)” increase in perineum practices by adolescent girls during menstruation (Fig. 3 ). The random-effect model was used as the heterogeneity was statistically significant (p < 0.00001) and the inconsistency was too high (100%).

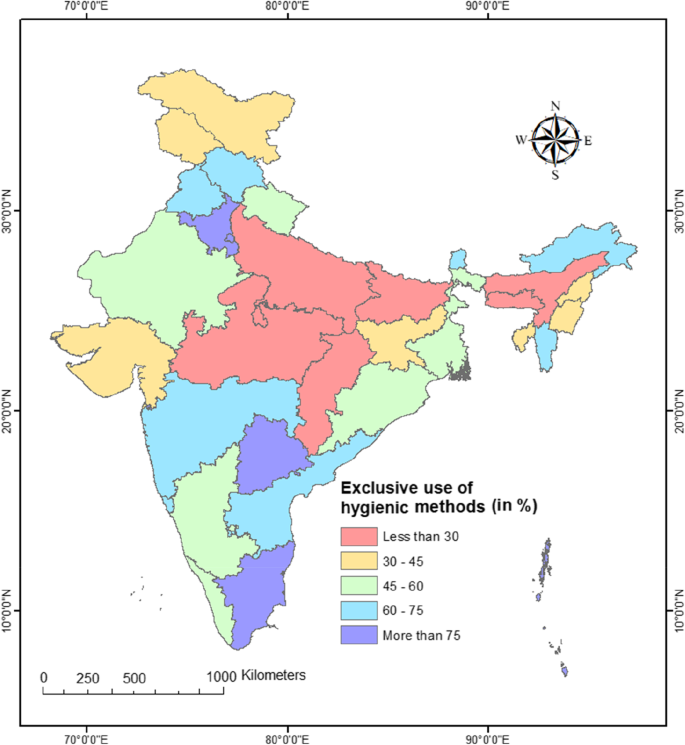

Pooled hygiene practices by Indian adolescent girls

Pooled data reported that most prevalent morbidities among Indian adolescent girls are dysmenorrhea “(SMD = 60.24, 95%, CI = 50.41—70.06, p < 0.0001)”, Pre-menstrual symptoms “(SMD 62.67, 95% CI = 46.83–78.50, p < 0.00001)”, Oligomenorrhea “(SMD 23.57, CI = 18.05–29.10, p < 0.00001)”, Menorrhagia “(SMD = 25.67, CI = 3.86–47.47, p < 0.00001)”, Hypomenorrhea “(SMD = 9.00, CI = 4.72–22.72, p < 0.00001)”, PCOS “(SMD = 5.50, CI = 0.60–10.40, p < 0.00001)”, and Polymenorrhea “(SMD = 4.90, CI = 1.87–12.81, p < 0.0001)”. Subgroup analysis was conducted to examine probable sources of between-study heterogeneity. The heterogeneity was statistically significant (p < 0.00001) and the inconsistency was high (100%). Figure 4 depicts a subgroup analysis of pooled data on prevalent morbidities among Indian girls. Various menstrual morbidity-associated factors, including modifiable factors, have been reported in the studies. Common modifiable associated factors include poor nutritional status, lower physical activities by girls, poor menstrual hygiene, education, and mother’s occupation. Other reported associated factors are family history, socioeconomic status, late menses, amount and duration of blood flow.

Subgroup analysis for Menstrual morbidities

Fifteen studies have found an association between nutritional status, BMI, Junk food, meals skip during menses, dieting by girls, dietary habits, and Nutritional deficiency with menstrual morbidities. However, one study found no association of BMI with menstrual morbidities among Indian young girls. Five studies found that girls had a family history of menstrual morbidities are more prone to develop dysmenorrhea. Out of 21 studies, five reported that a family’s socioeconomic status could be responsible for menstrual abnormalities among adolescent girls . Four studies reported lower physical activity among girls with more menstrual disorders. Three studies presented the association of practices during menstruation with menstrual morbidities. Two studies reported that girls with late-onset of late menstruation and low education level have higher chances of developing menstrual problems. One study found the association with the mother’s occupation; another study has reported the association of menstrual morbidities with bleeding duration and the girl’s age. It is also found that the mother’s education has been directly associated with the menstrual problems her daughter faces.

Interventions are performed to improve knowledge and practices regarding menstruation

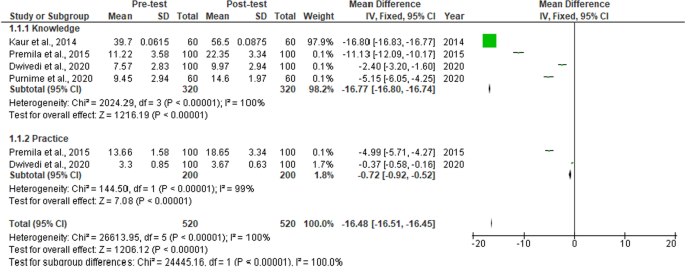

A total of fourteen interventional studies were retrieved, out of which seven were excluded due to insufficient data. Subgroup analysis was conducted to examine possible sources of between-study heterogeneity. Pooled data from three two group intervention studies revealed a statistically significant improvement in knowledge “(SMD = 2.06, 95% CI = 0.75–3.36, p < 0.00001)” and practice “(SMD = 1.26, 95% CI = 0.13–2.65, p = 0.00001)” on menstruation (Fig. 5 ). Pooled data from four one group pre-post interventional studies also revealed an overall improvement in knowledge “(SMD = − 16.77, 95% CI = 16.80 − 16.74, p < 0.00001)” and practice “(SMD = -0.72, 95% CI − 0.92 to − 0.52, p < 0.00001)” on menstruation among Indian adolescent girls. The heterogeneity was statistically significant (p < 0.00001) and the inconsistency was high Fig. 6 .

Subgroup analysis for overall changes in standardized mean difference indices for the knowledge and practice on menstruation in intervention based studies

Subgroup analysis for pooled changes in standardized mean difference indices for knowledge and practice on menstruation in one group Pre-post interventional based studies

The present study aimed to find studies that looked into menstrual hygiene, morbidities prevalence, and its factors, focusing on modifiable factors. Our search was susceptible to various potential biases, and it is critical to understand the type and prevalence of menstrual morbidities and their associated factors based on the result we have reported. We hoped that limiting our search and utilising broad search keywords would reduce the risk of bias in our literature selection. Hand scanning recognised articles for relevant references was added as an extra step. Given our time and resource limits, we believe we have broadened our search as far as possible. Numerous studies have been published on menstruation knowledge, awareness, and practice in low-income settings. Although each study focuses on a different context with different variables, one thing is clear: Menstrual disorders are a common problem in adolescents; at least one the menstrual morbidity is prevalent among Indian young girls, which is the source of anxiety for the patients and the families that are associated with various modifiable and non-modifiable factors [ 20 ].

Practices by adolescent girls during menstruation

Cloths have historically been used to absorb menstrual flow; they are less expensive and less polluting, but pads are progressively replacing them, especially in urban areas. If females do not have access to water, privacy, or a drying area, cleaning and drying clothes might be challenging [ 21 ]. Commercial pads were preferred by the authors of the reviewed studies and the participants, but cost prohibits widespread usage, particularly in rural regions. Compared to a national community-based study done in 2007–2009, our pooled estimate of pad use was greater than that in a separate report from 2010, in which 12% of 1033 females sampled across India used pads [ 22 ]. Our pooled data found that more adolescents clean their perineum during menses. This is in line with findings of other studies that reported a large percentage of females to use sanitary pads, bathe every day, and cleanse their genitalia with soap and water [ 23 , 24 ]. However, Only 4.6% of students in Andhra Pradesh, 11% of Haryana found washing their genitalia with soap and water during menses which could be a lack of awareness and facilities in the school.

Menstrual disorders

In this review study, we have reported the various menstrual disorders in which dysmenorrhea has been recorded as high, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), oligomenorrhea, Mennorhagia, Polymenorrhea, Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and Hirustusmus. Many studies have also reported the same various menstrual irregularities among young girls [ 21 , 25 ]. Dysmenorrhea, a medical ailment defined by intense uterine pain during menstruation presenting as the recurrent lower abdomen or pelvic discomfort that may also radiate to the back and thighs, has been recognised as the most frequent disorder [ 21 ]. There are two types of dysmenorrhea: primary dysmenorrhea and secondary dysmenorrhea. Primary dysmenorrhea occurs when there is no co-existing pathology, and secondary dysmenorrhea occurs when there is an identified and modifiable cause [ 26 ]. After dysmenorrhea, other menstrual abnormalities noted were polymenorrhea which is the condition where the gap between two consecutive cycles is 21 days, but in oligomenorrhea, it can be up to 35 days. [ 27 ] The premenstrual syndrome, also reported in various studies, is a collection of cyclic, repeating physical, emotional, and behavioural symptoms that appear during the late luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and disappear when menses begin. Symptoms range is comprehensive and affects all aspects of life (family, social, occupational). The condition for PMS diagnosis is the existence of two consecutive periods accompanied by annoying changes [ 27 , 28 ]. Various factors were associated with menstrual morbidities. The main reason for morbidity prevalence could be not using the sanitary pads due to cost considerations. Other reasons included were absorbent disposal issues, lack of awareness about hygiene, and personal choice among girls.

Common modifiable factors

Poor nutritional status, a high BMI, junk food consumption, meal skipping during menses, female dieting, decreased physical activity, low socioeconomic status and anaemia have all been identified as contributing causes to menstrual problems. Junk foods are low in micronutrients such as vitamin B6, calcium, magnesium, and potassium, which may be responsible for initiating premenstrual symptoms [ 14 ]. Another study found a link between frequent junk food consumption and irregular menstrual periods, abnormal flow, dysmenorrhea, and PMS [ 29 ]. According to Fujiwara et al., the frequency of fast food consumption was linked to dysmenorrheal [ 30 ]. To improve the menstrual health of young college girls, a study has suggested emphasising the reduction of junk food consumption and promoting healthy eating practices [ 31 ]. Also, it is essential to avoid skip of meals and diet to maintain good menstrual health. In earlier research, the lower socioeconomic level was linked to higher illness severity, morbidity, mortality, and barriers to accessing more advanced medical treatments [ 29 , 32 ]. However, in the one study, the prevalence of menstruation disorders was higher in females with a middle socioeconomic class due to a sedentary lifestyle and junk food intake than in females with a low socioeconomic position owing to a sedentary lifestyle and junk food consumption [ 29 ]. Higher socioeconomic status (SES) could also be because of menstrual problems as high SES is more at high risk of consumption of fast food and a sedentary lifestyle [ 20 ].

According to the study, menorrhagia has a strong negative link with salad consumption and socioeconomic status, whereas oligomenorrhea has a favourable link with socioeconomic status. The contradictory relationship with socioeconomic level could be attributed to high socioeconomic level individuals' increased consumption of junk food, sedentary lifestyles, and lack of knowledge about healthy eating habits [ 29 ]. Good nutrition and a healthy lifestyle induce puberty earlier. As menstruation is the last process of puberty, it delays adolescence with stress, poor nutrition, and an unhealthy lifestyle [ 33 , 34 ]. Physical activity and menstrual irregularities have been found to have a strong link. Compared to students who did not exercise regularly for more than 3 days a week, regular students had fewer menstrual irregularities in cycle length, flow, dysmenorrhea, and PMS. Regular physical activity helps maintain optimal body weight, enhance insulin sensitivity, enhance BMR, and release endorphins, which aid in menstrual cycle regularisation, PCOS and hypothyroidism improvement, PMS reduction, and overall well-being [ 14 , 35 ].

Adolescent gynecologic problems are unique in the spectrum of gynecologic illnesses of all ages, as 75% of women suffer from menstrual issues. A statistically significant link between a girl’s educational level and reproductive morbidity has been reported. As one's level of education rises, so does one’s age in years, and as one’s age rises, so does reproductive morbidity [ 36 ]. Girls with a lower educational level may be unwilling to discuss reproductive morbidity. This could explain the current study’s findings. It is suggested that an aware girl and a mother continue with girl education could improve the family’s well-being and quality of life. Poor menstrual hygiene practices are closely linked to reproductive tract morbidities, damaging a woman’s life. According to research, a large information gap exists among adolescent girls in terms of prior awareness of menstruation and menstrual cleanliness, which impacts menstrual practices and associated gynaecological morbidities [ 37 ]. Different cultures in India have different types of limitations during menstruation, which could be a factor in the lack of compliance with proper menstrual hygiene [ 38 , 39 ]. PCOS was linked to a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism in the family. According to previous research, the likelihood of discovering a metabolic problem in the families of PCOS patients is 2.7 times higher than in the control group [ 40 ]. As a result, PCOS is more common in girls whose parents and grandparents had metabolic abnormalities than in girls whose parents and grandparents did not. Hypertension is three times more common in women with PCOS than in those without the condition, according to previous research [ 20 ].

With intervention, the post-test and experimental groups significantly improved menstrual hygiene compared to the pre-test and control groups. This study is backed by various studies that found a need for health education and behaviour change programmes in this area [ 41 , 42 , 43 ]. This type of intervention in schools can eradicate preconceptions, prejudices, and improper familial behaviours. So imparting the proper knowledge, changing attitudes and practices, and reducing the likelihood of developing morbidities like RTI [ 44 ]. A study conducted in Egypt also found that a menstrual education programme for first and second-year girls at a secondary school was adequate and that the programme needed to be expanded to elementary, preparatory, and other secondary schools [ 45 ]. A similar study by Chang et al. on primary school girls in grades 5 and 6 found that educational programmes in schools for students and their parents were effective [ 43 ]. Another study conducted in Bangladesh found a 31.4 per cent improvement in follow-up knowledge scores, identical to the current study but with only one intervention group [ 46 ].

By examining replies and gauging retention after the intervention, our study offers evidence to support the efficacy of education training in producing a lasting influence on knowledge levels. Furthermore, few studies have looked at changes in views immediately after intervention and several months later. The importance of family life education in the school health programme has been recognised. We can increase knowledge by including themes on specific physiological aspects of menstruation and pregnancy in health education programmes offered by health professionals for adolescent girls [ 47 ].

We recommend that public health programmes strengthen menstrual hygiene management and associated factors. Evidence-based research, particularly research targeting the most underserved to assess the actual impact and outcomes of programmes targeting MHM should be conducted in the country. Support for learning from the implementation of government programmes and policies to share across country governments, longitudinal research to measure relevant impact and outcomes; increased investment in the evidence base for addressing MHM in schools, particularly research targeting the most underserved; and a better understanding of costs and effectiveness, as well as the benefits of comprehensive, cross-sectoral addressing MHM in schools are among the key recommendations for actions that will advance the agenda. All of these efforts will help the young girls to become aware of and comfortable with their menstrual cycle and will be able to manage their periods in a pleasant, safe, and dignified manner.

Implications

The results of this study can be helpful in future studies to prevent and treat menstrual disorders such as dysmenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, and premenstrual syndrome to promote menstrual health by modifying lifestyle and improving the quality of life of young Indian girls. Furthermore, this study suggests the need for research on associated factors of specific menstrual problems and the role of comprehensive intervention on menstruation among adolescent girls.

Menstruation-related problems are widespread among adolescent girls in India. Studies show that menarche results in feelings of stress, anxiety, depression, and anger. Our findings estimate that most Indian adolescent girls began menarche unaware of the reason, with very few knowing the source of bleeding. Learning about menstrual hygiene and health is an essential aspect of adolescent girls’ health education to continue working and maintaining hygienic habits. Infections of the reproductive system and their repercussions can be avoided with better awareness and safe menstruation practices. The ideal menstrual health education programme would teach students to consider the connections between knowledge, behaviour, and improved human health. It would also assist in the improvement of maternal health. There is a need to address the menstrual morbidities in young girls’ initial stages of life. Therefore workshops, adding a chapter to some course’s literature focusing on improving the lifestyle and associated modifiable factors with raising girls’ general information about the following: physiology of menstruation, the relationship between hormonal changes, symptoms and menstrual disorders and their associated factors.

Strengths and limitations

There is the possibility of selective reporting bias or publication prejudice in any review. Our review found many outcomes, ranging from substantially positive associations to the inverse. We attempted to broaden our review to include these studies, given the time and resources available. However, this was not possible due to time and resource constraints. With these constraints in mind, we have concluded that most studies on menstrual hygiene practices, morbidities, and their associated factors focus on determining the prevalence of exposure. We conducted a systematic search for articles and included research based on explicitly specified criteria to reduce selection bias, which strengthened this review.

Furthermore, between-study high heterogeneity is observed in the present review as depicted by I 2 statistic. This may be due to different methodologies and study settings. We developed four themes to analyse and interpret our results and conducted subgroup analysis by type of morbidity and study design.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article and additional sheets. No additional data is available.

Abbreviations

Body mass index

Basic metabolic rate

Low and middle-income countries

- Menstrual hygiene management

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Population intervention comparison of outcome

Premenstrual syndrome

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Socioeconomic status

Standardized mean difference

Urinary tract infections

Chandra-Mouli V, Patel SV. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low-and middle-income countries. The Palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies 2020:609–36.

Hennegan J, Montgomery P. Do menstrual hygiene management interventions improve education and psychosocial outcomes for women and girls in low and middle income countries? A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2): e0146985.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

El-Gilany A-H, Badawi K, El-Fedawy S. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent schoolgirls in Mansoura, Egypt. Reprod Health Matters. 2005;13(26):147–52.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Khanna A, Goyal R, Bhawsar R. Menstrual practices and reproductive problems: a study of adolescent girls in Rajasthan. J Health Manag. 2005;7(1):91–107.

Article Google Scholar

Sommer M, Sahin M. Overcoming the taboo: advancing the global agenda for menstrual hygiene management for schoolgirls. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1556–9.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sharma S, Mehra D, Kohli C, et al. Menstrual hygiene practices among adolescent girls in a resettlement colony of Delhi: a cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6(5):1945–51.

Shanbhag D, Shilpa R, D’Souza N, et al. Perceptions regarding menstruation and practices during menstrual cycles among high school going adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. Int J Collaborative Res Internal Med Public Health. 2012;4(7):1353.

Google Scholar

Cherrier H, Goswami P, Ray S. Social entrepreneurship: creating value in the context of institutional complexity. J Bus Res. 2018;86:245–58.

Rupa Vani K, Veena K, Subitha L, et al. Menstrual abnormalities in school going girls-are they related to dietary and exercise pattern? J Clin Diagn Res JCDR. 2013;7(11):2537.

Sharanya T. Reproductive health status and life skills of adolescent girls dwelling in slums in Chennai, India. Natl Med J India. 2014;27(6):305–10.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ramachandra K, Gilyaru S, Eregowda A, et al. A study on knowledge and practices regarding menstrual hygiene among urban adolescent girls. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2016;3(1):142–5.

Thakur H, Aronsson A, Bansode S, et al. Knowledge, practices, and restrictions related to menstruation among young women from low socioeconomic community in Mumbai, India. Front Public Health. 2014;2:72.

Muralidharan A, Patil H, Patnaik S. Unpacking the policy landscape for menstrual hygiene management: implications for school Wash programmes in India. Waterlines. 2015;34:79–91.

Dars S, Sayed K, Yousufzai Z. Relationship of menstrual irregularities to BMI and nutritional status in adolescent girls. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30(1):141.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jogdand K, Yerpude P. A community based study on menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls. Indian J Maternal Child Health. 2011;13(3):1–6.

Hema Priya S, Nandi P, Seetharaman N, et al. A study of menstrual hygiene and related personal hygiene practices among adolescent girls in rural Puducherry. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017;4(7):2348–55.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2016;350(354): i4086.

Riva JJ, Malik KM, Burnie SJ, et al. What is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2012;56(3):167.

Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. p. 1–12.

Desai N, Tiwari R, Patel S. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome and its associated risk factors among adolescent and young girls in Ahmedabad region. Indian J Pharm Pract. 2018;11(3):119.

Narayan K, Srinivasa D, Pelto P, et al. Puberty rituals, reproductive knowledge and health of adolescent schoolgirls in South India. Asia-Pac Popul J. 2001;16(2):225–38.

Anand E, Singh J, Unisa S. Menstrual hygiene practices and its association with reproductive tract infections and abnormal vaginal discharge among women in India. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(4):249–54.

Speizer IS, Magnani RJ, Colvin CE. The effectiveness of adolescent reproductive health interventions in developing countries: a review of the evidence. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(5):324–48.

Singh Z, Datta S. Perception and practices regarding menstruation among adolescent school girls in Pondicherry. Health. 2014;2(4).

Sherly Deborah G, Siva Priya D, Rama SC. Prevalence of menstrual irregularities in correlation with body fat among students of selected colleges in a district of Tamil Nadu, India. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol. 2017;7(7):740–3.

Qorbanalipour K, Ghaderi F, Jafarabadi MA, et al. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of modified Moos Menstrual Distress Questionnaire. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertility. 2016;19(29):11–8.

Lakkawar NJ, Jayavani R, Arthi P, et al. A study of menstrual disorders in medical students and its correlation with biological variables. Sch J App Med Sci. 2014;2(6E):3165–75.

Silva CMLd, Gigante DP, Carret MLV, et al. Population study of premenstrual syndrome. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40:47–56.

Randhawa JK, Mahajan K, Kaur M, et al. Effect of dietary habits and socioeconomic status on menstrual disorders among young females. Am J Biosci. 2016;4:19–22.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Fujiwara T, Sato N, Awaji H, et al. Skipping breakfast adversely affects menstrual disorders in young college students. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2009;60(sup6):23–31.

Lakshmi SA. Impact of life style and dietary habits on menstrual cycle of college students. Int J Sci Res. 2015;4(4):2845–7.

Landy CK, Sword W, Ciliska D. Urban women’s socioeconomic status, health service needs and utilisation in the four weeks after postpartum hospital discharge: findings of a Canadian cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):1–9.

Sindhuja K. A study to assess the effectiveness of aerobic exercise on primary dysmenorrhoea among Adolescent Girls at Selected College, Coimbatore. PSG College of Nursing, Coimbatore, 2017.

Avasarala AK, Panchangam S. Dysmenorrhoea in different settings: are the rural and urban adolescent girls perceiving and managing the dysmenorrhoea problem differently? Indian J Community Med. 2008;33(4):246.

Teixeira ALdS, Oliveira ÉCM, Dias MRC. Relationship between the level of physical activity and premenstrual syndrome incidence. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetricia. 2013;35(5):210–4.

Nath A, Garg S. Adolescent friendly health services in India: a need of the hour. Indian J Med Sci. 2008;62(11):465.

Mathiyalagen P, Peramasamy B, Vasudevan K, et al. A descriptive cross-sectional study on menstrual hygiene and perceived reproductive morbidity among adolescent girls in a union territory, India. J Fam Med Primary Care. 2017;6(2):360.

Verma P, Ahmad S, Srivastava R. Knowledge and practices about menstrual hygiene among higher secondary school girls. Indian J Community Health. 2013;25(3):265–71.

Patle R, Kubde S. Comparative study on menstrual hygiene in rural and urban adolescent girls. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2014;3:129.

Sinha U, Sinharay K, Saha S, et al. Thyroid disorders in polycystic ovarian syndrome subjects: a tertiary hospital based cross-sectional study from Eastern India. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(2):304.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Deshpande TN, Patil SS, Gharai SB, et al. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls–a study from urban slum area. J Fam Med Primary Care. 2018;7(6):1439.

Pal J, Ahmad S, Siva A. Impact of health education regarding menstrual hygiene on genitourinary tract morbidities: an intervention study among adolescent girl students in an urban slum. Int J Res Med Sci. 2017;5(11):4937–41.

Chang Y-T, Chen Y-C. Menstrual health care behavior and associated factors among female elementary students in the Hualien region. J Nurs Res. 2008;16(1):8–16.

Dasgupta A, Sarkar M. Menstrual hygiene: how hygienic is the adolescent girl? Indian J Community Med. 2008;33(2):77.

Fetohy EM. Impact of a health education program for secondary school Saudi girls about menstruation at Riyadh city. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2007;82(1–2):105–26.

PubMed Google Scholar

Haque SE, Rahman M, Itsuko K, et al. The effect of a school-based educational intervention on menstrual health: an intervention study among adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7): e004607.

Jyothi B, Hurakadli K. Knowledge, practice and attitude of menstrual hygiene among school going adolescent girls: an interventional study in an urban school of Bagalkot city. Med Innov. 2019;8:16–20.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Open access funding provided by Mid Sweden University. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Allied Health Sciences, Delhi Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research University, New Delhi, 110017, India

Jaseela Majeed

Master of Public Health, Delhi Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research University, New Delhi, 110017, India

Prerna Sharma

Department of Public Health, School of Allied Health Sciences, Delhi Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research University, New Delhi, 110017, India

Puneeta Ajmera

Division of Public Health Science, Institute for Health Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden

Koustuv Dalal

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PA conceptualised and designed the study and discussed it with KD. PS and PA carried out the literature review and drafted the initial manuscript. KD and JM made critical revisions to work and analysed data to get results. KD critically reviewed and edited the whole manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Koustuv Dalal .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This is a review study and does not need any ethical permission.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. table 1..

Morbidities and Associated factors. Table 2. Use of absorbent and perineum cleaning during menses. Table 3. Intervention based studies on menstruation. Table 4. Quality assessment of included studies by using Newcastle – Ottawa Assessment Scale

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Majeed, J., Sharma, P., Ajmera, P. et al. Menstrual hygiene practices and associated factors among Indian adolescent girls: a meta-analysis. Reprod Health 19 , 148 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01453-3

Download citation

Received : 04 November 2021

Accepted : 05 June 2022

Published : 23 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01453-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Menstruation

- Abnormalities

- Intervention

- Association

Reproductive Health

ISSN: 1742-4755

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2022

Menstrual hygiene management practice among adolescent girls: an urban–rural comparative study in Rajshahi division, Bangladesh

- Md. Abu Tal Ha 1 &

- Md. Zakiul Alam 1

BMC Women's Health volume 22 , Article number: 86 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

14 Citations

Metrics details

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical period characterized by significant physical, emotional, cognitive, and social changes, including the monthly occurrence of menstruation of adolescent girls. Despite being an inevitable natural event, most societies consider menstruation and menstrual blood as taboos and impure. Such consideration prevents many adolescent girls from proper health education and information related to menstrual health, which forces them to develop their ways of managing the event. This study attempted to explore the pattern, the urban–rural differences, and the determinants of menstrual hygiene management practices (MHMP) among adolescent girls in the Rajshahi division, Bangladesh.

Methodology

Using a cross-sectional study design with multistage random sampling, we collected data from 586 adolescent girls (aged 14–19 years) from the Rajshahi division of Bangladesh. The MHMP was measured using eight binary items, where the value from zero to five as ‘bad,’ six as ‘fair,’ and seven-eight as ‘good’ practices. Finally, we employed bivariate analysis and multinomial logistic regression analysis.

Only 37.7% continuously used sanitary pads. Among the cloth users, nearly three-fourths reused cloths, and about 57% used water and soap to wash them. About 49% changed menstrual absorbent, and 44% washed their genitalia three times daily. About 41% used water only to wash genitalia, and 55% buried sanitary materials under the soil. Around 36.9% of the girls practiced bad, 33.4% fair, and 29.7% good menstrual management. We found significant differences in MHMP among adolescent girls between urban and rural areas (32.3% vs. 27.7% good users, p ≤ 0.05 ). Multinomial logistic regression found that place of residence, age, family size, parental education, and age at first menstruation were the significant determinants of MHMP.

Although there are some cases of sanitary pad use, still menstrual hygiene management is unhealthy in most cases. The continuous supply of sanitary pads at affordable cost, change in existing social norms about menstruation, proper education, information, and services are essential for achieving health-related SDG goals in both rural and urban areas of Bangladesh.

Peer Review reports

Adolescence is a critical period in women’s lives characterized by first menstruation, a natural and beneficial biological event, and significant physical, emotional, cognitive, and social changes [ 1 , 2 ]. Despite being an inevitable and natural process, most societies consider menstruation a taboo [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Many of the norms and stigma associated with the event are based on discriminatory gender roles and cultural restrictions, making it a silent and invisible issue [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. As a result, it prevents many adolescent girls from receiving proper menstrual health and hygiene-related information and education. Furthermore, it also exposes them to challenges of managing menstruation and menstrual blood properly and forces them to develop their ways of managing it depending on existing traditional and cultural beliefs, level of knowledge on menstruation, and personal preferences [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ].

In a country like Bangladesh, mothers and other female relatives are the primary sources of information on menstruation; however, they can provide very little information, which is often misconceptions, thereby affecting adolescent girls’ response to menstrual management [ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Studies show that unhealthy practices of menstrual management among adolescent girls are highly prevalent in Bangladesh [ 1 , 7 , 11 , 12 ]. Globally, poor menstrual management affects girls’ school attendance and academic progress through psychological (for example, discomfort, high stress, fear of leakage of menstrual blood, and fear of leaving signs of menstrual blood inside the school latrine) and physical (for example, Dysmenorrhoea, Headache, and excessive bleeding) factors [ 2 , 12 , 13 ]. At the same time, it affects their maternal and reproductive health through increased risk of reproductive tract infections (RTI), sexually transmitted diseases (STD), Human Papillomavirus (HPV) infection, and adverse pregnancy outcomes [ 1 , 2 , 14 ]. Understanding the menstrual hygiene management practices (MHMP) of adolescent girls is therefore crucial for informing strategies to promote equitable education, gender equality, women’s empowerment, health, and environment in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [ 10 ].

Despite being a significant public health issue, there is limited understanding of the extent of proper MHMP in low and middle-income countries, including Bangladesh [ 11 ]. Studies on menstrual management practices conducted in Bangladesh have, for instance, focused on narrow topics such as the prevalence of the practices or the relationship between menstruation and girls’ school attendance, with no consideration of the broader dimensions of menstrual hygiene management and its socioeconomic determinants [ 1 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 12 ]. This paper examines the menstrual management practices of adolescent girls in the Rajshahi Division (randomly selected) of Bangladesh and the socioeconomic determinants of such practices.

Data and methods

Data collection process.

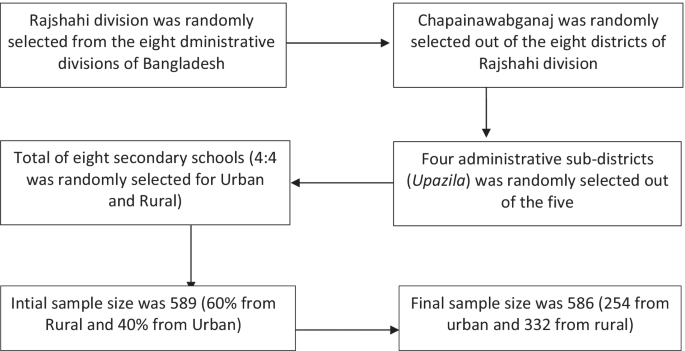

We used a multistage random sampling procedure to identify the research location. In the first stage, we randomly selected the study area, the Rajshahi division, among Bangladesh's eight administrative divisions. One of the administrative districts, Chapainawabganaj, was then randomly selected among the eight districts of the Rajshahi division. In the third stage, four administrative sub-districts ( Upazila in Bangladesh) were selected randomly out of the five sub-districts. In the final stage, eight secondary schools (four located in the urban area and the other four in the rural area) were randomly selected with the help of key informants to locate the schools., The target sample size was 589 adolescent girls in order to detect 10% prevalence of use of sanitary pad (based on the 2014 Bangladesh National Hygiene Baseline Survey) at a 95% confidence interval, 5% non-response rate, and 1.5 design effect for homogeneity among learners sampled from the same school. The current cross-sectional study was conducted on 17–25 November 2018 among adolescent girls aged 14 to 19 years studying in eight secondary schools in the Rajshahi Division of Bangladesh. In each school, an average of 37 adolescent girls (total sample divided by two classes of each school) in Standards 9 and 10 were randomly selected from the registrar. The initial target was to have 60% of the sample from rural areas and 40% from urban areas, as most (more than 60%) of the population lives in rural areas. However, the final sample size stands at 586 adolescent girls comprising 57% from rural areas and 43% from urban areas (Fig. 1 ).

Process of sample selection for the study

Adolescent girls studying in Standard 9 and 10 were targeted; they were considered mature enough to talk about a socially sensitive issue like menstruation and could provide their consent for participation in the research. Before the commencement of data collection, permission was obtained from the head of each school over the phone after informing the study's objectives. As permission was received, we collected detailed information of the potential respondents from those schools, randomly selected them, contacted their parents, and managed to receive their permission as the potential participants were minors. After getting permission from both heads of institutions and parents, one of the female teachers from each school was trained on the data collection process to oversee. On the interview day, randomly selected girls from Standard 9 and 10 were gathered in a classroom and were seated in-class environment. A questionnaire was given to students who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study after a short description of objectives and roles as respondents. After that, participants self-administered the questionnaire. The responsible female teacher collected the completed questionnaires.

Variable definitions and measurements

Outcome variable.

The dependent variable, “Menstrual Hygiene Management Practice (MHMP),” had three categories, namely ‘good,’ ‘fair,’ and ‘bad.’ A total of 8indicators, identified based on existing literature [ 7 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ], were used to measure menstrual hygiene management practices (Table 1 ).

For measurement purposes, healthy practices for each indicator were coded one, and unhealthy practices as zero. The first indicator was related to absorbent use for managing menstrual blood, where the use of sanitary pads and new cloth was regarded as healthy practices. However, the questions on washing cloth before re-using, materials used to a washcloth, place of drying and storing washed cloth (indicators 2.1 to 2.4 in Table 1 ) were only asked those who used the cloth to manage their menses [ 12 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. The positive response of all the four indicators about using old cloth was also considered healthy practices for indicator one. The other seven indicators included frequency of changing absorbent, washing of genitalia during menstruation, frequency of washing genitalia, the material used for washing genitalia, taking a bath during menstruation, frequency of bathing during menstruation, and ways of disposal of sanitary materials [ 7 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] and were applicable for all participants. Therefore, a score for the sum of eight indicators was used to measure MHM practices, with values ranging from zero to eight. The indicator was then categorized into bad (score of zero to five: up to 50%), fair (score of six: 50–75%), and good (score of seven and eight: 75–100%) MHM practices.

Socioeconomic and demographic variables were used as the independent variables, including age, family size, religion, wealth index, fathers’ and mothers’ education, fathers’ and mothers’ income, age of first menstruation, social connectivity, and information on menstruation before reaching menarche based on the existing literature [ 1 , 10 , 12 , 15 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. Age was categorized as ≤ 15 and ≥ 16 years old considering the year of schooling (class 9 and 10) and mean age (15.1) of the participants. Since mother and other female relatives were the primary sources of information on menstruation in Bangladesh [ 8 ], adolescent girls from small families may have a lower chance of receiving menstrual information; as the number of female relatives tends to be lower in these families. Thus, we decided to assess the relation between family size and menstrual hygiene management. Families with five or fewer members were defined as small, and more than five members as large families based on the average family size (4.4) in Bangladesh [ 30 ].

We used ten items on household possessions to generate an indicator of an individual’s family wealth status. Questions included flooring type of the respondent’s household, electricity connection, steel/wooden Almirah, smartphone, toilet, type of toilet, color television, refrigerator, air conditioner, and availability of transport used for a non-business purpose. All variables had binary responses (yes or no) except the type of toilet and transport. Positive responses were assigned value one, and negative answers were attributed zero. Type of toilet facility and transport were recoded into dummy variables. The availability of a motorcycle and/or cars/micro/bicycle was considered a positive response. Similarly, the availability of open and/or kancha (mud) toilets was considered a negative response, while sanitary toilets (with or without water slab) were considered a positive response. One was attributed for both variables for a positive response and zero for a negative response. The principal component analysis (KMO = 0.71) was used to measure the wealth index and categorized poor (bottom 40%), middle (next 40%), and rich (top 20%) following existing literature [ 24 ].

The perceived socioeconomic class was measured by two questions that asked participants about their perceptions of the specific class to which they belonged, with the response of very poor, poor, middle, upper, and uppermost. For analytical purposes, those who responded very poor and poor were assigned value one, the middle was attributed two, and the upper and uppermost were attributed three. The two variables were then summed to generate a variable with values ranging from two to six. Respondents attaining value 1–2 were defined as low, 3–4 as middle, and 5–6 were defined as a high socioeconomic class. As existing literature suggests, although there is a high unmet need for sanitary pads, many adolescent girls and women do not use them because of high costs [ 8 ]. At the same time, many women and adolescent girls still consider sanitary pads as a luxury item [ 31 ]. Thus, we incorporated this variable to assume that perceived socioeconomic class may affect sanitary pad use and other menstrual hygiene management practices. We also measured the fathers' income as low (up to BDT 10,000), middle (BDT 10,001 to 20,000), and high (BDT 20,001+); mothers’ income as yes and no.

We used three variables to measure respondents' social connectivity: physical mobility, passing the time with friends outside the school, and internet use. Respondents who could travel more than one kilometer alone from home during the daytime without parental consent were defined as physically mobile, and those who could travel less than one kilometer as non-mobile. We considered a minimum distance of one kilometer based on the assumption that sanitary pads may not be available within this one square kilometer area, thus limiting the chance of buying sanitary pads by respondents themselves. Physical mobility was attributed value one, and non-mobility was attributed zero. Similarly, passing the time with friends other than school period and using the internet regularly had two possible responses; yes and no; positive answers were assigned value one, and negative answers were assigned zero. The three variables were summed to generate a score with values ranging from zero to three. Those who scored zero were considered not socially connected, those with 1–2 as moderately connected, and those scoring three as highly connected.

Respondents’ perception towards pad use was measured using a set of four statements: (1) use of old clothes rather than pads to manage menses may increase the risk of reproductive tract infections , (2) use of sanitary pads to manage menses may prevent reproductive tract infections , (3) use of sanitary pads helps to regular menstruation , and (4) use of sanitary pads protects one from the fear of unwanted drop out of it . Each statement had five options; strongly agree, agree, do not know/not sure, disagree, and strongly disagree. Responses ‘agree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ were coded as positive responses, while the rest were negative responses.

Analytical approach

We used cross-tabulation with the Chi-square test to examine urban–rural differences in various menstrual hygiene practices. We then estimated a multinomial logistic regression model to examine the factors associated with hygiene management practices. The results from cross-tabulations are presented as percentages, while those from multinomial logistic regression analysis are presented as [coefficient estimates/relative risk ratios (RRR)] with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Table 2 represents the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents. Data show that the mean age of the respondents in this study was 15.5 (standard deviation is 0.71 years). Out of 586 girls, 254 (43.3%) lived in urban areas and the rest in rural areas. Most (71.8%) girls lived in small families with five members or fewer. Data regarding parents’ education indicated that 7.8% of fathers and 5.1% of mothers did not have formal education. The majority of the respondents (81.1%) were from middle-class families. About a third (32.8%) of the adolescent girls did not have social connections, while 31.7% reported having high social connectivities.

Menstrual knowledge of respondents

Results on menstrual knowledge are presented in Table 3 . The mean age at first menstruation was 12.8 (standard deviation of 0.97 years), slightly higher in rural than urban areas (12.9 and 12.6 years, respectively; p = 0.008). Three-quarters (75%) of the respondents reported that they received information about menstruation before reaching menarche, while the rest did not receive any information before their first menstruation. Sources of information about menstruation were mothers (42.1%), female friends (22.9%), female teachers (18.5%), sisters (13.2%), and others (3.2%). Results further show that half (50.2%) of the girls had positive perceptions about the use of sanitary pads. There were statistically significant variations in availability and sources of information and perception about the use of sanitary pads between adolescent girls in urban and rural settings. For instance, urban adolescents were more likely to receive information before menarche, specifically from female teachers, than their counterparts.

Menstrual hygiene management practices of adolescent girls

Table 4 presents the findings and shows that the highest 37.7% of adolescent girls used sanitary pads and 27.1% used old/new cloth only to manage their menstrual blood. The use of absorbent does not vary statistically ( p = 0.47) between urban and rural areas. Among the cloth users (n = 363, including occasionally cloth users), nearly three-fourths (71.1%) reused the same cloth, and almost all (97.7%) washed these cloths before reusing. Water and soap were used as the main ingredient (57%) in urban and rural areas. In 51.6% of cases, the washed cloth was dried in open sunny places, and after drying, nearly three-fourths (74.7%) of them were stored in hidden places in the room. Nearly half (48.5%) of girls changed menstrual materials three times a day, and only 0.4% changed it four or more times. These practices did not vary based on place of residence. Almost all (98.8%) washed their genitalia during menstruation. Data show that 44.2% of girls washed their genitalia three times, 33.7% four or more times, and 8.4% once a day. Around 41% of girls used only water to wash genitalia, which was higher in urban areas than rural areas. Both washing frequency and materials varied significantly between the two areas. Urban girls were more likely to wash their genitalia four or more times a day than rural girls, while rural girls were less likely to use water only to wash external genitalia than urban girls. More than three-fourths of the girls (77.5%) took a bath regularly during menstruation. After use, 55.3% of the girls buried their sanitary materials under the soil, and 20.2% threw them in the pond or river—the practice of disposing of sanitary materials varied between the two areas. Rural girls were more likely to throw their used sanitary materials into ponds or rivers; on the other hand, more urban girls buried them under the soil.

Barriers to continuous use of sanitary pad

Table 5 presents barriers to the continuous use of sanitary pads. Among the sanitary pad users, including mixed users (sometimes cloth and sometimes pad users), respondents (45.5%) and their parents (25.1% by mothers and 20.6% by fathers) were the primary buyers of sanitary pads. However, these sources varied based on place of residence. More girls in urban areas relied on their parents to buy sanitary materials, while more rural girls themselves bought them. More than one-third of girls felt shy to buy sanitary materials from male shopkeepers (36.1%), and this shyness increased in the presence of a male in the shop other than the shopkeeper (60.1%). More than three-fourths (76.1%) of adolescent girls could not use sanitary pads continuously due to their absence at home during their menstruation. In this circumstance, they either used old/new clothes (66.2%) or borrowed sanitary pads (28.4%) from others or took other measures to manage this. Among all-time cloth users, including old and new cloth, 71.8% wished to use sanitary pads but could not because of high cost (35.6%), feeling of embarrassment to buy sanitary pads (37.5%), unavailability of sanitary pads at nearby shops (10.6%) and other (16.3%) causes. Adolescent girls' unwilling to use sanitary pads mentioned relaxation to use cloths (60%), unnecessary money expending (27.5%), rashes (10%), and other (2.5%) causes as a reason.

Association between socioeconomic factors and menstrual hygiene management practices

The classification of menstrual hygiene management practices indicated that 36.9% of respondents followed bad, 33.4%, and 29.7% followed fair and good practices (Table 6 ). Variations in menstrual hygiene management practices show that urban adolescent girls had more good and fair practices ( p = 0.05) than rural girls. Similarly, girls from small families had more good practices than girls from large families ( p = 0.030). Parental education, parental income, and age at first menstruation were also statistically significant (Table 6 ). At the same time, religion, wealth index, perceived socioeconomic class, information before menstruation, perception toward pad use, and social connectivity were not significantly associated with menstrual hygiene management practices. Girls who experienced first menstruation at or after thirteen years of age were more likely to practice good and fair management than those who experienced first menstruation at earlier ages.

Only significant variables (p-value of 0.05 or less) from the bivariate analysis were entered into regression analysis (Table 7 ). The results show that the girls aged up to 15 years were less likely to have bad menstrual hygiene management practices (RRR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.32–0.80, P = 0.004) than if they did not have good management practices than the girls aged 16 and above years. Urban girls were less likely (RRR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.38–0.98, P = 0.045) to have bad menstrual hygiene management practices if they did not have good management practices compared to those from rural areas. Adolescent girls from small families were significantly less likely to have bad (RRR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.31–0.86) menstrual hygiene management practices if they did not have good management practices compared to those from large families. Girls whose fathers had no formal (RRR: 2.28; 95% CI: 1.16–9.28, P = 0.025), primary (RRR: 3.56; 95% CI: 1.84–6.88, P < 0.001) and secondary education (RRR: 3.11; 95% CI: 1.67–5.82, P < 0.001) were more likely to have bad menstrual hygiene management practices compared to those whose fathers had HSC or higher levels of education. Girls who experienced their first menstruation at 12 years or earlier were 66% more likely to practice bad menstrual hygiene management than those who experienced their first menstruation at 13 years or older (RRR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.05–2.63, P = 0.030).

Discussions

The main objectives of this study were to explore the menstrual hygiene management practices, the urban–rural differences in the practices, and the determinants of such practices. Our findings indicate that the mean age of respondents and the mean age of first menstruation in the study were 15.5 and 12.8 years, respectively. The mean age at first menstruation was slightly higher in rural (12.9) areas than urban areas (12.6). These findings are consistent with similar studies [ 7 , 10 , 19 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Proper education and information on menstruation before reaching menarche are the right to information of adolescent girls and are crucial for healthy menstrual management. A cross-sectional study conducted by Alam et al. (2017) shows that 64% of girls did not know about menstruation before reaching menarche [ 10 ]. The Bangladesh National Hygiene Baseline Survey 2014 also described that only 36% were informed about menstruation among the students before reaching menarche [ 7 ]. Compared to these studies, our study indicates that about 75% of the respondents received information about menstruation before reaching menarche, which indicates an increase in getting menstrual information before reaching menarche.

Before reaching menarche, getting information regarding menstruation was positively but not significantly associated with menstrual hygiene management practices. Like other studies, this study also found that mothers and sisters together were the two primary sources of menstruation-related information [ 7 , 10 , 19 , 35 , 36 ]. This finding is important because mothers with a lower level of knowledge can transfer very little regarding menstruation and often transfer misconceptions to their girl child [ 9 ]. On the other hand, high literacy and slight inhibition of mothers sharing their accurate knowledge to their daughters can positively affect adolescent girls’ conception and healthy management of menstruation over generations [ 19 ].

The absorbent used for managing menstrual blood is a primary health concern. The reuse of cloths without maintaining proper hygiene may increase the risk of reproductive tract infections [ 19 ]. The prevalence of using sanitary pads was 37.7%, significantly higher than previous studies conducted in Bangladesh [ 7 , 8 , 10 , 12 , 31 ]. According to our study, among the cloth users, including sometimes sanitary pads and sometimes cloth users, 71.1% reused cloths for absorbing menstrual blood, and 97.7% washed those materials before reusing; among them, 57% used water and soap, and 7.4% used water only. These findings were consistent with similar studies [ 1 , 7 , 10 , 15 , 19 , 25 , 37 ]. Re-using of clothes may even be better when proper sanitization is maintained as cotton cloths are reusable, readily available, and more environment-friendly than commercial sanitary pads [ 38 ]. However, drying sanitary materials in open and sunny places before re-using (51.6%) was significantly higher. Moreover, 74.7% of the respondent stored their dried clothes in hidden places within the room, and 13.8% with other cloths for reuse, and these findings differed from other studies [ 7 , 12 , 15 ].

Regular changing sanitary materials is a prerequisite for maintaining good menstrual hygiene management. Although there is no hard and fast rule of changing sanitary materials during menstruation, it depends mostly on blood flow, varying from person to person. However, it is suggested to change absorbent at least every four to eight hours during the menstrual cycle [ 7 ]. We considered changing sanitary materials at least three times a day to be good practice. This study results suggest that about 48.5% of the respondents changed their sanitary materials three times a day during menstruation, and this finding was also consistent with existing similar studies [ 7 , 10 ]. Rechanging sanitary materials and regular washing of external genitalia maintaining proper hygiene are crucial for healthy menstrual management. One study suggests that those who washed the body and external genitalia with water only were 2.4 times more likely to be asymptomatic of one or more urogenital diseases than those who used both water and soap for washing [ 39 ]. This study shows that 33.7% of respondents washed their genitalia four or more times, and another 44.2% washed it three times per day. In comparison, 38.7% of adolescent girls used water and soap for washing their external genitalia. These findings were identical to two similar studies conducted in India [ 19 , 40 ].

Disposal of sanitary materials properly is as important as other indicators of the menstrual hygiene management. Unhygienic disposal of sanitary materials in rivers, ponds, or even under the soil may increase the risk of infection of Hepatitis and HIV as sanitary materials soaked with the blood of an infected girl/woman may contain these Bacteria and viruses [ 38 ]. This study indicates that more than 55% of the participants disposed of their used sanitary materials under the soil. We found that 20.2% of adolescent girls threw their sanitary materials in ponds/rivers. This unhygienic behavior of disposing of used sanitary materials may put hundreds of people at risk of infection with fatal diseases like Hepatitis and HIV. Many people in Bangladesh use river and/or pond water for bathing and domestic washing purposes [ 41 ]. According to this study, the unmet need for disposable sanitary pads among non-pad users was 71.8%. Despite the high need, they (35.6%) could not use because of the high cost of sanitary pads and the embarrassment of buying pads from male shopkeepers (37.5%). Similar results were found in previous studies [ 1 , 8 , 37 ].

This study found that age, religion, family size, parental education, fathers’ income, perceived socioeconomic class, and age at first menstruation had a significant statistical association with menstrual hygiene management practices at the bivariate level, and these findings are similar to other studies [ 8 , 25 , 37 , 42 ]. Being Muslims, members of a large family and children of less-educated fathers were associated with bad menstrual hygiene management practices. In Bangladesh, Muslim adolescent girls are more conservative, which may result in lower access to modern sanitary materials. On the other hand, girls from well-off families and daughters of educated parents may have more accessibility, affordability to sanitary pads, and more chance of getting information on menstrual hygiene management [ 8 , 25 , 37 , 42 , 43 ]. This study observed significant urban–rural differences in terms of menstrual hygiene management practices. Like all other indicators of demography and health [ 43 , 44 ], the residents of urban areas have better menstrual hygiene management practices than rural areas. As a result, the percentage of respondents who did not participate in social activities, school, or work due to their last menstruation was significantly higher in rural areas than urban [ 43 ].

Limitations of the study