American Geosciences Institute

K-5 geosource, explore content.

- Investigations

- Literacy Strategies

- Science Fair Project

Education Resources

Profesional resources, education & outreach home, education geosource database, what are weather reports.

Weather reports vary a lot in how much information they contain. The simplest and shortest weather report contains only one piece of information: the present temperature. This is the type of report you often hear on the radio. More detailed weather reports also contain information about precipitation, wind speed and direction, relative humidity, atmospheric pressure, and other things as well.

A typical weather report tells you the high and low temperatures for the past day. It also tells you the present temperature. It might tell you the average temperature for the day, which lies halfway between the highest temperature and the lowest temperature. To find the average temperature, add the low temperature and the high temperature and then divide by two. The weather report might also tell you how many degrees the average temperature is above or below the normal temperature for that day. The normal temperature is found by adding up the average temperatures for that calendar day over a long period, like fifty years or a hundred years, and dividing by the number of years. In many areas of the United States, unusually hot or cold days can be as much as twenty degrees different from the normal temperature.

- Board of Directors

- AGI Connections Newsletter

- Nominations

- News and Announcements

- Membership Benefits

- Strategic Plan

- Annual Report

- Member Societies

- Member Society Council

- International Associates

- Trade Associates

- Academic Associates

- Regional Associates

- Liaison Organizations

- Community Documents

- Geoscience Calendar

- Center for Geoscience & Society

- Education & Outreach

- Diversity Activities

- Policy & Critical Issues

- Scholarly Information

- Geoscience Profession

- Earth Science Week

- Publication Store

- Glossary of Geology

- Earth Science Week Toolkit

- I'm a Geoscientist

- Free Geoscience Resources

- AGI Connections

- Be a Visiting Geoscientist

- Use Our Workspace

Definition of 'weather report'

Weather report in british english.

weather report in American English

Examples of 'weather report' in a sentence weather report, trends of weather report.

View usage for: All Years Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

Browse alphabetically weather report

- weather prevails

- weather protection

- weather radar

- weather report

- weather resistance

- weather satellite

- weather ship

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'W'

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

Weather Report

Explore what weather report means for your meetings. Learn more about its definitions, best practices, and real-world examples to enhance your meeting effectiveness. Dive into the importance, challenges, and solutions for each term.

In the fast-paced landscape of professional communication and meeting planning, weather reports hold significant importance. They provide essential information that can influence decision-making and logistical arrangements for various types of business meetings. By understanding the definition and significance of weather reports in this context, professionals can effectively navigate and mitigate potential challenges, ultimately leading to successful and productive meetings.

Get Lark for meeting minutes today.

Definition of weather report

Defining a Weather Report

A weather report is a comprehensive account of current and forecasted weather conditions, typically including temperature, precipitation, wind speed, and humidity. It presents meteorological data in an accessible format, enabling individuals to anticipate and plan for weather-related scenarios in specific locations and time frames.

Related Terms

- Meteorological Data

- Climate Forecast

Importance of weather report in meetings

Mitigating Disruptions

Weather reports serve as a proactive tool for anticipating and mitigating disruptions during meetings caused by unexpected weather conditions. Access to accurate and timely weather information enables organizers and participants to make informed decisions that can prevent scheduling conflicts and ensure the safety and comfort of attendees.

Enhancing Preparedness

The incorporation of weather reports in meeting planning enhances preparedness by providing crucial insights into potential weather-related challenges. It allows organizers to adjust timelines, select suitable venues, and make necessary accommodations to ensure that meetings progress smoothly, regardless of external weather conditions.

Safety Considerations

Weather reports are instrumental in addressing safety considerations during meetings. They enable organizers to account for factors such as extreme temperatures, storms, or other adverse weather events, ensuring the well-being of meeting attendees.

Learn more about Lark Minutes

Provide examples of how weather report applies in real-world meeting scenarios

Meeting scheduling.

In the context of scheduling a critical board meeting involving stakeholders from diverse geographical locations, a comprehensive weather report revealed the likelihood of significant snowstorms affecting the travel routes and meeting venue. This prompted the organizers to reschedule the meeting, forestalling potential disruptions and ensuring maximum attendance.

Incorporating weather reports in event management

An illustrative example of utilizing weather reports can be observed in the planning of an open-air corporate retreat. By leveraging detailed weather forecasts, the organizers identified a window of favorable weather conditions, ensuring minimal disruptions and optimal comfort for all attendees throughout the event.

Best practices of weather report

Effective Implementation

- Integrate weather reports into meeting planning processes from the initial stages, considering potential weather-related impacts on venue selection, travel logistics, and participant comfort.

- Utilize reliable meteorological sources and tools to access accurate and up-to-date weather information, ensuring informed decision-making throughout the planning and execution stages of meetings.

Informed Decision Making

- Encourage proactive consideration of weather-related factors when setting meeting dates and locations, minimizing the likelihood of disruptions and enhancing overall preparedness.

- Communicate weather-related information effectively to all meeting participants, ensuring that they are aware of potential weather challenges and the organization's contingency plans.

Challenges and solutions

Unpredictable Weather Patterns

Challenge : Unpredictable weather patterns can pose significant challenges to meeting planning, potentially leading to last-minute disruptions and inconveniences for participants.

Solution : Establish flexible meeting schedules and alternate plans to accommodate unexpected weather changes, mitigating the impact of unpredictable weather patterns on meeting logistics.

Technological Dependencies

Challenge : Dependence on technology for accessing weather reports can present challenges, particularly in instances where technical issues or inaccurate data affect decision-making processes.

Solution : Diversify the sources of weather information and consider professional meteorological services to ensure reliable and comprehensive data, reducing the reliance on a single technological platform for weather reports.

In conclusion, weather reports are indispensable tools for ensuring effective professional communication and seamless meeting planning. By understanding their definition, significance, and best practices, organizations can proactively navigate challenges posed by varying weather conditions, ultimately contributing to the success of their meetings and events.

People also ask (faq)

How frequently should weather reports be monitored when scheduling meetings.

Weather reports should be monitored periodically in the build-up to meetings, especially during seasons or in regions where weather conditions are prone to rapid changes. Frequent monitoring, particularly closer to the meeting date, enables organizers to make informed decisions based on the latest meteorological data.

How do weather reports influence outdoor meeting and event planning?

Weather reports significantly influence outdoor meeting and event planning by providing critical information regarding potential weather-related disruptions. Organizers utilize this data to mitigate risks, plan for contingencies, and ensure optimal comfort and safety for all participants.

Are there specialized tools for accessing detailed weather information tailored for business meetings?

Yes, there are specialized weather services and applications designed for businesses and event planners that offer tailored meteorological information, including specific weather forecasts for meeting locations and durations. These tools provide in-depth insights to aid in making informed decisions based on comprehensive weather data.

What are the potential liabilities associated with not considering weather reports in meeting planning?

Failure to consider weather reports in meeting planning can lead to various liabilities, including disruptions resulting from adverse weather conditions, compromised attendee safety, and financial implications due to cancellations or rescheduling. This highlights the importance of integrating weather reports into meeting planning processes.

Can historical weather data be utilized to forecast future meeting conditions?

Yes, historical weather data is valuable in forecasting future meeting conditions, providing insights into typical weather patterns during specific times of the year and geographical locations. By analyzing historical data, organizers can anticipate potential challenges and make informed decisions for upcoming meetings.

Incorporating Meteorological Insights for Productive Meetings

I hope the article meets your expectations!

Lark, bringing it all together

All your team need is Lark

Explore More in Meeting Glossary

- All Activities

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Conference of the Parties (COP)

- Events and Meetings

- News Portal

- Media Releases

- Latest Publications

- Publication Series

- Fact Sheets

- Photo Galleries

- WMO Community

- The Secretariat

- Our Mandate

- WMO Members

- Liaison Offices

- Gender Equality

- Partnerships

- Resource Mobilization

- History of IMO and WMO

- Finance and Accountability

- World Meteorological Day

- WMO Building

Weather is the state of the atmosphere at a particular time, as defined by the various meteorological elements, including temperature, precipitation, atmospheric pressure, wind and humidity.

Weather describes short term events and differs from climate, which describes the average weather conditions for a particular location, over long periods of time, usually years or decades. For example, to obtain information about typical climate conditions a climatological standard normal is computed using data for a period of 30 years.

Weather is an hourly, daily phenomenon that affects every aspect of our lives. Therefore, we need weather forecasts to know what to wear, to plan our day and to prepare for the weather-related hazards that may lie ahead.

Weather forecasts provide essential information to support decision-making in many other areas, including: • safe transportation on land, by sea and in the air, • freshwater resources management, • sport, adventure and tourism, • agriculture, building infrastructure and energy management, • taking lifesaving, timely action in the face of impending natural hazards such as tropical cyclones, floods, etc.

Weather might refer to sunshine, rain, snow, hail, sleet, mist, blizzards, storms, and similar phenomena. Extreme weather events can be any severe or unusual weather event that happens outside normal patterns, or an expected weather event that happens with high intensity during its usual circulation.

Some extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, have become more frequent and more impactful in the past years, due to human-induced climate change and increased global warming.

Visit the Topic page Extreme weather to find out more about extreme weather events and their impacts.

WMO's response

WMO coordinates the worldwide efforts that are a prerequisite to produce accurate and timely weather forecasts.

WMO works with Members and their National Meteorological and Hydrological Services to coordinate the global network of Earth system observations, free and open exchange of data, continuous research, and global, regional and national data-processing for numerical weather prediction - all required to deliver accurate, timely weather forecasts and services.

Each contribution counts and improves the weather forecasts. The results are far greater than the sum of its parts and could not be achieved by any one Member on its own.

WMO presides over the World Weather Information Service , which presents weather observations, weather forecasts and climatological information for selected cities supplied by National Meteorological & Hydrological Services (NMHSs) worldwide.

WMO also presides over the Severe Weather Information Centre . The website is based on advisories issued by Regional Specialized Meteorological Centres (RSMCs) and Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres (TCWCs), and official warnings issued by National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) for their respective countries or regions.

Related activities

Global basic observing network (gbon), public weather services (pws), severe weather forecasting programme (swfp), wmo integrated processing and prediction system (wipps) , world weather research programme (wwrp), related topics, extreme weather, related news.

WMO Regional Association for Africa seeks to strengthen early warnings and climate services

WMO Infrastructure Commission faces the future

Closing the gaps in the observing network

WMO steps up coordination to protect vital radio frequency bands

Meteorological and hydrological infrastructure is the backbone of WMO

Weather, Climate, Marine and Hydrological Services: SERCOM-3 Day 3

NOAA forecasters increase Atlantic hurricane season prediction to ‘above normal’

WMO Executive Council meets

Weather forecasting enters new era

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ weth -er ]

- the state of the atmosphere with respect to wind, temperature, cloudiness, moisture, pressure, etc.

We've had some real weather this spring.

The radio announcer will read the weather right after the commercial.

She remained a good friend in all weathers.

verb (used with object)

to weather lumber before marketing it.

These crumbling stones have been weathered by the centuries.

to weather a severe illness.

to weather a cape.

- Architecture. to cause to slope, so as to shed water.

verb (used without object)

- to undergo change, especially discoloration or disintegration, as the result of exposure to atmospheric conditions.

a coat that weathers well.

It was a difficult time for her, but she weathered through beautifully.

- the day-to-day meteorological conditions, esp temperature, cloudiness, and rainfall, affecting a specific place Compare climate

a weather ship

- a prevailing state or condition

- (of a vessel) to roll and pitch in heavy seas

- foll by of to carry out with great difficulty or unnecessarily great effort

- not in good health

- intoxicated

the weather anchor

- to expose or be exposed to the action of the weather

- to undergo or cause to undergo changes, such as discoloration, due to the action of the weather

- intr to withstand the action of the weather

- whenintr, foll by through to endure (a crisis, danger, etc)

- tr to slope (a surface, such as a roof, sill, etc) so as to throw rainwater clear

to weather a point

/ wĕth ′ ər /

- The state of the atmosphere at a particular time and place. Weather is described in terms of variable conditions such as temperature, humidity, wind velocity, precipitation, and barometric pressure. Weather on Earth occurs primarily in the troposphere, or lower atmosphere, and is driven by energy from the Sun and the rotation of the Earth. The average weather conditions of a region over time are used to define a region's climate.

- The daily conditions of the atmosphere in terms of temperature, atmospheric pressure , wind, and moisture.

Discover More

Derived forms.

- ˌweatheraˈbility , noun

- ˈweatherer , noun

Other Words From

- weather·er noun

Word History and Origins

Origin of weather 1

Idioms and Phrases

- somewhat indisposed; ailing; ill.

- suffering from a hangover.

Many fatal accidents are caused by drivers who are under the weather.

More idioms and phrases containing weather

Example sentences.

The weather is pretty warm year-round, though, hovering at around 75 degrees.

The shutoffs that began late Monday are a fairly new and controversial practice, and their use last year triggered investigations while utilities defended them as necessary in the face of increasingly wild weather.

The US is experiencing one of its worst years for wildfire outbreaks thanks to hot weather and a lack of firefighters.

While restrictions have eased in some parts of the country, the situation—particularly as we head into cooler fall weather and back to school—is proving to be fluid.

And, of course, there have been far more disasters caused by extreme weather than terrorist attacks.

Frustrating as regulars find these fair-weather exercise interlopers, they were also all beginners once, he says.

That ground hold was to stop you flying through weather that could kill you and everyone else aboard.

Did the airline file a flight plan that took account of the weather en route from Surabaya, Indonesia, to Singapore?

These days weather should never cause a commercial airliner to crash.

The pilot asked air-traffic control for permission to climb from 32,000 to 38,000 feet to avoid the bad weather.

In the drawing-room things went on much as they always do in country drawing-rooms in the hot weather.

Blamed ef I'd lived in a country all my life, ef I wouldn't know better'n to git caught out in such weather's this!

An old weather-beaten bear-hunter stepped forward, squirting out his tobacco juice with all imaginable deliberation.

That the weather being calm, he rowed round me several times, observed my windows and wire-lattices that defenced them.

Decomposition sets in rapidly, especially in warm weather, and greatly interferes with all the examinations.

Related Words

- get through

Weather Vs. Climate

What’s the difference between weather and climate .

Weather refers to short-term atmospheric conditions—the temperature and precipitation on a certain day, for example. Climate refers to the average atmospheric conditions that prevail in a given region over a long period of time—whether a place is generally cold and wet or hot and dry, for example. It can also refer to the region or area that has a particular climate .

Weather can also be a verb, meaning to expose something to harsh conditions (such as by placing it outside, in the weather ), often in order to change it in some way, as in We need to weather this leather to soften it . It can also mean to endure a storm or, more metaphorically, a negative or dangerous situation, as in We will simply have to weather the recession . As nouns, both weather and climate can be used figuratively to refer to the general (nonliteral) atmosphere of a place or situation, as in phrases like political climate and fair-weather friend .

In scientific terms, both weather and climate are about atmospheric conditions like temperature, precipitation, and other factors. But they differ in scale. Weather involves the atmospheric conditions and changes we experience in the short term, on a daily basis. Rain today, sun tomorrow, and snow next month—that’s weather . Climate involves average atmospheric conditions in a particular place over a long period of time (this is often understood to mean 30 years or more). Is the place where you live consistently rainy and cool? Is it always 72 degrees and sunny? That’s climate .

So, when you’re making small talk about whether it’s rainy or sunny that day, you’re discussing the weather . If you’re complaining that it’s always way too hot where you live, all year round, you’re discussing your regional climate .

Changes to climate —even an average temperature rise of a few degrees—can alter the weather patterns that we’re accustomed to. More extreme and more frequent storms, floods, and droughts are some examples of weather events that are being fueled by a warming of the climate .

Here’s an example of weather and climate used correctly in a sentence.

Example: When you live in an extremely dry climate, a rare day of rainy weather is thrilling.

Want to learn more? Read the full breakdown of the difference between weather and climate .

Quiz yourself on weather vs. climate !

Should weather or climate be used in the following sentence?

This week’s hot _____ has brought people out to the pool in droves.

Definitions and idiom definitions from Dictionary.com Unabridged, based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2023

Idioms from The American Heritage® Idioms Dictionary copyright © 2002, 2001, 1995 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

Weather or Climate ... What's the Difference?

While weather refers to short-term changes in the atmosphere, climate refers to atmospheric changes over longer periods of time, usually 30 years or more.

Earth Science, Meteorology

Lightning Grand Canyon

Weather—like this lightning storm in the Grand Canyon, Arizona—refers to short-term changes in the atmosphere, whereas climate refers to atmospheric changes over longer periods of time.

Photograph by Michael Nichols

Contrary to popular opinion, science is not divided on the issue of climate change . The overwhelming majority (97 percent) of scientists agree that global warming is real, and that it is largely caused by human activity. And yet we seem to be experiencing record-breaking cold winters; in January 2019, a polar vortex plunged parts of North America into Arctic conditions. It may seem counterintuitive but cold weather events like these do not disprove global warming , because weather and climate are two different things. Understanding Weather Weather refers to the short-term conditions of the lower atmosphere , such as precipitation , temperature, humidity , wind direction, wind speed, and atmospheric pressure . It could be sunny, cloudy, rainy, foggy, cold, hot, windy, stormy, snowing … the list goes on. The sun drives different types of weather by heating air in the lower atmosphere at varying rates. Warm air rises and cold air rushes in to fill its place, causing wind. These winds, along with water vapor in the air, influence the formation and movement of clouds, precipitation , and storms. The atmospheric conditions that influence weather are always fluctuating, which is why the weather is always changing. Meteorologists analyze data from satellites, weather stations, and buoys to predict weather conditions over the upcoming days or weeks. These forecasts are important because weather influences many aspects of human activity. Sailors and pilots, for example, need to know when there might be a big storm coming, and farmers need to plan around the weather to plant and harvest crops. Firefighters also keep track of daily weather in order to be prepared for the likelihood of forest fires. Weather forecasts are also useful for military mission planning, for features of trade, and for warning people of potentially dangerous weather conditions. Understanding Climate While weather refers to short-term changes in the atmosphere , climate refers to atmospheric changes over longer periods of time, usually defined as 30 years or more. This is why it is possible to have an especially cold spell even though, on average, global temperatures are rising. The former is a weather event that takes place over the course of days, while the latter indicates an overall change in climate , which occurs over decades. In other words, the cold winter is a relatively small atmospheric perturbation within a much larger, long-term trend of warming. Despite their differences, weather and climate are interlinked. As with weather , climate takes into account precipitation , wind speed and direction, humidity , and temperature. In fact, climate can be thought of as an average of weather conditions over time. More importantly, a change in climate can lead to changes in weather patterns. Climate conditions vary between different regions of the world and influence the types of plants and animals that live there. For example, the Antarctic has a polar climate with subzero temperatures, violent winds, and some of the driest conditions on Earth. The organisms that live there are highly adapted to survive the extreme environment. By contrast, the Amazon rainforest enjoys a tropical climate . Temperatures are consistently warm with high humidity , plenty of rainfall, and a lack of clearly defined seasons. These stable conditions support a very high diversity of plant and animal species, many of which are found nowhere else in the world. Our Climate Is Changing The global climate has always been in a state of flux. However, it is changing much faster now than it has in the past, and this time human activities are to blame. One of the leading factors contributing to climate change is the burning of fossil fuels such as coal, gas, and oil, which we use for transport, energy production, and industry. Burning fossil fuels releases large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere ; CO2 is one of a group of chemicals known as greenhouse gases . They are so named because they allow heat from the sun to enter the atmosphere but stop it from escaping, much like the glass of a greenhouse. The overall effect is that the global temperature rises, leading to a phenomenon known as global warming . Global warming is a type of climate change , and it is already having a measurable effect on the planet in the form of melting Arctic sea ice, retreating glaciers , rising sea levels, increased frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, and a change in animal and plant ranges. The planet has already heated by about 0.8°C (1.4°F) in the last century, and temperatures have continued to rise. Scientists cannot directly attribute any specific extreme weather event to climate change , but they are certain that climate change makes extreme weather more likely. In 2018, at least 5,000 people were killed and 28.9 million more required aid as a result of extreme weather events. The Indian state of Kerala was devastated by flooding; California was ravaged by a series of wildfires; and the strongest storm of the year, super typhoon Mangkhut, crashed into the Philippines. It is likely that more frequent and more severe weather events are on the horizon. Climate change is not a new concept, and yet little seems to have been done about it on a global scale. The greenhouse effect was first discovered in the 1800s, but it was not until 1988 that the global community galvanized to form the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Since then, leaders from around the world have committed to a series of goals to combat climate change , the latest of which is the Paris Agreement in which 185 countries have pledged to stop global temperatures from rising by more than 2°C (3.6°F) above preindustrial levels. In 2015, all United Nations member states agreed to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) designed to “provide a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.” SDG 13 in particular commands member states to “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.” Part of the reason the global community has been so slow to act on climate change could be the confusion surrounding distinctions between weather and climate . People are reluctant to believe that the climate is changing when they can look outside their window and see for themselves that the weather appears typical.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of forecast

(Entry 1 of 2)

transitive verb

intransitive verb

Definition of forecast (Entry 2 of 2)

- prognosticate

- forecasting

- foretelling

- prognosticating

- prognostication

- prophesy

- soothsaying

- vaticination

foretell , predict , forecast , prophesy , prognosticate mean to tell beforehand.

foretell applies to the telling of the coming of a future event by any procedure or any source of information.

predict commonly implies inference from facts or accepted laws of nature.

forecast adds the implication of anticipating eventualities and differs from predict in being usually concerned with probabilities rather than certainties.

prophesy connotes inspired or mystic knowledge of the future especially as the fulfilling of divine threats or promises.

prognosticate is used less often than the other words; it may suggest learned or skilled interpretation, but more often it is simply a colorful substitute for predict or prophesy .

Examples of forecast in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'forecast.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

15th century, in the meaning defined at transitive sense 1a

1527, in the meaning defined at sense 2

Articles Related to forecast

'Broadcast' or 'Broadcasted'?

On the conjugation of an irregular verb

Dictionary Entries Near forecast

forecarriage

forecastingly

Cite this Entry

“Forecast.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/forecast. Accessed 7 Jun. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of forecast.

Kids Definition of forecast (Entry 2 of 2)

More from Merriam-Webster on forecast

Nglish: Translation of forecast for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of forecast for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

What's the difference between 'fascism' and 'socialism', more commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - june 7, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, etymologies for every day of the week, games & quizzes.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

Illustration of cold sore on different skin colors. A cold sore is a cluster of fluid-filled blisters. Healing often occurs in two to three weeks without scarring. Cold sores are sometimes called fever blisters.

Cold sores, or fever blisters, are a common viral infection. They are tiny, fluid-filled blisters on and around the lips. These blisters are often grouped together in patches. After the blisters break, a scab forms that can last several days. Cold sores usually heal in 2 to 3 weeks without leaving a scar.

Cold sores spread from person to person by close contact, such as kissing. They're usually caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), and less commonly herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2). Both of these viruses can affect the mouth or genitals and can be spread by oral sex. The virus can spread even if you don't see the sores.

There's no cure for cold sores, but treatment can help manage outbreaks. Prescription antiviral medicine or creams can help sores heal more quickly. And they may make future outbreaks happen less often and be shorter and less serious.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to Home Remedies

A cold sore usually passes through several stages:

- Tingling and itching. Many people feel itching, burning or tingling around the lips for a day or so before a small, hard, painful spot appears and blisters form.

- Blisters. Small fluid-filled blisters often form along the border of the lips. Sometimes they appear around the nose or cheeks or inside the mouth.

- Oozing and crusting. The small blisters may merge and then burst. This can leave shallow open sores that ooze and crust over.

Symptoms vary, depending on whether this is your first outbreak or a recurrence. The first time you have a cold sore, symptoms may not start for up to 20 days after you were first exposed to the virus. The sores can last several days. And the blisters can take 2 to 3 weeks to heal completely. If blisters return, they'll often appear at the same spot each time and tend to be less severe than the first outbreak.

In a first-time outbreak, you also might experience:

- Painful gums.

- Sore throat.

- Muscle aches.

- Swollen lymph nodes.

Children under 5 years old may have cold sores inside their mouths. These sores are often mistaken for canker sores. Canker sores involve only the mucous membrane and aren't caused by the herpes simplex virus.

When to see a doctor

Cold sores generally clear up without treatment. See your health care provider if:

- You have a weak immune system.

- The cold sores don't heal within two weeks.

- Symptoms are severe.

- The cold sores often return.

- You have gritty or painful eyes.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Cold sores are caused by certain strains of the herpes simplex virus (HSV). HSV-1 usually causes cold sores. HSV-2 is often the cause of genital herpes. But either type can spread to the face or genitals through close contact, such as kissing or oral sex. Shared eating utensils, razors and towels can also spread HSV-1 .

Cold sores are most likely to spread when you have oozing blisters. But you can spread the virus even if you don't have blisters. Many people who are infected with the virus that causes cold sores never develop symptoms.

Once you've had a herpes infection, the virus can hide in nerve cells in the skin and may cause another cold sore at the same place as before. A return of cold sores may be triggered by:

- Viral infection or fever.

- Hormonal changes, such as those related to a menstrual period.

- Being in the sun or wind.

- Changes in the immune system.

- Injury to the skin.

- Video: 3 things you didn't know about cold sores

Ian Roth: Cold sores on the lips can be embarrassing and tough to hide. But, turns out, you might not have a reason to be embarrassed.

Pritish Tosh, M.D., Infectious Diseases, Mayo Clinic: About 70-plus percent of the U.S. population has been infected with herpes simplex 1. Now, a very small percentage of those people will actually develop cold sores.

Ian Roth: Dr. Pritish Tosh, an infectious diseases specialist at Mayo Clinic, says genetics determines whether a person will develop cold sores.

Dr. Tosh: A proportion of the population, they don't quite have the right immunologic genes and things like that and so they're not able to handle the virus as well as other people in the population.

Ian Roth: The problem is people can spread the herpes virus whether they develop cold sores or not. Herpes virus spreads through physical contact like kissing, sharing a toothbrush — even sharing a drinking glass — or through sexual contact.

Dr. Tosh: Since the number of people who are infected but don't have symptoms vastly outnumber the people who are infected and have symptoms, most new transmissions occur from people who have no idea that they are infected.

For the Mayo Clinic News Network, I'm Ian Roth.

Risk factors

Almost everyone is at risk of cold sores. Most adults carry the virus that causes cold sores, even if they've never had symptoms.

You're most at risk of complications from the virus if you have a weak immune system from conditions and treatments such as:

- HIV / AIDS .

- Atopic dermatitis (eczema).

- Cancer chemotherapy.

- Anti-rejection medicine for organ transplants.

Complications

In some people, the virus that causes cold sores can cause problems in other areas of the body, including:

- Fingertips. Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can be spread to the fingers. This type of infection is often referred to as herpes whitlow. Children who suck their thumbs may transfer the infection from their mouths to their thumbs.

- Eyes. The virus can sometimes cause eye infection. Repeated infections can cause scarring and injury, which may lead to vision problems or loss of vision.

- Widespread areas of skin. People who have a skin condition called atopic dermatitis (eczema) are at higher risk of cold sores spreading all across their bodies. This can become a medical emergency.

Your health care provider may prescribe an antiviral medicine for you to take on a regular basis if you develop cold sores more than nine times a year or if you're at high risk of serious complications. If sunlight seems to trigger your condition, apply sunblock to the spot where the cold sore tends to form. Or talk with your health care provider about using an oral antiviral medicine before you do an activity that tends to cause a cold sore to return.

Take these steps to help avoid spreading cold sores to other people:

- Avoid kissing and skin contact with people while blisters are present. The virus spreads most easily when the blisters leak fluid.

- Avoid sharing items. Utensils, towels, lip balm and other personal items can spread the virus when blisters are present.

- Keep your hands clean. When you have a cold sore, wash your hands carefully before touching yourself and other people, especially babies.

- AskMayoExpert. Cold sores (herpes simplex infection). Mayo Clinic; 2019.

- Dinulos JGH. Warts, herpes simplex, and other viral infections. In: Habif's Clinical Dermatology. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 7, 2020.

- Herpes simplex. American Academy of Dermatology. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/a-z/herpes-simplex-overview. Accessed April 7, 2020.

- Ferri FF, et al., eds. Herpes simplex. In: Ferri's Fast Facts in Dermatology: A Practical Guide to Skin Diseases and Disorders. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 7, 2020.

- Kermott CA, et al., eds. Canker sores. In: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies. 2nd ed. Time; 2017.

- Kermott CA, et al., eds. Cold sores. In: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies. 2nd ed. Time; 2017.

- Gibson LE (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. April 6, 2015.

- Lemon balm. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Lysine. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Rhubarb. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Propolis. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Bauer BA, ed. Making wellness the focus of care. In: Mayo Clinic Guide to Integrative Medicine. Time; 2017.

- Klein RS. Treatment of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in immunocompetent patients. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Hargitai IA. Painful oral lesions. Dental Clinics of North America. 2018; doi.10.1016/j.cden.2018.06.002.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

We’re transforming healthcare

Make a gift now and help create new and better solutions for more than 1.3 million patients who turn to Mayo Clinic each year.

Heat advisory expanded to 3 Florida counties, with record highs expected. Here's where

There are some records you just don't want to see broken.

Record high temperatures is one of them.

But that's what is happening right now across Florida, and record high temperatures are expected through the weekend.

Early Friday morning, a heat advisory was issued for areas of in Miami-Dade County away from the coast. The heat advisory is in effect from 10 a.m. through 6 p.m. Heat indices between 104 and 108 are likely for most of South Florida. Some areas could see a heat index of 110 , according to the National Weather Service Miami.

By 10 a.m., the heat advisory had been expanded to include Palm Beach and Broward counties.

What is a heat advisory?

A heat advisory is one of several types of health alerts issued by the National Weather Service. A heat advisory is issued within 12 hours of the onset of extremely dangerous heat conditions.

The general rule of thumb for this advisory is when the maximum heat index temperature is expected to be 100 degrees or higher for at least two days, and nighttime air temperatures will not drop below 75 degrees. These criteria vary across the country, especially for areas that are not used to dangerous heat conditions.

In Florida, except for Miami-Dade County, the National Weather Services offices around the state would issue a heat advisory if the heat index is expected to reach 108 to 112 degrees. The National Weather Service Miami said Miami/Dade County wanted a lower threshold for an advisory for its population, which was set at 105 degrees.

If a heat advisory is issued, take precautions to avoid heat illness. If you don't take precautions, you may become seriously ill or even die.

What is the heat index mean and why is it important?

The heat index measures how how it really feels outside , according to the National Weather Service . It's sort of the summer equivalent of the wind chill factor our more northerly neighbors watch in the winter.

The heat index is calculated based on two factors:

- Air temperature

- Relative humidity

Important point: Heat index values were devised for shady, light wind conditions. Exposure to full sunshine can increase heat index values by up to 15 degrees, according to the National Weather Service.

What is an unsafe heat index? What number is dangerous?

In general, dange r ous conditions would occur as soon as the heat index hits 105 degrees.

Conditions are considered extremely dangerous if the heat index is 126 degrees or higher.

Weather alerts issued in Florida

Florida weather forecast: record heat followed by rain.

Temperatures this week, while feeling really hot, actually have been close to normal, according to the Florida Public Radio Emergency Network.

That's changing.

Starting Thursday, winds shifted to out of the south in response to a front moving toward Florida. Those winds will push temperatures into the mid to upper 90s. It's also bringing tropical moisture, which will make conditions outside feel very muggy, according to the Florida Public Radio Emergency Network.

Bottom line: temperatures will feel between 105 and 110 across much of the state.

By Friday, winds are expected to come out of the southwest, dumping heat gathered over land to the east coast of Florida, from the Space Coast south to Miami.

"Miami and Fort Lauderdale could break new records and the high temperature is likely to reach 95 degrees on Friday. The afternoon temperature for West Palm Beach is also forecast to beat a record established in 1998 of 94," the Florida Public Radio Emergency Network said.

Conditions won't improve over the weekend.

"On Saturday and Sunday, record temperatures will be possible across the I-4 corridor, from Tampa to Orlando, and along I-95, from Melbourne to Miami. Highs could range between 94 and 97 and with the humidity, the temperatures will feel as if they were above 105."

Up to 5 inches of rain possible across some portions of Florida next week

Numerous downpours and high rainfall are forecast from the start through the middle of the week.

"As of now, most models show the highest rainfall across southern Florida. Some areas could receive up to 5 inches between Sunday and Wednesday," the Florida Public Radio Emergency Network said.

Language selection

- Français fr

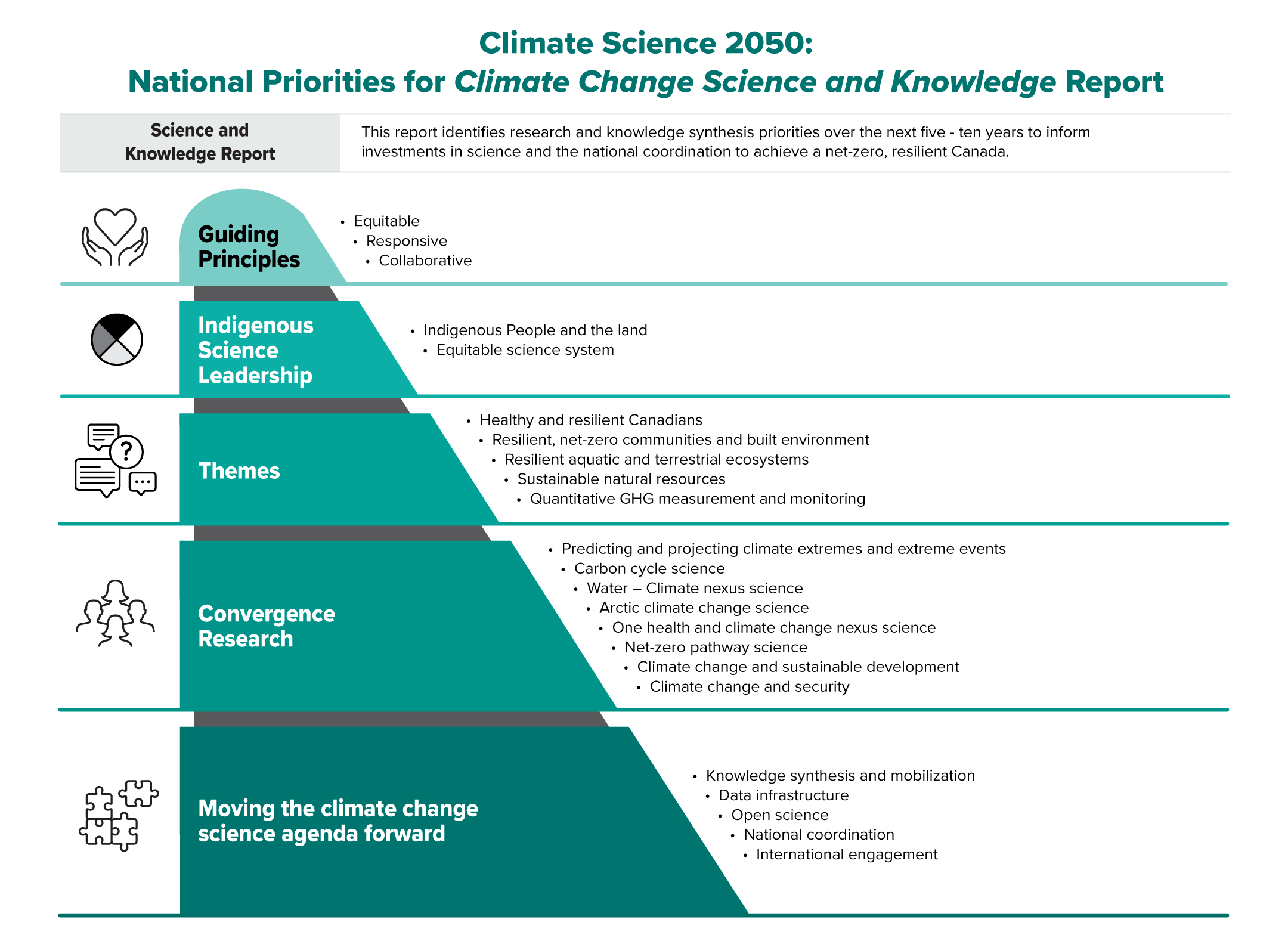

Climate Science 2050: National Priorities for Climate Change Science and Knowledge Report

Chapter 1 informing climate action.

Science provides the evidence and data on the impacts of climate change, but it also gives us the tools and knowledge as to how we need to address it. (...) We are now clearly in the era of implementation, and that means action. But none of this can happen without data, without evidence to inform decisions, or the science that supports programs and policies. — Simon Stiell, Executive Secretary, UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (2022)

The changing climate is impacting Canada’s economy, infrastructure, environment, health, and social and cultural well-being. Climate change science adds to our understanding of how to reduce future warming by mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, how to reduce the risks from warming, and how to reduce vulnerability to climate change. Thus, it supports climate action based on evidence.

Implementation and coordination of science activities must reflect the diversity of Canadians’ regional and equity-based experiences of climate change. Climate change multiplies risks for all communities and regions, but may do so in different ways, and the impacts may be felt differently. Science planning must also address the broader context of Canada’s progress toward a circular economy and sustainable development.

As our needs for knowledge and information evolve, the strategic planning and implementation of science must also evolve to reflect the multiple and distinct perspectives of all people and communities impacted by climate change and climate action.

1.1 Canada’s first Climate Science 2050: National Priorities for Climate Change Science and Knowledge report

The scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change is clear, as is the need for urgent action to reach net-zero to avoid the most severe impacts. Footnote 1 However, scientific capacity must be focused to bring evidence to where it is most needed to guide action, to identify new opportunities to reduce GHG emissions, to develop adaptation responses, and to measure progress. Science and knowledge Footnote 2 play an essential role in helping us navigate the complex intersections, synergies, and trade-offs inherent in building a thriving, climate-resilient, net-zero Footnote 3 Canada that is just and equitable.

The Climate Science 2050: National Priorities for Climate Change Science and Knowledge Report (CS2050) was developed under the leadership of Environment and Climate Change Canada. It is a “what we heard” report, summarizing the results of two years of extensive engagement with more than 500 climate program leaders across federal departments and agencies and provincial and territorial governments, as well as academics and experts from the Canadian community of climate change science, and Indigenous organizations and scholars. As such, it takes its place alongside other national climate policy and planning initiatives. It identifies the science priorities—across various disciplines, from carbon cycle and Earth system science to impacts on health, infrastructure, and biodiversity—to inform science investments needed now for science results over the next six years (to 2030), and to guide ongoing science coordination.

The priorities outlined in this report reflect the information needs of those developing climate policy and programs across all levels of government. The priorities also reflect expert opinion on new lines of scientific inquiry that will enable decision makers to use emerging knowledge, data, tools, and information. In all instances, the science priorities will help advance ongoing efforts to mitigate GHG emissions and adapt to climate change, including setting emissions-reduction targets, refining existing policy approaches, and evaluating progress to date. The audience for this report is all those who have an opportunity to shape climate change science activities across Canada, including strategic planning, funding, coordination, and implementation.

Both Western and Indigenous science contributed to the report through science expert roundtables, stakeholder surveys, webinars, and numerous discussions with partners, experts, and stakeholders. This science is needed to ensure that investments in mitigation measures, adaptation, infrastructure resilience, and disaster recovery are as targeted and effective as possible. Evidence-based action limits future risk and associated costs. Canada is already experiencing costs as climate extremes and extreme weather events have become more frequent, intense, and long-lasting. These costs amount to about 5% to 6% of annual economic growth. Footnote 4 The floods, storm surge, wildfires, and extreme heat, winds, and droughts of the last two decades have translated to economic loss and financial liabilities. Going forward, these effects are projected to become more severe. Some portion of these future losses can be avoided through science-informed adaptation and mitigation.

CS2050, published in December 2020, was an important step for Canada, taking stock for the first time of the breadth of collaborative and transdisciplinary knowledge required to inform climate action. This report is the next step, identifying the most pressing science activities to enable evolution of climate action consistent with our best understanding of the challenge. Mitigation and adaptation solutions must continue to evolve as the evidence underpinning these solutions is strengthened.

Beyond guiding science investments, the process to develop this report involved ongoing dialogue on climate change science policy to improve delivery of science results that inform both mitigation and adaptation. Last, creating this national multi-, inter-, and transdisciplinary science and knowledge report brings strategic science planning into broader planning for climate action, aligning Canada with other international approaches.

1.2 The science policy context

This science and knowledge report complements other federal mitigation and adaptation plans for Canada. Canada’s strengthened climate plan, A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy , describes federal policies, programs, and investments to achieve mitigation and adaptation goals. Canada’s commitment to achieving emission-reduction targets is set out in the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act , which received Royal Assent in June 2021. The Act sets out Canada’s 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement of 40% to 45% below 2005 levels, as well as Canada’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, and it requires the Government of Canada to set additional targets every five years to 2050. The Act specifies that future milestone targets must be informed by the best available science. As an important first step under the Act, the Government of Canada published the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) in March 2022. The ERP is a sector-by-sector roadmap with measures and strategies to achieve Canada’s 2030 target and to lay the foundation to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. The 2030 ERP builds on the progress of past climate plans, including A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy (2020) and the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (2016) .

Even with rapid and deep global emissions reductions, some further warming in Canada is inevitable ( Canada’s Changing Climate Report , 2019). Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy recognizes the current impacts and risks of climate change through both slow-onset changes and extreme events and lays out the objectives for building resilience across Canada. A foundational principle of the strategy is that science will inform forward-looking, effective, and targeted actions to build resilience.

The Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act and Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy set the overarching framework guiding the climate change science priorities identified in this report. The priorities have multiple benefits, tackling many concurrent climate-related challenges facing society. In particular, this report recognizes the contributions and benefits of science to the numerous climate-related challenges facing society, including in the areas of biodiversity conservation, water security, emergency preparedness, and sustainable development. Thus, climate change science supports the goals and objectives of multiple national and international policy commitments and strategies (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Schematic “crosswalk” between this report and its national policy context, illustrating the policies and programs that benefit from climate change science and knowledge .

A graphic that outlines the policies and programs that benefit from climate change science and knowledge:

- Wildland Fire Strategy

- Arctic Northern Policy Framework

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

- Indigenous Climate Leadership

- Blue Economy Strategy

- Sustainable Agriculture Strategy

- GHG National Inventory Reporting

- Canada Water Agency

- Methane Strategy

- Canada Green Building Strategy

- Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership

- Climate Services and Climate Data Strategy

- Other jurisdictional actions

- Adaptation Action Plan

- Canada’s 2030 Agenda National Strategy

- Convention on Biological Diversity

- Nature Smart Climate Solutions Fund

- Emergency Management Strategy for Canada: Towards a Resilient 2030

- Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements program

- Canadian Dialogue on Wildland Fire and Forest Resilience

- Food Policy for Canada

- Flood Hazard Identification and Mapping Program

This report addresses the need for investments in science at all scales, from discipline-focused discovery science to transdisciplinary research frameworks. It identifies science priorities that deliver ongoing results, including knowledge synthesis and mobilization, to provide information and data to respond to the urgent need for climate action. Hence, this report creates space for transdisciplinary science and participatory research, both critical to addressing knowledge gaps. The report identifies what science activities are needed, rather than how those activities should be implemented. While decision making and climate action (i.e., climate services, policies, and regulations) are crucial and must be informed by climate change science and knowledge, they fall outside the scope of this report.

Furthermore, this report does not address clean technology research and development (R&D), as there is already considerable planning and investment in these areas, such as the Federal Energy R&D Science Planning Process that brought together federal scientist and external stakeholders across 12 focus areas in energy R&D. This process is informing the next five years of federal energy R&D activities, some of which are complementary. The concurrent planning for clean technology, energy, and economics are outside the scope of this report. However, understanding the potential of renewable energy, carbon sequestration technologies, and other mitigation strategies is necessary to determine their potential in Canada to meet our net-zero objectives. This understanding informs net-zero pathway science, which is in the scope of this report. Targeted and sector-specific science is not included here, but that does not mean it is unimportant. The work and guidance of the Net-Zero Advisory Body, the Canada Energy Regulator , and the Canadian Climate Institute are particularly important in guiding research and knowledge synthesis and mobilization activities in this area.

This report reflects the guiding principles for climate change science developed in 2020, which have further evolved in response to ongoing science policy dialogue and engagement (Box 1.1). These principles are intended to shape all aspects of science planning, coordination, funding, data collection, research, and knowledge synthesis and mobilization.

To achieve the guiding principles, the Government of Canada supports Indigenous approaches and ways of doing by acknowledging Indigenous science as part of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis knowledge systems and ways of knowing. All those in Indigenous and Western climate change science and knowledge should listen and work collaboratively and respectfully to achieve equity among knowledge systems, while increasing opportunities for Indigenous self-determination, in fulfillment of Canada’s commitment to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to Indigenous climate change science leadership (Chapter 3).

The following chapters outline the science needed to allow us to understand and assess potential impacts of climate change for Canada and the world, take informed and ambitious action, and reduce climate risk for a more resilient, net-zero Canada by 2050.

Box 1.1. Climate Science 2050 guiding principles

The guiding principles in CS2050 (published in December 2020) have directed development of this science and knowledge report. They offer guidance on how science planning, knowledge synthesis and mobilization, and research efforts can build on existing knowledge and understanding in a respectful, inclusive, and interdisciplinary way that benefits all Canadians. These principles continue to evolve, reflecting the discussions held and advice received in developing this report. These principles are to:

- Ensure equity of diverse knowledge systems , making space for Indigenous leadership and innovation, and recognizing that Indigenous knowledge is a distinct network of knowledge systems that cannot be integrated into Western science but can be bridged, braided, and woven to respectfully co-exist and co-create new knowledge.

- Embrace multi- and transdisciplinarity to produce science and knowledge that reflect the complexity and interconnections inherent in responding to climate change and that encompass different kinship systems and spiritual relationships with the land, oceans, and waterways.

- Emphasize collaboration across generations, disciplines, sectors, levels of government, organizations, and regions to bring together a range of experiences, perspectives, and areas of expertise.

- Adopt a flexible, adaptive approach in science and knowledge priorities to be responsive to emerging priorities, challenges, and opportunities.

- Apply an intersectional lens that considers how climate change intersects with various identity factors (e.g., race, class, gender) to develop solutions that tackle both climate change and inequity, while removing systemic barriers and promoting well-being.

- Respond to local and regional contexts, needs, priorities, protocols, cultures, and ways of knowing by involving communities affected by the research to produce tailored and effective adaptation and mitigation efforts.

- Further Indigenous self-determination in research to support an approach to climate change science that is holistic, place-based, and responsive, and that respects Indigenous sovereignty and ownership of data.

- Consider climate change mitigation, adaptation, and sustainable development in an integrated way to maximize multiple benefits and complementary, mutually reinforcing responses.

Chapter 2 Approach and methods

The approach and methods used to develop this report were holistic and grounded in societal outcomes, which the science informs. The report’s primary goal is to support net-zero and adaptation objectives. The identified science priorities also aim to achieve interconnected national goals for climate action, biodiversity conservation, and sustainable development. The primary drivers of science priority selection are relevance and responsiveness to information needs for climate change policies and programs. However, identification of priorities was also influenced by understanding of current knowledge gaps, anticipated scientific developments, and opportunities to advance science through increased national coordination and/or collaboration.

This report was developed through engagement with a broad range of climate program leaders across governments and sectors, as well as experts from the Canadian climate change science community, in 2021–2022. This built on the broader Government of Canada engagement on the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan and Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy.

This engagement process found that Canada should prioritize both foundational research, to address challenges in scientific disciplines, and transformative research, to address complex challenges that require the collective and integrated contributions from social, economic, natural, and health sciences. The key messages and findings from the engagement are synthesized in the science priorities presented in Chapters 3 to 6.

The full suite of science priorities addresses the information needs of users—those who design, implement, and evaluate climate policy and programs.

This chapter outlines how the report was developed, including engagement and prioritization of the science activities. Aligned with the guiding principles (Box 1.1), development of the report took a holistic approach, grounded in societal outcomes, which need to be informed by the science. Throughout the report’s development, the process emphasized advancing science to achieve domestic climate objectives and Canada’s sustainable development in a net-zero world. However, the report also anticipates opportunities for Canadian science to contribute to a broader international response to climate change and to climate-resilient development.

While Canada’s domestic net-zero and adaptation objectives drive this report, multiple benefits can also arise from these scientific efforts. The science activities outlined in the report are relevant to diverse climate-related challenges (Figure 1.1). Understanding of these challenges and connections with multiple benefits (e.g., for biodiversity, health, and sustainable development) also influenced the identification of science priorities.

The first CS2050 report (published in December 2020) took stock of the broad range of science aligned with climate action. This follow-up report prioritizes science activities and is intended to inform investments in research and knowledge synthesis and mobilization to align with ambitious climate action. This is similar to approaches taken in other countries with relevant jurisdictional, cultural, and/or geographical contexts. Many of the science priorities in this report represent a common science foundation for mitigation and adaptation planning, which are increasingly integrated. The common science foundation is designed to help guide these efforts so that they also become mutually reinforcing. As a result, this report identifies science priorities that span multiple disciplines, regions, and sectors, building on the initial CS2050 framework.

2.1 International examples

Understanding how other nations or international bodies have approached planning for climate change science can inform Canada’s approach. The core precept is that climate action should be based on the best possible scientific knowledge, in order to manage risk and inform effective mitigation strategies. To find international comparators, a number of science plans or strategic program plans were reviewed (below). No science plans from other jurisdictions were grounded in societal outcomes and informed both mitigation and adaptation from a holistic perspective, like the approach taken for this report.

- The European Union Joint Research Program consists of distinct research areas, which predominantly include mitigation-focused science, and an integrated sustainability research program. The Horizon Europe 2021–2024 strategic plan also includes climate science.

- The Danish Meteorological Research Institute hosts a National Centre for Climate Research , an interdisciplinary collaborative that emphasizes Danish priority topics, including the cryosphere, extreme weather, and green transition through renewable energy sources.

- There are many organizations involved in climate science in Australia , notably the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and the Bureau of Meteorology. The Australian Academy of Science is responsible for reviewing climate science capability and identifying the current position of the climate science sector and future climate research needs.

- In the United Kingdom , the Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme provides climate change science leadership and strategic planning, supported by the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy as well as the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. The UK Royal Society produces briefings on a range of topics to inform climate action and research priorities. Advice is coordinated through the UK Climate Change Committee .

- In the United States , the US Global Change Research Program , a collaboration of 13 US federal departments and agencies, is responsible for strategic science planning and science assessments. This is laid out in the Global Change Research Needs and Opportunities for 2022–2031 .

- In Austria , the Austrian Climate Research Programme guides climate research related to climate change impacts, adaptation, and mitigation.

- Aotearoa New Zealand reflects the Crown–Māori relationship under the Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi), recognizing the application of te reo Māori (the Māori language) and mātauranga Māori (the unique Māori way of viewing the world, encompassing both traditional knowledge and culture), within an environmental context and specifically in New Zealand’s National Adaptation Plan.

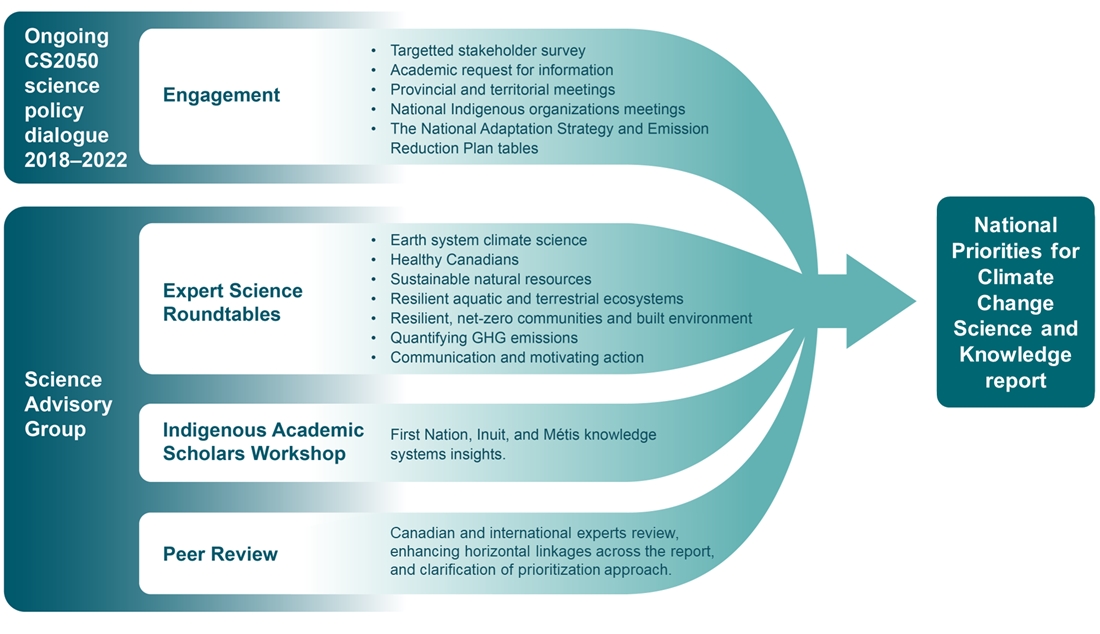

2.2 Engagement

Climate Science 2050: National Priorities for Climate Change Science and Knowledge was developed as part of an ongoing science policy dialogue, led by Environment and Climate Change Canada, that started in 2018 with engagement for the first CS2050 report. This process involved convening a broad range of climate program leaders from across governments and sectors, as well as experts from the Canadian climate change science community. In developing the report, it was important to address knowledge gaps identified by climate policy and decision-makers across jurisdictions to better understand their priorities for climate action and what information is most needed to help this climate action succeed. The scientific community was also asked to consider what new science or knowledge syntheses are needed to meet these information needs, and where future scientific developments will enable policy makers to fill knowledge gaps and achieve climate change goals.

Working with the Office of the Chief Science Advisor’s network of Departmental Science Advisors, a Science Advisory Group was established to guide engagement and report development, prioritization, and peer review. Federal science leaders from multiple departments Footnote 5 analyzed input from the engagement and wrote this report. Throughout this process, it was evident that the organizing structures required for effective national science coordination and planning are limited, especially in light of the ambition and diversity of climate objectives.

The engagement conducted in 2021–2022 benefited from input to the broader Government of Canada engagement on the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan and Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy. In addition, the process involved engagement specifically for CS2050, including provincial and territorial engagement (Box 2.1); a targeted stakeholder survey; a Request for Information to academic organizations; and a series of seven expert science roundtables (Figure 2.1). The science roundtables discussed scientific “grand challenges” fundamental to success in mitigating GHGs and adapting to climate change. These discussions were framed by climate program leaders’ information needs, expressed through the engagement process.

A small workshop of Indigenous academic scholars complemented the science roundtable exercise, to garner insights from First Nations, Inuit, and Métis knowledge systems. This workshop further shaped the report, and, in particular, guided the development of Chapter 3, reflecting the importance of Indigenous science and capacity in weaving together Indigenous and Western science approaches.

The draft report was peer reviewed by 14 Canadian and international experts with multidisciplinary perspectives, grounded in their own specific areas of expertise. All had an appreciation of the Canadian science context through substantive engagement and/or collaboration with Canadian scientists.

Box 2.1. Provincial and territorial engagement: What we heard

Provincial and territorial governments are important users of climate change knowledge. They apply science results to reduce GHG emissions and implement adaptation that will be effective in their geographic and decision-making context. The information needs of all levels of government need to continue to inform climate change science, notably to:

- improve coordination of research across sectors and actors and improve mobilization of knowledge;

- create space and equity for Indigenous knowledge;

- improve emissions performance reporting, estimation methods, disclosure, and targets for accountability;

- improve monitoring; data collection; research on climate, risks, hazards, and opportunities; research to support vulnerability and risk assessments; and metrics, monitoring, and evaluation of interventions—in particular, in fisheries, forestry, agriculture, biodiversity, and ecosystems;

- improve prediction of climate extremes and extreme weather events;

- project climate impacts on water demand, supply, and management;

- develop hydrological, flood, and coastal hazard maps for planning, navigation, and emergency response;

- predict climate change on a local scale, and understand impacts for infrastructure, health, safety, culture, and heritage;

- develop projections, observations, data, and indicators to inform nature-based solutions and management of land, waters, wildlife, and ecosystems;

- co-develop information for mitigation, adaptation, and planning tools that municipalities, communities, local stakeholders, emergency management personnel, urban planners, engineers, and others can use to respond to climate change;

- develop integrated assessment tools, which factor climate change into policy as well as financial and economic planning; and

- understand and predict climate impacts on food security, including country foods and sustainable harvesting.

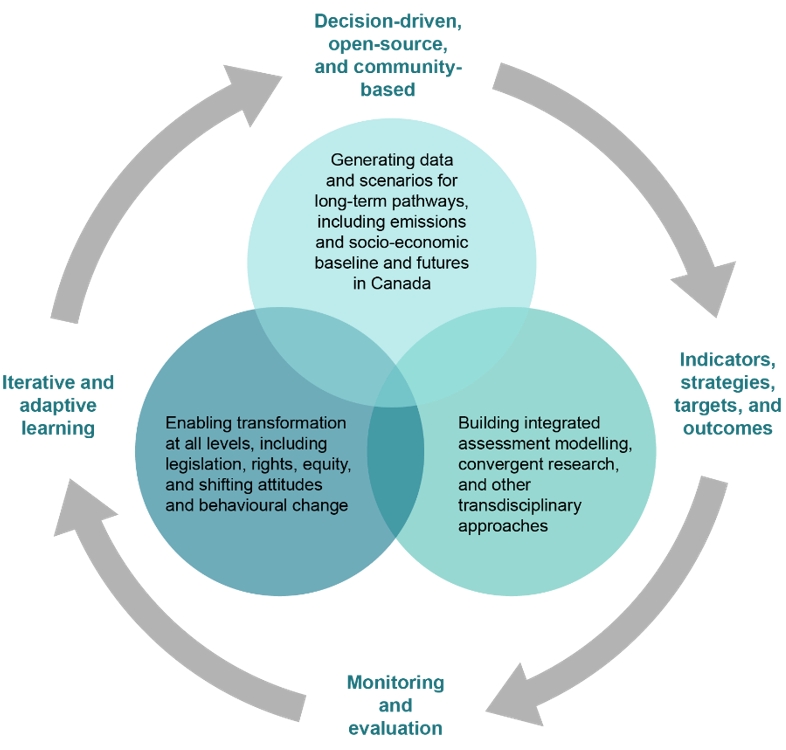

Figure 2.1. The development process for Climate Science 2050: National Priorities for Climate Change Science and Knowledge

A graphic that outlines the development process for the National Priorities for Climate Change Science and Knowledge report:

- Targetted stakeholder survey

- Academic request for information

- Provincial and territorial meetings

- National Indigenous organizations meeting

- The National Adaptation Strategy and Emission Reduction Plan tables

- Earth system climate change

- Healthy Canadians

Sustainable natural resources

Resilient aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, resilient, net-zero communities and built environment.

- Quantifying GHG emissions

- Communication and motivating action

- First Nation, Inuit, Métis knowledge systems insights.

- Canadian and international experts review, enhancing horizontal linkages across the report, and clarification of prioritization approach.

2.3 Transdisciplinary science and convergence research

The engagement and expert roundtables found that research frameworks must align with the increasing complexity of decision making for mitigation, adaptation, and sustainable development. This alignment requires advancing these frameworks toward transdisciplinary science (Box 2.2). Related to this alignment, several “nexus” topics, in which disciplines intersect, and “convergence” research topics (Box 2.2) emerged in discussions.

Box 2.2. Research paradigms for transformative science

The most challenging knowledge gaps require transdisciplinary science frameworks in order to include social, economic, natural, health, and Indigenous sciences and to integrate climate change, health, and economic well-being. The 2017 report Investing in Canada's Future: Strengthening the Foundations of Canadian Research notes that the multifaceted challenges facing society require science that goes beyond disciplines, bridging previously disconnected fields of knowledge and creating new disciplines.

Developing climate change knowledge requires participatory research paradigms, creating stronger relationships among disciplinary experts and between experts and decision makers. Furthermore, giving equal value and respect to Indigenous knowledge, alongside Western science, is itself a research paradigm that continues to develop.

In this science and knowledge report, the following terms are used (adapted from The Difference Between Multidisciplinary, Interdisciplinary, and Convergence Research | Research Development Office (ncsu.edu) and Research Types - Learn About Convergence Research | NSF - National Science Foundation). Transdisciplinary frameworks should enable equity and unity.