- IAS Questions

- IAS Polity Questions

- What Is The Meaning Of Judicial Review

What is the meaning of Judicial Review?

Judicial review is the power of the judiciary to examine the constitutionality of legislative enactments and executive orders of both the Central and State governments.

On examination, if they are found to be violative of the constitution (ultra vires) , they can be declared as illegal, unconstitutional and invalid (null and void) by the judiciary. Therefore, they cannot be enforced by the Government.

Further Reading :

- Judicial Review

- Supreme Court of India

- High Courts of India

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation, register with byju's & download free pdfs, register with byju's & watch live videos.

What is meant by Judicial Review?

Judicial review refers to the power of the judiciary to interpret the constitution and to declare any such law or order of the legislature and executive void if it finds them in conflict with the constitution of india. it acts as an important tool to ensure that all legislative, executive, administrative actions conform to the provisions of the nation’s constitution. the supreme court has been vested with the power of judicial review by various provisions of the constitution..

- Law of torts – Complete Reading Material

- Weekly Competition – Week 4 – September 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 1 October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 2 – October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 3 – October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 4 – October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 5 October 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 1 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 2 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 3 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 4 – November 2019

- Weekly Competition – Week 1 – December 2019

- Sign in / Join

Judicial review

This article is written by Abhinav Rana, from the University School of Law and Legal Studies, GGSIPU Dwarka and Nishka Kamath , a student of Nalanda Law College, University of Mumbai. This article explains the concept of judicial review along with its importance, scope, features, and functions, inter alia. It also discusses the grounds of judicial review in great detail. Moreover, the limitations of judicial review are discussed in great detail.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Law plays an important role in today’s society. People have given up on their rights and entered into a contract with the government in return of which the government gave them protection against the wrong. This is known as the Social Contract Theory given by Hobbes. In this phase of Rule of Law, the law without justice can become arbitrary and can be misused. So to keep check and balance on the power of each organ of government we have further adopted Judicial Review. Judicial review is the process by which the court declares any law which goes against the constitution as void. We have adopted this feature from the United States Constitution. But it took a lot of years to fix this feature in our constitution. Judiciary has played an important role in this regard. Judicial Review can be of Constitutional Amendments, Legislative actions and of Laws made by the legislature. In this research paper, we will discuss the history, growth, features and types of Judicial Review with Indian case laws.

In India, there are three organs of government namely Legislature, Executive and Judiciary. The Legislature performs the function of making the laws, the Executive executes/implements the laws and the Judiciary keeps a check on both the organs specified above and makes sure the laws being made and implemented are not ultra vires to the Constitution of India. To make these organs work in their specified limits our constitution has the feature of Separation of Power. Article 50 of the Indian Constitution talks about the separation of power.

This concept is not followed in the strict sense as compared to the USA from where it has been adopted. The concept of Judicial Review has been adopted from the American Constitution. The Judiciary has the power to set aside any law passed by the parliament if it intervenes in the Constitution of India. Any law passed by the legislature that contravenes the Constitution can be made null and void by the Judiciary. Under Article 13(2) of the Constitution of India, any law made by the parliament that abridges the right conferred to the people under Part 3 of the constitution is void-ab-initio. The power to interpret the Constitution of India to its full extent lies within the Judiciary. It is the protector of the Constitution of India. Power of Judicial Review is vested in many articles such as 13, 32,131-136, 143, 226, 145, 246, 251, 254 and 372.

Article 372(1) talks about Judicial review of the pre-constitutional laws that were in force before the commencement of the Constitution of India.

Article 13(2) further talks about any law made by the parliament after the commencement of the constitution shall be declared null and void by the Court.

The Supreme Court and High Court are said to be the guarantors of Fundamental given by the constitution. If any person’s Fundamental right is violated he/she can approach the court under Article 32 or Article 226 of the constitution.

Article 251 and 254 states that if there is any inconsistency between the union and state law, the law of union shall prevail and the state law shall be deemed void.

Why would you ask?

This is because of the principle of separation of powers. Separation of powers, also referred to as the system of checks and balances, is the doctrine of Constitutional law under which the three branches of the government, i.e., the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary, are kept separate. Thus, each branch has distinct powers and is usually not allowed to exercise the powers of the other branch. So, in a situation wherein the judiciary cannot substitute for the role of the executive or the legislature, it must not step into the shoes of the executive or legislature.

From the L. Chandra Kumar vs. Union of India (1997) case to the Indira Nehru Gandhi vs. Shri Raj Narain & Anr (1975) case, from the Golakhnath vs. State of Punjab (1967) to the Minerva Mills Ltd. vs. Union of India (1980) , the doctrine of judicial review has been an integral part of the Indian legal system, especially in cases where the law-making authorities have acted in contradiction to the supreme.

Judicial Review is in the news because of the order passed by the Supreme Court permitting a floor test in the Maharashtra Assembly. An issue was raised in this case as to “Whether the court can have the authority to review the decision of the Governor?”, to which senior advocate Dr. A.M. Singhvi contended that the court has the authority to exercise its power of judicial review to determine the Governor’s satisfaction while commanding a floor test.

Another instance of judicial review is the recent verdict passed by the Supreme Court of the United States in the case of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health, which overturned Roe v. Wade (1973) on abortion laws.

History of Judicial Review

The word judicial review at a very early instance came before the court in Dr Bonham Case. In this case, Dr Bohnam was forbidden to practice in London by the Royal college of physicians as he was not having a license for the same. This case is also known for the violation of Principals of Natural Justice as in this case there is Pecuniary bias. As Dr Bonham is fined for his without a license, practicing the fine would be distributed between the king and the college itself.

Afterwards, the word judicial review was summarized in Marbury V. Madison, 1803. In this case, the term period of President Adam belonging to the federalist party came to an end and Jefferson the anti-federalist came to power. On his last day, Adam appointed the members of the federal party as judges. But when Jefferson came to power he was against this. So he stopped Madison the secretary of state, from sending the appointment letter to the judges. Marbury, one of the judges, approached the Supreme Court and filed a writ of mandamus. Court refused to entertain the plea and first opposed the order of the legislature i.e Congress and thus the US Supreme court developed the doctrine of judicial review.

Why the judicial review is important

Judicial review is significant for the reasons mentioned as under:

- It averts the tyranny of executives.

- It safeguards the fundamental rights of the citizens.

- It is crucial for shielding the independence of the judiciary.

- It is an absolute necessity for maintaining the supremacy of the Constitution.

- It also helps in intercepting the misuse of power by the legislature and the executive .

- It aids in maintaining the equilibrium between the centre and the state, thus keeping a federal balance.

Scope of judicial review

Judicial review is not absolute, as some situations need to be met in order to demur against any law in the Supreme Court or the high courts, i.e., a law can be questioned only if:

- The law violates the fundamental rights that are enshrined by the Constitution.

- The law infringes upon the provisions listed in the Constitution.

- The enacted law goes beyond the capacity or power of the official(s) in charge that enacted it.

Features of Judicial Review

Power of judicial review can be exercised by both the supreme court and high courts: .

Under Article 226 a person can approach the high court for violation of any fundamental right or for any legal right. Also, under Article 32 a person can move to the Supreme Court for any violation of a fundamental right or for a question of law. But the final power to interpret the constitution lies with the apex court i.e Supreme Court. The Supreme Court is the highest court of the land and its decisions are binding all over the country.

Judicial Review of both state and central laws:

Laws made by centre and state both are the subject to the judicial review. All the laws, order, bye-laws, ordinance and constitutional amendments and all other notifications are subject to judicial review which are included in Article 13(3) of the constitution of India.

Judicial review is not automatically applied:

The concept of judicial review needs to be attracted and applied. The Supreme Court cannot itself apply for judicial review. It can be used only when a question of law or rule is challenged before the Hon’ble court.

Judicial review is not suo motu

The Supreme Court or the high court for that matter do not use their authority to conduct a judicial review by a suo motu action. However, such power is utilised when there is a question of law that comes before the courts or during the court proceedings when any such incident occurs or such conditions arise as to where the law is in question.

Principle of Procedure established by law:

Judicial Review is governed by the principle of “Procedure established by law” as given in Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. The law has to pass the test of constitutionality if it qualifies it can be made a law. On the contrary, the court can declare it null and void.

Functions of judicial review

Judicial review has two vital functions, namely:

- Of making the actions of the government legitimate, and

- To secure the Constitution from any undue encroachment by the government.

Judicial review can be done by whom?

Judicial review is interpreted as the doctrine under which executive and legislative actions are examined by the judiciary. In India, even though we have the principle of separation of powers for the different organs of the government, i.e., the executive, the legislative, and the judiciary, the judiciary is entrusted with the authority to review the actions of the other two organs.

In India, judicial review can be done by the High Courts as well as the Supreme Court. The powers of judicial review are delegated to the courts under Article 226 and Article 227 of the Constitution of India, as far as the High Courts are concerned, and in Article 32 and Article 136 with regard to the Supreme Court.

Judicial review of ordinances

Article 123 and 213 of the Indian Constitution gives the president and the governor of the state to pass an ordinance. An act of ordinance by the president or governor is within the same restrictions as which are placed on parliament which makes any law. This power is used by the president or governor in exceptional conditions only. The power should not be used mala fide. In a report published by the House of People, it was submitted that till October 2016 president has made 701 ordinances. Through the ordinance, it was held that Rs.500 and Rs. 1000 notes will cease to be liabilities from 31st December 2016.

In the case of AK Roy v. Union of India (1982) 1 SCC 271 it was held that the president’s power to pass an ordinance is not a subject of Judicial Review.

In the case of T. Venkata Reddy v. State of Andhra Pradesh (1985) 3 SCC 198 it was held that just like legislative power cannot be questioned, the ordinance made on the ground of motive or non-application of mind, or necessity cannot be questioned.

Judicial review of Money Bill

Article 110(3) of the constitution of India states that whenever a question arises for whether a bill is a money bill or not the decision of the speaker of Lok Sabha shall be final.

In the present scenario, a “money bill” is beyond the power of Judicial Review.

Article 212 of the constitution of India provides that the Courts cannot inquire proceedings of the Legislature on the ground of any alleged irregularity of procedure.

Article 255 of the constitution of India provides that the recommendation and previous sanction are matters of procedure only.

In the case of Mangalore Ganesh Beedi Works v. State of Mysore AIR 1963 SC 589 , it was held that the appellant was liable to sales tax under coinage act which was changed by coinage amendment act, 1955. So the contention was that as it enhanced the tax the bill should be passed as a money bill and as it was not passed as a money bill the tax should be held as invalid.

The Supreme Court held that the coinage amendment act 1955 substituted new coinage in place of old coinage and thus it was no tax.

By the way of obiter dicta, it was observed as if it would be a tax serving bill then also it was out of the proceedings of judicial review.

Grounds for Judicial Review

Constitutional amendment.

Judicial Review in this phase is done for all the constitutional amendments done by the authority. All those amendments which are in violation of Fundamental Rights are declared void and it is held to be unconstitutional. All the judicial review for the constitutional amendments can be traced in history. We have already seen in the above-mentioned case laws that the constitutional amendments were challenged and all those against the constitution are declared unconstitutional and held void. We can trace the marks of judicial review of the constitutional amendment in these cases: Shankari Prasad V. Union of India; Sajjan Singh V. State of Rajasthan; I.C. Golaknath V. State of Punjab; Kesavananda Bharti V. State of Kerala; I.R Coelho V. State of Tamil Nadu. All these cases are discussed in detail above in this paper.

Illegality

Lack of jurisdiction .

If an administrative authority has no right to perform a particular act, any purported action of such a right will be, as a matter of course, void and non-existent in the eyes of the law. Say for instance, if a minister has no power to revoke a licence, an order of revocation passed by him will be ultra vires and lack jurisdiction, as held in the case of R. vs. Minister of Transport (1934).

Further, in the case of Rafiq Khan vs. State of U.P. (1954) , it was held that the Panchayat Raj Act, 1947 did not give the Sub-Divisional Magistrate the authority to modify the order of conviction and sentence passed by a Panchayat Adalat. The order passed by the Panchayat Adalat could either be quashed altogether or have the jurisdiction of the Panchayat Adalat revoked. The Magistrate upheld the conviction of the accused in respect of one of the offences only and quashed the conviction in respect of the other offences. So, the Allahabad High Court subdued the conviction relating to the other offences via issuing a writ of certiorari.

A court may review an administrative action on the grounds that the authorities exercised jurisdiction that they did not have originally. This review may be done on the following grounds (inter alia):

- That the rules under which the administrative authority is composed and is exercising jurisdiction, are in itself unconstitutional.

- That the authority is not properly made in accordance with the rules and regulations or the laws.

- That the authority has mistakenly made a decision upon a jurisdictional fact, hence, might have assumed jurisdiction not belonging to the authority.

- That there were some crucial preliminary terms that were conditions precedent for the exercise of the jurisdiction but were disregarded.

- That the administration/officials were inept to assume jurisdiction in respect of the subject matter, areas and parties.

Excess of jurisdiction

It is mandatory that each and every administrative authority must exercise its power within the purview it is entrusted with, i.e., it must not exceed the boundaries and govern everything by staying confined to the four corners of the law. In case the power is exceeded, such an action will be deemed to be ultra vires and therefore void.

In one case [County Council vs. Attorney General (1902) AC 165] , a local authority had the power to operate tramways, but this authority began to operate a bus service, thus acting ultra vires and therefore void . Pertaining to the facts of the case, an injunction was applied for and duly granted by the Court.

Abuse of jurisdiction

This ground basically means that there should not be an act done in bad faith ( mala fide actions), but authority must always exercise its discretion for the reason it is allotted to them and must act in good faith ( bona fide actions).

In the case of Pratap Singh vs. State of Punjab, AIR 1964, SC 72 , a civil surgeon applied for a leave preparatory to his retirement and was granted such a leave, which was withdrawn later. He was placed under suspension and a departmental inquiry was ordered against him, which led to his dismissal from the post of civil surgeon. Here, a petition was filed asserting that such an act was performed at the behest of the Chief Minister, who wanted to settle a score with him since the time he had denied engaging in any illegal activities with the Minister. The Hon’ble Supreme Court, after scrutinising the facts and situations, quashed the order as it was mala fide in nature.

Abuse of jurisdiction may, inter alia, occur in some of the instances as under-

Malfeasance in office/improper purpose

Administrative power cannot be used for the purpose for which it is not allotted. In Attorney-General vs. Fulham Corporation , the administration was entitled under the law to set up warehouses for the non-commercial use of local occupants. The corporation then agreed to open a laundry on a commercial basis. The corporation was held to have acted ultra vires the law.

A mistake apparent on the face of the record

A mistake is proclaimed to be obvious when one can establish such an inference just by analysing the record without having to rely upon any other information.

In Syed Yakoob vs. K.S. Radhakrishnan (1963) , the Hon’ble Supreme Court stated that there was a seemingly obvious legal mistake on the face of the record where the outcome of the law recorded by an inferior tribunal is as follows:

- Is founded on a blatant misinterpretation of the appropriate statutory provisions,

- Is in ignorance of it,

- Is in disregard of it,

- Is particularly premised on rationales that are wrong in law.

Consideration of extraneous material

In exercising power, the person in authority or the authorities must pay heed to all the appropriate circumstances and dismiss insignificant circumstances.

In R vs. Somerset County Council, ex p Fewings (1955) , the local authority decided to put a ban on stag hunting on the property inhabited by the council and assigned it for recreational purposes. The Court of Appeal accepted that, in some situations, there could be a rightful ban on stag hunting. In this case, animal welfare and social considerations were relevant to take into account.

Mala fide management of power

When a decision taken by the decision-maker is taken dishonestly with a certain ulterior motive in his/her mind, such a person may be said to have acted in bad faith.

In R vs. Derbyshire County Council, ex p Times Supplemets (1991) , the local education authorities were under a task to call the attention of qualified persons to fill the vacancies of a certain post(s). The articles published in that newspaper (The Times) were read by a large number of potential applicants, but despite being aware of this fact, the Council decided to halt advertising such vacancies in the paper, and thus, the papers were sought for judicial review. The Derbyshire County Council reached a verdict that the educational council had taken such a decision not on the basis of educational grounds but motivated by a malicious desire for retaliation; and thus, the educational council has acted in bad faith, i.e., with mala fide intentions.

Fettering discretion

An authority may act ultra vires , i.e., beyond its capacity in times when a certain power to, say, adopt a policy, is exercised without effectively giving it a thorough thought about it, which means it does not actually exercise its discretion at all.

The same was held in the case of H Lavender & Sons vs. Minister of Housing & Local Government (1970) , wherein the local planning authority denied permission to Lavender to take extra sand and gravel from a high-grade agricultural land. Aggrieved by the decision, an appeal was made to the Minister of Housing and Local Government, but the appeal was dismissed as the Minister of Housing and Local Government was convinced to do so by the Minister of Agriculture, stating that such land must be conserved for the purpose of agriculture. This decision was set aside by the Court as the Minister, even after having the capacity to object, reached a decision based solely on the opinions of another Minister. Here, the Minister of Housing and Local Government did not have an open mind on Lavender’s appeal, and thus, fettered his discretion.

Failure to exercise jurisdiction

If any administrative authority is entrusted with power by law (even though discretionary), the person(s) in power or the authority must implement it in one way or the other. A failure to exercise discretion may arise, inter alia , in the following five circumstances, namely:

- Unauthorised delegation,

- Self-imposed fretters on discretion,

- Acting under the dictates of a superior,

- Non-application of mind,

- Power coupled with duty.

Irrationality (Wednesbury test)

The principle of irrationality as a ground for judicial review was brought into existence by the Associated Provincial Picture House Ltd. vs. Wednesbury Corporation (1948) .

A decision of the administrative authority shall be considered irrational in matters when-

- It does not have the authority of a law.

- It is not based on evidence.

- It is based on a consideration that is irrelevant and extraneous.

- The decision of the authorities is so whimsical, twisted, arbitrary, absurd and unfair that no rational person can reach a conclusion which has been reached by the authorities.

- It is so irrational that it may be done in bad faith or maliciously.

Procedural impropriety

Procedural impropriety needs a ‘fair procedure’ to be followed in every administrative action. The fair procedure would include

Rule against bias

It means no person should be a judge in their own cause ( nemo judex in causa sua ).

Rule of fair hearing

The rule of fair hearing states that no person should be condemned unheard ( audi alteram partum ).

Moreover, procedural impropriety also comprises the failure to observe regulations laid down in statutes along with the failure to observe the basic common rules of natural justice, as stated above.

In the classic case of Ridge vs. Baldwin (1963) , there is a revelation of judicial insistence on the fairness of the procedure notwithstanding the kind of authority deciding a question. The Chief Constable of Brington, Mr. Ridge, was dismissed from his duty following charges of conspiracy to pose a hindrance in the path of justice. In spite of the fact that the allegations imposed upon Ridge were proven false, the judge made comments which were critical of Ridge’s conduct. Thereupon, Ridge was dismissed from the force. He was not even invited to attend the meeting wherein the conclusion to remove him from work was reached, even though he was given the chance to appear before the Committee which inferred the previous decision. Ridge then made an appeal to the Home Secretary, which was dismissed. Ridge then sought a declaration on the grounds that the rules of natural justice were violated and that the Home Secretary went beyond his powers, i.e., ultra vires, while dismissing the appeal. This case law is of significant importance as it pinpoints the linkage between the right of an individual to be heard and the right to know the charges brought against the individual.

Proportionality

Proportionality means that the administrative authority must not be more drastic than it ought to be to seek the desired outcome. Proportionality is sometimes explained by the expression ‘taking a sledgehammer to crack a nut’. This doctrine endeavours to balance means with ends. Proportionality shares space with ‘reasonable restrictions’.

In Chairman, All India Railway Board vs. Shyam Kumar and Ors. (2010) , the Apex Court had defined the proportionality test as the “ least injurious means ” or the “ minimal impairment test ” for protecting the fundamental rights of citizens and guaranteeing a fair equilibrium between the individual rights and interests of the public.

While reviewing the action of an administration on the doctrine of proportionality, the court generally considers the following points:

- Whether the relative merits of varied objectives or interests are properly evaluated and balanced in a just manner?

- Whether the actions under consideration were, in the situations, extremely restrictive or inflicted a needless burden?

In Sardar Singh vs. Union of India (1991) , an Army Jawan who was serving in the Indian Army was granted leave. While proceeding to his hometown, he purchased 11 bottles of sealed rum and one bottle of brandy from the army canteen, even though he was authorised to carry only 4 bottles. In the Court Martial Proceedings initiated against him on those grounds, he was sentenced to undergo rigorous imprisonment for 3 months and was dismissed from his service. The Supreme Court withheld the award of punishment granted to the appellant. It further held that the action taken against the appellant was arbitrary and the penalty was severe.

The doctrine of proportionality is an important principle as it authorizes the courts to check the possible abuse of discretionary power by the executive. In this doctrine, the court has to ascertain whether the action taken was seriously needed as well as whether it was within the purview of courses of action that could otherwise be interpreted.

Types of judicial review

As famously classified by Justice Syed Shah Mohamed Quadri, there are three major categories of judicial review. They are as follows:

Reviews of legislative actions

This type of judicial review insinuates that the laws enacted by the legislature are in accordance with the laws laid out in the Constitution. This has been a topic of discussion in numerous Supreme Court cases, of which the following are the most noteworthy:

Shankari Prasad case

In Shankari Prasad vs. Union of India (1951) , a challenge was made to the First Amendment Act of 1951 on the grounds that the ‘Right to Property’ was restricted. The Supreme Court denied such an argument and stated that this could not be executed since the fundamental rights under Article 13 cannot be curtailed.

Sajjan Singh case

In Sajjan Singh vs. State of Rajasthan (1965) , the existence of the Constitution under the 17th Amendment Act of 1964 was in question. The Court eradicated the position in the Shankar Prasad case (discussed above) and held that the constitutional amendments made under Article 368 are not within the ambit of judicial review by the courts.

Golakh Nath case

In I. C. Golaknath & Ors vs. State Of Punjab & Anrs. (1967) , there was a challenge made to three constitutional amendments, namely- the first (1951), fourth (1955) and seventeenth (1964). The Hon’ble Supreme Court asserted that Parliament has no authority under Article 368 to change the Constitution or to take away or restrict fundamental rights.

Keshavananda Bharati case

In Keshavananda Bharti vs. State of Kerala (1973) , a challenge was made to the 24th (1971) and 25th (1971) Constitutional Amendments. A 13-bench judge was formed to attend the case, and with a 7 : 6 ratio, the Court deduced that:

- Article 368 of the Constitution provides the President with the power to bring about changes in the Constitution.

- Ordinary laws and constitutional amendments are not the same thing.

- The core structure of the Constitution cannot be toppled with or amended by the Parliament.

Indira Gandhi case

In Indira Nehru Gandhi vs. Shri Raj Narain & Anr (1975) , the then Prime Minister of India- Indira Gandhi was held guilty of electoral malpractices by the Supreme Court.

Minerva Mills case

In Minerva Mills Ltd. vs. Union of India (1980) , clauses (4) and (5) of Article 368, which were inserted by the 42nd Amendment (1976), were struck down by the Apex Court on the grounds that these clauses destroyed the basic structure of the Constitution.

Review of administrative actions

This is yet another mode to achieve constitutional discipline over the administrative agencies while exercising their authority. A point must be noted that the judicial review of administrative actions of the Union of India as well as the state governments and their officials comes under the ambit of the meaning of state.

Review of judicial decisions

This type of review is implemented to rectify or revamp amendments in previous findings or pronouncements by the judiciary itself. This sort of review was evident in the following cases, inter alia :

Golaknath case and Minerva Mills case

These cases are discussed in detail above.

Bank Nationalisation case

In Rustom Cavasjee Cooper vs. Union of India (1970) , popularly known as the Bank Nationalisation Case, the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution assures the right to compensation, i.e., to an identical sum of money for property that was acquired by compulsion.

Allied principles of judicial review

Principle of comity.

As per the principle of comity, all the state authorities should support the functions of each other that are important to enable authorities to perform their duties in a responsible way as per the rules and values of the Constitution.

Principle of subsidiarity

By virtue of the principle of subsidiarity, public functions and powers should be applied at a level where they can be undertaken properly and in a responsible way. For instance, political questions can be better determined by the political authorities, policy matters can be better established by the legislative branch, whereas judicial matters can be regulated in a finer way by the judicial branch.

Principle of contextuality

In the principle of contextuality, the law needs to take into consideration the context in which it is to be applied. Such action is performed for verifying that the role of law attains its duty as an indicator of social engineering in society.

Principle of proportionality

On account of this principle, the courts exert their power of judicial review to determine if there is a harmony between the limitation on the right and the lawful end sought to be accomplished. As a part of this principle, there are three measures applied by the court, they are-

Examining the means

The courts scrutinise the means adopted by the administrative authority. Thus, it inspects whether the ways adopted by the administrative authorities are within the purview of their power, the least onerous, and reasonably connected to the end.

Examining the end

Following the above procedure, the court then delves into the ends, in terms of whether they are legalised, and within the capacity of the officials.

Examining the balance between means and end

Finally, the courts consider whether there is an equilibrium between the means and the end.

Constitutional provisions for judicial review

Procedure for judicial review in india .

In India, judicial review is headed by the principle of ‘Procedure established by law’ as stated under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. If the law passes the test of constitutionality, it can be said to be legislation. Conversely, the court has the power to declare the law null and void.

Limitations of judicial review

There are certain limitations on the exercise of power when it comes to judicial review by the high courts and the Apex Court. In fact, when the judiciary oversteps its boundary and intrudes into matters that are authorised by the executive, it is termed judicial activism; whereas, when power is exploited further, it can lead to judicial overreach. Below are some of the limitations of judicial review:

General limitations

Restricts the functioning of the government.

The scope of judicial review is limited, both in terms of availability and function. Here, the role of the court is to perform a review on the method through which an outcome was deduced so as to determine whether such a finding is defective and must be rescinded, instead of re-making the ruling in question or investigating the merits of the decision deduced. In short, it is only allowable to the degree of determining whether the method of reaching the inference was properly adhered to or not. It is not a decision in itself.

Violation of limits set by the Constitution

When it overrides any previously established law, it violates the limits of power put forth by the Constitution. Here, the legislative powers that are exercised by the Constitution are said to be erred.

Concept of separation of power not observed

The concept of separation of functions is followed rather than that of separation of power. Additionally, the concept of separation of powers is not strictly adhered to. Although, a system of checks and balances has been introduced, thus entrusting the judiciary with the power to overturn any unconstitutional laws passed by the legislature.

Sets a precedent

The judicial opinions of a judge once taken in a particular case would serve as the basis for deciding another case, thus acting as a precedent.

Selfish motives and influences

Judicial review can prove to be detrimental to the local public as there are chances of the judgment being influenced by personal or selfish motives. This can lead to causing damage to the public at large.

Frequent interference by the court has a negative effect on the local public

Repeated court interventions can undermine the confidence of people in the integrity, quality, and efficiency of the government.

Lack of the capability to overrule administrative decisions

The court lacks the ability to repudiate the decisions taken by the administrative authorities. If a review of an administrative ruling is authorized, the decision of the court would be substituted, thus regarded to be a shortcoming due to inadequate knowledge.

Judicial activism and judicial self-restraint

There is quite a discourse on whether there should be a line drawn between judicial activism and judicial self-restraint.

Doctrine of Strict Necessity

The doctrine of strict necessity states that the court must rule on constitutional matters only if strict necessity requires it to do so. Thus, constitutional questions will not be determined in a wider manner than required.

Constitutional limits and limitations on judicial review

The Hon’ble Supreme Court enjoys a privileged position that empowers it with the authority to review the legislative enactments legislated by Parliament and the state legislature. This power empowers the court with a powerful means for judicial review. There are several provisions in the Constitution of India (as discussed above) that provide for judicial review. The court has the duty to determine the unconstitutionality (if any) of the law enacted by the legislature and to rightly comprehend the provisions and objectives of the Constitution.

In L. Chandra Kumar vs. Union Of India And Others (1997) , a question was raised as to ‘Whether the exclusion of the jurisdiction of the high court through Article 323 A (2)(d) and 323 (b) was in opposition to the doctrine of judicial review, which basically was a primary feature of the Indian Constitution?’ The Court, while arriving at a decision, took several references like the Administrative Tribunals Act, along with the Sampat Kumar Judgement and the debates of the Constitutional Assembly. The Court, after carefully scrutinizing each and every event, reckoned that judicial review is indeed a basic feature of the Constitution of India. Moreover, the Court also considered the opinions of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, who was the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constitution, on Article 25 (present Article 32), where he asserted that this Article is the very soul of the Indian Constitution. Further, the seven-judge Constitutional Bench also stated that “ the power of judicial review over legislative action vested in the High Courts under Article 226 and in the Supreme Court under Article 32 of the Constitution is an integral and essential feature of the Constitution, constituting part of its basic structure. ”

Implied limitations on the exercise of the power of judicial review

Locus standi.

Considering the principle of ‘ locus standi ’, a petition under Article 32 of the Constitution can only be filed by the individual(s) whose fundamental or legal rights have been violated, however, relaxation has been given by the courts via the formation of the concept of Public Interest Litigation (PIL). Thus, if a decision which is contemplated to be patently bad is challenged, the courts ought not to protest in evaluating the act on the grounds of locus standi .

Res Judicata

As per the principle of res judicata , there should be finality to binding verdicts of the court of competent jurisdiction and no party should be irked with the same litigation a second time. Thus, if a petition has been filed in a court that gets dismissed, the same petition cannot be filed in the same court on the exact foundation.

Unreasonable delay

The remedies granted under Articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution must be sought within a reasonable time unless the reason for the delay is persuasive and acceptable. Due to this limitation, the court will decline to exercise its jurisdiction in matters of parties who have come to seek justice after a reasonable delay and are guilty of laches.

Regardless, a point must be noted that there is no fixed period for laches, thus, every case will be decided based on the facts and contentions of the party(ies) to the case.

Exhaustion of alternative remedies

This limitation is not strictly imposed, however, as stated in the case of Y. Theclamma vs. UOI (1987) , the Supreme Court dictates that all the possible remedies must be sought by the petitioners before resorting to Article 32. The reason behind such a limitation is that the writ jurisdiction is not meant to dodge statutory procedures but only be used as an extraordinary remedy in situations where all other remedies are ill-suited.

Exclusion of judicial review

Meaning of exclusion of judicial review .

Exclusion of judicial review refers to those circumstances wherein the powers of the high courts and the Supreme Court to exercise writs are excluded. It can be said to be the restrictions/limitations imposed on the power of the courts to review the actions of a public body (including the executive and the legislature).

How is the exclusion of judicial review carried out?

The exclusion of judicial review is carried out by Article 74(2) of the Constitution of India, and then there is the ouster clause. The ouster clause has provisions that do not provide for appeals or revision. It makes the judgement or act of the authority to be final and binding. This clause also avers that once an order is passed, it may not be called upon for questioning in any court. Thus, it may exclude the jurisdiction of the court entirely.

Indian scenario on the exclusion of judicial review

The position of India on matters of judicial exclusion is quite similar to that of the United States. There is a charter of fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution in written format, and such rights can be reduced by the theory of administrative finality.

In India, all three organs of the state, i.e., the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary, obtain power from the written Constitution, and the organs must act within the limitations of such powers.

Constitution of India (COI) and the exclusion of judicial review

The judiciary has been allotted the task of ascertaining what powers are conferred on which branch of the government, thus being the interpreter of the Constitution. It is also presented with the power of judicial review under Articles 32 and 226, which is not only an important part of the Constitution but also its basic structure, as held in the case of SP Sampath Kumar vs. UOI (1987) by Justice Bhagwati, relying on the Minerva Mills case.

A note must be taken that despite the written Constitution, the fundamental rights ( Articles 12 to 35 ) and the constitutional remedies (Articles 32, 226, 227, and 136), the legislature still has the propensity to exclude judicial review in certain fields, namely:

- Express or implied exclusion,

- Total or partial exclusion,

- Conditional or qualified exclusion, or

- Unconditional or unqualified exclusion.

Provisions of the Constitution excluding judicial review

Article 53 .

Under Article 53 of the Constitution, the executive power of the Union is vested in the President.

Under Article 72 of the Constitution, the President shall have the power to grant pardons or suspend punishments and such a power cannot be truncated by any court.

Article 74 (1) and (2)

Under Articles 74(1) and (2) , there shall be a Council of Ministers at the head to help and educate the President, and the President shall work in consonance with such advice. However, the question of whether any and if so what, advice was given to the President by the Ministers shall not be investigated by any court.

Under Article 77 , the conduct of any business of the government shall not be a subject of suspicion.

Article 77 and 78

Under Articles 77 and 78 , there is a prohibition of judicial review to give ample freedom for the exercise of executive power.

Under Article 80 , the composition of the Council of States is exclusively left to the discretion of the President.

Article 103

Under Article 103 , on the grounds of Article 102 , the decision on questions as to disqualifications of members shall be vested in the President and such rulings shall be absolute.

Article 161

Under Article 161, the power of the Governor to grant pardons, suspend punishments, etc., cannot be truncated by any court.

Article 361

Under Article 361 , the President, Governors, and Rajpramukhs are excused from legal proceedings in a court of law with respect to the acts performed during the term of office.

Further, the exercise of the power of the President or the Governor cannot be subjected to judicial review based on merits, as held in the case of Swaran Singh vs. State of UP (1998).

Moreover, the courts cannot issue any guidelines in matters of such interests as held in the case of Maru Ram vs. UOI (1981).

Besides, the court cannot ask the President or the Governor to list reasons for backing the order passed by them as stated in the case of State of Punjab vs. Joginder Singh (1990) .

Exceptions for the exclusion of judicial review

The power of judicial review will be exercised in cases where the exercise of power is-

- Discriminatory,

- Mala fide, or

- When material facts were not brought to the notice of the President or the Governor.

In such cases, the action can be set aside and instructions can be issued to pass a new ruling in compliance with the law.

Ouster clauses

An ouster clause can be defined as an effort of the legislature to preclude the actions or rulings of any public authority from being questioned before the courts. Such clauses are formed in order to signal to the decision-makers that they may perform without any fear of intrusion from the court. There are two main types of ouster clauses, which are discussed below.

Types of ouster clause

Partial ouster or time limit clause.

Unlike the total ouster clause, which eliminates judicial review completely, a partial ouster or time limit clause provides a certain time period, after which no remedy shall be attained. These types of clauses are generally quite efficacious unless the public authority has acted with mala fide intent.

The partial exclusion of the judiciary was given consent in the case of Sampath Kumar vs. UOI. In this case, it was held that the decision of the administrative tribunal can be excluded from judicial review by the high court if the tribunal constitutes a ‘judicial element’. In order to completely preclude judicial review, an appeal procedure has to be established, but this is not very much appreciated in the Indian continent as it is believed that judicial review cannot be barred completely even if there were other remedies in cases where the tribunals used powers that were ultra vires.

Total ouster or finality clause

Total or finality clause means the decision by any agency ‘shall be final’. In simple words, it means the decision of the judge or tribunal is final and cannot be challenged by any court.

In the case of Shri Kihota Hollohon vs. Mr. Zachilhu and Others (1992) , a reference was made to a statement by Professor Wade that said “ Finality is a good thing, but justice is better ”. He also made an observation that many statutes render that some decisions are “ final ” and that these provisions act as a bar to any appeal, but such provisions do not hamper the operation of judicial review as the courts forbid them to act in such a way. Thus, the normal effect of the finality clause is to not give rise to any further appeals.

Further, in the case of Union of India and Anr. vs. Tulsiram Patel and Ors. (1985) , the Hon’ble Supreme Court was dealing with Article 311(3) of the Constitution, which attaches finality to the order of the disciplinary authority regarding whether it was reasonably practicable to hold an inquiry or not. The Court made an observation that the ‘finality’ clause did not preclude jurisdiction, be that as it may, but it suggested that the jurisdiction is bounded by certain grades.

The legal issue associated with the ouster clause

The main legal issue with the ouster clause is ‘whether it is truly feasible to eliminate the jurisdiction of the courts by the use of carefully drafted laws?’

A professor in Singapore by the name of Thio Li-ann has observed that “ courts generally loathe ouster clauses as these contradict the rule of law whereby judges finally declare the legal limits of power and also as the individual’s ultimate recourse to the law is denied. Hence, courts try to construe these strictly to minimise their impact. In so doing, they may be going against the grain of parliamentary will .”

A note must be taken that the ouster clause does not effectively debar judicial review of errors of law that have an impact on the jurisdiction of the authority in the process of making decisions. In the case of Regina vs. Medical Appeal Tribunal ex parte Gilmore; Re Gilmore’s Application: CA 25 Feb (1957) , Lord Alfred Denning stated that he finds it very “ well settled that the remedy by certiorari is never to be taken away by any statute except by the most clear and explicit words. The word ‘final’ is not enough.” And in Anisminic Ltd. vs. Foreign Compensation Commission (1968) , it was stated that this type of clause is for making the “ decision final on the facts, but not final on the law. Notwithstanding that the decision is by a statute made ‘final,’ certiorari can still issue for excess of jurisdiction or for error of law on the face of the record. ”

Thus, it can be deduced from the above cases that judicial review can not be eliminated by the courts in cases where there was an excess of jurisdiction or if there was an error of law in attaining an inference/judgement.

Judicial self-restraint

What is judicial restraint or judicial self-restraint .

Judicial restraint, also known as judicial self-restraint, is a theory of judicial interpretation that encourages judges to limit the exercise of the power vested in them. In simple words, the courts must render the law and not intrude in the policy-making process. The judges, too, should make an attempt to decide cases on the grounds of-

- The primary intent of the writers of the Constitution.

- The precedents, i.e., the past verdicts in previous cases.

- Moreover, the policy-making process must be left to others and should not be intervened in by the court.

In judicial restraint, the courts ‘restrain’ themselves from implementing new policies at their discretion.

The necessity of judicial restraint

Judicial restraint is necessary due to the following reasons:

- Judicial restraint aids in maintaining a balance between the three branches of the government, that is-

- The executive,

- The judiciary, and

- The legislature.

- The laws established by the government in the legislature are sustained.

- It shows earnest respect for the separation of problems from the government.

- It allows the legislature and the executive to comply with their obligations and job responsibilities thereof without reaching into their area of work.

- By leaving the process of policy-making to the policymakers, judicial restraint marks respect for the democratic form of government.

Landmark judgments on judicial restraint

State of rajasthan vs. union of india (1977).

In this case , the Court rejected a petition on the basis that it had the involvement of a ‘political question’. Being involved would mean moving into the political domain, and thus, the Court would not go into the matter.

S. R. Bommai vs. Union of India (1994)

In this famous case , the judges opined that in specific circumstances, political elements are predominant and there is no possibility of judicial review. The exercise of power, as stated under Article 356 of the Constitution, was a political issue and therefore there was no need for judicial intervention. The Court asserted that it is challenging to develop norms that are judicially manageable for analysing political decisions, and if the courts intervene, then they would be entering into the political domain and thus impugning political wisdom, which they must stay away from at all costs.

Almitra H. Patel vs. Union of India (2000)

In this case , the Court, on the issue of whether directions should be issued to the Municipal Corporation pertaining to making Delhi neat and clean, expressed that it was not for the Supreme Court to instruct them as to how to execute their most basic tasks. Thus, the Court can only instruct the municipal authorities to perform functions prescribed under law.

Current scenario of judicial review in India

Not long ago, the Supreme Court of India denied agreeing to the Central Vista project as a unique case needing ‘heightened’ judicial review. The Court stated that the government had the discretion to construct policies and have an error in it thereof as long as the Constitutional guidelines are being adhered to.

With the elimination of the locus standi principle, suo moto cases and Public Interest Litigations (PILs) have granted the judiciary the power to meddle in matters relating to the well-being of the general public even when the offended party did not raise any objections.

The way forward

Judges, especially in a country like India, have potent judicial powers in their hands. Most importantly, they have the power of judicial review. This is why it is crucial for the judiciary to not only avert abuse and misuse of power but also to cease exploitation and unjust activities.

Furthermore, there should be a clear deliberation on judicial activism and the proper use of PILs, in order to make sure that such tools are not used for political motives. The judiciary needs to scrutinise why a particular writ or PIL was filed in cases where a constitutional remedy is sought. The CAA, or the abrogation of Article 370, was opposed in the Hon’ble Supreme Court for gaining a political agenda. This is why when such cases reach the judiciary for review, they should be carefully scrutinised as to whether there is an ulterior motive or if it is against the betterment of the common people.

Moreover, many a time, NGOs are puppets of political parties or of those who are backed up by international countries or communities wishing nothing but ill for the sovereignty of the country, thus, it is high time the courts look through the transparent glass doors and carefully examine the motives of parties seeking such remedies.

Another polemic issue on the interpretation of the Constitution occurred when the constitutional power to appoint the Chief Justice of India (CJI) was taken away from the President by the Hon’ble Supreme Court. Such acts must undergo careful judicial scrutiny.

Here in India we have adopted the concept of Separation of power so we cannot assume the power of judicial review in full extended form. If the courts presume full and arbitrary power of judicial review it will lead to the poor performance of work by all the organs of government. So to keep all the functions work properly each has to work in its provided sphere. In India, we have the concept of judicial review embedded in the basic structure of the constitution. It helps the courts to keep a check and balance upon the other two organs of government so that they don’t misuse their power and work in accordance with the constitution.

The function of judicial review is one of the most powerful systems in the Indian Constitution. This doctrine absolutely has its roots in India and has an explicit sanction in the Indian Constitution.

The process of judicial review functions as a guardian of the Constitution and also safeguards the fundamental rights enshrined under the Constitution. Moreover, it also distributes power between the union and the states and clearly defines the functions of every organ functioning in the nation. W e have developed the concept of judicial review and it has become the part of basic structure in case of Minerva Mills V. Union of India. So, at last, it is correct to say that judicial review has grown to safeguard the individual right, to stop the use of arbitrary power and to prevent the miscarriage of justice.

Some FAQs on judicial review

What is judicial review a decision about.

Judicial review is a sort of court proceeding where the legitimacy of a ruling/verdict or act performed by a public authority is examined by a judge. This is to say, it is a challenge to the manner in which a ruling has occurred rather than the rights and wrongs of the inference reached.

What is the difference between judicial review and appeal?

- Judicial review is not statutory, whereas appeals are statutory.

- Only public bodies are subjected to judicial reviews, whereas appeals are applicable to both- private and public bodies.

- In judicial review, the court scrutinises only the manner in which a decision was taken, whereas, in an appeal, the court examines the rulings made by inferior courts to determine whether such a decision was correct or not.

What are some possible remedies available in judicial review?

The remedy in a judicial review is discretional. So, even if a public authority has operated in an illegal manner, the court may decline to issue any remedy if such an act was committed in the interest of the public. There are a few possible remedies, inter alia in judicial review proceedings, namely-

Quashing Orders

It reverses any judgement or rolling or action under review, making it lawfully void.

Mandatory Orders

It coerces a public authority to perform a particular act, for instance, to revive a decision within a specific time period.

Prohibiting Orders

It prohibits or restricts a public authority from making a decision.

Declarations

It is a declaration of what the law is, in cases where there is a clash.

Such orders are those that order a public authority to pay for damages. Nonetheless, such a remedy is only functional when some other legal remedy is also sought.

Can a judicial review decision be appealed or curtailed?

The Supreme Court in the case of B. C. Chaturvedi vs. Union of India and ors. (1995) held that “Judicial review is not an appeal from a decision but a review of the manner in which the decision is made.”

Thus, it is implied to ensure that the person receives fair and just treatment and not for ensuring that the ruling attained by the authorities is appropriate in the eyes of the Court.

Can a judicial review be overruled or rescinded?

There was a clause added by the 42nd Amendment of 1976, inter alia , to Article 368, placing a constitutional amendment beyond judicial review. Further, in the Kesavananda Bharati case, the Court reached the hypothesis that judicial review is the ‘basic feature’ of the Constitution and cannot be eliminated by any authority.

- SCC ONLINE

- INDIAN KANOON

- LEGAL SERVICES INDIA

- THE HINDU ARTICLES

- BAR AND BENCH BLOG

Students of Lawsikho courses regularly produce writing assignments and work on practical exercises as a part of their coursework and develop themselves in real-life practical skills.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals, and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join:

https://t.me/lawyerscommunity

Follow us on Instagram and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more amazing legal content.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Shamsher singh vs. state of punjab (1974), krishna kumar singh vs. state of bihar (2017), enforcement of arbitral awards, leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How to Pass the Advocate-on-Record (AoR) Exam and Establish Your Supreme Court Practice

Register now

Thank you for registering with us, you made the right choice.

Congratulations! You have successfully registered for the webinar. See you there.

- Class 6 Maths

- Class 6 Science

- Class 6 Social Science

- Class 6 English

- Class 7 Maths

- Class 7 Science

- Class 7 Social Science

- Class 7 English

- Class 8 Maths

- Class 8 Science

- Class 8 Social Science

- Class 8 English

- Class 9 Maths

- Class 9 Science

- Class 9 Social Science

- Class 9 English

- Class 10 Maths

- Class 10 Science

- Class 10 Social Science

- Class 10 English

- Class 11 Maths

- Class 11 Computer Science (Python)

- Class 11 English

- Class 12 Maths

- Class 12 English

- Class 12 Economics

- Class 12 Accountancy

- Class 12 Physics

- Class 12 Chemistry

- Class 12 Biology

- Class 12 Computer Science (Python)

- Class 12 Physical Education

- GST and Accounting Course

- Excel Course

- Tally Course

- Finance and CMA Data Course

- Payroll Course

Interesting

- Learn English

- Learn Excel

- Learn Tally

- Learn GST (Goods and Services Tax)

- Learn Accounting and Finance

- GST Tax Invoice Format

- Accounts Tax Practical

- Tally Ledger List

- GSTR 2A - JSON to Excel

Are you in school ? Do you love Teachoo?

We would love to talk to you! Please fill this form so that we can contact you

- MCQ Questions (1 Mark)

- Assertion Reasoning

- Picture Based Questions

- True or False

- Match the Following

- Fill in the blanks

- NCERT Questions

- Past Year Questions - 2 Marks

- Past Year Questions - 3 Marks

- Past Year Questions - 5 Marks

- Case Based Questions

The Judiciary - Concepts - Chapter 4 Class 9 Political Science - Working of Institutions - Political Science

Last updated at April 16, 2024 by Teachoo

The Judiciary

- All the courts at different levels in a country put together are called the judiciary .

- The Indian judiciary consists of a Supreme Court for the entire nation, High Courts in the states, and District Courts-The courts at the local level.

- India has an integrated judiciary which means the Supreme Court controls the judicial administration in the country. Its decisions are binding on all other courts of the country.

- It can take up any dispute-

- Between citizens of the country

- Between citizens and government

- Between two or more state governments

- Between g overnments at the union and state level

- Independence of the judiciary means that it is not under the control of the legislature or the executive. The judges do not act on the direction of the government or according to the wishes of the party in power.

- The judges of the Supreme Court and the High Court s are appointed by the President on the advice of the Prime Minister and in consultation with the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

- Once a person is appointed as judge of the Supreme Court or the High Court it is n early impossible to remove him or her from that position.

- A judge can be removed only by an impeachment motion passed separately by two-thirds of members of the two Houses of Parliament.

- The judiciary in India is one of the most powerful in the world.

- The Supreme Court and the High Courts have the power to interpret the Constitution of the country.

- They can determine the Constitutional validity of any legislation or action of the executive in the country when it is challenged before them. This is known as the judicial review .

- The Supreme Court of India has also ruled that the core or basic principles of the Constitution cannot be changed by the Parliament.

- The powers and the independence of the Indian judiciary allow it to act as the guardian of Fundamental Rights. Anyone can approach the courts if the public interest is hurt by the actions of the government. This is called public interest litigation .

Davneet Singh

Davneet Singh has done his B.Tech from Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. He has been teaching from the past 14 years. He provides courses for Maths, Science, Social Science, Physics, Chemistry, Computer Science at Teachoo.

Hi, it looks like you're using AdBlock :(

Please login to view more pages. it's free :), solve all your doubts with teachoo black.

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Judicial Review

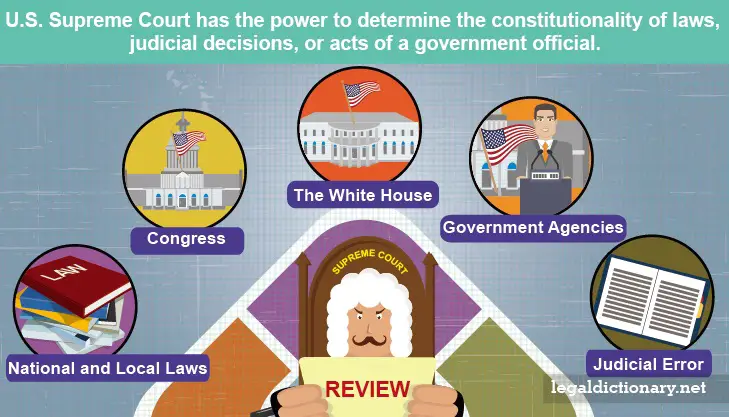

In the United States, the courts have the ability to scrutinize statutes, administrative regulations, and judicial decisions to determine whether they violate provisions of existing laws, or whether they violate the individual State or United States Constitution . A court having judicial review power, such as the United States Supreme Court, may choose to quash or invalidate statutes, laws, and decisions that conflict with a higher authority. Judicial review is a part of the checks and balances system in which the judiciary branch of the government supervises the legislative and executive branches of the government. To explore this concept, consider the following judicial review definition.

Definition of Judicial Review

- Noun. The power of the U.S. Supreme Court to determine the constitutionality of laws, judicial decisions, or acts of a government official.

Origin: Early 1800s U.S. Supreme Court

What is Judicial Review

While the authors of the U.S. Constitution were unsure whether the federal courts should have the power to review and overturn executive and congressional acts, the Supreme Court itself established its power of judicial review in the early 1800s with the case of Marbury v. Madison (5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 2L Ed. 60). The case arose out of the political wrangling that occurred in the weeks before President John Adams left office for Thomas Jefferson.

The new President and Congress overturned the many judiciary appointments Adams had made at the end of his term, and overturned the Congressional act that had increased the number of Presidential judicial appointments. For the first time in the history of the new republic , the Supreme Court ruled that an act of Congress was unconstitutional. By asserting that it is emphatically the judicial branch ’s province to state and clarify what the law actually is, the court assured its position and power over judicial review.

Topics Subject to Judicial Review

The judicial review process exists to help ensure no law enacted, or action taken, by the other branches of government , or by lower courts, contradicts the U.S. Constitution. In this, the U.S. Supreme Court is the “supreme law of the land.” Individual State Supreme Courts have the power of judicial review over state laws and actions, charged with making rulings consistent with their state constitutions. Topics that may be brought before the Supreme Court may include:

- Executive actions or orders made by the President

- Regulations issued by a government agency

- Legislative actions or laws made by Congress

- State and local laws

- Judicial error

Judicial Review Example Cases

Throughout the years, the Supreme Court has made many important decisions on issues of civil rights , rights of persons accused of crimes, censorship , freedom of religion, and other basic human rights. Below are some notable examples.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

The history of modern day Miranda rights begins in 1963, when Ernesto Miranda was arrested for, and interrogated about, the rape of an 18-year-old woman in Phoenix, Arizona. During the lengthy interrogation, Miranda, who had never requested a lawyer , confessed and was later convicted of rape and sent to prison . Later, an attorney appealed the case, requesting judicial review by the Supreme Court, claiming that Ernesto Miranda’s rights had been violated, as he never knew he didn’t have to speak at all with the police.

The Supreme Court, in 1966, overturned Miranda’s conviction, and the court ruled that all suspects must be informed of their right to an attorney, as well as their right to say nothing, before questioning by law enforcement. The ruling declared that any statement, confession, or evidence obtained prior to informing the person of their rights would not be admissible in court. While Miranda was retried and ultimately convicted again, this landmark Supreme Court ruling resulted in the commonly heard “Miranda Rights” read to suspects by police everywhere in the country.

Weeks v. United States (1914)

Federal agents, suspecting Fremont Weeks was distributing illegal lottery chances through the U.S. mail system, entered and searched his home, taking some of his personal papers with them. The agents later returned to Weeks’ house to collect more evidence, taking with them letters and envelopes from his drawers. Although the agents had no search warrant , seized items were used to convict Weeks of operating an illegal gambling ring.

The matter was brought to judicial review before the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether Weeks’ Fourth Amendment right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure , as well as his Fifth Amendment right to not testify against himself, had been violated. The Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled that the agents had unlawfully searched for, seized, and kept Weeks’ letters. This landmark ruling led to the “ Exclusionary Rule ,” which prohibits the use of evidence obtained in an illegal search in trial .

Plessey v. Ferguson (1869)

Having been arrested and convicted for violating the law requiring “Blacks” to ride in separate train cars, Homer Plessey appealed to the Supreme Court, stating the so called “Jim Crow” laws violated his 14th Amendment right to receive “equal protection under the law.” During the judicial review, the state argued that Plessey and other Blacks were receiving equal treatment, but separately. The Court upheld Plessey’s conviction, and ruled that the 14th Amendment guarantees the right to “equal facilities,” not the “same facilities.” In this ruling, the Supreme Court created the principle of “ separate but equal .”

United States v. Nixon (“Watergate”) (1974)

During the 1972 election campaign between Republican President Richard Nixon and Democratic Senator George McGovern, the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate building was burglarized. Special federal prosecutor Archibald Cox was assigned to investigate the matter, but Nixon had him fired before he could complete the investigation. The new prosecutor obtained a subpoena ordering Nixon to release certain documents and tape recordings that almost certainly contained evidence against the President.

Nixon, asserting an “absolute executive privilege” regarding any communications between high government officials and those who assist and advise them, produced heavily edited transcripts of 43 taped conversations, asking in the same instant that the subpoena be quashed and the transcripts disregarded. The Supreme Court first ruled that the prosecutor had submitted sufficient evidence to obtain the subpoena, then specifically addressed the issue of executive privilege. Nixon’s declaration of an “absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances,” was flatly rejected. In the midst of this “Watergate scandal,” Nixon resigned from office just 15 days later, on August 9, 1974.

The Authority Behind Judicial Review

Interestingly, Article III of the U.S. Constitution does not specifically give the judicial branch the authority of judicial review. It states specifically:

“The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority.”

This language clearly does not state whether the Supreme Court has the power to reverse acts of Congress. The power of judicial review has been garnered by assumption of that power:

- Power From the People . Alexander Hamilton, rather than attempting to prove that the Supreme Court had the power of judicial review, simply assumed it did. He then focused his efforts on persuading the people that the power of judicial review was a positive thing for the people of the land.

- Constitution Binding on Congress . Hamilton referred to the section that states “No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid,” and pointed out that judicial review would be needed to oversee acts of Congress that may violate the Constitution.

- The Supreme Court’s Charge to Interpret the Law . Hamilton observed that the Constitution must be seen as a fundamental law, specifically stated to be the supreme law of the land. As the courts have the distinct responsibility of interpreting the law, the power of judicial review belongs with the Supreme Court.

What Cases are Eligible for Judicial Review

Although one party or another is going to be unhappy with a judgment or verdict in most court cases, not every case is eligible for appeal . In fact, there must be some legal grounds for an appeal, primarily a reversible error in the trial procedures, or the violation of Constitutional rights . Examples of reversible error include:

- Jurisdiction . The court wrongly assumes jurisdiction in a case over which another court has exclusive jurisdiction.

- Admission or Exclusion of Evidence . The court incorrectly applies rules or laws to either admit or deny the admission of certain vital evidence in the case. If such evidence proves to be a key element in the outcome of the trial, the judgment may be reversed on appeal.

- Jury Instructions . If, in giving the jury instructions on how to apply the law to a specific case, the judge has applied the wrong law, or an inaccurate interpretation of the correct law, and that error is found to have been prejudicial to the outcome of the case, the verdict may be overturned on judicial review.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Executive Privilege – The principle that the President of the United States has the right to withhold information from Congress, the courts, and the public, if it jeopardizes national security, or because disclosure of such information would be detrimental to the best interests of the Executive Branch .

- Jim Crow Laws – The legal practice of racial segregation in many states from the 1880s through the 1960s. Named after a popular black character in minstrel shows, the Jim Crow laws imposed punishments for such things as keeping company with members of another race, interracial marriage, and failure of business owners to keep white and black patrons separated.

- Judicial Decision – A decision made by a judge regarding the matter or case at hand.

- Overturn – To change a decision or judgment so that it becomes the opposite of what it was originally.

- Search Warrant – A court order that authorizes law enforcement officers or agents to search a person or a place for the purpose of obtaining evidence or contraband for use in criminal prosecution.

11.1 What Is the Judiciary?

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between rule of law and rule by law.

- Identify the responsibilities of a judicial system.

- Compare and contrast the different methods states and countries use to select judicial officers.

- Discuss major criticisms of each method of judicial selection.

In Chapter 4: Civil Liberties , you learned that law is a body of rules of conduct, with binding legal force and effect, that is prescribed, recognized, and enforced by a controlling authority. In the world today, that authority is usually the government of a particular area. However, multiple levels of government may have authority in a given place. The power of a governmental body to exercise the highest authority in an area is called sovereignty . If a government has sovereignty over a particular region, that government can create and impose rules on people within the region.

Chapter 4: Civil Liberties also introduced the rule of law , the principle that the government is beholden to its laws, not to any individual or group. Throughout history, many individuals and small groups have become dictators with the sole power to create laws and punish people as they wished, thus employing rule by law . There are still some dictators in the world today, as in North Korea . Dictatorships are oppressive, and dictatorial regimes are prone to corruption. By following the rule of law, robust democracies try to avoid these injustices.

Court Shorts: Rule of Law

In this brief video, United States judges who preside over different types and levels of courts discuss the meaning of the rule of law and the role it plays in our everyday lives.

Recall the four principles of the rule of law:

- Accountability: The government and private actors are accountable under the law. No one is above the law.

- Just laws: The laws are clear, publicized, stable, and applied evenly, and they protect fundamental rights, including the security of persons and property and certain core human rights.

- Open government: The processes by which the laws are enacted, administered, and enforced are accessible, fair, and efficient.

- Accessible and impartial dispute resolution: Justice is delivered in a timely manner by competent, ethical, independent, and neutral decision-makers who have adequate resources and reflect the communities they serve.

These principles demonstrate that the government and the people are in a social contract , a voluntary agreement whereby the people consent to abide by specific rules while living in the territory and the government consents to limit itself to acting in accordance with certain standards. This creates a symbiotic relationship between the government and the people, rather than a system based on fear and oppression.