Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Module 2 Chapter 3: What is Empirical Literature & Where can it be Found?

In Module 1, you read about the problem of pseudoscience. Here, we revisit the issue in addressing how to locate and assess scientific or empirical literature . In this chapter you will read about:

- distinguishing between what IS and IS NOT empirical literature

- how and where to locate empirical literature for understanding diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Probably the most important take-home lesson from this chapter is that one source is not sufficient to being well-informed on a topic. It is important to locate multiple sources of information and to critically appraise the points of convergence and divergence in the information acquired from different sources. This is especially true in emerging and poorly understood topics, as well as in answering complex questions.

What Is Empirical Literature

Social workers often need to locate valid, reliable information concerning the dimensions of a population group or subgroup, a social work problem, or social phenomenon. They might also seek information about the way specific problems or resources are distributed among the populations encountered in professional practice. Or, social workers might be interested in finding out about the way that certain people experience an event or phenomenon. Empirical literature resources may provide answers to many of these types of social work questions. In addition, resources containing data regarding social indicators may also prove helpful. Social indicators are the “facts and figures” statistics that describe the social, economic, and psychological factors that have an impact on the well-being of a community or other population group.The United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organization (WHO) are examples of organizations that monitor social indicators at a global level: dimensions of population trends (size, composition, growth/loss), health status (physical, mental, behavioral, life expectancy, maternal and infant mortality, fertility/child-bearing, and diseases like HIV/AIDS), housing and quality of sanitation (water supply, waste disposal), education and literacy, and work/income/unemployment/economics, for example.

Three characteristics stand out in empirical literature compared to other types of information available on a topic of interest: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/replicability/reproducibility. Let’s look a little more closely at these three features.

Systematic Observation and Methodology. The hallmark of empiricism is “repeated or reinforced observation of the facts or phenomena” (Holosko, 2006, p. 6). In empirical literature, established research methodologies and procedures are systematically applied to answer the questions of interest.

Objectivity. Gathering “facts,” whatever they may be, drives the search for empirical evidence (Holosko, 2006). Authors of empirical literature are expected to report the facts as observed, whether or not these facts support the investigators’ original hypotheses. Research integrity demands that the information be provided in an objective manner, reducing sources of investigator bias to the greatest possible extent.

Transparency and Replicability/Reproducibility. Empirical literature is reported in such a manner that other investigators understand precisely what was done and what was found in a particular research study—to the extent that they could replicate the study to determine whether the findings are reproduced when repeated. The outcomes of an original and replication study may differ, but a reader could easily interpret the methods and procedures leading to each study’s findings.

What is NOT Empirical Literature

By now, it is probably obvious to you that literature based on “evidence” that is not developed in a systematic, objective, transparent manner is not empirical literature. On one hand, non-empirical types of professional literature may have great significance to social workers. For example, social work scholars may produce articles that are clearly identified as describing a new intervention or program without evaluative evidence, critiquing a policy or practice, or offering a tentative, untested theory about a phenomenon. These resources are useful in educating ourselves about possible issues or concerns. But, even if they are informed by evidence, they are not empirical literature. Here is a list of several sources of information that do not meet the standard of being called empirical literature:

- your course instructor’s lectures

- political statements

- advertisements

- newspapers & magazines (journalism)

- television news reports & analyses (journalism)

- many websites, Facebook postings, Twitter tweets, and blog postings

- the introductory literature review in an empirical article

You may be surprised to see the last two included in this list. Like the other sources of information listed, these sources also might lead you to look for evidence. But, they are not themselves sources of evidence. They may summarize existing evidence, but in the process of summarizing (like your instructor’s lectures), information is transformed, modified, reduced, condensed, and otherwise manipulated in such a manner that you may not see the entire, objective story. These are called secondary sources, as opposed to the original, primary source of evidence. In relying solely on secondary sources, you sacrifice your own critical appraisal and thinking about the original work—you are “buying” someone else’s interpretation and opinion about the original work, rather than developing your own interpretation and opinion. What if they got it wrong? How would you know if you did not examine the primary source for yourself? Consider the following as an example of “getting it wrong” being perpetuated.

Example: Bullying and School Shootings . One result of the heavily publicized April 1999 school shooting incident at Columbine High School (Colorado), was a heavy emphasis placed on bullying as a causal factor in these incidents (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017), “creating a powerful master narrative about school shootings” (Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017, p. 3). Naturally, with an identified cause, a great deal of effort was devoted to anti-bullying campaigns and interventions for enhancing resilience among youth who experience bullying. However important these strategies might be for promoting positive mental health, preventing poor mental health, and possibly preventing suicide among school-aged children and youth, it is a mistaken belief that this can prevent school shootings (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017). Many times the accounts of the perpetrators having been bullied come from potentially inaccurate third-party accounts, rather than the perpetrators themselves; bullying was not involved in all instances of school shooting; a perpetrator’s perception of being bullied/persecuted are not necessarily accurate; many who experience severe bullying do not perpetrate these incidents; bullies are the least targeted shooting victims; perpetrators of the shooting incidents were often bullying others; and, bullying is only one of many important factors associated with perpetrating such an incident (Ioannou, Hammond, & Simpson, 2015; Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017; Newman &Fox, 2009; Raitanen, Sandberg, & Oksanen, 2017). While mass media reports deliver bullying as a means of explaining the inexplicable, the reality is not so simple: “The connection between bullying and school shootings is elusive” (Langman, 2014), and “the relationship between bullying and school shooting is, at best, tenuous” (Mears, Moon, & Thielo, 2017, p. 940). The point is, when a narrative becomes this publicly accepted, it is difficult to sort out truth and reality without going back to original sources of information and evidence.

What May or May Not Be Empirical Literature: Literature Reviews

Investigators typically engage in a review of existing literature as they develop their own research studies. The review informs them about where knowledge gaps exist, methods previously employed by other scholars, limitations of prior work, and previous scholars’ recommendations for directing future research. These reviews may appear as a published article, without new study data being reported (see Fields, Anderson, & Dabelko-Schoeny, 2014 for example). Or, the literature review may appear in the introduction to their own empirical study report. These literature reviews are not considered to be empirical evidence sources themselves, although they may be based on empirical evidence sources. One reason is that the authors of a literature review may or may not have engaged in a systematic search process, identifying a full, rich, multi-sided pool of evidence reports.

There is, however, a type of review that applies systematic methods and is, therefore, considered to be more strongly rooted in evidence: the systematic review .

Systematic review of literature. A systematic reviewis a type of literature report where established methods have been systematically applied, objectively, in locating and synthesizing a body of literature. The systematic review report is characterized by a great deal of transparency about the methods used and the decisions made in the review process, and are replicable. Thus, it meets the criteria for empirical literature: systematic observation and methodology, objectivity, and transparency/reproducibility. We will work a great deal more with systematic reviews in the second course, SWK 3402, since they are important tools for understanding interventions. They are somewhat less common, but not unheard of, in helping us understand diverse populations, social work problems, and social phenomena.

Locating Empirical Evidence

Social workers have available a wide array of tools and resources for locating empirical evidence in the literature. These can be organized into four general categories.

Journal Articles. A number of professional journals publish articles where investigators report on the results of their empirical studies. However, it is important to know how to distinguish between empirical and non-empirical manuscripts in these journals. A key indicator, though not the only one, involves a peer review process . Many professional journals require that manuscripts undergo a process of peer review before they are accepted for publication. This means that the authors’ work is shared with scholars who provide feedback to the journal editor as to the quality of the submitted manuscript. The editor then makes a decision based on the reviewers’ feedback:

- Accept as is

- Accept with minor revisions

- Request that a revision be resubmitted (no assurance of acceptance)

When a “revise and resubmit” decision is made, the piece will go back through the review process to determine if it is now acceptable for publication and that all of the reviewers’ concerns have been adequately addressed. Editors may also reject a manuscript because it is a poor fit for the journal, based on its mission and audience, rather than sending it for review consideration.

Indicators of journal relevance. Various journals are not equally relevant to every type of question being asked of the literature. Journals may overlap to a great extent in terms of the topics they might cover; in other words, a topic might appear in multiple different journals, depending on how the topic was being addressed. For example, articles that might help answer a question about the relationship between community poverty and violence exposure might appear in several different journals, some with a focus on poverty, others with a focus on violence, and still others on community development or public health. Journal titles are sometimes a good starting point but may not give a broad enough picture of what they cover in their contents.

In focusing a literature search, it also helps to review a journal’s mission and target audience. For example, at least four different journals focus specifically on poverty:

- Journal of Children & Poverty

- Journal of Poverty

- Journal of Poverty and Social Justice

- Poverty & Public Policy

Let’s look at an example using the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice . Information about this journal is located on the journal’s webpage: http://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/journals/journal-of-poverty-and-social-justice . In the section headed “About the Journal” you can see that it is an internationally focused research journal, and that it addresses social justice issues in addition to poverty alone. The research articles are peer-reviewed (there appear to be non-empirical discussions published, as well). These descriptions about a journal are almost always available, sometimes listed as “scope” or “mission.” These descriptions also indicate the sponsorship of the journal—sponsorship may be institutional (a particular university or agency, such as Smith College Studies in Social Work ), a professional organization, such as the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) or the National Association of Social Work (NASW), or a publishing company (e.g., Taylor & Frances, Wiley, or Sage).

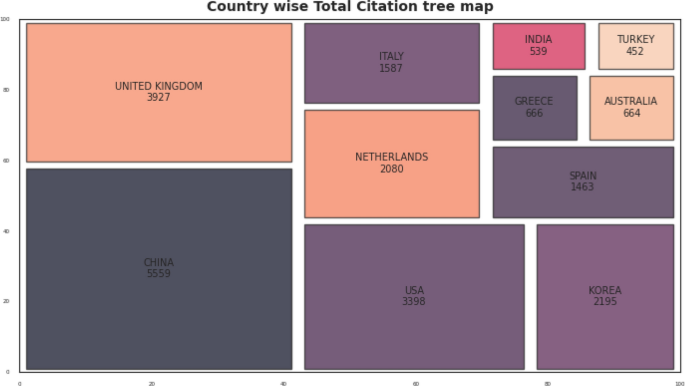

Indicators of journal caliber. Despite engaging in a peer review process, not all journals are equally rigorous. Some journals have very high rejection rates, meaning that many submitted manuscripts are rejected; others have fairly high acceptance rates, meaning that relatively few manuscripts are rejected. This is not necessarily the best indicator of quality, however, since newer journals may not be sufficiently familiar to authors with high quality manuscripts and some journals are very specific in terms of what they publish. Another index that is sometimes used is the journal’s impact factor . Impact factor is a quantitative number indicative of how often articles published in the journal are cited in the reference list of other journal articles—the statistic is calculated as the number of times on average each article published in a particular year were cited divided by the number of articles published (the number that could be cited). For example, the impact factor for the Journal of Poverty and Social Justice in our list above was 0.70 in 2017, and for the Journal of Poverty was 0.30. These are relatively low figures compared to a journal like the New England Journal of Medicine with an impact factor of 59.56! This means that articles published in that journal were, on average, cited more than 59 times in the next year or two.

Impact factors are not necessarily the best indicator of caliber, however, since many strong journals are geared toward practitioners rather than scholars, so they are less likely to be cited by other scholars but may have a large impact on a large readership. This may be the case for a journal like the one titled Social Work, the official journal of the National Association of Social Workers. It is distributed free to all members: over 120,000 practitioners, educators, and students of social work world-wide. The journal has a recent impact factor of.790. The journals with social work relevant content have impact factors in the range of 1.0 to 3.0 according to Scimago Journal & Country Rank (SJR), particularly when they are interdisciplinary journals (for example, Child Development , Journal of Marriage and Family , Child Abuse and Neglect , Child Maltreatmen t, Social Service Review , and British Journal of Social Work ). Once upon a time, a reader could locate different indexes comparing the “quality” of social work-related journals. However, the concept of “quality” is difficult to systematically define. These indexes have mostly been replaced by impact ratings, which are not necessarily the best, most robust indicators on which to rely in assessing journal quality. For example, new journals addressing cutting edge topics have not been around long enough to have been evaluated using this particular tool, and it takes a few years for articles to begin to be cited in other, later publications.

Beware of pseudo-, illegitimate, misleading, deceptive, and suspicious journals . Another side effect of living in the Age of Information is that almost anyone can circulate almost anything and call it whatever they wish. This goes for “journal” publications, as well. With the advent of open-access publishing in recent years (electronic resources available without subscription), we have seen an explosion of what are called predatory or junk journals . These are publications calling themselves journals, often with titles very similar to legitimate publications and often with fake editorial boards. These “publications” lack the integrity of legitimate journals. This caution is reminiscent of the discussions earlier in the course about pseudoscience and “snake oil” sales. The predatory nature of many apparent information dissemination outlets has to do with how scientists and scholars may be fooled into submitting their work, often paying to have their work peer-reviewed and published. There exists a “thriving black-market economy of publishing scams,” and at least two “journal blacklists” exist to help identify and avoid these scam journals (Anderson, 2017).

This issue is important to information consumers, because it creates a challenge in terms of identifying legitimate sources and publications. The challenge is particularly important to address when information from on-line, open-access journals is being considered. Open-access is not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate scientists may pay sizeable fees to legitimate publishers to make their work freely available and accessible as open-access resources. On-line access is also not necessarily a poor choice—legitimate publishers often make articles available on-line to provide timely access to the content, especially when publishing the article in hard copy will be delayed by months or even a year or more. On the other hand, stating that a journal engages in a peer-review process is no guarantee of quality—this claim may or may not be truthful. Pseudo- and junk journals may engage in some quality control practices, but may lack attention to important quality control processes, such as managing conflict of interest, reviewing content for objectivity or quality of the research conducted, or otherwise failing to adhere to industry standards (Laine & Winker, 2017).

One resource designed to assist with the process of deciphering legitimacy is the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ). The DOAJ is not a comprehensive listing of all possible legitimate open-access journals, and does not guarantee quality, but it does help identify legitimate sources of information that are openly accessible and meet basic legitimacy criteria. It also is about open-access journals, not the many journals published in hard copy.

An additional caution: Search for article corrections. Despite all of the careful manuscript review and editing, sometimes an error appears in a published article. Most journals have a practice of publishing corrections in future issues. When you locate an article, it is helpful to also search for updates. Here is an example where data presented in an article’s original tables were erroneous, and a correction appeared in a later issue.

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2017). A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 12(8): e0181722. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5558917/

- Marchant, A., Hawton, K., Stewart A., Montgomery, P., Singaravelu, V., Lloyd, K., Purdy, N., Daine, K., & John, A. (2018).Correction—A systematic review of the relationship between internet use, self-harm and suicidal behaviour in young people: The good, the bad and the unknown. PLoS One, 13(3): e0193937. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0193937

Search Tools. In this age of information, it is all too easy to find items—the problem lies in sifting, sorting, and managing the vast numbers of items that can be found. For example, a simple Google® search for the topic “community poverty and violence” resulted in about 15,600,000 results! As a means of simplifying the process of searching for journal articles on a specific topic, a variety of helpful tools have emerged. One type of search tool has previously applied a filtering process for you: abstracting and indexing databases . These resources provide the user with the results of a search to which records have already passed through one or more filters. For example, PsycINFO is managed by the American Psychological Association and is devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioral science. It contains almost 4.5 million records and is growing every month. However, it may not be available to users who are not affiliated with a university library. Conducting a basic search for our topic of “community poverty and violence” in PsychINFO returned 1,119 articles. Still a large number, but far more manageable. Additional filters can be applied, such as limiting the range in publication dates, selecting only peer reviewed items, limiting the language of the published piece (English only, for example), and specified types of documents (either chapters, dissertations, or journal articles only, for example). Adding the filters for English, peer-reviewed journal articles published between 2010 and 2017 resulted in 346 documents being identified.

Just as was the case with journals, not all abstracting and indexing databases are equivalent. There may be overlap between them, but none is guaranteed to identify all relevant pieces of literature. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the questions asked of the literature:

- Academic Search Complete—multidisciplinary index of 9,300 peer-reviewed journals

- AgeLine—multidisciplinary index of aging-related content for over 600 journals

- Campbell Collaboration—systematic reviews in education, crime and justice, social welfare, international development

- Google Scholar—broad search tool for scholarly literature across many disciplines

- MEDLINE/ PubMed—National Library of medicine, access to over 15 million citations

- Oxford Bibliographies—annotated bibliographies, each is discipline specific (e.g., psychology, childhood studies, criminology, social work, sociology)

- PsycINFO/PsycLIT—international literature on material relevant to psychology and related disciplines

- SocINDEX—publications in sociology

- Social Sciences Abstracts—multiple disciplines

- Social Work Abstracts—many areas of social work are covered

- Web of Science—a “meta” search tool that searches other search tools, multiple disciplines

Placing our search for information about “community violence and poverty” into the Social Work Abstracts tool with no additional filters resulted in a manageable 54-item list. Finally, abstracting and indexing databases are another way to determine journal legitimacy: if a journal is indexed in a one of these systems, it is likely a legitimate journal. However, the converse is not necessarily true: if a journal is not indexed does not mean it is an illegitimate or pseudo-journal.

Government Sources. A great deal of information is gathered, analyzed, and disseminated by various governmental branches at the international, national, state, regional, county, and city level. Searching websites that end in.gov is one way to identify this type of information, often presented in articles, news briefs, and statistical reports. These government sources gather information in two ways: they fund external investigations through grants and contracts and they conduct research internally, through their own investigators. Here are some examples to consider, depending on the nature of the topic for which information is sought:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) at https://www.ahrq.gov/

- Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) at https://www.bjs.gov/

- Census Bureau at https://www.census.gov

- Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of the CDC (MMWR-CDC) at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/index.html

- Child Welfare Information Gateway at https://www.childwelfare.gov

- Children’s Bureau/Administration for Children & Families at https://www.acf.hhs.gov

- Forum on Child and Family Statistics at https://www.childstats.gov

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) at https://www.nih.gov , including (not limited to):

- National Institute on Aging (NIA at https://www.nia.nih.gov

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) at https://www.niaaa.nih.gov

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) at https://www.nichd.nih.gov

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at https://www.nida.nih.gov

- National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences at https://www.niehs.nih.gov

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) at https://www.nimh.nih.gov

- National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at https://www.nimhd.nih.gov

- National Institute of Justice (NIJ) at https://www.nij.gov

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) at https://www.samhsa.gov/

- United States Agency for International Development at https://usaid.gov

Each state and many counties or cities have similar data sources and analysis reports available, such as Ohio Department of Health at https://www.odh.ohio.gov/healthstats/dataandstats.aspx and Franklin County at https://statisticalatlas.com/county/Ohio/Franklin-County/Overview . Data are available from international/global resources (e.g., United Nations and World Health Organization), as well.

Other Sources. The Health and Medicine Division (HMD) of the National Academies—previously the Institute of Medicine (IOM)—is a nonprofit institution that aims to provide government and private sector policy and other decision makers with objective analysis and advice for making informed health decisions. For example, in 2018 they produced reports on topics in substance use and mental health concerning the intersection of opioid use disorder and infectious disease, the legal implications of emerging neurotechnologies, and a global agenda concerning the identification and prevention of violence (see http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/Topics/Substance-Abuse-Mental-Health.aspx ). The exciting aspect of this resource is that it addresses many topics that are current concerns because they are hoping to help inform emerging policy. The caution to consider with this resource is the evidence is often still emerging, as well.

Numerous “think tank” organizations exist, each with a specific mission. For example, the Rand Corporation is a nonprofit organization offering research and analysis to address global issues since 1948. The institution’s mission is to help improve policy and decision making “to help individuals, families, and communities throughout the world be safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous,” addressing issues of energy, education, health care, justice, the environment, international affairs, and national security (https://www.rand.org/about/history.html). And, for example, the Robert Woods Johnson Foundation is a philanthropic organization supporting research and research dissemination concerning health issues facing the United States. The foundation works to build a culture of health across systems of care (not only medical care) and communities (https://www.rwjf.org).

While many of these have a great deal of helpful evidence to share, they also may have a strong political bias. Objectivity is often lacking in what information these organizations provide: they provide evidence to support certain points of view. That is their purpose—to provide ideas on specific problems, many of which have a political component. Think tanks “are constantly researching solutions to a variety of the world’s problems, and arguing, advocating, and lobbying for policy changes at local, state, and federal levels” (quoted from https://thebestschools.org/features/most-influential-think-tanks/ ). Helpful information about what this one source identified as the 50 most influential U.S. think tanks includes identifying each think tank’s political orientation. For example, The Heritage Foundation is identified as conservative, whereas Human Rights Watch is identified as liberal.

While not the same as think tanks, many mission-driven organizations also sponsor or report on research, as well. For example, the National Association for Children of Alcoholics (NACOA) in the United States is a registered nonprofit organization. Its mission, along with other partnering organizations, private-sector groups, and federal agencies, is to promote policy and program development in research, prevention and treatment to provide information to, for, and about children of alcoholics (of all ages). Based on this mission, the organization supports knowledge development and information gathering on the topic and disseminates information that serves the needs of this population. While this is a worthwhile mission, there is no guarantee that the information meets the criteria for evidence with which we have been working. Evidence reported by think tank and mission-driven sources must be utilized with a great deal of caution and critical analysis!

In many instances an empirical report has not appeared in the published literature, but in the form of a technical or final report to the agency or program providing the funding for the research that was conducted. One such example is presented by a team of investigators funded by the National Institute of Justice to evaluate a program for training professionals to collect strong forensic evidence in instances of sexual assault (Patterson, Resko, Pierce-Weeks, & Campbell, 2014): https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/247081.pdf . Investigators may serve in the capacity of consultant to agencies, programs, or institutions, and provide empirical evidence to inform activities and planning. One such example is presented by Maguire-Jack (2014) as a report to a state’s child maltreatment prevention board: https://preventionboard.wi.gov/Documents/InvestmentInPreventionPrograming_Final.pdf .

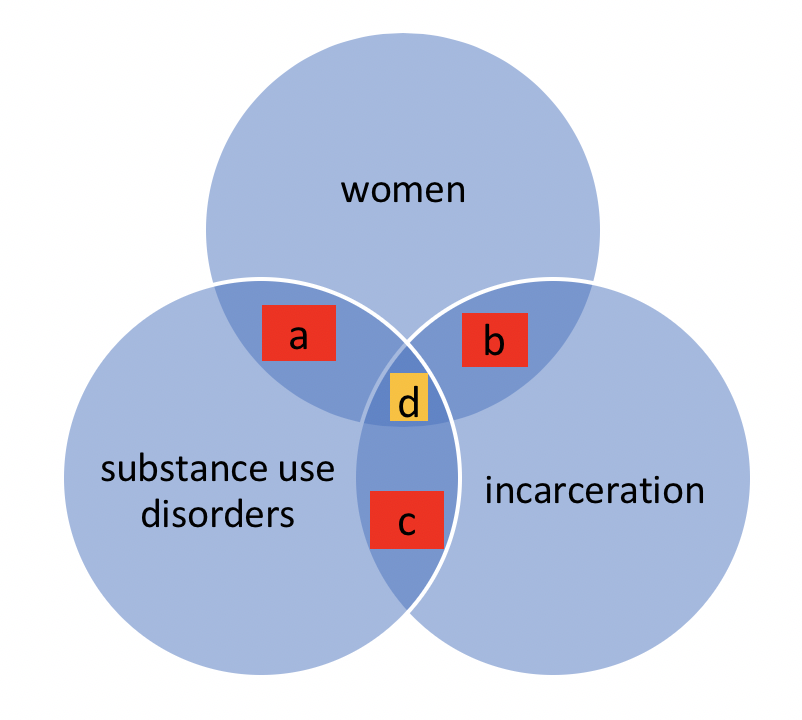

When Direct Answers to Questions Cannot Be Found. Sometimes social workers are interested in finding answers to complex questions or questions related to an emerging, not-yet-understood topic. This does not mean giving up on empirical literature. Instead, it requires a bit of creativity in approaching the literature. A Venn diagram might help explain this process. Consider a scenario where a social worker wishes to locate literature to answer a question concerning issues of intersectionality. Intersectionality is a social justice term applied to situations where multiple categorizations or classifications come together to create overlapping, interconnected, or multiplied disadvantage. For example, women with a substance use disorder and who have been incarcerated face a triple threat in terms of successful treatment for a substance use disorder: intersectionality exists between being a woman, having a substance use disorder, and having been in jail or prison. After searching the literature, little or no empirical evidence might have been located on this specific triple-threat topic. Instead, the social worker will need to seek literature on each of the threats individually, and possibly will find literature on pairs of topics (see Figure 3-1). There exists some literature about women’s outcomes for treatment of a substance use disorder (a), some literature about women during and following incarceration (b), and some literature about substance use disorders and incarceration (c). Despite not having a direct line on the center of the intersecting spheres of literature (d), the social worker can develop at least a partial picture based on the overlapping literatures.

Figure 3-1. Venn diagram of intersecting literature sets.

Take a moment to complete the following activity. For each statement about empirical literature, decide if it is true or false.

Social Work 3401 Coursebook Copyright © by Dr. Audrey Begun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The Research Proposal

83 Components of the Literature Review

Krathwohl (2005) suggests and describes a variety of components to include in a research proposal. The following sections present these components in a suggested template for you to follow in the preparation of your research proposal.

Introduction

The introduction sets the tone for what follows in your research proposal – treat it as the initial pitch of your idea. After reading the introduction your reader should:

- Understand what it is you want to do;

- Have a sense of your passion for the topic;

- Be excited about the study´s possible outcomes.

As you begin writing your research proposal it is helpful to think of the introduction as a narrative of what it is you want to do, written in one to three paragraphs. Within those one to three paragraphs, it is important to briefly answer the following questions:

- What is the central research problem?

- How is the topic of your research proposal related to the problem?

- What methods will you utilize to analyze the research problem?

- Why is it important to undertake this research? What is the significance of your proposed research? Why are the outcomes of your proposed research important, and to whom or to what are they important?

Note : You may be asked by your instructor to include an abstract with your research proposal. In such cases, an abstract should provide an overview of what it is you plan to study, your main research question, a brief explanation of your methods to answer the research question, and your expected findings. All of this information must be carefully crafted in 150 to 250 words. A word of advice is to save the writing of your abstract until the very end of your research proposal preparation. If you are asked to provide an abstract, you should include 5-7 key words that are of most relevance to your study. List these in order of relevance.

Background and significance

The purpose of this section is to explain the context of your proposal and to describe, in detail, why it is important to undertake this research. Assume that the person or people who will read your research proposal know nothing or very little about the research problem. While you do not need to include all knowledge you have learned about your topic in this section, it is important to ensure that you include the most relevant material that will help to explain the goals of your research.

While there are no hard and fast rules, you should attempt to address some or all of the following key points:

- State the research problem and provide a more thorough explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction.

- Present the rationale for the proposed research study. Clearly indicate why this research is worth doing. Answer the “so what?” question.

- Describe the major issues or problems to be addressed by your research. Do not forget to explain how and in what ways your proposed research builds upon previous related research.

- Explain how you plan to go about conducting your research.

- Clearly identify the key or most relevant sources of research you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Set the boundaries of your proposed research, in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you will study, but what will be excluded from your study.

- Provide clear definitions of key concepts and terms. As key concepts and terms often have numerous definitions, make sure you state which definition you will be utilizing in your research.

Literature Review

This is the most time-consuming aspect in the preparation of your research proposal and it is a key component of the research proposal. As described in Chapter 5 , the literature review provides the background to your study and demonstrates the significance of the proposed research. Specifically, it is a review and synthesis of prior research that is related to the problem you are setting forth to investigate. Essentially, your goal in the literature review is to place your research study within the larger whole of what has been studied in the past, while demonstrating to your reader that your work is original, innovative, and adds to the larger whole.

As the literature review is information dense, it is essential that this section be intelligently structured to enable your reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your study. However, this can be easier to state and harder to do, simply due to the fact there is usually a plethora of related research to sift through. Consequently, a good strategy for writing the literature review is to break the literature into conceptual categories or themes, rather than attempting to describe various groups of literature you reviewed. Chapter V, “ The Literature Review ,” describes a variety of methods to help you organize the themes.

Here are some suggestions on how to approach the writing of your literature review:

- Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methods they used, what they found, and what they recommended based upon their findings.

- Do not be afraid to challenge previous related research findings and/or conclusions.

- Assess what you believe to be missing from previous research and explain how your research fills in this gap and/or extends previous research

It is important to note that a significant challenge related to undertaking a literature review is knowing when to stop. As such, it is important to know how to know when you have uncovered the key conceptual categories underlying your research topic. Generally, when you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations, you can have confidence that you have covered all of the significant conceptual categories in your literature review. However, it is also important to acknowledge that researchers often find themselves returning to the literature as they collect and analyze their data. For example, an unexpected finding may develop as one collects and/or analyzes the data and it is important to take the time to step back and review the literature again, to ensure that no other researchers have found a similar finding. This may include looking to research outside your field.

This situation occurred with one of the authors of this textbook´s research related to community resilience. During the interviews, the researchers heard many participants discuss individual resilience factors and how they believed these individual factors helped make the community more resilient, overall. Sheppard and Williams (2016) had not discovered these individual factors in their original literature review on community and environmental resilience. However, when they returned to the literature to search for individual resilience factors, they discovered a small body of literature in the child and youth psychology field. Consequently, Sheppard and Williams had to go back and add a new section to their literature review on individual resilience factors. Interestingly, their research appeared to be the first research to link individual resilience factors with community resilience factors.

Research design and methods

The objective of this section of the research proposal is to convince the reader that your overall research design and methods of analysis will enable you to solve the research problem you have identified and also enable you to accurately and effectively interpret the results of your research. Consequently, it is critical that the research design and methods section is well-written, clear, and logically organized. This demonstrates to your reader that you know what you are going to do and how you are going to do it. Overall, you want to leave your reader feeling confident that you have what it takes to get this research study completed in a timely fashion.

Essentially, this section of the research proposal should be clearly tied to the specific objectives of your study; however, it is also important to draw upon and include examples from the literature review that relate to your design and intended methods. In other words, you must clearly demonstrate how your study utilizes and builds upon past studies, as it relates to the research design and intended methods. For example, what methods have been used by other researchers in similar studies?

While it is important to consider the methods that other researchers have employed, it is equally important, if not more so, to consider what methods have not been employed but could be. Remember, the methods section is not simply a list of tasks to be undertaken. It is also an argument as to why and how the tasks you have outlined will help you investigate the research problem and answer your research question(s).

Tips for writing the research design and methods section:

- Specify the methodological approaches you intend to employ to obtain information and the techniques you will use to analyze the data.

- Specify the research operations you will undertake and he way you will interpret the results of those operations in relation to the research problem.

- Go beyond stating what you hope to achieve through the methods you have chosen. State how you will actually do the methods (i.e. coding interview text, running regression analysis, etc.).

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers you may encounter when undertaking your research and describe how you will address these barriers.

- Explain where you believe you will find challenges related to data collection, including access to participants and information.

Preliminary suppositions and implications

The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you anticipate that your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the area of your study. Depending upon the aims and objectives of your study, you should also discuss how your anticipated findings may impact future research. For example, is it possible that your research may lead to a new policy, new theoretical understanding, or a new method for analyzing data? How might your study influence future studies? What might your study mean for future practitioners working in the field? Who or what may benefit from your study? How might your study contribute to social, economic, environmental issues? While it is important to think about and discuss possibilities such as these, it is equally important to be realistic in stating your anticipated findings. In other words, you do not want to delve into idle speculation. Rather, the purpose here is to reflect upon gaps in the current body of literature and to describe how and in what ways you anticipate your research will begin to fill in some or all of those gaps.

The conclusion reiterates the importance and significance of your research proposal and it provides a brief summary of the entire proposed study. Essentially, this section should only be one or two paragraphs in length. Here is a potential outline for your conclusion:

- Discuss why the study should be done. Specifically discuss how you expect your study will advance existing knowledge and how your study is unique.

- Explain the specific purpose of the study and the research questions that the study will answer.

- Explain why the research design and methods chosen for this study are appropriate, and why other design and methods were not chosen.

- State the potential implications you expect to emerge from your proposed study,

- Provide a sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship currently in existence related to the research problem.

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used in composing your research proposal. In a research proposal, this can take two forms: a reference list or a bibliography. A reference list does what the name suggests, it lists the literature you referenced in the body of your research proposal. All references in the reference list, must appear in the body of the research proposal. Remember, it is not acceptable to say “as cited in …” As a researcher you must always go to the original source and check it for yourself. Many errors are made in referencing, even by top researchers, and so it is important not to perpetuate an error made by someone else. While this can be time consuming, it is the proper way to undertake a literature review.

In contrast, a bibliography , is a list of everything you used or cited in your research proposal, with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem. In other words, sources cited in your bibliography may not necessarily appear in the body of your research proposal. Make sure you check with your instructor to see which of the two you are expected to produce.

Overall, your list of citations should be a testament to the fact that you have done a sufficient level of preliminary research to ensure that your project will complement, but not duplicate, previous research efforts. For social sciences, the reference list or bibliography should be prepared in American Psychological Association (APA) referencing format. Usually, the reference list (or bibliography) is not included in the word count of the research proposal. Again, make sure you check with your instructor to confirm.

An Introduction to Research Methods in Sociology Copyright © 2019 by Valerie A. Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 3 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

How To Structure Your Literature Review

3 options to help structure your chapter.

By: Amy Rommelspacher (PhD) | Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | November 2020 (Updated May 2023)

Writing the literature review chapter can seem pretty daunting when you’re piecing together your dissertation or thesis. As we’ve discussed before , a good literature review needs to achieve a few very important objectives – it should:

- Demonstrate your knowledge of the research topic

- Identify the gaps in the literature and show how your research links to these

- Provide the foundation for your conceptual framework (if you have one)

- Inform your own methodology and research design

To achieve this, your literature review needs a well-thought-out structure . Get the structure of your literature review chapter wrong and you’ll struggle to achieve these objectives. Don’t worry though – in this post, we’ll look at how to structure your literature review for maximum impact (and marks!).

But wait – is this the right time?

Deciding on the structure of your literature review should come towards the end of the literature review process – after you have collected and digested the literature, but before you start writing the chapter.

In other words, you need to first develop a rich understanding of the literature before you even attempt to map out a structure. There’s no use trying to develop a structure before you’ve fully wrapped your head around the existing research.

Equally importantly, you need to have a structure in place before you start writing , or your literature review will most likely end up a rambling, disjointed mess.

Importantly, don’t feel that once you’ve defined a structure you can’t iterate on it. It’s perfectly natural to adjust as you engage in the writing process. As we’ve discussed before , writing is a way of developing your thinking, so it’s quite common for your thinking to change – and therefore, for your chapter structure to change – as you write.

Need a helping hand?

Like any other chapter in your thesis or dissertation, your literature review needs to have a clear, logical structure. At a minimum, it should have three essential components – an introduction , a body and a conclusion .

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

1: The Introduction Section

Just like any good introduction, the introduction section of your literature review should introduce the purpose and layout (organisation) of the chapter. In other words, your introduction needs to give the reader a taste of what’s to come, and how you’re going to lay that out. Essentially, you should provide the reader with a high-level roadmap of your chapter to give them a taste of the journey that lies ahead.

Here’s an example of the layout visualised in a literature review introduction:

Your introduction should also outline your topic (including any tricky terminology or jargon) and provide an explanation of the scope of your literature review – in other words, what you will and won’t be covering (the delimitations ). This helps ringfence your review and achieve a clear focus . The clearer and narrower your focus, the deeper you can dive into the topic (which is typically where the magic lies).

Depending on the nature of your project, you could also present your stance or point of view at this stage. In other words, after grappling with the literature you’ll have an opinion about what the trends and concerns are in the field as well as what’s lacking. The introduction section can then present these ideas so that it is clear to examiners that you’re aware of how your research connects with existing knowledge .

2: The Body Section

The body of your literature review is the centre of your work. This is where you’ll present, analyse, evaluate and synthesise the existing research. In other words, this is where you’re going to earn (or lose) the most marks. Therefore, it’s important to carefully think about how you will organise your discussion to present it in a clear way.

The body of your literature review should do just as the description of this chapter suggests. It should “review” the literature – in other words, identify, analyse, and synthesise it. So, when thinking about structuring your literature review, you need to think about which structural approach will provide the best “review” for your specific type of research and objectives (we’ll get to this shortly).

There are (broadly speaking) three options for organising your literature review.

Option 1: Chronological (according to date)

Organising the literature chronologically is one of the simplest ways to structure your literature review. You start with what was published first and work your way through the literature until you reach the work published most recently. Pretty straightforward.

The benefit of this option is that it makes it easy to discuss the developments and debates in the field as they emerged over time. Organising your literature chronologically also allows you to highlight how specific articles or pieces of work might have changed the course of the field – in other words, which research has had the most impact . Therefore, this approach is very useful when your research is aimed at understanding how the topic has unfolded over time and is often used by scholars in the field of history. That said, this approach can be utilised by anyone that wants to explore change over time .

For example , if a student of politics is investigating how the understanding of democracy has evolved over time, they could use the chronological approach to provide a narrative that demonstrates how this understanding has changed through the ages.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to help you structure your literature review chronologically.

- What is the earliest literature published relating to this topic?

- How has the field changed over time? Why?

- What are the most recent discoveries/theories?

In some ways, chronology plays a part whichever way you decide to structure your literature review, because you will always, to a certain extent, be analysing how the literature has developed. However, with the chronological approach, the emphasis is very firmly on how the discussion has evolved over time , as opposed to how all the literature links together (which we’ll discuss next ).

Option 2: Thematic (grouped by theme)

The thematic approach to structuring a literature review means organising your literature by theme or category – for example, by independent variables (i.e. factors that have an impact on a specific outcome).

As you’ve been collecting and synthesising literature , you’ll likely have started seeing some themes or patterns emerging. You can then use these themes or patterns as a structure for your body discussion. The thematic approach is the most common approach and is useful for structuring literature reviews in most fields.

For example, if you were researching which factors contributed towards people trusting an organisation, you might find themes such as consumers’ perceptions of an organisation’s competence, benevolence and integrity. Structuring your literature review thematically would mean structuring your literature review’s body section to discuss each of these themes, one section at a time.

Here are some questions to ask yourself when structuring your literature review by themes:

- Are there any patterns that have come to light in the literature?

- What are the central themes and categories used by the researchers?

- Do I have enough evidence of these themes?

PS – you can see an example of a thematically structured literature review in our literature review sample walkthrough video here.

Option 3: Methodological

The methodological option is a way of structuring your literature review by the research methodologies used . In other words, organising your discussion based on the angle from which each piece of research was approached – for example, qualitative , quantitative or mixed methodologies.

Structuring your literature review by methodology can be useful if you are drawing research from a variety of disciplines and are critiquing different methodologies. The point of this approach is to question how existing research has been conducted, as opposed to what the conclusions and/or findings the research were.

For example, a sociologist might centre their research around critiquing specific fieldwork practices. Their literature review will then be a summary of the fieldwork methodologies used by different studies.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself when structuring your literature review according to methodology:

- Which methodologies have been utilised in this field?

- Which methodology is the most popular (and why)?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the various methodologies?

- How can the existing methodologies inform my own methodology?

3: The Conclusion Section

Once you’ve completed the body section of your literature review using one of the structural approaches we discussed above, you’ll need to “wrap up” your literature review and pull all the pieces together to set the direction for the rest of your dissertation or thesis.

The conclusion is where you’ll present the key findings of your literature review. In this section, you should emphasise the research that is especially important to your research questions and highlight the gaps that exist in the literature. Based on this, you need to make it clear what you will add to the literature – in other words, justify your own research by showing how it will help fill one or more of the gaps you just identified.

Last but not least, if it’s your intention to develop a conceptual framework for your dissertation or thesis, the conclusion section is a good place to present this.

Example: Thematically Structured Review

In the video below, we unpack a literature review chapter so that you can see an example of a thematically structure review in practice.

Let’s Recap

In this article, we’ve discussed how to structure your literature review for maximum impact. Here’s a quick recap of what you need to keep in mind when deciding on your literature review structure:

- Just like other chapters, your literature review needs a clear introduction , body and conclusion .

- The introduction section should provide an overview of what you will discuss in your literature review.

- The body section of your literature review can be organised by chronology , theme or methodology . The right structural approach depends on what you’re trying to achieve with your research.

- The conclusion section should draw together the key findings of your literature review and link them to your research questions.

If you’re ready to get started, be sure to download our free literature review template to fast-track your chapter outline.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

27 Comments

Great work. This is exactly what I was looking for and helps a lot together with your previous post on literature review. One last thing is missing: a link to a great literature chapter of an journal article (maybe with comments of the different sections in this review chapter). Do you know any great literature review chapters?

I agree with you Marin… A great piece

I agree with Marin. This would be quite helpful if you annotate a nicely structured literature from previously published research articles.

Awesome article for my research.

I thank you immensely for this wonderful guide

It is indeed thought and supportive work for the futurist researcher and students

Very educative and good time to get guide. Thank you

Great work, very insightful. Thank you.

Thanks for this wonderful presentation. My question is that do I put all the variables into a single conceptual framework or each hypothesis will have it own conceptual framework?

Thank you very much, very helpful

This is very educative and precise . Thank you very much for dropping this kind of write up .

Pheeww, so damn helpful, thank you for this informative piece.

I’m doing a research project topic ; stool analysis for parasitic worm (enteric) worm, how do I structure it, thanks.

comprehensive explanation. Help us by pasting the URL of some good “literature review” for better understanding.

great piece. thanks for the awesome explanation. it is really worth sharing. I have a little question, if anyone can help me out, which of the options in the body of literature can be best fit if you are writing an architectural thesis that deals with design?

I am doing a research on nanofluids how can l structure it?

Beautifully clear.nThank you!

Lucid! Thankyou!

Brilliant work, well understood, many thanks

I like how this was so clear with simple language 😊😊 thank you so much 😊 for these information 😊

Insightful. I was struggling to come up with a sensible literature review but this has been really helpful. Thank you!

You have given thought-provoking information about the review of the literature.

Thank you. It has made my own research better and to impart your work to students I teach

I learnt a lot from this teaching. It’s a great piece.

I am doing research on EFL teacher motivation for his/her job. How Can I structure it? Is there any detailed template, additional to this?

You are so cool! I do not think I’ve read through something like this before. So nice to find somebody with some genuine thoughts on this issue. Seriously.. thank you for starting this up. This site is one thing that is required on the internet, someone with a little originality!

I’m asked to do conceptual, theoretical and empirical literature, and i just don’t know how to structure it

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Learning objectives.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the purpose of the literature review in the research process

- Distinguish between different types of literature reviews

1.1 What is a Literature Review?

Pick up nearly any book on research methods and you will find a description of a literature review. At a basic level, the term implies a survey of factual or nonfiction books, articles, and other documents published on a particular subject. Definitions may be similar across the disciplines, with new types and definitions continuing to emerge. Generally speaking, a literature review is a:

- “comprehensive background of the literature within the interested topic area…” ( O’Gorman & MacIntosh, 2015, p. 31 ).

- “critical component of the research process that provides an in-depth analysis of recently published research findings in specifically identified areas of interest.” ( House, 2018, p. 109 ).

- “written document that presents a logically argued case founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about a topic of study” ( Machi & McEvoy, 2012, p. 4 ).

As a foundation for knowledge advancement in every discipline, it is an important element of any research project. At the graduate or doctoral level, the literature review is an essential feature of thesis and dissertation, as well as grant proposal writing. That is to say, “A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research…A researcher cannot perform significant research without first understanding the literature in the field.” ( Boote & Beile, 2005, p. 3 ). It is by this means, that a researcher demonstrates familiarity with a body of knowledge and thereby establishes credibility with a reader. An advanced-level literature review shows how prior research is linked to a new project, summarizing and synthesizing what is known while identifying gaps in the knowledge base, facilitating theory development, closing areas where enough research already exists, and uncovering areas where more research is needed. ( Webster & Watson, 2002, p. xiii )

A graduate-level literature review is a compilation of the most significant previously published research on your topic. Unlike an annotated bibliography or a research paper you may have written as an undergraduate, your literature review will outline, evaluate and synthesize relevant research and relate those sources to your own thesis or research question. It is much more than a summary of all the related literature.

It is a type of writing that demonstrate the importance of your research by defining the main ideas and the relationship between them. A good literature review lays the foundation for the importance of your stated problem and research question.

Literature reviews:

- define a concept

- map the research terrain or scope

- systemize relationships between concepts

- identify gaps in the literature ( Rocco & Plathotnik, 2009, p. 128 )