Powerful online learning at your pace

Using Strip Diagrams as a Problem-Solving Strategy

There’s a lot to be learned from the data that comes from state testing if we use it correctly . Oftentimes, we’ll take a problem that students, as a whole, perform poorly on and we create a bunch of problems just like that one and “teach” them how to work that type of problem. In the end, that’s not an effective strategy, because they’ll probably never see a problem exactly like that one again. A more effective way to use the data is to analyze the wrong answers to determine underlying misconceptions that resulted in the wrong answers and provide students with strategies and tools to improve their overall mathematical reasoning. As far as strategies go, drawing strip diagrams is one of the most powerful strategies students can have in their toolbox. And I have some super clear examples to persuade you!

This post contains affiliate links, which simply means that when you use my link and purchase a product, I receive a small commission. There is no additional cost to you, and I only link to books and products that I personally use and recommend.

The test items in this post come from the 2021 State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) test. A wonderful organization called lead4ward analyzes the test each year and provides error analysis statistics.

Analyzing errors

Let’s get started! As you can see from this test item, only roughly half of the students in the state got the correct answer. Look at the most common wrong answer, choice H. Can you see the error that the students who chose that answer made? Take a minute to figure it out before you scroll down.

Look closely at the order of the numbers in the problem. The smaller number comes first in the problem. Students who chose H realized it was a subtraction problem, but took the numbers in order from the problem and subtracted them. So they did 379 – 514. Nine minus 4 is 5. Seven minus 1 is 6. They couldn’t do 3 minus 5, so they did 5 minus 3. The answer they got was 265. Your first thought might be, I need to make sure my students always know to subtract the smaller number from the bigger number. Except that’s not true. If the temperature is 18 degrees and the temperature drops 29 degrees… We need to be extremely careful to not teach “rules” that expire .

The students who chose H lacked an understanding of the meaning of the numbers in the problem. The way we help them be more successful with problems like this is to give them tools to improve their comprehension of word problems and the numbers they contain. Enter strip diagrams.

Using drawings to describe problems

Drawing strip diagrams is a process that actually begins in Kindergarten and 1st grade when students should be drawing pictures to represent word problems. Students should understand that the numbers in a problem represent something—pizzas, soccer players, apples, money saved—and their drawings should include labels identifying what the numbers represent. At this point, the drawings don’t need to resemble strip diagrams. What’s important is the labeling. It could look something like what you see here.

Notice a couple of things. First, the boys and girls are represented by circles. Easy to draw and count. Students need to understand that these are math pictures, not art pictures. Next, and of critical importance, are the labels.

Beginning in 2nd grade, students can begin to draw more formal strip diagrams. Strip diagrams, also called tape diagrams, are often associated with Singapore Math. Char Forsten’s Step-by-Step Model Drawing is the book I learned model drawing from. Another great resource is Math Playground’s Thinking Blocks .

Modeling how to draw a strip diagram

Now let’s get back to that released test item I started this post with and see what the model-drawing process might look like.

This problem is a comparison subtraction problem. We always want students to draw the model with labels first. they will add the numbers in the next step.

Teacher: [Reads problem out loud] What is this story about? (lions) How many lions? (2) What does the problem tell us about the lions? (their weight) Do we know their weights? (yes) Which lion weighs more? (the older lion) What is the problem asking us to find? (the difference in their weights) Huh, what does that mean? (The older lion weighs more than the younger lion. The problem is asking how much more.)

NOTE: Notice that we didn’t talk about the numbers at all! The point of this discussion is to help students make sense of the numbers in the problem and verbalize what the problem is asking them to find.

Teacher: Drawing a model really helps me understand what math I need to do to solve a problem. Let’s draw a model to represent this problem. We know that the older lion weights more, so his bar should be longer, right? [draws and labels the older lion’s bar] That means the younger lion’s bar should be shorter. [draws and labels younger lion’s bar] And you guys told me the problem is asking for the difference. [adds the difference with a question mark]

Now we can plug in the numbers from the problem.

Notice that what I’ve described is very scripted. I want students to hear my mathematical thinking, and I’m teaching them the mechanics of drawing the model. But it’s important to let students use the tool to solve problems. Think how the models would look for these variations of the problem:

There are two lions at the zoo. The weight of the younger lion is 379 pounds. That’s 135 less than the weight of the older lion. How much does the older lion weigh?

There are two lions at the zoo. The weight of the older lion is 514. That’s 135 more than the weight of the younger lion. How much does the younger lion weigh?

Remember, our goal is for students to be able to use strip diagrams to solve new types of problems, so once they understand and can use the model, we have to give them new types of problems to solve without scripted instruction.

More examples of strip diagrams

Let’s take a look at a few more problems from the same test. Each of these problems had pretty dismal results.

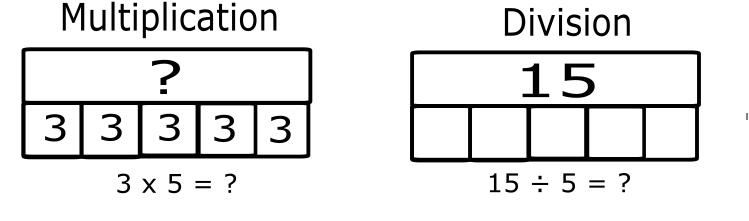

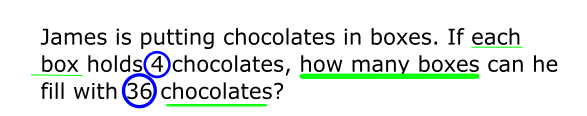

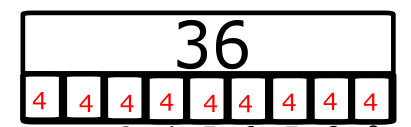

This first problem is what we in Texas call a gridable . That means it’s not multiple choice—students have to write and bubble in their answers. A lot of times students will miss gridables due to calculation errors. But I’m pretty sure that’s not the case here. I doubt they miscalculated 4 x 5. What that means is that 38% of the 3rd-grade students in Texas did not recognize this as a multiplication problem. They likely added 4 + 5. Teaching keywords could be the culprit. Students see the word total in the problem, and they’ve been taught that total means addition. Teaching keywords basically gives students permission to not read and understand the problem—just find the keyword and plug the numbers into the operation. Not a sound problem-solving strategy. Instead, we see how a strip diagram could be drawn to represent the problem.

Here’s another multiplication problem. You can see from the error analysis that only 52% of the 3rd-graders correctly answered this problem. Answers B and D are calculation errors. Can you figure out the error these students made? Doing so can help you prevent these types of errors by addressing them in your instruction. Answer choice C results from adding the two numbers, not multiplying. Again, we see the keyword total in the question. Drawing a model would not only help the students visualize the problem as multiplication, but it might also prevent calculation errors. Students who are not confident with the standard algorithm could solve the problem with repeated addition.

Last one and it’s a doozy! Look at that error distribution. When it’s spread out like that, it usually means the kids just didn’t have a clue and guessed. There’s a lot going on here. How could we help students tackle a problem like this?

First, of course, is drawing a model. We see that this is a part/whole problem with three parts, one of which is missing. If you looked carefully at the wrong answers, answer choice F was adding all three numbers. Pretty hard to look at this model and think you’re supposed to add all three numbers.

Aside from model drawing, however, students should learn to write equations to match their models. That’s really the other thing that was hard about this problem. They weren’t asked to solve the problem, just find the correct way to solve it.

Final thoughts

Strip diagrams have to be presented to students as a problem-solving tool and they have to be used consistently. Yes, it takes longer for students to draw strip diagrams to represent their problems, but it should be an expectation. That means we probably need to assign fewer problems to allow students the time to draw their strip diagrams.

The labels are a must! If students can’t label their numbers, it’s a huge red flag. Work with those students in small groups to help them develop comprehension skills.

Students who say they know the answer without drawing a strip diagram should be reminded that we draw models when the problems are easy so we can use them as a problem-solving tool when the problems get harder. And if a large percentage of students can really solve the problems without drawing models are we challenging them enough?

So there you have it. Have I sold you on having students draw strip diagrams? Do you have tips of your own to share? I hope you’ll sound off in the comments.

Similar Posts

Hundred Chart Assessment

This is a short follow-up to a previous post on teaching the patterns on the hundred chart. This quick little assessment can help you determine if students truly understand the…

Equivalent Fractions Freebie!

The holiday season is approaching and I am again humbled and appreciative of the love and support of Math Coach’s Corner followers! Your comments inspire and encourage me, lift my…

CRA for Adding Three Addends

I talk a LOT about teaching using the concrete–>representational–>abstract (CRA) sequence of instruction. Since I’m often involved in remediation, I see the results of kiddos who are rushed to the abstract…

St. Patrick’s Day FREEBIE for Making 10

Ten holds special importance in our number system. It’s no wonder, then, that a critical Kindergarten skill is knowing all of the combinations for making ten. With St. Patrick’s Day…

Gingerbread Shake and Spill

One of my favorite activities for composing and decomposing numbers is Shake and Spill, due in large part to how flexibly it can be used. We often use it to…

Fact Practice Your Students Will Love!

Kids are competitive. Heck, adults are competitive. Add a little competition to your fact practice activities and you’re sure to have a hit on your hands. I call this game…

13 Comments

Strip/bar/tape diagrams are becoming one of my favorite strategies. The labels are crucial and I need to be better at expecting that. I am nearly to the part of 3rd grade where I will be teaching 2 step problems again and I think continuing the strip/tape/bar diagram representation is going to be a wonderful tool. Here’s hoping!

Thanks for your comment, Jessica! They are one of my favorites as well. So very powerful! Come back and let us know how it goes.

Any way we can show visuals for problems are going to support student understanding! Thank you for adding another tool to my teaching tool box! I teach 1st grade and I want to build my students’ confidence and understanding of math!

That’s wonderful, Suzanne! It’s so important that our students develop a positive math identity early.

Hi Donna, I am increasingly interested in the connections between literacy and math. Your post about how kids start by representing their mathematical thinking/problem solving with pictures, then labels, then drawing a model and later abstract number sentences. seems so similar to how young children write stories first with pictures, then we ask them to label and later on write sentences with words, punctuation etc. Do you know of any research linking the two? Thanks! Jennifer

You are so very correct! There are tons of professional books connecting the two. Solving word problems requires comprehension of the problem. Just like reading teachers tell their students to “make a movie in their head” when they read, I tell my math students the very same thing!

Thank you so much for breaking down strip diagrams. This is a tool I try to encourage my students to use, but I feel like I need to do more modeling for them after reading this. I also like how you pointed out we should analyze the best wrong answers for misconceptions.

I have been using strip diagrams to teach my 2nd graders for a few years. They always seem to struggle with understanding where to put the numbers when the story is comparing. How many more toys does Grant have than Amanda? So, I always pointed out that it’s a comparison, and that seemed to help. I am now a K-5 math interventionist and some upper grades teachers think it will be confusing to call that a comparison when they are not using >, <, = symbols. How can I help them understand those problem types, and is there harm in using the word comparison? I think they are still comparing – "how many more".

A strip diagram for comparison looks different. It’s one bar on top of the other. The difference is where the longer bar is shorter than the shorter bar. That might help with the confusion. Absolutely use the word comparison!

Hi Donna. I’m wondering how strip diagrams are any different than the part part whole organizer. They seem so similar to me. I’ve done a lot of work getting my students to use and understand the PPW as a tool. I like the idea of the strip diagram but fear I’ll confuse them if I introduce a new tool to use in place of a PPW.

They are very similar! Often students transition to strip diagrams in the intermediate elementary grades. No need to do both though.

Hi Donna! I started using tape diagrams with my students when my district adopted the Engage NY/Eureka Math Curriculum. I found that students have had great success in using this strategy. Thank you for this clear explanation on using tape diagrams during problem solving.

It’s such a powerful strategy! I’m glad to hear your students found success using it!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Because differences are our greatest strength

Dividing fractions using fraction strips: An evidence-based math strategy

By Brendan R. Hodnett, MAT

Expert reviewed by Sarah R. Powell, PhD

What you’ll learn

Download: printable fraction strips, read: how to use this strategy, understand: why fraction strips work, connect: link school to home, research behind this strategy.

Dividing fractions can be really tough for many students. It’s hard to visualize splitting a fraction up into groups of other fractions. To divide fractions, many students memorize the “keep-change-flip” algorithm without knowing why it works.

Without a conceptual understanding of dividing fractions, students tend to get stuck when they come across problems (especially word problems) where they have to divide by non-unit fractions like 2/3 or 3/4, or problems where the divisor is larger than the dividend.

By sixth grade, when students need to divide mixed numbers, they often rely heavily on the multi-step “keep-change-flip” method that is hard to memorize and understand.

You can help your students understand how to divide fractions by using fraction strips that they can move around. Manipulatives and visual representations are evidence-based strategies that support learning new math concepts. Fraction strips can help students not only understand the concept of dividing fractions, but literally see how to solve these problems without having to do any calculations.

Fraction strips PDF - 32.9 KB

Objective: Students will use fractions strips to show and solve the division of two fractions.

Grade levels (with standards):

5 (Common Core 5.NF.B.7 : Apply and extend previous understandings of division to divide unit fractions by whole numbers and whole numbers by unit fractions)

5 (Common Core 5.NF.B.7.B : Interpret division of a whole number by a unit fraction, and compute such quotients)

6 (Common Core 6.NS.A.1 : Interpret and compute quotients of fractions, and solve word problems involving division of fractions by fractions, e.g., by using visual fraction models and equations to represent the problem)

5–6 (Common Core Math Practice MP1: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them; Common Core Math Practice MP5: Use appropriate tools strategically)

Best used for instruction with:

Whole class

Small groups

Individuals

How to prepare:

Gather and explore materials. Give each student or pair of students a set of fraction strips. Have students cut each strip into unit fractions (with a numerator of 1). For students who struggle with fine motor skills, consider having a few sets already cut out. You could also make a few laminated or card stock sets for students.

After cutting each strip into unit fractions, have students reassemble each of the strips so they have a complete set that matches what’s in the printable. Give students a copy of the printable, or project an image of the printable so they have a visual model to refer to.

Once students have all the strips arranged, reintroduce the concept of a whole. Remind students that the visual representation of 1 and the word “whole” are often interchangeable when we talk about fractions. Say, “At the top of our set we have 1 whole piece.” Then, ask students what they notice about the strips beneath the whole piece. Model an example. You could say, “I notice that each row of fractions strips is the same size.” Have students share what they notice with a partner. Then ask a few students to share with the entire class. Remind students of previous lessons where they worked on dividing whole numbers by fractions.

How to teach:

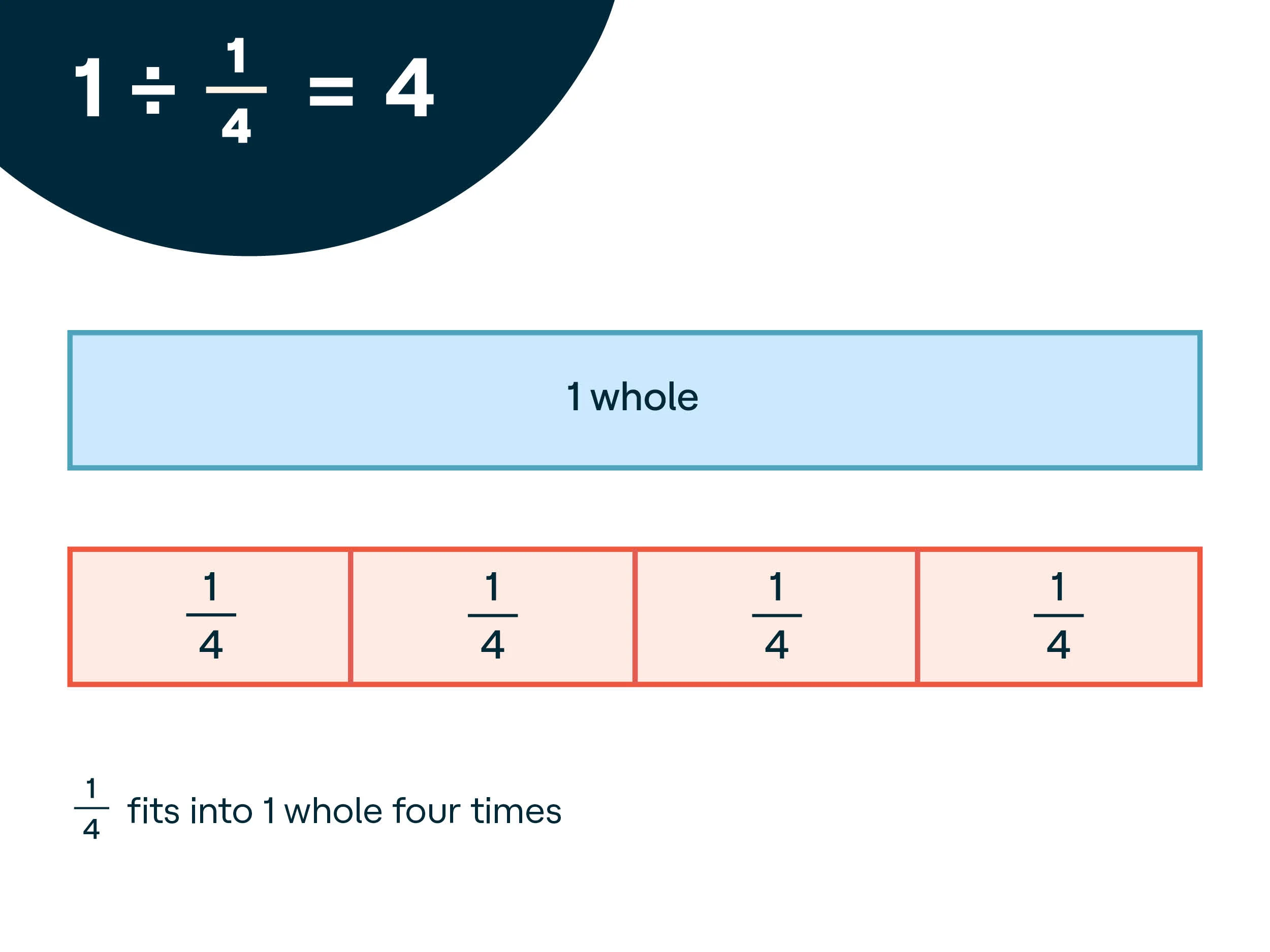

1. Review dividing a whole number by a fraction. Ask students to place the 1 whole strip at the top of their desk. Beneath that strip, have students place as many 1/4 strips as needed to match the same size as 1 whole. Write the equation 1 ÷ 1/4 = 4 on the board and ask the students how they know this is true. Students should refer to the strips in front of them to explain the answer.

Review all the common ways students could explain their answers by providing the following examples both visually and verbally:

“1/4 fits into 1 whole 4 times”

“There are 4 groups of 1/4 in 1 whole”

“1 divided into groups of 1/4 is 4”

“4 times 1/4 equals 1”

2. Explain how to use fraction strips to divide a fraction by a fraction. Use the “I Do, We Do, You Do” model (also known as a gradual release model of instruction) to guide students through the process of using the strips.

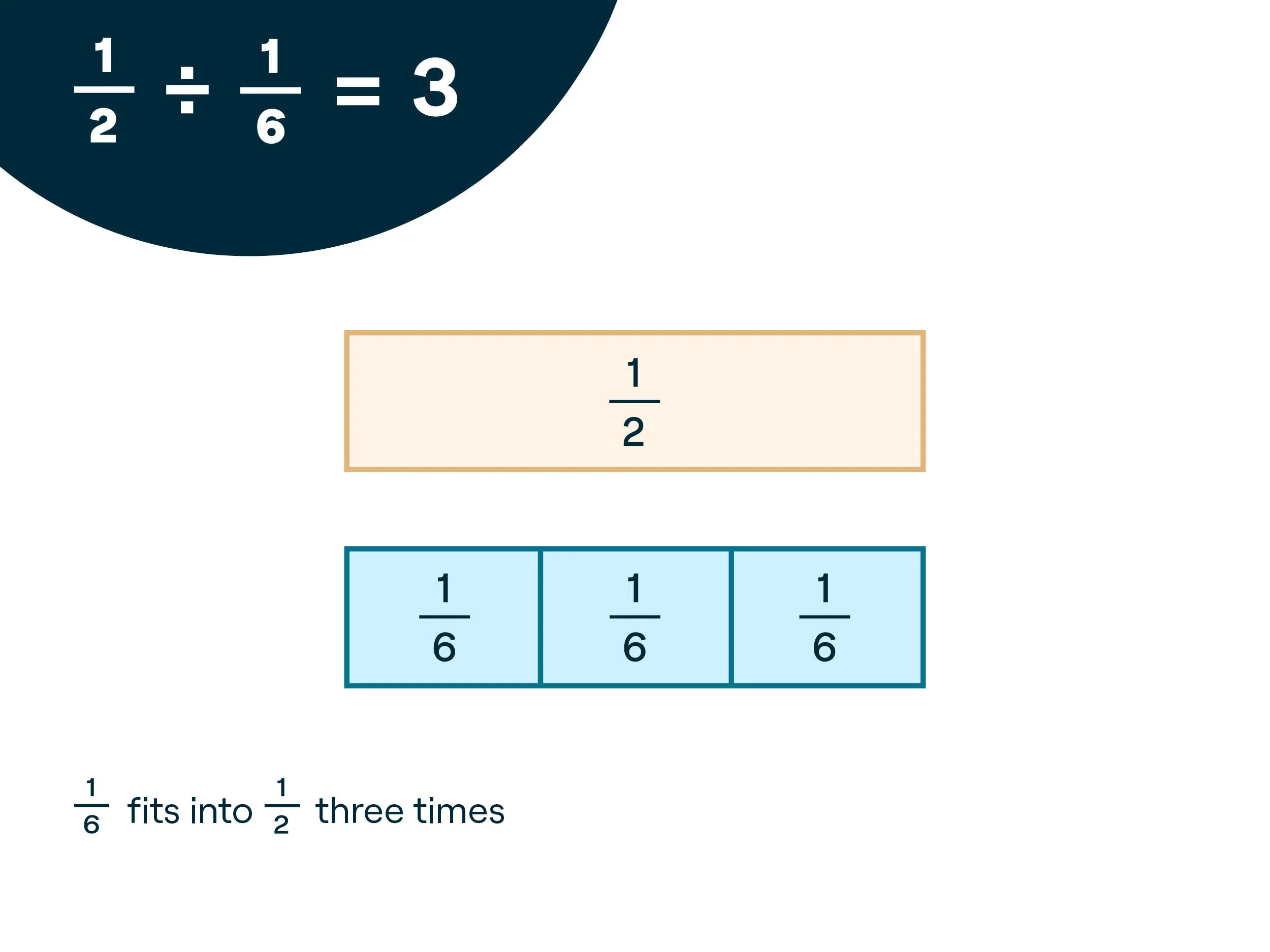

I Do: Explain and model using the strips. Say, “Now we can use a similar strategy to solve division problems with two fractions in them. Let’s take a look at 1/2 ÷ 1/6. I’ll start by placing a 1/2 strip at the top like this. Next, underneath it, I’ll put as many 1/6 strips as I can to match the 1/2 strip. We can see that it takes one, two, three 1/6 strips to match the 1/2 strip. So I can conclude that 1/2 ÷ 1/6 = 3, or 1/6 fits into 1/2 three times.”

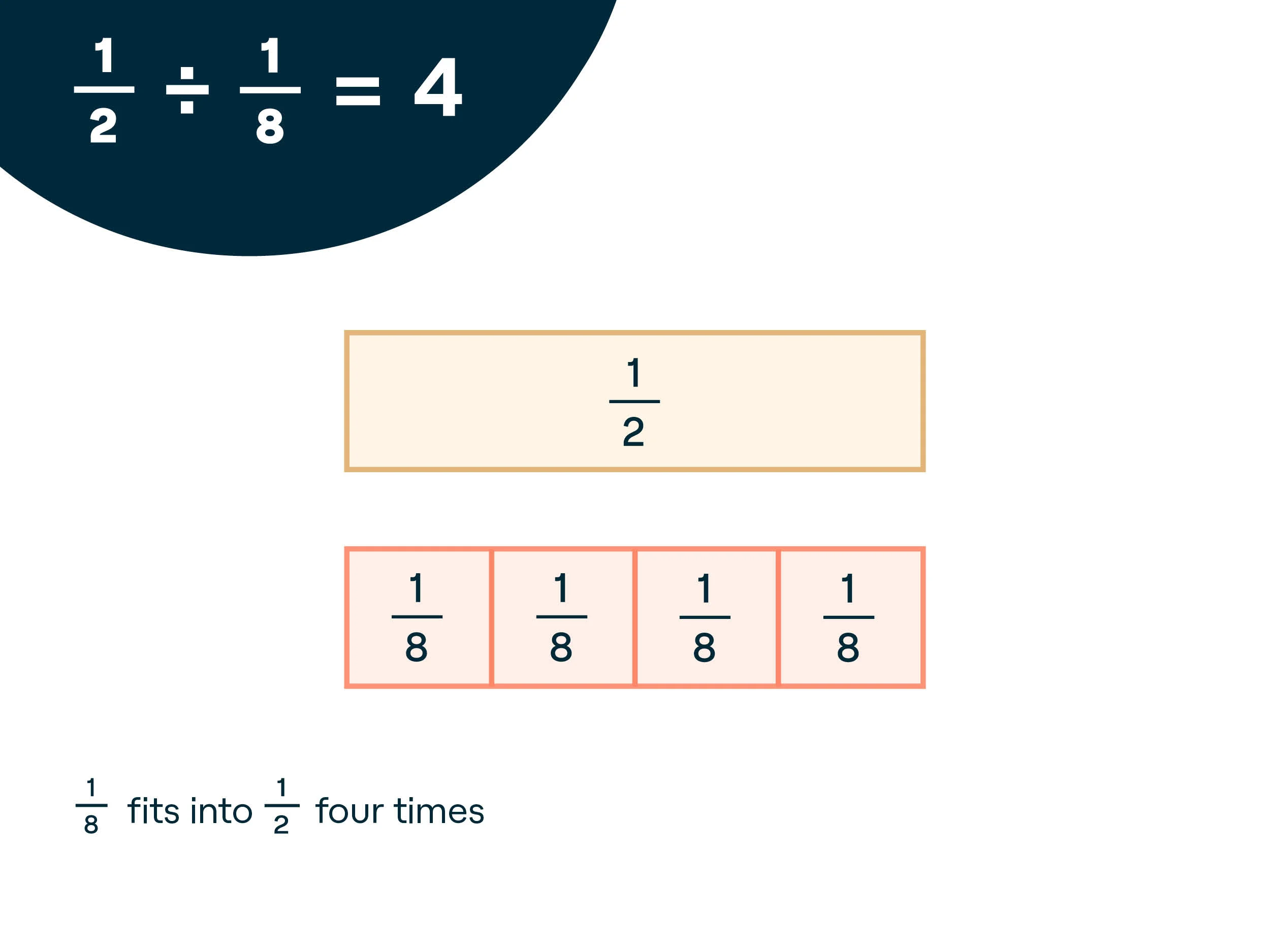

We Do: Guide students through trying it with you. Say, “Now let’s try this together. Start with 1/2 again. I will place 1/2 at the top. You do the same.” Model placing the 1/2 strip at the top. “This time divide 1/2 by 1/8. Let’s place as many 1/8 strips as we can to match the 1/2 strip.” Model it and then walk around to help students who may need support. For students who are able to set it up correctly, prompt them to write out the division problem with the solution.

Once everyone has finished, discuss the answer as a class. Write the division number sentence for students who may not have gotten the correct answer. Describe the solution in multiple ways.

You Do: Choose three division problems using unit fractions for both the divisor and the dividend. Tell students they’ll be doing them on their own. Say, ”Try the next several problems by yourself or with your partner. Be sure to write the division sentence with your solution once you have set it up using your fractions strips.” Provide guidance as needed. When checking in, ask students to explain their solutions using the language discussed at the beginning of class, such as “____ groups of ____ fit into ____.”

Teaching tip: Many students, including English language learners (ELLs) and students who struggle with expressive language, benefit from having sentence frames at their desks. Print out a set of frames and put them in dry-erase pockets so students can write out their answers each time.

3. Move on to practicing more challenging problems. Follow the “I Do, We Do, You Do” model again.

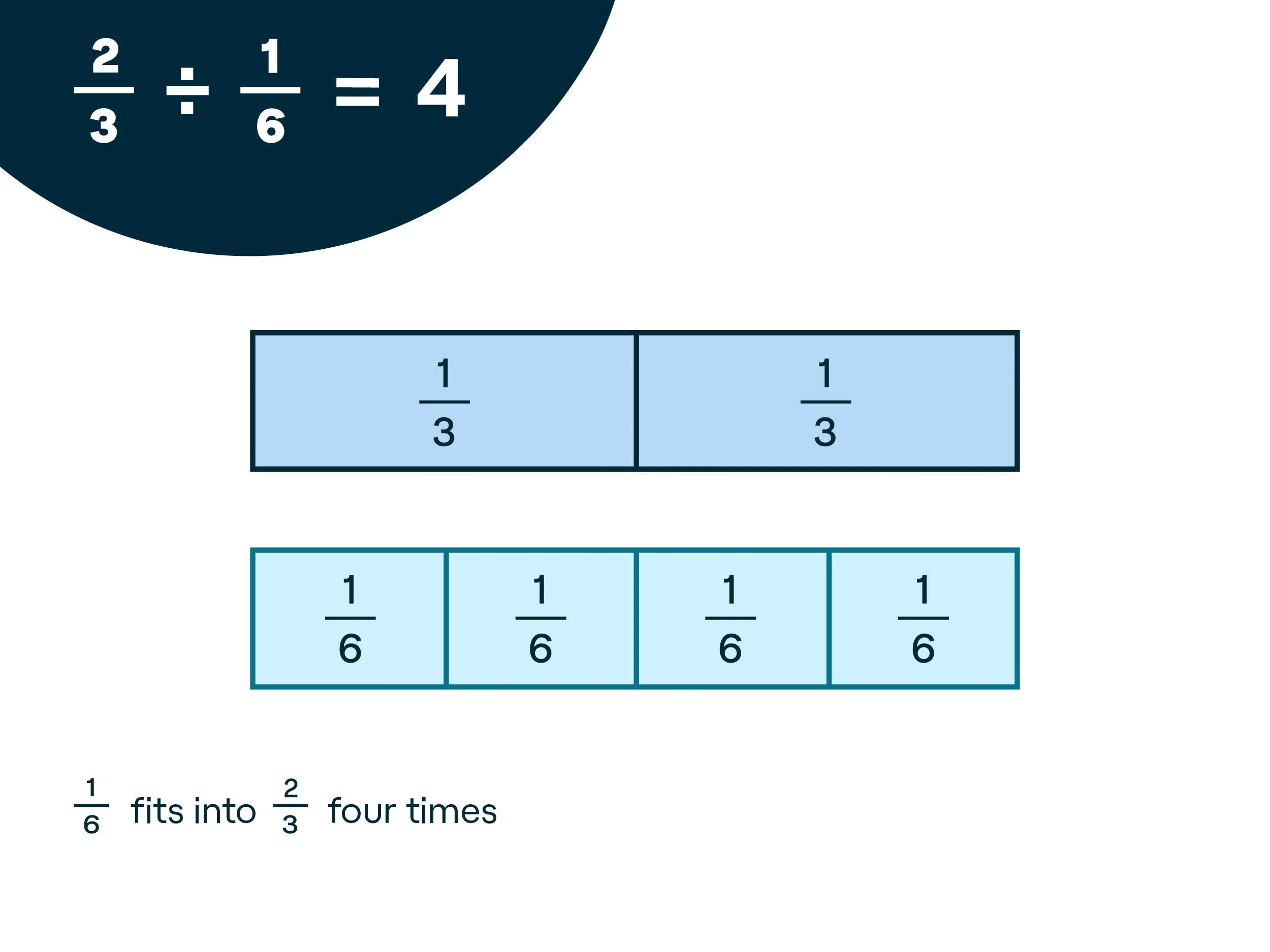

I Do: Say, “Let’s try some problems that are a little more challenging. This time begin with 2/3.” Model for them. Students should follow by placing two 1/3 strips at the top of their desk. “I want you to divide 2/3 by 1/6.” Demonstrate how to line up 1/6 strips below 2/3 until you have matched the whole. Count the number of strips you used out loud while pointing them out. “So, 2/3 ÷ 1/6 = 4.”

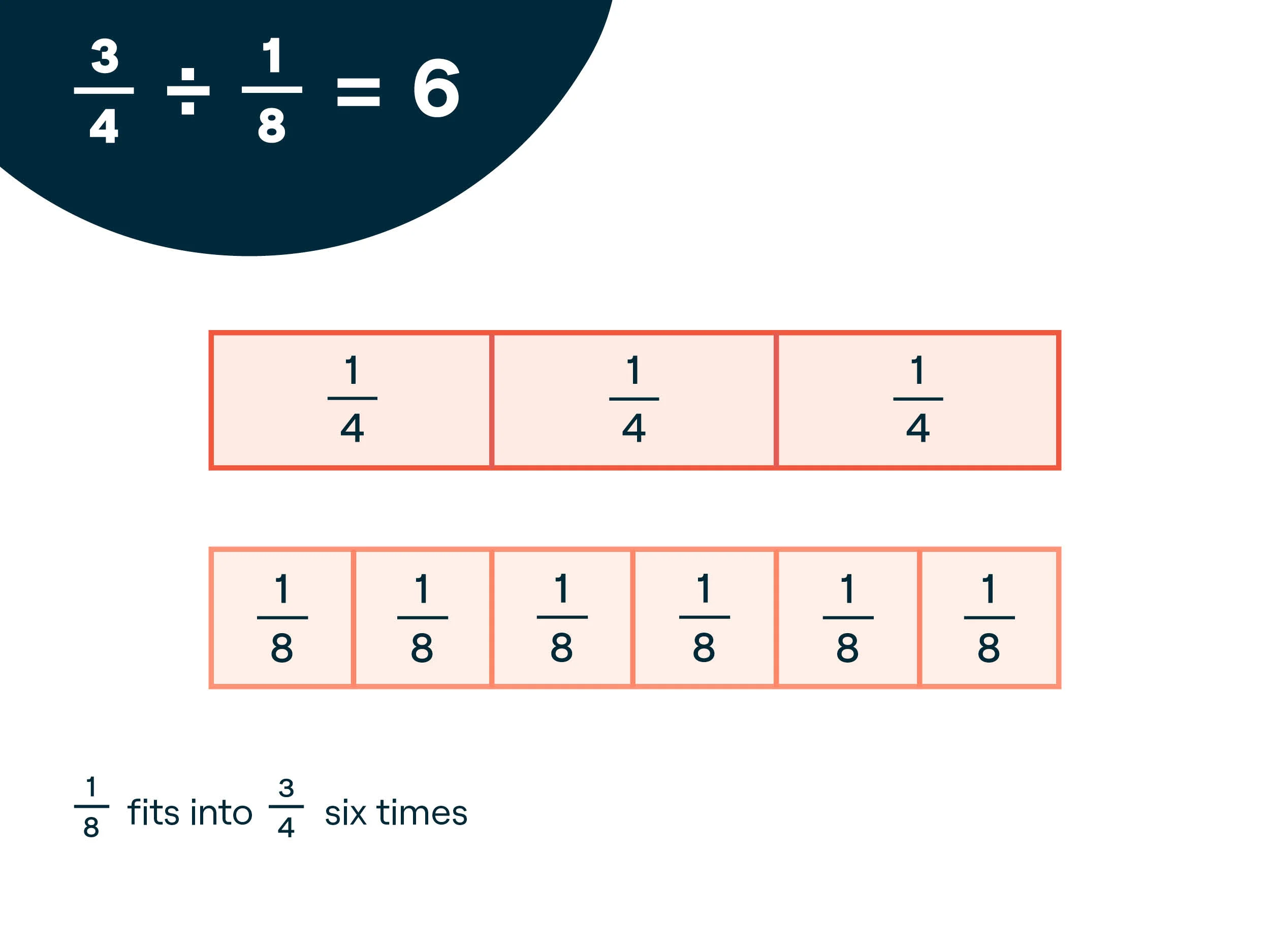

We Do: “Now, let’s do this next one together. Let’s try 3/4 ÷ 1/8. I’m going to show 3/4 at the top using three 1/4 strips. You do the same.” Model placing the 3/4 at the top. “This time, divide 3/4 by 1/8. Let’s place as many 1/8 strips as we can to match the 3/4 strip.” Model it and then walk around to help students who may need support. For students who are able to set it up correctly, prompt them to write out the division problem with the solution.

You Do: Provide several practice problems for students to try independently. Check in to see how students are using the fraction strips. Some students by this point may have figured out how to solve the problems without using the strips. Talk with these students about what procedure they are using. If you feel the class is ready at the end of the lesson, have these students demonstrate the keep-change-flip algorithm. This will help begin the transition to using the algorithm over the fraction strips.

4. Continue to practice. Some students may begin to solve without the fraction strips. Others will continue to use them. As everyone practices, challenge the students who are using the strips to draw models for each division problem instead. They can refer back to the strips as a reference, but drawing their own versions of the strips will help transition from the concrete of strips to the abstract of numbers .

Fraction strips (or fraction bars or tiles) help students see that the same “whole” can be broken up into different equal-size parts. When students move the strips and put them side by side, they can visualize the fractional amounts. They can also make comparisons between fractions and do addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division with fractions.

Students who experience difficulty with math, particularly with fractions, often have trouble connecting meaning to the numbers and symbols in an algorithm. Fraction strips give students a conceptual representation of the problem. They can use the strips to create both the dividend and the divisor so that they can see both as fractional parts of a whole. Students can also count the number of groups (the quotient) made by dividing.

With this strategy, you use explicit instruction in the “I Do, We Do, You Do” model. By showing students how to use the fraction strips and then allowing them to practice with both teacher and peer support, this strategy provides multiple learning opportunities.

Using this strategy before moving on to divisors that are not unit fractions will help students have a better understanding of why the algorithm works, not just how it works.

Once students are familiar with how to use the fraction strips, send a new fraction strip page home or a set that has already been cut out. Families can help reinforce using fraction strips at home when students are working on their homework.

If you find families are confused by the homework, consider sending this resource to help parents and caregivers understand why math is taught differently now than when they were in school.

“The concrete-representational-abstract approach for students with learning disabilities: An evidence-based practice synthesis,” from Remedial and Special Education

“Explicit mathematics instruction: What teachers can do for teaching students with mathematics difficulties,” from Intervention in School and Clinic

Explore related topics

Strip Diagrams: Visualizing Math

What is a strip diagrams in math.

A strip diagram, sometimes known as a bar model, length model or fraction strip, is a kind of visual model used when teaching math in order to demonstrate numerical relationships and help students solve various numbers and problems a little more easily.

A strip diagram is essentially a rectangular bar or box that can be divided up in different ways to represent known and unknown quantities.

The overall idea is that with a drawing or picture students can better visualize a problem and then decide what operation they should use to get the answer.

How Are They Used In Math Lessons?

Strip diagrams are actually pretty flexible visual tools that can be used when learning different topics and when confronted by different types of word problems.

Typically, strip diagrams are used as a tool to help students visualize problems and what operations they’re being asked to do (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division), something that can be particularly helpful with word problems.

The overarching principle is that, by drawing out a model, students learn to pick out the different variables given in a word problem, what they need to find and can then figure out what operation and methods they need to use to solve the problem in question.

Different types of strip diagram strategies

In general, there are a few different ways that parents and teachers use strip diagrams to solve different math problems.

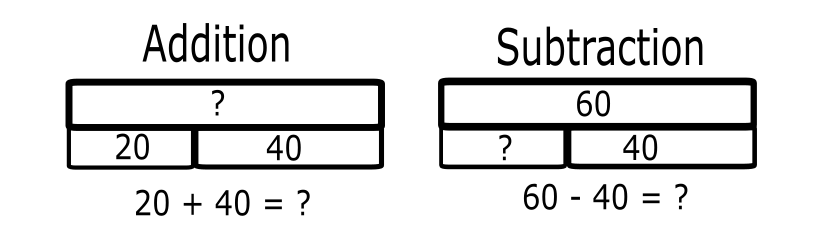

Part-Part Whole/Equal parts of a whole

Generally speaking, the first strip diagram most students will learn is the part-part whole model.

In essence, a large rectangle is placed at the top, representing a whole amount.

Below it, a same-sized rectangle is divided up into two or more pieces, representing the different parts that can make up that whole.

Depending on the problem, these can be uneven in size (representing two different numbers – such as in an addition or subtraction) or equal in size.

A bar might even be broken down into several, separate parts, as might be found in multiplication and division.

Students are given some information but quickly realize they are going to find and fill in the missing pieces.

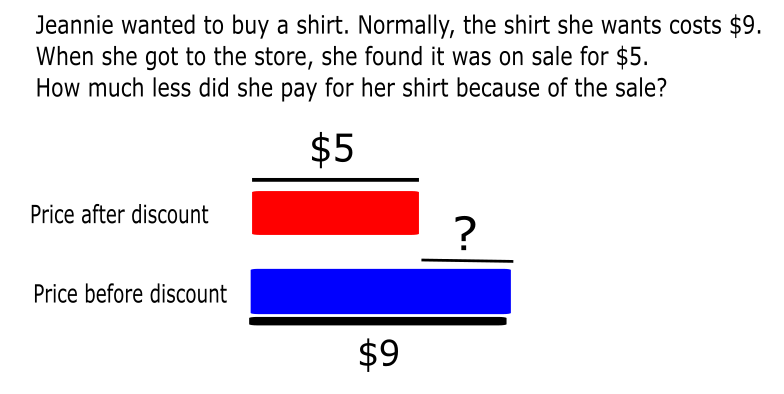

Comparison strip diagram

Compariston strip diagrams are, much as the name would imply, an intuitive and visual way of approaching problems where there is a difference in amounts and when there is a known/unknown component.

They can be ideal, for example, when approaching problems that ask the student things like:

- How much more than

- How many more

- How many fewer

- Larger than

- Smaller than

Much like Part-Part Whole models, comparison strip diagrams have two bars arranged one on top of the other so that students can immediately grasp the difference in length between the two, with brackets pointing out relevant numbers and totals.

The idea here is that these very visual bars can be an easy starting point for understanding differences in amounts.

More than that, however, we find that they can make understanding and breaking down comparison word problems a little easier for students, especially given the wide variation in vocabulary and terms that these problems can use (taller than, wider than, bigger than, as many as, as few as, fewer than, greater than, more expensive than, etc.).

Using strip diagrams for more complex problems

One common misconception is that strip diagrams are only used for basic operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

The reality is they are quite flexible and can be used well into more advanced math and for more complex and tricky word problems that often throw students.

For example, strip diagrams can be used to illustrate and work out ratio problems, such as below.

How To Set up A Strip Diagram Effectively

It’s important to keep in mind that strip diagrams are a tool and that a good homeschooling parent can’t be too rigid when it comes to its precise use and application.

It goes without saying that one needs to keep a student’s unique personality, understanding, abilities and skills in mind when doing any kind of problem solving.

That said, there are some steps that most programs will involve when teaching students to use a strip diagram. These tend to be:

- Read the question carefully and to completion.

- Highlight or circle any important information provided in the question, paying special attention to numbers and important words or phrases (more, together, as many).

- Who is the problem about/ what is the problem about

- What is known

- What information is missing

- Rereading the key phrase of the question (and paying special attention to any particular phrases – how many, what is the total, who/what is bigger, how much, etc ), decide what operation needs to be used to solve the problem.

- Draw and label the bars using the information collected

- Review the problem to make sure the bars make sense given the information presented

- Complete the calculation using the operation in order to work out the answer

Why Some Curricula Use Strip Diagrams

A systematic approach to confusing word problems.

Younger students often struggle with word problems for a variety of reasons.

For one thing, word problems (unlike computational exercises) involve much more than math.

Rather than being presented with a straight forward math problem, students are suddenly faced with a paragraph of words and numbers.

From this jumble of words, they have to keep track of a lot of different information, figure out what’s important, determine what the question actually is (since it’s usually cloaked in specific math vocabulary) and, finally, they have to figure out what to do.

Strip diagrams can help by providing students with a ready and systematic method of approaching these problems.

In order to build a strip diagram, students need to parse out the important information, collecting information on:

- What the problem is about

- What information is given to me

As a student gets more practice in building strip diagrams, they can become more adept at highlighting key information, ignoring irrelevant information, and identifying key math terms as hints for what the operation is supposed to be about.

In addition, as they get more experience at drawing out these diagrams, they can get better at organizing and presenting that information in a meaningful and more organized way, something that’s helpful for students who have a hard time showing their work or communicating their thoughts succinctly or mathematically.

Visual approach to help younger students with abstract concepts

Another challenge word problems present is that they often challenge students to reason or think through problems abstractly.

Typically, below the age of 12 or so , students are far better at seeing the world in concrete terms than they are at understanding abstractions.

They think logically, sure, and they can understand symbols for the most part, but the way in which they tend to understand things best is by being able to directly observe it.

A word problem involving two trains speeding along the track between two cities, or age differences between several kids, or different sizes of different items, or different prices can all be very hard for kids to get their heads around.

Learning to build a strip diagram can help younger students by letting them see and work with a visual (and concrete) representation of the question’s information rather than just relying on the written word.

A gentler introduction to algebraic thinking

Yet, it’s important to note that despite being visual, strip diagrams still remain somewhat symbolic and standardized, abstracted to a degree from the various topics and characters that pop up in a word problem.

Students are working with rectangles, after all, and aren’t being asked to literally draw out every problem.

As a result, they can still act to help kids get used to algebraic thinking, that is the ability to represent, generalize or reason through a problem using abstract math symbols and relationships.

There is strong evidence for their usefulness

Being something of a different way to tackle word problems than many educators (and parents) are used to, some have questioned whether using strip diagrams in approaching math problems has any real effect on success.

In recent years, studies have been run measuring how well strip diagrams can help students understand and solve math operations and word problems.

The findings from these have been quite positive. Studies have found, for example, using strip diagrams as a tool can be effective in helping elementary students answer word problems correctly, and there is some evidence that it can be an effective tool for remediation.

Pros and Cons of Using Strip Diagrams in your Homeschool Learning

It is important to remember that strip diagrams are just one of many tools that parents and students can use to solve word problems.

It is also important to note that, as a tool, strip diagrams can have their pros and cons and integrating their use into teaching isn’t always the best fit for every student.

Advantages of Strip Diagrams

Easy to learn for both parents and students.

Learning to use strip diagrams and weaving them into a problems solving approach isn’t really all that hard once you get the hang of it.

By and large, strip diagrams are really just a particular way of sketching out the key details of a question in a few different ways and can be pretty intuitive for both parents and students to learn and use.

Easy to understand, visual representation of word problem information

As mentioned previously, creating a strip diagram provides students with a pictorial representation that they can use to better understand what they’re being asked to do.

Seeing the size difference between two or more squares can be a lot easier to deal with for students than a paragraph involving trains, planes, clothing, chocolates, people, heights, sizes and more.

Encourages students to break apart and analyze word problems systematically

In order to set up a strip diagram properly, students have to learn to read a sentence, identify key elements, identify what is missing and understand certain important key phrases.

As a result, practicing strip diagrams can help students learn to approach word problems (and lay out their results) in a more organized and logical manner.

Easy to integrate with manipulatives and hands-on learning objects

Strip diagrams lend themselves quite easily and naturally to hands-on math learning approaches.

Strips can be constructed using blocks, pennies, sticks or whatever else might be handy, turning learning into a multisensory activity that can better suit tactile learners.

Disadvantages

Not every student needs to use strip diagrams (or wants it).

Although a useful tool, strip diagrams aren’t a tool that every student needs or prefers to use.

Some students “get” word problems very easily, being able to almost intuitively pick out key information and have no problem thinking about and representing them using equations and symbols.

Other students are more procedural in nature and don’t much care for the use of visuals and other models. Such students might prefer a more straightforward, by the numbers approach to solving word problems (i.e. memorizing a series of steps to follow) or may simply respond well to more practice and drill.

In either case, such students may find being forced to use strip diagrams frustrating.

In the case of more gifted math students they may even see the process as superfluous and something of a burden on them.

It can slow things down when solving problems

Strip diagrams do involve identifying and collecting information from a word problem, organizing it and drawing a model that makes some kind of sense in terms of scale.

Consequently, setting up and working with strip diagrams can take time, especially when students are still getting the hang of the process, which in turn can increase the length of a math lesson or practice session.

Not applicable to all word problems in math

While they tend to work well for most word problems involving operations and even algebra, creating strip diagrams doesn’t always make sense (or even really work) with all types of math problems.

Statistics and geometry, for example, can have interesting and challenging word problems associated with them but don’t necessarily lend themselves as subjects to strip diagrams and require their own models and algorithms to follow.

What Curricula Use Strip Diagrams And Other Easier Math Tools?

Strip diagrams, in particular, are most notably (although not exclusively) a characteristic of programs based on the Singapore approach to math and these programs tend to do a pretty good job at guiding parents and students through their use in a step-by-step manner.

The Singapore approach to math (so-called as it was originally developed as the main math curriculum for elementary school students in Singapore) is a conceptual math method that focuses on teaching students the why behind math and why it works the way it does, as well as to think critically and to solve math problems without relying excessively on memorization and drill.

In doing so, and by teaching for mastery, these programs tend to give students a deeper understanding of number relationships, strong math fluency and problem solving skills compared to more traditional programs.

The Singapore method or approach believes very strongly in what they call the Concrete-Pictorial-Abstract stages of learning, i.e. bringing a student gently from the concrete stage of understanding through a visual modeling stage and finally to a point where the student is comfortable using abstract symbols and equations.

Alongside number bonds, strip diagrams (which are more commonly referred to as bar models in these programs), tend to fit comfortably in the visual/pictorial stage of learning.

If this type of math program interests you or you have a student who you think would benefit from approaching math problems more visually, such as with strip diagrams, then we highly recommend the following programs.

Singapore Math

One of the most famous and widely used examples in the homeschool community of the Singapore approach, Singapore Math offers a thorough and rigorous math curriculum for students in K-8 that emphasizes hands-on learning and visual representation of math problems.

Offering a couple different editions (Primary Mathematics and Dimensions), Singapore Math’s visually-rich books encourage a deeper, critical thinking approach to math that has produced very strong and capable math students over the years

Read our in-depth review of Singapore Math

Read our in-depth review of their latest curriculum Primary Mathematics 2022 Edition

Math in Focus

Released in 2009, produced by Marshall Cavendish and published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Math in Focus is also based on the Singapore approach, teaches math similarly and also offers a rigorous and thorough math curriculum.

Singapore Math and Math in Focus are similar and the difference largely lies in the fact that Math in Focus is designed a bit more as a traditional school book, touches on a little more content and tends to have a little more built-in differentiation help.

Read our review of Math in Focus

Bottom Line:

A popular math model often associated with the Singapore approach, a strip diagram can be an excellent tool to help students more effectively deal with word problems.

While not always for every student, stripe diagrams can help students systematically analayze a complex word problem, better visualize what they are being asked to do and communicate their results in an organized manner.

And, for some students at least, that can make all the difference.

About the Author

David Belenky is a freelance writer, former science and math tutor and a tech enthusiast. When he’s not writing about educational tech, he likes to chill out with his family and dog at home.

Privacy Overview

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.

Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. It is mandatory to procure user consent prior to running these cookies on your website.

What is a Strip Diagram in Math? A Powerful Tool for Problem Solving

When it comes to solving math problems, having a clear visual representation can make all the difference. That’s where strip diagrams come in. In this

Feni Rutcher

February 25, 2024

When it comes to solving math problems, having a clear visual representation can make all the difference. That’s where strip diagrams come in. In this article, we will explore what strip diagrams are and how they can help students better understand and solve math problems. Whether you’re a student struggling with word problems or a teacher looking for a new teaching tool, strip diagrams could be the key to unlocking mathematical success.

Strip diagrams, also known as bar models or tape diagrams, are visual tools used in math to represent and solve problems. They provide a pictorial representation of the relationships between quantities in a problem, making it easier for students to comprehend complex mathematical concepts. By breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable parts, strip diagrams help students identify the necessary information and develop strategies to solve them.

Table of Contents

Understanding the Basics of Strip Diagrams

Strip diagrams are a valuable tool for students to develop a deeper understanding of math concepts. In this section, we will delve into the fundamental components of strip diagrams. We will explore how to create and interpret strip diagrams, including their different formats and uses.

Creating a Strip Diagram

Creating a strip diagram involves identifying the relevant quantities and representing them visually. Start by determining the main quantities involved in the problem. For example, if the problem involves two quantities, such as the number of apples and the number of oranges, draw two separate strips or bars to represent each quantity.

Next, label each strip with the corresponding quantity and any additional information that may be provided in the problem. For instance, if the problem states that there are 5 apples and 3 oranges, label one strip as “apples” and the other as “oranges.”

Finally, divide each strip into smaller segments to represent the specific values of each quantity. For example, if there are 5 apples, divide the “apples” strip into five equal segments. Similarly, if there are 3 oranges, divide the “oranges” strip into three equal segments.

Interpreting a Strip Diagram

Once you have created a strip diagram, it’s important to understand how to interpret it. Each segment of the strip diagram represents a specific quantity or value. By visually comparing the lengths of the segments, you can determine the relationships between the quantities in the problem.

For example, if the “apples” strip has three segments filled and the “oranges” strip has two segments filled, you can immediately see that there are more apples than oranges. This visual representation allows you to comprehend the relative quantities without relying solely on numerical values.

Applying Strip Diagrams to Addition and Subtraction Problems

Addition and subtraction problems can sometimes be challenging for students, especially when dealing with multiple quantities. In this section, we will showcase how strip diagrams can simplify these problems by visually representing the relationships between numbers. We will provide step-by-step examples to illustrate how to use strip diagrams effectively in solving addition and subtraction problems.

Using Strip Diagrams for Addition

Strip diagrams are particularly helpful when solving addition problems that involve two or more quantities. By visually representing the quantities involved, students can better understand the relationships between the numbers and the overall problem.

Let’s consider an example: John has 4 red marbles and 3 blue marbles. To find the total number of marbles, you can create a strip diagram with two sections, one for red marbles and one for blue marbles. Each section is divided into smaller segments to represent the specific quantities.

In this case, the “red marbles” section would have four filled segments, while the “blue marbles” section would have three filled segments. By counting the total number of filled segments, students can determine that John has a total of seven marbles.

Utilizing Strip Diagrams for Subtraction

Strip diagrams are equally useful when solving subtraction problems. They enable students to visualize the quantities involved and easily identify the relationships between numbers.

Let’s take an example: Sarah has 8 cookies, and she gives away 3 cookies to her friend. To determine how many cookies Sarah has left, you can create a strip diagram with two sections, one for the initial number of cookies and one for the cookies she gives away.

The “initial number of cookies” section would have eight filled segments, while the “cookies given away” section would have three filled segments. By subtracting the number of filled segments representing the cookies given away from the total number of filled segments, students can determine that Sarah has five cookies remaining.

Solving Multiplication and Division Problems with Strip Diagrams

Strip diagrams are not limited to addition and subtraction; they are equally powerful when applied to multiplication and division problems. This section will demonstrate how strip diagrams can help students better understand the concepts of multiplication and division. Through practical examples, we will guide you on how to create strip diagrams for these types of problems.

Using Strip Diagrams for Multiplication

Multiplication problems often involve finding the product of two or more quantities. Strip diagrams can provide a visual representation of the relationships between these quantities, making it easier for students to grasp the concept.

Let’s consider an example: Mary has 4 bags, and each bag contains 5 apples. To find the total number of apples, you can create a strip diagram with four sections, each representing a bag, and divide each section into smaller segments to represent the apples.

In this case, each “bag” section would have four filled segments, and each “apples” segment within each bag section would have five filled segments. By counting the total number of filled segments, students can determine that there are 20 apples in total.

Utilizing Strip Diagrams for Division

Division problems involve dividing a quantity into equal parts. Strip diagrams can help students visualize the division process and understand the relationships between the quantities involved.

Let’s take an example: There are 15 candies, and they need to be distributed equally among 3 friends. To represent this situation using a strip diagram, create a section for the total number of candies and divide it into smaller segments to represent the equal parts.

In this case, the “candies” section would have 15 filled segments, and by dividing these segments equally among the three friends, each friend would have five filled segments. By visually comparing the lengths of the segments, students can determine the equal distribution of candies.

Advanced Problem-Solving Techniques with Strip Diagrams

Once students have mastered the basics, strip diagrams can be taken to the next level to solve more complex math problems. In this section, we will explore advanced problem-solving techniques, such as ratio and proportion, using strip diagrams. By the end, you will have a comprehensive understanding of how strip diagrams can be applied to a wide range of mathematical scenarios.

Using Strip Diagrams for Ratios

Ratios compare the quantities of two or more objects or values. Strip diagrams can provide a visual representation of these ratios, making it easier for students to understand and solve problems involving ratios.

Consider an example: A recipe calls for a ratio of 2 cups of flour to 3 cups of sugar. To represent this ratio using a strip diagram, create two sections, one for flour and one for sugar. Divide each section into smaller segments to represent the cups.

In this case, the “flour” section would have two filled segments, and the “sugar” section would have three filled segments. By visually comparing the lengths of the segments, students can see the ratio of 2:3 between flour and sugar.

Utilizing Strip Diagrams for Proportions

Proportions involve comparing two ratios and determining if they are equivalent. Strip diagrams can help students visualize these proportions and better understand the relationships between the quantities involved.

Let’s take an example: A recipe calls for a ratio of 3 cups of flour to 4 cups of milk. Another recipe calls for a ratio of 6 cups of flour to 8 cups of milk. To determine if these ratios are equivalent, create strip diagrams for each ratio, with sections for flour and milk divided into smaller segments to represent the cups.

In the first strip diagram, the “flour” section would have three filled segments, and the “milk” section would have four filled segments. In the second strip diagram, the “flour” section would have six filled segments, and the “milk” section would have eight filled segments. By visually comparing the lengths of the segments in both strip diagrams, students can determine if the ratios are equivalent.

Strip Diagrams in Real-Life Situations

In this section, we will showcase how strip diagrams can be used to solve real-life problems. From calculating expenses to determining the best deal, strip diagrams provide a practical approach to applying math concepts in everyday situations. By incorporating real-life examples, we aim to demonstrate the versatility and relevance of strip diagrams beyond the classroom.

Using Strip Diagrams for Shopping

Strip diagrams can be helpful when comparing prices or determining the best deal while shopping. Let’s consider an example: You are at the supermarket and want to buy a box of cereal. There are two brands available, one priced at $4 for 250grams and another priced at $6 for 400 grams. To determine which brand offers a better value, create strip diagrams for each brand, with sections representing the price and the quantity of cereal.

In the strip diagram for the first brand, the “price” section would have four filled segments, and the “quantity” section would have 250 filled segments. In the strip diagram for the second brand, the “price” section would have six filled segments, and the “quantity” section would have 400 filled segments.

By visually comparing the lengths of the segments, students can determine that the second brand offers a better value for money, as the “quantity” section is longer for the same price compared to the first brand. Strip diagrams allow individuals to make informed decisions based on visual representations of quantities and prices.

Using Strip Diagrams for Budgeting

Strip diagrams can also be applied to budgeting situations. For example, let’s say you have a monthly income of $200 and need to allocate it among different expenses. Create a strip diagram with sections representing different expenses, such as rent, groceries, transportation, and entertainment.

Divide each section into smaller segments to represent the amount of money allocated to each expense. For instance, if you allocate $80 for rent, create four filled segments in the “rent” section. Repeat this process for the other expenses, allocating an appropriate amount of money to each category.

By visually comparing the lengths of the segments, you can easily see how your income is distributed among different expenses. Strip diagrams provide a clear representation of budget allocations, making it easier to manage finances and make adjustments if necessary.

Strip Diagrams as a Teaching Tool

Strip diagrams not only benefit students but also serve as a valuable teaching tool for educators. This section will explore how teachers can incorporate strip diagrams into their lesson plans to enhance students’ understanding of math. We will provide tips and strategies for effectively incorporating strip diagrams into the classroom, ensuring an engaging and interactive learning experience for students.

Incorporating Strip Diagrams into Math Lessons

Teachers can introduce strip diagrams to students as a problem-solving strategy for various math concepts. For instance, when teaching addition and subtraction, teachers can demonstrate how strip diagrams can help students visualize the relationships between quantities and solve word problems more effectively.

When introducing strip diagrams, teachers can start with simple examples and gradually increase the complexity as students become more comfortable with the concept. They can provide guided practice exercises and encourage students to work collaboratively, discussing their strategies and findings.

Teachers can also incorporate technology, such as interactive whiteboards or online tools, to create and manipulate strip diagrams. This can enhance student engagement and provide opportunities for interactive learning experiences.

Using Strip Diagrams for Cross-Curricular Connections

Strip diagrams can be used beyond the realm of mathematics and integrated into other subjects as well. For example, in science class, students can use strip diagrams to represent the relationships between different variables in experiments or data analysis.

In language arts, strip diagrams can be utilized to analyze and interpret information in graphs, charts, and other visual representations of data. Students can create strip diagrams to better understand the relationships between different elements in a story or a piece of literature.

By incorporating strip diagrams into various subjects, teachers can reinforce the concept and provide students with opportunities to apply their problem-solving skills in different contexts, fostering a holistic understanding of the tool.

Advantages and Limitations of Strip Diagrams

While strip diagrams offer numerous benefits, they also have their limitations. In this section, we will discuss the advantages and limitations of strip diagrams. By understanding their strengths and weaknesses, educators and students can make informed decisions about when and how to best utilize strip diagrams in their math problem-solving endeavors.

Advantages of Strip Diagrams

Strip diagrams offer several advantages in math problem-solving. They provide a visual representation that helps students grasp complex concepts and relationships between quantities. Strip diagrams break down problems into smaller, more manageable parts, making it easier for students to identify the necessary information and develop problem-solving strategies.

Additionally, strip diagrams can be used across different math topics and grade levels, making them a versatile tool for educators. They promote critical thinking and logical reasoning skills, as students need to analyze and interpret the visual representation of the problem.

Furthermore, strip diagrams can be particularly beneficial for students who struggle with language barriers or have difficulty understanding word problems. The visual representation allows these students to focus on the mathematical relationships rather than getting overwhelmed by the language used in the problem.

Limitations of Strip Diagrams

While strip diagrams are a valuable tool, they do have some limitations. One limitation is that strip diagrams may not be suitable for every math problem. They are most effective for problems that involve quantities or relationships that can be visually represented.

Strip diagrams may also be limited in their ability to represent more abstract math concepts or problems that require complex mathematical reasoning. In such cases, alternative problem-solving strategies may be more appropriate.

Another limitation is that strip diagrams may not provide a complete solution to a math problem. They are a valuable tool in the problem-solving process, but students must also be able to translate the visual representation into mathematical equations or calculations to arrive at a final answer.

Strip Diagrams and Common Core State Standards

Strip diagrams have gained popularity due to their alignment with the Common Core State Standards in math education. This section will explore how strip diagrams support and reinforce the concepts and skills outlined in the Common Core State Standards. By incorporating strip diagrams into instruction, students can meet the rigorous expectations set by these standards.

Alignment with Mathematical Practice Standards

Strip diagrams align with several Mathematical Practice Standards outlined in the Common Core State Standards. For example, strip diagrams promote the standard of “Model with Mathematics” by providing a visual representation that helps students make sense of problems and persevere in solving them.

Strip diagrams also support the standard of “Reason Abstractly and Quantitatively” by helping students understand the relationships between quantities and translate them into mathematical reasoning. They encourage students to use precise mathematical language when discussing and interpreting the strip diagram.

Furthermore, strip diagrams align with the standard of “Attend to Precision” by requiring students to carefully consider the lengths and proportions of the segments in the diagram. Students must attend to the details and accurately represent the given information in the strip diagram.

Reinforcing Content Standards

Strip diagrams reinforce several content standards in mathematics education. For example, they align with the standards of Operations and Algebraic Thinking, as they help students visualize and solve problems involving addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

Strip diagrams also support the standards of Ratios and Proportional Relationships by providing a visual representation of ratios and proportions. They help students understand the relationships between quantities and solve problems involving ratios, rates, and percentages.

Additionally, strip diagrams align with the standards of Measurement and Data, as they assist students in visualizing and interpreting data representations, such as graphs and charts. They help students analyze and compare different quantities in a meaningful way.

Enhancing Math Skills with Strip Diagrams: Practice Exercises

Practice makes perfect, and this section offers a collection of practice exercises to enhance math skills using strip diagrams. These interactive exercises will provide students with an opportunity to apply their knowledge and problem-solving techniques to various scenarios. By practicing with strip diagrams, students can build confidence and improve their ability to solve math problems effectively.

Practice Exercise 1: Addition and Subtraction

In this exercise, students will be presented with word problems that require them to use strip diagrams to solve addition and subtraction problems. They will create strip diagrams and use them to determine the total or difference between quantities.

Example: John has 5 baseball cards. He gives away 2 cards to his friend. How many cards does John have now?

Students can create a strip diagram with segments to represent the initial number of cards and the cards given away. By visually comparing the lengths of the segments, students can determine the answer.

Practice Exercise 2: Multiplication and Division

This exercise focuses on multiplication and division problems that can be solved using strip diagrams. Students will create strip diagrams to represent the quantities involved and use them to solve the problems.

Example: A box contains 6 bags of candies. Each bag has 8 candies. How many candies are there in total?

Students can create a strip diagram with sections for the bags and the candies. By visually comparing the lengths of the segments, students can determine the answer.

Practice Exercise 3: Ratios and Proportions

In this exercise, students will practice solving problems involving ratios and proportions using strip diagrams. They will create strip diagrams to represent the given ratios and use them to determine equivalent ratios or solve proportion problems.

Example: The ratio of boys to girls in a classroom is 3:5. If there are 24 boys in the classroom, how many girls are there?

Students can create a strip diagram with sections for boys and girls. By visually comparing the lengths of the segments and using the given information, students can determine the answer.

Strip diagrams are a powerful tool in math education, providing students with a visual representation thatenhances their problem-solving skills. By breaking down complex problems into manageable parts, strip diagrams enable students to see the relationships between quantities and develop effective strategies for solving them. Whether used as a teaching tool or a problem-solving technique, strip diagrams offer a versatile approach to tackling math problems.

Throughout this article, we have explored the basics of strip diagrams, including how to create and interpret them. We have seen how strip diagrams can be applied to addition and subtraction problems, as well as multiplication and division problems. Strip diagrams have proven to be effective in simplifying word problems and helping students visualize the relationships between numbers.

Furthermore, we have delved into advanced problem-solving techniques with strip diagrams, such as ratios and proportions. Strip diagrams provide a visual representation that aids in understanding these concepts and solving problems that involve them. By incorporating strip diagrams into real-life situations, such as shopping or budgeting, students can apply their math skills to practical scenarios.

Strip diagrams also serve as a valuable teaching tool for educators. By incorporating strip diagrams into math lessons, teachers can enhance students’ understanding of mathematical concepts and promote critical thinking skills. Strip diagrams can be used in various subjects, making cross-curricular connections and reinforcing the Common Core State Standards.

While strip diagrams offer numerous advantages, it is important to acknowledge their limitations. Strip diagrams may not be suitable for every math problem and may not provide a complete solution on their own. Students must be able to translate the visual representation into mathematical equations or calculations to arrive at a final answer.

In conclusion, strip diagrams are a powerful tool in math education that can greatly enhance students’ problem-solving skills. By providing a visual representation of quantities and relationships, strip diagrams enable students to comprehend complex math concepts and develop effective strategies for solving problems. Whether used as a teaching tool or a problem-solving technique, strip diagrams offer a versatile approach to tackling math problems and promoting a deeper understanding of mathematical concepts. By incorporating strip diagrams into instruction and practice exercises, students can build confidence and excel in their math skills. So, embrace the power of strip diagrams and unlock the potential of math problem-solving.

Related Post

Boost your math skills with word search math terms answers.

March 3, 2024

Why Was Math Book Sad? Unraveling the Mystery Behind the Tears

March 2, 2024

Why is Bacteria Bad at Math? Unraveling the Mysteries of Microbial Numerical Ineptitude

March 1, 2024

Why Did the Math Teacher Open a Window Company? Answer Revealed!

February 29, 2024

Why Did the Math Book Look So Sad? Unraveling the Mystery

February 28, 2024

When Will Summerfest Start in Prodigy Math Game 2023: Get Ready for the Ultimate Math Adventure!

February 27, 2024

Unlocking the Secrets: What is the Focus of the Aspire Math Test?

February 26, 2024

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

How to Remove a TV from a Wall Mount: A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Pronounce Clothes: A Complete Guide to Perfect Pronunciation

How to Make Hot Cheeto Mozzarella Sticks: A Fiery Twist on a Classic Snack

How to Remove Moisture from Car Headlight Without Opening: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Open Carry in a Car: A Comprehensive Guide for Responsible Gun Owners

Popular Post

Recover from Binge Eating Disorder: A Step-by-Step Guide to a Healthy Relationship with Food

How to Move a Couch by Yourself: The Ultimate Guide for Easy and Safe Couch Transportation

Protect Your Car: How to Keep Birds from Pooping on Your Car

How to Make a Cup: The Ultimate Guide to Crafting Your Own Personalized Drinkware

How to Prevent BPPV from Recurring: Effective Strategies to Maintain Balance

[email protected]

Quick Links

Privacy policy

Tape Diagrams in Math: A Problem Solving Strategy

What is your go-to strategy for teaching word problems? I have always encouraged my students to model, model, model when solving word problems. Modeling is a way for students to make sense of a problem and catch mistakes before they happen. Sometimes, what seems like a good answer just doesn't work out once it's drawn as a model.

Until recently, I really didn't care what kind of model my kids used. Drawings, tally marks, symbols: anything was fair game. But as we've worked our way through multiplication and into division, I've found myself returning over and over again to the tape diagram. It's a nearly fail-proof way to work through a story problem and my students have become problem solving masters!

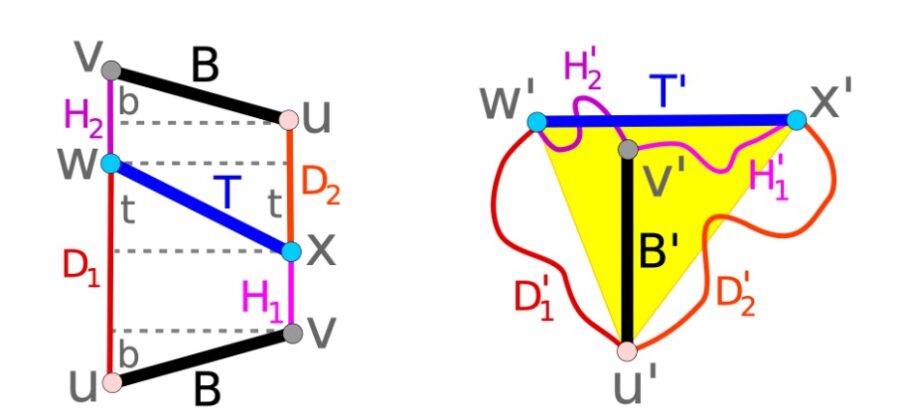

So, what exactly is a tape diagram?

A tape diagram is a drawing that looks like a segment of tape, used to illustrate number relationships. Also known as a strip diagram, bar model, fraction strip, or length model."

In practice, a tape diagram in math looks like this...

Tape diagrams have become my go-to model when teaching math. They work for any type of word problem, but I especially love them for solving multiplication and division.

how do you solve a tape diagram?

To solve problems using tape diagrams, students must first ask, "Do I know the whole amount?" If it's supplied by the problem, fill it in. If not, put a question mark at the bottom of the diagram. Then look for other information and fill that in. The question mark always represents whatever piece of information is missing.

Here is an example of how I use it to teach division problems:

Students will quickly begin to see a pattern... the bottom number is always the product of the top two numbers.

Therein lies the beauty of this model:

It is self-correcting. If the top two numbers, when multiplied, do not equal the bottom, you've done something wrong.

When teaching with this model, it's a good idea to have students write all four possible equations. So in the above example, we would also write ? x 4 = 32 and 32 ÷ ? = 4. This is important because it reinforces the concept of inverse operations and fact families. It also gives students a tool to use when the encounter problems with a missing factor or divisor.

Once my students are able to interpret story problems and solve using tape diagrams, I teach them to analyze a tape diagram and write their own story problems to go with it. This requires high-order thinking and really develops their mathematical minds.

how to use tape diagrams

To use tape diagrams with your students, I suggest following this instructional sequence...

Teacher supplies the story problem, draws the tape diagram, and models how to solve.

Teacher supplies the story problem, draws the tape diagram, and students help solve.

Teacher supplies the story problem, students help draw the diagram, and students solve on their own.

Teacher supplies the story problem, students draw and solve alone.

Teacher draws a tape diagram and students create a story problem to go with it.

Along the way, you'll want to move from including one equation that represents the problem to showing all four possible equations. This process, from introduction to proficiency, might take several weeks depending on the skills of your students. But it will pay off in the long run when your students become experts at solving word problems !

If you're interested in teaching your students to use this strategy, you may want to check out this resource:

Problem Solving with Tape Diagrams: A Model for Multiplication and Division

Related Posts

5 Great Reasons to Use Games in the Classroom

Keywords for Math Word Problems: A Bad Strategy?

How to Teach 3rd Grade Division: The Best Way to Build Division Skills

Strip Diagram Questions

FREE DOWNLOAD

20 word problems that can be solved using strip diagrams.

- 20 mixed topic word problems with a strip diagram template.

- Word problems include questions on number and operations in base ten, measurement and data and operations and algebraic thinking.

- Answer key includes completed strip diagrams.

Unlock access to download your free resource

To receive this printable resource and regular emails with more free resources, blog posts and other Third Space updates, enter your email address and click below.

- Job Title * Job title Principal Assistant Principal Head of School Superintendent Assistant Superintendent Curriculum Director Curriculum Coordinator Interventionist Instructional Coach Instructional Technology Specialist Title 1 Coordinator Math Coach Elementary Teacher Middle School Math Teacher High School Math Teacher Other Teacher Aide or Paraprofessional Teaching Assistant Tutor Parent Student Other

This service is not currently available for students

- State * State Alabama Alaska American Samoa Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Guam Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Northern Mariana Islands Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Puerto Rico Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Texas Utah U.S. Virgin Islands Vermont Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Armed Forces Americas Armed Forces Europe Armed Forces Pacific

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

You can unsubscribe at any time (each email we send will contain an easy way to unsubscribe). To find out more about how we use your data, see our privacy policy .

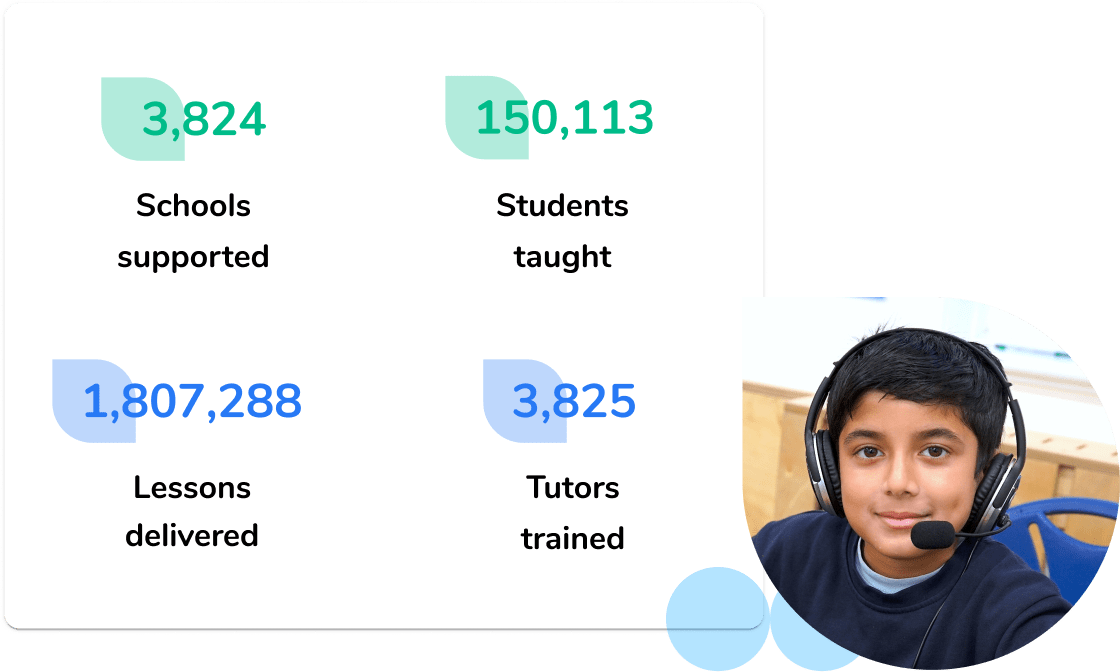

Accelerate math learning across your school with flexible and easy to use math resources designed by teachers for teachers.

Personalized one-on-one math instruction made easy

At Third Space Learning, we’re on a mission to help teachers like you shape your students into confident, able mathematicians.

Request a demo

Privacy Overview

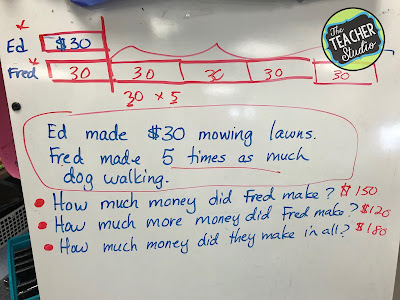

Comparison Problems with Tape Diagrams/Strip Diagrams

Comparison problems: using tape diagrams to represent math thinking.

Word problems are a key part of rigorous standards everywhere, but teachers and students alike often dread tackling them. Even textbooks sometimes save them for the bottom few problems on a page or a separate lesson toward the end of a chapter. The thing is–word problems (at least good ones!) are the “real world” part of math. One type of word problems, comparison problems, can be particularly challenging for students. Let’s look at some teaching tips that might make them more accessible!

Critical Reading of Math Problems

As educators, we should always be striving to help our students understand that the skills we are teaching are them are FOREVER…not just to complete a math page or worksheet. One skill that we really want to make sure our students understand is the need to critically read math problems to figure out what is being asked, what information is given, and to make a plan for solving. So often we do the thinking and hard work for our students.

For example, just consider how many of our math books are organized. A lesson entitled “Solving Addition Stories” doesn’t leave much room for student thinking, does it? It seems pretty clear what operation students will need to choose! Providing students with a constantly spiraling variety of problems forces them to think for themselves, learn to look for key information in problems, and make solution decisions accordingly.

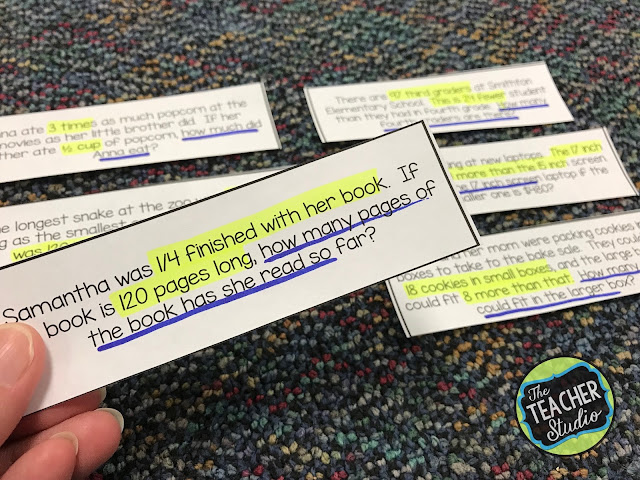

One idea? Use highlighters to find and notate important information. Underline or circle the question. One thing I do NOT recommend? Looking for key words like “fewer” or “total”. These words may seem like a quick fix for students…but they can lead them down the wrong path. How? How about this problem…

“Larry has 14 baseball cards. This is 25 fewer than his sister Kara has. How many cards does Kara have?”

Visualization and Modeling with Comparison Problems

One strategy that can really help students make sense of problems is to be able to visualize and draw models of different problem types. Comparison problems–sometimes represented with “tape” or “strip” diagrams are a GREAT way to help students visualize the math! I thought I’d share a few ways that these can be super helpful for students–whether used as whole class lessons or for intervention groups.

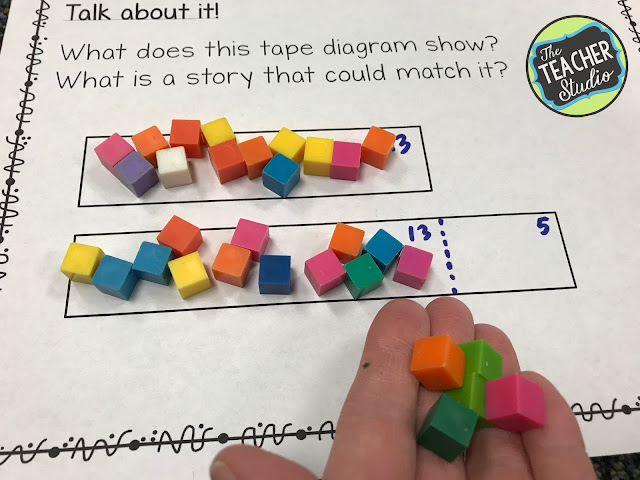

Using a blank “template” or outline of a tape diagram with manipulatives can really help students see the comparison that appears in a problem. The photo below showcases a visual representation of the following problem:

Next Steps with Comparison Problems

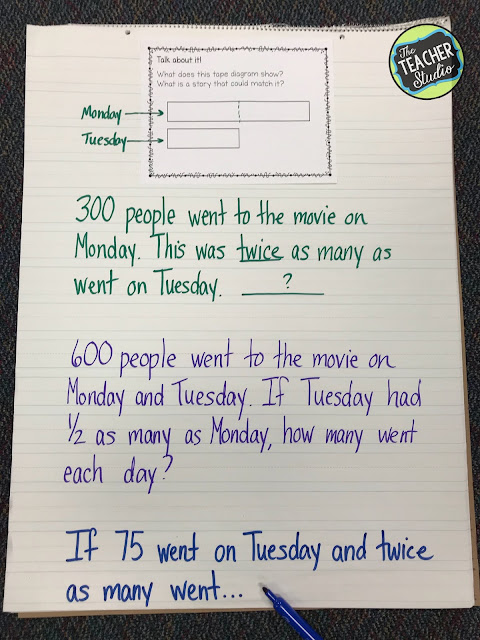

Another strategy to get students really visualizing is to take a blank diagram and create different stories to go along with them. This is a fantastic way to help students get flexible with their thinking. I start with modeling some problems and then have students progress to writing and sharing their own. It truly helps them understand the problems at a deeper level.

Hope you found this information valuable! These problems don’t HAVE to be as challenging if we help students bridge the gap between the problem and a meaningful strategy to solve them!

Looking to try some of these on your own?

SHARE THIS POST:

5 Effective Math Games for Back to School

Infusing Creativity in the Classroom: The Teacher’s Role

The Importance of Teaching Geography in Elementary School

Quick Links

- The Teacher Studio 2024

- Site Design By Laine Sutherland Designs

Paper Strip

- + ACCUPLACER Mathematics

- + ACT Mathematics

- + AFOQT Mathematics

- + ALEKS Tests

- + ASVAB Mathematics

- + ATI TEAS Math Tests

- + Common Core Math

- + DAT Math Tests

- + FSA Tests

- + FTCE Math

- + GED Mathematics

- + Georgia Milestones Assessment

- + GRE Quantitative Reasoning

- + HiSET Math Exam

- + HSPT Math

- + ISEE Mathematics

- + PARCC Tests

- + Praxis Math

- + PSAT Math Tests

- + PSSA Tests

- + SAT Math Tests

- + SBAC Tests

- + SIFT Math

- + SSAT Math Tests

- + STAAR Tests

- + TABE Tests

- + TASC Math

- + TSI Mathematics

- + ACT Math Worksheets

- + Accuplacer Math Worksheets

- + AFOQT Math Worksheets

- + ALEKS Math Worksheets

- + ASVAB Math Worksheets

- + ATI TEAS 6 Math Worksheets

- + FTCE General Math Worksheets

- + GED Math Worksheets

- + 3rd Grade Mathematics Worksheets

- + 4th Grade Mathematics Worksheets

- + 5th Grade Mathematics Worksheets

- + 6th Grade Math Worksheets

- + 7th Grade Mathematics Worksheets

- + 8th Grade Mathematics Worksheets

- + 9th Grade Math Worksheets

- + HiSET Math Worksheets

- + HSPT Math Worksheets

- + ISEE Middle-Level Math Worksheets

- + PERT Math Worksheets

- + Praxis Math Worksheets

- + PSAT Math Worksheets

- + SAT Math Worksheets

- + SIFT Math Worksheets

- + SSAT Middle Level Math Worksheets

- + 7th Grade STAAR Math Worksheets

- + 8th Grade STAAR Math Worksheets

- + THEA Math Worksheets

- + TABE Math Worksheets

- + TASC Math Worksheets

- + TSI Math Worksheets

- + AFOQT Math Course

- + ALEKS Math Course

- + ASVAB Math Course

- + ATI TEAS 6 Math Course

- + CHSPE Math Course

- + FTCE General Knowledge Course

- + GED Math Course

- + HiSET Math Course

- + HSPT Math Course