Health literacy and tuberculosis control: systematic review and meta-analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi, India.

- 2 Country Office for India, World Health Organization, New Delhi, India.

- 3 Indian Council of Medical Research, Regional Medical Research Centre, Chandrasekharpur, Bhubaneswar, Odisha751023, India.

- 4 WHO National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme Technical Support Network, New Delhi, India.

- 5 Department of Psychiatry, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, India.

- PMID: 38812804

- PMCID: PMC11132163

- DOI: 10.2471/BLT.23.290396

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice

- Health Literacy*

- Medication Adherence

- Tuberculosis* / drug therapy

- Tuberculosis* / prevention & control

Grants and funding

- 001/WHO_/World Health Organization/International

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Functional connectivity changes in the brain of adolescents with internet addiction: A systematic literature review of imaging studies

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Department of Brain Sciences, Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Behavioural Brain Sciences Unit, Population Policy Practice Programme, Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- Max L. Y. Chang,

- Irene O. Lee

- Published: June 4, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Internet usage has seen a stark global rise over the last few decades, particularly among adolescents and young people, who have also been diagnosed increasingly with internet addiction (IA). IA impacts several neural networks that influence an adolescent’s behaviour and development. This article issued a literature review on the resting-state and task-based functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies to inspect the consequences of IA on the functional connectivity (FC) in the adolescent brain and its subsequent effects on their behaviour and development. A systematic search was conducted from two databases, PubMed and PsycINFO, to select eligible articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligibility criteria was especially stringent regarding the adolescent age range (10–19) and formal diagnosis of IA. Bias and quality of individual studies were evaluated. The fMRI results from 12 articles demonstrated that the effects of IA were seen throughout multiple neural networks: a mix of increases/decreases in FC in the default mode network; an overall decrease in FC in the executive control network; and no clear increase or decrease in FC within the salience network and reward pathway. The FC changes led to addictive behaviour and tendencies in adolescents. The subsequent behavioural changes are associated with the mechanisms relating to the areas of cognitive control, reward valuation, motor coordination, and the developing adolescent brain. Our results presented the FC alterations in numerous brain regions of adolescents with IA leading to the behavioural and developmental changes. Research on this topic had a low frequency with adolescent samples and were primarily produced in Asian countries. Future research studies of comparing results from Western adolescent samples provide more insight on therapeutic intervention.

Citation: Chang MLY, Lee IO (2024) Functional connectivity changes in the brain of adolescents with internet addiction: A systematic literature review of imaging studies. PLOS Ment Health 1(1): e0000022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022

Editor: Kizito Omona, Uganda Martyrs University, UGANDA

Received: December 29, 2023; Accepted: March 18, 2024; Published: June 4, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Chang, Lee. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The behavioural addiction brought on by excessive internet use has become a rising source of concern [ 1 ] since the last decade. According to clinical studies, individuals with Internet Addiction (IA) or Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) may have a range of biopsychosocial effects and is classified as an impulse-control disorder owing to its resemblance to pathological gambling and substance addiction [ 2 , 3 ]. IA has been defined by researchers as a person’s inability to resist the urge to use the internet, which has negative effects on their psychological well-being as well as their social, academic, and professional lives [ 4 ]. The symptoms can have serious physical and interpersonal repercussions and are linked to mood modification, salience, tolerance, impulsivity, and conflict [ 5 ]. In severe circumstances, people may experience severe pain in their bodies or health issues like carpal tunnel syndrome, dry eyes, irregular eating and disrupted sleep [ 6 ]. Additionally, IA is significantly linked to comorbidities with other psychiatric disorders [ 7 ].

Stevens et al (2021) reviewed 53 studies including 17 countries and reported the global prevalence of IA was 3.05% [ 8 ]. Asian countries had a higher prevalence (5.1%) than European countries (2.7%) [ 8 ]. Strikingly, adolescents and young adults had a global IGD prevalence rate of 9.9% which matches previous literature that reported historically higher prevalence among adolescent populations compared to adults [ 8 , 9 ]. Over 80% of adolescent population in the UK, the USA, and Asia have direct access to the internet [ 10 ]. Children and adolescents frequently spend more time on media (possibly 7 hours and 22 minutes per day) than at school or sleeping [ 11 ]. Developing nations have also shown a sharp rise in teenage internet usage despite having lower internet penetration rates [ 10 ]. Concerns regarding the possible harms that overt internet use could do to adolescents and their development have arisen because of this surge, especially the significant impacts by the COVID-19 pandemic [ 12 ]. The growing prevalence and neurocognitive consequences of IA among adolescents makes this population a vital area of study [ 13 ].

Adolescence is a crucial developmental stage during which people go through significant changes in their biology, cognition, and personalities [ 14 ]. Adolescents’ emotional-behavioural functioning is hyperactivated, which creates risk of psychopathological vulnerability [ 15 ]. In accordance with clinical study results [ 16 ], this emotional hyperactivity is supported by a high level of neuronal plasticity. This plasticity enables teenagers to adapt to the numerous physical and emotional changes that occur during puberty as well as develop communication techniques and gain independence [ 16 ]. However, the strong neuronal plasticity is also associated with risk-taking and sensation seeking [ 17 ] which may lead to IA.

Despite the fact that the precise neuronal mechanisms underlying IA are still largely unclear, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) method has been used by scientists as an important framework to examine the neuropathological changes occurring in IA, particularly in the form of functional connectivity (FC) [ 18 ]. fMRI research study has shown that IA alters both the functional and structural makeup of the brain [ 3 ].

We hypothesise that IA has widespread neurological alteration effects rather than being limited to a few specific brain regions. Further hypothesis holds that according to these alterations of FC between the brain regions or certain neural networks, adolescents with IA would experience behavioural changes. An investigation of these domains could be useful for creating better procedures and standards as well as minimising the negative effects of overt internet use. This literature review aims to summarise and analyse the evidence of various imaging studies that have investigated the effects of IA on the FC in adolescents. This will be addressed through two research questions:

- How does internet addiction affect the functional connectivity in the adolescent brain?

- How is adolescent behaviour and development impacted by functional connectivity changes due to internet addiction?

The review protocol was conducted in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see S1 Checklist ).

Search strategy and selection process

A systematic search was conducted up until April 2023 from two sources of database, PubMed and PsycINFO, using a range of terms relevant to the title and research questions (see full list of search terms in S1 Appendix ). All the searched articles can be accessed in the S1 Data . The eligible articles were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria used for the present review were: (i) participants in the studies with clinical diagnosis of IA; (ii) participants between the ages of 10 and 19; (iii) imaging research investigations; (iv) works published between January 2013 and April 2023; (v) written in English language; (vi) peer-reviewed papers and (vii) full text. The numbers of articles excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria are shown in Fig 1 . Each study’s title and abstract were screened for eligibility.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.g001

Quality appraisal

Full texts of all potentially relevant studies were then retrieved and further appraised for eligibility. Furthermore, articles were critically appraised based on the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) framework to evaluate the individual study for both quality and bias. The subsequent quality levels were then appraised to each article and listed as either low, moderate, or high.

Data collection process

Data that satisfied the inclusion requirements was entered into an excel sheet for data extraction and further selection. An article’s author, publication year, country, age range, participant sample size, sex, area of interest, measures, outcome and article quality were all included in the data extraction spreadsheet. Studies looking at FC, for instance, were grouped, while studies looking at FC in specific area were further divided into sub-groups.

Data synthesis and analysis

Articles were classified according to their location in the brain as well as the network or pathway they were a part of to create a coherent narrative between the selected studies. Conclusions concerning various research trends relevant to particular groupings were drawn from these groupings and subgroupings. To maintain the offered information in a prominent manner, these assertions were entered into the data extraction excel spreadsheet.

With the search performed on the selected databases, 238 articles in total were identified (see Fig 1 ). 15 duplicated articles were eliminated, and another 6 items were removed for various other reasons. Title and abstract screening eliminated 184 articles because they were not in English (number of article, n, = 7), did not include imaging components (n = 47), had adult participants (n = 53), did not have a clinical diagnosis of IA (n = 19), did not address FC in the brain (n = 20), and were published outside the desired timeframe (n = 38). A further 21 papers were eliminated for failing to meet inclusion requirements after the remaining 33 articles underwent full-text eligibility screening. A total of 12 papers were deemed eligible for this review analysis.

Characteristics of the included studies, as depicted in the data extraction sheet in Table 1 provide information of the author(s), publication year, sample size, study location, age range, gender, area of interest, outcome, measures used and quality appraisal. Most of the studies in this review utilised resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging techniques (n = 7), with several studies demonstrating task-based fMRI procedures (n = 3), and the remaining studies utilising whole-brain imaging measures (n = 2). The studies were all conducted in Asiatic countries, specifically coming from China (8), Korea (3), and Indonesia (1). Sample sizes ranged from 12 to 31 participants with most of the imaging studies having comparable sample sizes. Majority of the studies included a mix of male and female participants (n = 8) with several studies having a male only participant pool (n = 3). All except one of the mixed gender studies had a majority male participant pool. One study did not disclose their data on the gender demographics of their experiment. Study years ranged from 2013–2022, with 2 studies in 2013, 3 studies in 2014, 3 studies in 2015, 1 study in 2017, 1 study in 2020, 1 study in 2021, and 1 study in 2022.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.t001

(1) How does internet addiction affect the functional connectivity in the adolescent brain?

The included studies were organised according to the brain region or network that they were observing. The specific networks affected by IA were the default mode network, executive control system, salience network and reward pathway. These networks are vital components of adolescent behaviour and development [ 31 ]. The studies in each section were then grouped into subsections according to their specific brain regions within their network.

Default mode network (DMN)/reward network.

Out of the 12 studies, 3 have specifically studied the default mode network (DMN), and 3 observed whole-brain FC that partially included components of the DMN. The effect of IA on the various centres of the DMN was not unilaterally the same. The findings illustrate a complex mix of increases and decreases in FC depending on the specific region in the DMN (see Table 2 and Fig 2 ). The alteration of FC in posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) in the DMN was the most frequently reported area in adolescents with IA, which involved in attentional processes [ 32 ], but Lee et al. (2020) additionally found alterations of FC in other brain regions, such as anterior insula cortex, a node in the DMN that controls the integration of motivational and cognitive processes [ 20 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.g002

The overall changes of functional connectivity in the brain network including default mode network (DMN), executive control network (ECN), salience network (SN) and reward network. IA = Internet Addiction, FC = Functional Connectivity.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.t002

Ding et al. (2013) revealed altered FC in the cerebellum, the middle temporal gyrus, and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [ 22 ]. They found that the bilateral inferior parietal lobule, left superior parietal lobule, and right inferior temporal gyrus had decreased FC, while the bilateral posterior lobe of the cerebellum and the medial temporal gyrus had increased FC [ 22 ]. The right middle temporal gyrus was found to have 111 cluster voxels (t = 3.52, p<0.05) and the right inferior parietal lobule was found to have 324 cluster voxels (t = -4.07, p<0.05) with an extent threshold of 54 voxels (figures above this threshold are deemed significant) [ 22 ]. Additionally, there was a negative correlation, with 95 cluster voxels (p<0.05) between the FC of the left superior parietal lobule and the PCC with the Chen Internet Addiction Scores (CIAS) which are used to determine the severity of IA [ 22 ]. On the other hand, in regions of the reward system, connection with the PCC was positively connected with CIAS scores [ 22 ]. The most significant was the right praecuneus with 219 cluster voxels (p<0.05) [ 22 ]. Wang et al. (2017) also discovered that adolescents with IA had 33% less FC in the left inferior parietal lobule and 20% less FC in the dorsal mPFC [ 24 ]. A potential connection between the effects of substance use and overt internet use is revealed by the generally decreased FC in these areas of the DMN of teenagers with drug addiction and IA [ 35 ].

The putamen was one of the main regions of reduced FC in adolescents with IA [ 19 ]. The putamen and the insula-operculum demonstrated significant group differences regarding functional connectivity with a cluster size of 251 and an extent threshold of 250 (Z = 3.40, p<0.05) [ 19 ]. The molecular mechanisms behind addiction disorders have been intimately connected to decreased striatal dopaminergic function [ 19 ], making this function crucial.

Executive Control Network (ECN).

5 studies out of 12 have specifically viewed parts of the executive control network (ECN) and 3 studies observed whole-brain FC. The effects of IA on the ECN’s constituent parts were consistent across all the studies examined for this analysis (see Table 2 and Fig 3 ). The results showed a notable decline in all the ECN’s major centres. Li et al. (2014) used fMRI imaging and a behavioural task to study response inhibition in adolescents with IA [ 25 ] and found decreased activation at the striatum and frontal gyrus, particularly a reduction in FC at inferior frontal gyrus, in the IA group compared to controls [ 25 ]. The inferior frontal gyrus showed a reduction in FC in comparison to the controls with a cluster size of 71 (t = 4.18, p<0.05) [ 25 ]. In addition, the frontal-basal ganglia pathways in the adolescents with IA showed little effective connection between areas and increased degrees of response inhibition [ 25 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.g003

Lin et al. (2015) found that adolescents with IA demonstrated disrupted corticostriatal FC compared to controls [ 33 ]. The corticostriatal circuitry experienced decreased connectivity with the caudate, bilateral anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), as well as the striatum and frontal gyrus [ 33 ]. The inferior ventral striatum showed significantly reduced FC with the subcallosal ACC and caudate head with cluster size of 101 (t = -4.64, p<0.05) [ 33 ]. Decreased FC in the caudate implies dysfunction of the corticostriatal-limbic circuitry involved in cognitive and emotional control [ 36 ]. The decrease in FC in both the striatum and frontal gyrus is related to inhibitory control, a common deficit seen with disruptions with the ECN [ 33 ].

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), ACC, and right supplementary motor area (SMA) of the prefrontal cortex were all found to have significantly decreased grey matter volume [ 29 ]. In addition, the DLPFC, insula, temporal cortices, as well as significant subcortical regions like the striatum and thalamus, showed decreased FC [ 29 ]. According to Tremblay (2009), the striatum plays a significant role in the processing of rewards, decision-making, and motivation [ 37 ]. Chen et al. (2020) reported that the IA group demonstrated increased impulsivity as well as decreased reaction inhibition using a Stroop colour-word task [ 26 ]. Furthermore, Chen et al. (2020) observed that the left DLPFC and dorsal striatum experienced a negative connection efficiency value, specifically demonstrating that the dorsal striatum activity suppressed the left DLPFC [ 27 ].

Salience network (SN).

Out of the 12 chosen studies, 3 studies specifically looked at the salience network (SN) and 3 studies have observed whole-brain FC. Relative to the DMN and ECN, the findings on the SN were slightly sparser. Despite this, adolescents with IA demonstrated a moderate decrease in FC, as well as other measures like fibre connectivity and cognitive control, when compared to healthy control (see Table 2 and Fig 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.g004

Xing et al. (2014) used both dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and insula to test FC changes in the SN of adolescents with IA and found decreased structural connectivity in the SN as well as decreased fractional anisotropy (FA) that correlated to behaviour performance in the Stroop colour word-task [ 21 ]. They examined the dACC and insula to determine whether the SN’s disrupted connectivity may be linked to the SN’s disruption of regulation, which would explain the impaired cognitive control seen in adolescents with IA. However, researchers did not find significant FC differences in the SN when compared to the controls [ 21 ]. These results provided evidence for the structural changes in the interconnectivity within SN in adolescents with IA.

Wang et al. (2017) investigated network interactions between the DMN, ECN, SN and reward pathway in IA subjects [ 24 ] (see Fig 5 ), and found 40% reduction of FC between the DMN and specific regions of the SN, such as the insula, in comparison to the controls (p = 0.008) [ 24 ]. The anterior insula and dACC are two areas that are impacted by this altered FC [ 24 ]. This finding supports the idea that IA has similar neurobiological abnormalities with other addictive illnesses, which is in line with a study that discovered disruptive changes in the SN and DMN’s interaction in cocaine addiction [ 38 ]. The insula has also been linked to the intensity of symptoms and has been implicated in the development of IA [ 39 ].

“+” indicates an increase in behaivour; “-”indicates a decrease in behaviour; solid arrows indicate a direct network interaction; and the dotted arrows indicates a reduction in network interaction. This diagram depicts network interactions juxtaposed with engaging in internet related behaviours. Through the neural interactions, the diagram illustrates how the networks inhibit or amplify internet usage and vice versa. Furthermore, it demonstrates how the SN mediates both the DMN and ECN.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.g005

(2) How is adolescent behaviour and development impacted by functional connectivity changes due to internet addiction?

The findings that IA individuals demonstrate an overall decrease in FC in the DMN is supported by numerous research [ 24 ]. Drug addict populations also exhibited similar decline in FC in the DMN [ 40 ]. The disruption of attentional orientation and self-referential processing for both substance and behavioural addiction was then hypothesised to be caused by DMN anomalies in FC [ 41 ].

In adolescents with IA, decline of FC in the parietal lobule affects visuospatial task-related behaviour [ 22 ], short-term memory [ 42 ], and the ability of controlling attention or restraining motor responses during response inhibition tests [ 42 ]. Cue-induced gaming cravings are influenced by the DMN [ 43 ]. A visual processing area called the praecuneus links gaming cues to internal information [ 22 ]. A meta-analysis found that the posterior cingulate cortex activity of individuals with IA during cue-reactivity tasks was connected with their gaming time [ 44 ], suggesting that excessive gaming may impair DMN function and that individuals with IA exert more cognitive effort to control it. Findings for the behavioural consequences of FC changes in the DMN illustrate its underlying role in regulating impulsivity, self-monitoring, and cognitive control.

Furthermore, Ding et al. (2013) reported an activation of components of the reward pathway, including areas like the nucleus accumbens, praecuneus, SMA, caudate, and thalamus, in connection to the DMN [ 22 ]. The increased FC of the limbic and reward networks have been confirmed to be a major biomarker for IA [ 45 , 46 ]. The increased reinforcement in these networks increases the strength of reward stimuli and makes it more difficult for other networks, namely the ECN, to down-regulate the increased attention [ 29 ] (See Fig 5 ).

Executive control network (ECN).

The numerous IA-affected components in the ECN have a role in a variety of behaviours that are connected to both response inhibition and emotional regulation [ 47 ]. For instance, brain regions like the striatum, which are linked to impulsivity and the reward system, are heavily involved in the act of playing online games [ 47 ]. Online game play activates the striatum, which suppresses the left DLPFC in ECN [ 48 ]. As a result, people with IA may find it difficult to control their want to play online games [ 48 ]. This system thus causes impulsive and protracted gaming conduct, lack of inhibitory control leading to the continued use of internet in an overt manner despite a variety of negative effects, personal distress, and signs of psychological dependence [ 33 ] (See Fig 5 ).

Wang et al. (2017) report that disruptions in cognitive control networks within the ECN are frequently linked to characteristics of substance addiction [ 24 ]. With samples that were addicted to heroin and cocaine, previous studies discovered abnormal FC in the ECN and the PFC [ 49 ]. Electronic gaming is known to promote striatal dopamine release, similar to drug addiction [ 50 ]. According to Drgonova and Walther (2016), it is hypothesised that dopamine could stimulate the reward system of the striatum in the brain, leading to a loss of impulse control and a failure of prefrontal lobe executive inhibitory control [ 51 ]. In the end, IA’s resemblance to drug use disorders may point to vital biomarkers or underlying mechanisms that explain how cognitive control and impulsive behaviour are related.

A task-related fMRI study found that the decrease in FC between the left DLPFC and dorsal striatum was congruent with an increase in impulsivity in adolescents with IA [ 26 ]. The lack of response inhibition from the ECN results in a loss of control over internet usage and a reduced capacity to display goal-directed behaviour [ 33 ]. Previous studies have linked the alteration of the ECN in IA with higher cue reactivity and impaired ability to self-regulate internet specific stimuli [ 52 ].

Salience network (SN)/ other networks.

Xing et al. (2014) investigated the significance of the SN regarding cognitive control in teenagers with IA [ 21 ]. The SN, which is composed of the ACC and insula, has been demonstrated to control dynamic changes in other networks to modify cognitive performance [ 21 ]. The ACC is engaged in conflict monitoring and cognitive control, according to previous neuroimaging research [ 53 ]. The insula is a region that integrates interoceptive states into conscious feelings [ 54 ]. The results from Xing et al. (2014) showed declines in the SN regarding its structural connectivity and fractional anisotropy, even though they did not observe any appreciable change in FC in the IA participants [ 21 ]. Due to the small sample size, the results may have indicated that FC methods are not sensitive enough to detect the significant functional changes [ 21 ]. However, task performance behaviours associated with impaired cognitive control in adolescents with IA were correlated with these findings [ 21 ]. Our comprehension of the SN’s broader function in IA can be enhanced by this relationship.

Research study supports the idea that different psychological issues are caused by the functional reorganisation of expansive brain networks, such that strong association between SN and DMN may provide neurological underpinnings at the system level for the uncontrollable character of internet-using behaviours [ 24 ]. In the study by Wang et al. (2017), the decreased interconnectivity between the SN and DMN, comprising regions such the DLPFC and the insula, suggests that adolescents with IA may struggle to effectively inhibit DMN activity during internally focused processing, leading to poorly managed desires or preoccupations to use the internet [ 24 ] (See Fig 5 ). Subsequently, this may cause a failure to inhibit DMN activity as well as a restriction of ECN functionality [ 55 ]. As a result, the adolescent experiences an increased salience and sensitivity towards internet addicting cues making it difficult to avoid these triggers [ 56 ].

The primary aim of this review was to present a summary of how internet addiction impacts on the functional connectivity of adolescent brain. Subsequently, the influence of IA on the adolescent brain was compartmentalised into three sections: alterations of FC at various brain regions, specific FC relationships, and behavioural/developmental changes. Overall, the specific effects of IA on the adolescent brain were not completely clear, given the variety of FC changes. However, there were overarching behavioural, network and developmental trends that were supported that provided insight on adolescent development.

The first hypothesis that was held about this question was that IA was widespread and would be regionally similar to substance-use and gambling addiction. After conducting a review of the information in the chosen articles, the hypothesis was predictably supported. The regions of the brain affected by IA are widespread and influence multiple networks, mainly DMN, ECN, SN and reward pathway. In the DMN, there was a complex mix of increases and decreases within the network. However, in the ECN, the alterations of FC were more unilaterally decreased, but the findings of SN and reward pathway were not quite clear. Overall, the FC changes within adolescents with IA are very much network specific and lay a solid foundation from which to understand the subsequent behaviour changes that arise from the disorder.

The second hypothesis placed emphasis on the importance of between network interactions and within network interactions in the continuation of IA and the development of its behavioural symptoms. The results from the findings involving the networks, DMN, SN, ECN and reward system, support this hypothesis (see Fig 5 ). Studies confirm the influence of all these neural networks on reward valuation, impulsivity, salience to stimuli, cue reactivity and other changes that alter behaviour towards the internet use. Many of these changes are connected to the inherent nature of the adolescent brain.

There are multiple explanations that underlie the vulnerability of the adolescent brain towards IA related urges. Several of them have to do with the inherent nature and underlying mechanisms of the adolescent brain. Children’s emotional, social, and cognitive capacities grow exponentially during childhood and adolescence [ 57 ]. Early teenagers go through a process called “social reorientation” that is characterised by heightened sensitivity to social cues and peer connections [ 58 ]. Adolescents’ improvements in their social skills coincide with changes in their brains’ anatomical and functional organisation [ 59 ]. Functional hubs exhibit growing connectivity strength [ 60 ], suggesting increased functional integration during development. During this time, the brain’s functional networks change from an anatomically dominant structure to a scattered architecture [ 60 ].

The adolescent brain is very responsive to synaptic reorganisation and experience cues [ 61 ]. As a result, one of the distinguishing traits of the maturation of adolescent brains is the variation in neural network trajectory [ 62 ]. Important weaknesses of the adolescent brain that may explain the neurobiological change brought on by external stimuli are illustrated by features like the functional gaps between networks and the inadequate segregation of networks [ 62 ].

The implications of these findings towards adolescent behaviour are significant. Although the exact changes and mechanisms are not fully clear, the observed changes in functional connectivity have the capacity of influencing several aspects of adolescent development. For example, functional connectivity has been utilised to investigate attachment styles in adolescents [ 63 ]. It was observed that adolescent attachment styles were negatively associated with caudate-prefrontal connectivity, but positively with the putamen-visual area connectivity [ 63 ]. Both named areas were also influenced by the onset of internet addiction, possibly providing a connection between the two. Another study associated neighbourhood/socioeconomic disadvantage with functional connectivity alterations in the DMN and dorsal attention network [ 64 ]. The study also found multivariate brain behaviour relationships between the altered/disadvantaged functional connectivity and mental health and cognition [ 64 ]. This conclusion supports the notion that the functional connectivity alterations observed in IA are associated with specific adolescent behaviours as well as the fact that functional connectivity can be utilised as a platform onto which to compare various neurologic conditions.

Limitations/strengths

There were several limitations that were related to the conduction of the review as well as the data extracted from the articles. Firstly, the study followed a systematic literature review design when analysing the fMRI studies. The data pulled from these imaging studies were namely qualitative and were subject to bias contrasting the quantitative nature of statistical analysis. Components of the study, such as sample sizes, effect sizes, and demographics were not weighted or controlled. The second limitation brought up by a similar review was the lack of a universal consensus of terminology given IA [ 47 ]. Globally, authors writing about this topic use an array of terminology including online gaming addiction, internet addiction, internet gaming disorder, and problematic internet use. Often, authors use multiple terms interchangeably which makes it difficult to depict the subtle similarities and differences between the terms.

Reviewing the explicit limitations in each of the included studies, two major limitations were brought up in many of the articles. One was relating to the cross-sectional nature of the included studies. Due to the inherent qualities of a cross-sectional study, the studies did not provide clear evidence that IA played a causal role towards the development of the adolescent brain. While several biopsychosocial factors mediate these interactions, task-based measures that combine executive functions with imaging results reinforce the assumed connection between the two that is utilised by the papers studying IA. Another limitation regarded the small sample size of the included studies, which averaged to around 20 participants. The small sample size can influence the generalisation of the results as well as the effectiveness of statistical analyses. Ultimately, both included study specific limitations illustrate the need for future studies to clarify the causal relationship between the alterations of FC and the development of IA.

Another vital limitation was the limited number of studies applying imaging techniques for investigations on IA in adolescents were a uniformly Far East collection of studies. The reason for this was because the studies included in this review were the only fMRI studies that were found that adhered to the strict adolescent age restriction. The adolescent age range given by the WHO (10–19 years old) [ 65 ] was strictly followed. It is important to note that a multitude of studies found in the initial search utilised an older adolescent demographic that was slightly higher than the WHO age range and had a mean age that was outside of the limitations. As a result, the results of this review are biased and based on the 12 studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Regarding the global nature of the research, although the journals that the studies were published in were all established western journals, the collection of studies were found to all originate from Asian countries, namely China and Korea. Subsequently, it pulls into question if the results and measures from these studies are generalisable towards a western population. As stated previously, Asian countries have a higher prevalence of IA, which may be the reasoning to why the majority of studies are from there [ 8 ]. However, in an additional search including other age groups, it was found that a high majority of all FC studies on IA were done in Asian countries. Interestingly, western papers studying fMRI FC were primarily focused on gambling and substance-use addiction disorders. The western papers on IA were less focused on fMRI FC but more on other components of IA such as sleep, game-genre, and other non-imaging related factors. This demonstrated an overall lack of western fMRI studies on IA. It is important to note that both western and eastern fMRI studies on IA presented an overall lack on children and adolescents in general.

Despite the several limitations, this review provided a clear reflection on the state of the data. The strengths of the review include the strict inclusion/exclusion criteria that filtered through studies and only included ones that contained a purely adolescent sample. As a result, the information presented in this review was specific to the review’s aims. Given the sparse nature of adolescent specific fMRI studies on the FC changes in IA, this review successfully provided a much-needed niche representation of adolescent specific results. Furthermore, the review provided a thorough functional explanation of the DMN, ECN, SN and reward pathway making it accessible to readers new to the topic.

Future directions and implications

Through the search process of the review, there were more imaging studies focused on older adolescence and adulthood. Furthermore, finding a review that covered a strictly adolescent population, focused on FC changes, and was specifically depicting IA, was proven difficult. Many related reviews, such as Tereshchenko and Kasparov (2019), looked at risk factors related to the biopsychosocial model, but did not tackle specific alterations in specific structural or functional changes in the brain [ 66 ]. Weinstein (2017) found similar structural and functional results as well as the role IA has in altering response inhibition and reward valuation in adolescents with IA [ 47 ]. Overall, the accumulated findings only paint an emerging pattern which aligns with similar substance-use and gambling disorders. Future studies require more specificity in depicting the interactions between neural networks, as well as more literature on adolescent and comorbid populations. One future field of interest is the incorporation of more task-based fMRI data. Advances in resting-state fMRI methods have yet to be reflected or confirmed in task-based fMRI methods [ 62 ]. Due to the fact that network connectivity is shaped by different tasks, it is critical to confirm that the findings of the resting state fMRI studies also apply to the task based ones [ 62 ]. Subsequently, work in this area will confirm if intrinsic connectivity networks function in resting state will function similarly during goal directed behaviour [ 62 ]. An elevated focus on adolescent populations as well as task-based fMRI methodology will help uncover to what extent adolescent network connectivity maturation facilitates behavioural and cognitive development [ 62 ].

A treatment implication is the potential usage of bupropion for the treatment of IA. Bupropion has been previously used to treat patients with gambling disorder and has been effective in decreasing overall gambling behaviour as well as money spent while gambling [ 67 ]. Bae et al. (2018) found a decrease in clinical symptoms of IA in line with a 12-week bupropion treatment [ 31 ]. The study found that bupropion altered the FC of both the DMN and ECN which in turn decreased impulsivity and attentional deficits for the individuals with IA [ 31 ]. Interventions like bupropion illustrate the importance of understanding the fundamental mechanisms that underlie disorders like IA.

The goal for this review was to summarise the current literature on functional connectivity changes in adolescents with internet addiction. The findings answered the primary research questions that were directed at FC alterations within several networks of the adolescent brain and how that influenced their behaviour and development. Overall, the research demonstrated several wide-ranging effects that influenced the DMN, SN, ECN, and reward centres. Additionally, the findings gave ground to important details such as the maturation of the adolescent brain, the high prevalence of Asian originated studies, and the importance of task-based studies in this field. The process of making this review allowed for a thorough understanding IA and adolescent brain interactions.

Given the influx of technology and media in the lives and education of children and adolescents, an increase in prevalence and focus on internet related behavioural changes is imperative towards future children/adolescent mental health. Events such as COVID-19 act to expose the consequences of extended internet usage on the development and lifestyle of specifically young people. While it is important for parents and older generations to be wary of these changes, it is important for them to develop a base understanding of the issue and not dismiss it as an all-bad or all-good scenario. Future research on IA will aim to better understand the causal relationship between IA and psychological symptoms that coincide with it. The current literature regarding functional connectivity changes in adolescents is limited and requires future studies to test with larger sample sizes, comorbid populations, and populations outside Far East Asia.

This review aimed to demonstrate the inner workings of how IA alters the connection between the primary behavioural networks in the adolescent brain. Predictably, the present answers merely paint an unfinished picture that does not necessarily depict internet usage as overwhelmingly positive or negative. Alternatively, the research points towards emerging patterns that can direct individuals on the consequences of certain variables or risk factors. A clearer depiction of the mechanisms of IA would allow physicians to screen and treat the onset of IA more effectively. Clinically, this could be in the form of more streamlined and accurate sessions of CBT or family therapy, targeting key symptoms of IA. Alternatively clinicians could potentially prescribe treatment such as bupropion to target FC in certain regions of the brain. Furthermore, parental education on IA is another possible avenue of prevention from a public health standpoint. Parents who are aware of the early signs and onset of IA will more effectively handle screen time, impulsivity, and minimize the risk factors surrounding IA.

Additionally, an increased attention towards internet related fMRI research is needed in the West, as mentioned previously. Despite cultural differences, Western countries may hold similarities to the eastern countries with a high prevalence of IA, like China and Korea, regarding the implications of the internet and IA. The increasing influence of the internet on the world may contribute to an overall increase in the global prevalence of IA. Nonetheless, the high saturation of eastern studies in this field should be replicated with a Western sample to determine if the same FC alterations occur. A growing interest in internet related research and education within the West will hopefully lead to the knowledge of healthier internet habits and coping strategies among parents with children and adolescents. Furthermore, IA research has the potential to become a crucial proxy for which to study adolescent brain maturation and development.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. prisma checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.s001

S1 Appendix. Search strategies with all the terms.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.s002

S1 Data. Article screening records with details of categorized content.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmen.0000022.s003

Acknowledgments

The authors thank https://www.stockio.com/free-clipart/brain-01 (with attribution to Stockio.com); and https://www.rawpixel.com/image/6442258/png-sticker-vintage for the free images used to create Figs 2 – 4 .

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 2. Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5 ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- 10. Stats IW. World Internet Users Statistics and World Population Stats 2013 [ http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm .

- 11. Rideout VJR M. B. The common sense census: media use by tweens and teens. San Francisco, CA: Common Sense Media; 2019.

- 37. Tremblay L. The Ventral Striatum. Handbook of Reward and Decision Making: Academic Press; 2009.

- 57. Bhana A. Middle childhood and pre-adolescence. Promoting mental health in scarce-resource contexts: emerging evidence and practice. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2010. p. 124–42.

- 65. Organization WH. Adolescent Health 2023 [ https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 .

‘Kafka’ Review: The Man Behind ‘The Metamorphosis’

W as Max Brod the Judas Iscariot of 20th-century literature? The wily, six-part “Kafka” suggests as much, though one can regard both figures as paradoxical: If Judas hadn’t sinned, a mission wouldn’t have been fulfilled. If Brod hadn’t ignored his friend Franz’s request—that he burn the author’s unpublished manuscripts after his death—we would never have had “The Trial,” “The Castle” or “Amerika.”

The loss to readers would have been enormous, certainly. But the act of betrayal was also good for the brand: One can imagine Franz Kafka, detached and double-crossed, declaring from the grave that he expected no less.

It is a devoted Brod (David Kross) whom we see cradling Kafka’s papers aboard the last train across the Czech border in 1939, a sequence out of a wartime thriller yet a bit anomalous to the rest of “Kafka.” Co-written by author Daniel Kehlmann (“Measuring the World”) and David Schalko, directed by Mr. Schalko and airing on ChaiFlicks (the “Jewish Netflix”), the series creates a portrait of the artist—who died 100 years ago this week—with a palette of insecurities, perfectionism, hobbled sexuality and tuberculosis. It finds sources of dry comedy in the domestic life of the bourgeois Kafka family in Prague and in Franz’s romantic catastrophes. It reduces complex psychology to amusing tableaux and incorporates references to Kafka’s novels—the thuggish interrogators of “The Trial,” or the castle from “The Castle”—into Kafka’s oft-represented dreamlife.

But it is Brod who provides the necessary setup to this surreal treatment of a problematic subject, a frame for the picture. A successful and prolific writer of the time (among other things, he translated the libretti of Leoš Janáček into German), he is besotted by the idea of the artistic life—he constantly refers to his literary friends as “the Prague Circle,” though there is no circle, only Kafka (Joel Basman). As a failed artist himself, Brod reveres Franz for his purity and standards and acts as a champion and coach. “Write more!” he urges Franz, who answers that his writing isn’t good. “It will be good enough,” Brod responds, and Franz seizes on the thought, that something only “good enough” could enter the realm of his possibilities.

In what one supposes is reverence to the Kafka aesthetic, the filmmakers—with whom Kafka biographer Reiner Stach acted as consultant—combine the fantastical with the incongruously sober, the fictional with fact: Franz, browbeaten by his brutish father, Hermann (Nicholas Ofczarek), signs a contract to be part owner of his brother-in-law’s asbestos factory with no idea of his duties or authority and finds himself in a situation that might be described as, alas, Kafkaesque, an adjective that remains among Kafka’s more popular contributions to language.

The series, aside from the Brod-dominated episode 1, is focused on various aspects of Kafka’s life, which was short—he was only 40 when he died, in obscurity, of tuberculosis in 1924. The approach is wry, the production design is theatrical, the situations are rendered with absurdity front and center: Franz’s on-again, off-again engagement to Felice Bauer (Lia von Blarer), their relationship based almost entirely on correspondence, is a protracted disaster; Franz is quite comfortable in the brothels of Prague, but incapable of consummating beyond their walls, or with someone he cares for. This becomes more painfully apparent during episode 5, which involves Milena Jesenská (Liv Lisa Fries of “Babylon Berlin”), who has translated the Bohemian Kafka’s writing to Czech from German. Per the series (not all of which is to be taken as gospel), she is ready to leave her husband for “Frank,” as she calls him, before he talks her out of it by overthinking passion. (Ms. Fries steals the scene by visibly withering as he speaks; Mr. Basman’s Frank is insistently odd throughout.) This sets up the most electric moment in the entire show, Milena’s excoriation of Kafka for his cultivated alienation, which she interprets, quite convincingly, as narcissism.

ChaiFlicks, per its mission, is interested in Kafka’s Jewishness and his oft-debated devotion to Zionism—he and Felice discuss a trip to Palestine, which like many of Kafka’s promises never comes true. More biting and even haunting, given the pre- and post-World War I era “Kafka” occupies, is episode 3. In it, Kafka attends a performance by a visiting Yiddish theater troupe and is utterly delighted, even as his friends mock what they see as vulgar kitsch. In a gesture of utter blindness (or bile), Franz brings home one of the actors, Jizchak Löwy (Konstantin Frank), to the Kafka dinner table, where Jizchak regales the family in Yiddish and Hermann is disgusted by the “vermin” his son has allowed to enter his home. It is an affront to Hermann’s assimilated self to have a reminder of his roots come into his house. And how ironic, given that three of Franz’s sisters would die in the Holocaust, no distinction having been made between one Jew or the other.

Mr. Anderson is the Journal’s TV critic.

- Scoping Review

- Open access

- Published: 23 September 2022

Interventions pathways to reduce tuberculosis-related stigma: a literature review and conceptual framework

- Charlotte Nuttall 1 na1 ,

- Ahmad Fuady ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0030-0524 2 , 3 , 4 na1 ,

- Holly Nuttall 1 ,

- Kritika Dixit 5 , 6 ,

- Muchtaruddin Mansyur 2 &

- Tom Wingfield ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8433-6887 1 , 5 , 7 , 8

Infectious Diseases of Poverty volume 11 , Article number: 101 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6173 Accesses

9 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

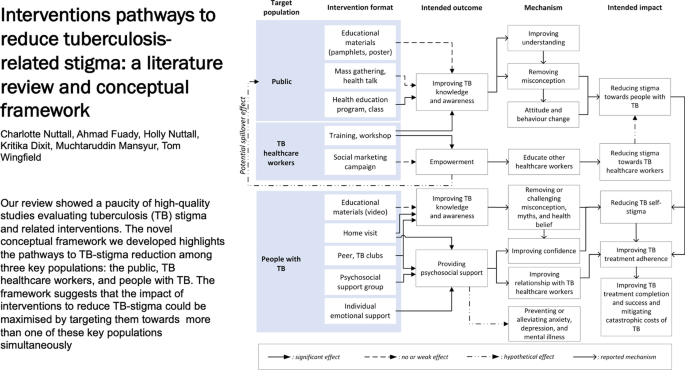

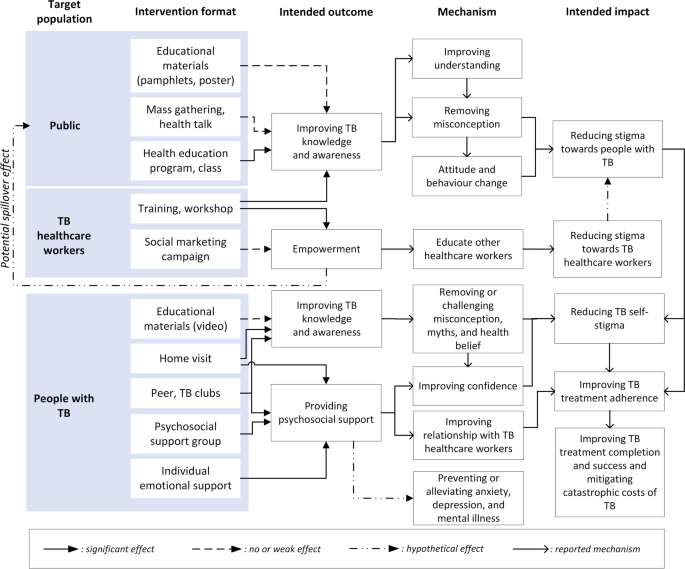

Prevention of tuberculosis (TB)-related stigma is vital to achieving the World Health Organisation’s End TB Strategy target of eliminating TB. However, the process and impact evaluation of interventions to reduce TB-stigma are limited. This literature review aimed to examine the quality, design, implementation challenges, and successes of TB-stigma intervention studies and create a novel conceptual framework of pathways to TB-stigma reduction.

We searched relevant articles recorded in four scientific databases from 1999 to 2022, using pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, supplemented by the snowball method and complementary grey literature searches. We assessed the quality of studies using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool, then reviewed study characteristics, data on stigma measurement tools used, and interventions implemented, and designed a conceptual framework to illustrate the pathways to TB-stigma reduction in the interventions identified.

Of 14,259 articles identified, eleven met inclusion criteria, of which three were high quality. TB-stigma reduction interventions consisted mainly of education and psychosocial support targeted predominantly toward three key populations: people with TB, healthcare workers, and the public. No psychosocial interventions for people with TB set TB-stigma reduction as their primary or co-primary aim. Eight studies on healthcare workers and the public reported a decrease in TB-stigma attributed to the interventions. Despite the benefits, the interventions were limited by a dearth of validated stigma measurement tools. Three of eight studies with quantitative stigma measurement questionnaires had not been previously validated among people with TB. No qualitative studies used previously validated methods or tools to qualitatively evaluate stigma. On the basis of these findings, we generated a conceptual framework that mapped the population targeted, interventions delivered, and their potential effects on reducing TB-stigma towards and experienced by people with TB and healthcare workers involved in TB care.

Conclusions

Interpretation of the limited evidence on interventions to reduce TB-stigma is hampered by the heterogeneity of stigma measurement tools, intervention design, and outcome measures. Our novel conceptual framework will support mapping of the pathways to impacts of TB-stigma reduction interventions.

Graphical Abstract

Stigma experienced by people with or affected by tuberculosis (TB)—henceforth termed TB-stigma—remains one of the major challenges in TB control [ 1 , 2 ]. TB-stigma has been shown to delay health-seeking behaviour [ 3 ]. This challenge has been aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic which has restricted access to healthcare, reduced the number of people notified with TB, and been associated with an increase in TB mortality [ 1 , 4 , 5 ]. TB-stigma has also been shown to reduce treatment compliance, and negatively impact on TB treatment outcomes [ 6 , 7 ]. The prevalence of TB-stigma varies geographically and, in specific subpopulations, has been estimated to affect up to 80% of people with TB [ 8 , 9 ]. Therefore, in the context of TB control, TB-stigma is one of the major social determinants of health and contributes to compounding health inequalities [ 1 , 10 , 11 ].

For these reasons, the Global Fund and UN high-level meeting highlighted TB-Stigma as one of the most significant barriers to reaching the World Health Organization (WHO) End TB goal of eliminating TB by 2050 and called on the international community to “promote and support an end to stigma and all forms of discrimination” [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Despite this, few resources have been mobilised to address this issue [ 15 ]. In part, this is due to inherent difficulties in the identification and measurement of TB-Stigma and the complexity and limited evidence base relating to stigma-reduction interventions [ 16 ].

Measuring stigma is vital to understand its determinants, prevalence and assess the effectiveness of stigma-reduction interventions [ 17 ]. Multiple scales and tools exist that assess health-related stigma [ 18 ]. To be robust and reliable, these tools should have been validated in the community or population in which they are to be used and then refined to ensure they are accurate, specific, and reliable. In 2018, the KNCV Tuberculosis Foundation created a TB-Stigma Handbook, which provides examples of how the limited available set of existing tools can best be applied to measure and evaluate stigma [ 19 ]. However, most studies to date have used either disparate, invalidated tools or solely qualitative measures of stigma. This has made it difficult to broaden our understanding of the determinants and consequences of TB-Stigma [ 15 , 20 ] (Box 1 ).

In addition, despite recognition of the global importance of TB-stigma, there has been limited critical appraisal in the literature of the few existing interventions aimed at reducing TB-stigma. The single related systematic review on TB-Stigma by Sommerland et al. focused on the effectiveness of stigma-reduction interventions [ 17 ]. Measuring and reducing TB-Stigma is complex. It involves interrelated, heterogeneous system structures, and multiple approaches from the individual to societal level [ 16 ]. Therefore, it is critical to evaluate not only the scale but also the challenges and successes in the design and implementation processes of interventions to reduce TB-stigma. These evaluations will help identify the weaknesses in current TB-stigma intervention design and delivery in order to refine these interventions for future implementation and scale-up.

We reviewed studies reporting interventions to reduce TB-Stigma. The review appraised the study design and stigma measurement tools, identified their challenges and successes, and evaluated their pathways to impact on TB-Stigma. We then developed a conceptual framework for the TB-Stigma reduction pathway to support researchers to successfully design and deliver impactful TB-stigma reduction interventions.

Box 1 Types of TB-stigma [ 18 ]

Enacted (or experienced) stigma encompasses the range of behaviours directly experienced by a person with TB.

Anticipated stigma is the expectation and fear of discrimination and behaviour of others towards a person if they are diagnosed and/or unwell with TB, which has an impact on health-seeking behaviour, whether enacted stigma occurs or not.

Internalised (or self) stigma is when those diagnosed and/or unwell with TB may accept a negative stereotype about people with TB and potentially act in a way that endorses this stereotype.

Secondary or external stigma is negative attitude towards family members, caregivers, friends, or TB healthcare workers because they are associated with, live with, or have close contact with people with TB.

This study was a systematic literature review. A preliminary scoping search was conducted to ensure that all relevant key terms were identified, and the final search strategy refined.

Search terms and management of search results

The following search terms were used within four databases (CINAHL Complete, Medline Complete, Global Health and PubMed): (TB OR Tubercul* OR “Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections”) AND (stigma* OR discrimin* OR “social stigma” OR barrier* OR attitude* OR “social discrimination” OR marginalisation OR “psychosocial impact” OR “socioeconomic impact” OR shame OR “social isolation” OR “social inclusion” OR prejudice OR perception OR “self-esteem”) AND (interven* OR strateg* OR pathway* OR education OR “psychosocial intervention*” OR “psychoemotional intervention*” OR “socioeconomic intervention*” OR “social support” OR “patient support” OR “training workshop*” OR “counselling”) were searched. In addition, the “snowballing” method of reference tracking and searches of Google Scholar and the WHO database for grey literature were used to identify additional articles that may have been overlooked by the initial search strategy. Searches were limited to December 31, 2021. Citations of the articles identified from the searches were exported into Endnote X9 (Camelot UK Bidco Limited/Clarivate, UK). Duplicates were then identified and removed using the duplicates tool in Endnote X9. The titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were read through and screened for relevance independently by three reviewers (CN, HN, AF). Where there were unresolved disagreements, a fourth senior reviewer finalized screening for inclusion or exclusion (TW). We applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria, documented the reasons for article exclusion, and identified the relevant articles for full-text review. Finally, supplemental manual review of the reference lists of the selected full-text articles was performed to identify any further articles for inclusion.

Selection criteria

Eligible studies included those that reported the implementation and evaluation of TB-stigma reduction interventions amongst people with TB and their households, healthcare workers, and the general public. Included study designs were intervention studies with randomised controlled trials, non-randomised controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, mixed-methods studies, qualitative studies, cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. The review was restricted to articles that were written in English. Articles were excluded if they did not report measurement of stigma.

Critical appraisal

Critical appraisal was undertaken by three reviewers (CN, HN, AF) using the “Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool” (CCAT), Version 1.4, to determine the quality of each study [ 21 ]. The CCAT was selected as it has been proven to be reliable and valid for the analysis of multiple studies of heterogenous design and implementation approaches, and can reduce rater bias [ 22 ]. To further reduce researcher bias, each individual assessment was cross-checked. A fourth reviewer (TW) resolved any discrepancies. A priori, and in line with published guidance [ 21 ], a pragmatic decision was taken by the study team that articles with a CCAT score between 75% and 100% would be deemed high quality, 50% and 74% moderate, and below 50% to be low quality.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data on country and region of intervention, target population, type of stigma studied, the scale or tool used to assess stigma, intervention activities, challenges and successes of intervention, the impact of intervention, and reported changes to TB practice and policy were collated and tabulated. Further information on the intervention including format, content, outcomes (both reported and intended if different) and detail on how the intervention reduced TB-stigma (theory explicitly stated in the main text or implied in objectives or methods) were also tabulated. Qualitative details were lifted directly from the text and copied into the data-extraction table. The articles were read carefully for similar and recurring themes and concepts. The concepts were then organised to determine any contradictory concepts, which were then removed. A conceptual framework was then created to organise the variables and concepts perceived by the research team to contribute to the pathways by which an intervention successfully reduced TB-stigma. The intention of the novel conceptual framework was to support researchers to design, develop, and implement a successful and sustainable stigma-reduction intervention in current and future studies [ 23 ]. With respect to stigma measurement tools and scales, these were evaluated through collection of data including: the tool or scale used; implementation methods; methods to reduce bias and ensure validity; internal and external validation and piloting prior to use; comparison of stigma scores before and after the intervention or between study groups; types of stigma assessed; whether the tool was adapted from a previously validated tool; and the described limitations of the tool. Any required data that was missing from the published papers was collected by directly contacting the corresponding author of the paper.

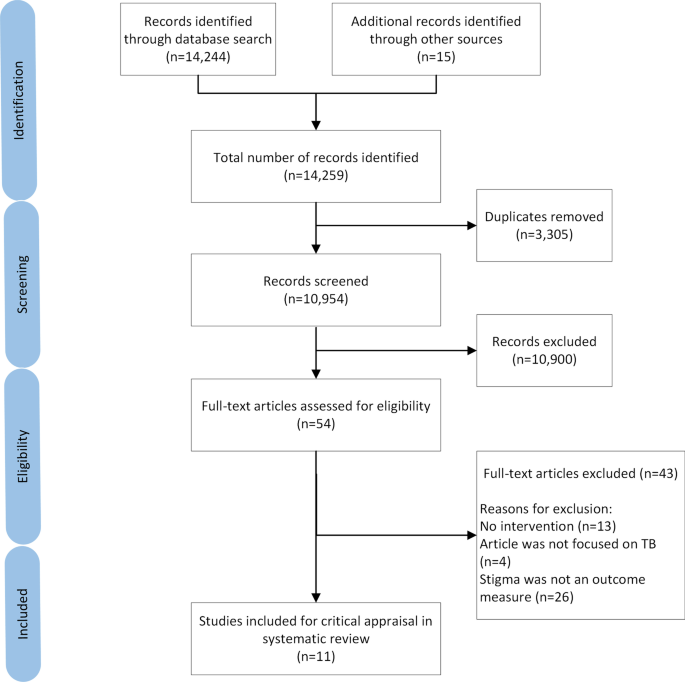

The search yielded 14,244 articles with 15 further articles identified from other sources including grey literature. After removal of duplicate articles, 10,954 were screened, 54 of which met the study inclusion criteria. Following the full-text eligibility assessment, 43 further articles were excluded (Additional file 1 ). The remaining 11 articles were included for critical appraisal in the systematic review (Fig. 1 ).

PRISMA flow diagram of study identification, screening, and inclusion in review. Other sources of articles refer to those identified through the Stop TB Partnership website, KNCV Tuberculosis foundation database, and the snowball method

Quality assessment

The median CCAT score for quality of studies was 24/40 (range 15–38) (Additional file 1 ). Three studies were classified as high quality [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The predominant reasons for lower quality scoring were lack of details relating to methods and study protocols including sampling frames and ethical approval.

Study characteristics

There was marked heterogeneity in the study characteristics in terms of study aims, designs, population and region/sites, and type of stigma measured (Table 1 ). The studies were conducted in low- ( n = 1) [ 27 ], middle- ( n = 9) [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ], and high-income ( n = 1) countries [ 34 ]. Two studies were conducted in the same country (Peru) [ 30 , 31 ], and these studies were linked with some overlap of study team members and co-authors. The studies were targeted at a variety of different populations including people with TB and MDR-TB and their households ( n = 5), HCWs ( n = 3), and the public ( n = 3).

Study population, aims and intervention

Six studies applied interventions targeted towards people with TB. Five of the studies aimed to improve TB treatment compliance and completion through psychosocial support interventions, which were TB clubs or support groups ( n = 3) [ 28 , 29 , 30 ], nurse support ( n = 1) [ 31 ], and household counselling ( n = 1) [ 26 ], while one study focused on improving TB knowledge [ 33 ].

TB clubs involved group meetings of people diagnosed with TB to discuss their experiences and provide mutual support to encourage each other through their illness and treatment. Other studies initiated patient-centred home visits by HCWs to complement the TB clubs [ 30 ], provided individualised emotional support from community nurses who informed and educated people with TB and their households about TB [ 31 ], and implemented a household counselling intervention delivered by nurses and trained counsellors [ 26 ]. All of the studies tailored towards people with TB captured stigma related to being diagnosed with TB. The assessment focused on measuring enacted and internalised stigma and, where possible, the influence of such stigma on TB treatment success rates. Two of the studies also involved family members of people with TB: one to evaluate stigma [ 26 ] and another to evaluate people with TB and their family members’ TB knowledge following delivery of educational videos while waiting at TB outpatient clinic appointments [ 33 ].

Two studies evaluated stigma among HCWs using workshops focused on distinct aspects of stigma [ 24 , 34 ]. One delivered nationwide TB training workshops to educate HCWs on TB, stigma and human rights to improve knowledge on TB and reduce TB-stigma towards people with TB [ 34 ]. In another, there was a focus on healthcare workers who were themselves stigmatised by other HCWs [ 24 ]. This study measured external or secondary stigma, in which HCWs experience negative attitudes or rejection because of the care they have given to people with TB.

Three studies assessed anticipated TB-Stigma among the public: two in an adult population and one in an adolescent population. All the studies measured anticipated TB-stigma using before-after intervention designs. Two studies applied health education programs in the community (mass information programs and health promotion at mass gatherings) [ 27 , 32 ]. Another study delivered training to students and evaluated whether the training reduced their levels of anticipated TB-stigma [ 25 ].

Stigma measurement tools

Eight studies used quantitative questionnaires to measure stigma (Table 2 ) [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. The format of the questionnaires to measure stigma varied widely including the number of questions asked (range 3–14 questions). Three of the questionnaires were adapted from tools that were not specific to any particular disease and had been previously validated but not among people with TB [ 28 , 29 , 34 ]. For example, Macq et al . adapted their questionnaire from the Boyd Ritsher Mental Illness stigma scale and pre-tested it 2 years before the intervention study to improve its internal validity [ 28 ]. One study piloted the tools in six different communities (four Zambian and two South African) with six different languages (Nyanja, Bemba, Tonga, isiXhosa, Afrikaans and English) [ 26 ]. Four other studies piloted their questionnaires in a single population each [ 24 , 25 , 27 , 28 , 35 ].

Most studies ( n = 7) applied the tool before and after a stigma-reduction or related intervention with the time period between the first and second application varying from 4 weeks to 18 months [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. One quantitative study did not evaluate stigma before the intervention [ 27 ]. The study was an evaluation of an extensive mass health education programme that was implemented for 2–3 years in one case study area and compared to another control study area with a limited health education programme.

Four studies used qualitative methods, such as focus group discussions, interviews and observation, to evaluate stigma [ 24 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. No studies used previously validated methods or tools to qualitatively evaluate stigma. However, the qualitative approaches focused less on measurement of stigma and more on exploring how people with TB attempted to combat the stigma perceived by themselves [ 29 ] or by other people [ 30 ], and how HCWs who work with people with TB struggled to deal with stigmatisation from other HCWs [ 24 ].

Challenges, successes, and outcomes

Implementation and delivery challenges and process indicators such as fidelity, acceptability, and feasibility were infrequently measured or reported in the studies. One study caused a positive change to national practice with the production of a manual to expand the intervention to a wider population [ 28 ]. Three studies reported that a success of the intervention was that sustainable changes had been made within the study site communities [ 26 , 29 , 33 ]. However, there was no objective way to measure or verify these changes from the data presented within the study articles.

Four of the studies explicitly stated that their intervention was limited by geographical challenges including some populations not being reached by the intervention [ 25 , 27 , 28 , 32 ]. This limited the external validity of the data. Three studies mentioned challenges concerning maintenance and sustainability of the programmes, including identifying participants to take part in the intervention and motivating people to continue engaging with the intervention [ 30 , 31 , 34 ]. Another study mentioned that inviting all HCWs to participate in a workshop about TB was problematic because hospitals were busy and understaffed [ 24 ]. The intervention itself was also challenged by issues relating to professional rank, position, and social status of different HCWs, which was perceived as limiting open discussion about the optimal ways to address stigma between HCWs (Table 3 ).

Pathways to impact of TB-stigma interventions

Synthesising learning from the interventions and outcomes, we found distinct pathways to reduce stigma depending on the population targeted by the intervention. We created a novel conceptual framework to illustrate these pathways (Fig. 2 ).

Among people with TB, stigma is a negative effect of being ill with TB, diagnosed with TB, and being on TB treatment. Stigma towards people with TB can develop in three other populations: the public, TB-related HCWs, and other HCWs. The interventions for people with TB improved TB knowledge, reduced myth and misconception related to TB, increased confidence of people with TB, and thereby reduced internalised stigma experienced by people with TB [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 ]. These effects directly supported people with TB to comply with and complete TB treatment. Another study showed that, although household counselling was not specifically designed to, or found to, reduce TB-Stigma [ 26 ], health counsellors can help households manage the consequence of TB-Stigma. The main challenge in providing household counselling, particularly in communities with high levels of TB-stigma, is that the visits themselves may trigger anticipated, internalised, or enacted stigma.

Training to TB HCWs improved the HCWs’ knowledge, attitude, and practice towards people with TB [ 34 ], which may contribute to improved TB care. Conversely, our review found that TB-related HCWs were often stigmatised by other HCWs [ 24 ]. Training HCWs who care for people with TB to educate other HCWs is likely to support dissemination of knowledge and accurate information about TB-Stigma in their workplace. Although the training failed to reduce external or secondary stigma, there was a potential spill over effect that TB-related HCWs could have used the campaign materials to educate people living in their neighbourhood.

Interventions targeted towards the general public had positive impacts on knowledge, attitudes and practice related to TB as measured by knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) and stigma scores [ 25 , 27 , 32 ]. Mass TB education to the public was expected to increase TB knowledge and remove TB misconceptions which could result in improved community attitudes and reduced stigma towards people with TB. However, the evidence found in this review suggested that misconceptions about TB persisted, even worsened, if health education through pamphlets or posters were too short and failed to convey accurate public health messages [ 32 ].

This literature review found that, despite the global importance of addressing TB-Stigma, there is a paucity of high-quality studies evaluating interventions to reduce TB-stigma. Intervention design across studies was heterogeneous, but education about TB frequently featured as a core intervention activity. Assessment of the impact of interventions on TB-stigma reduction was limited by a lack of well-validated tools to measure stigma. The novel conceptual framework highlighted that people with TB may experience stigma from three different populations around them: the public, TB HCWs, and other HCWs. The ideal and possibly most synergistic interventions to reduce TB-Stigma would be optimized by delivering interventions targeted towards more than one key populations at the same time.

There has been an increasing awareness of the importance of combatting TB-Stigma in recent years. This study may not have captured stigma-reduction interventions or programs at local, sub-national, or national levels due to such programs not being executed, evaluated, or reported systematically, which makes them difficult to review and compare. Among the limited studies identified, this review found that research on TB-stigma was often hampered by suboptimal design and methods for implementation and evaluation.

This review complements the Sommerland et al . paper[ 17 ] and extends its findings through a specific focus on the tools used to measure stigma reduction, a qualitative evaluation of the potential reasons underlying the success or failure of the interventions, and the creation of a novel conceptual framework of the pathways to intervention impact. By this approach, this review highlights that most TB-stigma intervention studies used tools that lacked appropriate validation. This finding is consistent with other published studies [ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Using reliable, validated stigma measurement tools and methods is important and helps measure stigma accurately and consistently. It also enables the comparison of impact evaluation of stigma reduction interventions across studies and contexts. There is a list of available tools that can be used and validated [ 19 ], including Van Rie’s TB-Stigma Scale [ 40 ], one of the most adapted questionnaires to assess stigma [ 38 ], which may support researchers and implementers designing TB-stigma reduction programmes in the future.

Using qualitative approaches to measure TB-stigma has both strengths and limitations. This approach cannot precisely assess the reduction of stigma after the intervention. However, it can help explore more profound dimensions of stigma and its impact on people with TB and their households. For example, qualitative studies have been able to elicit key emotional responses to TB-Stigma, including shock, fear of being isolated or abandoned by a spouse, shame related to becoming weak and incapable of working, worry relating to loneliness, and desperation related to thoughts about TB-related death [ 29 , 30 ]. Therefore, interventions incorporating mixed methods process evaluations would be both prudent and beneficial.

The conceptual framework we have generated can support understanding of the pathways through which interventions successfully reduce stigma and the parties affected. It is notable that interventions rarely have stigma-reduction as a primary aim or objective. Rather, programs often cite stigma reduction as a bridge towards TB treatment compliance, completion, and success. This may be short-sighted: besides improving treatment completion, psychosocial support is also important to prevent or alleviate anxiety, depression, and mental illness, which are well established correlates of being affected by TB [ 41 , 42 ]. Not having stigma reduction as a primary or even co-primary outcome may have contributed to a lack of focus on using validated instruments to measure stigma. Given that global TB policy strongly recommends interventions to reduce TB-stigma [ 43 , 44 ], it is vital that appropriately validated tools be used to measure stigma and that reduction of stigma be considered as a key individual-level outcome for people affected by TB.

The framework shows that the interventions on TB HCWs are also critical and may have potential spill over effects to other healthcare workers and the general public. TB HCWs often face secondary stigma and may be at risk of a psychosocial impact of TB themselves, particularly in areas with high co-prevalence of HIV/AIDS and TB [ 45 , 46 ]. TB-stigma interventions for HCWs can be challenging to implement because they may encounter power structure problems against colleagues with higher professional rank, position, and status [ 24 ]. However, HCWs are well placed to convey anti-stigma messages to their surrounding communities and should be empowered to do so.