- TEFL Internship

- TEFL Masters

- Find a TEFL Course

- Special Offers

- Course Providers

- Teach English Abroad

- Find a TEFL Job

- About DoTEFL

- Our Mission

- How DoTEFL Works

Forgotten Password

- What is Paraphrasing? An Overview With Examples

- Learn English

- James Prior

- No Comments

- Updated February 23, 2024

What is paraphrasing? Or should I say what is the definition of paraphrasing? If you want to restate something using different words whilst retaining the same meaning, this is paraphrasing.

In this article, we cover what paraphrasing is, why it’s important, and when you should do it. Plus, some benefits and examples.

Table of Contents

Paraphrase Definition: What is Paraphrasing?

Paraphrasing is when you restate the information from a source using your own words while maintaining the original meaning. It involves expressing the ideas in a different way, often to clarify or simplify the content, without directly quoting the source.

When you paraphrase, you are not only borrowing, clarifying, or expanding on the information but also ensuring that you do all of these actions without plagiarizing the original content. It’s therefore definitely worth learning how to paraphrase if you want to improve your writing skills.

Why is Paraphrasing Important?

Paraphrasing is a valuable skill that allows you to convey information in your unique writing style while still giving credit to someone else’s ideas. It’s important for several reasons, and it serves various functions in both academic and professional writing.

Here are some key reasons why you should paraphrase:

- Paraphrasing allows you to present information from sources in your own words, reducing the risk of plagiarism. Proper in-text citation is still necessary, but paraphrasing demonstrates your understanding and interpretation of the material.

- When you paraphrase, you are required to comprehend the original content fully. You actively engage with the information, helping you better understand complex concepts and ideas. This process of restating the information in your own words showcases your understanding of the subject matter.

- By paraphrasing, you can clarify complex ideas or technical language and convey information in a clearer, shorter, and simpler form. This makes it more accessible to your audience and ensures they grasp the key points. This is particularly important when communicating with readers who may not be familiar with specialized terminology.

- Paraphrasing is valuable when synthesizing information from various sources. It enables you to blend ideas cohesively while maintaining a consistent writing style throughout your work.

- Paraphrasing allows you to inject your unique writing style and voice into the content. It helps you present information in a way that is more aligned with your personal expression and perspective.

- In certain situations where you need to meet specific length requirements for assignments or publications, paraphrasing allows you to convey information more concisely while still preserving the essential meaning.

- Paraphrasing helps maintain a smooth flow and cohesiveness in your writing. It allows you to integrate information seamlessly, avoiding abrupt shifts between your own ideas and those from external sources.

- Depending on your audience, you may need to adapt the language and level of technicality of the information you present. Paraphrasing allows you to tailor the content to suit the needs of your specific readership.

Incorporating paraphrasing into your writing not only showcases your understanding of the material but also enhances the overall quality and originality of your work.

When Should You Paraphrase?

Knowing when to paraphrase is an important skill, especially in academic writing and professional communication. Here are some situations in which you should consider paraphrasing:

- To Avoid Plagiarism: Whenever you want to incorporate information from source material into your own work, but don’t want to use a direct quotation, paraphrasing is necessary to present the ideas in your own words while still acknowledging the original source.

- To Express Understanding: Paraphrasing demonstrates your understanding of a topic by rephrasing the information in a way that shows you have processed and comprehended the material.

- To Simplify Complex Information: If you encounter complex or technical language that may be difficult for your audience to understand, paraphrasing can help you clarify and simplify the information to make it more accessible and digestible.

- To Integrate Multiple Sources: When synthesizing information from multiple sources, paraphrasing allows you to blend the ideas cohesively while maintaining your own voice and perspective.

- To Maintain Consistency in Writing Style: In academic writing or professional writing, paraphrasing can help you maintain a consistent writing style throughout your work. This helps to ensure that all sections flow smoothly and are coherent.

- To Meet Specific Requirements: Some assignments or publications may have specific requirements. This could relate to the number of words or concern the use of direct quotations. In such cases, paraphrasing allows you to meet these requirements while still incorporating relevant information from your sources.

What Are the Benefits of Paraphrasing?

Rewriting information in a clearer, shorter, and simpler form is called paraphrasing, so one of the benefits of paraphrasing is already clear! However, it can also be a useful exercise for other reasons, which are outlined below:

Avoiding Plagiarism

One of the main benefits of paraphrasing is mastering the ability to present information from external sources in a way that is entirely your own. By restructuring the content and expressing it using your words, you create a distinct piece of writing that reflects your comprehension and interpretation of the original material. This not only showcases your academic or professional integrity but also safeguards against unintentional plagiarism.

Paraphrasing is a fundamental skill in academic and professional settings, where originality and proper attribution are highly valued. This is especially true when it comes to writing research papers, where you’ll often need to reference someone else’s ideas with appropriate citations.

When you paraphrase effectively, you communicate to your audience that you respect the intellectual property of others while contributing your unique insights. This ethical approach to information usage enhances your credibility as a writer or researcher and reinforces the integrity of your work.

Enhancing Understanding

When you engage in paraphrasing, you actively participate in the material you are working with. You are forced to consider the ideas presented in the source material. You need to discern the essential concepts, identify key phrases, and decide how best to convey the message in a way that resonates with you.

This active engagement not only aids in understanding the content but also encourages critical thinking as you evaluate and interpret the information from your own standpoint.

By expressing someone else’s ideas in your own words, you deepen your understanding of the content. This process requires you to dissect the original text, grasp its nuances, and then reconstruct it using your language and perspective. In this way, you go beyond mere memorization and truly internalize the information, fostering a more profound comprehension of the subject matter.

Tailoring Information for Your Audience

Paraphrasing empowers you to adapt the language and complexity of the information to suit the needs and understanding of your audience. As you rephrase the content, you have the flexibility to adjust the level of technicality, simplify complex terminology, or tailor the tone to make the information more accessible to your specific readership.

Consider your audience’s background, knowledge level, and interests. Paraphrasing allows you to bridge the gap between the original content and the understanding of your intended audience.

Whether you are communicating with experts in a particular field or a general audience, the ability to paraphrase ensures that the information is conveyed in a way that resonates with and is comprehensible to your readers. This skill not only facilitates effective communication but also demonstrates your awareness of the diverse needs of your audience.

Improves Writing Skills

Paraphrasing helps in the development and refinement of your writing skills. When you actively engage in the process of rephrasing someone else’s ideas, you hone your ability to express concepts in a clear, concise, and coherent manner.

This practice refines your language proficiency, encouraging you to explore different types of sentence structure, experiment with vocabulary, and ultimately develop a more sophisticated and nuanced writing style.

As you paraphrase, you gain a heightened awareness of grammar, syntax, and word choice. This translates into improved writing, helping you construct well-articulated sentences and paragraphs. Moreover, paraphrasing allows you to experiment with different writing tones and adapt your style to suit the context or purpose of your writing, fostering versatility and adaptability in your expression.

Saves Time and Energy

Paraphrasing can significantly reduce the time and energy spent on the writing process. Rather than grappling with the challenge of integrating lengthy direct quotations or struggling to find the perfect synonym, paraphrasing allows you to distill and convey information in a more streamlined way.

This becomes particularly advantageous when faced with strict deadlines. By mastering paraphrasing, you empower yourself to produce well-crafted, original content in a shorter timeframe, allowing you to meet deadlines without compromising the quality of your work.

Examples of Paraphrasing

Here are some examples of paraphrasing:

- Original: “The advancements in technology have revolutionized the way we communicate with each other.”

- Paraphrased: “Technological progress has transformed how we interact and communicate with one another.”

- Original: “Deforestation poses a significant threat to global ecosystems and biodiversity.”

- Paraphrased: “The impact of deforestation represents a substantial danger to ecosystems and the diversity of life on a global scale.”

- Original: “Effective time management is essential for achieving productivity in both professional and personal spheres.”

- Paraphrased: “Efficient management of time is crucial for attaining productivity in both professional and personal aspects of life.”

- Original: “The restaurant offers a diverse selection of culinary choices, ranging from traditional dishes to modern fusion cuisine.”

- Paraphrased: “The restaurant provides a variety of food options, including both traditional and modern fusion dishes.”

- Original: “The novel explores the complexities of human relationships in a rapidly changing society.”

- Paraphrased: “The book delves into the challenges of human connections in a fast-changing world.”

- Original: “Regular exercise is crucial for maintaining optimal physical health and preventing various health issues.”

- Paraphrased: “Exercising regularly is important for keeping your body healthy and avoiding health problems.”

In these examples, you can observe the use of different wording, sentence structure, and synonyms while preserving the core meaning of the original sentences. This is the essence of paraphrasing.

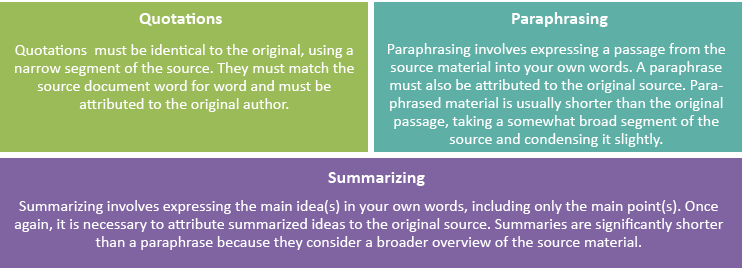

What Are the Differences Between Paraphrasing, Quoting, and Summarizing?

So, we’ve established that successful paraphrasing is a way of rewriting someone else’s words whilst retaining their meaning and still giving credit to the original author’s ideas. But how is this different from quoting and summarizing?

While paraphrasing, quoting, and summarizing are all ways of incorporating information from source material into your own writing, there are key differences between them:

Paraphrasing

- Definition: Paraphrasing involves rephrasing someone else’s ideas or information in your own words while retaining the original meaning.

- Usage: You use paraphrasing when you want to present the information in a way that suits your writing style or when you need to clarify complex ideas.

- Example: Original: “The study found a significant correlation between sleep deprivation and decreased cognitive performance.” Paraphrased: “The research indicated a notable link between lack of sleep and a decline in cognitive function.”

- Definition: Quoting involves directly using the exact words from a source and enclosing them in quotation marks.

- Usage: You use quoting when the original wording is essential, either because of its precision or uniqueness, or when you want to highlight a specific phrase or concept.

- Example: Original: “The author argues, ‘In the absence of clear guidelines, individual judgment becomes paramount in decision-making.'”

The use of quotation marks is vital when quoting.

Summarizing

- Definition: Summarizing involves condensing the main ideas of a source or original passage in your own words, focusing on the most crucial points.

- Usage: You use summarizing when you need to provide a concise overview of a longer piece of text or when you want to capture the key points without including all the details.

- Example: Original: A lengthy article discussing various factors influencing climate change. Summary: “The article outlines key factors contributing to climate change, including human activities and natural processes.”

In summary, paraphrasing is about expressing someone else’s ideas in your own words, quoting involves directly using the original words, and summarizing is about condensing the main points of a source.

Each technique serves different purposes in writing and should be used based on your specific goals and the nature of the information you are incorporating. If you want to level up your writing skills you need to be able to do all three of these.

Conclusion (In Our Own Words)

Paraphrasing is a valuable skill with numerous benefits. It helps you understand complex ideas, refine your writing style, and demonstrate ethical information use. It also allows you to tailor information for different audiences and can save time in academic and professional writing.

So, if you want to incorporate information from external sources into your writing in a way that is clear, concise, and respectful of the original author’s work, it’s worth mastering the art of paraphrasing.

- Recent Posts

- 113+ American Slang Words & Phrases With Examples - May 29, 2024

- 11 Best Business English Courses Online - May 29, 2024

- How to Teach Business English - May 27, 2024

More from DoTEFL

11 of the Best English Learning Apps For English Learners

- Updated January 8, 2024

11 Reasons Why You Should Take a TEFL Course Abroad

- Updated January 15, 2024

TEFL Level 3, TEFL Level 5 or TEFL Level 7: Which One Is Right for You?

- Updated November 2, 2023

Welcome Aboard vs Welcome On Board – What’s the Difference?

- Updated February 13, 2024

Teach English Online: Your Guide to Getting Started

- Updated November 1, 2023

Sports Idioms & Expressions With Their Meanings & Examples

- The global TEFL course directory.

What is the difference between paraphrasing & summarizing

Differences between paraphrasing & summarizing, definition and purpose.

Paraphrasing involves rewriting someone else's ideas or a specific text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning and often keeping a similar length to the source material. The primary purpose of paraphrasing is to use another person's ideas in your work without resorting to a direct quotation, thereby showing your understanding of the source while integrating it smoothly into your own narrative.

Summarizing , on the other hand, is the process of distilling a longer piece of text down to its essential points, significantly reducing its length. The goal of summarizing is to provide a broad overview of the source material, capturing only the main ideas in a concise manner, which helps in clarifying the overall theme or argument of the text for the reader.

Detail and Length

The level of detail and the length of the text are key differences between paraphrasing and summarizing. Paraphrasing retains a level of detail similar to the original text, and the paraphrased passage is typically about the same length or slightly shorter than the source. This approach is suitable when specific details or points from the source are necessary to understand the reader in the context of your work.

In contrast, summarizing significantly reduces the length of the original text, focusing only on the central themes or main ideas. This makes summaries particularly useful for giving an overview of long texts, such as books, articles, or comprehensive reports, where only the core message is needed.

Usage in Academic Writing

Both paraphrasing and summarizing are crucial skills in academic writing. They help one effectively incorporate the ideas of others into one's work. Paraphrasing is often preferred when specific evidence or a detailed understanding of the source is required to support one's argument without overusing direct quotes, which can clutter the text and disrupt the flow of the narrative.

Summarizing is a time-saving and efficient strategy when referring to broader concepts or discussing a source's general scope. It's particularly useful during literature reviews or when providing background information where detailed support is unnecessary. Allowing you to succinctly conveys the essence of a sourcerelieves you from overwhelming your readers with unnecessary details while still ensuring they grasp the relevance of the referenced works.

In summary, choosing between paraphrasing and summarizing depends mainly on the writer's intent, the importance of the details in the source material, and how they wish to integrate this information into their own writing.

How to paraphrase in a few steps

Paraphrasing refers to rewriting content in our own words while keeping the original meaning. Here are some steps and tips for effective paraphrasing:

Reading & Understanding the content

Ensure you fully understand the meaning of the text while identifying the essential concepts.

Taking Notes

Write the main ideas without looking at the original text.

Using Synonyms

This step involves replacing words with relevant synonyms; keeping some technical words that can't be replaced is essential.

Changing Sentence Structure

Alter the sentence structure, such as changing active to passive voice or shortening long sentences.

Rephrasing Concepts

Explain the concepts differently, using your own words and style.

Comparing with the original content

Ensure your paraphrased version accurately reflects the original meaning and is not too similar.

Cite the Source

It's essential to credit the source even when paraphrased.

- The original text:

Students frequently overuse direct quotations in taking notes, and as a result, they overuse quotations in the final [research] paper. Probably only about 10% of your final manuscript should appear as a directly quoted matter. Therefore, you should strive to limit the exact transcribing of source materials while taking notes. Lester, James D. Writing Research Papers. 2nd ed., 1976, pp. 46-47.

- The paraphrased text:

In research papers, students often quote excessively, failing to keep quoted material down to a desirable level. Since the problem usually originates during note-taking, it is essential to minimize the material recorded verbatim (Lester 46-47).

Here are some tips to paraphrase:

- Avoid Plagiarism: Don’t copy the text verbatim without quotation marks and proper attribution.

- Maintain Original Meaning: Ensure the paraphrased text conveys the same message as the original.

- Use a Different Structure: Change the information order and rephrase sentences.

- Simplify the Language: Use more straightforward language to make the text more understandable, if appropriate.

Common paraphrasing mistakes

- Not changing enough to avoid plagiarism

One of the most complex parts of paraphrasing a sentence is changing enough to avoid copying and not lose the original meaning. This can be a tricky balancing act, especially if you have to keep some of the wording.

- Distorting the meaning

Likewise, changing the words and sentence structure can accidentally change the meaning. That’s fine if you want to write an original sentence, but if you’re trying to convey someone else’s idea, it's best to rewrite and adequately describe it.

Review your paraphrase to confirm that all the words are correctly used and placed in the correct order for your intended meaning. If unsure, you can ask someone to read the passage to see how they interpret it.

- Forgetting the citation

Some people think that if you put an idea into your own words, you don’t need to cite where it came from—but that’s not true. Even if the wording is your own, the ideas are not. That means you need a citation.

If you have many paraphrased sentences from the exact location in a source, you need only one citation at the end of the passage. Otherwise, you need a citation for each paraphrased sentence from another source in your writing, without exception.

How to summarize in a few steps

Focusing on the main ideas.

Read through the entire piece you want to summarize and identify the most important concepts and themes. Ignore minor details and examples. Focus on capturing the essence of the critical ideas.

If it's an article or book, read introductions, headings, and conclusions to understand the central themes. As you read, ask yourself, "What is the author trying to convey here?" to determine what's most significant.

Keeping it short and straightforward

A summary should be considerably shorter than the original work. Aim for about 1/3 of the length or less. Be concise by eliminating unnecessary words and rephrasing ideas efficiently. Use sentence fragments and bulleted lists when possible.

Maintaining objectivity

Summarize the work factually without putting your own personal spin or opinions on the information. Report the key ideas in an impartial, balanced manner. Do not make judgments about the quality or accuracy of the content.

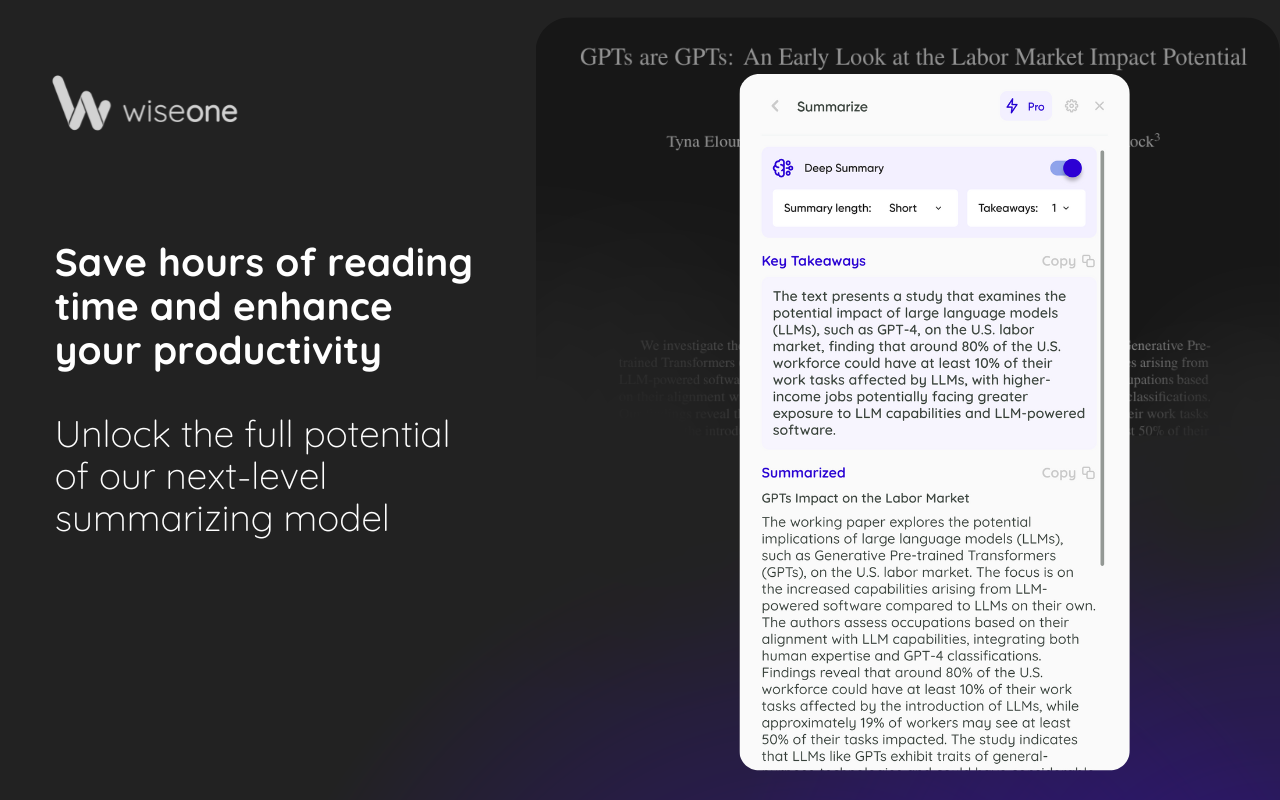

Using a summarizing tool

As AI continues gaining popularity, leveraging dedicated to benefit from their advantage is essential.

Among these tools lies Wiseone , an innovative AI tool that transforms how we read and search for information online.

Wiseone's "Summarize" feature allows you to understand the main points of an article or a PDF document efficiently without the need to read the entire piece by generating thorough summaries with key takeaways.

Don’ts of paragraph summarization

Similarly, keep these in mind as things to avoid:

- Plagiarizing the original paragraph. It’s perfectly fine to include direct quotes, but if you do, cite them properly. However, most of the summary should be in your own words.

- Paraphrasing rather than summarizing. Here’s a way to think of the difference: a summary is a “highlight reel,” and paraphrasing condenses the entire paragraph.

- Omitting key information. When summarizing a paragraph, you might need to mention information from its preceding or following paragraphs, or even other sections from the original work, to give the reader appropriate context for the other information included in the summary.

What is paraphrasing?

What is summarizing.

Summarizing is the process of distilling a longer text down to its essential points, significantly reducing its length. The goal of summarizing is to provide a broad overview of the source material, capturing only the main ideas in a concise manner, which helps in clarifying the overall theme or argument of the text for the reader.

What are the steps to paraphrase?

- Reading & Understanding the content: Ensure you fully understand the meaning of the text while identifying the essential concepts.

- Taking Notes: Write the main ideas without looking at the original text.

- Using Synonyms: This step involves replacing words with relevant synonyms; keeping some technical words that can't be replaced is essential.

- Changing Sentence Structure: Alter the sentence structure, such as changing active to passive voice or shortening long sentences.

- Rephrasing Concepts: Explain the concepts differently, using your own words and style.

- Comparing with the original content: Ensure your paraphrased version accurately reflects the original meaning and is not too similar.

- Cite the Source: It's essential to credit the source even when paraphrased.

What are some tips to paraphrase?

What are the common paraphrasing mistakes.

- Not changing enough to avoid plagiarism: One of the most complex parts of paraphrasing a sentence is changing enough to avoid copying and not lose the original meaning. This can be a tricky balancing act, especially if you have to keep some of the wording.

- Distorting the meaning: Changing the words and sentence structure can accidentally change the meaning. That’s fine if you want to write an original sentence, but if you’re trying to convey someone else’s idea, it's best to rewrite and adequately describe it. Review your paraphrase to confirm that all the words are correctly used and placed in the correct order for your intended meaning. If unsure, you can ask someone to read the passage to see how they interpret it.

- Forgetting the citation: Some people think that if you put an idea into your own words, you don’t need to cite where it came from—but that’s not true. Even if the wording is your own, the ideas are not. That means you need a citation.

What are the steps to summarize content?

- Focusing on the main ideas : Read through the entire piece you want to summarize and identify the most important concepts and themes. Ignore minor details and examples. Focus on capturing the essence of the critical ideas. If it's an article or book, read introductions, headings, and conclusions to understand the central themes. As you read, ask yourself, "What is the author trying to convey here?" to determine what's most significant.

- Keeping it short and straightforward: A summary should be shorter than the original work. Aim for about 1/3 of the length or less. Be concise by eliminating unnecessary words and rephrasing ideas efficiently. Use sentence fragments and bulleted lists when possible.

- Maintaining objectivity: Summarize the work factually without putting your own personal spin or opinions on the information. Report the key ideas in an impartial, balanced manner. Do not make judgments about the quality or accuracy of the content.

Enhance your web search, Boost your reading productivity with Wiseone

Our content is reader-supported. Things you buy through links on our site may earn us a commission

Join our newsletter

Never miss out on well-researched articles in your field of interest with our weekly newsletter.

- Project Management

- Starting a business

Get the latest Business News

Mastering communication: paraphrasing and summarizing skills.

Two very useful skills in communicating with others, including when coaching and facilitating, are paraphrasing and summarizing the thoughts of others.

How to Paraphrase When Communicating and Coaching With Others

Paraphrasing is repeating in your words what you interpreted someone else to be saying. Paraphrasing is powerful means to further the understanding of the other person and yourself, and can greatly increase the impact of another’s comments. It can translate comments so that even more people can understand them. When paraphrasing:

- Put the focus of the paraphrase on what the other person implied, not on what you wanted him/her to imply, e.g., don’t say, “I believe what you meant to say was …”. Instead, say “If I’m hearing you right, you conveyed that …?”

- Phrase the paraphrase as a question, “So you’re saying that …?”, so that the other person has the responsibility and opportunity to refine his/her original comments in response to your question.

- Put the focus of the paraphrase on the other person, e.g., if the person said, “I don’t get enough resources to do what I want,” then don’t paraphrase, “We probably all don’t get what we want, right?”

- Put the ownership of the paraphrase on yourself, e.g., “If I’m hearing you right …?” or “If I understand you correctly …?”

- Put the ownership of the other person’s words on him/her, e.g., say “If I understand you right, you’re saying that …?” or “… you believe that …?” or “… you feel that …?”

- In the paraphrase, use some of the words that the other person used. For example, if the other person said, “I think we should do more planning around here.” You might paraphrase, “If I’m hearing you right in this strategic planning workshop, you believe that more strategic planning should be done in our community?”

- Don’t judge or evaluate the other person’s comments, e.g., don’t say, “I wonder if you really believe that?” or “Don’t you feel out-on-a-limb making that comment?”

- You can use a paraphrase to validate your impression of the other’s comments, e.g., you could say, “So you were frustrated when …?”

- The paraphrase should be shorter than the original comments made by the other person.

- If the other person responds to your paraphrase that you still don’t understand him/her, then give the other person 1-2 chances to restate his position. Then you might cease the paraphrasing; otherwise, you might embarrass or provoke the other person.

How to Effectively Summarize

A summary is a concise overview of the most important points from a communication, whether it’s from a conversation, presentation or document. Summarizing is a very important skill for an effective communicator.

A good summary can verify that people are understanding each other, can make communications more efficient, and can ensure that the highlights of communications are captured and utilized.

When summarizing, consider the following guidelines:

- When listening or reading, look for the main ideas being conveyed.

- Look for any one major point that comes from the communication. What is the person trying to accomplish in the communication?

- Organize the main ideas, either just in your mind or written down.

- Write a summary that lists and organizes the main ideas, along with the major point of the communicator.

- The summary should always be shorter than the original communication.

- Does not introduce any new main points into the summary – if you do, make it clear that you’re adding them.

- If possible, have other readers or listeners also read your summary and tell you if it is understandable, accurate and complete.

For many related, free online resources, see the following Free Management Library’s topics:

- All About Personal and Professional Coaching

- Communications Skills

- Skills in Questioning

- Team Building

- LinkedIn Discussion Group about “Coaching for Everyone”

————————————————————————-

Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD – Authenticity Consulting, LLC – 763-971-8890 Read my blogs: Boards , Consulting and OD , and Strategic Planning .

Carter McNamara

How to Start Your Private Peer Coaching Group

Introduction Purpose of This Information The following information and resources are focused on the most important guidelines and materials for you to develop a basic, practical, and successful PCG. The information is intended for anyone, although it helps if you have at least some basic experience in working with groups. All aspects of this offering …

What Makes for An Effective Leader?

© Copyright Sandra Larson, Minneapolis, MN. Sandra Larson, previous executive director of MAP for Nonprofits, was once asked to write her thoughts on what makes an effective leader. Her thoughts are shared here to gel other leaders to articulate their own thoughts on what makes them a good leader. Also consider Related Library Topics Passion …

How to Design Leadership Training Development Programs

Written by Carter McNamara, MBA, Ph.D., Authenticity Consulting, LLC. Copyright; Authenticity Consulting, LLC (Note that there are separate topics about How to Design Your Management Development Program and How to Design Your Supervisor Development Program. Those two topics are very similar to this topic about leadership training programs, but with a different focus.) Sections of …

What is the One Best Model of Group Coaching?

Group and team coaching are fast becoming a major approach in helping more organizations and individuals to benefit from the power of coaching. There are numerous benefits, including that it can spread core coaching more quickly, be less expensive than one-on-one coaching, provide more diverse perspectives in coaching, and share support and accountabilities to get …

Avoiding Confusion in Learning and Development Conversations

It’s fascinating how two people can be talking about groups and individuals in almost any form of learning and development, but be talking about very different things. You can sense their confusion and frustration. Here’s a handy tip that we all used in a three-day, peer coaching group workshop in the Kansas Leadership Center, and …

Reflections on the Question: “Is it Group or Team Coaching?”

I started my first coaching groups in 1983 and since then, have worked with 100s of groups and taught hundreds of others how do design and coach/facilitate the groups. I’ve also read much of the literature about group and team coaching. Here are some of my lessons learned — sometimes painfully. 1. The most important …

Single-Project and Multi-Project Formats of Action Learning

In the early 1980s, I started facilitating Action Learning where all set members were working on the same problem or project (single-project Action Learning, or SPAL). My bias in Action Learning has always been to cultivate self-facilitated groups, somewhat in the spirit of Reginald Revans’ preferences for those kinds of sets, too. However, at least …

The Applications of Group Coaching - Part 2

In Part 1, we described group coaching, starting with a description of coaching and then group coaching. We also listed many powerful applications of group coaching. Basic Considerations in Designing Group Coaching It is very important to customize the design of group coaching to the specific way that you want to use it. There are …

6 Steps to Resolving a Level 1 Disagreement

A disagreement arises in a meeting you are facilitating. This is an inevitable scenario in many types of meetings where a group needs to come to critical decisions - such as strategic planning or issue resolution sessions. How do you - the person in the room responsible for building consensus - resolve it without breaking group dynamics or creating a tense environment of division? It's a tough job, but you can (and need to) do it. Here's one way to resolve the disagreement.

Empowering Action Learners and Coaches: Free Online Resources

(The aim of this blog has always been to provide highly practical guidelines, tools and techniques for all types of Action Learners and coaches. Here are links to some of the world’s largest collections of free, well-organized resources for practitioners in both fields.) The Action Learning framework and the field of personal and professional coaching …

Action Learning Certification: Exploring Independent Standards

The field of personal and professional coaching has a widely respected and accepted, independent certifying body called the International Coach Federation. It is independent in that it does not concurrently promote its own model of coaching — it does not engage in that kind of conflict of interest. There seems to be a mistaken impression …

Effective Recording Techniques: Capturing Information

As a meeting facilitator, you must employ several techniques for recording information in a session to make it a manageable process. When you are gathering input, ideas, and issues from your group at warp speed, it will inevitably be challenging and tedious. Here are a few methods to make the process easier.

What March Madness teaches us about facilitation

Here we go. It's now down to the Final Four in this year's NCAA March Madness. As I analyze the four remaining teams and highlights of their seasons (and take a look at my butchered bracket!), I think about how March Madness and - more importantly - the game of basketball really does embody what we know about facilitation. Let's consider that thought for these reasons.

What kind of a Tough Leader are you?

Alan Frohman Articles, books and experience identify at least two types of tough leaders. Each is demanding, but in very different ways. The first type is described in these terms: Critical Judgmental Lacks compassion Micromanaging Disrespectful They rarely view themselves that way. But that is how their people describe them. They see themselves as being …

6 Things You’ll Hear in an Unprepared Meeting

Many times, we, as facilitators, are not prepared (or ill prepared) for meetings, and that leads to some horrific results – including those feelings you experienced while watching a fellow facilitator suffer through a meeting. What are some things you'll hear in an unprepared meeting? Look out for these words. And, don't let this happen to you.

Privacy Overview

Paraphrasing vs. Summarizing (Differences, Examples, How To)

It can be confusing to know when to paraphrase and when to summarize. Many people use the terms interchangeably even though the two have different meanings and uses.

Today, let’s understand the basic differences between paraphrasing vs. summarizing and when to use which . We’ll also look at types and examples of paraphrasing and summarizing, as well as how to do both effectively.

Let’s look at paraphrasing first.

What is paraphrasing?

It refers to rewriting someone else’s ideas in your own words.

It’s important to rewrite the whole idea in your words rather than just replacing a few words with their synonyms. That way, you present an idea in a way that your audience will understand easily and also avoid plagiarism.

It’s also important to cite your sources when paraphrasing so that the original author of the work gets due credit.

When should you paraphrase?

The main purpose of paraphrasing is often to clarify an existing passage. You should use paraphrasing when you want to show that you understand the concept, like while writing an essay about a specific topic.

You may also use it when you’re quoting someone but can’t remember their exact words.

Finally, paraphrasing is a very effective way to rewrite outdated content in a way that’s relevant to your current audience.

How to paraphrase effectively

Follow these steps to paraphrase any piece of text effectively:

- Read the full text and ensure that you understand it completely. It helps to look up words you don’t fully understand in an online or offline dictionary.

- Once you understand the text, rewrite it in your own words. Remember to rewrite it instead of just substituting words with their synonyms.

- Edit the text to ensure it’s easy to understand for your audience.

- Mix in your own insights while rewriting the text to make it more relevant.

- Run the text through a plagiarism checker to ensure that it does not have any of the original content.

Example of paraphrasing

Here’s an example of paraphrasing:

- Original: The national park is full of trees, water bodies, and various species of flora and fauna.

- Paraphrased: Many animal species thrive in the verdant national park that is served by lakes and rivers flowing through it.

What is summarizing?

Summarizing is also based on someone else’s text but rather than presenting their ideas in your words, you only sum up their main ideas in a smaller piece of text.

It’s important to not use their exact words or phrases when summarizing to avoid plagiarism. It’s best to make your own notes while reading through the text and writing a summary based on your notes.

You must only summarize the most important ideas from a piece of text as summaries are essentially very short compared to the original work. And just like paraphrasing, you should cite the original text as a reference.

When should you summarize?

The main purpose of summarizing is to reduce a passage or other text to fewer words while ensuring that everything important is covered.

Summaries are useful when you want to cut to the chase and lay down the most important points from a piece of text or convey the entire message in fewer words. You should summarize when you have to write a short essay about a larger piece of text, such as writing a book review.

You can also summarize when you want to provide background information about something without taking up too much space.

How to summarize effectively

Follow these steps to summarize any prose effectively:

- Read the text to fully understand it. It helps to read it a few times instead of just going through it once.

- Pay attention to the larger theme of the text rather than trying to rewrite it sentence for sentence.

- Understand how all the main ideas are linked and piece them together to form an overview.

- Remove all the information that’s not crucial to the main ideas or theme. Remember, summaries must only include the most essential points and information.

- Edit your overview to ensure that the information is organized logically and follows the correct chronology where applicable.

- Review and edit the summary again to make it clearer, ensure that it’s accurate, and make it even more concise where you can.

- Ensure that you cite the original text.

Example of summarization

You can summarize any text into a shorter version. For example, this entire article can be summarized in just a few sentences as follows:

- Summary: The article discusses paraphrasing vs. summarizing by explaining the two concepts. It specifies when you should use paraphrasing and when you should summarize a piece of text and describes the process of each. It ends with examples of both paraphrasing and summarizing to provide a better understanding to the reader.

Paraphrasing vs. summarizing has been a long-standing point of confusion for writers of all levels, whether you’re writing a college essay or reviewing a research paper or book. The above tips and examples can help you identify when to use paraphrasing or summarizing and how to go about them effectively.

Inside this article

Fact checked: Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

About the author

Dalia Y.: Dalia is an English Major and linguistics expert with an additional degree in Psychology. Dalia has featured articles on Forbes, Inc, Fast Company, Grammarly, and many more. She covers English, ESL, and all things grammar on GrammarBrain.

Core lessons

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Active Sentence

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Body Paragraph

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- Equivocation Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Gerund Phrase

- Genitive Case

- Helping Verb

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Indicative Mood

- Juxtaposition

- Linking Verb

- Misplaced Modifier

- Nominative Case

- Noun Adjective

- Object Pronoun

- Object Complement

- Order of Adjectives

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Persuasive Writing

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Quotation Marks

- Relative Pronoun

- Reflexive Pronoun

- Reciprocal Pronoun

- Subordinating Conjunction

- Simple Future Tense

- Stative Verb

- Subjunctive

- Subject Complement

- Subject of a Sentence

- Sentence Variety

- Second Conditional

- Superlative Adjective

- Slash Symbol

- Topic Sentence

- Types of Nouns

- Types of Sentences

- Uncountable Noun

- Vowels and Consonants

Popular lessons

Stay awhile. Your weekly dose of grammar and English fun.

The world's best online resource for learning English. Understand words, phrases, slang terms, and all other variations of the English language.

- Abbreviations

- Editorial Policy

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 12 min read

How to Paraphrase and Summarize Work

Summing up key ideas in your own words.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Imagine you're preparing a presentation for your CEO. You asked everyone in your team to contribute, and they all had plenty to say!

But now you have a dozen reports, all in different styles, and your CEO says that she can spare only 10 minutes to read the final version. What do you do?

The solution is to paraphrase and summarize the reports, so your boss gets only the key information that she needs, in a form that she can process quickly.

In this article, we explain how to paraphrase and how to summarize, and how to apply these techniques to text and the spoken word. We also explore the differences between the two skills, and point out the pitfalls to avoid.

What Is Paraphrasing?

When you paraphrase, you use your own words to express something that was written or said by another person.

Putting it into your own words can clarify the message, make it more relevant to your audience , or give it greater impact.

You might use paraphrased material to support your own argument or viewpoint. Or, if you're putting together a report , presentation or speech , you can use paraphrasing to maintain a consistent style, and to avoid lengthy quotations from the original text or conversation.

Paraphrased material should keep its original meaning and (approximate) length, but you can use it to pick out a single point from a longer discussion.

What Is Summarizing?

In contrast, a summary is a brief overview of an entire discussion or argument. You might summarize a whole research paper or conversation in a single paragraph, for example, or with a series of bullet points, using your own words and style.

People often summarize when the original material is long, or to emphasize key facts or points. Summaries leave out detail or examples that may distract the reader from the most important information, and they simplify complex arguments, grammar and vocabulary.

Used correctly, summarizing and paraphrasing can save time, increase understanding, and give authority and credibility to your work. Both tools are useful when the precise wording of the original communication is less important than its overall meaning.

How to Paraphrase Text

To paraphrase text, follow these four steps:

1. Read and Make Notes

Carefully read the text that you want to paraphrase. Highlight, underline or note down important terms and phrases that you need to remember.

2. Find Different Terms

Find equivalent words or phrases (synonyms) to use in place of the ones that you've picked out. A dictionary, thesaurus or online search can be useful here, but take care to preserve the meaning of the original text, particularly if you're dealing with technical or scientific terms.

3. Put the Text into Your Own Words

Rewrite the original text, line by line. Simplify the grammar and vocabulary, adjust the order of the words and sentences, and replace "passive" expressions with "active" ones (for example, you could change "The new supplier was contacted by Nusrat" to "Nusrat contacted the new supplier").

Remove complex clauses, and break longer sentences into shorter ones. All of this will make your new version easier to understand .

4. Check Your Work

Check your work by comparing it to the original. Your paraphrase should be clear and simple, and written in your own words. It may be shorter, but it should include all of the necessary detail.

Paraphrasing: an Example

Despite the undoubted fact that everyone's vision of what constitutes success is different, one should spend one's time establishing and finalizing one's personal vision of it. Otherwise, how can you possibly understand what your final destination might be, or whether or not your decisions are assisting you in moving in the direction of the goals which you've set yourself?

The two kinds of statement – mission and vision – can be invaluable to your approach, aiding you, as they do, in focusing on your primary goal, and quickly identifying possibilities that you might wish to exploit and explore.

We all have different ideas about success. What's important is that you spend time defining your version of success. That way, you'll understand what you should be working toward. You'll also know if your decisions are helping you to move toward your goals.

Used as part of your personal approach to goal-setting, mission and vision statements are useful for bringing sharp focus to your most important goal, and for helping you to quickly identify which opportunities you should pursue.

How to Paraphrase Speech

In a conversation – a meeting or coaching session, for example – paraphrasing is a good way to make sure that you have correctly understood what the other person has said.

This requires two additional skills: active listening and asking the right questions .

Useful questions include:

- If I hear you correctly, you're saying that…?

- So you mean that…? Is that right?

- Did I understand you when you said that…?

You can use questions like these to repeat the speaker's words back to them. For instance, if the person says, "We just don't have the funds available for these projects," you could reply: "If I understand you correctly, you're saying that our organization can't afford to pay for my team's projects?"

This may seem repetitive, but it gives the speaker the opportunity to highlight any misunderstandings, or to clarify their position.

When you're paraphrasing conversations in this way, take care not to introduce new ideas or information, and not to make judgments on what the other person has said, or to "spin" their words toward what you want to hear. Instead, simply restate their position as you understand it.

Sometimes, you may need to paraphrase a speech or a presentation. Perhaps you want to report back to your team, or write about it in a company blog, for example.

In these cases it's a good idea to make summary notes as you listen, and to work them up into a paraphrase later. (See How to Summarize Text or Speech, below.)

How to Summarize Text or Speech

Follow steps 1-5 below to summarize text. To summarize spoken material – a speech, a meeting, or a presentation, for example – start at step three.

1. Get a General Idea of the Original

First, speed read the text that you're summarizing to get a general impression of its content. Pay particular attention to the title, introduction, conclusion, and the headings and subheadings.

2. Check Your Understanding

Build your comprehension of the text by reading it again more carefully. Check that your initial interpretation of the content was correct.

3. Make Notes

Take notes on what you're reading or listening to. Use bullet points, and introduce each bullet with a key word or idea. Write down only one point or idea for each bullet.

If you're summarizing spoken material, you may not have much time on each point before the speaker moves on. If you can, obtain a meeting agenda, a copy of the presentation, or a transcript of the speech in advance, so you know what's coming.

Make sure your notes are concise, well-ordered, and include only the points that really matter.

The Cornell Note-Taking System is an effective way to organize your notes as you write them, so that you can easily identify key points and actions later. Our article, Writing Meeting Notes , also contains plenty of useful advice.

4. Write Your Summary

Bullet points or numbered lists are often an acceptable format for summaries – for example, on presentation slides, in the minutes of a meeting, or in Key Points sections like the one at the end of this article.

However, don't just use the bulleted notes that you took in step 3. They'll likely need editing or "polishing" if you want other people to understand them.

Some summaries, such as research paper abstracts, press releases, and marketing copy, require continuous prose. If this is the case, write your summary as a paragraph, turning each bullet point into a full sentence.

Aim to use only your own notes, and refer to original documents or recordings only if you really need to. This helps to ensure that you use your own words.

If you're summarizing speech, do so as soon as possible after the event, while it's still fresh in your mind.

5. Check Your Work

Your summary should be a brief but informative outline of the original. Check that you've expressed all of the most important points in your own words, and that you've left out any unnecessary detail.

Summarizing: an Example

So how do you go about identifying your strengths and weaknesses, and analyzing the opportunities and threats that flow from them? SWOT Analysis is a useful technique that helps you to do this.

What makes SWOT especially powerful is that, with a little thought, it can help you to uncover opportunities that you would not otherwise have spotted. And by understanding your weaknesses, you can manage and eliminate threats that might otherwise hurt your ability to move forward in your role.

If you look at yourself using the SWOT framework, you can start to separate yourself from your peers, and further develop the specialized talents and abilities that you need in order to advance your career and to help you achieve your personal goals.

SWOT Analysis is a technique that helps you identify strengths, weakness, opportunities, and threats. Understanding and managing these factors helps you to develop the abilities you need to achieve your goals and progress in your career.

Permission and Citations

If you intend to publish or circulate your document, it's important to seek permission from the copyright holder of the material that you've paraphrased or summarized. Failure to do so can leave you open to allegations of plagiarism, or even legal action.

It's good practice to cite your sources with a footnote, or with a reference in the text to a list of sources at the end of your document. There are several standard citation styles – choose one and apply it consistently, or follow your organization's house style guidelines.

As well as acknowledging the original author, citations tell you, the reader, that you're reading paraphrased or summarized material. This enables you to check the original source if you think that someone else's words may have been misused or misinterpreted.

Some writers might use others' ideas to prop up their own, but include only what suits them, for instance. Others may have misunderstood the original arguments, or "twisted" them by adding their own material.

If you're wary, or you find problems with the work, you may prefer to seek more reliable sources of information. (See our article, How to Spot Real and Fake News , for more on this.)

Paraphrasing means rephrasing text or speech in your own words, without changing its meaning. Summarizing means cutting it down to its bare essentials. You can use both techniques to clarify and simplify complex information or ideas.

To paraphrase text:

- Read and make notes.

- Find different terms.

- Put the text into your own words.

- Check your work.

You can also use paraphrasing in a meeting or conversation, by listening carefully to what's being said and repeating it back to the speaker to check that you have understood it correctly.

To summarize text or speech:

- Get a general idea of the original.

- Check your understanding.

- Make notes.

- Write your summary.

Seek permission for any copyrighted material that you use, and cite it appropriately.

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Team building exercises – strategy and planning.

Engaging Ways to Build Core Skills

Eight Steps to Effective Business Continuity Management

Eight Steps to Help Organiaztions Confront and Survive Potential Disasters

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Using Mediation To Resolve Conflict

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Resolving workplace conflict through mediation.

Managing Disputes Informally

Personal SWOT Analysis

Making the Most of Your Talents and Opportunities

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Pain points podcast - connecting to mission.

Linking Remote Teams to Organizational Purpose

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Reflecting and Paraphrasing

Part of the ‘art of listening’ is making sure that the client knows their story is being listened to.

This is achieved by the helper/counsellor repeating back to the client parts of their story. This known as paraphrasing .

Reflecting is showing the client that you have ‘heard’ not only what is being said, but also what feelings and emotions the client is experiencing when sharing their story with you .

This is sometimes known in counselling ‘speak ‘as the music behind the words .

2 FREE Downloads - Get your overview documents that describe reflection and paraphrasing and how they are used in counselling.

Free handout download.

Click here to download your Reflection in Counselling handout

Click here to download your Paraphrasing in Counselling handout

It is like holding up a mirror to the client; repeating what they have said shows the client they have your full attention. It also allows the client to make sure you fully understood them; if not, they can correct you.

Reflecting and paraphrasing should not only contain what is being said but what emotion or feeling the client is expressing.

Let’s look at an example:

Client (Mohammed): My ex-wife phoned me yesterday; she told me that our daughter Nafiza (who is only 9) is very ill after a car accident. I am feeling very scared for her. They live in France, so I am going to have to travel to see her, and now I have been made redundant, I don’t know how I can afford to go.

Counsellor: So, Mohammed, you have had some bad news about your little girl, who has been involved in an accident. You are frightened for her and also have worries over money now you have lost your job.

Client: Yes, yes ... that’s right.

Notice that the counsellor does not offer advice or start asking how long Mohammed and his wife have been separated, but reflects the emotion of what is said : ‘frightened' and 'worries'.

Reflecting and paraphrasing are the first skills we learn as helpers, and they remain the most useful.

To build a trusting relationship with a helper, the client needs not only to be ‘listened to' but also to be heard and valued as a person.

"Reflecting and paraphrasing should not only contain what is being said but what emotion or feeling the client is expressing."

Definition of Reflection in Counselling

Reflection in counselling is like holding up a mirror: repeating the client’s words back to them exactly as they said them.

You might reflect back the whole sentence, or you might select a few words – or even one single word – from what the client has brought.

I often refer to reflection as ‘the lost skill’ because when I watch counselling students doing simulated skill sessions, or listen to their recordings from placement (where clients have consented to this), I seldom see reflection being used as a skill. This is a pity, as reflection can be very powerful.

When we use the skill of reflection, we are looking to match the tone, the feeling of the words, and the client’s facial expression or body language as they spoke .

For example, they might have hunched their shoulders as they said, ‘I was so scared; I didn’t know what to do.’

We might reflect that back by hunching our own shoulders, mirroring their body language while also saying ‘I felt so scared; I didn’t know what to do.’

Using Reflection to Clarify Our Understanding

We can also use reflection to clarify our understanding, instead of using a question.

For example, suppose the client says:

‘My husband and my father are fighting. I’m really angry with him.’

For me to be in the client’s frame of reference, I need to know whether ‘him’ refers to the husband or the father. So I might reflect back the word ‘ him ’ with a quizzical look.

The client might then respond:

‘Yeah, my dad. He really gets to me when he is non-accepting.’

So you can get clarification in this way. You can adjust where you are to make sure that the empathic bond is strong and that you are truly within the client’s frame of reference.

"When we use the skill of reflection, we are looking to match the tone, the feeling of the words, and the client’s facial expression or body language as they spoke".

Definition of Paraphrasing in Counselling

Paraphrasing is repeating back your understanding of the material that has been brought by the client, using your own words.

A paraphrase reflects the essence of what has been said .

We all use paraphrasing in our everyday lives. If you look at your studies to become a counsellor or psychotherapist, you paraphrase in class.

Maybe your lecturer brings a body of work, and you listen and make notes: you’re paraphrasing as you distill this down to what you feel is important.

How Paraphrasing Builds Empathy

How does paraphrasing affect the client-counsellor relationship?

First of all, it helps the client to feel both heard and understood. The client brings their material, daring to share that with you.

And you show that you’re listening by giving them a little portion of that back – the part that feels the most important. You paraphrase it down.

And if you do that accurately and correctly, and it matches where the client is, the client is going to recognise that and to feel heard: ‘ Finally, somebody is there really listening, really understanding what it is that I am bringing.’

This keys right into empathy, because it’s about building that empathic relationship with the client. And empathy is not a one-way transaction .

..."Empathy [is] the ability to ‘perceive the internal frame of reference of another with accuracy and with the emotional components and meanings which pertain thereto as if one were the person, but without ever losing the 'as if' conditions." Carl Rogers (1959, pp. 210–211)

In other words, we walk in somebody’s shoes as if their reality is our reality – but of course it’s not our reality, and that’s where the ‘as if’ comes in.

I’ve heard this rather aptly described as ‘walking in the client’s shoes, but keeping our socks on’!

Empathy is a two-way transaction – that is, it’s not enough for us to be 100% in the client’s frame of reference , understanding their true feelings; the client must also perceive that we understand .

When the client feels at some level that they have been understood, then the empathy circle is complete.

Spotted out-of-date info or broken links? Kindly let us know the page where you found them. Email: [email protected]

1 thought on “Reflecting and Paraphrasing”

Pingback: Paraphrasing In Counseling [Updated]

Comments are closed.

- Join Mind Tools

Paraphrasing and Summarizing

Summing up key ideas in your own words.

© GettyImages Foxys_forest_manufacture

Make complex information easier to digest!

Imagine you're preparing a presentation for your CEO. You asked everyone in your team to contribute, and they all had plenty to say!

But now you have a dozen reports, all in different styles, and your CEO says that she can spare only 10 minutes to read the final version. What do you do?

The solution is to paraphrase and summarize the reports, so your boss gets only the key information that she needs, in a form that she can process quickly.

In this article, we explain how to paraphrase and how to summarize, and how to apply these techniques to text and the spoken word. We also explore the differences between the two skills, and point out the pitfalls to avoid.

What Is Paraphrasing?

When you paraphrase, you use your own words to express something that was written or said by another person.

Putting it into your own words can clarify the message, make it more relevant to your audience , or give it greater impact.

You might use paraphrased material to support your own argument or viewpoint. Or, if you're putting together a report , presentation or speech , you can use paraphrasing to maintain a consistent style, and to avoid lengthy quotations from the original text or conversation.

Paraphrased material should keep its original meaning and (approximate) length, but you can use it to pick out a single point from a longer discussion.

What Is Summarizing?

In contrast, a summary is a brief overview of an entire discussion or argument. You might summarize a whole research paper or conversation in a single paragraph, for example, or with a series of bullet points, using your own words and style.

People often summarize when the original material is long, or to emphasize key facts or points. Summaries leave out detail or examples that may distract the reader from the most important information, and they simplify complex arguments, grammar and vocabulary.

Used correctly, summarizing and paraphrasing can save time, increase understanding, and give authority and credibility to your work. Both tools are useful when the precise wording of the original communication is less important than its overall meaning.

How to Paraphrase Text

To paraphrase text, follow these four steps:

1. Read and Make Notes

Carefully read the text that you want to paraphrase. Highlight, underline or note down important terms and phrases that you need to remember.

2. Find Different Terms

Find equivalent words or phrases (synonyms) to use in place of the ones that you've picked out. A dictionary, thesaurus or online search can be useful here, but take care to preserve the meaning of the original text, particularly if you're dealing with technical or scientific terms.

3. Put the Text into Your Own Words

Rewrite the original text, line by line. Simplify the grammar and vocabulary, adjust the order of the words and sentences, and replace "passive" expressions with "active" ones (for example, you could change "The new supplier was contacted by Nusrat" to "Nusrat contacted the new supplier").

Remove complex clauses, and break longer sentences into shorter ones. All of this will make your new version easier to understand .

4. Check Your Work

Check your work by comparing it to the original. Your paraphrase should be clear and simple, and written in your own words. It may be shorter, but it should include all of the necessary detail.

Paraphrasing: an Example

Despite the undoubted fact that everyone's vision of what constitutes success is different, one should spend one's time establishing and finalizing one's personal vision of it. Otherwise, how can you possibly understand what your final destination might be, or whether or not your decisions are assisting you in moving in the direction of the goals which you've set yourself?

The two kinds of statement – mission and vision – can be invaluable to your approach, aiding you, as they do, in focusing on your primary goal, and quickly identifying possibilities that you might wish to exploit and explore.

We all have different ideas about success. What's important is that you spend time defining your version of success. That way, you'll understand what you should be working toward. You'll also know if your decisions are helping you to move toward your goals.

Used as part of your personal approach to goal-setting, mission and vision statements are useful for bringing sharp focus to your most important goal, and for helping you to quickly identify which opportunities you should pursue.

How to Paraphrase Speech

In a conversation – a meeting or coaching session, for example – paraphrasing is a good way to make sure that you have correctly understood what the other person has said.

This requires two additional skills: active listening and asking the right questions .

Useful questions include:

- If I hear you correctly, you're saying that…?

- So you mean that…? Is that right?

- Did I understand you when you said that…?

You can use questions like these to repeat the speaker's words back to them. For instance, if the person says, "We just don't have the funds available for these projects," you could reply: "If I understand you correctly, you're saying that our organization can't afford to pay for my team's projects?"

This may seem repetitive, but it gives the speaker the opportunity to highlight any misunderstandings, or to clarify their position.

When you're paraphrasing conversations in this way, take care not to introduce new ideas or information, and not to make judgements on what the other person has said, or to "spin" their words toward what you want to hear. Instead, simply restate their position as you understand it.

Sometimes, you may need to paraphrase a speech or a presentation. Perhaps you want to report back to your team, or write about it in a company blog, for example.

In these cases it's a good idea to make summary notes as you listen, and to work them up into a paraphrase later. (See How to Summarize Text or Speech, below.)

How to Summarize Text or Speech

Follow steps 1-5 below to summarize text. To summarize spoken material – a speech, a meeting, or a presentation, for example – start at step 3.

Finding This Article Useful?

You can learn another 151 communication skills, like this, by joining the Mind Tools Club.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Receive new career skills every week, plus get our latest offers and a free downloadable Personal Development Plan workbook.

1. Get a General Idea of the Original

First, speed read the text that you're summarizing to get a general impression of its content. Pay particular attention to the title, introduction, conclusion, and the headings and subheadings.

2. Check Your Understanding

Build your comprehension of the text by reading it again more carefully. Check that your initial interpretation of the content was correct.

3. Make Notes

Take notes on what you're reading or listening to. Use bullet points, and introduce each bullet with a key word or idea. Write down only one point or idea for each bullet.

If you're summarizing spoken material, you may not have much time on each point before the speaker moves on. If you can, obtain a meeting agenda, a copy of the presentation, or a transcript of the speech in advance, so you know what's coming.

Make sure your notes are concise, well-ordered, and include only the points that really matter.

The Cornell Note-Taking System is an effective way to organize your notes as you write them, so that you can easily identify key points and actions later. Our article, Writing Meeting Notes , also contains plenty of useful advice.

4. Write Your Summary

Bullet points or numbered lists are often an acceptable format for summaries – for example, on presentation slides, in the minutes of a meeting, or in Key Points sections like the one at the end of this article.

However, don't just use the bulleted notes that you took in step 3. They'll likely need editing or "polishing" if you want other people to understand them.

Some summaries, such as research paper abstracts, press releases, and marketing copy, require continuous prose. If this is the case, write your summary as a paragraph, turning each bullet point into a full sentence.

Aim to use only your own notes, and refer to original documents or recordings only if you really need to. This helps to ensure that you use your own words.

If you're summarizing speech, do so as soon as possible after the event, while it's still fresh in your mind.

5. Check Your Work

Your summary should be a brief but informative outline of the original. Check that you've expressed all of the most important points in your own words, and that you've left out any unnecessary detail.

Summarizing: an Example

So how do you go about identifying your strengths and weaknesses, and analyzing the opportunities and threats that flow from them? SWOT Analysis is a useful technique that helps you to do this.

What makes SWOT especially powerful is that, with a little thought, it can help you to uncover opportunities that you would not otherwise have spotted. And by understanding your weaknesses, you can manage and eliminate threats that might otherwise hurt your ability to move forward in your role.

If you look at yourself using the SWOT framework, you can start to separate yourself from your peers, and further develop the specialized talents and abilities that you need in order to advance your career and to help you achieve your personal goals.

SWOT Analysis is a technique that helps you identify strengths, weakness, opportunities, and threats. Understanding and managing these factors helps you to develop the abilities you need to achieve your goals and progress in your career.

Permission and Citations

If you intend to publish or circulate your document, it's important to seek permission from the copyright holder of the material that you've paraphrased or summarized. Failure to do so can leave you open to allegations of plagiarism, or even legal action.