- UWF Libraries

Literature Review: Conducting & Writing

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Chicago: Notes Bibliography This link opens in a new window

- MLA Style This link opens in a new window

Sample Lit Reviews from Communication Arts

Have an exemplary literature review.

- Literature Review Sample 1

- Literature Review Sample 2

- Literature Review Sample 3

Have you written a stellar literature review you care to share for teaching purposes?

Are you an instructor who has received an exemplary literature review and have permission from the student to post?

Please contact Britt McGowan at [email protected] for inclusion in this guide. All disciplines welcome and encouraged.

- << Previous: MLA Style

- Next: Get Help! >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 9:37 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/litreview

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

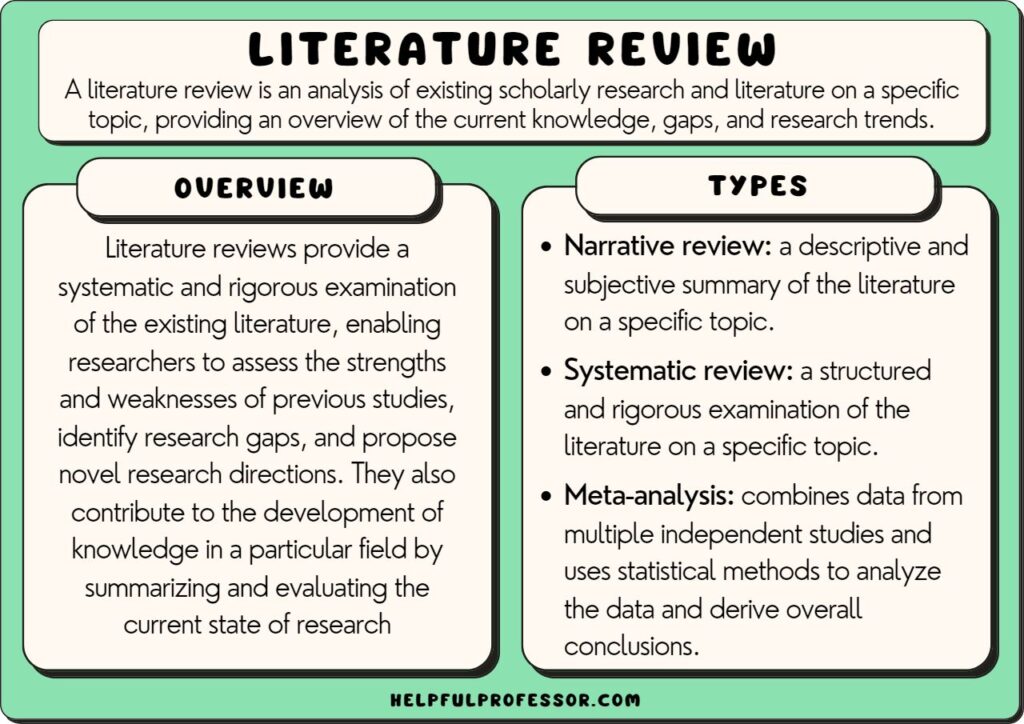

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

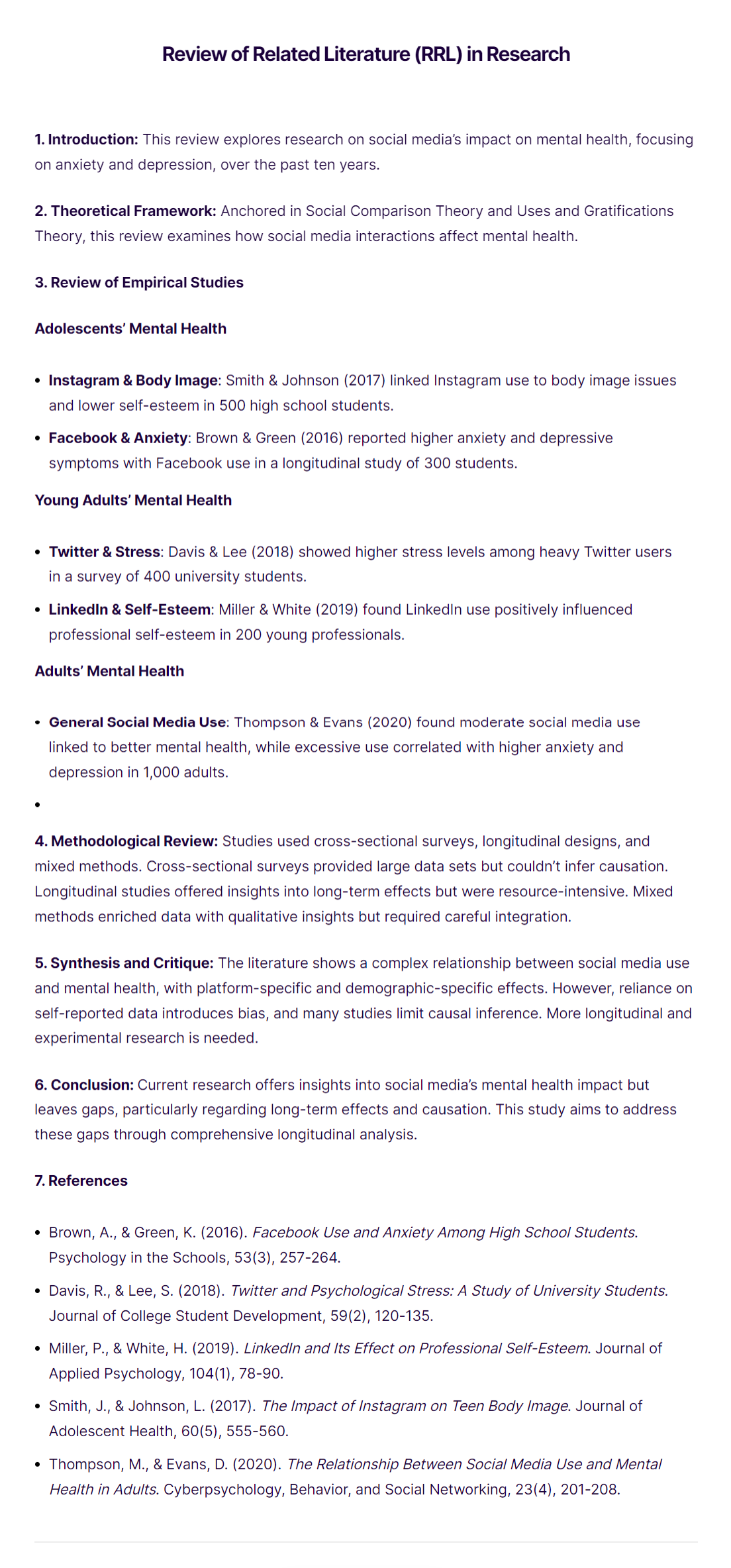

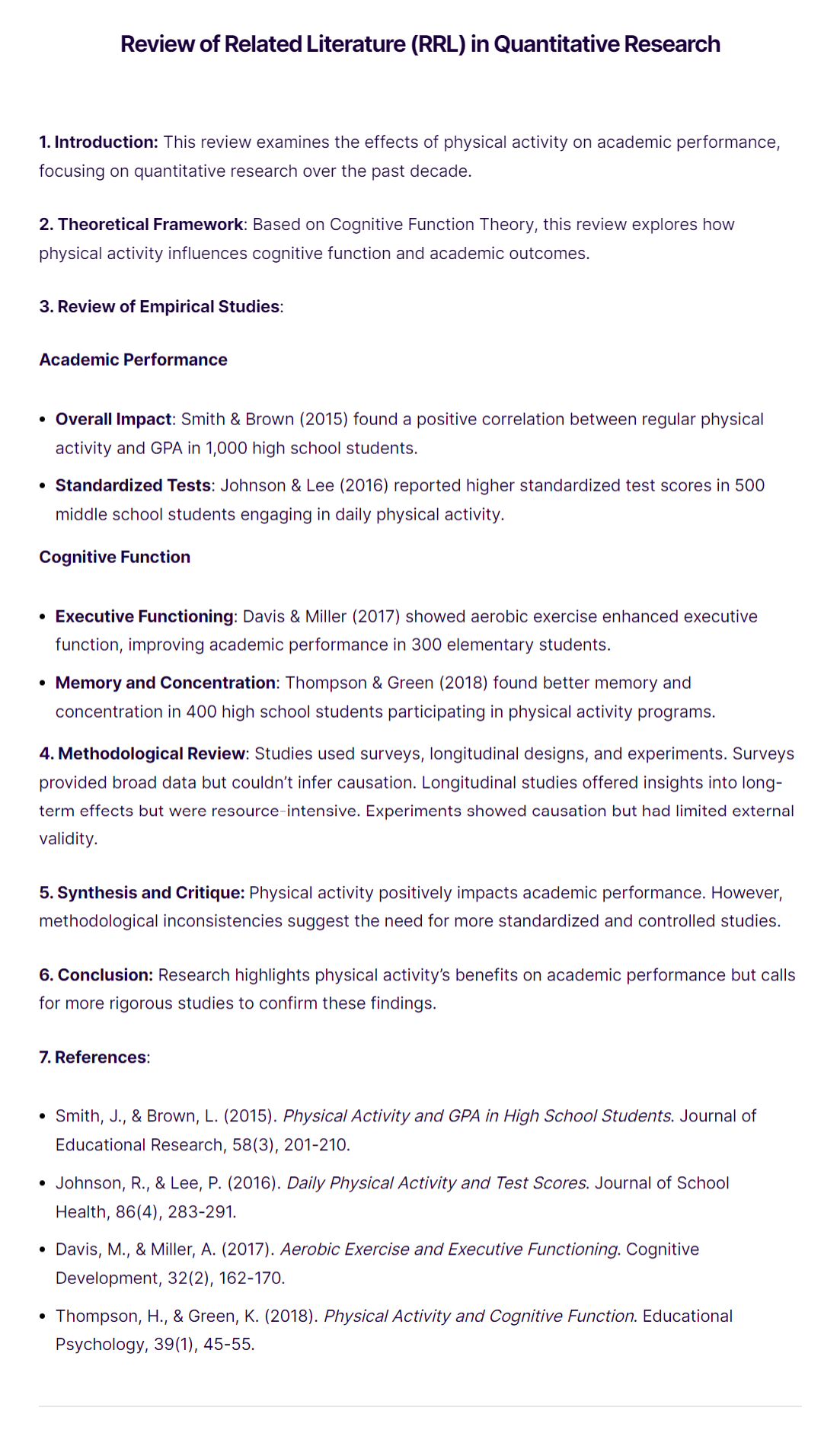

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, mla works cited page: format, template & examples, how to ace grant writing for research funding..., powerful academic phrases to improve your essay writing , how to write a high-quality conference paper, how paperpal’s research feature helps you develop and..., how paperpal is enhancing academic productivity and accelerating..., how to write a successful book chapter for..., academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., 4 ways paperpal encourages responsible writing with ai, what are scholarly sources and where can you....

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 31 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Literature Review Guide: Examples of Literature Reviews

- What is a Literature Review?

- How to start?

- Search strategies and Databases

- Examples of Literature Reviews

- How to organise the review

- Library summary

- Emerald Infographic

All good quality journal articles will include a small Literature Review after the Introduction paragraph. It may not be called a Literature Review but gives you an idea of how one is created in miniature.

Sample Literature Reviews as part of a articles or Theses

- Sample Literature Review on Critical Thinking (Gwendolyn Reece, American University Library)

- Hackett, G and Melia, D . The hotel as the holiday/stay destination:trends and innovations. Presented at TRIC Conference, Belfast, Ireland- June 2012 and EuroCHRIE Conference

Links to sample Literature Reviews from other libraries

- Sample literature reviews from University of West Florida

Standalone Literature Reviews

- Attitudes towards the Disability in Ireland

- Martin, A., O'Connor-Fenelon, M. and Lyons, R. (2010). Non-verbal communication between nurses and people with an intellectual disability: A review of the literature. Journal of Intellectual Diabilities, 14(4), 303-314.

Irish Theses

- Phillips, Martin (2015) European airline performance: a data envelopment analysis with extrapolations based on model outputs. Master of Business Studies thesis, Dublin City University.

- The customers’ perception of servicescape’s influence on their behaviours, in the food retail industry : Dublin Business School 2015

- Coughlan, Ray (2015) What was the role of leadership in the transformation of a failing Irish Insurance business. Masters thesis, Dublin, National College of Ireland.

- << Previous: Search strategies and Databases

- Next: Tutorials >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://ait.libguides.com/literaturereview

Literature Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Introduction

OK. You’ve got to write a literature review. You dust off a novel and a book of poetry, settle down in your chair, and get ready to issue a “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” as you leaf through the pages. “Literature review” done. Right?

Wrong! The “literature” of a literature review refers to any collection of materials on a topic, not necessarily the great literary texts of the world. “Literature” could be anything from a set of government pamphlets on British colonial methods in Africa to scholarly articles on the treatment of a torn ACL. And a review does not necessarily mean that your reader wants you to give your personal opinion on whether or not you liked these sources.

What is a literature review, then?

A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period.

A literature review can be just a simple summary of the sources, but it usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis. A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. And depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant.

But how is a literature review different from an academic research paper?

The main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper is likely to contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

Why do we write literature reviews?

Literature reviews provide you with a handy guide to a particular topic. If you have limited time to conduct research, literature reviews can give you an overview or act as a stepping stone. For professionals, they are useful reports that keep them up to date with what is current in the field. For scholars, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the writer in his or her field. Literature reviews also provide a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. Comprehensive knowledge of the literature of the field is essential to most research papers.

Who writes these things, anyway?

Literature reviews are written occasionally in the humanities, but mostly in the sciences and social sciences; in experiment and lab reports, they constitute a section of the paper. Sometimes a literature review is written as a paper in itself.

Let’s get to it! What should I do before writing the literature review?

If your assignment is not very specific, seek clarification from your instructor:

- Roughly how many sources should you include?

- What types of sources (books, journal articles, websites)?

- Should you summarize, synthesize, or critique your sources by discussing a common theme or issue?

- Should you evaluate your sources?

- Should you provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history?

Find models

Look for other literature reviews in your area of interest or in the discipline and read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or ways to organize your final review. You can simply put the word “review” in your search engine along with your other topic terms to find articles of this type on the Internet or in an electronic database. The bibliography or reference section of sources you’ve already read are also excellent entry points into your own research.

Narrow your topic

There are hundreds or even thousands of articles and books on most areas of study. The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good survey of the material. Your instructor will probably not expect you to read everything that’s out there on the topic, but you’ll make your job easier if you first limit your scope.

Keep in mind that UNC Libraries have research guides and to databases relevant to many fields of study. You can reach out to the subject librarian for a consultation: https://library.unc.edu/support/consultations/ .

And don’t forget to tap into your professor’s (or other professors’) knowledge in the field. Ask your professor questions such as: “If you had to read only one book from the 90’s on topic X, what would it be?” Questions such as this help you to find and determine quickly the most seminal pieces in the field.

Consider whether your sources are current

Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. In the sciences, for instance, treatments for medical problems are constantly changing according to the latest studies. Information even two years old could be obsolete. However, if you are writing a review in the humanities, history, or social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be what is needed, because what is important is how perspectives have changed through the years or within a certain time period. Try sorting through some other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to consider what is currently of interest to scholars in this field and what is not.

Strategies for writing the literature review

Find a focus.

A literature review, like a term paper, is usually organized around ideas, not the sources themselves as an annotated bibliography would be organized. This means that you will not just simply list your sources and go into detail about each one of them, one at a time. No. As you read widely but selectively in your topic area, consider instead what themes or issues connect your sources together. Do they present one or different solutions? Is there an aspect of the field that is missing? How well do they present the material and do they portray it according to an appropriate theory? Do they reveal a trend in the field? A raging debate? Pick one of these themes to focus the organization of your review.

Convey it to your reader

A literature review may not have a traditional thesis statement (one that makes an argument), but you do need to tell readers what to expect. Try writing a simple statement that lets the reader know what is your main organizing principle. Here are a couple of examples:

The current trend in treatment for congestive heart failure combines surgery and medicine. More and more cultural studies scholars are accepting popular media as a subject worthy of academic consideration.

Consider organization

You’ve got a focus, and you’ve stated it clearly and directly. Now what is the most effective way of presenting the information? What are the most important topics, subtopics, etc., that your review needs to include? And in what order should you present them? Develop an organization for your review at both a global and local level:

First, cover the basic categories

Just like most academic papers, literature reviews also must contain at least three basic elements: an introduction or background information section; the body of the review containing the discussion of sources; and, finally, a conclusion and/or recommendations section to end the paper. The following provides a brief description of the content of each:

- Introduction: Gives a quick idea of the topic of the literature review, such as the central theme or organizational pattern.

- Body: Contains your discussion of sources and is organized either chronologically, thematically, or methodologically (see below for more information on each).

- Conclusions/Recommendations: Discuss what you have drawn from reviewing literature so far. Where might the discussion proceed?

Organizing the body

Once you have the basic categories in place, then you must consider how you will present the sources themselves within the body of your paper. Create an organizational method to focus this section even further.

To help you come up with an overall organizational framework for your review, consider the following scenario:

You’ve decided to focus your literature review on materials dealing with sperm whales. This is because you’ve just finished reading Moby Dick, and you wonder if that whale’s portrayal is really real. You start with some articles about the physiology of sperm whales in biology journals written in the 1980’s. But these articles refer to some British biological studies performed on whales in the early 18th century. So you check those out. Then you look up a book written in 1968 with information on how sperm whales have been portrayed in other forms of art, such as in Alaskan poetry, in French painting, or on whale bone, as the whale hunters in the late 19th century used to do. This makes you wonder about American whaling methods during the time portrayed in Moby Dick, so you find some academic articles published in the last five years on how accurately Herman Melville portrayed the whaling scene in his novel.

Now consider some typical ways of organizing the sources into a review:

- Chronological: If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials above according to when they were published. For instance, first you would talk about the British biological studies of the 18th century, then about Moby Dick, published in 1851, then the book on sperm whales in other art (1968), and finally the biology articles (1980s) and the recent articles on American whaling of the 19th century. But there is relatively no continuity among subjects here. And notice that even though the sources on sperm whales in other art and on American whaling are written recently, they are about other subjects/objects that were created much earlier. Thus, the review loses its chronological focus.

- By publication: Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on biological studies of sperm whales if the progression revealed a change in dissection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies.

- By trend: A better way to organize the above sources chronologically is to examine the sources under another trend, such as the history of whaling. Then your review would have subsections according to eras within this period. For instance, the review might examine whaling from pre-1600-1699, 1700-1799, and 1800-1899. Under this method, you would combine the recent studies on American whaling in the 19th century with Moby Dick itself in the 1800-1899 category, even though the authors wrote a century apart.

- Thematic: Thematic reviews of literature are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time. However, progression of time may still be an important factor in a thematic review. For instance, the sperm whale review could focus on the development of the harpoon for whale hunting. While the study focuses on one topic, harpoon technology, it will still be organized chronologically. The only difference here between a “chronological” and a “thematic” approach is what is emphasized the most: the development of the harpoon or the harpoon technology.But more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. For instance, a thematic review of material on sperm whales might examine how they are portrayed as “evil” in cultural documents. The subsections might include how they are personified, how their proportions are exaggerated, and their behaviors misunderstood. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point made.

- Methodological: A methodological approach differs from the two above in that the focusing factor usually does not have to do with the content of the material. Instead, it focuses on the “methods” of the researcher or writer. For the sperm whale project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of whales in American, British, and French art work. Or the review might focus on the economic impact of whaling on a community. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed. Once you’ve decided on the organizational method for the body of the review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out. They should arise out of your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period. A thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue.

Sometimes, though, you might need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. Put in only what is necessary. Here are a few other sections you might want to consider:

- Current Situation: Information necessary to understand the topic or focus of the literature review.

- History: The chronological progression of the field, the literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Methods and/or Standards: The criteria you used to select the sources in your literature review or the way in which you present your information. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed articles and journals.

Questions for Further Research: What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

Begin composing

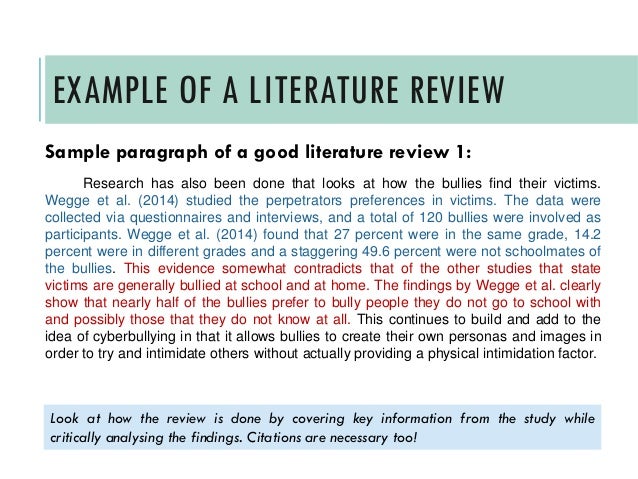

Once you’ve settled on a general pattern of organization, you’re ready to write each section. There are a few guidelines you should follow during the writing stage as well. Here is a sample paragraph from a literature review about sexism and language to illuminate the following discussion:

However, other studies have shown that even gender-neutral antecedents are more likely to produce masculine images than feminine ones (Gastil, 1990). Hamilton (1988) asked students to complete sentences that required them to fill in pronouns that agreed with gender-neutral antecedents such as “writer,” “pedestrian,” and “persons.” The students were asked to describe any image they had when writing the sentence. Hamilton found that people imagined 3.3 men to each woman in the masculine “generic” condition and 1.5 men per woman in the unbiased condition. Thus, while ambient sexism accounted for some of the masculine bias, sexist language amplified the effect. (Source: Erika Falk and Jordan Mills, “Why Sexist Language Affects Persuasion: The Role of Homophily, Intended Audience, and Offense,” Women and Language19:2).

Use evidence

In the example above, the writers refer to several other sources when making their point. A literature review in this sense is just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence to show that what you are saying is valid.

Be selective

Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the review’s focus, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological.

Use quotes sparingly

Falk and Mills do not use any direct quotes. That is because the survey nature of the literature review does not allow for in-depth discussion or detailed quotes from the text. Some short quotes here and there are okay, though, if you want to emphasize a point, or if what the author said just cannot be rewritten in your own words. Notice that Falk and Mills do quote certain terms that were coined by the author, not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. But if you find yourself wanting to put in more quotes, check with your instructor.

Summarize and synthesize

Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each paragraph as well as throughout the review. The authors here recapitulate important features of Hamilton’s study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study’s significance and relating it to their own work.

Keep your own voice

While the literature review presents others’ ideas, your voice (the writer’s) should remain front and center. Notice that Falk and Mills weave references to other sources into their own text, but they still maintain their own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with their own ideas and their own words. The sources support what Falk and Mills are saying.

Use caution when paraphrasing

When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author’s information or opinions accurately and in your own words. In the preceding example, Falk and Mills either directly refer in the text to the author of their source, such as Hamilton, or they provide ample notation in the text when the ideas they are mentioning are not their own, for example, Gastil’s. For more information, please see our handout on plagiarism .

Revise, revise, revise

Draft in hand? Now you’re ready to revise. Spending a lot of time revising is a wise idea, because your main objective is to present the material, not the argument. So check over your review again to make sure it follows the assignment and/or your outline. Then, just as you would for most other academic forms of writing, rewrite or rework the language of your review so that you’ve presented your information in the most concise manner possible. Be sure to use terminology familiar to your audience; get rid of unnecessary jargon or slang. Finally, double check that you’ve documented your sources and formatted the review appropriately for your discipline. For tips on the revising and editing process, see our handout on revising drafts .

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Jones, Robert, Patrick Bizzaro, and Cynthia Selfe. 1997. The Harcourt Brace Guide to Writing in the Disciplines . New York: Harcourt Brace.

Lamb, Sandra E. 1998. How to Write It: A Complete Guide to Everything You’ll Ever Write . Berkeley: Ten Speed Press.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

Troyka, Lynn Quittman, and Doug Hesse. 2016. Simon and Schuster Handbook for Writers , 11th ed. London: Pearson.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is a literature review? [with examples]

What is a literature review?

The purpose of a literature review, how to write a literature review, the format of a literature review, general formatting rules, the length of a literature review, literature review examples, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

In a literature review, you’re expected to report on the existing scholarly conversation, without adding new contributions.

If you are currently writing one, you've come to the right place. In the following paragraphs, we will explain:

- the objective of a literature review

- how to write a literature review

- the basic format of a literature review

Tip: It’s not always mandatory to add a literature review in a paper. Theses and dissertations often include them, whereas research papers may not. Make sure to consult with your instructor for exact requirements.

The four main objectives of a literature review are:

- Studying the references of your research area

- Summarizing the main arguments

- Identifying current gaps, stances, and issues

- Presenting all of the above in a text

Ultimately, the main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

The format of a literature review is fairly standard. It includes an:

- introduction that briefly introduces the main topic

- body that includes the main discussion of the key arguments

- conclusion that highlights the gaps and issues of the literature

➡️ Take a look at our guide on how to write a literature review to learn more about how to structure a literature review.

First of all, a literature review should have its own labeled section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature can be found, and you should label this section as “Literature Review.”

➡️ For more information on writing a thesis, visit our guide on how to structure a thesis .

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, it will be short.

Take a look at these three theses featuring great literature reviews:

- School-Based Speech-Language Pathologist's Perceptions of Sensory Food Aversions in Children [ PDF , see page 20]

- Who's Writing What We Read: Authorship in Criminological Research [ PDF , see page 4]

- A Phenomenological Study of the Lived Experience of Online Instructors of Theological Reflection at Christian Institutions Accredited by the Association of Theological Schools [ PDF , see page 56]

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

No. A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature review can be found, and label this section as “Literature Review.”

The main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

15 Literature Review Examples

Literature reviews are a necessary step in a research process and often required when writing your research proposal . They involve gathering, analyzing, and evaluating existing knowledge about a topic in order to find gaps in the literature where future studies will be needed.

Ideally, once you have completed your literature review, you will be able to identify how your research project can build upon and extend existing knowledge in your area of study.

Generally, for my undergraduate research students, I recommend a narrative review, where themes can be generated in order for the students to develop sufficient understanding of the topic so they can build upon the themes using unique methods or novel research questions.

If you’re in the process of writing a literature review, I have developed a literature review template for you to use – it’s a huge time-saver and walks you through how to write a literature review step-by-step:

Get your time-saving templates here to write your own literature review.

Literature Review Examples

For the following types of literature review, I present an explanation and overview of the type, followed by links to some real-life literature reviews on the topics.

1. Narrative Review Examples

Also known as a traditional literature review, the narrative review provides a broad overview of the studies done on a particular topic.

It often includes both qualitative and quantitative studies and may cover a wide range of years.

The narrative review’s purpose is to identify commonalities, gaps, and contradictions in the literature .

I recommend to my students that they should gather their studies together, take notes on each study, then try to group them by themes that form the basis for the review (see my step-by-step instructions at the end of the article).

Example Study

Title: Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations

Citation: Vermeir, P., Vandijck, D., Degroote, S., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Mortier, E., … & Vogelaers, D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International journal of clinical practice , 69 (11), 1257-1267.

Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ijcp.12686

Overview: This narrative review analyzed themes emerging from 69 articles about communication in healthcare contexts. Five key themes were found in the literature: poor communication can lead to various negative outcomes, discontinuity of care, compromise of patient safety, patient dissatisfaction, and inefficient use of resources. After presenting the key themes, the authors recommend that practitioners need to approach healthcare communication in a more structured way, such as by ensuring there is a clear understanding of who is in charge of ensuring effective communication in clinical settings.

Other Examples

- Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review (Reith, 2018) – read here

- Examining the Presence, Consequences, and Reduction of Implicit Bias in Health Care: A Narrative Review (Zestcott, Blair & Stone, 2016) – read here

- A Narrative Review of School-Based Physical Activity for Enhancing Cognition and Learning (Mavilidi et al., 2018) – read here

- A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents (Dyrbye & Shanafelt, 2015) – read here

2. Systematic Review Examples

This type of literature review is more structured and rigorous than a narrative review. It involves a detailed and comprehensive plan and search strategy derived from a set of specified research questions.

The key way you’d know a systematic review compared to a narrative review is in the methodology: the systematic review will likely have a very clear criteria for how the studies were collected, and clear explanations of exclusion/inclusion criteria.

The goal is to gather the maximum amount of valid literature on the topic, filter out invalid or low-quality reviews, and minimize bias. Ideally, this will provide more reliable findings, leading to higher-quality conclusions and recommendations for further research.

You may note from the examples below that the ‘method’ sections in systematic reviews tend to be much more explicit, often noting rigid inclusion/exclusion criteria and exact keywords used in searches.

Title: The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review

Citation: Roman, S., Sánchez-Siles, L. M., & Siegrist, M. (2017). The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends in food science & technology , 67 , 44-57.

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S092422441730122X

Overview: This systematic review included 72 studies of food naturalness to explore trends in the literature about its importance for consumers. Keywords used in the data search included: food, naturalness, natural content, and natural ingredients. Studies were included if they examined consumers’ preference for food naturalness and contained empirical data. The authors found that the literature lacks clarity about how naturalness is defined and measured, but also found that food consumption is significantly influenced by perceived naturalness of goods.

- A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018 (Martin, Sun & Westine, 2020) – read here

- Where Is Current Research on Blockchain Technology? (Yli-Huumo et al., 2016) – read here

- Universities—industry collaboration: A systematic review (Ankrah & Al-Tabbaa, 2015) – read here

- Internet of Things Applications: A Systematic Review (Asghari, Rahmani & Javadi, 2019) – read here

3. Meta-analysis

This is a type of systematic review that uses statistical methods to combine and summarize the results of several studies.

Due to its robust methodology, a meta-analysis is often considered the ‘gold standard’ of secondary research , as it provides a more precise estimate of a treatment effect than any individual study contributing to the pooled analysis.

Furthermore, by aggregating data from a range of studies, a meta-analysis can identify patterns, disagreements, or other interesting relationships that may have been hidden in individual studies.

This helps to enhance the generalizability of findings, making the conclusions drawn from a meta-analysis particularly powerful and informative for policy and practice.

Title: Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s Disease Risk: A Meta-Meta-Analysis

Citation: Sáiz-Vazquez, O., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubillos-Landa, S., Pacheco-Bonrostro, J., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease risk: a meta-meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 10(6), 386.

Source: https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10060386

O verview: This study examines the relationship between cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Researchers conducted a systematic search of meta-analyses and reviewed several databases, collecting 100 primary studies and five meta-analyses to analyze the connection between cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease. They find that the literature compellingly demonstrates that low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels significantly influence the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

- The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research (Wisniewski, Zierer & Hattie, 2020) – read here

- How Much Does Education Improve Intelligence? A Meta-Analysis (Ritchie & Tucker-Drob, 2018) – read here

- A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling (Geiger et al., 2019) – read here

- Stress management interventions for police officers and recruits (Patterson, Chung & Swan, 2014) – read here

Other Types of Reviews

- Scoping Review: This type of review is used to map the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available. It can be undertaken as stand-alone projects in their own right, or as a precursor to a systematic review.

- Rapid Review: This type of review accelerates the systematic review process in order to produce information in a timely manner. This is achieved by simplifying or omitting stages of the systematic review process.

- Integrative Review: This review method is more inclusive than others, allowing for the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research. The goal is to more comprehensively understand a particular phenomenon.

- Critical Review: This is similar to a narrative review but requires a robust understanding of both the subject and the existing literature. In a critical review, the reviewer not only summarizes the existing literature, but also evaluates its strengths and weaknesses. This is common in the social sciences and humanities .

- State-of-the-Art Review: This considers the current level of advancement in a field or topic and makes recommendations for future research directions. This type of review is common in technological and scientific fields but can be applied to any discipline.

How to Write a Narrative Review (Tips for Undergrad Students)

Most undergraduate students conducting a capstone research project will be writing narrative reviews. Below is a five-step process for conducting a simple review of the literature for your project.

- Search for Relevant Literature: Use scholarly databases related to your field of study, provided by your university library, along with appropriate search terms to identify key scholarly articles that have been published on your topic.

- Evaluate and Select Sources: Filter the source list by selecting studies that are directly relevant and of sufficient quality, considering factors like credibility , objectivity, accuracy, and validity.

- Analyze and Synthesize: Review each source and summarize the main arguments in one paragraph (or more, for postgrad). Keep these summaries in a table.

- Identify Themes: With all studies summarized, group studies that share common themes, such as studies that have similar findings or methodologies.

- Write the Review: Write your review based upon the themes or subtopics you have identified. Give a thorough overview of each theme, integrating source data, and conclude with a summary of the current state of knowledge then suggestions for future research based upon your evaluation of what is lacking in the literature.

Literature reviews don’t have to be as scary as they seem. Yes, they are difficult and require a strong degree of comprehension of academic studies. But it can be feasibly done through following a structured approach to data collection and analysis. With my undergraduate research students (who tend to conduct small-scale qualitative studies ), I encourage them to conduct a narrative literature review whereby they can identify key themes in the literature. Within each theme, students can critique key studies and their strengths and limitations , in order to get a lay of the land and come to a point where they can identify ways to contribute new insights to the existing academic conversation on their topic.

Ankrah, S., & Omar, A. T. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), 387-408.

Asghari, P., Rahmani, A. M., & Javadi, H. H. S. (2019). Internet of Things applications: A systematic review. Computer Networks , 148 , 241-261.

Dyrbye, L., & Shanafelt, T. (2016). A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Medical education , 50 (1), 132-149.

Geiger, J. L., Steg, L., Van Der Werff, E., & Ünal, A. B. (2019). A meta-analysis of factors related to recycling. Journal of environmental psychology , 64 , 78-97.

Martin, F., Sun, T., & Westine, C. D. (2020). A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018. Computers & education , 159 , 104009.

Mavilidi, M. F., Ruiter, M., Schmidt, M., Okely, A. D., Loyens, S., Chandler, P., & Paas, F. (2018). A narrative review of school-based physical activity for enhancing cognition and learning: The importance of relevancy and integration. Frontiers in psychology , 2079.

Patterson, G. T., Chung, I. W., & Swan, P. W. (2014). Stress management interventions for police officers and recruits: A meta-analysis. Journal of experimental criminology , 10 , 487-513.

Reith, T. P. (2018). Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: a narrative review. Cureus , 10 (12).

Ritchie, S. J., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2018). How much does education improve intelligence? A meta-analysis. Psychological science , 29 (8), 1358-1369.

Roman, S., Sánchez-Siles, L. M., & Siegrist, M. (2017). The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends in food science & technology , 67 , 44-57.

Sáiz-Vazquez, O., Puente-Martínez, A., Ubillos-Landa, S., Pacheco-Bonrostro, J., & Santabárbara, J. (2020). Cholesterol and Alzheimer’s disease risk: a meta-meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 10(6), 386.

Vermeir, P., Vandijck, D., Degroote, S., Peleman, R., Verhaeghe, R., Mortier, E., … & Vogelaers, D. (2015). Communication in healthcare: a narrative review of the literature and practical recommendations. International journal of clinical practice , 69 (11), 1257-1267.

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta-analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology , 10 , 3087.

Yli-Huumo, J., Ko, D., Choi, S., Park, S., & Smolander, K. (2016). Where is current research on blockchain technology?—a systematic review. PloS one , 11 (10), e0163477.

Zestcott, C. A., Blair, I. V., & Stone, J. (2016). Examining the presence, consequences, and reduction of implicit bias in health care: a narrative review. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations , 19 (4), 528-542

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Forest Schools Philosophy & Curriculum, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori's 4 Planes of Development, Explained!

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Montessori vs Reggio Emilia vs Steiner-Waldorf vs Froebel

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Parten’s 6 Stages of Play in Childhood, Explained!

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.