a large database of idioms

Understanding the Idiom: "make history" - Meaning, Origins, and Usage

The phrase “make history” is a common idiom used in everyday language. It refers to an event or action that has significant impact and will be remembered for years to come. This idiom is often used in contexts where something remarkable or groundbreaking has occurred, such as in politics, sports, or entertainment.

When someone makes history, they are creating a moment that will be talked about for generations. This can include achieving a major accomplishment, breaking a record, or making a significant contribution to society. The phrase can also refer to events that have negative consequences and leave lasting impacts on the world.

- Examples of positive moments where someone made history:

- Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon

- Nelson Mandela becoming South Africa’s first black president

- Serena Williams winning her 23rd Grand Slam title

- Examples of negative moments where someone made history:

- The bombing of Hiroshima during World War II

- The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

- The Chernobyl disaster

Origins and Historical Context of the Idiom “make history”

The idiom “make history” is a commonly used phrase in the English language that refers to someone or something that has had a significant impact on society, culture, or politics. It is often used to describe individuals who have achieved great things or events that have changed the course of history.

The Origin of the Phrase

The origin of this idiom can be traced back to ancient Greece where historians would record important events and people for future generations. The idea behind making history was to leave a lasting legacy and ensure that one’s accomplishments were remembered long after they were gone.

Historical Context

The concept of making history has been present throughout human civilization, from ancient times to modern-day. Throughout history, there have been countless individuals who have made significant contributions to society and left their mark on the world. From political leaders like Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill to cultural icons like Shakespeare and Picasso, these individuals are remembered for their achievements and continue to inspire others today.

Usage and Variations of the Idiom “make history”

When we say someone has “made history,” we mean that they have done something significant or memorable that will be remembered for a long time. This idiom is often used to describe people who have achieved great things, such as inventors, explorers, or leaders. However, there are many variations of this idiom that can be used in different contexts.

One common variation is to say that someone has “made sports history.” This is used when an athlete or team accomplishes something remarkable in their sport, such as breaking a record or winning a championship. For example, Michael Phelps made sports history by winning 23 Olympic gold medals.

Another variation is to say that someone has “made music history.” This is used when a musician or band creates a song or album that becomes incredibly popular and influential. For example, The Beatles made music history with their innovative sound and cultural impact.

In addition to these specific variations, the phrase “make history” can also be used more broadly to describe any significant accomplishment. For example, if someone starts a successful business or makes an important scientific discovery, they could be said to have made history in their field.

Synonyms, Antonyms, and Cultural Insights for the Idiom “make history”

Some synonyms for “make history” include “leave a mark,” “create a legacy,” and “forge new ground.” These expressions convey the idea of making an impact on society or leaving behind something significant. In contrast, some antonyms for “make history” might be “fade into obscurity,” “be forgotten,” or “go unnoticed.” These phrases suggest a lack of impact or significance in one’s actions.

Cultural insights into the usage of this idiom reveal that it is often associated with moments of great importance in human history. For example, individuals who make significant contributions to science, politics, or culture may be said to have made history. Additionally, events such as wars or revolutions are often described as moments when people make history by changing the course of human events.

Practical Exercises for the Idiom “make history”

Exercise 1: Write a short paragraph about a historical event that has had a significant impact on society. Use the idiom “make history” in your paragraph to describe the event’s significance. For example, “The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg made history by revolutionizing communication and education.”

Exercise 2: Watch a documentary or read an article about a person who has made history through their achievements or actions. Take notes on how they have impacted society and use the idiom “make history” to describe their contributions. For instance, “Nelson Mandela made history by leading South Africa out of apartheid and promoting equality for all.”

Exercise 3: Have a conversation with someone about current events or recent developments in technology, politics, or culture. Use the idiom “make history” to discuss how these events may impact future generations. For example, “The COVID-19 pandemic will make history as one of the most significant global health crises of our time.”

By completing these exercises, you can gain a deeper understanding of how to use the idiom “make history” correctly in various contexts. With practice, you can become more confident in using this expression naturally when speaking or writing in English.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Using the Idiom “make history”

When using the idiom “make history,” it is important to understand its meaning and usage in context. However, there are common mistakes that people make when using this phrase that can lead to confusion or misunderstanding.

One mistake is using the phrase too broadly or loosely. While “making history” can refer to any significant event or achievement, it typically implies a lasting impact on society or culture. Therefore, it is important to consider whether an accomplishment truly has historical significance before using this phrase.

Another mistake is failing to provide context for the use of this idiom. Without proper context, it may be unclear what specific event or accomplishment is being referred to as making history. Providing background information and details can help clarify the meaning and importance of this phrase.

Additionally, some people may use “making history” in a hyperbolic or exaggerated way. This can diminish the significance of actual historical events and accomplishments, leading to confusion about what truly constitutes making history.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Terms and Conditions

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The People Who Decide What Becomes History

By Louis Menand

“It was at Rome, on the 15th of October 1764, as I sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the barefooted friars were singing vespers in the Temple of Jupiter, that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the city first started to my mind.” Those are the words of Edward Gibbon, and the book he imagined was, of course, “ The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire .”

The passage is from Gibbon’s autobiography, and it has been quoted many times, because it seems to distill the six volumes of Gibbon’s famous book into an image: friars singing in the ruins of the civilization that their religion destroyed. And maybe we can picture, as in a Piranesi etching, the young Englishman (Gibbon was twenty-seven) perched on the steps of the ancient temple, contemplating the story of how Christianity plunged a continent into a thousand years of superstition and fanaticism, and determining to make that story the basis for a work that would become one of the literary monuments of the Enlightenment.

Does it undermine the gravitas of the moment to know that, as Richard Cohen tells us in his supremely entertaining “ Making History: The Storytellers Who Shaped the Past ” (Simon & Schuster), Gibbon was obese, stood about four feet eight inches tall, and had ginger hair that he wore curled on the side of his head and tied at the back—that he was, in Virginia Woolf’s words, “enormously top-heavy, precariously balanced upon little feet upon which he spun round with astonishing alacrity”? Does it matter that Gibbon’s contemporaries called him Monsieur Pomme de Terre, that James Boswell described him as “an ugly, affected, disgusting fellow,” and that he suffered from, in addition to gout, a distended scrotum caused by a painful swelling in his left testicle, which had to be regularly drained of fluid, sometimes as much as three or four quarts? And that when, late in life, he made a formal proposal of marriage, the woman he addressed burst out laughing, then had to summon two servants to help him get off his knees and back on his feet?

Cohen thinks that it should matter, that we cannot read “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” properly unless we know the person who wrote it, scrotal affliction and all. Gibbon would not, in theory, at any rate, have disagreed. “Every man of genius who writes history,” he maintained, “infuses into it, perhaps unconsciously, the character of his own spirit. His characters . . . seem to have only one manner of thinking and feeling, and that is the manner of the author.” When we listen to a tale, we need to take into account the teller.

“Making History” is a survey—a monster survey—of historians from Herodotus (the father of lies, in Plutarch’s description) to Henry Louis Gates, Jr. , sketching their backgrounds and personalities, summarizing their output, and identifying their agendas. Cohen’s coverage is epic. He writes about ancient historians, Islamic historians, Black historians, and women historians, from the first-century Chinese historian Ban Zhao to the Cambridge classicist Mary Beard. He discusses Japanese and Soviet revisionists who erased purged officials and wartime atrocities from their nations’ authorized histories, and analyzes visual works like the Bayeux Tapestry, which he calls “the best record of its time, pictorial or otherwise,” and Mathew Brady’s photographs of Civil War battlefields. (“In effect,” he concludes, “they were frauds.”)

[ Support The New Yorker’s award-winning journalism. Subscribe today » ]

He covers academic historians, including Leopold von Ranke, the nineteenth-century founder of scientific history; the Annales school, in France; and the British rivals Hugh Trevor-Roper and A. J. P. Taylor. He considers authors of historical fiction, including Shakespeare, Walter Scott, Dickens, Tolstoy, Toni Morrison, and Hilary Mantel. He writes about journalists; television documentarians (he thinks Ken Burns’s “most effective documentaries rank with many of the best works of written history from the last fifty years”); and popular historians, like Winston Churchill, whose history of the Second World War made him millions, even though it was researched and partially written by persons other than Winston Churchill.

Cohen is English, and was the director of two London publishing houses, biographical facts that, to apply his own test, might account for (a) his willingness to treat journalism, historical fiction, and television documentaries on a par with the work of professional scholars, since, as a publisher, he is interested in work that has an audience and an influence, and (b) the Anglocentrism of his choices. American readers may feel that writers from the United Kingdom are overrepresented, although that list does include historians whose careers were spent largely in American universities, such as Simon Schama, Tony Judt, and Niall Ferguson. But “Making History” is a book, not an encyclopedia, and whatever Cohen writes about he writes about with brio. As the song goes, “If you want any more, you can sing it yourself.”

A very good thing about “Making History” is that, despite the book’s premise, it is not reductive or debunking. Except when Cohen is discussing writers like the nationalist revisionists, whose bias is blatant and who aim to deceive, and some Islamic historians, who he thinks are dogmatic and intolerant, he tries to present a balanced case and allow readers to make their own judgments. The message is not “They’re all untrustworthy.” It’s that bias in history-making is as inevitable as point of view. You cannot not have it.

One area where Cohen may not have achieved an ideal degree of detachment is Marxism, which he handles with bristly animosity and whose principles he misrepresents by confusing Marxism with Stalinism. He accuses Marx of failing to foresee the rise of fascism and the welfare state, which is ridiculous. Who did foresee those things in 1848?

There is a cost to this animus, since Marxist thought played a big role in the work of twentieth-century historians, particularly in the United Kingdom. Still, even here, Cohen tries to be catholic. He plainly feels affection for the British historian Eric Hobsbawm, who joined the Communist Party in 1936 (bad enough) and remained a member for fifty-five years (surreal).

“Making History” is a loaf with plenty of raisins. We learn (or I learned, anyway) that Vladimir Putin’s grandfather was Lenin’s and Stalin’s cook, that Napoleon was about average in height, that Ken Burns is a descendant of the poet Robert Burns, and that when the Marxist critic György Lukács was arrested following the outbreak of the Hungarian Revolution and was asked if he was carrying a weapon, he handed over his pen. (That anecdote is a little neat. I had to take it with a grain of salt—but I took it.)

He is not sloppy, exactly, but he can be a bit breezy. Cornel West was not the director of the African and African American Studies program at Harvard, and Jill Lepore does not come from “a privileged family.” And there are (inevitably) assertions one could quarrel with. Cohen thinks, for example, that “oral history is no more prone to making things up or changing the past to suit the present than is written history.” This has not been my experience. You always have to fact-check what people say, not because they lie deliberately (although Andy Warhol lied in pretty much every interview he ever gave) but simply because we don’t remember things accurately. It’s like when you’re searching for a picture in your photo library: “I was sure it was in 2008 that we visited the Grand Canyon!” But it was in 2009. Mistaken recollections of this sort are common in oral histories and interviews because people generally have no stake in getting dates right. Historians do, though.

Link copied

Cohen likes journalistic histories, books written by reporters who were witnesses to some of the events they describe. (One omission here is William Shirer’s “ The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich ,” which, with its Gibbonesque title, won a National Book Award and sold a million hardcover copies.) He thinks that journalists, if they aspire to be objective, can get “pretty close to the truth.” But, he adds, “what one needs is time to judge that truth in the cold cast of thought.”

This is the traditional “first draft of history” definition of journalism, and part of the belief that our understanding of the past improves with time. I wonder if this is really true, though. Maybe we’re just smoothing the rough edges, losing some bits of what actually happened in order to get the story the way we want it. As history’s first responders, journalists may be more reliable because they are not usually working under the spell of a theory (though Shirer had one). They are describing what happened. Like any other historian, they are trying to produce a coherent narrative, but they don’t need to subsume every fact under a thesis. They also have a better sense of something that no subsequent student of the past can really know and that gets harder and harder to reconstruct: what it felt like.

It’s striking how often this concept—“what it felt like”—turns up in “Making History” as the true goal of historical reconstruction. “The historian will tell you what happened,” E. L. Doctorow said. “The novelist will tell you what it felt like.” Cohen quotes Hilary Mantel: “If we want added value—to imagine not just how the past was, but what it felt like, from the inside—we pick up a novel.”

We expect novelists to make this claim. They can describe what is going on in characters’ heads and what characters are feeling, which historians mostly cannot, or should not, do. But historians want to capture what it felt like, too. For what they are doing is not all that different from what novelists are doing: they are trying to bring a vanished world to life on the page. Novelists are allowed to invent, and historians have to work with verifiable facts. They can’t make stuff up; that’s the one rule of the game. But they want to give readers a sense of what it was like to be alive at a certain time and place. That sense is not a fact, but it is what gives the facts meaning.

This is what G. R. Elton, the historian of Tudor England, seems to have meant when he described history as “imagination, controlled by learning and scholarship, learning and scholarship rendered meaningful by imagination.” A German term for this (which Cohen misattributes to Ranke) is Einfühlungsvermögen , which Cohen defines as “the capacity for adapting the spirit of the age whose history one is writing and of entering into the very being of historical personages, no matter how remote.” A simpler translation would be “empathy.” It’s in short supply today. We live in a judgy age, and judgments are quick. But what would it mean to empathize with a slave trader? Is understanding a form of excusing?

History writing is based on the faith that events, despite appearances, don’t happen higgledy-piggledy—that although individuals can act irrationally, change can be explained rationally. As Cohen says, Gibbon thought that, as philosophy was the search for first principles, history was the search for the principle of movement. Many Western historians, even “scientific” historians, like Ranke, assumed that the past has a providential design. Ranke spoke of “the hand of God” behind historical events.

Marxist historians, like Hobsbawm, believe in a law of historical development. Some writers of history, such as those in the Annales school, think that political events do happen pretty much higgledy-piggledy (which is why they are notoriously difficult to predict, although commentators somehow make a living doing just that), but that there are regularities beneath the surface chaos—cycles, rhythms, the longue durée.

Still, history is not a science. Essentially, as A. J. P. Taylor said, it is “simply a form of story-telling.” It’s storytelling with facts. And the facts do not speak for themselves, and they are not just there for the taking. They are, as the English historian E. H. Carr put it, “like fish swimming about in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean; and what the historian catches will depend, partly on chance, but mainly on what part of the ocean he chooses to fish in and what tackle he chooses to use—these two factors being, of course, determined by the kind of fish he wants to catch. By and large, the historian will get the kind of facts he wants.”

It’s interpretation all the way down. The lesson to be drawn from this, I think, is that the historian should never rule anything out. Everything, from the ownership of the means of production to the color that people painted their toenails, is potentially relevant to our ability to make sense of the past. The Annales historians called this approach “total history.” But, even in total history, you catch some fish and let the others go. You try to get the facts you want.

And what do historians want the facts for? The implicit answer of Cohen’s book is that there are a thousand purposes—to indoctrinate, to entertain, to warn, to justify, to condemn. But the purpose is chosen because it matters personally to the historian, and it is, almost always, because it matters to the historian that the history that is produced matters to us. As Cohen says, it is a great irony of writing about the past that “any author is the prisoner of their character and circumstances yet often they are the making of him.”

What history never does is provide an impersonal and objective account of past events. As the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss once put it (dismissively), all history is “history-for.” What did Gibbon write the “Decline and Fall” for? Cohen says it was to warn eighteenth-century Britain of mistakes that might threaten its empire, to prevent it from suffering the fate of Rome. In other words, Gibbon thought his story could be useful. He therefore needed to portray Roman civilization in ways that Britons could identify with, and Christianity in ways that suited the anticlerical prejudices of the Age of Reason. And what about the poor fellow’s body and its sad infirmities? Cohen thinks (as Woolf did) that his unattractiveness provided Gibbon with an impenetrable cloak of irony. He learned to keep his emotional expectations in check, and this made him a cool analyst of religious zeal.

Lévi-Strauss maintained that history in modern societies is like myth in pre-modern cultures. It’s the way we explain ourselves to ourselves. The decision about what we want that explanation to look like can begin with the simple act of picking the date we want the story to start. Is it 1603 or 1619? We choose one of those years, and events line up accordingly. People complain that this makes history ideological. But what else could it be? “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” is ideological through and through. No one thinks it’s not history. Certainly Gibbon never doubted it. “Shall I be accused of vanity,” he wrote in his will, “if I add that a monument is superfluous?” ♦

New Yorker Favorites

A prison therapist grapples with a sex offender’s release .

What have fourteen years of conservative rule done to Britain ?

Woodstock was overrated .

Why walking helps us think .

A whale’s strange afterlife .

The progressive politics of Julia Child .

I am thrilled to announce that nothing is going on with me .

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Idrees Kahloon

By Adam Gopnik

By Eyal Press

By Evan Osnos

make history

- Take our quick quizzes to practise your vocabulary.

- We have thousands of six-question quizzes to try.

- Choose from collocations, synonyms, phrasal verbs and more.

Explore topics

- Earth sciences

- Engineering

make history

- 1.1 Pronunciation

- 1.2.1 Translations

- 1.2.2 See also

Pronunciation

| Audio ( ): | ( ) |

make history ( third-person singular simple present makes history , present participle making history , simple past and past participle made history )

- ( idiomatic ) To do something that will be widely remembered for a long time. Neil Armstrong made history in 1969 when he was the first person to walk on the Moon.

Translations

| / (chuàngzào lìshǐ) , , (tvorítʹ istóriju), (délatʹ istóriju), (vojtí v istóriju) , |

- go down in history

- English terms with audio links

- English lemmas

- English verbs

- English multiword terms

- English idioms

- English terms with usage examples

- English light verb constructions

- English predicates

- English terms with non-redundant non-automated sortkeys

- English entries with language name categories using raw markup

- Mandarin terms with redundant transliterations

- Terms with Mandarin translations

- Terms with Finnish translations

- Terms with French translations

- Terms with Italian translations

- Terms with Polish translations

- Terms with Russian translations

- Terms with Spanish translations

- Terms with Swedish translations

Navigation menu

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

This course changed how I see the world

That old ‘Gatsby’ magic, made new

American Dream turned deadly

Ulrich explains that well-behaved women should make history.

FAS Communications

Most bumper sticker slogans do not originate in academic publications. However, in the 1970s, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich penned in a scholarly article about the funeral sermons of Christian women that “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” The phrase subsequently gained wide popularity, appearing on T-shirts, coffee mugs, and other items — and it’s now the title of Ulrich’s latest book.

The new book explores how and why it is that women who act in unexpected ways tend to be remembered, while more conventional women fade into the past. Ulrich breaks down the traditional good girl/bad girl stereotypes, and shows that women — and men — who make history are, in fact, multidimensional and should not be constrained by such a polarizing formulation.

“This phrase began in a scholarly context, and moved into popular culture,” says Ulrich, 300th Anniversary University Professor in the Department of History in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “This book responds to that curious situation, and, because of the popularity of the slogan, it offers an opportunity to reach out to those who might not take a history course, and encourage them to ask new questions about the nature of history.”

Ulrich examines the lives of three women from very different times: Christine de Pizan, who lived in a 15th century French court and wrote “The City of Ladies,” a book of women’s biographies; the 19th century suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton; and 20th century writer Virginia Woolf. For these women — who were not historians — history was integral to their own thought and work, and they went on to make history themselves.

In “Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History” (Knopf, September 2007), Ulrich examines a pivotal moment in each of these women’s lives, describing ways in which they broke with conventional behavior in order to re-create themselves and make a place in history. For Christine de Pizan, the moment was when she included Amazons, or women warriors, in “The City of Ladies.” For Stanton it was an encounter with a runaway slave that helped shape her position on women’s suffrage. And for Woolf, it was the creation of Shakespeare’s gifted, imaginary sister and the trials that she would have faced as a female writer.

Each of these women struggled to answer scholarly and historical questions that, because of the contemporary lack of scholarship on women’s history, they could not adequately address in their own times. Utilizing the tools produced by the remarkable flourishing of women’s history scholarship over the past 30 years, Ulrich takes a new look at the questions raised by the three women during three very different historical periods.

While telling the stories of these history-making women, Ulrich illuminates the intended meaning behind the slogan that is the title of her book. When the slogan appears out of context, it becomes open to wide interpretation, and has, subsequently, been used as a call to activism and sensational — even negative — behavior. In fact, Ulrich says, the phrase points to the reasons that women’s lives have limited representation in historical narrative, and she goes on to look at the type of people and events that do become public record.

Throughout history, “good” women’s lives were largely domestic, notes Ulrich. Little has been recorded about them because domesticity has not previously been considered a topic that merits inquiry. It is only through unconventional or outrageous behavior that women’s lives broke outside of this domestic sphere, and therefore were recorded and, thus, remembered by later generations. Ulrich points out that histories of “ordinary” women have not been widely known because historians have not looked carefully at their lives, adding that by exploring this facet of our past, we gain a richer understanding of history.

“People express such surprise when they discover that women have a history. It is liberating that the past can not be reduced to such stereotypes,” says Ulrich. “I hope that someone would take away from this book that ordinary people could have an impact, and to try doing the unexpected. I would like to show that history is something that one can contribute to.”

Share this article

You might like.

A photographer’s love letter to ‘Vision and Justice’

Fitzgerald’s masterpiece, now the inspiration for a new A.R.T. musical, never reads the same

He just needs to pass the bar now. But blue-collar Conor’s life spirals after a tangled affair at old-money seaside enclave in Teddy Wayne’s literary thriller

Bringing back a long extinct bird

Scientists sequence complete genome of bush moa, offering insights into its natural history, possible clues to evolution of flightless birds

Women who follow Mediterranean diet live longer

Large study shows benefits against cancer, cardiovascular mortality, also identifies likely biological drivers of better health

Harvard-led study IDs statin that may block pathway to some cancers

Cholesterol-lowering drug suppresses chronic inflammation that creates dangerous cascade

- Words with Friends Cheat

- Wordle Solver

- Word Unscrambler

- Scrabble Dictionary

- Anagram Solver

- Wordscapes Answers

Make Our Dictionary Yours

Sign up for our weekly newsletters and get:

- Grammar and writing tips

- Fun language articles

- #WordOfTheDay and quizzes

By signing in, you agree to our Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy .

We'll see you in your inbox soon.

Make-history Definition

Make-history sentence examples.

Many modern authors have attempted to make history out of these stories, and have created an old Bactrian empire of great extent, the kings of which had won great victories over the Turanians.

The last, in regulated forms, are a permanent feature of Catholicism; and the rivalries of these " regular " clergy with their " secular" or parochial brethren continue to make history to-day.

We purchased a fawn bitch sired by make history called Historic Lady (Faith) who was our foundation bitch in 1971.

The site has webcasts, timelines and interactive features to make history come alive.

The museum strives to make history enjoyable to children as well by providing an activity pamphlet that they can complete during the tour.

Related Articles

Make-history Is Also Mentioned In

- made-history

- making-history

- makes-history

Find Similar Words

Find similar words to make-history using the buttons below.

Words Starting With

Words ending with, unscrambles, words starting with m and ending with y, word length, words near make-history in the dictionary.

- make it count

- make it do or do without

- make it one's business

- make-head-against

- make-head-or-tail-of

- make-headway

- make-heavy-weather-of

- make-history

What is history?

What is history? History is the study of the past, particularly people and events of the past. It is a pursuit common to all human societies and cultures. Human beings have always been interested in understanding and interpreting the past, for many reasons. While there is broad agreement on what history actually is, there is much less agreement on how it should be constructed and what it should focus on.

Stories, identities and context

History can take the form of a tremendous story, a rolling narrative filled with great personalities and tales of turmoil and triumph. Each generation adds its own chapters to history while reinterpreting and finding new things in those chapters already written.

History provides us with a sense of identity. By understanding where we have come from, we can better understand who we are. History provides a sense of context for our lives and our existence. It helps us understand the way things are and how we might approach the future.

History teaches us what it means to be human, highlighting the great achievements and disastrous errors of the human race. History also teaches us through example, offering hints about how we can better organise and manage our societies for the benefit of all.

History versus ‘the past’

Those new to studying history often think history and the past are the same thing. This is not the case. The past refers to an earlier time, the people and societies who inhabited it and the events that took place there. History describes our attempts to research, study and explain the past.

This is a subtle difference but an important one. What happened in the past is fixed in time and cannot be changed. In contrast, history changes regularly. The past is concrete and unchangeable but history is an ongoing conversation about the past and its meaning.

The word history and the English word story both originate from the Latin historia , meaning a narrative or account of past events. History is itself a collection of thousands of stories about the past, told by many different people.

Revision and historiography

Because there are so many of these stories, they are often variable, contradictory and conflicting. This means history is subject to constant revision and reinterpretation. Each generation looks at the past through its own eyes. It applies different standards, priorities and values and reaches different conclusions about the past.

The study of how history differs and has changed over time is called historiography.

Like historical narratives themselves, our understanding of what history is and the shape it should take is flexible and open to debate. For as long as people have studied history, historians have presented different ideas about how the past should be studied, constructed, written and interpreted.

As a consequence, historians may approach history in different ways, using different ideas and methods and focusing on or prioritising different aspects. The following paragraphs discuss several popular theories of history.

Great individuals

According to the ancient Greek writer Plutarch, history is primarily the study of great leaders and innovators. Prominent individuals shape the course of history through their personality, character, ambition, abilities, leadership or creativity – or conversely, their errors of judgement and failures.

Plutarch’s own histories were written almost as biographies or ‘life-and-times’ stories of these individuals. They explained how the actions of these great figures shaped the course of their nations or societies.

Plutarch’s approach served as a model for many later historians. It is sometimes referred to as ‘top-down’ history because of its focus on rulers or leaders.

One advantage of this approach is its accessibility and relative ease. Researching and writing about individuals is less difficult than investigating more complex factors, such as social movements or long-term changes. The Plutarchian focus on individuals can also more interesting and accessible to readers, who many prefer reading about people to abstract concepts.

The main problem with this approach is that it can sidestep, simplify or overlook historical factors and conditions that do not emanate from important individuals, such as economic changes, social conditions or popular unrest.

The winds of change

Other historians focus less on individuals and taken a more thematic approach, by looking at factors and forces that produce significant historical change. Some focus on what might broadly be described as the ‘winds of change’: powerful ideas, forces and movements that shape or affect how people live, work and think.

These great ideas and movements are often initiated or driven by influential people – but they become much larger forces for change. As these winds of change develop and grow, they shape or influence political, economic and social events and conditions.

One example of a notable ‘wind of change’ was Christianity, which shaped government, society and social customs in medieval Europe. Another was the European Enlightenment that undermined old ideas about politics, religion and the natural world. This triggered a long period of curiosity, education and innovation.

Marxism emerged in the late 19th century and grew to challenge the old order in Russia, China and elsewhere, shaping government and society in those nations. The Age of Exploration, the Industrial Revolution, decolonisation in the mid-1900s and the winding back of eastern European communism in the late-1900s are all tangible examples of the ‘winds of change’.

Challenges and responses

Some historians, such as British writer Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975), believed historical change is driven by challenges and responses. Civilisations are defined not just by their leadership or conditions but by how they respond to difficult problems or crises.

These challenges take many forms. They can be physical, environmental, economic or ideological. They can derive from internal pressures or external factors. They can come from their own people or from outsiders.

The survival and success of civilisations are determined by how they respond to these challenges. This itself often depends on its people and how creative, resourceful, adaptable and flexible they are.

Human history is filled with many tangible examples of challenge and response. Many nations have been confronted with powerful rivals, wars, natural disasters, economic slumps, new ideas, emerging political movements and internal dissent.

The process of colonisation, for example, involved major challenges, both for colonising settlers and native inhabitants. Economic changes, such as new technologies and increases or decreases in trade, have created challenges in the form of social changes or class tensions.

The study of dialectics

In philosophy, dialectics is a process where two or more parties with vastly different viewpoints reach a compromise and mutual agreement. The theory of dialectics was applied to history by German philosopher Georg Hegel (1770-1831).

Hegel suggested that most historical changes and outcomes were driven by dialectic interaction. According to Hegel, for every thesis (a proposition or idea) there exists an antithesis (a reaction or opposite idea). The thesis and antithesis encounter or struggle, from which emerges a synthesis (a new idea).

This ongoing process of struggle and development reveals new ideas and new truths to humanity. The German philosopher Karl Marx (1818-1883) was a student of Hegel and incorporated the Hegelian dialectic into his own theory of history – but with one important distinction.

According to Marx, history was shaped by the material dialectic: the struggle between economic classes. Marx believed the ownership of capital and wealth underpinned most social structures and interactions. All classes struggle and push to improve their economic conditions, Marx wrote, usually at the expense of other classes.

Marx’s material dialectic was reflected in his stinging criticisms of capitalism, a political and economic system where the capital-owning classes control production and exploit the worker, in order to maximise their profits.

The surprising and unexpected

Some historians believe history is shaped by the accidental and the surprising, the spontaneous and the unexpected.

While history and historical change usually follow patterns, they can also be unpredictable and chaotic. Despite our fascination with timelines and linear progression, history does not always follow a clear and expected path. The past is filled with unexpected incidents, surprises and accidental discoveries.

Some of these have unleashed historical forces and changes that could not be predicted, controlled or stopped. A few have come at pivotal times and served as the ignition or ‘flashpoint’ for changes of great significance. The discovery of gold, for example, has triggered gold rushes that shaped the future of entire nations.

In June 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand’s car took a different route through Sarajevo and passed an aimless Gavrilo Princip, a confluence of events that led to World War I.

American historian Daniel Boorstin (1914-2004), an exponent of this fascination with historical accidents, once claimed that if Cleopatra’s nose had been shorter, diminishing her beauty, then the history of the world might have been radically different.

Citation information Title: ‘What is history?’ Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn , Steve Thompson Publisher: Alpha History URL: https://alphahistory.com/what-is-history/ Date published: September 23, 2020 Date updated: November 3, 2023 Date accessed: June 11, 2024 Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use .

Synonyms for Make history

135 other terms for make history - words and phrases with similar meaning.

Alternatively

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- By what other term are the kings of Egypt called?

- Is ancient Greece a country?

- Was ancient Greece a democracy?

- Why is ancient Greece important?

- Who was the first king of ancient Rome?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Alpha History - What is history?

- History Today - What is History?

- Valdosta State University - What is History? How do Historians study the past as contrasted with Non-historians?

- University of Massachusetts Amherst - The Discipline of History

- Chemistry LibreTexts - History

- history - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- history - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Recent News

history , discipline that studies the chronological record of events, usually attempting, on the basis of a critical examination of source materials, to explain events.

For the principal treatment of the writing of history, and the scholarly research associated with it, see historiography . There are many branches of the study of history, among them world history , intellectual history , social history , economic history , and art history . The term philosophy of history refers to the study of how history as a discipline is practiced and how historians understand and explain the past.

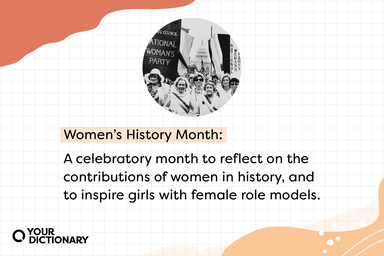

History, as a discipline, is traditionally centred on peoples, cultures , countries, and regions, but everything has a history that can be described and studied. Examples of these histories include deaf history , the history of movies , the history of Arabia , the history of science , the geologic history of Earth , the history of the organization of work , the history of logic , the history of early Christianity , and the history of coffee , among many others. History is also celebrated through commemorations such as Black History Month and Women’s History Month .

- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

How to List Education on a Resume: Tips, Examples, and More

Learn how to highlight your education to make your resume shine.

![make history meaning [Featured image] A woman adds an education section to her resume.](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/4gaGhZRGE3Qva8WOpIASCb/bad90ad977b1300fb46978f6093cdfbc/GettyImages-477723122.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

The education section of your resume helps potential employers build a picture of your qualifications for the job. Some roles may even require a particular degree, and your resume is the best place to show that you have it.

In this article, we’ll discuss how to format the education section of your resume (and where you should position it), as well as walk through some specific educational situations.

How to format the education section of your resume

There’s more than one way to format your education section, depending on the amount of work experience you have and what details may be most relevant to the job. For each school you have attended, consider including some combination of the following (always include the three bolded items):

School name

Degree obtained

Dates attended or graduation date

Field of study (major and minors)

GPA if it was above 3.5

Honors, achievements, relevant coursework, extracurricular activities, or study abroad programs

Here are some tips to keep in mind as you format this section of your resume:

1. List in reverse chronological order.

Rank your highest degrees first and continue in reverse chronological order. And remember, when ranking your educational achievements, it’s not necessary to list your high school graduation if you have completed a college degree. If you haven't completed college, list your high school education.

2. Make it relevant.

Employers want to see that your education meets the requirements listed in their job post. They will also look to see that you have the certifications they require for the job. Study the job listing for the role you’re applying for to help guide what to highlight. Make sure to include anything listed under the “requirements” or “education” sections of a job listing.

If you’re applying for a nursing job, for example, you may be required to have a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) . Since the field of study is key, you may choose to list your degree first and institution second, like this:

Bachelor of Science in Nursing, 2019

Arizona State University | Tempe, AZ

If your degree isn’t particularly relevant to the job but you graduated from a prestigious university, consider listing the institution name first:

Dartmouth College | Hanover, NH

Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy, 2006-2010

3. Consider your work experience.

In general, the more work experience you have, the less detail you’ll need to include in the education section of your resume. If you just graduated, for example, you may choose to include your GPA and highlight that you were the president of the National Honor Society (particularly if you’re applying for a job where leadership skills are important). If you’ve been in the workforce for several years, the school name, location, and degree will likely suffice.

If you graduated more than five years ago, consider leaving off your graduation date to help avoid age discrimination.

4. Keep your formatting consistent.

While there are many different ways to format the contents of your education, consistency between each is key. Once you decide on a format, stick with it for your entire resume.

5. Keep it concise.

In many cases, the education section should be one of the shortest on your resume.

How to handle unique education situations

While many resumes will have straightforward education sections, some will have an incomplete or complex education history. Thankfully, there are easy ways to ensure that your resume showcases your positive qualities and qualifications.

Incomplete education

If your resume includes any incomplete education, it’s important to avoid words like “unfinished” or “incomplete” as they could cast a negative shadow over your qualifications.

If you’re in the process of completing your degree, include your expected graduation date. This lets employers know that you are still working on your degree while avoiding any confusion or misrepresentation of your qualifications. For example:

University of Michigan

BS in Computer Science candidate

Expected to graduate in 2023

If you’re wondering how to list education on your resume when you don’t have a degree, there’s a format for that, too. Say you’ve completed part of a degree, but do not intend to finish. You can still use it on your resume. List the number of credit hours completed toward a degree in place of graduation date, and include any courses relevant to the job you’re applying for.

Completed 30 credit hours toward a BS in Computer Science

Relevant coursework: Web development, Object-oriented programming, Agile software projects

If you have not attended college but have completed trade school or a certification program, it’s good to include that information under the education section of your resume. Listing certifications as a graduate can be beneficial, too. This shows employers that you are continually learning and staying up to date with trends and technology.

Complex educational history

Whether you attended multiple schools to earn one degree or earned multiple degrees from multiple schools, listing your education is only as complex as its formatting.

Attending a few different colleges before landing at the one you graduated from does not mean you have to list every school. Employers are mainly interested in the school from which your degree was earned . It is, however, a good idea to list every school that you have received a degree from.

If you have earned multiple degrees at the same level, you should list all of them. In terms of order, it is okay to list either your most recent or most relevant first.

Where to place your education section

Where you place the education section on your resume depends on a few different factors: your education history, your work history, and the job for which you are applying.

If you are a recent graduate with minimal work history, it’s appropriate to list your education first. Education will be your more impressive section, and you’ll want it to be the first seen when employers are viewing your application.

If you are pursuing a job that requires a particular degree or credential , you should also list your education first. Employers will be interested in making sure you have those certifications before moving forward with your resume.

If you’ve been working for several year s, your work history is likely more relevant than your education history, so it may make sense to list it first. This is particularly true if the field of study of our degree isn’t particularly relevant to the job or industry you’re targeting.

Resume vs. curriculum vitae

If you’re applying for a PhD or research program or a job in academia, you may be asked to submit a curriculum vitae, or CV, instead of a resume. If this is the case, your education section should come before your work experience. CVs are generally longer than resumes, so you can include your complete academic history, including all certifications and achievements. Read more : What Is a CV? And How Is It Different from a Resume?

Next steps

A resume is an important document intended to organize and exemplify your education history, work experience, qualifications, and skills. Don’t forget to include your completed Coursera courses or certificates to your resume.

And, if you're interested in learning more about how to craft a stand out resume, consider taking the Writing Winning Resumes and Cover Letters from the University of Maryland College Park. In just twelve hours, you'll learn how to convert a boring resume into a dynamic asset statement that conveys your talents in the language that employers actually understand.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

A look back at D-Day: Why the World War II invasion remains important on its 80th anniversary

Eighty years ago, the d-day invasion on june 6, 1944 didn't play out perfectly. but officers and troops "sized up the situation, saw what had to be done, and did it," wrote historian stephen ambrose..

Eighty years after it happened, D-Day – the largest land, sea and air invasion ever attempted – still resonates today.

With the bold invasion of Nazi-held Europe on June 6, 1944, the Allied forces began turning the tide in World War II. On this 80th anniversary of that date, it is good to remember that it's "one of the most famous single days in all of human history," writes historian Garrett Graff in his new book out this week, "When the Sea Came Alive: An Oral History of D-Day."

"Though there have been other days over the course of the last century that have re-routed our collective historical trajectory, one could argue that none has had more of an impact than the day 160,000 troops stormed the beaches of Normandy," he writes.

In addition to feelings of gratitude, this 80th anniversary also evokes feelings of melancholy "as we also mark the final passing of the Greatest Generation and the event slips fully from memory into history," Graff told USA TODAY.

"Of the million or so Allied participants in Operation Overlord, there are only a few thousand left alive today," he said. "That means that the memories and first-person experiences we have of D-Day now are, effectively, all the memories we will ever have."

Here's everything to know about D-Day and why it's still so important today.

D-Day remembrance: World War II veterans return to Normandy on 80th anniversary of invasion.

What is D-Day? When did it happen?

It would be more than four years into World War II – Germany's invasion of Poland in September 1939 set off the global conflict – when the major Allied forces including the U.S., Great Britain, France and Russia sought an invasion to weaken an already spread-thin German army, according to History.com .

The operation involving the largest sea and air armada ever assembled, Graff notes in his book, had been in the works for years.

Crucial preparation began in December 1943 after President Franklin D. Roosevelt named General Dwight D. Eisenhower the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, notes the National World War II Museum .

Why is D-Day still important today?

It's simple, President Clinton said during events observing the 50th anniversary in France . "They gave us our world," he said.

Those troops who executed the invasion "mean everything to us," said Sgt. Nathan Rogers, a 23-year-old Army Ranger at the time attending the ceremony. "We wouldn't have existed if not for them. They definitely set the standard."

In collecting more than 5,000 personal stories of participants in D-Day in writing his new book, Graff said he learned crucial insights from the participants.

"Sure, we recognize now that D-Day was a Herculean heroic triumph, but listen to the voices of the Allied troops crossing the Channel on an armada of ships on the night of June 5th and there’s little sense that what they’re doing is historic or heroic," he said. "They have no idea what lies ahead. They’re concerned about whether they’ll live to see the end of the day."

What does D-Day stand for?

The answer is simpler than you might think. The D actually stands for "Day," because it is a coded designation used for the day of any important invasion or military operation. So actions four days ahead of the actual operation, for instance, would be D-4, according to the U.S. Army .

What was Operation Overlord?

Operation Overlord, the code name for the D-Day invasion, involved transporting of more than 150,000 infantry troops across the English Channel into German-occupied France.

More than 1.5 million U.S. Army personnel had arrived in the U.K. by the end of May 1944 to participate or support the operation, according to the National World War II Museum . Overall, more than 2 million soldiers from the U.S. and 250,000 from Canada had arrived by June in preparation for, and to support, the invasion, according to History.com . Also delivered: 450,000 tons of ammunition as part of 7 million tons of supplies.

Operation Overlord also contained a fake operation called Operation Fortitude to convince Hitler the Allies would attempt to land in Norway and Pas-de-Calais in France, according to the Imperial War Museum . The plot, concocted over months, included a fake army, led by General George Patton, and readying in England for the channel crossing, notes History.com .

Another fictitious force, the British Fourth Army, stationed in Scotland to threaten Norway where Hitler's U-boats were based, "existed only on the airwaves," wrote historian Stephen Ambrose in "D-Day: June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II." British officers and German spies sent realistic radio messages to convince the Germans of the operation's authenticity and wooden fake bombers were deployed.

These ruses were successful enough that Hitler considered the Normandy invasion, as it was initiated, was actually a ploy to divert attention from Calais. "They had placed the bulk of their panzer divisions north and east of the Seine River, where they were unavailable for counterattack in Normandy," wrote Ambrose, who also authored "Band of Brothers."

'The eyes of the world are upon you': Eisenhower's D-Day order inspires 80 years later

Did D-Day go according to plan?

After years of planning for Operation Overlord, soldiers still faced incredible challenges upon landing on the beaches of Normandy as the intricate operation didn't go according to plan.

"Even with … tactical and strategic advantages and more than a year of planning, D-Day’s success was a close call, achieved only at an astounding cost of more than 10,000 Allied troops killed, wounded or missing ," said now-retired Gen. Jeff Harrigian, who penned a D-Day anniversary observance editorial on USATODAY.com in 2021. At the time, Harrigian was the commander of the U.S. Air Forces Europe, U.S. Air Forces Africa and Allied Air Command at Ramstein Air Base in Germany.

Complications began when weather caused cancellation of the original date Eisenhower had chosen, which was June 5, 1944.

Anti-aircraft fire caused pilots to fly planes faster than expected and that meant paratroopers, dropped in the morning behind enemy lines to cut off supply routes, missed their landing targets, History.com details .

During the Allied forces' landing, the U.S. landing force for Utah Beach was blown off course. The U.S. landing at Omaha Beach, where the fiercest fighting was seen, was affected by winds and tide, too.

As troops emerged from landing boats on the long, flat Omaha Beach, they were pinned down by enemy machine-gun fire from the cliffs above. “If you (stayed) there you were going to die,” Lieutenant Colonel Bill Friedman told the National World War II Museum . “We just had to ... try to get to the bottom of the cliffs on which the Germans had mounted their defenses.”

U.S. and British destroyers arrived to attack enemy positions and support the troops including those attempting to commandeer the critical Pointe du Hoc , a German-held clifftop between Omaha and Utah beaches, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command site .

By the end of the day, about 156,000 Allied troops had successfully landed and taken Normandy’s beaches.

How did D-Day succeed?

Operation Overlord involved more than 11,000 planes and more than 5,000 ships and landing craft, along with 50,000 vehicles, according to the National World War II Museum .

"The plan had called for the air and naval bombardments, followed by tanks and dozers, to blast a path through the exits so that the infantry could march up the draws (ravines) and engage the enemy, but the plan had failed, utterly and completely failed," Ambrose wrote. "As is almost always the case in war, it was up to the infantry. It became the infantry's job to open the exits so that the vehicles could drive up the draws and engage the enemy."

Junior officers and noncommissioned officers "saw at once that the intricate plan … bore no relationship whatsoever to the tactical problem they faced," he wrote.

Their training "had prepared them for this challenge. They sized up the situation, saw what had to be done, and did it," Ambrose wrote.

Sgt. John Ellery, of the 16th Infantry Regiment of the First Infantry Brigade, also known as "The Big Red One,” was in the first wave to hit Omaha Beach. He told survivors around him, "we had to get off the beach and that I'd lead the way," and climbed up the bluff to use grenades to take out a machine gun position, Ambrose wrote in "D-Day."

"We sometimes forget, I think, that you can manufacture weapons, and you can purchase ammunition," Ellery is quoted by Ambrose, "but you can't buy valor and you can't pull heroes off an assembly line."

Now many soldiers died on D-Day?

- 4,415 Allied soldiers died on D-Day, with U.S. servicemen accounting for 2,502 of the death and 1,913 Allied soldiers from seven other nations, according to The National D-Day Memorial Foundation .

- Between 4,000 and 9,000 German soldiers were killed, wounded or missing in action.

- About 200,000 German prisoners of war were captured.

- An estimated 12,200 French civilians died or went missing during the battle, according to Encyclopedia Britannica .

The invasion proved successful: Paris was liberated from the Germans on Aug. 25, 1944 and on May 7, 1945, less than a year after the D-Day invasion, Germany surrendered.

Special online D-Day observations

Here are some ways to observe the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

- The National World War II Museum : The museum in New Orleans has events all day on Thursday and you can watch online. The program begins with a remembrance gathering at 6:30 a.m. ET and a performance by the 29th Division Band at 9 a.m. You can register for virtual attendance on the museum's website .

- “Frog Fathers: Lessons from the Normandy Surf ": This new documentary about the history of the Naval Combat Demolition Units, known today as the Navy SEALs, follows four veterans who visit Normandy. The doc is currently available on the Fox Nation streaming service ($7.99 monthly or $59.88 annually after 7-day free trial). Starting Tuesday, June 11, you can watch it on MagellanTV ($5.99 per month or $59.98 per year after a free 7-day or 14-day trial) or on the World of Warships YouTube channel .

- World of Warships: The free historical online naval battle video game has special missions related to the D-Day invasion playable this month on PCs and consoles.

Follow Mike Snider on X and Threads: @mikesnider & mikegsnider .

What's everyone talking about? Sign up for our trending newsletter to get the latest news of the day

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of ensure

transitive verb

Did you know?

Do you ensure or insure ?

There is considerable confusion about whether ensure and insure are distinct words, variants of the same word, or some combination of the two. They are in fact different words, but with sufficient overlap in meaning and form as to create uncertainty as to which should be used when. We define ensure as “to make sure, certain, or safe” and one sense of insure , “to make certain especially by taking necessary measures and precautions,” is quite similar. But insure has the additional meaning “to provide or obtain insurance on or for,” which is not shared by ensure . Some usage guides recommend using insure in financial contexts (as in “she insured her book collection for a million dollars”) and ensure in the general sense “to make certain” (as in “she ensured that the book collection was packed well”).

ensure , insure , assure , secure mean to make a thing or person sure.

ensure , insure , and assure are interchangeable in many contexts where they indicate the making certain or inevitable of an outcome, but ensure may imply a virtual guarantee

, while insure sometimes stresses the taking of necessary measures beforehand

, and assure distinctively implies the removal of doubt and suspense from a person's mind.

secure implies action taken to guard against attack or loss.

Examples of ensure in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'ensure.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle English, from Anglo-French ensurer , alteration of assurer — more at assure

1660, in the meaning defined above

Articles Related to ensure

'Insure' vs. 'Ensure' vs. 'Assure'

How to make sure you're using them right

Dictionary Entries Near ensure

Cite this entry.

“Ensure.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ensure. Accessed 11 Jun. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of ensure, more from merriam-webster on ensure.

Nglish: Translation of ensure for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of ensure for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

What's the difference between 'fascism' and 'socialism', more commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - june 7, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- Resources for You (Food)

- Agricultural Biotechnology

Science and History of GMOs and Other Food Modification Processes

Feed Your Mind Main Page

en Español (Spanish)

How has genetic engineering changed plant and animal breeding?

Did you know.

Genetic engineering is often used in combination with traditional breeding to produce the genetically engineered plant varieties on the market today.

For thousands of years, humans have been using traditional modification methods like selective breeding and cross-breeding to breed plants and animals with more desirable traits. For example, early farmers developed cross-breeding methods to grow corn with a range of colors, sizes, and uses. Today’s strawberries are a cross between a strawberry species native to North America and a strawberry species native to South America.

Most of the foods we eat today were created through traditional breeding methods. But changing plants and animals through traditional breeding can take a long time, and it is difficult to make very specific changes. After scientists developed genetic engineering in the 1970s, they were able to make similar changes in a more specific way and in a shorter amount of time.

A Timeline of Genetic Modification in Agriculture

A Timeline of Genetic Modification in Modern Agriculture

Circa 8000 BCE: Humans use traditional modification methods like selective breeding and cross-breeding to breed plants and animals with more desirable traits.

1866: Gregor Mendel, an Austrian monk, breeds two different types of peas and identifies the basic process of genetics.

1922: The first hybrid corn is produced and sold commercially.

1940: Plant breeders learn to use radiation or chemicals to randomly change an organism’s DNA.

1953: Building on the discoveries of chemist Rosalind Franklin, scientists James Watson and Francis Crick identify the structure of DNA.

1973: Biochemists Herbert Boyer and Stanley Cohen develop genetic engineering by inserting DNA from one bacteria into another.

1982: FDA approves the first consumer GMO product developed through genetic engineering: human insulin to treat diabetes.

1986: The federal government establishes the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology. This policy describes how the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) work together to regulate the safety of GMOs.

1992: FDA policy states that foods from GMO plants must meet the same requirements, including the same safety standards, as foods derived from traditionally bred plants.

1994: The first GMO produce created through genetic engineering—a GMO tomato—becomes available for sale after studies evaluated by federal agencies proved it to be as safe as traditionally bred tomatoes.

1990s: The first wave of GMO produce created through genetic engineering becomes available to consumers: summer squash, soybeans, cotton, corn, papayas, tomatoes, potatoes, and canola. Not all are still available for sale.

2003: The World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations develop international guidelines and standards to determine the safety of GMO foods.

2005: GMO alfalfa and sugar beets are available for sale in the United States.

2015: FDA approves an application for the first genetic modification in an animal for use as food, a genetically engineered salmon.

2016: Congress passes a law requiring labeling for some foods produced through genetic engineering and uses the term “bioengineered,” which will start to appear on some foods.

2017: GMO apples are available for sale in the U.S.

2019: FDA completes consultation on first food from a genome edited plant.

2020 : GMO pink pineapple is available to U.S. consumers.

2020 : Application for GalSafe pig was approved.

How are GMOs made?

“GMO” (genetically modified organism) has become the common term consumers and popular media use to describe foods that have been created through genetic engineering. Genetic engineering is a process that involves:

- Identifying the genetic information—or “gene”—that gives an organism (plant, animal, or microorganism) a desired trait

- Copying that information from the organism that has the trait

- Inserting that information into the DNA of another organism

- Then growing the new organism

How Are GMOs Made? Fact Sheet

Making a GMO Plant, Step by Step

The following example gives a general idea of the steps it takes to create a GMO plant. This example uses a type of insect-resistant corn called “Bt corn.” Keep in mind that the processes for creating a GMO plant, animal, or microorganism may be different.

To produce a GMO plant, scientists first identify what trait they want that plant to have, such as resistance to drought, herbicides, or insects. Then, they find an organism (plant, animal, or microorganism) that already has that trait within its genes. In this example, scientists wanted to create insect-resistant corn to reduce the need to spray pesticides. They identified a gene in a soil bacterium called Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) , which produces a natural insecticide that has been in use for many years in traditional and organic agriculture.

After scientists find the gene with the desired trait, they copy that gene.

For Bt corn, they copied the gene in Bt that would provide the insect-resistance trait.

Next, scientists use tools to insert the gene into the DNA of the plant. By inserting the Bt gene into the DNA of the corn plant, scientists gave it the insect resistance trait.

This new trait does not change the other existing traits.

In the laboratory, scientists grow the new corn plant to ensure it has adopted the desired trait (insect resistance). If successful, scientists first grow and monitor the new corn plant (now called Bt corn because it contains a gene from Bacillus thuringiensis) in greenhouses and then in small field tests before moving it into larger field tests. GMO plants go through in-depth review and tests before they are ready to be sold to farmers.

The entire process of bringing a GMO plant to the marketplace takes several years.

Learn more about the process for creating genetically engineered microbes and genetically engineered animals .

What are the latest scientific advances in plant and animal breeding?

Scientists are developing new ways to create new varieties of crops and animals using a process called genome editing . These techniques can make changes more quickly and precisely than traditional breeding methods.

There are several genome editing tools, such as CRISPR . Scientists can use these newer genome editing tools to make crops more nutritious, drought tolerant, and resistant to insect pests and diseases.

Learn more about Genome Editing in Agricultural Biotechnology .

How GMOs Are Regulated in the United States

GMO Crops, Animal Food, and Beyond

How GMO Crops Impact Our World

www.fda.gov/feedyourmind

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Father’s Day 2024

By: History.com Editors

Updated: January 31, 2024 | Original: December 30, 2009

The nation’s first Father’s Day was celebrated on June 19, 1910, in the state of Washington. However, it was not until 1972—58 years after President Woodrow Wilson made Mother’s Day official—that the day honoring fathers became a nationwide holiday in the United States. Father’s Day 2024 will occur on Sunday, June 16.

Mother’s Day: Inspiration for Father’s Day

The “ Mother’s Day ” we celebrate today has its origins in the peace-and-reconciliation campaigns of the post- Civil War era. During the 1860s, at the urging of activist Ann Reeves Jarvis, one divided West Virginia town celebrated “Mother’s Work Days” that brought together the mothers of Confederate and Union soldiers.

Did you know? There are more than 70 million fathers in the United States.

However, Mother’s Day did not become a commercial holiday until 1908, when–inspired by Jarvis’s daughter, Anna Jarvis , who wanted to honor her own mother by making Mother’s Day a national holiday–the John Wanamaker department store in Philadelphia sponsored a service dedicated to mothers in its auditorium.

Thanks in large part to this association with retailers, who saw great potential for profit in the holiday, Mother’s Day caught on right away. In 1909, 45 states observed the day, and in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson approved a resolution that made the second Sunday in May a holiday in honor of “that tender, gentle army, the mothers of America.”

Origins of Father’s Day

The campaign to celebrate the nation’s fathers did not meet with the same enthusiasm–perhaps because, as one florist explained, “fathers haven’t the same sentimental appeal that mothers have.”

On July 5, 1908, a West Virginia church sponsored the nation’s first event explicitly in honor of fathers, a Sunday sermon in memory of the 362 men who had died in the previous December’s explosions at the Fairmont Coal Company mines in Monongah, but it was a one-time commemoration and not an annual holiday.

The next year, a Spokane, Washington , woman named Sonora Smart Dodd, one of six children raised by a widower, tried to establish an official equivalent to Mother’s Day for male parents. She went to local churches, the YMCA, shopkeepers and government officials to drum up support for her idea, and she was successful: Washington State celebrated the nation’s first statewide Father’s Day on June 19, 1910.

Slowly, the holiday spread. In 1916, President Wilson honored the day by using telegraph signals to unfurl a flag in Spokane when he pressed a button in Washington, D.C. In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge urged state governments to observe Father’s Day.

Today, the day honoring fathers is celebrated in the United States on the third Sunday of June: Father’s Day 2021 occurs on June 20.

In other countries–especially in Europe and Latin America–fathers are honored on St. Joseph’s Day, a traditional Catholic holiday that falls on March 19.

Father’s Day: Controversy and Commercialism