Case Examples

Examples of recommended interventions in the treatment of depression across the lifespan.

Children/Adolescents

A 15-year-old Puerto Rican female

The adolescent was previously diagnosed with major depressive disorder and treated intermittently with supportive psychotherapy and antidepressants. Her more recent episodes related to her parents’ marital problems and her academic/social difficulties at school. She was treated using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Chafey, M.I.J., Bernal, G., & Rossello, J. (2009). Clinical Case Study: CBT for Depression in A Puerto Rican Adolescent. Challenges and Variability in Treatment Response. Depression and Anxiety , 26, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20457

Sam, a 15-year-old adolescent

Sam was team captain of his soccer team, but an unexpected fight with another teammate prompted his parents to meet with a clinical psychologist. Sam was diagnosed with major depressive disorder after showing an increase in symptoms over the previous three months. Several recent challenges in his family and romantic life led the therapist to recommend interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents (IPT-A).

Hall, E.B., & Mufson, L. (2009). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Depressed Adolescents (IPT-A): A Case Illustration. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 38 (4), 582-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410902976338

© Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA, https://sccap53.org/, reprinted by permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com on behalf of the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (Div. 53) APA.

General Adults

Mark, a 43-year-old male

Mark had a history of depression and sought treatment after his second marriage ended. His depression was characterized as being “controlled by a pattern of interpersonal avoidance.” The behavior/activation therapist asked Mark to complete an activity record to help steer the treatment sessions.

Dimidjian, S., Martell, C.R., Addis, M.E., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2008). Chapter 8: Behavioral activation for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 343-362). New York: Guilford Press.

Reprinted with permission from Guilford Press.

Denise, a 59-year-old widow

Denise is described as having “nonchronic depression” which appeared most recently at the onset of her husband’s diagnosis with brain cancer. Her symptoms were loneliness, difficulty coping with daily life, and sadness. Treatment included filling out a weekly activity log and identifying/reconstructing automatic thoughts.

Young, J.E., Rygh, J.L., Weinberger, A.D., & Beck, A.T. (2008). Chapter 6: Cognitive therapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 278-287). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Nancy, a 25-year-old single, white female

Nancy described herself as being “trapped by her relationships.” Her intake interview confirmed symptoms of major depressive disorder and the clinician recommended cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Persons, J.B., Davidson, J. & Tompkins, M.A. (2001). A Case Example: Nancy. In Essential Components of Cognitive-Behavior Therapy For Depression (pp. 205-242). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10389-007

While APA owns the rights to this text, some exhibits are property of the San Francisco Bay Area Center for Cognitive Therapy, which has granted the APA permission for use.

Luke, a 34-year-old male graduate student

Luke is described as having treatment-resistant depression and while not suicidal, hoped that a fatal illness would take his life or that he would just disappear. His treatment involved mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, which helps participants become aware of and recharacterize their overwhelming negative thoughts. It involves regular practice of mindfulness techniques and exercises as one component of therapy.

Sipe, W.E.B., & Eisendrath, S.J. (2014). Chapter 3 — Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy For Treatment-Resistant Depression. In R.A. Baer (Ed.), Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches (2nd ed., pp. 66-70). San Diego: Academic Press.

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Sara, a 35-year-old married female

Sara was referred to treatment after having a stillbirth. Sara showed symptoms of grief, or complicated bereavement, and was diagnosed with major depression, recurrent. The clinician recommended interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for a duration of 12 weeks.

Bleiberg, K.L., & Markowitz, J.C. (2008). Chapter 7: Interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. In D.H. Barlow (Ed.) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a treatment manual (4th ed., pp. 315-323). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Peggy, a 52-year-old white, Italian-American widow

Peggy had a history of chronic depression, which flared during her husband’s illness and ultimate death. Guilt was a driving factor of her depressive symptoms, which lasted six months after his death. The clinician treated Peggy with psychodynamic therapy over a period of two years.

Bishop, J., & Lane , R.C. (2003). Psychodynamic Treatment of a Case of Grief Superimposed On Melancholia. Clinical Case Studies , 2(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650102239085

Several case examples of supportive therapy

Winston, A., Rosenthal, R.N., & Pinsker, H. (2004). Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy . Arlington, VA : American Psychiatric Publishing.

Older Adults

Several case examples of interpersonal psychotherapy & pharmacotherapy

Miller, M. D., Wolfson, L., Frank, E., Cornes, C., Silberman, R., Ehrenpreis, L.…Reynolds, C. F., III. (1998). Using Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) in a Combined Psychotherapy/Medication Research Protocol with Depressed Elders: A Descriptive Report With Case Vignettes. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research , 7(1), 47-55.

Social Work Practice with Carers

Case Study 2: Josef

Download the whole case study as a PDF file

Josef is 16 and lives with his mother, Dorota, who was diagnosed with Bipolar disorder seven years ago. Josef was born in England. His parents are Polish and his father sees him infrequently.

This case study looks at the impact of caring for someone with a mental health problem and of being a young carer , in particular the impact on education and future employment .

When you have looked at the materials for the case study and considered these topics, you can use the critical reflection tool and the action planning tool to consider your own practice.

- One-page profile

Support plan

Transcript (.pdf, 48KB)

Name : Josef Mazur

Gender : Male

Ethnicity : White European

Download resource as a PDF file

First language : English/ Polish

Religion : Roman Catholic

Josef lives in a small town with his mother Dorota who is 39. Dorota was diagnosed with Bi-polar disorder seven years ago after she was admitted to hospital. She is currently unable to work. Josef’s father, Stefan, lives in the same town and he sees him every few weeks. Josef was born in England. His parents are Polish and he speaks Polish at home.

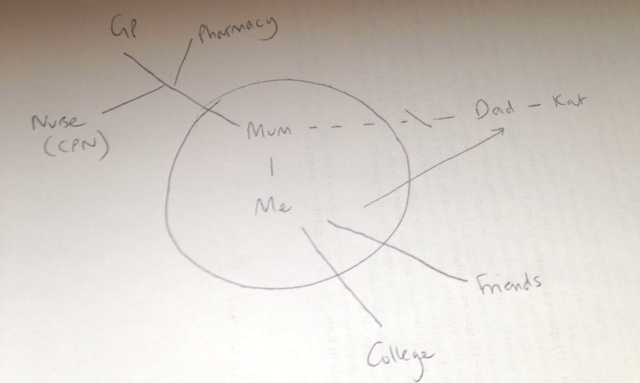

Josef is doing a foundation art course at college. Dorota is quite isolated because she often finds it difficult to leave the house. Dorota takes medication and had regular visits from the Community Psychiatric Nurse when she was diagnosed and support from the Community Mental Health team to sort out her finances. Josef does the shopping and collects prescriptions. He also helps with letters and forms because Dorota doesn’t understand all the English. Dorota gets worried when Josef is out. When Dorota is feeling depressed, Josef stays at home with her. When Dorota is heading for a high, she tries to take Josef to do ‘exciting stuff’ as she calls it. She also spends a lot of money and is very restless.

Josef worries about his mother’s moods. He is worried about her not being happy and concerned at the money she spends when she is in a high mood state. Josef struggles to manage his day around his mother’s demands and to sleep when she is high. Josef has not told anyone about the support he gives to his mother. He is embarrassed by some of the things she does and is teased by his friends, and he does not think of himself as a carer. Josef has recently had trouble keeping up with course work and attendance. He has been invited to a meeting with his tutor to formally review attendance and is worried he will get kicked out. Josef has some friends but he doesn’t have anyone he can confide in. His father doesn’t speak to his mother.

Josef sees some information on line about having a parent with a mental health problem. He sends a contact form to ask for information. Someone rings him and he agrees to come into the young carers’ team and talk to the social worker. You have completed the assessment form with Josef in his words and then done a support plan with him.

Back to Summary

Josef Mazur

What others like and admire about me

Good at football

Finished Arkham Asylum on expert level

What is important to me

Mum being well and happy

Seeing my dad

Being an artist

Seeing my friends

How best to support me

Tell me how to help mum better

Don’t talk down to me

Talk to me 1 to 1

Let me know who to contact if I am worried about something

Work out how I can have some time on my own so I can do my college work and see my friends

Don’t tell mum and my friends

Date chronology completed : 7 March 2016

Date chronology shared with person: 7 March 2016

| 1997 | Josef’s mother and father moved to England from Poznan. | Both worked at the warehouse – Father still works there. |

| 11.11.1999 | Josef born. | Mother worked for some of the time that Josef was young. |

| 2006 | Josef reports that his mother and father started arguing about this time because of money and Josef’s mother not looking after household tasks. | Josef started doing household tasks e.g. cleaning, washing and ironing. |

| 2008 | Josef reports that his mother didn’t get out of bed for a few months. | Josef managed the household during this period. |

| October 2008 | Josef reports that his mother spent lots of money in catalogues and didn’t sleep. She was admitted to hospital. | Mother was in hospital for 6 weeks and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Josef began looking after his mother’s medication and says that he started to ‘keep an eye on her.’ |

| May 2010 | Josef’s father moved out to live with his friend Kat. Josef stayed with his mother. | Josef reports that his mother was ‘really sad for a while and then she went round and shouted at them.’ Mother started on different medication and had regular visits from the Community Psychiatric Nurse. Josef said that the CPN told him about his mum’s illness and to let him know if he needed any help but he was managing ok. Josef saw his father every week for a few years and then it was more like every month. Father does not visit Josef or speak to his mother. |

| 2013/14 | Josef reports that his mother got into a lot of debt and they had eviction letters. | Josef’s father paid some of the bills and his mother was referred by the Community Mental Health Team for advice from CAB and started getting benefits. Josef started doing the correspondence. |

| 2015 | Josef left school and went to college. | Josef got an A (art), 4 Cs and 3 Ds GCSE. He says that he ‘would have done better but I didn’t do much work.’ |

| 26 Feb 2016 | Josef got a letter from his tutor at college saying he had to go to a formal review about attendance. | Josef saw information on-line about having a parent with a mental health problem and asked for some information. |

| 2 March 2016 | Phone call from young carer’s team to Josef. | Josef agreed to come in for an assessment. |

| 4 March 2016 | Social worker meets with Josef. | Carer’s assessment and support plan completed. |

| 7 March 2016 | Paperwork completed. | Sent to Josef. |

Young Carers Assessment

Do you look after or care for someone at home?

The questions in this paper are designed to help you think about your caring role and what support you might need to make your life a little easier or help you make time for more fun stuff.

Please feel free to make notes, draw pictures or use the form however is best for you.

What will happen to this booklet?

This is your booklet and it is your way to tell an adult who you trust about your caring at home. This will help you and the adult find ways to make your life and your caring role easier.

The adult who works with you on your booklet might be able to help you with everything you need. If they can’t, they might know other people who can.

Our Agreement

- I will share this booklet with people if I think they can help you or your family

- I will let you know who I share this with, unless I am worried about your safety, about crime or cannot contact you

- Only I or someone from my team will share this booklet

- I will make sure this booklet is stored securely

- Some details from this booklet might be used for monitoring purposes, which is how we check that we are working with everyone we should be

Signed: ___________________________________

Young person:

- I know that this booklet might get shared with other people who can help me and my family so that I don’t have to explain it all over again

- I understand what my worker will do with this booklet and the information in it (written above).

Signed: ____________________________________

Name : Josef Mazur Address : 1 Green Avenue, Churchville, ZZ1 Z11 Telephone: 012345 123456 Email: [email protected] Gender : Male Date of birth : 11.11.1999 Age: 16 School : Green College, Churchville Ethnicity : White European First language : English/ Polish Religion : Baptised Roman Catholic GP : Dr Amp, Hill Surgery

The best way to get in touch with me is:

Do you need any support with communication?

*Josef is bilingual – English and Polish. He speaks English at school and with his friends, and Polish at home. Josef was happy to have this assessment in English, however, another time he may want to have a Polish interpreter. It will be important to ensure that Josef is able to use the words he feels best express himself.

About the person/ people I care for

I look after my mum who has bipolar disorder. Mum doesn’t work and doesn’t really leave the house unless she is heading for a high. When Mum is sad she just stays at home. When she is getting hyper then she wants to do exciting stuff and she spends lots of money and she doesn’t sleep.

Do you wish you knew more about their illness?

Do you live with the person you care for?

What I do as a carer It depends on if my mum has a bad day or not. When she is depressed she likes me to stay home with her and when she is getting hyper then she wants me to go out with her. If she has new meds then I like to be around. Mum doesn’t understand English very well (she is from Poland) so I do all the letters. I help out at home and help her with getting her medication.

Tell us what an average week is like for you, what kind of things do you usually do?

Monday to Friday

Get up, get breakfast, make sure mum has her pills, tell her to get up and remind her if she’s got something to do.

If mum hasn’t been to bed then encourage her to sleep a bit and set an alarm

College – keep phone on in case mum needs to call – she usually does to ask me to get something or check when I’m coming home

Go home – go to shops on the way

Remind mum about tablets, make tea and pudding for both of us as well as cleaning the house and fitting tea in-between, ironing, hoovering, hanging out and bringing in washing

Do college work when mum goes to bed if not too tired

More chores

Do proper shop

Get prescription

See my friends, do college work

Sunday – do paper round

Physical things I do….

(for example cooking, cleaning, medication, shopping, dressing, lifting, carrying, caring in the night, making doctors appointments, bathing, paying bills, caring for brothers & sisters)

I do all the housework and shopping and cooking and get medication

Things I find difficult

Emotional support I provide…. (please tell us about the things you do to support the person you care for with their feelings; this might include, reassuring them, stopping them from getting angry, looking after them if they have been drinking alcohol or taking drugs, keeping an eye on them, helping them to relax)

If mum is stressed I stay with her

If mum is depressed I have to keep things calm and try to lighten the mood

She likes me to be around

When mum is heading for a high wants to go to theme parks or book holidays and we can’t afford it

I worry that mum might end up in hospital again

Mum gets cross if I go out

Other support

Please tell us about any other support the person you care for already has in place like a doctor or nurse, or other family or friends.

The GP sees mum sometimes. She has a nurse who she can call if things get bad.

Mum’s medication comes from Morrison’s pharmacy.

Dad lives nearby but he doesn’t talk to mum.

Mum doesn’t really have any friends.

Do you ever have to stop the person you care for from trying to harm themselves or others?

Some things I need help with

Sorting out bills and having more time for myself

I would like mum to have more support and to have some friends and things to do

On a normal week, what are the best bits? What do you enjoy the most? (eg, seeing friends, playing sports, your favourite lessons at school)

Seeing friends

When mum is up and smiling

Playing football

On a normal week, what are the worst bits? What do you enjoy the least? (eg cleaning up, particular lessons at school, things you find boring or upsetting)

Nagging mum to get up

Reading letters

Missing class

Mum shouting

Friends laugh because I have to go home but they don’t have to do anything

What things do you like to do in your spare time?

Do you feel you have enough time to spend with your friends or family doing things you enjoy, most weeks?

Do you have enough time for yourself to do the things you enjoy, most weeks? (for example, spending time with friends, hobbies, sports)

Are there things that you would like to do, but can’t because of your role as a carer?

Can you say what some of these things are?

See friends after college

Go out at the weekend

Time to myself at home

It can feel a bit lonely

I’d like my mum to be like a normal mum

School/ College Do you think being your caring role makes school/college more difficult for you in any way?

If you ticked YES, please tell us what things are made difficult and what things might help you.

Things I find difficult at school/ college

Sometimes I get stressed about college and end up doing college work really late at night – I get a bit angry when I’m stressed

I don’t get all my college work done and I miss days

I am tired a lot of the time

Things I need help with…

I am really worried they will kick me out because I am behind and I miss class. I have to meet my tutor about it.

Do your teachers know about your caring role?

Are you happy for your teachers and other staff at school/college to know about your caring role?

Do you think that being a carer will make it more difficult for you to find or keep a job?

Why do you think being a carer is/ will make finding a job more difficult?

I haven’t thought about it. I don’t know if I’ll be able to finish my course and do art and then I won’t be able to be an artist.

Who will look after mum?

What would make it easier for you to find a job after school/college?

Finishing my course

Mum being ok

How I feel about life…

Do you feel confident both in school and outside of school?

Somewhere in the middle

In your life in general, how happy do you feel?

Quite unhappy

In your life in general, how safe do you feel?

How healthy do you feel at the moment?

Quite healthy

Being heard

Do you think people listen to what you are saying and how you are feeling?

If you said no, can you tell us who you feel isn’t listening or understanding you sometimes (eg, you parents, your teachers, your friends, professionals)

I haven’t told anyone

I can’t talk to mum

My friends laugh at me because I don’t go out

Do you think you are included in important decisions about you and your life? (eg, where you live, where you go to school etc)

Do you think that you’re free to make your own choices about what you do and who you spend your time with?

Not often enough

Is there anybody who knows about the caring you’re doing at the moment?

If so, who?

I told dad but he can’t do anything

Would you like someone to talk to?

Supporting me Some things that would make my life easier, help me with my caring or make me feel better

I don’t know

Fix mum’s brain

People to help me if I’m worried and they can do something about it

Not getting kicked out of college

Free time – time on my own to calm down and do work or have time to myself

Time to go out with my friends

Get some friends for mum

I don’t want my mum to get into trouble

Who can I turn to for advice or support?

I would like to be able to talk to someone without mum or friends knowing

Would you like a break from your caring role?

How easy is it to see a Doctor if you need to?

To be used by social care assessors to consider and record measures which can be taken to assist the carer with their caring role to reduce the significant impact of any needs. This should include networks of support, community services and the persons own strengths. To be eligible the carer must have significant difficulty achieving 1 or more outcomes without support; it is the assessors’ professional judgement that unless this need is met there will be a significant impact on the carer’s wellbeing. Social care funding will only be made available to meet eligible outcomes that cannot be met in any other way, i.e. social care funding is only available to meet unmet eligible needs.

Date assessment completed : 7 March 2016

Social care assessor conclusion

Josef provides daily support to his mum, Dorota, who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder seven years ago. Josef helps Dorota with managing correspondence, medication and all household tasks including shopping. When Dorota has a low mood, Josef provides support and encouragement to get up. When Dorota has a high mood, Josef helps to calm her and prevent her spending lots of money. Josef reports that Dorota has some input from community health services but there is no other support. Josef’s dad is not involved though Josef sees him sometimes, and there are no friends who can support Dorota.

Josef is a great support to his mum and is a loving son. He wants to make sure his mum is ok. However, caring for his mum is impacting: on Josef’s health because he is tired and stressed; on his emotional wellbeing as he can get angry and anxious; on his relationship with his mother and his friends; and on his education. Josef is at risk of leaving college. Josef wants to be able to support his mum better. He also needs time for himself, to develop and to relax, and to plan his future.

Eligibility decision : Eligible for support

What’s happening next : Create support plan

Completed by Name : Role : Organisation :

Name: Josef Mazur

Address 1 Green Avenue, Churchville, ZZ1 Z11

Telephone 012345 123456

Email [email protected]

Gender: Male

Date of birth: 11.11.1999 Age: 16

School Green College, Churchville

Ethnicity White European

First language English/ Polish

Religion Baptised Roman Catholic

GP Dr Amp, Hill Surgery

My relationship to this person son

Name Dorota Mazur

Gender Female

Date of birth 12.6.79 Age 36

First language Polish

Religion Roman Catholic

Support plan completed by

Organisation

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| ||

|

| ||

Date of support plan: 7 March 2016

This plan will be reviewed on: 7 September 2016

Signing this form

Please ensure you read the statement below in bold, then sign and date the form.

I understand that completing this form will lead to a computer record being made which will be treated confidentially. The council will hold this information for the purpose of providing information, advice and support to meet my needs. To be able to do this the information may be shared with relevant NHS Agencies and providers of carers’ services. This will also help reduce the number of times I am asked for the same information.

If I have given details about someone else, I will make sure that they know about this.

I understand that the information I provide on this form will only be shared as allowed by the Data Protection Act.

Josef has given consent to share this support plan with the CPN but does not want it to be shared with his mum.

Mental health

The social work role with carers in adult mental health services has been described as: intervening and showing professional leadership and skill in situations characterised by high levels of social, family and interpersonal complexity, risk and ambiguity (Allen 2014). Social work with carers of people with mental health needs, is dependent on good practice with the Mental Capacity Act where practitioner knowledge and understanding has been found to be variable (Iliffe et al 2015).

- Carers Trust (2015) Mental Health Act 1983 – Revised Code of Practice Briefing

- Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

- Mind, Talking about mental health

- Tool 1: Triangle of care: self-assessment for mental health professionals – Carers Trust (2013) The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England Second Edition (page 23 Self-assessment tool for organisations)

Mental capacity, confidentiality and consent

Social work with carers of people with mental health needs, is dependent on good practice with the Mental Capacity Act where practitioner knowledge and understanding has been found to be variable (Iliffe et al 2015). Research highlights important issues about involvement, consent and confidentiality in working with carers (RiPfA 2016, SCIE 2015, Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland 2013).

- Beddow, A., Cooper, M., Morriss, L., (2015) A CPD curriculum guide for social workers on the application of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 . Department of Health

- Bogg, D. and Chamberlain, S. (2015) Mental Capacity Act 2005 in Practice Learning Materials for Adult Social Workers . Department of Health

- Department of Health (2015) Best Interest Assessor Capabilities , The College of Social Work

- RiPfA Good Decision Making Practitioner Handbook

- SCIE Mental Capacity Act resource

- Tool 2: Making good decisions, capacity tool (page 70-71 in good decision making handbook)

Young carers

A young carer is defined as a person under 18 who provides or intends to provide care for another person. The concept of care includes practical or emotional support. It is the case that this definition excludes children providing care as part of contracted work or as voluntary work. However, the local authority can ignore this and carry out a young carer’s need assessment if they think it would be appropriate. Young carers, young adult carers and their families now have stronger rights to be identified, offered information, receive an assessment and be supported using a whole-family approach (Carers Trust 2015).

- SCIE (2015) Young carer transition in practice under the Care Act 2014

- SCIE (2015) Care Act: Transition from children’s to adult services – early and comprehensive identification

- Carers Trust (2015) Rights for young carers and young adult carers in the Children and Families Act

- Carers Trust (2015) Know your Rights: Support for Young Carers and Young Adult Carers in England

- The Children’s Society (2015) Hidden from view: The experiences of young carers in England

- DfE (2011) Improving support for young carers – family focused approaches

- ADASS and ADCS (2015) No wrong doors: working together to support young carers and their families

- Carers Trust, Supporting Young Carers and their Families: Examples of Practice

- Refugee toolkit webpage: Children and informal interpreting

- SCIE (2010) Supporting carers: the cared for person

- SCIE (2015) Care Act Transition from children’s to adults’ services – Video diaries

- Tool 3: Young carers’ rights – The Children’s Society (2014) The Know Your Rights pack for young carers in England!

- Tool 4: Vision and principles for adults’ and children’s services to work together

Young carers of parents with mental health problems

The Care Act places a duty on local authorities to assess young carers before they turn 18, so that they have the information they need to plan for their future. This is referred to as a transition assessment. Guidance, advocating a whole family approach, is available to social workers (LGA 2015, SCIE 2015, ADASS/ADCS 2011).

- SCIE (2012) At a glance 55: Think child, think parent, think family: Putting it into practice

- SCIE (2008) Research briefing 24: Experiences of children and young people caring for a parent with a mental health problem

- SCIE (2008) SCIE Research briefing 29: Black and minority ethnic parents with mental health problems and their children

- Carers Trust (2015) The Triangle of Care for Young Carers and Young Adult Carers: A Guide for Mental Health Professionals

- ADASS and ADCS (2011) Working together to improve outcomes for young carers in families affected by enduring parental mental illness or substance misuse

- Ofsted (2013) What about the children? Joint working between adult and children’s services when parents or carers have mental ill health and/or drug and alcohol problems

- Mental health foundation (2010) MyCare The challenges facing young carers of parents with a severe mental illness

- Children’s Commissioner (2012) Silent voices: supporting children and young people affected by parental alcohol misuse

- SCIE, Parental mental health and child welfare – a young person’s story

Tool 5: Family model for assessment

- Tool 6: Engaging young carers of parents with mental health problems or substance misuse

Young carers and education/ employment

Transition moments are highlighted in the research across the life course (Blythe 2010, Grant et al 2010). Complex transitions required smooth transfers, adequate support and dedicated professionals (Petch 2010). Understanding transition theory remains essential in social work practice (Crawford and Walker 2010). Partnership building expertise used by practitioners was seen as particular pertinent to transition for a young carer (Heyman 2013).

- TLAP (2013) Making it real for young carers

- Learning and Work Institute (2018) Barriers to employment for young adult carers

- Carers Trust (2014) Young Adult Carers at College and University

- Carers Trust (2013) Young Adult Carers at School: Experiences and Perceptions of Caring and Education

- Carers Trust (2014) Young Adult Carers and Employment

- Family Action (2012) BE BOTHERED! Making Education Count for Young Carers

Download The Triangle of Care as a PDF file

The Triangle of Care Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England

The Triangle of Care is a therapeutic alliance between service user, staff member and carer that promotes safety, supports recovery and sustains wellbeing…

Download the Capacity Tool as a PDF file

Capacity Tool Good decision-making Practitioners’ Handbook

The Capacity tool on page 71 has been developed to take into account the lessons from research and the case CC v KK. In particular:

- that capacity assessors often do not clearly present the available options (especially those they find undesirable) to the person being assessed

- that capacity assessors often do not explore and enable a person’s own understanding and perception of the risks and advantages of different options

- that capacity assessors often do not reflect upon the extent to which their ‘protection imperative’ has influenced an assessment, which may lead them to conclude that a person’s tolerance of risks is evidence of incapacity.

The tool allows you to follow steps to ensure you support people as far as possible to make their own decisions and that you record what you have done.

Download Know your rights as a PDF file

Tool 3: Know Your Rights Young Carers in Focus

This pack aims to make you aware of your rights – your human rights, your legal rights, and your rights to access things like benefits, support and advice.

Need to know where to find things out in a hurry? Our pack has lots of links to useful and interesting resources that can help you – and help raise awareness about young carers’ issues!

Know Your Rights has been produced by Young Carers in Focus (YCiF), and funded by the Big Lottery Fund.

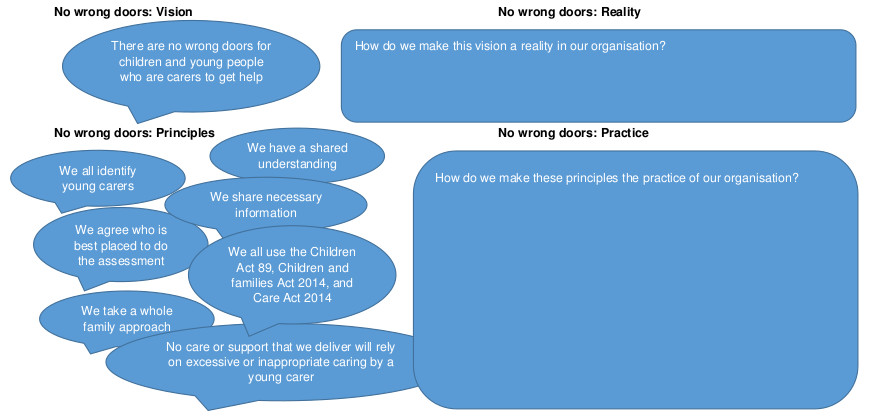

Tool 4: Vision and principles for adults’ and children’s services to work together to support young carers

Download the tool as a PDF file

You can use this tool to consider how well adults’ and children’s services work together, and how to improve this.

Click on the diagram to open full size in a new window

This is based on ADASS and ADCS (2015) No wrong doors : working together to support young carers and their families

Download the tool as a PDF file

You can use this tool to help you consider the whole family in an assessment or review.

What are the risk, stressors and vulnerability factors?

How is the child/ young person’s wellbeing affected?

How is the adult’s wellbeing affected?

What are the protective factors and available resources?

This tool is based on SCIE (2009) Think child, think parent, think family: a guide to parental mental health and child welfare

Tool 6: Engaging young carers

Young carers have told us these ten things are important. So we will do them.

- Introduce yourself. Tell us who you are and what your job is.

- Give us as much information as you can.

- Tell us what is wrong with our parents.

- Tell us what is going to happen next.

- Talk to us and listen to us. Remember it is not hard to speak to us we are not aliens.

- Ask us what we know and what we think. We live with our parents; we know how they have been behaving.

- Tell us it is not our fault. We can feel guilty if our mum or dad is ill. We need to know we are not to blame.

- Please don’t ignore us. Remember we are part of the family and we live there too.

- Keep on talking to us and keeping us informed. We need to know what is happening.

- Tell us if there is anyone we can talk to. Maybe it could be you.

- Equal opportunities

- Complaints procedure

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Social work practice in community mental health

During the past twenty years, the mental health field has become increasingly cognizant of the interaction between social life and mental status—a relationship that is the basis of traditional social work practice. Social work is committed to improving the interaction among individuals, among institutions, and between people and institutions to enhance the general quality of life. However, in mental health, the major concern (the “dependent variable” in research jargon) is mental status. This article is concerned with social work’s role in community mental health: the activities that enable the social worker to contribute to the improvement of an individual’s mental status while maintaining a commitment to viewing the person in the environment and to improving the overall quality of social life.

As a profession, social work is concerned with all spheres of interaction between people and their environments. Social workers practice in the realm of formal organizations of care and control; are concerned with the social, psychological, and jural dimensions of the family; and have become increasingly interested in the everyday support systems that function among friends and acquaintances. All these concerns have been identified, in one way or another, with the treatment of mental disorders or the promotion of mental health.

To the consternation of many traditional mental health professionals, the field of community mental health has become so elastic that it now includes almost all kinds of ameliorative activity. This expanded purview derives from the association of a myriad of social factors with the development of mental disorders and from the concomitant tendency to equate social well-being with mental well-being. For instance, the relationship between social class and mental illness and the relationship between social stress and mental illness clearly indicate that poor people are at the greatest risk of developing mental disorders.

Because of these relationships, it is tempting to conclude that full employment, better housing for the poor, national health insurance, and an array of poverty programs might be the best means to reduce mental disorders in a society. Unfortunately, there is little evidence to support this conclusion. Such policies and programs are laudable in their own right, but their impact on the mental status of the individual is subject to question. 1 The equation of social well-being and mental well-being is like the Calvinist equation of wealth with salvation: both are nice, but not necessarily related.

What does it mean, then, to “contribute to the improvement of individual mental status” while “maintaining a commitment to improving the overall quality of social life”? The answer depends largely on how a mental health “problem” and a mental health “service” are construed.

INAPPROPRIATE LABELS

As one moves farther from the traditional concerns of mental health (with psychoses, for example), the reliability of the assessment of mental status becomes poorer and the risk of inappropriately labeling “problems of living” as “mental disorders” becomes greater. Similarly, when one approaches human problems whose relationship to discernible mental disorders is ambiguous or distant, the definition of a “mental health service” becomes problematic.

Current empirical understanding does not permit a more elegant solution in either case. Mental disorders are variously defined and diagnosed either in narrow or broad terms. And a mental health service is often what Congress, the National Institute of Mental Health, state legislatures, or local citizens’ advisory boards are willing to pay for.

The clinical risks associated with inappropriate labels make it incumbent on mental health practitioners to be specific and judicious in the use of labels. Further, the treatment of individuals in mental health settings, as opposed to social service or “generic” settings, may discourage potential clients who “know” that only “crazy people” (or members of any devalued group for that matter) go there for help. For this reason, it is often necessary for mental health agencies to assume names that disguise their purpose or spoof the severity of their clients’ problems. (In the past, the authors have been aware of such examples as the Daily Planet in Richmond, Virginia, and the Cabin Fever Clinic in Anchorage, Alaska.) Similarly, in many cases practitioners must allow clients to treat a meaningful diagnosis as a euphemism for problems of living. This obviates the often needless semantic battles over the clinician’s specific meaning and right to pass judgment. Admittedly, these are expedient methods of relieving the dilemma of its horns, but they appear unavoidable in many circumstances and are therefore widely practiced.

Following the same logic of expediency, the authors regard a “mental health service” as whatever service is necessary to improve what clients (except those who are a danger to themselves or others) regard as a less-than-desirable mental status, regardless of the diagnostic description. Although this definition permits a broad interpretation, priorities pertaining to the more reliably assessed mental health problems and to the expenditure of limited funds justifiably narrow the field. That is, mental health services must pay more attention to problems which are derivative of chronic schizophrenia than to those that are only marginally related to mental status.

The following is an example of how broadly the term “mental health service” can be interpreted:

The executive director of a community mental health center (a psychiatrist) was annoyed with the director of the children’s service (a social worker) because she had allowed her staff to provide day care to children of single working mothers whom she believed to be an at-risk population. The executive director informed the children’s service director that no further funds could be expended on this program because it was not a mental health service. She replied that a day care service for children of single mothers who were under stress was a mental health service. Authority prevailed, but the issue was never resolved.

Therefore, the day care service ceased to be a mental health service; it became an “educational supplement.” However, emergency housing was considered an important contribution to mental health and thus became a mental health service. These distinctions came about because the local school district had funds for day care, whereas the mental health system had money for emergency shelter. Subsequently, when the mental health system had fewer funds, shelter became a “social service” and received support from elsewhere.

These are the political concerns that govern the organization and subsidy of mental health care. Such distinctions are authoritative and they are usually arbitrary. Fortunately, the activities of social work transcend their settings. The profession is bigger than the organization of care. The social worker in community mental health is not only concerned with duly sanctioned mental health services but is committed to the application of whatever services can reasonably be expected to improve the mental status of a client over time or to prevent the predictable deterioration of mental status. In the broadest and most important sense, this is what differentiates casework from psychotherapy. If a single mother needs day care for her children to alleviate her anxiety, the case plan should include such services—within the mental health system if they are provided there or within the school system if that is where they are to be found.

Traditional mental health settings are not the only ones that provide mental health services. Family service agencies, youth service bureaus, and many other general social service agencies provide services that are legitimately within the realm of mental health. Many of these agencies provide better services than the traditional agencies. However, in this article, the authors have chosen to focus on the activities of the traditional agencies because these agencies have brought mental health services to the general population, especially to those with discernible mental disorders.

In the past twenty years, two practice models have developed as a result of the community care and community mental health movements. The community care movement has spawned a practice model based primarily on legal and administrative mandates designed to minimize the violation of the patient’s civil rights and to maximize the patient’s right to “fail.” The community mental health movement is based on the epidemiological model. The remainder of this article will be devoted to a discussion of the two models (including their history and problems and the role of the social worker) and to the relationship between the objectives of social work and the practice of community mental health.

COMMUNITY CARE

According to the U.S. General Accounting Office, community care seeks to

(1) Prevent both unnecessary admission to and retention in institutions; (2) Find and develop appropriate alternatives in the community for housing, treatment, training, education, and rehabilitation of the mentally disabled who do not need to be in institutions; (3) Improve conditions, care, and treatment for those who need institutional care …; [(4) Entitle] mentally disabled persons to live in the least restrictive environment necessary and to lead their lives as normally and independently as they can. 2

These principles have been given teeth by administrative codes, state and federal law, and judicial decisions that have formed what amounts to a judicial and statutory model for practice. The U.S. General Accounting Office goes on to say:

Judicially imposed standards in New York and Alabama provide that those states shall make every attempt to move residents of the designated institutions from (1) more to less structured living; (2) larger to smaller facilities; (3) larger to smaller living units: (4) group to individual residences; (5) places segregated from the community to places integrated with community living and programming; (6) dependent to independent living. 3

The Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, passed in California in 1969, is tantamount to a patient’s bill of rights. The act guarantees patients in California the right to a judicial hearing with respect to involuntary confinement and imposes hard evidentiary standards for involuntary admissions. The act also allows patients to refuse certain types of treatment, such as shock treatment and lobotomy. An October 1979 decision in Boston (Rogers et al . v. Okin , U.S. Court, District of Massachusetts, 75–1610–T) allows patients to refuse antipsychotic medication and seclusion unless they are dangerous to themselves or others. Furthermore, the 1972 Wyatt v. Stickney decision in Alabama confirmed that involuntary patients have a right to treatment, not merely custodial care. And there have been other efforts to extend the right-to-treatment principle to community care. 4

Traditionally, social workers have been responsible for managing the patient’s transition from hospital to community. In California, from 1946 until the early 1970s, social workers in the Bureau of Social Work had primary responsibility for community placement and supervision. Although the treatment of psychological disturbance remained within the purview of the medical profession, social workers supervised former patients and, except in acute cases, dealt with the ex-patients’ various psychosocial needs. Ex-patients in family care homes were often on probationary leave from the hospital and could be moved from one family care setting to another or back to the hospital at the discretion of the social worker in charge. To the extent that placements were in good supply, this discretionary power was believed to be an important factor in maintaining high-quality care.

With the growing recognition of patients’ rights, placement workers lost much of the power previously attached to their role. Statutory, judicial, and administrative decisions placed substantial limits on professional discretion and clearly indicated that judgment must err on the side of liberty. Thus, as criteria for involuntary admissions became more stringent, the population of potential clients whose need for institutional care was ambiguous—that group for which the error rate of clinical judgment would be high—was no longer permitted to be admitted involuntarily to mental hospitals. The rationale for this decision was that the benefits of institutional treatment of this group as a whole could not be expected to exceed the therapeutic liabilities of forced treatment or to justify the abrogation of a citizen’s right to liberty. 5

RIGHT TO FAIL

The growing emphasis on the civil rights of patients did more than remove power from placement workers. Mandates for treatment in the least restrictive environment, for the right to treatment rather than mere custodial care, and for the right to refuse treatment have molded the placement worker’s role, providing a framework or model for decision-making and practice. These mandates stimulated the development of a new logic of decision-making, based on the overt consideration of statistical risk. The placement worker must now continually weigh the client’s ability to cope with minimally restrictive environments against the repercussions of failure. This is certainly not a new dilemma in social work practice. However, now the client’s right to fail—and perhaps even his or her right to fail repeatedly—is mandated by law.

Optimally, a placement worker encourages constructive risk-taking while minimizing the impact of failure. To achieve this, systematic attention must be paid to each case, and individualized social support for clients must be developed. Stein, Test, and Marx defined such support as the set of relationships adequate to assure that a client’s needs are addressed without discouraging self-sufficiency. 6 Individualized social support requires a thorough assessment of the client’s current problem-solving capabilities and the existing set of effective and affective relationships, that is, an assessment of the relationship between the client’s mental status and the social context in which the client functions.

Mental status must be assessed in terms of the client’s tolerance of social relationships and the impact of the client’s mental status on those relationships. This assessment ought to include attention to a client’s ability to function within a set of reciprocal relations rather than in a dependent manner. With such an assessment in mind and by monitoring each case, the worker may develop necessary buttresses and change them as necessary to provide either more support or less support, depending on the client’s social situation and mental status.

FOUR ISSUES

In the future, social workers in community care must attend to four salient issues within a minimum treatment or confinement/right-to-fail framework: (1) the burden on the community of a concentrated number of ex-mental patients, (2) matching clients to optimal environments, (3) case management, and (4) medication.

Burden on the Community

Many urban communities have been overwhelmed by an influx of ex-mental patients. Their courts are clogged with disordered petty offenders and their subway stations and doorways are haunted by disheveled, vaguely menacing individuals whose “community care” has been negligible. Although sheltered-care residents pose some burden to local communities, it is the free-living ex-patients that are the most troublesome and threatening.

Elsewhere, the authors have made some specific recommendations for policy and programs with respect to this population that will not be repeated here. 7 The central point, however, is worth repeating: social support must become more than a casework catch-phrase. Social workers must define in more specific operational ways the meaning of social support systems, especially when networks of kin cannot be activated. Developing effective networks of indigenous helpers is crucial to multiply the effect of such helpers and creates a first line of acceptable response to the periodic crises of ex-patients in the community.

It is not enough to define social support systems the way an anthropologist would limn the structure of mutual aid as it naturally occurs. Social workers must learn how to use and develop natural or surrogate helping networks, and this requires more practice-based research designed to yield practice materials. Although much attention has been focused on support systems, on outreach, and on community-building, little has been accomplished. 8 Nor has the profession oriented curricula in schools of social work to reflect interest in these areas. Thus, a commitment to defining, implementing, and teaching methods of social support is an immediate challenge to the profession.

Matching People to Optimal Environments

To date, the placement of former patients in the community has involved a largely unspecified process of finding the best fit between the client and available environmental options. Researchers and practitioners have emphasized that diverse types of individuals fare differently in treatment environments that present various physical and cultural barriers to adjustment and demand either much or little emotional involvement by residents. 9 Little research has been done on the placement process itself, however. Segal and Aviram described the goal of “best available fit” and the political contingencies associated with its achievement, but research on testable placement models is needed. 10 To this end, practitioners must document the placement-decision process in much greater detail.

Much more also needs to be known about the methods by which social workers monitor the progress of ex-patients in community care. To some extent, this is a matter of understanding the impact of mental disorders on social life to achieve greater benefits for clients from programs. However, “burnout” among practitioners may also be reduced through the study of activities constituting the monitoring role and through adjustments to lesser the tedium of routine and the discouragement that results when clients do not improve.

Case Management

By defining and developing the case management role, social work can build a strong base for its future practice in community care. Because there are as yet no specified methods, case management is little more than a goal of coordinated care. Of particular importance is the question of the role of case management in casework settings: Are case managers to be considered specialists who concentrate on coordinating resources and on continuity of care, or should case management be a general activity of casework to be performed by all workers? Further, can difficult problems of case management, such as the tracking of transient clients, be solved without infringing on the rights of ex-patients?

Surber described five functions of the case manager: assessment, planning, linkage, monitoring, and advocacy. 11 Empirical investigation of such procedures and their relationship to established casework methods, the organization of care, and civil rights issues is the next logical step in the development of an effective case management program.

Consequences of Medication

To the degree that the major tranquilizers measure up to their promised performance—inhibiting the symptoms of psychosis without affecting social functioning—they are not the concern of social welfare. Unfortunately, the drugs fail to perform well for some individuals and produce undesired side effects. Moreover, their administration is abused, and there is a notable lack of adequate supervision and follow-up of patients who receive the drugs.

The consequences of medication—its impact on social functioning—are within the purview of social work practice. The authors do not advocate the prescription of drugs by social workers but emphasize that the behavior and side effects associated with medication should be a part of every mental health social worker’s education. Graduate social work curricula are sorely lacking in this area; consequently, many practitioners are not adequately prepared to understand the important role of medication in their clients’ lives.

In a similar vein, social workers must also be able to intervene in the process of self-medication in which many ex-patients are engaged. It is common to find ex-patients medicating themselves with their own or collectively created concoctions of major tranquilizers, opiates, barbiturates, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and even LSD. 12 If mental health social workers are to understand the behavior of these clients, they must have some education about the effects of these substances, used alone or in combination.

EPIDEMIOLOGICAL MODEL

To some extent, the community mental health movement grew out of the community care movement and its conflict with advocates of improved care in state mental hospitals. Its emergence is usually traced to the passage of the Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963 (P.L. 88–164) that provided for the establishment of community mental health centers in “catchment areas” with at least 75,000 but no more than 200,000 residents.

These centers were to be concerned with the mental health of everyone in their designated areas and, to be eligible for construction funds, were required to provide five services: inpatient, outpatient, partial hospitalization, emergency, and consultation and education. The 1975 amendments to the act (P.L. 94–63) increased the number of required services by seven: diagnostic, rehabilitative, precare and aftercare, training, research and evaluation, screening, and provision for community living arrangements. The legislation also required that the full range of twelve services be provided to children, the elderly, drug abusers or addicts, and alcohol abusers or alcoholics.

The community mental health movement’s focus on community-based treatment and its emphasis on the impact of social life on mental status places it squarely within the domain of social welfare. Indeed, despite the greater authority accorded the medical profession, social workers staff more full-time positions and provide more services than any other professional group in community mental health centers. 13

The comprehensive nature of a good community mental health center complements the traditional versatility of social work and offers many roles for practitioners. Social workers may become involved in every dimension of operation—from administration to emergency services. Theoretically, the community mental health center offers social workers the opportunity to address the needs of the “total” individual, rather than administer treatment geared solely to the improvement of mental status.

The traditional role of the epidemiologist has been to discover the causes of a disorder’s appearance in a population. Usually, epidemiologists specify the causal mechanism and public health practitioners then develop the method of attack on the causal chain.

Figure 1 represents a slightly modified epidemiological model derived from the study of infectious diseases. Although the authors do not mean to imply that mental ill-health is infectious or that the problem confronted necessarily has to be a disease, they believe that this model offers a framework for social work practice in community mental health. It is a framework not only for the delivery of direct services, but also for the planning and evaluation of community mental health services.

Epidemiological Framework

At the direct-service level, the model suggests an investigative, empirical approach to ferreting out and detailing material that enables: the worker to understand and have an effect on each component: the host, the contributors, the environmental factors, and the problem itself. (The term “contributors” has been substituted for the epidemiological term “agents,” since, unlike diseases, the causes of most mental disorders are not known.) Figure 1 depicts the interrelations among the four components of the model. As illustrated by the plus and minus poles of each component, influences are variable. Since all components interact, the process described by the model can, in combination with variable influences, be complex.

All models of this sort are liable to appear simple and mechanistic. It is, therefore, important to keep in mind that the purpose of such a model is to illustrate how a case can be analyzed and evaluated. The model does not provide a formula for clinical judgment; nor is it a graphic representation of wisdom. It is simply a useful way of viewing a human dilemma in its proper context. It is a framework for bringing to bear the most complete and complex information possible.

The social worker’s role is that of a detective working with a client to develop the best understanding of each component. Unlike practice models based exclusively on clinical theory, assumptions about discrete “facts” or about the interaction between components of this model must, whenever possible, be validated or tested. The social worker must use the principles of scientific case study (single-subject designs) to assess changes in clients over time. The worker applies the validation and hypothesis-testing techniques of the field researcher, who uses corroboration, multiple observations, and experimental manipulations to achieve a significant degree of empiricism. 14

Perhaps the best way to understand the validation process is by way of example. Let us take the case of an individual with terminal cancer who tells his social worker that he really wishes that someone would tell him what he suffers from. In this situation the social worker seeks to keep the family functioning as a unit while coming to terms with the imminent death of a member and tries to help the dying person cope with the approach of death.

As a first step, the worker speaks to the physician to confirm the patient’s report. The physician may inform the worker that he has communicated the information to the patient several times. The problem thus appears to be denial in the host . Or the physician may indicate that he has not responded to the patient’s questions. The problem thus appears to be avoidance by the physician, a contributor to the host’s anxiety. The worker must also assess the relationship between the patient and his family to determine the strength of environmental factors contributing to denial, for instance. Following such validation, the worker is prepared to plan a strategy that will enable the physician to communicate the information or the patient to hear and understand what is said. The worker must then check the outcomes during the course of the service relationship and after the designated service period has come to an end.

The epidemiological problem-solving framework accommodates various theoretical approaches and, given the assessment of all four components and their interaction, requires the selection of the most useful alternative interventions. The framework accommodates not only a medical model but also a deviance perspective in that the problem, located with the host, is interactive with environmental contingencies. There is always an emphasis on the environmental context and the constraints applied or degrees of freedom allowed by specified components. Problems that appear similar may be treated differently based on the intransigence or tractability of environmental factors.

With respect to planning and evaluation, the epidemiological framework is founded on a preventive model that is concerned with the maximum utility of mental health services for the social group. Outcome is evaluated in relation to changes in rates of occurrence of specific problems within the group and activities are differentiated by the state of the problem in the host. Activities consist of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention activities are directed toward populations at risk, that is, those individuals with the highest probability of developing a specific problem but who do not as yet have it. They are evaluated in relation to their efficacy in reducing the incidence or number of new cases of a problem. Although all social work skills are used to implement primary-prevention activities, three (consultation and education, crisis intervention, and community organization) have become the major techniques of primary prevention.

Education and consultation programs of community mental health centers have been the focal point of primary prevention. Such programs have involved family life education and lectures on the impact of stress, retirement, and the benefits of social support. In addition to educating the public, the purpose of consultation and education is to develop further the existing helping systems of lay people in a community. For example, self-help organizations or service programs run by church groups may need consultation from professionals to screen participants with serious psychological problems that require the attention of experts. Bartenders may be trained to provide referrals to problem drinkers, or cab drivers may be taught to refer people in crisis to appropriate programs.

Crisis intervention is usually considered to be a technique of primary prevention when applied to persons in crises caused by such events as a natural disaster or the loss of a spouse. However, it is usually associated with secondary prevention when applied to persons with diagnosable conditions. In these cases the crisis is likely to be the precursor of another acute episode of the condition, for example, schizophrenia.

When no clear point of onset of a mental disorder exists, it is difficult to make a distinction between primary and secondary prevention. For example, when considering services to “troubled youths,” whose problems are invariably diffuse and involve them in several systems of care and control, the distinction between primary and secondary prevention has mostly heuristic value. However they are classed, the activities involved in crisis intervention implement the epidemiological approach through aggressive casework and group work efforts to develop resources, muster social support, and increase the-ego strength of clients to facilitate coping.

As a technique of primary prevention, community organization emphasizes local and democratic control of social institutions as a means of buttressing the individual’s sense of personal control through participation and strengthening social bonds by virtue of reciprocal commitments among participants. Thus, participation is seen to be both health promoting and politically effective, contributing to the well-being of individuals and their communities.

Community mental health centers have sponsored such community-organization activities and have also been the targets of mobilized residents, especially in minority-group communities. Community organization has also been used to foster the development of self-help groups, such as extended “nonfamily” networks capable of lending continuous support to the individual and family in stress.

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention activities, such as short-term treatment and crisis intervention, are associated with shortening the duration of a specific problem or treating it before it becomes severe. They are assessed with regard to their effectiveness in decreasing the prevalence of a mental disorder in a community or reducing the total number of cases already suffering from that disorder.

It is in the implementation of secondary prevention activities that the community mental health center has been identified with the less disturbed and more privileged members of a community, and it is in this role that social workers come to be therapists in the narrowest sense of the term. The mandate that community mental health centers serve the total population of a catchment area—and their patent inability to do so—has resulted in the application of resources according to potential demand rather than to severity of need.

Thus, community mental health centers gear their services to middle-class people, whose only previous resource was the mental hospital if they could not afford private psychiatric care. This is an important achievement, but frequently it has come at the expense of the chronically ill, the poor, and ethnic and sexual minorities, who often need different services in alternative settings. This problem is especially important in view of the virtual monopoly that community health centers have on federal mental health funds.

To a great extent, community mental health centers have been the victims of incompatible demands. All the people cannot be pleased all the time—and certainly not under one roof or by one agency. Thus, the last decade has seen the growth of private, usually small, mental health agencies serving groups underserved by community mental health centers. Social workers have been important participants in these alternative efforts as administrators, caseworkers, therapists, and advocates. They have also emerged as the professional links between these agencies and established centers. Thus if a rapprochement is forthcoming, it is likely that social workers will negotiate its terms.

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention activities are concerned with the reduction of disorder-related problems in a population. They have been largely associated with the care and rehabilitation of the chronically mentally ill and with the deinstitutionalization movement. It appears that shorter hospital stays have reduced the occurrence of the iatrogenic effects of institutional care. However, assumptions that community mental health centers would provide the care necessary to prevent the postinstitutional deterioration of ex-patients have not proved true. Community mental health centers and the social workers practicing in them have been severely criticized for their inattention to the chronically disordered, and statistics have supported these criticisms. 15

Following these criticisms, and in response to the mandates of the 1975 amendments to the Community Mental Health Centers Act, community mental health centers have begun to provide more appropriate services to the chronically mentally ill. Social workers have been outposted or detached to work with ex-patients in single-room occupancy hotels, sheltered-care homes, and private residences. 16 They have also become advocates of patients’ rights. Still, these efforts are far short of what is necessary to prevent the grave consequences of chronic disorders.

SOCIAL WORK OBJECTIVES

The role of social workers in community mental health is embedded in the broader relationship of people to social institutions. Social work’s concern with the quality of life is sanctioned by the social system and involves, of necessity, some commitment to the institutions that organize and govern secular life. This responsibility does not preclude activities directed toward social change. Indeed, to be fully responsible in any society requires a commitment to social change.

However, social workers are creatures of society’s mandate and must keep in mind that the needs of the individual arise in a given social context and must be weighed against the claims of the social group. Social work educators, in particular, must confront the last decade’s fashionable narcissism. Social work’s commitment to equity, social responsibility, relatedness, and sacrifice should be a source of pride for practitioners and should not be dismissed on the road to the practice of psychotherapy.

Social work’s efforts to define and develop its practice in community mental health must address specific and difficult problems currently facing the field, such as violence in families. The profession must also respond to the needs of underserved population groups. In considering the individual’s relationship to the social group, social work must balance primary prevention efforts against services to the chronically ill. The former is an efficient approach to the social group, the latter is a commitment to serving the individual. One should keep in mind these issues and the practice frameworks described in this article in reading the following summary of their relationships to the basic objectives of social work.

Help people enlarge their competence and increase their problem-solving and coping abilities.

The legal/administrative model of community care stresses the first objective of social work practice: to help people enlarge their competence and increase their problem-solving and coping abilities. Emphasis in community care is placed on intervention that provides necessary support without discouraging self-sufficiency. Error in treatment is calculated to occur on the side of the individual’s right to risk failure. Thus the individual is to be served in the least restrictive environment possible and always encouraged to do for himself or herself.

The epidemiological model of community mental health places an emphasis on the host, beginning where he or she is and encouraging the use and development of problem-solving and coping abilities necessary to affect environmental contingencies, contributors to the problem, and the problem itself.

Facilitate interaction between individuals and others in their environment.

The community approach in community care and in community mental health emphasizes the individual’s formal and informal association with groups. It is the “functional community” that most directly affects the individual’s ability to live as an integrated member of society and to achieve a satisfactory state of mental well-being. In describing the individual’s functional community, Caplan referred to the social support system. 17 This system consists of others in the environment who provide help in three ways: (1) They help the individual mobilize psychological resources and master emotional burdens. (2) They share tasks. (3) They provide extra supplies of money, material, tools and cognitive guidance to improve the individual’s situation.

Help people obtain resources.

Segal, Baumohl, and Johnson, drawing on Wiseman, view the function of social support as providing the individual with “social margin”—that leeway for error or disreputability which facilitates survival even in the meanest circumstances. 18 Social margin consists of the relationships, possessions, skills, and personal attributes that can be mortgaged, used, sold, or bartered in return for necessary assistance in prospering or surviving in society. It derives from the interaction among individuals and between individuals and institutions. When the social work profession seeks to improve such interactions, it is trying to increase the social margin of its clients.

Clearly, this improvement may be brought about in numerous ways, including those related to the three remaining objectives of social work: make organizations responsive to people, influence interaction between organizations and institutions, and influence social and environmental policy . In the community mental health field, virtually every activity, from individual casework to community organization, is an attempt to develop the relatedness required to prevent the stresses that seem to forecast the occurrence of a mental disorder or to relieve those which prolong its duration or make its chronic presence more agonizing.

The evaluative component of the epidemiological model emphasizes benefits to the social group, defined in practice as the residents of a particular catchment area. The policies, formal and informal, that govern the organization of care in any area have a substantial impact on the lives of individuals and consequently on the rates of incidence and prevalence of a mental disorder. Criteria for eligibility and barriers to comprehensive or continuous care are, among others, elements of policy and organizational behavior that should be of great concern to social workers in community mental health. These are not simply problems for mental health administrators or for politicians concerned with the formulation of social welfare policy and program. They are issues that affect almost every case.

Aside from organized political activity, which the authors recommend, and in addition to the promotion of more social workers to administrative and policy making positions, the responsiveness of institutions is most affected by the profession through case management, especially through the activities of brokerage and advocacy. As was observed previously in the article, the mental health field is not always or even usually organized in a manner that permits a comprehensive response to those in need. Short of the creation of a mammoth mental health empire, this will always be true. From case management specifically and from good casework generally comes the simultaneous concern for mental and social well-being that forms disparate helping activities into a coherent whole in the service of each client. To see the person in environment obliges social workers to see the person in relation to the organization of care.

The mental health field has moved increasingly into the realm of social welfare, focusing its interventions on the relationship between individuals and institutions. As a result, social work has become the mainstay of mental health’s community-based efforts.

In the future, mental health social workers must develop additional skills to cope with the compound human problems they face daily. They must become adept intervenors in crises, develop a greater awareness of the impact of drugs on social functioning, better define and implement methods of social support and case management, and better describe and evaluate the discrete methods of their profession.