- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Personal growth and transformation

- Managing yourself

- Authenticity

- Business communication

- Continuous learning

My Inglorious Road to Success

- Warren Bennis

- From the July–August 2010 Issue

How to Become More Adaptable in Challenging Situations

- Jacqueline Brassey

- Aaron De Smet

- March 03, 2023

Overcoming Self-Doubt in the Face of a Big Promotion

- Sabina Nawaz

- March 29, 2022

Life’s Work: An Interview with Patti Smith

- Alison Beard

- From the March–April 2023 Issue

How to Have a Successful Meeting with Your Boss's Boss

- Melody Wilding

- September 19, 2023

Why Success Doesn't Lead to Satisfaction

- Ron Carucci

- January 25, 2023

NETW04: Expand Your Network: Caleb

- Harvard Business Publishing

- April 30, 2024

You and Your Executive Coach Are a Bad Match. Now What?

- Sharon Dougherty

- March 22, 2019

Stretch Goals Aren't Comfortable

- Elizabeth Grace Saunders

- June 16, 2015

How to Fake It When You're Not Feeling Confident

- Rebecca Knight

- June 07, 2016

Balance Your Trust Wobbles

- Frances X. Frei

- September 25, 2021

How High Achievers Overcome Their Anxiety

- Morra Aarons-Mele

Don’t Focus on Your Job at the Expense of Your Career

- Dorie Clark

- August 12, 2022

Failure Chronicles

- Linda Rottenberg

- Anthony K. Tjan

- Roger McNamee

- Wayne Pacelle

- Peter Guber

- Whitney Johnson

- Dave Strubler

- From the April 2011 Issue

The Transformer CLO

- Abbie Lundberg

- George Westerman

- From the January–February 2020 Issue

The Existential Necessity of Midlife Change

- Carlo Strenger

- Arie Ruttenberg

- From the February 2008 Issue

A New Will to Win

- Daniel McGinn

- From the September 2010 Issue

The Great Resignation or the Great Rethink?

- Ranjay Gulati

- March 22, 2022

How to Strengthen Your Relationship with a Career Sponsor

- Rachel Simmons

- August 17, 2023

Big Shoes to Fill (HBR Case Study)

- Michael Beer

- May 01, 2006

Imagination Games: Tools for Sparking Innovative Business Ideas

- Martin Reeves

- Jack Fuller

- November 15, 2022

The Upside of Uncertainty Toolkit

- Nathan R. Furr

- Susannah Harmon Furr

- January 01, 2023

In-housing Digital Marketing at Sprint Corp.

- David E. Bell

- Olivia Hull

- June 03, 2020

Negotiating Corporate Change: Confidential Information, David Carlson, VP, Management Information Systems

- James K. Sebenius

- January 08, 1997

Negotiating Corporate Change: Confidential Information, Helen Freeman, VP, Small Appliances Division

Hilti fleet management (b): towards a new business model.

- Ramon Casadesus-Masanell

- Oliver Gassmann

- Roman Sauer

- May 04, 2017

Mekong Capital - Adding Value Through Transformation

- Gregory Unruh

- January 01, 2020

FAW-Volkswagen Audi: Pioneering the Future (2012-Present)

- F. Warren McFarlan

- Shanshan Cao

- Yuanyuan Yu

- December 05, 2016

HBR Daily Leader: Everyday Wisdom for Exceptional Leadership

- Harvard Business Review

- December 03, 2024

The New Strategic Frontier: Environment, Sustainability, and Entrepreneurial Innovation

- Andrea Larson

- March 11, 2003

Cardinal Health: Deploying Blockchain Technology

- R. Chandrasekhar

- February 27, 2023

Akbank: Options in Digital Banking

- June 21, 2015

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals in 2009: Operational Transformation

- Robert D. Landel

- Rebecca Oliver

- December 23, 2009

Analytics-Driven Transformation at Majid Al Futtaim: Building a Data-Driven, Test-&-Learn Culture to Drive Customer Value across Touchpoints in the Middle East

- David Dubois

- Joerg Niessing

- Katia Kachan

- July 01, 2020

- Ray A. Goldberg

- Matthew Preble

- August 21, 2012

Transformation of IBM

- David B. Yoffie

- Andrall E. Pearson

- November 06, 1990

Managing Your Anxiety (HBR Emotional Intelligence Series)

- Alice Boyes

- Judson Brewer

- Rasmus Hougaard

- Jacqueline Carter

- January 23, 2024

Royal Bank of Canada: Using People Strategy and Analytics to Drive Employee Performance (B)

- Debra Schifrin

- Kathryn Shaw

- October 11, 2017

RBC: Transforming Transformation (A)

- Ethan S. Bernstein

- Francesca Gino

Lada do Brasil

- James E. Austin

- Helen Shapiro

- Nilgun Gokgur

- March 26, 1992

Hilti (A): Fleet Management?, Teaching Note

- Jan W. Rivkin

- July 01, 2018

How to Make Great Decisions, Quickly

- Martin G Moore

The Best Mentorships Help Both People Grow

- January 05, 2022

Succeeding as a First-Time Manager

- HANNAH BATES

- Amy Bernstein

- June 21, 2023

Popular Topics

Partner center.

How to Create a Personal Development Plan: 3 Examples

For successful change, it is vital that the client remains engaged, recognizing and identifying with the goals captured inside and outside sessions. A personal development plan (PDP) creates a focus for development while offering a guide for life and future success (Starr, 2021).

This article introduces and explores the value of personal development plans, offering tools, worksheets, and approaches to boost self-reflection and self-improvement.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques to create lasting behavior change.

This Article Contains

What is personal development 7 theories, coaching in personal development and growth, how to create a personal development plan, 3 examples of personal development plans, defining goals and objectives: 10 tips and tools, fostering personal development skills, 3 inspiring books to read on the topic, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message, frequently asked questions.

Personal development is a fundamental concept in psychology and encompasses the lifelong process of self-improvement, self-awareness, and personal growth. Crucial to coaching and counseling, it aims to enhance various aspects of clients’ lives, including their emotional wellbeing, relationships, careers, and overall happiness (Cox, 2018; Starr, 2021).

Several psychological models underpin and support transformation. Together, they help us understand personal development in our clients and the mechanisms and approaches available to make positive life changes (Cox, 2018; Passmore, 2021).

The following psychological theories and frameworks underpin and influence the approach a mental health professional adopts.

1. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

As a proponent of the humanistic or person-centered approach to helping people, Abraham Maslow (1970) suggested that individuals have a hierarchy of needs. Simply put, they begin with basic physiological and safety needs and progress through psychological and self-fulfillment needs.

Personal development is often found in or recognized by the pursuit of higher-level needs, such as self-esteem and self-actualization (Cox, 2018).

2. Erikson’s psychosocial development

Erik Erikson (1963) mapped out a series of eight psychosocial development stages that individuals go through across their lifespan.

Each one involves challenges and crises that once successfully navigated, contribute to personal growth and identity development.

3. Piaget’s cognitive development

The biologist and epistemologist Jean Piaget (1959) focused on cognitive development in children and how they construct their understanding of the world.

We can draw on insights from Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, including intellectual growth and adaptability, to inform our own and others’ personal development (Illeris, 2018).

4. Bandura’s social cognitive theory

Albert Bandura’s (1977) theory highlights the role of social learning and self-efficacy in personal development. It emphasizes that individuals can learn and grow through observation, imitation, and belief in their ability to effect change.

5. Self-determination theory

Ryan and Deci’s (2018) motivational self-determination theory recognizes the importance of autonomy, competence, and relatedness in personal development.

Their approach suggests that individuals are more likely to experience growth and wellbeing when such basic psychological needs are met.

6. Positive psychology

Positive psychology , developed by Martin Seligman (2011) and others, focuses on strengths, wellbeing, and the pursuit of happiness.

Seligman’s PERMA model offers a framework for personal development that emphasizes identifying and using our strengths while cultivating positive emotions and experiences (Lomas et al., 2014).

7. Cognitive-Behavioral Theory (CBT)

Developed by Aaron Beck (Beck & Haigh, 2014) and Albert Ellis (2000), CBT explores the relationship between thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

As such, the theory provides practical techniques for personal development, helping individuals identify and challenge negative thought patterns and behaviors (Beck, 2011).

Theories like the seven mentioned above offer valuable insights into many of the psychological processes underlying personal development. They provide a sound foundation for coaches and counselors to support their clients and help them better understand themselves, their motivations, and the paths they can take to foster positive change in their lives (Cox, 2018).

The client–coach relationship is significant to successful growth and goal achievement.

Typically, the coach will focus on the following (Cox, 2018):

- Actualizing tendency This supports a “universal human motivation resulting in growth, development and autonomy of the individual” (Cox, 2018, p. 53).

- Building a relationship facilitating change Trust clients to find their own way while displaying empathy, congruence, and unconditional positive regard . The coach’s “outward responses consistently match their inner feelings towards a client,” and they display a warm acceptance that they are being how they need to be (Passmore, 2021, p. 162).

- Adopting a positive psychological stance Recognize that the client has the potential and wish to become fully functioning (Cox, 2018).

Effective coaching for personal growth involves adopting and committing to a series of beliefs that remind the coach that the “coachee is responsible for the results they create” (Starr, 2021, p. 18) and help them recognize when they may be avoiding this idea.

The following principles are, therefore, helpful for coaching personal development and growth (Starr, 2021).

- Stay committed to supporting the client. While initially strong, you may experience factors that reduce your sense of support for the individual’s challenges.

- Coach nonjudgmentally. Our job is not to adopt a stance based on personal beliefs or judgment of others, but to help our clients form connections between behavior and results.

- Maintain integrity, openness, and trust. The client must feel safe in your company and freely able to express themselves.

- Responsibility does not equal blame. Clients who take on blame rather than responsibility will likely feel worse about something without acknowledging their influence on the situation.

- The client can achieve better results. The client is always capable of doing and achieving more, especially in relation to their goals.

- Focus on clients’ thoughts and experiences. Collaborative coaching is about supporting the growth and development of the client, getting them to where they want to go.

- Clients can arrive at perfect solutions. “As a coach, you win when someone else does” (Starr, 2021, p. 34). The solution needs to be the client’s, not yours.

- Coach as an equal partnership. Explore the way forward together collaboratively rather than from a parental or advisory perspective.

Creating a supportive and nonjudgmental environment helps clients explore their thoughts, feelings, and goals, creating an environment for personal development and flourishing (Passmore, 2021).

Download 3 Free Goals Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients create actionable goals and master techniques for lasting behavior change.

Download 3 Free Goals Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

A personal development plan is a powerful document “to create mutual clarity of the aims and focus of a coaching assignment” (Starr, 2021, p. 291). While it is valuable during coaching, it can also capture a client’s way forward once sessions have ended.

Crucially, it should have the following characteristics (Starr, 2021):

- Short and succinct

- Providing a quick reference or point of discussion

- Current and fresh, regularly revised and updated

Key elements of a personal development plan include the following (Starr, 2021):

- Area of development This is the general skill or competence to be worked on.

- Development objectives or goals What does the client want to do? Examples might include reducing stress levels, improving diet, or managing work–life balance .

- Behaviors to develop These comprise what the client will probably do more of when meeting their objectives, for example, practicing better coping mechanisms, eating more healthily, and better managing their day.

- Actions to create progress What must the client do to action their objectives? For example, arrange a date to meet with their manager, sign up for a fitness class, or meet with a nutritionist.

- Date to complete or review the objective Capture the dates for completing actions, meeting objectives, and checking progress.

Check out Lindsey Cooper’s excellent video for helpful guidance on action planning within personal development.

We can write and complete personal development plans in many ways. Ultimately, they should meet the needs of the client and leave them with a sense of connection to and ownership of their journey ahead (Starr, 2021).

- Personal Development Plan – Areas of Development In this PDP , we draw on guidance from Starr (2021) to capture development opportunities and the behaviors and actions needed to achieve them.

- Personal Development Plan – Opportunities for Development This template combines short- and long-term goal setting with a self-assessment of strengths, weaknesses, and development opportunities.

- Personal Development Plan – Ideal Self In this PDP template , we focus on our vision of how our ideal self looks and setting goals to get there.

“The setting of a goal becomes the catalyst that drives the remainder of the coaching conversation.”

Passmore, 2021, p. 80

Defining goals and objectives is crucial to many coaching conversations and is usually seen as essential for personal development.

Check out this video on how you can design your life with your personal goals in mind.

The following coaching templates are helpful, containing a series of questions to complete Whitmore’s (2009) GROW model :

- G stands for Goal : Where do you want to be?

- R stands for Reality : Where are you right now with this goal?

- O stands for Options : What are some options for reaching your goal?

- W stands for Way forward : What is your first step forward?

Goal setting creates both direction and motivation for clients to work toward achieving something and meeting their objectives (Passmore, 2021).

The SMART goal-setting framework is another popular tool inside coaching and elsewhere.

S = Specific M = Measurable A = Attainable/ or Agreed upon R = Realistic T = Timely – allowing enough time for achievement

The SMART+ Goals Worksheet contains a series of prompts and spaces for answers to define goals and capture the steps toward achieving them.

We can summarize the five principles of goal setting (Passmore, 2021) as follows:

- Goals must be clear and not open to interpretation.

- Goals should be stretching yet achievable.

- Clients must buy in to the goal from the outset.

- Feedback is essential to keep the client on track.

- Goals should be relatively straightforward. We can break down complex ones into manageable subgoals.

The following insightful articles are also helpful for setting and working toward goals.

- What Is Goal Setting and How to Do it Well

- The Science & Psychology of Goal-Setting 101

1. People skills

Improving how we work with others benefits confidence, and with other’s support, we are more likely to achieve our objectives and goals. The following people skills can all be improved upon:

- Developing rapport

- Assertiveness and negotiation

- Giving and receiving constructive criticism

2. Managing tasks and problem-solving

Inevitably, we encounter challenges on our path to development and growth. Managing our activities and time and solving issues as they surface are paramount.

Here are a few guidelines to help you manage:

- Organize time and tasks effectively.

- Learn fundamental problem-solving strategies.

- Select and apply problem-solving strategies to tackle more complex tasks and challenges.

- Develop planning skills, including identifying priorities, setting achievable targets, and finding practical solutions.

- Acquire skills relevant to project management.

- Familiarize yourself with concepts such as performance indicators and benchmarking.

- Conduct self-audits to assess and enhance your personal competitiveness.

3. Cultivate confidence in your creative abilities

Confidence energizes our performance. Knowing we can perform creatively encourages us to develop novel solutions and be motivated to transform.

Consider the following:

- Understand the fundamentals of how the mind works to enhance your thinking skills.

- Explore a variety of activities to sharpen your creative thinking.

- Embrace the belief that creativity is not limited to artists and performers but is crucial for problem-solving and task completion.

- Learn to ignite the spark of creativity that helps generate innovative ideas when needed.

- Apply creative thinking techniques to enhance your problem-solving and task completion abilities.

- Recognize the role of creative thinking in finding the right ideas at the right time.

To aid you in building your confidence, we have a whole category of articles focused on Optimism and Mindset . Be sure to browse it for confidence-building inspiration.

With new techniques and technology, our understanding of the human brain continues to evolve. Identifying the vital elements involved in learning and connecting with others offers deep insights into how we function and develop as social beings. We handpicked a small but unique selection of books we believe you will enjoy.

1. The Coaching Manual: The Definitive Guide to the Process, Principles and Skills of Personal Coaching – Julie Starr

This insightful book explores and explains the coaching journey from start to finish.

Starr’s book offers a range of free resources and gives clear guidance to support new and existing coaches in providing practical help to their clients.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. The Big Leap: Conquer Your Hidden Fear and Take Life to the Next Level – Gay Hendricks

Delving into the “zone of genius” and the “zone of excellence,” Hendricks examines personal growth and our path to personal success.

This valuable book explores how we eliminate the barriers to reaching our goals that arise from false beliefs and fears.

3. The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are – Brené Brown

Brown, a leading expert on shame, vulnerability, and authenticity, examines how we can engage with the world from a place of worthiness.

Use this book to learn how to build courage and compassion and realize the behaviors, skills, and mindset that lead to personal development.

We have many resources available for fostering personal development and supporting client transformation and growth.

Our free resources include:

- Goal Planning and Achievement Tracker This is a valuable worksheet for capturing and reflecting on weekly goals while tracking emotions that surface.

- Adopt a Growth Mindset Successful change is often accompanied by replacing a fixed mindset with a growth one .

- FIRST Framework Questions Understanding a client’s developmental stage can help offer the most appropriate support for a career change.

More extensive versions of the following tools are available with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit© , but they are described briefly below:

- Backward Goal Planning

Setting goals can build confidence and the skills for ongoing personal development.

Backward goal planning helps focus on the end goal, prevent procrastination, and decrease stress by ensuring we have enough time to complete each task.

Try out the following four simple steps:

- Step one – Identify and visualize your end goal.

- Step two – Reflect on and capture the steps required to reach the goal.

- Step three – Focus on each step one by one.

- Step four – Take action and record progress.

- Boosting Motivation by Celebrating Micro Successes

Celebrating the small successes on our journey toward our goals is motivating and confidence building.

Practice the following:

- Step one – Reflect momentarily on the goal you are working toward.

- Step two – Consider each action being taken to reach that goal.

- Step three – Record the completion of each action as a success.

- Step four – Choose how to celebrate each success.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others reach their goals, check out this collection of 17 validated motivation & goal achievement tools for practitioners. Use them to help others turn their dreams into reality by applying the latest science-based behavioral change techniques.

17 Tools To Increase Motivation and Goal Achievement

These 17 Motivation & Goal Achievement Exercises [PDF] contain all you need to help others set meaningful goals, increase self-drive, and experience greater accomplishment and life satisfaction.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Personal development has a rich and long history. It is underpinned by various psychological theories and remains a vital aspect of creating fulfilling lives inside and outside coaching and counseling.

For many of us, self-improvement, self-awareness, and personal growth are vital aspects of who we are. Coaching can provide a vehicle to help clients along their journey, supporting their sense of autonomy and confidence and highlighting their potential (Cox, 2018).

Working with clients, therefore, requires an open, honest, and supportive relationship. The coach or counselor must believe the client can achieve better results and view them nonjudgmentally as equal partners.

Personal development plans become essential to that relationship and the overall coaching process. They capture areas for development, skills and behaviors required, and goals and objectives to work toward.

Use this article to recognize theoretical elements from psychology that underpin the process and use the skills, guidance, and worksheets to support personal development in clients, helping them remove obstacles along the way.

Ultimately, personal development is a lifelong process that boosts wellbeing and flourishing and creates a richer, more engaging environment for the individual and those around them.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Goal Achievement Exercises for free .

Personal development is vital, as it enables individuals to enhance various aspects of their lives, including emotional wellbeing, relationships, careers, and overall happiness.

It promotes self-awareness, self-improvement, and personal growth, helping individuals reach their full potential and lead fulfilling lives (Passmore, 2021; Starr, 2021).

Personal development is the journey we take to improve ourselves through conscious habits and activities and focusing on the goals that are important to us.

Personal development goals are specific objectives individuals set to improve themselves and their lives. Goals can encompass various areas, such as emotional intelligence, skill development, health, and career advancement, providing direction and motivation for personal growth (Cox, 2018; Starr, 2021).

A personal development plan typically comprises defining the area of development, setting development objectives, identifying behaviors to develop, planning actions for progress, and establishing completion dates. These five stages help individuals clarify their goals and track their progress (Starr, 2021).

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory . Prentice-Hall.

- Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. P. (2014). Advances in cognitive therapy and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 10 , 1–24.

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond . Guilford Press.

- Cottrell, S. (2015). Skills for success: Personal development and employability . Bloomsbury Academic.

- Cox, E. (2018). The complete handbook of coaching . SAGE.

- Ellis, A. (2000). Can rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) be effectively used with people who have devout beliefs in God and religion? Professional Psychology-Research and Practice , 31 (1), 29–33.

- Erikson, E. H. (1963). Youth: Change and challenge . Basic Books.

- Illeris, K. (2018). An overview of the history of learning theory. European Journal of Education , 53 (1), 86–101.

- Lomas, T., Hefferon, K., & Ivtzan, I. (2014). Applied positive psychology: Integrated positive practice . SAGE.

- Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personalit y (2nd ed.). Harper & Row.

- Passmore, J. (Ed.). (2021). The coaches’ handbook: The complete practitioner guide for professional coaches . Routledge.

- Piaget, J. (1959): The Psychology of intelligence . Routledge.

- Rose, C. (2018). The personal development group: The students’ guide . Routledge.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness . Guilford Press.

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Authentic happiness using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment . Nicholas Brealey.

- Starr, J. (2021). The coaching manual: The definitive guide to the process, principles and skills of personal coaching . Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Whitmore, J. (2009). Coaching for performance . Nicholas Brealey.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

How to Become an ADHD Coach: 5 Coaching Organizations

The latest figures suggest that around 1 in 20 people globally has ADHD, although far fewer are actively diagnosed (Asherson et al., 2022). Attention-deficit hyperactivity [...]

Personal Development Goals: Helping Your Clients Succeed

In the realm of personal development, individuals often seek to enhance various aspects of their lives, striving for growth, fulfillment, and self-improvement. As coaches and [...]

How to Perform Somatic Coaching: 9 Best Exercises

Our bodies are truly amazing and hold a wellspring of wisdom which, when tapped into, can provide tremendous benefits. Somatic coaching acknowledges the intricate connection [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (44)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Your browser is ancient! Upgrade to a different browser or install Google Chrome Frame to experience this site.

Personal Development Plans: Case Studies of Practice

By the mid 1990s Personal Development Plans had rapidly gained in popularity as a tool for encouraging employees to think through their own development needs and action plan for their careers and skill development.

This report, based on case study research of leaders in this field, gives practitioners clear descriptions of what PDPs really are, how they fit in with other HR processes, and how they are working in practice. The eight named case studies include TSB, BP Chemicals, Marks and Spencer and Abbey National.

The report also raises some wider policy issues and choices in using PDPs as part of a strategy of self-development.

Publication details

Tagged with.

- Work for employers

- Learning and employee development

- Learning strategy

You currently have 0 items in your shopping basket

View My Basket

Related links

- 🔗 Report summary: Personal Development Plans: Case Studies of Practice

Sign up to our newsletter

Register for tailored emails with our latest research, news, blogs and events on public employment policy or human resources topics.

By continuing to use the site, you agree to the use of cookies. more information Accept

The cookie settings on this website are set to "allow cookies" to give you the best browsing experience possible. If you continue to use this website without changing your cookie settings or you click "Accept" below then you are consenting to this.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, personal development plans: insights from a case based approach.

Journal of Workplace Learning

ISSN : 1366-5626

Article publication date: 11 July 2016

In light of contemporary shifts away from annual appraisals, this study aims to explore the implications of using a personal development plan (PDP) as a means of focussing on continuous feedback and development to improve individual performance and ultimately organisational performance.

Design/methodology/approach

Data were collected through an employee survey in one private sector organisation in the UK finance sector using a case study approach. Secondary data in the form of completed PDPs were used to compare and contrast responses to the survey.

Results indicate that the diagnostic stage is generally effective, but support for the PDP and development activity post diagnosis is less visible. Implications of this are that time spent in the diagnostic stage is unproductive and could impact on motivation and self-efficacy of employees. Furthermore, for the organisation to adopt a continuous focus on development via PDPs would necessitate a systematic training programme to effect a change in culture.

Research limitations/implications

This study was limited to one organisation in one sector which reduces the generalisability of results. Research methods were limited to anonymous survey, and a richer picture would be painted following qualitative interviews. There was also a subconscious bias towards believing that a PDP containing documented goals would lead to improved individual and organisation performance; However, the discussion has identified the concept of subconscious priming which implies that verbal goals may be equally valid, and further comparative research between verbal and written goals is recommended.

Practical implications

The results indicate the potential value that using PDPs could bring to an organisation as an alternative to annual appraisal, subject to a supportive organisational culture.

Originality/value

PricewaterhouseCoopers, in a recent article for CIPD (2015), reported that two-thirds of large companies are planning to rethink their annual appraisal system. One of the key drivers for this was the desire for more regular feedback. Given the recent shift in thinking, little research has been conducted into what would replace the annual appraisal. This paper therefore focusses on the extent to which PDPs can contribute to supporting this more regular contact and feedback.

- Performance management

- Human resource development

- Workplace learning

- Management development

- Annual appraisal

- Personal development plan

Greenan, P. (2016), "Personal development plans: insights from a case based approach", Journal of Workplace Learning , Vol. 28 No. 5, pp. 322-334. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-09-2015-0068

Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2016, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Personality development in emerging adulthood—how the perception of life events and mindset affect personality trait change.

- 1 Personality Psychology and Psychological Assessment, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2 Division HR Diagnostics AG, Stuttgart, Germany

Personality changes throughout the life course and change is often caused by environmental influences, such as critical life events. In the present study, we investigate personality trait development in emerging adulthood as a result of experiencing two major life events: graduating from school and moving away from home. Thereby, we examined the occurrence of the two life events per se and the subjective perception of the critical life event in terms of valence. In addition, we postulate a moderation effect of the construct of mindset, which emphasizes that beliefs over the malleability of global attributes can be seen as predictors of resilience to challenges. This suggests that mindset acts as a buffer for these two distinct events. In a large longitudinal sample of 1,243 people entering adulthood, we applied latent structural equation modeling to assess mean-level changes in the Big Five, the influence of life events per se , the subjective perception of life events, and a moderating role of mindset. In line with maturity processes, results showed significant mean-level changes in all Big Five traits. While no changes in the Big Five dimensions were noted when the mere occurrence of an event is assessed, results indicated a greater increase in extraversion and diminished increase in emotional stability when we accounted for the individual's (positive/negative) perception of the critical life event. In case of extraversion, this also holds true for the moderator mindset. Our findings contribute valuable insights into the relevance of subjective appraisals to life events and the importance of underlying processes to these events.

Introduction

People change as they age. Individuals experience not only physical but also psychological changes across the entire lifespan. However, the exact course of internal and external changes depends on various criteria. In recent years, researchers have expended considerable effort in studying how personality develops across the lifespan; this has, in turn, incited a controversy about the stability and variability of specific personality traits. Personality traits are considered to be relatively stable individual differences in affect, behavior, and/or cognition ( Johnson, 1997 ). Whereas, the Big Five traits of conscientiousness and agreeableness appear to be rather stable and continuously increase across adulthood, levels of openness to experience appear to change in an inverted U-shape function, which increases between the ages of 18 and 22 and decreases between 60 and 70 ( McCrae and Costa, 1999 ; Roberts and DelVecchio, 2000 ; Specht et al., 2011 ). Furthermore, some studies have shown that trait change can be associated with particular life stages. For example, the findings of Roberts and Mroczek (2008) suggest that young adults tend to exhibit increases in traits that are indicative of greater social maturity. More specifically, in emerging adulthood, the average individual experiences an increase in emotional stability, conscientiousness, and agreeableness ( Arnett, 2000 ; Roberts et al., 2006 ; Bleidorn, 2015 ), and self-esteem ( Orth et al., 2018 ), while openness to experience seems to decrease in advancing age ( Roberts et al., 2006 ). Taken together, this comprises evidence that personality develops throughout the lifespan and consequently, several theories have been introduced to explain when and why personality change occurs (e.g., Cattell, 1971 ; Baltes, 1987 ; Caspi and Moffitt, 1993 ; McCrae and Costa, 1999 ; Roberts and Mroczek, 2008 ).

Critical Life Events

Theory and research support the idea that personality can change as a result of intrinsic factors such as genetics and extrinsic factors such as the environment around us ( Bleidorn and Schwaba, 2017 ; Wagner et al., 2020 ). More specifically, there is ample evidence that personality is linked to certain external influences such as critical life events (e.g., Lüdtke et al., 2011 ; Bleidorn et al., 2018 ). These can be defined as “transitions that mark the beginning or the end of a specific status” ( Luhmann et al., 2012 ; p. 594) and include leaving the parental home or major changes in one's status such as employment or duty. These transitions often require adaptation processes involving new behavioral, cognitive, or emotional responses ( Hopson and Adams, 1976 ; Luhmann et al., 2012 , 2014 ). Profound adaptations are assumed to have lasting effects, as “life events can modify, interrupt or redirect life trajectories by altering individuals' feelings, thoughts and behaviors” ( Bleidorn et al., 2018 , p. 83). Building upon this assumption, many studies have sought to determine how certain Big Five traits change because of critical life events. For instance, increases in emotional stability were found to result from transitioning into one's first romantic relationship ( Lehnart et al., 2010 ). Emotional stability might also increase in anticipation of gain-based events such as childbirth or paid employment, which, in turn, lead to increases in conscientiousness and openness to experience ( Denissen et al., 2018 ).

In the present study, we focus on two critical life events that are highly relevant for emerging adults: moving away from home and graduating from school. Both events represent a personal development milestone for the transition into adulthood and are typically associated with great educational or occupational challenges ( Arnett, 2000 ; Pusch et al., 2018 ). Few studies have highlighted these two events and how they influence life trajectories in emerging adulthood. Lüdtke et al. (2011 ) focused on the broader superordinate section of work-related life events and personality change and found that the transition from high school to college, university, or vocational training is associated with substantial normative increases in emotional stability, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. With regard to graduation from school, Bleidorn (2012) found significant mean-level changes in certain Big Five traits over an observation period of 1 year. Specifically, senior students experienced increases in conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness after graduation. In a later review by Bleidorn et al. (2018) , the authors found that graduation constitutes an almost universal life event in Western societies and that related change in adult personality is likely to be observable, because young adulthood is a period in which personality traits have been shown to be most open to change ( Roberts and DelVecchio, 2000 ; Lucas and Donnellan, 2011 ).

There are fewer investigations into the personality effects of moving away from home. Pusch et al. (2018) compared age differences in emerging vs. young adults and found that, among other life events, leaving the parental home did not reveal significant age effects with respect to personality change. However, they found significant age-invariant effects for individuals who left their parental home recently, indicating positive changes in agreeableness. Jonkmann et al. (2014) investigated living arrangements after college with regard to personality differences and found that, for example, the choice of living arrangement (living with roommates vs. living alone) predicted the development of conscientiousness and—to a lesser extent—openness and agreeableness. Similarly, according to a study by Niehoff et al. (2017) , living and studying abroad after college led to increases in extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability. Interestingly, Specht et al. (2011) found a significant sex effect on leaving the parental home and argued that only women become more emotionally stable when moving. Taken together, this evidence suggests that moving away from home is a major life event that has not yet been deeply investigated but represents a distinct developmental task that has the potential to shape individuals' personalities.

The Perception of Life Events

While these studies provide valuable information about the impact of critical life events, one important issue has been hitherto neglected. Many past studies have focused on life events per se , but comparatively little effort has been made to examine the subjective appraisal of such events and its effect on the processes underlying personality change ( Roberts, 2009 ). Moreover, methodological approaches to life events are sometimes misleading, because the valence of experienced events is rated by either researchers or other people who cannot sufficiently reflect inter- and intra-individual experiences of events ( Headey and Wearing, 1989 ; Kendler et al., 2003 ; Luhmann et al., 2020 ). However, there is ample evidence that people perceive the same event or situation very differently. For example, according to a comprehensive review of person-situation transactions by Rauthmann et al. (2015) , situations can be characterized by their physical (e.g., location, activity, persons) and/or psychological (e.g., task-related, threatening, pleasant) properties. Rauthmann et al. (2015) further state that “situations only have consequences for people's thinking, feeling, desiring, and acting through the psychological processing they receive” (p. 372). Thus, people's individual experiences of psychological situations may deviate from how these situations are experienced by most other people (reality principle). This assumption aligns with the TESSERA framework conceived by Wrzus and Roberts (2017) . According to the authors, events and single situations can trigger expectancies about how to act and adjust in similar situations. These expectancies then determine which state occurs after the corresponding trigger by choosing a response from a variety of possible states ( Wrzus and Roberts, 2017 ). Conjointly, two people can perceive the same situation or event very differently, leading to diverse reactions and psychological meanings.

A first step toward this important distinction was proposed by Luhmann et al. (2020) , who aimed to systematically examined the effects of life events on psychological outcomes. To do so, the authors proposed a dimensional taxonomy which that considers nine perceived characteristics of major life events. I this way, the study uniquely emphasizes the difference between assessing the mere occurrence of a critical life event and taking into account subjective appraisal. However, significantly more research is needed to fully explore how this causes lasting personality trait change.

In conclusion, two aspects of person-situation transactions should be highlighted. First, one situation can be interpreted very differently by two individuals. Expectations and individual goals—as well as variable expressions of personality traits—influence the extent to which a situation is perceived as meaningful and, therefore, determine how people approach it ( Bleidorn, 2012 ; Denissen et al., 2013 , 2018 ). Second, this is also true for life events. Two people can reasonably experience the same major life event as completely differently. Therefore, we focus the present study on the valence of two distinct life events and use this characteristic as our central parameter. In particular, in emerging adulthood, individuals might perceive the behavioral expectations and demands associated with a life event as more pressing than others ( Pusch et al., 2018 ). What remains less clear is how situational perceptions affect personality change after a major life event, but with respect to the current string of literature, it seems reductive to only ask if, but not how, critical life events are experienced.

The Moderating Role of Mindset

In the previous section, we examined how diverse critical life events can be perceived. Here, we extend our theoretical approach by focusing on the underlying processes that might account for the different perception and spotlight causes of individual personality trait changes. One construct that is highly relevant to the aforementioned regulatory mechanisms is the individual belief system mindset. According to Dweck (1999) , an individual's mindset refers to the implicit belief about the malleability of personal attributes. Dweck (1999) distinguishes between growth and fixed mindsets. The growth mindset emphasizes the belief that attributes like intelligence and personality are changeable. Conversely, the fixed mindset refers to the belief that such attributes are immutable. According to Dweck (2012) , the individual mindset is not static and can be changed throughout one's life. Actively changing one's mindset toward a growth mindset was found to decrease chronic adolescent aggression, enhance people's willpower, and redirect critical academic outcomes ( Dweck, 2012 ; Yeager et al., 2019 ). Moreover, Blackwell et al. (2007) found that the belief that intelligence is malleable (incremental theory) predicted an upward trajectory in grades over 2 years of junior high school, while the belief that intelligence is fixed (entity theory) predicted a flat trajectory. Yet, according to a meta-analysis from Sisk et al. (2018) , mindset interventions for academic achievement predominately benefitted students with low socioeconomic status or who are at-risk academically. Mindset has also been linked to business-related outcomes (e.g., Kray and Haselhuhn, 2007 ; Heslin and Vandewalle, 2008 ). That is, individuals with a growth mindset tend to use “higher-order” cognitive strategies and adapt to stress more easily ( Heslin and Vandewalle, 2008 ). Likewise, mindset has been linked to health outcomes and even mental illness, with the assumption that a growth mindset buffers against psychological distress and depression (e.g., Biddle et al., 2003 ; Burnette and Finkel, 2012 ; Schroder et al., 2017 ). Therefore, a growth mindset can be considered a predictor of psychological resilience ( Saeed et al., 2018 ).

With regard to changes in personality traits, the findings have been mixed. Hudson et al. (2020) investigated college students' beliefs by adapting a personality measure into a mindset measure and administering it within a longitudinal study. They found that the mere belief that personality is malleable (or not) did not affect trait changes. However, in her Unified Theory of Motivation, Personality, and Development, Dweck (2017) suggests that basic needs, mental representations (e.g., beliefs and emotions), and action tendencies (referred to as BEATs) contribute to personality development. Dweck further argues that mental representations shape motivation by informing goal selection and subsequently form personality traits by creating recurring experiences ( Dweck, 2017 ). Thus, there might be more information about indicators such as the integration of mindset, motivation, and environmental influences necessary to understand how personality traits change according to belief systems.

In summary, there is evidence that a belief in the malleability of global attributes allows individuals to adapt to life circumstances in a goal-directed way and that individuals' mindsets determine responses to challenges ( Dweck and Leggett, 1988 ). Building upon the existing literature around environmental influences on personality traits and the diverse effects of mindset, we argue that after experiencing a critical life event, individuals with a growth mindset will adapt to a new situation more easily and accordingly exhibit greater change in relating personality traits. In contrast, individuals with a fixed mindset might react in a more rigid way to unknown circumstances and thus don't experience the need adapt, resulting in no personality trait change.

The Present Study

This study aims to contribute to the literature around external and internal influences on personality development in emerging adulthood by analyzing changes in the Big Five, the influences of the occurrence of life events per se vs. their subjective perception, and the possible moderating effects of mindset in a longitudinal study with a large sample. Most prior studies have focused on personality development in adulthood (e.g., Roberts and Jackson, 2008 ; Lucas and Donnellan, 2011 ; Wrzus and Roberts, 2017 ; Damian et al., 2018 ; Denissen et al., 2018 ), but emerging adulthood is marked by tremendous changes; thus, we focus our analyses on this period. According to Arnett (2000 , 2007) , emerging adulthood is considered a distinct stage between adolescence and full-fledged adulthood. This is seen as a critical life period because it is characterized by more transformation, exploration, and personality formation than any other life stage in adulthood ( Arnett, 2000 ; Ziegler et al., 2015 ; Bleidorn and Schwaba, 2017 ). With regard to beliefs systems, Yeager et al. (2019) argue that beliefs that affect how, for example, students make sense of ongoing challenges are most important and salient during high-stakes developmental turning points such as pubertal maturation. For this reason, it is particularly compelling to investigate environmental influences such as major life events that shape the trajectory of personality trait change in emerging adulthood.

To do so, we examined whether two major critical life events (graduating from school and moving away from home) affect personality development. We chose these two major life events because they are uniquely related to emerging adulthood and because existing research has found mixed results regarding their influence on personality trait change (e.g., Lüdtke et al., 2011 ; Specht et al., 2011 ; Pusch et al., 2018 ). Based on prior findings, we constructed three hypotheses. First, we expect that an increase in personality trait change will occur in individuals who graduate from school/move away from home but not in those who did not experience such events. Second, subjective perceptions of the two critical life events will influence personality trait changes in the Big Five. Third, we look at the underlying processes that influence personality and argue, that mindset will moderate the impact of the two stated life events/perception of life events on personality trait change.

Sample and Procedure

For this study, we created the German Personality Panel (GEPP) by collecting data from a large German sample in cooperation with a non-profit online survey provided by berufsprofiling.de . This organization assists emerging adults by providing job opportunities and post-graduation academic pathways. After completing the questionnaire, participants received feedback and vocational guidance. In 2016 and 2017, a total of 11,816 individuals between 13 and 30 years old ( M = 17.72 years; SD = 3.22, 50.71% female) took this survey. We used this first round of data-gathering as our longitudinal measurement occasion T1. If participants consented to be contacted again, we reached out via email in October 2018 to request their participation in a second survey. A total of 1,679 individuals between 14 and 26 years old ( M = 17.39, SD = 2.37, 64.82% female) agreed to participate and filled in a second online survey (second measurement occasion of GEPP, T2). The test battery at T2 took approximately 30–40 min, and we provided personalized feedback on personality development, as well as a monetary compensation, to all participants.

Because we were interested in emerging adults who were about to graduate from school?and thus found themselves in a critical time period?we excluded all participants older than 21 at T2. On the other hand, we included 14-year-old participants because they could have entered school in Germany at the age of five and thus graduated from secondary school and/or moved away from home by this age. At T2, 12% had not yet finished school, 32% held a secondary school certificate, and 57% held a university entrance diploma.

To further improve data quality, we obtained an indicator for careless responding by asking about self-reported diligence (“Did you work conscientiously on the test?”). Participants were informed that their answer had no impact on their compensation. At T2, 41 (3%) participants answered “No.” After excluding participants meeting this criterion, a sample of n = 1,243, aged 14–21 years ( M = 16.92, SD = 1.75, 67.23% women), remained for subsequent data analyses. All data and further materials are available via osf ( https://osf.io/xc6d4/?view_only=5b913c97553d48a290b75a3f725aca3d ).

Sample Attrition

Numerous email accounts were invalid at the second measurement point—for example, because students' personalized school email accounts were deleted following their graduation or because certain institutions used only a single email account to offer vocational counseling to college students ( N = 3,495). Those who did not participate at the second measurement point (dropouts) were slightly younger than those who participated (continuers) [ M (ageD) = 17.39; M (ageC) = 17.76; p ≤ 0.000, d = −0.12] and more women filled in the second questionnaire (dropouts = 50.9% women, continuers = 64.8% women; p ≤ 0.000, d = 0.31). Only modest selectivity effects (measured by Cohen's d ) in terms of mean differences in personality traits between dropouts and continuers were found at T1; thus, there was negligible systematic attrition ( Specht et al., 2011 ; Pusch et al., 2018 ). Continuers had slightly higher scores in agreeableness ( d = 0.17), conscientiousness ( d = 0.19), and openness ( d = 0.16) than dropouts, but they almost identical in terms of extraversion ( d = −0.08) and emotional stability ( d = 0.01).

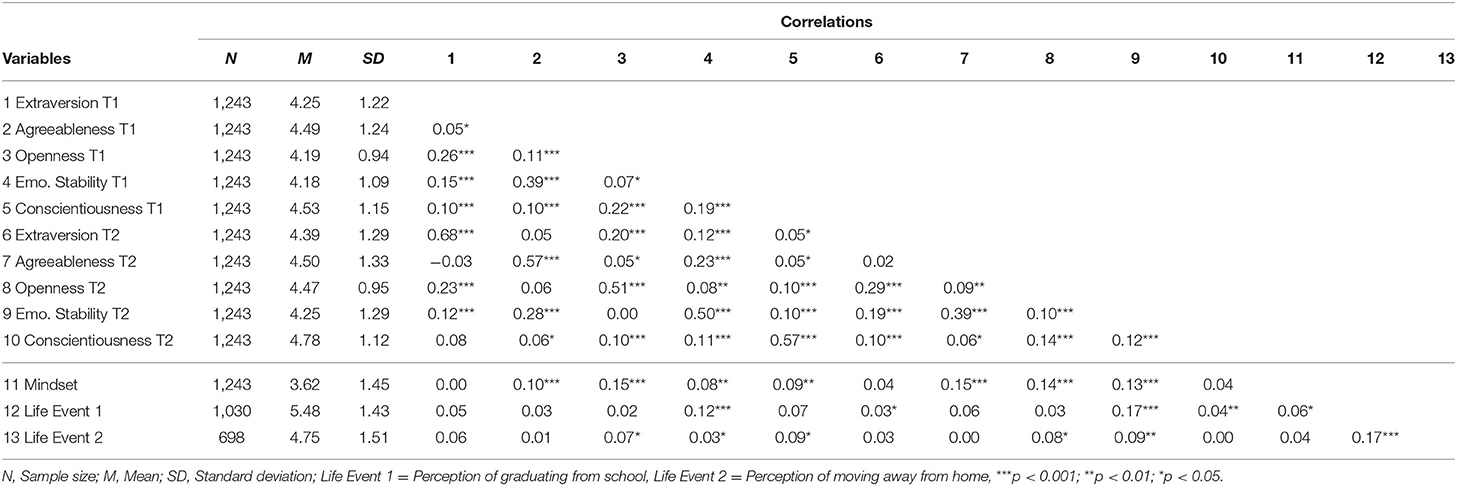

Personality

Personality traits were assessed on both measurement occasions using a short version of the Big Five personality inventory for the vocational context (TAKE5; S&F Personalpsychologie Managementberatung GmbH, 2005 ). The TAKE5 has been shown to be a highly reliable and valid personality measure ( Mussel, 2012 ). In the short version of the test, each of the Big Five subscales (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability) consists of three items and was measured on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 7 ( strongly agree ). Example items for conscientiousness include (translated from German): “Nothing can stop me from completing an important task,” “People around me know me as a perfectionist,” and “My work is always carried out the highest quality standards.” Items were selected to cover the different aspects of each domain therefore internal consistencies provide no valuable indicator. Test-retest reliabilities for the TAKE5 between T1 and T2 were 0.69 for extraversion, 0.52 for openness to experience, 0.57 for conscientiousness, 0.58 for agreeableness, and 0.50 for emotional stability. Small to moderate reliability levels can be explained by the heterogeneity of the items and our attempt to capture rather broad personality constructs. Similar results have been reported for other brief personality scales ( Donnellan et al., 2006 ; Rammstedt et al., 2016 ). All descriptive statistics and correlations can be found in Table 1 , and bivariate correlations of all items can be found at osf ( https://osf.io/xc6d4/?view_only=5b913c97553d48a290b75a3f725aca3d ).

Table 1 . Correlations and descriptive statistics among variables.

Life Events

In the present study, we focus on two major life events that are highly characteristic of the critical period between the late teens and young adulthood ( Arnett, 2000 ; Lüdtke et al., 2011 ; Bleidorn, 2012 ): moving away from home and graduating from school. At T2, after completing the personality questionnaire, participants rated their subjective perception of each of the two life events on a dimensional 7-point Likert scale (1 = very negatively , 7 = very positively ). Of the initial sample, 68.38% of the participants had graduated from school, 47.66% had moved away from home, and 46.96% had experienced both life events. Participants who had graduated from school were older ( M = 17.32 years, SD = 1.84, female = 68.80%) compared to those who had not yet finished school ( M = 15.30 years, SD = 1.09, female = 68.21%). Those who had moved away from home were approximately 1 year older ( M = 17.53, SD = 1.89, female = 69.30%) compared to those did not yet moved away ( M = 16.29, SD =1.69, female = 66.91%). To avoid potential confounding effects, we only asked about events that had happened within the past year (after the first measurement occasion). This allowed us to account for experiences that took place before T1.

In the second step, in order to obtain a fuller picture, participants also had the option of rating an additional significant life event from a list of 18 potential life events from various domains—such as love and health—based on the Munich Life Event List (MEL; Maier-Diewald et al., 1983 ). However, the number of individuals who experienced these other life events was too small to allow for further analyses.

Participants' mindset was measured with a questionnaire based on Dweck's Mindset Instrument (DMI). The 16-item DMI was developed and created by Dweck (1999) and is used examine how students view their own personality and intelligence. In the current study, only items concerning beliefs about the malleability of personality were used. The mindset inventory items were “Personality traits are something a person cannot change,” “You have a certain personality and you really can't do much to change it,” and “You can learn new things, but you can't really change your basic personality.” At T2, participants were presented a 7-point response scale, ranging from 1 ( strongly disagree ) to 7 ( strongly agree ) ( M = 3.60, SD = 1.45). Items were reversed such that higher levels indicated a growth mindset. This short inventory was found to be highly reliable ( M = 3.60, SD = 1.45, ω = 0.81, 95% CI [0.70, 0.84]).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were carried out in four steps. First, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses to test for measurement invariance across time points T1 and T2. Second, we constructed latent difference score models for all Big Five scales to test for mean differences in personality traits. Third, we investigated the impact of the life events moving away from home and graduating from school, as well as the perception of these two events on changes in the Big Five. Fourth, we added mindset as a moderator to the model. All statistical analyses were carried out in R and R Studio 1.2.1335 ( R Core Team, 2018 ).

Measurement invariance

To ensure that the same construct was being measured across time, we first tested for measurement invariance. For weak measurement invariance, we fixed the factor loadings for each indicator to be equal across measurement occasions and compared this model to the configural model, where no restrictions were applied. The same procedure was followed to assess strong measurement invariance, with the weak invariant model compared to a model with constrained intercepts to equality across time (e.g., the same intercept for Item 2 at T1 and Item 2 at T2) ( Newsom, 2015 ). To evaluate the model fit, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were inspected. Good fit was considered to be indicated when CFI and TLI values were 0.90 or higher, RMSEA below 0.08, and SRMR values below 0.05 ( Hu and Bentler, 1999 ; Marsh et al., 2005 ). The configural model showed good fit for all of the Big Five traits (All χ 2 [4 24], df = 5, CFI > [0.98 1.00], TLI > [0.94 1.00], RMSEA < [0.0 0.06], SRMR < [0.0 0.02]). Model fit for partial strong measurement invariance revealed similar fit (all χ 2 [9 50], df = 8, CFI > [0.96 1.00], TLI > [0.92 1.00], RMSEA < [0.01 0.07], SRMR < [0.01 0.03]) when freely estimating the intercept of the first manifest OCEAN item ( Cheung and Rensvold, 2002 ; Little et al., 2007 ). All further analyses are based on this model and full results for fit indices are presented in Table S1 .

Latent Change Score Models

To test for changes in personality over time, we applied latent structural equation modeling analysis with the R package lavaan (version 0.5-23.1097; Rosseel, 2012 ). Required sample size for the specified latent change score model was estimated by the R-toolbox semTools ( MacCallum et al., 2006 ; Jorgensen et al., 2018 ) for RMSEA = 0.05, df = 16, α = 0.05, and a statistical power of 90% to N = 672 individuals. Therefore, we consider our sample size to be sufficiently large.

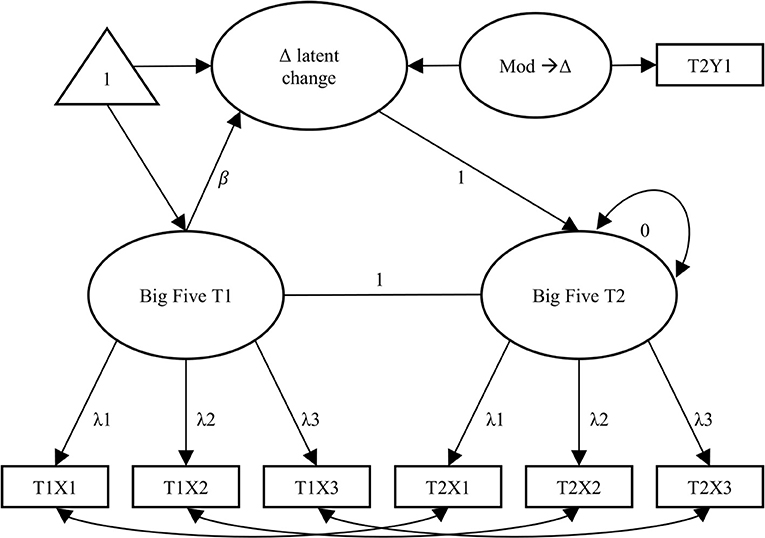

As we were first interested in the rate of change, we built a multiple-indicator univariate latent change score model for each of the Big Five domains ( Figure 1 ). Each latent construct of interest (OCEAN) consisted of three observed measures (X1, X2, and X3) at two waves. Equality constraints were imposed on factor loadings and intercepts ( Newsom, 2015 ). Moreover, the autoregressive path was set equal to 1. The means, intercepts, and covariances at the first occasion and for the difference score factor were freely estimated, and all measurement residuals were allowed to correlate among the sets of repeated measurements ( McArdle et al., 2002 ). We accounted for missing data by applying robust maximum likelihood estimation. Finally, after specifying this basic model, the variables of interest—the occurrence of the life event, perception of the life event, and the moderator mindset—were added to the model.

Figure 1 . Schematic model of the multiple-indicator univariate latent change score model. The latent construct of interest (each personality trait) was measured at two time points (T1 and T2), using three indicators each time (X1, X2, X3). The lower part of the model constitutes the assessment of measurement invariance. “Δ latent change” captures change from the Big Five trait from T1 to T2. Latent regressions from “Δ latent change” on Mod→ Δ reflect the influence of the covariate perception of life event or the moderator mindset on the development of the Big Five. Straight arrows depict loadings and regression coefficients, curved arrows co-variances.

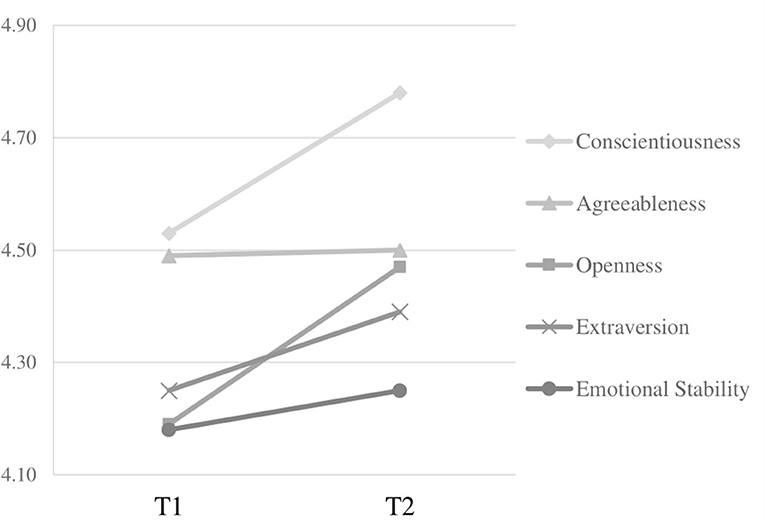

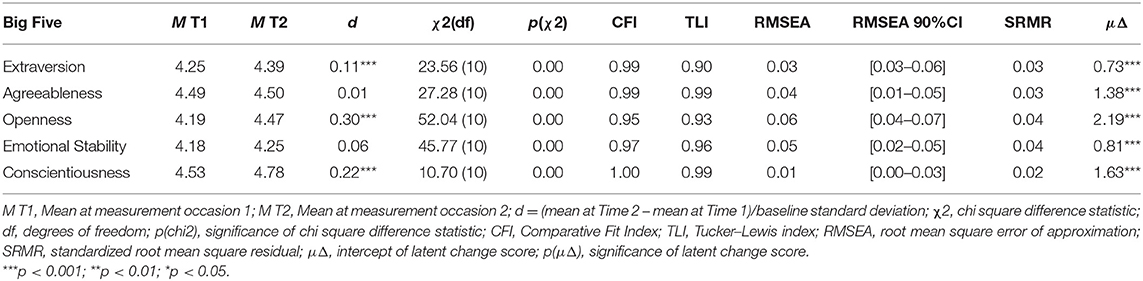

Standardized mean differences were calculated as an average of all intra-individual increases and decreases in a given personality trait over time. As illustrated in Figure 2 , all latent mean scores for the Big Five increased from T1 to T2. Conscientiousness and openness to experience exhibited the largest mean-level changes from T1 to T2, whereas agreeableness ( d = 0.02) and emotional stability ( d = 0.07) remained nearly the same. To test for changes in personality, we employed a multiple-indicator univariate latent change score model. Separate models for each of the Big Five all fit the data well (all CFI > 0.95, TLI > 0.93, RMSEA < 0.05, SRMR < 0.04). Inspecting the intercepts of the change factors revealed that all Big Five scores changed between T1 and T2, with less increase among individuals with high compared to low levels at T1. The latent means for each personality dimension at each time point, along with their fit indices, are reported in Table 2 .

Figure 2 . Mean-level changes in Big Five dimensions over measurement occasions T1 and T2.

Table 2 . Big Five mean-level change from T1 to T2 with fit indices, n = 1,243.

Life Events and Perception of Life Events

To assess personality trait change resulting from experiencing a life event, we included a standardized dichotomized variable “experiencing the life event vs. not” into the model. Again, the model fit the data well for both critical life events (all CFI > 0.94, TLI > 0.92, RMSEA < 0.05, SRMR < 0.04). However, comparing participants who had experienced one of the critical life events (moving away from home or graduating from school) to those who had not revealed that neither life event had a significant impact on changes in personality traits between T1 and T2 ( p >0.05).

To assess personality trait change resulting from perception of a life event, we included the standardized variable “perception of the life event” for each of the two events into the model and regressed the latent change score on the covariate. This time, results regarding the subjective perception of the life event graduating from school indicated a significant impact on personality change for emotional stability (χ 2 [16] = 94.07, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, λ = 0.05, p [λ] < 0.05). Specifically, participants who had experienced graduating from school more negatively exhibited a diminished increase in emotional stability than compared to individuals who had experienced graduating from school more positively. We also found evidence that subjective perceptions are relevant for extraversion. A greater positive change in extraversion was observed when participants experienced graduating from school more positively than compared to negatively (χ 2 [16] = 23.90, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02, SRMR = 0.03, λ = 0.10, p [λ] = 0.05). Subjective perceptions moving away from home had no impact on trait changes in any of the Big Five traits. Descriptive statistics for the life events along with model fit indices can be found in Table S2 .

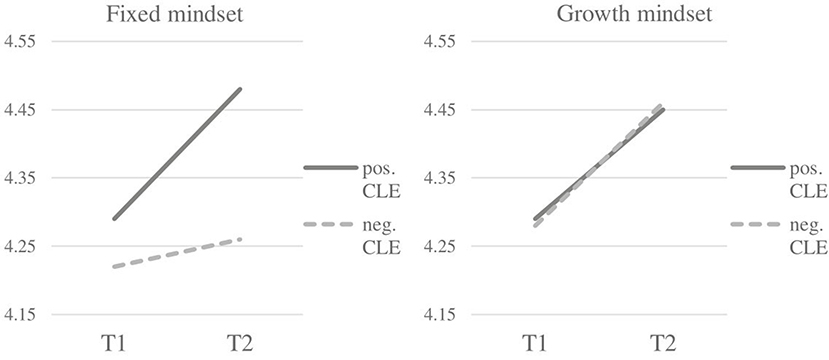

To test for a moderating role of mindset, an interaction term between mindset and each of the two critical life events was constructed. First, we built an interaction term between mindset and the dichotomous variable “experienced the life event” and regressed the latent change factor on the interaction term. Separate models for each of the Big Five all fit the data well (all CFI > 0.94, TLI > 0.92, RMSEA < 0.05, SRMR < 0.05). As shown in Table S3 , no effects for the Big Five traits were significant for the distinction between experienced the life event vs. did not experience the life event ( p > 0.05). Second, for each of the two life events an interaction term between mindset and perception of the life event was built analogously. For extraversion, we found a significant influence of the moderator when assessing the perception of graduating from school (χ 2 [16] = 25.62, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03, SRMR = 0.03, λ = −0.09, p [λ] = 0.05). Hence, a fixed mindset indicates less change in extraversion when experiencing the critical life event graduation from school. More specifically, regarding manifest means of extraversion, participants with a growth mindset experienced almost the same amount of increase in extraversion over time, regardless of their perception (positive or negative) of the critical life event. On the other hand, participants with a fixed mindset only show an increase in extraversion when they experienced the life event more positively (see Figure 3 ). No effects for the interaction between mindset and the critical life event moving away from home were significant.

Figure 3 . Change in trait extraversion for people with a fixed vs. growth mindset with regard to the perception of life event graduation from school .

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the effect of external sources such as life events and internal dispositions like the mindset on personality trait change. We assert that exploring whether the subjective experience of life events is associated with personality trait development constitutes an important future directions in various domains of personality research. Therefore, we took a closer look at the underlying processes, particularly as they relate to individual differences in situational perceptions and belief systems. We investigated how two critical life events (moving away from home and graduating from school) influence personality trait change, the role of subjective perceptions of these events, and how internal belief systems like mindset moderate the impact of life events on trait change.

Mean-Level Change

Since our sample was selected to be between 14 and 21 years of age, most of our participants were classified as emerging adults Arnett, 2000 , 2007 . A large body of research has consistently demonstrated that emerging adulthood is characterized by trait changes related to maturity processes (for an overview, see Roberts et al., 2006 ). Thus, emerging adults tend to experience increases in conscientiousness, emotional stability, openness, and (to a lesser degree) agreeableness. This pattern is often called the “maturity principle” of personality development, and it has been found to hold true cross-culturally ( Roberts and Jackson, 2008 ; Bleidorn, 2015 ). Although the effects were small, we found evidence for mean-level changes in line with the maturity principle and functional personality trait development. Extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability significantly increased over the 1-year period. The largest changes were found for openness and conscientiousness. These changes are most likely to be explained by attempts to satisfy mature expectations and engage in role-congruent behavior. While increases in openness might be due to identity exploration, higher scores on conscientiousness could reflect investment in age-related roles. Individuals might, for instance, take increased responsibility for social or career-related tasks that require more mature functioning ( Arnett, 2000 , 2007 ).

First, we analyzed whether the occurrence of a life event per se had an influence on personality trait change. In our study, neither of the critical life events?moving away from home or graduating from school?affected Big Five trait change over the two measurement occasions. One possible explanation is that the two chosen life events were not prominent enough to evoke far-reaching changes in personality traits ( Magnus et al., 1993 ; Löckenhoff et al., 2009 ). In line with a study by Löckenhoff et al. (2009 ), more stressful, adverse events might have triggered more pronounced and predictable effects on personality traits. Moreover, the period between the late teens and early adulthood is characterized by a large number of stressful events and daily hassles ( Arnett, 2000 , 2007 ). In a comprehensive review of emerging adulthood by Bleidorn and Schwaba (2017) , graduates also experienced changes in other personality traits, such as openness and emotional stability, which suggests that many developmental tasks and major life transitions contribute to changes in Big Five trait domains. Furthermore, according to Luhmann et al. (2014) and Yeager et al. (2019) , life events may not only independently influence the development of personality characteristics, they might also interact with one another. Researchers must address the interpretation of other challenges that adolescents experience. This notion is also supported in a study by Wagner et al. (2020) , who introduced a model that integrates factors that are both personal (e.g., genetic expressions) and environmental (e.g., culture and society). The authors assert that the interactions and transactions of multiple sources are responsible for shaping individuals' personalities, and, in order to understand how they interact and develop over time, more integrated research is needed. Future studies should focus on a wider range of important life events and environmental influences during emerging adulthood and account for possible accumulating effects.

Second, and perhaps most remarkably, our findings revealed a different picture after we analyzed how the two critical life events were perceived. When participants experienced graduating from school negatively, a greater decrease in emotional stability was observed. Conversely, when the event was evaluated positively, a greater positive change in extraversion was reported. There are clear theoretical links between these two traits and the perception of life events in terms of emotional valence. While low emotional stability encompasses a disposition to experience negative emotions such as fear, shame, embarrassment, or sadness (especially in stressful situations), extraverted individuals are characterized by attributes such as cheerfulness, happiness, and serenity ( Goldberg, 1990 ; Depue and Collins, 1999 ). In line with the notion of a bottom-up process of personality development ( Roberts et al., 2005 ), experiencing a major life event as either positive or negative might lead to a prolonged experience of these emotions and, thus, ultimately to altered levels of the corresponding personality traits. These findings are in line with previous research on subjective well-being (SWB). In fact, variance in SWB can be explained by emotional stability and extraversion, indicating a robust negative relationship between low emotional stability and SWB and a positive relationship between extraversion and SWB ( Costa and McCrae, 1980 ; Headey and Wearing, 1989 ). Moreover, Magnus et al. (1993) found selection effects for these traits, suggesting that high scorers in extraversion experience more subjectively positive events, and low scorers in emotional stability experience many (subjectively) negative events (see also Headey and Wearing, 1989 ).

In the present study, we found evidence of a moderating influence of mindset on the impact of the life event graduating from school for the trait extraversion. Our results indicate that people with a growth mindset show greater change in extraversion, almost regardless of whether they experienced the life event more negatively or more positively. On the other hand, the present results indicate that people with a fixed mindset show an increase in extraversion after experiencing a life event more positively, but almost no change in extraversion when experiencing graduating from school negatively.

Interestingly, we only found effects for extraversion. As previously mentioned, trait extraversion stands for behavioral attributes such as how outgoing and social a person is, and this is related to differences in perceived positive affect ( Goldberg, 1990 ; Magnus et al., 1993 ; Roberts et al., 2005 ). The characteristics of extraversion can be linked to the assumption that people with a growth mindset show greater resilience ( Schroder et al., 2017 ; Yeager et al., 2019 ), especially in the face of academic and social challenges ( Yeager and Dweck, 2012 ). Thus, people who believe that their internal attributes are malleable confront challenges such as graduation by adapting and learning from them; our findings suggest that this results in an increase in extraversion. By contrast, people who believe that they cannot change their personality characteristics might attribute a negatively experienced graduation to external circumstances out of their control. Thus, they do not rise from a negative life event and experience no impetus to become more extraverted.

The above notwithstanding, more research is needed, as we found no evidence for the other Big Five personality traits. Further, the relationship between mindset and personality is complex to disentangle. We examined only two major life events in this first attempt. More attention is needed with respect to other life events and their interplay with internal belief systems and implicit theories to explore possible far-reaching effects on behavior.