Religion Online

Chapter 5: The Sacred Literature of Hinduism

The scriptures of mankind: an introduction by charles samuel braden.

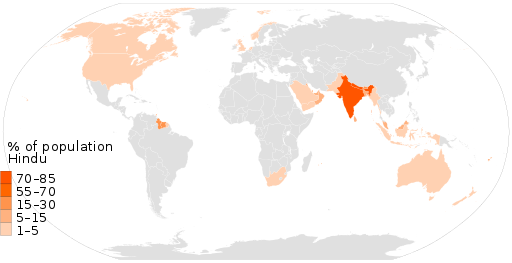

"Mother" India, as she is lovingly called by her sons, has indeed been a mother of religions. Four of the eleven principal living faiths of the world were born in India: Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism, and all have extensive sacred literatures. Hinduism itself, from which all the others have sprung, has a vast and highly variegated set of scriptures. In general there are two types of scripture that are regarded as authoritative in Hinduism: (1) sruti: that which may be regarded as the ipsissima verba, the very, very word of God. It was given by verbal inspiration to the rishiis or seers, and gathered into a closed Canon. From this nothing may be taken away and nothing may be added. This type of sacred writing has, in the course of time, come to be thought of very much as the Bible is thought of by Christian Fundamentalists: as infallible, incapable of error, because of its non-human character.

The second type of scripture is known as smriti. While admittedly of human origins, it has come to be thought of as authoritative also, in the expression of religious faith, and of very high value in the teaching of religion and morals. Though of less exalted origin, and not of equal value with sruti, as a basis of religious dogma, it is perhaps quite as influential in the lives of the people in inculcating and nourishing religious faith and practice. If all the books which are comprised within these two classes of sacred literature were to be brought together in a single collection, as has nowhere yet been done, they would fill many thousands of pages. While there is rather general agreement as to what may be considered as smriti, there is no closed canon. Sectarian groups differ to a considerable degree as to what may be so considered. Certainly they differ as to which particular books of this category are to be emphasized within their own groups. The rather generally tolerant attitude of Indians toward the religious beliefs of others inclines them to admit as sacred for others what they might not accept for themselves. As a matter of fact some sectarian groups make, practically, much greater use of non-sruti literature, as the basis for present belief and practice than they do of the recognized sruti writings. Indeed for them some books generally regarded as smriti have actually become sruti. There is nothing in Hinduism to prevent this from happening.

Within Hindu sacred literature may be found, as in most scripture, almost every type of writing. There is both poetry and prose. Examples of nearly every variety of poetic expression may be found. Some of it is lyric, some elegiac, some epic, some dramatic. Love songs abound. There is poetry of praise, poetry of lamentation, heroic verse, and poetry of despair, poetry of thanksgiving, poetry of devotion, poetry that is light, airy, fanciful, and poetry that seeks to express the most profound philosophic insight. Of prose there is every kind, the short story, the drama, the fable, legal lore, philosophic essays, history, drama. Only the epistolary, which is so important in the New Testament, seems to be lacking. There are prose passages of unusual beauty and strength; there are innumerable pages of dry dialectic material, without grace or charm, but none the less important for an understanding of Hinduism.

This Hindu literature like that of most other religions represents the work of many, many hands over a long period of time. It records the hopes, aspirations, ideals, triumphs, failures, strivings after meaning of a great people, across the centuries, as they developed from barbarism to the highly cultured society which is India today at its best. Out of the struggle upward the literature was born and by it India’s life has been shaped and controlled to a remarkable degree, for India’s sacred literature is no mere museum piece. The daily routine of the orthodox Hindu is probably much more determined by some part of his scriptures than that of the people of the West by the Bible, or for that matter than that of any other people by its scripture, save only the Moslems.

India’s sacred literature divides itself logically and to some extent chronologically, into four main groups: (1) Vedic literature, (2) Legal literature, (3) Epic literature and (4) Puranic literature. The exact chronology of some writings it is difficult to fix, and there is often a difference in time between the beginnings of a given body of literature and its final completion. The beginnings of the Epics may well have been within the late Vedic age, their completion more than a millennium later. The earliest formulation of legal codes may go well back into the past; the final fixing of the codes is comparatively late, and of course some codes are much earlier than others. Some of the Puranic lore is old. The Puranas, as now found, are the latest of all Hindu sacred writings. We consider first Vedic literature.

Vedic Literature

Vedic literature is sruti, the infallible, verbally inspired word of God. It is the most sacred of all. So sacred was it held to be at the time of the making of the Code of Manu, greatest of the law books, that it was therein decreed that a lowly Sudra, i.e., low caste man, who so much as listened to the sacred text would have molten metal poured into his ears, and his tongue cut out if he pronounced the sacred words of the holy Vedas. 1 ‘Whether such laws were ever actually enforced may be doubted. Certainly there is no evidence that they were, but they do serve to accentuate the degree of sacredness which attached to the Vedic literature.

Vedic literature comprises much more than the Vedas. These give their name to an extensive literature which grew out of them. Specifically regarded as part of the Veda are (1) the Brahmanas, (2) the Aranyakas, and (3) the Upanishads. It has become a dogma generally accepted that all that is found in these later writings is simply an outgrowth of the Vedas, the making explicit of what was therein implicit. They are therefore regarded as equally sacred. There is another reason -- perhaps the primary reason -- for considering them as Vedic, namely, that these writings, except the Vedanta Sutras, were physically attached to the Vedas in their written form.

Most basic of all Hindu sacred writings are the Samhitas, generally called the Vedas themselves, of which there are four, and most basic of the four is the Rig-Veda. The others, the Sama-Veda, the Yajur-Veda and the Atharva-Veda, all derive to a considerable extent from the Rig. Most of our attention will therefore be given to this highly important sacred book.

The name of the book, Rig-Veda, means probably "Verse Wisdom." It is a collection of hymns, 1017 in all according to Griffith. In bulk it is longer than the combined Iliad and Odyssey of Homer. Translated into English, and with some notes, the hymns make two quite substantial volumes. 2 In the original there are some 20,000 metrical verses in the whole collection.

For the Rig-Veda is just that, a collection, the work of a great many writers, or in some cases, guilds of writers. It consists chiefly of hymns to one or another of the numerous Vedic gods, designed for use in the worship of these divinities. It represents the oldest stratum of Hinduism of which very much is known. In recent times archaeological discoveries in the Indus valley have brought to light evidences of a highly developed culture in India long before the coming of the invading Aryans. Whereas, earlier, it had been believed that the Aryans found only peoples of relatively undeveloped culture, now it is known that at least some of these early Indians had developed the arts to a high degree, that they even had a kind of hieroglyphic writing, not yet deciphered, and probably an equally well developed religion which, suppressed for a time, gradually reasserted itself and greatly modified Vedic religion, gradually transforming it into the Hinduism as practiced in India today. (For an interesting account of this civilization see Sir John Marshall, Mohenjo-daro, 3 volumes.)

Reference has been made to the Aryan invasion of India. Who were the Aryans? There is much that is not known concerning them, but it is known that long, long before they arrived in India they were part of a great migratory movement of people, sometimes identified incorrectly as a race, probably better as a people of a common culture. To this people, eventually, the name Indo-European came to be attached, since sure signs of their presence are to be found all the way from the British Isles on the West, to the Bay of Bengal on the East, and from the Scandinavian countries on the North to the Mediterranean on the South. Though possessing many common cultural traits found also in Europe and the West, the much closer similarities between the cultures of Iran or Persia and India have led scholars to distinguish an Indo-Iranian branch of the larger whole as having early separated itself from the central or original Aryan migration, perhaps moving eastward from the, as yet, not certainly located origin of the Aryan group. Later this segment again separated into two branches. One of these entered the Iranian plateau, amalgamated with the native populations and eventually gave rise to a new faith, Zoroastrianism, which developed its own sacred literature. The other crossed the Khyber pass and entered the land of India, gradually fanning out to cover the greater part of that vast subcontinent, but losing, in the course of its southern movement, much of its original character.

It was of this Aryan migration that the Vedic hymns were born. In a real sense they, at least the older of them, are not really Indian in origin at all, but were produced either before the Aryans had set foot on Indian soil, or were composed by Aryans, i.e., the foreign invaders, before India had had time to put her own impress upon them. When this invasion took place it is impossible to state with any certainty. It is rather generally supposed to have occurred some time within the period 2500-1500 B.C., though some Indian scholars put it at a much earlier date, even as early as 5000 B.C.

In modern times the term Aryan has become a racial term, as in Germany under the Nazis, when a sharp distinction was made between the Aryan and the Semitic elements in the population. But beyond the probable fact that the Aryan invaders were light rather than dark of skin, little can be alleged as to their racial character. This is evidenced by the lighter complexions of the present-day Indian in the northern parts of India where the Aryans mingled in largest proportion with the indigenous population, in contrast to the much darker complexion of southern Indians where the Aryan influence is least. Also it is an easily recognized fact that modern-day Indians, particularly of the northern half, or more, appear to have European features despite their darker color. Modern anthropologists and ethnologists give no support to the existence, now or at any time, of a pure Aryan race. They do attest to an Aryan culture widely spread over most of Europe, Persia and India, on the basis of evidences drawn from language, the archaeological discovery of artifacts and objects of art, and certain similarities of religious ideas to be found in the areas overrun by these far-ranging migrants.

Whatever the nature of the Aryans, it is a proudly held word in contemporary India. One vigorous modern reform movement in Hinduism which seeks to recapture the best of India’s religious heritage calls itself the Arya-Samaj, the Society of Aryans; another publishes a religious journal which it calls The Aryan Path. To behave as a true Aryan comes to have something of the meaning of the Confucian term, "the Superior Man," or the old English phrase of "the true gentleman."

The hymns of the Rig-Veda are much older, of course, than the collection itself. Most of them were composed for use in the cult, although there are hymns which seem to be the more or less spontaneous expression of the individual human spirit. At first this cult, or worship was conducted by the father of the household, but in time there arose a specialized priesthood for the performance of the appropriate sacrifices and rituals, and the hymns were probably largely produced by them and for their use in the cult. Not many hymns can be assigned to specific authors, though the Rig-Veda contains seven groups of hymns attributed to seven families, the Gritsamada, Visvamitra, Vamadeva, Atri, Bharadvaja, Vasistha, and Kanva. These may represent separate schools of poetry -- the hymns in any one group are certainly not all by the same individual. The collection was not made all at one time, as seems evident also in the Hebrew book of Psalms.

There are ten books in all. Of these, Books II through VII contain the greater number of the oldest hymns and were the first to be brought together, possibly at the command of some famous chief. Here a uniform arrangement appears. Hymns are grouped by families and within each family group they are arranged according to the gods to whom the hymns are addressed; and within these groups according to the number of stanzas, in descending order. Conjecturally, there were then collected and added what is now the second half of Book I, then the first half of Book I and Book VIII, then Book IX which is dedicated entirely to the god Soma, the intoxicant deity, and, finally, the latest of all the books, the tenth and last. Book IX, while collected later than most of the others, contains hymns which may well be as old as any.

From these hymns can be discovered much concerning the life and thought of the ancient Vedic Indians. It is a rare source book for the study of their culture. Here are disclosed not only their religious ideas, their deepest longings, their sins and failures, their ideas of good and evil, their hopes and fears; but also how they worked, how they played, how they fought, what they ate, how they dressed, the pattern of their domestic and public life. Indeed, all we can know about this people is here preserved, for they left no monuments, or buildings, or inscriptions from which the archaeologist might recapture their ancient civilization. It is not only the sacred literature of the period, it is the only literature that has been preserved, and it was preserved only because it became sacred.

From the older hymns it is clear that they were still an invading, conquering people, dependent upon military skill and power to make their way ever more deeply into India. Proof of this is the prominent place given to Indra who was their god of war. Much can be inferred as to the character and activity of people from the gods who hold positions of principal importance. In war times there has always been, and still is, a need for a god of battles to spur men on to fight. In modern times when men believe in but one god, his militant character always comes to the front in war time, and his more pacific character is played down. Nearly one-fourth of all the hymns of the Rig-Veda are to Indra. Of course he is more than a war god; he is also god of storm, beneficent, life-bringing storm, which makes grass to grow. The ruder, more destructive aspects of storm are assigned to Rudra, father of the Maruts, who are often associated with Indra in his hymns.

The Vedic people are still pastoral to a large degree. Cultivation of the soil has not yet become a primary source of their living. It is a cattle culture, as only a very cursory glance at the hymns will quickly disclose. Their prayers -- to Indra, and to others as well -- are largely for rich pasturage, great herds of cattle, long life, big families, and of course success in battle. Rain is a necessity if pastures are to be green. Indra is the slayer of the demon Vritra who herds the cloud cows into a cave and prevents the rains from coming. Prayers rise to Indra. He prepares himself by consuming ponds of Soma, the intoxicant, then sallies forth to slay the monster Vritra. This is all recalled in one of the hymns.

1. Let me tell out the manly deeds of Indra, Which he accomplished first of all, bolt-weaponed: He slew the serpent, opened up the waters, And cleft in twain the belly of the mountains.

3. With bull-like eagerness he sought the soma; Out of three vats he drank the pressed out liquor; Maghavan took in hand his bolt, the missile, And smote therewith the first-born of the serpents.

6. For, like a drunken weakling, Vritra challenged The mighty hero, the impetuous warrior; He did not meet the clash of Indra’s weapons, Broken and crushed he lay, whose foe was Indra.

13. Lightning and thunder profited him nothing, Nor mist nor hailstorm which he spread around him; When Indra and the serpent fought their battle, Maghavan won the victory forever.

15. Indra is king of that which moves and moves not, Of tame and horned creatures, too, bolt weaponed; Over the tribes of men he rules as monarch; As felly spokes, so holds he them together. 3

Indra’s close relationship to the preservation of cattle -- and therefore to wealth and prosperity of the people -- is seen in this hymn which reflects the naive character of a simple pastoral people:

The Kine have come and brought good fortune: let them rest in the cow-pen and be happy near us. Here let them stay prolific, many colored, and yield through many moms their milk for Indra.

Indra aids him who offers sacrifice and gifts; he takes not what is his, and gives him more thereto. Increasing ever more and ever more his wealth, he makes the pious dwell within unbroken bounds.

These are ne’er lost, no robber ever injures them: evil- minded foe attempts to harass them. The master of the Kine lives many a year with these, the Cows whereby he pours his gifts and serves the Gods. 4

But Indra also comes to be thought of at times as more than just a fertility and war god. In one of the hymns he assumes almost the character of a monotheistic creator god. If no other hymn of the whole collection had been preserved it would be easy to assume that Indra had indeed become the one god of the world. This is but an example of the habit of Vedic people to elevate momentarily first one divinity, then another to supremacy. To describe this attitude, Max Muller proposed a new synthetic word, henotheism. Here is a part of a hymn too long to quote entire:

1. He who as soon as born keen-thoughted, foremost, Surpassed the gods, himself, a god, in power; Before whose vehemence the worlds trembled Through his great valour; he, O men, is Indra.

2. He who the quivering earth hath firm established, And set at rest the agitated mountains; Who measured out the mid-air far-extending, And sky supported: he, O men, is Indra.

3. Who slew the snake and freed the seven rivers, Drove out the cattle by unclosing Vala; Who fire between two rocks hath generated, In battles victor: he, O men, is Indra.

13. Even the heavens and earth bow down before him, And at his vehemence the mountains tremble; Who, bolt in arm, is known as Soma-drinker, With hands bolt-wielding; he, O men, is Indra. 5

Fire plays an important role in the life of any people, and is coimmonly worshiped throughout the world. In Vedic India this element whether as in the hearthfire, in the lightning stroke, or in the blazing sun was an object of constant worship as Agni. 6 It is not easy in many of the hymns to say whether the object of cult is the fire itself or a god behind it; perhaps they themselves were not always sure either. Fire is a servant, fire is a friend, it is a purifier, a cleanser, and perhaps most important of all, it is that which transmutes the sacrifice into a holy food for the gods. Easily Agni becomes a mediator or priest god. One of the many hymns reads thus:

Agni, be kind to us when we approach thee, good as a friend to friend, as sire and mother. The races of mankind are great oppressors: burn up malignity that strives against us. Agni, burn up the unfriendly who are near us, burn thou the foeman’s curse who pays no worship. Burn, Vasu, thou who markest well, the foolish: Let thine eternal nimble beams surround thee. With fuel, Agni, and with oil, desirous, mine offering I pre-sent for strength and conquest, With prayer, so far as I have power, adoring -- This hymn divine to gain a hundred treasures. Give with thy glow, thou Son of Strength when lauded, great vital power to those who toil to serve thee. Give richly, Agni, to the Visvamitras in rest and stir. Oft have we decked thy body. Give us, O liberal Lord, great store of riches, for, Agni, such art thou when duly kindled. Thou in the happy singer’s home bestowest, amply with arms extended, things of beauty. 7

The entire ninth book consists of hymns to Soma. Soma is sometimes the plant, from which juice is extracted to become, when properly strained and mixed, Soma, the intoxicant, the food of the gods, the elixir of immortality, and finally Soma is one of the chief Vedic divinities. Nowhere in literature has the intoxicant been more lyrically described and exalted than in this ninth book. The writers never tire of describing the process of preparation of the divine drink. Every literary art is laid under tribute to glorify it. The press, the filter, or straining cloth, the utensils which contain it are described in loving detail. Soma is the drink of the gods. All seem to be entitled to a libation at intervals, and their standing within the pantheon can be pretty well determined by the amount and frequency of the offering of Soma to the different divinities. Indra more than all of them loves it. Three times each day he must have his meed of Soma, and for his major exploits in man’s behalf he quaffs unbelievable quantities of it, not measured by cups but by vats or ponds or lakes. To none of the intoxicant gods in the religions of the world have greater virtues or powers been attributed. Space limits permit only a few illustrations:

1. Sent forth by men, this mighty steed, Lord of the mind, who knoweth all, Runs to the woolen straining-cloth.

2. Within the filter hath he flowed. This Soma for the gods effused, Entering all their various worlds.

3. Resplendent is this deity, Immortal in his dwelling place, Foe-slayer, feaster best of gods.

4. Directed by the sisters ten, Bellowing on his way this bull Runs onward to the wooden vats.

5. This Pavamana made the sun To shine and all his various worlds, Omniscient, present everywhere.

6. This Soma filtering himself, Flows mighty and infallible, Slayer of sinners, feasting gods. 8

Here is a prayer for immortality, addressed appropriately enough to the god who represents, in physical form, the drink of immortality (although the god of the dead and of whatever other-worldly dwelling place awaited them was not Soma but Yama) .

7. Where radiance inexhaustible Dwells, and the light of heaven is set, Place me, clear-flowing one, in that Imperishable and deathless world. (O Indu, flow for Indra’s sake.)

8. Make me immortal in the place Where dwells the king Vaivasvata, Where stands the inmost shrine of heaven, And where the living waters are.

9. Make me immortal in that realm, Wherein is movement glad and free, In the third sky, third heaven of heavens, Where are the lucid worlds of light.

10. Make me immortal in the place Where loves and longings are fulfilled, The region of the ruddy (sphere) , Where food and satisfaction reign.

11. Make me immortal in the place Wherein felicity and joy, Pleasure and bliss together dwell, And all desire is satisfied. 9

One more quotation must suffice. A graduate student, reading it, was impressed and, being employed as a youth director in one of the local churches and in charge of a weekly worship service, undertook to modify it at certain points and use it as a litany in the Sunday morning service. It so happened that the pastor of the church visited the group that morning, and, impressed by the beautiful litany, inquired where she had found it. He was not a little surprised to learn that it was out of an ancient book of hymns of a pagan people dedicated to an intoxicant divinity. It reads in part:

O Soma flowing on thy way, win thou and conquer high renown; And make us better than we are. Win thou the light, win heavenly light, and, Soma, all felicities; And make us better than we are. Win skilful strength and mental power, O Soma, drive away our foes; And make us better than we are. Ye purifiers, purify Soma for Indra, for his drink; Make thou us better than we are. Give us our portion in the Sun through thine own mental power and aids; And make us better than we are. Through thine own mental power and aid long may we look upon the Sun: Make thou us better than we are. Well-weaponed Soma, pour to us a stream of riches doubly great; And make us better than we are. As one victorious, unsubdued in battle pour forth wealth to us; And make us better than we are. By worship Pavamana! men have strengthened thee to prop the Law: Make thou us better than we are. O Indu, bring us wealth in steeds, manifold, quickening all life; And make us better than we are. 10

It is in the hymns to the great god Varuna that the Vedas reach their highest point, judged from the standpoint of a Christian culture. Here they come closest in moral and spiritual insight to the Hebrew Psalms and the New Testament. Most of the Vedic religious aspiration moves at the level of the satisfaction of physical needs -- long life, food, shelter, protection, large families -- but in these hymns one finds a consciousness of sin and guilt and the need for forgiveness, as well also as guidance and direction in living.

1. Wise are the generations through the greatness Of him who propped the two wide worlds asunder; Pushed forth the great and lofty vault of heaven, The day-star, too; and spread the earth out broadly.

2. With mine own self I meditate this question: "When shall I have with Varuna communion? What gift of mine will he enjoy unangered? When shall I happy-hearted see his mercy?"

3. Wishing to know my sin I make inquiry, I go about to all the wise and ask them; One and the self-same thing even sages tell me; "Varuna hath with thee hot indignation."

4. O Varuna, what was my chief transgression, That thou wouldst slay a friend who sings thy praises? Tell me, god undeceived and sovereign, guiltless, Would I appease thee then with adoration.

5 . Set us free from the misdeeds of our fathers, From those that we ourselves have perpetrated; Like cattle-thief, O king, like calf rope-fastened, So set thou free Vasistha from the fetter.

6. ‘Twas not mine own will, Varuna, ‘twas delusion, Drink, anger, dice, or lack of thought, that caused it; An older man has led astray a younger, Not even sleep protects a man from evil.

7. O let me like a slave, when once made sinless, Serve him the merciful, erewhile the angry. The noble god has made the thoughtless thoughtful; He speeds the wise to riches, he a wiser.

8. May this my praise-song, Varuna, sovereign ruler, Reach unto thee and make thy heart complaisant; May it be well with us in rest and labour, Do yet protect us evermore with blessings. 11

Or, again in another hymn:

Against a friend, companion, or a brother, A fellow-tribesman, or against a stranger, Whatever trespass we have perpetrated, Do thou, O Varuna, from that release us. If we, like those that play at dice, have cheated, Have really sinned, or done amiss unwitting, Cast all these sins away, as from us loosened; So may we, Varuna, be thine own beloved. 12

One is reminded of Psalm 139 by the following hymn which reveals Varuna as all seeing, even to the inward thought of a man.

7. He knows the path of birds that through The atmosphere do wing their flight, And ocean-dwelling knows the ships.

8. He knows, as one whose law is firm, The twelve months with their progeny, Knows too the month of later birth.

9. He knows the pathway of the wind, The wide, the high, the mighty wind, And those that sit enthroned above.

10. Enthroned within his palace sits God Varuna whose law is firm, All-wise for universal sway.

11. From there the observant god beholds All strange and secret happenings, Things that are done or to be done.

12. Let him the all-wise Aditya Make all our days fair-pathed for us; May he prolong our earthly lives.

13. Wearing a golden mantle, clothed In shining garb, is Varuna; His spies are seated round about.

14. He whom deceivers do not dare Try to deceive, nor injurers To harm, nor th’ hostile to defy. 13

The tenth book is the latest of all, and in it are found at least the beginnings of speculation concerning the nature and origin of the world, which occupies so important a place in the later sacred literature of India. Take, for instance, the hymn to the Unknown God. If at the end the answer is given that it is Prajapati who has created everything, this is thought by many to have been a later addition.

1. The Golden Germ arose in the beginning, Born the sole lord of everything existing; He fixed and holdeth up this earth and heaven,-- Who is the god to worship with oblation?

2. He who gives breath and strength, he whose commandment All beings follow, yea the gods acknowledge; Whose shadow immortality and death is, -- Who is the god to worship with oblation?

3. He who through greatness hath become sole monarch Of all the moving world that breathes and slumbers; Who ruleth over quadrupeds and bipeds, -- Who is the god to worship with oblation?

5. He through whom sky is firm and earth is steady, Through whom sun’s light and heaven’s vault are supported; Who in mid-air is measurer of the spaces, -- Who is the god to worship with oblation?

8. He who in might surveyed the floods containing Creative force, the sacrifice producing; Who ‘mid all gods has been and is alone god,-- Who is the god to worship with oblation?

10. Prajapati, apart from thee no other Hath all these things embraced and comprehended; May that be ours which we desire when off’ring Worship to thee; may we be lords of riches. 14

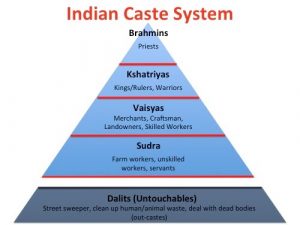

The great hymn of creation which in some sense foreshadows the pantheism of later Hinduism is evidently quite late, for it describes the origins of caste, of which nothing is known in any of the other Vedic hymns. Only a few verses of it can be given here.

1. A thousand heads has Purusa, A thousand eyes, a thousand feet; He holding earth enclosed about, Extends beyond, ten fingers length.

2. Whatever is, is Purusa, Both what has been and what shall be; He ruleth the immortal world, Which he transcends through sacred food.

3. As great as this is Purusa, Yet greater still his greatness is; All creatures are one-fourth of him, Three-fourths th’ immortal in the heaven.

4. Three-fourths ascended up on high, One-fourth came into being here; Thence he developed into what Is animate and inanimate.

6. When gods performed a sacrifice With Purusa as their offering, Spring was its oil and Summer-heat Its fuel, its oblation Fall.

8. From that completely-offered rite Was gathered up the clotted oil; It formed the creatures of the air, And animals both wild and tame.

10. From that were horses born and all The beasts that have two rows of teeth; Cattle were also born from that, And from that spring the goats and sheep.

11. Then they dismembered Purusa; How many portions did they make? What was his mouth called, what his arms, What his two thighs, and what his feet?

12. His mouth became the Brahmana, And his two arms the Ksatriya; His thighs became the Vaisya- class , And from his feet the Sudra sprang.

13. The Moon was gendered from his mind, And from his eye the Sun was born; Indra and Agni from his mouth, And Vayu from his breath was born.

14. Forth from his navel came the air, And from his head evolved the sky; Earth from his feet and from his ear The quarters: thus they framed the worlds. 15

There are hymns to many different gods in the Rig-Veda, almost a fourth of them to Indra alone, and over two hundred to Agni, but to lovely Ushas, goddess of dawn, one of the very few goddesses of any independent character in the whole of Vedic religion, there are only twenty-one. Most goddesses are merely given the feminine form of the name of their more important consorts. Thus Indrani is the wife of Indra. There are hymns to numerous sun gods, Vishnu, Surya, Pusan, Mitra, who later appears in Mithraism as a rival of Christianity in the Mediterranean area; to Rudra, god of destructive storm, to Yama, god of the dead, and many others, from which it would be pleasant to quote if space allowed.

Only about thirty hymns are not concerned with the worship of some one or another of the gods. Two of these have already been cited. There are a dozen magical hymns: I, 191; II, 42, 43; X, 145, 162, 163, 166, 183. Two are riddles. Four are didactic, IX, 112; X, 71, 117, and X, 34. This latter has to do with gambling which was apparently very common in Vedic times, as later we shall find it recurring in the Epic literature.

The date of the completion of the collection of the Rig-Vedic hymns cannot be fixed with certainty. Scholars differ in their conjectures from as early as 1200 -- 1000 B.C. to as late as 800-600 B.C. All are agreed that it took place before the appearance of Buddha in the sixth century. But since also they are agreed that the later Vedic literature is also pre-Buddhist, and that these presuppose the existence of the Rig-Veda and indeed depend upon it, it would seem to this writer that a substantial lapse of time must be allowed for the very considerable development of religious thought to take place. Thus it would seem that a date not far from 1000-800 B.C. would be called for. That there were various rescensions of the original collection is doubtless true. The one which has come down to us is that of the Sakalaka school. The remarkable thing is that it was preserved and transmitted orally for centuries before it was reduced to writing, passed on from teacher to pupil. When the first written edition was made is not certainly known. I-tsing, Chinese traveller in India in the seventh century A.D., states that the Vedas were still transmitted orally. 16 This does not mean necessarily that there were no written copies, but only that dependence for authoritative transmission was not on the written copies which are so very much subject to error, but upon the painstaking oral transmission from teacher to pupil. It is probable that they were not consigned to written form until sometime not far from the beginning of the Christian era.

If this feat of memory seems almost incredible to the modern student, dependent upon his notebook and pen, let him recall that this was the work of specialists whose primary business it was to cultivate their memories, and who had a profound sense of the importance of transmitting, without error, the sacred text. Furthermore special devices were employed to insure that no word or line slipped out of place as so easily happens in copying a written text by hand, or setting it up in type. In general, the schemes were designed so that each separate word was linked with the word or words before and following it, so that it would be almost impossible either to omit anything from the text or add anything to it. Three separate schemes are known to have been employed.

The first was known as the step text, most easily seen if we designate the first word by the letter "a," the second by "b," and so on. The text was then learned thus: ab -- bc -- cd -- de. Employing this scheme in relation to Genesis 1:1 in the Bible it would read: In the, the beginning, beginning God, God created, created the, etc. etc. The next method, called the woven text, was more complex. It ran thus: ab -- ba -- ab; bc -- cb -- bc; cd -- dc -- cd; etc. "In the -- the in -- in the; the beginning --beginning the -- the beginning; etc. etc." One would think that any mistake with this system would be almost impossible, but just to be quite sure, an even more complicated system for learning the text was worked out. It was known as the Ghana-patha, the two previously given, respectively, as Krama-patha and Jata-patha. It reads as follows: ab -- ba -- abc -- cba --abc; bc -- cb -- bcd -- dcb -- bcd; or in Biblical terms: "In the -- the in -- in the beginning -- beginning the in -- in the beginning, etc."

Could error possibly creep in with this arrangement? The chances are that the Vedic text has been much more correctly transmitted than has the text of ancient holy writ of the Hebrew-Christian tradition, which came to us via the copyists and the printers.

The Rig-Veda is by far the most important of the four Vedas, and is to a large extent the source from which much of the content of the others, particularly the Sama-Veda and the Yajur Veda, is derived. Each of these two Samhitas, or collections, as they are called, arose as the cult developed and are of interest chiefly as revealing the nature of the Vedic cult. Both are essentially priestly documents.

As the cult developed it outgrew the simple household ministration of the father, and a priesthood arose. At first a single priest could perform all the rites. Even so, his various functions were given special names. At one time he was the Udgatri, or the singer of hymns, at the Soma-sacrifice. Again, he was the sacrificer, at the animal sacrifice or Hotri, performing himself the manual parts as well as reciting the ritual. As the cult became more complex an assistant was required to take care of the manual part of the sacrifice, leaving the Hotri free to give his whole attention to the reciting of praises. Eventually there were three ranks of priests, the Udgatri, the Hotri, and the Adhvaryu.

It was for the Udgatri that the Sama-Veda or "chant" Veda as it is sometimes called, was formed. All but seventy-five of its more than fifteen hundred verses are taken directly from the Rig-Veda. It is the musical Veda, created for the instruction of the Udgatri priests. The first part of it, the Archika or book of praises, consists of 585 single stanzas each to be sung to a separate tune. In ancient times the tunes were taught orally, but in written editions the music accompanies the words. Winternitz says that this part is like a song-book in which only the first stanza of the song is printed as an aid to the recall of the melody. The songs taken chiefly from the Rig-Veda are arranged according to the deities to which they are dedicated. The second, or Uttararchika, contains 1225 stanzas, usually three to each strophe, arranged according to the order of the principal sacrifices. Winternitz compares it to a songbook in which the words are given, assuming that the melody is already known. 17 Of importance in the study of Indian music, and as throwing light on the Vedic cult, it is of little popular interest, and adds nothing essential concerning Vedic life and belief to what is afforded by the Rig-Veda.

The Yajur-Veda was the Veda of the assisting priest or Adhvaryu, whose duty it was to perform the manual part of the sacrifice. From early times it was customary for the priest, while performing various manual acts of the sacrifice, to utter appropriate formulas. These may have been of the nature of magic or incantations. This became a part of the function of the specialized manual priest, leaving the more formal and public ritual utterances to the Hotri or sacrificing priest. Later to these utterances were added also certain praises and prayers derived from the Rig-Veda. It is this material for the use of the Adhvaryu that constitutes the Yajur-Veda collection. It is found in various versions as taught in differing schools. Some of these versions in addition to the above mentioned formulas have incorporated also a certain amount of theological material or Brahmana directly into the text. These constitute the so-called Black YajurVeda. The other, better known, White Yajur-Veda, has the Brahmana separated out from the formulas and prayers and carries it as an appendix at the end. Brief examples of phrases used by the Adhvaryu are as follows: When a piece of wood with which the sacred fire is to be kindled is dedicated, this formula is recited: "This, Agni, is thy igniter; through it mayst thou grow and thrive. May we also grow and thrive." He addresses the halter by which a sacrificial victim is bound to the stake thus: "Become no snake -- become no viper." To the razor with which the sacrificer’s beard is about to be shaved he says: "O knife, do not injure him." 18

Of the forty sections contained in the Yajur-Veda, the first twenty-five, and earliest, contain the prayers for the most important sacrifices, e.g., the sacrifices of the New and Full Moon, the Soma sacrifices in general, the Building of the Fire Altar, which requires a year, and the great Horse Sacrifice. The remaining fifteen are much later, and are more or less an appendix to the main body of the work. It is obvious that here is a highly specialized priestly literature of little popular interest. Nevertheless, it is of very great importance in the study of Vedic Hinduism.

The fourth of the Vedas, the Atharva, is of a still different kind. It has been characterized as a late book, but as containing a great deal of very ancient material, reflecting the folk religion of the early Aryans, and as carried along, it represents the cultural lag of the Vedic people. For, it is, to no small degree, a book of magic and charms. It is one of the most interesting books of antiquity and a very valuable source for an understanding of the folk religion of the Vedic period. A glance at the table of contents reveals a fascinating list of charms. There is, for example, a charm against a cough. It runs as follows:

1. As the soul with the soul’s desire swiftly to a distance flies, thus do thou, O cough, fly forth along the soul’s course of flight.

2. As a well sharpened arrow swiftly to a distance flies, thus do thou, cough, fly forth along the expanse of earth.

3. As the rays of the sun swiftly to a distance fly, thus do thou, O cough fly forth along the flood of the sea." 19

Here is a clear use of mimetic magic. As the soul’s desire, as a sharpened arrow, as the rays of the sun swiftly to a distance fly -- so let cough fly also. But just to help out there are certain things to be done besides repeating the charm. While reciting the sutra the patient takes several steps away from the home, again suggestive to the cough, but all this after being fed with a churned drink or hot porridge, i.e., making prudent use of a home remedy, like drinking hot lemonade, to make a cure doubly sure. A graduate student of English on reading this recalled the following from the Diary of the famous Samuel Pepys apparently quite soberly intended.

O cramp, be thou faintless As our Lady was sinless When she bare Jesus.

A charm for finding lost objects recalls practices of the writer’s own boyhood days. The formula is this:

On the distant path of the paths Pushan was born. . . He knows these regions all. . . . Pushan shall from the east place his right hand about us and shall bring again unto us what has been lost.

Those who seek lost property first have their hands and feet anointed. This is rubbed off and again they are anointed with ghi ( clarified butter) . Then twenty-one pebbles are thrown scatteringly upon a crossroad. These symbolize the lost objects and at the same time are supposed to counteract their lost condition. 20

We boys of a later day found lost objects sometimes by catching a daddy long-legs, saying over him a formula which unfortunately can no longer be recalled, when the great insect would solemnly point one of his long legs in the supposed direction of the lost object. Sometimes it was by the much less elegant method of spitting in the palm of the hand, striking it with a finger and seeking the lost object in the direction in which the largest spit ball flew. Innumerable examples of like folk beliefs and practices may be found in any so-called advanced culture.

Then there is a charm to promote the growth of hair (6:136) ; to obtain a husband (2:3) ; to obtain a wife (6:82) ; to secure the love of a woman (6:8) ; and to secure the love of a man (7:38) ; a charm to secure harmony (3:20) ; and one to procure influence in an assembly (3:30) ; a charm to ward off danger from fire (6:106) ; another to stop an arrow in its flight. There are prayers too, one on building a house (3:12) ; one for success at gambling (4:38) ; and particularly in playing at dice (7:50) ; an incantation for the exorcism of evil dreams (6:46) , etc. etc.

In addition there are repeated not a few hymns from the RigVeda, and still other theosophic and cosmogonic hymns of rare beauty and insight which do not seem to fit in with the cruder concept of religion apparent in the magical portions of the book.

Any anthology which presents only the high and noble points of a sacred literature really misrepresents that literature, for it is not all by any means of equal beauty or interest or of equal moral or religious insight. Most religious literatures have their high spots and their low. From the standpoint of general reader interest the Brahmanas represent the all-time low of Hindu sacred literature, and probably of all the sacred literatures of the world. The Bible has sections that are hard going. Many who bravely set out to read the Bible through from Genesis to Revelation bog down in Leviticus or sooner, and never finish. Well, Leviticus, in comparison with the greater part of the Brahmana literature, is far more interesting and intelligible to the nonpriestly reader. It has the advantage, too, that it is much shorter. Julius Eggeling, translator of the Satapatha Brahmana, says of them, "For wearisome prolixity of exposition, characterized by dogmatic assertion and a flimsy symbolism rather than serious reasoning, these works are perhaps not equalled anywhere unless indeed it be by the speculative vaporings of the gnostics, than which nothing more absurd has probably ever been imagined by rational beings." 21

The Brahmanas are strictly priestly books and are concerned primarily with the sacrifices which, with increasing complexity, had developed within Vedic Hinduism. Sacrifice had become of enormous importance. By sacrifice the gods could be at first won over to grant favors sought after; then as time went on, it became magical in its powers, and the gods themselves could not resist the prayer spell; indeed, what power they had they owed to the sacrifice. 22 It became a matter of primary importance that the sacrifice be properly performed, for in this its efficacy rested. The Brahmanas provide precisely that detailed direction. Nothing is left to the imagination or the discretion of the priest. Where he shall stand, which way he shall turn, either to right, or left, whether he shall use right hand or left, in what exact order the various ritual acts must be performed, all this is given in minutest detail.

Typical of the general character of the Brahmanas is the description of the horse sacrifice which occurs in the Satapatha Brahmana. This to be sure was the most complex as well as most important of all the Brahmanic sacrifices. It requires 166 pages in translation in the Sacred Books of the East, including extensive footnotes designed to explain the more obscure references in the text. It is much too long and involved to include here -- even a detailed description of the sacrifice, much less of the ritual associated with it. But a sample paragraph will suffice to reveal its general character. This one chosen at random, will do.

(He puts the halter on the horse, with Vag. S XXII, 3, 4,) "Encompassing thou art,"-- therefore the offer of the Asvamedha conquers all the quarters; -- "the world thou art," the world he thus conquers;-- "a ruler thou art, an upholder,"--he thus makes him an upholder; "go thou into Agni Vaisvanara," he thus makes him go to Agni Vaisvanara (the friend of all men) ;-- "of wide extent," -- he thus causes him to extend in offspring and cattle; -- "consecrated by Svaha (hail!) ," this is the Vashat -- call for it; -- "good speed (to) thee for the gods!"-- he thus makes it of good speed for the gods; "for Prajapati,"--the horse is sacred to Prajapati: he thus supplies it with his own deity. 23

If it is obscure to you, do not be troubled. Even if you read it in its context it would be but little more clear. Indeed, even with the learned translator’s detailed footnotes it still does not hold much meaning for one of our time and our culture. Reflect on the fact that this is less than one of some 160 pages of only one Kanda describing only one sacrifice, and that the Satapatha-Brahmana of which it is a part is but one of many Brahmanas, all of which were regarded as sacred by the early Hindus, and transmitted orally from priest to priest for centuries. Not only are directions given as to what to do and how to do it but, as appeared in the sample above, some explanation, of either the origin or significance of the act. This often

runs into rather profound speculations, or often into very obscure symbolism. Indeed, Eggeling calls them "theological treatises composed chiefly for the purpose of explaining the sacrificial texts as well as the origin and deeper meaning of the various rites." 24 Happily also in the midst of tiresome, repetitious instruction are to be found at least the beginnings of some important aspects of India’s later culture, philosophic speculation, grammar, astronomy, logic, and also a considerable amount of legend and myth.

Here are to be found, for example, a number of creation myths, not at all in agreement with each other. India never conceived of one single myth of the world’s creation, as found in the Bible and many other cultures. Here is a rather delightful account of the creation of night:

"Yama had died. The gods tried to persuade Yam (a twin sister) to forget him. Whenever they asked her, she said: "Only today he has died." Then the gods said: "Thus she will indeed never forget him; we will create night!" For at that time there was only day and no night. The gods created night; then arose a morrow; thereupon she forgot him. Therefore people say: "Day and night indeed. Let sorrow be forgotten." 25

Most scriptures have somewhere within them a flood story. Hindu literature is no exception, and it is found in the Brahmanas:

There lived in ancient time a holy man, Called Manu, who by penances and prayer Had won the favor of the Lord of Heaven. One day they brought him water for ablution; Then as he washed his hands a little fish Appeared, and spoke in human accents thus: "Take care of me, and I will be your savior." "From what wilt thou preserve me?" Manu asked. The fish replied, "A flood will sweep away All creatures. I will rescue thee from that." "But how shall I preserve thee?" Manu said. The fish rejoined, "So long as we are small, We are in constant danger of destruction, For fish eat fish. So keep me in a jar; When I outgrow the jar, then dig a trench And place me there; when I outgrow the trench Then take me to the ocean; I shall then Be out of reach of danger." Having thus Instructed Manu, straightway rapidly The fish grew larger. Then he spoke again, "In such and such a year the flood will come; Therefore construct a ship and pay me homage; When the flood rises enter thou the ship And I will rescue thee." So Manu did As he was ordered, and preserved the fish. Then carried it in safety to the ocean. And in the very year the fish enjoined He built a ship, and paid the fish respect, And there took refuge when the flood arose. Soon near him swam the fish, and to its horn Manu made fast the cable of the vessel. Thus drawn along the waters Manu passed Beyond the northern mountain; then the fish, Addressing Manu said, "I have preserved thee. Quickly attach the ship to yonder tree, But lest the waters sink from under thee, As fast as they subside, so fast shalt thou Descend the mountains gently after them." Thus he descended from the northern mountain, The flood had swept away all living creatures; Manu was left alone. Wishing for offspring, He earnestly performed a sacrifice. In a year’s time a female was produced; She came to Manu; then he said to her, "Who art thou?" She replied, "I am thy daughter." He said, "How, lovely lady, can that be?" "I came forth," she rejoined, "from thine oblations Cast upon the waters; thou wilt find in me A blessing; use me in the sacrifice." With her he worshiped, and with toilsome zeal Performed religious rites, hoping for offspring. Thus were created men called sons of Manu. Whatever benediction he implored With her, was thus vouchsafed in full abundance. 26

But if lacking in interest for the general readers, these dry, uninspired priestly directions are of very great importance to the student of India’s religion. Already may be seen a notable shift away from the old simple Vedic conceptions. The Vedic gods had largely lost their power and significance. New deities, particularly Prajapati, Lord of creatures, stand as the central figures. In the end, as may well be imagined, this luxuriant over-emphasis upon the power of the sacrifice, leading naturally to an exaltation of the power of the priests, who alone possessed the secrets of their proper performance, were the undoing of Vedic religion, and it finally disappears. New forms of religious faith take its place and new gods arise to replace the older ones, as we shall presently see. It represents a stage in transition from Vedic religion to the philosophic Hinduism and the sectarian, theistic Hinduism which has come down to our own time.

The date of the Brahmanas cannot be fixed with exactness, but they follow after the Vedas and precede the rise of the Upanishads which in turn are, the older ones, definitely pre-Buddhistic. The Brahmanas are found in connection with the various Vedas. As indicated above in the Black Yajur-Veda, the Brahmana material is interspersed throughout the Veda, while in the White Yajur-Veda the Brahmana forms an appendix to the Veda. They were undoubtedly at first designed for the training of priests. The earlier instruction may have been quite informal, but gradually it became stereotyped and finally unchangeable. There were, however, differences in the Brahmanas as taught in different schools.

But not all the development of religious thought was of priestly origin. Indeed, it may well have been that as the cult grew more complex and overgrown, lay members of the community became impatient with it and with the ideas behind it, and began to think about religion themselves. By this time, the stratification of society into fixed castes, a thing unknown in the Vedas, save in the late tenth book, was complete. The preferred position of the priest or Brahmin had been securely fixed. His was definitely the top ranking class, quite above the Kshatriya, the ruler-warrior class, and the Vaisya or farmer-merchant group, and his supremacy has continued into our own times. These three classes, known as the twice-born castes, were sharply set off from the lowly Sudra who was non-Aryan in origin, and carried on the heavy unpleasant work of the world. But by no means all the intelligence was to be found among the Brahmins. Even in the Brahmanas and again and again in the Upanishads there are stories of teachers seeking enlightenment on points of religious thought from kings or nobles. Nor were all members of the Brahmin caste priests. Buddhism very definitely arose out of the experience and ponderings of a prince, one of the Kshatriyas. And it is conjectured that much of the impulse to the profound religious and philosophical speculation which forms the basis of the Upanishads was from the non-Brahmin ranks.

Certain it is that before the time of the Upanishads, men of the non-Brahmin castes had undertaken to become ascetics and hermits and give themselves to contemplation of the great problems of religious and philosophic thought. The Brahmins, if they did not originate the custom, ultimately embraced it and integrated it into a system of Ashramas, or the four stages of life. The first stage was that of the student. Those of the twice-born castes were to begin early the study of the Vedas, which meant to live in the home of a teacher and serve him while learning the wisdom of the sacred texts. At an appropriate time the student was to become a householder, marry, rear a family, and perform the proper sacrifices to the gods. Then, when past middle age, he was to go apart from the common life, and to dwell in the forest, passing the time in contemplation and meditation. When at last old age had come he was supposed to abandon all connections with home, with family, and the common life, and become a sannyasin, or holy man, a wandering beggar for God.

Of course not every male of the twice-born castes followed this program, but many did. Upon what should these forest dwellers meditate? At first this may have been left wholly to the individual but in time it also became formalized, and there came into being what are known as the Aranyakas or Forest Treatises. These were sometimes included in the Brahmanas or appended to them, but they were of a different kind. No longer is the concern with the rules of sacrifice and ceremonies, but with mysticism and the symbolism of sacrifice, and with the more philosophic aspects of religion. There had grown up a body of secret doctrine, an esoteric type of thought; not to be taught to the uninitiated in the villages, but to be meditated upon in the forest. This all in time became a part of the Veda. There are Aranyakas belonging to the various schools, thus the Aitareya-Aranyaka, which contains the Aitareya-Upanishad, is attached to the Aitareya-Brahmana of the Rig-Veda. There is no clear line of distinction between the Aranyakas and the Upanishads which the non-specialist can easily discern.

The Upanishads, which, with the Aranyakas, form the Vedanta, or the end of the Veda, are probably the most important parts of the Veda. They are the basis of Indian philosophy and philosophic Hinduism, the religion of the intelligentsia of India, and have affected the thought of all India with reference to religion.

Save in the tenth book of the Rig-Veda, the Vedas in general, like the Old Testament, take the gods for granted. There is little or no reflection upon them. In the Brahmanas there is the beginning of questioning about the world and its origins. In the Aranyakas to a still greater degree it goes forward, but in the Upanishads it comes to flower. 27 Here the chief concern is to ask ultimate questions concerning man, and his world, and his final destiny. It represents both an intellectual and a religious interest. Concerned with the nature of the world ground, it is also interested in how man must relate himself to this ultimate reality in order to achieve what, in Christianity, is called salvation. To the Hindu it was Moksha.

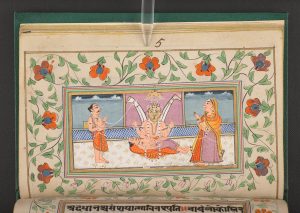

It would be a mistake to think of the Upanishads as formal books of philosophy, abstruse discussions of highly profound and difficult subjects. They are, first of all, tied on bodily to the Vedas, Brahmanas and Aranyakas, sometimes contained within the latter. There is in them a great deal that has to do with sacrifice and the cult in general. There is also a good deal of myth and legend. There are long, tiresome, repetitious discussions of what seem, on first reading, to be puerile matters. One who has heard of the vast importance of the Upanishads, and has read scattered excerpts of rare beauty and insight, is likely to feel a sense of shock as he sits down to read through the whole collection of the 12 or 13 principal Upanishads. Some of it is crude, childish, and in such passages as give only the list of names of the teachers through whom the teachings have been handed down, one finds it about as inspiring as the "begatting" or genealogical chapters of the Old and New Testament. But if the reader persists he will come upon passages of deep insight, beauty of expression and profound understanding of the great problems of religion and human thought. One’s first excursion into these basic philosophic texts would best be through some modern expurgated edition or anthology, which has carefully weeded out the crudities, the repetitiousness, and contradictions that so much abound in the original. 28

The word Upanishad seems to mean "secret doctrine." It is also defined as meaning, literally, that which dispels darkness or ignorance completely. It may be written in prose, or in poetry. There are, all told, over 100 Upanishads in existence, many of them quite late. But of the earlier ones which may be surely said to be Vedic there are only a few, some recognize twelve, some fourteen. R. E. Hume’s book, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, 29 contains a translation of those which are rather generally accepted as basic to a study of Hindu religion and philosophy.

A great deal of the material of the Upanishads is in dialogue form. A seeker after knowledge comes to a recognized teacher to inquire about some phase of religion or thought. A somewhat Socratic dialogue ensues, in which the answer is finally given. It is interesting to note the variety of people who ask the questions, kings and commoners, some of very humble birth, both men and women. Apparently women enjoyed a relatively high status at that time.

As an example of dialogue that between Yajnavalkya, a famous teacher, and a woman, Gargi, may be cited. She approaches the teacher and begs permission to ask a question. Yajnavalkya replies graciously:

She said: "That, O Yajnavalkya, which is above the sky, that which is beneath the earth that which is between these two, sky and earth, that which people call the past and the present and the future -- across what is that woven, warp and woof?"

He said: ‘That, O Gargi, which is above the sky that which is between these two, sky and earth, that which people call the past, and present and future -- across space is that woven, warp and woof."

She said: "Adoration to you, Yajnavalkya, in that you have solved this question for me. Prepare yourself for the other."

"Ask, Gargi."

She said, "Across what then, pray, is space woven, warp and woof?"

He said: "That, O Gargi, Brahmans call the Imperishable (Aksara) . It is not coarse, not fine, not short, not long, not glowing (like fire) , not adhesive (like water) , without shadow and without darkness, without air and without space, without stickiness (intangible) , odorless, tasteless, without eye, without ear, without voice, without wind, without energy, without breath, without mouth, without personal or family name, unaging, undying, without fear, immortal, stainless, not uncovered, not covered, without measure, without inside and without outside.

"It consumes nothing soever.

"No one soever consumes it.

‘Verily, O Gargi, at the command of that Imperishable the sun and the moon stand apart. Verily, O Gargi, at the command of that Imperishable the earth and the sky stand apart. Verily, O Gargi, at the command of that Imperishable the moments, the hours, the days, the nights, the fortnights, the months, the seasons, and the years stand apart. Verily, O Gargi, at the command of that Imperishable some rivers flow from the snowy mountains to the east, others to the west, in whatever direction each flows. Verily, O Gargi, at the command of that Imperishable men praise those who give, the gods are desirous of a sacrificer, and the fathers (are desirous) of the Manes-sacrifice.

"Verily, O Gargi, if one performs sacrifices and worships and undergoes austerity in this world for many thousands of years, but without knowing that Imperishable, limited indeed is that (work) of his. Verily, O Gargi, he who departs from this world without knowing that Imperishable is pitiable. But, O Gargi, he who departs from this world knowing that Imperishable is Brahman.

"Verily, O Gargi, that Imperishable is the unseen Seer, the unheard Hearer, the unthought Thinker, the ununderstood understander. Other than It there is naught that sees. Other than It there is naught that hears. Other than It there is naught that understands. Across this Imperishable, O Gargi, is space woven, warp and woof." 30

On another occasion when Gargi had pushed Yajnavalkya back step by step, a device often used in the Upanishads and known as the regressus, to Brahman as the ultimate reality, she still persisted in asking what lay behind Brahman. Yajnavalkya said:

"Gargi, do not question too much, lest your head fall off. In truth, you

are questioning too much about a divinity about which questions cannot

be asked. Gargi, do not over-question."

Thereupon Gargi Vacaknaivi held her peace. 3 ’

Another regressus throws not a little light upon the shifting away from the old Vedic gods to the One, Brahman. It is given in slightly abbreviated form:

1. Then Vidagdha Sakalya questioned him. "How many gods are there, Yajnavalkya?"

He answered in accord with the following Nivid ( invocationary formula) : "As many as are mentioned in the Nivid of the Hymn to All the Gods, namely, three hundred and three, and three thousand and three (=3306) ."

"Yes," said he, "but just how many gods are there, Yajnavalkya?"

"Thirty-three."

"Two." "Yes," said he, "but just how many gods are there, Yajnavalkya?"

One and a half."

There is space for only one final dialogue dealing with the At-man, which, together with Brahman, constitute the two major concepts dealt with in the Upanishads. Their ultimate identification in Brahman-Atman is the culmination of the long time trend toward the monistic or pantheistic world-soul which began in the tenth book of the Rig-Veda. Also the realized identification of the Atman, or self, or soul of man, with Brahman, constitutes moksha or salvation for some schools of philosophic Hinduism.

King Janaka of Videha once asked of Yajnavalkya;

2. "Yajnavalkya, what light does a person here have?"

"He has the light of the sun, O king," he said, "for with the sun, indeed, as his light, one sits, moves around, does his work, and returns.

"Quite so, Yajnavalkya.

3. "But when the sun has set, Yajnavalkya, what light does a person here have?"

"The moon, indeed, is his light," said he, "for with the moon, indeed, as his light, one sits, moves around, does his work, and returns."

4. "But when the sun has set, and the moon has set, what light does a person here have?"

"Fire, indeed, is his light," said he, "for with fire," etc.

5. "But when the sun has set, Yajnavalkya, and the moon has set, and the fire has gone out, what light does a person here have?"

"Speech, indeed, is his light," said he, "for . . . when a voice is raised (even in the dark) then one goes straight towards it."

6. "But when the sun has set, Yajnavalkya, and the moon has set, and the fire has gone out, and speech is hushed, what light does a person here have?"

"The soul (atman) , indeed, is his light," said he, "for with the soul, indeed, as his light, one sits, moves around, does his work, and returns." 33

The famous phrase tat tvam asi, "that art thou," expressing the identity of the self of man with Brahman-Atman occurs over and over again in a long dialogue between Svetaketu and his father, for example:

Said the father:

1. "Place this salt in the water. In the morning come unto me. Then he did so.

Then he said to him: "That salt you placed in the water last evening -- please bring it hither."

Then he grasped for it, but did not find it, as it was completely dissolved.

2. "Please take a sip of it from this end," said he. "How is it?"

"Take a sip from the middle," said he. "How is it?"

"Take a sip from that end," said he. "How is it?"

"Set it aside. Then come unto me.

He did so, saying, "It is always the same."

Then he said to him: "Verily, indeed, my dear, you do not perceive Being here. Verily, indeed, it is here.

3. "That which is the finest, essence -- this whole world has that as its soul. That is Reality. That is Atman (Soul) . That art thou, Svetaketu."

"Do you, sir, cause me to understand even more.

"So be it, my dear," said he. 34

But how shall this moksha which is release from the round of rebirth be accomplished? To the authors of the Upanishads, Vedic sacrifice was unable to help one here. It could come only through knowledge or realization of the truth of the identity of the Atman of living man with Brahman-Atman. The Upanishads themselves suggest the way of meditation under direction of a teacher, but have little to say with regard to the precise methods to be employed. Later thinkers were to develop elaborate schemes whereby man might achieve this end. In general Yoga practice in one form or another, i.e., disciplined meditation, was the answer.

Here in the Upanishads come to full expression two doctrines unknown in the Vedas, that of Karma, ot the law of sowing and reaping, and that of reincarnation. Both are expressed in the following:

3. Now as a caterpillar, when it has come to the end of a blade of grass, in taking the next step draws itself together towards it, just so this soul in taking the next step strikes down this body, dispels its ignorance, and draws itself together (for making the transition) .

4. As a goldsmith, taking a piece of gold, reduces it to another newer and more beautiful form, just so this soul, striking down this body and dispelling its ignorance, makes for itself another newer and more beautiful form like that either of the fathers, or of the Gandharvas, or of the gods, or of Prajapati, or of Brahman, or of other beings.

5. Verily, this soul is Brahma, made of knowledge, of mind, of breath, of seeing, of hearing, of earth, of water, of wind, of space, of energy and of non-energy, of desire and of non-desire, of anger and of non-anger, of virtuousness and of non-virtuousness. It is made of everything. This is what is meant by the saying "made of this, made of that."

According as one acts, according as one conducts himself, so does he become. The doer of good becomes good. The doer of evil becomes evil. One becomes virtuous by virtuous action, bad by bad action. 35

Though the doctrine of reincarnation was worked out in much greater detail in subsequent Hindu sacred literature, it is expressed in the Lipanishads in rudimentary form thus:

15. Those who know this, and those, too, who in the forest truly worship (upasate) faith (sraddha) , pass into the flame (of the cremation-fire) ; from the flame, into the day; from the day, into the half month of the waxing moon; from the half month of the waxing moon, into the six months during which the sun moves northward; from these months, into the world of the gods (devaloka) ; from the world of the gods, into the sun; from the sun, into the lightning-fire. A person (purusa) consisting of mind (manasa) goes to those regions of lightning and conducts them to the Brahma-worlds. In those Brahma-worlds they dwell for long extents. Of these there is no return.

16. But they who by sacrificial offering, charity, and austerity conquer the worlds, pass into the smoke (of the cremation-fire) ; from the smoke, into the night; from the night, into the half month of the waning moon; from the half month of the waning moon, into the six months during which the sun moves southwaid; from those months, into the world of the fathers; from the world of the fathers, into the moon. Reaching the moon, they become food. There the gods -- as they say to King Soma, "Increase! Decrease!"-- even so feed upon them there. When that passes away for them, then they pass forth into this space; from space, into air; from air, into rain; from rain, into the earth. On reaching the earth they become food. Again they are offered in the fire of man. Thence they are born in the fire of woman. Rising up into the world, they cycle round again thus.

But those who know not these two ways, become crawling and flying insects and whatever there is here that bites. 36

Parts of the Upanishads are in verse. Here we have space for only three brief poems on Brahman, favorite theme of the writers of the "secret doctrine."

As oil in sesame seeds, as butter in cream, As water in river-beds, and as fire in the friction-sticks, So is the Soul (Atman) apprehended in one’s own soul, If one looks for Him with true austerity (tapas) . The Soul (Atman) , which pervades all things As butter is contained in cream, Which is rooted in self-knowledge and austerity -- This is Brahma, the highest mystic doctrine (upanishad) ! This is Brahma, the highest mystic doctrine! 37

The second illustrates the way in which the Brahman concept gathers up into itself the old Vedic gods.

Thou art Brahma, and verily thou art Vishnu. Thou art Rudra. Thou art Prajapati, Thou art Agni, Varuna, and Vayu. Thou art Indra. Thou art the Moon. Thou art food. Thou art Yama. Thou art the Earth. Thou art All. Yea, thou art the unshaken one!

For Nature’s sake and for its own Is existence manifold in thee. O Lord of all, hail unto thee! The Soul of all, causing all acts, Enjoying all, all life art thou! Lord (prabhu) of all pleasure and delight!

Hail unto thee, O tranquil Soul (santatman) ! Yea, hail to thee, most hidden one, Unthinkable, unlimited, Beginningless and endless, too! 38

And finally, from the Mundaka comes this summing-up of the whole in Brahman:

Brahma, indeed, is this immortal. Brahma before, Brahma behind, to right and to left. Stretched forth below and above. Brahma, indeed, is this whole world, this widest extent. 39

The Upanishads have had an extraordinary influence on all subsequent religious and philosophic thought. No writer on Indian philosophy would think of beginning anywhere but in the Veda, meaning primarily the Upanishads. Out of them have grown six historical schools of philosophic thought, and each of these has had its effect upon Indian religion. Best known in the West is the Vedanta school. Others are the Nayaya, the Mimansa, the Sankhya, the Yoga, and the Vaiseshika. 40

Religiously, the concept of Brahman has had a very profound effect on Indian religion. Since Brahman is the one and only real -- all the gods of whatever sectarian group can have no reality other than they have in Brahman. They can only be regarded as manifestations, at various levels, of the neuter world soul. Thus a cloak of unity is thrown over all kinds of religions which have appeared in India. Indeed, this concept provides Hinduism with an absorptive quality which enables it to accept any religion from any source as simply a phase of the ultimately real Brahman -- so long as it does not make exclusive claims for its deity as do Christianity and Islam. Here the resistance is rather on the part of the representatives of these aggressively exclusivist faiths to such an acceptance.

The Upanishads have been quite influential throughout the west. Schopenhauer, among European philosophers, has spoken of them in terms of high esteem:

In the whole world there is no study except that of the originals, as beneficial and so elevating as that of the Upanishads (in translation) . It has been the solace of my life; it will be the solace of my death.

From every s~ntence deep original and sublime thoughts arise, and the whole is pervaded by a high, holy and earnest spirit. 41

Emerson got the inspiration from their reading for his great poem, Brahma. Thoreau read them and was influenced by them. The whole atmosphere of New England thought in the latter part of the nineteenth century was affected by them. In more recent times, as translations have been muhiplied, they have been read by vast numbers of people. A recent book, Vedanta for the Western World interprets them to an increasing circle of intelligent readers. Theosophy has taken over some of the basic ideas of the Upanishads and popularized them in the West, and their indirect influence is to be seen in a number of small modern religious movements in America. 42

The Upanishads are the source of the doctrines which furnish the basis for the Vedanta-Sutras of Badarayana, which are by some considered to be sruti literature. On this are based the commentaries of Shankara and of Ramanuja whose writings have influenced and are still influencing the religious thought of countless millions of Indians.

With the Upanishads we come to the end of the Veda, and also the end of the sruti sacred literature, with the exception of the Bhagavad Gita, which if not universally so recognized is, by great numbers of Indians, ranked along with the most sacred Vedic literature. To that we shall come back later. But we are only at the beginning of the discussion of literature of the smriti type, which, for all practical purposes, is quite as important in the religious life of the Indian people as the older sruti. Indeed, rather more so, for actually Vedic religion no longer exists. The old Vedic gods are gone, with the exception of a very few --chiefly Vishnu. Orthodox Indians regard their later literatures as growing out of and fulfilling the Vedas, but in no sense as abrogating them. Typical of the attitude of modern Hindu thought is the statement of D. S. Sarma in his Primer of Hinduism, written for the instruction of young Hindus in this faith:

Q. Why, if the Veda is our primary scripture, should we not go direct to it without caring for any of the secondary scriptures?

A. The Veda is like a mine of gold, and the later scriptures are like the gold coins of the various ages. When you want to procure things that would make you comfortable, you should have ready money and not a piece of rock with veins of gold in it straight from the mine. Of course every gold coin that is in the country is ultimately derived from the mine; but has undergone various processes that make it useful to us at once. The ore has been smelted, the dross has been removed, the true metal has been refined, put into moulds and stamped. Similarly the golden truths of the Veda have been refined by the wisdom of the ages and presented to us in a useful form, in our later scriptures. That is why I recommend to you the Gita, rather than the Upanishads. 43

While the application was in this case specifically to the Bhagavad Gita, note that he says "presented to us in our later scriptures."