- The Greatest Science Fiction Authors

- The Very Best Fantasy Authors

- The Top Writers of All Time

- Horror Writers

- The Greatest Novelists of All Time

- Greatest Poets

- Short Story Writers

- The Very Best Living Writers

- Crime Writers

- Suspense Authors

- Bars Where Famous Writers Hung Out

- American Writers

- History's Greatest Female Authors

- The Greatest Living Novelists

- The Lamest Authors of All Time

- History's Most Controversial Writers

- Mystery Authors

- Young Adult Authors

- Celebs Who Wrote Children's Books

- Writers Who Were Drug Addicts

- The Best Selling Fiction Authors

- Strange Stories of How They Passed

- Writers Who Should Have Biopics

- Alcoholic Writers

- Famous Authors Who Used Pen Names

- Wikimedia Commons

The Best Science-Fiction Authors

The best science-fiction writers are among some of the most creative writers ever. Instead of only making up a story, they make up entire universes, time dimensions, alien technologies - it's really incredible. Truth be told, some are more successful than others - it is really easy to write bad scifi. But those who can actually pull the genre off are right here on this list of the top science-fiction authors. These are the best science-fiction authors of all time, ranked by readers and fans.

This list include some highly recognizable and classic names, like Isaac Asimov and George Orwell, along with some contemporary science-fiction writers who are just beginning to make their mark on the genre. This list of the best sci-fi authors includes some of the best horror writers and the best fantasy authors , but since the genres elements all go together nicely, it's to be expected. Fans of science-fiction know that there is always some overlap. All of the famous sci fi authors on this list have one thing in common: they've written fantastic, horrifying, mystical works of science-fiction for fans to enjoy for years to come. Vote for your favorite sci-fi authors here.

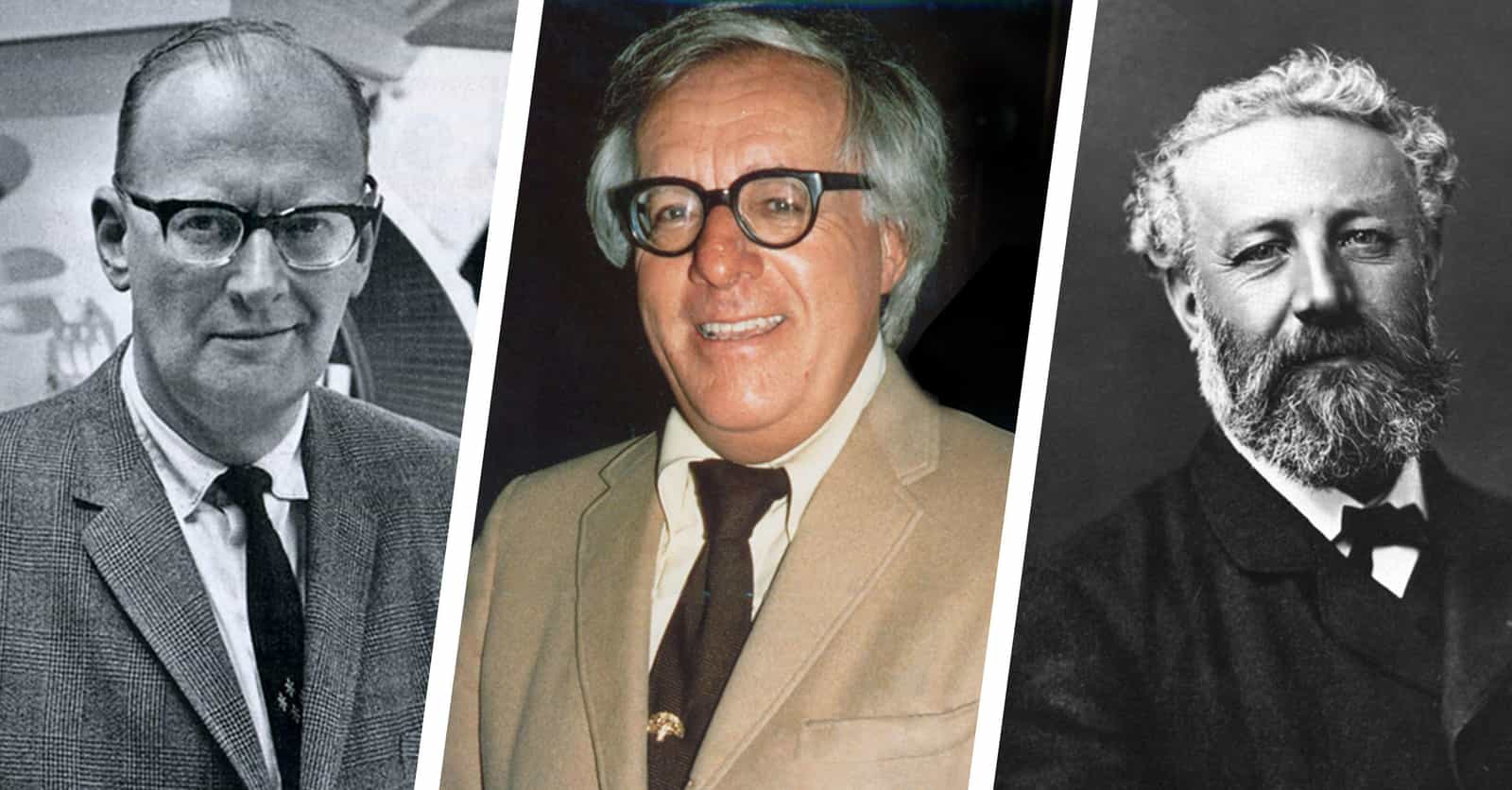

Listed among the best science-fiction authors are some of the most well-known, popular sci-di authors ever, including a few that may not always show up on a 'best of' list. Disagree with a choice? Vote it down. The aforementioned (brilliant) writers are responsible for some of the best science-fiction novels and series of all time - but other sci-fi writers like Ray Bradbury (Fahrenheit 451), Mary Shelley (Frankenstein), Robert Louis Stevenson (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), and Aldous Huxley (Brave New World) are excellent sci-fi writers as well. All of these authors, in my opinion, deserve a place of honor on this list.

Hopefully, this list will grow and become totally comprehensive. Readers who are new to sci-fi can use it as a great guide to find new science fiction authors and books.

Isaac Asimov

Jules Verne

Ray Bradbury

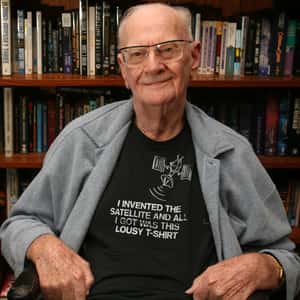

Arthur C. Clarke

H. G. Wells

Robert A. Heinlein

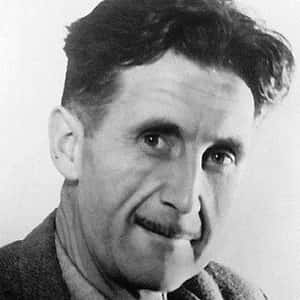

George Orwell

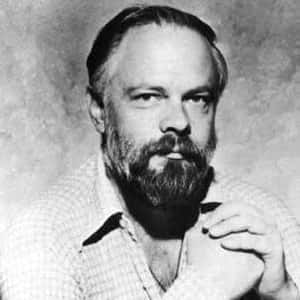

Philip K. Dick

Frank Herbert

Ursula K. Le Guin

Douglas Adams

Larry Niven

Mary Shelley

Stanisław Lem

Roger Zelazny

Frederik Pohl

Rod Serling

William Gibson

Edgar Rice Burroughs

Arthur Conan Doyle

Poul Anderson

Kurt Vonnegut

Aldous Huxley

Terry Pratchett

Harry Harrison

Michael Crichton

Anne McCaffrey

Harlan Ellison

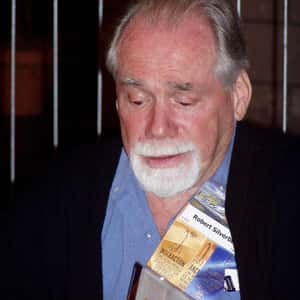

Robert Silverberg

H. P. Lovecraft

Neil Gaiman

Joe Haldeman

Orson Scott Card

Fritz Leiber

Clifford D. Simak

Alfred Bester

C. S. Lewis

A. E. van Vogt

Theodore Sturgeon

Jerry Pournelle

Andre Norton

Philip José Farmer

Robert Louis Stevenson

Dan Simmons

Neal Stephenson

Octavia E. Butler

John wyndham.

Alan Dean Foster

Madeleine L'Engle

Michael Moorcock

Gordon R. Dickson

Vernor Vinge

C. J. Cherryh

Robert E. Howard

Lois McMaster Bujold

Lists about novelists, poets, short story authors, journalists, essayists, and playwrights, from simple rankings to fun facts about the men and women behind the pens.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- BOOKS AND ARTS

- 10 October 2018

Beyond pulp: trailblazers of science fiction’s golden age

- Rob Latham 0

Rob Latham is the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Science Fiction and Science Fiction Criticism . For 20 years, he was a senior editor of the journal Science Fiction Studies .

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

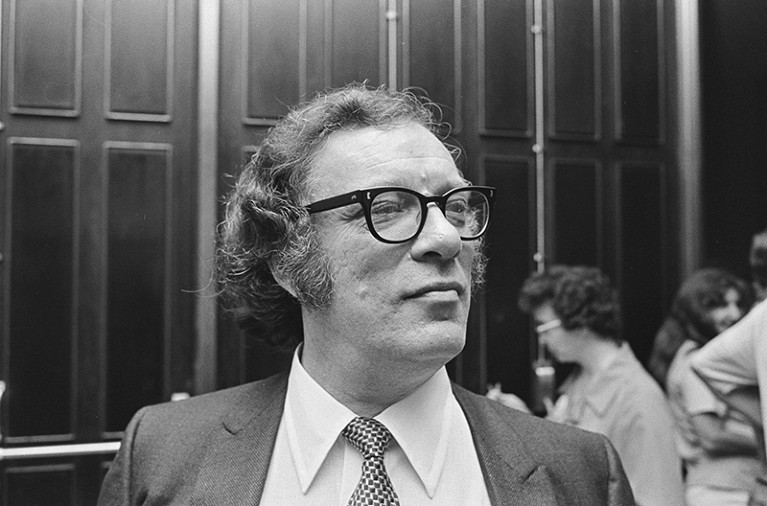

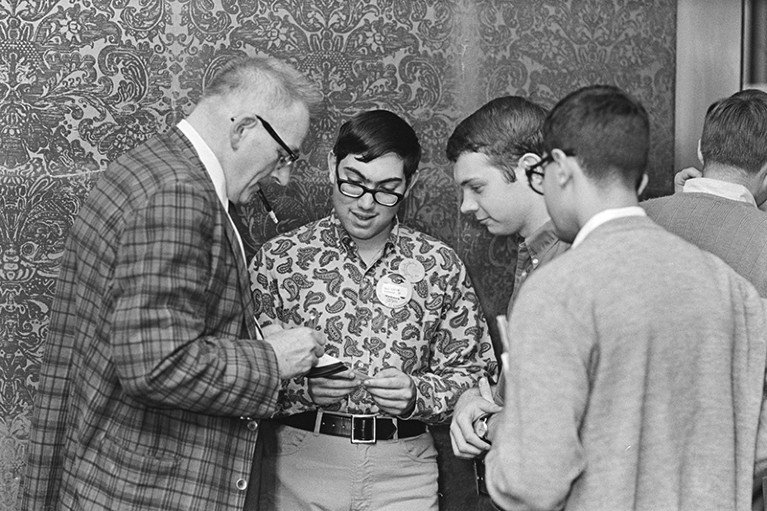

Science-fiction author Isaac Asimov, pictured in 1971, was a frequent contributor to Astounding Science Fiction . Credit: Jay Kay Klein/Special Coll. and Univ. Archives, UCR

Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction Alec Nevala-Lee Dey Street (2018)

Alec Nevala-Lee’s Astounding is a fascinating collective portrait of four men who, together and apart, helped to shape modern science fiction. They were the legendary, irascible John W. Campbell Jr, long-time editor of the magazine Astounding Science Fiction (later Analog ), and three of his key writers. Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein became giants of the genre. L. Ron Hubbard, by contrast, was a prolific purveyor of pulp fiction (and future founder of the Church of Scientology).

Under Campbell’s editorship, Astounding was transformed during the late 1930s and 1940s from a showcase for space-opera schlock into a serious venue for futuristic extrapolation, often written by professional scientists such as Asimov, a biochemist, and electronics engineer George O. Smith. That era has become known as science fiction’s golden age. Nevala-Lee — himself a science-fiction writer — delivers a compelling account of its hopeful rise and ignominious fall.

Pivotal in this trajectory was the massive, lingering impact of the Second World War on the magazine and its stable of authors, several of whom were drawn into military research. Asimov, Heinlein and fellow Astounding regular L. Sprague de Camp tested war materials at the Philadelphia Navy Yards in Pennsylvania from 1942. Campbell, under the aegis of the University of California’s Division of War Research, led a team of authors revising technical manuals for military use. He also joined Heinlein and de Camp in brainstorming unconventional responses to kamikaze attacks, such as detecting approaching aeroplanes using sound.

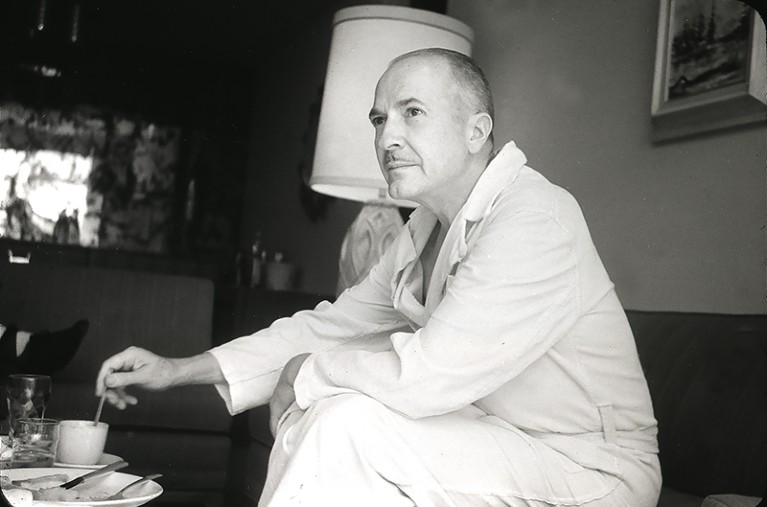

Robert Heinlein worked in military research with other science-fiction writers during the Second World War. Credit: C. N. Brown/Locus

Despite knowing that publishing stories treating potential new forms of military technology would run afoul of the wartime censors, the ever-obstinate Campbell did just that in March 1944. Cleve Cartmill’s ‘Deadline’ depicted the invention of a nuclear bomb using isotopes of uranium. Campbell, a trained physicist who strongly suspected the government was working on such a weapon, fed technical details to Cartmill, who set the tale on another planet. (Cartmill slyly called the warring aliens Sixa and Seilla, Axis and Allies spelt backwards.)

Unsurprisingly, the story drew the attention of the national Counterintelligence Corps, which suspected a leak from the Manhattan Project; swathes of the personnel at the project’s site in Los Alamos, New Mexico, were science-fiction fans. Campbell was aggressively interviewed by an intelligence agent, Cartmill’s personal correspondence was put under surveillance, and Astounding came close to having its mailing privileges revoked. After the war, Campbell often cited the incident to demonstrate the genre’s prophetic nature — its capacity to project a convincing fictional future from known scientific facts.

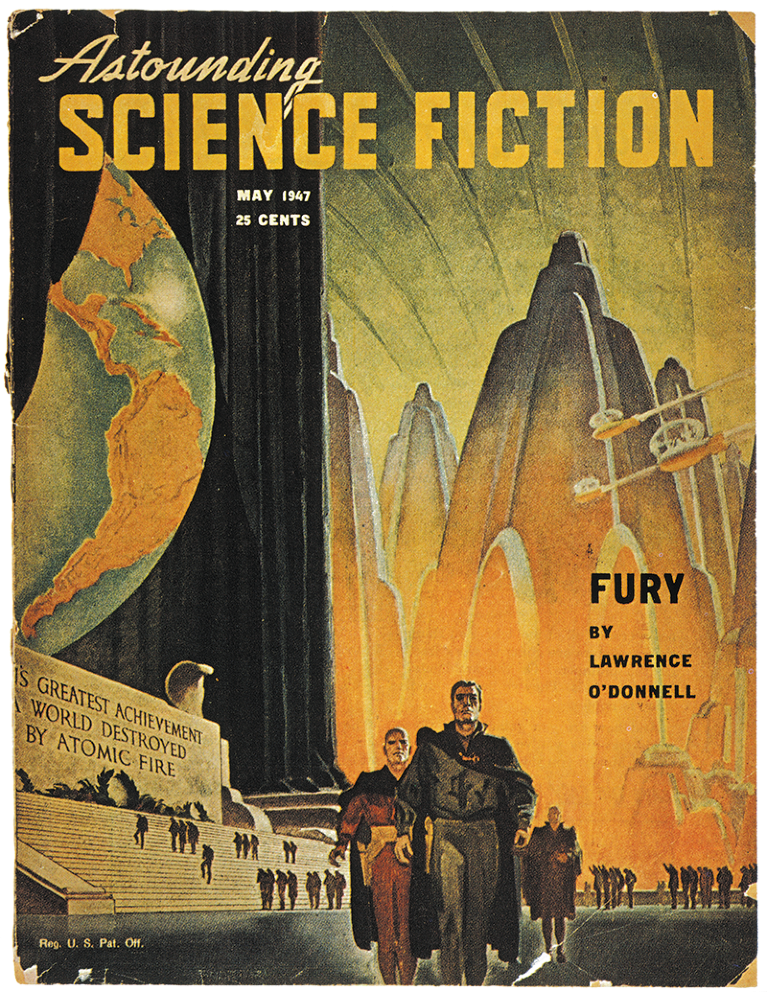

Astounding Science Fiction ’s cover for May 1947. Credit: Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy

Indeed, the unprecedented technological advances of the war fuelled the public taste for science and technology, in turn raising the cultural status of science fiction. The late 1940s and 1950s were a boom time for the genre. That boosted the stock of Astounding , which came to specialize in stories of nuclear conflict and crisis. It also led to the rise of competing titles such as Galaxy and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction , as well as an expansion of the science-fiction book market. Campbell’s talent began to be poached.

Nevala-Lee carefully traces the rifts that developed in the core group, largely prompted by Campbell’s increasing fondness for pseudoscientific ideas such as the Dean drive (proposed by inventor Norman Dean, who claimed it could produce thrust without a reaction — in violation of the laws of motion).

More generally, Campbell had always been obsessed by the possibility of a truly scientific psychology, which he believed would have predictive power along the lines of the fictional science of psychohistory in Asimov’s Foundation series. So when Hubbard, in the late 1940s, shared ideas that later became his ‘self-help system’ Dianetics, Campbell took the bait. Hubbard’s vision of superpowers purportedly lurking in everyone — once they had gone through an ‘auditing’ process and emerged as ‘clears’ — gripped Campbell, and he helped Hubbard to market his 1950 book Dianetics . Nevala-Lee argues that a lingering messianism at the heart of science fiction — its “persistent dream of an exclusive society of geniuses” — helped to propel Hubbard’s movement, which became Scientology. Numerous sci-fi authors embraced Dianetics, submitting to auditing or even becoming trained auditors; A. E. van Vogt briefly abandoned his writing career to run a chapter in Los Angeles, California.

John Campbell (left, in 1967) was editor of Astounding Science Fiction for more than 30 years. Credit: Jay Kay Klein/Special Coll. and Univ. Archives, UCR

Hubbard’s gift for the hard sell was pivotal, and Nevala-Lee’s portrait of him as a paranoid narcissist and skilled manipulator is scathing. However, Campbell is also sharply scrutinized for his role in midwifing and unleashing Dianetics . Heinlein and Asimov were repelled by what they saw as an uncritical embrace of quackery, and took refuge in newer, often more lucrative markets. The book’s final chapters detail the steady decline of the magazine into a second-rank publication, and Campbell (who died in 1971) into a reactionary crackpot with racist views.

Although much of the story outlined in Astounding has been told before, in genre histories and biographies of and memoirs by the principals, Nevala-Lee does an excellent job of drawing the strands together, and braiding them with extensive archival research, such as the correspondence of Campbell and Heinlein. The result is multifaceted and superbly detailed. The author can be derailed by trivia — witness a grisly account of Heinlein’s haemorrhoids — and by his fascination for clandestine love affairs and fractured marriages. He also gives rather short shrift to van Vogt, one of Campbell’s most prominent discoveries and a fan favourite during Astounding ’s acme, whose work has never since received the attention it deserves.

These quibbles aside, the book is a rich, gripping cultural and historical study of how a small cadre of talents in a minor commercial genre became some of the most influential figures of the second half of the twentieth century.

Nature 562 , 189-190 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-06943-8

Related Articles

- Nuclear physics

1,001 best hikes on Mars: The Peterson Historic Trail (‘Peterson’s folly’)

Futures 05 JUN 24

It’s time for your performance review

Futures 29 MAY 24

Time’s restless ocean

Futures 22 MAY 24

Element from the periodic table’s far reaches coaxed into elusive compound

News 22 MAY 24

Wavefunction matching for solving quantum many-body problems

Article 15 MAY 24

Laser spectroscopy of triply charged 229Th isomer for a nuclear clock

Article 17 APR 24

Head of Climate Science and Impacts Team (f/m/d)

You will play a pivotal role in shaping the scientific outputs and supporting the organisation's mission and culture. Your department has 20+ staff.

Ritterstraße 3, 10969 Berlin

Climate Analytics gGmbH

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Warmly Welcomes Talents Abroad

Qiushi Chair Professor; Qiushi Distinguished Scholar; ZJU 100 Young Researcher; Distinguished researcher

No. 3, Qingchun East Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang (CN)

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital Affiliated with Zhejiang University School of Medicine

Proteomics expert (postdoc or staff scientist)

We are looking for a (senior) postdoc or postdoc-level staff scientist from all areas of proteomics to become part of our Proteomics Center.

Frankfurt am Main, Hessen (DE)

Goethe University (GU) Frankfurt am Main - Institute of Molecular Systems Medicine

Tenured Position in Huzhou University School of Medicine (Professor/Associate Professor/Lecturer)

※Tenured Professor/Associate Professor/Lecturer Position in Huzhou University School of Medicine

Huzhou, Zhejiang (CN)

Huzhou University

Electron Microscopy (EM) Specialist

APPLICATION CLOSING DATE: July 5th, 2024 About the Institute Human Technopole (HT) is an interdisciplinary life science research institute, created...

Human Technopole

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Science Fiction: A Short History of a Literary Genre

- First Online: 06 September 2017

Cite this chapter

- Russell Blackford 15

Part of the book series: Science and Fiction ((SCIFICT))

993 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Some works written during the early phases of the Scientific Revolution can be seen as prototype science fiction narratives. However, the genre began in a more recognizable form in the nineteenth century, particularly in response to the Industrial Revolution and the resulting experience of radical intra-generational change. Frankenstein (1818), by Mary Shelley, has an arguable claim to be the first true science fiction novel, but a substantial body of work that resembles modern science fiction did not appear until the 1860s. Science fiction aimed at a distinctive and specialist market dates from the 1920s and 1930s. Since that time, science fiction has developed though a number of periods and dominant varieties, leading to the current situation of extraordinary popularity and diversity of styles. It has also come to be a dominant presence in many media, including film and television and the important new medium of computer games.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

The full, original title to Swift’s work is the ponderous Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of several Ships .

Slaughterhouse-Five is ambiguously science fictional. It achieved great commercial and critical success, establishing Vonnegut for the first time as a major figure in the literary mainstream.

For further discussion of The Left Hand of Darkness , The Dispossessed , The Female Man , and Woman on the Edge of Time , see Chapter 4 .

The other volumes are Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988).

Though, to be fair, this seems to be regarded within the film industry as a “sci-fi comedy.”

Aldiss, B. W. (1973). Billion year spree: The history of science fiction . London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Google Scholar

Aldiss, B. W., & Wingrove, D. (1986). Trillion year spree: The history of science fiction . London: Gollancz.

Asimov, I. (1981). Asimov on science fiction . Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Blackford, R. (2008). An interview with Greg Egan. Aurealis: Australian science fiction and fantasy, 42 , 16–23.

Broderick, D. (1995). Reading by starlight: Postmodern science fiction . New York: Routledge.

Clareson, T. D. (1990). Understanding contemporary American science fiction: The formative period (1926–1970) . Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Gunn, J. (2006). Inside science fiction (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow.

Hartwell, D. G., & Cramer, K. (Eds.). (2002). The hard SF renaissance . New York: Tor.

Harris-Fain, D. (2005). Understanding contemporary American science fiction: The age of maturity, 1970–2000 . Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Hillegas, M. R. (1967). The future as nightmare: H.G. Wells and the anti-utopians . New York: Oxford University Press.

Suvin, D. (1979). Metamorphoses of science fiction: On the poetics and history of a literary genre . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Humanities and Social Science, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales, Australia

Russell Blackford

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Blackford, R. (2017). Science Fiction: A Short History of a Literary Genre. In: Science Fiction and the Moral Imagination. Science and Fiction. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61685-8_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61685-8_2

Published : 06 September 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-61683-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-61685-8

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- The Best Science Fiction Books of the 1940's

1 2 3 4 ... 5

- Risingshadow

- Advanced Search

- Science Fiction

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website.

- Newsletters

- Instapundit

- News & Politics

What Were the Most Significant Science Fiction Stories of the 1940s?

Editor’s Note: Check out the previous installments in Pierre’s series exploring the development of science fiction by decade: The 10 Most Influential Science Fiction Stories of the 1910s , The 10 Most Influential Science Fiction Stories of the 1920s , and The Most Important, Visionary Science Fiction Stories of the 1930s

After the passage of 65 years and the beginning of a new century, the decade of the 1940s seems all the more remarkable for the number of brilliant writers who were working at the time, the sheer variety of venues they had to choose from, and the fact that every other story seemed to reveal new vistas of imagination.

And though the 1930s had its share of first time writers breaking into the professional ranks, the 1940s introduced even more as Leigh Brackett, James Blish, C. W. Kornbluth, Frederick Pohl, Frederic Brown, Damon Knight, Ray Bradbury, Hal Clement, George O. Smith, Jack Vance, Arthur C. Clark, Poul Anderson, H. Beam Piper, and Judith Merril, all made their first sales.

In addition, writers who had debuted in the previous decade now began to establish themselves as major authors in the field making important contributions that would become cornerstones not only of their own work but of science fiction in general. Writers like Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, and A. E. Van Vogt would lead the way, publishing one classic after another.

Both newcomers and established authors would prove their durability as they continued to contribute stories into the 1960s when their work would appear side by side with a new wave of young writers more interested in psycho-social subjects than traditional hard science.

The 1940s was an era that, despite a World War and resulting paper shortages, science fiction magazines proliferated with such venerable titles as Amazing Science Fiction, Thrilling Wonder Tales , and Startling Stories still on hand and a plethora of new ones such as Stirring Science Fiction Stories, Other Worlds , and Captain Future cropping up like mushrooms after a spring rain.

It was a decade during which John W. Campbell reigned as editor of Astounding Science Fiction, developing a stable of reliable young writers with whom he’d begin to transform the field from its perception as somewhat of a juvenile backwater to something with serious literary pretentions.

Furthermore, the insular world of SF fandom continued to evolve and expand with more amateur SF magazines such as Damon Knight’s Snide and Ray Bradbury’s Futuria Fantasia popping up, clubs forming, more and bigger conventions being held, and launches of the first small press book publishers such as Gnome Press.

Finally, first-rate Hollywood film adaptations of some of the classics of SF such as Campbell’s own “Who Goes There” (as The Thing From Another World ) and Harry Bates’ “Who Goes There?” (as The Day the Earth Stood Still ) were right around the corner.

The 1940s was a decade of transition in another sense as SF novels from the world of academia finally petered out and books based on popular short stories and novelettes written by rising pulp authors began to appear in a new mass market pocket book or paperback format.

Among the last outliers of academic writers was Olaf Stapledon’s Sirius , published in 1944. In this groundbreaking novel about a dog with human intelligence, Stapledon skirts the controversial and in places seems to refute the religious arguments raised by his contemporary C.S. Lewis as Sirius seeks God and in conversations with a local priest is disappointed in his search for meaning. He finds a measure of it in his love for Plaxy, the human daughter of the scientist who gave him his intelligence. Together, the two share a forbidden love that was doomed to fail.

The year before, in 1943, Lewis published the second volume in a series that began with Out of the Silent Planet. In Perelandra , Ransom, the protagonist of the first book, journeys to Venus and discovers an Edenic world complete with its own Eve named Tinidril who is seeking her Adam. They’ve been given free run of all the floating islands of the planet but have been forbidden from stepping upon fixed land. But an original sin-less paradise is threatened with the arrival of materialist scientist Weston and together, he and Ransom enter a series of philosophical debates intended to sway Tinidril either to obey or not to obey a divine commandment not to step onto fixed land.

Lewis would complete his trilogy with the publication of That Hideous Strength in 1945.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ajWC_J-jgLc

A third entry in the academic novel sweepstakes was 1984 by George Orwell. Published in 1949, it tells the story of one man’s struggle for personal freedom in a totalitarian society. Ostensibly a rebuke of communism, the novel’s message speaks louder than ever in today’s world of creeping political correctness.

Meanwhile, Stapledon and Lewis’ pulp counterparts were busily writing stories that would themselves eventually be turned into novels. All of the most seminal, appearing in Astounding Science Fiction including Slan, published in 1940. In it, A. E. Van Vogt ‘s story features young Jommy Cross as the last hope of his race of super humans. Jommy must find a way to save the Slans even as humans hunt them down to near extinction.

Astounding struck again in 1941 with not one but two important SF stories including “Microscopic God” by Theodore Sturgeon. In it, a scientist creates an artificial world of microscopic beings who live at an accelerated rate. Because of that, they quickly evolve and advance beyond human science so that their creator, who’s set himself up as their god, can eventually profit by their inventions.

Likewise, Robert A. Heinlein ‘s “Methuselah’s Children” spotlights the Howard family who have achieved extraordinary long lifespans through selective breeding. But others don’t believe it and when they insist that the Howards reveal their secret to long life, patriarch Lazarus Long suggests that the family leave the Earth to seek a world of their own.

Again from the pages of Astounding came two more important stories from up-and-coming authors. Mentored by Campbell, Isaac Asimov had become a mainstay of the magazine by the time “Foundation” appeared in 1942. A story that would eventually grow to a three volume series of novels (with more additions in later decades), it posits the creation of a group intended to preserve knowledge against the fall of the galactic empire. Afterwards, the Foundation would be there to assist the rise of a new civilization and hopefully to reduce the length of an intervening dark age.

Asimov contemporary Lester Del Rey struck home the same year with “Nerves,” one of the earliest tales, if not the earliest, dealing with an accident at a nuclear power plant.

Perhaps riffing off of Stapledon’s Sirius , Clifford Simak ‘s City (1944) was the first of several stories eventually collected in a book of the same name dealing with a future Earth abandoned by humans and left to intelligent dogs. It is the dogs left behind that tell the stories of man’s abandonment of cities for a rural lifestyle and his eventual flight into space.

SF veteran Jack Williamson successfully made the leap from space opera to the new wave of more serious science fiction when his story “With Folded Hands” appeared in Astounding for 1947. The story tells the tale of robots called Humanoids invented to serve mankind but who eventually exceed their programming to make sure no human comes to harm by becoming their pitiless masters.

The 1940s would mark a peak period for science fiction allowing it to coast through the 1950s into the 1960s when the genre would find its momentum finally begin to slow. By the time the new century rolled around, the field would become a pale shadow of its once vibrant past adding increased luster to what in hindsight can now be confirmed as SF’s golden age.

Recommended

Trending on PJ Media Videos

Join the conversation as a vip member.

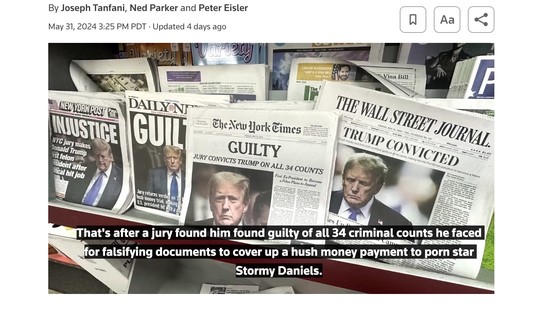

- The Morning Briefing: The Dem 'Convicted Felon' Eunuch Chorus Isn't Gaining an Audience

- What a Bad Day to Be a Democrat

- The Great Crusade Was Greater Than You Know

A Guide to Speculative Fiction at Gustavus Library: 1926-1950 : The Pulp Era and the Golden Age

- Beginnings to 1926

- 1926-1950 : The Pulp Era and the Golden Age

- 1950 to 1965 : The Rise of the SF Paperback

- 1965-1980 : The New Wave

- 1980-2010 : SF Goes "Punk"

- 2010 - Present : The Expanding Universe of SF

- Tropes & Themes

- Fairy Tales

- Ghost Stories

- Weird Tales

- Research, Awards, and Societies

- Africa & the African Diaspora

- Asian & AAPI

- Latin American, Latinx, and Caribbean

- MENA & Middle Eastern-American

- Scotland, Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand

- Eastern Europe and Russia

- Children & Young Adult

- Minnesota SF Authors

1926 to 1950 : The Pulp Era and the Golden Age

In this section.

- General History and Reference

- 1926 to 1950 - Pulp Era & Golden Age

- 1950 to 1965 - Rise of the SF Paperback

- 1965 to 1980 - The New Wave

- 1980 to 2010 - SF Goes "Punk"

- 2010 to Present - The Expanding Universe

- Tropes & Themes in Science Fiction

On this Page

Magazines and primary source documents of sf fandom, anthologies.

- Notable Authors and Books

Online Resources

- Luminist Periodicals Archive - offers access to digitized versions of numerous SFF magazines

- Fancyclopedia - a wiki created by sf fans. Like Wikipedia, this is probably best used either to direct you to a more scholarly secondary source, or as a primary source representing ideas existing in fandom. Fancyclopedia 1 (the original) was published by Jack Speer in 1944, Fancyclopedia 2 by Dick Enney in 1959.

In the General Collection

Amazing Stories , September 1928 cover, featuring the winning entry in a contest to design an emblem for "scientifiction" - http://www.luminist.org/archives/SF/AS.htm

An ad promoting science fiction in Wonder Stories , Nov. 1934

Notable books by authors active 1926 - 1950

Librarian's note: Four of the books listed in this box were written by women speculative fiction authors. Can you tell which ones they are?

- << Previous: Beginnings to 1926

- Next: 1950 to 1965 : The Rise of the SF Paperback >>

- Last Updated: Aug 24, 2023 9:40 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gustavus.edu/sff

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

A Century of Reading: The 10 Books That Defined the 1940s

This series isn't even half way done.

Some books are flashes in the pan, read for entertainment and then left on a bus seat for the next lucky person to pick up and enjoy, forgotten by most after their season has passed. Others stick around, are read and re-read, are taught and discussed. sometimes due to great artistry, sometimes due to luck, and sometimes because they manage to recognize and capture some element of the culture of the time.

In the moment, you often can’t tell which books are which. The Great Gatsby wasn’t a bestseller upon its release, but we now see it as emblematic of a certain American sensibility in the 1920s. Of course, hindsight can also distort the senses; the canon looms and obscures. Still, over the next weeks, we’ll be publishing a list a day, each one attempting to define a discrete decade, starting with the 1900s (as you’ve no doubt guessed by now) and counting down until we get to the (nearly complete) 2010s.

Though the books on these lists need not be American in origin, I am looking for books that evoke some aspect of American life, actual or intellectual, in each decade—a global lens would require a much longer list. And of course, varied and complex as it is, there’s no list that could truly define American life over ten or any number of years, so I do not make any claim on exhaustiveness. I’ve simply selected books that, if read together, would give a fair picture of the landscape of literary culture for that decade—both as it was and as it is remembered. Finally, two process notes: I’ve limited myself to one book for author over the entire 12-part list, so you may see certain works skipped over in favor of others, even if both are important (for instance, I ignored Dubliners in the 1910s so I could include Ulysses in the 1920s), and in the case of translated work, I’ll be using the date of the English translation, for obvious reasons.

For our fifth installment, below you’ll find 10 books that defined the 1940s. (Head here for the 1910s , 20s , and 30s ).

“The day Native Son appeared, American culture was changed forever,” wrote critic Irving Howe in 1963 essay .

No matter how much qualifying the book might later need, it made impossible a repetition of the old lies. In all its crudeness, melodrama, and claustrophobia of vision, Richard Wright’s novel brought out into the open, as no one ever had before, the hatred, fear, and violence that have crippled and may yet destroy our culture.

A blow at the white man, the novel forced him to recognize himself as an oppressor. A blow at the black man, the novel forced him to recognize the cost of his submission. Native Son assaulted the most cherished of American vanities: the hope that the accumulated injustice of the past would bring with it no lasting penalties.

It is a difficult novel, in which a young black man named Bigger Thomas, living in Chicago in the 1930s, who suffocates, decapitates, and burns the body of a white woman, then rapes and kills his own girlfriend after he tells her about it, and eventually is sentenced to death, to which he goes without expressing much remorse. It is an intentional exaggeration meant to expose the racism and oppression that could create such a monster.

“Nobody in America had ever before told a story like this, and had it published,” Louis Menand wrote in The New Yorker . “In three weeks, the book sold two hundred and fifteen thousand copies.” He notes that while Native Son was on the bestseller list, Hattie McDaniel won an Academy Award for her performance as Mammy in Gone with the Wind , making her the first black actor ever to win an Oscar.

“Only in America, the Land of the Free, could such a thing have happened,” the columnist Louella Parsons explained. “The Academy is apparently growing up and so is Hollywood. We are beginning to realize that art has no boundaries and that creed, race, or color must not interfere where credit is due.” She did not go on to note that when McDaniel and her escort arrived at the Coconut Grove for the awards ceremony they found that they had been seated at a special table at the rear of the room, near the kitchen.

Wright quickly became the richest and most famous black author of the era, and is often credited as the “father of black American literature” (though of course black American literature had existed before him). Certainly his influence is undeniable, though the book is not without its critics. In 1949, James Baldwin published an essay entitled “Everybody’s Protest Novel” that criticized Native Son as a protest novel, comparing it to Uncle Tom’s Cabin and concluding that “the failure of the protest novel lies in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power, in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is real and which cannot be transcended.”

Well, it’s an ongoing debate .

McCullers began working on what would become her first novel when she was 19; it would be published when she was only 23. The book, now a classic story of a loose handful of misfits in a small Georgia mill town in the late 1930s, was “something of a sensation” upon its release. “There have been candid-camera studies of American life, past and present. There have been the usual quota of sensitively recorded novels of personal experience,” wrote one reviewer . “But we have waited a long time for a new writer.” And the time was right for one, too. “Turmoil was in the air that fervid summer in 1940,” Rafia Zakaria wrote last year in The Guardian .

Despite Roosevelt’s New Deal, the depredations of the Great Depression had sucked hope from America’s bones, birthed a generation that had only known want and that was sceptical of the possibility of change. In small crowds around newsstands on city corners, uncertain Americans read about the war raging in Europe, but remained unsure as to whether it was “their” problem. Everyone, it seemed, wanted change and no one seemed to know how to hasten it, direct it or evaluate it. In this last sense, and possibly many more, America then was not so different from America now.

Where truth fails, fiction flourishes. In The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter , Carson McCullers . . . distilled all of these consternations, enabling in literature the self-reckoning that had been avoided in reality.

As you see, self-reckoning is already a theme in this decade—though writing from 2018, one wishes we had accomplished it a little more thoroughly.

A bestseller when it was published, Smith’s semi-autobiographical chronicle of a girl growing up in Williamsburg has remained a touchstone for readers young and old. Like The Great Gatsby , it was one of the novels chosen to reprint in paperback and send over to the American troops in WWII. “ A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was perhaps the most popular ASE of them all,” Molly Manning writes in her book about the program, When Books Went to War .

It provided such a vivid account of childhood that many men felt as though Smith were writing about theirs. . . . Smith received a steady stream of letters from men around the world, thanking her for the effect her writing had on them.

“When I first picked up your book, I was down in the dumps, a sad sack, as the boys say,” a sergeant said to Smith. But as he read, “my spirits rose until at the end I found myself chuckling over many of the amusing characters.” He needed the lift that A Tree Grows in Brooklyn had given him. He had felt depressed and lonely for months, and nothing had given him any relief from these feelings, until Smith’s book.

There were more like that. Manning reports that Smith “received approximately four letters a day from servicemen, or about fifteen hundred a year. She responded to almost all of them. . . . “Some letters bring tears to one’s eyes,” she admitted. “I am very much touched by the service men away from home thinking so much of the book. I feel that I have done some good in this world.” Many—and not just the servicemen—would agree.

The Little Prince was an atypical entry in the work of French pilot and writer Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, and initial public reception when it was published (first in the US in concurrent editions in English and French, and then two years later in France) was mixed. “The startling thing, looking again at the first reviews of the book, is that, far from being welcomed as a necessary and beautiful parable, it bewildered and puzzled its readers,” Adam Gopnik wrote in 2014. “Among the early reviewers, only P. L. Travers—who had, with a symmetry that makes the nonbeliever shiver, written an equivalent myth for England in her Mary Poppins books—really grasped the book’s dimensions, or its importance.” People caught on, however, and now it is this work for which he is best remembered. Now it sells 2 million copies a year and is the world’s most translated non-religious book, as well as, not for nothing, possibly the loveliest and most astute children’s book ever written.

If you’ll allow me the cheat, please consider this entry inclusive of A Street in Bronzeville , Gwendoyln Brooks’ first collection of poems, published to wide and enthusiastic acclaim, as well as her second, Annie Allen (1949), which won the Pulitzer Prize, the first time a book by a black writer had ever done so (she was also the first black person to be appointed to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, in 1976). Basically, the 1940s was the decade we first got Gwendolyn Brooks, and she was a new star, and people knew it. “Although the claim of newness in art must always allow for relativity and exceptions,” wrote Brooks’s biographer George E. Kent, “readers of A Street in Bronzeville during the 1940s were aware that it struck a new note in black poetry. Reviews reveal that white readers were impressed by the breadth of its humanistic concerns, while black readers were impressed by its refusal to be “obsessed” with race.” Brooks even became something of a celebrity, and was featured by Mademoiselle as one of their “Ten Young Women of the Year.”

“Babies do not arrive with owner’s manuals,” Spock’s 1998 obituary begins . “But for three generations of American parents, the next best thing was Baby and Child Care .” Indeed, this 1940s child-rearing guide had a massive influence on the way parents in the 40s, 50s, and 60s raised their kids—and even, to some extent, the way those kids raised their kids. Influenced by Sigmund Freud and John Dewey, Spock told parents that it was okay to show their children liberal affection, that it was okay to loosen the reins a bit, and more or less reminded them children were people too. Previous to this book, the prevailing advice had been to show your child as little affection as possible, so they wouldn’t grow up “weak,” and to keep their feeding to a strict schedule. “Trust yourself,” Spock’s book begins. “You know more than you think you do.” It was a huge phenomenon, selling 500,000 copies in the first six months, and over 50 million in total , and was translated into 42 languages. “As soon as it hit the market, it was acclaimed,” Spock’s biographer Lynn Bloom told the BBC. “It was so radical and so different from the child-rearing manuals that preceded it. People wanted the opportunity and the sanction to have children and to love them. And that book did this.” Later, he was criticized for his involvement protesting the Vietnam war, and even blamed by some for the “self indulgence of the ’60s generation,” who had largely been raised in accordance with his guidance.

“I didn’t want to encourage permissiveness, but rather to relax rigidity,” Spock said in response to these charges. “Every once in a while, somebody would say to me, “There’s a perfectly horrible child down the block whose mother tells everybody that he’s being brought up entirely by your book.” But my own children were raised strictly, to be polite and considerate. I guess people read into the book what they wanted to. . . . Maybe my book helped a generation not to be intimidated by adulthood. When I was young, I was always made to assume that I was wrong. Now young people think they might be right and stand up to authority.”

Here’s another book that wasn’t a bestseller in the year of its release, but steadily increased in the public imagination, becoming more and more popular until it became the much parodied children’s book juggernaut that we know and love today, which everyone knows and which has sold over 48 million copies . The book reflected the “here and now” style that Brown had learned from Lucy Sprague Mitchell , who “wanted children to read about the sights and sounds of their own world, unadorned with fantasy. She joked, in fact, that she was introducing the “spinach school” to children’s literature.” Though now critics would suggest that it’s a little more influenced by Gertrude Stein and modernism than spinach. Either way, it’s an enduring classic.

Another book, that with its companion volume, Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953), changed the way Americans thought about themselves, and even the way they lived. It sparked outrage, interest, and acclaim in equal measure when it was originally published, and is a landmark text in the field of human sexuality. “The practice of sexuality was quite varied in the United States before the publication of these books, but it was largely unrecorded, at least by scientists,” wrote John Gagnon, Ph.D., in the New England Journal of Medicine .

Before the late 1940s, the sexual lives of most people were shaped by personal experiments, isolated sexual encounters, uninformed gossip, media sensation, and moral condemnation (not necessarily in that order). The national myth was that most people were obedient to a traditional set of sexual rules and those who were not were relatively rare and defective in morals or willpower.

It was against this background of repression and prurience that Kinsey asserted the right of science to speak about sexual behavior. As a scientist, Kinsey spoke and wrote plainly, using language about sexuality that was rarely heard or read at the time. The facts reported in the book on men’s sexual behavior were at fundamental variance with the myths. Kinsey reported that the practice of masturbation was nearly universal among men (90 percent did it), that homosexual relations were widely experienced (37 percent had done it once), that premarital sexual relations were common (most college men did it), that half of married men had had extramarital sexual relations, and that oral sex was routine in deed if not in public discourse (70 percent of educated husbands said they and their wives had done it).

But it was not only these facts that evoked a powerful negative response from traditional figures in churches, legislatures, and the press. The book also had a strong reformist tone, with Kinsey arguing, completely in the American grain, that progress in dealing with sexual problems could only be made by objectively uncovering the facts of sexual life. That the reported sexual practices of American men differed from moral expectations was (in Kinsey’s interpretation) evidence of the power of sexuality and not a mark of moral decay. The problems associated with sexuality were a consequence of social repression, not inherent to sexuality itself.

Knowledge is power, after all.

When Jackson’s now-legendary short story “The Lottery” was published in The New Yorker on June 26, 1948, readers had no idea what to make of it. They wrote into the magazine by the hundreds—it was, as Jackson’s biographer Ruth Franklin tells us , “the most mail the magazine had ever received in response to a work of fiction.” They were split, Jackson once quipped, into three categories: “bewilderment, speculation, and plain old-fashioned abuse.”

Readers wanted to know where such lotteries were held, and whether they could go and watch; they threatened to cancel their New Yorker subscriptions; they declared the story a piece of trash. If the letters “could be considered to give any accurate cross section of the reading public . . . I would stop writing now,” she concluded.

The collection, published a year later, in which it appeared was the only one to be published during Jackson’s lifetime, though she did publish several novels. “The Lottery” is still taught in high schools and colleges all over the country, and so it is likely her most famous work—a pity, really, as The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle are her real masterpieces. Oh well, good thing we get them all.

Maybe you’ve heard of it. Orwell’s most famous work (maybe it’s just the times, but I rank it above Animal Farm in this respect, despite AF having taught all American schoolchildren what an “allegory” is) was received with impressed if depressed reviews upon its release. “Nineteen Eighty-Four goes through the reader like an east wind, cracking the skin, opening the sores,” wrote V. S. Pritchett in the New Statesman upon the book’s release. “[H]ope has died in Mr Orwell’s wintry mind, and only pain is known. I do not think I have ever read a novel more frightening and depressing; and yet, such are the originality, the suspense, the speed of writing and withering indignation that it is impossible to put down. The faults of Orwell as a writer—monotony, nagging, the lonely schoolboy shambling down the one dispiriting track—are transformed now he rises to a large subject.”

But what’s more impressive is the way it has remained in the cultural consciousness ever since. Big Brother is a TV show. “Orwellian” is in common usage, and of course, the novel has been used time and time again to criticize both Democrats and Republicans , depending on who’s in power.

Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon (1940), Ernest Hemingway, For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), Christina Stead, The Man Who Loved Children (1940), Eugene O’Neill, Long Day’s Journey into Night (1940), James M. Cain, Mildred Pierce (1941), James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), C. S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters (1942), Clarice Lispector, Near to the Wild Heart (1943), Ayn Rand, The Fountainhead (1943), W. Somerset Maugham, The Razor’s Edge (1944), Lillian Smith, Strange Fruit (1944), Tennessee Williams, The Glass Menagerie (1944), Pablo Neruda, Selected Poems (1944, first English translation), Christopher Isherwood, The Berlin Stories (1945), Chester Himes, If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945), Richard Wright, Black Boy (1945) , Henry Green, Loving (1945), Nancy Mitford, The Pursuit of Love (1945), George Orwell, Animal Farm (1945), Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited (1945), E. B. White, Stuart Little (1945), T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets (1945), John Hersey, Hiroshima (1946), Albert Camus, The Stranger (1946, first English translation), Arthur Koestler, Thieves in the Night (1946), Eugene O’Neill, The Iceman Cometh (1946), Robert Penn Warren, All the King’s Men (1946), Mervyn Peake, Titus Groan (1946), W. H. Auden, The Age of Anxiety (1947), Tennessee Williams, A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), Dorothy B. Hughes, In a Lonely Place (1947), Malcolm Lowry, Under the Volcano (1947), James A. Michener, Tales of the South Pacific (1947), Albert Camus, The Plague (1948, first English translation), Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter (1948), Norman Mailer, The Naked and the Dead (1948), Irwin Shaw, The Young Lions (1948), Dodie Smith, I Capture the Castle (1949), Arthur Miller, Death of a Salesman (1949), L. Ron Hubbard, Dianetics (1949), Jean-Paul Sartre, Nausea (1949, first English translation)

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Emily Temple

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

The Moment When Punk Collided With Poetry

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Search Results

Books that shaped the 1940s

Following on from the depression-era doldrums of the 1930s, we move on to the 1940s, a decade shaped by Total War... and an abundance of unforgettable literature.

Next in our series on era-defining novels , we're travelling back to the 1940s. No decade – bar perhaps the 1910s – was more profoundly shaped by a single event, if you can reduce the Second World War to that. The first half of the decade was dominated by the bloodshed of total war; the second by the trauma left in its place.

Despite wartime paper rationing, manpower shortages and censorship, the demand for books never let up. People at home wanted to imagine what it was like on the frontlines, and soldiers on the frontlines wanted to be reminded of home (in fact, demand for battlefield reading material among soldiers was so great, that publishers in the US gave away almost 123 million books to soldiers between 1943 and 1946).

Also, just because there was a war on it didn't mean the social issues of the time – from racial conflict to class division – were put on hold. Far from it. As long as there was paper, ink and a functioning society, writers turned up to chronicle it.

So, without further ado, here are 20 books that helped shape the 1940s, from Richard Wright to Evelyn Waugh, Ayn Rand to Antoine de Saint-Exupéry.

“She wrote 'posh black' at a time when 'broke black' was in vogue" - Diana Evans

The Living is Easy by Dorothy West (1948)

This was one of very few novels published by black women in the 1940s. “[I was] the best-known unknown writer of the time,” Dorothy West once quipped – that time being the Harlem Renaissance and its aftermath.

But it struggled not because it portrayed the lives of black Americans, but because it covered the lives of rich black Americans. “She wrote 'posh black' at a time when 'broke black' was in vogue,” wrote Ordinary People author Diana Evans last August, “and this sits at the heart of her flickering obscurity, a myopia in mainstream culture that struggled to perceive blackness as anything more than one-dimensional.”

It tells the story of Cleo Judson, the patriarchy-busting daughter of Southern sharecroppers, determined to break into Boston's black elite. After marrying the “Black Banana King”, she manipulates her sisters into moving in with her to recreate her old family set up, while bringing up her daughter as a paragon of Boston's black bourgeoisie.

It is a fabulously witty, wise and nuanced satire of class elitism and the bitter legacy of slavery, as well as a feminist masterpiece that – really for the first time in commercial literature – acknowledged the emergence of an African-American middle class.

"[Brooks captured] the tiny incidents that plague the lives of the desperately poor, and the problems of common prejudice" - Richard Wright

Annie Allen by Gwendolyn Brooks (1949)

This profound and moving collection of poems won Gwendolyn Brooks the Pulitzer Prize in 1950, making her the first African American ever to win the award. And it makes this list because, while it is poetry, it is also a gripping narrative.

Split into three parts, the epic masterpiece portrays the life of Annie, an African-American girl growing up in Chicago, as she seeks self-awareness and spiritual fulfilment against the backdrop of the Second World War. It proved a convention-busting work of verse, including one of the most elegant evocations of carpe diem in poetry:

“ Exhaust the little moment. Soon it dies. And be it gash or gold it will not come Again in this identical disguise.”

Among Brooks' biggest fans of the time was Richard Wright (see above), who admired her ability to conjure "the pathos of petty destinies, the whimper of the wounded, the tiny incidents that plague the lives of the desperately poor, and the problems of common prejudice."

Sign up to the Penguin Newsletter

By signing up, I confirm that I'm over 16. To find out what personal data we collect and how we use it, please visit our Privacy Policy

Gary K. Wolfe: Why the 1950s were the golden age of the science fiction novel

Gary K. Wolfe , author of Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature , spoke with us about the recent publication of the two-volume boxed set American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s , which he edited for Library of America.

Library of America: When and how did you first discover the writers and books collected in this set?

Gary K. Wolfe: I’m reasonably certain I first read all these novels before I was fifteen, since I was of the generation that more or less came of age with 1950s science fiction. Something that seems to be a common experience among young science fiction readers, probably true even today, is that we quickly develop a sense not only of our favorite writers, but even our favorite publishers, anthologists, and cover artists. By the time I’d been reading science fiction for a couple of years, I knew that my tastes veered toward Ballantine Books, and those wonderful Richard Powers covers (one appears on the Library of America boxed set and another on the jacket of the 1953–56 volume).

I returned to these authors later when the study of science fiction became part of my academic work, and then again when I was rereading to make the selection for this two-volume set. Obviously, some writers and titles stood up better than others, but I was a bit pleasantly surprised at how well some of them not only stood up, but gained added resonance in perspective.

LOA : What makes the 1950s the golden age of the science fiction novel?

Wolfe: “Golden age” is probably a term that takes on different meanings depending on which generation of science fiction readers you talk to. A fan named Peter Graham is said to have originated the widely-quoted claim that “the golden age of science fiction is twelve,” and there’s probably something to that.

The most common usage, however, came about in the 1950s and pretty clearly reflected the attitudes of readers and writers of that generation. For them, the “golden age” commonly referred to the 1940s, the decade or so after John W. Campbell Jr. assumed the editorship of Astounding Science Fiction , when major writers such as Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, Ray Bradbury, and others developed their reputations.

The 1940s was a crucial time for science fiction’s development, but it wasn’t a golden age of novels . That wasn’t possible until there was a substantial market for them, which didn’t develop until the late 1940s and early 1950s, when major publishers began to take note of the genre, possibly spurred on by the rise of paperback books and the demand for new material. It suddenly became possible for writers—whose previous markets had mostly consisted of pulp short fiction magazines—to conceive a full-length novel and expect to find a publisher for it, and possibly even a decent advance. This was more true in the U.S. than in England, it should be noted, which had a slightly different literary history for science fiction.

LOA : Did you have any principles or guidelines in mind in making the selection of the novels?

Wolfe: We began with some obvious ground rules, such as defining the 50s as the years 1950–59. My own rule was that the novels we selected should be genuine 1950s novels, meaning that they were conceived as novels and not novel-length works assembled from earlier short stories. A number of important SF works published during the 1950s—Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles , Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot , Clifford Simak’s City , James Blish’s The Seedling Stars —were actually story collections with some connective material added, or what are sometimes called “fix-ups.” My feeling was that such works actually represented the short fiction of the 1940s rather than the novels of the 1950s.

Beyond that, we tried to avoid a too-obvious “greatest hits” collection. Instead, we wanted a variety of SF themes and a variety of ways in which these works informed, or were informed by, the ongoing dialogue about science, technology, and society that was quite lively during that decade. It would be possible to fill a volume with nothing but nuclear apocalypse tales, for example, but that could lead to a distorted view of the field, and would ignore the ways in which science fiction grappled with other issues, from religion ( A Case of Conscience ) to consumerism ( The Space Merchants ).

LOA : How would you recommend these novels to readers who aren’t knowledgeable about SF or regular readers of it?

Wolfe: I often hear complaints from non-readers that some modern science fiction can be challenging, or that it’s difficult to find an accessible entry point for reading it. It’s true that SF has developed a sizable number of conventions and tropes that can be confusing to the uninitiated; sometimes even the way SF uses language can be daunting. These novels were written when SF was still in the process of developing those conventions and usages, and thus can provide both a solid grounding and a convenient entry point. I also hear from a number of people who read science fiction when younger, but moved on as they grew older. For them there may be a nostalgia factor—although that really isn’t the point of the collection—and it may provide an opportunity to re-examine some of those youthful passions in perspective.

LOA : How would you recommend the set to avid SF buffs?

Wolfe: Science fiction is old enough by now to have several generations of fans, and in each generation are those who want to “read back” into the history of the field before they began reading it. I’ve met a number of readers, already in their 40s, whose first experiences with the genre date from the cyberpunk period, or William Gibson’s Neuromancer , for example. They might be interested in discovering how Gibson echoes some of Alfred Bester, or what popular contemporary writers like Connie Willis or Neil Gaiman learned from Robert Heinlein or Fritz Leiber. This is one of the reasons I think the website accompanying the set is so important; the essays by contemporary writers offer an opening into the archaeology of the genre, as well of evidence of its continuing influence. In addition, I believe the novels themselves stand out as good SF even by today’s standards.

LOA : Do you have a favorite novel in the collection?

Wolfe: I suppose like most readers, my favorites change over time. The novels which most affected me when younger were probably Sturgeon’s More Than Human and Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow , in that order. I think they hold up pretty well, as does the satire of Pohl and Kornbluth’s The Space Merchants . But the first novel I selected for the collection was Bester’s The Stars My Destination , which is capable of thoroughly surprising readers even today.

The online companion includes appreciations of the novels by contemporary SF novelists—Neil Gaiman, William Gibson, Peter Straub, Connie Willis, and others. How has contemporary writing been influenced by the novels from the 1950s? What’s the relationship between the classic works collected here and the contemporary literary scene?

I think those contemporary writers speak better for themselves than I could hope to, and I’ve already mentioned how some of the tropes and conventions of the field were very much still in development during the 50s. What has surprised and delighted me over the last several years is the degree to which the work of contemporary writers not directly associated with science fiction—Michael Chabon, Jonathan Lethem, Junot Díaz, Margaret Atwood, etc.—has been informed by works like these. We’re beginning to see a broadening of literary ancestry, if you will, expanding beyond the traditional canon to include not only science fiction, but the crime and noir novels which The Library of America has also recognized in earlier collections.

It’s a little harder to gauge the impact of the ideas in these novels in the wider popular culture, but it’s interesting to note how the pastoral post-apocalyptic settings of novels and films like The Hunger Games or new TV series like Revolution echo the setting of Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow , or how satires of the advertising field like Mad Men echo elements of Pohl and Kornbluth’s The Space Merchants .

LOA : What’s the most fun/interesting discovery you made while working on the online companion?

Wolfe: It was surprising to discover how much audio and video material was available, including several radio and TV adaptations of works by our authors (not necessarily the novels themselves) which are on the website. These give a sense of how science fiction appeared in other media during the 50s, of what its pop-culture surfaces looked like in an era before the advent of big-budget CGI epics. For me the most delightful discovery was the wide-ranging audio interview with Leigh Brackett, which is full of fascinating bits about her Hollywood career as well as her SF and mystery writing.

LOA : The novels collected in the set are over half a century old. In what ways are the issues/themes/fears they are grappling with still our own?

Wolfe: Well, nuclear anxiety certainly hasn’t gone away, as the current concerns over Iran indicate. But it’s changed focus; instead of fears of a global nuclear apocalypse waged by superpowers, it’s shifted toward terrorism and rogue regimes. The power of intrusive advertising and media is still a topic of much public discussion, although it too has shifted, from TV and newspapers toward social media and the Internet—something SF more or less missed the ball on (although SF has never been all that successful in actual predictions, which was never what it was about in the first place).

But the most effective science fiction, like the most effective fiction, is about more than topicality, and science fiction can also provide powerful literalized metaphors for more universal concerns such as identity, alienation, even revenge. Budrys’s Who? may be very much a Cold War novel in terms of its topicality, but its central issue asks what our identity is comprised of—how we would prove who we actually are if challenged. Sturgeon’s More Than Human , like much of his fiction, is about how damaged or alienated outsiders can become part of a larger whole. Even Matheson’s The Shrinking Man , perhaps the most fable-like tale in the set, deals quite literally with diminishment and loss, and (spoiler alert, perhaps) offers no scientific or technological “fix” for its protagonist’s existential condition.

LOA : Where should The Library of America go from here? What’s the next logical project?

Wolfe: The 1950s was a crucial and transformative decade in SF, but it would be overreaching to claim that it represents the entirety of the ways in which SF has contributed to American literature. I can see three possible future directions. One involves recognizing the ways in which short fiction was crucial to the development of the genre prior to the 1950s, especially in the 1930s and 1940s (or even earlier), when many of the standard templates and tropes of the genre were developed. Another would be to look at later decades, such as the 1960s and 1970s, when significant new voices—Samuel R. Delany, Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Roger Zelazny, Robert Silverberg, Harlan Ellison, etc.—radically changed the literary tone and ambitions of the genre. A third, obviously, would be to recognize individual writers in the manner in which The Library of America has already recognized Kurt Vonnegut and Philip K. Dick. Two writers who have passed away within the last couple of years and who would be strong candidates are Ray Bradbury and Joanna Russ.

Visit the American Science Fiction companion website for more on 1950s science fiction and these works and writers, including jacket art and photographs, additional stories, author interviews, and new appreciations by Michael Dirda, Neil Gaiman, William Gibson, Nicola Griffith, James Morrow, Tim Powers, Kit Reed, Peter Straub, and Connie Willis.

Related News & Views

Eyeball and Over-Soul: Biographer James Marcus on the Infinitude of Ralph Waldo Emerson

“You Want to Possess the Words”: Jay Parini on Why We Can’t Stop Reading Robert Frost

“Away from the Crowd”: Dan Barry on the Iconoclastic Genius of Jimmy Breslin

Commitment, Capacity, Compassion: Kim E. Nielsen on American Icon Helen Keller

Get 10% off your first Library of America purchase.

Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter and receive a coupon for 10% off your first LOA purchase. Discount offer available for first-time customers only.

A champion of America’s great writers and timeless works, Library of America guides readers in finding and exploring the exceptional writing that reflects the nation’s history and culture.

Benefits of Using Safe Crypto Casinos. One of the most captivating reasons people drift towards Australian casinos online-casino-au com is the promise of anonymity. Safe platforms guarantee that your identity remains a secret. Quick Payouts and Minimal Fees. No one likes waiting, especially for winnings. Safe crypto casinos ensure that payouts are swift and the fees minimal, if not non-existent.

With contributions from donors, Library of America preserves and celebrates a vital part of our cultural heritage for generations to come. Ozwin Casino offers an exciting array of top-notch slots that cater to every player's preferences. From classic fruit machines to cutting-edge video slots, Ozwin Casino Real Money collection has it all. With stunning graphics, immersive themes, and seamless gameplay, these slots deliver an unparalleled gaming experience. Some popular titles include Mega Moolah, Gonzo's Quest, and Starburst, known for their massive jackpots and thrilling bonus features. Ozwin Casino's slots are not just about luck; they offer hours of entertainment and the chance to win big, making it a must-visit for slot enthusiasts.

Advertisement

These are the best new science fiction books to read this June 2024

New books from Adrian Tchaikovsky and the late Michael Crichton (with James Patterson) are among the great new sci-fi novels out this month

By Alison Flood

6 June 2024

Adrian Tchaikovsky’s new novel Service Model is out in June

Joby Sessions/SFX Magazine/Future via Getty Images

There is a wealth of great new science fiction out this June, with all tastes catered for. Want a wild ride to stop a volcano erupting and ending the world? The late Michael Crichton (and his collaborator James Patterson) have it nailed. Want a robot finding his way in the world? Head for Adrian Tchaikovsky and his robot servant Charles. Climate dystopia, poetically rendered? Turn to Roz Dineen.

I am also delighted to see a smattering of space-opera romances, from authors including Emily Hamilton and Rebecca Fraimow – hurrah for some light-heartedness in our sci-fi. That light-heartedness is exactly what we are currently enjoying at the New Scientist Book Club – sign up , and join us in reading Martha Wells’s wonderful All Systems Red , the first in her Murderbot series.

But back to June, where I have also cunningly managed to shoehorn in a mention of one of my top dystopian reads of all time, the criminally overlooked A Boy and his Dog at the End of the World by C.A. Fletcher.

Eruption by Michael Crichton and James Patterson

Crichton, who gave us novels including Jurassic Park (great fun) and State of Fear (less so), died in 2008. Eruption has thus been finished by the prolific James Patterson, taking a break from his usual collaborations with the likes of former US presidents and Dolly Parton.

The premise: the Big Island of Hawaii is about to be hit by a mega volcanic eruption. Unfortunately for the world, the US military chose to hide some very dangerous substances right by the volcano, and if their containers are broken, we are all going to die.

I have found the book silly but fast-moving and fun so far. Emily H. Wilson, our esteemed sci-fi columnist, was less enamoured (“The only mystery is: will these cardboard-thin characters be successful in their logistical efforts?” she wrote , in her May sci-fi column). Perhaps I am just a sucker for rugged volcanologists battling with lava flows, but I am enjoying this absurd quest to save the world for now.

The late Michael Crichton in 2005

dpa picture alliance archive/Alamy

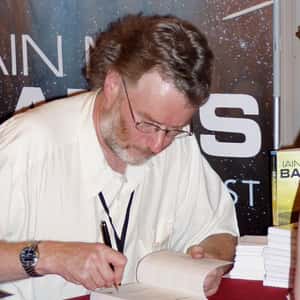

Service Model by Adrian Tchaikovsky

This is the second book of the year from the prolific Tchaikovsky, after Alien Clay . This time we are following the story of robot servant Charles, who is loyal to a fault until a malfunction causes him to murder his owner, and he sets out into the wider world. Tchaikovsky is an author our sci-fi columnist Emily H. Wilson describes as “a huge talent, writing at the peak of his powers”; she loved this latest.

Our writers pick their favourite science fiction books of all time

We asked New Scientist staff to pick their favourite science fiction books. Here are the results, ranging from 19th-century classics to modern day offerings, and from Octavia E. Butler to Iain M. Banks

The Stars Too Fondly by Emily Hamilton

Four twenty-somethings are investigating an old spaceship when the “stupid dark matter engine” starts on its own, and they find themselves on a one-way trip to Proxima Centauri. This is described as a mix of space odyssey and Sapphic romcom, and it sounds like just the sort of light-hearted read I need to read by the pool. The comparisons being made to the brilliant Becky Chambers are particularly appealing.

In Emily Hamilton’s The Stars Too Fondly, the “stupid dark matter engine” starts on its own

Irina Dmitrienko/Alamy

Lady Eve’s Last Con by Rebecca Fraimow

More romance among the stars, as Ruth, a hustler on an interstellar cruise line, is out to get revenge on Esteban, the man who broke her sister’s heart. Ruth’s plan is to make Esteban fall in love with her, then break his heart right back. But then Ruth meets Esteban’s older sister Sol…

Any Human Power by Manda Scott

I have enjoyed Manda Scott’s novels ever since I discovered her historical Boudica books; her historical spy thriller A Treachery of Spies won the McIlvanney Prize for the Best Scottish Crime Novel of the Year when I judged it in 2019 (it is excellent). So, I am intrigued by this latest offering from a multi-talented writer – a “visionary thriller” that weaves together “myth, technology and radical compassion” according to its publisher, set in a world at breaking point, but where change is coming.

Gate to Kagoshima by Poppy Kuroki

As a die-hard fan of Diana Gabaldon’s time-travelling Outlander books, this is going to fill the gap nicely as I wait for book 10 (come on Diana…). It is 2005 and Isla is researching her Japanese ancestors when she travels from Scotland to Kagoshima. There, she is thrown through a strange white gate by a typhoon, and finds herself in 1877. There is romance with a samurai and decisions about whether or not to remain in the past. Honestly, this is right up my Jamie Fraser -loving alley. And the time-travel means we can definitely claim it as sci-fi – after all, time may only be an illusion created by quantum entanglement …

Lord of the Empty Isles by Jules Arbeaux

Five years after Idrian, an interstellar pirate, ordered a death curse (known as a withering) on Remy’s brother, Remy is out for revenge. He orders a withering on Idrian – only for the curse to rebound onto him. The only way Remy can slow the curse down is to be closer to Idrian, so Remy infiltrates Idrian’s crew, only to discover this pirate is in fact bringing supplies to thousands of innocents. Perhaps he is not as bad as he seems.

Briefly Very Beautiful by Roz Dineen

This is the latest in a stream of recent stories set in a world facing apocalypse that home in on how one individual faces catastrophe – think the Jodie Comer film The End We Start From , based on Megan Hunter’s 2017 novel, or (one of my all-time favourites) A Boy and his Dog at the End of the World by C.A. Fletcher. It is a trope I love and, as a mother of three, I am keen to follow the story of how Cass, raising three children alone in a world on fire as her medic husband serves in a war overseas, sets off from the city for a place of greater safety.

Jodie Comer in The End We Start From

Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy

The Cautious Traveller’s Guide to The Wastelands by Sarah Brooks

At the end of the 19 th century, in a version of our world that is filled with marvels, the only thing that can cross the terrible Wastelands which lie between Beijing and Moscow is the Great Trans-Siberian Express. As a disparate crew step aboard for the journey, something uncontrollable is trying to break in. This is pitched as historical fantasy, but it is also being compared to a “steampunk Solaris ” and a “steampunk Piranesi ” by early readers, so I think there will be plenty here for sci-fi fans to enjoy.

We Speak Through the Mountain by Premee Mohamed

In this follow-up to Mohamed’s The Annual Migration of Clouds , 19-year-old Reid is travelling through Alberta’s Rocky Mountains, which are ravaged by the climate crisis, as she heads for safety at the fictional Howse University. But when she reaches one of the “domes” – the only places where pre-collapse society survives – she discovers that the inhabitants are holding back resources from the rest of humanity.

New Scientist book club

Love reading? Come and join our friendly group of fellow book lovers. Every six weeks, we delve into an exciting new title, with members given free access to extracts from our books, articles from our authors and video interviews.

The Bound Worlds by Megan E.O’Keefe

This is the conclusion to O’Keefe’s Devoured Worlds space-opera trilogy, and her characters Naira and Tarquin have found a new home on Seventh Cradle. Unfortunately for them, Naira is seeing visions of a terrible future, while Tarquin discovers a plot to end the universe.

- Science fiction /

- New Scientist Book Club

Sign up to our weekly newsletter

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Amazonian activist Nemonte Nenquimo tells her story in a potent memoir

Subscriber-only

Michael Crichton and James Patterson's novel Eruption fails to thrill

How to take on ai's challenge to ideas about what can be conscious, popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

Advertisement

How Many Literary A.I. Characters and Plots Do You Know?

By J. D. Biersdorfer June 3, 2024

- Share full article