- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the third dimension. on the dichotomy between speech and writing.

- Faculté des Lettres, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

This paper introduces a more complex and refined articulated view than the classic and simple dichotomy of linguistic production. According to the traditional doxa, what is linguistically articulated is either spoken or written. Forms of written language have previously been considered a secondary representation of spoken forms and, at least in the alphabetic system, the only properly linguistic form. I argue that there exists a third dimension of language, which is internal. This internal form is lexically, phonetically and grammatically articulated, without being spoken in a proper sense, but which can be seen as the pre-condition for both spoken and written production. In other words, linguistic production does not necessarily imply the presence of two interacting speakers (or writers/readers). Production can be seen as the simple effect of an internal activity, and can be described without reduction to spoken or written forms. A consideration of this third dimension in a systematic way could enrich and strengthen approaches to many types of texts and help to productively integrate the traditional schemes adopted in Sociolinguistics, Historical Linguistics, Philology, Literary Criticism, and Pragmatics.

Introduction

Speech in classical linguistic doctrine: saussure.

According to Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale (from here on CLG , 27 Saussure, 1967 ), the act of parole is an individual one, but is realized as the minimum requirement of two “people who are speaking”:

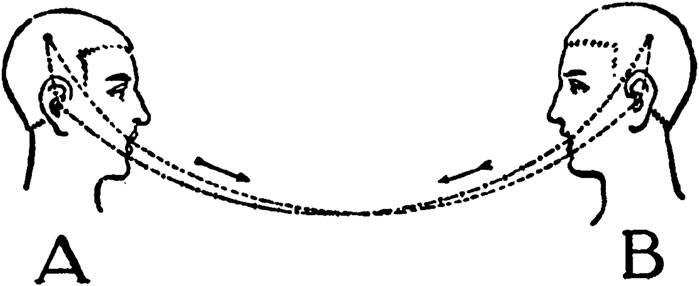

“Pour trouver dans l’ensemble du langage la sphère qui correspond à la langue, il faut se placer devant l’acte individuel qui permet de reconstituer le circuit de la parole. Cet acte suppose au moins deux individus; c’est le minimum exigible pour que le circuit soit complet. Soient donc deux personnes, A et B, qui s’entretiennent”: Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1 . “Le circuit du langage” (from Saussure 1967 : CLG 60).

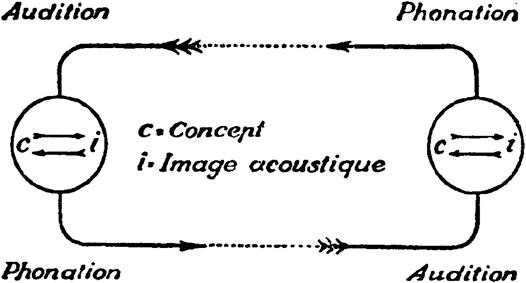

Thus, ideographic systems of writing directly represent the idea of words, and phonetic systems represent their sound ( CLG 47 ss.). Consequently (alphabetic) writing is the representation of the sounds of words, which is manifested in the act of a closed circuit shown above, which assumes two interlocutors. According to Saussure, there exists a connection from a concept to an acoustic image, then to phonation, and finally in inverse order, from a reassociation of the sound to an acoustic image, and then back to the concept Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2 . Phases of saussurean Circuit ( Saussure 1967 : CLG 60).

The written dimension is subordinated, both ontogenetically and phylogenetically, with respect to speech (the latter is identified with language tout court , with an almost imperceptible but crucial deviation). One reads in the CLG 45:

‘Langue et écriture sont deux systèmes de signes distincts; l’unique raison d’être du second est de représenter le premier; l’objet linguistique n’est pas défini par la combinaison du mot écrit et du mot parlé; ce dernier constitue à lui seul cet objet. Mais le mot écrit se mêle si intimement au mot parlé dont il est l’image, qu’il finit par usurper le rôle principal; on en vient à donner autant et plus d’importance à la représentation du signe vocal qu’à ce signe lui-même. C’est comme si l’on croyait que, pour connaître quelqu’un, il vaut mieux regarder sa photographie que son visage ( CLG 45).’

Typical of pre-nineteenth century linguistics was the centrality of writing and written language. Twentieth-century linguistics, then, pushed writing to one side, focusing on the only other perceived dimension, speech. Bloomfield’s famous statement (1935, p. 21) “Writing is not language” became necessarily integrated, in the American structuralist’s perspective, with the notion that the spoken dimension is the only one which duly qualifies as language .

From CLG 45 one can read an entire history of twentieth-century linguistics, which appears to have always taken for granted the dependence of written language on spoken language. This perspective is succinctly highlighted by Martinet, (1972) , p. 70): “a graphic code exists, writing, but apart from this there is no other code: there is language”, obviously referring to speech. There exists almost no twentieth-century treatize which does not define spoken and written language in terms of a dichotomy, and as being the primary (originally, only) and secondary (derived from the first) dimensions of linguistic activity respectively. And there is no work, even among the most recent and attentive studies to questions of the relationship between writing and speech, which does not tend to consider speech simply as the motor of innovation of writing, excluding interference or the role of any other dimension.

Ultimately, according to the model hypothesized by Saussure, spoken language is crucially super-individual. It presupposes at least two individuals, as discussed above. Alphabetic written language is simply a secondary (and often distorted) representation of spoken language, which constitutes the only object of linguistics properly understood (that is, the linguistics of langue , as per the explanation in CLG 38–39).

Twentieth-Century Criticism of the Dichotomy Between Speech and Writing

The dichotomy between speech and writing is discussed at several points during the 20th century. Strictly speaking, this dichotomy is not one of the greatest Saussurian dichotomies, given that Saussure does not theorize it with the same articulation with which he outlines other oppositions, such as those between Langue and Parole, or even Diachrony and Synchrony etc. One reason may be due to the fact that, from his point of view, the written dimension is simply external to the field of linguistics. Already from a structuralist perspective à la Hjelmslev (1966, pp. 131–32), in fact, we see how written and spoken language are not derived from each other, but are simply two manifestations of the same form. In this account, the priority for speech over writing had already been questioned—not from a historical point of view, but from an axiological and epistemological one.

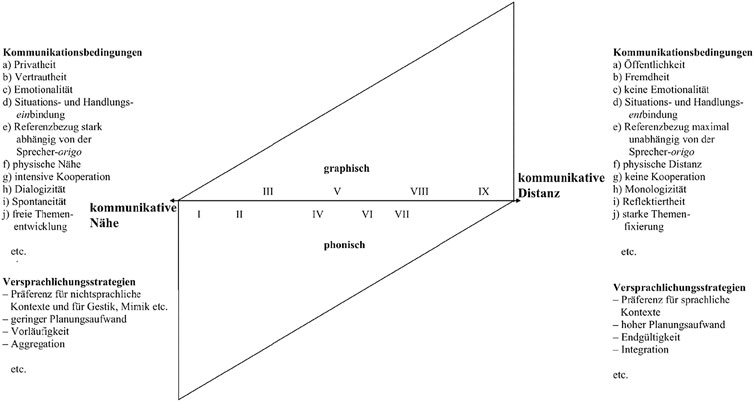

Among the most important discussions, there has been some attempt to refine the sharpness of the boundary between the two fields, highlighting the elements of continuity and, in part, intersection. This is the case of the Koch-Österreicher (1990) model: to the simple distinction between written language vs. spoken language, the two German Romanists oppose a model based on the concepts of distance vs. closeness. These concepts allow, on the one hand, a further realization of the sociolinguistic aspect of situations devoid of writing, and on the other hand, allow us to frame those phenomena which are clearly mixed or hybrid.

The Koch-Österreicher model proposes a scale of distance (and of the quantity of interlocutors included by the single linguistic act) whose minimum value is in fact 1. The conditions of communication are identified, in the first instance, in the Grad der Öffentlichkeit («für den die Zahl der Rezipienten—vom Zweiengespräch bis zum hin zur Massenkommunikation», Koch-Österreicher 2011, p. 7, Italics mine). In short, as in the Saussurian model, there does not appear to be an inferior degree with respect to communication when two are present.

Linguistics in the late 20th century elaborated the concept of diamesic variation (a term invented by Mioni 1983 , extending a series of analogous categories from Coseriu). But it struggled to demonstrate that there exist various “intermediate” positions between these two poles. Apparently, the poles are not united (as instead occurs for similar polarities, such as the classic dimensions of sociolinguistic variation).

A further contribution to overcoming the exclusive and rigid dichotomy between writing and speech was provided by the twentieth-century development of studies on sign language (SL). It is thanks to this line of research and the continued appreciation of SL as an alternative channel to spoken and written language, that traditional expressions such as “spoken or written language” are often substituted with other ones. In recent studies, a trinomial “spoken, signed or written language” (for example, as recently as in Haspelmath 2020 , p. 2) has entered the literature. In short, one finds an all-encompassing category of verbal language in addition to the traditional dichotomy of spoken/written language. This category synthesizes, rather than supersedes, the old contraposition (notwithstanding the distinct nature of signed languages, which can be acquired spontaneously, with respect to writing, and which are the fruit of cultural transmission and learning).

In sum, twentieth-century linguistics approaches the polarities of written vs. spoken language both in a theoretical perspective as well as in a specifically sociolinguistic perspective. Linguistics aimed to overcome this conception as an exclusive dichotomy, placing greater emphasis on those elements of continuity which overlap. This approach was favored also by the emergence of new methodologies of communication. A further contribution to superseding the written/spoken duality was provided by research on sign language: dealing, as it does, with phenomena that cannot be reduced to either category, nor to either one of the polarities.

The Internal Text of G. R. Cardona

Among the few contributions which properly highlighted the linguistic question posed by an internal text, and taking inspiration from both literary and non-literary texts, is the work of Giorgio Raimondo Cardona, (1986 , reprinted Cardona, 1990 ). Published 2 years before his unexpected and premature death, the article deals with “mental text” as an indispensable premise for the production of any oral, but especially written, text.

Let us consider in particular one of the crucial passages of Cardona’s essay: “There is no analytic thread (whatever its itinerary may be) that can be exempt from choosing internal discourse as a point of departure: apart from some cases of automatic writing or trance or similar, no external communicative activity can be disregarded from endophasic, mental and communicative discourse”.

Cardona, (1986) begins from an examination of the literary manifestations of internal speech, bringing to light suggestions from the field of semiotics (and particularly from Lotman et al., 1975 ). He focuses on criticism from genetics and on twentieth-century variationist linguistics, before moving to what he considers a particular type of text, understood as a preparatory and evolving phase that precedes the development in written form, but also its spoken realization. In this way, “the various genres, written and spoken, open up into a natural typology, widening to become waves from the nucleus of internal discourse”.

Another fundamental passage from Cardona consists in recognizing internal discourse (or “interior text”) as the essential absence of a pragmatic dimension, beyond an extreme simplification of syntax (“in one’s thought for oneself, the combination can be reduced to its minimum, the mental nuclei find their minimal linguistic expression. It can, at times, be substituted or integrated by images, as per the manuscripts of Leonardo da Vinci”). Cardona’s examples usefully extend to textual and typological instances that are quite varied.

Cardona’s gifted intuition has been recognized by Italian studies of general linguistics, by history of the Italian language, and literary criticism, which occasionally quote him (among the most important studies, see D’Achille 1990 : 18, who dedicates a note to him). But it has never been explored in full and, in fact, it has not led to any substantial new analysis in the general study of written and spoken language. Significant, for example, is the absence of any reference to him in the best work of German Romance studies in the new century, from Kabatek (2000) to the second edition of Koch-Österreicher (2011) . Furthermore, Cardona’s work does not appear to have been recognized even by contemporary French linguistics, which has, on several occasions, returned to the notions of langage and parole intérieur(e). This includes within the traditional studies of psychology, which we will take up below (exemplary in this regard is Bergounioux 2001 ). In terms of Italian linguistics, which has always been attentive to the social dimension of language and its recent evolution, historians of the Italian language have concentrated mainly on the opposition between spoken and written speech (see, for example, the studies following the work of Giovanni Nencioni, later published in Nencioni 1983 ). Up until now, Cardona’s work has mainly influenced the realm of literature (for example, Bologna 1993 ).

The Perspective From Generative Linguistics

Linguistics in the past few decades has opened up a debate with particular vigor, especially in the field of studies on the origin of language and its biological foundations, which can be summarily characterized by the following two extremes: 1) language is studied primarily as an instrument of communication; 2) language is studied primarily as a form of organization of thought.

Generative grammar resolutely derives from 2) within a theory of externalization. This theory identifies the human specificity of language in its internal, computational (syntactic) capacity (that is, in what Chomsky calls internal language, I-language) and not in the interaction between it and the materiality of phonation. As for the executive function of neurons, the human species shares this aspect with various other animals (hence the computational-syntactic capacity is exclusive of homo, cf. for example Berwick, 2013 ). Generally speaking, only syntactic characteristics are assigned to I-language, dealing as it does with a computational system, that is, with the product of a mental apparatus.

In a partially complementary position, a recent string of neurolinguistic studies (for example, the various works by A. Moro and others, cf. Magrassi et al., 2015a ) has made it possible to observe the cerebral traces of the mental representation of words with the tools from clinical observation. These observations occur not just during the listening phase, but also in the phase of production. In particular, they are visible in those areas of the encephalon that are crucially non acoustic, such as the Broca area. This has highlighted the many affinities between spoken language and “thought language”: the latter showing a great number of elements in common with the former, and thus comprising something similar to what Saussure had already called the acoustic image of words. In short, to summarize with an efficient phrase from Moro, (2016) , p. 89: “when we think without speaking, we are putting the sounds of words in our thoughts”.

One consequence of the theories and of the hypotheses (even though partially divergent) of what we have just said, is that recent linguistics has made it possible to ascertain a certain finding of linguistic dimension preceding phonation, but still within the domain of linguistics. This is due to the fact that we are dealing not only with syntactic structure, which must be considered the specific nucleus of the very faculty of language, but also of a phonetic and phonic consistency at the level of the neural networks. It is, therefore, a recognition in terms of the language(s) involved. In other words, we do not only think linguistically but (at least in certain situations), rather in a very well defined language .

Therefore, not only does language have a foremost interior dimension, if it is understood as the disposition of a computational system with a mainly syntactic nature. It also has a further dimension, still internal, but to which we can add the application of universal syntactic parameters as well as characteristics that are already fully recognizable as single languages. There exists, that is, a form of thought which is already proprerly articulated (and is even formed with features of a single language). At the same time, it is independent from an external, phonic expression in the same language, with which it also maintains strong relations even at the level of activation of neural networks linked to hearing.

The Perspective From Textual Criticism and Philology

The existence of forms of linguistic production that are independent both from acts of phonation, and from writing, has always been known in an intuitive sense. Nevertheless, the received wisdom has tendentially merged or even confused the mental articulation of language with the dimensions of speech or writing. This appears to be the case with metaphors of daily language such as “I said to myself” (in order to introduce the content of a thought that is not truly “said”, but simply “thought”), or “I made a mental note”. Therefore, mental content exists that is linguistically articulated but which is neither “said” nor “written” in the true sense of these two words.

Even literary production has always considered the purely internal dimension of language, and not in a written or spoken sense. Literary works have given conventional representations which, once again, are mainly anchored in the traditional forms of dialogic speech: the form of an (interior) monologue assumes, in an earlier literary tradition, elements such as allocution to oneself (such as those of epic or tragic heroes, as well as lyricists of Antiquity). These elements represent the endophasic dimension as a variation of speech in which two interlocutors coincide.

More recent forms of literary representation (for example, the twentieth-century stream of consciousness) have allowed an attempt to give an autonomous and more “realistic” representation of such phenomena to emerge. In recent years, French stylistique has deepened the literary reflexes of the late nineteenth-century psychological debate (especially in France, as detailed below) on langage intérieur (for example, Rabatel 2001 , Martin-Achard 2016, Dujardin 1931 , Pettenati 1961 ). The in-depth analyses of literary criticism are numerous in these fields (for example, Philippe 2001 ; see above for G. R. Cardona’s particular linguistic view on variationist linguistics).

In fact, the (at least) partially autonomous nature of the articulation of internal language appears to have slipped away attention from its spoken form. This does not mean they are completely separated from it. Little attention has been given to the fact that the same act of writing (autonomous or as a form of copying) assumes a formalized pre-elaboration of content which is not spoken at all, but only thought.

In recent times, before the neurolinguistic studies discussed above, even a particular phenomenon such as transference— via copying—of a written text to another written text has been studied within philology. Indeed, philology has considered phenomena such as the so-called internal dictation in a profound way during the course of the 20th century (see the fundamental studies by Alphonse Dain (1975) ; on “internal pronunciation”, and cf. also Avalle’s considerations 1972, p. 34). Philology has identified a great number of indices which refer us back to a form of “listening” and internal “repetition” (in an acoustic sense) of a graphic sequence that is looked at during the first act of copying, and then transcribed in the second. Most copying errors that are ascribable to defects of internal dictation can be traced, in fact, to the acoustic nature of such repetitions. These errors, nevertheless, do not assume any sound if only that “of thought”, to return to Moro’s expression.

The Perspective From Psychology

The category of internal language was investigated in the fields of psychology and medicine before linguistics. The research conducted by Victor Egger (1881) , Egger (1904) and by Georges Saint-Paul (1892) , Saint-Paul (1904) , Saint-Paul (1912) during the last twenty years of the 19th century, has a seminal value. Partly adopting contrasting perspectives, they proposed establishing a typological classification of the forms of endophasy, bringing attention to the faculty of hearing, as well as visual and verbal-kinetic aspects of the internal representation of language. Until then, these aspects were not able to be investigated simply through introspection (Egger) or interrogation of witnesses (Saint-Paul). The latter originally used a questionnaire which was also distributed among writers; for a historiographical overview of this debate, see Carroy 2001 .

As is general for other aspects of linguistics, the approach that is based on the study of child language acquisition has allowed us to untangle that which appears difficult to ascertain in adults. According to Lev Vygotsky (1966) , whose theory on the formation of internal language is widely accepted, language in the child has a function for social interaction with people in immediate surrounding. Then an egocentric phase from which socialized and internal language derive.

In this particular area, Vygotsky’s model is accepted in substance by Jean Piaget, while reinterpreting the Vygotskian theory. Despite some cases of divergence on specific points, even the theoretician of genetic psychology agrees with the hypothesis that egocentric child language is the point of departure for the development of internal language. This phase is found during a successive stage of development, and is parallel to the formation of “socialized” language (it does not follow it, therefore, and is not derived from it either).

To the general category of internal language can be traced, in the adult, both endophasy (which does not assume any phonation), as well as solitary speech, which represents a sort of medial point between the proper dimension of internal language and the typical dimension of speech in the presence of an interlocutor.

Despite the debates outlined above in the field of psychology, a conspicuous part of general linguistics has continued (more or less) to explicitly reduce internal language to a simplified form of dialogue, in which two interlocutors coincide, through a sort of duplication of the subject into two interlocutors. In fact, this is the point of view, for example, that Benveniste, (1974) , p. 85 adopts in considering monologues: “le monologue procède bien de l’énonciation. Il doit être posé, malgré l’apparence, comme une variété du dialogue, structure fondamentale”. The example is valid also in showing a much broader tendency as well.

Writing, Speech, Thought

In reality, it is obvious that most linguistic production however it is understood occurs outside the domains of speech and writing. Most content that is articulated in a linguistic way (and, as we have said, this includes also mental content, in every sense) happens in thought, and precedes—literally—any form of external expression, spoken or written.

The way in which language is articulated internally is still largely unattainable. This explains the reason why its perception has always turned out to be fleeting, and its nature confused with other forms. If this is the case, the same relationship between spoken language and written language has been read in a completely different way from other graphical cultures (for example, Chinese, on which see the recent paper by Banfi 2020 ). This relationship has been consistently characterized by a tradition that adopts graphemes of a phonetic nature, and in a modern way.

The fact that “thought” language is attainable only in a difficult way, and describable only in specific forms, does not mean that it does not exist, however. The recent findings from neurolinguistics (which have created the possibility of tracing the recognition of syntactic structures independent from sound in the brain, as Moro et al., (2020) have recently done) open up interesting perspectives on the concrete attainability of the thought dimension of language. But even other elements may be involved, in the same sense.

On the other hand, even the spoken dimension of language (obviously much more relevant than written language) has long been neglected, since it is more difficult to obtain with respect to written language. Today, speech can be observed in various forms–that is, one can not only transcribe, but also record. This means that it has been considered as an autonomous subject.

Describing the study of the thought dimension, even in linguistic studies, could have further consequences for the way in which the two tangible dimensions of writing and speech are evaluated. We know that these dimensions influence each other. Koch and Österreicher have produced the most refined model, perhaps, to describe such reciprocal influence. But we do not know exactly what the relationship between them and the third dimension is.

The representation of the relationship that has traditionally been conceived between speech and writing can therefore be summarized in a simple dependency of one on the other:

SPEECH(language proper).↓Writing.(conventional representation of speech, «non language»)

The model proposed by Koch-Österreicher energizes and complicates such a representation, while maintaining an eminently communicative vision of language, shifting the focus toward the notions of Distance and Conception: Figure 3 .

FIGURE 3 . Spoken vs Written Language according to Koch-Österreicher 1990 : 13.

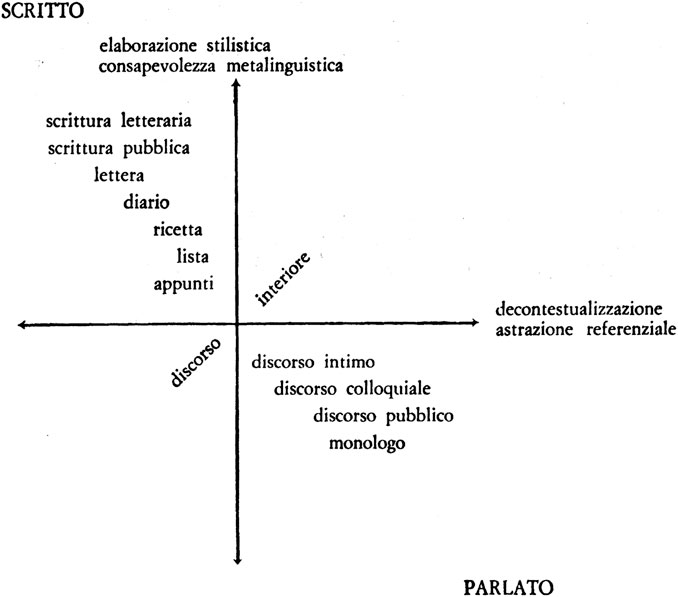

Cardona (1986) adopts an even broader and more articulated perspective, producing a model that is formally similar to those that were being elaborated contemporaneously in various subdisciplines of sociolinguistics (e.x., the well-known Berruto, 1987 model for contemporary Italian): Figure 4 .

FIGURE 4 . Spoken vs Written Language (and Internal Language) according to Cardona (1986) .

The direction which Cardona had already invited us to consider, and which the combined perspectives of twentieth-century psychology and recent neurolinguistics appear to endorse, is that of an even more decisive integration of the internal dimension in the study of language and languages. The consideration of thought language appears to be inevitably presupposed to the study of every manifestation—spoken and written—of language itself. One can attempt to supersede, in this way, the traditional, hierarchical vision which subordinates speech to writing on both of the traditionally identified dimensions. Both appear to be subjected, and equally so, to the overriding internal elaboration of language.

In this sense, the persistent idea loses some force that speech should take on a priority role in both the description and the realization of language. Speech is, certainly, the most direct and immediate projection of thought, but perhaps not the necessary cause of every manifestation of writing. Rather, in many cases it continues from thought in a much more plausible way. Naturally, this does not prevent the idea that the conception (in the sense intended by Koch-Österreicher) of text can bring the dimensions of speech and writing into communication. In the views which we have summarized here, they do not necessarily seem to be in a relationship of direct derivation: Figure 5 .

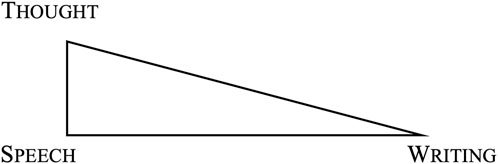

FIGURE 5 . Thought, Speech, Writing according our hypothesis.

In this model, the different length of the sides of the triangle refer to the diverse nature of spoken forms, as is natural, with respect to written forms, which are cultural and obviously negotiated. A possible representation of what is signed in this model would lead to a further derivation from thought which, in turn, would be independent from speech.

Possible Prospects: Outside Literature

Among the consequences of a possible autonomous recognition of the thought dimension of language, distinct from both speech and writing, is the question of overcoming an automatic act which appears to be reasonably widespread. This act derives from the consideration of written language as a simple reflection of speech. If what Saussure had already observed concerning alphabetic writing is irrefutable (that is, that writing reproduces more or less efficiently the phonic substance of words), then it is also true that a certain tendency can be observed to attribute the least characteristic or marginal facts of written language to a pure and simple influence of speech. In the elaboration of writing, thought generally appears much more decisive than speech proper.

In reality, there are various forms of written production that are difficult to interpret as representations of corresponding forms of speech. At the most simple level, what is obvious in forms of elementary text (the oldest attested forms in the development of writing) such as lists, notes, or annotations written down from memory, the writer does not address others but rather him or herself. Nor does the author intend to be comprehended by people other than themselves. It will be useful to recall that among the earliest manifestations of writing throughout history, we find functional texts that are not intended for interpersonal communication, nor for the reproduction of spoken discourse, but rather computational ones. In other words, numbers are born well before letters and “the code of abstract ideas, in particular the numerical code, seems to have performed an essential role from the first stages in the appearance of writing, and perhaps in the very idea that concepts can be written down” ( Deahaene 2009 , p. 211).

In general, a large part of so-called “semi learned” texts, which have been the object of linguistic enquiry for just a short time, present a linguistic phenomenology that is perhaps inappropriately described as being influenced by speech. A much more persuasive explanation of its various phenomena is provided by referring to the dimensions of thought, rather than to speech.

Cardona (1986 , p. 80) has also investigated this aspect of language. With respect to the category of ‘semi learned’ persons, he alludes to the modality of “writing down in real time one’s own mental discourse which is first and foremost—due to a lack of other models—an oral discourse”. But the priority of oral discourse appears dominant here too, when it appears necessary to shift toward a description of the syntax of thought in an analogous way that, for the syntax of speech, has allowed us to re-read and re-interpret such phenomena of written production coherently (as well as programmatic, in this sense, see Sabatini 1990 ).

Therefore, it can be useful to reconsider in a systematic way the elements which in non-literary writing (and particularly in less attentive writing) have traditionally been considered as reflexes of spoken language. One may ask whether these elements should not be removed from that dimension, and restored to the proper category of internal language. To quote one of the clearest and most recent formulations, it is a common opinion that “semi learned writing is characterized by an integral and large adoption of spoken structures” ( Testa 2014 , p. 107). But semi learned writing also includes the modality that Trifone 1986 has aptly described as being “writing for oneself”. Whether this type of writing simply integrates elements and styles of spoken language is a partially equivocal notion. It is created by a lack of features, made up of traits that are external to spoken language, and includes elements both of speech proper and elements of thought. Diaries, notes, jottings made out of necessity or from memory: those who write for themselves (and more so if the writer is semi learned) do not necessarily rely on speech, but more likely draw on the most immediate form of their linguistic production: thought.

Possible Prospects: Literary Production

Some elements of thought language have been highlighted by criticism and literary theory. But in terms of linguistic studies applied to literary texts, there seems to remain a certain reluctance to consider the relationship between internal language and literary language.

We have often borne witness to an appreciation of the literary reproduction of speech. In other words, the mimetic capacity of some literary production (especially in prose) reproduces phenomena in written form that are (or would be) unique to orality. This is one line of research that has been very productive, and which has the merit of clearly distinguishing between that which pertains to the written dimension (studied longer and in a deeper way) from that which does not pertain to it. In a certain sense, it is as if the term “speech” has long indicated simply “that which is not written”, or whatever is different from writing.

Among literary texts that best lend themselves to an indirect investigation of the typical characteristics of thought language, we find also poetic texts (especially lyrical ones), in which the subject, at the center of the discourse, does not seem to have any interlocutor. These texts can be placed alongside prose, discussed above on the flow of conscious and internal monologue.

Economy of syntax, omissions of references to context, advances of the text free from association of ideas without explanations, and a centering of the ego: these are just some of the elements which distinguish a part of poetic production—particularly modern poetry—from more traditional forms of poetic discourse, founded above all on the adoption of canonical verse and metrics. A conspicuous part of modern poetry seems to distinguish itself from prose above all for its privileged link, even if implicit, with the internal dimension of language, that is with thought language.

In this way, some stylistic traits unique to poetry—especially recent poetry—can be explained in an even more persuasive way if one attempts to describe them as outcomes just in terms of thought language. These forms have been typically characterized as an implausible reproduction of speech. This is a parallel, but distinct, step with respect to what we have said above in terms of non-literary writing. In both cases, it is a question of overcoming the almost seamless, and unwarranted, process of assigning phenomena that occur in certain forms of written language only in a marginal and peculiar way to an implausible flow of speech.

In conclusion, the intersection between literary writing and thought language deserves to be explored more attentively, with tools appropriate to linguistics. The noteworthy study of tracing reproducible elements, more or less consciously, of speech in literary texts could also be applied in identifying elements of thought language in literary writing proper. In modern poetry, the ongoing relaxation of the canonical, formal requirements seem to be compensated by an ever stronger relationship between poetry and thought language, whose syntactic, textual, and pragmatic points deserve further definition and articulation.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Avalle, D.-S. (1972). Principi di critica testuale . Padova: Antenore .

Banfi, E. (2020). “ Antinomia ‘parlato’ vs. ‘scritto’ Nel Pensiero Linguistico Cinese ,” in L’antinomia scritto/parlato , a cura di Franca Orletti e Federico Albano Leoni, Città di Castello, ( Emil , 69–87.

Google Scholar

Benveniste, É. (1974). Problèmes de linguistique générale . Paris,: Gallimard .

Bergounioux, G., (2001). (dir.), La parole intérieure , volume thématique de “Langue française” , 132.

Berruto, G. (1987). Sociolinguistica Dell’italiano Contemporaneo . Roma: La Nuova Italia .

Berwick, R. C., Friederici, A. D., Chomsky, N., and Bolhuis, J. J. (2013). Evolution, Brain, and the Nature of Language. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2012.12.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bloomfield, L. (1935). Language . London: Allen & Unwin .

Bologna, C. (1993). Tradizione e fortuna dei classici italiani: Dall'Arcadia al Novecento . Torino: Einaudi .

Cardona, G. R. (1983). “Culture dell'oralità e culture della scrittura,” in (a cura di), Letteratura italiana , II, Produzione e consumo . Editor A. Asor Rosa (Torino: Einaudi ), 25–101.

Cardona, G. R. (1990). I linguaggi del sapere , a cura di C . Bologna, Roma-Bari: Laterza .

Cardona, G. R. (1986). Testo Interiore, Testo Orale, Testo Scritto. «Belfagor» 41/1, 1–12.

Carroy, J. (2001). Bergounioux 2001 , 132, 48–56. doi:10.3406/lfr.2001.6314Le langage intérieur comme miroir du cerveau : une enquête, ses enjeux et ses limites “Langue française”

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

D’Achille, P. (1990). Sintassi del parlato e tradizione scritta della lingua italiana . Roma, Bonacci: Analisi di testi dalle origini al secolo XVIII .

Dain, A. (1975). Les Manuscrits . Paris, Les Belles-Lettres .

Deahaene, S. (2009). I Neuroni Della Lettura , Trad. it . Milano: Raffaello Cortina .

Dujardin, E. (1931). Le Monologue Intérieur . Paris: Messein .

Egger, V. (1881). La parole intérieure. Essai de psychologie descriptive . Paris: Berger-Levrault .

Egger, V. (1904). La parole intérieure. Essai de psychologie descriptive . Paris: Alcan .

Haspelmath, M. (2020). Human Linguisticality and the Building Blocks of Language. Front. Psychol. 10 (January 2020), 3056. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03056)

Hjelmslev, L. (1966). Prolégomènes à une théorie du langage , trad. fr. Paris: Editions de Minuit , 1968–1971.

Kabatek, J. (2000). L’oral et l’écrit – quelques aspects théoriques d’un «nouveau» paradigme dans le canon de la linguistique romane, in W. Dahmen, G. Holtus, J. Kramer, M. Metzeltin, W. Schweickard, and O. Winkelmann (Hrsg.), Kanonbildung in der Romanistik und in den Nachbardisziplinen . Romanistisches Kolloquium XIV , Tübingen, Narr , pp. 305–320.

Koch, P., and Österreicher, W. (1990). “Gesprochene Sprache in der Romania”, in Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch, Tübingen: Niemeye. doi:10.1515/9783111372914

Koch, P., and Österreicher, W. (2011). “Gesprochene Sprache in der Romania,” in Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch , 2 . Ausgabe (Berlin/New York: De Gruyter ). doi:10.1515/9783110252620

Lotman, J., Uspenskij, M., and Boris, A. (1975). Editor R. M. Facciani / M. Marzaduri, Tipologia della cultura , Milano: Bompiani.

Magrassi, L., Aromataris, G., Cabrini, A., Annovazzi-Lodi, V., and Moro, A. (2015a). Sound Representation in Higher Language Areas during Language Generation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112 (6), 1868–1873. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418162112

Magrassi, L., Cabrini, A., Aromataris, G., Moro, A., and Annovazzi Lodi, V. (2015b). “Tracking of the Speech Envelope by Neural Activity during Speech Production Is Not Limited to Broca’s Area in the Dominant Frontal Lobe,” in Articolo presentato durante la 37th Annual International Conference of the ieee Engineering (Milano: Medicine and Biology Society ).

Martinet, A. (1972). “Lingua parlata e codice scritto,” in Linguistica e pedagogia , trad. it . Editor J. Martinet (Milano: Angeli ), 69–77.

Mioni, A. M. (1983). Italiano tendenziale: osservazioni su alcuni aspetti della standardizzazione, in Scritti linguistici in onore di Giovan Battista Pellegrini , Pisa: Pacini , 1983, pp. 495–517.

Moro, A. (2016). Le Lingue Impossibili . Milano: Raffello Cortina. doi:10.7551/mitpress/9780262034890.001.0001

CrossRef Full Text

Moro, A., Micera, S., Artoni, F., d'Orio, P., Catricalà, E., Conca, F., et al. (2020). High Gamma Response Tracks Different Syntactic Structures in Homophonous Phrases. «Scientific reports» . https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-64375-9 .

Nencioni, G. (1983). Di Scritto e di Parlato. Discorsi linguistici , Bologna: Zanichelli.

Pettenati, G. (1961). Su alcuni riflessi del discorso interiore nel discorso scritto. «Annali dell’Istituto Universitario Orientale – Sezione Linguistica» 3, 237–246.

Philippe, G. (2001). Le paradoxe énonciatif endophasique et ses premières solutions fictionnelles, in Bergouioux 2001 ( “Langue française” , 132), pp. 96–105. doi:10.3406/lfr.2001.6317

Rabatel, A. (2001). Les représentations de la parole intérieure [Monologue intérieur, discours direct et indirect libres, point de vue], lfr, in Bergounioux 2001 ( “Langue française” , 132), pp. 72–95. doi:10.3406/lfr.2001.6316

Sabatini, F. (1990). Una Lingua Ritrovata: L’italiano Parlato [1990], Ora in Id., L’italiano nel mondo moderno. Saggi scelti dal 1968 al 2009, ed. by V. Coletti, R. Coluccia, P. D’Achille, N. De Blasi, D. Proietti, Napoliet al. 2011, pp. 89–108.

Saint-Paul, G. (1892). Essais sur le langage intérieur . Lyon: Storck .

Saint-Paul, G. (1912). L’art de parler en publique . Paris: L’aphasie et le langage mentalDoin .

Saint-Paul, G. (1904). Le langages intérieur et les paraphasies . Paris: Alcan .

Saussure, F. (1967). Cours de linguistique générale . Paris: Payot .

Testa, Enrico. (2014). L’italiano nascosto. Una storia linguistica e culturale . Torino: Einaudi .

Trifone, P. (1986). “Rec. a E. Mattesini, Il ‘Diario’ in volgare quattrocentesco di Antonio Lotieri di Pisano notaio in Nepi (1985),” in «Studi linguistici italiani» XIIRinascimento dal basso. Il nuovo spazio del volgare tra Quattro e Cinquecento ( Roma: Bulzoni ), 133–142.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1966). Pensiero e linguaggio (con un’appendice di Jean Piaget) . Firenze: Giunti .

Keywords: language, spoken (and written language), written, psycholinguistic, linguistic variation

Citation: Tomasin L (2021) The Third Dimension. On the Dichotomy Between Speech and Writing. Front. Commun. 6:695917. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.695917

Received: 15 April 2021; Accepted: 06 May 2021; Published: 07 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Tomasin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lorenzo Tomasin, [email protected]

Linguistics: Between Orality and Writing

- First Online: 22 August 2022

Cite this chapter

- Harvey J. Graff 2

255 Accesses

In the beginning, there was the Word. The word was spoken. Our knowledge of this comes through writing. It also comes through centuries of translation and conflicting interpretations: a set of relationships that plagues understanding. We have a long legacy of formulaic divides surrounding “ from oral to written or literate” that assume a historical, evolutionary trajectory. The linguistic bases of literacy studies swing from presumption of antecedent to subsequent.

The basic study of language divides over the primacy and determinative influence of either the oral or the written. Linguistics’ roots in religion and foundations in philology are not appreciated.. This is part of their neglect—or the presumption—of history, and of their acceptance of the primacy of a foundational shift from oral to written.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

I first used this rhetorical formulation in Legacies of Literacy (1987). The similarity between this formulation and the opening of the first chapter in Jack Goody’s Logic of Writing ( 1986 ) is entirely coincidental. Yet the differences between our interpretations of this logocentric view are consequential. While I immediately underscore the principal issues and sources of confusion in understanding literacy, Goody turns a complex historical transformation into a formula.

Brockmeier’s version of his “episteme” is deeply ahistorical; none of these formulations pays attention to context. Claims of its novelty are self-serving. Brockmeier and Olson’s use of evidence is flawed. They confuse and conflate social, psychological, and intellectual issues; the general and specific; and literacy and writing. For one critique of Olson and his presumptions, see Halverson, “Olson on literacy” ( 1991 ); Halverson, “Goody and the implosion of the literacy thesis” ( 1992 ).

Brockmeier and Olson’s “Literacy episteme” ( 2009 , 9), declares the existence of a “field” after 1960, but that is not the same as an episteme.

For an interesting perspective, included in one of the testaments to the literacy episteme that, looking to the “future of writing” rather than the past and present, actually argues somewhat contradictorily against part of the accepted narrative, see Harris, “Literacy and the future of writing” ( 2002 ). See also Cook-Gumperz and Gumperz, “From oral to written culture” ( 1981 ), Cook-Gumperz, Social construction , 1986 .

In “Are there linguistic consequences of literacy?” Biber argues: “For example, researchers such as O’Donnell (1974), Olson (1977), and Chafe (1982), argued that written language generally differs from speech in being more structurally complex, elaborated, and/or explicit” (Biber 2009 , 75).

See the classic work of Basil Bernstein, Dell Hymes, Erving Goffman, William Labov, and their students. For introductions, see Bauman and Briggs, “Poetics and performance” ( 1990 ); Goffman, Forms of Talk ( 1981 ); Hymes, “Introduction: Toward ethnographies of communication” ( 1964b ); Koerner, “Toward a history of modern sociolinguistics” ( 1991 ); Labov, Sociolinguistic patterns ( 1972 ); Shuy, “Brief history of American sociolinguistics,” 1990 ; Szwed, “Ethnography of literacy” ( 1981 ).

Finnegan quotes then Director-General of UNESCO, Réné Maheu, speaking of the “apparent association between non-literacy and illiteracy” and asserting “one apparent consequence of nonliteracy: lack of literature” ( 1973 , 113).

Among her major targets are Goody, Ong, Havelock, and McLuhan.

Yugoslavia was the name of the country when Lord published The Singer of Tales in 1960.

See for example, Lord’s chapters on “Writing and Oral Tradition” and “Homer” in Singers of Tales (1960). Compare on one hand with Havelock’s work and on the other hand with Finnegan, Literacy and Orality (1988). See also Lord, Singer of Tales , 2000 ; Parry, Making of Homeric Verse ( 1971 ).

Havelock and Marshall McLuhan were colleagues at the University of Toronto. Among the many influential works on the alphabetization of the brain that acknowledge a debt to Havelock is Maryanne Wolf’s Proust and the Squid ( 2007 ). Havelock’s work, which is pervaded by such slippages, is often cited on the “great transmission” or the revolutionary remaking of the human brain.

Compare with Lord, Singers of Tales (2000, 130) and the extended example of Yugoslav oral poets. Havelock, Literate revolution in Greece ( 1986 , 167), refers to “erosion of orality.”

Finnegan writes: “When we speak of both ‘orality’ and ‘literacy’ one or more of three main aspects may be involved: composition, performance, and transmission over time. These three do not always coincide. Thus it is possible for a work to be oral in performance but not in composition or transmission, or to have a written origin but non-written performance or transmission. These various combinations constitute a background to considering different patterns of transmissions…. The differing patterns do not coincide neatly with the distinction between oral and written traditions” (1988, 171–172). See Heath, Ways with words (1983); Schieffelin and Gilmore, Acquisition of literacy ( 1986 ); Tannen, Spoken and written language ( 1982 ). For examples of inattention to context and oral-literate relationships, see Canagarajah, Translingual practice (2013); Blommaert, Grassroots literacy ( 2008 ).

On letter writing, see popular South American films; Besnier, Literacy, emotion and authority , 1995 ; Cancian, Families, lovers, and their letters ( 2010 ); Henkin, Postal age, 2006 ; Kalman, Writing on the plaza ( 1990 ); Lyons, Readers and society , 2001 ; Lyons, Reading culture and writing practices ( 2008 ); Lyons, Writing culture of ordinary people ( 2013 ); Romani, Postal culture ( 2013 ); Scribner and Cole, Psychology of literacy ( 1981 ); Vincent, Literacy and popular culture ( 1989 ); Vincent, Rise of mass literacy ( 2000 ).

Contrast the Maori’s experience with that in Fiji described by Clammer, Literacy and social change ( 1976 ). According to Tagupa, “Education, change, and assimilation” ( 1981 ), missionaries and officials in Hawai‘i presumed that an alphabetic translation and print led directly to mass literacy and expected that cultural and social changes would necessarily follow.

For Central and South America, Salomon, “How an Andean ‘writing without words’ works” ( 2001 ), Hanks, Converting words ( 2010 ), and Rappaport, Politics of memory ( 1990 ) form excellent case study material. See also Seed, “‘Failing to marvel’” ( 1991 ). For great divide views, see Mignolo, Darker side of the Renaissance ( 1995 ); Boone and Mignolo, Writing without words ( 1994 ). For North America, recent scholarship on native peoples and their encounters with colonists informs the same fundamental questions and follows the same trajectory. Less sophisticated and less influenced by both linguistics and anthropology but now developing rapidly, Native American literacy studies has also been less influenced by scholarship in literacy studies. Regardless, it is ripe for revision with more sustained attention to the interaction between forms of orality and forms of literacy. It also speaks to the importance of non-alphabetic literacies, as Iroquois rituals, Dakota winter counts, and Pacific Northwest coast “totem poles” attest to other forms of record-keeping and a myriad of interactions that demonstrate cross-fertilization between oral and written forms. The colonizers also made deliberate use of cultural misrepresentation as a technique of coercion. Cessions of land, which the indigenous signatories thought of as temporary grants of use rights but which the English enforced as the entire alienation of all property rights, are well-known examples; for a survey, see Calloway, Pen and ink witchcraft ( 2013 ). For case studies, see Bross and Wyss, Early Native literacies ( 2008 ); Cohen, Networked wilderness ( 2010 ); Cushman, Cherokee syllabary ( 2011 ); S. Lyons, X-marks ( 2010 ); Morgan, Bearer of this letter ( 2009 ); Wyss, Writing Indians ( 2000 ).

For example, Canagarajah, Translingual practice ( 2013 ), repeats such catchwords and phrases as translingual, translocal, global, and cosmopolitan. Jan Blommaert’s 2008 pseudo-ethnography, Grassroots literacy , also slights these fundamental linguistic dimensions.

See also Cook-Gumperz and Gumperz, “From oral to written culture” ( 1981 ).

Among the large literature, see Schieffelin and Gilmore, Acquisition of literacy ( 1986 ); Tannen, Spoken and written language ( 1982 ); Heath, Ways with words ( 1983 ); Dyson, Multiple worlds of child writers ( 1989 ); Dyson, “‘Welcome to the jam’” ( 2003 ); Olson and Torrance, Cambridge handbook of literacy ( 2009 ).

For both examples of oppositions and differences, see Tannen, Spoken and written language ( 1982 ). The seminal work of Dell Hymes, Richard Bauman, and especially William Labov merits reopening by students of literacy.

See Street, Literacy in theory and practice ( 1984 ). For more on the debate over the New Literacy Studies, see Chap. 3 .

Bauman, Richard, and Charles L. Briggs. (1990) Poetics and performance as critical perspectives on language and social life. Annual Review of Anthropology 19: 59–88.

Google Scholar

Bauman, Richard, and Joel Sherzer, eds. (1989) Explorations in the ethnography of speaking . 2d ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Besnier, Niko. (1995) Literacy, emotion and authority: Reading and writing on a Polynesian atoll. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, Douglas. (2009). Are there linguistic consequences of literacy? Comparing the potentials of language use in speech and writing. In David R. Olson and Nancy Torrance, eds, The Cambridge handbook of literacy , 75–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert, Jan. (2008) Grassroots literacy: Writing, identity, and voice in Central Africa . Milton Park, Abingdon, and New York: Routledge.

Boone, Elizabeth Hill, and Walter D. Mignolo, eds. (1994) Writing without words: Alternative literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes . Durham: Duke University Press.

Brockmeier, Jens. (2000) Literacy as symbolic space. In Janet Wilde Astington, ed., Minds in the making: Essays in honor of David R. Olson , 43–61. Oxford: Blackwell.

Brockmeier, Jens. (2002) The literacy episteme: The rise and fall of a cultural discourse. In Literacy, narrative and culture , ed. Jens Brockmeier, Min Wang, and David R. Olson, 17–34. Richmond, England: Curzon.

Brockmeier, Jens, and David R. Olson. (2009) The literacy episteme: From Innis to Derrida. In David R. Olson and Nancy Torrance, eds., The Cambridge handbook of literacy , 3–21. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bross, Kristina, and Hilary E. Wyss, eds. (2008) Early Native literacies in New England: A documentary and critical anthology . Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Calloway, Colin G. (2013) Pen and ink witchcraft: Treaties and treaty making in American Indian history . New York: Oxford University Press.

Canagarajah, Suresh. (2013) Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. London: Routledge.

Cancian, Sonia. (2010) Families, lovers, and their letters: Italian postwar migration to Canada. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

Chafe, Wallace, and Deborah Tannen. (1987) The relation between written and spoken language. Annual Review of Anthropology 16: 383–407.

Clammer, J. R. (1976) Literacy and social change: A case study of Fiji . Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Clanchy, Michael T. (1993) From memory to written record: England, 1066–1307 . 2d ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

Cohen, Matt. (2010) The networked wilderness: Communicating in early New England. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Cook-Gumperz, Jenny, and John J. Gumperz. (1981) From oral to written culture: The transition to literacy. In Marcia Farr Whitman, ed., Variation in writing: Functional and linguisticscultural differences , 89–109. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cook-Gumperz, Jenny, ed. (1986) The social construction of literacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cushman, Ellen. (2011) The Cherokee syllabary: Writing the people’s perseverance . Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Dyson, Anne Haas. (1989) Multiple worlds of child writers: Friends learning to write . New York: Teachers College Press.

Dyson, Anne Haas. (2003) “Welcome to the jam: Popular culture, school literacy, and the making of childhoods. Harvard Educational Review 79: 328–361.

Finnegan, Ruth. (1973) Literacy versus non-literacy: The great divide. In Robin Horton and Ruth Finnegan, eds, Modes of Thought , 112–144. London: Faber and Faber.

Finnegan, Ruth. (1988) Literacy and Orality: Studies in the technology of communication . Oxford: Blackwell.

Gee, James Paul. (1986) Orality and literacy: From The Savage Mind to Ways with Words . TESOL Quarterly 20: 719–746.

Gee, James Paul. (1996) Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses . 2d ed. London: Routledge.

Goffman, Erving. (1981) Forms of talk. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goody, Jack. (1986) The logic of writing and the organization of society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goody, Jack, and Ian Watt. (1968) The consequences of literacy. In Jack Goody, ed., Literacy in traditional societies , 27–68. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Graff, Harvey J. (1979) The literacy myth: Literacy and social structure in the nineteenthcentury city . New York: Academic Press.

Graff, Harvey J. (1991) The literacy myth , reprinted with new introduction. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction.

Halverson, John. (1991) Olson on literacy. Language in Society 20: 619–640.

Halverson, John. (1992) Goody and the implosion of the literacy thesis. Man (new series) 27: 301–317.

Hanks, William F. (2010) Converting words: Maya in the age of the cross . Berkeley: University of California Press.

Harris, Roy. (2002) Literacy and the future of writing: An integrational perspective. In Jens Brockmeier, Min Wang, and David R. Olson, eds, Literacy, narrative and culture , 35–66. Richmond, England: Curzon.

Harris, William V. (1989) Ancient literacy . Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Havelock, Eric A. (1963) Preface to Plato . Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Havelock, Eric Alfred. (1973) Prologue to Greek literacy. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati Taft Lectures.

Havelock, Eric Alfred. (1976) Origins of Western literacy. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Havelock, Eric A. (1977) The preliteracy of the Greeks. New Literary History 8: 369–392.

Havelock, Eric A. (1980) The coming of literate communication to Western culture. Journal of Communication 30: 90–99.

Havelock, Eric A. (1982) The literate revolution in Greece and its cultural consequences. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Havelock, Eric A. (1986) The muse learns to write. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Heath, Shirley Brice. (1982) Protean shapes in literacy events: Ever-shifting oral and literate traditions. In Deborah Tannen, ed., Spoken and written language: Exploring orality and literacy , 91–117. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex.

Heath, Shirley Brice. (1983) Ways with words: Language, life, and work in communities and classrooms . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; with new epilogue, 1996.

Heath, Shirley Brice. (1990) The children of Trackton’s children: Spoken and written language in social change. In James W. Stigler, Richard A. Shweder, and Gilbert S. Herdt, eds, Cultural psychology: Essays on comparative human development , 496–510. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heath, Shirley Brice. (2012) Words at work and play: Three decades in family and community life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Henkin, David. (2006) The postal age: The emergence of modern communications in nineteenthcentury America . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hymes, Dell. (1962) The ethnography of speaking. In Thomas Gladwin and William C. Sturtevant, eds, Anthropology and human behavior , 15–53. Washington, D.C: Anthropological Society of Washington.

Hymes, Dell H. (1964a) A perspective for linguistic anthropology. In Sol Tax, ed., Horizons of Anthropology , 92–107. Chicago: Aldine.

Hymes, Dell H. (1964b) Introduction: Toward ethnographies of communication. American Anthropologist 66: 1–34.

Kalman, Judy. (1990) Writing on the plaza: Mediated literacy practice among scribes and clients in Mexico City . Cresskill, N.J: Hampton Press.

Koerner, Konrad. (1991) Toward a history of modern sociolinguistics. American Speech 66: 57–70.

Labov, William. (1972) Sociolinguistic patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Linell, Per. (2005) The written language bias in linguistics: Its nature, origins, and transformations. Milton Park, Abingdon, and New York: Routledge.

Lord, Albert B. (1960) The singer of tales . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Lord, Albert B. (1995) The singer resumes the tale , ed. Mary Louise Lord. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Lord, Albert B. (2000) The singer of tales , 2d ed., ed. Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Lurie, David B. (2011) Realms of literacy: Early Japan and the history of writing . Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Asia Center.

Lyons, Martyn. (2001) Readers and society in nineteenth-century France: Workers, women, peasants . Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Lyons, Martyn. (2008) Reading culture and writing practices in nineteenth-century France . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Lyons, Martyn. (2013) The writing culture of ordinary people in Europe, c. 1860–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lyons, Scott Richard. (2010) X-marks: Native signatures of assent. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

McKenzie, Donald F. (1999) Bibliography and the sociology of texts . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mignolo, Walter. (1995) The darker side of the Renaissance: Literacy, territoriality, and colonialization . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Morgan, Mindy J. (2009) The bearer of this letter: Language ideologies, literacy practices, and the Fort Belknap community . Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Olson, David R. (1994) The world on paper: The conceptual and cognitive implications of writing and reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olson, David R., and Nancy Torrance, eds. 2009. The Cambridge handbook of literacy . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ong, Walter J. (1958) Ramus, method, and the decay of dialogue. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Ong, Walter J. (1967) The presence of the word. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ong, Walter J. (1977) Interfaces of the word . Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Ong, Walter J. (1982) Orality and literacy. London: Methuen.

Parry, Milman. (1971) The making of Homeric verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry , ed. Adam Parry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rappaport, Joanne. (1990) The politics of memory: Native historical interpretation in the Colombian Andes . Durham: Duke University Press, 1990. 1

Rappaport, Joanne, and Tom Cummins. (2012) Beyond the lettered city: Indigenous literacies in the Andes . Durham: Duke University Press.

Romani, Gabriella. (2013) Postal culture: Writing and reading letters in post-unification Italy . Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Säljö, Roger, ed. (1988) The written word: Studies in literate thought and action. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Salomon, Frank. (2001) How an Andean ‘writing without words’ works. Current Anthropology 42: 1–27.

Salomon, Frank, and Mercedes Niño-Murcia. (2011) The lettered mountain: A Peruvian village’s way with writing . Durham, N.C: Duke University Press.

Schieffelin, Bambi B., and Perry Gilmore, eds. (1986) The acquisition of literacy: Ethnographic perspectives. Norwood, N.J: Ablex.

Scribner, Sylvia, and Michael Cole. (1981) The psychology of literacy. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Seed, Patricia. (1991) “Failing to marvel”: Atahualpa’s encounter with the word. Latin American Research Review 26: 7–32.

Shuy, Roger W. (1990) A brief history of American sociolinguistics, 1949–1989. Historiographica Linguistica 17: 183–209.

Street, Brian. (1984) Literacy in theory and practice . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Szwed, John F. (1981) The ethnography of literacy. In Marcia Farr Whiteman, ed., Variation in writing: Functional and linguistic-cultural differences , 13–23. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Tagupa, William E. H. (1981) Education, change, and assimilation in nineteenth century Hawai‘i. Pacific Studies 5: 57–69.

Tannen, Deborah, ed. (1982) Spoken and written language: Exploring orality and literacy . Norwood, N.J.: Ablex.

Thomas, Rosalind. (2009) The origins of western literacy: Literacy in ancient Greece and Rome. In David R. Olson and Nancy Torrance, eds., The Cambridge handbook of literacy , 346–361. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vincent, David. (1989) Literacy and popular culture: England 1750–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vincent, David. (2000) The rise of mass literacy: Reading and writing in modern Europe. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Wolf, Maryanne. (2007) Proust and the squid: The story and science of the reading brain . New York: Harper.

Wyss, Hilary E. (2000) Writing Indians: Literacy, Christianity and Native community in early America . Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of English, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

Harvey J. Graff

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Harvey J. Graff .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Graff, H.J. (2022). Linguistics: Between Orality and Writing. In: Searching for Literacy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96981-3_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96981-3_2

Published : 22 August 2022

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-96980-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-96981-3

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Speech, Writing, and Sign

A Functional View of Linguistic Representation

Linguistics has traditionally dealt with questions about structure—what are the parts of a language and how are they assembled? Naomi Baron adopts a new approach by asking what a human language is used for and how it achieves its goals. She carefully examines what is communicated, why it is important. and how the exchange is accomplished. In the process of this basic redefinition, she fashions a lucid, systematic introduction to the study of linguistics. The initial chapters discuss language as a source and solution to problems of human communication, the various aspects of representation, the definition of human language, and a methodology for the functional analysis of language. The three chapters that follow fully explore this functional perspective for spoken, written, and signed languages, and offer new evidence to demonstrate the effect of social context on linguistic structure. Speech, Writing, and Sign is profusely illustrated with drawings, photographs, and reproductions of artistic examples. Written to be accessible to beginning students, this book will also interest linguistic scholars because of its challenges to current linguistic theory.

Table of Contents

- isbn 978-0-253-05120-2

- publisher Indiana University Press

- publisher place Bloomington, Indiana USA

- restrictions CC-BY-NC-ND

- rights Copyright © Trustees of Indiana University

- rights holder Indiana University Press

- rights territory World

- doi https://doi.org/10.2979/SpeechWritingandSign

We use cookies to analyze our traffic. Please decide if you are willing to accept cookies from our website. You can change this setting anytime in Privacy Settings .

This typology seem very rational, but in fact it is misleading, as rational taxonomies often are. All documented writing systems are a mixture of two or (usually) more of the these categories, and all include a significant phonological aspect. This critique has been most fully develop by John DeFrancis in his book Visible Speech , from which most of the examples below have been taken.

Given the definitions of writing we've given so far, pictographic and ideographic systems would not be included, since they are not ways of "recording language," but rather ways of directly picturing things, events and their relationships. Interestingly, as a matter of empirical fact, it seems that pictographic and ideographic systems have never really developed fully as such. This is not to say that people have never conveyed information with pictures, nor that sets of conventional icons standing for language-independent ideas have never been developed and used. In fact, pictographic and ideographic signs played a central role in the (various) inventions of writing.

However, pictographic or ideographic systems as such have never developed into a form fully capable of conveying unlimited messages from one person to another. Instead, they either remain as limited systems operating within a highly restricted application -- say to keep warehouse records -- or else they develop into a genuine writing system, capable of conveying any linguistic message. In the second case, the process of development into a genuine writing system always involves adding some phonological aspects, in ways we'll describe shortly.

Origins of writing

When they appear in the archeological record about 5,500 years ago, the Sumerians had developed a system of icons inscribed on clay tablets for keeping temple records. A typical example includes icons for "two", "sheep", "temple/house", and the gods "An" and "Inanna". The meaning might be "two sheep received from the temple of An and Inanna", or "two sheep delivered to the temple of An and Inanna", or perhaps something else entirely.

These marks constituted a limited notation system, which in the beginning may only have served to remind the writer of what he had once already known. However, as long as agreed-on standards were obeyed, another person could also read the record in the same way. In this, these were similar to systems for record-keeping, based on symbolic tokens of many sorts, developed over and over again in many cultures over the millennia -- marks on stone or bone, clay figurines, even knots in cords. As civilizations become more complex, record-keeping of this kind becomes increasingly important in order to keep commercial transactions straight. The ability of trained third parties to read such records in a consistent way became increasingly important as systems for mediating or adjudicating disputes in non-violent ways come into use. However, most such systems remained limited in their expressive capacity.

In the case of the Sumerian record-keeping system, two crucial innovations led (over a few hundred years) to a full writing system, capable of expressing anything that could be expressed in the (written) words of the Sumerian language.

The first innovation was the Rebus Principle : if you can't make a picture of something, use a picture of something with the same sound. The first clear example of this is in a tablet from Jemdet Nasr, dated to around 2900 BC, in which a pictograph of a reed ( GI in Sumerian) is used to mean "reimburse" (also pronounced GI ).

The second innovation was what we might call the Charades Principle : if you combine an ambigous or vague picture of the meaning of a word, with a little information about what the word sounds like, you can get a more effective communication of the identity of the word than if you tried to use only imperfect information about meaning, or imperfect information about sound. To give an example from Sumerian, a particular symbol having a meaning something like "leg" might be combined with a symbol pronounced "ba" to give the word GUB "to stand"; the same "leg" symbol, combined with a symbol pronounced "na", gave the word GIN "to go"; and combined with a symbol pronounced "ma", it gave the word TUM "to bring." Thus a Sumerian reader was in effect being asked to play a sort of game of charades : what word has something to do with "leg" and ends in the initial sound of "ba"? -- why of course, that's GUB, "to stand", what else! These combinations became conventionalized, resulting in a system that was presumably somewhat easier to learn to read than to learn to write, but was not very efficient in either direction.

Still, the result was a complete writing system, in which the Sumerians wrote down not just warehouse records, but poems, diplomatic treaties, letters, contracts and judicial decisions, dictionaries, and epic myths.

We can see a modern version of a similar system in Chinese characters. Most characters can be analyzed as containing two elements, one of which provides semantic information, while the other provides phonological information. The following small table (from DeFrancis) illustrates this with a set of four semantic elements crossed with a set of four phonological (or as DeFrancis calls it "phonetic") elements. The numbering of the semantic elements is taken from a standard set of 214 that have been recognized at least since the Kang Xi dictionary of the 18th century, while the numbering of the phonetic elements is taken from a list of 895 compiled by Soothill.

It is clearly inappropriate to call the Chinese system "ideographic", as is sometimes done. Chinese characters refer to morphemes, not ideas. However, to the extent that the pattern in the table above is taken as typical (and DeFrancis claims that about 75% of all Chinese characters work like these examples), Chinese characters are simultaneously a kind of syllabic writing. DeFrancis suggests the term "morpho-syllabic" to describe it.

It can be argued that the degree of phonological information found in the Chinese writing system is not radically different from what is found in English. English spelling usually tells us what the morphemes are, but unless we know in advance, it gives us only imperfect information about pronunciation. We can be sure that "tough" will not be pronounced "congressional" or "halter", but only knowledge of the word itself tells us that it rhymes with "rough" and not with "dough" or "through" or "plough".

Egyptian hieroglyphics also combined pictographic and phonological aspects, often in complicated ways, as the example below suggests. This is the word hememu "humanity". It starts with four symbols denoting the four consonants in the word (the symbol glossed with /u/ is actually /w/). It ends with three semantic determinatives: a seated man, a seated woman, and a set of three lines indicating that multiple entities are referenced.

This approach to writing produced a small number of symbols with simple phonetic values -- Egyptian had 24 simple consonant symbols, shown below -- and led naturally to the development of alphabetic writing systems.

Why pictographic/ideographic writing is not practical

No one has ever developed a full communications system based on pictographic or ideographic principles, although people have often surmised that this would be useful, because it would (or at least could) be universal. The problem is that universality means only that it is equally hard for everyone to develop and learn such a system. If it is feasible to design such a system at all, it is at least very, very difficult. Since everyone already knows at least one ordinary spoken language, practical people will always tend to give up on the ideographic system and start using a written form of their speech, as soon as they can figure out how to do this.

For an amusing myth about this process, check out the story of How the first letter was written , from Rudyard Kipling's Just So Stories .

Why phonological writing is (eventually) practical

It is rather difficult to get enough conscious access to the phonological structure of speech to design an alphabetic writing system, and very few languages have small enough inventories of syllables for a syllabic system to be an easy place to start. More important, the idea of constructing a full writing system (on any basis, phonological or otherwise) is not at all an obvious one.

So writing seems to have started with pictograms for mnemonic aids in record keeping, or as vehicles of insight in divination. As the inventory of signs increases, the possibility arises to begin using some of the signs as rebuses or as phonological/semantic combinations. This is much more efficient than trying to design a new symbol for every word or morpheme. Once this meaning-plus-sound process begins, it can develop into a full (if complex and inefficient) writing system, able to encode any passage in the language. This development seems to have occurred independently at least three times: in the middle east; in China; and in Mexico.

Various other developments are then logically possible. The Chinese (and other cultures influenced by them, including Japan) developed a meaning-plus-sound system based on the syllabic unit. The Mayans did the same. A logical next step is to increase efficiency by doing away with some or all of the meaning-related units, in favor of a consistent syllabary of some sort. Such syllabaries were developed throughout the far east, but in most cases they did not displace the mean-plus-sound elements. Instead they supplemented them for certain uses (such as the encoding of grammatical particles in Japanese) or for certain populations (such as women in some places and periods in China).