Write a Literature Review

- Find This link opens in a new window

Not every source you found should be included in your annotated bibliography or lit review. Only include the most relevant and most important sources.

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Summarize your Sources

Summarize each source: Determine the most important and relevant information from each source, such as the findings, methodology, theories, etc. Consider using an article summary, or study summary to help you organize and summarize your sources.

Paraphrasing

Use your own words, do not copy and paste the abstract. See Purdue Owl's advice on paraphrasing to ensure you don't plagiarize.

Annotated Bibliographies

Annotated bibliographies can help you clearly see and understand the research before diving into organizing and writing your literature review. Although typically part of the "summarize" step of the literature review, annotations should not merely be summaries of each article - they should be critical evaluations of the source, and help determine a source's usefulness for your lit review.

Definition:

A list of citations on a particular topic followed by an evaluation of the source’s argument and other relevant material including its intended audience, sources of evidence, and methodology

- Explore your topic.

- Appraise issues or factors associated with your professional practice and research topic.

- Help you get started with the literature review.

- Think critically about your topic, and the literature.

Steps to Creating an Annotated Bibliography:

- Find Your Sources

- Read Your Sources

- Identify the Most Relevant Sources

- Cite your Sources

- Write Annotations

Annotated Bibliography Resources

- Purdue Owl Guide

- Cornell Annotated Bibliography Guide

- << Previous: Reading

- Next: Synthesize >>

- Last Updated: Oct 11, 2023 12:20 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.goucher.edu/literature-review

Summarizing a Literary Text

A summary of a story presents a critical description of the exhibit that we are analyzing. Close reading allows us to identify the components of a story as we read. In order to summarize a story, we draw on:

- Information about the text using foundational elements and literary elements

- The Plot line or story arc

Foundational Elements

As with any summary, we begin with basic information:

- The title followed by the year originally published in parentheses

- The author’s full name (first and last)

- short story

Literary Elements

- Narrator: Who (or what) is telling the story?

- First person: The narrator is both the storyteller and a character in the story.

- Second person (very rare): The reader is telling the story.

- Third person omniscient: The narrator is not a character in the story but can see and tell the actions and thoughts of all of the characters at all times.

- Third person limited: The narrator is not a character in the story but can see and tell the actions and thoughts of some of the characters at all times.

- Panel: The same story is told from different viewpoints.

- When does the story take place? The setting can be the time period in history or even time of day.

- What is the geographical location of the story, which can be a country, city, street, or even a room or seat at a table?

- What is the atmosphere , such as socio-economic norms and status that influence the prevailing mental and emotional climate of the story?

- What type of beings are the characters (human, animal, robot)?

- Who is the protagonist ( hero/heroine) ? Who is the antagonist (villain) ? Keep in mind that many stories don’t have a clear protagonist and antagonist.

- How does the author express the character’s personality through direct or indirect discourse/dialogue, description, and/or reactions to situations?

- What kind of person is the character?

- Flat: Two-dimensional characters with just one or two traits, who are often stereotypes. They help to move the plot quickly, since the audience easily understands them. Example: nerdy professor

- Flat Round: Complex characters who have complex personalities and display unpredictable behaviors. They are usually the antagonists.

- Dynamic: Characters who develop and experience essential change in personality or the way they see the world. They are usually the protagonists.

- Static: Characters who do not change or develop from the way they are initially presented.

- Chronological / linear time: Begins at the beginning and moves through time to the end.

- Flashback: Begins in the present and goes to the past.

- Circular / anticipatory: Begins in the present, flashes back to the past, and returns to the present at the conclusion.

- Foreshadowing: An indication or indications are provided early in the text that gives clues about what will happen later.

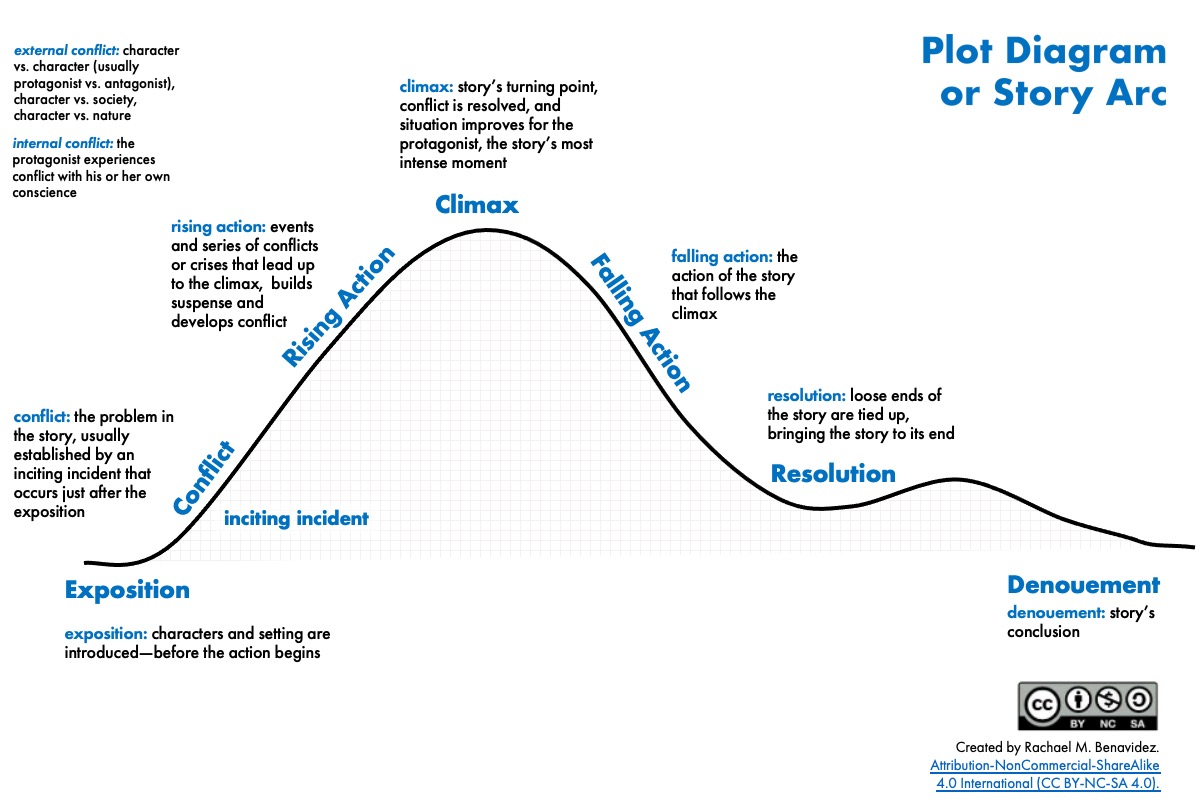

The Plot Line or Story Arc

Our central goal when summarizing a literary work is to describe the narrative plot line or story arc—the events that make up a story.

There are six elements of a plot diagram or traditional story arc, and they often—but not always—occur in a specific order.

- Exposition: The characters and setting are introduced—before the action begins.

- Conflict: The problem in the story, usually established just after the exposition. Characters can experience external and/or internal conflict.

- Rising action: The events and series of conflicts or crises that lead up to the climax, builds suspense and develops conflict.

- Climax: The story’s turning point, conflict is resolved, and situation improves for the protagonist, the story’s most intense moment

- Falling Action: The action of the story that follows the climax

- Resolution and Denouement: The loose ends of the story are tied up, bringing the story to its end (denouement).

The following diagram provides a visual representation of the plot line or story arc.

Reference: Effective Paragraphing , Functions of Sources

Writing About Literature Copyright © by Rachael Benavidez and Kimberley Garcia is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

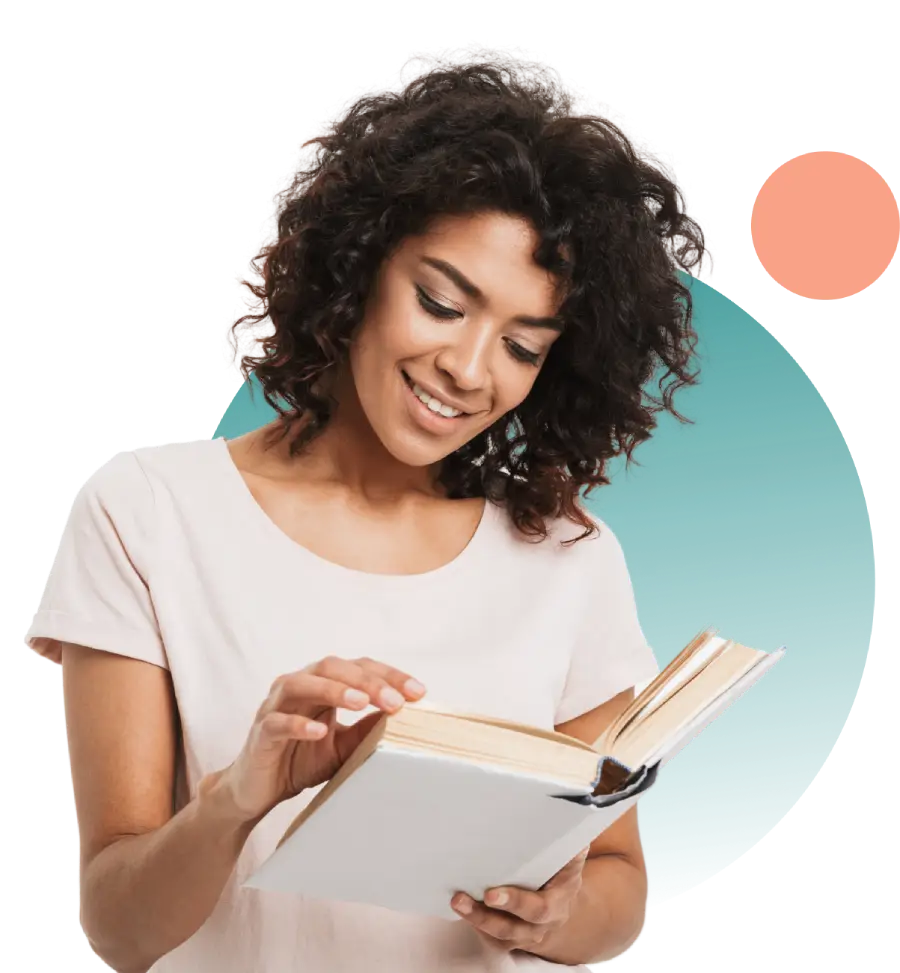

Supercharge your reading experience

Access an extensive library of plot summaries and in-depth study guides written by literary experts..

Lifetime Readers

Customer Satisfaction

Study Guides

Plot Summaries

What's inside a SuperSummary Study Guide:

Analyzing literature can be hard — we make it easy. Get more out of your reading experience.

Detailed plot summary

Refresh your memory of key events and big ideas.

Comprehensive literary analysis

Unlock underlying meaning.

Examination of key figures in the text

Follow character arcs from tragedy to triumph.

Discussion of themes, symbols and motifs

Connect the dots among recurring ideas.

Important quotes with explanations

Appreciate the meaning behind the words.

Essay & discussion topics

Discover writing prompts and conversation starters.

See for yourself.

Check out our sample Study Guides:

Toni Morrison

Malcolm Gladwell

David And Goliath

D. H. Lawrence

Whales Weep Not!

SuperSummary Study Guides are packed with all the information you need to get the most out of the books you read.

Get better results

Over 95% of students surveyed reported that SuperSummary study guides helped them get a better grade!

Save hours of time

Whether you’re preparing for an assignment, a lesson plan, or a book club meeting, SuperSummary saves you hours of time preparing and sorting through inferior free products to find the content you need.

Learn from experts

SuperSummary guides are written by teachers, professors, and literature specialists with multiple years of experience. Meet our writers .

Try risk-free

We’re so sure you’ll love our study materials that they’re backed by a 7-day money-back guarantee .

Subscribe and get instant access to thousands of Study Guides for just $ 3 /month!

Meet some of our talented writers and editors..

SuperSummary recruits experienced teachers and literary experts with advanced literature degrees to analyze and write our guides.

Jenn Brisendine

20-year teaching career across middle and high school English

BA in Secondary Education (English & Dramatic Arts) and an MA in fiction writing

Specializes in writing and editing Middle Grade, YA, and high school-level materials

Elyse Myers

10 years of experience teaching literature courses at the university level and 6 years of experience as a fiction reference librarian

PhD in English Literature

Specializes in classic & contemporary prose fiction , particularly 19th & 20th-century American and British literature

Lily Beaumont

7-years experience in curriculum and study guide development

Joint MA in English and Women's & Gender Studies

Specializes in Victorian literature and feminist theory

Trending titles

Can't find what you're looking for? Suggest a title.

Real results from real customers:, supersummary stood out., the subscription is inexpensive and the guides provide a wealth of information., supersummary has more in-depth analyses., supersummary helps me a lot more than free websites., study guide collections.

Get inspired and find your next read with our carefully curated collections of titles based on common themes, topics, or audiences.

Women's Studies

Fiction with Strong Female Protagonists

Oprah's Book Club Picks

Audio Study Guides

BookTok Books

Summary: Using it Wisely

What this handout is about.

Knowing how to summarize something you have read, seen, or heard is a valuable skill, one you have probably used in many writing assignments. It is important, though, to recognize when you must go beyond describing, explaining, and restating texts and offer a more complex analysis. This handout will help you distinguish between summary and analysis and avoid inappropriate summary in your academic writing.

Is summary a bad thing?

Not necessarily. But it’s important that your keep your assignment and your audience in mind as you write. If your assignment requires an argument with a thesis statement and supporting evidence—as many academic writing assignments do—then you should limit the amount of summary in your paper. You might use summary to provide background, set the stage, or illustrate supporting evidence, but keep it very brief: a few sentences should do the trick. Most of your paper should focus on your argument. (Our handout on argument will help you construct a good one.)

Writing a summary of what you know about your topic before you start drafting your actual paper can sometimes be helpful. If you are unfamiliar with the material you’re analyzing, you may need to summarize what you’ve read in order to understand your reading and get your thoughts in order. Once you figure out what you know about a subject, it’s easier to decide what you want to argue.

You may also want to try some other pre-writing activities that can help you develop your own analysis. Outlining, freewriting, and mapping make it easier to get your thoughts on the page. (Check out our handout on brainstorming for some suggested techniques.)

Why is it so tempting to stick with summary and skip analysis?

Many writers rely too heavily on summary because it is what they can most easily write. If you’re stalled by a difficult writing prompt, summarizing the plot of The Great Gatsby may be more appealing than staring at the computer for three hours and wondering what to say about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s use of color symbolism. After all, the plot is usually the easiest part of a work to understand. Something similar can happen even when what you are writing about has no plot: if you don’t really understand an author’s argument, it might seem easiest to just repeat what he or she said.

To write a more analytical paper, you may need to review the text or film you are writing about, with a focus on the elements that are relevant to your thesis. If possible, carefully consider your writing assignment before reading, viewing, or listening to the material about which you’ll be writing so that your encounter with the material will be more purposeful. (We offer a handout on reading towards writing .)

How do I know if I’m summarizing?

As you read through your essay, ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I stating something that would be obvious to a reader or viewer?

- Does my essay move through the plot, history, or author’s argument in chronological order, or in the exact same order the author used?

- Am I simply describing what happens, where it happens, or whom it happens to?

A “yes” to any of these questions may be a sign that you are summarizing. If you answer yes to the questions below, though, it is a sign that your paper may have more analysis (which is usually a good thing):

- Am I making an original argument about the text?

- Have I arranged my evidence around my own points, rather than just following the author’s or plot’s order?

- Am I explaining why or how an aspect of the text is significant?

Certain phrases are warning signs of summary. Keep an eye out for these:

- “[This essay] is about…”

- “[This book] is the story of…”

- “[This author] writes about…”

- “[This movie] is set in…”

Here’s an example of an introductory paragraph containing unnecessary summary. Sentences that summarize are in italics:

The Great Gatsby is the story of a mysterious millionaire, Jay Gatsby, who lives alone on an island in New York. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote the book, but the narrator is Nick Carraway. Nick is Gatsby’s neighbor, and he chronicles the story of Gatsby and his circle of friends, beginning with his introduction to the strange man and ending with Gatsby’s tragic death. In the story, Nick describes his environment through various colors, including green, white, and grey. Whereas white and grey symbolize false purity and decay respectively, the color green offers a symbol of hope.

Here’s how you might change the paragraph to make it a more effective introduction:

In The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald provides readers with detailed descriptions of the area surrounding East Egg, New York. In fact, Nick Carraway’s narration describes the setting with as much detail as the characters in the book. Nick’s description of the colors in his environment presents the book’s themes, symbolizing significant aspects of the post-World War I era. Whereas white and grey symbolize the false purity and decay of the 1920s, the color green offers a symbol of hope.

This version of the paragraph mentions the book’s title, author, setting, and narrator so that the reader is reminded of the text. And that sounds a lot like summary—but the paragraph quickly moves on to the writer’s own main topic: the setting and its relationship to the main themes of the book. The paragraph then closes with the writer’s specific thesis about the symbolism of white, grey, and green.

How do I write more analytically?

Analysis requires breaking something—like a story, poem, play, theory, or argument—into parts so you can understand how those parts work together to make the whole. Ideally, you should begin to analyze a work as you read or view it instead of waiting until after you’re done—it may help you to jot down some notes as you read. Your notes can be about major themes or ideas you notice, as well as anything that intrigues, puzzles, excites, or irritates you. Remember, analytic writing goes beyond the obvious to discuss questions of how and why—so ask yourself those questions as you read.

The St. Martin’s Handbook (the bulleted material below is quoted from p. 38 of the fifth edition) encourages readers to take the following steps in order to analyze a text:

- Identify evidence that supports or illustrates the main point or theme as well as anything that seems to contradict it.

- Consider the relationship between the words and the visuals in the work. Are they well integrated, or are they sometimes at odds with one another? What functions do the visuals serve? To capture attention? To provide more detailed information or illustration? To appeal to readers’ emotions?

- Decide whether the sources used are trustworthy.

- Identify the work’s underlying assumptions about the subject, as well as any biases it reveals.

Once you have written a draft, some questions you might want to ask yourself about your writing are “What’s my point?” or “What am I arguing in this paper?” If you can’t answer these questions, then you haven’t gone beyond summarizing. You may also want to think about how much of your writing comes from your own ideas or arguments. If you’re only reporting someone else’s ideas, you probably aren’t offering an analysis.

What strategies can help me avoid excessive summary?

- Read the assignment (the prompt) as soon as you get it. Make sure to reread it before you start writing. Go back to your assignment often while you write. (Check out our handout on reading assignments ).

- Formulate an argument (including a good thesis) and be sure that your final draft is structured around it, including aspects of the plot, story, history, background, etc. only as evidence for your argument. (You can refer to our handout on constructing thesis statements ).

- Read critically—imagine having a dialogue with the work you are discussing. What parts do you agree with? What parts do you disagree with? What questions do you have about the work? Does it remind you of other works you’ve seen?

- Make sure you have clear topic sentences that make arguments in support of your thesis statement. (Read our handout on paragraph development if you want to work on writing strong paragraphs).

- Use two different highlighters to mark your paper. With one color, highlight areas of summary or description. With the other, highlight areas of analysis. For many college papers, it’s a good idea to have lots of analysis and minimal summary/description.

- Ask yourself: What part of the essay would be obvious to a reader/viewer of the work being discussed? What parts (words, sentences, paragraphs) of the essay could be deleted without loss? In most cases, your paper should focus on points that are essential and that will be interesting to people who have already read or seen the work you are writing about.

But I’m writing a review! Don’t I have to summarize?

That depends. If you’re writing a critique of a piece of literature, a film, or a dramatic performance, you don’t necessarily need to give away much of the plot. The point is to let readers decide whether they want to enjoy it for themselves. If you do summarize, keep your summary brief and to the point.

Instead of telling your readers that the play, book, or film was “boring,” “interesting,” or “really good,” tell them specifically what parts of the work you’re talking about. It’s also important that you go beyond adjectives and explain how the work achieved its effect (how was it interesting?) and why you think the author/director wanted the audience to react a certain way. (We have a special handout on writing reviews that offers more tips.)

If you’re writing a review of an academic book or article, it may be important for you to summarize the main ideas and give an overview of the organization so your readers can decide whether it is relevant to their specific research interests.

If you are unsure how much (if any) summary a particular assignment requires, ask your instructor for guidance.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Barnet, Sylvan. 2015. A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 11th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Corrigan, Timothy. 2014. A Short Guide to Writing About Film , 9th ed. New York: Pearson.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Zinsser, William. 2001. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction , 6th ed. New York: Quill.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Summarizing, or writing a summary, means giving a concise overview of a text’s main points in your own words. A summary is always much shorter than the original text. There are five key steps that can help you to write a summary: Read the text; Break it down into sections; Identify the key points in each section; Write the summary

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject. Tip. We’ve also compiled a few examples, templates, and sample outlines for you below.

Summarize long texts, documents, articles and papers in 1 click. Get the most important information quickly and easily with the AI summarizer.

Summarize each source: Determine the most important and relevant information from each source, such as the findings, methodology, theories, etc. Consider using an article summary, or study summary to help you organize and summarize your sources.

Our central goal when summarizing a literary work is to describe the narrative plot line or story arc—the events that make up a story. There are six elements of a plot diagram or traditional story arc, and they often—but not always—occur in a specific order.

Access an extensive library of Plot Summaries and in-depth Study Guides written by literary experts.

You might use summary to provide background, set the stage, or illustrate supporting evidence, but keep it very brief: a few sentences should do the trick. Most of your paper should focus on your argument. (Our handout on argument will help you construct a good one.)

How to Write a Summary: 4 Tips for Writing a Good Summary. Written by MasterClass. Last updated: Jun 7, 2021 • 3 min read. With a great summary, you can condense a range of information, giving readers an aggregation of the most important parts of what they’re about to read (or in some cases, see).