This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

From economic wealth to well-being: exploring the importance of happiness economy for sustainable development through systematic literature review

- Open access

- Published: 23 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Shruti Agrawal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1620-9429 1 , 5 ,

- Nidhi Sharma 1 , 5 ,

- Karambir Singh Dhayal ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0000-4330 2 &

- Luca Esposito ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5983-6898 3 , 4

575 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The pursuit of happiness has been an essential goal of individuals and countries throughout history. In the past few years, researchers and academicians have developed a huge interest in the notion of a ‘happiness economy’ that aims to prioritize subjective well-being and life satisfaction over traditional economic indicators such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Over the past few years, many countries have adopted a happiness and well-being-oriented framework to re-design the welfare policies and assess environmental, social, economic, and sustainable progress. Such a policy framework focuses on human and planetary well-being instead of material growth and income. The present study offers a comprehensive summary of the existing studies on the subject, exploring how a happiness economy framework can help achieve sustainable development. For this purpose, a systematic literature review (SLR) summarised 257 research publications from 1995 to 2023. The review yielded five major thematic clusters, namely- (i) Going beyond GDP: Transition towards happiness economy, (ii) Rethinking growth for sustainability and ecological regeneration, (iii) Beyond money and happiness policy, (iv) Health, human capital and wellbeing and (v) Policy push for happiness economy. Furthermore, the study proposes future research directions to help researchers and policymakers build a happiness economy framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins

The costs and benefits of environmental sustainability

Impact of green finance on economic development and environmental quality: a study based on provincial panel data from China

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Happiness is considered the ultimate goal of human beings (Ikeda, 2010 ; Lama, 2012 ). All economic, social, environmental and political human activities are aligned towards achieving this goal. This fundamental pursuit of human life introduces a new scope of research, namely the ‘happiness economy’ (Agrawal and Sharma 2023 ). The happiness economy is an emerging economic domain wherein many countries are working to envision and implement a happiness-oriented framework by expanding how they measure economic success, which includes wellbeing and sustainability (Cook and Davíðsdóttir 2021 ; Forgeard et al., 2011 ). The investigation of happiness, life-satisfaction and subjective well-being has witnessed increasing research interest across the disciplines- from psychology, philosophy, psychiatry, and cognitive neuroscience to sociology, economics and management (Diener 1984 ; Hallberg and Kullenberg, 2019 ).

In the post-Covid era, the world seeks an enormous transformation shift in the public system (Costanza 2020 ). However, public authorities need more time to realize such needs. To experience the ‘policy transformation’ within the coming few years, we require a paradigm shift that helps warm peoples’ hearts and minds. The new economic paradigm can penetrate the policy processes in advanced economies and every part of the world affected by the epidemic with the support of intellectuals, researchers, entrepreneurs and professionals.

OECD ( 2016 ) proposed a well-being economy framework to measure living conditions and people’s well-being. In 2020, developed countries like Finland, New Zealand, Iceland, Scotland and Wales have become members of the Wellbeing Economy Government (WEGo) (Abrar 2021 ). Since then, the network of government and international authorities across the globe has gained a quick momentum concerning an increasing tendency about a growing tendency to concentrate governmental decisions around human well-being rather than wealth and economic growth (Coscieme et al. 2019 ; Costanza et al. 2020 ).

In light of these circumstances, the purpose of this article is to describe the concept of a “happiness economy” or one that seeks to give everyone fair possibilities for growth, a sense of social inclusion, and stability that can support human resilience (Coyne and Boettke 2006 ). It provides a promising route towards improved social well-being and environmental health and is oriented towards serving individuals and communities (Skul’skaya & Shirokova, 2010 ). Moreover, the happiness economy paradigm is a transition from material production and consumption of commodities and services as the only means to economic development towards embracing a considerable variety of economic, social, environmental and subjective well-being dynamics that are considered fundamental contributors to human happiness (Atkinson et al., 2012 ; King et al., 2014 ; Agrawal and Sharma 2023 ). In following so, it reflects the ‘beyond growth’ approach that empathizes with the revised concept of growth, which is not centred around an increase in income or material production; instead it is grounded in the philosophy of achieving greater happiness for more people (Fioramonti et al. 2019a ).

Whereas the other critiques of economic growth emphasize contraction, frugality and deprivation, the happiness economy relies on a cumulative approach of humanity, hope and well-being, with a perceptive to build a ‘forward-looking’ narrative of ways for humans to live a happy and motivated life by inspiring the cumulative actions and encouraging policy-reforms in the measuring growth of an economy (Stucke 2013 ). Agrawal et al. ( 2023a , b ) explore the domain of happiness economics through a review of the various trends coupled with the future directions and highlight why it needs to be supported for a well-managed economic system and a happy society.

In this paper, we define a “happiness economy as an economy that aims to achieve the well-being of individuals in a nation, promoting human happiness, environmental up-gradation, and sustainability. Alternatively, as an economy where the wellbeing of people counts more than the goals of production and income”. Moreover, we have examined the existing body of research on the happiness economy and analyzed the emerging research themes related to rethinking the conventional approach to economic growth. We conclude by discussing how the happiness economy concept has been accepted so far and realizing its importance by triggering policy reforms at the societal level, by outlining potential future directions that might be included into the current national post-growth policies.

Various researchers and experts in the field of happiness economy support the idea that there is a lack of thorough studies related to the concept, definitions, and themes of the happiness economy model in the nations. This gap has motivated us to conduct a SLR in order to identify the evolution in the domain of happiness economy and to identify the emerging themes in this context. Therefore, this present study seeks to offer a holistic outline of the emerging research area of the happiness economy and helps to understand how the happiness economy can accelerate sustainable development. With the following research questions, this study seeks to give an all-encompassing review of this subject.

What is the annual publication trend in this domain and the most contributing authors, journals, countries etc?

Which themes and upcoming research areas are present in this field?

What directions will the happiness economics study field go in the future?

The SCOPUS database was used to achieve the above research objectives. We have selected 257 articles for examination by hand-selecting the pertinent keywords and going over each one. In the methods section, a thorough explanation of the procedures for gathering, reviewing, and selecting documents is provided.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows; A thorough survey of the literature on the happiness economy is provided in Sect. 2 . The research approach employed in the study is presented in Sect. 3 . A thorough data analysis of the research findings is given in Sect. 4 . After discussing the results in Sect. 5 , Sect. 6 suggests areas for further research in this field. The study is summarised with a conclusion in Sect. 7 . Section 8 outlines the study’s limitation.

2 Literature review

The supporters of conventional economic growth proclaim that the material production of goods and services and consumption is vital to enhancing one’s living standards. The statement is true to some degree, mainly in countries of enormous deprivation. Some studies have found significantly less correlation between growth and happiness after fulfilling minimum threshold needs (Easterlin 1995 ; Kahneman and Krueger, 2006 ; Inglehart et al., 2008 ). These studies recommend that rather than concentrating solely on economic growth, governmental policy should give priority to non-economic aspects of human existence above a particular income level. According to some researchers, it is challenging to distinguish between the use and emissions of natural resources and economic growth (absolute decoupling) because of the interdependence between socioeconomic conditions and their biophysical basis (Wiedenhofer et al. 2020 ; Wang and Su, 2019 ; Wu et al., 2018 ). However, a shred of increasing evidence shows that it could be possible for humans to maintain a quality of life and a decent standard of living inside the ecological frontier of the environment, given that a contemporary perspective on the production and use of materials are adopted in conjunction with more fair wealth distribution (Millward-Hopkins et al. 2020 ; Bengtsson et al., 2018 ; Ni et al., 2022 ).

The scholarly discourse and institutional framework on the relationship between happiness and economic progress are synthesised in the happiness economy (Frey and Gallus 2012 ; Sohn, 2010 ; Clark et al., 2016 ; Easterlin, 2015 ; Su et al., 2022 ). From a happiness economy perspective, extreme materialism is unsustainable as it significantly impacts natural resources and hinders social coherence and individuals psychological and physical well-being (Fioramonti et al. 2022a ). Additionally, inequalities within countries have grown, while psychological suffering has increased, especially during accelerated growth (Vicente 2020 ; Galbraith, 2009 ). The modern world is witnessing anxiety, depression, wars, reduction of empathy, climate change, pandemics, loss of social bonds and other psychological disorders (Brahmi et al., 2022 ; Santini et al., 2015 ).

It has been scientifically proven that cordial human relations, care-based activity, voluntary activities and the living environment immensely impact a person’s health and societal well-being (Bowler et al. 2010 ; Keniger et al., 2013 ). Ecological economists demonstrated that free ecosystem services have enhanced human well-being (Fang et al. 2022 ). Social epidemiologists have long argued that an increase in inequalities has a negative influence on society while providing equality tends to improve significant objective ways of well-being, from healthier communities to happier communities, declining hate and crime and enhancing social cohesion, productivity, unity and mutual trust (Aiyar and Ebeke 2020 ; Ferriss, 2010 ).

From moving beyond materialistic growth, the happiness economy promotes, appreciates, and protects the environmental, societal, and human capital contributions that lead to cummalative well-being. In a happiness economy framework, a multidimensional approach is needed to evaluate the level of development based on the environmental parameters, health outcomes, as well as public trust, hope, value-creating education and social bonds (Agrawal and Sharma 2023 ; Bayani et al. 2023 ; Lavrov, 2010 ). Such factors have consistently been excluded from any traditional concept or assessment of economic growth. As a result, countries have promoted more industrial activities that deteriorate the authentic ways of human well-being and, hence, the foundations of economic progress.

An excess of production can create a detrimental effect on climate and people’s health, thereby creating a negative externality for society (Fioramonti et al. 2022b ). Moderation of output may be more efficient and desirable than hyper/over-production, as the former can reduce negative environmental externalities (e.g. waste, climate change) and create positive externalities (e.g. employment of the local resources and community) (Kim et al. 2019 ; Kinman and Jones, 2008 ). Moreover, people can also be productive in other contexts outside of the workplace, such as as volunteers, business owners, artists, friends, or members of the community (Fioramonti et al. 2022a ).

Various scholars and scientific research have established that the essential contributions to happiness in one’s life are made by natural surroundings, green and blue spaces, eco-friendly environment, healthy social relations, spirituality, good health, responsible consumption and value-creating education (Helliwell et al. 2021 ; Francart et al., 2018 ; Armstrong et al., 2016 ; Gilead, 2016 ; Giannetti et al., 2015 ). Unfortunately, existing conventional growth theories have ignored all these significant contributions. For example, GDP considers natural ecosystems as economically helpful only up until they are mined and their products are traded (Carrero et al. 2020 ). The non-market benefits they generate, such as natural fertilization, soil regeneration, climate regulation, clean air and maintenance of biodiversity, are entirely ignored (Boyd 2007 ; Hirschauer et al., 2014). The quality time people spend with their families and communities for leisure, educating future generations and making a healthy communal harmony is regarded meaningless, even in the event that they are important to enhance people’s well-being and, hence, to assist any dimension of economic engagement (Griep et al. 2015 ; Agrawal et al., 2020 ). Similarly, if an economy is focusing on people’s healthy lifestyle (for example, by providing comfortable working hours, improving work-life balance, emphasizing mental health, focusing on healthy food, reducing pollution, and promoting sustainable consumption), it is not considered in sync with the growth paradigm (Roy 2021 ; Scrieciu et al., 2013; Shrivastava and Zsolnai 2022 ; Lauzon et al., 2023 ).

Among the latest reviews, Bayani et al. ( 2023 ) highlight that the economics of happiness helps reduce the country’s financial crime by providing a livelihood that reduces financial delinquency. Chen ( 2023 ) highlights that smart city performance enhances urban happiness by adopting green spaces, reusing and recycling products, and controlling pollution. The study by (Agrawal and Sharma 2023 ) proposed a conceptual framework for a happiness economy to achieve sustainability by going beyond GDP. Similarly, Fioramonti et al. ( 2019b ) explored going beyond GDP for a transition towards a happy and well-being economy. The article by Laurent et al. ( 2022 ) has intensively reviewed the well-being indicators in Rome and proposed a conceptual framework for it.

Table 1 provides a thorough summary of the prior review studies about the happiness economy and its contribution to public policy and sustainable development.

3 Research methodology

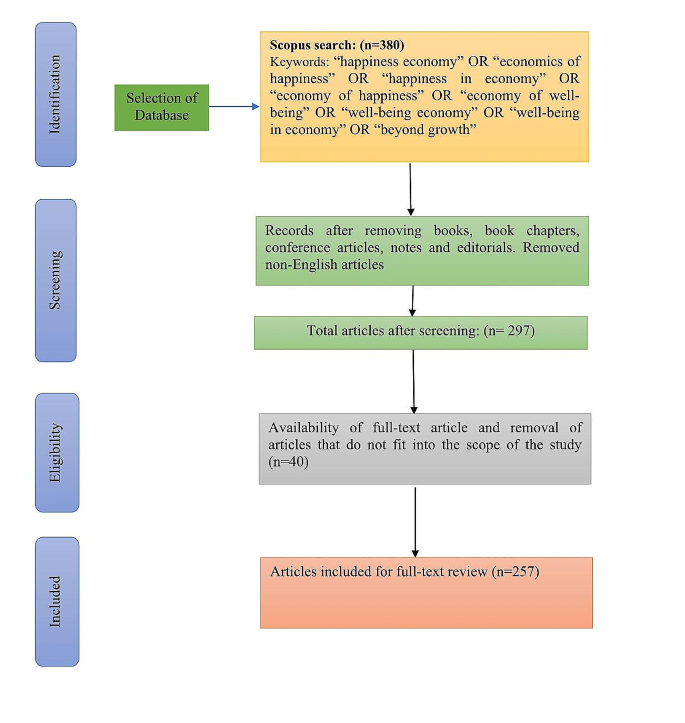

In the current study, we have adopted an integrative review approach of SLR and bibliometric analysis of the academic literature to get a detailed knowledge of the study, which could also help propose future research avenues. The existing scientific production’s qualitative and quantitative context must be incorporated for a conclusive decision. The study by Meredith ( 1993 ) defines that SLR enables an “integrating several different works on the same topic, summarising the common elements, contrasting the differences, and extending the work in some fashion”. In the present study, the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) is applied to perform the SLR to follow systematic and transparent steps for the research methodology, as shown in Fig. 1 . The PRISMA technique includes the identification, screening, eligibility, and exclusion criteria parts of the review process.

Additionally, examples of the data abstraction and analysis processes are provided (Mengist et al. 2020 ; Moher et al., 2015 ). The four main phases of the PRISMA process are eligibility, identification, screening, and data abstraction and analysis. Because the PRISMA technique employs sequential steps to accomplish the study’s purpose, it benefits SLR research. Moreover, the bibliometric analysis helps summarise the existing literature’s bibliographic data and determine the emerging condition of the intellectual structure and developing tendencies in the specified research domain (Dervis 2019 ).

3.1 Identification

The step to conduct the PRISMA is the identification of the relevant keywords to initiate the search for material. Next, search strings for the digital library’s search services are created using the selected keywords. The basic search query is for digital library article titles, keywords, and abstracts. Next, a Boolean AND or OR operator is used to generate the search string (Boolean combinations of the operators may also be used).

There are different search databases to conduct the review studies, such as Scopus, Sage, Web of Science, IEEE, and Google Scholar. Among all the available search databases, we have used the Scopus database to identify the articles; since 84% of the material on Web of Science (WoS) overlaps with Scopus, very few authors have addressed the benefits of adopting Scopus over WoS (Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016 ). Scopus is widely used by academicians and researchers for quantitative analysis (Donthu et al. 2021 ). It is the biggest database of scientific research and contains citations and abstracts from peer-reviewed publications consisting of journal research articles, books and conference articles (Farooque et al., 2019 ; Dhayal et al., 2022 ; Brahmi et al., 2022 ). The following search term was used: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“happiness economy” OR “economics of happiness” OR “happiness in economy” OR “economy of happiness” OR “economy of wellbeing” OR “wellbeing economy” OR “wellbeing in economy” OR “beyond growth”). This process yields 380 artciles in the initial phase.

3.2 Screening

The second phase is completed by all identified articles from the Scopus database obtained from the search string in the identification phase. The publications are either included or excluded throughout the screening process based on the standards established by the authors and with the aid of particular databases. Exclusion and inclusion criteria are shown during the screening phase to identify pertinent articles for the systematic review procedure. The timeline of this study’s selected articles is from 1995 to 2023. The first article related to the research domain was published in 1995. The second criterion for the inclusion includes the types of documents. In the present research, the authors have regarded only peer-reviewed journals and review articles. Other types of articles, such as books, book chapters, conference articles, notes, and editorials, are excluded to maintain the quality of the review. The third inclusion and exclusion criterion is based on language. All the non-English language documents are excluded to avoid translation confusion; hence, only the English language articles are considered for the final review. After the screening process, 297 articles are obtained.

3.3 Eligibility

Articles are manually selected or excluded depending on specific criteria specified by the authors during the eligibility process. During the elimination process, the authors excluded the articles that did not fit into the scope of review after manual screening of the articles. Two hundred fifty-seven articles were selected after the eligibility procedure. These selected articles are carefully reviewed for the study by reviewing the titles, abstracts, and standards from earlier screening processes.

3.4 Data abstraction and analysis

Analysis and abstraction of data are part of the fourth step. Finally, 257 papers were taken into account for final review. After that, the studies are culled to identify pertinent themes and subthemes for the current investigation by thoroughly reviewing each article’s text. An integrative review is a form of study that combines mixed, qualitative, and quantitative research procedures. It is carried out as shown in Fig. 1 . R-studio Bibliometrix and VOSviewer version 1.6.18 were used to evaluate the final study dataset corpus of 257 articles. Since the Bibliometrix software package is a free-source tool programmed in the R language. It is proficient of conducting comprehensive scientific mapping. It also contains several graphical and statistical features with flexible and frequent updates (Agrawal et al. 2023a , b ).

Extraction of articles and selection process

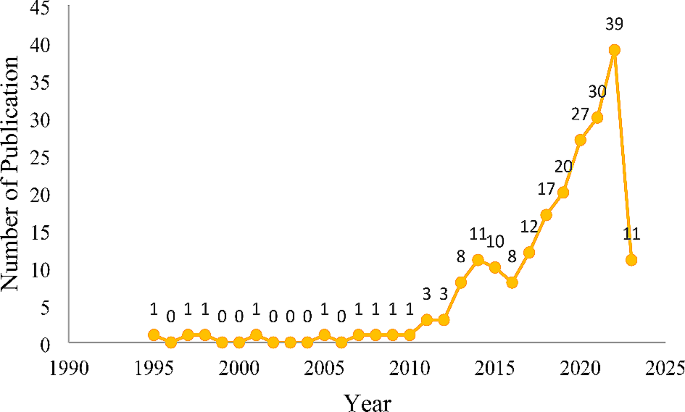

This section provides an answer to the first research question, RQ1, by indicating the main information of corpus data, research publication trends, influential prolific authors, journals, countries and most used keywords, etc. (Refer to Tables 2 , 3 and 4 ) and (Refer to Figs. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 and 6 ).

4.1 Bibliometric analysis

Table 2 shows the relevant information gathered from the publication-related details. It presents the cognitive knowledge of the research area, for instance, details about authors, annual average publication, average citations and collaboration index. By observing the rate of document publishing, the study illustrates how much has already been done and how much remains to be investigated.

The annual publication trend is shown in Fig. 2 . It is reflected that the first article related to happiness in an economy was released in the year 1995 when (Bowling 1995 ) published the article “What things are important in people’s lives? A survey of the public’s judgements to inform scales of health related quality of life” where the article discussed “quality of life” and “happiness” as an essential component of a healthy life. Oswald ( 1997 ) brought the concept of happiness and economics together and raised questions such as “Does money buy happiness?” or “Do you think your children’s lives will be better than your own?”. Eventually, the gross national product of the past year and the coming year’s exchange rate was no longer the concern; instead, happiness as the sublime moment became more accurate (Schyns 1998 ; Easterlin, 2001; Frey and Stutzer, 2005 ). Post-2013, we can see exponential growth in the publication trend, and the reason behind the growth is the report published by the “ Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi” Commission, which has identified limitations of GDP and questioned the metric of wealth, economic and societal progress. The affirmed questions have gained the attention of researchers and organizations, and thus, they have explored the alternatives to GDP. As a result, the “Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development” (OECD) have proposed a wellbeing framework. Some research work has significantly impacted that time, contributing to the immense growth in this research area (Sangha et al. 2015 ; Spruk and Kešeljević, 2015 ; Nunes et al., 2016 ).

Publication trend

Table 3 shows the top prolific journals concerning the topmost publications in the domain of happiness economy for the corpus of 257 articles, namely “International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health”, “Ecological Economics”, “Ecological Indicators”, “Sustainability” and “Journal of Cleaner Production” with 5, 4, 4,4 and 4 articles respectively (Refer to Table 4 ). Moreover, the most influential journals with maximum citations are “Nature Human Behavior”, “Quality of Life Research”, “Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis”, “Journal of Cleaner Production” and “Ecological Economics”, with 219, 205, 186, 154 and 142 citations, respectively. “Journal of Cleaner Production” and “Ecological Economics” are highly prolific and the most influential journals in the happiness economy research domain.

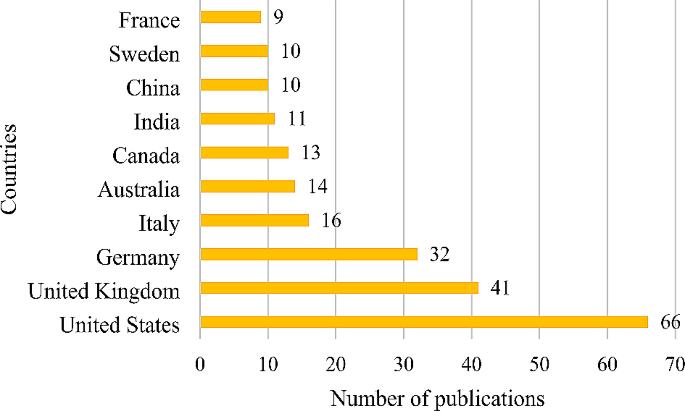

Table 4 shows the most influential authors. Baños, R.M. and Botella, C. are the two most contributing authors with maximum publications. For the maximum number of citations, Zheng G. and Coscieme L. are the topmost authors for their research work. The nations were sorted according to the quantity of publications, and Fig. 3 showed where the top ten countries with the highest number of publications are listed originated. It can be seen from the figure that the United Stated has contributed the maximum publications, 66, followed by the United Kingdom with 41 articles, followed by Germany with 32 articles. It is worth noting that emerging nation such as India and China have also made significant contributions.

Top ten contributing countries

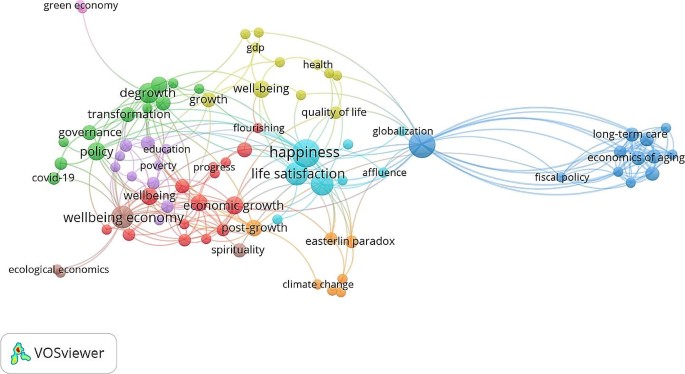

Figure 4 shows semantic network analysis in which the relationships between words in individual texts are performed. In the present study, we have identified word frequency distributions and the co-occurrences of the authors’ keywords in this study. We employed co-word analysis to find repeated keywords or terms in the title, abstract, or body of a text. In Fig. 5 , the circle’s colour represents a particular cluster, and the circle’s radius indicates how frequently the words occur. The size of a keyword’s node indicates how frequently that keyword appears. The arcs connecting the nodes represent their co-occurrence in the same publication. The greater the distance between two nodes, the more often the two terms co-occur. It can be seen that “happiness” is linked with “growth” and “life satisfaction”. The nodes of “green economy”, “ecological economics”, and “climate change” are in a separate cluster that shows they are emerging areas, and future studies can explore the relationship between happiness economy with these keywords.

Co-ocurrance of author’s keyword (Author’s compilation)

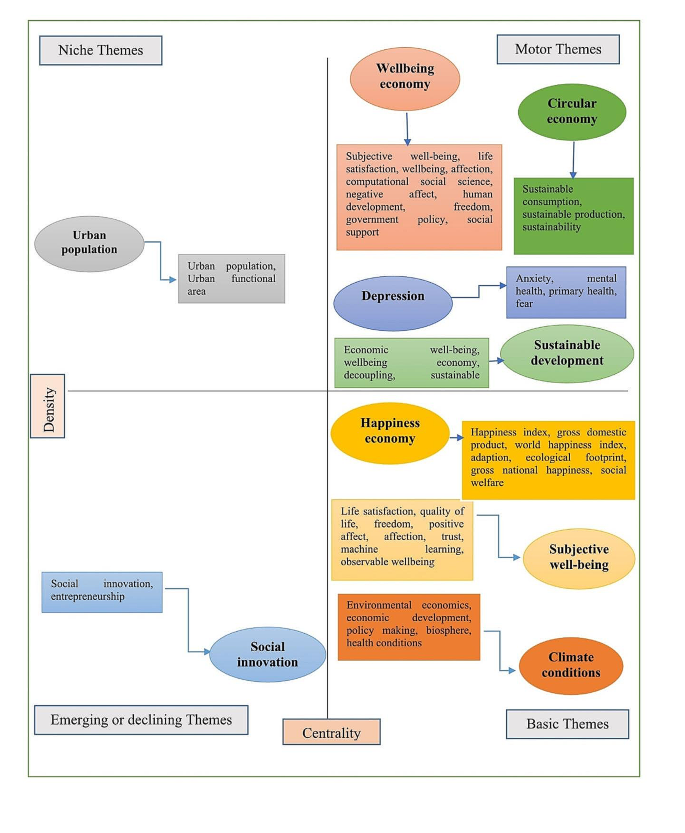

4.2 Thematic map analysis through R studio

The thematic analysis map, as shown in Fig. 5 , displays, beneath the author’s keywords, the visualisation of four distinct topic typologies produced via a biblioshiny interface. The thematic map shows nine themes/clusters under four quadrants segregated in “Callon’s centrality” and “density value”. The degree of interconnectedness between networks is determined by Callon’s centrality, while Callon’s density determines the internal strength of networks. (Chen et al. 2019 ). The rectangular boxes in Fig. 5 represent the subthemes under each topic or cluster that are either directly or indirectly connected to the major themes, based on the available research. In the upper-right quadrant, four themes have appeared, namely “circular economy”, “well-being economy”, “depression”, and “sustainable development”, they fall under the category of motor themes since they are extremely pertinent to the research field, highly repetitious, and well-developed. When compared to other issues with internal linkages but few exterior relations, “urban population” in the upper-left quadrant is seen as a niche concern since it is not as significant. This cluster may have affected the urban population’s happiness (Knickel et al. 2021 ). “Social innovation” is categorised as an emerging or declining subject with low centrality and density, meaning it is peripheral and undeveloped. It is positioned in the lower-left quadrant. Last but not least, the transversal and fundamental themes “happiness economy”, “subjective well-being”, and “climate change” in the lower-right quadrant are seen to be crucial to the happiness economy study field but are still in the early stages of development. As a result, future research must place greater emphasis on the quantitative and qualitative growth of the study area in light of the key themes that have been identified.

Thematic map analysis

4.3 Science mapping through cluster analysis

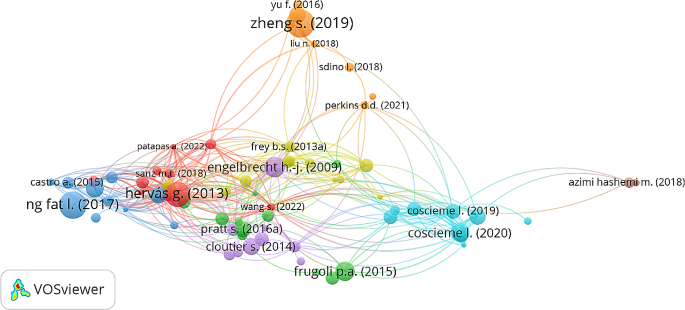

In the study, science mapping was conducted to examine the interrelationship between the research domains that could be intellectual (Aria and Cuccurullo 2017 ; Donthu et al. 2021 ). It includes various techniques, such as co-authorship analysis, co-occurrence analysis, bibliographic coupling, etc. We have used R-Studio for the study’s temporal analysis by cluster analysis. To answer RQ2, the authors have performed a qualitative examination of the emerging cluster themes through the science mapping of the existing research corpus of 257 articles by performing bibliographic coupling of documents. Bibliographic coupling analysis helps identify clusters reflecting the most recent research themes in the happiness economy field to illuminate the field’s current areas of interest.

The visual presentation of science mapping relied on VoSviewer version 1.6.18 (refer to Fig. 6 ). Five significant clusters emerged in this research domain (refer to Table 5 ). Going beyond GDP: Transition towards happiness economy, rethinking growth for sustainability and ecological regeneration, beyond money and happiness policy, health, human capital and wellbeing and Policy-Push for happiness economy. A thorough examination identified cluster analyzes has also assists us in identifying potential future research proposals. (Franceschet 2009 )

4.4 Cluster 1: Going beyond GDP: transition towards happiness economy

It depicts from the green colour circles and nodes, where seven research articles were identified with a common theme of beyond GDP that can be seen in Fig. 6 . Cook and Davíðsdóttir ( 2021 ) investigated the linkages between the alternative measure of the beyond growth approach such as a well-being economy prespective and the SDGs. They proposed a conceptual model of a well-being economy consisting of four capital assets interrelated with SDGs that promote well-being goals and domains. To extend the concept of going beyond GDP, various economic well-being indicators are being aligned with the different economic, environmental, and social dimensions to target the set goals of SDG. It is found that the “Genuine Progress Indicator” (GPI) is consider as the most extensive method that covers the fourteen targets among the seventeen’s SDG’s. Cook et al. ( 2022 ) consider SDGs to represent the classical, neoclassical and growth-based economy model and as an emerging paradigm for a well-being economy. The significance of GDP is more recognized within the goals of sustainable development.

GPI is considered an alternative indicator of economic well-being. On this basis, excess consumption of high-quality energy will expand macro-economic activity, which GDP measures. For such, a conceptual exploration of the study is conducted on how pursuing “Sustainable Energy Development” (SED) that can increase the GPI results. As the study’s outcome, according to the GPI, SED will have a significant advantage in implementing energy and environment policy and will also contribute to the advancement of social and economic well-being. Coscieme et al. ( 2020a ) explored the connection between the unconditional growth of GDP and SDG. The author considered that policy coherence for sustainable development should lessen the damaging effects of cyclic manufacturing on the ecosystem. Thus, the services considered free of charge in the GDP model should be valued as a component of society. Generally, such services include ecosystem services and a myriad of “economic” functions like rainfall and carbon sequestration. To work for SDG 8, defined by the “United Nations Sustainable Development Goals” (UNSDGs), a higher GDP growth rate would eventually make it more difficult to achieve environmental targets and lessen inequality. Various guidelines were proposed to select alternative variables for SDG-8 to enhance coherence among all the SDG and other policies for sustainability.

Fioramonti et al. ( 2019a ) state their focus is to go beyond GDP toward a well-being economy rather than material output with the help of convergence reforms in policies and economic shifts. To achieve the SDG through protecting the environment, promoting equality, equitable development and sharing economy. The authors have developed the Sustainable Well-Being Index (SWBI) to consolidate the “Beyond GDP” streams as a metric of well-being matched with the objectives to achieve SDG. The indicators of well-being for an economy have enough possibility to connect current transformations in the economic policies and the economy that, generally, GDP is unable to capture.

Fioramonti et al. ( 2022a ) investigate the critical features of the Wellbeing Economy (WE), including its various parameters like work, technology, and productivity. Posting a WE framework that works for mainstream post-growth policy at the national and international levels was the study’s primary goal. The authors have focused on building a society that promotes well-being that should be empowering, adaptable, and integrative. A well-being economic model should develop new tools and indicators to monitor all ecological and human well-being contributors. A multidimensional approach including critical components for a well-being economy was proposed that creates value to re-focus on economic, societal, personal, and natural aspects. Rubio-Mozos et al. ( 2019 ) conducted in-depth interviews with Fourth Sector business leaders, entrepreneurs, and academicians to investigate the function of small and medium-sized businesses and the pressing need to update the economic model using a new measure in line with UN2030. They have proposed a network from “limits to growth” to a “sustainable well-being economy”.

4.5 Cluster 2: Rethinking growth for sustainability and ecological regeneration

Figure 6 depicts it from blue circles and nodes, wherein four papers were identified. Knickel et al. ( 2021 ) proposed an analytical approach by collecting the data from 11 European areas to examine the existing conditions, difficulties, and anticipated routes forward. The goal of the study is to define the many ideas of a sustainable well-being economy and territorial development plans that adhere to the fundamental characteristics of a well-being economy. A transition from a conventional economic viewpoint to a broader view of sustainable well-being is centred on regional development plans and shifting rural-urban interactions.

Pillay ( 2020 ) investigates the new theories of de-growth, ecosocialism, well-being and happiness economy to break the barriers of traditional economic debates by investigating ways to commercialise and subjugate the state to a society in line with non-human nature. The significant indicator of Gross National Happiness (GNH) is an alternative working indicator of development; thus, the Chinese wall between Buddha and Marx has been built. They questioned the perspective of Buddha and Marx, whether they were harmonized or became a counter-hegemonic movement. In order to determine if the happiness principle is grounded in spiritual values and aligns with the counter-hegemonic ecosocialist movement, the author examined the ecosocialist perspective. Shrivastava and Zsolnai ( 2022 ) have investigated the theoretical and practical ramifications of creative organisations for well-being rooted in the drive for a well-being economy. Wellbeing and happiness-focused economic frameworks are emerging primarily in developed countries. This new policy framework also abolishes GDP-based economic growth and prioritizes individual well-being and ecological regeneration. To understand its application and interpretation, Van Niekerk ( 2019 ) develops a conceptual framework and theoretical analysis of inclusive economics. It contributes to developing a new paradigm for economic growth, both theoretically and practically.

4.6 Cluster 3: ‘Beyond money’ and happiness policy

It depicts pink circles and nodes, wherein five articles were identified, as shown in Fig. 6 . According to Diener and Seligman ( 2004a ) economic indicators are critical in the early phases of economic growth when meeting basic requirements is the primary focus. However, as society becomes wealthier, an individual’s well-being becomes less dependent on money and more on social interactions and job satisfaction. Individuals reporting high well-being outperform those reporting low well-being in terms of income and performance. A national well-being index is required to evaluate well-being variables and shape policies systematically. Diener and Seligman ( 2018 ) propounded the ‘Beyond Money’ concept in 2004. In response to the shortcomings of GDP and economic measures, other quality-of-life indicators, such as health and education, have been created. The national account of well-being has been proposed as a common path to provide societies with an overall quality of life metric. While measuring the subjective well-being of people, the authors reasoned a societal indicator of the quality of life. In this article, the authors have proposed an economy of well-being model by combining subjective and objective measures to convince policymakers and academicians to enact policies that enhance human welfare. The well-being economy includes quality of life indicators and life satisfaction, subjective well-being and happiness.

Frey and Stutzer ( 2000 ) perceived the microeconomic well-being variables in countries. In the study, survey data was used from 6000 individuals in Switzerland and showed that the individuals are happier in developed democracies and institutions (government federalization). They analyzed the reported subjective well-being data to determine the function of federal and democratic institutions on an individual’s satisfaction with life. The study found a negative relationship between income and unemployment. Three criteria have been employed in the study to determine happiness: demographic and psychological traits, macro- and microeconomic factors, and constitutional circumstances. Thus, a new pair of determinants reflects happiness’s effect on individuals’ income, unemployment, inflation and income growth.

Happiness policy, according to Frey and Gallus ( 2013b ), is an intrinsic aspect of the democratic process in which various opinions are collected and examined. “Happiness policy” is far more critical than continuing a goal such as increasing national income and instead considered an official policy goal. The article focuses on how politicians behave differently when they believe that achieving happiness is the primary objective of policy. Frey et al. ( 2014 ) explored the three critical areas of happiness, which are positive and negative shocks on happiness, choice of comparison and its extent to derive the theoretical propositions that can be investigated in future research. It discussed the areas where a more novel and comprehensive theoretical framework is needed: comparison, adaptation, and happiness policy. Wolfgramm et al. ( 2020 ) derived a value-driven transformation framework in Māori economics of wellbeing. It contributes to a multilevel and comprehensive review of Māori economics and well-being. The framework is adopted to advance the policies and implement economies of well-being.

4.7 Cluster 4: Health, human capital and wellbeing

It is depicted as a red colour circle and nodes in Fig. 6 , and only three papers on empirical investigations were found. Laurent et al. ( 2022 ) investigated the Health-Environment Nexus report published by the “Wellbeing Economy Alliance”. In place of increased production and consumption, they suggested a comprehensive framework for human health and the environment that includes six essential paths. The six key pathways are well-being energy, sustainable food, health care, education, social cooperation and health-environment nexus. The proposed variables yield the co-benefits for the climate, health and sustainable economy. Steer clear of the false perception of trade-offs, such as balancing the economy against the environment or the need to save lives. McKinnon and Kennedy ( 2021 ) focuses on community economics of well-being that benefits entrepreneurs and employees. They investigated the interactions of four social enterprises that work for their employees inside and within the broader community. Cylus et al. ( 2020 ) proposed the opportunities and challenges in adopting the model of happiness or well-being in an economy as an alternative measure of GDP. Orekhov et al. ( 2020 ) proposed the derivation of happiness from the World Happiness Index (WHI) data to estimate the regression model for developed countries.

4.8 Cluster 5: Policy-push for happiness economy

It is depicted as an orange circle and nodes in Fig. 6 , and only five papers on empirical and review investigations were found. Oehler-Șincai et al. ( 2023 ) proposed the conceptual and practical perspective of household-income-labour dynamics for policy formulation. It discusses the measurement of well-being as a representation of various policies focusing on health, productivity, and longevity. It focuses on the role of policy in building the subjective and objective dimensions of well-being, defines the correlation between well-being, employment policies, and governance, is inclined to the well-being performance of various countries, and underscores present risks that jeopardize well-being. Musa et al. ( 2018 ) have developed a “community happiness index” by incorporating the four aspects of sustainability—economic, social, environmental, and urban governance—as well as the other sustainability domains, such as human well-being and eco-environmental well-being. From then onwards, community happiness and sustainable urban development emerged. Chernyahivska et al. ( 2020 ) developed strategies to raise the standard of living for people in countries undergoing economic transition by using the quality of life index. The methods uncovered are enhancing employment opportunities and uplifting the international labour market in urban and rural areas, prioritizing human capital, eliminating gender inequality, focusing on improving the individual’s health, and enhancing social protection. Zheng et al. ( 2019 ) investigated the livelihood and well-being index of the population that makes liveable conditions and city construction in society based on people’s happiness index. The structure of a liveable city should be emphasised on sustainable development. The growth strategy in urban areas is an essential aspect of building a liveable city. Frey and Gallus ( 2013a ) criticised the National Happiness Index as a policy goal in a country because it cannot be measured and thus fails to measure the true happiness of people. To measure real happiness, the government should establish living conditions that enable individuals to become happy. The rule of law and human rights must support the process.

The structure of a liveable city should be emphasized in sustainable development. The growth strategy in urban areas is an essential aspect of building a liveable city. Frey and Gallus ( 2013a ) criticized the National Happiness Index as a policy goal in a country because it cannot be measured and thus fails to identify the true individuals happiness. To measure real happiness, the government should establish living conditions that enable individuals to be happy. The process needs to be supported by human rights and the rule of law.

Visualization of cluster analysis

5 Discussion of findings

Concerns like the improved quality-of-life and a decent standard of living within the ecological frontier of the environment have various effects on individuals overall well-being and life satisfaction. The ‘beyond growth’ approach empathized with the revised concept of growth, which is based on the idea of maximising happiness for a larger number of people rather than being driven by a desire for financial wealth or production. In that aspect, the notion of happiness economy is designed that prioritizes serving both people and the environment over the other. This present article has focused on the beyond growth approach and towards a new economic paradigm by doing bibliometric and visual analysis on the dataset that was obtained from Scopus, helping to determine which nations, publications, and authors were most significant in this field of study.

In this field of study, developed nations have made significant contributions as compared to the developing nations. In total, 59 countries have made the substantial contribution to the beyond growth approach literature an some of them have proposed their respective national well-being economy framwework. Among 59 countries the United States and the United Kingdom have been crucial to the publishing. With the exception of five of the top 10 nations, Europe contributes the most to scientific research. The existing research shows the inclination of developed and developing countries to build a new economic paradigm that goes beyond growth by prioritizing the happiness level at individual as well as at collective level.

The most prolific journals in this research domain are the “International Journal of Environmental Research” and “Public Health” with the total publication of 5 and 4. The top two cited journals were the “ Nature Human Behavior” with 219 citations and the “Quality of Life Research” with 205 citations. Due to various economic and non-economic factors, these journals struggled to strike a balance between scientific accuracy and timeliness, and it became vital to spread accurate and logical knowledge. For, example, discussing the relationship between inequality and well-being, exploring the challenges and opportunites of happiness economy in different countries, assessing the role of health in all policies to support the transition to the well-being economy. Visualization of semantic network analysis of co-ocurrance of authors keywords from the VOSviewer showed the future research scope to explore the association between happiness economy along with green economy, climate change, spirituality and sustainability. However, in the thematic mapping, the motor themes denotes the themes that are well-developed and repetative in research, such as, well-being economy, depression, sustainable development and circular economy. The basic themes depicts the developing and transveral themes such as happiness economy, subjective well-being and climate condition. As a result, future research must place greater emphasis on the theoretical and practical expansion of the research field in view of the determined major subjects.

The present study have performed the cluster analysis to identify the emerging research themes in this domain through VOSviewer that helps to analyze the network of published documents. Based on published papers, the author can analyse the interconnected network structure with the use of cluster analysis. We have identified the top five clusters from the study. Each cluster denote the specific and defined theme of the research in this domain. In cluster 1, the majorly of the authors are working in the area of going beyond GDP and transition towards happiness economy, which consists of empirical and review studies. Cluster 2 represents that authors are exploring the relationship between rethinking growth for sustainability and ecological regeneration to evaluate the transition from a conventional economic thought to a broader view of sustainable well-being which is centred on regional development plans and shifting rural-urban interactions. In cluster 3, the authors are exploring the beyond money and happiness policy themes and identified the shortcomings of GDP and economic measures, other quality-of-life indicators, such as health and education. They have proposed the well-being index to evaluate the well-being variables and shape socio-economic policies systematically. The authors have proposed an economy of well-being model by combining subjective and objective measures to convince policymakers and academicians to enact policies that enhance human welfare. The well-being economy includes quality of life indicators and life satisfaction, subjective well-being and happiness. In cluster 4, the authors are working of related theme of Health, human capital and wellbeing, whereby they have put up a comprehensive framework for health and the environment that includes several important avenues for prioritising human and ecological well-being over increased production and consumption. In cluster 5, the authors have suggested the policy-push for happiness economy in which they have identified the conceptual and practical perspective of household-income-labour dynamics for policy formulation. Majorly of the authors in this clutster have focused on the role of policy in building the subjective and objective dimensions of well-being, defines the correlation between well-being, employment policies, and governance, is inclined to the well-being performance of various countries, and underscores present risks that jeopardize well-being. Hence, the present study will give academics, researchers, and policymakers a thorough understanding of the productivity, features, key factors, and research outcomes in this field of study.

6 Scope for future research avenues

The emergence of a happiness economy will transform society’s traditional welfare measure. Such changes will generate more reliable and practical means to measure the well-being or welfare of an economy. After a rigorous analysis of the existing literature, we have proposed the scope for future research in Table 6 .

7 Conclusion

In 2015, the United Nations proposed the pathbreaking and ambitious seventeen “Sustainable Development Goals” (SDGs) for countries to steer their policies toward achieving them by 2030. In reality, economic growth remains central to the agenda for SDGs, demonstrating the absence of a ground-breaking and inspirational vision that might genuinely place people and their happiness at the core of a new paradigm for development. As this research has reflect, there are various evidence that the happiness economy strategy is well-suited to permeate policies geared towards sustainable development. In this context, ‘happiness’ may be a strong concept that ensures the post-2030 growth will resonate with the socioeconomic and environmental traits of everyone around the world while motivating public policies for happiness.

The current research has emphasized the many dynamics of the happiness economy by using a bibliometric analytic study of 257 articles. We have concluded that the happiness economy is an emerging area that includes different dimensions of happiness, such as ecological regeneration, circular economy, sustainability, sustainable well-being, economic well-being, subjective well-being, and well-being economy. In addition to taking into consideration the advantages and disadvantages of human participation in the market, a happiness-based economic system would offer new metrics to assess all contributions to human and planetary well-being. In terms of theoretical ramifications, we suggest that future scholars concentrate on fusing the welfare and happiness theory with economic policy. As countries are predisposed to generate disharmony and imbalance, maximizing societal well-being now entails expanding sustainable development. Since the happiness economy is still a relatively novel field, it offers numerous potential research opportunities.

8 Limitations

Similar to every other research, this one has significant restrictions as well. We are primarily concerned that all our data were extracted from the Scopus database. Furthermore, future research can utilize other software like BibExcel and Gephi to expound novel variables and linkages. Given the research limitations, this article still provides insightful and relevant direction to policymakers, scholars, and those intrigued by the idea of happiness and well-being in mainstream economics.

The study offers scope for future research in connecting the happiness economy framework with different SDGs. Future studies can also carry empirical research towards creating a universally acceptable ‘happiness economy index’ with human and planetary well-being at its core.

Data availability

Data not used in this article.

Abrar, R.: Building the transition together: WEAll’s perspective on creating a Wellbeing Economy. Well-Being Transition. 157–180 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67860-9_9/COVER

Agrawal, R., Agrawal, S., Samadhiya, A., Kumar, A., Luthra, S., Jain, V.: Adoption of green finance and green innovation for achieving circularity: An exploratory review and future directions. Geosci. Front. 101669 (2023a). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GSF.2023.101669

Agrawal, S., Sharma, N., Singh, M.: Employing CBPR to understand the well-being of higher education students during covid-19 lockdown in India. SSRN Electron. J. (2020). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3628458

Agrawal, S., Sharma, N.: Beyond GDP: A movement toward happiness economy to achieve sustainability. Sustain. Green. Future. 95–114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-24942-6_5

Agrawal, S., Sharma, N., Bruni, M.E., Iazzolino, G.: Happiness economics: Discovering future research trends through a systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 416 , 137860 (2023b). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.137860

Article Google Scholar

Aiyar, S., Ebeke, C.: Inequality of opportunity, inequality of income and economic growth. World Dev. 136 , 105115 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WORLDDEV.2020.105115

Armstrong, C.M.J., Connell, K.Y.H., Lang, C., Ruppert-Stroescu, M., LeHew, M.L.A.: Educating for sustainable fashion: using clothing acquisition abstinence to explore sustainable consumption and life beyond growth. J Consum Policy. 39 (4), 417–439 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-016-9330-z

Approaches to Improving the Quality of Life: How to Enhance the Quality of Life - Abbott L. Ferriss - Google Books . (n.d.). Retrieved April 25, from (2023). https://books.google.co.in/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9AKdtNzGsGcC&oi=fnd&pg=PR8&dq=equality+tends+to+improve+major+objective+ways+of+wellbeing,+from+healthier+communities+to+happier+communities,+from+declining+hate+and+crime+and+to+improved+social+cohesion,+productivity,+unity+and+interpersonal+trust&ots=pZ5kbKdqrC&sig=vfwoVTo2Aur-nV9J9HNF4rbF74o&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Aria, M., Cuccurullo, C.: Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetrics. 11 (4), 959–975 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOI.2017.08.007

Atkinson, S., Fuller, S., Painter, J.: Wellbeing and place, pp. 1–14. Ashgate Publishing (2012). https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/wellbeing-and-place

Bengtsson, M., Alfredsson, E., Cohen, M., Lorek, S., Schroeder, P.: Transforming systems of consumption and production for achieving the sustainable development goals: moving beyond efficiency. Sustain. Sci. 13 (6), 1533–1547 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0582-1

Bayani, E., Ahadi, F., Beigi, J.: The preventive impact of Happiness Economy on Financial Delinquency. Political Sociol. Iran. 5 (11), 4651–4670 (2023). https://doi.org/10.30510/PSI.2022.349645.3666

Better Life Initiative: Measuring Well-Being and Progress - OECD . (n.d.). Retrieved December 8, from (2022). https://www.oecd.org/wise/better-life-initiative.htm

Bowler, D.E., Buyung-Ali, L.M., Knight, T.M., Pullin, A.S.: A systematic review of evidence for the added benefits to health of exposure to natural environments. BMC Public. Health. 10 (1), 1–10 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-456/TABLES/1

Bowling, A.: What things are important in people’s lives? A survey of the public’s judgements to inform scales of health related quality of life. Soc. Sci. Med. 41 (10), 1447–1462 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00113-L

Boyd, J.: Nonmarket benefits of nature: What should be counted in green GDP? Ecol. Econ. 61 (4), 716–723 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLECON.2006.06.016

Brahmi, M., Aldieri, L., Dhayal, K.S., Agrawal, S.: Education 4.0: can it be a component of the sustainable well-being of students? pp. 215–230 (2022). https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-4981-3.ch014

Carrero, G.C., Fearnside, P.M., Valle, D. R., de Alves, S., C: Deforestation trajectories on a Development Frontier in the Brazilian Amazon: 35 years of settlement colonization, policy and economic shifts, and Land Accumulation. Environ. Manage. 2020. 66:6 (6), 966–984 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00267-020-01354-W 66

Chen, C.W.: Can smart cities bring happiness to promote sustainable development? Contexts and clues of subjective well-being and urban livability. Developments Built Environ. 13 , 100108 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DIBE.2022.100108

Chen, X., Lun, Y., Yan, J., Hao, T., Weng, H.: Discovering thematic change and evolution of utilizing social media for healthcare research. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 19 (2), 39–53 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12911-019-0757-4/FIGURES/10

Chernyahivska, V.V., Bilyk, O.I., Charkina, A.O., Zhayvoronok, I., Farynovych, I.V.: Strategy for improving the quality of life in countries with economies in transition. Int. J. Manag. 11 (4), 523–531 (2020).

Clark, A.E., Flèche, S., Senik, C.: Economic growth evens out happiness: evidence from six surveys. Rev Income Wealth. 62 (3), 405–419 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12190

Construction strategies and evaluation models of livable city based on the happiness index | IEEE Conference Publication | IEEE Xplore . (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, from (2023). https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6640911

Cook, D., Davíðsdóttir, B.: An appraisal of interlinkages between macro-economic indicators of economic well-being and the sustainable development goals. Ecol. Econ. 184 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.106996

Cook, D., Davíðsdóttir, B., Gunnarsdóttir, I.: A conceptual exploration of how the pursuit of sustainable Energy Development is implicit in the genuine Progress Indicator. Energies. 15 (6) (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/en15062129

Coscieme, L., Sutton, P., Mortensen, L.F., Kubiszewski, I., Costanza, R., Trebeck, K., Pulselli, F.M., Giannetti, B.F., Fioramonti, L.: Overcoming the myths of mainstream economics to enable a newwellbeing economy. Sustain. (Switzerland). 11 (16) (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164374

Coscieme, L., Mortensen, L.F., Anderson, S., Ward, J., Donohue, I., Sutton, P.C.: Going beyond gross domestic product as an indicator to bring coherence to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 248 , 119232 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2019.119232

Coscieme, L., Mortensen, L.F., Anderson, S., Ward, J., Donohue, I., Sutton, P.C.: Going beyond gross domestic product as an indicator to bring coherence to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 248 (2020a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119232

Costanza, R.: Ecological economics in 2049: Getting beyond the argument culture to the world we all want. Ecol. Econ. 168 , 106484 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ECOLECON.2019.106484

Costanza, R., Caniglia, E., Fioramonti, L., Kubiszewski, I., Lewis, H., Lovins, H., McGlade, J., Mortensen, L.F., Philipsen, D., Pickett, K.E., Ragnarsdottir, K.V., Roberts, D.: Toward a Sustainable Wellbeing Economy. Solutions: For a Sustainable and Desirable Future . (2020). https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/205271

Coyne, C.J., Boettke, P.J.: Economics and Happiness Research: Insights from Austrian and Public Choice Economics. Happiness Public. Policy. 89–105 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230288027_5

Cylus, J., Smith, P.C., Smith, P.C.: The economy of wellbeing: What is it and what are the implications for health? BMJ. 369 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1874

Dervis, H.: Bibliometric analysis using bibliometrix an R package. J. Scientometr. Res. 8 (3), 156–160 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5530/JSCIRES.8.3.32

Dhayal, K.S., Brahmi, M., Agrawal, S., Aldieri, L., Vinci, C.P.: A paradigm shift in education systems due to COVID-19, pp. 157–166 (2022)

Diener, E.: Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95 (3), 542–575. (1984). https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1984-23116-001

Diener, E., Seligman, M.E.P.: Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Supplement , 5 (1). (2004a). https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-3142774261&partnerID=40&md5=e86b2c930837502a9ce9cbd057c0df82

Diener, E., Seligman, M.E.P.: Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychol. Sci. Public. Interest. 5 (1), 1–31 (2004b). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00501001.x

Diener, E., Seligman, M.E.P.: Beyond money: Progress on an economy of well-being. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13 (2), 171–175 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616689467

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., White, M.: Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J. Econ. Psychol. 29 (1), 94–122 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOEP.2007.09.001

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., Lim, W.M.: How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 133 , 285–296 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

Easterlin, R.A.: Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 27 (1), 35–47 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(95)00003-B

Easterlin, R.A.: Happiness and economic growth - the evidence. In: Global Handbook of Quality of Life, pp. 283–299. Springer, Netherlands (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9178-6_12

Fang, Z., Wang, H., Xue, S., Zhang, F., Wang, Y., Yang, S., Zhou, Q., Cheng, C., Zhong, Y., Yang, Y., Liu, G., Chen, J., Qiu, L., Zhi, Y.: A comprehensive framework for detecting economic growth expenses under ecological economics principles in China. Sustainable Horizons. 4 , 100035 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HORIZ.2022.100035

Farooque, M., Zhang, A., Thürer, M., Qu, T., Huisingh, D.: Circular supply chain management: a definition and structured literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 228 , 882–900 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2019.04.303

Ferriss, A.L.: Approaches to improving the quality of life?: how to enhance the quality of life. 150 (2010)

Fioramonti, L., Coscieme, L., Mortensen, L.F.: From gross domestic product to wellbeing: How alternative indicators can help connect the new economy with the Sustainable Development Goals: Https://Doi.Org/10.1177/2053019619869947 , 6 (3), 207–222. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019619869947

Fioramonti, L., Coscieme, L., Mortensen, L.F.: From gross domestic product to wellbeing: How alternative indicators can help connect the new economy with the Sustainable Development Goals. Anthropocene Rev. 6 (3), 207–222 (2019a). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019619869947

Fioramonti, L., Coscieme, L., Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Trebeck, K., Wallis, S., Roberts, D., Mortensen, L.F., Pickett, K.E., Wilkinson, R., Ragnarsdottír, K.V., McGlade, J., Lovins, H., De Vogli, R.: Wellbeing economy: An effective paradigm to mainstream post-growth policies? Ecol. Econ. 192 , 107261 (2022b). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107261

Fioramonti, L., Coscieme, L., Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Trebeck, K., Wallis, S., Roberts, D., Mortensen, L.F., Pickett, K.E., Wilkinson, R., Ragnarsdottír, K.V., McGlade, J., Lovins, H., De Vogli, R.: Wellbeing economy: An effective paradigm to mainstream post-growth policies? Ecol. Econ. 192 (2022a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107261

Forgeard, M.J.C., Jayawickreme, E., Kern, M.L., Seligman, M.E.P.: Doing the right thing: measuring wellbeing for public policy. Int J Wellbeing. 1 (1), 79–106 (2011). https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v1i1.15

Francart, N., Malmqvist, T., Hagbert, P.: Climate target fulfilment in scenarios for a sustainable Swedish built environment beyond growth. Futures. 98 , 1–18 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUTURES.2017.12.001

Franceschet, M.: A cluster analysis of scholar and journal bibliometric indicators. J. Am. Soc. Inform. Sci. Technol. 60 (10), 1950–1964 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.21152

Frey, B.S., Gallus, J.: Happiness policy and economic development. Int. J. Happiness Dev. 1 (1), 102 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHD.2012.050835

Frey, B.S., Gallus, J.: Political economy of happiness. Appl. Econ. 45 (30), 4205–4211 (2013a). https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2013.778950

Frey, B.S., Gallus, J.: Subjective well-being and policy. Topoi. 32 (2), 207–212 (2013b). https://doi.org/10.1007/S11245-013-9155-1/METRICS

Frey, B.S., Stutzer, A.: Happiness, economy and institutions. Econ. J. 110 (466), 918–938 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00570

Frey, B.S., Stutzer, A.: What can economists learn from Happiness Research? Source: J. Economic Literature. 40 (2), 402–435 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102320161320

Frey, B.S., Stutzer, A.: Happiness research: State and prospects. Rev. Soc. Econ. 63 (2), 207–228 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760500130366

Frey, B.S., Gallus, J., Steiner, L.: Open issues in happiness research. Int. Rev. Econ. 61 (2), 115–125 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-014-0203-y

Frijters, P., Clark, A.E., Krekel, C., Layard, R.: A happy choice: Wellbeing as the goal of government. Behav. Public. Policy. 4 (2), 126–165 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1017/BPP.2019.39

Galbraith, J.K.: Inequality, unemployment and growth: new measures for old controversies. J. Econ. Inequal. 7 (2), 189–206 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-008-9083-2

Giannetti, B.F., Agostinho, F., Almeida, C.M.V.B., Huisingh, D.: A review of limitations of GDP and alternative indices to monitor human wellbeing and to manage eco-system functionality. J. Clean. Prod. 87 (1), 11–25. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.10.051

Gilead, T.: Education’s role in the economy: towards a new perspective. 47 (4), 457–473. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2016.1195790

Griep, Y., Hyde, M., Vantilborgh, T., Bidee, J., De Witte, H., Pepermans, R.: Voluntary work and the relationship with unemployment, health, and well-being: A two-year follow-up study contrasting a materialistic and psychosocial pathway perspective. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 20 (2), 190–204 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1037/A0038342

Hallberg, M., Kullenberg, C.: Happiness studies. Nord. J. Work. Life Stud. 7 (1), 42–50 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5324/NJSTS.V7I1.2530

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., Sachs, J., Neve, J.-E.: World Happiness Report 2021. Happiness and Subjective Well-Being . (2021). https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/hw_happiness/5

Ikeda, D. (2010). A New Humanism: The University Addresses of Daisaku Ikeda - Daisaku Ikeda - Google Books . books.google.co.in/books?hl = en&lr=&id = 17aKDwAAQBAJ&oi = fnd&pg = PP1&ots = gQvBHjJA7P&sig = wVOxQ_XlCIrj39Q08W-kxc_sPjA&redir_esc = y#v = onepage&q&f = false

Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., Welzel, C.: Development, freedom, and rising happiness: a global perspective (1981–2007). 3 (4), 264–285 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00078.x

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A.B.: Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J. Econ. Perspect. 20 (1), 3–24 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526030

Keniger, L.E., Gaston, K.J., Irvine, K.N., Fuller, R.A.: What are the benefits of interacting with nature? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 10 (3), 913–935 (2013). https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH10030913

Kinman, G., Jones, F.: A life beyond work? job demands, work-life balance, and wellbeing in UK academics. 17 (1–2), 41–60 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/10911350802165478

Kim, K.H., Kang, E., Yun, Y.H.: Public support for health taxes and media regulation of harmful products in South Korea. BMC Public. Health. 19 (1), 1–12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-019-7044-2/TABLES/5

King, M.F., Renó V.F., Novo, E.M.L.M.: The concept, dimensions and methods of assessment of human well-being within a socioecological context: a literature review. Soc Indic Res. 116 (3), 681–698 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0320-0

Knickel, K., Almeida, A., Galli, F., Hausegger-Nestelberger, K., Goodwin-Hawkins, B., Hrabar, M., Keech, D., Knickel, M., Lehtonen, O., Maye, D., Ruiz-Martinez, I., Šūmane, S., Vulto, H., Wiskerke, J.S.C.: Transitioning towards a sustainable wellbeing economy—implications for rural–urban relations. Land. 10 (5) (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050512

Kullenberg, C., Nelhans, G.: The happiness turn? Mapping the emergence of happiness studies using cited references. Scientometrics. 103 (2), 615–630 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/S11192-015-1536-3/FIGURES/5

Lama, D.: A human approach to world peace: his holiness the Dalai Lama. J. Hum. Values. 18 (2), 91–100 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1177/0971685812454479

Laurent, É., Galli, A., Battaglia, F., Libera Marchiori, D., G., Fioramonti, L.: Toward health-environment policy: Beyond the Rome Declaration. Global Environmental Change , 72 . (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102418

Lauzon, C., Stevenson, A., Peel, K., Brinsdon, S.: A “bottom up” health in all policies program: supporting local government wellbeing approaches. Health Promot J Austr. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.712

Lavrov, I.: Prospect as a model of the future in the happiness economy - new normative theory of wellbeing. Published Papers (2010). https://ideas.repec.org/p/rnp/ppaper/che5.html

McKinnon, K., Kennedy, M.: Community economies of wellbeing: How social enterprises contribute to surviving well together. In: Social Enterprise, Health, and Wellbeing: Theory, Methods, and Practice. Taylor and Francis Inc (2021). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003125976-5

Mengist, W., Soromessa, T., Legese, G.: Method for conducting systematic literature review and meta-analysis for environmental science research. MethodsX. 7 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2019.100777

Meredith, J.: Theory building through conceptual methods. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage. 13 (5), 3–11 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1108/01443579310028120

Millward-Hopkins, J., Steinberger, J.K., Rao, N.D., Oswald, Y.: Providing decent living with minimum energy: A global scenario. Glob. Environ. Change. 65 , 102168 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GLOENVCHA.2020.102168

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4 (1), 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Mongeon, P., Paul-Hus, A.: The journal coverage of web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics. 106 (1), 213–228 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/S11192-015-1765-5/FIGURES/6

Musa, H.D., Yacob, M.R., Abdullah, A.M., Ishak, M.Y.: Enhancing subjective well-being through strategic urban planning: Development and application of community happiness index. Sustainable Cities Soc. 38 , 184–194 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCS.2017.12.030

Ni, Z., Yang, J., Razzaq, A.: How do natural resources, digitalization, and institutional governance contribute to ecological sustainability through load capacity factors in highly resource-consuming economies? Resour. Policy. 79 , 103068 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESOURPOL.2022.103068

Nunes, A.R., Lee, K., O’Riordan, T.: The importance of an integrating framework for achieving the sustainable development goals: the example of health and well-being. BMJ Glob Health. 1 (3), e000068 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJGH-2016-000068

Ócsai, A.: The future of ecologically conscious business. Palgrave Stud. Sustainable Bus. Association Future Earth. 259–274 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60918-4_7

OECD.: Measuring and assessing well-being in Israel (2016). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264246034-EN

Oehler-Șincai, I.M.: Well-Being, Quality of Governance, and Employment Policies: International Perspectives. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2023.2189078

Orekhov, V.D., Prichina, O.S., Loktionova, Y.N., Yanina, O.N., Gusareva, N.B.: Scientific analysis of the happiness index in regard to the human capital development. J. Adv. Res. Dyn. Control Syst. 12 (4 Special Issue), 467–478 (2020). https://doi.org/10.5373/JARDCS/V12SP4/20201512

Oswald, A.J.: Happiness and economic performance. Econ. J. 107 (445), 1815–1831 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-0297.1997.TB00085.X

Pillay, D.: Happiness, wellbeing and ecosocialism–a radical humanist perspective. Globalizations. 17 (2), 380–396 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2019.1652470

Roy, M.J.: Towards a ‘Wellbeing Economy’: What Can We Learn from Social Enterprise? 269–284. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68295-8_13

Rubio-Mozos, E., García-Muiña, F.E., Fuentes-Moraleda, L.: Rethinking 21st-century businesses: An approach to fourth sector SMEs in their transition to a sustainable model committed to SDGs. Sustain. (Switzerland). 11 (20) (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11205569

Santini, Z.I., Koyanagi, A., Tyrovolas, S., Mason, C., Haro, J.M.: The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 175 , 53–65 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2014.12.049

Sangha, K.K., Le Brocque, A., Costanza, R., Cadet-James, Y.: Ecosystems and indigenous well-being: An integrated framework. Global Ecol. Conserv. 4 , 197–206 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.GECCO.2015.06.008

Schyns, P.: Crossnational differences in happiness: Economic and cultural factors explored. Soc. Indic. Res. 43 (1–2), 3–26 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006814424293/METRICS

Shrivastava, P., Zsolnai, L.: Wellbeing-oriented organizations: Connecting human flourishing with ecological regeneration. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 31 (2), 386–397 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12421

Skul’skaya, L.V., Shirokova, T.K.: Is it possible to build an economy of happiness? (On the book by E.E. Rumyantseva Economy of Happiness (INFRA-M, Moscow, 2010) [in Russian]). Studies on Russian Economic Development 2010 21:4 , 21 (4), 455–456. (2010). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1075700710040131

Sohn, K.: Considering happiness for economic development: determinants of happiness in Indonesia. SSRN Electronic J. (2010). https://doi.org/10.2139/SSRN.2489785

Spruk, R., Kešeljević, A.: Institutional origins of subjective well-being: estimating the effects of economic freedom on national happiness. J. Happiness Stud. 17 (2), 659–712 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/S10902-015-9616-X

Su, Y.S., Lien, D., Yao, Y.: Economic growth and happiness in China: a Bayesian multilevel age-period-cohort analysis based on the CGSS data 2005–2015. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance. 77 , 191–205 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IREF.2021.09.018

Stucke, M.E.: Should competition policy promote happiness? Fordham Law Review , 81 (5), 2575–2645. (2013). https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-84878026480&partnerID=40&md5=66be6f8cd1fe9df6ca216e7724c928b3

van Niekerk, A.: A conceptual framework for inclusive economics. South. Afr. J. Economic Manage. Sci. 22 (1) (2019). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v22i1.2915

Vicente, M.J.V.: How more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone’s well-being por Richard Wilkinson y Kate Pickett. Sistema: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, ISSN 0210–0223, No 257, 2020, Págs. 135–140 , 257 , 135–140. (2020). https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7999261

Wang, Q., Su, M.: The effects of urbanization and industrialization on decoupling economic growth from carbon emission – a case study of China. Sustain Cities Soc. 51 , 101758 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SCS.2019.101758

Wiedenhofer, D., Virág, D., Kalt, G., Plank, B., Streeck, J., Pichler, M., Mayer, A., Krausmann, F., Brockway, P., Schaffartzik, A., Fishman, T., Hausknost, D., Leon-Gruchalski, B., Sousa, T., Creutzig, F., Haberl, H.: A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part I: Bibliometric and conceptual mapping. Environ. Res. Lett. 15 (6), 063002 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/AB8429

Wolfgramm, R., Spiller, C., Henry, E., Pouwhare, R.: A culturally derived framework of values-driven transformation in Māori economies of well-being (Ngā Hono ōhanga oranga). AlterNative. 16 (1), 18–28 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180119885663

Wu, Y., Zhu, Q., Zhu, B.: Decoupling analysis of world economic growth and CO2 emissions: a study comparing developed and developing countries. J. Clean. Prod. 190 , 94–103 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.139

Zheng, S., Wang, J., Sun, C., Zhang, X., Kahn, M.E.: Air pollution lowers Chinese urbanites’ expressed happiness on social media. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3 (3), 237–243 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0521-2

Download references

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Salerno within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Malaviya National Institute of Technology Jaipur, Malaviya Nagar, J.L.N. Marg, Jaipur, Rajasthan, 302017, India

Shruti Agrawal & Nidhi Sharma

Department of Economics and Finance, Birla Institute of Technology and Science (BITS), Pilani, Rajasthan, India

Karambir Singh Dhayal

Department of Economics and Statistics, University of Salerno, Fisciano, Italy

Luca Esposito

Karelian Institute, University of Eastern Finland, Joensuu, Finland

Erasmus Happiness Economics Research Organisation, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions