School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

What is Literature? || Definition & Examples

"what is literature": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the full series: The Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms

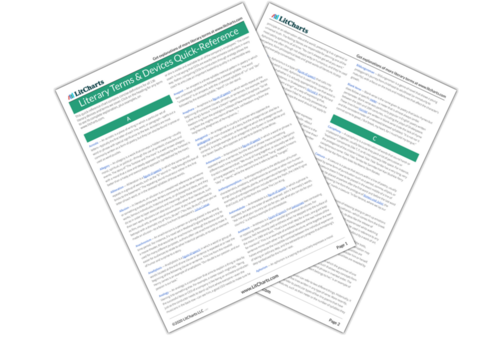

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- Oregon State Admissions Info

What is Literature? Transcript (English and Spanish Subtitles Available in Video; Click HERE for Spanish Transcript)

By Evan Gottlieb & Paige Thomas

3 January 2022

The question of what makes something literary is an enduring one, and I don’t expect that we’ll answer it fully in this short video. Instead, I want to show you a few different ways that literary critics approach this question and then offer a short summary of the 3 big factors that we must consider when we ask the question ourselves.

Let’s begin by making a distinction between “Literature with a capital L” and “literature with a small l.”

“Literature with a small l” designates any written text: we can talk about “the literature” on any given subject without much difficulty.

“Literature with a capital L”, by contrast, designates a much smaller set of texts – a subset of all the texts that have been written.

what_is_literature_little_l.png

So what makes a text literary or what makes a text “Literature with a capital L”?

Let’s start with the word itself. “Literature” comes from Latin, and it originally meant “the use of letters” or “writing.” But when the word entered the Romance languages that derived from Latin, it took on the additional meaning of “knowledge acquired from reading or studying books.” So we might use this definition to understand “Literature with a Capital L” as writing that gives us knowledge--writing that should be studied.

But this begs the further question: what books or texts are worth studying or close reading ?

For some critics, answering this question is a matter of establishing canonicity. A work of literature becomes “canonical” when cultural institutions like schools or universities or prize committees classify it as a work of lasting artistic or cultural merit.

The canon, however, has proved problematic as a measure of what “Literature with a capital L” is because the gatekeepers of the Western canon have traditionally been White and male. It was only in the closing decades of the twentieth century that the canon of Literature was opened to a greater inclusion of diverse authors.

And here’s another problem with that definition: if inclusion in the canon were our only definition of Literature, then there could be no such thing as contemporary Literature, which, of course, has not yet stood the test of time.

And here’s an even bigger problem: not every book that receives good reviews or a wins a prize turns out to be of lasting value in the eyes of later readers.

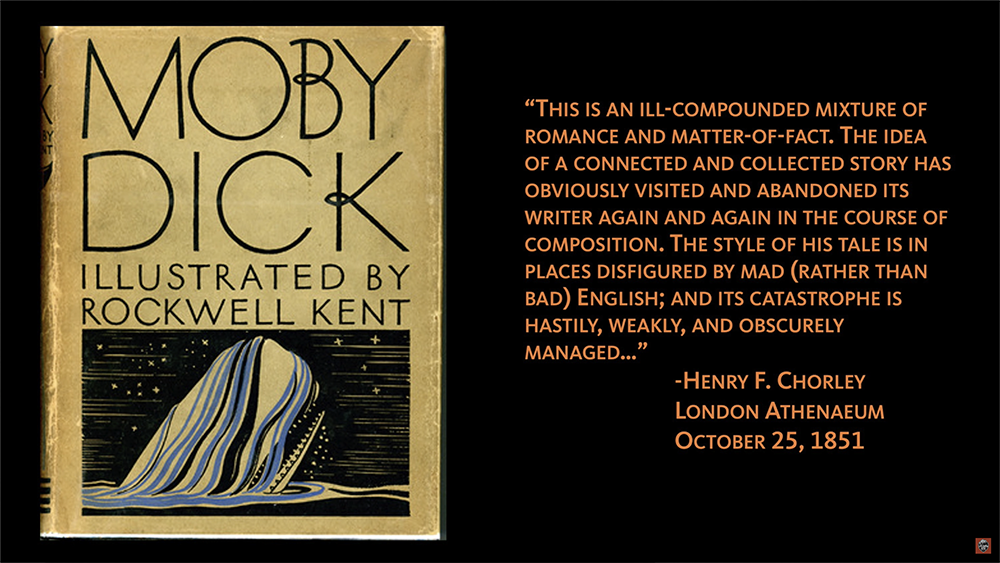

On the other hand, a novel like Herman Melville’s Moby-Di ck, which was NOT received well by critics or readers when it was first published in 1851, has since gone on to become a mainstay of the American literary canon.

moby_dick_with_quote.png

As you can see, canonicity is obviously a problematic index of literariness.

So… what’s the alternative? Well, we could just go with a descriptive definition: “if you love it, then it’s Literature!”

But that’s a little too subjective. For example, no matter how much you may love a certain book from your childhood (I love The Very Hungry Caterpillar ) that doesn’t automatically make it literary, no matter how many times you’ve re-read it.

Furthermore, the very idea that we should have an emotional attachment to the books we read has its own history that cannot be detached from the rise of the middle class and its politics of telling people how to behave.

Ok, so “literature with a capital L” cannot always by defined by its inclusion in the canon or the fact that it has been well-received so…what is it then? Well, for other critics, what makes something Literature would seem to be qualities within the text itself.

According to the critic Derek Attridge, there are three qualities that define modern Western Literature:

1. a quality of invention or inventiveness in the text itself;

2. the reader’s sense that what they are reading is singular. In other words, the unique vision of the writer herself.

3. a sense of ‘otherness’ that pushes the reader to see the world around them in a new way

Notice that nowhere in this three-part definition is there any limitation on the content of Literature. Instead, we call something Literature when it affects the reader at the level of style and construction rather than substance.

In other words, Literature can be about anything!

what_is_literature_caterpillar.png

The idea that a truly literary text can change a reader is of course older than this modern definition. In the English tradition, poetry was preferred over novels because it was thought to create mature and sympathetic reader-citizens.

Likewise, in the Victorian era, it was argued that reading so-called “great” works of literature was the best way for readers to realize their full spiritual potentials in an increasingly secular world.

But these never tell us precisely what “the best” is. To make matters worse, as I mentioned already, “the best” in these older definitions was often determined by White men in positions of cultural and economic power.

So we are still faced with the question of whether there is something inherent in a text that makes it literary.

Some critics have suggested that a sense of irony – or, more broadly, a sense that there is more than one meaning to a given set of words – is essential to “Literature with a capital L.”

Reading for irony means reading slowly or at least attentively. It demands a certain attention to the complexity of the language on the page, whether that language is objectively difficult or not.

In a similar vein, other critics have claimed that the overall effect of a literary text should be one of “defamiliarization,” meaning that the text asks or even forces readers to see the world differently than they did before reading it.

Along these lines, literary theorist Roland Barthes maintained that there were two kinds of texts: the text of pleasure, which we can align with everyday Literature with a small l” and the text of jouissance , (yes, I said jouissance) which we can align with Literature. Jouissance makes more demands on the reader and raises feelings of strangeness and wonder that surpass the everyday and even border on the painful or disorienting.

Barthes’ definition straddles the line between objectivity and subjectivity. Literature differs from the mass of writing by offering more and different kinds of experiences than the ordinary, non-literary text.

Literature for Barthes is thus neither entirely in the eye of the beholder, nor something that can be reduced to set of repeatable, purely intrinsic characteristics.

This negative definition has its own problems, though. If the literary text is always supposed to be innovative and unconventional, then genre fiction, which IS conventional, can never be literary.

So it seems that whatever hard and fast definition we attempt to apply to Literature, we find that we run up against inevitable exceptions to the rules.

As we examine the many problematic ways that people have defined literature, one thing does become clear. In each of the above examples, what counts as Literature depends upon three interrelated factors: the world, the text, and the critic or reader.

You see, when we encounter a literary text, we usually do so through a field of expectations that includes what we’ve heard about the text or author in question [the world], the way the text is presented to us [the text], and how receptive we as readers are to the text’s demands [the reader].

With this in mind, let’s return to where we started. There is probably still something to be said in favor of the “test of time” theory of Literature.

After all, only a small percentage of what is published today will continue to be read 10, 20, or even 100 years from now; and while the mechanisms that determine the longevity of a text are hardly neutral, one can still hope that individual readers have at least some power to decide what will stay in print and develop broader cultural relevance.

The only way to experience what Literature is, then, is to keep reading: as long as there are avid readers, there will be literary texts – past, present, and future – that challenge, excite, and inspire us.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Gottlieb, Evan and Paige Thomas. "What is Literature?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 3 Jan. 2022, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-literature-definition-examples. Accessed [insert date].

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1 What Is Literature and Why Do We Study It?

In this book created for my English 211 Literary Analysis introductory course for English literature and creative writing majors at the College of Western Idaho, I’ll introduce several different critical approaches that literary scholars may use to answer these questions. The critical method we apply to a text can provide us with different perspectives as we learn to interpret a text and appreciate its meaning and beauty.

The existence of literature, however we define it, implies that we study literature. While people have been “studying” literature as long as literature has existed, the formal study of literature as we know it in college English literature courses began in the 1940s with the advent of New Criticism. The New Critics were formalists with a vested interest in defining literature–they were, after all, both creating and teaching about literary works. For them, literary criticism was, in fact, as John Crowe Ransom wrote in his 1942 essay “ Criticism, Inc., ” nothing less than “the business of literature.”

Responding to the concern that the study of literature at the university level was often more concerned with the history and life of the author than with the text itself, Ransom responded, “the students of the future must be permitted to study literature, and not merely about literature. But I think this is what the good students have always wanted to do. The wonder is that they have allowed themselves so long to be denied.”

We’ll learn more about New Criticism in Section Three. For now, let’s return to the two questions I posed earlier.

What is literature?

First, what is literature ? I know your high school teacher told you never to look up things on Wikipedia, but for the purposes of literary studies, Wikipedia can actually be an effective resource. You’ll notice that I link to Wikipedia articles occasionally in this book. Here’s how Wikipedia defines literature :

“ Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction , drama , and poetry . [1] In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include oral literature , much of which has been transcribed. [2] Literature is a method of recording, preserving, and transmitting knowledge and entertainment, and can also have a social, psychological, spiritual, or political role.”

This definition is well-suited for our purposes here because throughout this course, we will be considering several types of literary texts in a variety of contexts.

I’m a Classicist—a student of Greece and Rome and everything they touched—so I am always interested in words with Latin roots. The Latin root of our modern word literature is litera , or “letter.” Literature, then, is inextricably intertwined with the act of writing. But what kind of writing?

Who decides which texts are “literature”?

The second question is at least as important as the first one. If we agree that literature is somehow special and different from ordinary writing, then who decides which writings count as literature? Are English professors the only people who get to decide? What qualifications and training does someone need to determine whether or not a text is literature? What role do you as the reader play in this decision about a text?

Let’s consider a few examples of things that we would all probably classify as literature. I think we can all (probably) agree that the works of William Shakespeare are literature. We can look at Toni Morrison’s outstanding ouvre of work and conclude, along with the Nobel Prize Committee, that books such as Beloved and Song of Solomon are literature. And if you’re taking a creative writing course and have been assigned the short stories of Raymond Carver or the poems of Joy Harjo , you’re probably convinced that these texts are literature too.

In each of these three cases, a different “deciding” mechanism is at play. First, with Shakespeare, there’s history and tradition. These plays that were written 500 years ago are still performed around the world and taught in high school and college English classes today. It seems we have consensus about the tragedies, histories, comedies, and sonnets of the Bard of Avon (or whoever wrote the plays).

In the second case, if you haven’t heard of Toni Morrison (and I am very sorry if you haven’t), you probably have heard of the Nobel Prize. This is one of the most prestigious awards given in literature, and since she’s a winner, we can safely assume that Toni Morrison’s works are literature.

Finally, your creative writing professor is an expert in their field. You know they have an MFA (and worked hard for it), so when they share their favorite short stories or poems with you, you trust that they are sharing works considered to be literature, even if you haven’t heard of Raymond Carver or Joy Harjo before taking their class.

(Aside: What about fanfiction? Is fanfiction literature?)

We may have to save the debate about fan fiction for another day, though I introduced it because there’s some fascinating and even literary award-winning fan fiction out there.

Returning to our question, what role do we as readers play in deciding whether something is literature? Like John Crowe Ransom quoted above, I think that the definition of literature should depend on more than the opinions of literary critics and literature professors.

I also want to note that contrary to some opinions, plenty of so-called genre fiction can also be classified as literature. The Nobel Prize winning author Kazuo Ishiguro has written both science fiction and historical fiction. Iain Banks , the British author of the critically acclaimed novel The Wasp Factory , published popular science fiction novels under the name Iain M. Banks. In other words, genre alone can’t tell us whether something is literature or not.

In this book, I want to give you the tools to decide for yourself. We’ll do this by exploring several different critical approaches that we can take to determine how a text functions and whether it is literature. These lenses can reveal different truths about the text, about our culture, and about ourselves as readers and scholars.

“Turf Wars”: Literary criticism vs. authors

It’s important to keep in mind that literature and literary theory have existed in conversation with each other since Aristotle used Sophocles’s play Oedipus Rex to define tragedy. We’ll look at how critical theory and literature complement and disagree with each other throughout this book. For most of literary history, the conversation was largely a friendly one.

But in the twenty-first century, there’s a rising tension between literature and criticism. In his 2016 book Literature Against Criticism: University English and Contemporary Fiction in Conflict, literary scholar Martin Paul Eve argues that twenty-first century authors have developed

a series of novelistic techniques that, whether deliberate or not on the part of the author, function to outmanoeuvre, contain, and determine academic reading practices. This desire to discipline university English through the manipulation and restriction of possible hermeneutic paths is, I contend, a result firstly of the fact that the metafictional paradigm of the high-postmodern era has pitched critical and creative discourses into a type of productive competition with one another. Such tensions and overlaps (or ‘turf wars’) have only increased in light of the ongoing breakdown of coherent theoretical definitions of ‘literature’ as distinct from ‘criticism’ (15).

One of Eve’s points is that by narrowly and rigidly defining the boundaries of literature, university English professors have inadvertently created a situation where the market increasingly defines what “literature” is, despite the protestations of the academy. In other words, the gatekeeper role that literary criticism once played is no longer as important to authors. For example, (almost) no one would call 50 Shades of Grey literature—but the salacious E.L James novel was the bestselling book of the decade from 2010-2019, with more than 35 million copies sold worldwide.

If anyone with a blog can get a six-figure publishing deal , does it still matter that students know how to recognize and analyze literature? I think so, for a few reasons.

- First, the practice of reading critically helps you to become a better reader and writer, which will help you to succeed not only in college English courses but throughout your academic and professional career.

- Second, analysis is a highly sought after and transferable skill. By learning to analyze literature, you’ll practice the same skills you would use to analyze anything important. “Data analyst” is one of the most sought after job positions in the New Economy—and if you can analyze Shakespeare, you can analyze data. Indeed.com’s list of top 10 transferable skills includes analytical skills , which they define as “the traits and abilities that allow you to observe, research and interpret a subject in order to develop complex ideas and solutions.”

- Finally, and for me personally, most importantly, reading and understanding literature makes life make sense. As we read literature, we expand our sense of what is possible for ourselves and for humanity. In the challenges we collectively face today, understanding the world and our place in it will be important for imagining new futures.

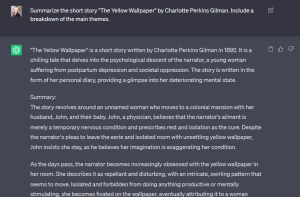

A note about using generative artificial intelligence

As I was working on creating this textbook, ChatGPT exploded into academic consciousness. Excited about the possibilities of this new tool, I immediately began incorporating it into my classroom teaching. In this book, I have used ChatGPT to help me with outlining content in chapters. I also used ChatGPT to create sample essays for each critical lens we will study in the course. These essays are dry and rather soulless, but they do a good job of modeling how to apply a specific theory to a literary text. I chose John Donne’s poem “The Canonization” as the text for these essays so that you can see how the different theories illuminate different aspects of the text.

I encourage students in my courses to use ChatGPT in the following ways:

- To generate ideas about an approach to a text.

- To better understand basic concepts.

- To assist with outlining an essay.

- To check grammar, punctuation, spelling, paragraphing, and other grammar/syntax issues.

If you choose to use Chat GPT, please include a brief acknowledgment statement as an appendix to your paper after your Works Cited page explaining how you have used the tool in your work. Here is an example of how to do this from Monash University’s “ Acknowledging the Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence .”

I acknowledge the use of [insert AI system(s) and link] to [specific use of generative artificial intelligence]. The prompts used include [list of prompts]. The output from these prompts was used to [explain use].

Here is more information about how to cite the use of generative AI like ChatGPT in your work. The information below was adapted from “Acknowledging and Citing Generative AI in Academic Work” by Liza Long (CC BY 4.0).

The Modern Language Association (MLA) uses a template of core elements to create citations for a Works Cited page. MLA asks students to apply this approach when citing any type of generative AI in their work. They provide the following guidelines:

Cite a generative AI tool whenever you paraphrase, quote, or incorporate into your own work any content (whether text, image, data, or other) that was created by it. Acknowledge all functional uses of the tool (like editing your prose or translating words) in a note, your text, or another suitable location. Take care to vet the secondary sources it cites. (MLA)

Here are some examples of how to use and cite generative AI with MLA style:

Example One: Paraphrasing Text

Let’s say that I am trying to generate ideas for a paper on Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s short story “The Yellow Wallpaper.” I ask ChatGPT to provide me with a summary and identify the story’s main themes. Here’s a link to the chat . I decide that I will explore the problem of identity and self-expression in my paper.

My Paraphrase of ChatGPT with In-Text Citation

The problem of identity and self expression, especially for nineteenth-century women, is a major theme in “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (“Summarize the short story”).

Works Cited Entry

“Summarize the short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Include a breakdown of the main themes” prompt. ChatGPT. 24 May Version, OpenAI, 20 Jul. 2023, https://chat.openai.com/share/d1526b95-920c-48fc-a9be-83cd7dfa4be5

Example Two: Quoting Text

In the same chat, I continue to ask ChatGPT about the theme of identity and self expression. Here’s an example of how I could quote the response in the body of my paper:

When I asked ChatGPT to describe the theme of identity and self expression, it noted that the eponymous yellow wallpaper acts as a symbol of the narrator’s self-repression. However, when prompted to share the scholarly sources that formed the basis of this observation, ChatGPT responded, “As an AI language model, I don’t have access to my training data, but I was trained on a mixture of licensed data, data created by human trainers, and publicly available data. OpenAI, the organization behind my development, has not publicly disclosed the specifics of the individual datasets used, including whether scholarly sources were specifically used” (“Summarize the short story”).

It’s worth noting here that ChatGPT can “ hallucinate ” fake sources. As a Microsoft training manual notes, these chatbots are “built to be persuasive, not truthful” (Weiss &Metz, 2023). The May 24, 2023 version will no longer respond to direct requests for references; however, I was able to get around this restriction fairly easily by asking for “resources” instead.

When I ask for resources to learn more about “The Yellow Wallpaper,” here is one source it recommends:

“Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper: A Symptomatic Reading” by Elaine R. Hedges: This scholarly article delves into the psychological and feminist themes of the story, analyzing the narrator’s experience and the implications of the yellow wallpaper on her mental state. It’s available in the journal “Studies in Short Fiction.” (“Summarize the short story”).

Using Google Scholar, I look up this source to see if it’s real. Unsurprisingly, this source is not a real one, but it does lead me to another (real) source: Kasmer, Lisa. “Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s’ The Yellow Wallpaper’: A Symptomatic Reading.” Literature and Psychology 36.3 (1990): 1.

Note: ALWAYS check any sources that ChatGPT or other generative AI tools recommend.

For more information about integrating and citing generative artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT, please see this section of Write What Matters.

I acknowledge that ChatGPT does not respect the individual rights of authors and artists and ignores concerns over copyright and intellectual property in its training; additionally, I acknowledge that the system was trained in part through the exploitation of precarious workers in the global south. In this work I specifically used ChatGPT to assist with outlining chapters, providing background information about critical lenses, and creating “model” essays for the critical lenses we will learn about together. I have included links to my chats in an appendix to this book.

Critical theories: A targeted approach to writing about literature

Ultimately, there’s not one “right” way to read a text. In this book. we will explore a variety of critical theories that scholars use to analyze literature. The book is organized around different targets that are associated with the approach introduced in each chapter. In the introduction, for example, our target is literature. In future chapters you’ll explore these targeted analysis techniques:

- Author: Biographical Criticism

- Text: New Criticism

- Reader: Reader Response Criticism

- Gap: Deconstruction (Post-Structuralism)

- Context: New Historicism and Cultural Studies

- Power: Marxist and Postcolonial Criticism

- Mind: Psychological Criticism

- Gender: Feminist, Post Feminist, and Queer Theory

- Nature: Ecocriticism

Each chapter will feature the target image with the central approach in the center. You’ll read a brief introduction about the theory, explore some primary texts (both critical and literary), watch a video, and apply the theory to a primary text. Each one of these theories could be the subject of its own entire course, so keep in mind that our goal in this book is to introduce these theories and give you a basic familiarity with these tools for literary analysis. For more information and practice, I recommend Steven Lynn’s excellent Texts and Contexts: Writing about Literature with Critical Theory , which provides a similar introductory framework.

I am so excited to share these tools with you and see you grow as a literary scholar. As we explore each of these critical worlds, you’ll likely find that some critical theories feel more natural or logical to you than others. I find myself much more comfortable with deconstruction than with psychological criticism, for example. Pay attention to how these theories work for you because this will help you to expand your approaches to texts and prepare you for more advanced courses in literature.

P.S. If you want to know what my favorite book is, I usually tell people it’s Herman Melville’s Moby Dick . And I do love that book! But I really have no idea what my “favorite” book of all time is, let alone what my favorite book was last year. Every new book that I read is a window into another world and a template for me to make sense out of my own experience and better empathize with others. That’s why I love literature. I hope you’ll love this experience too.

writings in prose or verse, especially : writings having excellence of form or expression and expressing ideas of permanent or universal interest (Merriam Webster)

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction to Literature: What? Why? How?

When is the last time you read a book or a story simply because it interested you? If you were to classify that book, would you call it fiction or literature? This is an interesting separation, with many possible reasons for it. One is that “fiction” and “literature” are regarded as quite different things. “Fiction,” for example, is what people read for enjoyment. “Literature” is what they read for school. Or “fiction” is what living people write and is about the present. “Literature” was written by people (often white males) who have since died and is about times and places that have nothing to do with us. Or “fiction” offers everyday pleasures, but “literature” is to be honored and respected, even though it is boring. Of course, when we put anything on a pedestal, we remove it from everyday life, so the corollary is that literature is to be honored and respected, but it is not to be read, certainly not by any normal person with normal interests.

Sadly, it is the guardians of literature, that is, of the classics, who have done so much to take the life out of literature, to put it on a pedestal and thereby to make it an irrelevant aspect of American life. People study literature because they love literature. They certainly don’t do it for the money. But what happens too often, especially in colleges, is that teachers forget what it was that first interested them in the study of literature. They forget the joy that they first felt (and perhaps still feel) as they read a new novel or a poem or as they reread a work and saw something new in it. Instead, they erect formidable walls around these literary works, giving the impression that the only access to a work is through deep learning and years of study. Such study is clearly important for scholars, but this kind of scholarship is not the only way, or even necessarily the best way, for most people to approach literature. Instead it makes the literature seem inaccessible. It makes the literature seem like the province of scholars. “Oh, you have to be smart to read that,” as though Shakespeare or Dickens or Woolf wrote only for English teachers, not for general readers.

What is Literature?

In short, literature evokes imaginative worlds through the conscious arrangement of words that tell a story. These stories are told through different genres, or types of literature, like novels, short stories, poetry, drama, and the essay. Each genre is associated with certain conventions. In this course, we will study poetry, short fiction, and drama (in the form of movies).

Some Misconceptions about Literature

Of course, there are a number of misconceptions about literature that have to be gotten out of the way before anyone can enjoy it. One misconception is that literature is full of hidden meanings . There are certainly occasional works that contain hidden meanings. The biblical book of Revelation , for example, was written in a kind of code, using images that had specific meanings for its early audience but that we can only recover with a great deal of difficulty. Most literary works, however, are not at all like that. Perhaps an analogy will illustrate this point. When I take my car to my mechanic because something is not working properly, he opens the hood and we both stand there looking at the engine. But after we have looked for a few minutes, he is likely to have seen what the problem is, while I could look for hours and never see it. We are looking at the same thing. The problem is not hidden, nor is it in some secret code. It is right there in the open, accessible to anyone who knows how to “read” it, which my mechanic does and I do not. He has been taught how to “read” automobile engines and he has practiced “reading” them. He is a good “close reader,” which is why I continue to take my car to him.

The same thing is true for readers of literature. Generally authors want to communicate with their readers, so they are not likely to hide or disguise what they are saying, but reading literature also requires some training and some practice. Good writers use language very carefully, and readers must learn how to be sensitive to that language, just as the mechanic must learn to be sensitive to the appearances and sounds of the engine. Everything that the writer wants to say, and much that the writer may not be aware of, is there in the words. We simply have to learn how to read them.

Another popular misconception is that a literary work has a single “meaning” (and that only English teachers know how to find that meaning). There is an easy way to dispel this misconception. Just go to a college library and find the section that holds books on Shakespeare. Choose one play, Hamlet , for example, and see how many books there are about it, all by scholars who are educated, perceptive readers. Can it be the case that one of these books is correct and all the others are mistaken? And if the correct one has already been written, why would anyone need to write another book about the play? The answer is this:

Key Takeaways

There is no single correct way to read any piece of literature.

Again, let me use an analogy to illustrate this point. Suppose that everyone at a meeting were asked to describe a person who was standing in the middle of the room. Imagine how many different descriptions there would be, depending on where the viewer sat in relation to the person. For example, an optometrist in the crowd might focus on the person’s glasses; a hair stylist might focus on the person’s haircut; someone who sells clothing might focus on the style of dress; a podiatrist might focus on the person’s feet. Would any of these descriptions be incorrect? Not necessarily, but they would be determined by the viewers’ perspectives. They might also be determined by such factors as the viewers’ ages, genders, or ability to move around the person being viewed, or by their previous acquaintance with the subject. So whose descriptions would be correct? Conceivably all of them, and if we put all of these correct descriptions together, we would be closer to having a full description of the person.

This is most emphatically NOT to say, however, that all descriptions are correct simply because each person is entitled to his or her opinion

If the podiatrist is of the opinion that the person is five feet, nine inches tall, the podiatrist could be mistaken. And even if the podiatrist actually measures the person, the measurement could be mistaken. Everyone who describes this person, therefore, must offer not only an opinion but also a basis for that opinion. “My feeling is that this person is a teacher” is not enough. “My feeling is that this person is a teacher because the person’s clothing is covered with chalk dust and because the person is carrying a stack of papers that look like they need grading” is far better, though even that statement might be mistaken.

So it is with literature. As we read, as we try to understand and interpret, we must deal with the text that is in front of us ; but we must also recognize (1) that language is slippery and (2) that each of us individually deals with it from a different set of perspectives. Not all of these perspectives are necessarily legitimate, and it is always possible that we might misread or misinterpret what we see. Furthermore, it is possible that contradictory readings of a single work will both be legitimate, because literary works can be as complex and multi-faceted as human beings. It is vital, therefore, that in reading literature we abandon both the idea that any individual’s reading of a work is the “correct” one and the idea that there is one simple way to read any work. Our interpretations may, and probably should, change according to the way we approach the work. If we read The Chronicles of Narnia as teenagers, then in middle age, and then in old age, we might be said to have read three different books. Thus, multiple interpretations, even contradictory interpretations, can work together to give us a fuller and possibly more interesting understanding of a work.

Why Reading Literature is Important

Reading literature can teach us new ways to read, think, imagine, feel, and make sense of our own experiences. Literature forces readers to confront the complexities of the world, to confront what it means to be a human being in this difficult and uncertain world, to confront other people who may be unlike them, and ultimately to confront themselves.

The relationship between the reader and the world of a work of literature is complex and fascinating. Frequently when we read a work, we become so involved in it that we may feel that we have become part of it. “I was really into that movie,” we might say, and in one sense that statement can be accurate. But in another sense it is clearly inaccurate, for actually we do not enter the movie or the story as IT enters US; the words enter our eyes in the form of squiggles on a page which are transformed into words, sentences, paragraphs, and meaningful concepts in our brains, in our imaginations, where scenes and characters are given “a local habitation and a name.” Thus, when we “get into” a book, we are actually “getting into” our own mental conceptions that have been produced by the book, which, incidentally, explains why so often readers are dissatisfied with cinematic or television adaptations of literary works.

In fact, though it may seem a trite thing to say, writers are close observers of the world who are capable of communicating their visions, and the more perspectives we have to draw on, the better able we should be to make sense of our lives. In these terms, it makes no difference whether we are reading a Homeric epic poem like The Odysse y, a twelfth-century Japanese novel like The Tale of Genji , or a Victorian novel by Dickens, or even, in a sense, watching someone’s TikTok video (a video or movie is also a kind of text that can be “read” or analyzed for multiple meanings). The more different perspectives we get, the better. And it must be emphasized that we read such works not only to be well-rounded (whatever that means) or to be “educated” or for antiquarian interest. We read them because they have something to do with us, with our lives. Whatever culture produced them, whatever the gender or race or religion of their authors, they relate to us as human beings; and all of us can use as many insights into being human as we can get. Reading is itself a kind of experience, and while we may not have the time or the opportunity or or physical possibility to experience certain things in the world, we can experience them through reading. So literature allows us to broaden our experiences.

Reading also forces us to focus our thoughts. The world around us is so full of stimuli that we are easily distracted. Unless we are involved in a crisis that demands our full attention, we flit from subject to subject. But when we read a book, even a book that has a large number of characters and covers many years, the story and the writing help us to focus, to think about what they show us in a concentrated manner. When I hold a book, I often feel that I have in my hand another world that I can enter and that will help me to understand the everyday world that I inhabit.

Literature invites us to meet interesting characters and to visit interesting places, to use our imagination and to think about things that might otherwise escape our notice, to see the world from perspectives that we would otherwise not have.

Watch this video for a discussion of why reading fiction matters.

How to Read Literature: The Basics

- Read with a pen in hand! Yes, even if you’re reading an electronic text, in which case you may want to open a new document in which you can take notes. Jot down questions, highlight things you find significant, mark confusing passages, look up unfamiliar words/references, and record first impressions.

- Think critically to form a response. Here are some things to be aware of and look for in the story that may help you form an idea of meaning.

- Repetitions . You probably know from watching movies that if something is repeated, that means something. Stories are similar—if something occurs more than once, the story is calling attention to it, so notice it and consider why it is repeated. The repeated element can be a word or a phrase, an action, even a piece of clothing or gear.

- Not Quite Right : If something that happens that seems Not Quite Right to you, that may also have some particular meaning. So, for example, if a violent act is committed against someone who’s done nothing wrong, that is unusual, unexpected, that is, Not Quite Right. And therefore, that act means something.

- Address your own biases and compare your own experiences with those expressed in the piece.

- Test your positions and thoughts about the piece with what others think (we’ll do some of this in class discussions).

While you will have your own individual connection to a piece based on your life experiences, interpreting literature is not a willy-nilly process. Each piece of writing has purpose, usually more than one purpose–you, as the reader, are meant to uncover purpose in the text. As the speaker notes in the video you watched about how to read literature, you, as a reader, also have a role to play. Sometimes you may see something in the text that speaks to you; whether or not the author intended that piece to be there, it still matters to you.

For example, I’ve had a student who had life experiences that she was reminded of when reading “Chonguita, the Monkey Bride” and another student whose experience was mirrored in part of “The Frog King or Iron Heinrich.” I encourage you to honor these perceptions if they occur to you and possibly even to use them in your writing assignments. I can suggest ways to do this if you’re interested.

But remember that when we write about literature, our observations must also be supported by the text itself. Make sure you aren’t reading into the text something that isn’t there. Value the text for what is and appreciate the experience it provides, all while you attempt to create a connection with your experiences.

Attributions:

- Content written by Dr. Karen Palmer and licensed CC BY NC SA .

- Content adapted from Literature, the Humanities, and Humanity by Theodore L. Steinberg and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The Worry Free Writer by Dr. Karen Palmer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Introduction to Literature Copyright © by Judy Young is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

What Literature Can Teach Us

Communication and research skills—and how to be a better human being

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., English Literature, California State University - Sacramento

- B.A., English, California State University - Sacramento

Literature is a term used to describe written and sometimes spoken material. Derived from the Latin word literature meaning "writing formed with letters," literature most commonly refers to works of the creative imagination, including poetry, drama , fiction , nonfiction , and in some instances, journalism , and song.

What Is Literature?

Simply put, literature represents the culture and tradition of a language or a people. The concept is difficult to precisely define, though many have tried; it's clear that the accepted definition of literature is constantly changing and evolving.

For many, the word literature suggests a higher art form; merely putting words on a page doesn't necessarily equate to creating literature. A canon is the accepted body of works for a given author. Some works of literature are considered canonical, that is, culturally representative of a particular genre (poetry, prose, or drama).

Literary Fiction vs. Genre Fiction

Some definitions also separate literary fiction from so-called "genre fiction," which includes types such as mystery, science fiction, western, romance, thriller, and horror. Think mass-market paperback.

Genre fiction typically does not have as much character development as literary fiction and is read for entertainment, escapism, and plot, whereas literary fiction explores themes common to the human condition and uses symbolism and other literary devices to convey the author's viewpoint on his or her chosen themes. Literary fiction involves getting into the minds of the characters (or at least the protagonist) and experiencing their relationships with others. The protagonist typically comes to a realization or changes in some way during the course of a literary novel.

(The difference in type does not mean that literary writers are better than genre fiction writers, just that they operate differently.)

Why Is Literature Important?

Works of literature, at their best, provide a kind of blueprint of human society. From the writings of ancient civilizations such as Egypt and China to Greek philosophy and poetry, from the epics of Homer to the plays of William Shakespeare, from Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte to Maya Angelou , works of literature give insight and context to all the world's societies. In this way, literature is more than just a historical or cultural artifact; it can serve as an introduction to a new world of experience.

But what we consider to be literature can vary from one generation to the next. For instance, Herman Melville's 1851 novel " Moby Dick " was considered a failure by contemporary reviewers. However, it has since been recognized as a masterpiece and is frequently cited as one of the best works of Western literature for its thematic complexity and use of symbolism. By reading "Moby Dick" in the present day, we can gain a fuller understanding of literary traditions in Melville's time.

Debating Literature

Ultimately, we may discover meaning in literature by looking at what the author writes or says and how he or she says it. We may interpret and debate an author's message by examining the words he or she chooses in a given novel or work or observing which character or voice serves as the connection to the reader.

In academia, this decoding of the text is often carried out through the use of literary theory using a mythological, sociological, psychological, historical, or other approaches to better understand the context and depth of a work.

Whatever critical paradigm we use to discuss and analyze it, literature is important to us because it speaks to us, it is universal, and it affects us on a deeply personal level.

School Skills

Students who study literature and read for pleasure have a higher vocabulary, better reading comprehension, and better communication skills, such as writing ability. Communication skills affect people in every area of their lives, from navigating interpersonal relationships to participating in meetings in the workplace to drafting intraoffice memos or reports.

When students analyze literature, they learn to identify cause and effect and are applying critical thinking skills. Without realizing it, they examine the characters psychologically or sociologically. They identify the characters' motivations for their actions and see through those actions to any ulterior motives.

When planning an essay on a work of literature, students use problem-solving skills to come up with a thesis and follow through on compiling their paper. It takes research skills to dig up evidence for their thesis from the text and scholarly criticism, and it takes organizational skills to present their argument in a coherent, cohesive manner.

Empathy and Other Emotions

Some studies say that people who read literature have more empathy for others, as literature puts the reader into another person's shoes. Having empathy for others leads people to socialize more effectively, solve conflicts peacefully, collaborate better in the workplace, behave morally, and possibly even become involved in making their community a better place.

Other studies note a correlation between readers and empathy but do not find causation . Either way, studies back the need for strong English programs in schools, especially as people spend more and more time looking at screens rather than books.

Along with empathy for others, readers can feel a greater connection to humanity and less isolated. Students who read literature can find solace as they realize that others have gone through the same things that they are experiencing or have experienced. This can be a catharsis and relief to them if they feel burdened or alone in their troubles.

Quotes About Literature

Here are some quotes about literature from literature giants themselves.

- Robert Louis Stevenson : "The difficulty of literature is not to write, but to write what you mean; not to affect your reader, but to affect him precisely as you wish."

- Jane Austen, "Northanger Abbey" : "The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid."

- William Shakespeare, "Henry VI" : “I’ll call for pen and ink and write my mind.”

- A List of Every Nobel Prize Winner in English Literature

- A Brief History of English Literature

- Are Literature and Fiction the Same?

- Literature Quotes and Sayings

- What Is the Canon in Literature?

- Every Character in Moby Dick

- Stylistics and Elements of Style in Literature

- Literature Definitions: What Makes a Book a Classic?

- literary present (verbs)

- What's the Difference Between Classical and Classic Literature?

- How to Identify the Theme in a Literary Work

- 5 Classic Novels Everyone Should Read

- Use a Concept Map for Your Literature Midterms and Finals

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- What Is a Modern Classic in Literature?

- 5 Novel Setting Maps for Classic American Literature

On The Site

Photo by Roman Kraft on Unsplash

What Is Literature?

December 23, 2019 | yalepress | Literature

Terry Eagleton —

One of the things we mean by calling a piece of writing ‘literary’ is that it is not tied to a specific context. It is true that all literary works arise from particular conditions. Jane Austen’s novels spring from the world of the English landed gentry of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, while Paradise Lost has as its backdrop the English Civil War and its aftermath. Yet though these works emerge from such contexts, their meaning is not confined to them. Consider the difference between a poem and a manual for assembling a table lamp. The manual makes sense only in a specific, practical situation. Unless we are really starved for inspiration, we do not generally turn to it in order to reflect on the mystery of birth or the frailty of humankind. A poem, by contrast, can still be meaningful outside its original context, and may alter its meaning as it moves from one place or time to another. Like a baby, it is detached from its author as soon as it enters the world. All literary works are orphaned at birth. Rather as our parents do not continue to govern our lives as we grow up, so the poet cannot determine the situations in which his or her work will be read, or what sense we are likely to make of it.

What we call works of literature differ in this way from roadsigns and bus tickets. They are peculiarly ‘portable’, able to be carried from one location to another, which is true of bus tickets only for those intent on defrauding the bus company. They are less dependent for their meaning on the circumstances from which they arose. Rather, they are inherently open ended, which is one reason why they can be subject to a whole range of interpretations. It is also one reason why we tend to pay closer attention to their language than we do with bus tickets. We do not take their language primarily as practical. Instead, we assume that it is intended to have some value in itself.

This is not so true of everyday language. A panic-stricken shout of ‘Man overboard!’ is rarely ambiguous. We do not normally treat it as a delectable piece of wordplay. If we hear this cry while on board ship, we are unlikely to linger over the way the vowel-sound of ‘board’ rings a subtle change on the vowel-sound of ‘Over’, or note the fact that the stresses of the shout fall on the first and last syllables. Nor would we pause to read some symbolic meaning into it. We do not take the word ‘Man’ to signify humanity as such, or the whole phrase as suggestive of our calamitous fall from grace. We might well do all this if the man overboard in question is our mortal enemy, aware that by the time we were through with our analysis he would be food for the fishes. Otherwise, however, we are unlikely to scratch our heads over what on earth these words could mean. Their meaning is made apparent by their environment. This would still be the case even if the cry was a hoax. If we were not at sea the cry might make no sense, but hearing the chugging of the ship’s engines settles the matter definitively.

In most practical settings, we do not have much of a choice over meaning. It tends to be determined by the setting itself. Or at least, the situation narrows down the range of possible meanings to a manageable few. When I see an exit sign over the door of a department store, I know from the context that it means ‘This is the way out when you want to leave’, not ‘Leave now!’ Otherwise such stores would be permanently empty. The word is descriptive rather than imperative. I take the instruction ‘One tablet to be taken three times daily’ on my bottle of aspirin to be addressed to me, not to all two hundred people in my apartment block. A driver who flashes his lights may mean either ‘Watch it!’ or ‘Come on!’, but this potentially fatal ambiguity results in fewer road accidents than one might expect, since the meaning is usually clear from the situation.

The problem with a poem or story, however, is that it does not arrive as part of a practical context. It is true that we know from words such as ‘poem’, ‘novel’, ‘epic’, ‘comedy’ and so on what sort of thing to expect, just as the way a literary work is packaged, advertised, marketed and reviewed plays an important part in determining our response to it. Beyond these vital signals, however, the work does not come to us with much of a setting at all. Instead, it creates its own setting as it goes along. We have to figure out from what it says a background against which what it says will make some sense. In fact, we are continually constructing such interpretative frames as we read, for the most part unconsciously. When we read Shakespeare’s line ‘Farewell! Thou art too dear for my possessing’, we think to ourselves, ‘Ah, he’s probably talking to his lover, and it looks as though they’re breaking up. Too dear for his possessing, eh? Maybe she’s been a bit too free with his money’. But there is nothing beyond the words themselves to inform us of this, as there is something beyond a cry of ‘Fire!’ to tell us how to make sense of it. (The smouldering hair of the person doing the shouting, for example.) And this makes the business of determining a literary work’s meaning rather more arduous.

From How to Read Literature by Terry Eagleton. Published by Yale University Press in 2019. Reproduced with permission.

Terry Eagleton is Distinguished Visiting Professor of English Literature at Lancaster University and the author of more than fifty books in the fields of literary theory, postmodernism, politics, ideology, and religion.

Further Reading:

Recent Posts

- A Watershed Moment in Naval History

- Ep. 136 – All About Portraits

- Karla Kelsey on Mina Loy’s Lost Writings

- The American Revolution, Today

- Rochelle Gurstein on The Ephemeral Life of the Classic in Art

- Plastic Money: The Rise of Credit Cards and the Banks that Created Them

Sign up for updates on new releases and special offers

Newsletter signup, shipping location.

Our website offers shipping to the United States and Canada only. For customers in other countries:

Mexico and South America: Contact TriLiteral to place your order. All Others: Visit our Yale University Press London website to place your order.

Shipping Updated

Learn more about Schreiben lernen, 2nd Edition, available now.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

Literary Theory

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing this subject:

Quick Reference

A body of written works related by subject-matter (e.g. the literature of computing), by language or place of origin (e.g. Russian literature), or by prevailing cultural standards of merit. In this last sense, ‘literature’ is taken to include oral, dramatic, and broadcast compositions that may not have been published in written form but which have been (or deserve to be) preserved. Since the 19th century, the broader sense of literature as a totality of written or printed works has given way to more exclusive definitions based on criteria of imaginative, creative, or artistic value, usually related to a work's absence of factual or practical reference (see autotelic). Even more restrictive has been the academic concentration upon poetry, drama, and fiction. Until the mid-20th century, many kinds of non-fictional writing—in philosophy, history, biography, criticism, topography, science, and politics—were counted as literature; implicit in this broader usage is a definition of literature as that body of works which—for whatever reason—deserves to be preserved as part of the current reproduction of meanings within a given culture (unlike yesterday's newspaper, which belongs in the disposable category of ephemera). This sense seems more tenable than the later attempts to divide literature—as creative, imaginative, fictional, or non-practical—from factual writings or practically effective works of propaganda, rhetoric, or didactic writing. The Russian Formalists' attempt to define literariness in terms of linguistic deviations is important in the theory of poetry, but has not addressed the more difficult problem of the non-fictional prose forms. See also belles-lettres , canon, paraliterature. For a fuller account, consult Peter Widdowson, Literature (1998).

From: literature in The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms »

Subjects: Literature

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries.

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'literature' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 03 June 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Character limit 500 /500

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of literature

Examples of literature in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'literature.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Latin litteratura writing, grammar, learning, from litteratus

15th century, in the meaning defined at sense 4

Phrases Containing literature

- gray literature

Articles Related to literature

Famous Novels, Last Lines

Needless to say, spoiler alert.

New Adventures in 'Cli-Fi'

Taking the temperature of a literary genre.

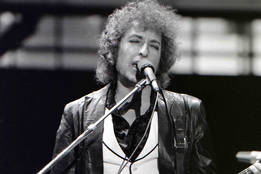

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan...

Trending: 'Literature' As Bob Dylan Sees It

We know how the Nobel Prize committee defines literature, but how does the dictionary?

Dictionary Entries Near literature

literature search

Cite this Entry

“Literature.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/literature. Accessed 3 Jun. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of literature, more from merriam-webster on literature.

Nglish: Translation of literature for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of literature for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about literature

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - may 31, pilfer: how to play and win, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, etymologies for every day of the week, games & quizzes.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability