Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Patient Case Presentation

Mr. E.A. is a 40-year-old black male who presented to his Primary Care Provider for a diabetes follow up on October 14th, 2019. The patient complains of a general constant headache that has lasted the past week, with no relieving factors. He also reports an unusual increase in fatigue and general muscle ache without any change in his daily routine. Patient also reports occasional numbness and tingling of face and arms. He is concerned that these symptoms could potentially be a result of his new diabetes medication that he began roughly a week ago. Patient states that he has not had any caffeine or smoked tobacco in the last thirty minutes. During assessment vital signs read BP 165/87, Temp 97.5 , RR 16, O 98%, and HR 86. E.A states he has not lost or gained any weight. After 10 mins, the vital signs were retaken BP 170/90, Temp 97.8, RR 15, O 99% and HR 82. Hg A1c 7.8%, three months prior Hg A1c was 8.0%. Glucose 180 mg/dL (fasting). FAST test done; negative for stroke. CT test, Chem 7 and CBC have been ordered.

Past medical history

Diagnosed with diabetes (type 2) at 32 years old

Overweight, BMI of 31

Had a cholecystomy at 38 years old

Diagnosed with dyslipidemia at 32 years old

Past family history

Mother alive, diagnosed diabetic at 42 years old

Father alive with Hypertension diagnosed at 55 years old

Brother alive and well at 45 years old

Sister alive and obese at 34 years old

Pertinent social history

Social drinker on occasion

Smokes a pack of cigarettes per day

Works full time as an IT technician and is in graduate school

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Graphical Abstracts and Tidbit

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About American Journal of Hypertension

- Editorial Board

- Board of Directors

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- AJH Summer School

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Clinical management and treatment decisions, hypertension in black americans, pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in black americans.

- < Previous

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Suzanne Oparil, Case study, American Journal of Hypertension , Volume 11, Issue S8, November 1998, Pages 192S–194S, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(98)00195-2

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Ms. C is a 42-year-old black American woman with a 7-year history of hypertension first diagnosed during her last pregnancy. Her family history is positive for hypertension, with her mother dying at 56 years of age from hypertension-related cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition, both her maternal and paternal grandparents had CVD.

At physician visit one, Ms. C presented with complaints of headache and general weakness. She reported that she has been taking many medications for her hypertension in the past, but stopped taking them because of the side effects. She could not recall the names of the medications. Currently she is taking 100 mg/day atenolol and 12.5 mg/day hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ), which she admits to taking irregularly because “... they bother me, and I forget to renew my prescription.” Despite this antihypertensive regimen, her blood pressure remains elevated, ranging from 150 to 155/110 to 114 mm Hg. In addition, Ms. C admits that she has found it difficult to exercise, stop smoking, and change her eating habits. Findings from a complete history and physical assessment are unremarkable except for the presence of moderate obesity (5 ft 6 in., 150 lbs), minimal retinopathy, and a 25-year history of smoking approximately one pack of cigarettes per day. Initial laboratory data revealed serum sodium 138 mEq/L (135 to 147 mEq/L); potassium 3.4 mEq/L (3.5 to 5 mEq/L); blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 19 mg/dL (10 to 20 mg/dL); creatinine 0.9 mg/dL (0.35 to 0.93 mg/dL); calcium 9.8 mg/dL (8.8 to 10 mg/dL); total cholesterol 268 mg/dL (< 245 mg/dL); triglycerides 230 mg/dL (< 160 mg/dL); and fasting glucose 105 mg/dL (70 to 110 mg/dL). The patient refused a 24-h urine test.

Taking into account the past history of compliance irregularities and the need to take immediate action to lower this patient’s blood pressure, Ms. C’s pharmacologic regimen was changed to a trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril, 5 mg/day; her HCTZ was discontinued. In addition, recommendations for smoking cessation, weight reduction, and diet modification were reviewed as recommended by the Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VI). 1

After a 3-month trial of this treatment plan with escalation of the enalapril dose to 20 mg/day, the patient’s blood pressure remained uncontrolled. The patient’s medical status was reviewed, without notation of significant changes, and her antihypertensive therapy was modified. The ACE inhibitor was discontinued, and the patient was started on the angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) losartan, 50 mg/day.

After 2 months of therapy with the ARB the patient experienced a modest, yet encouraging, reduction in blood pressure (140/100 mm Hg). Serum electrolyte laboratory values were within normal limits, and the physical assessment remained unchanged. The treatment plan was to continue the ARB and reevaluate the patient in 1 month. At that time, if blood pressure control remained marginal, low-dose HCTZ (12.5 mg/day) was to be added to the regimen.

Hypertension remains a significant health problem in the United States (US) despite recent advances in antihypertensive therapy. The role of hypertension as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is well established. 2–7 The age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension in non-Hispanic black Americans is approximately 40% higher than in non-Hispanic whites. 8 Black Americans have an earlier onset of hypertension and greater incidence of stage 3 hypertension than whites, thereby raising the risk for hypertension-related target organ damage. 1 , 8 For example, hypertensive black Americans have a 320% greater incidence of hypertension-related end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 80% higher stroke mortality rate, and 50% higher CVD mortality rate, compared with that of the general population. 1 , 9 In addition, aging is associated with increases in the prevalence and severity of hypertension. 8

Research findings suggest that risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, particularly the role of blood pressure, may be different for black American and white individuals. 10–12 Some studies indicate that effective treatment of hypertension in black Americans results in a decrease in the incidence of CVD to a level that is similar to that of nonblack American hypertensives. 13 , 14

Data also reveal differences between black American and white individuals in responsiveness to antihypertensive therapy. For instance, studies have shown that diuretics 15 , 16 and the calcium channel blocker diltiazem 16 , 17 are effective in lowering blood pressure in black American patients, whereas β-adrenergic receptor blockers and ACE inhibitors appear less effective. 15 , 16 In addition, recent studies indicate that ARB may also be effective in this patient population.

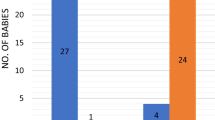

Angiotensin-II receptor blockers are a relatively new class of agents that are approved for the treatment of hypertension. Currently, four ARB have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, and valsartan. Recently, a 528-patient, 26-week study compared the efficacy of eprosartan (200 to 300 mg/twice daily) versus enalapril (5 to 20 mg/daily) in patients with essential hypertension (baseline sitting diastolic blood pressure [DBP] 95 to 114 mm Hg). After 3 to 5 weeks of placebo, patients were randomized to receive either eprosartan or enalapril. After 12 weeks of therapy within the titration phase, patients were supplemented with HCTZ as needed. In a prospectively defined subset analysis, black American patients in the eprosartan group (n = 21) achieved comparable reductions in DBP (−13.3 mm Hg with eprosartan; −12.4 mm Hg with enalapril) and greater reductions in systolic blood pressure (SBP) (−23.1 with eprosartan; −13.2 with enalapril), compared with black American patients in the enalapril group (n = 19) ( Fig. 1 ). 18 Additional trials enrolling more patients are clearly necessary, but this early experience with an ARB in black American patients is encouraging.

Efficacy of the angiotensin II receptor blocker eprosartan in black American with mild to moderate hypertension (baseline sitting DBP 95 to 114 mm Hg) in a 26-week study. Eprosartan, 200 to 300 mg twice daily (n = 21, solid bar), enalapril 5 to 20 mg daily (n = 19, diagonal bar). †10 of 21 eprosartan patients and seven of 19 enalapril patients also received HCTZ. Adapted from data in Levine: Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study, in Programs and abstracts from the 1st International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism, September 28–October 1, 1997, London, UK.

00195-2/2/m_ajh.192S.f1.jpeg?Expires=1719112609&Signature=cvpO6nOV9rurlE9jEgz~8EFmfBlZMmkLnBdQW5bvYyqRvHhRx7M38OoYB63QSNTFir6JYz-NrU5ZSru9g7i-CAAsuY54yxj-Yrc7f8yuJDwf93UghhaPxjy2wb3QxtUezKBjShLhYpqagSXXc2G7aXIXOsp2sEkER2F~jfZ5mgm21qedKErPw5KxlQcQgW4fHR-Bbt5ySRi0tC8Kof3AF4wK09OnHg-0TvgTvwNrmuynf-HpSdFI78JhfZZeDdQqSlub3Sq~-UfCarHvqHEF4u~j32IeHfNjZTfE-cKNgHzMG6va1JqkR1aAFiz0QkfU08WF9RjirZ4zVuMf9ajwTA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Approximately 30% of all deaths in hypertensive black American men and 20% of all deaths in hypertensive black American women are attributable to high blood pressure. Black Americans develop high blood pressure at an earlier age, and hypertension is more severe in every decade of life, compared with whites. As a result, black Americans have a 1.3 times greater rate of nonfatal stroke, a 1.8 times greater rate of fatal stroke, a 1.5 times greater rate of heart disease deaths, and a 5 times greater rate of ESRD when compared with whites. 19 Therefore, there is a need for aggressive antihypertensive treatment in this group. Newer, better tolerated antihypertensive drugs, which have the advantages of fewer adverse effects combined with greater antihypertensive efficacy, may be of great benefit to this patient population.

1. Joint National Committee : The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure . Arch Intern Med 1997 ; 24 157 : 2413 – 2446 .

Google Scholar

2. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg . JAMA 1967 ; 202 : 116 – 122 .

3. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension: II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg . JAMA 1970 ; 213 : 1143 – 1152 .

4. Pooling Project Research Group : Relationship of blood pressure, serum cholesterol, smoking habit, relative weight and ECG abnormalities to the incidence of major coronary events: Final report of the pooling project . J Chronic Dis 1978 ; 31 : 201 – 306 .

5. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program: I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension . JAMA 1979 ; 242 : 2562 – 2577 .

6. Kannel WB , Dawber TR , McGee DL : Perspectives on systolic hypertension: The Framingham Study . Circulation 1980 ; 61 : 1179 – 1182 .

7. Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program Cooperative Group : The effect of treatment on mortality in “mild” hypertension: Results of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-Up Program . N Engl J Med 1982 ; 307 : 976 – 980 .

8. Burt VL , Whelton P , Roccella EJ et al. : Prevalence of hypertension in the US adult population: Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1991 . Hypertension 1995 ; 25 : 305 – 313 .

9. Klag MJ , Whelton PK , Randall BL et al. : End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men: 16-year MRFIT findings . JAMA 1997 ; 277 : 1293 – 1298 .

10. Neaton JD , Kuller LH , Wentworth D et al. : Total and cardiovascular mortality in relation to cigarette smoking, serum cholesterol concentration, and diastolic blood pressure among black and white males followed up for five years . Am Heart J 1984 ; 3 : 759 – 769 .

11. Gillum RF , Grant CT : Coronary heart disease in black populations II: Risk factors . Heart J 1982 ; 104 : 852 – 864 .

12. M’Buyamba-Kabangu JR , Amery A , Lijnen P : Differences between black and white persons in blood pressure and related biological variables . J Hum Hypertens 1994 ; 8 : 163 – 170 .

13. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group : Five-year findings of the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program: mortality by race-sex and blood pressure level: a further analysis . J Community Health 1984 ; 9 : 314 – 327 .

14. Ooi WL , Budner NS , Cohen H et al. : Impact of race on treatment response and cardiovascular disease among hypertensives . Hypertension 1989 ; 14 : 227 – 234 .

15. Weinberger MH : Racial differences in antihypertensive therapy: evidence and implications . Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 1990 ; 4 ( suppl 2 ): 379 – 392 .

16. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC et al. : Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men: A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo . N Engl J Med 1993 ; 328 : 914 – 921 .

17. Materson BJ , Reda DJ , Cushman WC for the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Antihypertensive Agents : Department of Veterans Affairs single-drug therapy of hypertension study: Revised figures and new data . Am J Hypertens 1995 ; 8 : 189 – 192 .

18. Levine B : Subgroup analysis of black hypertensive patients treated with eprosartan or enalapril: results of a 26-week study , in Programs and abstracts from the first International Symposium on Angiotensin-II Antagonism , September 28 – October 1 , 1997 , London, UK .

19. American Heart Association: 1997 Heart and Stroke Statistical Update . American Heart Association , Dallas , 1997 .

- hypertension

- blood pressure

- african american

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1941-7225

- Copyright © 2024 American Journal of Hypertension, Ltd.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Newly diagnosed hypertension: case study

Affiliation.

- 1 Trainee Advanced Nurse Practitioner, East Belfast GP Federation, Northern Ireland.

- PMID: 37344134

- DOI: 10.12968/bjon.2023.32.12.556

The role of an advanced nurse practitioner encompasses the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of a range of conditions. This case study presents a patient with newly diagnosed hypertension. It demonstrates effective history taking, physical examination, differential diagnoses and the shared decision making which occurred between the patient and the professional. It is widely acknowledged that adherence to medications is poor in long-term conditions, such as hypertension, but using a concordant approach in practice can optimise patient outcomes. This case study outlines a concordant approach to consultations in clinical practice which can enhance adherence in long-term conditions.

Keywords: Adherence; Advanced nurse practitioner; Case study; Concordance; Hypertension.

- Diagnosis, Differential

- Hypertension* / diagnosis

- Hypertension* / drug therapy

- Nurse Practitioners*

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Abegaz TM, Shehab A, Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Elnour AA. Nonadherence to antihypertensive drugs. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017; 96:(4) https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000005641

Armitage LC, Davidson S, Mahdi A Diagnosing hypertension in primary care: a retrospective cohort study to investigate the importance of night-time blood pressure assessment. Br J Gen Pract. 2023; 73:(726)e16-e23 https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2022.0160

Barratt J. Developing clinical reasoning and effective communication skills in advanced practice. Nurs Stand. 2018; 34:(2)48-53 https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2018.e11109

Bostock-Cox B. Nurse prescribing for the management of hypertension. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2013; 8:(11)531-536

Bostock-Cox B. Hypertension – the present and the future for diagnosis. Independent Nurse. 2019; 2019:(1)20-24 https://doi.org/10.12968/indn.2019.1.20

Chakrabarti S. What's in a name? Compliance, adherence and concordance in chronic psychiatric disorders. World J Psychiatry. 2014; 4:(2)30-36 https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v4.i2.30

De Mauri A, Carrera D, Vidali M Compliance, adherence and concordance differently predict the improvement of uremic and microbial toxins in chronic kidney disease on low protein diet. Nutrients. 2022; 14:(3) https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030487

Demosthenous N. Consultation skills: a personal reflection on history-taking and assessment in aesthetics. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing. 2017; 6:(9)460-464 https://doi.org/10.12968/joan.2017.6.9.460

Diamond-Fox S. Undertaking consultations and clinical assessments at advanced level. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(4)238-243 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.4.238

Diamond-Fox S, Bone H. Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(9)526-532 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.9.526

Donnelly M, Martin D. History taking and physical assessment in holistic palliative care. Br J Nurs. 2016; 25:(22)1250-1255 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2016.25.22.1250

Fawcett J. Thoughts about meanings of compliance, adherence, and concordance. Nurs Sci Q. 2020; 33:(4)358-360 https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318420943136

Fisher NDL, Curfman G. Hypertension—a public health challenge of global proportions. JAMA. 2018; 320:(17)1757-1759 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16760

Green S. Assessment and management of acute sore throat. Pract Nurs. 2015; 26:(10)480-486 https://doi.org/10.12968/pnur.2015.26.10.480

Harper C, Ajao A. Pendleton's consultation model: assessing a patient. Br J Community Nurs. 2010; 15:(1)38-43 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.1.45784

Hitchings A, Lonsdale D, Burrage D, Baker E. The Top 100 Drugs; Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing, 2nd edn. Scotland: Elsevier; 2019

Hobden A. Strategies to promote concordance within consultations. Br J Community Nurs. 2006; 11:(7)286-289 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2006.11.7.21443

Ingram S. Taking a comprehensive health history: learning through practice and reflection. Br J Nurs. 2017; 26:(18)1033-1037 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2017.26.18.1033

James A, Holloway S. Application of concepts of concordance and health beliefs to individuals with pressure ulcers. British Journal of Healthcare Management. 2020; 26:(11)281-288 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjhc.2019.0104

Jamison J. Differential diagnosis for primary care. A handbook for health care practitioners, 2nd edn. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006

History and Physical Examination. 2021. https://patient.info/doctor/history-and-physical-examination (accessed 26 January 2023)

Kumar P, Clark M. Clinical Medicine, 9th edn. The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017

Matthys J, Elwyn G, Van Nuland M Patients' ideas, concerns, and expectations (ICE) in general practice: impact on prescribing. Br J Gen Pract. 2009; 59:(558)29-36 https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X394833

McKinnon J. The case for concordance: value and application in nursing practice. Br J Nurs. 2013; 22:(13)766-771 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2013.22.13.766

McPhillips H, Wood AF, Harper-McDonald B. Conducting a consultation and clinical assessment of the skin for advanced clinical practitioners. Br J Nurs. 2021; 30:(21)1232-1236 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2021.30.21.1232

Moulton L. The naked consultation; a practical guide to primary care consultation skills.Abingdon: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007

Medicine adherence; involving patients in decisions about prescribed medications and supporting adherence.England: NICE; 2009

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. How do I control my blood pressure? Lifestyle options and choice of medicines patient decision aid. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136/resources/patient-decision-aid-pdf-6899918221 (accessed 25 January 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline NG136. 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (accessed 15 June 2023)

Nazarko L. Healthwise, Part 4. Hypertension: how to treat it and how to reduce its risks. Br J Healthc Assist. 2021; 15:(10)484-490 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjha.2021.15.10.484

Neighbour R. The inner consultation.London: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd; 1987

The Code. professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses, midwives and nursing associates.London: NMC; 2018

Nuttall D, Rutt-Howard J. The textbook of non-medical prescribing, 2nd edn. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2016

O'Donovan K. The role of ACE inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2018; 13:(12)600-608 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2018.13.12.600

O'Donovan K. Angiotensin receptor blockers as an alternative to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. British Journal of Cardiac Nursing. 2019; 14:(6)1-12 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjca.2019.0009

Porth CM. Essentials of Pathophysiology, 4th edn. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2015

Rae B. Obedience to collaboration: compliance, adherence and concordance. Journal of Prescribing Practice. 2021; 3:(6)235-240 https://doi.org/10.12968/jprp.2021.3.6.235

Rostoft S, van den Bos F, Pedersen R, Hamaker ME. Shared decision-making in older patients with cancer - What does the patient want?. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021; 12:(3)339-342 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2020.08.001

Schroeder K. The 10-minute clinical assessment, 2nd edn. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2017

Thomas J, Monaghan T. The Oxford handbook of clinical examination and practical skills, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014

Vincer K, Kaufman G. Balancing shared decision-making with ethical principles in optimising medicines. Nurse Prescribing. 2017; 15:(12)594-599 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2017.15.12.594

Waterfield J. ACE inhibitors: use, actions and prescribing rationale. Nurse Prescribing. 2008; 6:(3)110-114 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2008.6.3.28858

Weiss M. Concordance, 6th edn. In: Watson J, Cogan LS Poland: Elsevier; 2019

Williams H. An update on hypertension for nurse prescribers. Nurse Prescribing. 2013; 11:(2)70-75 https://doi.org/10.12968/npre.2013.11.2.70

Adherence to long-term therapies, evidence for action.Geneva: WHO; 2003

Young K, Franklin P, Franklin P. Effective consulting and historytaking skills for prescribing practice. Br J Nurs. 2009; 18:(17)1056-1061 https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2009.18.17.44160

Newly diagnosed hypertension: case study

Angela Brown

Trainee Advanced Nurse Practitioner, East Belfast GP Federation, Northern Ireland

View articles · Email Angela

The role of an advanced nurse practitioner encompasses the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of a range of conditions. This case study presents a patient with newly diagnosed hypertension. It demonstrates effective history taking, physical examination, differential diagnoses and the shared decision making which occurred between the patient and the professional. It is widely acknowledged that adherence to medications is poor in long-term conditions, such as hypertension, but using a concordant approach in practice can optimise patient outcomes. This case study outlines a concordant approach to consultations in clinical practice which can enhance adherence in long-term conditions.

Hypertension is a worldwide problem with substantial consequences ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ). It is a progressive condition ( Jamison, 2006 ) requiring lifelong management with pharmacological treatments and lifestyle adjustments. However, adopting these lifestyle changes can be notoriously difficult to implement and sustain ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ) and non-adherence to chronic medication regimens is extremely common ( Abegaz et al, 2017 ). This is also recognised by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (2009) which estimates that between 33.3% and 50% of medications are not taken as recommended. Abegaz et al (2017) furthered this by claiming 83.7% of people with uncontrolled hypertension do not take medications as prescribed. However, leaving hypertension untreated or uncontrolled is the single largest cause of cardiovascular disease ( Fisher and Curfman, 2018 ). Therefore, better adherence to medications is associated with better outcomes ( World Health Organization, 2003 ) in terms of reducing the financial burden associated with the disease process on the health service, improving outcomes for patients ( Chakrabarti, 2014 ) and increasing job satisfaction for professionals ( McKinnon, 2013 ). Therefore, at a time when growing numbers of patients are presenting with hypertension, health professionals must adopt a concordant approach from the initial consultation to optimise adherence.

Great emphasis is placed on optimising adherence to medications ( NICE, 2009 ), but the meaning of the term ‘adherence’ is not clear and it is sometimes used interchangeably with compliance and concordance ( De Mauri et al, 2022 ), although they are not synonyms. Compliance is an outdated term alluding to paternalism, obedience and passivity from the patient ( Rae, 2021 ), whereby the patient's behaviour must conform to the health professional's recommendations. Adherence is defined as ‘the extent to which a person's behaviour, taking medication, following a diet and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider’ ( Chakrabarti, 2014 ). This term is preferred over compliance as it is less paternalistic ( Rae, 2021 ), as the patient is included in the decision-making process and has agreed to the treatment plan. While it is not yet widely embraced or used in practice ( Fawcett, 2020 ), concordance is recognised, not as a behaviour ( Rae, 2021 ) but more an approach or method which focuses on the equal partnership between patient and professional ( McKinnon, 2013 ) and enables effective and agreed treatment plans.

NICE last reviewed its guidance on medication adherence in 2019 and did not replace adherence with concordance within this. This supports the theory that adherence is an outcome of good concordance and the two are not synonyms. NICE (2009) guidelines, which are still valid, show evidence of concordant principles to maximise adherence. Integrating the theoretical principles of concordance into this case study demonstrates how the trainee advanced nurse practitioner aimed to individualise patient-centred care and improve health outcomes through optimising adherence.

Patient introduction and assessment

Jane (a pseudonym has been used to protect the patient's anonymity; Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) 2018 ), is a 45-year-old woman who had been referred to the surgery following an attendance at an emergency department. Jane had been role-playing as a patient as part of a teaching session for health professionals when it was noted that her blood pressure was significantly elevated at 170/88 mmHg. She had no other symptoms. Following an initial assessment at the emergency department, Jane was advised to contact her GP surgery for review and follow up. Nazarko (2021) recognised that it is common for individuals with high blood pressure to be asymptomatic, contributing to this being referred to as the ‘silent killer’. Hypertension is generally only detected through opportunistic checking of blood pressure, as seen in Jane's case, which is why adults over the age of 40 years are offered a blood pressure check every 5 years ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ).

Consultation

Jane presented for a consultation at the surgery. Green (2015) advocates using a model to provide a structured approach to consultations which ensures quality and safety, and improves time management. Young et al (2009) claimed that no single consultation model is perfect, and Diamond-Fox (2021) suggested that, with experience, professionals can combine models to optimise consultation outcomes. Therefore, to effectively consult with Jane and to adapt to her individual personality, different models were intertwined to provide better person-centred care.

The Calgary–Cambridge model is the only consultation model that places emphasis on initiating the session, despite it being recognised that if a consultation gets off to a bad start this can interfere throughout ( Young et al, 2009 ). Being prepared for the consultation is key. Before Jane's consultation, the environment was checked to minimise interruptions, ensuring privacy and dignity ( Green, 2015 ; NMC, 2018 ), the seating arrangements optimised to aid good body language and communication ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) and her records were viewed to give some background information to help set the scene and develop a rapport ( Young et al, 2009 ). Being adequately prepared builds the patient's trust and confidence in the professional ( Donnelly and Martin, 2016 ) but equally viewing patient information can lead to the professional forming preconceived ideas ( Donnelly and Martin, 2016 ). Therefore, care was taken by the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to remain open-minded.

During Jane's consultation, a thorough clinical history was taken ( Table 1 ). History taking is common to all consultation models and involves gathering important information ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ). History-taking needs to be an effective ( Bostock-Cox, 2019 ), holistic process ( Harper and Ajao, 2010 ) in order to be thorough, safe ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) and aid in an accurate diagnosis. The key skill for taking history is listening and observing the patient ( Harper and Ajao, 2010 ). Sir William Osler said:‘listen to the patient as they are telling you the diagnosis’, but Knott and Tidy (2021) suggested that patients are barely given 20 seconds before being interrupted, after which they withdraw and do not offer any new information ( Demosthenous, 2017 ). Using this guidance, Jane was given the ‘golden minute’ allowing her to tell her ‘story’ without being interrupted ( Green, 2015 ). This not only showed respect ( Ingram, 2017 ) but interest in the patient and their concerns.

Once Jane shared her story, it was important for the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to guide the questioning ( Green 2015 ). This was achieved using a structured approach to take Jane's history, which optimised efficiency and effectiveness, and ensured that pertinent information was not omitted ( Young et al, 2009 ). Thomas and Monaghan (2014) set out clear headings for this purpose. These included:

- The presenting complaint

- Past medical history

- Drug history

- Social history

- Family history.

McPhillips et al (2021) also emphasised a need for a systemic enquiry of the other body systems to ensure nothing is missed. From taking this history it was discovered that Jane had been feeling well with no associated symptoms or red flags. A blood pressure reading showed that her blood pressure was elevated. Jane had no past medical history or allergies. She was not taking any medications, including prescribed, over the counter, herbal or recreational. Jane confirmed that she did not drink alcohol or smoke. There was no family history to note, which is important to clarify as a genetic link to hypertension could account for 30–50% of cases ( Nazarko, 2021 ). The information gathered was summarised back to Jane, showing good practice ( McPhillips et al, 2021 ), and Jane was able to clarify salient or missing points. Green (2015) suggested that optimising the patient's involvement in this way in the consultation makes her feel listened to which enhances patient satisfaction, develops a therapeutic relationship and demonstrates concordance.

During history taking it is important to explore the patient's ideas, concerns and expectations. Moulton (2007) refers to these as the ‘holy trinity’ and central to upholding person-centredness ( Matthys et al, 2009 ). Giving Jane time to discuss her ideas, concerns and expectations allowed the trainee advanced nurse practitioner to understand that she was concerned about her risk of a stroke and heart attack, and worried about the implications of hypertension on her already stressful job. Using ideas, concerns and expectations helped to understand Jane's experience, attitudes and perceptions, which ultimately will impact on her health behaviours and whether engagement in treatment options is likely ( James and Holloway, 2020 ). Establishing Jane's views demonstrated that she was eager to engage and manage her blood pressure more effectively.

Vincer and Kaufman (2017) demonstrated, through their case study, that a failure to ask their patient's viewpoint at the initial consultation meant a delay in engagement with treatment. They recognised that this delay could have been avoided with the use of additional strategies had ideas, concerns and expectations been implemented. Failure to implement ideas, concerns and expectations is also associated with reattendance or the patient seeking second opinions ( Green, 2015 ) but more positively, when ideas, concerns and expectations is implemented, it can reduce the number of prescriptions while sustaining patient satisfaction ( Matthys et al, 2009 ).

Physical examination

Once a comprehensive history was taken, a physical examination was undertaken to supplement this information ( Nuttall and Rutt-Howard, 2016 ). A physical examination of all the body systems is not required ( Diamond-Fox, 2021 ) as this would be extremely time consuming, but the trainee advanced nurse practitioner needed to carefully select which systems to examine and use good examination technique to yield a correct diagnosis ( Knott and Tidy, 2021 ). With informed consent, clinical observations were recorded along with a full cardiovascular examination. The only abnormality discovered was Jane's blood pressure which was 164/90 mmHg, which could suggest stage 2 hypertension ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). However, it is the trainee advanced nurse practitioner's role to use a hypothetico-deductive approach to arrive at a diagnosis. This requires synthesising all the information from the history taking and physical examination to formulate differential diagnoses ( Green, 2015 ) from which to confirm or refute before arriving at a final diagnosis ( Barratt, 2018 ).

Differential diagnosis

Hypertension can be triggered by secondary causes such as certain drugs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, decongestants, sodium-containing medications or combined oral contraception), foods (liquorice, alcohol or caffeine; Jamison, 2006 ), physiological response (pain, anxiety or stress) or pre-eclampsia ( Jamison, 2006 ; Schroeder, 2017 ). However, Jane had clarified that these were not contributing factors. Other potential differentials which could not be ruled out were the white-coat syndrome, renal disease or hyperthyroidism ( Schroeder, 2017 ). Further tests were required, which included bloods, urine albumin creatinine ratio, electrocardiogram and home blood pressure monitoring, to ensure a correct diagnosis and identify any target organ damage.

Joint decision making

At this point, the trainee advanced nurse practitioner needed to share their knowledge in a meaningful way to enable the patient to participate with and be involved in making decisions about their care ( Rostoft et al, 2021 ). Not all patients wish to be involved in decision making ( Hobden, 2006 ) and this must be respected ( NMC, 2018 ). However, engaging patients in partnership working improves health outcomes ( McKinnon, 2013 ). Explaining the options available requires skill so as not to make the professional seem incompetent and to ensure the patient continues to feel safe ( Rostoft et al, 2021 ).

Information supported by the NICE guidelines was shared with Jane. These guidelines advocated that in order to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension, a clinic blood pressure reading of 140/90 mmHg or higher was required, with either an ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring result of 135/85 mmHg or higher ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). However, the results from a new retrospective study suggested that the use of home blood pressure monitoring is failing to detect ‘non-dippers’ or ‘reverse dippers’ ( Armitage et al, 2023 ). These are patients whose blood pressure fails to fall during their nighttime sleep. This places them at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and misdiagnosis if home blood pressure monitors are used, but ambulatory blood pressure monitors are less frequently used in primary care and therefore home blood pressure monitors appear to be the new norm ( Armitage et al, 2023 ).

Having discussed this with Jane she was keen to engage with home blood pressure monitoring in order to confirm the potential diagnosis, as starting a medication without a true diagnosis of hypertension could potentially cause harm ( Jamison, 2006 ). An accurate blood pressure measurement is needed to prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary therapy ( Jamison, 2006 ) and this is dependent on reliable and calibrated equipment and competency in performing the task ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ). Therefore, Jane was given education and training to ensure the validity and reliability of her blood pressure readings.

For Jane, this consultation was the ideal time to offer health promotion advice ( Green, 2015 ) as she was particularly worried about her elevated blood pressure. Offering health promotion advice is a way of caring, showing support and empowerment ( Ingram, 2017 ). Therefore, Jane was provided with information on a healthy diet, the reduction of salt intake, weight loss, exercise and continuing to abstain from smoking and alcohol ( Williams, 2013 ). These were all modifiable factors which Jane could implement straight away to reduce her blood pressure.

Safety netting

The final stage and bringing this consultation to a close was based on the fourth stage of Neighbour's (1987) model, which is safety netting. Safety netting identifies appropriate follow up and gives details to the patient on what to do if their condition changes ( Weiss, 2019 ). It is important that the patient knows who to contact and when ( Young et al, 2009 ). Therefore, Jane was advised that, should she develop chest pains, shortness of breath, peripheral oedema, reduced urinary output, headaches, visual disturbances or retinal haemorrhages ( Schroeder, 2017 ), she should present immediately to the emergency department, otherwise she would be reviewed in the surgery in 1 week.

Jane was followed up in a second consultation 1 week later with her home blood pressure readings. The average reading from the previous 6 days was calculated ( Bostock-Cox, 2013 ) and Jane's home blood pressure reading was 158/82 mmHg. This reading ruled out white-coat syndrome as Jane's blood pressure remained elevated outside clinic conditions (white-coat syndrome is defined as a difference of more than 20/10 mmHg between clinic blood pressure readings and the average home blood pressure reading; NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ). Subsequently, Jane was diagnosed with stage 2 essential (or primary) hypertension. Stage 2 is defined as a clinic blood pressure of 160/100 mmHg or higher or a home blood pressure of 150/95 mmHg or higher ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ).

A diagnosis of hypertension can be difficult for patients as they obtain a ‘sick label’ despite feeling well ( Jamison, 2006 ). This is recognised as a deterrent for their motivation to initiate drug treatment and lifestyle changes ( Williams, 2013 ), presenting a greater challenge to health professionals, which can be addressed through concordance strategies. However, having taken Jane's bloods, electrocardiogram and urine albumin:creatinine ratio in the first consultation, it was evident that there was no target organ damage and her Qrisk3 score was calculated as 3.4%. These results provided reassurance for Jane, but she was keen to engage and prevent any potential complications.

Agreeing treatment

Concordance is only truly practised when the patient's perspectives are valued, shared and used to inform planning ( McKinnon, 2013 ). The trainee advanced nurse practitioner now needed to use the information gained from the consultations to formulate a co-produced and meaningful treatment plan based on the best available evidence ( Diamond-Fox and Bone, 2021 ). Jane understood the risk associated with high blood pressure and was keen to begin medication as soon as possible. NICE guidelines ( 2019 ; 2022 ) advocate the use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin-receptor blockers in patients under 55 years of age and not of Black African or African-Caribbean origin. However, ACE inhibitors seem to be used as the first-line treatment for hypertensive patients under the age of 55 years ( O'Donovan, 2019 ).

ACE inhibitors directly affect the renin–angiotensin-aldosterone system which plays a central role in regulation of blood pressure ( Porth, 2015 ). Renin is secreted by the juxtaglomerular cells, in the kidneys' nephrons, when there is a decrease in renal perfusion and stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system ( O'Donovan, 2018 ). Renin then combines with angiotensinogen, a circulating plasma globulin from the liver, to form angiotensin I ( Kumar and Clark, 2017 ). Angiotensin I is inactive but, through ACE, an enzyme present in the endothelium of the lungs, it is transformed into angiotensin II ( Kumar and Clark, 2017 ). Angiotensin II is a vasoconstrictor which increases vascular resistance and in turn blood pressure ( Porth, 2015 ) while also stimulating the adrenal gland to produce aldosterone. Aldosterone reduces sodium excretion in the kidneys, thus increasing water reabsorption and therefore blood volume ( Porth, 2015 ). Using an ACE inhibitor prevents angiotensin II formation, which prevents vasoconstriction and stops reabsorption of sodium and water, thus reducing blood pressure.

When any new medication is being considered, providing education is key. This must include what the medication is for, the importance of taking it, any contraindications or interactions with the current medications being taken by the patient and the potential risk of adverse effects ( O'Donovan, 2018 ). Sharing this information with Jane allowed her to weigh up the pros and cons and make an informed choice leading to the creation of an individualised treatment plan.

Jamison (2006) placed great emphasis on sharing information about adverse effects, because patients with hypertension feel well before commencing medications, but taking medication has the potential to cause side effects which can affect adherence. Therefore, the range of side effects were discussed with Jane. These include a persistent, dry non-productive cough, hypotension, hypersensitivity, angioedema and renal impairment with hyperkalaemia ( Hitchings et al, 2019 ). ACE inhibitors have a range of adverse effects and most resolve when treatment is stopped ( Waterfield, 2008 ).

Following discussion with Jane, she proceeded with taking an ACE inhibitor and was encouraged to report any side effects in order to find another more suitable medication and to prevent her hypertension from going untreated. This information was provided verbally and written which is seen as good practice ( Green, 2015 ). Jane was followed up with fortnightly blood pressure recordings and urea and electrolyte checks and her dose of ramipril was increased fortnightly until her blood pressure was under 140/90 mmHg ( NICE, 2019 ; 2022 ).

Conclusions

Adherence to medications can be difficult to establish and maintain, especially for patients with long-term conditions. This can be particularly challenging for patients with hypertension because they are generally asymptomatic, yet acquire a sick label and start lifelong medication and lifestyle adjustments to prevent complications. Through adopting a concordant approach in practice, the outcome of adherence can be increased. This case study demonstrates how concordant strategies were implemented throughout the consultation to create a therapeutic patient–professional relationship. This optimised the creation of an individualised treatment plan which the patient engaged with and adhered to.

- Hypertension is a growing worldwide problem

- Appropriate clinical assessment, diagnosis and management is key to prevent misdiagnosis

- Long-term conditions are associated with high levels of non-adherence to treatments

- Adopting a concordance approach to practice optimises adherence and promotes positive patient outcomes

CPD reflective questions

- How has this article developed your assessment, diagnosis or management of patients presenting with a high blood pressure?

- What measures can you implement in your practice to enhance a concordant approach?

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 6: 10 Real Cases on Hypertensive Emergency and Pericardial Disease: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Niel Shah; Fareeha S. Alavi; Muhammad Saad

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion.

- Clinical Symptoms

- Diagnostic Evaluation

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Management of Hypertensive Encephalopathy

A 45-year-old man with a 2-month history of progressive headache presented to the emergency department with nausea, vomiting, visual disturbance, and confusion for 1 day. He denied fever, weakness, numbness, shortness of breath, and flulike symptoms. He had significant medical history of hypertension and was on a β-blocker in the past, but a year ago, he stopped taking medication due to an unspecified reason. The patient denied any history of tobacco smoking, alcoholism, and recreational drug use. The patient had a significant family history of hypertension in both his father and mother. Physical examination was unremarkable, and at the time of triage, his blood pressure (BP) was noted as 195/123 mm Hg, equal in both arms. The patient was promptly started on intravenous labetalol with the goal to reduce BP by 15% to 20% in the first hour. The BP was rechecked after an hour of starting labetalol and was 165/100 mm Hg. MRI of the brain was performed in the emergency department and demonstrated multiple scattered areas of increased signal intensity on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images in both the occipital and posterior parietal lobes. There were also similar lesions in both hemispheres of the cerebellum (especially the cerebellar white matter on the left) as well as in the medulla oblongata. The lesions were not associated with mass effect, and after contrast administration, there was no evidence of abnormal enhancement. In the emergency department, his BP decreased to 160/95 mm Hg, and he was transitioned from drip to oral medications and transferred to the telemetry floor. How would you manage this case?

The patient initially presented with headache, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, and confusion. The patient’s BP was found to be 195/123 mm Hg, and MRI of the brain demonstrated scattered lesions with increased intensity in the occipital and posterior parietal lobes, as well as in cerebellum and medulla oblongata. The clinical presentation, elevated BP, and brain MRI findings were suggestive of hypertensive emergency, more specifically hypertensive encephalopathy. These MRI changes can be seen particularly in posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES), a sequela of hypertensive encephalopathy. BP was initially controlled by labetalol, and after satisfactory control of BP, the patient was switched to oral antihypertensive medications.

Hypertensive emergency refers to the elevation of systolic BP >180 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >120 mm Hg that is associated with end-organ damage; however, in some conditions such as pregnancy, more modest BP elevation can constitute an emergency. An equal degree of hypertension but without end-organ damage constitutes a hypertensive urgency, the treatment of which requires gradual BP reduction over several hours. Patients with hypertensive emergency require rapid, tightly controlled reductions in BP that avoid overcorrection. Management typically occurs in an intensive care setting with continuous arterial BP monitoring and continuous infusion of antihypertensive agents.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Presentation

Clinical pearls, case study: treating hypertension in patients with diabetes.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Evan M. Benjamin; Case Study: Treating Hypertension in Patients With Diabetes. Clin Diabetes 1 July 2004; 22 (3): 137–138. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaclin.22.3.137

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

L.N. is a 49-year-old white woman with a history of type 2 diabetes,obesity, hypertension, and migraine headaches. The patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 9 years ago when she presented with mild polyuria and polydipsia. L.N. is 5′4″ and has always been on the large side,with her weight fluctuating between 165 and 185 lb.

Initial treatment for her diabetes consisted of an oral sulfonylurea with the rapid addition of metformin. Her diabetes has been under fair control with a most recent hemoglobin A 1c of 7.4%.

Hypertension was diagnosed 5 years ago when blood pressure (BP) measured in the office was noted to be consistently elevated in the range of 160/90 mmHg on three occasions. L.N. was initially treated with lisinopril, starting at 10 mg daily and increasing to 20 mg daily, yet her BP control has fluctuated.

One year ago, microalbuminuria was detected on an annual urine screen, with 1,943 mg/dl of microalbumin identified on a spot urine sample. L.N. comes into the office today for her usual follow-up visit for diabetes. Physical examination reveals an obese woman with a BP of 154/86 mmHg and a pulse of 78 bpm.

What are the effects of controlling BP in people with diabetes?

What is the target BP for patients with diabetes and hypertension?

Which antihypertensive agents are recommended for patients with diabetes?

Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). Approximately two-thirds of people with diabetes die from complications of CVD. Nearly half of middle-aged people with diabetes have evidence of coronary artery disease (CAD), compared with only one-fourth of people without diabetes in similar populations.

Patients with diabetes are prone to a number of cardiovascular risk factors beyond hyperglycemia. These risk factors, including hypertension,dyslipidemia, and a sedentary lifestyle, are particularly prevalent among patients with diabetes. To reduce the mortality and morbidity from CVD among patients with diabetes, aggressive treatment of glycemic control as well as other cardiovascular risk factors must be initiated.

Studies that have compared antihypertensive treatment in patients with diabetes versus placebo have shown reduced cardiovascular events. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), which followed patients with diabetes for an average of 8.5 years, found that patients with tight BP control (< 150/< 85 mmHg) versus less tight control (< 180/< 105 mmHg) had lower rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and peripheral vascular events. In the UKPDS, each 10-mmHg decrease in mean systolic BP was associated with a 12% reduction in risk for any complication related to diabetes, a 15% reduction for death related to diabetes, and an 11% reduction for MI. Another trial followed patients for 2 years and compared calcium-channel blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors,with or without hydrochlorothiazide against placebo and found a significant reduction in acute MI, congestive heart failure, and sudden cardiac death in the intervention group compared to placebo.

The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial has shown that patients assigned to lower BP targets have improved outcomes. In the HOT trial,patients who achieved a diastolic BP of < 80 mmHg benefited the most in terms of reduction of cardiovascular events. Other epidemiological studies have shown that BPs > 120/70 mmHg are associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes. The American Diabetes Association has recommended a target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg. Studies have shown that there is no lower threshold value for BP and that the risk of morbidity and mortality will continue to decrease well into the normal range.

Many classes of drugs have been used in numerous trials to treat patients with hypertension. All classes of drugs have been shown to be superior to placebo in terms of reducing morbidity and mortality. Often, numerous agents(three or more) are needed to achieve specific target levels of BP. Use of almost any drug therapy to reduce hypertension in patients with diabetes has been shown to be effective in decreasing cardiovascular risk. Keeping in mind that numerous agents are often required to achieve the target level of BP control, recommending specific agents becomes a not-so-simple task. The literature continues to evolve, and individual patient conditions and preferences also must come into play.

While lowering BP by any means will help to reduce cardiovascular morbidity, there is evidence that may help guide the selection of an antihypertensive regimen. The UKPDS showed no significant differences in outcomes for treatment for hypertension using an ACE inhibitor or aβ-blocker. In addition, both ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) have been shown to slow the development and progression of diabetic nephropathy. In the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE)trial, ACE inhibitors were found to have a favorable effect in reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, whereas recent trials have shown a renal protective benefit from both ACE inhibitors and ARBs. ACE inhibitors andβ-blockers seem to be better than dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers to reduce MI and heart failure. However, trials using dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in combination with ACE inhibitors andβ-blockers do not appear to show any increased morbidity or mortality in CVD, as has been implicated in the past for dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers alone. Recently, the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) in high-risk hypertensive patients,including those with diabetes, demonstrated that chlorthalidone, a thiazide-type diuretic, was superior to an ACE inhibitor, lisinopril, in preventing one or more forms of CVD.

L.N. is a typical patient with obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. Her BP control can be improved. To achieve the target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg, it may be necessary to maximize the dose of the ACE inhibitor and to add a second and perhaps even a third agent.

Diuretics have been shown to have synergistic effects with ACE inhibitors,and one could be added. Because L.N. has migraine headaches as well as diabetic nephropathy, it may be necessary to individualize her treatment. Adding a β-blocker to the ACE inhibitor will certainly help lower her BP and is associated with good evidence to reduce cardiovascular morbidity. Theβ-blocker may also help to reduce the burden caused by her migraine headaches. Because of the presence of microalbuminuria, the combination of ARBs and ACE inhibitors could also be considered to help reduce BP as well as retard the progression of diabetic nephropathy. Overall, more aggressive treatment to control L.N.'s hypertension will be necessary. Information obtained from recent trials and emerging new pharmacological agents now make it easier to achieve BP control targets.

Hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular complications of diabetes.

Clinical trials demonstrate that drug therapy versus placebo will reduce cardiovascular events when treating patients with hypertension and diabetes.

A target BP goal of < 130/80 mmHg is recommended.

Pharmacological therapy needs to be individualized to fit patients'needs.

ACE inhibitors, ARBs, diuretics, and β-blockers have all been documented to be effective pharmacological treatment.

Combinations of drugs are often necessary to achieve target levels of BP control.

ACE inhibitors and ARBs are agents best suited to retard progression of nephropathy.

Evan M. Benjamin, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of medicine and Vice President of Healthcare Quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

Email alerts

- Online ISSN 1945-4953

- Print ISSN 0891-8929

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Loading metrics

Open Access

Learning Forum

Learning Forum articles are commissioned by our educational advisors. The section provides a forum for learning about an important clinical problem that is relevant to a general medical audience.

See all article types »

A 21-Year-Old Pregnant Woman with Hypertension and Proteinuria

- Andrea Luk,

* To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: [email protected]

- Ching Wan Lam,

- Wing Hung Tam,

- Anthony W. I Lo,

- Enders K. W Ng,

- Alice P. S Kong,

- Wing Yee So,

- Chun Chung Chow

- Andrea Luk,

- Ronald C. W Ma,

- Ching Wan Lam,

- Wing Hung Tam,

- Anthony W. I Lo,

- Enders K. W Ng,

- Alice P. S Kong,

- Wing Yee So,

Published: February 24, 2009

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037

- Reader Comments

Citation: Luk A, Ma RCW, Lam CW, Tam WH, Lo AWI, Ng EKW, et al. (2009) A 21-Year-Old Pregnant Woman with Hypertension and Proteinuria. PLoS Med 6(2): e1000037. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037

Copyright: © 2009 Luk et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this article.

Competing interests: RCWM is Section Editor of the Learning Forum. The remaining authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: CT, computer tomography; I, iodine; MIBG, metaiodobenzylguanidine; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; SDHD, succinate dehydrogenase subunit D

Provenance: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Description of Case

A 21-year-old pregnant woman, gravida 2 para 1, presented with hypertension and proteinuria at 20 weeks of gestation. She had a history of pre-eclampsia in her first pregnancy one year ago. During that pregnancy, at 39 weeks of gestation, she developed high blood pressure, proteinuria, and deranged liver function. She eventually delivered by emergency caesarean section following failed induction of labour. Blood pressure returned to normal post-partum and she received no further medical follow-up. Family history was remarkable for her mother's diagnosis of hypertension in her fourth decade. Her father and five siblings, including a twin sister, were healthy. She did not smoke nor drink any alcohol. She was not taking any regular medications, health products, or herbs.

At 20 weeks of gestation, blood pressure was found to be elevated at 145/100 mmHg during a routine antenatal clinic visit. Aside from a mild headache, she reported no other symptoms. On physical examination, she was tachycardic with heart rate 100 beats per minute. Body mass index was 16.9 kg/m 2 and she had no cushingoid features. Heart sounds were normal, and there were no signs suggestive of congestive heart failure. Radial-femoral pulses were congruent, and there were no audible renal bruits.

Baseline laboratory investigations showed normal renal and liver function with normal serum urate concentration. Random glucose was 3.8 mmol/l. Complete blood count revealed microcytic anaemia with haemoglobin level 8.3 g/dl (normal range 11.5–14.3 g/dl) and a slightly raised platelet count of 446 × 10 9 /l (normal range 140–380 × 10 9 /l). Iron-deficient state was subsequently confirmed. Quantitation of urine protein indicated mild proteinuria with protein:creatinine ratio of 40.6 mg/mmol (normal range <30 mg/mmol in pregnancy).

What Were Our Differential Diagnoses?

An important cause of hypertension that occurs during pregnancy is pre-eclampsia. It is a condition unique to the gravid state and is characterised by the onset of raised blood pressure and proteinuria in late pregnancy, at or after 20 weeks of gestation [ 1 ]. Pre-eclampsia may be associated with hyperuricaemia, deranged liver function, and signs of neurologic irritability such as headaches, hyper-reflexia, and seizures. In our patient, hypertension developed at a relatively early stage of pregnancy than is customarily observed in pre-eclampsia. Although she had proteinuria, it should be remembered that this could also reflect underlying renal damage due to chronic untreated hypertension. Additionally, her electrocardiogram showed left ventricular hypertrophy, which was another indicator of chronicity.

While pre-eclampsia might still be a potential cause of hypertension in our case, the possibility of pre-existing hypertension needed to be considered. Box 1 shows the differential diagnoses of chronic hypertension, including essential hypertension, primary hyperaldosteronism related to Conn's adenoma or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing's syndrome, phaeochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, glomerulopathy, and coarctation of the aorta.

Box 1: Causes of Hypertension in Pregnancy

- Pre-eclampsia

- Essential hypertension

- Renal artery stenosis

- Glomerulopathy

- Renal parenchyma disease

- Primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn's adenoma or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia)

- Cushing's syndrome

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Coarctation of aorta

- Obstructive sleep apnoea

Renal causes of hypertension were excluded based on normal serum creatinine and a bland urinalysis. Serology for anti-nuclear antibodies was negative. Doppler ultrasonography of renal arteries showed normal flow and no evidence of stenosis. Cushing's syndrome was unlikely as she had no clinical features indicative of hypercortisolism, such as moon face, buffalo hump, violaceous striae, thin skin, proximal muscle weakness, or hyperglycaemia. Plasma potassium concentration was normal, although normokalaemia does not rule out primary hyperaldosteronism. Progesterone has anti-mineralocorticoid effects, and increased placental production of progesterone may mask hypokalaemia. Besides, measurements of renin activity and aldosterone concentration are difficult to interpret as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis is typically stimulated in pregnancy. Phaeochromocytoma is a rare cause of hypertension in pregnancy that, if unrecognised, is associated with significant maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis can be established by measuring levels of catecholamines (noradrenaline and adrenaline) and/or their metabolites (normetanephrine and metanephrine) in plasma or urine.

What Was the Diagnosis?

Catecholamine levels in 24-hour urine collections were found to be markedly raised. Urinary noradrenaline excretion was markedly elevated at 5,659 nmol, 8,225 nmol, and 9,601 nmol/day in repeated collections at 21 weeks of gestation (normal range 63–416 nmol/day). Urinary adrenaline excretion was normal. Pregnancy may induce mild elevation of catecholamine levels, but the marked elevation of urinary catecholamine observed was diagnostic of phaeochromocytoma. Conditions that are associated with false positive results, such as acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, acute cerebrovascular event, withdrawal from alcohol, withdrawal from clonidine, and cocaine abuse, were not present in our patient.

The working diagnosis was therefore phaeochromocytoma complicating pregnancy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of neck to pelvis, without gadolinium enhancement, was performed at 24 weeks of gestation. It showed a 4.2 cm solid lesion in the mid-abdominal aorto-caval region, while both adrenals were unremarkable. There were no ectopic lesions seen in the rest of the examined areas. Based on existing investigation findings, it was concluded that she had extra-adrenal paraganglioma resulting in hypertension.

What Was the Next Step in Management?

At 22 weeks of gestation, the patient was started on phenoxybenzamine titrated to a dose of 30 mg in the morning and 10 mg in the evening. Propranolol was added several days after the commencement of phenoxybenzamine. Apart from mild postural dizziness, the medical therapy was well tolerated during the remainder of the pregnancy. In the third trimester, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were maintained to below 90 mmHg and 60 mmHg, respectively. During this period, she developed mild elevation of alkaline phosphatase ranging from 91 to 188 IU/l (reference 35–85 IU/l). However, liver transaminases were normal and the patient had no seizures. Repeated urinalysis showed resolution of proteinuria. At 38 weeks of gestation, the patient proceeded to elective caesarean section because of previous caesarean section, and a live female baby weighing 3.14 kg was delivered. The delivery was uncomplicated and blood pressure remained stable.

Following the delivery, computer tomography (CT) scan of neck, abdomen, and pelvis was performed as part of pre-operative planning to better delineate the relationship of the tumour to neighbouring structures. In addition to the previously identified extra-adrenal paraganglioma in the abdomen ( Figure 1 ), the CT revealed a 9 mm hypervascular nodule at the left carotid bifurcation, suggestive of a carotid body tumour ( Figure 2 ). The patient subsequently underwent an iodine (I) 131 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan, which demonstrated marked MIBG-avidity of the paraganglioma in the mid-abdomen. The reported left carotid body tumour, however, did not demonstrate any significant uptake. This could indicate either that the MIBG scan had poor sensitivity in detecting a small tumour, or that the carotid body tumour was not functional.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g002

In June 2008, four months after the delivery, the patient had a laparotomy with removal of the abdominal paraganglioma. The operation was uncomplicated. There was no wide fluctuation of blood pressures intra- and postoperatively. Phenoxybenzamine and propranolol were stopped after the operation. Histology of the excised tumour was consistent with paraganglioma with cells staining positive for chromogranin ( Figures 3 and 4 ) and synaptophysin. Adrenal tissues were notably absent.

The tumour is a well-circumscribed fleshy yellowish mass with maximal dimension of 5.5 cm.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g003

The tumour cells are polygonal with bland nuclei. The cells are arranged in nests and are immunoreactive to chromogranin (shown here) and synaptophysin.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g004

The patient was counselled for genetic testing for hereditary phaeochromocytoma/paraganglioma. She was found to be heterozygous for c.449_453dup mutation of the succinate dehydrogenase subunit D (SDHD) gene ( Figure 5 ). This mutation is a novel frameshift mutation, and leads to SDHD deficiency (GenBank accession number: 1162563). At the latest clinic visit in August 2008, she was asymptomatic and normotensive. Measurements of catecholamine in 24-hour urine collections had normalised. Resection of the left carotid body tumour was planned for a later date. She was to be followed up indefinitely to monitor for recurrences. She was also advised to contact family members for genetic testing. Our patient gave written consent for this case to be published.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000037.g005

Phaeochromocytoma in Pregnancy

Hypertension during pregnancy is a frequently encountered obstetric complication that occurs in 6%–8% of pregnancies [ 2 ]. Phaeochromocytoma presenting for the first time in pregnancy is rare, and only several hundred cases have been reported in the English literature. In a recent review of 41 cases that presented during 1988 to 1997, maternal mortality was 4% while the rate of foetal loss was 11% [ 3 ]. Antenatal diagnosis was associated with substantial reduction in maternal mortality but had little impact on foetal mortality. Further, chronic hypertension, regardless of aetiology, increases the risk of pre-eclampsia by 10-fold [ 1 ].

Classically, patients with phaeochromocytoma present with spells of palpitation, headaches, and diaphoresis [ 4 ]. Hypertension may be sustained or sporadic, and is associated with orthostatic blood pressure drop because of hypovolaemia and impaired vasoconstricting response to posture change. During pregnancy, catecholamine surge may be triggered by pressure from the enlarging uterus and foetal movements. In the majority of cases, catecholamine-secreting tumours develop in the adrenal medulla and are termed phaeochromocytoma. Ten percent of tumours arise from extra-adrenal chromaffin tissues located in the abdomen, pelvis, or thorax to form paraganglioma that may or may not be biochemically active. The malignant potential of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma cannot be determined from histology and is inferred by finding tumours in areas of the body not known to contain chromaffin tissues. The risk of malignancy is higher in extra-adrenal tumours and in tumours that secrete dopamine.

Making the Correct Diagnosis

The diagnosis of phaeochromocytoma requires a combination of biochemical and anatomical confirmation. Catecholamines and their metabolites, metanephrines, can be easily measured in urine or plasma samples. Day collection of urinary fractionated metanephrine is considered the most sensitive in detecting phaeochromocytoma [ 5 ]. In contrast to sporadic release of catecholamine, secretion of metanephrine is continuous and is less subjective to momentary stress. Localisation of tumour can be accomplished by either CT or MRI of the abdomen [ 6 ]. Sensitivities are comparable, although MRI is preferable in pregnancy because of minimal radiation exposure. Once a tumour is identified, nuclear medicine imaging should be performed to determine its activity, as well as to search for extra-adrenal diseases. I 131 or I 123 MIBG scan is the imaging modality of choice. Metaiodobenzylguanidine structurally resembles noradrenaline and is concentrated in chromaffin cells of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma that express noradrenaline transporters. Radionucleotide imaging is contraindicated in pregnancy and should be deferred until after the delivery.

Treatment Approach

Upon confirming the diagnosis, medical therapy should be initiated promptly to block the cardiovascular effects of catecholamine release. Phenoxybenzamine is a long-acting non-selective alpha-blocker commonly used in phaeochromocytoma to control blood pressure and prevent cardiovascular complications [ 7 ]. The main side-effects of phenoxybenzamine are postural hypotension and reflex tachycardia. The latter can be circumvented by the addition of a beta-blocker. It is important to note that beta-blockers should not be used in isolation, since blockade of ß2-adrenoceptors, which have a vasodilatory effect, can cause unopposed vasoconstriction by a1-adrenoceptor stimulation and precipitate severe hypertension. There is little data on the safety of use of phenoxybenzamine in pregnancy, although its use is deemed necessary and probably life-saving in this precarious situation.

The definitive treatment of phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma is surgical excision. The timing of surgery is critical, and the decision must take into consideration risks to the foetus, technical difficulty regarding access to the tumour in the presence of a gravid uterus, and whether the patient's symptoms can be satisfactorily controlled with medical therapy [ 8 , 9 ]. It has been suggested that surgical resection is reasonable if the diagnosis is confirmed and the tumour identified before 24 weeks of gestation. Otherwise, it may be preferable to allow the pregnancy to progress under adequate alpha- and beta-blockade until foetal maturity is reached. Unprepared delivery is associated with a high risk of phaeochromocytoma crisis, characterised by labile blood pressure, tachycardia, fever, myocardial ischaemia, congestive heart failure, and intracerebral bleeding.

Patients with phaeochromocytoma or paraganglioma should be followed up for life. The rate of recurrence is estimated to be 2%–4% at five years [ 10 ]. Assessment for recurrent disease can be accomplished by periodic blood pressure monitoring and 24-hour urine catecholamine and/or metanephrine measurements.

Genetics of Phaeochromocytoma