- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.1: Basics of Differential Equations

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 10782

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Identify the order of a differential equation.

- Explain what is meant by a solution to a differential equation.

- Distinguish between the general solution and a particular solution of a differential equation.

- Identify an initial-value problem.

- Identify whether a given function is a solution to a differential equation or an initial-value problem.

Calculus is the mathematics of change, and rates of change are expressed by derivatives. Thus, one of the most common ways to use calculus is to set up an equation containing an unknown function \(y=f(x)\) and its derivative, known as a differential equation. Solving such equations often provides information about how quantities change and frequently provides insight into how and why the changes occur.

Techniques for solving differential equations can take many different forms, including direct solution, use of graphs, or computer calculations. We introduce the main ideas in this chapter and describe them in a little more detail later in the course. In this section we study what differential equations are, how to verify their solutions, some methods that are used for solving them, and some examples of common and useful equations.

General Differential Equations

Consider the equation \(y′=3x^2,\) which is an example of a differential equation because it includes a derivative. There is a relationship between the variables \(x\) and \(y:y\) is an unknown function of \(x\). Furthermore, the left-hand side of the equation is the derivative of \(y\). Therefore we can interpret this equation as follows: Start with some function \(y=f(x)\) and take its derivative. The answer must be equal to \(3x^2\). What function has a derivative that is equal to \(3x^2\)? One such function is \(y=x^3\), so this function is considered a solution to a differential equation.

Definition: differential equation

A differential equation is an equation involving an unknown function \(y=f(x)\) and one or more of its derivatives. A solution to a differential equation is a function \(y=f(x)\) that satisfies the differential equation when \(f\) and its derivatives are substituted into the equation.

Go to this website to explore more on this topic.

Some examples of differential equations and their solutions appear in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Note that a solution to a differential equation is not necessarily unique, primarily because the derivative of a constant is zero. For example, \(y=x^2+4\) is also a solution to the first differential equation in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). We will return to this idea a little bit later in this section. For now, let’s focus on what it means for a function to be a solution to a differential equation.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Verifying Solutions of Differential Equations

Verify that the function \(y=e^{−3x}+2x+3\) is a solution to the differential equation \(y′+3y=6x+11\).

To verify the solution, we first calculate \(y′\) using the chain rule for derivatives. This gives \(y′=−3e^{−3x}+2\). Next we substitute \(y\) and \(y′\) into the left-hand side of the differential equation:

\((−3e^{−2x}+2)+3(e^{−2x}+2x+3).\)

The resulting expression can be simplified by first distributing to eliminate the parentheses, giving

\(−3e^{−2x}+2+3e^{−2x}+6x+9.\)

Combining like terms leads to the expression \(6x+11\), which is equal to the right-hand side of the differential equation. This result verifies that \(y=e^{−3x}+2x+3\) is a solution of the differential equation.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Verify that \(y=2e^{3x}−2x−2\) is a solution to the differential equation \(y′−3y=6x+4.\)

First calculate \(y′\) then substitute both \(y′\) and \(y\) into the left-hand side.

It is convenient to define characteristics of differential equations that make it easier to talk about them and categorize them. The most basic characteristic of a differential equation is its order.

Definition: order of a differential equation

- The order of a differential equation is the highest order of any derivative of the unknown function that appears in the equation.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Identifying the Order of a Differential Equation

The highest derivative in the equation is \(y′\),

What is the order of each of the following differential equations?

- \(y′−4y=x^2−3x+4\)

- \(x^2y'''−3xy''+xy′−3y=\sin x\)

- \(\frac{4}{x}y^{(4)}−\frac{6}{x^2}y''+\frac{12}{x^4}y=x^3−3x^2+4x−12\)

- The highest derivative in the equation is \(y′\),so the order is \(1\).

- The highest derivative in the equation is \(y'''\), so the order is \(3\).

- The highest derivative in the equation is \(y^{(4)}\), so the order is \(4\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

What is the order of the following differential equation?

\((x^4−3x)y^{(5)}−(3x^2+1)y′+3y=\sin x\cos x\)

What is the highest derivative in the equation?

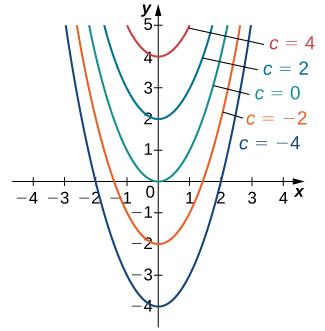

General and Particular Solutions

We already noted that the differential equation \(y′=2x\) has at least two solutions: \(y=x^2\) and \(y=x^2+4\). The only difference between these two solutions is the last term, which is a constant. What if the last term is a different constant? Will this expression still be a solution to the differential equation? In fact, any function of the form \(y=x^2+C\), where \(C\) represents any constant, is a solution as well. The reason is that the derivative of \(x^2+C\) is \(2x\), regardless of the value of \(C\). It can be shown that any solution of this differential equation must be of the form \(y=x^2+C\). This is an example of a general solution to a differential equation. A graph of some of these solutions is given in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). (Note: in this graph we used even integer values for C ranging between \(−4\) and \(4\). In fact, there is no restriction on the value of \(C\); it can be an integer or not.)

In this example, we are free to choose any solution we wish; for example, \(y=x^2−3\) is a member of the family of solutions to this differential equation. This is called a particular solution to the differential equation. A particular solution can often be uniquely identified if we are given additional information about the problem.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Finding a Particular Solution

Find the particular solution to the differential equation \(y′=2x\) passing through the point \((2,7)\).

Any function of the form \(y=x^2+C\) is a solution to this differential equation. To determine the value of \(C\), we substitute the values \(x=2\) and \(y=7\) into this equation and solve for \(C\):

\[ \begin{align*} y =x^2+C \\[4pt] 7 =2^2+C \\[4pt] =4+C \\[4pt] C =3. \end{align*}\]

Therefore the particular solution passing through the point \((2,7)\) is \(y=x^2+3\).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Find the particular solution to the differential equation

\[ y′=4x+3 \nonumber \]

passing through the point \((1,7),\) given that \(y=2x^2+3x+C\) is a general solution to the differential equation.

First substitute \(x=1\) and \(y=7\) into the equation, then solve for \(C\).

\[ y=2x^2+3x+2 \nonumber \]

Initial-Value Problems

Usually a given differential equation has an infinite number of solutions, so it is natural to ask which one we want to use. To choose one solution, more information is needed. Some specific information that can be useful is an initial value , which is an ordered pair that is used to find a particular solution.

A differential equation together with one or more initial values is called an initial-value problem . The general rule is that the number of initial values needed for an initial-value problem is equal to the order of the differential equation. For example, if we have the differential equation \(y′=2x\), then \(y(3)=7\) is an initial value, and when taken together, these equations form an initial-value problem. The differential equation \(y''−3y′+2y=4e^x\) is second order, so we need two initial values. With initial-value problems of order greater than one, the same value should be used for the independent variable. An example of initial values for this second-order equation would be \(y(0)=2\) and \(y′(0)=−1.\) These two initial values together with the differential equation form an initial-value problem. These problems are so named because often the independent variable in the unknown function is \(t\), which represents time. Thus, a value of \(t=0\) represents the beginning of the problem.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Verifying a Solution to an Initial-Value Problem

Verify that the function \(y=2e^{−2t}+e^t\) is a solution to the initial-value problem

\[ y′+2y=3e^t, \quad y(0)=3.\nonumber \]

For a function to satisfy an initial-value problem, it must satisfy both the differential equation and the initial condition. To show that \(y\) satisfies the differential equation, we start by calculating \(y′\). This gives \(y′=−4e^{−2t}+e^t\). Next we substitute both \(y\) and \(y′\) into the left-hand side of the differential equation and simplify:

\[ \begin{align*} y′+2y &=(−4e^{−2t}+e^t)+2(2e^{−2t}+e^t) \\[4pt] &=−4e^{−2t}+e^t+4e^{−2t}+2e^t =3e^t. \end{align*}\]

This is equal to the right-hand side of the differential equation, so \(y=2e^{−2t}+e^t\) solves the differential equation. Next we calculate \(y(0)\):

\[ y(0)=2e^{−2(0)}+e^0=2+1=3. \nonumber \]

This result verifies the initial value. Therefore the given function satisfies the initial-value problem.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Verify that \(y=3e^{2t}+4\sin t\) is a solution to the initial-value problem

\[ y′−2y=4\cos t−8\sin t,y(0)=3. \nonumber \]

First verify that \(y\) solves the differential equation. Then check the initial value.

In Example \(\PageIndex{4}\), the initial-value problem consisted of two parts. The first part was the differential equation \(y′+2y=3e^x\), and the second part was the initial value \(y(0)=3.\) These two equations together formed the initial-value problem.

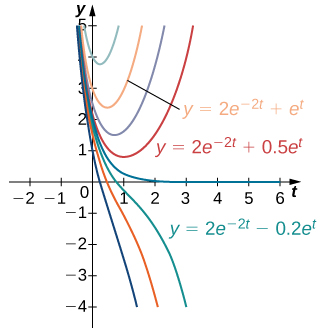

The same is true in general. An initial-value problem will consists of two parts: the differential equation and the initial condition. The differential equation has a family of solutions, and the initial condition determines the value of \(C\). The family of solutions to the differential equation in Example \(\PageIndex{4}\) is given by \(y=2e^{−2t}+Ce^t.\) This family of solutions is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), with the particular solution \(y=2e^{−2t}+e^t\) labeled.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Solving an Initial-value Problem

Solve the following initial-value problem:

\[ y′=3e^x+x^2−4,y(0)=5. \nonumber \]

The first step in solving this initial-value problem is to find a general family of solutions. To do this, we find an antiderivative of both sides of the differential equation

\[∫y′\,dx=∫(3e^x+x^2−4)\,dx, \nonumber \]

\(y+C_1=3e^x+\frac{1}{3}x^3−4x+C_2\).

We are able to integrate both sides because the y term appears by itself. Notice that there are two integration constants: \(C_1\) and \(C_2\). Solving this equation for \(y\) gives

\(y=3e^x+\frac{1}{3}x^3−4x+C_2−C_1.\)

Because \(C_1\) and \(C_2\) are both constants, \(C_2−C_1\) is also a constant. We can therefore define \(C=C_2−C_1,\) which leads to the equation

\(y=3e^x+\frac{1}{3}x^3−4x+C.\)

Next we determine the value of \(C\). To do this, we substitute \(x=0\) and \(y=5\) into this equation and solve for \(C\):

\[ \begin{align*} 5 &=3e^0+\frac{1}{3}0^3−4(0)+C \\[4pt] 5 &=3+C \\[4pt] C&=2 \end{align*}. \nonumber \]

Now we substitute the value \(C=2\) into the general equation. The solution to the initial-value problem is \(y=3e^x+\frac{1}{3}x^3−4x+2.\)

The difference between a general solution and a particular solution is that a general solution involves a family of functions, either explicitly or implicitly defined, of the independent variable. The initial value or values determine which particular solution in the family of solutions satisfies the desired conditions.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

Solve the initial-value problem

\[ y′=x^2−4x+3−6e^x,y(0)=8. \nonumber \]

First take the antiderivative of both sides of the differential equation. Then substitute \(x=0\) and \(y=8\) into the resulting equation and solve for \(C\).

\(y=\frac{1}{3}x^3−2x^2+3x−6e^x+14\)

In physics and engineering applications, we often consider the forces acting upon an object, and use this information to understand the resulting motion that may occur. For example, if we start with an object at Earth’s surface, the primary force acting upon that object is gravity. Physicists and engineers can use this information, along with Newton’s second law of motion (in equation form \(F=ma\), where \(F\) represents force, \(m\) represents mass, and \(a\) represents acceleration), to derive an equation that can be solved.

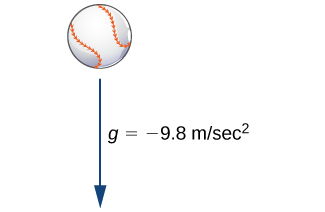

In Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) we assume that the only force acting on a baseball is the force of gravity. This assumption ignores air resistance. (The force due to air resistance is considered in a later discussion.) The acceleration due to gravity at Earth’s surface, g, is approximately \(9.8\,\text{m/s}^2\). We introduce a frame of reference, where Earth’s surface is at a height of 0 meters. Let \(v(t)\) represent the velocity of the object in meters per second. If \(v(t)>0\), the ball is rising, and if \(v(t)<0\), the ball is falling (Figure).

Our goal is to solve for the velocity \(v(t)\) at any time \(t\). To do this, we set up an initial-value problem. Suppose the mass of the ball is \(m\), where \(m\) is measured in kilograms. We use Newton’s second law, which states that the force acting on an object is equal to its mass times its acceleration \((F=ma)\). Acceleration is the derivative of velocity, so \(a(t)=v′(t)\). Therefore the force acting on the baseball is given by \(F=mv′(t)\). However, this force must be equal to the force of gravity acting on the object, which (again using Newton’s second law) is given by \(F_g=−mg\), since this force acts in a downward direction. Therefore we obtain the equation \(F=F_g\), which becomes \(mv′(t)=−mg\). Dividing both sides of the equation by \(m\) gives the equation

\[ v′(t)=−g. \nonumber \]

Notice that this differential equation remains the same regardless of the mass of the object.

We now need an initial value. Because we are solving for velocity, it makes sense in the context of the problem to assume that we know the initial velocity , or the velocity at time \(t=0.\) This is denoted by \(v(0)=v_0.\)

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): Velocity of a Moving Baseball

A baseball is thrown upward from a height of \(3\) meters above Earth’s surface with an initial velocity of \(10\) m/s, and the only force acting on it is gravity. The ball has a mass of \(0.15\) kg at Earth’s surface.

- Find the velocity \(v(t)\) of the basevall at time \(t\).

- What is its velocity after \(2\) seconds?

a. From the preceding discussion, the differential equation that applies in this situation is

\(v′(t)=−g,\)

where \(g=9.8\, \text{m/s}^2\). The initial condition is \(v(0)=v_0\), where \(v_0=10\) m/s. Therefore the initial-value problem is \(v′(t)=−9.8\,\text{m/s}^2,\,v(0)=10\) m/s.

The first step in solving this initial-value problem is to take the antiderivative of both sides of the differential equation. This gives

\[\int v′(t)\,dt=∫−9.8\,dt \nonumber \]

\(v(t)=−9.8t+C.\)

The next step is to solve for \(C\). To do this, substitute \(t=0\) and \(v(0)=10\):

\[ \begin{align*} v(t) &=−9.8t+C \\[4pt] v(0) &=−9.8(0)+C \\[4pt] 10 &=C. \end{align*}\]

Therefore \(C=10\) and the velocity function is given by \(v(t)=−9.8t+10.\)

b. To find the velocity after \(2\) seconds, substitute \(t=2\) into \(v(t)\).

\[ \begin{align*} v(t)&=−9.8t+10 \\[4pt] v(2)&=−9.8(2)+10 \\[4pt] v(2) &=−9.6\end{align*}\]

The units of velocity are meters per second. Since the answer is negative, the object is falling at a speed of \(9.6\) m/s.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

Suppose a rock falls from rest from a height of \(100\) meters and the only force acting on it is gravity. Find an equation for the velocity \(v(t)\) as a function of time, measured in meters per second.

What is the initial velocity of the rock? Use this with the differential equation in Example \(\PageIndex{6}\) to form an initial-value problem, then solve for \(v(t)\).

\(v(t)=−9.8t\)

A natural question to ask after solving this type of problem is how high the object will be above Earth’s surface at a given point in time. Let \(s(t)\) denote the height above Earth’s surface of the object, measured in meters. Because velocity is the derivative of position (in this case height), this assumption gives the equation \(s′(t)=v(t)\). An initial value is necessary; in this case the initial height of the object works well. Let the initial height be given by the equation \(s(0)=s_0\). Together these assumptions give the initial-value problem

\[ s′(t)=v(t),s(0)=s_0. \nonumber \]

If the velocity function is known, then it is possible to solve for the position function as well.

Example \(\PageIndex{7}\): Height of a Moving Baseball

A baseball is thrown upward from a height of \(3\) meters above Earth’s surface with an initial velocity of \(10m/s\), and the only force acting on it is gravity. The ball has a mass of \(0.15\) kilogram at Earth’s surface.

- Find the position \(s(t)\) of the baseball at time \(t\).

- What is its height after \(2\) seconds?

We already know the velocity function for this problem is \(v(t)=−9.8t+10\). The initial height of the baseball is \(3\) meters, so \(s_0=3\). Therefore the initial-value problem for this example is

To solve the initial-value problem, we first find the antiderivatives:

\[∫s′(t)\,dt=∫(−9.8t+10)\,dt \nonumber \]

\(s(t)=−4.9t^2+10t+C.\)

Next we substitute \(t=0\) and solve for \(C\):

\(s(t)=−4.9t^2+10t+C\)

\(s(0)=−4.9(0)^2+10(0)+C\)

Therefore the position function is \(s(t)=−4.9t^2+10t+3.\)

b. The height of the baseball after \(2\) sec is given by \(s(2):\)

\(s(2)=−4.9(2)^2+10(2)+3=−4.9(4)+23=3.4.\)

Therefore the baseball is \(3.4\) meters above Earth’s surface after \(2\) seconds. It is worth noting that the mass of the ball cancelled out completely in the process of solving the problem.

Key Concepts

- A differential equation is an equation involving a function \(y=f(x)\) and one or more of its derivatives. A solution is a function \(y=f(x)\) that satisfies the differential equation when \(f\) and its derivatives are substituted into the equation.

- A differential equation coupled with an initial value is called an initial-value problem. To solve an initial-value problem, first find the general solution to the differential equation, then determine the value of the constant. Initial-value problems have many applications in science and engineering.

COMMENTS

SAMPLE APPLICATION OF DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS 3 Sometimes in attempting to solve a de, we might perform an irreversible step. This might introduce extra solutions. If we can get a short list which ... Example 2.2. Solve the ivp sin(x)dx+ydy = 0, where y(0) = 1. ∗ ...

Ordinary Differential Equations Igor Yanovsky, 2005 7 2LinearSystems 2.1 Existence and Uniqueness A(t),g(t) continuous, then can solve y = A(t)y +g(t) (2.1) y(t 0)=y 0 For uniqueness, need RHS to satisfy Lipshitz condition. 2.2 Fundamental Matrix A matrix whose columns are solutions of y = A(t)y is called a solution matrix.

A few examples are Newton's and La-grange equations for classical mechanics, Maxwell's equations for classical electromagnetism, Schr odinger's equation for quantum mechanics, and Einstein's equation for the general the-ory of gravitation. In the following examples we show how di erential equations look like.

An example of a linear equation is xy9 1 y − 2x because, for x ± 0, it can be written in the form y9 1 1 x y − 2 Notice that this differential equation is not separable because it's impossible to factor the expression for y9 as a function of x times a function of y. But we can still solve the equa tion by noticing, by the Product Rule, that

Another example Solve the initial value problem y0 = cos(t) and y(0) = 1. 6. Solution If f0(t) = cos(t), then, by definition, f(t) is an antiderivative of cos(t). We know ... For example, all solutions to the equation y0 = 0 are constant. There are nontrivial differential equations which have some constant solutions. 8.

To solve the linear differential equation , multiply both sides by the integrating factor and integrate both sides. EXAMPLE 1 Solve the differential equation . SOLUTION The given equation is linear since it has the form of Equation 1 with and . An integrating factor is Multiplying both sides of the differential equation by , we get or

182 Chapter 10. Differential Equations (LECTURE NOTES 10) 10.3 Euler's Method Difficult-to-solve differential equations can always be approximated by numerical methods. We look at one numerical method called Euler's Method. Euler's method uses the readily available slope information to start from the point (x0,y0) then move

An important technique for solving differential equations is to guess the functional form of a solution (called an ansatz, or trial answer), substitute it in, and then see if the free parameters can be adjusted to make the solution work. Because the solution of a differential equation is unique as long as the functions de ning it are reasonably ...

differential equation (1) and the initial condition (2). The uniqueness of the solution follows from the Lipschitz condition. Picard's Theorem has a natural extension to an initial value problem for a system of mdifferential equations of the form y′ = f(x,y) , y(x0) = y0, (5) where y0 ∈ Rm and f : [x0,XM] × Rm → Rm. On introducing ...

For example ode23 compares a second order method with a third order method to estimate the step size, while ode45 compares a fourth order method with a fifth order method. The letter "s" in the name of some of the ode functions indicates a stiff solver. These methods solve a matrix equation at each step, so they do more work per step

Euler's method is a numerical technique to solve ordinary differential equations of the form dy = f ( x , y ) , y ( 0 ) = y dx. 0. (1) So only first order ordinary differential equations can be solved by using Euler's method. In another chapter we will discuss how Euler's method is used to solve higher order ordinary differential ...

Definition: differential equation. A differential equation is an equation involving an unknown function y = f(x) and one or more of its derivatives. A solution to a differential equation is a function y = f(x) that satisfies the differential equation when f and its derivatives are substituted into the equation.

as it is for the equation (1.1). For example, consider the differential equation (1.2) x0 = x. This equation is fundamentally different from (1.1) because the unknown function xappears on the right hand side. This equation cannot be solved by an anti-differentiation of the right hand side, because the right hand side is not a known function ...

2 CHAPTER 1. FIRST-ORDER SINGLE DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS (ii)how to solve the corresponding differential equations, (iii)how to interpret the solutions, and (iv)how to develop general theory. 1.2 Relaxation and Equilibria The most simplest and important example which can be modeled by ODE is a relaxation process.

equation (1), and its integral curves give a picture of the solutions to (1). Two integral curves (in solid lines) have been drawn for the equation y′ = x− y. In general, by sketching in a few integral curves, one can often get some feeling for the behavior of the solutions. The problems will illustrate. Even when the equation can be solved ...

equation in Example 1. EXAMPLE 1 Use power series to solve the equation . SOLUTION We assume there is a solution of the form We can differentiate power series term by term, so In order to compare the expressions for and more easily, we rewrite as follows: Substituting the expressions in Equations 2 and 4 into the differential equation, we obtain or

Page | 5 where and are functions of alone or constant, is called Bernoulli's equation. Dividing both sides of Ⓑ by , we get .

dt equation; this means that we must take thez values into account even to find the projected characteristic curves in the xy-plane. In particular, this allows for the possibility that the projected characteristics may cross each other. The condition for solving fors and t in terms ofx and y requires that the Jacobian matrix be nonsingular: J ...

EXAMPLE 1 Unique Solution of an IVP The initial-value problem 3y 5y y 7y 0, y(1) 0, y (1) 0, y (1) 0 ... Boundary-Value Problem Another type of problem consists of solving a linear differential equation of order two or greater in which the dependent variable y or its derivatives are specified at different points. A problem such as Solve: a 21x2 ...

xs y′ differential equation using separation: = where. y′ with y2 dx: cos (x) on one side and dx = y2. Step 3: Integrate both sides of. Step 4: Solve for. y: all on the other side: y2dy = cos (x)dx the equation: 3 1 y3 = sin(x) + C. When C is multiplied by 3, it is still a constant, 3.

The finite difference method is used to solve ordinary differential equations that have conditions imposed on the boundary rather than at the initial point. These problems are called boundary-value problems. In this chapter, we solve second-order ordinary differential equations of the form. y.

q(y) y0 = p(x) (1) where q(y) = 1/h(y). Of course, in dividing the equation by h(y) we have to assume that h(y) 6= 0. Any numbers r such that h(r) = 0 may result in singular solutions of the form y(x) ≡ r. If we write y0 as dy/dx and interpret this symbol as "differential y" divided by "differential x," then a separable equation can ...

The general form of a Bernoulli equation is. dy. + P(x)y = Q(x) yn , dx where P and Q are functions of x, and n is a constant. Show that the transformation to a new dependent variable z = y1−n reduces the equation to one that is linear in z (and hence solvable using the integrating factor method). Solve the following Bernoulli differential ...