VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Jun 23, 2023

How to Write a Novel: 13-Steps From a Bestselling Writer [+Templates]

This post is written by author, editor, and ghostwriter Tom Bromley. He is the instructor of Reedsy's 101-day course, How to Write a Novel .

Writing a novel is an exhilarating and daunting process. How do you go about transforming a simple idea into a powerful narrative that grips readers from start to finish? Crafting a long-form narrative can be challenging, and it requires skillfully weaving together various story elements.

In this article, we will break down the major steps of novel writing into manageable pieces, organized into three categories — before, during, and after you write your manuscript.

How to write a novel in 13 steps:

1. Pick a story idea with novel potential

2. develop your main characters, 3. establish a central conflict and stakes, 4. write a logline or synopsis, 5. structure your plot, 6. pick a point of view, 7. choose a setting that benefits your story , 8. establish a writing routine, 9. shut out your inner editor, 10. revise and rewrite your first draft, 11. share it with your first readers, 12. professionally edit your manuscript, 13. publish your novel.

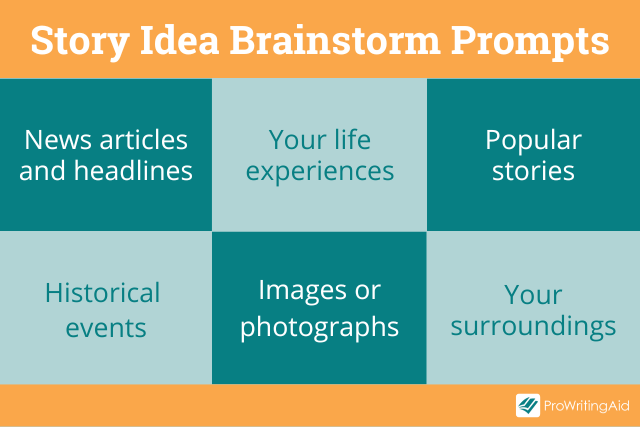

Every story starts with an idea.

You might be lucky, like JRR Tolkien, who was marking exam papers when a thought popped into his head: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’ You might be like Jennifer Egan, who saw a wallet left in a public bathroom and imagined the repercussions of a character stealing it, which set the Pulitzer prize-winner A Visit From the Goon Squad in process. Or you might follow Khaled Hosseini, whose The Kite Runner was sparked by watching a news report on TV.

Many novelists I know keep a notebook of ideas both large and small 一 sometimes the idea they pick up on they’ll have had much earlier, but whatever reason, now feels the time to write it. Certainly, the more ideas you have, the more options you’ll have to write.

✍️ Need a little inspiration? Check our list of 30+ story ideas for fiction writing , our list of 300+ writing prompts , or even our plot generator .

Is your idea novel-worthy?

How do you know if what you’ve got is the inspiration for a novel, rather than a short story or a novella ? There’s no definitive answer here, but there are two things to look out for

Firstly, a novel allows you the space to show how a character changes over time, whereas a short story is often more about a vignette or an individual moment. Secondly, if an idea is fit for a novel, it’ll nag away at you: a thread asking to be pulled to see where it goes. If you find yourself coming back to an idea, then that’s probably one to explore.

I expand on how to cultivate and nurture your ‘idea seeds’ in my free 10-day course on novel writing.

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Author and ghostwriter Tom Bromley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

Another starting point (or essential element) for writing a novel will come in the form of the people who will populate your stories: the protagonists.

My rule of thumb in writing is that a reader will read on for one of two reasons: either they care about the characters , or they want to know what happens next (or, in an ideal world, both). Now different people will tell you that character or plot are the most important element when writing.

In truth, it’s a bit more complicated than that: in a good novel, the main character or protagonist should shape the plot, and the plot should shape the protagonist. So you need both core elements in there, and those two core elements are entwined rather than being separate entities.

Characters matter because when written well, readers become invested in what happens to them. You can develop the most brilliant, twisty narrative, but if the reader doesn’t care how the protagonist ends up, you’re in trouble as a writer.

As we said above, one of the strengths of the novel is that it gives you the space to show how characters change over time. How do characters change?

Firstly, they do so by being put in a position where they have to make decisions, difficult decisions, and difficult decisions with consequences . That’s how we find out who they really are.

Secondly, they need to start from somewhere where they need to change: give them flaws, vulnerabilities, and foibles for them to overcome. This is what makes them human — and the reason why readers respond to and care about them.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

🗿 Need more guidance? Look into your character’s past using these character development exercises , or give your character the perfect name using this character name generator .

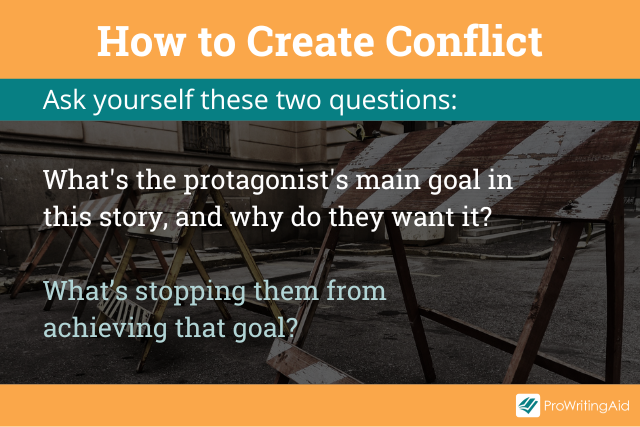

As said earlier, it’s important to have both a great character and an interesting plot, which you can develop by making your character face some adversities.

That drama in the novel is usually built around some sort of central conflict . This conflict creates a dramatic tension that compels the reader to read on. They want to see the outcome of that conflict resolved: the ultimate resolution of the conflict (hopefully) creates a satisfying ending to the narrative.

A character changes, as we said above, when they are put in a position of making decisions with consequences. Those consequences are important. It isn’t enough for a character to have a goal or a dream or something they need to achieve (to slay the dragon): there also needs to be consequences if they don’t get what they’re after (the dragon burns their house down). Upping the stakes heightens the drama all round.

Now you have enough ingredients to start writing your novel, but before you do that, it can be useful to tighten them all up into a synopsis.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

So far you’ve got your story idea, your central characters and your sense of conflict and stakes. Now is the time to distill this down into a narrative. Different writers approach this planning stage in different ways, as we’ll come to in a moment, but for anyone starting a novel, having a clear sense of what is at the heart of your story is crucial.

There are a lot of different terms used here 一 pitch, elevator pitch , logline, shoutline, or the hook of your synopsis 一 but whatever the terminology the idea remains the same. This is to summarize your story in as few words as possible: a couple of dozen words, say, or perhaps a single sentence.

This exercise will force you to think about what your novel is fundamentally about. What is the conflict at the core of the story? What are the challenges facing your main protagonist? What do they have at stake?

📚 Check out these 48 irresistible book hook examples and get inspired to craft your own.

If you need some help, as you go through the steps in this guide, you can fill in this template:

My story is a [genre] novel. It’s told from [perspective] and is set in [place and time period] . It follows [protagonist] , who wants [goal] because [motivation] . But [conflict] doesn’t make that easy, putting [stake] at risk.

It's not an easy thing to do, to write this summarising sentence or two. In fact, they might be the most difficult sentences to get down in the whole writing process. But it is really useful in helping you to clarify what your book is about before you begin. When you’re stuck in the middle of the writing, it will be there for you to refer back to. And further down the line, when you’ve finished the novel, it will prove invaluable in pitching to agents , publishers, and readers.

📼 Learn more about the process of writing a logline from professional editor Jeff Lyons.

Another particularly important step to prepare for the writing part, is to outline your plot into different key story points.

There’s no right answer here as to how much planning you should do before you write: it very much depends on the sort of writer you are. Some writers find planning out their novel before start gives them confidence and reassurance knowing where their book is going to go. But others find this level of detail restrictive: they’re driven more by the freedom of discovering where the writing might take them.

This is sometimes described as a debate between ‘planners’ and ‘pantsers’ (those who fly by the seat of their pants). In reality, most writers sit somewhere on a sliding scale between the two extremes. Find your sweet spot and go from there!

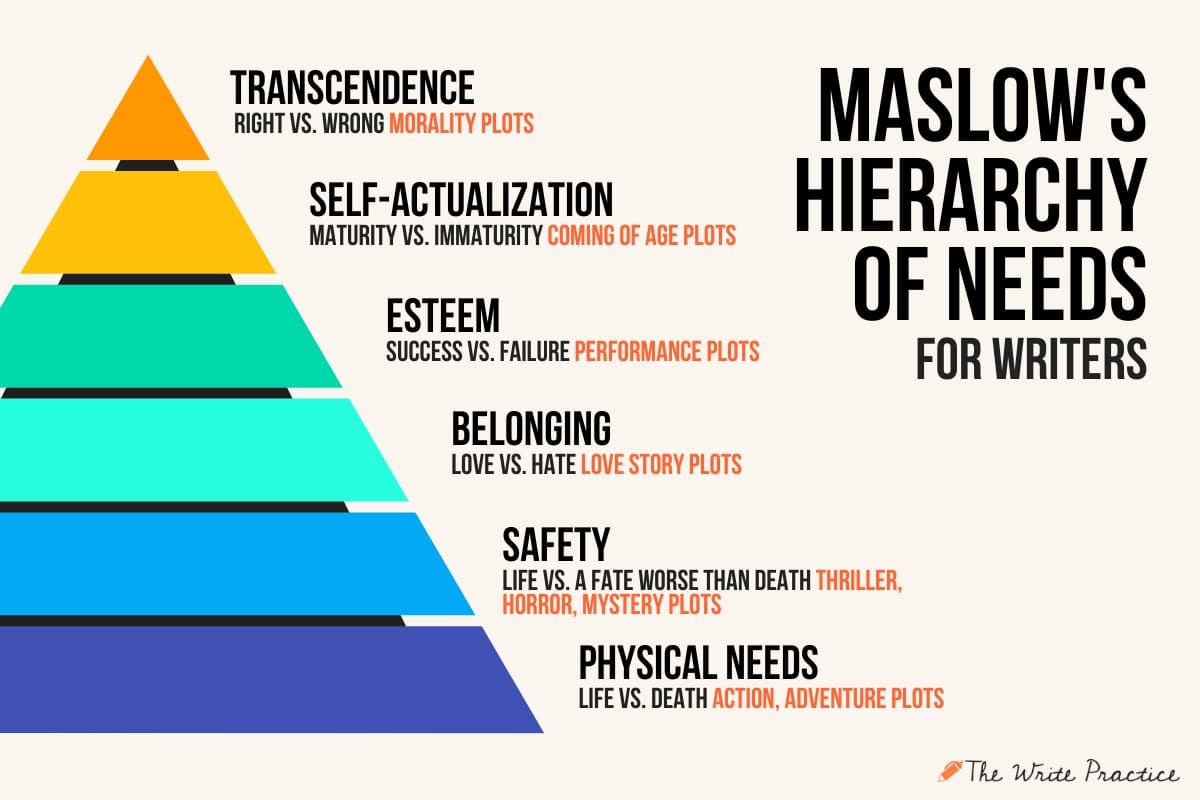

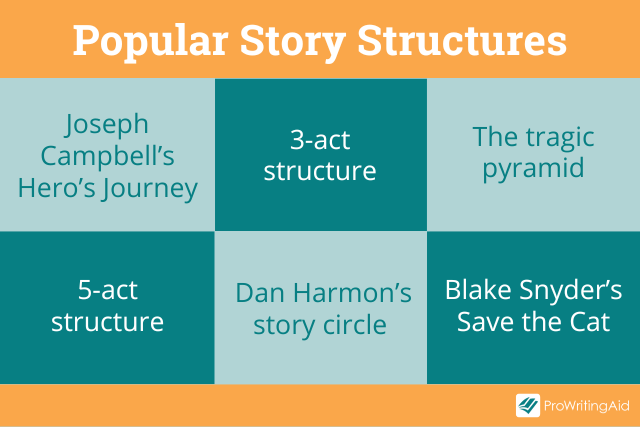

If you’re a planning type, there’s plenty of established story structures out there to build your story around. Popular theories include the Save the Cat model and Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey . Then there are books such as Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots , which suggests that all stories are one of, well, you can probably work that out.

Whatever the structure, most stories follow the underlying principle of having a beginning, middle and end (and one that usually results in a process of change). So even if you’re ‘pantsing’ rather than planning, it’s helpful to know your direction of travel, though you might not yet know how your story is going to get there.

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

Finally, remember what we said earlier about plot and character being entwined: your character’s journey shouldn’t be separate to what happens in the story. Indeed, sometimes it can be helpful to work out the character’s journey of change first, and shape the plot around that, rather than the other way round.

Now, let’s consider which perspective you’re going to write your story from.

However much plotting you decide to do before you start writing, there are two further elements to think about before you start putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard). The first one is to think about which point of view you’re going to tell your story from. It is worth thinking about this before you start writing because deciding to change midway through your story is a horribly thankless task (I speak from bitter personal experience!)

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

Although there might seem a large number of viewpoints you could tell your story from, in reality, most fiction is told from two points of view 一 first person (the ‘I’ form) and third person ‘close’ (he/she/they). ‘Close’ third person is when the story is witnessed from one character’s view at a time (as opposed to third person ‘omniscient’ where the story can drop into lots of people’s thoughts).

Both of these viewpoints have advantages and disadvantages. First person is usually better for intimacy and getting into character’s thoughts: the flip side is that its voice can feel a bit claustrophobic and restrictive in the storytelling. Third person close offers you more options and more space to tell your story: but can feel less intimate as a result.

There’s no right and wrong here in terms of which is the ‘best’ viewpoint. It depends on the particular demands of the story that you are wanting to write. And it also depends on what you most feel comfortable writing in. It can be a useful exercise to write a short section in both viewpoints to see which feels the best fit for you before starting to write.

Which POV is right for your book?

Take our quiz to find out! Takes only 1 minute.

Besides choosing a point of view, consider the setting you’re going to place your story in.

The final element to consider before beginning your story is to think about where your story is going to be located . Settings play a surprisingly important part in bringing a story to life. When done well, they add in mood and atmosphere, and can act almost like an additional character in your novel.

There are many questions to consider here. And again, it depends a bit on the demands of the story that you are writing.

Is your setting going to a real place, a fictional one, or a real place with fictional elements? Is it going to be set in the present day, the past, or at an unspecified time? Are you going to set your story in somewhere you know, or need to research to capture properly? Finally, is your setting suited to the story you are telling, and serve to accentuate it, rather than just acting as a backdrop?

If you’re writing a novel in genres such as fantasy or science fiction , then you may well need to go into some additional world-building as well before you start writing. Here, you may have to consider everything from the rules and mores of society to the existence of magical powers, fantastic beasts, extraterrestrials, and futuristic technology. All of these can have a bearing on the story, so it is better to have a clear setup in your head before you start to write.

The Ultimate Worldbuilding Template

130 questions to help create a world readers want to visit again and again.

Whether your story is set in central London or the outer rings of the solar system, some elements of the descriptive detail remain the same. Think about the use of all the different senses — the sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures of where you’re writing about. Those sorts of small details can help to bring any setting to life, from the familiar to the imaginary.

Alright, enough brainstorming and planning. It’s time to let the words flow on the page.

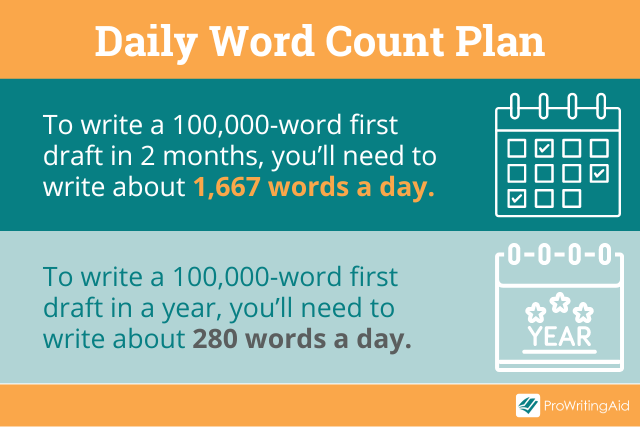

Having done your prep — or as much prep and planning as you feel you need — it’s time to get down to business and write the thing. Getting a full draft of a novel is no easy task, but you can help yourself by setting out some goals before you start writing.

Firstly, think about how you write best. Are you a morning person or an evening person? Would you write better at home or out and about, in a café or a library, say? Do you need silence to write, or musical encouragement to get the juices flowing? Are you a regular writer, chipping away at the novel day by day, or more of a weekend splurger?

How to Build a Solid Writing Routine

In 10 days, learn to change your habits to support your writing.

I’d always be wary of anyone who tells you how you should be writing. Find a routine and a setup that works for you . That might not always be the obvious one: the crime writer Jo Nesbø spent a while creating the perfect writing room but discovered he couldn’t write there and ended up in the café around the corner.

You might not keep the same way of writing throughout the novel: routines can help, but they can also become monotonous. You may need to find a way to shake things up to keep going.

Deadlines help here. If you’re writing a 75,000-word novel, then working at a pace of 5,000 words a week will take you 15 weeks (Monday to Friday, that’s 1000 words a day). Half the pace will take twice as long. Set yourself a realistic deadline to finish the book (and key points along the way). Without a deadline, the writing can end up drifting, but it needs to be realistic to avoid giving yourself a hard time.

In my experience, writing speeds vary. I tend to start quite slowly on a book, and speed up towards the end. There are times when the tap is open, and the words are pouring out: make the most of those moments. There are times, too, when each extra sentence feels like torture: don’t beat yourself up here. Be kind to yourself: it’s a big, demanding project you’re undertaking.

Speaking of self-compassion, a word on that harsh editor inside your mind…

The other important piece of advice is to continue writing forward. It is very easy, and very tempting, to go back over what you’ve written and give it a quick edit. Once you start down that slippery slope, you end up rewriting and reworking the same scene and never get any further forwards in the text. I know of writers who spent months perfecting their first chapter before writing on, only to delete that beginning as the demands of the story changed.

The first draft of your novel isn’t about perfection; it’s about getting the words down. One writer I work with calls it the ‘vomit draft’ — getting everything out and onto the page. It’s only once you’ve got a full manuscript down that you can see your ideas in context and have the capacity to edit everything properly. So as much as your inner editor might be calling you, resist! They’ll have their moment in the sun later on. For now, it’s about getting a complete version down, that you can go on to work with and shape.

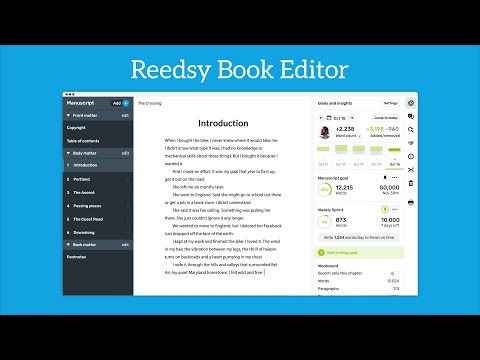

By now, you’ve reached the end of your first draft (we might be glossing over the hard writing part just a little here: if you want more detail and help on how to get through to the end of your draft, our How to Write A Novel course is warmly recommended).

NEW REEDSY COURSE

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

Reaching the end of your first draft is an important milestone in the journey of a book. Sadly for those who feel that this is the end of the story, it’s actually more of a stepping stone than the finish line.

In some ways, now the hard work begins. The difference between wannabe writers and those who get published can often be found in the amount of rewriting done. Professional writers will go back and back over what they’ve written, honing what they’ve created until the text is as tight and taut as it is possible to be.

How do you go about achieving this? The first thing to do upon finishing is to put the manuscript in a drawer. Leave it for a month or six weeks before you come back to it. That way, you’ll return the script with a fresh pair of eyes. Read it back through and be honest about what works and what doesn’t. As you read the script, think in particular about pace: are there sections in the novel that are too fast or too slow? Avoid the trap of the saggy middle . Then consider: is your character arc complete and coherent? Look at the big-picture stuff first before you tackle the smaller details.

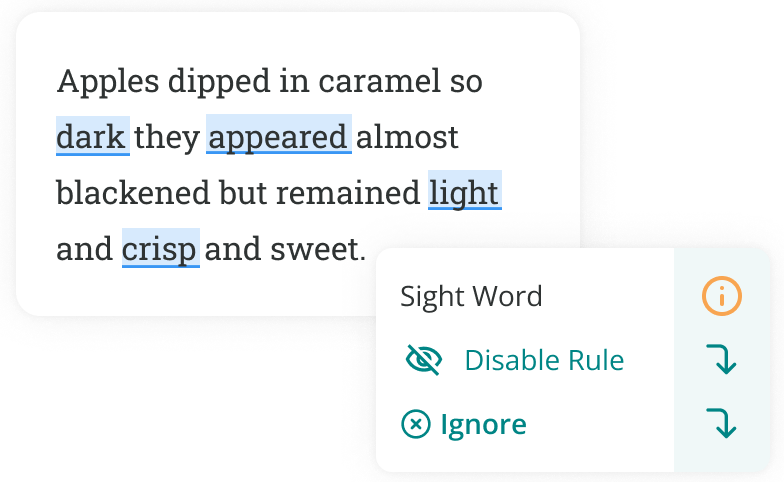

Edit your novel closely

On that note, here are a few things you might want to keep an eye out for:

Show, don’t tell. Sometimes, you just need to state something matter-of-factly in your novel, that’s fine. But, as much as you can, try to illustrate a point instead of just stating it . Keep in mind the words of Anton Chekhov: “Don’t tell me the moon is shining. Show me the glint of light on broken glass."

“Said” is your friend. When it comes to dialogue, there can be the temptation to spice things up a bit by using tags like “exclaimed,” “asserted,” or “remarked.” And while there might be a time and place for these, 90% of the time, “said” is the best tag to use. Anything else can feel distracting or forced.

Stay away from purple prose. Purple prose is overly embellished language that doesn’t add much to the story. It convolutes the intended message and can be a real turn-off for readers.

Get our Book Editing Checklist

Resolve every error, from plot holes to misplaced punctuation.

Once you feel it’s good enough for other people to lay their eyes on it, it’s time to ask for feedback.

Writing a novel is a two-way process: there’s you, the writer, and there’s the intended audience, the reader. The only way that you can find out if what you’ve written is successful is to ask people to read and get feedback.

Think about when to ask for feedback and who to ask it from. There are moments in the writing when feedback is useful and others where it gets in the way. To save time, I often ask for feedback in those six weeks when the script is in the drawer (though I don’t look at those comments until I’ve read back myself first). The best people to ask for feedback are fellow writers and beta readers : they know what you’re going through and will also be most likely to offer you constructive feedback.

Also, consider working with sensitivity readers if you are writing about a place or culture outside your own. Friends and family can also be useful but are a riskier proposition: they might be really helpful, but equally, they might just tell you it’s great or terrible, neither of which is overly useful.

Feedbacking works best when you can find at least a few people to read, and you can pool their comments. My rule is that if more than one person is saying the same thing, they are probably right. If only one person is saying something, then you have a judgment call to make as to whether to take those comments further (though usually, you’ll know in your gut whether they are right or not.)

Overall, the best feedback you can receive is that of a professional editor…

Once you’ve completed your rewrites and taken in comments from your chosen feedbackers, it’s time to take a deep breath and seek outside opinions. What happens next here depends on which route you want to take to market:

If you want to go down the traditional publishing route , you’ll probably need to get a literary agent, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

If you’re going down the self-publishing route , you’ll need to do what would be done in a traditional publishing house and take your book through the editing process. This normally happens in three stages.

Developmental editing. The first of these is to work with a development editor , who will read and critique your work primarily from a structural point of view.

Copy-editing. Secondly, the book must be copy-edited , where an editor works more closely, line-by-line, on the script.

Proofreading. Finally, usually once the script has been typeset, then the material should be professionally proofread , to spot any final mistakes or orrors. Sorry, errors!

Finding such people can sound like a daunting task. But fear not! Here at Reedsy, we have a fantastic fleet of editors of all shapes, sizes, and experiences. So whatever your needs or requirements, we should be able to pair you with an editor to suit.

MEET EDITORS

Polish your book with expert help

Sign up, meet 1500+ experienced editors, and find your perfect match.

Now that you’ve ironed out all the wrinkles of your manuscript, it’s time to release it into the wild.

For those thinking about going the traditional publishing route , now’s the time for you to get to work. Most trade publishers will only accept work from a literary agent, so you’ll need to find a suitable literary agent to represent your work.

The querying process is not always straightforward: it involves research, waiting and often a lot of rejections until you find the right person (I was rejected by 24 agents before I found my first agent). Usually, an agent will ask to see a synopsis and the first three chapters (check their websites for submission details). If they like what they read, they’ll ask to see the whole thing.

If you’re self-publishing, you’ll need to think about getting your finished manuscript to market. You’ll need to get it typeset (laid out in book form) and find a cover designer . Do you want to sell printed copies or just ebooks? You’ll need to work out how to work Amazon , where a lot of your sales will come from, and also how you’ll market your book .

For those picked up by a traditional publisher, all the editing steps discussed will take place in-house. That might sound like a smoother process, but the flip side can be less control over the process: a publisher may have the final say in the cover or the title, and lead times (when the book is published) are usually much longer. So it’s worth thinking about which route to market works best for you.

Finally, you’re a published author! Congratulations. Now all you have to do is think about writing the next one…

As an editor and publisher, Tom has worked on several hundred titles, again including many prize-winners and international bestsellers.

8 responses

Sasha Winslow says:

14/05/2019 – 02:56

I started writing in February 2019. It was random, but there was an urge to the story I wanted to write. At first, I was all over the place. I knew the genre I wanted to write was Fantasy ( YA or Adult). That has been my only solid starting point the genre. From February to now, I've changed my story so many times, but I am happy to say by giving my characters names I kept them. I write this all to say is thank you for this comprehensive step by step. Definitely see where my issues are and ways to fix it. Thank you, thank you, thank you!

Evelyn P. Norris says:

30/10/2019 – 14:18

My number one tip is to write in order. If you have a good idea for a future scene, write down the idea for the scene, but do NOT write it ahead of time. That's a major cause of writer's block that I discovered. Write sequentially. :) If you can't help yourself, make sure you at least write it in a different document, and just ignore that scene until you actually get to that part of the novel

Allen P. Wilkinson says:

28/01/2020 – 04:51

How can we take your advice seriously when you don’t even know the difference between stationary and stationery? Makes me wonder how competent your copy editors are.

↪️ Martin Cavannagh replied:

29/01/2020 – 15:37

Thanks for spotting the typo!

↪️ Chris Waite replied:

14/02/2020 – 13:17

IF you're referring to their use of 'stationery' under the section '1. Nail down the story idea' (it's the only reference on this page) then the fact that YOU don't know the difference between stationery and stationary and then bother to tell the author of this brilliant blog how useless they must be when it's YOU that is the thicko tells me everything I need to know about you and your use of a middle initial. Bellend springs to mind.

Sapei shimrah says:

18/03/2020 – 13:59

Thanks i will start writing now

Jeremy says:

25/03/2020 – 22:41

I’ve run the gamut between plotter and pantser, but lately I’ve settled on in-depth plotting before my novels. It’s hard for me to do focus wise, but I’m finding I’m spending less time in writer’s block. What trips me up more is finding the right voice for my characters. I’m currently working on a sci-fi YA novel and using the Save the Cat beat sheet for structure for the first time. Thank you for the article!

Nick Girdwood says:

29/04/2020 – 10:32

Can you not write a story without some huge theme?

Comments are currently closed.

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

What is Tone in Literature? Definition & Examples

We show you, with supporting examples, how tone in literature influences readers' emotions and perceptions of a text.

Writing Cozy Mysteries: 7 Essential Tips & Tropes

We show you how to write a compelling cozy mystery with advice from published authors and supporting examples from literature.

Man vs Nature: The Most Compelling Conflict in Writing

What is man vs nature? Learn all about this timeless conflict with examples of man vs nature in books, television, and film.

The Redemption Arc: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

Learn what it takes to redeem a character with these examples and writing tips.

How Many Sentences Are in a Paragraph?

From fiction to nonfiction works, the length of a paragraph varies depending on its purpose. Here's everything you need to know.

Narrative Structure: Definition, Examples, and Writing Tips

What's the difference between story structure and narrative structure? And how do you choose the right narrative structure for you novel?

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Try our novel writing master class — 100% free

Sign up for a free video lesson and learn how to make readers care about your main character.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Whether you’ve been struck with a moment of inspiration or you’ve carried a story inside you for years, you’re here because you want to start writing fiction. From developing flesh-and-bone characters to worlds as real as our own, good fiction is hard to write, and getting the first words onto the blank page can be daunting.

Daunting, but not impossible. Although writing good fiction takes time, with a few fiction writing tips and your first sentences written, you’ll find that it’s much easier to get your words on the page.

Let’s break down fiction to its essential elements. We’ll investigate the individual components of fiction writing—and how, when they sit down to write, writers turn words into worlds. Then, we’ll turn to instructor Jack Smith and his thoughts on combining these elements into great works of fiction. But first, what are the elements of fiction writing?

Introduction to Fiction Writing: The Six Elements of Fiction

Before we delve into any writing tips, let’s review the essentials of creative writing in fiction. Whether you’re writing flash fiction , short stories, or epic trilogies, most fiction stories require these six components:

- Plot: the “what happens” of your story.

- Characters: whose lives are we watching?

- Setting: the world that the story is set in.

- Point of View: from whose eyes do we see the story unfold?

- Theme: the “deeper meaning” of the story, or what the story represents.

- Style: how you use words to tell the story.

It’s important to recognize that all of these elements are intertwined. You can’t build the setting without writing it through a certain point of view; you can’t develop important themes with arbitrary characters, etc. We’ll get into the relationship between these elements later, but for now, let’s explore how to use each element to write fiction.

1. Fiction Writing Tip: Developing Fictional Plots

Plot is the series of causes and effects that produce the story as a whole. Because A, then B, then C—ultimately leading to the story’s climax , the result of all the story’s events and character’s decisions.

If you don’t know where to start your story, but you have a few story ideas, then start with the conflict . Some novels take their time to introduce characters or explain the world of the piece, but if the conflict that drives the story doesn’t show up within the first 15 pages, then the story loses direction quickly.

That’s not to say you have to be explicit about the conflict. In Harry Potter, Voldemort isn’t introduced as the main antagonist until later in the first book; the series’ conflict begins with the Dursley family hiding Harry from his magical talents. Let the conflict unfold naturally in the story, but start with the story’s impetus, then go from there.

2. Fiction Writing Tip: Creating Characters

Think far back to 9th grade English, and you might remember the basic types of story conflicts: man vs. nature, man vs. man, and man vs. self. The conflicts that occur within stories happen to its characters—there can be no story without its people. Sometimes, your story needs to start there: in the middle of a conversation, a disrupted routine, or simply with what makes your characters special.

There are many ways to craft characters with depth and complexity. These include writing backstory, giving characters goals and fatal flaws, and making your characters contend with complicated themes and ideas. This guide on character development will help you sort out the traits your characters need, and how to interweave those traits into the story.

3. Fiction Writing Tip: Give Life to Living Worlds

Whether your story is set on Earth or a land far, far away, your setting lives in the same way your characters do. In the same way that we read to get inside the heads of other people, we also read to escape to a world outside of our own. Consider starting the story with what makes your world live: a pulsing city, the whispered susurrus of orchards, hills that roil with unsolved mysteries, etc. Tell us where the conflict is happening, and the story will follow.

4. Fiction Writing Tip: Play With Narrative Point of View

Point of view refers to the “cameraman” of the story—the vantage point we are viewing the story through. Maybe you’re stuck starting your story because you’re trying to write it in the wrong person. There are four POVs that authors work with:

- First person—the story is told from the “I” perspective, and that “I” is the protagonist.

- First person peripheral—the story is told from the “I” perspective, but the “I” is not the protagonist, but someone adjacent to the protagonist. (Think: Nick Carraway, narrator of The Great Gatsby. )

- Second person—the story is told from the “you” perspective. This point of view is rare, but when done effectively, it can create a sense of eeriness or a personalized piece.

- Third person limited—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator usually writes from the perspective of one or two characters.

- Third person omniscient—the story is told from the “he/she/they” perspective. The narrator is not directly involved in the lives of the characters; additionally, the narrator knows what is happening in each character’s heads and in the world at large.

If you can’t find the right words to begin your piece, consider switching up the pronouns you use and the perspective you write from. You might find that the story flows onto the page from a different point of view.

5. Fiction Writing Tip: Use the Story to Investigate Themes

Generally, the themes of the story aren’t explored until after the aforementioned elements are established, and writers don’t always know the themes of their own work until after the work is written. Still, it might help to consider the broader implications of the story you want to write. How does the conflict or story extend into a bigger picture?

Let’s revisit Harry Potter’s opening scenes. When we revisit the Dursleys preventing Harry from knowing about his true nature, several themes are established: the meaning of family, the importance of identity, and the idea of fate can all be explored here. Themes often develop organically, but it doesn’t hurt to consider the message of your story from the start.

6. Fiction Writing Tip: Experiment With Words

Style is the last of the six fiction elements, but certainly as important as the others. The words you use to tell your story, the way you structure your sentences, how you alternate between characters, and the sounds of the words you use all contribute to the mood of the work itself.

If you’re struggling to get past the first sentence, try rewriting it. Write it in 10 words or write it in 200 words; write a single word sentence; experiment with metaphors, alliteration, or onomatopoeia . Then, once you’ve found the right words, build from there, and let your first sentence guide the style and mood of the narrative.

Now, let’s take a deeper look at the craft of fiction writing. The above elements are great starting points, but to learn how to start writing fiction, we need to examine the craft of combining these elements.

Primer on the Elements of Fiction Writing

First, before we get into the craft of fiction writing, it’s important to understand the elements of fiction. You don’t need to understand everything about the craft of fiction before you start keying in ideas or planning your novel. But this primer will be something you can consult if you need clarification on any term (e.g., point of view) as you learn how to start writing fiction.

The Elements of Fiction Writing

A standard novel runs between 80,000 to 100,000 words. A short novel, going by the National Novel Writing Month , is at least 50,000. To begin with, don’t think about length—think about development. Length will come. It is true that some works lend themselves more to novellas, but if that’s the case, you don’t want to pad them to make a longer work. If you write a plot summary—that’s one option on getting started writing fiction—you will be able to get a fairly good idea about your project as to whether it lends itself to a full-blown novel.

For now, let’s think about the various elements of fiction—the building blocks.

Writing Fiction: Your Protagonist

Readers want an interesting protagonist , or main character. One that seems real, that deals with the various things in life we all deal with. If the writer makes life too simple, and doesn’t reflect the kinds of problems we all face, most readers are going to lose interest.

Don’t cheat it. Make the work honest. Do as much as you can to develop a character who is fully developed, fully real—many-sided. Complex. In Aspects of the Novel , E.M Forster called this character a “round” characte r. This character is capable of surprising us. Don’t be afraid to make your protagonist, or any of your characters, a bit contradictory. Most of us are somewhat contradictory at one time or another. The deeper you see into your protagonist, the more complex, the more believable they will be.

If a character has no depth, is merely “flat,” as Forster terms it, then we can sum this character up in a sentence: “George hates his ex-wife.” This is much too limited. Find out why. What is it that causes George to hate his ex-wife? Is it because of something she did or didn’t do? Is it because of a basic personality clash? Is it because George can’t stand a certain type of person, and he didn’t realize, until too late, that his ex-wife was really that kind of person? Imagine some moments of illumination, and you will have a much richer character than one who just hates his ex-wife.

And so… to sum up: think about fleshing out your protagonist as much as you can. Consider personality, character (or moral makeup), inclinations, proclivities, likes, dislikes, etc. What makes this character happy? What makes this character sad or frustrated? What motivates your character? Readers don’t want to know only what —they want to know why .

Usually, readers want a sympathetic character, one they can root for. Or if not that, one that is interesting in different ways. You might not find the protagonist of The Girl on the Train totally sympathetic, but she’s interesting! She’s compelling.

Here’s an article I wrote on what makes a good protagonist.

Also on clichéd characters.

Now, we’re ready for a key question: what is your protagonist’s main goal in this story? And secondly, who or what will stand in the way of your character achieving this goal?

There are two kinds of conflicts: internal and external. In some cases, characters may not be opposing an external antagonist, but be self-conflicted. Once you decide on your character’s goal, you can more easily determine the nature of the obstacles that your protagonist must overcome. There must be conflict, of course, and stories must involve movement. Things go from Phase A to Phase B to Phase C, and so on. Overall, the protagonist begins here and ends there. She isn’t the same at the end of the story as she was in the beginning. There is a character arc.

I spoke of character arc. Now let’s move on to plot, the mechanism governing the overall logic of the story. What causes the protagonist to change? What key events lead up to the final resolution?

But before we go there, let’s stop a moment and think about point of view, the lens through which the story is told.

Writing Fiction: Point of View as Lens

Is this the right protagonist for this story? Is this character the one who has the most at stake? Does this character have real potential for change? Remember, you must have change or movement—in terms of character growth—in your story. Your character should not be quite the same at the end as in the beginning. Otherwise, it’s more of a sketch.

Such a story used to be called “slice of life.” For example, what if a man thinks his job can’t get any worse—and it doesn’t? He started with a great dislike for the job, for the people he works with, just for the pay. His hate factor is 9 on a scale of 10. He doesn’t learn anything about himself either. He just realizes he’s got to get out of there. The reader knew that from page 1.

Choose a character who has a chance of undergoing change of some kind. The more complex the change, the better. Characters that change are dynamic characters , according to E. M. Forster. Characters that remain the same are static characters. Be sure your protagonist is dynamic.

Okay, an exception: Let’s say your character resists change—that can involve some sort of movement—the resisting of change.

Here’s another thing to look at on protagonists—a blog I wrote: https://elizabethspanncraig.com/writing-tips-2/creating-strong-characters-typical-challenges/

Writing Fiction: Point of View and Person

Usually when we think of point of view, we have in mind the choice of person: first, second, and third. First person provides intimacy. As readers we’re allowed into the I-narrator’s mind and heart. A story told from the first person can sometimes be highly confessional, frank, bold. Think of some of the great first-person narrators like Huck Finn and Holden Caulfield. With first person we can also create narrators that are not completely reliable, leading to dramatic irony : we as readers believe one thing while the narrator believes another. This creates some interesting tension, but be careful to make your protagonist likable, sympathetic. Or at least empathetic, someone we can relate to.

What if a novel is told in first person from the point of view of a mob hit man? As author of such a tale, you probably wouldn’t want your reader to root for this character, but you could at least make the character human and believable. With first person, your reader would be constantly in the mind of this character, so you’d need to find a way to deal with this sympathy question. First person is a good choice for many works of fiction, as long as one doesn’t confuse the I-narrator with themselves. It may be a temptation, especially in the case of fiction based on one’s own life—not that it wouldn’t be in third person narrations. But perhaps even more with a first person story: that character is me . But it’s not—it’s a fictional character.

Check out my article on writing autobiographical fiction, which appeared in The Writer magazine. https://www.writermag.com/2018/07/31/filtering-fact-through-fiction/

Third person provides more distance. With third person, you have a choice between three forms: omniscient, limited omniscient, and objective or dramatic. If you get outside of your protagonist’s mind and enter other characters’ minds, you are being omniscient or godlike. If you limit your access to your protagonist’s mind only, this is limited omniscience. Let’s consider these two forms of third-person narrators before moving on to the objective or dramatic POV.

The omniscient form is rather risky, but it is certainly used, and it can certainly serve a worthwhile function. With this form, the author knows everything that has occurred, is occurring, or will occur in a given place, or in given places, for all the characters in the story. The author can provide historical background, look into the future, and even speculate on characters and make judgments. This point of view, writers tend to feel today, is more the method of nineteenth-century fiction, and not for today. It seems like too heavy an authorial footprint. Not handled well—and it is difficult to handle well—the characters seem to be pawns of an all-knowing author.

Today’s omniscience tends to take the form of multiple points of view, sometimes alternating, sometimes in sections. An author is behind it all, but the author is effaced, not making an appearance. BUT there are notable examples of well-handled authorial omniscience–read Nobel-prize winning Jose Saramago’s Blindness as a good example.

For more help, here’s an article I wrote on the omniscient point of view for The Writer : https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/omniscient-pov/

The limited omniscient form is typical of much of today’s fiction. You stick to your protagonist’s mind. You see others from the outside. Even so, you do have to be careful that you don’t get out of this point of view from time to time, and bring in things the character can’t see or observe—unless you want to stand outside this character, and therein lies the omniscience, however limited it is.

But anyway, note the difference between: “George’s smiles were very welcoming” and “George felt like his smiles were very welcoming”—see the difference? In the case of the first, we’re seeing George from the outside; in the case of the second, from the inside. It’s safer to stay within your protagonist’s perspective as much as possible and not describe them from the outside. Doing so comes off like a point-of-view shift. Yet it’s true that in some stories, the narrator will describe what the character is wearing, tell us what his hopes and dreams are, mention things he doesn’t know right now but will later—and perhaps, in rather quirky stories, the narrator will even say something like “Our hero…” This can work, and has, if you create an interesting narrative voice. But it’s certainly a risk.

The dramatic or objective point of view is one you’ll probably use from time to time, but not throughout your whole novel. Hemingway’s “Hills like White Elephants” is handled with this point of view. Mostly, with maybe one exception, all we know is what the characters say and do, as in a play. Using this point of view from time to time in a longer work can certainly create interest. You can intensify a scene sometimes with this point of view. An interesting back and forth can be accomplished, especially if the dialogue is clipped.

I’ve saved the second-person point of view for the last. I would advise you not to use this point of view for an entire work. In his short novel Bright Lights, Big City , Jay McInerney famously uses this point of view, and with some force, but it’s hard to pull off. In lesser hands, it can get old. You also cause the reader to become the character. Does the reader want to become this character? One problem with this point of view is it may seem overly arty, an attempt at sophistication. I think it’s best to choose either first or third.

Here’s an article I wrote on use of second person for The Writer magazine. Check it out if you’re interested. https://www.writermag.com/2016/11/02/second-person-pov/

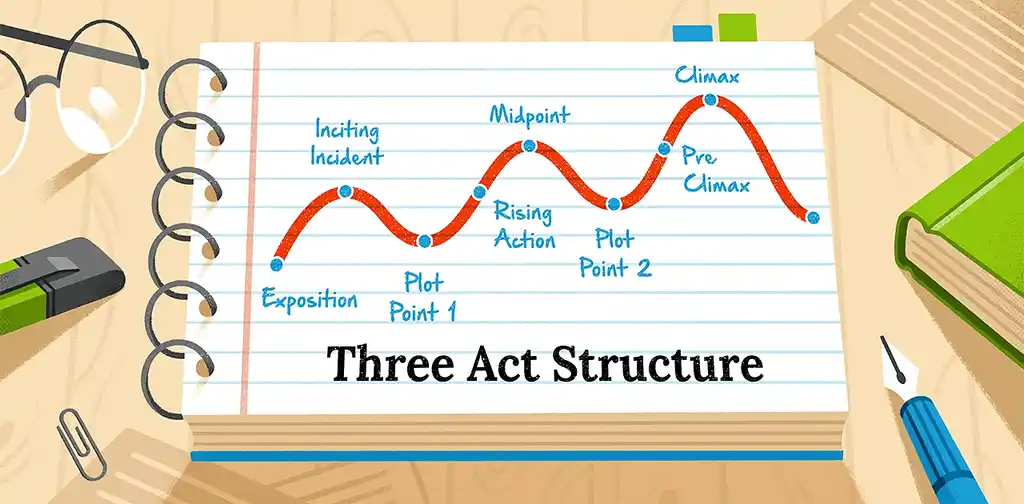

Writing Fiction: Protagonist and Plot and Structure

We come now to plot, keeping in mind character. You might consider the traditional five-stage structure : exposition, rising action, crisis and climax, falling action, and resolution. Not every plot works this way, but it’s a tried-and-true structure. Certainly a number of pieces of literature you read will begin in media re s—that is, in the middle of things. Instead of beginning with standard exposition, or explanation of the condition of the protagonist’s life at the story’s starting point, the author will begin with a scene. But even so, as in Jerzy Kosiński’s famous novella Being There , which begins with a scene, we’ll still pick up the present state of the character’s life before we see something that complicates it or changes the existing equilibrium. This so-called complication can be something apparently good—like winning the lottery—or something decidedly bad—like losing a huge amount of money at the gaming tables. One thing is true in both cases: whatever has happened will cause the character to change. And so now you have to fill in the events that bring this about.

How do you do that? One way is to write a chapter outline to prevent false starts. But some writers don’t like plotting in this fashion, but want to discover as they write. If you do plot your novel in advance, do realize that as you write, you will discover a lot of things about your character that you didn’t have in mind when you first set pen to paper. Or fingers to keyboard. And so, while it’s a good idea to do some planning, do keep your options open.

Let’s think some more about plot. To have a workable plot, you need a sequence of actions or events that give the story an overall movement. This includes two elements which we’ll take up later: foreshadowing and echoing (things that prepare us for something in the future and things that remind us of what has already happened). These two elements knit a story together.

Think carefully about character motivations. Some things may happen to your character; some things your character may decide to do, however wisely or unwisely. In the revision stage, if not earlier, ask yourself: What motivates my character to act in one way or another? And ask yourself: What is the overall logic of this story? What caused my character to change? What were the various forces, whether inner or outer, that caused this change? Can I describe my character’s overall arc, from A to Z? Try to do that. Write a short paragraph. Then try to write down your summary in one sentence, called a log line in film script writing, but also a useful technique in fiction writing as well. If you write by the discovery method, you probably won’t want to do this in the midst of the drafting, but at least in the revision stage, you should consider doing so.

With a novel you may have a subplot or two. Assuming you will, you’ll need to decide how the plot and the subplot relate. Are they related enough to make one story? If you think the subplot is crucial for the telling of your tale, try to say why—in a paragraph, then in a sentence.

Here’s an article I wrote on structure for The Writer : https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/revision-grammar/find-novels-structure/

Writing Fiction: Setting

Let’s move on to setting . Your novel has to take place somewhere. Where is it? Is it someplace that is particularly striking and calls for a lot of solid description? If it’s a wilderness area where your character is lost, give your reader a strong sense for the place. If it’s a factory job, and much of the story takes place at the worksite, again readers will want to feel they’re there with your character, putting in the hours. If it’s an apartment and the apartment itself isn’t related to the problems your character is having, then there’s no need to provide that much detail. Exception: If your protagonist concentrates on certain things in the apartment and begins to associate certain things about the apartment with their misery, now there’s reason to get concrete. Take a look, when you have a chance, at the short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper.” It’s not an apartment—it’s a house—but clearly the setting itself becomes important when it becomes important to the character. She reads the wallpaper as a statement about her own condition.

Here’s the URL for ”The Yellow Wall-Paper”: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/theliteratureofprescription/exhibitionAssets/digitalDocs/The-Yellow-Wall-Paper.pdf

Sometimes setting is pretty important; sometimes it’s much less important. When it doesn’t serve a purpose to describe it, don’t, other than to give the reader a sense for where the story takes place. If you provide very many details, even in a longer work like a novel, the reader will think that these details have some significance in terms of character, plot, or theme—or all three. And if they don’t, why are they there? If setting details are important, be selective. Provide a dominant impression. More on description below.

If you’re interested, here’s a blog on setting I wrote for Writers.com: https://writers.com/what-is-the-setting-of-a-story

Writing Fiction: Theme and Idea

Most literary works have a theme or idea. It’s possible to decide on this theme before you write, as you plan out your novel. But be careful here. If the theme seems imposed on the work, the novel will lose a lot of force. It will seem—and it may well be—engineered by the author much like a nonfiction piece, and lose the felt experience of the characters.

Theme must emerge from the work naturally, or at least appear to do so. Once you have a draft, you can certainly build ideas that are apparent in the work, and you can even do this while you’re generating your first draft. But watch out for overdoing it. Let the characters (what they do, what they say) and the plot (the whole storyline with its logical connections) contribute on their own to the theme. Also you can depend on metaphors, similes, and analogies to point to the theme—as long as these are not heavy-handed. Avoid authorial intrusion, authorial impositions of any kind. If you do end up creating a simile, metaphor, or analogy through rational thinking, make sure it sounds natural. That’s not easy, of course.

Writing Fiction: Handling Scenes

Keep a few things in mind about writing scenes. Not every event deserves a whole scene, maybe only a half-scene, a short interaction between characters. Scenes need to do two things: reveal character and advance plot. If a scene seems to stall out and lack interest, in the revision mode you might try using narrative summary instead (see below).

Good fiction is strongly dramatic, calling for scenes, many of them scenes with dialogue and action. Scenes need to involve conflict of some kind. If everyone is happy, that’s probably going to be a dull scene. Some scenes will be narrative, without dialogue. You need some interesting action to make these work.

Let’s consider scenes with dialogue.

The best dialogue is speech that sounds natural, and yet isn’t. Everything about fiction is an artifice, including speech. But try to make it sound real. The best way to do this is to “hear” the voices in your head and transcribe them. Take dictation. If you can do this, whole conversations will seem very real, believable. If you force what each character has to say, and plan it out too much, it will certainly sound planned out, and not real at all. Not that in the revision mode you can’t doctor up the speech here and there, but still, make sure it comes off as natural sounding.

Some things to think about when writing dialogue: people usually speak in fragments, interrupt each other, engage in pauses, follow up a question with a comment that takes the conversation off course (non sequiturs). Note these aspects of dialogue in the fiction you read.

Also, note how writers intersperse action with dialogue, setting details, and character thoughts. As far as the latter goes, though, if you’ll recall, I spoke of the dramatic point of view, which doesn’t get into a character’s mind but depends instead on what characters do and say, as in a play. You may try this point of view out in some scenes to make them really move.

One technique is to use indirect dialogue, or summary of what a character said, not in the character’s own words. For instance: Bill made it clear that he wasn’t going to the city after all. If anybody thought that, they were wrong .

Now and then you’ll come upon dialogue that doesn’t use the standard double quotes, but perhaps a single quote (this is British), or dashes, or no punctuation at all. The latter two methods create some distance from the speech. If you want to give your work a surreal quality, this certainly adds to it. It also makes it seem more interior.

One way to kill good dialogue is to make characters too obviously expository devices—that is, functioning to provide background or explanations of certain important story facts. Certainly characters can serve as expository devices, but don’t be too heavy-handed about this. Don’t force it like the following:

“We always used to go to the beach, you recall? You recall how first we would have breakfast, then take a long walk on the beach, and then we would change into our swimsuits, and spend an hour in the water. And you recall how we usually followed that with a picnic lunch, maybe an hour later.”

This sounds like the character is saying all this to fill the reader in on backstory. You’d need a motive for the utterance of all of these details—maybe sharing a memory?

But the above sounds stilted, doesn’t it?

One final word about dialogue. Watch out for dialogue tags that tell but don’t show . Here’s an example:

“Do you think that’s the case,” said Ted, hoping to hear some good news. “Not necessarily,” responded Laura, in a barky voice. “I just wish life wasn’t so difficult,” replied Ted.

If you’re going to use a tag at all—and many times you don’t need to—use “said.” Dialogue tags like the above examples can really kill the dialogue.

Writing Fiction: Writing Solid Prose

Narrative summary : As I’ve stated above, not everything will be a scene. You’ll need to write narrative summary now and then. Narrative summary telescopes time, covering a day, a week, a month, a year, or even longer. Often it will be followed up by a scene, whether a narrative scene or one with dialogue. Narrative summary can also relate how things generally went over a given period. You can write strong narrative summary if you make it specific and concrete—and dramatic. Also, if we hear the voice of the writer, it can be interesting—if the voice is compelling enough.

Exposition : It’s the first stage of the 5-stage plot structure, where things are set up prior to some sort of complication, but more generally, it’s a prose form which tells or informs. You use exposition when you get inside your character, dealing with his or her thoughts and emotions, memories, plans, dreams. This can be difficult to do well because it can come off too much like authorial “telling” instead of “showing,” and readers want to feel like they’re experiencing the world of the protagonist, not being told about this world. Still, it’s important to get inside characters, and exposition is often the right tool, along with narrative summary, if the character is remembering a sequence of events from the past.

Description : Description is a word picture, providing specific and concrete details to allow the reader to see, not just be told. Concreteness is putting the reader in the world of the five senses, what we call imagery . Some writers provide a lot of details, some only a few—just enough that the reader can imagine the rest. Consider choosing details that create a dominant impression—whether it’s a character or a place. Similes, metaphors, and analogies help readers see people and places and can make thoughts and ideas (the reflections of your character or characters) more interesting. Not that you should always make your reader see. To do so might cause an overload of images.

Check out these two articles: https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/the-definitive-guide-to-show-dont-tell/ https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/figurative-language-in-fiction/

Writing Fiction: Research

Some novels require research. Obviously historical novels do, but others do, too, like Sci Fi novels. Almost any novel can call for a little research. Here’s a short article I wrote for The Writer magazine on handling research materials. It’s in no way an in-depth commentary on research–but it will serve as an introduction. https://www.writermag.com/improve-your-writing/fiction/research-in-fiction/

For a blog on novel writing, check this link at Writers.com: https://writers.com/novel-writing-tips

For more articles I’ve published in The Writer , go here: https://www.writermag.com/author/jack-smith/

How to Start Writing Fiction: Take a Writing Class!

To write a story or even write a book, fiction writers need these tools first and foremost. Although there’s no comprehensive guide on how to write fiction for beginners, working with these elements of fiction will help your story bloom.

All six elements synergize to make a work of fiction, and like most works of art, the sum of these elements is greater than the individual parts. Still, you might find that you struggle with one of these elements, like maybe you’re great at writing characters but not very good with exploring setting. If this is the case, then use your strengths: use characters to explore the setting, or use style to explore themes, etc.

Getting the first draft written is the hardest part, but it deserves to be written. Once you’ve got a working draft of a story or novel and you need an extra set of eyes, the Writers.com community is here to give feedback: take a look at our upcoming courses on fiction writing, and check out our talented writing community .

Good luck, and happy writing!

I have had a story in my mind for over 15 years. I just haven’t had an idea how to start , putting it down on print just seems too confusing. After reading this article I’m even more confused but also more determined to give it a try. It has given me answers to some of my questions. Thank you !

You’ve got this, Earl!

Just reading this as I have decided to attempt a fiction work. I am terrible at writing outside of research papers and such. I have about 50 single spaced pages “written” and an entire outline. These tips are great because where I struggle it seems is drawing the reader in. My private proof reader tells me it is to much like an explanation and not enough of a story, but working on it.

first class

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

How to Write Good Fiction: 4 Foundational Skills and How to Build Them

by J. D. Edwin | 0 comments

Want to Become a Published Author? In 100 Day Book, you’ll finish your book guaranteed. Learn more and sign up here.

Do you want to write a novel but are unsure how to write good fiction? Let's look at the skills you need to do it well.

Writing good fiction takes time and practice. There's no way around it.

However, if you're looking for some specific and valuable writing skills that you should concentrate on improving, this post is for you.

Here, learn the four foundational writing skills that will make you a better fiction writer, with practical tips to better your writing craft.

This article is an excerpt from J. Danforth's new book The Write Fast System . The book teaches writers how to write a fast first draft—in six weeks.

Once Upon a Time, I Didn't Know What Was Wrong With My Book

I have personal experience with moving too fast.

A number of years ago (almost ten years now; my how time flies), I finished writing my first novel. I had a vague premise, did no planning, and just dove in and wrote it. I pantsed a 150K word novel, a few pages at a time, over a period of three years. When it was done, I went through the laborious steps of professional editing and self-publishing, and then put it out into the world.

It sold eleven copies to friends and family.

I didn’t do much to promote it and it sank like a stone into the obscurity of the internet. A big part of this was that I didn’t know how to properly market a book back then, but there was another, deeper reason that I didn’t promote this book.

It wasn’t good.

For a first attempt, I suppose it wasn’t terrible. But even back then, reveling in having published a book, I had the nagging doubt in the back of my mind. And at the end of the day, I couldn’t bring myself to ask for support for a book that I didn’t believe was good. How could I ask other people to believe in a book that I didn’t believe in myself?

Back then, I didn’t understand why my book wasn’t good.

To recognize a book lacking in quality was one thing, but to fix it was another. When I tried to pinpoint how to improve it, or even identify what exactly was wrong, I turned up blank. And so, the book never went anywhere.

However, now a decade older and wiser, I know what was wrong.

4 Problems With Books That Aren't Good

My book was plagued by four major problems.

1. Terrible Structure

The book had a terrible structure due to lack of planning. It dragged in some places and covered too much too fast at others. I didn't advance plot in a way that made sense.

I was so occupied with filling a blank page that I never thought about structure. This was a huge problem.

2. Too Many Characters, Not Enough Development

The book had too many characters and not enough development.

While I was truly proud of a few of the characters I created, there were also some who didn’t serve adequate purpose in furthering the story.

Rather than fixing the plot, I dealt with difficult areas by simply sticking another character in it.

3. Too Much Description

Compared to other aspects of writing, I’m good at description. However, I overused it in this book.

I described details down to the minute. Unnecessary details, and I spent far too much time setting up scenes that only got used for a few short moments.

So while my descriptions were written well, they were used poorly and took away from the story rather than enriching it.

4. Needless Dialogue

My characters talked a lot. Correction—my characters talked a lot without saying very much. There were conversations that accomplished nothing or led nowhere.

Do you know what that’s called? It’s called “boring.”

A book with characters who talk in a boring manner is a boring book. Seriously, no one cares what they had for breakfast that day or what was on the radio on their way to work.

Move on with the story already.

How to Write Good Fiction: 4 Foundational Skills

I’m far from the first person to have these aforementioned problems.

In fact, these are some of the most common problems with novels and short stories that “just don’t work.”

When you’re a new writer starting out, figuring out exactly why your book isn’t working can be a confusing and difficult task.

However, when you understand the four foundational skills of writing, you can not only figure out why your story isn’t living up to its potential, but also understand how to change what's holding it back.

The four foundational skills needed to write good fiction are:

1. Strong Structure

I'm sure you’ve heard this word a lot, and this isn’t the post to go into detail about structure. But to put it simply, structure is how the story progresses and how its events are organized. Great fiction has great story structure. Look at any award-winning bestseller or just an all-around good story, and you will see strong structure.

Structure is where you decide what starts the story, what plot points lead the protagonist to make the decisions they do, what occurs that drives the characters, and what ultimately leads up to the climax where everything comes to a head.

To get used to working with structure, it's important to get into the habit of thinking of a book idea in terms of structure, even before starting a first draft.

When a story idea occurs to you, instead of letting it sit as a vague concept (e.g. MC goes on an adventure), try to divide it into the key components that would make up a story—why does MC go on this adventure? What prevents this adventure from going well? What is the goal of the adventure? How does MC change for the better or worse after this adventure? That will help you sketch out the character arc.

Key components in a story's structure also contain the story's main scenes, which should turn on the driving Value for the story's plot type. In most stories, there are fourteen to twenty main scenes in a plot, and at The Write Practice, there are six main plot types that turn on different Values to consider:

Make this part of your writing process and think about what happens in your story step-by-step. Learning to think of an idea in terms of structure will help you get a better look of your whole book right off the bat.

If your story isn’t working from a structural standpoint, ask yourself:

- Is there an important piece of the structure missing?

- Have I looked at the story and felt satisfied that it makes sense as a whole?

- Do the events of the story proceed logically and give adequate reason for the characters doing what they do?

For further reference on structure, visit the following articles:

- Six Elements of Plot

- Three Act Structure

2. Develop Characters and Emotions

Your story, at the end of the day, is about someone.

There aren’t a lot of stories out there that aren’t about a character or a cast of characters. But characters are tricky. You need a cast just big enough that every necessary role in the story is filled, but not so many that you fling characters around like a box of spilled beans, so many that readers can't keep character names straight.

In addition to that, your characters need to be distinguishable from each other, having unique reactions and emotions. If your readers can’t tell your characters apart, then it’s not going to make for a very fun read.

A character often comes to mind as an image and a name. But the fact is, a character, main character or otherwise, is so much more than that.

When you imagine a character, try to think beyond the who and focus more on the why of this person—this delves into character motivation.

Why do they do what they do? What in their life has brought them to this point? They're more than just a “happy person” or a “miserable miser.” What makes this character happy or miserable?

When someone wants to know how your day was, you might say “good” or “bad,” and proceed to follow up what's good or bad about it.

A conversation with your character to get to know them is the same. Ask them real question and listen to their answers to write richer characters.

You might be surprised at just how deep and unique they are.

If your story isn’t working from a character standpoint, ask yourself:

- Is every character in the story absolutely necessary? Can some of them be combined?

- Does every action taken by your character move the story forward? If not, they should probably be doing something else, or that part should simply be skipped.

- Does the way each character reacts to major events reflect who they are as a person? Why do they react this way and are the readers aware of the reason?

For further references on writing characters, visit the following posts:

- Character Development

- Sympathetic Character

- How to Write a Villain

3. Description and Setting

Description provides the visual for your story. Anyone can tell you what something looks like, but using description correctly is actually quite difficult.

It’s important to be aware of what needs to be described and what doesn’t. An object important to the plot may deserve a page of description, but a passerby on the street who isn’t important to the story does not.

The other part of this is that when you go about describing a setting, every component you mention should have some significance to the story. It's not merely about how much description you need to give something important, but also how much you focus on individual parts of it as well.

This principle, quoted frequently in writing courses, is known as Chekhov's Gun, which states that every element in a story must be necessary.

As Chekhov says:

“Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it's not going to be fired, it shouldn't be hanging there.”

If your story isn’t working from a description standpoint, ask yourself:

- Have I adequately described all the important objects and settings in the story? Can my readers visualize these things easily?

- Have I overdescribed things that don’t need to be described?

- Are my descriptions interesting? Have I used too many old cliches?

For further reference on description, visit the following articles:

- Immerse Your Reader in the Setting

- World Building Tip

- The Key to Writing Descriptions

4. Dialogue

There is nothing more active in a story than talking. Dialogue and interaction between characters brings the reader into the situation and gets them involved. But boring, unnecessary dialogue pulls them out just as quickly.

No one wants to read two characters talking about nothing. Dialogue showcases your characters’ personality as well, and bad dialogue means bad characters, no matter how pretty their “golden hair” and “emerald eyes” are.

A useful habit to get into when writing scenes with dialogue is to set a goal for the scene. Where do your characters start talking and where do you want them to end up? How can you pair action with dialogue?

Is the goal of the conversation to discuss a problem and reach a solution? Maybe the goal is to show how much two characters love each other? Is it for the readers to understand a particular aspect of their personality and situation?

Once you understand where you want your characters to end up after the conversation is over, you'll have a much better idea of what needs (and doesn't need) to be said.

If your story isn’t working from a dialogue standpoint, ask yourself:

- Do my characters talk too much? Does every word they say either move the plot forward or show something about the character?

- Do my characters use too many words to get to their point? Sometimes the few words they say, the more impactful their language.

- Do the things my characters say reflect their personality? Is it accurate to their back story and motivation? Consistency is key.

For further reference on description, visit the following posts:

- Writing Brilliant Dialogue

- Dialogue Tags

- A Critical Don't for Writing Dialogue

4 Ways to Strengthen Your Foundational Fiction Writing Skills

Now that we’ve identified the skills necessary to make a story work, how does one actually go about getting better at these skills? It may seem overwhelming at first, but in reality, it doesn’t take more than a consistent investment of time.

When I set out to improve my writing skills a few years ago, it felt like a terribly daunting task. Get better at writing? How on Earth do I accomplish that?

In the end, it didn’t end up taking very much time at all. In fact, within three years of starting to work on my writing skills, I had written another book. A better book. A book with a tight structure, well-rounded characters, far improved dialogue, and just the right amount of descriptions.

A book I can be proud of and stand behind, and actually have enough confidence in to promote. It's called Headspace (and it's available now !).

Not only does building foundational skills improve your writing, it helps with revising and self-editing as well. So how do you strengthen your skills?

1. Read books on writing

There are a lot of books about writing. But I am specifically referring, in this case, to books that focus on these four skill areas.

Look for books written by established fiction authors. These are the people who speak from experience and give practical, usable advice.

Some people don't believe writing can be taught. To those people, I ask:

Would you fix a car without first consulting a manual or taking a class?

Or put together a shelf without instructions?

Would you practice law without learning about the laws first?

Books on writing skills offer you the building blocks you need to create your story, and like building a house, you can’t put up the frame without a solid foundation.

For more on how to read productively as a writer, check out this post on what you should read .

2. Read fiction analytically

We all love to read. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t be writers. However, reading to learn and reading for pleasure are two entirely different focuses.

Most of the time, we read fiction to get lost in the story, to become completely immersed and forget that what we’re doing is looking at words on paper. Many of us like to relax with Harry Potter or chew our nails while reading Stephen King .

But to read analytically, we must fight that impulse. It's hard work, but well worth it.

Rather than getting lost, we need to be aware throughout the story and look at it from an objective point of view.

As you read to analyze and learn, try a few different strategies.

6 Ways to Read Analytically (and Learn to Write Better)

- Make note of things you like about the book and try to determine why you like them and how you can replicate the same effect in your own book.

- Make note of things you didn’t like, determine why you didn’t like them, and decide how you can avoid these things in your book.

- Observe the order of events and how they lead up to the whole.

- Take note of descriptions that are vivid and effective. It may even be useful to copy these into a list somewhere for future reference.

- Dissect the book and see how it fulfills each part of the storytelling structure.

3. Write short stories

Short stories are incredibly important. A lot of writers who are used to writing long pieces have a hard time with short stories. Trust me, I used to be one of these people.

But short stories have enormous benefits. Here are three reasons they're fantastic practice for writers:

- They contain all the elements of structure and allow you to see them all at once in the space of only a few pages.

- They are a smaller commitment and less daunting to finish..

- Every word counts in short stories, which is incredibly helpful when you want to practice keeping your writing tight.

Try to make writing short stories a part of your writing life. If nothing else, sharing your short stories is a great (free!) offer to get readers interested in subscribing to your email list.

When you’re not sure what to write, write a short story, or even flash fiction, which is a very short story, as short as just a few words.

Short stories keep the gears turning and your skills fresh. The more short stories you write, the better your skills will be for writing books.