Center for Teaching Innovation

Resource library.

- Establishing Community Agreements and Classroom Norms

- Sample group work rubric

- Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse of Activities, University of Delaware

Problem-Based Learning

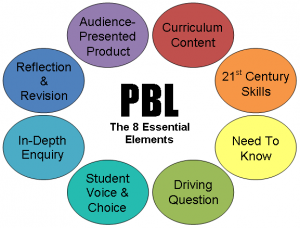

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered approach in which students learn about a subject by working in groups to solve an open-ended problem. This problem is what drives the motivation and the learning.

Why Use Problem-Based Learning?

Nilson (2010) lists the following learning outcomes that are associated with PBL. A well-designed PBL project provides students with the opportunity to develop skills related to:

- Working in teams.

- Managing projects and holding leadership roles.

- Oral and written communication.

- Self-awareness and evaluation of group processes.

- Working independently.

- Critical thinking and analysis.

- Explaining concepts.

- Self-directed learning.

- Applying course content to real-world examples.

- Researching and information literacy.

- Problem solving across disciplines.

Considerations for Using Problem-Based Learning

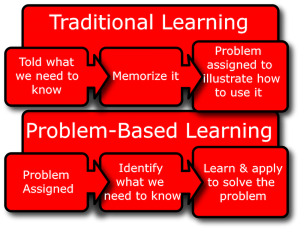

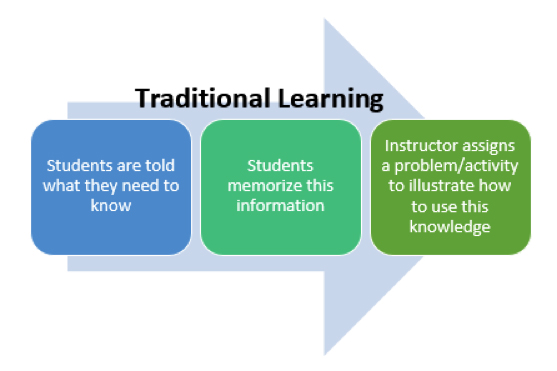

Rather than teaching relevant material and subsequently having students apply the knowledge to solve problems, the problem is presented first. PBL assignments can be short, or they can be more involved and take a whole semester. PBL is often group-oriented, so it is beneficial to set aside classroom time to prepare students to work in groups and to allow them to engage in their PBL project.

Students generally must:

- Examine and define the problem.

- Explore what they already know about underlying issues related to it.

- Determine what they need to learn and where they can acquire the information and tools necessary to solve the problem.

- Evaluate possible ways to solve the problem.

- Solve the problem.

- Report on their findings.

Getting Started with Problem-Based Learning

- Articulate the learning outcomes of the project. What do you want students to know or be able to do as a result of participating in the assignment?

- Create the problem. Ideally, this will be a real-world situation that resembles something students may encounter in their future careers or lives. Cases are often the basis of PBL activities. Previously developed PBL activities can be found online through the University of Delaware’s PBL Clearinghouse of Activities .

- Establish ground rules at the beginning to prepare students to work effectively in groups.

- Introduce students to group processes and do some warm up exercises to allow them to practice assessing both their own work and that of their peers.

- Consider having students take on different roles or divide up the work up amongst themselves. Alternatively, the project might require students to assume various perspectives, such as those of government officials, local business owners, etc.

- Establish how you will evaluate and assess the assignment. Consider making the self and peer assessments a part of the assignment grade.

Nilson, L. B. (2010). Teaching at its best: A research-based resource for college instructors (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

What is Problem-Based Learning (PBL)? PBL is a student-centered approach to learning that involves groups of students working to solve a real-world problem, quite different from the direct teaching method of a teacher presenting facts and concepts about a specific subject to a classroom of students. Through PBL, students not only strengthen their teamwork, communication, and research skills, but they also sharpen their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities essential for life-long learning.

See also: Just-in-Time Teaching

In implementing PBL, the teaching role shifts from that of the more traditional model that follows a linear, sequential pattern where the teacher presents relevant material, informs the class what needs to be done, and provides details and information for students to apply their knowledge to a given problem. With PBL, the teacher acts as a facilitator; the learning is student-driven with the aim of solving the given problem (note: the problem is established at the onset of learning opposed to being presented last in the traditional model). Also, the assignments vary in length from relatively short to an entire semester with daily instructional time structured for group work.

By working with PBL, students will:

- Become engaged with open-ended situations that assimilate the world of work

- Participate in groups to pinpoint what is known/ not known and the methods of finding information to help solve the given problem.

- Investigate a problem; through critical thinking and problem solving, brainstorm a list of unique solutions.

- Analyze the situation to see if the real problem is framed or if there are other problems that need to be solved.

How to Begin PBL

- Establish the learning outcomes (i.e., what is it that you want your students to really learn and to be able to do after completing the learning project).

- Find a real-world problem that is relevant to the students; often the problems are ones that students may encounter in their own life or future career.

- Discuss pertinent rules for working in groups to maximize learning success.

- Practice group processes: listening, involving others, assessing their work/peers.

- Explore different roles for students to accomplish the work that needs to be done and/or to see the problem from various perspectives depending on the problem (e.g., for a problem about pollution, different roles may be a mayor, business owner, parent, child, neighboring city government officials, etc.).

- Determine how the project will be evaluated and assessed. Most likely, both self-assessment and peer-assessment will factor into the assignment grade.

Designing Classroom Instruction

See also: Inclusive Teaching Strategies

- Take the curriculum and divide it into various units. Decide on the types of problems that your students will solve. These will be your objectives.

- Determine the specific problems that most likely have several answers; consider student interest.

- Arrange appropriate resources available to students; utilize other teaching personnel to support students where needed (e.g., media specialists to orientate students to electronic references).

- Decide on presentation formats to communicate learning (e.g., individual paper, group PowerPoint, an online blog, etc.) and appropriate grading mechanisms (e.g., rubric).

- Decide how to incorporate group participation (e.g., what percent, possible peer evaluation, etc.).

How to Orchestrate a PBL Activity

- Explain Problem-Based Learning to students: its rationale, daily instruction, class expectations, grading.

- Serve as a model and resource to the PBL process; work in-tandem through the first problem

- Help students secure various resources when needed.

- Supply ample class time for collaborative group work.

- Give feedback to each group after they share via the established format; critique the solution in quality and thoroughness. Reinforce to the students that the prior thinking and reasoning process in addition to the solution are important as well.

Teacher’s Role in PBL

See also: Flipped teaching

As previously mentioned, the teacher determines a problem that is interesting, relevant, and novel for the students. It also must be multi-faceted enough to engage students in doing research and finding several solutions. The problems stem from the unit curriculum and reflect possible use in future work situations.

- Determine a problem aligned with the course and your students. The problem needs to be demanding enough that the students most likely cannot solve it on their own. It also needs to teach them new skills. When sharing the problem with students, state it in a narrative complete with pertinent background information without excessive information. Allow the students to find out more details as they work on the problem.

- Place students in groups, well-mixed in diversity and skill levels, to strengthen the groups. Help students work successfully. One way is to have the students take on various roles in the group process after they self-assess their strengths and weaknesses.

- Support the students with understanding the content on a deeper level and in ways to best orchestrate the various stages of the problem-solving process.

The Role of the Students

See also: ADDIE model

The students work collaboratively on all facets of the problem to determine the best possible solution.

- Analyze the problem and the issues it presents. Break the problem down into various parts. Continue to read, discuss, and think about the problem.

- Construct a list of what is known about the problem. What do your fellow students know about the problem? Do they have any experiences related to the problem? Discuss the contributions expected from the team members. What are their strengths and weaknesses? Follow the rules of brainstorming (i.e., accept all answers without passing judgment) to generate possible solutions for the problem.

- Get agreement from the team members regarding the problem statement.

- Put the problem statement in written form.

- Solicit feedback from the teacher.

- Be open to changing the written statement based on any new learning that is found or feedback provided.

- Generate a list of possible solutions. Include relevant thoughts, ideas, and educated guesses as well as causes and possible ways to solve it. Then rank the solutions and select the solution that your group is most likely to perceive as the best in terms of meeting success.

- Include what needs to be known and done to solve the identified problems.

- Prioritize the various action steps.

- Consider how the steps impact the possible solutions.

- See if the group is in agreement with the timeline; if not, decide how to reach agreement.

- What resources are available to help (e.g., textbooks, primary/secondary sources, Internet).

- Determine research assignments per team members.

- Establish due dates.

- Determine how your group will present the problem solution and also identify the audience. Usually, in PBL, each group presents their solutions via a team presentation either to the class of other students or to those who are related to the problem.

- Both the process and the results of the learning activity need to be covered. Include the following: problem statement, questions, data gathered, data analysis, reasons for the solution(s) and/or any recommendations reflective of the data analysis.

- A well-stated problem and conclusion.

- The process undertaken by the group in solving the problem, the various options discussed, and the resources used.

- Your solution’s supporting documents, guests, interviews and their purpose to be convincing to your audience.

- In addition, be prepared for any audience comments and questions. Determine who will respond and if your team doesn’t know the answer, admit this and be open to looking into the question at a later date.

- Reflective thinking and transfer of knowledge are important components of PBL. This helps the students be more cognizant of their own learning and teaches them how to ask appropriate questions to address problems that need to be solved. It is important to look at both the individual student and the group effort/delivery throughout the entire process. From here, you can better determine what was learned and how to improve. The students should be asked how they can apply what was learned to a different situation, to their own lives, and to other course projects.

See also: Kirkpatrick Model: Four Levels of Learning Evaluation

I am a professor of Educational Technology. I have worked at several elite universities. I hold a PhD degree from the University of Illinois and a master's degree from Purdue University.

Similar Posts

Cognitive apprenticeship.

Apprenticeship is an ancient idea; skills have been taught by others for centuries. In the past, elders worked alongside their children to teach them how to grow food, wash their clothes, build homes…

Definitions of The Addie Model

What is the ADDIE Model? This article attempts to explain the ADDIE model by providing different definitions. Basically, ADDIE is a conceptual framework. ADDIE is the most commonly used instructional design framework and…

Gamification, What It Is, How It Works, Examples

For many students, the traditional classroom setting can feel like an uninspiring environment. Long lectures, repetitive tasks, and a focus on exams often leave young minds disengaged, craving a more dynamic way to…

Educational Technology: An Overview

Educational technology is a field of study that investigates the process of analyzing, designing, developing, implementing, and evaluating the instructional environment and learning materials in order to improve teaching and learning. It is…

Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

In 1950, Erik Erikson released his book, Childhood and Society, which outlined his now prominent Theory of Psychosocial Development. His theory comprises of 8 stages that a healthy individual passes through in his…

Planning for Educational Technology Integration

Why seek out educational technology? We know that technology can enhance the teaching and learning process by providing unique opportunities. However, we also know that adoption of educational technology is a highly complex…

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

Problem based learning.

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered pedagogy based on the constructivist learning theory through collaboration and self-directed learning. With PBL, students create knowledge and comprehension of a subject through the experience of solving an open-ended problem without a defined solution. Rather than focusing on learning problem-solving, PBL allows for the development of self-directed knowledge acquisition, along with enhanced teamwork and communication skills. Although originally developed for medical education, its use has expanded to other disciplines.

With PBL, the instructor’s role is to guide and challenge the learning process, rather than provide knowledge, while students engage in knowledge construction through teamwork. In alignment with constructivist theory, PBL promotes lifelong learning through inquiry.

Advantages:

- Student-centered learning;

- Promotes self-learning and self-motivation;

- Focuses on comprehension and higher level learning, rather than facts;

- Enhances critical appraisal skills;

- Develops literature retrieval and evaluation skills;

- Develops interpersonal skills and teamwork; and

- Promotes lifelong learning

Disadvantages:

- Instructor comfort with removing themselves from the central role;

- Student lack of acceptance of a different format of learning;

- Need for assessments that measure new knowledge and skills, such as practical exams, essays, peer and self assessments; and

- Time necessary to prepare course materials and assess

During the PBL process, students work in groups of 10-15 students supported by a tutor. The students are presented with a problem and, through group collaboration, activate their prior knowledge. The group develops hypotheses to explain the problem and identify issues to be researched which will help them to construct a shared explanation of the problem. After the initial teamwork, students work independently to research the identified issues, followed by discussion with the group about their findings and creation of a final explanation of the problem based on what they learned. The cycle can be repeated as needed.

The seven steps in the Maastricht PBL process are:

- Discuss the case to ensure everyone understands the problem;

- Identify questions in need of answers to fully understand the problem;

- Brainstorm what prior knowledge the group already has and identify potential solutions;

- Analyze and structure the findings from the brainstorming session;

- Formulate learning objectives for any lacking knowledge;

- Independently, research the information necessary to achieve the learning objectives defined as a group; and

- Discuss the findings with the group to develop a collective explanation of the problem.

In PBL learning, students in the group all serve a role. The roles should alternate through students for different problems. The tutor role is typically held by a instructor or teaching assistant who facilitates learning.

- Facilitates learning by supporting and guiding;

- Monitors the learning process

- Aims to build students' confidence

- Checks group understanding

- Assesses performance

- Encourages all group members to participate

- Keeps group on topic

- Assists with group dynamics

- Assists with time keeping

- Ensures records kept by scribe are accurate

- Leads group through process

- Ensures group remains on topic

- Encourages members to participate

- Maintains group dynamics

- Ensures scribe can keep up with accurate documentation

Group Member

References and Resources:

Duch, Barbara J.; Groh, Susan; Allen, Deborah E. (2001). The power of problem-based learning : a practical "how to" for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline (1st ed.). Sterling, VA: Stylus Pub.

Schmidt, Henk G; Rotgans, Jerome I; Yew, Elaine HJ (2011). "The process of problem-based learning: What works and why". Medical Education. 45 (8): 792–806.

Wood, D. F. (2003). "ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Problem based learning"

Quick Links

- Developing Learning Objectives

- Creating Your Syllabus

- Active Learning

- Service Learning

- Critical Thinking and other Higher-Order Thinking Skills

- Case Based Learning

- Group and Team Based Learning

- Integrating Technology in the Classroom

- Effective PowerPoint Design

- Hybrid and Hybrid Limited Course Design

- Online Course Design

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.

Problem-Based Learning: What and How Do Students Learn?

- Published: September 2004

- Volume 16 , pages 235–266, ( 2004 )

Cite this article

- Cindy E. Hmelo-Silver 1

45k Accesses

2068 Citations

259 Altmetric

32 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Problem-based approaches to learning have a long history of advocating experience-based education. Psychological research and theory suggests that by having students learn through the experience of solving problems, they can learn both content and thinking strategies. Problem-based learning (PBL) is an instructional method in which students learn through facilitated problem solving. In PBL, student learning centers on a complex problem that does not have a single correct answer. Students work in collaborative groups to identify what they need to learn in order to solve a problem. They engage in self-directed learning (SDL) and then apply their new knowledge to the problem and reflect on what they learned and the effectiveness of the strategies employed. The teacher acts to facilitate the learning process rather than to provide knowledge. The goals of PBL include helping students develop 1) flexible knowledge, 2) effective problem-solving skills, 3) SDL skills, 4) effective collaboration skills, and 5) intrinsic motivation. This article discusses the nature of learning in PBL and examines the empirical evidence supporting it. There is considerable research on the first 3 goals of PBL but little on the last 2. Moreover, minimal research has been conducted outside medical and gifted education. Understanding how these goals are achieved with less skilled learners is an important part of a research agenda for PBL. The evidence suggests that PBL is an instructional approach that offers the potential to help students develop flexible understanding and lifelong learning skills.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Problem-Based Learning: Conception, Practice, and Future

Designing Problem-Solving for Meaningful Learning: A Discussion of Asia-Pacific Research

Effective Learning Behavior in Problem-Based Learning: a Scoping Review

Abrandt Dahlgren, M., and Dahlgren, L. O. (2002). Portraits of PBL: Students' experiences of the characteristics of problem-based learning in physiotherapy, computer engineering, and psychology. Instr. Sci. 30: 111-127.

Google Scholar

Albanese, M. A., and Mitchell, S. (1993). Problem-based learning: A review of literature on its outcomes and implementation issues. Acad. Med. 68: 52-81.

Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 84: 261-271.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control , Freeman, New York.

Barron, B. J. S. (2002). Achieving coordination in collaborative problem-solving groups. J. Learn. Sci. 9: 403-437.

Barrows, H. S. (2000). Problem-Based Learning Applied to Medical Education , Southern Illinois University Press, Springfield.

Barrows, H., and Kelson, A. C. (1995). Problem-Based Learning in Secondary Education and the Problem-Based Learning Institute (Monograph 1), Problem-Based Learning Institute, Springfield, IL.

Barrows, H. S., and Tamblyn, R. (1980). Problem-Based Learning: An Approach to Medical Education , Springer, New York.

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. (1989). Intentional learning as a goal of instruction. In Resnick, L. B. (ed.), Knowing, Learning, and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 361-392.

Biggs, J. B. (1985). The role of metalearning in study processes. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 55: 185-212.

Blumberg, P., and Michael, J. A. (1992). Development of self-directed learning behaviors in a partially teacher-directed problem-based learning curriculum. Teach. Learn. Med. 4: 3-8.

Blumenfeld, P. C., Marx, R. W., Soloway, E., and Krajcik, J. S. (1996). Learning with peers: From small group cooperation to collaborative communities. Educ. Res. 25(8): 37-40.

Boud, D., and Feletti, G. (1991). The Challenge of Problem Based Learning , St. Martin's Press, New York.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., and Cocking, R. (2000). How People Learn , National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Bransford, J. D., and McCarrell, N. S. (1977). A sketch of a cognitive approach to comprehension: Some thoughts about understanding what it means to comprehend. In Johnson-Laird, P. N., and Wason, P. C. (eds.), Thinking: Readings in Cognitive Science , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 377-399.

Bransford, J. D., Vye, N., Kinzer, C., and Risko, R. (1990). Teaching thinking and content knowledge: Toward an integrated approach. In Jones, B. F., and Idol, L. (eds.), Dimensions of Thinking and Cognitive Instruction , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 381-413.

Bridges, E. M. (1992). Problem-Based Learning for Administrators , ERIC Clearinghouse on Educational Management, Eugene, OR.

Brown, A. L. (1995). The advancement of learning. Educ. Res. 23(8): 4-12.

Chi, M. T. H., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., and Glaser, R. (1989). Self-explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cogn. Sci. 13: 145-182.

Chi, M. T. H., DeLeeuw, N., Chiu, M., and LaVancher, C. (1994). Eliciting self-explanations improves understanding. Cogn. Sci. 18: 439-477.

Chi, M. T. H., Feltovich, P., and Glaser, R. (1981). Categorization and representation of physics problems by experts and novices. Cogn. Sci. 5: 121-152.

Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt (1997). The Jasper Project: Lessons in Curriculum, Instruction, Assessment, and Professional Development , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Cohen, E. G. (1994). Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for productive small groups. Rev. Educ. Res. 64: 1-35.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., and Newman, S. E. (1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching the crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In Resnick, L. B. (ed.), Knowing, Learning, and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 453-494.

DeGrave, W. S., Boshuizen, H. P. A., and Schmidt, H. G. (1996). Problem-based learning: Cognitive and metacognitive processes during problem analysis. Instr. Sci. 24: 321-341.

Derry, S. J., Lee, J., Kim, J.-B., Seymour, J., and Steinkuehler, C. A. (2001, April). From ambitious vision to partially satisfying reality: Community and collaboration in teacher education . Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Seattle, WA.

Derry, S. J., Levin, J. R., Osana, H. P., Jones, M. S., and Peterson, M. (2000). Fostering students' statistical and scientific thinking: Lessons learned from an innovative college course. Am. Educ. Res. J. 37: 747-773.

Derry, S. J., Siegel, M., Stampen, J., and the STEP team (2002). The STEP system for collaborative case-based teacher education: Design, evaluation, and future directions. In Stahl, G. (ed.), Proceedings of CSCL 2002 , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 209-216.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education , Macmillan, New York.

Dochy, F., Segers, M., Van den Bossche, P., and Gijbels, D. (2003). Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis. Learn. Instr. 13: 533-568.

Dods, R. F. (1997). An action research study of the effectiveness of problem-based learning in promoting the acquisition and retention of knowledge. J. Educ. Gifted 20: 423-437.

Dolmans, D. H. J. M., and Schmidt, H. G. (2000). What directs self-directed learning in a problem-based curriculum? In Evensen, D. H., and Hmelo, C. E. (eds.), Problem-Based Learning: A Research Perspective on Learning Interactions Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 251-262.

Duch, B. J., Groh, S. E., and Allen, D. E. (2001). The Power of Problem-Based Learning , Stylus, Steerling, VA.

Dweck, C. S. (1991). Self-theories and goals: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1990 , University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, pp. 199-235.

Ertmer, P., Newby, T. J., and MacDougall, M. (1996). Students' responses and approaches to case-based instruction: The role of reflective self-regulation. Am. Educ. Res. J. 33: 719-752.

Evensen, D. (2000). Observing self-directed learners in a problem-based learning context: Two case studies. In Evensen, D., and Hmelo, C. E. (eds.), Problem-Based Learning: A Research Perspective on Learning Interactions , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 263-298.

Evensen, D. H., Salisbury-Glennon, J., and Glenn, J. (2001). A qualitative study of 6 medical students in a problem-based curriculum: Towards a situated model of self-regulation. J. Educ. Psychol. 93: 659-676.

Faidley, J., Evensen, D. H., Salisbury-Glennon, J., Glenn, J., and Hmelo, C. E. (2000). How are we doing? Methods of assessing group processing in a problem-based learning context. In Evensen, D. H., and Hmelo, C. E. (eds.), Problem-Based Learning: A Research Perspective on Learning Interactions , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 109-135.

Ferrari, M., and Mahalingham, R. (1998). Personal cognitive development and its implications for teaching and learning. Educ. Psychol. 33: 35-44.

Gallagher, S., and Stepien, W. (1996). Content acquisition in problem-based learning: Depth versus breadth in American studies. J. Educ. Gifted 19: 257-275.

Gallagher, S. A., Stepien, W. J., and Rosenthal, H. (1992). The effects of problem-based learning on problem solving. Gifted Child Q. 36: 195-200.

Gick, M. L., and Holyoak, K. J. (1980). Analogical problem solving. Cogn. Psychol. 12: 306-355.

Gick, M. L., and Holyoak, K. J. (1983). Schema induction and analogical transfer. Cogn. Psychol. 15: 1-38.

Goodman, L. J., Erich, E., Brueschke, E. E., Bone, R. C., Rose, W. H., Williams, E. J., and Paul, H. A. (1991). An experiment in medical education: A critical analysis using traditional criteria. JAMA 265: 2373-2376.

Greeno, J. G., Collins, A., and Resnick, L. B. (1996). Cognition and learning. In Berliner, D. C., and Calfee, R. C. (eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology , Macmillan, New York, pp. 15-46.

Hmelo, C. E. (1994). Development of Independent Thinking and Learning Skills: A Study of Medical Problem-Solving and Problem-Based Learning , Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN.

Hmelo, C. E. (1998). Problem-based learning: Effects on the early acquisition of cognitive skill in medicine. J. Learn. Sci. 7: 173-208.

Hmelo, C. E., and Ferrari, M. (1997). The problem-based learning tutorial: Cultivating higher-order thinking skills. J. Educ. Gifted 20: 401-422.

Hmelo, C. E., Gotterer, G. S., and Bransford, J. D. (1997). A theory-driven approach to assessing the cognitive effects of PBL. Instr. Sci. 25: 387-408.

Hmelo, C. E., and Guzdial, M. (1996). Of black and glass boxes: Scaffolding for learning and doing. In Edelson, D. C., and Domeshek, E. A. (eds.), Proceedings of ICLS 96 , AACE, Charlottesville, VA, pp. 128-134.

Hmelo, C. E., Holton, D., and Kolodner, J. L. (2000). Designing to learn about complex systems. J. Learn. Sci. 9: 247-298.

Hmelo, C. E., and Lin, X. (2000). The development of self-directed learning strategies in problem-based learning. In Evensen, D., and Hmelo, C. E. (eds.), Problem-Based Learning: Research Perspectives on Learning Interactions , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 227-250.

Hmelo, C., Shikano, T., Bras, B., Mulholland, J., Realff, M., and Vanegas, J. (1995). A problem-based course in sustainable technology. In Budny, D., Herrick, R., Bjedov, G., and Perry, J. B. (eds.), Frontiers in Education 1995 , American Society for Engineering Education, Washington, DC.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2000). Knowledge recycling: Crisscrossing the landscape of educational psychology in a Problem-Based Learning Course for Preservice Teachers. J. Excell. Coll. Teach. 11: 41-56.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E. (2002). Collaborative ways of knowing: Issues in facilitation. In Stahl, G. (ed.), Proceedings of CSCL 2002 , Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 199-208.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E., and Barrows, H. S. (2003). Facilitating collaborative ways of knowing . Manuscript submitted for publication.

Hmelo-Silver, C. E., and Barrows, H.S. (2002, April). Goals and strategies of a constructivist teacher . Paper presented at American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA.

Kilpatrick, W. H. (1918). The project method. Teach. Coll. Rec. 19: 319-335.

Kilpatrick, W. H. (1921). Dangers and difficulties of the project method and how to overcome them: Introductory statement: Definition of terms. Teach. Coll. Rec. 22: 282-288.

Kolodner, J. L. (1993). Case-Based Reasoning , Morgan Kaufmann, San Mateo, CA.

Kolodner, J. L., Hmelo, C. E., and Narayanan, N. H. (1996). Problem-based learning meets case-based reasoning. In Edelson, D. C., and Domeshek, E. A. (eds.), Proceedings of ICLS 96 , AACE, Charlottesville, VA, pp. 188-195.

Koschmann, T. D., Myers, A. C., Feltovich, P. J., and Barrows, H. S. (1994). Using technology to assist in realizing effective learning and instruction: A principled approach to the use of computers in collaborative learning. J. Learn. Sci. 3: 225-262.

Krajcik, J., Blumenfeld, P., Marx, R., and Soloway, E. (2000). Instructional, curricular, and technological supports for inquiry in science classrooms. In Minstrell, J., and Van Zee, E. H. (eds.), Inquiring Into Inquiry Learning and Teaching in Science , American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, DC, pp. 283-315.

Krajcik, J., Marx, R., Blumenfeld, P., Soloway, E., and Fishman, B. (2000, April). Inquiry-based science supported by technology: Achievement among urban middle school students . Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

Lampert, M. (2001). Teaching Problems and the Problems of Teaching , Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Leontiev, A. N. (1978). Activity, Consciousness, and Personality (M. J. Hall, Trans.), Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Lesgold, A., Rubinson, H., Feltovich, P., Glaser, R., Klopfer, D., and Wang, Y. (1988). Expertise in a complex skill: Diagnosing x-ray pictures. In Chi, M. T. H., Glaser, R., and Farr, M. J. (eds.), The Nature of Expertise , Erlbaum. Hillsdale, NJ, pp. 311-342.

Linn, M. C., and Hsi, S. (2000). Computers, Teachers, Peers: Science Learning Partners , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ.

Mennin, S. P., Friedman, M., Skipper, B., Kalishman, S., and Snyder, J. (1993). Performances on the NBME I, II, and III by medical students in the problem-based and conventional tracks at the University of New Mexico. Acad. Med. 68: 616-624.

Needham, D. R., and Begg, I. M. (1991). Problem-oriented training promotes spontaneous analogical transfer. Memory-oriented training promotes memory for training. Mem. Cogn. 19: 543-557.

Norman, G. R., Brooks, L. R., Colle, C., and Hatala, H. (1998). Relative effectiveness of instruction in forward and backward reasoning . Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, San Diego, CA.

Norman, G. R., Trott, A. D., Brooks, L. R., and Smith, E. K. (1994). Cognitive differences in clinical reasoning related to postgraduate training. Teach. Learn. Med. 6: 114-120.

Novick, L. R., and Hmelo, C. E. (1994). Transferring symbolic representations across nonisomorphic problems. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 20: 1296-1321.

Novick, L. R., and Holyoak, K. J. (1991). Mathematical problem solving by analogy. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 17: 398-415.

O'Donnell, A. M. (1999). Structuring dyadic interaction through scripted cooperation. In O'Donnell, A. M., and King, A. (eds.), Cognitive Perspectives on Peer Learning , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 179-196.

Palincsar, A. S., and Herrenkohl, L. R. (1999). Designing collaborative contexts: Lessons from three research programs. In O'Donnell, A. M., and King, A. (eds.), Cognitive Perspectives on Peer Learning ,Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 151-178.

Patel, V. L., Groen, G. J., and Norman, G. R. (1991). Effects of conventional and problem-based medical curricula on problem solving. Acad. Med. 66: 380-389.

Patel, V. L., Groen, G. J., and Norman, G. R. (1993). Reasoning and instruction in medical curricula. Cogn. Instr. 10: 335-378.

Pea, R. D. (1993). Practices of distributed intelligence and designs for education. In Salomon, G., and Perkins, D. (eds.), Distributed Cognitions: Psychological and Educational Considerations , Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 47-87.

Perfetto, G. A., Bransford, J. D., and Franks, J. J. (1983). Constraints on access in a problem-solving context. Mem. Cogn. 11: 24-31.

Puntambekar, S., and Kolodner, J. L. (1998). The design diary: A tool to support students in learning science by design. In Bruckman, A. S., Guzdial, M., Kolodner, J., and Ram, A. (eds.), Proceedings of ICLS 98 , AACE, Charlottesville, VA, pp. 230-236.

Ram, P. (1999). Problem-based learning in undergraduate instruction: A sophomore chemistry laboratory. J. Chem. Educ. 76: 1122-1126.

Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to Teach in Higher Education , Routledge, New York.

Salomon, G. (1993). No distribution without individual cognition: A dynamic interactional view. In Salomon, G., and Perkins, D. (eds.), Distributed Cognitions: Psychological and Educational Considerations ,Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 111-138.

Salomon, G., and Perkins, D. N. (1989). Rocky roads to transfer: Rethinking mechanisms of a neglected phenomenon. Educ. Psychol. 24: 113-142.

Schmidt, H. G., DeVolder, M. L., De Grave, W. S., Moust, J. H. C., and Patel, V. L. (1989). Explanatory models in the processing of science text: The role of prior knowledge activation through small-group discussion. J. Educ. Psychol. 81: 610-619.

Schmidt, H. G., Machiels-Bongaerts, M., Hermans, H., ten Cate, T. J., Venekamp, R., and Boshuizen, H. P. A. (1996). The development of diagnostic competence: Comparison of a problem-based, an integrated, and a conventional medical curriculum. Acad. Med. 71: 658-664.

Schmidt, H. G., and Moust, J. H. C. (2000). Factors affecting small-group tutorial learning: A review of research. In Evensen, D., and Hmelo, C. E. (eds.), Problem-Based Learning: A Research Perspective on Learning Interactions , Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 19-51.

Schwartz, D. L., and Bransford, J. D. (1998). A time for telling. Cogn. Instr. 16: 475-522.

Schoenfeld, A. H. (1985). Mathematical Problem Solving , Academic Press, Orlando, FL.

Shikano, T., and Hmelo, C. E. (1996, April). Students' learning strategies in a problem-based curriculum for sustainable technology . Paper presented at American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, New York.

Steinkuehler, C. A., Derry, S. J., Hmelo-Silver, C. E., and DelMarcelle, M. (2002). Cracking the resource nut with distributed problem-based learning in secondary teacher education. J. Distance Educ. 23: 23-39.

Stepien, W. J., and Gallagher, S. A. (1993). Problem-based learning: As authentic as it gets. Educ. Leadersh. 50(7): 25-29.

Torp, L., and Sage, S. (2002). Problems as Possibilities: Problem-Based Learning for K-12 Education , 2nd edn., ASCD, Alexandria, VA.

Vernon, D. T., and Blake, R. L. (1993). Does problem-based learning work?: A meta-analysis of evaluative research. Acad. Med. 68: 550-563.

Vye, N. J., Goldman, S. R., Voss, J. F., Hmelo, C., and Williams, S. (1997). Complex math problem-solving by individuals and dyads: When and why are two heads better than one? Cogn. Instr. 15: 435-484.

Webb, N. M., and Palincsar, A. S. (1996). Group processes in the classroom. In Berliner, D., and Calfee, R. (eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology , MacMillan, New York, pp. 841-876.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity , Cambridge University Press, New York.

White, B. Y., and Frederiksen, J. R. (1998). Inquiry, modeling, and metacognition: Making science accessible to all students. Cogn. Instr. 16: 3-118.

Williams, S. M. (1992). Putting case based learning into context: Examples from legal, business, and medical education. J. Learn. Sci. 2: 367-427.

Williams, S. M., Bransford, J. D., Vye, N. J., Goldman, S. R., and Carlson, K. (1993). Positive and negative effects of specific knowledge on mathematical problem solving . Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA.

Zimmerman, B. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Pract . 41, 64-71.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Psychology, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, New Jersey

Cindy E. Hmelo-Silver

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cindy E. Hmelo-Silver .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hmelo-Silver, C.E. Problem-Based Learning: What and How Do Students Learn?. Educational Psychology Review 16 , 235–266 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3

Download citation

Issue Date : September 2004

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000034022.16470.f3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- problem-based learning

- constructivist learning environments

- learning processes

- problem solving

- self-directed learning

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered approach in which students learn about a subject by working in groups to solve an open-ended problem. This problem is what drives the motivation and the learning.

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a teaching method in which students learn about a subject through the experience of solving an open-ended problem found in trigger material. The PBL process does not focus on problem solving with a defined solution, but it allows for the development of other desirable skills and attributes.

National Science Foundation. Citations (82) References (91) Abstract. In this chapter, we describe different theoretical perspectives – information processing, social constructivism, and...

Problem-based learning. Learning processes. Small-group collaboration. Self-directed study. Effectiveness of learning. 1. Introduction. Problem-based learning (PBL) has been widely adopted in diverse fields and educational contexts to promote critical thinking and problem-solving in authentic learning situations.

What is Problem-Based Learning (PBL)? PBL is a student-centered approach to learning that involves groups of students working to solve a real-world problem, quite different from the direct teaching method of a teacher presenting facts and concepts about a specific subject to a classroom of students.

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered pedagogy based on the constructivist learning theory through collaboration and self-directed learning. With PBL, students create knowledge and comprehension of a subject through the experience of solving an open-ended problem without a defined solution.

Problem-based learning (PBL) is an instructional method aimed at preparing students for real-world settings. By requiring students to solve problems, PBL enhances students’ learning outcomes by promoting their abilities and skills in applying knowledge, solving problems, practicing higher order thinking, and self-directing their own learning.

Abstract. Problem-based approaches to learning have a long history of advocating experience-based education. Psychological research and theory suggests that by having students learn through the experience of solving problems, they can learn both content and thinking strategies.