You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- Our Organization

- Mission & Vision

- Clinical Philosophy

- Executive Leadership

- Division Leadership

- Board of Directors

- Employee Highlights

- Employee Honors

- Advisory Board

- Our History

- Statements of Support & Inclusion

- Compliance

- Accreditation

- Awards & Achievements

- A Lifetime of Firsts

- Faces, Voices and Lives at May

- Annual Report

- Our Affiliations

- About Training

- Internships & Fellowships

- About Research

- Institutional Review Board

- Opportunities for Educators

- Opportunities for Families

- Research Projects

- Publications

- Presentations & Posters

- A-May-zing Work!

- Job Opportunities

- Benefits

- Certification Programs

- Predoctoral Internship in School Psychology

- Doctoral Internship in Clinical Psychology

- Postdoctoral Fellowships

- Behavior Analysts at May

- Behavior Therapists at May

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Calendar of Events

- Newsroom

- Resources for Journalists

- Press Releases

- May in the News

- A Closer Look: Expert Columns

- Notice of Data Security Event

- Early Intervention

- Center-based Therapy

- In-Home Behavioral Services

- Home-based Services

- Family Support & Resources

- Residential Life

- Programs & Services

- Brain Injury & Neurobehavioral Disorders

- Community Involvement

- Our Stories

- Behavior Support

- Employment & Life Skills Training

- Student Council

- Rehabilitation

- Medical Care

- Transition to Adulthood

- After-school Activities

- Our Residences

- Counseling Support

- Family Support

- Calendar & Events

- Impact Briefs

- Presentations

- Questions & Answers

- School Consultation

- Training for Educators

- PBS for DDS-Funded Organizations

- Day Habilitation Programs

- Residential Services

- Employment and Supported Education

- Meaningful Jobs Initiative

- PBS Consultation for DDS-Funded Organizations

- Assistive Technology (AT)

- DDS Adult Services

- Consultation for Schools

- Trainings and Presentations

- National Autism Center

- Virtual Trainings

- Non-English Resources

- May in the news

- Media Releases

- Newsletters

Helping Adults with Intellectual Disabilities Develop Problem-solving Skills

Categories: ASD and DD, Adult-focused

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

UDS Foundation

A Guide to Basic Life Skills for Adults with Disabilities

December 21, 2021

Share this:

Life skills have a significant impact on our personal success, but learning and developing them can be especially difficult for people with disabilities. However, basic life skills for adults with disabilities are essential to living independently or fully participating in an assisted living community.

In this blog, we’ll review the most important life skills for adults with disabilities and provide helpful suggestions for how you can cultivate these crucial abilities.

Table of Contents

What are life skills for adults with disabilities.

Regardless of your ability level, life skills are the behavioral, intellectual, and interpersonal qualities necessary to live a productive, satisfying life. Also known as psychosocial skills, these traits fall into three main categories:

- Emotional skills : knowing who you are, handling emotions appropriately, and possessing self-awareness and empathy.

- Social skills : communicating effectively, developing healthy relationships, and successfully interacting with others.

- Thinking skills : developing multiple solutions for problems, remaining open to learning, and approaching topics creatively.

Ultimately, cultivating life skills for adults with disabilities can help you better connect with others while living a more productive and fulfilling life. Keep in mind that certain basic life skills for adults with disabilities may be more or less relevant depending on your specific age, location, or life stage.

Benefits of Building Life Skills for Adults with Disabilities

There are many benefits of developing life skills for adults with disabilities, which we’ll review in more detail below.

Improved Physical & Mental Health

Having basic life skills for adults with disabilities is proven to help you live a healthier life and make better choices. Life skills also allow you to develop self-confidence and personal worth, along with making it easier to deal with significant life changes. This can help reduce feelings of aggression and anger because you’ll have a clear head and an improved ability to analyze difficult situations.

Stronger Relationships

Developing life skills for adults with learning disabilities and physical challenges also makes it easier to form fulfilling relationships , which are proven to make you healthier and happier. Plus, you’ll have the opportunity to positively impact the lives of others while gaining valuable relationship skills.

Live More Independently

Perhaps most importantly, building life skills for adults with disabilities significantly improves your chances of living independently in the comfort of your own home. Depending on your ability level, life skills can also make it easier to maintain employment and manage your finances. You may also be able to complete more of your personal needs without help and rely less on government assistance.

Community Integration

Finally, developing basic life skills for adults with disabilities can help you smoothly assimilate into your community. People with disabilities are often isolated from their non-disabled peers, making it much harder to fully participate in life at the same level as everyone else. As a result, you may miss out on educational opportunities, housing, healthcare, employment, valued social roles, and more.

UDS Can Help You Live A Fuller Life With Our Comprehensive Services:

Planning & Suppor t – Our dedicated planning & support teams help manage the care and services you need.

Personal Care & Independence – We’ve helped people with disabilities live more independently in their own homes since 1965.

Enrichment & Life Skills – Our variety of programs is dedicated to building skills for living well with a disability.

Interpersonal Life Skills Checklist for Adults with Disabilities

If you’re looking to develop your grasp on life skills for adults with developmental disabilities and physical challenges, consider starting with the interpersonal qualities below.

Communication Skills

The ability to achieve specific goals via communication (e.g. informing, persuading, or asserting a position) is an essential interpersonal life skill. This category includes both verbal and nonverbal communication, along with tone of voice, body language, and actively listening to those around you. You can improve your communication skills by using short sentences, common words, active voice, and second-person pronouns.

Creative Thinking Skills

Creative thinking means finding new solutions to problems by redefining them, incorporating relevant information, and being open to a variety of answers. Focusing on fluency (relevant ideas), originality (rare ideas), and elaboration (building on existing ideas) can greatly improve your creative thinking skills.

Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinking requires reflective thought processes that are centered on deciding what to believe or which actions to take. It involves organizing facts, interrogating ideas, and impartially evaluating arguments, which allows you to make the best judgments based on your situation and take action accordingly.

Decision-Making & Problem-Solving Skills

Put simply, decision-making is the process of identifying options and selecting the best one based on your values, beliefs, and goals. Effective decision-making requires you to define the problem, determine the requirements of an effective solution, establish the decision’s goals, and make a choice.

Closely related to decision-making, problem-solving involves using self-determination to apply your relevant knowledge and overall understanding to succeed in a difficult or unfamiliar situation.

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence is an extremely important life skill that requires the ability to understand and sympathize with another person’s feelings. Empathy is a key aspect of emotional intelligence, as it helps you put yourself in someone else’s shoes, allowing you to see situations from their perspective. Developing emotional intelligence requires a low fear of rejection, the ability to adapt to a variety of social settings, acceptance of others, and emotional self-awareness.

Mental Resilience & Coping Skills

The ability to cope with your emotions (especially when it comes to challenging situations) positively impacts both your well-being and relationships with others. Treat disappointing outcomes as opportunities for growth, and maintain resilience in the face of stress and discomfort.

Healthy coping skills include maintaining a positive mindset, unwavering optimism, the ability to generate beneficial emotions, and knowing how to express your feelings in a productive manner.

Self-Awareness

Another important interpersonal life skill for adults with disabilities is an awareness of how others perceive you. Practice frequent reflection and introspection, along with mindfully considering the actions you take and why you are the way you are. At the same time, avoid self-deprecating thoughts by focusing on your worth, acknowledging your strengths, remaining self-compassionate, and minimizing regret.

Other Important Life Skills for Adults with Disabilities

Interpersonal traits aren’t the only basic life skills for adults with disabilities that are essential to a fulfilling existence. We’ll review a few more important competencies below to help you get started.

Exercise & Physical Fitness

- Lowers your risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and obesity

- Improves physical strength and boosts energy for a longer life

- Builds confidence and improves body image

- Strengthens focus and stimulates brain activity

Home Management

- Basic housekeeping (e.g. laundry, cleaning, and pet care)

- Money management skills (e.g. budgeting, saving, and getting out of debt)

- Emergency preparedness and basic first aid

- Regular vehicle maintenance (e.g. inspections and oil changes)

- Grocery shopping, meal planning/preparation, and cooking

- Boosts energy levels and helps you maintain a healthy weight

- Reduces your risk of some illnesses and diseases later on in life

Personal Hygiene

- Bathing/showering, brushing your teeth, and using deodorant daily

- Builds self-confidence and makes you more approachable

- May help you make new friends or secure a job interview

How Do Adults Learn Life Skills with Disabilities?

There are a variety of methods that adults with disabilities can use to cultivate the skills they need to succeed in their daily lives. Physical life skills are often developed through physical therapy, while self-care, eating, and writing may require an occupational therapy setting.

Here are a few other ways you can build life skills for adults with disabilities on your own:

- Shadowing another person as they perform tasks

- Reviewing a photo sequence of a task with written steps

- Examining a task in the place where it usually takes place

- Breaking tasks into small steps and learning them one at a time

- Backward chaining

- Loving-kindness meditation

- A gratitude journal

- Positive affirmations

Life Skills Services from UDS

If you need assistance with basic life skills for adults with disabilities, United Disabilities Services is here for you. Here are three ways that we can help you develop stronger life skills.

Adult Enrichment Program

Our Adult Enrichment day programs answer the question, “how to teach life skills to adults with disabilities” by providing the opportunity to socialize, learn, and share your talents. In turn, you’ll gain valuable life skills as you explore your community with friends.

Adult Enrichment is available to anyone with a physical or intellectual disability between the ages of 18-59. Your costs may be covered through government-funded waiver sources , and you can also pay privately.

UDS Employment Services Program

The UDS Employment Services program matches qualified applicants with employers that are looking for full- and part-time employees. Our employment counselors work with you one-on-one throughout the application process, along with on-the-job coaching once you begin working.

Many participants qualify for government assistance and are referred through the Pennsylvania Office of Vocational Rehabilitation (OVR). Anyone referred by the OVR is eligible for vocational services at no additional cost.

UDS Transition School

Designed for high school juniors and seniors, our Transition School will help you prepare for independent life after graduation. Our instructors work with small groups one-on-one and focus on each person’s area of specific need. You’ll attend classes one day a week and will receive school credit for your participation. Enrollment is free for students who meet scholarship qualifications.

Ready to start building basic life skills for adults with disabilities that will help you live a better life? Visit our Resource Center or contact us to learn more about our services and any financial assistance you may qualify for.

United disabilities services, resource center.

ADA Policy | Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Sitemap | Contact Us

© 2021 United Disabilities Services. All Rights Reserved.

Connect With Us

Your help is vital in ensuring that we continue to fulfill our mission of exceptional care.

Individuals with I/DD: Building Skills and Independence on a Meaningful Journey

Mar 24, 2022

Living with I/DD can pose definite challenges to developing independent living skills that many people take for granted. For adults with I/DD, learning to perform these everyday tasks is essential to gaining more self-sufficiency in their daily lives. Many skills are taught with patience, simple direction, and repetition by a family member or a qualified clinician such as an occupational therapist. Other adults may require their environment being altered to accommodate their special needs to learn a specific skill more easily.

Teaching may be focused on maximizing independence to their most functional level or for an individual to live safely on their own. The primary goal is to ensure that these individuals are encouraged through respect and positive reinforcement to develop the basic skills needed for work, play, and daily living. By gaining more independence, adults with I/DD can realize a happier, more meaningful life filled with a greater sense of awareness and purpose.

What Are Independent and Functional Living Skills?

The ability to learn depends greatly on the level of disability. Skill-building comprises a roster of tasks that start with individuals becoming conscious of themselves as an entity, requiring daily maintenance of personal hygiene and grooming, and taking care of their general health and nutrition.

Adults with I/DD may also be taught to manage their home environment, personal safety, and understand basic finances. Individuals also learn:

- Pre-vocational skills that aid in potential volunteer and job opportunities

- Interactive recreational skills through puzzles and other tabletop activities

- Functional math and reading skills for shopping, cooking, or other activities

Individuals are able to develop an awareness of their surroundings and more constructive problem-solving. Many adults with I/DD are able to connect more with their communities, navigate transit and gain employment.

Strategies For Encouraging Independence

Helping an adult with I/DD to become more independent can often be challenging. . However,the following strategies can help caregivers ensure that individuals successfully reach their goals:

Avoid Micromanaging

Rather than hold on too tightly, let the adult take responsibility for their thoughts, ideas, and goals. Stepping back allows them to step forward.

Develop a Strong Support Team

A trusted team of professionals and family members working with an individual with I/DD provides a strong support network for both recipient and caregivers, supplying knowledge, strengths, and additional security and stability.

Learn From Their Perspective

Remember that your perspective will differ from an individual’s experiences and feelings. Put yourself in their shoes for a moment to understand why they feel as they do.

Patience and Respect

Learning new skills is life-changing and will take time and patience. Each small step forward to us is a huge step for an adult with I/DD. Respect their boundaries and their choices while acknowledging their triumphs. Fear and anxiety can discourage someone with I/DD, so keeping their spirits up is essential for continued growth.

Learning independent and functional living skills is a lifelong journey for people with I/DD. New York’s Independent Living Association (ILA) provides continuous support for Individuals through exceptional programs and services that help them thrive in their communities.

For more information on ILA’s array of services, visit ilaonline.org/services. Increased confidence, enhanced social interaction, and broader community integration for Individuals await!

Recent Posts

Enriching lives through therapeutic recreation: a guide for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (i/dd), coping with allergies tips for caregivers of individuals with i/dd.

Learn how to effectively manage allergies in individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). Our helpful guide covers how to recognize allergy symptoms, ways to manage and assist, preventive measures to take, and the importance of communication in providing the best care. Make allergy season more comfortable with informed and collaborative care.

A New Frontier in the Care of Aging Adult Individuals with I/DD

Savoring summer safely: a guide for individuals with i/dd and their caregivers.

Discover crucial summer heat health safety tips tailored for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and learn how caregivers can provide essential support.

Why Behavioral Health Management is Essential for Individuals with I/DD

Caring for the unique needs of i/dd patients: celebrating this specialty area of nursing during national nurses month, 15th annual golf tournament, friday, september 16, 2022 10:30 am - 8:30 pm.

Join us at Harbor Links for our annual fundraiser to support ILA’s programs and services for intellectually and developmentally disabled Individuals.

Register here to make a difference and help us recognize the everyday heroes who continue to make an impact in the lives of others.

For more information, please visit our 2022 Golf Event page here .

What Goes Into Maintaining an ILA Residence? Great Staff, Tech Support, and Lots of Teamwork!

By Kelly Kass, Contributing Writer

For ILA’s residences to operate smoothly, there are many moving parts.

Direct Support Professionals (DSPs) provide nurturing care to ILA’s Individuals and cooks prepare healthy meals for Individuals to enjoy. Nurses, Behavior Intervention Specialists and other clinicians visit residences to provide clinical support, and ILA’s Quality Assurance and Compliance teams always ensure that the Agency meets all city, state, and federal regulations. Whether staff are on the front lines or behind-the-scenes, it truly is a collaborative effort to keep residences running smoothly.

ILA security camera footage

For Area Coordinator Omar James, maintaining sufficient staffing is the key to ILA’s residences operating successfully. “Providing the necessary amount of staff has been crucial to ensure that our Individuals continue to receive high quality care, especially during the pandemic,” he points out.

Omar proudly recalls the way residences banded together during the dark and uncertain time. “Managers stepped into direct care roles while overseeing the daily operations of their houses,” he explains. “Their excellent leadership set the precedent – it didn’t matter if you were a supervisor or a coordinator, it was all hands on deck because we’re all DSPs at heart. Individuals’ safety will always be our top priority,” Omar says.

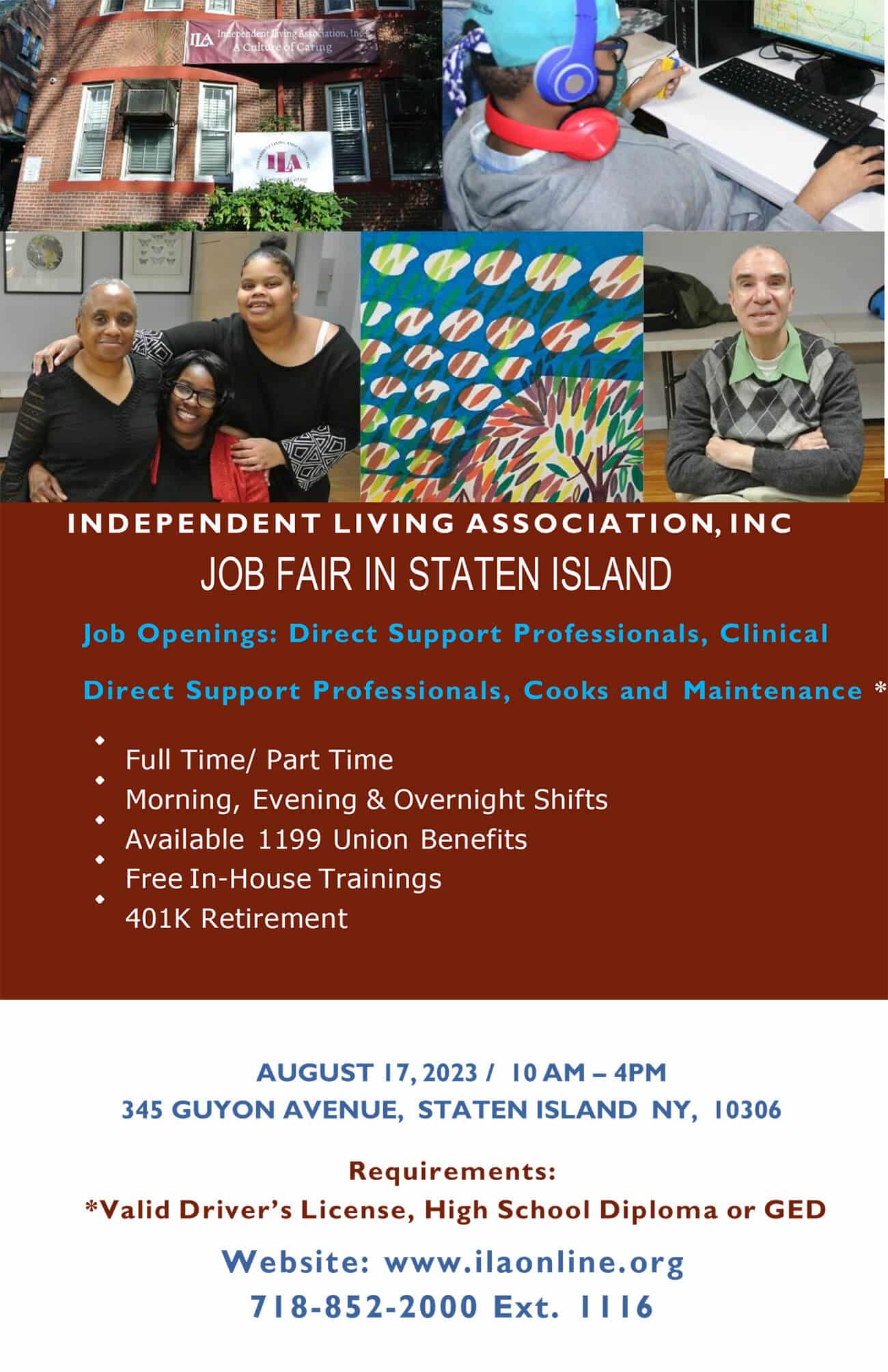

Omar credits ILA’s Human Resources Department for a stellar recruitment effort, which has helped to combat recent staffing shortages. “Holding job fairs and promoting them on social media has been a great way to attract and hire more permanent staff, lessening the need to use a temp agency,” Omar points out.

ILA’s Maintenance staff also play an important role around the residences. “We work with Maintenance (as well as families) to make sure our houses are personalized and tailored to Individuals’ liking while meeting every safety requirement,” Omar points out.

When it comes to change of seasons, Area Coordinators, Supervisors, and Maintenance teams are fully prepared for the transition. Boilers and snow plows are inspected before winter hits. Driveways and sidewalks are regularly cleared of any snow or ice.

ILA staff (and residents!) prep gazebos and backyards for spring and summer fun! DSPs also work together to make sure changeover clothing is always in place so Individuals can dress appropriately for each season.

Staff and Individuals watering the Garnet Street Garden.

Community Outings

With the arrival of spring and summer, recreational outings are in full swing at ILA. Residence staff distribute funds to Individuals so they can enjoy community inclusion activities, such as trips to local restaurants and shopping centers. Staff also make sure that houses are equipped with hand-held food processors so DSPs can puree food for Individuals while they’re dining out in the community. “Our staff are trained to ensure restaurants can serve appropriately; that way, all Individuals can dine safely and feel included no matter what their dietary needs are,” Omar says.

Whatever the activity, whatever the task, one thing is certain – teamwork is essential. “At ILA, it’s a group effort,” Omar explains. “We all work proactively to make things happen and keep our residences running.”

If there’s a holiday taking place, you can be sure our Brooklyn Day Hab will celebrate! For Valentine’s Day, the program held a fun-filled party to spread the love. Individuals helped staff prepare the fabulous decorations, turning the space into a blissful sea of red and pink! The delicious cuisine featured jerk chicken, rice and peas, curried goat, fried chicken, salad, and Rasta Pasta. For dessert: heart-shaped cupcakes, of course!

“Individuals had a wonderful time,” says Keicha Goulbourne, Supervisor, Brooklyn Day Hab. “The love was definitely flowing!”

According to Keicha, Individuals often ask for parties at the program and they particularly like dressing up. On St. Patrick’s Day, they had their chance, as many Individuals donned their best green attire to celebrate! Sparkling shamrocks, colorful backdrops, and festive balloons were among the beautiful decorations as Individuals and staff enjoyed tasty food and wonderful camaraderie. Irish eyes were definitely smiling on Brooklyn Day Hab!

For July 4th, Brooklyn Day Hab celebrated with stars and stripes and a festive lunch, as everyone proudly commemorated Independence Day!

Maintaining high standards of care is crucial in the world of residential services for individuals with intellectual and/or developmental disabilities (I/DD). ILA recently achieved a perfect audit score for its Fort Hamilton Residence.

This accomplishment is a testament to ILA's dedication to safety and and high quality care. In this article, we will explore the tips and strategies used by ILA's staff to achieve success, offering insights into how other organizations can maintain the highest standards of care.

What is an Audit, and How Does it Work?

Audits are conducted by the Office for People With Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) to evaluate an agency's compliance with regulations and guidelines. The audit is scored according to how many deficiencies an agency has.

According to ILA Area Coordinator Nikiesha Bucknor, auditors can show up at any time so it’s important to always collaborate with your staff to ensure you are meeting all of your marks.

“ ILA standards are extremely high. What we are required to do is tremendous. We have to support each other to ensure the Agency meets its mission of providing the highest quality care to Individuals. ”

-Shenee Briggs, ILA Area Coordinator

Celebrating success.

When a residence achieves a successful audit, ILA recognizes the hard work and dedication of staff by organizing a special staff meeting with food and refreshments. And you can definitely expect a glowing email to be distributed Agency-wide, which is what Nikiesha proudly did to announce Fort Hamilton’s perfect audit. “Having worked at ILA since 2007, I’ve seen many perfect scores, and I’m sure I’ll see many more at the Agency, thanks to our outstanding employees. Congratulations to Shante, Shenee, Assistant Supervisor Tiffany Pugh, and the entire Fort Hamilton team on their excellent achievement!”

Staff Watch: Dvorah Martin, Speech Services Coordinator

For 30 years, Dvorah Martin has been an integral part of ILA’s mission to enhance the lives of Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. She joined the Agency as a speech and language consultant before being hired full-time to oversee ILA’s Speech Services.

A licensed speech and hearing educator, Dvorah currently supervises ILA’s in-house speech pathologists as she coordinates speech services at all Agency sites. She also works closely with outside clinicians in Brooklyn and Staten Island to conduct evaluations and ensure Individuals’ needs are always met.

You’ll often find Dvorah on the phone acting as a liaison between ILA staff and area clinics, especially when it comes to managing an Individual’s dysphagia, a swallowing disorder that frequently impacts older developmentally disabled adults.

“I translate the clinical results into terms that explain what is required for staff at the house levels, so we can do everything we can to keep Individuals safe,” she explains. She also serves as the Designated Chairperson of ILA’s Choking Task Force, which meets regularly to ensure ILA is implementing Agency-wide safe practices.

Dvorah conducts regular trainings with Residence Supervisors, Direct Support Professionals (DSPs), and cooking staff to prevent choking incidents. Individualized placemats are designed identifying people’s prescribed consistency so meals can be safely prepared in accordance with a person’s diet.

Training staff is one of the many aspects of her job that Dvorah enjoys. “I love the collaboration that it entails. Staff are eager to learn critical practices that help them do their jobs well and keep Individuals safe,” she says.

Precision and Efficiency

Dvorah is also the go-to person when it comes to helping staff navigate PrecisionCare, the system used to store Individuals’ electronic health care records. The program is also used for billing and for Res Hab, Day Hab, and Com Hab documentation.

“Different team members have different functions in PrecisionCare. As Systems Administrator, I’m responsible for making sure staff are trained on the system and that they continue to have access,” Dvorah explains. If staff are accidentally locked out of PrecisionCare, Dvorah is always available to help them troubleshoot.

“It’s a very work intensive role, but I like working!” Dvorah says. She jokes that it’s the “geek” in her that enjoys being a Systems Administrator. “I like the efficiency of accessing our documentation from our electronic system,” Dvorah explains. “We’ve come a long way from the time records were paper-based. Thanks to advances in technology, we can streamline our habilitation services documentation and clinical documentation cleanly and efficiently so the Agency can operate successfully. And it’s great for audits,” she points out.

A Natural-Born Teacher

Training staff in PrecisionCare and dysphagia management comes naturally for Dvorah. Before she worked at ILA, she was a speech teacher for the New York City Board of Education for ten years. Dvorah taught a special education class to children, ages four through eight. “I taught the students daily living skills so they could become more independent,” Dvorah recalls. A significant goal was weaning them off the bottle and teaching them how to eat safely. “I was never the classic speech teacher,” Dvorah points out.

You might say working with the developmental disabled population is in her blood. In addition to her roles with ILA and the New York City Board of Education, Dvorah was a teaching assistant at United Cerebral Palsy (UCP) working at a program that was once under the auspices of the Willowbrook State School. “I really like helping people,” she says proudly.

Dvorah also enjoys helping at ILA events. She’s been a member of the Agency’s Golf Outing Committee for 16 years and is responsible for assembling the magnificent gift baskets that many raffle players have won.

Be Kind, Be Flexible

Kindness and empathy are always welcome no matter what the setting. Exuding positivity and light will help to lift people’s spirits and instill good feelings that will carry through their day. Life is not always easy for people with disabilities, so the smallest gestures of kindness can go a long way and can be highly beneficial to your happiness as well .

At ILA, we envision a world where everyone has equal opportunities to lead fulfilling lives. Together, let’s do what we can to make sure that always remains true for people with disabilities.

With Support and Encouragement, The Sky’s The Limit For People With Develomental Disabilities

At ILA, helping Individuals with intellectual and develomental disabilities (I/DD) reach their full potential in life is at the heart of our mission. Our highly trained, dedicated staff take pride in enhancing the independence of our Individuals, providing support and encouragement that enables Individuals to thrive.

Support for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities can come in many forms. Fostering self-sufficiency is at the top of the list. This includes providing creative opportunities and enriching activities, such as the ones offered in our day habilitation programs. Recreational outings are also a great way to foster inclusion, offering additional opportunities for Individuals to interact with members of the community. With the right supports in place, Individuals can build a strong foundation of self-confidence as they learn and navigate daily living skills to help them reach their goals.

Encouragement

The power of praise and uplifting words should not be underestimated. With continuous encouragement, Individuals will find the strength and determination to believe in themselves and forge a positive path towards success. Advocacy also plays a significant role, something ILA’s Direct Support Professionals (DSPs) provide on a regular basis. Bush Avenue Clinical DSP Tomeka Bullock explains, “I’ve had the opportunity to help Individuals become more verbal and communicate their likes and dislikes. They’re able to make choices for themselves and explore their self-identity.”

During medical appointments, Tomeka provides an extra layer of comfort and encouragement to Individuals to erase any fears they may have. “I tell them it’ll be okay as long as we go through it together,” Tomeka says.

Accompanying Individuals to doctor’s appointments and overseeing medication management are among the important factors that help Individuals maintain good health. Staff also ensure that all of their dietary needs are met.

Reach for the Sky

Having good health, support, and encouragement can equip people with disabilities with the tools they need to break through barriers and rise to great heights.

The sky truly is the limit to what they can achieve, as demonstrated by many of our Individuals , as well as successful authors, actors, producers, and more, who are raising awareness about all that is possible for people with disabilities.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Temple Grandin

Celebrated author and speaker Temple Grandin is a professor of Animal Science at Colorado State University. Her experience growing up with autism has paved the way for better understanding about autism and the importance of cultivating skills to build self-esteem and responsibility. “The skills that people with autism bring to the table should be nurtured for their benefit and society’s,” Grandin points out.

Source: IMDb

Geri Jewell

Geri Jewell , best known for her role on “The Facts of Life,” was the first person with a disability to be cast in a primetime series. She has appeared on numerous programs and is a successful author, stand-up comedian, and motivational speaker.

Source: Wikipedia

Thirty-year-old actor RJ Mitte is perhaps most famous for his role as Walter White, Jr. in the hit television show “Breaking Bad”. Mitte has cerebral palsy and grew up using crutches and wearing leg braces. He was eventually able to walk without them, thanks to exercising regularly and playing sports. He chose to use crutches in “Breaking Bad” to make the show more inclusive and to raise awareness about disabilities.

Source: Pageant Planet

Abbey Curran

In 2008 at age 20, Abbey Nicole Curran , who was born with cerebral palsy, became the first contestant in the Miss USA pageant to have a disability. Later, she started her own pageant for girls and women with special needs.

Source: respectability.org

Diana Elizabeth Jordan

A writer, director, producer, and actress, Diana Elizabeth Jordan is one of the most inspiring Black women working in Hollywood today. Rather than let her cerebral palsy stop her, she propelled herself to achieve a fulfilling career in the film industry with, in her words, “hard work and determination.”

Chris Burke

Chris Burke starred on the popular show, “Life Goes On” and appeared in “Mona Lisa Smile” and other well-known movies. He now works for the National Down Syndrome Society and is a staunch advocate for individuals with disabilities, reminding people that “it’s not our disabilities, it’s our abilities that count.”

We couldn’t agree more, Chris!

Find out more about Chris Burke on IMDb.

Job Fair Details

- Questions? Start Here

- Self-Determination ,

- Neurodiversity

Independent Life Skills for Adults with Developmental Disabilities

Every action and decision we make each day is rooted in a skill. In fact, you’re probably much more skilled than you give yourself credit for. Typing, reading, comprehension – these are just a few examples of basic life skills you likely use to explore the world around you.

Adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) can utilize life skills to bolster their independence. For many in the disability community, life skills can be challenging to navigate. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

What Are Life Skills? Why Do They Matter?

A life skill can be any skill an individual needs to participate in everyday life. When we talk about life skills for adults with IDD, though, we’re primarily focusing on core life skills . These relate specifically to how individuals think, learn, and care for themselves daily.

Everyone needs life skills. But for adults with IDD, life skills can represent a lot more than being able to care for oneself. They can inspire confidence, enable individuality, and ensure individuals lead the lives they aspire to.

Key Independent Life Skills for Adults with Disabilities

More potential life skills are out there than we could list at once. Still, some independent life skills stand out as key parts of an adult lifestyle. These core skills can help adults with disabilities advocate for themselves and engage with others.

The ultimate goal is to put as much power in the hands of the individual in question as possible as they navigate daily life.

Communication

Forming social bonds, expressing thoughts and feelings, and sharing experiences are just a few examples of communication skills. What communication looks like can vary. It might be written, verbal, or even portrayed through images, gestures, and eye contact.

Communication is crucial for self-advocacy and self-care. Finding support and reaching out to others is a core part of independent life for many adults with disabilities.

This skill involves understanding safety precautions and knowing how to respond when safety risks emerge. Emergencies aren’t the only contexts where safety is important, though. Something as simple as safely crossing the street can fall into this category.

Problem-Solving

When things don’t go as planned, or obstacles arise, it’s important to feel able to respond. Problem-solving skills often stem from a knowledge of what other resources and solutions are available. They also require a willingness or ability to try new things and take risks.

Transportation

Navigating the world with ease is something many of us take for granted. Understanding transportation options is an essential life skill – it helps adults access the care and resources they need. It also enables adults to hold steady jobs, visit loved ones, and more.

Personal Care: Hygiene, Cooking, etc.

Caring for oneself is arguably the most fundamental life skill, but it comprises many smaller sub-skills. Shopping, budgeting, cooking, cleaning, and more can all impact how fully an individual can tackle personal care.

Tips for Building the Life Skills You Need

Just like learning to tie your shoe or ride a bike, independent life skills take time and patience to develop. But that doesn’t mean you can’t do anything to help make things easier for yourself or a loved one.

- Practice, practice, practice. As you target a specific life skill, practice will be your best friend. Try, try, try again until things become a little less challenging – sometimes, getting over that initial hump is the hardest part.

- Set clear, specific goals. Know what your goals are and take time to define them. Trying to do too much at once is almost always a recipe for stress.

- Break it down. If one particular goal seems too daunting, try breaking it down. Want to work on financial independence? Start small by managing a regular allowance, then branch out into bigger topics like opening bank accounts.

Use assistive tools and technology. Assistive technologies exist to make life easier. Take advantage of them whenever possible.

Below are some resources you can use to get started on life skill practice and development.

- The ARC Center for Future Planning : Growing a Strong Social Network (PDF)

A document designed to help adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities grow their social skills and form new relationships.

- Casey Family Programs : Life Skills Guidebook (PDF)

A comprehensive resource on identifying and building life skills for adults with disabilities and their families.

- Learning Works for Kids: Choiceworks (Mobile App)

An app for tablets and mobile devices designed to help users visualize and complete daily routines or tasks. While the app is aimed at children with developmental disabilities, its features may still be useful for adults who enjoy using tech as part of their routine.

- California’s Self-Determination Program (SDP)

A program created by the State of California to connect individuals with disabilities with the resources, services, and support they deserve.

At NeuroNav, we’re here to help you navigate SDP and other disability resources so that you can pursue your goals. Learn more about our services or schedule a free consultation with our team to discover more options for support.

Related Articles

Dive into more topics and stories that resonate with your interests. Our handpicked articles offer a deeper look into the world of Self-Determination and beyond.

Overcoming Social Challenges & Finding Relationships with Disabilities

What Is a Sensory Processing Disorder?

How Disabilities and Mental Health Needs Can Overlap

Ready to navigate life with us.

Embark on your Self-Determination journey with confidence. Request your free consultation with NeuroNav and discover the personalized support waiting for you.

Interested in More Insights?

Stay in the loop with the latest from our blog. Sign up now and never miss out on empowering stories, tips, and updates.

Teaching Life Skills in Adults with Developmental Disabilities

by BBR | Aug 30, 2022 | Careers | 0 comments

Related: View our Community Group Home Services

3. Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving Life Skills

Related: View Our Employment Programs

4. Independent Living Life Skills

Related : View our In-Home Care Services

Related: View our Day Program Services

2. Social Life Skills

Life skills — what they are, important life skills for adults with developmental disabilities, 1. emotional life skills.

Center for Teaching

Teaching students with disabilities, there is a newer version of this teaching guide., visit creating accessible learning environments for the most recent guide on the topic., students of all abilities and backgrounds want classrooms that are inclusive and convey respect. for those students with disabilities, the classroom setting may present certain challenges that need accommodation and consideration..

Terminology | Types of Disabilities | Access to Resources | Confidentiality and Disclosure | Inclusive Design | Learn More | References

Terminology

In order to create an inclusive classroom where all students are respected, it is important to use language that prioritizes the student over his or her disability. Disability labels can be stigmatizing and perpetuate false stereotypes where students who are disabled are not as capable as their peers. In general, it is appropriate to reference the disability only when it is pertinent to the situation. For instance, it is better to say “The student, who has a disability” rather than “The disabled student” because it places the importance on the student, rather than on the fact that the student has a disability.

For more information on terminology, see the guide provided by the National Center on Disability and Journalism: http://ncdj.org/style-guide/

Types of Disabilities

Disabilities can be temporary (such as a broken arm), relapsing and remitting, or long-term. Types of disabilities may include:

- Hearing loss

- Low vision or blindness

- Learning disabilities, such as Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, dyslexia, or dyscalculia

- Mobility disabilities

- Chronic health disorders, such as epilepsy, Crohn’s disease, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, migraine headaches, or multiple sclerosis

- Psychological or psychiatric disabilities, such as mood, anxiety and depressive disorders, or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Asperger’s disorder and other Autism spectrum disorders

- Traumatic Brain Injury

Students may have disabilities that are more or less apparent. For instance, you may not know that a student has epilepsy or a chronic pain disorder unless she chooses to disclose or an incident arises. These “hidden” disorders can be hard for students to disclose because many people assume they are healthy because “they look fine.” In some cases, the student may make a seemingly strange request or action that is disability-related. For example, if you ask the students to rearrange the desks, a student may not help because he has a torn ligament or a relapsing and remitting condition like Multiple Sclerosis. Or, a student may ask to record lectures because she has dyslexia and it takes longer to transcribe the lectures.

Access to Resources

When students enter the university setting, they are responsible for requesting accommodations through the appropriate office. This may be the first time the student will have had to advocate for himself. For first year students, this may be a different process than what they experienced in high school with an Individualized Education Program (IEP) or Section 504 plan. The U.S. Department of Education has a pamphlet discussing rights and responsibilities for students entering postsecondary education: http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS74685

Every university has its own process for filing paperwork and the type of paperwork needed. At Vanderbilt, students must request accommodations through the Equal Opportunity, Affirmative Action, and Disability Services Department (EAD) [ http://www.vanderbilt.edu/ead/ ]. As part of the required paperwork, the student must present documentation from an appropriate medical professional indicating the diagnosis of the current disability and, among other things, the types of accommodations requested. All medical information provided is kept confidential. Only the approved accommodation arrangements are discussed with faculty and administrators on an as-needed basis.

It is important to note that this process takes time and certain accommodations, like an interpreter, must be made within a certain time period.

Confidentiality, Stigma, and Disclosure

A student’s disclosure of a disability is always voluntary. However, students with disabilities may feel nervous to disclose sensitive medical information to an instructor. Often, students must combat negative stereotypes about their disabilities held by others and even themselves. For instance, a recent study by May & Stone (2010) on disability stereotypes found that undergraduates with and without learning disabilities rated individuals with learning disabilities as being less able to learn or of lower ability than students without those disabilities. In fact, students with learning disabilities are no less able than any other student; they simply receive, process, store, and/or respond to information differently (National Center for Learning Disabilities).

Similarly students with physical disabilities face damaging and incorrect stereotypes, such as that those who use a wheelchair must also have a mental disability. (Scorgie, K., Kildal, L., & Wilgosh, L., 2010) Additionally, those students with “hidden disabilities” like epilepsy or chronic pain frequently describe awkward situations in which others minimize their disability with phrases like “Well, you look fine.” (Scorgie, K., Kildal, L., & Wilgosh, L., 2010)

In Barbara Davis’s Tools for Teaching , she explains that it is important for instructors to “become aware of any biases and stereotypes [they] may have absorbed….Your attitudes and values not only influence the attitudes and values of your students, but they can affect the way you teach, particularly your assumptions about students…which can lead to unequal learning outcomes for those in your classes.” (Davis, 2010, p. 58) As a way to combat these issues, she advises that instructors treat each student as an individual and recognize the complexity of diversity.

- A statement in your syllabus inviting students with disabilities to meet with you privately is a good step in starting a conversation with those students who need accommodations and feel comfortable approaching you about their needs. Let the student know times s/he can meet you to discuss the accommodations and how soon the student should do so. Here are two sample statements:

The Department of Spanish and Portuguese is committed to making educational opportunities available to all students. In order for its faculty members to properly address the needs of students who have disabilities, it is necessary that those students approach their instructors as soon as the semester starts, preferably on the first day of class. They should bring an official letter from the Opportunity Development Center (2-4705) explaining their specific needs so that their instructors are aware of them early on and can make the appropriate arrangements. If you have a learning or physical disability, or if you learn best utilizing a particular method, please discuss with me how I can best accommodate your learning needs. I am committed to creating an effective learning environment for all learning styles. However, I can only do this successfully if you discuss your needs with me in advance of the quizzes, papers, and notebooks. I will maintain the confidentiality of your learning needs. If appropriate, you should contact the Equal Opportunity, Affirmative Action, and Disability Services Department to get more information on accommodating disabilities.

- Provide an easily understood and detailed course syllabus. Make the syllabus, texts, and other materials available before registration.

- If materials are on-line, consider colors, fonts, and formats that are easily viewed by students with low vision or a form of color blindness.

- Clearly spell out expectations before the course begins (e.g., grading, material to be covered, due dates).

- Make sure that all students can access your office or arrange to meet in a location that is more accessible.

- On the first day of class, you can distribute a brief Getting to Know You questionnaire that ends with the question ‘Is there anything you’d like me to know about you?’ This invites students to privately self-disclose important challenges that may not meet the EAD accommodations requirements or that may be uncomfortable for the student to talk to you about in person upon first meeting you.

- Don’t assume what students can or cannot do with regards to participating in classroom activities. Think of multiple ways students may be able to participate without feeling excluded. The next section on “Teaching for Inclusion” has some ideas for alternative participation.

Teaching for Inclusion: Inclusive Design

One of the common concerns instructors have about accommodations is whether they will change the nature of the course they are teaching. However, accommodations are designed to give all students equal access to learning in the classroom. When planning your course, consider the following questions (from Scott, 1998):

What is the purpose of the course? What methods of instruction are absolutely necessary? Why? What outcomes are absolutely required of all students? Why? What methods of assessing student outcomes are absolutely necessary? Why? What are acceptable levels of performance on these student outcome measures

Answering these questions can help you define essential requirements for you and your students. For instance, participation in lab settings is critical for many biology classes; however, is traditional class lecture the only means of delivering instruction in a humanities or social science course? Additionally, is an in-class written essay exam the only means of evaluating a student who has limited use of her hands? Could an in-person or taped oral exam accomplish the same goal? (Scott, 1998; Bourke, Strehorn, & Silver, 2000)

When teaching a student with any disability, it is important to remember that many of the principles for inclusive design could be considered beneficial to any student. The idea of “Universal Design” is a method of designing course materials, content, and instruction to benefit all learners. Instead of adapting or retrofitting a course to a specific audience, Universal Design emphasizes environments that are accessible to everyone regardless of ability. By focusing on these design principles when crafting a syllabus, you may find that most of your course easily accommodates all students. (Hodge & Preston-Sabin, 1997)

Many of Universal Design’s methods emphasize a deliberate type of teaching that clearly lays out the course’s goals for the semester and for the particular class period. For instance, a syllabus with clear course objectives, assignment details, and deadlines helps students plan their schedules accordingly. Additionally, providing an outline of the day’s topic at the beginning of a class period and summarizing key points at the end can help students understand the logic of your organization and give them more time to record the information.

Similarly, some instructional material may be difficult for students with certain disabilities. For instance, when showing a video in class you need to consider your audience. Students with visual disabilities may have difficulty seeing non-verbalized actions; while those with disorders like photosensitive epilepsy may experience seizures with flashing lights or images; and those students with hearing loss may not be able to hear the accompanying audio. Using closed-captioning, providing electronic transcripts, describing on-screen action, allowing students to check the video out on their own, and outlining the role the video plays in the day’s lesson helps reduce the access barrier for students with disabilities and allows them the ability to be an active member of the class. Additionally, it allows other students the opportunity to engage with the material in multiple ways as needed. (Burgstahler & Cory, 2010; Scott, McGuire & Shaw, 2003; Silver, Bourke & Strehorn, 1998)

For more information on Universal Design or making your class more inclusive at Vanderbilt, the Center for Teaching offers workshops and one-on-one consultations. Additionally, the EAD office can help students and instructors address any questions or concerns they may have (322-4705).

The Association for Higher Education and Disability (AHEAD) has a list of resources for implementing universal design principles in the classroom: www.ahead.org/resources/ud

Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), home to the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID), has an extensive guide on considerations and suggested classroom practices for teaching students with disabilities: http://www.rit.edu/studentaffairs/disabilityservices/info.php

The United Spinal Association has a publication on Tips for Interacting with People with Disabilities: http://www.unitedspinal.org/disability-etiquette/

References:

Bourke, A. B., Strehorn, K. C., & Silver, P. (2000). Faculty Members’ Provision of Instructional Accommodations to Students with LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 33 (1), 26-32.

Burgstahler, S., & Cory, R. (2010). Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice . Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Education Press.

Davis, B. G. (1993). Tools for teaching . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Hodge, B. M., & Preston-Sabin, J. (1997). Accommodations–or just good teaching?: Strategies for teaching college students with disabilities . Westport, Conn: Praeger.

May, A. L., & Stone, C. A. (2010). Stereotypes of individuals with learning disabilities: views of college students with and without learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43 (6), 483-499. doi: 10.1177/0022219409355483

National Center for Learning Disabilities. http://www.ncld.org/

Scorgie, K., Kildal, L., & Wilgosh, L. (2010). Post-Secondary Students with Disabilities: Issues Related to Empowerment and Self-Determination. Developmental Disabilities Bulletin, 38 (2010), 133-145.

Scott, S. S. (1998). Accommodating College Students with Learning Disabilities: How Much Is Enough?. Innovative Higher Education, 22 (2), 85-99.

Scott, S., Mcguire, J., & Shaw, S. (2003). Universal Design for Instruction. Remedial and Special Education, 24 (6), 369-379.

Silver, P., Bourke, A., & Strehorn, K. C. (1998). Universal Instruction Design in Higher Education: An Approach for Inclusion. Equity & Excellence in Education, 31 (2), 47-51.

United States. (2002). Students with disabilities preparing for postsecondary education: Know your rights and responsibilities . Washington, D.C: U.S. Dept. of Education, Office for Civil Rights. Retrieved from http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS74685

Walters, S. (2010). Toward an Accessible Pedagogy: Dis/ability, Multimodality, and Universal Design in the Technical Communication Classroom. Technical Communication Quarterly , 19 (4), 427-454. doi:10.1080/10572252.2010.502090

Wolf, L. E., Brown, J. T., Bork, G. R. K., Volkmar, F. R., & Klin, A. (2009). Students with Asperger syndrome: A guide for college personnel . Shawnee Mission, Kan: Autism Asperger Pub. Co.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Teaching Individuals with Autism Problem-Solving Skills for Resolving Social Conflicts

- Research Article

- Published: 30 August 2021

- Volume 15 , pages 768–781, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Victoria D. Suarez 1 ,

- Adel C. Najdowski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2512-0397 2 ,

- Jonathan Tarbox 3 ,

- Emma Moon 2 , 4 ,

- Megan St. Clair 4 &

- Peter Farag 4

15k Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

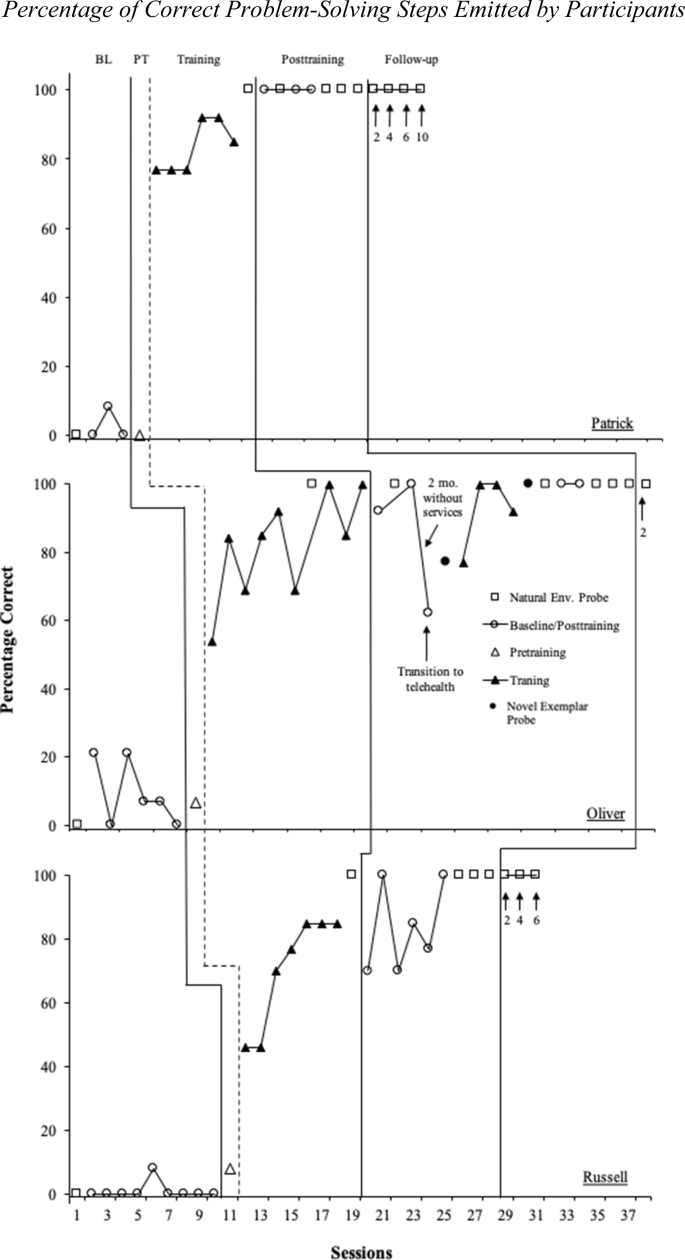

Resolving social conflicts is a complex skill that involves consideration of the group when selecting conflict solutions. Individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often have difficulty resolving social conflicts, yet this skill is important for successful social interaction, maintenance of relationships, and functional integration into society. This study used a nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design to assess the efficacy of a problem-solving training and generalization of problem solving to naturally occurring untrained social conflicts. Three male participants with ASD were taught to use a worksheet as a problem-solving tool using multiple exemplar training, error correction, rules, and reinforcement. The results showed that using the worksheet was successful in bringing about a solution to social conflicts occurring in the natural environment. In addition, the results showed that participants resolved untrained social conflicts in the absence of the worksheet during natural environment probe sessions.

Similar content being viewed by others

An Exploration of the Performance and Generalization Outcomes of a Social Skills Intervention for Adults with Autism and Intellectual Disabilities

Social Skills Training for Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Building Social Skills: An Investigation of a LEGO-Centered Social Skills Intervention

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Problem solving is traditionally defined as the ability to identify the problem and then create solutions for the problem (Agran et al., 2002 ). From a behavioral perspective, a person is faced with a problem when they experience a state of deprivation or aversive stimulation (Skinner, 1953, p. 246), and reinforcement is contingent upon a response that is in the person’s repertoire, but cannot be evoked under current conditions (Palmer, 1991 , 2009 ). According to Skinner ( 1953 ), “problem-solving may be defined as any behavior which, through the manipulation of variables, makes the appearance of a solution more probable” (p. 247). Therefore, problem solving involves mediating or precurrent behaviors that function to manipulate or generate discriminative stimuli needed to evoke a resolution response (Palmer, 1991 ; Skinner, 1984 ). See Szabo ( 2020 ) for a conceptual analysis of problem solving.

Behavioral researchers have taught specific problem-solving strategies to individuals for learning specific skills (see Axe et al., 2019 for a review), such as categorizing items (Kisamore et al., 2011 ; Sautter et al., 2011 ), explaining how to complete tasks (Frampton & Shillingsburg, 2018 ), and completing vocational tasks (Lora et al., 2019 ). Such problem-solving strategies functioned to teach participants to engage in mediating or precurrent behaviors that brought about a resolution. For example, Sautter et al. ( 2011 ) taught participants to use rules as a precurrent behavior to evoke the resolution of sorting stimuli. Kisamore et al. ( 2011 ) taught participants a visual imagining strategy as a precurrent behavior to evoke the resolution of categorizing. Frampton and Shillingsburg ( 2018 ) taught participants to sort and sequence visual stimuli of each step of a multistep task as a precurrent behavior to evoke explaining how to complete the multistep task.

Another type of scenario that requires one to engage in problem solving is when dealing with social conflict. Resolving social conflicts likely involves similar precurrent behaviors addressed in previous behavioral literature, such as behavior chains, rules, self-questioning, sequencing, and potentially visual imagining (See Axe et al., 2019 , for a review). However, because social conflicts by definition involve interacting with other people, successfully resolving social conflicts also likely involves engaging in perspective taking, including tacting others’ perspectives, engaging in deictic relating behavior by switching perspectives (Luciano et al., 2020 ), and likely arranging for others involved in the conflict to also obtain reinforcement.

According to traditional psychology, problem solving begins to develop as early as the preschool years (e.g., Best et al., 2009 ; Garon et al., 2008 ). Yet, individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often display deficits in social skills (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013 ) and have been found to demonstrate difficulties resolving social conflicts (Bernard-Optiz et al., 2001 ).

Given that a defining feature of ASD is to present with deficits in social communication and interaction (APA, 2013 ) and that resolving social conflicts across a wide range of situations is essential for functional integration into society and the maintenance of relationships (Bonete et al., 2015 ), it appears necessary to identify effective methods for teaching individuals with ASD to engage in problem-solving skills that will aid social conflict resolution. However, behavioral research has not evaluated methods to teach problem-solving skills in this context specifically to individuals diagnosed with ASD.

Although the population of ASD has not been studied in previous behavioral research on using problem-solving strategies to deal with social conflicts, a study conducted by Park and Gaylord-Ross ( 1989 ) used behavioral procedures to teach individuals with intellectual disabilities precurrent behaviors including rules, self-questioning, and self-prompting to solve problems they encountered at work, including social initiations, mumbling, and conversation expansions and terminations. During training, the researchers provided participants with a picture of themselves in a social situation (e.g., passing by a familiar customer at their workplace) and asked them how they would behave in the presented situation. Participants were provided with seven rules or questions to ask themselves: (1) What is happening? (2) What are three behaviors I could emit? (3) What will be the outcome of each behavior? (4) Which is better? (5) Pick one (6) Emit the behavior and (7) How did I feel? Prompting, modeling, and praise were used to teach participants to use the seven rules/questions. Pictures of novel social situations (other than the target situation) were presented at the end of training sessions to assess generalization to untrained stimuli and only one of three participants demonstrated stimulus generalization. During follow-up, an audiocassette recorder was placed in the participants' shirt pockets to record their interactions during their work and evaluate generalization of responding to trained stimuli in the natural environment. The results of the study indicated that participants’ target behaviors improved during training, and follow-up performance in the natural environment improved compared to baseline.

In addition to the paucity of research on this topic within behavior analysis, there is limited research outside of the behavioral literature that has evaluated methods for teaching individuals with ASD to use problem-solving strategies for dealing with social conflicts. One notable exception is a study conducted by Bernard-Optiz et al. ( 2001 ), who used a web-based problem-solving program to teach typically developing children and children with ASD to select and develop appropriate solutions. In particular, social conflicts were presented to participants on a computer screen with choices of possible solutions and an option to insert an individualized solution. For example, participants were shown a scenario in which two children wanted a turn to go down a slide. An audio cue asking, “What would you do?” was presented, and icons offering problem-solving solutions, such as requesting to go first, were provided. A second audio cue asking, “Do you have any good ideas?” was subsequently presented, and the option to insert a unique solution was presented. Novel solutions identified by participants resulted in social praise, and the option to continue inputting novel solutions continued to appear until participants no longer produced additional responses. All participants demonstrated an increase in the number of appropriate novel solutions generated. The results of Bernard-Optiz et al. ( 2001 ) demonstrated that social praise and a web-based problem-solving program functioned to increase generativity of problem solutions. Moreover, the results demonstrated that participants with ASD were taught to generate novel solutions to social conflicts using prompts and reinforcement. However, as the authors point out, a limited selection of social conflict scenarios were presented during intervention. Perhaps the most substantial limitation to the study is the use of an analogue computer task, without assessing whether problem-solving skills improved during real-life social interactions. In addition, maintenance was not measured.

Although behavioral research has found that teaching precurrent behaviors led participants to solve problems (e.g., Frampton & Shillingsburg, 2018 ; Kisamore et al., 2011 ; Lora et al., 2019 ; Park & Gaylord-Ross, 1989; Sautter et al., 2011 ), no research of which we are aware has evaluated the effects of teaching precurrent behaviors for resolving social conflicts to individuals with ASD. Further, although nonbehavioral research demonstrates prompts and social praise may function to increase resolving social conflicts in children with ASD (Bernard-Optiz et al., 2001 ), it is unknown if prompts and reinforcement would be successful in teaching individuals with ASD to use precurrent behaviors to resolve social conflicts. In addition, although research by Park and Gaylord-Ross (1989) measured generalization to trained problems in the natural environment, there is a dearth of research measuring generalization to untrained social conflicts occurring in the natural environment. Furthermore, research that has evaluated generalization to untrained problems found positive results with only one of three participants (Park & Gaylord-Ross, 1989).

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the effects of a problem-solving training package conducted in the natural environment on the use of problem-solving skills (i.e., precurrent behaviors) to resolve untrained social conflicts by individuals with ASD. The problem-solving training package consisted of a problem-solving worksheet, multiple exemplar training, error correction, rules, and reinforcement. Generalization of problem solving to untrained conflicts was programmed for by using multiple exemplar training and was assessed throughout the course of the study.

Participants and Setting

Three male individuals, with primary language being English, participated. Patrick was an 11-year-old Indigenous, Latinx, and white male with diagnoses of ASD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and bipolar disorder. Oliver was a 22-year-old Israeli male with a diagnosis of ASD. Russell was a 10-year-old Indigenous, Latinx, and white male with diagnoses of ASD and ADHD.

All participants received applied behavior analytic (ABA) services from a community-based agency for 10–12 hr per week. They demonstrated a listener behavior repertoire by engaging in auditory–visual conditional discriminations and following multistep instructions, used vocal–verbal communication in full sentences, and read and wrote basic paragraphs (i.e., three to five sentences). In addition, they demonstrated well-developed language skills by engaging in echoics, mands, tacts, and intraverbals. All participants labeled emotions in others (e.g., answered “How does she feel?”), identified cause-and-effect (e.g., answered “Why?” and “What will happen if . . . ?” For example, “Why did the egg break?” [“Because you dropped it.”], or “What will happen if I drop this egg?” [“It will break.”]), identified emotional cause-and-effect (e.g., answered “Why is she sad?” or “What will happen if someone takes her toy?”), and followed rules (e.g., “If you’re wearing pink, then raise your hand.”). In addition, participants used pronouns in speech and demonstrated listener behavior according to pronouns. All participants had a history of learning via role play and engaged in up to four intraverbal exchanges with others. At the time of recruitment, Patrick’s overall score on the Basic Living Skills Assessment Protocol from the Assessment of Functional Living Skills (AFLS) was 469 and Russell’s overall score was 475. No standardized assessment scores are available for Oliver, because his most recent assessment conducted prior to participation in this study was conducted using a commercially available web-based platform that does not provide raw scores. Participants were included because they did not independently and appropriately resolve social conflicts, and deficiency in resolving social conflicts was affecting their maintenance of positive relationships with siblings or parents. Individuals who demonstrated significant challenging behavior severe enough to interfere with instruction (e.g., self-injurious behavior [SIB], moderate to severe aggression) were ineligible to participate.

Participants were recruited because they were determined to benefit from learning to resolve social conflicts by their supervising clinician. Moreover, participants were recruited by asking them (for Oliver) or their parents (for Patrick and Russell) if they would like to participate in a research study evaluating a lesson for teaching problem-solving skills to resolve social conflicts. Consent was obtained by providing a consent form outlining the study’s purpose, methods, and potential benefits/risks to Oliver and the parents of Patrick and Russell. In addition, assent forms were provided to Patrick and Russell.

Research sessions were conducted during regularly scheduled ABA-based teaching sessions in home-based and clinic-based settings for the duration of the study with the exception of Oliver who made a transition from home- and clinic-based sessions to solely telehealth sessions (due to the COVID-19 pandemic) beginning with session 21. Research sessions were conducted in various rooms throughout the session environment (e.g., bedroom, living room, lobby, conference room). Research sessions were 5–30 min in length and consisted of the presentation of one problem. One to two research sessions (conducted at least 30 min apart) were conducted 1–3 days per week.

Response Measurement and Data Collection

A problem-solving task analysis (TA; Table 1 ) was used to calculate the percentage of correct, independent problem-solving steps completed by each participant. Each step of the TA was scored as correct or incorrect based on the specified criteria (Table 1 ). A correct response included independently and accurately completing a step within the task analysis by either writing a response or vocally stating a response within 10 s of: (1) the problem occurring (step 1) and (2) the previous step being completed (steps 2–13). An incorrect response included responses irrelevant to the current step, prompted responses, and nonresponses (i.e., failure to respond within 10 s of the problem [step 1] or previous step occurring [steps 2–14]). During baseline and posttraining, if the participant was not progressing through the conflict (e.g., not doing anything to resolve the conflict) after 1 min of the problem occurring, the conflict was ended by the interventionist resolving the conflict (e.g., if the conflict was that brother left Legos on the table where the participant was going to eat, the interventionist resolved the conflict by removing the Legos) and all remaining steps of the TA were scored as incorrect.

Natural environment probes (explained below) were scored as all or nothing. If the participant successfully resolved the social conflict by engaging in a viable solution (i.e., any solution that would function to resolve the conflict and could be readily carried out) within 10 s of the conflict occurring, the natural environment probe was scored as 100% correct. On the other hand, if the participant failed to resolve the social conflict (i.e., proposed and/or engaged in an impracticable solution or was nonresponsive as defined earlier), the natural environment probe was scored as 0% correct.

Interobserver agreement (IOA) was collected by two independent observers who recorded data during 33% of baseline sessions for all participants. IOA data were collected during 50%, 62%, and 57% of training sessions for Patrick, Oliver, and Russell, respectively. Moreover, IOA data were collected during 67% of posttraining sessions for Patrick and Oliver and 50% for Russell. IOA data were collected during 75% of follow-up sessions for Patrick and 100% for Oliver and Russell. Finally, IOA data were collected during 50%, 40%, and 50% of natural environment probes for Patrick, Oliver, and Russell, respectively. Point-by-point agreement was used to identify observers’ agreement on whether each step was performed correctly versus incorrectly by dividing the number of steps for which there was agreement by the total number of steps and multiplying the resulting quotient by 100%.. Mean IOA was 100%, 98.8% (range; 90%–100%), and 98.7% (range: 90%–100%) for Patrick, Oliver, and Russell, respectively.

Experimental Design and Procedure

A nonconcurrent multiple baseline across participants design was used to assess the effects of the problem-solving training package.

General Procedures

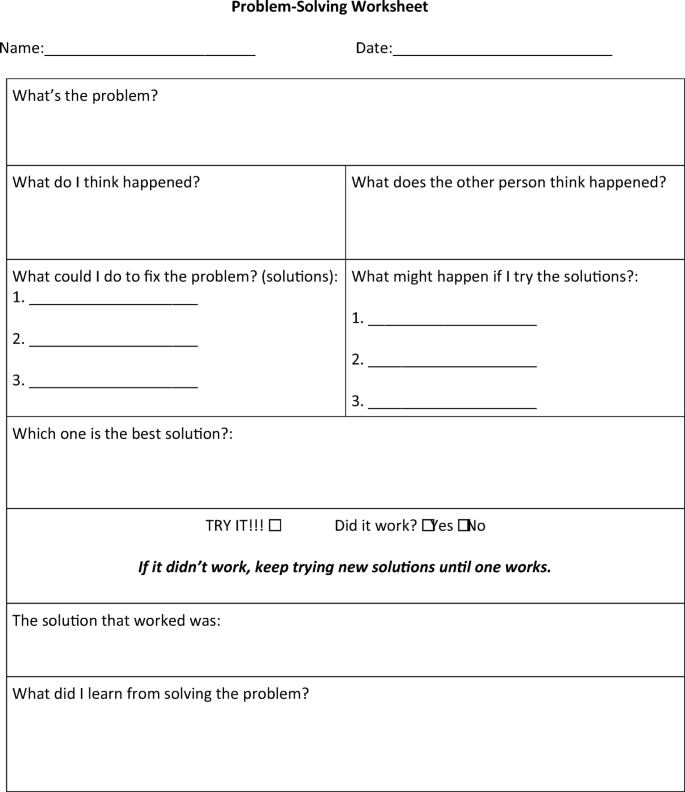

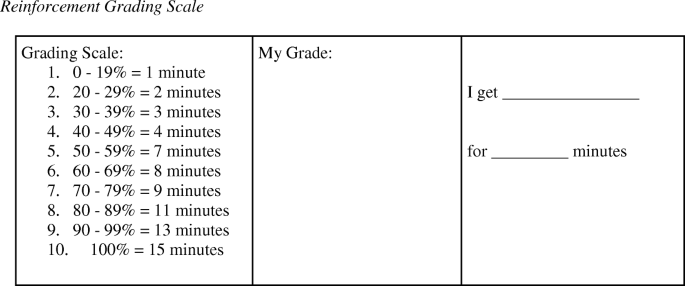

At the beginning of each ABA-based teaching session, participants were provided with a variation of the following instruction: “Today during your session, a social problem with someone will happen at some point. Here is a worksheet [see Fig. 1 ] you can use to help solve the problem when it happens.” The worksheet was written using language that was previously observed to be used by the participants and that they were familiar with.

Problem-solving worksheet

Then, ABA-based teaching activities began, and at some point between teaching activities, up to 15 min after delivering the instruction, a social conflict was contrived or captured with people in the natural environment. For example, when the participant and his brother both wanted to go first at a game, data were collected on how the participant responded to the problem-solving steps outlined on the TA. If the participant engaged in any negative emotional responding, such as whining or crying during the presentation of the social conflict, a second conflict was not presented again that day.

Social conflicts to be used were determined by interviewing the participants and their parents and asking them what situations usually led to arguments with others. In addition, we observed naturally occurring social interactions between the participants and others and identified situations in which a social conflict arose and the participant failed to resolve the conflict. We then set up these scenarios to occur during the research session. For example, Russell stated he argued with his brother when his brother wanted to play a video game that he was already playing. So, we arranged for Russell’s brother to request playing a video game that Russell was actively playing during the research session. Other times, the scenarios were genuinely captured, so we ran the research session upon capturing the naturally occurring conflict. For example, we observed that Patrick walked into his room to find that his brother had left dirty dishes on his desk and was notably upset as evidenced by his tone of voice, prosody, heavy breathing, and crying. The social conflicts contrived or captured are provided in Table 2 .