- High contrast

- Press Centre

Search UNICEF

Keynote speech to the world health summit 2021 – 24 october 2021, unicef executive director henrietta fore.

Excellencies, colleagues, friends … it is a pleasure to be with you here today for the World Health Summit.

I am honoured and inspired by the spirit of collaboration among experts in science, politics, business, government and civil society represented at this Summit.

On behalf of UNICEF, I am grateful for the opportunity to speak with you now at this critical moment in the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic – a pandemic which continues to impact so many aspects of our lives. COVID-19 has hobbled economies, strained societies and undermined the prospects of the next generation. While children are not at greatest direct risk from the virus itself, they continue to suffer disproportionately from its socioeconomic consequences. Almost two years into the pandemic, a generation of children are enduring prolonged school closures and ongoing disruptions to health, protection and education services.

That is why today I am here to discuss the health threats facing the 2.2 billion children around the world who UNICEF serves, and the opportunity we have to protect them.

Driven by new variants of concern, the virus continues to spread. While successful vaccination campaigns in the wealthy world have driven down rates of hospitalization and death, millions in low income countries await their first dose, and fragile health systems – on which children rely – are in jeopardy.

Yet the gap between those who have been offered vaccination against COVID-19 and those who have not is widening. While some countries have protected most of their populations, in others, less than 3 per cent of the population have had their first dose. Those going without vaccines include doctors, midwives, nurses, community health workers, teachers and social workers – the very people that children, mothers and families rely upon for the most essential services.

This is unacceptable. As a community of global health leaders, we have a choice. We can choose to act to reach more people with vaccines. This will keep people safe AND help to sustain critical services and systems for children.

Today, almost 7 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine have been administered, less than a year since the first vaccine was approved. And we are now on track to produce enough vaccines to protect the majority of people around the world before the end of next year.

But will we protect everyone?

Will we send lifesaving, health-system-saving COVID-19 vaccines to the world’s doctors, nurses, and most at-risk populations?

Will donors continue to fund ACT-A and COVAX sufficiently to procure and successfully deploy the tests, treatments and vaccines needed to end the pandemic? Or will the costs of in-country delivery fall on struggling economies so that they are forced to cut other lifesaving health programmes such as routine childhood vaccinations?

Will we stand by as the lowest-income countries, with the most fragile health systems, carry on unprotected – risking high death rates due to shortages of tests, treatments and vaccines? Or will we invest so that community health systems everywhere can withstand further waves of the virus, and bounce back from future shocks?

Will we allow new variants of the virus to flourish in countries with low vaccination rates? Or, will we reap the benefits of global cooperation to defeat this global problem, together?

The world has learned that financing for prevention, preparedness and response is insufficient and not adequately coordinated. And that is a vital lesson.

But even more fundamentally, we have learned that the underlying strength of the health sector in general is a critical factor in a country’s ability to weather a storm like COVID-19.

After all, what good are vaccines if there is no functioning public health system to deliver them?

How do we hope to contain outbreaks if there are not enough trained and paid healthcare workers?

This pandemic has been crippling for high income countries where average spending on healthcare per capita exceeds $5,000. So, it is hardly surprising that it is causing critical strain in lower-income countries where the average per capita expenditure on healthcare each year is less than $100.

The past 22 months have shown us that even as we battle immediate threats such as a pandemic, we must also ensure continuous access to essential health services. If we do not, there will be an indirect increase in morbidity and mortality.

As COVID-19 took hold of the world, healthcare workers serving pregnant mothers, babies and children faced unthinkable choices. As COVID patients gasped for breath, desperate for oxygen, mothers and babies needed it too. As wards filled up with virus victims, staff were not free to help the very young. As health budgets were stretched to the breaking point, routine healthcare began to go by the wayside.

These are some of the reasons why more than twice as many women and children have lost their lives for every COVID-19 death in many low and middle-income countries. Estimates from the Lancet suggest up to nearly 114,000 additional women and children died during this period.

I greatly fear that the pandemic’s impact on children’s health is only starting to be seen.

While the pandemic has underscored that vaccination is one of the most cost-effective public health interventions, we have already seen backsliding in routine immunization. In 2020, over 23 million children missed out on essential vaccines – an increase of nearly 4 million from 2019, with decades of progress tragically eroded.

Of these 23 million, 17 million of them did not receive any vaccines at all. These are the so-called zero-dose children, most of whom live in communities with multiple deprivations.

Here are some of the most urgent choices we could make to address these problems:

Governments can share COVID-19 doses with COVAX as a matter of absolute urgency and resist the temptation to stockpile supplies more than necessary.

Governments can also honour their commitments to equitable access and make space for COVAX and other parts of ACT-A at the front of the supply queue for tests, treatments, and vaccines as they roll off production lines.

Manufacturers can be more transparent about their production schedules and make greater efforts to facilitate and accelerate equitable access to products. This will help to ensure that COVAX and ACT-A get supplies faster.

Governments, development banks, business and philanthropy can target strategic, sustainable investments in building robust and resilient primary healthcare services – embedded in each and every community.

We can and we must choose a path ahead that is equitable, sustainable and rooted in the principle that every human being, young and old, rich and poor, has the right to good health.

And there is good reason to believe that now is the time to set ourselves upon that path.

A look back at history shows us that global threats and crises that challenge multiple interests and equities have a way of pulling together diverse partners to solve shared problems. Indeed, it is out of some of the most tragic crises that the world has found some of the best solutions.

I believe now is such a time. We have a historic opportunity to both end the COVID-19 pandemic and set out on the road towards eradicating preventable diseases, ending avoidable maternal, newborn and child deaths, and building a strong foundation for community health that will serve this generation and the next.

We can and we must seize this moment together.

Thank you.

Media contacts

About unicef.

UNICEF works in some of the world’s toughest places, to reach the world’s most disadvantaged children. Across more than 190 countries and territories, we work for every child, everywhere, to build a better world for everyone.

Follow UNICEF on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and YouTube

Related topics

More to explore, reaching children who missed out on vaccines in brazil.

Discover how community health workers navigate rural rivers and bustling cities to reach those who need vaccines most

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia pledges US $500 million to protect children around the world from polio and end the disease for good

UNICEF commends Bhutan for vaccinating almost all children with life-saving vaccines in historic feat

WHO and France convene high-level meeting to defeat meningitis

publication

Short Messages Encouraging Compliance with COVID-19 Public Health Guidelines Have Minimal Persuasive Effects

Sophia Pink, Michael Stagnaro, James Chu, Joe Mernyk, Jan Voelkel, Robb Willer

Preventing the spread of COVID-19 requires persuading the vast majority of the public to significantly change their behavior in numerous, costly ways. Many efforts to encourage behavior change – public service announcements, social media posts, speeches, billboards – involve relatively short, persuasive messages. Here, we report results of five experimental tests (N = 5,351) of persuasive short messages conducted in the US from March – July 2020. In our first two studies participants rated the persuasiveness of 56 unique messages (31 drawn from the social science literature, 25 crowdsourced from online respondents). We then conducted three well-powered, pre-registered experiments testing whether the four top-rated messages would increase intentions to comply with public health guidelines. We compare messages to both a null control condition and an “active control” message that included a reminder of the virus and suggested behaviors with no persuasive frame. Five messages in the initial studies were rated as more persuasive than a control, and four messages in the later studies increased behavioral compliance intentions relative to a null control. However, none of these messages had consistent effects when compared to the active control message. We conclude that it may not be practically possible to identify short messages that reliably out-perform a simple reminder of the virus and recommended behaviors during the advanced stages of the pandemic. The most persuasive message studied was one emphasizing people’s civic responsibility to reciprocate healthcare workers’ sacrifices, which performed best in three of five studies.

How Is America Still This Bad at Talking About the Pandemic?

America’s leaders could stand to learn four lessons on how to communicate about COVID.

With cases decreasing, well more than 65 percent of the eligible population inoculated with effective vaccines, and new COVID therapeutics coming to market, the United States is in very different circumstances than it was in early 2020. Life is currently feeling a little more stable, the future a good deal more clear.

But one thing about the pandemic has remained largely unchanged: Political and scientific leaders are still struggling to communicate recommendations to the American public. Are mask mandates warranted at work and school? First we were told no; then, yes; now the answer, for good reasons this time, is changing again. Are fourth mRNA shots necessary for the most vulnerable? First the CDC said no; then, to get one five months after the third dose; and now the waiting period has been reduced to three months.

The Omicron surge that the country is now exiting may not be our last of this pandemic, and SARS-CoV-2 will surely not be the last virus to cause a pandemic . If we are to get through whatever lies ahead without more unnecessary mass death, we need to reflect on how pandemic communication has fallen short and how the country can get better at it. Over the past six months, I have planned and led a small faculty seminar at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health on the pandemic, the press, and public policy. I’ve gleaned four lessons about transmitting clear, practical information in changing circumstances. Our leaders would be wise to heed them.

1. The conventional wisdom about avoiding ambiguity and uncertainty is wrong.

A former local public-health official told me last year that aides to the elected official for whom they worked had advised them that the key to pandemic communications was to “keep it simple; never say ‘on the other hand.’” This may (or may not) be good practice in an election campaign, but it has proved both common and exceedingly bad counsel in a pandemic, when officials frequently need to offer guidance from a position of uncertainty.

In March 2020, for example, public-health officials needed to tell people whether they should avoid contact with suspect surfaces and whether they needed to wear masks outside clinical settings. In an excess of caution and based on experience with other pathogens, the CDC advised Americans to wipe things down. But when it came to masks, the agency seemed to abandon that precautionary approach. The situation was complicated: The best masks were in terribly short supply and urgently needed by the health-care system. Rather than receiving an explanation of the situation and advice to improvise cloth masks, the public was told to forgo masks altogether because they were unnecessary.

Read: How to talk about the coronavirus

Public-health officials’ failure to trust Americans with the truth was not sophisticated or even practical. When the advice was belatedly revised in a manner that revealed it had always been faulty, an erosion of trust began and has only accelerated over the ensuing two years.

Moreover, this mistake has been repeated again and again in new contexts. Last summer, for instance, advice was given to take off your mask outside, only to be sort of retracted for fear that people would not wear them in crowds, or inside, especially as Delta struck. Throughout the past year, there has been far too much reluctance to offer varying advice to the vaccinated and unvaccinated, and to the very young and very old.

Officials (and the press responsible for critiquing and distilling their advice) need to be more candid about uncertainty, more open about asking people to mitigate risks temporarily until our knowledge increases, more willing to vary guidance for different groups without worrying that this constitutes “mixed messaging.” In the short run, such an approach may be challenged as weakness, but in the long run it will be revealed as building credibility, trust, and thus strength.

2. In a pervasive crisis, science must adjust to politics.

Over and over in the pandemic, public-health officials have been both surprised and disappointed to find out that concerns they consider “political” have trumped scientific knowledge. Not only their surprise but even a measure of their disappointment is worth reconsidering.

This is not to say that public health should be held hostage to conspiracy theories or sheer mendacity, as was sometimes the case in the first year of the pandemic, when President Donald Trump was promoting quack cures and stubbornly resisting masking. But if “Follow the science” was once a watchword of public-health resistance, it later came to sometimes embody naivete. In a well-functioning system, science is not oppositional to politics, but neither does it supersede politics . Both are essential in a democratic society; they must coexist.

Jay Varma: Not every question has a scientific answer

When a public-health concern becomes a pervasive national crisis, under any leadership, it is inevitable—and actually proper—that what may be narrowly in the interest of optimal medical outcomes will be weighed against impacts on the economy, equity, educational imperatives, national security, and even national morale. In our democratic system, that weighing is left to our elected officials. Those officials have a duty to arm themselves with the best public-health advice, and public-health experts are obligated to make sure that both leaders and the public have access to that advice, whether the politicians wish to know it or not.

In retrospect, the United States might have been wise to impose fewer restrictions on elementary and secondary schools over the past two academic years—not because school closures didn’t help stop the spread of the virus, but because the educational and economic losses from widespread remote schooling might have outweighed the gains in reduced cases. The question is clearly more than scientific.

Top officeholders and scientists alike can do a better job of accommodating each other. On the one hand, political leaders would do well to remember that many of the most senior officials in relevant agencies, even those with appropriate professional training, have likely been selected (by them!) for political reasons, and may or may not be the most expert in a particular situation. It can be a grave error, particularly in a place like the White House, to make the leap from “We have our own doctors” to “We have the best doctors.”

Matthew Algeo: Presidential physicians don’t always tell the public the full story

On the other hand, scientists (and even amateur epidemiologists) would do well to formulate their advice to political executives with empathy for their perspective. This does not mean shading the truth or telling someone what you think they want to hear, but it does mean safeguarding a leader’s credibility and acknowledging the political or practical constraints they face. It also means understanding that, once decisions are made, as President John F. Kennedy reportedly observed, leaders must live with them while advisers can move on to other advice. President Joe Biden, for instance, has too often found himself personally announcing conclusions that were not yet certain and guidance that was likely to soon change.

3. Speak the same language the public does.

Communication is difficult when people are not speaking the same language . In the pandemic, we have seen this play out in two major ways. First: Scientists use words they think their listeners understand, only to find out much later that they don’t. Some researchers concluded early on that SARS-CoV-2 was what they term “airborne.” When many people responded by limiting the big change in their behavior to standing six feet apart, the scientists were enormously frustrated. That’s because by “airborne,” they didn’t mean merely that the virus was borne through air, but that it was aerosolized, and thus highly contagious, especially indoors . They wanted the public to stop interacting closely, especially indoors and unmasked. Recognizing earlier that the scientific and colloquial understandings of airborne didn’t match in this context would have made a difference, at least in messaging and possibly in consequences.

Read: Nine pandemic words that almost no one gets right

Second: Only a distinct minority of the population has a firm grasp of statistics, but many scientists communicate as if everyone does. In addition to emphasizing the rarity of vaccine side effects or the significant protection offered by the shots, officials must give the public a lens through which to understand the exceptions some of them are sure to encounter in their daily lives.

If a particular finding, for instance, applies to 99 percent of Americans, scientists and public officials need to acknowledge—clearly, candidly, right up front—that more than 3 million people will have a different experience from that norm. To duck this reality is to risk the sheer number of counterexamples seeming to “disprove” the valid conclusion. This is especially important in communicating to and through the press.

4. Never forget the heroes.

The darkest early days of the pandemic were redeemed somewhat by the national rallying around health-care professionals, first responders, and other essential workers. That focus on the heroes among us underlined the fact that, in a pandemic, we are fundamentally in the fight together, and the virus is our common enemy.

Leaders made a crucial communications mistake in not extending this lesson to the rollout of the vaccines, which were the result of both the genius and the hard and astoundingly fast work of another set of heroes. Greater celebration, beginning in late 2020, of these innovators, inventors, and even manufacturers could, I think, have made widespread division over the vaccines less likely and less pervasive.

From the January/February 2021 issue: How science beat the virus

It would, for instance, have helped if the editors of Time magazine had felt compelled to name the inventors of the mRNA vaccines as the 2021 “People of the Year,” rather than deeming them runners-up to Elon Musk. Glorifying pharmaceutical companies may be a stretch, but why not loudly praise the workers who churned out the “Warp Speed” vaccines as modern-day Rosie the Riveters?

In the absence of these sorts of celebrations, the division over vaccines remains the greatest failure of the U.S. experience of the pandemic. More than a quarter of a million deaths were likely directly preventable by available vaccination. Undervaccination contributed to the horrible strength of the Delta and Omicron waves, lingering economic pain, and remote schooling, which might also have been avoided. Next time, the communication breakdown may or may not center on vaccines. But we’d all be much better off if we didn’t have a breakdown at all.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- News & Events

- Speeches by FDA Officials

- The Critical Role of Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic - 08/10/2020

Speech | Virtual

Event Title The Critical Role of Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic August 10, 2020

(Remarks as prepared for delivery)

I’m pleased to have the opportunity today to speak with you about COVID-19, the FDA’s role in responding to this public health emergency, and the continuing challenges the agency and the medical profession face as it continues to evolve.

I’d like to begin by thanking Dr. Susan Bailey and the American Medical Association for hosting and moderating this event today, as well as the Reagan Udall Foundation for their continuing support of the FDA.

And I’d like to thank all of the physicians and health care professionals on this call today for your hard work, thoughtfulness, and commitment during this challenging time. Among the heroes who have emerged from this crisis are the health care professionals who have risked their own health to serve their patients. The nation is indebted to you.

As we move forward, we know that the pandemic continues to evolve and the health care community must continue to deliver high-quality care to all patients.

Fortunately, we’ve made significant progress in our understanding of this disease, our ability to combat it, and our efforts to help patients suffering with it.

As health care professionals and scientists, we understand there are no easy answers. We still have much more to learn about this disease, with many unanswered questions. And we need to not only treat patients with the disease, but also to prevent the spread of the disease as we seek effective therapeutics and safe and effective vaccines.

Today, I want to talk to you about some of these challenges and about the nature and importance of science and data as we search for answers.

I also want to speak with you in your role as doctors and other health professionals, who are dealing with very practical questions involving patients – an experience I understand and empathize with from my own practice as an oncologist.

Most importantly, I want to reassure you that the decisions that FDA will have to make in the coming months, with regard to new tests for COVID-19, new therapeutics, and new vaccines, will be based on good science and sound data.

Because of the speed with which we need to make decisions, there has been discussion about whether FDA will compromise any of our scientific principles in reviewing data and making decisions about new products. Let me assure you that we will not cut corners.

All of our decisions will continue to be based on good science and the same careful, deliberative processes which we have always used when reviewing medical products.

It is important that you as medical practitioners not only understand this commitment, but also that you reassure your patients.

We have seen surveys reporting that significant percentages of the public would be reluctant to take a vaccine once available. We hope that you will urge your patients to take an approved vaccine so that we can seek to establish widespread immunity.

We can emerge from this emergency only by working together.

We know that the overwhelming quantities of COVID-19 information and data that seem continually to be expanding can place a significant burden on you as clinicians seeking to respond to patient questions and, when appropriate, modify treatment recommendations.

Indeed, COVID-19 is affecting the practice of medicine in many ways, and the FDA has an important role to play in supporting providers and patients through this evolution. Although it seems as if we’ve been engaged in the battle against COVID-19 for a very long time, in the broader context of disease and science, it’s actually been a relatively short period.

Consider that as recently as this January – just eight months ago – few people, other than a limited group of health care professionals and infectious disease experts, had even heard of the novel coronavirus.

It’s easy for me to recall just how recently SARS-CoV-2 appeared on our national radar. That’s because the first reports of the outbreak began just a few weeks after I was sworn in as FDA commissioner. I’d like to share with you my own experiences and what I have learned in the past six months.

From the very beginning, this has been a perplexing and challenging medical mystery, presenting far more questions than answers. Even for those who have followed this public health crisis from its earliest days, little information or understanding of the disease was available.

We didn’t know, for instance, basic things, such as how aggressive, virulent, or contagious the virus was.

That’s not a comfortable position for health professionals who like to be well informed, particularly when we work at agencies charged with protecting the American public.

I learned quickly that despite the relative lack of knowledge, we at the FDA had to make decisions about relative benefits and risks with the data we had.

The FDA regulates the safety, effectiveness and quality of all medical products – drugs, vaccines, and medical devices. We also regulate food safety, which of course also is critical during a crisis like this.

There is always a steep learning curve in the response to a public health emergency, particularly when it involves a new disease. But this learning curve has been especially steep for all of us.

I am trained, as many of you are, as a scientist. And when this pandemic emerged, I conveyed to the leadership and staff at the FDA that even in the face of the public response to this emergency, we at the FDA needed to apply scientific rigor to any decisions being made, no matter how quickly they needed to be made,

It was reassuring to me that the FDA leadership and staff agreed whole-heartedly with this approach. This is how the FDA has always functioned in its role as a federal agency that makes regulatory decisions based on scientific rigor.

We at the FDA, and you as health care professionals have had to respond to challenges like these in real time.

For this pandemic, in particular, for the FDA this has meant supporting the development of safe and effective medical countermeasures.

These actions also included ensuring that our front-line health care workers had and will continue to have the necessary protective equipment.

Since the beginning of this pandemic, FDA scientists have been immersed in providing essential regulatory advice, guidance, and technical assistance needed to advance the development of tests, therapies, and vaccines.

And it’s meant that we have been vigilant in seeking to prevent the sale of fraudulent products that could harm the public.

To be successful in each of these efforts, we’ve been working hard to strengthen the scientific response. We’ve done this by supporting collaborative efforts, creating open communication channels, and building public-private partnerships.

For example, the FDA has created resources like reference-grade sequence data for SARS-CoV-2 to support research and reference panels for COVID-19 diagnostic tests to support continued developments in testing.

The agency has supported the National Institutes of Health’s public-private partnership for therapeutic and vaccine development.

The FDA has also partnered with a number of external partners to gather real world evidence to help inform our understanding of the natural history of COVID-19, drug utilization and performance of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics.

I’m pleased that so many of you -- and the professional organizations you are part of -- have been involved in some of these collaborative efforts.

It’s essential that we bring forward the best ideas and innovations to support the development of new and effective treatments. Working together has been an instrumental part in our ability to come so far, so fast.

Our approach is consistent with and, indeed, goes to the core of the FDA’s mission; we constantly gather new information and evidence about the disease to inform our actions.

As we learn, we discover more answers. But that, in and of itself, is not enough. We must continue to be vigilant and aggressive, constantly reviewing and evaluating the data as they emerge.

The principle underlying this -- that our decisions must not only be informed by the most rigorous data and best science, but also that the evidence on which we base our continuing review is regularly refreshed and expanded through new experiences and opportunities -- is a basic approach of science.

It’s certainly a personal principle that has been a priority for me throughout my career as a physician and researcher.

We are learning more every day. For example, as doctors have treated more cases of COVID, it has become clear that it is not just a respiratory ailment but can affect many organ systems, including the kidneys and heart, and can also cause vascular complications.

And although initially, many of us believed children were not significantly affected by the COVID-19 virus, subsequent reports from across the United States and Europe showed that some young COVID patients were found to have Pediatric Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome or PMIS.

These cases exhibited clinical features similar to Kawasaki Disease, a rare inflammatory disease primarily affecting young children, which causes blood vessels to become inflamed or swollen throughout the body.

Similarly, some dermatologists revealed that some of their patients who were later diagnosed with COVID-19 had symptoms that could be due to vasculitis, including frostbite like pain, small itchy eczema-like lesions on their extremities. and reddened patches of skin.

We are all concerned about the reports of rising case counts in different locations across the U.S., particularly in the Sunbelt states.

We have also learned that common sense public health measures such as the wearing of masks, social distancing, hand-washing, protection of the vulnerable, and avoidance of large indoor gatherings particularly in bars, do help stop the spread and mitigate community outbreaks. This is our country’s path forward.

The emerging data also continue to confirm the disproportionate impact of the disease on different communities, based on age, ethnicity, and race.

The Coronavirus Task Force, of which I am a member, continues to carefully analyze and monitor the prevalence of the virus throughout the U.S., using the best available science to track, predict and mitigate the curve of the outbreak. We are closely watching the entire country and working to determine the reason behind any new outbreaks or the spread of the disease.

At the FDA, our work goes beyond analyzing the numbers. Our responsibilities involve a range of efforts relating to the diagnosis, response, and treatment of COVID-19 and supporting solutions to bring an end to this crisis.

This includes facilitating the development of tests, both diagnostic and serologic, supporting the advance of treatments and vaccines for the disease, and working to ensure that health care workers and others have the personal protective equipment and other necessary medical products needed to combat it.

Since day one of this emergency, our focus in addressing these challenges has been to meet the need for speed.

To facilitate the development of new treatments and effective tests, and to make sure we have adequate supplies of essential medical equipment such as ventilators, we’ve redoubled our efforts to employ regulatory flexibility and streamlined processes where needed and appropriate, without compromising science.

The goal has been to use every available tool in our arsenal to move new treatments to patients as quickly as possible while helping ensure safety and efficacy.

We’re moving equally fast in our efforts to help support the development of COVID-19 vaccines.

As this audience is well aware, preventive vaccines for infectious disease are foundational to modern public health.

The FDA is committed to ensuring that potential vaccines for COVID-19 are safe and effective.

In June, the agency issued a guidance outlining key recommendations for vaccine development.

In particular, the agency emphasized the importance of recruiting diverse populations, especially those patients who have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic.

The FDA also recommended in the guidance that sponsors use an endpoint estimate of at least 50%, which could have an important impact on individual and public health, while vaccines with lower efficacy might not.

Several COVID-19 vaccine candidates have recently initiated large-scale clinical trials. While I cannot predict when the results from these studies will be ready, I can promise that when the data are available, the FDA will review them using its established, rigorous, and deliberative scientific review process.

We all understand that only by engaging in an open review process and relying on good science and sound data can the public have confidence in the integrity of our decisions.

One important tool we have used during public health emergencies to support the scientific investigation, is to employ our authority for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA).

An EUA allows the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions when certain criteria are met, including that there are no adequate, approved, and available alternatives.

These EUA decisions have been an important part of FDA’s efforts to shape an effective and timely response.

Though EUA decisions are based on emerging scientific evidence, we are continually evaluating and reevaluating that evidence in order to ensure that the known and potential benefits of products outweigh the known and potential risks.

Since the earliest days of the pandemic, we’ve issued EUAs for tests, ventilators, and drug treatments. The FDA has granted more than 190 EUAs for COVID-19 tests and has reviewed more than 200 clinical trials for potential therapies.

Nevertheless, we understand that the pace of FDA announcements and decisions can cause confusion for the public and providers.

For instance, some of you may be wondering whether an EUA changes the approach being used to develop drugs and vaccines. What should doctors tell their patients about what’s going on? What drugs are under development? Which are the safest or most effective?

This is a good opportunity to reiterate that although EUAs may be made on this emergency basis, they are guided by science and by continuous review of the most recent up-to-date evidence available.

Even after an EUA is issued, we regularly review that decision based on emerging information. We make any necessary changes as appropriate. This dynamic process is continually being informed by new data and evidence, and it always seeks to balance the risks with the benefits of every COVID-19 treatment.

Take testing, for example. Since day one, tests have played a key role in the ability to understand and manage this disease. Good, accurate, and reliable tests can help reveal who has the disease or, by virtue of the antibodies in someone’s system, who has been infected with the virus.

We’ve worked with hundreds of test developers, many of whom have submitted emergency use authorization requests to the FDA for tests that detect the virus or antibodies to it.

In light of the circumstances, FDA’s goal has always been to provide the necessary regulatory flexibility to support developers and to provide what patients and the public need as quickly as possible without compromising safety or scientific review.

Early on in this pandemic, the FDA posted a policy that explained that under certain circumstances, FDA did not intend to object to the use of tests that were developed and validated by laboratories prior to authorization of an EUA request. There was a national demand for such tests and we felt it was an appropriate decision to exercise regulatory flexibility concerning the use of these validated tests.

It was soon evident that some of the self-validated tests were not reliable and FDA moved quickly to update the policy in response to the available information.

Today, we have nearly 200 reliable, authorized tests. And we continue to monitor the performance of these tests and encourage the development of new and better tests that will enable us to understand this disease and help patients and the medical community address the challenges.

As we have done since the beginning of the pandemic, we will continue to balance the pressing need for access to diagnostic and antibody tests with our helping to ensure that available tests are accurate and reliable.

This same approach applies to potential treatments for COVID-19. We work closely with partners throughout the government, academia, and drug and vaccine developers to explore, expedite, and facilitate the development of products, and provide guidance and technical assistance to drug manufacturers to expedite clinical trials.

Our Coronavirus Treatment Acceleration Program, or CTAP, which we launched in March, has helped to focus the scientific and technical expertise of the agency’s staff to review potential products according to their scientific merit.

By providing enhanced regulatory support, the FDA has been able to support the initiation of more than 200 trials for COVID-19 therapies over the past few months.

This work is essential to returning us to some semblance of normalcy. After all, we need treatments and cures.

But there’s a corresponding aspect of the FDA’s work that is also essential.

This role is to support you, as physicians and medical providers to help answer your patients’ questions. Certainly, explaining the process, as complicated as it is, is an important piece of the response.

To understand this, it may be instructive to look at some actions we’ve taken with several drugs, each of which were granted an EUA, and that received significant public attention.

Back in March, the FDA granted an EUA to allow the drugs chloroquine phosphate and hydroxychloroquine sulfate to be used to treat certain hospitalized COVID-19 patients when a clinical trial was unavailable, or when participation in a clinical trial was not feasible. Early but limited research indicated that the drugs, which are approved to treat malaria and have a well-understood safety profile, might be effective in treating COVID.

After the EUA was issued, FDA continued to monitor the emerging clinical evidence on the use of these drugs in COVID-19 patients.

Based on null results from randomized controlled trials and further analysis of clinical pharmacology information, the FDA determined that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are unlikely to be effective in treating COVID-19 in the patient population covered by the EUA and no longer met the legal criteria for emergency use. As a result, we revoked the EUA in June.

Separately, the FDA issued an EUA for the antiviral drug remdesivir in May.

A randomized trial led by the National Institutes of Health found that remdesivir helped to reduce the length of hospitalization for COVID-19 patients. Additional trials have been completed or are planned to help us understand the appropriate role for remdesivir in this COVID crisis.

Because of the nature of the pandemic, there may be confusion or a lack of understanding about the actions we have taken on therapeutics.

We rely on you in the medical community to answer patients’ inevitable questions about treatments and vaccine development. It is our responsibility at the FDA to provide you with the information you need for your patients.

The fundamental message that we need to communicate is that the FDA’s decisions are based on science, that decisions sometimes change based on our careful review of the most recent evidence, and that we are committed to ensuring that the drugs we approve are safe and effective based on reliable data.

Physicians and other health care professionals have other important roles and responsibilities. One they share with the FDA is to help ensure that the public gets the products they are being promised and to be aware of and avoid scams being perpetrated on them.

The FDA regularly warns consumers to be cautious of websites and stores selling products with unproven claims to prevent, treat, diagnose or cure COVID-19 or unauthorized test kits. The FDA has not evaluated these fraudulent products for safety and effectiveness, and these products might actually be dangerous to patients.

To help tackle the issue of health fraud during the pandemic, the FDA launched Operation Quack Hack, which monitors online marketplaces for fraudulent products and identifies misinformation about COVID-19.

The agency has identified more than 700 fraudulent and unproven medical products related to COVID-19 and has collaborated with the Federal Trade Commission to issue warning letters to firms marketing products with misleading claims, and sent more than 150 reports to online marketplaces, and more than 250 abuse complaints to domain registrars to date.

We make most of this information available on our website and encourage doctors to become familiar with this resource and share this information with their patients.

Physicians have an important role in this area because of your ability to identify and track patients who take illegitimate or black-market drugs.

There is currently no cure for the coronavirus, and it is important for doctors to help inform patients about dangerous products and unscrupulous marketers who may be selling products with false or misleading claims.

Eight months into the pandemic, we have made important progress. Yet with cases continuing to rise, it is evident that further action is needed for our country to chart a course for recovery.

The FDA is launching the COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery and Preparedness Plan (PREPP) to help apply best practices and lessons learned from the emergency response to date. Our goal is to make needed adjustments to support the ongoing COVID-19 response, while also strengthening our resilience and improving our capacity to respond to public health emergencies in the future.

As doctors, we ensure that our treatment plans for our patients are adjusted according to the latest evidence.

I believe this same principle applies to the FDA, which as a science-based agency, is committed to continuous improvement by examining the data and modernizing our approaches when needed.

As we identify lessons and make subsequent changes, we are committed to proactively communicating any forthcoming regulatory changes to doctors and other health professionals.

Though we don’t have all the answers, we do know is that the COVID-19 virus will be with us for the foreseeable future. We are still far from understanding every aspect of this disease.

But the FDA will continue to operate with patient safety and scientific integrity as our North Star. It is this approach that continues to guide the development of new technologies and necessary regulations for safeguarding public health for the present and future.

Our goal is to provide you with the information and understanding you need to ensure that patients receive the support, attention and treatment they deserve. We look forward to working with you to achieve that goal.

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- MHT CET 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Main Question Paper

- JEE Main Cutoff

- JEE Main Advanced Admit Card

- JEE Advanced Admit Card 2024

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- KCET Result

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2023

- CAT 2023 College Predictor

- CMAT 2024 Admit Card

- TS ICET 2024 Hall Ticket

- CMAT Result 2024

- MAH MBA CET Cutoff 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Admit Card 2024

- NEET PG Application Form 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top NLUs Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Top NIFT Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET Exam City Intimation Slip 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET Mock Test 2024

- CUET Admit card 2024

- CUET PG Syllabus 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Cut Off 2024

- CUET Exam Analysis 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- CUET 2024 Exam Live

- CUET Answer Key 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

2 Minute Speech on Covid-19 (CoronaVirus) for Students

The year, 2019, saw the discovery of a previously unknown coronavirus illness, Covid-19 . The Coronavirus has affected the way we go about our everyday lives. This pandemic has devastated millions of people, either unwell or passed away due to the sickness. The most common symptoms of this viral illness include a high temperature, a cough, bone pain, and difficulties with the respiratory system. In addition to these symptoms, patients infected with the coronavirus may also feel weariness, a sore throat, muscular discomfort, and a loss of taste or smell.

10 Lines Speech on Covid-19 for Students

The Coronavirus is a member of a family of viruses that may infect their hosts exceptionally quickly.

Humans created the Coronavirus in the city of Wuhan in China, where it first appeared.

The first confirmed case of the Coronavirus was found in India in January in the year 2020.

Protecting ourselves against the coronavirus is essential by covering our mouths and noses when we cough or sneeze to prevent the infection from spreading.

We must constantly wash our hands with antibacterial soap and face masks to protect ourselves.

To ensure our safety, the government has ordered the whole nation's closure to halt the virus's spread.

The Coronavirus forced all our classes to be taken online, as schools and institutions were shut down.

Due to the coronavirus, everyone was instructed to stay indoors throughout the lockdown.

During this period, I spent a lot of time playing games with family members.

Even though the cases of COVID-19 are a lot less now, we should still take precautions.

Short 2-Minute Speech on Covid 19 for Students

The coronavirus, also known as Covid - 19 , causes a severe illness. Those who are exposed to it become sick in their lungs. A brand-new virus is having a devastating effect throughout the globe. It's being passed from person to person via social interaction.

The first instance of Covid - 19 was discovered in December 2019 in Wuhan, China . The World Health Organization proclaimed the covid - 19 pandemic in March 2020. It has now reached every country in the globe. Droplets produced by an infected person's cough or sneeze might infect those nearby.

The severity of Covid-19 symptoms varies widely. Symptoms aren't always present. The typical symptoms are high temperatures, a dry cough, and difficulty breathing. Covid - 19 individuals also exhibit other symptoms such as weakness, a sore throat, muscular soreness, and a diminished sense of smell and taste.

Vaccination has been produced by many countries but the effectiveness of them is different for every individual. The only treatment then is to avoid contracting in the first place. We can accomplish that by following these protocols—

Put on a mask to hide your face. Use soap and hand sanitiser often to keep germs at bay.

Keep a distance of 5 to 6 feet at all times.

Never put your fingers in your mouth or nose.

Long 2-Minute Speech on Covid 19 for Students

As students, it's important for us to understand the gravity of the situation regarding the Covid-19 pandemic and the impact it has on our communities and the world at large. In this speech, I will discuss the real-world examples of the effects of the pandemic and its impact on various aspects of our lives.

Impact on Economy | The Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the global economy. We have seen how businesses have been forced to close their doors, leading to widespread job loss and economic hardship. Many individuals and families have been struggling to make ends meet, and this has led to a rise in poverty and inequality.

Impact on Healthcare Systems | The pandemic has also put a strain on healthcare systems around the world. Hospitals have been overwhelmed with patients, and healthcare workers have been stretched to their limits. This has highlighted the importance of investing in healthcare systems and ensuring that they are prepared for future crises.

Impact on Education | The pandemic has also affected the education system, with schools and universities being closed around the world. This has led to a shift towards online learning and the use of technology to continue education remotely. However, it has also highlighted the digital divide, with many students from low-income backgrounds facing difficulties in accessing online learning.

Impact on Mental Health | The pandemic has not only affected our physical health but also our mental health. We have seen how the isolation and uncertainty caused by the pandemic have led to an increase in stress, anxiety, and depression. It's important that we take care of our mental health and support each other during this difficult time.

Real-life Story of a Student

John is a high school student who was determined to succeed despite the struggles brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic.

John's school closed down in the early days of the pandemic, and he quickly found himself struggling to adjust to online learning. Without the structure and support of in-person classes, John found it difficult to stay focused and motivated. He also faced challenges at home, as his parents were both essential workers and were often not available to help him with his schoolwork.

Despite these struggles, John refused to let the pandemic defeat him. He made a schedule for himself, to stay on top of his assignments and set goals for himself. He also reached out to his teachers for additional support, and they were more than happy to help.

John also found ways to stay connected with his classmates and friends, even though they were physically apart. They formed a study group and would meet regularly over Zoom to discuss their assignments and provide each other with support.

Thanks to his hard work and determination, John was able to maintain good grades and even improved in some subjects. He graduated high school on time, and was even accepted into his first-choice college.

John's story is a testament to the resilience and determination of students everywhere. Despite the challenges brought on by the pandemic, he was able to succeed and achieve his goals. He shows us that with hard work, determination, and support, we can overcome even the toughest of obstacles.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

Register FREE for ALLEN Digital Scholarship Admission Test (ADSAT)

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

PW JEE Coaching

Enrol in PW Vidyapeeth center for JEE coaching

PW NEET Coaching

Enrol in PW Vidyapeeth center for NEET coaching

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Awareness and preparedness of covid-19 outbreak among healthcare workers and other residents of south-west saudi arabia: a cross-sectional survey.

- 1 Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Pharmacy Practice Research Unit (PPRU), College of Pharmacy, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

- 2 Department of Pharmacology, College of Pharmacy, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

- 3 Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, College of Pharmacy, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia

Background: Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) was declared a “pandemic” by the World Health Organization (WHO) in early March 2020. Globally, extraordinary measures are being adopted to combat the formidable spread of the ongoing outbreak. Under such conditions, people's adherence to preventive measures is greatly affected by their awareness of the disease.

Aim: This study was aimed to assess the level of awareness and preparedness to fight against COVID-19 among the healthcare workers (HCWs) and other residents of the South-West Saudi Arabia.

Methods: A community-based, cross-sectional survey was conducted using a self-developed structured questionnaire that was randomly distributed online among HCWs and other residents (age ≥ 12 years) of South-West Saudi Arabia for feedback. The collected data were analyzed using Stata 15 statistical software.

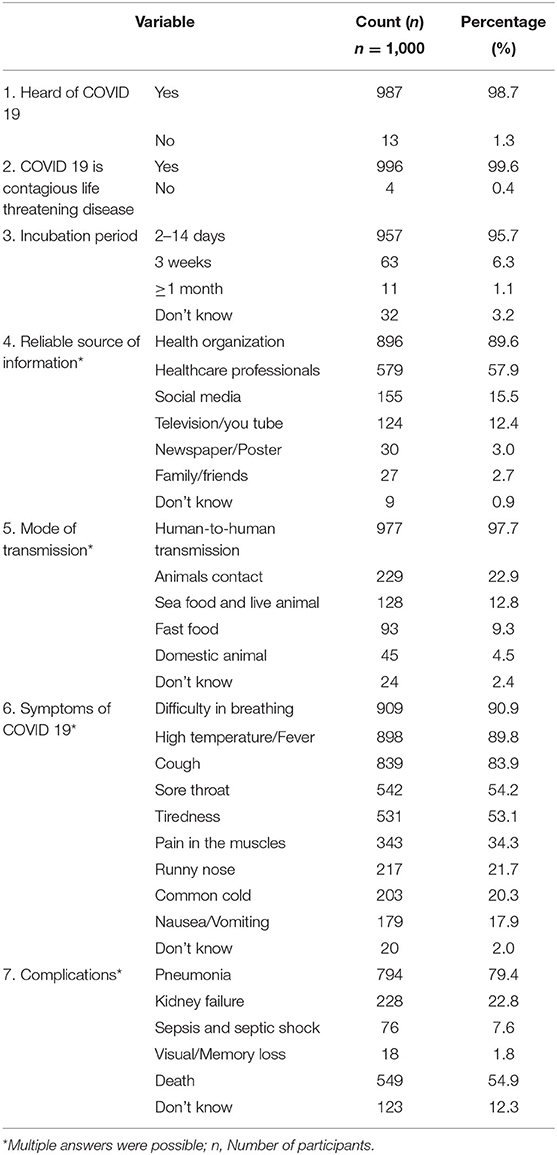

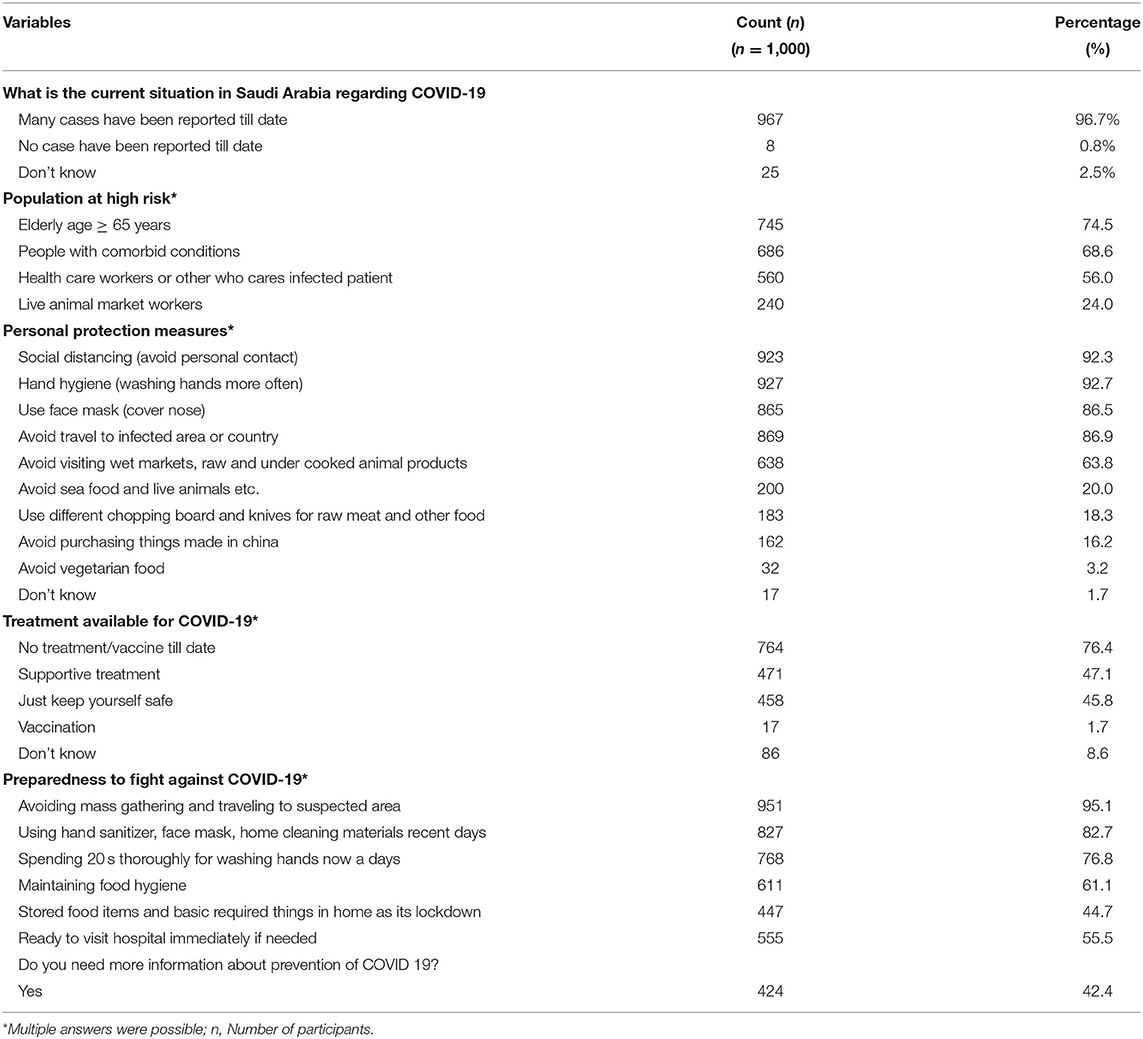

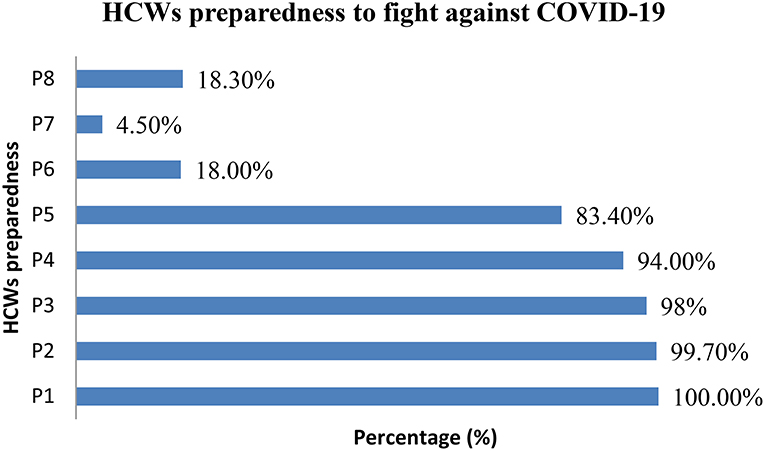

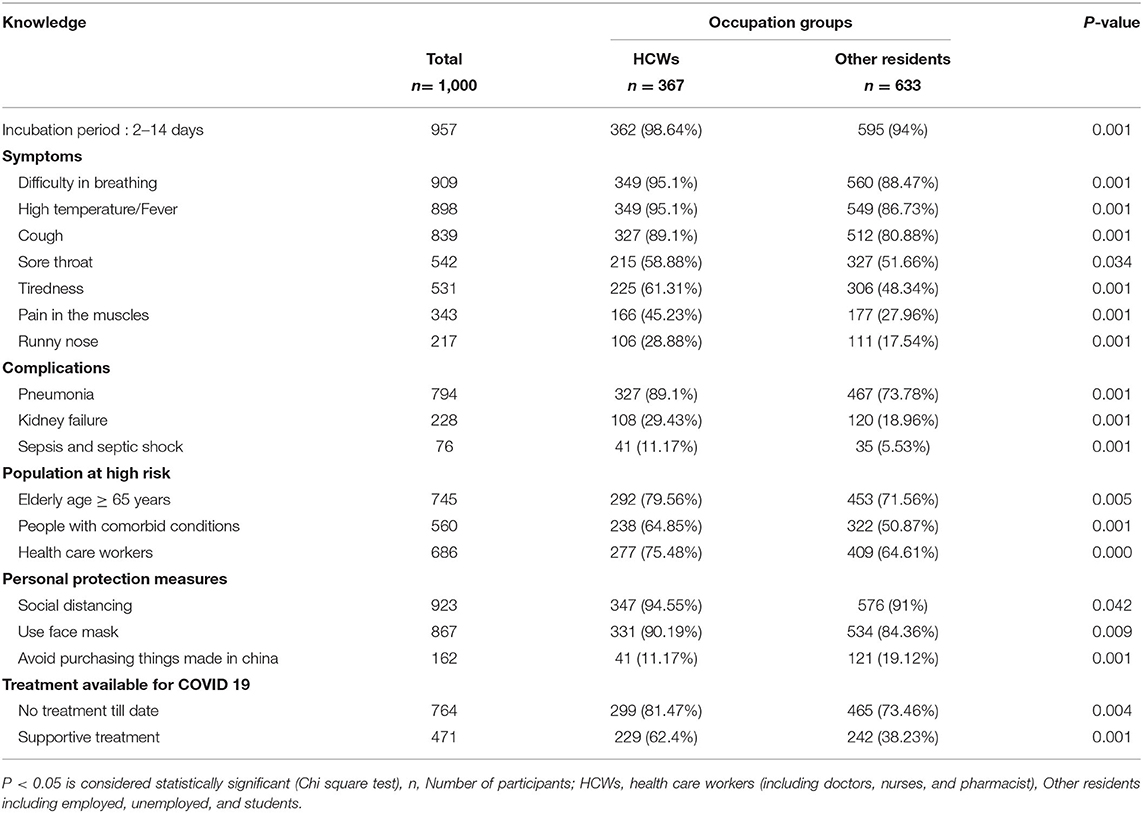

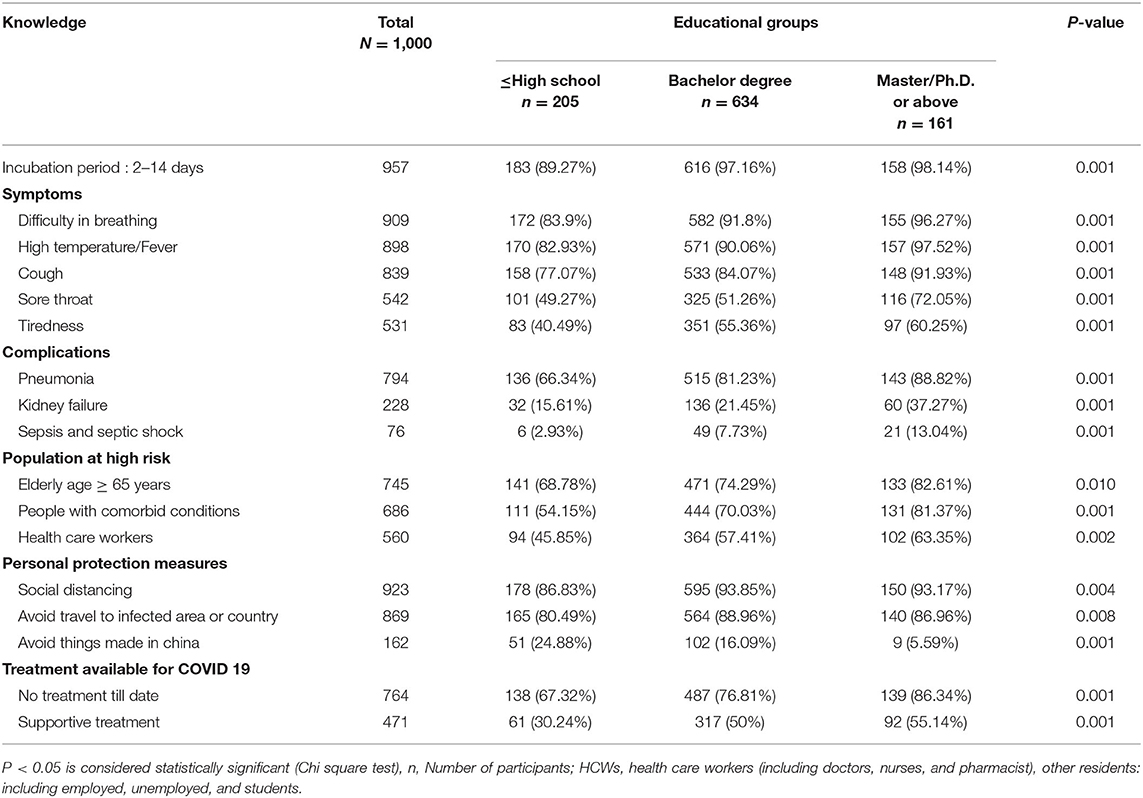

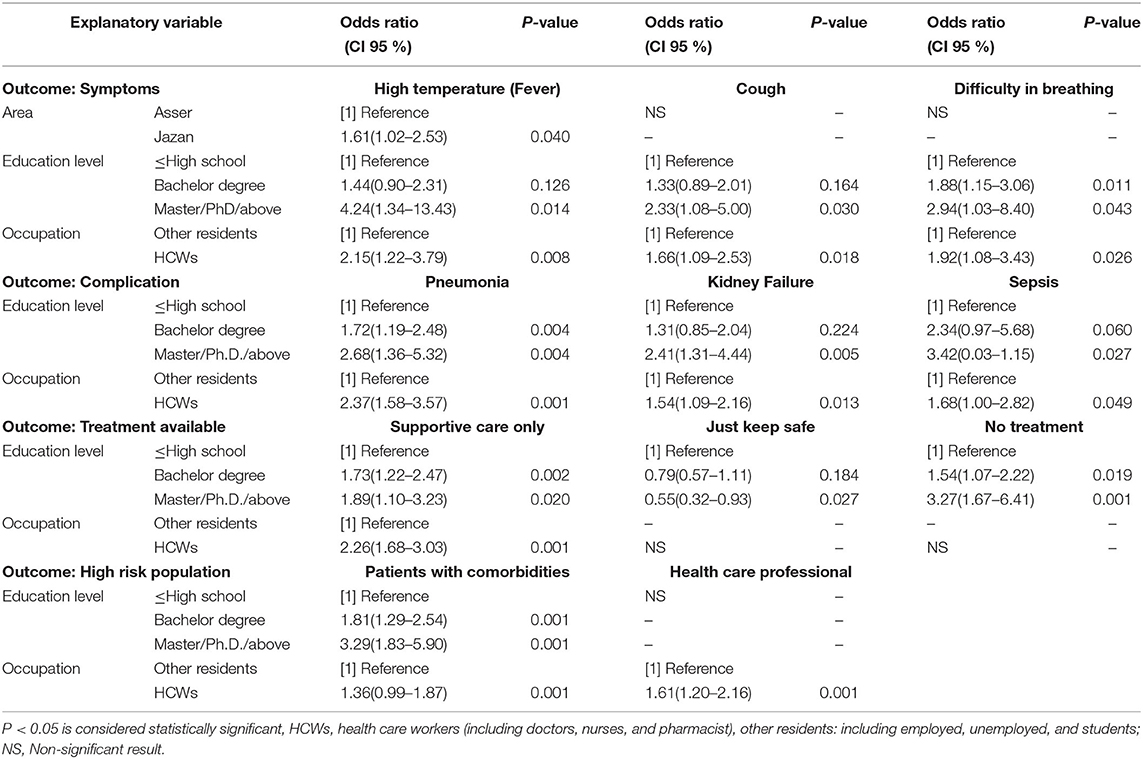

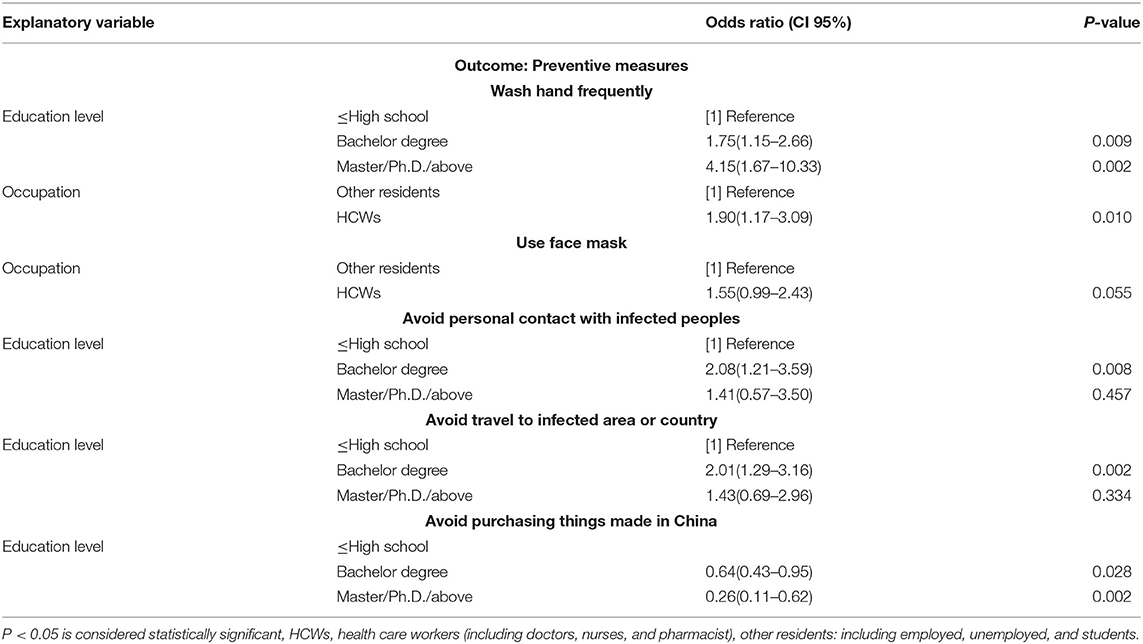

Results: Among 1,000 participants, 36.7% were HCWs, 53.9% were female, and 44.1% were aged ≥ 30 years. Majority of respondents showed awareness of COVID-19 (98.7%) as a deadly, contagious, and life-threatening disease (99.6%) that is transmitted through human-to-human contact (97.7%). They were familiar with the associated symptoms and common causes of COVID-19. Health organizations were chosen as the most reliable source of information by majority of the participants (89.6%). Hand hygiene (92.7%) and social distancing (92.3%) were the most common preventive measures taken by respondents that were followed by avoiding traveling (86.9%) to an infected area or country and wearing face masks (86.5%). Significant proportions of HCWs ( P < 0.05) and more educated participants ( P < 0.05) showed considerable knowledge of the disease, and all respondents displayed good preparedness for the prevention and control of COVID-19. Age, gender, and area were non-significant predictors of COVID-19 awareness.

Conclusion: As the global threat of COVID-19 continues to emerge, it is critical to improve the awareness and preparedness of the targeted community members, especially the less educated ones. Educational interventions are urgently needed to reach the targeted residents beyond borders and further measures are warranted. The outcome of this study highlighted a growing need for the adoption of innovative local strategies to improve awareness in general population related to COVID-19 and its preventative practices in order to meet its elimination goals.

Introduction

An ongoing outbreak of infection by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), termed as COVID-19, aroused the attention of the entire world. The first infected case of coronavirus was reported on December 31, 2019, in Wuhan, China; within few weeks, infections spread across China and to other countries around the world ( 1 ). On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus outbreak a public health emergency of international concern, which was the 6th declaration of its kind in WHO history ( 2 , 3 ). Surprisingly, during the first week of March 2020, devastating numbers of new cases were reported globally, and the WHO declared the COVID-19 outbreak a “pandemic” on March 11 ( 4 , 5 ). The outbreak has now spread to more than 200 countries, areas, or territories beyond China ( 6 ). SARS-CoV-2 is a novel strain of the coronavirus family that has not been previously identified in humans ( 7 ). The disease spreads through person-to-person contact, and the posed potential public health threat is very high. Estimates indicated that COVID-19 could cost the world more than $10 trillion, although considerable uncertainty exists concerning the reach of the virus and the efficacy of the policy response ( 8 ).

The scientists still have limited information about COVID-19, and as a result, the complete clinical picture of COVID-19 is not fully understood yet. Based on currently available information, COVID-19 is a highly contagious disease and its primary clinical symptoms include fever, dry cough, difficulty in breathing, fatigue, myalgia and dyspnea ( 9 – 11 ). This coronavirus spreads primarily through respiratory droplets of >5–10 μm in diameter, discharge from the mouth or nose, when an infected person coughs or sneezes ( 12 , 13 ). Reported illnesses range from very mild (including asymptomatic) to severe including illness resulting to death. However, the information so far suggested the symptoms as mild in almost 80% of the patients with lower death rates. People with co-morbidities, including diabetes and hypertension, who are treated with the drugs such as thiazolidinediones, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs) have an increased expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2). Since, SARS-CoV-2 binds to their target cells through ACE-2, it was suggested that patients with cardiac disease, hypertension, and diabetes are at the higher risk of developing severe to fatal COVID-19 ( 14 , 15 ). Moreover, elderly people (≥65 years), those and people with chronic lung disease or moderate to severe asthma, who are immunocompromised (due to cancer treatment, bone marrow or organ transplant, AIDS, and prolonged use of corticosteroids or other medications), and those people with severe obesity and chronic liver or kidney disease are at higher risk of developing the COVID-19 severe illness ( 16 – 18 ).

Although, no specific vaccine or treatment is approved for COVID-19, yet several treatment regimens prescribed under different conditions are reported to control the severity and mortality rates up to some extent with few adverse effects, though further evidence is needed ( 19 ). Recently, results of ongoing trials aiming at drug repurposing for the disease have been reported, and several drugs have shown encouraging activity as far as reducing the viral load or the duration of therapy is concerned. Remdesivir is one such antiviral drug, and it has reduced the duration of therapy to 11 days in comparison to 15 days in the case of patients receiving standard care only. Therefore, the USFDA has granted the emergency use authorization (EUA) to Remdesivir for the treatment of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases ( 20 , 21 ); however, further investigations are required to collect the sufficient data ( 22 ). Favipiravir (Avigan) is another drug that has exhibited promising activity in significantly reducing the viral load in comparison to standard care in several trials ( 23 ). Apart from antiviral drugs, convalescent plasma for COVID-19 (as passive antibody therapy) has also been tested, proving to be of possible benefit in severely ill COVID-19 patients. However, it requires more clinical trials to be established for the optimal conditions of COVID-19 and as antibody therapy in this disease ( 24 – 26 ). Mono, and Sarilumab which are immunosuppressants and are humanized antibodies against the interleukin-6 receptor, were also tested on severely ill patients of COVID-19. They effectively improved the clinical symptoms and suppressed the worsening of acute COVID-19 patients and reduced the mortality rate ( 27 , 28 ). Very recently, a corticosteroid, Dexamethasone, has been reported to be a life-saving drug that reduced the incidences of deaths by one-third among patients critically ill with COVID-19 ( 29 ) requiring oxygen support.

So far, more than 9 million confirmed cases of COVID- 19 infections have been identified globally with more than 0.46 million confirmed deaths (as on June 21, 2020). Saudi Arabia has also been seriously affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and reported its first confirmed case on March 3, 2020. The numbers are continuously increasing and reached 157,612 on June 21, 2020, with 1,267 confirmed deaths all over the kingdom ( 30 , 31 ) having reproduction number from 2.87 to 4.9 ( 32 ). Before the emergence of COVID-19, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was the major concern in 2012 ( 33 ), though it was successfully controlled in Saudi Arabia. In response to the growing public health threat posed by COVID-19, the Saudi government adopted some unprecedented measures related to awareness and prevention in order to control COVID-19 transmission in the country. These measures included the closure of schools, universities, public transportation, and all public places as well as the isolation and care for infected and suspected cases ( 34 ). On March 9, 2020, government authorities announced the lockdown of the whole country and released advice for Saudi nationals and residents present inside or outside of country to stay at home and maintain social distancing. Moreover, the Saudi government decided to suspend congregational prayers across all mosques in the kingdom, including the two holy mosques in Makkah and Madinah ( 35 ).

The fight against COVID-19 continues globally, and to guarantee success, people's adherence to preventive measures is essential. It is mostly affected by their awareness and preparedness toward COVID-19. Knowledge and attitudes toward infectious diseases are often associated with the level of panic among the population, which could further complicate the measures taken to prevent the spread of the disease. As “natural hazards are inevitable; the disaster is not,” ( 36 ) to facilitate the management of the COVID-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia, there is an urgent need to understand the public's awareness and preparedness for COVID-19 during this challenging time. The present study assessed the awareness and preparedness toward COVID-19 among South Western Saudi residents during the early rapid rise of the COVID-19 outbreak. It included HCWs (doctors, nurses, and community pharmacists) and other members of the community, including the employed, unemployed, as well as students.

Subjects and Methods

Setting and population.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted between March 18 and March 25—the week immediately after the announcement of lockdown in Saudi Arabia. For this study, two highly populated regions (Jazan and Aseer) of South-West Saudi Arabia and adjacent rural villages were selected. All Saudi citizens and residents, males and females of age 12 years or more (including HCWs and other community peoples), who were willing to participate in the study irrespective of COVID-19 infection status were included in the study. People who did not meet the above inclusion criteria were not eligible and were thus excluded from the study.

Sample Size

The required sample size for this study was calculated using a Denial equation ( 37 ) where the significance level (alpha) was set to 0.05 and power (1-β) was set to 0.80. It resulted in a required final sample size of 384 individuals. Therefore, to minimize the errors, the sample size taken for this study was 1,000.

Outcome Measures

The present study examined the level of awareness and preparedness toward prevention of COVID-19 using area, gender, age, education level, and occupation as explanatory variables among the residents (HCWs and other community peoples) of South-West Saudi Arabia.

Since this is a novel coronavirus with no such study having been conducted before, a standardized (structured, pre-coded, and validated) questionnaire was developed for this study by our co-authors, and it is based on frequently asked questions (FAQ) found on Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and WHO official websites ( 38 , 39 ). The questions were multiple choice and sought to gain insight into the respondent's awareness and preparedness toward COVID-19. A pilot survey of 10 individuals was undertaken first to ensure that the questions elicited appropriate response and there were no problems with the entry of answers into the database. Since, it was not feasible to conduct a community-based national sampling survey during this critical period; we decided to collect the data online through a Google survey. The self-reported questionnaire is divided into three sections. The first part is designed to obtain background information, including demographic characteristics (nationality, age, gender, level of educational, and occupation). The second part of the survey consists of questions that address awareness concerning COVID-19 (reliable source of information, symptoms, mode of transmission, incubation period, complications, high-risk population, treatment, and preventive measures). The third part of the survey consists of questions that address the preparedness to fight against COVID-19. The questionnaire is designed in English, being subsequently translated into Arabic for the convenience and ease of understanding of the participants, and it was pre-tested to ensure that it maintained its original meaning.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected using a random sampling method and analyzed using the statistical software Stata 15. For categorical variables, data were presented as frequencies and percentages. A chi-squared (χ 2 ) test was used to examine the association between each item in awareness and explanatory variable in the bivariate analysis. Multivariable logistic regression was computed using each item in awareness and preparedness as an outcome separately to examine the relationships in the adjusted analysis. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol and procedures of informed consent were granted ethical approval by the “Institutional Research Review and Ethics Committee (IRREC), College of Pharmacy, Jazan University” before the formal survey was conducted. Since this study was conducted during the lockdown period, a Google survey was prepared with an online informed consent form on the first page. Participants are informed about the contents of the questionnaire, and they have to answer a yes/no question to confirm their willingness to participate voluntarily. In case of minors (participants below 16 years of age), they are asked to show the form to their parents/guardians before selecting their answer. The patients/participants or their legal guardians have to provide their written informed consent to participate in this study. After an affirmative response of the question, the participant is directed to complete the self-report questionnaire. All responses are anonymous.

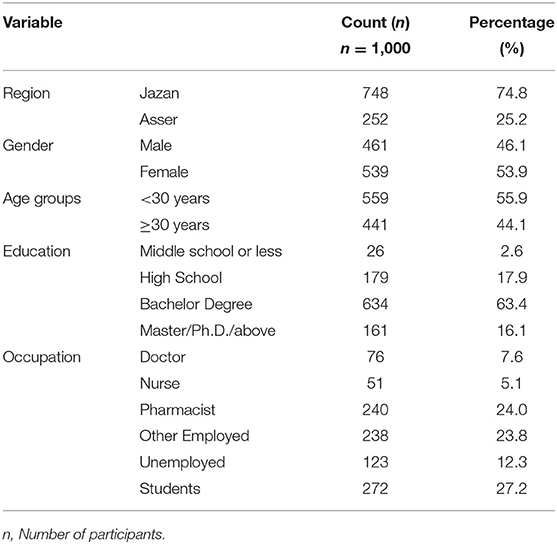

Demographic Characteristics