VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 23, 2022

How to Write a Poem: Get Tips from a Published Poet

Ever wondered how to write a poem? For writers who want to dig deep, composing verse lets you sift the sand of your experience for new glimmers of insight. And if you’re in it for less lofty reasons, shaping a stanza from start to finish can teach you to have fun with language in totally new ways.

To help demystify the subtle art of writing verse, we chatted with Reedsy editor (and published poet) Lauren Stroh . In 8 simple steps, here's how to write a poem:

1. Brainstorm your starting point

2. free-write in prose first, 3. choose your poem’s form and style, 4. read for inspiration, 5. write for an audience of one — you, 6. read your poem out loud, 7. take a break to refresh your mind, 8. have fun revising your poem.

If you’re struggling to write your poem in order from the first line to the last, a good trick is opening with whichever starting point your brain can latch onto as it learns to think in verse.

Your starting point can be a line or a phrase you want to work into your poem, though it doesn’t have to take the form of language at all. It might be a picture in your head, as particular as the curl of hair over your daughter’s ear as she sleeps, or as capacious as the sea. It can even be a complicated feeling you want to render with precision — or maybe it's a memory you return to again and again. Think of this starting point as the "why" behind your poem, your impetus for writing it in the first place.

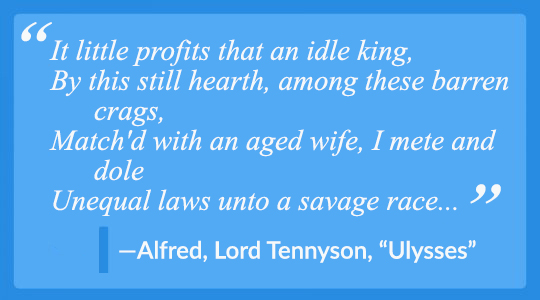

If you’re worried your starting point isn’t grand enough to merit an entire poem, stop right there. After all, literary giants have wrung verse out of every topic under the sun, from the disappointments of a post- Odyssey Odysseus to illicitly eaten refrigerated plums .

As Lauren Stroh sees it, your experience is more than worthy of being immortalized in verse.

"I think the most successful poems articulate something true about the human experience and help us look at the everyday world in new and exciting ways."

It may seem counterintuitive but if you struggle to write down lines that resonate, perhaps start with some prose writing first. Take this time to delve into the image, feeling, or theme at the heart of your poem, and learn to pin it down with language. Give yourself a chance to mull things over before actually writing the poem.

Take 10 minutes and jot down anything that comes to mind when you think of your starting point. You can write in paragraphs, dash off bullet points, or even sketch out a mind map . The purpose of this exercise isn’t to produce an outline: it’s to generate a trove of raw material, a repertoire of loosely connected fragments to draw upon as you draft your poem in earnest.

Silence your inner critic for now

And since this is raw material, the last thing you should do is censor yourself. Catch yourself scoffing at a turn of phrase, overthinking a rhetorical device , or mentally grousing, “This metaphor will never make it into the final draft”? Tell that inner critic to hush for now and jot it down anyway. You just might be able to refine that slapdash, off-the-cuff idea into a sharp and poignant line.

Whether you’ve free-written your way to a beginning or you’ve got a couple of lines jotted down, before you complete a whole first draft of your poem, take some time to think about form and style.

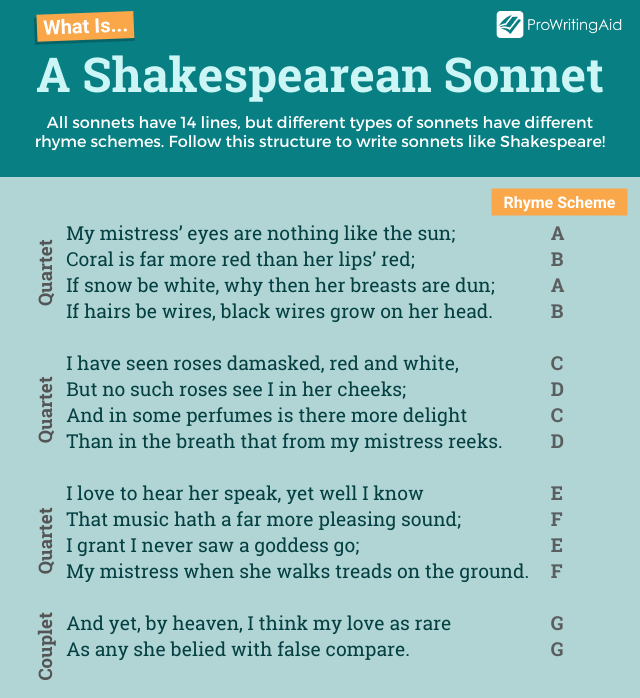

The form of a poem often carries a lot of meaning beyond the structural "rules" that it offers the writer. The rhyme patterns of sonnets — and the Shakespearean influence over the form — usually lend themselves to passionate pronouncements of love, whether merry or bleak. On the other hand, acrostic poems are often more cheeky because of the secret meaning that it hides in plain sight.

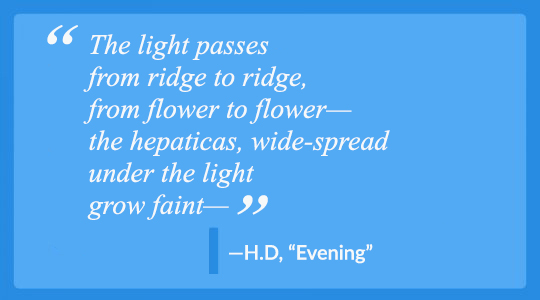

Even if your material begs for a poem without formal restrictions, you’ll still have to decide on the texture and tone of your language. Free verse, after all, is as diverse a form as the novel, ranging from the breathless maximalism of Walt Whitman to the cool austerity of H.D . Where, on this spectrum, will your poem fall?

Choosing a form and tone for your poem early on can help you work with some kind of structure to imbue more meanings to your lines. And if you’ve used free-writing to generate some raw material for yourself, a structure can give you the guidance you need to organize your notes into a poem.

A poem isn’t a nonfiction book or a historical novel: you don’t have to accumulate reams of research to write a good one. That said, a little bit of outside reading can stave off writer’s block and keep you inspired throughout the writing process.

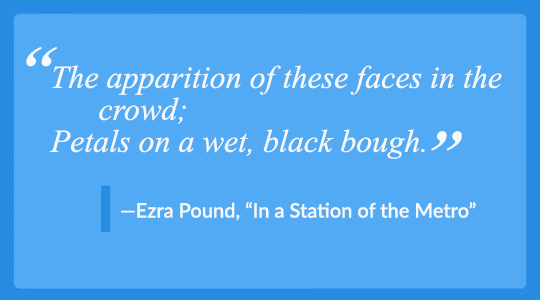

Build a short, personalized syllabus around your poem’s form and subject. Say you’re writing a sensorily rich, linguistically spare bit of free verse about a relationship of mutual jealousy between mother and daughter. In that case, you’ll want to read some key Imagist poems , alongside some poems that sketch out complicated visions of parenthood in unsentimental terms.

And if you don’t want to limit yourself to poems similar in form and style to your own, Lauren has you covered with an all-purpose reading list:

- The Dream of a Common Languag e by Adrienne Rich

- Anything you can get your hands on by Mary Oliver

- The poems “ Failures in Infinitives ” and “ Fish & Chips ” by Bernadette Mayer.

- I often gift Lunch Poems by Frank O’Hara to friends who write.

- Everyone should read the interviews from the Paris Review’s archives . It’s just nice to observe how people familiar with language talk when they’re not performing, working, or warming up to write.

Even with preparation, the pressure of actually producing verse can still awaken your inner metrophobe (or poetry-fearer). What if people don’t understand — or even misinterpret — what you’re trying to say? What if they don’t feel drawn to your work? To keep the anxiety at bay, Lauren suggests writing for yourself, not for an external audience.

"I absolutely believe that poets can determine the validity of their own success if they are changed by the work they are producing themselves; if they are challenged by it; or if it calls into question their ethics, their habits, or their relationship to the living world. And personally, my life has certainly been changed by certain lines I’ve had the bravery to think and then write — and those moments are when I’ve felt most like I’ve made it."

You might eventually polish your work if you decide to publish your poetry down the line. (If you do, definitely check out the rest of this guide for tips and a list of magazines to submit to.) But as your first draft comes together, treat it like it’s meant for your eyes only.

A good poem doesn’t have to be pretty: maybe an easy, melodic loveliness isn’t your aim. It should, however, come alive on the page with a consciously crafted rhythm, whether hymn-like or discordant. To achieve that, read your poem out loud — at first, line by line, and then all together, as a complete text.

Trying out every line against your ear can help you weigh out a choice between synonyms — getting you to notice, say, the watery sound of “glacial”, the brittleness of “icy,” the solidity of “cold”.

Reading out loud can also help you troubleshoot line breaks that just don't feel right. Is the line unnaturally long, forcing you to rush through it or pause in the middle for a hurried inhale? If so, do you like that destabilizing effect, or do you want to literally give the reader some room to breathe? Testing these variations aloud is perhaps the only way to answer questions like these.

While it’s incredibly exciting to complete a draft of your poem, and you might be itching to dive back in and edit it, it’s always advisable to take a break first. You don’t have to turn completely away from writing if you don’t want to. Take a week to chip away at your novel or even muse idly on your next poetic project — so long as you distance yourself from this poem a little while.

This is because, by this point, you’ve probably read out every line so many times the meaning has leached out of the syllables. With the time away, you let your mind refresh so that you can approach the piece with sharper attention and more ideas to refine it.

At the end of the day, even if you write in a well-established form, poetry is about experimenting with language, both written and spoken. Lauren emphasizes that revising a poem is thus an open-ended process that requires patience — and a sense of play.

"Have fun. Play. Be patient. Don’t take it seriously, or do. Though poems may look shorter than what you’re used to writing, they often take years to be what they really are. They change and evolve. The most important thing is to find a quiet place where you can be with yourself and really listen."

Is it time to get other people involved?

Want another pair of eyes on your poem during this process? You have options. You can swap pieces with a beta reader , workshop it with a critique group , or even engage a professional poetry editor like Lauren to refine your work — a strong option if you plan to submit it to a journal or turn it into the foundation for a chapbook .

Want a poetry expert to polish up your verse?

Professional poetry editors are on Reedsy. Sign up for free to meet them!

Learn how Reedsy can help you craft a beautiful book.

The working poet's checklist

If you decide to fly solo, here’s a checklist to work through as you revise:

✅ Hunt for clichés. Did you find yourself reaching for ready-made idioms at any point? Go back to the sentiment you were grappling with and try to capture it in stronger, more vivid terms.

✅ See if your poem begins where it should. Did you take a few lines of throat-clearing to get to the actual point? Try starting your poem further down.

✅ Make sure every line belongs. As you read each line, ask yourself: how does this contribute to the poem as a whole? Does it advance the theme, clarify the imagery, set or subvert the reader’s expectations? If you answer with something like, “It makes the poem sound nice,” consider cutting it.

Once you’ve worked your way through this checklist, feel free to brew yourself a cup of tea and sit quietly for a while, reflecting on your literary triumphs.

Whether these poetry writing tips have awakened your inner Wordsworth, or sent you happily gamboling back to prose, we hope you enjoyed playing with poetry — and that you learned something new about your approach to language.

And if you are looking to share your poetry with the world, the next post in this guide can show the ropes regarding how to publish your poems!

Anna Clarke says:

29/03/2020 – 04:37

I entered a short story competition and though I did not medal, one of the judges told me that some of my prose is very poetic. The following year I entered a poetry competition and won a bronze medal. That was my first attempt at writing poetry. I am more aware of figurative language in writing prose now. I am learning to marry the two. I don't have any poems online.

Comments are currently closed.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Free Course: Spark Creativity With Poetry

Learn to harness the magic of poetry and enhance your writing.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

To learn how to write a poem step-by-step, let’s start where all poets start: the basics.

This article is an in-depth introduction to how to write a poem. We first answer the question, “What is poetry?” We then discuss the literary elements of poetry, and showcase some different approaches to the writing process—including our own seven-step process on how to write a poem step by step.

So, how do you write a poem? Let’s start with what poetry is.

How to Write a Poem: Contents

What Poetry Is

- Literary Devices

How to Write a Poem, in 7 Steps

How to write a poem: different approaches and philosophies.

- Okay, I Know How to Write a Good Poem. What Next?

It’s important to know what poetry is—and isn’t—before we discuss how to write a poem. The following quote defines poetry nicely:

“Poetry is language at its most distilled and most powerful.” —Former US Poet Laureate Rita Dove

Poetry Conveys Feeling

People sometimes imagine poetry as stuffy, abstract, and difficult to understand. Some poetry may be this way, but in reality poetry isn’t about being obscure or confusing. Poetry is a lyrical, emotive method of self-expression, using the elements of poetry to highlight feelings and ideas.

A poem should make the reader feel something.

In other words, a poem should make the reader feel something—not by telling them what to feel, but by evoking feeling directly.

Here’s a contemporary poem that, despite its simplicity (or perhaps because of its simplicity), conveys heartfelt emotion.

Poem by Langston Hughes

I loved my friend. He went away from me. There’s nothing more to say. The poem ends, Soft as it began— I loved my friend.

Poetry is Language at its Richest and Most Condensed

Unlike longer prose writing (such as a short story, memoir, or novel), poetry needs to impact the reader in the richest and most condensed way possible. Here’s a famous quote that enforces that distinction:

“Prose: words in their best order; poetry: the best words in the best order.” —Samuel Taylor Coleridge

So poetry isn’t the place to be filling in long backstories or doing leisurely scene-setting. In poetry, every single word carries maximum impact.

Poetry Uses Unique Elements

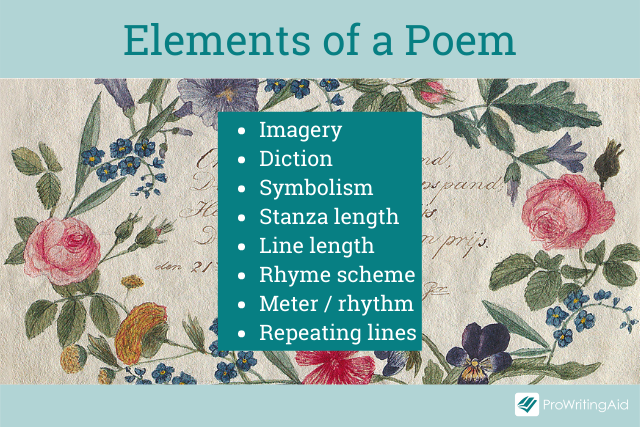

Poetry is not like other kinds of writing: it has its own unique forms, tools, and principles. Together, these elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

The elements of poetry help it to powerfully impact the reader in only a few words.

Most poetry is written in verse , rather than prose . This means that it uses line breaks, alongside rhythm or meter, to convey something to the reader. Rather than letting the text break at the end of the page (as prose does), verse emphasizes language through line breaks.

Poetry further accentuates its use of language through rhyme and meter. Poetry has a heightened emphasis on the musicality of language itself: its sounds and rhythms, and the feelings they carry.

These devices—rhyme, meter, and line breaks—are just a few of the essential elements of poetry, which we’ll explore in more depth now.

Understanding the Elements of Poetry

As we explore how to write a poem step by step, these three major literary elements of poetry should sit in the back of your mind:

- Rhythm (Sound, Rhyme, and Meter)

1. Elements of Poetry: Rhythm

“Rhythm” refers to the lyrical, sonic qualities of the poem. How does the poem move and breathe; how does it feel on the tongue?

Traditionally, poets relied on rhyme and meter to accomplish a rhythmically sound poem. Free verse poems —which are poems that don’t require a specific length, rhyme scheme, or meter—only became popular in the West in the 20th century, so while rhyme and meter aren’t requirements of modern poetry, they are required of certain poetry forms.

Poetry is capable of evoking certain emotions based solely on the sounds it uses. Words can sound sinister, percussive, fluid, cheerful, dour, or any other noise/emotion in the complex tapestry of human feeling.

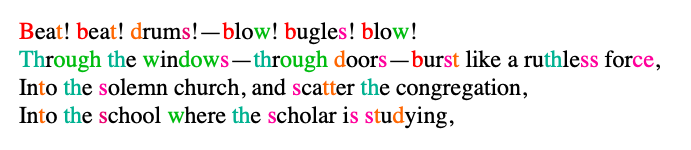

Take, for example, this excerpt from the poem “Beat! Beat! Drums!” by Walt Whitman:

Red — “b” sounds

Blue — “th” sounds

Green — “w” and “ew” sounds

Purple — “s” sounds

Orange — “d” and “t” sounds

This poem has a lot of percussive, disruptive sounds that reinforce the beating of the drums. The “b,” “d,” “w,” and “t” sounds resemble these drum beats, while the “th” and “s” sounds are sneakier, penetrating a deeper part of the ear. The cacophony of this excerpt might not sound “lyrical,” but it does manage to command your attention, much like drums beating through a city might sound.

To learn more about consonance and assonance, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia , and the other uses of sound, take a look at our article “12 Literary Devices in Poetry.”

https://writers.com/literary-devices-in-poetry

It would be a crime if you weren’t primed on the ins and outs of rhymes. “Rhyme” refers to words that have similar pronunciations, like this set of words: sound, hound, browned, pound, found, around.

Many poets assume that their poetry has to rhyme, and it’s true that some poems require a complex rhyme scheme. However, rhyme isn’t nearly as important to poetry as it used to be. Most traditional poetry forms—sonnets, villanelles , rimes royal, etc.—rely on rhyme, but contemporary poetry has largely strayed from the strict rhyme schemes of yesterday.

There are three types of rhymes:

- Homophony: Homophones are words that are spelled differently but sound the same, like “tail” and “tale.” Homophones often lead to commonly misspelled words .

- Perfect Rhyme: Perfect rhymes are word pairs that are identical in sound except for one minor difference. Examples include “slant and pant,” “great and fate,” and “shower and power.”

- Slant Rhyme: Slant rhymes are word pairs that use the same sounds, but their final vowels have different pronunciations. For example, “abut” and “about” are nearly-identical in sound, but are pronounced differently enough that they don’t completely rhyme. This is also known as an oblique rhyme or imperfect rhyme.

Meter refers to the stress patterns of words. Certain poetry forms require that the words in the poem follow a certain stress pattern, meaning some syllables are stressed and others are unstressed.

What is “stressed” and “unstressed”? A stressed syllable is the sound that you emphasize in a word. The bolded syllables in the following words are stressed, and the unbolded syllables are unstressed:

- Un• stressed

- Plat• i• tud• i•nous

- De •act•i• vate

- Con• sti •tu• tion•al

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables is important to traditional poetry forms. This chart, copied from our article on form in poetry , summarizes the different stress patterns of poetry.

2. Elements of Poetry: Form

“Form” refers to the structure of the poem. Is the poem a sonnet , a villanelle, a free verse piece, a slam poem, a contrapuntal, a ghazal , a blackout poem , or something new and experimental?

Form also refers to the line breaks and stanza breaks in a poem. Unlike prose, where the end of the page decides the line breaks, poets have control over when one line ends and a new one begins. The words that begin and end each line will emphasize the sounds, images, and ideas that are important to the poet.

To learn more about rhyme, meter, and poetry forms, read our full article on the topic:

https://writers.com/what-is-form-in-poetry

3. Elements of Poetry: Literary Devices

“Poetry: the best words in the best order.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

How does poetry express complex ideas in concise, lyrical language? Literary devices—like metaphor, symbolism , juxtaposition , irony , and hyperbole—help make poetry possible. Learn how to write and master these devices here:

https://writers.com/common-literary-devices

To condense the elements of poetry into an actual poem, we’re going to follow a seven-step approach. However, it’s important to know that every poet’s process is different. While the steps presented here are a logical path to get from idea to finished poem, they’re not the only tried-and-true method of poetry writing. Poets can—and should!—modify these steps and generate their own writing process.

Nonetheless, if you’re new to writing poetry or want to explore a different writing process, try your hand at our approach. Here’s how to write a poem step by step!

1. Devise a Topic

The easiest way to start writing a poem is to begin with a topic.

However, devising a topic is often the hardest part. What should your poem be about? And where can you find ideas?

Here are a few places to search for inspiration:

- Other Works of Literature: Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum—it’s part of a larger literary tapestry, and can absolutely be influenced by other works. For example, read “The Golden Shovel” by Terrance Hayes , a poem that was inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool.”

- Real-World Events: Poetry, especially contemporary poetry, has the power to convey new and transformative ideas about the world. Take the poem “A Cigarette” by Ilya Kaminsky , which finds community in a warzone like the eye of a hurricane.

- Your Life: What would poetry be if not a form of memoir? Many contemporary poets have documented their lives in verse. Take Sylvia Plath’s poem “Full Fathom Five” —a daring poem for its time, as few writers so boldly criticized their family as Plath did.

- The Everyday and Mundane: Poetry isn’t just about big, earth-shattering events: much can be said about mundane events, too. Take “Ode to Shea Butter” by Angel Nafis , a poem that celebrates the beautiful “everydayness” of moisturizing.

- Nature: The Earth has always been a source of inspiration for poets, both today and in antiquity. Take “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver , which finds meaning in nature’s quiet rituals.

- Writing Exercises: Prompts and exercises can help spark your creativity, even if the poem you write has nothing to do with the prompt! Here’s 24 writing exercises to get you started.

At this point, you’ve got a topic for your poem. Maybe it’s a topic you’re passionate about, and the words pour from your pen and align themselves into a perfect sonnet! It’s not impossible—most poets have a couple of poems that seemed to write themselves.

However, it’s far more likely you’re searching for the words to talk about this topic. This is where journaling comes in.

Sit in front of a blank piece of paper, with nothing but the topic written on the top. Set a timer for 15-30 minutes and put down all of your thoughts related to the topic. Don’t stop and think for too long, and try not to obsess over finding the right words: what matters here is emotion, the way your subconscious grapples with the topic.

At the end of this journaling session, go back through everything you wrote, and highlight whatever seems important to you: well-written phrases, poignant moments of emotion, even specific words that you want to use in your poem.

Journaling is a low-risk way of exploring your topic without feeling pressured to make it sound poetic. “Sounding poetic” will only leave you with empty language: your journal allows you to speak from the heart. Everything you need for your poem is already inside of you, the journaling process just helps bring it out!

Learn more about keeping a daily journal here:

How to Start Journaling: Practical Advice on How to Journal Daily

3. Think About Form

As one of the elements of poetry, form plays a crucial role in how the poem is both written and read. Have you ever wanted to write a sestina ? How about a contrapuntal, or a double cinquain, or a series of tanka? Your poem can take a multitude of forms, including the beautifully unstructured free verse form; while form can be decided in the editing process, it doesn’t hurt to think about it now.

4. Write the First Line

After a productive journaling session, you’ll be much more acquainted with the state of your heart. You might have a line in your journal that you really want to begin with, or you might want to start fresh and refer back to your journal when you need to! Either way, it’s time to begin.

What should the first line of your poem be? There’s no strict rule here—you don’t have to start your poem with a certain image or literary device. However, here’s a few ways that poets often begin their work:

- Set the Scene: Poetry can tell stories just like prose does. Anne Carson does just this in her poem “Lines,” situating the scene in a conversation with the speaker’s mother.

- Start at the Conflict : Right away, tell the reader where it hurts most. Margaret Atwood does this in “Ghost Cat,” a poem about aging.

- Start With a Contradiction: Juxtaposition and contrast are two powerful tools in the poet’s toolkit. Joan Larkin’s poem “Want” begins and ends with these devices. Carlos Gimenez Smith also begins his poem “Entanglement” with a juxtaposition.

- Start With Your Title: Some poets will use the title as their first line, like Ron Padgett’s poem “Ladies and Gentlemen in Outer Space.”

There are many other ways to begin poems, so play around with different literary devices, and when you’re stuck, turn to other poetry for inspiration.

5. Develop Ideas and Devices

You might not know where your poem is going until you finish writing it. In the meantime, stick to your literary devices. Avoid using too many abstract nouns, develop striking images, use metaphors and similes to strike interesting comparisons, and above all, speak from the heart.

6. Write the Closing Line

Some poems end “full circle,” meaning that the images the poet used in the beginning are reintroduced at the end. Gwendolyn Brooks does this in her poem “my dreams, my work, must wait till after hell.”

Yet, many poets don’t realize what their poems are about until they write the ending line . Poetry is a search for truth, especially the hard truths that aren’t easily explained in casual speech. Your poem, too, might not be finished until it comes across a necessary truth, so write until you strike the heart of what you feel, and the poem will come to its own conclusion.

7. Edit, Edit, Edit!

Do you have a working first draft of your poem? Congratulations! Getting your feelings onto the page is a feat in itself.

Yet, no guide on how to write a poem is complete without a note on editing. If you plan on sharing or publishing your work, or if you simply want to edit your poem to near-perfection, keep these tips in mind.

- Adjectives and Adverbs: Use these parts of speech sparingly. Most imagery shouldn’t rely on adjectives and adverbs, because the image should be striking and vivid on its own, without too much help from excess language.

- Concrete Line Breaks: Line breaks help emphasize important words, making certain images and themes clearer to the reader. As a general rule, most of your lines should start and end with concrete words—nouns and verbs especially.

- Stanza Breaks: Stanzas are like paragraphs to poetry. A stanza can develop a new idea, contrast an existing idea, or signal a transition in the poem’s tone. Make sure each stanza clearly stands for something as a unit of the poem.

- Mixed Metaphors: A mixed metaphor is when two metaphors occupy the same idea, making the poem unnecessarily difficult to understand. Here’s an example of a mixed metaphor: “a watched clock never boils.” The meaning can be discerned, but the image remains unclear. Be wary of mixed metaphors—though some poets (like Shakespeare) make them work, they’re tricky and often disruptive.

- Abstractions: Above all, avoid using excessively abstract language. It’s fine to use the word “love” 2 or 3 times in a poem, but don’t use it twice in every stanza. Let the imagery in your poem express your feelings and ideas, and only use abstractions as brief connective tissue in otherwise-concrete writing.

Lastly, don’t feel pressured to “do something” with your poem. Not all poems need to be shared and edited. Poetry doesn’t have to be “good,” either—it can simply be a statement of emotions by the poet, for the poet. Publishing is an admirable goal, but also, give yourself permission to write bad poems, unedited poems, abstract poems, and poems with an audience of one. Write for yourself—editing is for the other readers.

Poetry is the oldest literary form, pre-dating prose, theater, and the written word itself. As such, there are many different schools of thought when it comes to writing poetry. You might be wondering how to write a poem through different methods and approaches: here’s four philosophies to get you started.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Emotion

If you asked a Romantic Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the spontaneous emotion of the soul.

The Romantic Era viewed poetry as an extension of human emotion—a way of perceiving the world through unbridled creativity, centered around the human soul. While many Romantic poets used traditional forms in their poetry, the Romantics weren’t afraid to break from tradition, either.

To write like a Romantic, feel—and feel intensely. The words will follow the emotions, as long as a blank page sits in front of you.

How to Write a Poem: Poetry as Stream of Consciousness

If you asked a Modernist poet, “What is poetry?” they would tell you that poetry is the search for complex truths.

Modernist Poets were keen on the use of poetry as a window into the mind. A common technique of the time was “Stream of Consciousness,” which is unfiltered writing that flows directly from the poet’s inner dialogue. By tapping into one’s subconscious, the poet might uncover deeper truths and emotions they were initially unaware of.

Depending on who you are as a writer, Stream of Consciousness can be tricky to master, but this guide covers the basics of how to write using this technique.

How to Write a Poem: Mindfulness

Mindfulness is a practice of documenting the mind, rather than trying to control or edit what it produces. This practice was popularized by the Beat Poets , who in turn were inspired by Eastern philosophies and Buddhist teachings. If you asked a Beat Poet “what is poetry?”, they would tell you that poetry is the human consciousness, unadulterated.

To learn more about the art of leaving your mind alone , take a look at our guide on Mindfulness, from instructor Marc Olmsted.

https://writers.com/mindful-writing

How to Write a Poem: Poem as Camera Lens

Many contemporary poets use poetry as a camera lens, documenting global events and commenting on both politics and injustice. If you find yourself itching to write poetry about the modern day, press your thumb against the pulse of the world and write what you feel.

Additionally, check out these two essays by Electric Literature on the politics of poetry:

- What Can Poetry Do That Politics Can’t?

- Why All Poems Are Political (TL;DR: Poetry is an urgent expression of freedom).

Okay, I Know How to Write a Poem. What Next?

Poetry, like all art forms, takes practice and dedication. You might write a poem you enjoy now, and think it’s awfully written 3 years from now; you might also write some of your best work after reading this guide. Poetry is fickle, but the pen lasts forever, so write poems as long as you can!

Once you understand how to write a poem, and after you’ve drafted some pieces that you’re proud of and ready to share, here are some next steps you can take.

Publish in Literary Journals

Want to see your name in print? These literary journals house some of the best poetry being published today.

https://writers.com/best-places-submit-poetry-online

Assemble and Publish a Manuscript

A poem can tell a story. So can a collection of poems. If you’re interested in publishing a poetry book, learn how to compose and format one here:

https://writers.com/poetry-manuscript-format

How to Write a Poem: Join a Writing Community

Writers.com is an online community of writers, and we’d love it if you shared your poetry with us! Join us on Facebook and check out our upcoming poetry courses .

Poetry doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it exists to educate and uplift society. The world is waiting for your voice, so find a group and share your work!

Sean Glatch

32 comments.

super useful! love these articles 💕

Finally found a helpful guide on Poetry’. For many year, I have written and filed numerous inspired pieces from experiences and moment’s of epiphany. Finally, looking forward to convertinb to ‘poetry format’. THANK YOU, KINDLY. 🙏🏾

Indeed, very helpful, consize. I could not say more than thank you.

I’ve never read a better guide on how to write poetry step by step. Not only does it give great tips, but it also provides helpful links! Thank you so much.

Thank you very much, Hamna! I’m so glad this guide was helpful for you.

Best guide so far

Very inspirational and marvelous tips

Thank you super tips very helpful.

I have never gone through the steps of writing poetry like this, I will take a closer look at your post.

Beautiful! Thank you! I’m really excited to try journaling as a starter step x

[…] How to Write a Poem, Step-by-Step […]

This is really helpful, thanks so much

Extremely thorough! Nice job.

Thank you so much for sharing your awesome tips for beginner writers!

People must reboot this and bookmark it. Your writing and explanation is detailed to the core. Thanks for helping me understand different poetic elements. While reading, actually, I start thinking about how my husband construct his songs and why other artists lack that organization (or desire to be better). Anyway, this gave me clarity.

I’m starting to use poetry as an outlet for my blogs, but I also have to keep in mind I’m transitioning from a blogger to a poetic sweet kitty potato (ha). It’s a unique transition, but I’m so used to writing a lot, it’s strange to see an open blog post with a lot of lines and few paragraphs.

Anyway, thanks again!

I’m happy this article was so helpful, Eternity! Thanks for commenting, and best of luck with your poetry blog.

Yours in verse, Sean

One of the best articles I read on how to write poems. And it is totally step by step process which is easy to read and understand.

Thanks for the step step explanation in how to write poems it’s a very helpful to me and also for everyone one. THANKYOU

Totally detailed and in a simple language told the best way how to write poems. It is a guide that one should read and follow. It gives the detailed guidance about how to write poems. One of the best articles written on how to write poems.

what a guidance thank you so much now i can write a poem thank you again again and again

The most inspirational and informative article I have ever read in the 21st century.It gives the most relevent,practical, comprehensive and effective insights and guides to aspiring writers.

Thank you so much. This is so useful to me a poetry

[…] Write a short story/poem (Here are some tips) […]

It was very helpful and am willing to try it out for my writing Thanks ❤️

Thank you so much. This is so helpful to me, and am willing to try it out for my writing .

Absolutely constructive, direct, and so useful as I’m striving to develop a recent piece. Thank you!

thank you for your explanation……,love it

Really great. Nothing less.

I can’t thank you enough for this, it touched my heart, this was such an encouraging article and I thank you deeply from my heart, I needed to read this.

great teaching Did not know all that in poetry writing

This was very useful! Thank you for writing this.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

5 Tips for Poetry Writing: How to Get Started Writing Poems

Hannah Yang

Poetry is a daunting art form to break into.

There are technically no rules for how to write a poem , but despite that—or perhaps because of it—learning how to write a successful poem might feel more difficult than learning how to write a successful essay or story.

There are many reasons to try your hand at poetry, even if you’re primarily a prose writer. Here are just a few:

- Practice writing stronger descriptions and imagery

- Unlock a new side of your creative writing practice

- Learn how to wield language in a more nuanced way

Learning how to write poetry may seem intimidating, but it doesn’t have to be.

In this article, we’ll cover five of our favorite tips to get started writing poetry.

How Do You Start Writing Poetry?

How do you write a poem from a new perspective, how do you write a meaningful poem, how do you write a poem about a theme, what are some different types of poetry, tip 1: focus on concrete imagery.

One of the best ways to start writing poetry is to use concrete images that appeal to the five senses.

The idea of starting with the specific might feel counterintuitive, because many people think of poetry as a way to describe abstract ideas, such as death, joy, or sorrow.

It certainly can be. But each of these concepts has been written about extensively before. Try sitting down and writing an original poem about joy—it’s hard to find something new to say about it.

If you write about a specific experience you’ve had that made you feel joy, that will almost certainly be unique, because nobody has lived the same experiences you have.

That’s what makes concrete imagery so powerful in poetry.

A concrete image is a detail that has a basis in something real or tangible. It could be the texture of your daughter’s hair as you braid it in the morning, or the smell of a food that reminds you of home.

The more specific the image is, the more vivid and effective the poem will become.

Concrete imagery: Example

Harlem by Langston Hughes

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

Notice how Langston Hughes doesn’t directly write about dreams, except for the very first line. After the first line, he uses concrete images that are very specific and appeal to the five senses: “dry up like a raisin in the sun,” “stink like rotten meat,” “sags like a heavy load.”

He conveys a deeper message about an abstract concept—dreams—using these specific, tangible images.

Concrete Imagery: Exercise

Examine your surroundings. Describe what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell.

Through these concrete images, try to evoke a specific feeling (e.g., nostalgia, boredom, happiness) without ever naming that feeling in the poem.

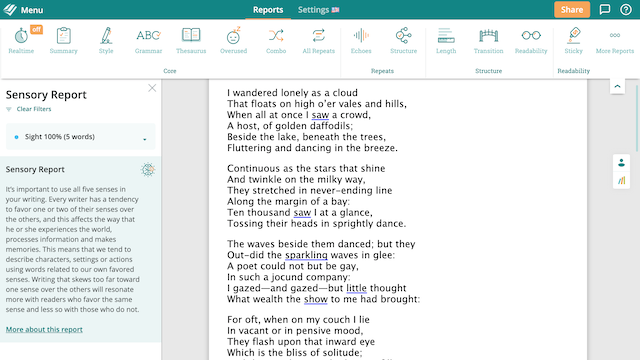

Once you've finished writing, you can use ProWritingAid’s Sensory Check to see which of the five senses you've used the most in your imagery. Most writers favor one or two senses, like in the example below, which can resonate with some readers but alienate others.

Sign up for a free ProWritingAid account to try the Sensory Check.

Bonus Tip: Start with a free verse poem, which is a poem with no set format or rhyme scheme. You can punctuate it the same way you would punctuate normal prose. Free verse is a great option for beginners, because it lets you write freely without limitations.

Tip 2: Play with Perspective

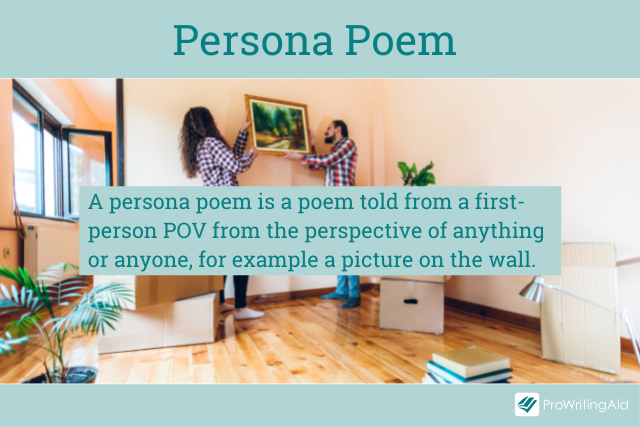

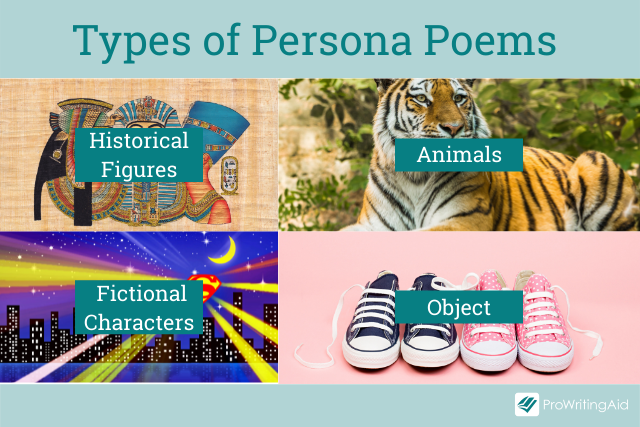

A persona poem is a poem told in the first-person POV (point of view) from the perspective of anything or anyone. This could include a famous person, a figure from mythology, or even an inanimate object.

The word persona comes from the Latin word for mask . When you write a persona poem, it’s like you’re putting on a mask to see the world through a new lens.

If you’re a new poet and you haven’t found your own voice yet, a persona poem is a great way to experiment with a unique style.

Some persona poems are narrative poems, which tell a story from a specific point of view. Others are lyric poems, which focus more on the style and sound of the poem instead of telling a story.

You can write from the perspective of a pop star, a politician, or a figure from fable or myth. You can try to imagine what it feels like to be a pair of jeans or a lawn mower or a fountain pen. There are no limits except your own creativity.

Play with Perspective: Example

Anne Hathaway by Carol Ann Duffy

Item I gyve unto my wief my second best bed … (from Shakespeare’s will)

The bed we loved in was a spinning world of forests, castles, torchlight, cliff-tops, seas where he would dive for pearls. My lover’s words were shooting stars which fell to earth as kisses on these lips; my body now a softer rhyme to his, now echo, assonance; his touch a verb dancing in the centre of a noun. Some nights I dreamed he’d written me, the bed a page beneath his writer’s hands. Romance and drama played by touch, by scent, by taste. In the other bed, the best, our guests dozed on, dribbling their prose. My living laughing love— I hold him in the casket of my widow’s head as he held me upon that next best bed.

In this poem, Carol Ann Duffy writes from the perspective of Anne Hathaway, the wife of William Shakespeare.

She imagines what the wife of this famous literary figure might think and feel, with lines like “Some nights I dreamed he’d written me.”

The poem isn’t written in Shakespearean English, but it uses diction and vocabulary that’s more old-fashioned than the English we speak today, to evoke the feeling of Shakespeare’s time period.

Play with Perspective: Exercise

Write a persona poem from the perspective of a fictional character out of a book or movie. You can tell an important story from their life, or simply try to capture the feeling of being in their head for a moment.

If this character lives in a different time period or speaks in a specific dialect, try to capture that in the poem’s voice.

Tip 3: Write from Life

The best poems are the ones that feel authentic and come from a place of truth.

Brainstorm your own personal experiences. Are there any stories from your life that evoke strong feelings for you? How can you tell that story through a poem?

Try to avoid clichés here. If you want to write about a universal experience or feeling, try to find an entry point into that feeling that’s unique to your life.

Maybe your first hobby was associated with a specific pair of shoes. Maybe your first encounter with shame came from breaking a specific promise to your grandfather. Any of these details could be the launching point for a poem.

Write from Life: Example

Discord in Childhood By D.H. Lawrence

Outside the house an ash-tree hung its terrible whips, And at night when the wind arose, the lash of the tree Shrieked and slashed the wind, as a ship’s Weird rigging in a storm shrieks hideously.

Within the house two voices arose in anger, a slender lash Whistling delirious rage, and the dreadful sound Of a thick lash booming and bruising, until it drowned The other voice in a silence of blood, ’neath the noise of the ash.

Here, D.H. Lawrence writes about the suffering he endured as a child listening to his parents arguing. He channels his own memories and experiences to create a profoundly relatable piece.

Write from Life: Exercise

Go to your phone’s camera roll, or a physical photo album, and find a photo from your life that speaks to you. Write a poem inspired by that photo.

What does that part of your life mean to you? What were your thoughts and feelings at that point in your life?

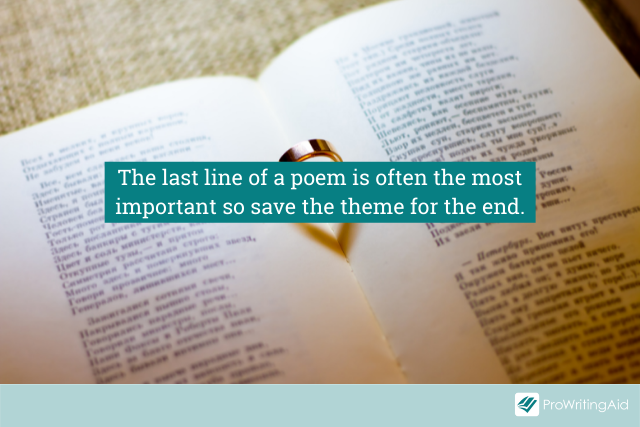

Tip 4: Save the Theme for the End

In a poem, the last line is often the most important. These are the words that echo in your reader’s head after they’re done reading.

Many poems will tell a story or depict a series of images, allowing you to draw your own conclusions about what it’s trying to say, and then conclude with the takeaway at the very end. Think of it like a fable you might tell a child—often, the moral of the story comes at the end.

In sonnets it’s a common trend for the final couplet to summarize the theme of the whole poem.

Save the Theme: Example

Resumé by Dorothy Parker

Razors pain you; Rivers are damp; Acids stain you; And drugs cause cramp. Guns aren’t lawful; Nooses give; Gas smells awful; You might as well live.

Here, Dorothy Parker doesn’t make the poem’s meaning clear until the very last line: “You might as well live.” The poem feels fun, almost like a song, and its true meaning doesn’t become obvious until after you’ve finished reading the poem.

Save the Theme: Exercise

Pick your favorite proverb or adage, such as “Actions speak louder than words.” Write a poem that uses that proverb or adage as the closing line.

Until the closing line, don’t comment on the deeper meaning in the rest of the poem—instead, tell a story that builds up to that theme.

Tip 5: Try a Poetic Form

Up until now, we’ve been writing in blank verse because it’s the most freeing. Sometimes, though, adding limitations can spark creativity too.

You can use a traditional poetic form to create the structure and shape of your poem.

If you have a limited number of lines to use, you’ll concentrate more on being concise and focused. Great poetry is minimalistic—no word is unnecessary. Using a form is a way to practice paring back to the words you absolutely need, and to start thinking about sound and rhyme.

The rules of a poetic form are never set in stone. It’s okay to experiment, and to pick and choose which rules you want to follow. If you want to use a form’s rhyme scheme but ignore its syllable count, for example, that’s perfectly fine.

Let’s look at some examples of poetic forms you can try, and the benefits of each one.

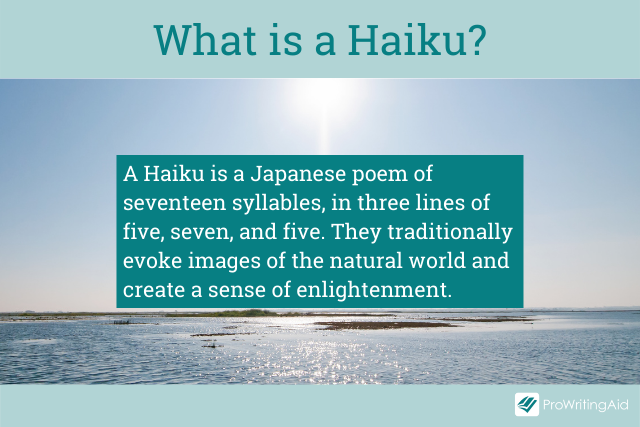

The haiku is a form of Japanese poetry made of three short, unrhymed lines. Traditionally, the first line contains 5 syllables, the second line contains 7 syllables, and the last contains 5 syllables.

Because each haiku must be incredibly concise, this form is a great way to practice economy of language and to learn how to convey a lot with a little. Even more so than with most other poetic forms, you have to think about each word and whether or not it pulls its weight in the poem as a whole.

The Old Pond by Matsuo Bashō

An old silent pond A frog jumps into the pond— Splash! Silence again.

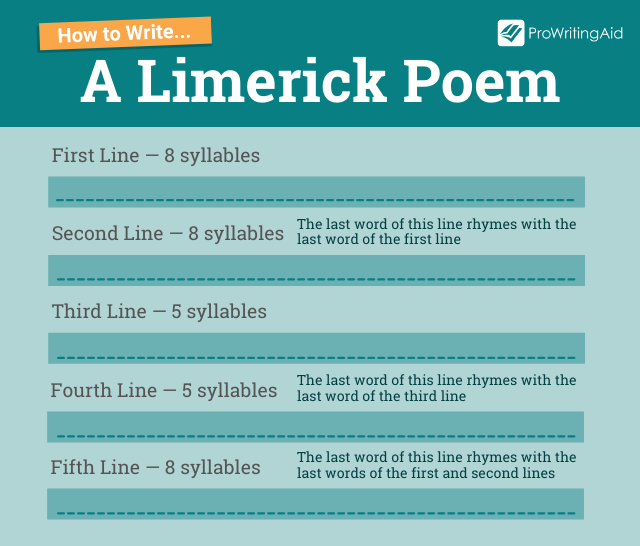

The limerick is a 5-line poem with a sing-songy rhyme scheme and syllable count.

Limericks tend to be humorous and witty, so if you’re usually a comedic writer, they can be a great form for learning how to write poetry. You can treat the poem as a joke that builds up to a punchline.

Untitled Limerick by Edward Lear

There was an Old Man with a beard Who said, "It is just as I feared! Two Owls and a Hen, Four Larks and a Wren, Have all built their nests in my beard!"

The sonnet is a 14-line poetic form, invented in Italy in the 13th century.

There are multiple types of sonnet. One of the most well-known forms is the Shakespearean sonnet, which is divided into three quatrains (4-line stanzas) and one couplet (2-line stanza).

Almost every professional poet has tried a sonnet at some point, from classical poets such as William Shakespeare , John Milton , and John Donne , as well as contemporary poets such as Kim Addonizio , R.S. Gwynn , and Cathy Park Hong .

Sonnets are great for practicing more advanced poetry. Their form forces you to think about rhyme and meter.

Sonnet 116 by William Shakespeare

Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove. O no, it is an ever fixed mark That looks on tempests and is never shaken; It is the star to every wand’ring barque, Whose worth’s unknown although his height be taken. Love’s not time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle’s compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved.

The villanelle is a 19-line poem with two lines that recur over and over throughout the poem.

The word “villanelle” comes from the Italian villanella , meaning rustic song or dance, because the two lines that are repeated resemble the chorus of a folk song. Using this form helps you to think about the sound and musicality of your writing.

Mad Girl’s Love Song by Sylvia Plath

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead; I lift my lids and all is born again. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

The stars go waltzing out in blue and red, And arbitrary blackness gallops in: I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed And sung me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell’s fires fade: Exit seraphim and Satan’s men: I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you’d return the way you said, But I grow old and I forget your name. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead; At least when spring comes they roar back again. I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead. (I think I made you up inside my head.)

Try a Poetic Form: Exercise

Pick your favorite poetic form (sonnet, limerick, haiku, or villanelle) and try writing a poem in that structure.

Remember that you don’t have to follow all the rules—pick the ones that spark your imagination, and ignore the ones that don’t.

These are our five favorite tips to get started writing poems. Feel free to try each of them, or to mix and match them to create something entirely new.

Have you tried any of these poetry methods before? Which ones are your favorites? Let us know in the comments.

Take your writing to the next level:

20 Editing Tips from Professional Writers

Whether you are writing a novel, essay, article, or email, good writing is an essential part of communicating your ideas., this guide contains the 20 most important writing tips and techniques from a wide range of professional writers..

Write like a bestselling author

Love writing? ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of your stories.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Poetry Writing

Tips for improving your poetry writing skills.

The section “Poetry Writing Skills” in our guide provides tips and techniques for improving your poetry writing skills. It covers a variety of ways to improve your poetry writing including:

Reading widely: Reading poetry written by other poets can help to expose you to different styles, forms, and techniques, and can inspire you to develop your own unique voice and style.

Experimenting with different forms and structures: Poets can try their hand at different forms of poetry, such as sonnets, haikus, and free verse, and explore different structures and techniques to find the one that works best for them.

Using descriptive language and imagery: Using descriptive language and imagery can help to bring your poetry to life and create a more vivid and engaging experience for your readers.

Paying attention to rhythm and sound: Paying attention to the rhythm and sound of your poetry can help to create a more musical and engaging experience for your readers.

Revising and editing your work: Revising and editing your work can help to improve its structure, imagery, and overall impact on readers.

Overall, the section “Poetry Writing Skills” provides tips and techniques for poets to improve their poetry writing skills. It covers the different ways to improve their skills by reading widely, experimenting with different forms, using descriptive language and imagery, paying attention to rhythm and sound, and revising and editing their work. It is designed to help poets to become more confident and proficient in their writing and to develop their own unique voice and style.

Ideas For Poems: Finding Inspiration

Our section on “Ideas for Poems” is designed to help poets find inspiration for their work and develop their own unique voice and style. It covers different ways to get inspired, from observing the world around to exploring different themes, structures, and techniques. It provides prompts, ideas and tips to help poets to generate new and exciting ideas for their poems.

Why Write Poetry?

Fostering a deeper appreciation for literature and the written word.

Encouraging critical thinking and reflection.

Enhancing creativity and imagination.

Improving language skills and vocabulary.

Poetry writing can be a highly beneficial and rewarding activity for many people. It is a powerful way to express emotions, thoughts, and ideas, and can help to improve writing skills, creativity, and self-expression. Some of the key benefits of poetry writing include:

Emotional catharsis: Poetry allows individuals to explore their emotions and feelings in a safe and creative way, helping to release pent-up emotions and reduce stress and anxiety.

Improved writing skills: Poetry often requires a high level of focus on language, structure, and imagery, which can help to improve writing skills, vocabulary, grammar and learning poetic elements.

Increased creativity: Poetry provides a unique form of creative expression, where individuals can experiment with different styles, forms, and techniques, and push their own creative boundaries.

Self-expression: Poetry can be a powerful tool for self-expression, allowing individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences, and to communicate them to others.

Empathy and understanding: Poetry can be a powerful way to connect with others, by providing a window into the emotions and experiences of others.

Self-discovery: Writing poetry can help people to better understand themselves, their emotions and experiences, and can help them to uncover new insights and perspectives.

Overall, poetry writing can be a valuable and fulfilling activity that can help to improve emotional well-being, writing skills, and creativity, while also providing a powerful means of self-expression and connection with others.

Poetry Writing Exercises & Prompts

Our guide to “Poetry Writing Exercises & Writing Prompts” provides a variety of exercises and prompts to help poets generate new creative writing ideas and improve their poetry writing skills. It covers different exercises such as free-writing, theme-based, form-based, imagery-based and rhythm-based, to help poets to find new inspiration, explore different emotions and perspectives, experiment with different forms and structures, and to create more vivid and engaging poetry.

An Overview of Our Guide to Poetry Writing

Our guide to poetry writing is divided into three main sub-topics to help aspiring poets develop their skills and find inspiration for their work. There are other options to help with writing poems such as literary devices. While they are useful, we have many other choices available also.

Poetry Writing Skills: This section of the guide covers the basic skills needed to write poetry in a poetic form, including understanding poetic forms and devices, learning to use imagery and metaphor effectively, and developing a strong sense of voice and style. It also covers tips for editing and revising poems, as well as advice for getting published.

Ideas for Poems: This section of the guide provides inspiration and prompts for generating ideas for poems, including tips for observing and writing about the world around you, using personal experiences and emotions as inspiration, and exploring different themes and subjects. Additionally, it covers how to use real-life experiences to inspire poetry, encouraging readers to draw on their own emotions and observations to create powerful and relatable work.

Poetry Writing Exercises and Prompts: This section of the guide includes a variety of exercises and writing prompts to help poets practice their craft and develop their skills, such as writing in different forms, experimenting with different structures and techniques, and using specific words, phrases, or images as inspiration. The prompts will help to push the poets creative boundaries and to explore new ways of writing different kinds of poetry such as free verse poetry. The guide covers the various forms of poetry, from traditional sonnets to modern free verse, and provides examples and exercises to help poets experiment with different forms and find the one that suits them best.

Overall, our guide to the poetry writing process is designed to help poets of all levels improve their skills, find inspiration, and develop their own unique voice and style. It includes a section on how to get published, providing advice on how to submit poetry to literary journals and magazines, as well as tips for building a strong online presence and networking with other poets. Additionally, it covers how to write poetry that is accessible to the readers and how to make it relatable, with practical advice on how to convey complex ideas and emotions in a clear and concise way.

Our guide to writing poems in an excitingly wonderful way mixes well with Grammarly’s post about How to Write a Poem . It is a great guide if you’re ready to begin your own poem writing adventure. We have explored with concrete words and brought to the surface great ideas for anyone to get started writing epic poetry.

Remember to use figurative language, a rhyme scheme and some helpful ideas to get your creative juices flowing! Great poetry always begins with an idea.

- Privacy Policy

How to Write a Poem: In 7 Practical Steps with Examples

Learn how to write a poem through seven easy to follow steps that will guide you through writing completed poem. Ignite a passion for poetry!

This article is a practical guide for writing a poem, and the purpose is to help you write a poem! By completing the seven steps below, you will create the first draft of a simple poem. You can go on to refine your poetry in any way you like. The important thing is that you’ve got a poem under your belt.

At the bottom of the post, I’ll provide more resources on writing poetry. I encourage you to explore different forms and structures and continue writing poetry on your own. Hopefully, writing a poem will spark, in you, a passion for creative writing and language.

Let’s get started with writing a poem in seven simple steps:

- Brainstorm & Free-write

- Develop a theme

- Create an extended metaphor

- Add figurative language

- Plan your structure

- Write your first draft

- Read, re-read & edit

Now we’ll go into each step in-depth. And, if your feeling up to it, you can plan and write your poem as we go.

Step 1: Brainstorm and Free-write

Find what you want to write about

Before you begin writing, you need to choose a subject to write about. For our purposes, you’ll want to select a specific topic. Later, you’ll be drawing a comparison between this subject and something else.

When choosing a subject, you’ll want to write about something you feel passionately about. Your topic can be something you love, like a person, place, or thing. A subject can also be something you struggle with . Don’t get bogged down by all the options; pick something. Poets have written about topics like:

And of course… cats

Once you have your subject in mind, you’re going to begin freewriting about that subject. Let’s say you picked your pet iguana as your subject. Get out a sheet of paper or open a word processor. Start writing everything that comes to mind about that subject. You could write about your iguana’s name, the color of their skin, the texture of their scales, how they make you feel, a metaphor that comes to mind. Nothing is off-limits.

Write anything that comes to mind about your subject. Keep writing until you’ve entirely exhausted everything you have to say about the subject. Or, set a timer for several minutes and write until it goes off. Don’t worry about things like spelling, grammar, form, or structure. For now, you want to get all your thoughts down on paper.

ACTION STEPS:

- Grab a scratch paper, or open a word processor

- Pick a subject- something you’re passionate about

- Write everything that comes to mind about your topic without editing or structuring your writing

- Make sure this free-writing is uninterrupted

- Optional- set a timer and write continuously for 5 or 10 minutes about your subject

Step 2: Develop a Theme

What lesson do you want to teach?

Poetry often has a theme or a message the poet would like to convey to the reader. Developing a theme will give your writing purpose and focus your effort. Look back at your freewriting and see if a theme, or lesson, has developed naturally, one that you can refine.

Maybe, in writing about your iguana, you noticed that you talked about your love for animals and the need to preserve the environment. Or, perhaps you talk about how to care for a reptile pet. Your theme does not need to be groundbreaking. A theme only needs to be a message that you would like to convey.

Now, what is your theme? Finish the following statement:

The lesson I want to teach my readers about (your subject) is ______

Ex. I want to teach my readers that spring days are lovely and best enjoyed with loving companions or family.

- Read over the product of your free-writing exercise.

- Brainstorm a lesson you would like to teach readers about your subject.

- Decide on one thing that is essential for your reader to know about your topic.

- Finish the sentence stem above.

Step 3: Create an (extended) Metaphor

Compare your subject to another, unlike thing.

To write this poem, you will compare your subject to something it, seemingly, has nothing in common with. When you directly compare two, unlike things, you’re using a form of figurative language called a metaphor. But, we’re going to take this metaphor and extend it over one or two stanzas- Stanzas are like paragraphs, a block of text in a poem- Doing this will create an extended metaphor.

Using a metaphor will reinforce your theme by making your poem memorable for your reader. Keep that in mind when you’re choosing the thing you’d like to compare your subject to. Suppose your topic is pet iguanas, and your theme is that they make fantastic pets. In that case, you’ll want to compare iguanas to something positive. Maybe you compare them to sunshine or a calm lake. This metaphor does the work or conveying your poem’s central message.

- Identify something that is, seemingly, unlike your subject that you’ll use to compare.

- On a piece of paper, make two lists or a Venn diagram.

- Write down all the ways that you’re subject and the thing you’ll compare it to are alike.

- Also, write down all the ways they are unalike.

- Try and make both lists as comprehensive as possible.

Step 4: Add more Figurative Language

Make your writing sound poetic.

Figurative language is a blanket term that describes several techniques used to impart meaning through words. Figurative language is usually colorful and evocative. We’ve talked about one form of figurative language already- metaphor and extended metaphor. But, here are a few others you can choose from.

This list is, by no means, a comprehensive one. There are many other forms of figurative language for you to research. I’ll link a resource at the bottom of this page.

Five types of figurative language:

- Ex. Frank was as giddy as a schoolgirl to find a twenty-dollar bill in his pocket.

- Frank’s car engine whined with exhaustion as he drove up the hill.

- Frank was so hungry he could eat an entire horse.

- Nearing the age of eighty-five, Frank felt as old as Methuselah.

- Frank fretted as he frantically searched his forlorn apartment for a missing Ficus tree.

There are many other types of figurative language, but those are a few common ones. Pick two of the five I’ve listed to include in your poem. Use more if you like, but you only need two for your current poem.

- Choose two of the types of figurative language listed above

- Brainstorm ways they can fit into a poem

- Create example sentences for the two forms of figurative language you chose

Step 5: Plan your Structure

How do you want your poem to sound and look?

If you want to start quickly, then you can choose to write a free-verse poem. Free verse poems are poems that have no rhyme scheme, meter, or structure. In a free verse poem, you’re free to write unrestricted. If you’d like to explore free verse poetry, you can read my article on how to write a prose poem, which is a type of free verse poem.

Read more about prose poetry here.

However, some people enjoy the support of structure and rules. So, let’s talk about a few of the tools you can use to add a form to your poem.

Tools to create poetic structure:

Rhyme Scheme – rhyme scheme refers to the pattern of rhymes used in a poem. The sound at the end of each line determines the rhyme scheme. Writers label words with letters to signify rhyming terms, and this is how rhyme schemes are defined.

If you had a four-line poem that followed an ABAB scheme, then lines 1 and 3 would rhyme, and lines 2 and 4 would rhyme. Here’s an example of an ABAB rhyme scheme from an excerpt of Robert Frost’s poem, Neither Out Far Nor In Deep:

‘The people along the sand (A)

All turn and look one way. (B)

They turn their back on the land. (A)

They look at the sea all day. (B)

Check out the Rhyme Zone.com if you need help coming up with a rhyme!

Read more about the ins and outs of rhyme scheme here.

Meter – a little more advanced than rhyme scheme, meter deals with a poem’s rhythm expressed through stressed and unstressed syllables. Meter can get pretty complicated ,

Check out this article if you’d like to learn more about it.

Stanza – a stanza is a group of lines placed together as a single unit in a poem. A stanza is to a poem what a paragraph is to prose writing. Stanzas don’t have to be the same number of lines throughout a poem, either. They can vary as paragraphs do.

Line Breaks – these are the breaks between stanzas in a poem. They help to create rhythm and set stanzas apart from one another.

- Decide if you want to write a structured poem or use free verse

- Brainstorm rhyming words that could fit into a simple scheme

- Plan out your stanzas and line breaks (small stanzas help emphasize important lines in your poem)

Step 6: Write Your Poem

Combine your figurative language, extended metaphor, and structure.

Poetry is always unique to the writer. And, when it comes to poetry, the “rules” are flexible. In 1965 a young poet named Aram Saroyan wrote a poem called lighght. It goes like this-

That’s it. Saroyan was paid $750 for his poem. You may or may not believe that’s poetry, but a lot of people accept it as just that. My point is, write the poem that comes to you. I won’t give you a strict set of guidelines to follow when creating your poetry. But, here are a few things to consider that might help guide you:

- Compare your subject to something else by creating an extended metaphor

- Try to relate a theme or a simple lesson for your reader

- Use at least two of the figurative language techniques from above

- Create a meter or rhyme scheme (if you’re up to it)

- Write at least two stanzas and use a line break

Still, need some help? Here are two well-known poems that are classic examples of an extended metaphor. Read over them, determine what two, unlike things, are being compared, and for what purpose? What theme is the poet trying to convey? What techniques can you steal? (it’s the sincerest form of flattery)

“Hope” is a thing with feathers by Emily Dickenson.

“The Rose that Grew From Concrete” by Tupac Shakur.

- Write the first draft of your poem.

- Don’t stress. Just get the poem on paper.

Step 7: Read, Re-read, Edit

Read your poem, and edit for clarity and focus .

When you’re finished, read over your poem. Do this out loud to get a feel for the poem’s rhythm. Have a friend or peer read your poem, edit for grammar and spelling. You can also stretch grammar rules, but do it with a purpose.

You can also ask your editor what they think the theme is to determine if you’ve communicated it well enough.

Now you can rewrite your poem. And, remember, all writing is rewriting. This editing process will longer than it did to write your first draft.

- Re-read your poem out loud.

- Find a trusted friend to read over your poem.

- Be open to critique, new ideas, and unique perspectives.

- Edit for mistakes or style.

Use this image on your blog, Google classroom, or Canvas page by right-clicking for the embed code. Look for this </> symbol to embed the image on your page.

Continued reading on Poetry

A Poetry Handbook

“With passion, wit, and good common sense, the celebrated poet Mary Oliver tells of the basic ways a poem is built—meter and rhyme, form and diction, sound and sense. She talks of iambs and trochees, couplets and sonnets, and how and why this should matter to anyone writing or reading poetry.”

Masterclass.com- Poetry 101: What is Meter?

Poetry Foundation- You Call That Poetry?!

This post contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links

Published by John

View all posts by John

6 comments on “How to Write a Poem: In 7 Practical Steps with Examples”

- Pingback: Haiku Format: How to write a haiku in three steps - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: How to Write a List Poem: A Step by Step Guide - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: How to Write an Acrostic Poem: Tips & Examples - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: List of 10+ how to write a good poem

No problem!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Copy and paste this code to display the image on your site

Discover more from The Art of Narrative

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Jerz's Literacy Weblog (est. 1999)

Poetry writing tips: 10 helpful hacks for how to write a poem.

Jerz > Writing > General Creative Writing Tips [ Poetry | Fiction ]

If you are writing a poem because you want to capture a feeling that you experienced , then you don’t need these tips. Just write whatever feels right. Only you experienced the feeling that you want to express, so only you will know whether your poem succeeds.

If, however, your goal is to communicate with a reader — drawing on the established conventions of a literary genre (conventions that will be familiar to the experienced reader) to generate an emotional response in your reader — then simply writing what feels right to you won’t be enough. (See also “ Poetry is for the Ear ” and “ When Backwards Newbie Poets Write .”)

These tips will help you make an important transition:

- away from writing poetry to celebrate, commemorate, or capture your own feelings (in which case you, the poet, are the center of the poem’s universe)

- towards writing poetry in order to generate feelings in your reader (in which case the poem exists entirely to serve the reader).

- Avoid Clichés

- Avoid Sentimentality

- Use Metaphor and Simile

- Use Concrete Words Instead of Abstract Words

- Communicate Theme

- Subvert the Ordinary

- Rhyme with Extreme Caution

- Revise, Revise, Revise

Tip #1 Know Your Goal.

If you don’t know where you’re going, how can you get there?

You need to know what you are trying to accomplish before you begin any project. Writing a poem is no exception.

Before you begin, ask yourself what you want your poem to “do.” Do you want your poem to explore a personal experience, protest a social injustice, describe the beauty of nature, or play with language in a certain way? Once your know the goal of your poem, you can conform your writing to that goal. Take each main element in your poem and make it serve the main purpose of the poem.

Tip #2 Avoid Clichés

Stephen Minot defines a cliché as: “A metaphor or simile that has become so familiar from overuse that the vehicle … no longer contributes any meaning whatever to the tenor. It provides neither the vividness of a fresh metaphor nor the strength of a single unmodified word….The word is also used to describe overused but nonmetaphorical expressions such as ‘tried and true’ and ‘each and every'” ( Three Genres: The Writing of Poetry, Fiction and Drama , 405).

Cliché also describes other overused literary elements. “Familiar plot patterns and stock characters are clichés on a big scale” (Minot 148). Clichés can be overused themes, character types, or plots. For example, the “Lone Ranger” cowboy is a cliché because it has been used so many times that people no longer find it original.

A work full of clichés is like a plate of old food: unappetizing.

More creative writing tips.

Clichés work against original communication. People value creative talent. They want to see work that rises above the norm. When they see a work without clichés, they know the writer has worked his or her tail off, doing whatever it takes to be original. When they see a work full to the brim with clichés, they feel that the writer is not showing them anything above the ordinary. (In case you hadn’t noticed, this paragraph is chock full of clichés… I’ll bet you were bored to tears.)

Clichés dull meaning. Because clichéd writing sounds so familiar, people can finish whole lines without even reading them. If they don’t bother to read your poem, they certainly won’t stop to think about it. If they do not stop to think about your poem, they will never encounter the deeper meanings that mark the work of an accomplished poet.

Examples of Clichés:

How to improve a cliché.

I will take the cliché “as busy as a bee” and show how you can express the same idea without cliché.

- Determine what the clichéd phrase is trying to say. In this case, I can see that “busy as a bee” is a way to describe the state of being busy.

- Think of an original way to describe what the cliché is trying to describe. For this cliché, I started by thinking about busyness. I asked myself the question, “What things are associated with being busy?” I came up with: college, my friend Jessica, corporation bosses, old ladies making quilts and canning goods, and a computer, fiddlers fiddling. From this list, I selected a thing that is not as often used in association with busyness: violins.

- Create a phrase using the non-clichéd way of description. I took my object associated with busyness and turned it into a phrase: “I feel like a bow fiddling an Irish reel.” This phrase communicates the idea of “busyness” much better than the worn-out, familiar cliché. The reader’s mind can picture the insane fury of the bow on the violin, and know that the poet is talking about a very frenzied sort of busyness. In fact, those readers who know what an Irish reel sounds like may even get a laugh out of this fresh way to describe “busyness.”

Try it! Take a cliché and use these steps to improve it. You may even end up with a line you feel is good enough to put in a poem!

Tip #3 Avoid Sentimentality.

Sentimentality is “dominated by a blunt appeal to the emotions of pity and love …. Popular subjects are puppies, grandparents, and young lovers” (Minot 416). “When readers have the feeling that emotions like rage or indignation have been pushed artificially for their own sake, they will not take the poem seriously” (132).

Minot says that the problem with sentimentality is that it detracts from the literary quality of your work (416). If your poetry is mushy or teary-eyed, your readers may openly rebel against your effort to invoke emotional response in them. If that happens, they will stop thinking about the issues you want to raise, and will instead spend their energy trying to control their own gag reflex.

Tip #4 Use Images.

“BE A PAINTER IN WORDS,” says UWEC English professor emerita, poet, and songwriter Peg Lauber. She says poetry should stimulate six senses:

- kinesiology (motion)

- “Sunlight varnishes magnolia branches crimson” (sight)

- “Vacuum cleaner’s whir and hum startles my ferret” (hearing)

- “Penguins lumber to their nests” (kinesiology)

Lauber advises her students to produce fresh, striking images (“imaginative”). Be a camera. Make the reader be there with the poet/speaker/narrator. (See also: “ Show, Don’t (Just) Tell “)

Tip #5 Use Metaphor and Simile.

Use metaphor and simile to bring imagery and concrete words into your writing.

A metaphor is a statement that pretends one thing is really something else: Example: “The lead singer is an elusive salamander.” This phrase does not mean that the lead singer is literally a salamander. Rather, it takes an abstract characteristic of a salamander (elusiveness) and projects it onto the person. By using metaphor to describe the lead singer, the poet creates a much more vivid picture of him/her than if the poet had simply said “The lead singer’s voice is hard to pick out.”