How to Annotate Texts

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Annotation Fundamentals

How to start annotating , how to annotate digital texts, how to annotate a textbook, how to annotate a scholarly article or book, how to annotate literature, how to annotate images, videos, and performances, additional resources for teachers.

Writing in your books can make you smarter. Or, at least (according to education experts), annotation–an umbrella term for underlining, highlighting, circling, and, most importantly, leaving comments in the margins–helps students to remember and comprehend what they read. Annotation is like a conversation between reader and text. Proper annotation allows students to record their own opinions and reactions, which can serve as the inspiration for research questions and theses. So, whether you're reading a novel, poem, news article, or science textbook, taking notes along the way can give you an advantage in preparing for tests or writing essays. This guide contains resources that explain the benefits of annotating texts, provide annotation tools, and suggest approaches for diverse kinds of texts; the last section includes lesson plans and exercises for teachers.

Why annotate? As the resources below explain, annotation allows students to emphasize connections to material covered elsewhere in the text (or in other texts), material covered previously in the course, or material covered in lectures and discussion. In other words, proper annotation is an organizing tool and a time saver. The links in this section will introduce you to the theory, practice, and purpose of annotation.

How to Mark a Book, by Mortimer Adler

This famous, charming essay lays out the case for marking up books, and provides practical suggestions at the end including underlining, highlighting, circling key words, using vertical lines to mark shifts in tone/subject, numbering points in an argument, and keeping track of questions that occur to you as you read.

How Annotation Reshapes Student Thinking (TeacherHUB)

In this article, a high school teacher discusses the importance of annotation and how annotation encourages more effective critical thinking.

The Future of Annotation (Journal of Business and Technical Communication)

This scholarly article summarizes research on the benefits of annotation in the classroom and in business. It also discusses how technology and digital texts might affect the future of annotation.

Annotating to Deepen Understanding (Texas Education Agency)

This website provides another introduction to annotation (designed for 11th graders). It includes a helpful section that teaches students how to annotate reading comprehension passages on tests.

Once you understand what annotation is, you're ready to begin. But what tools do you need? How do you prepare? The resources linked in this section list strategies and techniques you can use to start annotating.

What is Annotating? (Charleston County School District)

This resource gives an overview of annotation styles, including useful shorthands and symbols. This is a good place for a student who has never annotated before to begin.

How to Annotate Text While Reading (YouTube)

This video tutorial (appropriate for grades 6–10) explains the basic ins and outs of annotation and gives examples of the type of information students should be looking for.

Annotation Practices: Reading a Play-text vs. Watching Film (U Calgary)

This blog post, written by a student, talks about how the goals and approaches of annotation might change depending on the type of text or performance being observed.

Annotating Texts with Sticky Notes (Lyndhurst Schools)

Sometimes students are asked to annotate books they don't own or can't write in for other reasons. This resource provides some strategies for using sticky notes instead.

Teaching Students to Close Read...When You Can't Mark the Text (Performing in Education)

Here, a sixth grade teacher demonstrates the strategies she uses for getting her students to annotate with sticky notes. This resource includes a link to the teacher's free Annotation Bookmark (via Teachers Pay Teachers).

Digital texts can present a special challenge when it comes to annotation; emerging research suggests that many students struggle to critically read and retain information from digital texts. However, proper annotation can solve the problem. This section contains links to the most highly-utilized platforms for electronic annotation.

Evernote is one of the two big players in the "digital annotation apps" game. In addition to allowing users to annotate digital documents, the service (for a fee) allows users to group multiple formats (PDF, webpages, scanned hand-written notes) into separate notebooks, create voice recordings, and sync across all sorts of devices.

OneNote is Evernote's main competitor. Reviews suggest that OneNote allows for more freedom for digital note-taking than Evernote, but that it is slightly more awkward to import and annotate a PDF, especially on certain platforms. However, OneNote's free version is slightly more feature-filled, and OneNote allows you to link your notes to time stamps on an audio recording.

Diigo is a basic browser extension that allows a user to annotate webpages. Diigo also offers a Screenshot app that allows for direct saving to Google Drive.

While the creators of Hypothesis like to focus on their app's social dimension, students are more likely to be interested in the private highlighting and annotating functions of this program.

Foxit PDF Reader

Foxit is one of the leading PDF readers. Though the full suite must be purchased, Foxit offers a number of annotation and highlighting tools for free.

Nitro PDF Reader

This is another well-reviewed, free PDF reader that includes annotation and highlighting. Annotation, text editing, and other tools are included in the free version.

Goodreader is a very popular Mac-only app that includes annotation and editing tools for PDFs, Word documents, Powerpoint, and other formats.

Although textbooks have vocabulary lists, summaries, and other features to emphasize important material, annotation can allow students to process information and discover their own connections. This section links to guides and video tutorials that introduce you to textbook annotation.

Annotating Textbooks (Niagara University)

This PDF provides a basic introduction as well as strategies including focusing on main ideas, working by section or chapter, annotating in your own words, and turning section headings into questions.

A Simple Guide to Text Annotation (Catawba College)

The simple, practical strategies laid out in this step-by-step guide will help students learn how to break down chapters in their textbooks using main ideas, definitions, lists, summaries, and potential test questions.

Annotating (Mercer Community College)

This packet, an excerpt from a literature textbook, provides a short exercise and some examples of how to do textbook annotation, including using shorthand and symbols.

Reading Your Healthcare Textbook: Annotation (Saddleback College)

This powerpoint contains a number of helpful suggestions, especially for students who are new to annotation. It emphasizes limited highlighting, lots of student writing, and using key words to find the most important information in a textbook. Despite the title, it is useful to a student in any discipline.

Annotating a Textbook (Excelsior College OWL)

This video (with included transcript) discusses how to use textbook features like boxes and sidebars to help guide annotation. It's an extremely helpful, detailed discussion of how textbooks are organized.

Because scholarly articles and books have complex arguments and often depend on technical vocabulary, they present particular challenges for an annotating student. The resources in this section help students get to the heart of scholarly texts in order to annotate and, by extension, understand the reading.

Annotating a Text (Hunter College)

This resource is designed for college students and shows how to annotate a scholarly article using highlighting, paraphrase, a descriptive outline, and a two-margin approach. It ends with a sample passage marked up using the strategies provided.

Guide to Annotating the Scholarly Article (ReadWriteThink.org)

This is an effective introduction to annotating scholarly articles across all disciplines. This resource encourages students to break down how the article uses primary and secondary sources and to annotate the types of arguments and persuasive strategies (synthesis, analysis, compare/contrast).

How to Highlight and Annotate Your Research Articles (CHHS Media Center)

This video, developed by a high school media specialist, provides an effective beginner-level introduction to annotating research articles.

How to Read a Scholarly Book (AndrewJacobs.org)

In this essay, a college professor lets readers in on the secrets of scholarly monographs. Though he does not discuss annotation, he explains how to find a scholarly book's thesis, methodology, and often even a brief literature review in the introduction. This is a key place for students to focus when creating annotations.

A 5-step Approach to Reading Scholarly Literature and Taking Notes (Heather Young Leslie)

This resource, written by a professor of anthropology, is an even more comprehensive and detailed guide to reading scholarly literature. Combining the annotation techniques above with the reading strategy here allows students to process scholarly book efficiently.

Annotation is also an important part of close reading works of literature. Annotating helps students recognize symbolism, double meanings, and other literary devices. These resources provide additional guidelines on annotating literature.

AP English Language Annotation Guide (YouTube)

In this ~10 minute video, an AP Language teacher provides tips and suggestions for using annotations to point out rhetorical strategies and other important information.

Annotating Text Lesson (YouTube)

In this video tutorial, an English teacher shows how she uses the white board to guide students through annotation and close reading. This resource uses an in-depth example to model annotation step-by-step.

Close Reading a Text and Avoiding Pitfalls (Purdue OWL)

This resources demonstrates how annotation is a central part of a solid close reading strategy; it also lists common mistakes to avoid in the annotation process.

AP Literature Assignment: Annotating Literature (Mount Notre Dame H.S.)

This brief assignment sheet contains suggestions for what to annotate in a novel, including building connections between parts of the book, among multiple books you are reading/have read, and between the book and your own experience. It also includes samples of quality annotations.

AP Handout: Annotation Guide (Covington Catholic H.S.)

This annotation guide shows how to keep track of symbolism, figurative language, and other devices in a novel using a highlighter, a pencil, and every part of a book (including the front and back covers).

In addition to written resources, it's possible to annotate visual "texts" like theatrical performances, movies, sculptures, and paintings. Taking notes on visual texts allows students to recall details after viewing a resource which, unlike a book, can't be re-read or re-visited ( for example, a play that has finished its run, or an art exhibition that is far away). These resources draw attention to the special questions and techniques that students should use when dealing with visual texts.

How to Take Notes on Videos (U of Southern California)

This resource is a good place to start for a student who has never had to take notes on film before. It briefly outlines three general approaches to note-taking on a film.

How to Analyze a Movie, Step-by-Step (San Diego Film Festival)

This detailed guide provides lots of tips for film criticism and analysis. It contains a list of specific questions to ask with respect to plot, character development, direction, musical score, cinematography, special effects, and more.

How to "Read" a Film (UPenn)

This resource provides an academic perspective on the art of annotating and analyzing a film. Like other resources, it provides students a checklist of things to watch out for as they watch the film.

Art Annotation Guide (Gosford Hill School)

This resource focuses on how to annotate a piece of art with respect to its formal elements like line, tone, mood, and composition. It contains a number of helpful questions and relevant examples.

Photography Annotation (Arts at Trinity)

This resource is designed specifically for photography students. Like some of the other resources on this list, it primarily focuses on formal elements, but also shows students how to integrate the specific technical vocabulary of modern photography. This resource also contains a number of helpful sample annotations.

How to Review a Play (U of Wisconsin)

This resource from the University of Wisconsin Writing Center is designed to help students write a review of a play. It contains suggested questions for students to keep in mind as they watch a given production. This resource helps students think about staging, props, script alterations, and many other key elements of a performance.

This section contains links to lessons plans and exercises suitable for high school and college instructors.

Beyond the Yellow Highlighter: Teaching Annotation Skills to Improve Reading Comprehension (English Journal)

In this journal article, a high school teacher talks about her approach to teaching annotation. This article makes a clear distinction between annotation and mere highlighting.

Lesson Plan for Teaching Annotation, Grades 9–12 (readwritethink.org)

This lesson plan, published by the National Council of Teachers of English, contains four complete lessons that help introduce high school students to annotation.

Teaching Theme Using Close Reading (Performing in Education)

This lesson plan was developed by a middle school teacher, and is aligned to Common Core. The teacher presents her strategies and resources in comprehensive fashion.

Analyzing a Speech Using Annotation (UNC-TV/PBS Learning Media)

This complete lesson plan, which includes a guide for the teacher and relevant handouts for students, will prepare students to analyze both the written and presentation components of a speech. This lesson plan is best for students in 6th–10th grade.

Writing to Learn History: Annotation and Mini-Writes (teachinghistory.org)

This teaching guide, developed for high school History classes, provides handouts and suggested exercises that can help students become more comfortable with annotating historical sources.

Writing About Art (The College Board)

This Prezi presentation is useful to any teacher introducing students to the basics of annotating art. The presentation covers annotating for both formal elements and historical/cultural significance.

Film Study Worksheets (TeachWithMovies.org)

This resource contains links to a general film study worksheet, as well as specific worksheets for novel adaptations, historical films, documentaries, and more. These resources are appropriate for advanced middle school students and some high school students.

Annotation Practice Worksheet (La Guardia Community College)

This worksheet has a sample text and instructions for students to annotate it. It is a useful resource for teachers who want to give their students a chance to practice, but don't have the time to select an appropriate piece of text.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1924 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,556 quotes across 1924 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ an- uh - tey -sh uh n ]

- a critical or explanatory note or body of notes added to a text.

- the act of annotating .

- note ( def 1 ) . : annot.

/ ˌænə-; ˌænəʊˈteɪʃən /

- the act of annotating

- a note added in explanation, etc, esp of some literary work

Discover More

Other words from.

- rean·no·tation noun

Word History and Origins

Origin of annotation 1

Example Sentences

Announced in July, along with new Smart Shopping display ad formats and shipping annotations, the new customer acquisition goal allows marketers to set a separate conversion value on new customers to inform Google’s automated bidding.

They can now go from the simplified viewing and remote collaboration to this bigger file sharing and increased preview mode and annotations.

Ordinary website users do this annotation too, when they complete a reCAPTCHA.

A few early versions of what became the final design, with placeholder data and annotations.

Make an annotation in your analytics noting that organic search reporting should be ignored for that whole time period.

The term Abernaquis, is also a French mode of annotation for the same word, but is rather applied at this time to a specific band.

Modern editors of what they call the "Roman Elegies" bring abundant annotation, and often detail Goethe's own emendations.

Footnote tags that were missing in the original are underlined without further annotation.

In olden times the place was unknown, but can be doubtfully identified with A-nok-ta-shan in the annotation of Shui-ching.

Sippi, agreeably to the early French annotation of the word, signifies a river.

Related Words

More about annotation, what does annotation mean.

An annotation is a note or comment added to a text to provide explanation or criticism about a particular part of it.

Annotation can also refer to the act of annotating —adding annotations.

Annotations are often added to scholarly articles or to literary works that are being analyzed. But the term can be used in a more general way to refer to a note added to any text. For example, a note that you scribble in the margin of your textbook is an annotation , as is an explanatory comment that you add to a list of tasks at work.

Something that has had such notes added to it can be described as annotated .

The word annotation is sometimes abbreviated as annot . (which can also mean annotated or annotator ).

Example: The annotations in this edition of the book really helped me to understand the historical context and the meanings of some obscure words.

Where does annotation come from?

The first records of the word annotation come from the 1400s. It derives from the Latin annotātus, meaning “noted down,” from the Latin nota , which means “mark” and is also the basis of the English word note.

Typically, annotations are used to comment on a text, such as by adding an explanation, criticism, analysis, or historical perspective. The word can be used in more specific ways in different contexts. In an annotated bibliography , an annotation is added to each citation. In computer programming, annotations are explanatory notes added to strings of code. In genomics , annotations involve interpretations of genes and their possible functions. In all cases, the word refers to some kind of extra information added to an existing thing.

Did you know ... ?

What are some other forms related to annotation ?

- reannotation (noun)

- annotate (verb)

What are some synonyms for annotation ?

What are some words that share a root or word element with annotation ?

What are some words that often get used in discussing annotation ?

- explanation

How is annotation used in real life?

Annotation is most commonly used in the context of academic and literary works.

Just a pet peeve. In particular Ulysses fans who are like “I can’t even begin to understand this genius text”. I’m like… well, have you tried getting an edition with annotations? The Jeri Johnson one is great. You could also re-read the Odyssey and Hamlet. Or keep a journal. — Ms. Lola, Moon Girl 🌙✨ (@mslola1904) July 27, 2020

This 1935 edition of Richard III features copious annotations by actor Sir Laurence Olivier. Olivier was born #otd … https://t.co/7kBroX7bDM pic.twitter.com/zX5s3XAODz — Folger Shakespeare Library (@FolgerLibrary) May 22, 2017

Most common & least helpful annotation I make in books: “interesting!” In the words of me, tell me more. — Dahlia Seroussi (@DahliaSeroussi) July 13, 2020

Try using annotation !

Which of the following words is NOT a synonym of annotation ?

A. comment B. title C. note D. notation

Annotating Texts

What is annotation.

Annotation can be:

- A systematic summary of the text that you create within the document

- A key tool for close reading that helps you uncover patterns, notice important words, and identify main points

- An active learning strategy that improves comprehension and retention of information

Why annotate?

- Isolate and organize important material

- Identify key concepts

- Monitor your learning as you read

- Make exam prep effective and streamlined

- Can be more efficient than creating a separate set of reading notes

How do you annotate?

Summarize key points in your own words .

- Use headers and words in bold to guide you

- Look for main ideas, arguments, and points of evidence

- Notice how the text organizes itself. Chronological order? Idea trees? Etc.

Circle key concepts and phrases

- What words would it be helpful to look-up at the end?

- What terms show up in lecture? When are different words used for similar concepts? Why?

Write brief comments and questions in the margins

- Be as specific or broad as you would like—use these questions to activate your thinking about the content

- See our handout on reading comprehension tips for some examples

Use abbreviations and symbols

- Try ? when you have a question or something you need to explore further

- Try ! When something is interesting, a connection, or otherwise worthy of note

- Try * For anything that you might use as an example or evidence when you use this information.

- Ask yourself what other system of symbols would make sense to you.

Highlight/underline

- Highlight or underline, but mindfully. Check out our resource on strategic highlighting for tips on when and how to highlight.

Use comment and highlight features built into pdfs, online/digital textbooks, or other apps and browser add-ons

- Are you using a pdf? Explore its highlight, edit, and comment functions to support your annotations

- Some browsers have add-ons or extensions that allow you to annotate web pages or web-based documents

- Does your digital or online textbook come with an annotation feature?

- Can your digital text be imported into a note-taking tool like OneNote, EverNote, or Google Keep? If so, you might be able to annotate texts in those apps

What are the most important takeaways?

- Annotation is about increasing your engagement with a text

- Increased engagement, where you think about and process the material then expand on your learning, is how you achieve mastery in a subject

- As you annotate a text, ask yourself: how would I explain this to a friend?

- Put things in your own words and draw connections to what you know and wonder

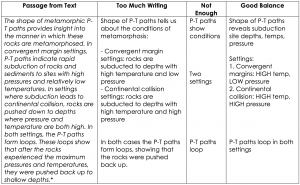

The table below demonstrates this process using a geography textbook excerpt (Press 2004):

A common concern about annotating texts: It takes time!

Yes, it can, but that time isn’t lost—it’s invested.

Spending the time to annotate on the front end does two important things:

- It saves you time later when you’re studying. Your annotated notes will help speed up exam prep, because you can review critical concepts quickly and efficiently.

- It increases the likelihood that you will retain the information after the course is completed. This is especially important when you are supplying the building blocks of your mind and future career.

One last tip: Try separating the reading and annotating processes! Quickly read through a section of the text first, then go back and annotate.

Works consulted:

Nist, S., & Holschuh, J. (2000). Active learning: strategies for college success. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. 202-218.

Simpson, M., & Nist, S. (1990). Textbook annotation: An effective and efficient study strategy for college students. Journal of Reading, 34: 122-129.

Press, F. (2004). Understanding earth (4th ed). New York: W.H. Freeman. 208-210.

Make a Gift

A Reader's Guide to Annotation

Marking and highlighting a text is like having a conversation with a book - it allows you to ask questions, comment on meaning, and mark events and passages you wanted to revisit. Annotating is a permanent record of your intellectual conversations with the text.

As you work with your text, think about all the ways that you can connect with what you are reading . What follows are some suggestions that will help with annotating.

- 1.1 Suggested methods for marking a text

Beginning to Annotate [ edit | edit source ]

- Use a pen, pencil, post-it notes, or a highlighter (use it sparingly)

- Summarize important ideas in your own words.

- Add examples from real life, other books, TV, movies, and so forth.

- Define words that are new to you

- Mark passages that you find confusing with question marks

- Write questions that you might have for later discussion in class.

- Comment on the actions or development of characters.

- Comment on things that intrigue, impress, surprise, disturb, etc.

- Note how the author uses language. A list of possible literary devices is attached.

- Feel free to draw picture when a visual connection is appropriate.

- Explain the historical context or traditions/social customs used in the passage.

- If possible, summarize paragraphs, especially those you do not understand.

Suggested methods for marking a text [ edit | edit source ]

- If you are a person who does not like to write in a book, you may want to invest in a supply of post it notes.

- If you feel really creative, or are just super organized, you can even color code your annotations by using different color post-its, highlighters, or pens

- Brackets: If several lines seem important, just draw a line down the margin and underline/highlight only the key phrases.

- Asterisks: Place and asterisk next to an important passage; use two if it is really important

- Marginal Notes: Use the space in the margins to make comments, define words, ask questions, etc.

- Underline/highlight; Caution! Do not underline or highlight too much! You want to concentrate on the important elements, not entire pages (use brackets for that).

- Use circles, boxes, triangles, squiggly lines, stars, etc.

- Make sure you don't plagiarize.

Literary Term Definitions [ edit | edit source ]

- Alliteration - the practice of beginning several consecutive or neighboring words with the same sound: e.g., "The twisting trout twinkled below"

- Allusion - A reference to a mythological, literary, or historical person, place, or thing: e.g., "He met his Waterloo"

- Flashback - A scene that interrupts the action of a work to show a previous event.

- Foreshadowing - The use of hints or clues in a narrative to suggest future action.

- Hyperbole - A deliberate, extravagant, and often outrageous exaggeration; it may be used for either serious or comic effect: e.g., "The shot heard 'round the world"

- Idiom - An accepted phrase or expression having a meaning different from the literal: e.g., to drive someone up the wall.

- Imagery - The words or phrases a writer uses that appeal to the senses.

- Metaphor - A comparison of two unlike things not using like or as:: e.g. "Time is money"

- Mood - The atmosphere or predominant emotion in a literary work.

- Oxymoron - A form of paradox that combines a pair of opposite terms into a signal unusual expression: Long shorts , Jumbo Shrimp , Sad Smiles

- Paradox - occurs when the elements of a statement contradict each other. Although the statement may appear illogical, impossible, or absurd, it turns out to have a coherent meaning that reveals a hidden truth: e.g., "Much madness is divinest sense."

- Personification - A kind of metaphor that gives inanimate objects or abstract ideas human characteristics: e.g., "The wind cried in the dark."

- Rhetoric - The art of using words to persuade in writing or speaking.

- Simile - A comparison of two different things or ideas using words such as "like" or "as": e.g., "The warrior fought like a lion."

- Suspense - A quality that makes the reader or audience uncertain or tense about the outcome of events.

- Symbol - any object, person, place, or action that has both a meaning in itself and that stands for something larger than itself, such as quality, attitude, belief, or value: e.g., a tortoise represents slow but steady progress.

- Theme - The Central message of a literary work. It is expressed as a sentence or general statement about life or human nature. A literary work can have more than one theme, and most themes are not directly stated but are implied: e.g., pride often precedes a fall.]

- Tone - The Writer's or speaker's attitude toward a subject, character, or audience; It is conveyed through the author's choice of words (diction) and details. Tone can be serious, humorous, sarcastic, indignant, etc.

- Understatement (meiosis, litotes) - The opposite of hyperbole. It is a kind of irony that deliberately represents something as being much less than it really is; e.g., "I could probably manage to survive on a salary of two million dollars per year."

Irony [ edit | edit source ]

There are three types of irony

When a speaker or narrator says one thing while meaning the opposite; sarcasm is a form or verbal irony: e.g., "It is easy to stop smoking. I've done it many times"

When a situation turns out differently from what one would normally expect; often the twist is oddly appropriate: e.g., a deep sea diver drowning in a bathtub is ironic

When a character or speaker says or does something that has different meaning from what he or she thinks it means, though the audience and other characters understand the full implications

- Literature for teens

Navigation menu

Student Resources

How to annotate a text.

Annotate (v): To supply critical or explanatory notes to a text.

Identifying and responding to the elements below will aid you in completing a close reading of the text. While annotations will not be collected or graded , doing them properly will aid in your understanding of the material and help you develop material for the assignments ( Textual Annotations, Weekly Journals, and Major Essays ) .

While Reading :

- Setting (When and/or Where)

- Important ideas or information

- Formulate opinions

- Make connections: Can you see any connections between this reading and another we have had?

- Ask open-ended questions (How…? Why…?)

- Write reflections / reactions / comments: Have a conversation with the text! Did you like something? Not like something?

I recommend using multiple colored highlighters for these elements. Characters: Green, Setting: Blue, Margin Notes: Yellow, etc.). And be as detailed as possible when making notes–You’d hate to go back to something later and not remember why you highlighted it!

After Reading :

- Summarize: Attempt to summarize the work in 2-3 sentences without looking at the material. I recommend limiting your summary to 2-3 sentences because any longer could risk turning into a “play- by-play” vs. an actual summary.

- Articulate the most important idea you feel the text is presenting. “The author wants us to know ___.” or “The moral of the story is ___.”

Complete these points in the margins at the end of the text or on the back of the last page.

Final Thought:

Annotating is as personal as reading, and there are MANY ways to annotate a work. This system is just a suggestion. For example, some people prefer to use colored highlighters, while others may prefer to use symbols (underlining key words, etc.). There’s no “right way” to annotate–If you already have a system, feel free to use what you are comfortable with. I am not going to hold you to a specific style, however whatever style you use should cover the major areas discussed above.

- Survey of American Literature II. Authored by : Joshua Watson. Provided by : Reynolds Community College. Located at : http://www.reynolds.edu/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Annotating Text. Authored by : Katie Cranfill. Located at : https://youtu.be/JZXgr7_3Kw4 . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- How to Annotate

Where to Make Notes

First, determine how you will annotate the text you are about to read.

If it is a printed article, you may be able to just write in the margins. A colored pen might make it easier to see than black or even blue.

If it is an article posted on the web, you could also you Diigo , which is a highlighting and annotating tool that you can use on the website and even share your notes with your instructor. Other note-taking plug-ins for web browsers might serve a similar function.

If it is a textbook that you do not own (or wish to sell back), use post it notes to annotate in the margins.

You can also use a notebook to keep written commentary as you read in any platform, digital or print. If you do this, be sure to leave enough information about the specific text you’re responding to that you can find it later if you need to. (Make notes about page number, which paragraph it is, or even short quotes to help you locate the passage again.)

What Notes to Make

Now you will annotate the document by adding your own words, phrases, and summaries to the written text. For the following examples, the article “ Guinea Worm Facts ” was used.

- Scan the document you are annotating. Some obvious clues will be apparent before you read it, such as titles or headers for sections. Read the first paragraph. Somewhere in the first (or possibly the second) paragraph should be a BIG IDEA about what the article is going to be about. In the margins, near the top, write down the big idea of the article in your own words. This shouldn’t be more than a phrase or a sentence. This big idea is likely the article’s thesis.

- Underline topic sentences or phrases that express the main idea for that paragraph or section. You should never underline more than 5 words, though for large paragraphs or blocks of text, you can use brackets. (Underlining long stretches gets messy, and makes it hard to review the text later.) Write in the margin next to what you’ve underlined a summary of the paragraph or the idea being expressed.

- “Depending on the outcome of the assessment, the commission recommends to WHO which formerly endemic countries should be declared free of transmission, i.e., certified as free of the disease.” –> ?? What does this mean? Who is WHO?

- “Guinea worm disease incapacitates victims for extended periods of time making them unable to work or grow enough food to feed their families or attend school.” –> My dad was sick for a while and couldn’t work. This was hard on our family.

- “Guinea worm disease is set to become the second human disease in history, after smallpox, to be eradicated.” –> Eradicated = to put an end to, destroy

To summarize how you will annotate text:

1. Identify the BIG IDEA 2. Underline topic sentences or main ideas 3. Connect ideas with arrows 4. Ask questions 5. Add personal notes 6. Define technical words

Like many skills, annotating takes practice. Remember that the main goal for doing this is to give you a strategy for reading text that may be more complicated and technical than what you are used to.

- Revision and Adaptation. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- How to Annotate Text. Provided by : Biology Corner. Located at : https://biologycorner.com/worksheets/annotate.html . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Image of taking notes. Authored by : Security & Defence Agenda. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/8NunXe . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Table of Contents

Instructor Resources (available upon sign-in)

- Overview of Instructor Resources

- Quiz Survey

Reading: Types of Reading Material

- Introduction to Reading

- Outcome: Types of Reading Material

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 1

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 2

- Characteristics of Texts, Part 3

- Characteristics of Texts, Conclusion

- Self Check: Types of Writing

Reading: Reading Strategies

- Outcome: Reading Strategies

- The Rhetorical Situation

- Academic Reading Strategies

- Self Check: Reading Strategies

Reading: Specialized Reading Strategies

- Outcome: Specialized Reading Strategies

- Online Reading Comprehension

- How to Read Effectively in Math

- How to Read Effectively in the Social Sciences

- How to Read Effectively in the Sciences

- 5 Step Approach for Reading Charts and Graphs

- Self Check: Specialized Reading Strategies

Reading: Vocabulary

- Outcome: Vocabulary

- Strategies to Improve Your Vocabulary

- Using Context Clues

- The Relationship Between Reading and Vocabulary

- Self Check: Vocabulary

Reading: Thesis

- Outcome: Thesis

- Locating and Evaluating Thesis Statements

- The Organizational Statement

- Self Check: Thesis

Reading: Supporting Claims

- Outcome: Supporting Claims

- Types of Support

- Supporting Claims

- Self Check: Supporting Claims

Reading: Logic and Structure

- Outcome: Logic and Structure

- Rhetorical Modes

- Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

- Diagramming and Evaluating Arguments

- Logical Fallacies

- Evaluating Appeals to Ethos, Logos, and Pathos

- Self Check: Logic and Structure

Reading: Summary Skills

- Outcome: Summary Skills

- Paraphrasing

- Quote Bombs

- Summary Writing

- Self Check: Summary Skills

- Conclusion to Reading

Writing Process: Topic Selection

- Introduction to Writing Process

- Outcome: Topic Selection

- Starting a Paper

- Choosing and Developing Topics

- Back to the Future of Topics

- Developing Your Topic

- Self Check: Topic Selection

Writing Process: Prewriting

- Outcome: Prewriting

- Prewriting Strategies for Diverse Learners

- Rhetorical Context

- Working Thesis Statements

- Self Check: Prewriting

Writing Process: Finding Evidence

- Outcome: Finding Evidence

- Using Personal Examples

- Performing Background Research

- Listening to Sources, Talking to Sources

- Self Check: Finding Evidence

Writing Process: Organizing

- Outcome: Organizing

- Moving Beyond the Five-Paragraph Theme

- Introduction to Argument

- The Three-Story Thesis

- Organically Structured Arguments

- Logic and Structure

- The Perfect Paragraph

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Self Check: Organizing

Writing Process: Drafting

- Outcome: Drafting

- From Outlining to Drafting

- Flash Drafts

- Self Check: Drafting

Writing Process: Revising

- Outcome: Revising

- Seeking Input from Others

- Responding to Input from Others

- The Art of Re-Seeing

- Higher Order Concerns

- Self Check: Revising

Writing Process: Proofreading

- Outcome: Proofreading

- Lower Order Concerns

- Proofreading Advice

- "Correctness" in Writing

- The Importance of Spelling

- Punctuation Concerns

- Self Check: Proofreading

- Conclusion to Writing Process

Research Process: Finding Sources

- Introduction to Research Process

- Outcome: Finding Sources

- The Research Process

- Finding Sources

- What are Scholarly Articles?

- Finding Scholarly Articles and Using Databases

- Database Searching

- Advanced Search Strategies

- Preliminary Research Strategies

- Reading and Using Scholarly Sources

- Self Check: Finding Sources

Research Process: Source Analysis

- Outcome: Source Analysis

- Evaluating Sources

- CRAAP Analysis

- Evaluating Websites

- Synthesizing Sources

- Self Check: Source Analysis

Research Process: Writing Ethically

- Outcome: Writing Ethically

- Academic Integrity

- Defining Plagiarism

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Using Sources in Your Writing

- Self Check: Writing Ethically

Research Process: MLA Documentation

- Introduction to MLA Documentation

- Outcome: MLA Documentation

- MLA Document Formatting

- MLA Works Cited

- Creating MLA Citations

- MLA In-Text Citations

- Self Check: MLA Documentation

- Conclusion to Research Process

Grammar: Nouns and Pronouns

- Introduction to Grammar

- Outcome: Nouns and Pronouns

- Pronoun Cases and Types

- Pronoun Antecedents

- Try It: Nouns and Pronouns

- Self Check: Nouns and Pronouns

Grammar: Verbs

- Outcome: Verbs

- Verb Tenses and Agreement

- Non-Finite Verbs

- Complex Verb Tenses

- Try It: Verbs

- Self Check: Verbs

Grammar: Other Parts of Speech

- Outcome: Other Parts of Speech

- Comparing Adjectives and Adverbs

- Adjectives and Adverbs

- Conjunctions

- Prepositions

- Try It: Other Parts of Speech

- Self Check: Other Parts of Speech

Grammar: Punctuation

- Outcome: Punctuation

- End Punctuation

- Hyphens and Dashes

- Apostrophes and Quotation Marks

- Brackets, Parentheses, and Ellipses

- Semicolons and Colons

- Try It: Punctuation

- Self Check: Punctuation

Grammar: Sentence Structure

- Outcome: Sentence Structure

- Parts of a Sentence

- Common Sentence Structures

- Run-on Sentences

- Sentence Fragments

- Parallel Structure

- Try It: Sentence Structure

- Self Check: Sentence Structure

Grammar: Voice

- Outcome: Voice

- Active and Passive Voice

- Using the Passive Voice

- Conclusion to Grammar

- Try It: Voice

- Self Check: Voice

Success Skills

- Introduction to Success Skills

- Habits for Success

- Critical Thinking

- Time Management

- Writing in College

- Computer-Based Writing

- Conclusion to Success Skills

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.4: Reading and Annotating

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 101129

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

The first step in writing a literary analysis essay is actually completing the reading. Sometimes the professor will give you a prompt before you read. If this is the case, look for material which relates to the prompt as you read. If the professor did not give you a prompt, look for any material in the assigned reading that piques your interest or relates to class discussions. Highlight or underline any moments in the reading which stick out to you: something you don't understand, something that relates to a topic you care about, or something weird or surprising. Keeping track of patterns, themes, or literary devices is a great way to engage with a work of literature and prepare for a future discussion or essay.

Completing the Reading

One time, I was talking with my sister-in-law about her experience in nursing school. Whereas her brother had barely achieved Cs in college, she somehow maintained a 4.0, even though she was simultaneously working and caring for her two young daughters.

"What is your secret to success?" I asked.

"Actually doing the assigned readings," she laughed, "most of my peers didn't. And it showed."

As a college professor who teaches reading-heavy classes, this is not a shock to me. After all, most students taking the required writing and literature courses do not wish to become English majors. They sometimes see their literature class as a means to an end: at best, a stepping stone towards their future career; at worst, a time-suck of hoops to jump through. Also, because of today's gig economy, many students are juggling multiple jobs in addition to multiple college classes. This makes it tempting for students to want to skip the readings and just read SparkNotes. Truth be told, students who pursue this method, depending on their BSing skills, might be able to pass a literature class. But for the vast majority of students, this popular high school tactic will not work at the college level. More importantly, it means students miss out on many of the exciting benefits of diving deep into analysis, discussion, and engaging with the text.

Of course, I want my students to fall in love with the written word. I want my passion for literature to be contagious, to light students' hearts and minds on fire with a hunger for the beauty of syntax and diction and literary devices. But I also completely understand that students have limited time. Therefore, I recommend prioritizing the writing process so students can make the most efficient use of their time. In the long run, while it might seem like skipping the readings saves time, completing the readings is actually the best way for students to optimize their time. This is because a strong essay depends on a deep understanding of the literature. If the class features examinations, these almost always test students on whether they completed and understand the readings. Finally, class will be more fun for students if they understand what their peers are talking about in class discussion, and what their professor is talking about during lectures.

Students who complete the readings and annotate as they go will find it much easier to flip back through their notes to find relevant quotations and information. They usually break the readings into small, manageable chunks of twenty to thirty minutes at a time. This helps their brains absorb the information better and retain information for writing and tests.

Students skipping reading often end up performing more work when it comes to writing an essay because they will spend so much time looking up text summaries on the internet (which may or may not be accurate or pertain to the intricacies of the assignment). They will also have to go back and re-read the text to find quotations that fit their prompt. Their essays usually fail because they do not fulfill the in-depth analysis required by the assignments.

So, long story short: even the most practically-minded, time-crunched students would do well to perform the readings. And, while in pursuit of success, a previously literature-averse student might find themselves liking literature more than they thought they would. Just like watching a favorite movie or show, reading a good book can be fun and relaxing!

Active versus Passive Reading

Many students, when first reading academic material, read it like they would a timeline of Facebook or Instagram posts: not fully attentive, skimming over the material in search of something interesting. Or they might read them with full attention, but simply read without questioning or engaging with the material. The difference between a student who is successful in a literature class and a student who is not successful is often that the successful student participates in active reading.

In a literature class, students encounter a lot of literature, written by many different authors. Annotating, or taking notes on the assigned literature as you read, is a way to have a conversation with the reading. This helps you better absorb the material and engage with the text on a deeper level. There are several annotation methods. These are like tools in a student's learning utility belt. Try them all out to discover which tools or combinations of tools help you learn best!

Margin Notes & Highlighting

One of the best ways to interact with a text is to write notes as you read. Underlining and/or highlighting relevant passages, yes, but also responding to the text in the margins. For instance, if a character I love makes a bad choice (like Sydney Carton in Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities ), I will write, "Nooooo, Sydney Carton, don't sacrifice yourself for Lucie's sake!" This helps me remember the events of the plot. Many students also find it helpful to summarize each chapter or section of the literature as they read it. For example, a student said it was helpful for them to draw a picture representing every stanza of "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" by William Wordsworth to help them understand what was being said. Other ideas include:

- Circling unfamiliar words

- Writing questions in the margins

- Color-coded highlighting to track various literary devices (i.e., blue for metaphors, pink for symbolism, and so forth)

Sticky Notes

For students who would like to sell their textbooks back to the bookstore, writing notes in the margins might not be a practical choice, as it may devalue the textbook or the bookstore may refuse to take it back. For these students, I recommend using sticky notes instead. If sticky notes are cost-prohibitive, most colleges have plenty of scrap paper students can use as bookmarks to stick between pages. This is also an eco-friendly way to re-use paper!

Reading Journal

Another option many students find helpful is keeping a reading journal. Students can write notes in their journals as they read. This helps students keep track of readings and materials in a chronological fashion. Just like when annotating the text directly or upon sticky notes, the most effective use of a reading journal, for learning purposes, is going to be active engagement with the text rather than passive absorption. That is, try to summarize the plot of what you read every time you read. Also, ask questions about the text. If you can record quotes and paraphrase along with in-text parenthetical citations (i.e., the page number where you found the material), this will optimize your time because you already have quotes ready to go when you write an essay!

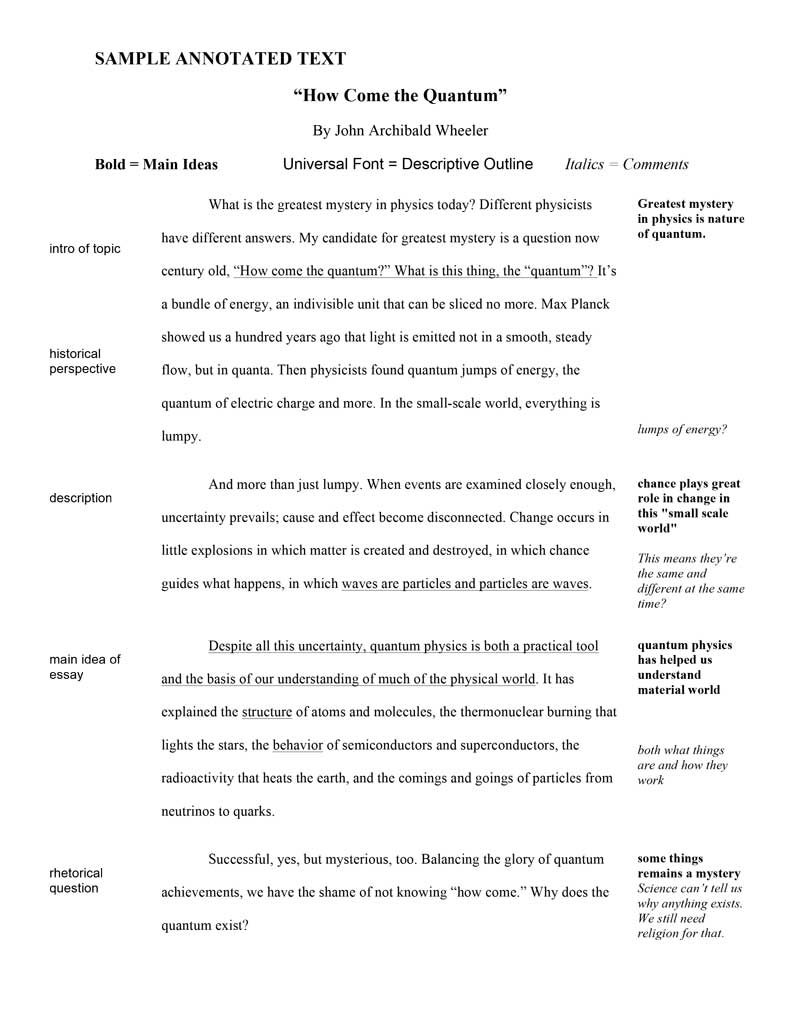

Example of an Annotated Passage

Using the guidelines above, let's consider this excerpt from a scholarly article by Jacob Michael Leland, "'Yes, That is a Roll of Bills in My Pocket': The Economy of Masculinity in The Sun Also Rises."

A great deal of critical attention has been paid to masculine agency and its displacement in Ernest Hemingway's fiction. The story is familiar by now: the Hemingway hero loses some version of his maleness to the first World War and he replaces it with a tool—in Upper Michigan, a fishing rod or a pocket knife; in Africa, a hunting rifle—a new object that emblematizes his mastery over his surroundings and whose status as a fetishized commodity and Freudian symbolic significance is something less than subtle. In The Sun Also Rises , this pattern repeats itself, but with important differences that arise from the novel's cosmopolitan European setting. Mastery over the elements, here, has more to do with economic agency and control over social relationships than with nature and survival. The stakes are different, too; in the modern European city, the Hemingway hero recovers not only masculinity but also American identity in social and sexual interaction. (37)

In researching The Sun Also Rises for a project, Ling Ti found Leland's article. What follows is her annotated copy of the above excerpt:

Reflecting on Assigned Literature

Studies show reflecting on reading is one of the best ways to learn. This is called metacognition, or thinking about thinking. It is a way to keep track of the knowledge you have learned as you go. Students who reflect on their reading and learning tend to, as a whole, perform better on essays and examinations. So how can you take advantage of this skill?

If you have a prompt, choose a prompt and read through the assigned literature again, noting any quotes which may relate to the assigned topic. It is recommended at this point that you keep track of your observations in a document: either on a computer (Word, Google Docs) or on a physical piece of paper. Write down any quotations along with page numbers (fiction, nonfiction), line numbers (poem), or act, scene, line numbers (drama). This way, you have all potential evidence in one place, and it makes for easy in-text citations when it comes to knitting the evidence together to form an essay. In fact, it is highly recommended that students start an informal Works Cited page to keep track of every source consulted. This makes it much easier to avoid plagiarism by practicing ethical citation habits. For more information about citations, please see the Citations and Formatting Chapter.

Start with a hypothesis or focus but be willing to refine, adjust, or completely discard it if new evidence refutes it. An essay is not a stagnant piece, but a living, breathing thought experiment. Many students feel reluctant to change their thesis or major parts of their essays because they are afraid it means the previous writing was wasted. As a professional writer, editor, and scholar, I want to clue students in on a secret:

There is no such thing as wasted writing.

Even writing that does not end up in the final draft is worthwhile because it is a chance to experiment with ideas. It helps students find a path toward stronger ideas. Just like a gardener might allow branches of a tree to grow to see which ones bear flowers and fruit and then prune the weak, unproductive branches to make the plant stronger and more beautiful, so too must a writer be willing to cut out branches of reasoning which no longer serve the essay. But before you know which ideas or thoughts are worth pursuing, you first have to give them space to grow. You never know what idea branches might prove fruitful!

Contributors and Attributions

- Adapted from "Reading Like a Professional" in Writing and Literature: Composition as Inquiry, Learning, Thinking, and Communication by Dr. Tanya Long Bennett of the University of North Georgia, CC BY-SA 4.0

What Are Annotations?

Annotation, n..

1. The action of annotating or making notes.

3. a. concr. (usually pl. ) A note added to anything written, by way of explanation or comment.

Oxford English Dictionary

The definition of the OED (see right) seems straightforward enough. Thus our project’s guidelines incorporate a similar, yet expanded definition in the very first paragraph: “Annotations are little notes that provide useful information to enhance the understanding of a text. There are different categories of annotations like vocabulary, historical context, etc. Depending on the text, some categories will be more important, some less, and some will not be used at all.” The conscious application of these categories just starts to describe our understanding of annotation and the (meta-)reflection on annotation in practice and theory.

It is part of the “Annotating Literature” project to develop the practice of commenting on a text. Annotations, as any kind of text, bring a set of questions concerning their usage which are useful to think about in this context. What kind of information is given? To whom it is given? And how can it be displayed to the greatest benefit? To exemplarily tackle these problems, we began by a “building” categories (the one referred to in the last paragraph) for different kinds of information and/or knowledge. The most basic kind of annotation is a simple dictionary check to help readers with English as a second language. But it also can include etymological information on, or the historic use of the annotated word , which is especially helpful with older texts. In addition to the basic vocabulary category, another fundamental kind of comment is the fact check. This “Factual” category encompasses crossreferencing data from history, geography, science etc. Comments on a text’s structure and style take note of e.g. the metre of a poem or the narratorial situation of a prose text. Adding to the text are the contextual categories which often connect the literary text with its times or maybe other texts (intertextual). In longer works it is useful to introduce an intratextual comment type that refers to the repeated use of motives or vocabulary within the same text. Higher level annotation might add a “theoretical” category that adds conceptual framework from philosphy or theology implied by the literary text or points to special ways to read the text from literary criticism. Each text might have a specific set of comment categories.

Which categories to display in a text also depends on the target audience. For a hobby reader, or a foreign language reader, the basic categories of vocabulary or facts might be enough. If the annotated edition is provided for the purpose of higher studies or academic use, the knowledge imparted has to be “deeper” contentwise. The different approaches possible have to be wholly reliable, and thus citable – a necessity in a text’s academic use.

How the results of a work are displayed also plays a crucial role in the development of what were traditional footnotes in books until the internet became a major medium. Modern electronic ways of packaging information, sorting it to generate a highly customized output, have the power to change the whole structure of annotation. A book in its “printedness” has to specify exactly what information it has to give at a certain material point on the paper, and once printed, the information is likely to become the fixed metatext of the literary work in this specific edition. Electronic publishing offers up tools to change this by its possiblities in linking informations in new ways or adding different kinds of information in that it can incorporate multiple media: graphic content, audio content, traditional writing or directly integrating other works via hyperlink. The idea of “annotation” therefore has changed: every kind of information can become part of an annotation. To develop a viewer, or a screen reader, that not only displays these amounts of information in a productive, orderly, easy-to-use fashion, but at the same time enables the recipient to exactly choose what content he’s interested in, is therefore one of the’s projects goals.

Annotation is an informative literary practice. Glosses, rubrics, scholia, and labels provide information about the reader and the reader’s private or social reading practices, about the text, and about relevant scholarly, interest-driven, professional, and political contexts.

2: Annotation Provides Information

The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers. —Toni Morrison, Nobel Lecture

Toni Morrison was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1993, for “novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import.” In her Nobel Lecture, Morrison noted how language, whether spoken or written, can limn - or describe and detail - life. Limn is a distinctive verb; derived from the Latin illuminare , meaning to “make light” or “to illuminate,” the word has been used throughout literary history to generally describe - and, in some cases, to convey the literal illustration of - a manuscript. Can annotation limn, or help to describe? And if so, what does such annotation do? Let’s return to our annotated copy of Beloved .

Perhaps as a student you highlighted key passages of Beloved , jotted notes in the margins, or repeatedly scribbled stars and question marks, all to better illustrate your growing literary knowledge. Although your annotation of Beloved may be idiosyncratic, such activity extends a lineage of historic reading practices evident throughout the early modern period (approximately 1500-1800). Heidi Brayman Hackel’s study of that period’s book use among “less extraordinary readers” - and that would be everyday folks, like us - suggests people added various types of marks while reading their books. 1

Marks of active reading, like underlining, indicated sustained engagement. Marks of ownership, like a signature, distinguished books as valued, physical objects. And marks of everyday recording, perhaps unrelated to the book’s content, added ancillary information. In Brayman Hackel’s assessment, with varied annotation practices “the book takes on a different role: as intellectual process, as valued object, and as available paper.” 2 Perhaps your annotation of Beloved illustrated burgeoning intellectual acumen, or how much you valued the book, or perhaps it was just some paper to record the latest hallway gossip. It was George Steiner, the literary critic, who once suggested an intellectual was “quite simply, a human being who has a pencil in his or her hand when reading a book.” 3 However you may have used that pencil while reading Morrison’s Beloved , your annotation provided information.

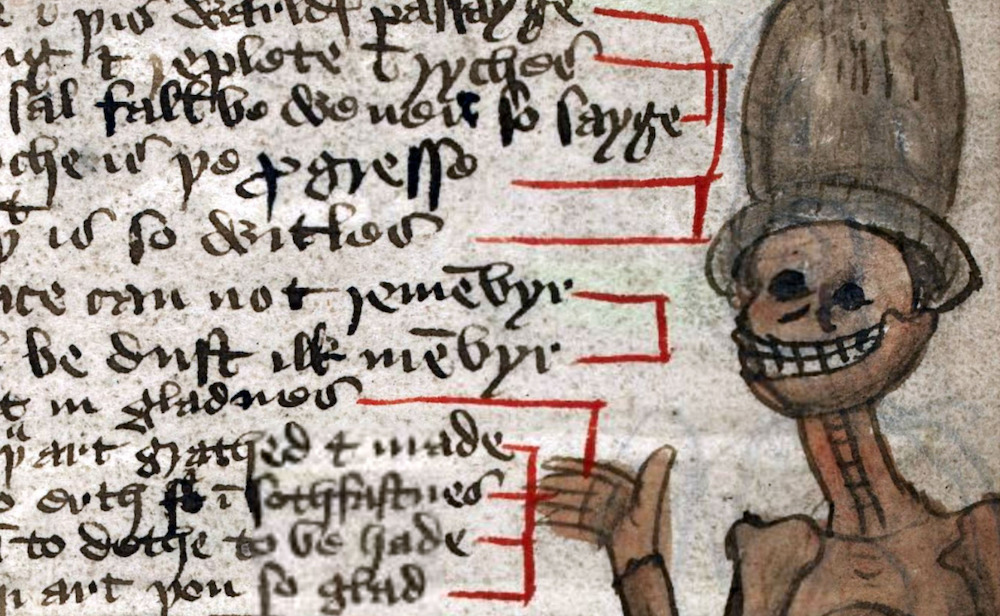

Annotation is an informative literary practice. Annotation, as with our example of Beloved , can signal different information to different readers. Notes of active reading may have better aided your future essay-writing and study, or have indicated to your teacher that you’re no dummy. Notes of ownership or recording may have also provided a stranger, who subsequently acquires this “used” copy from a bookstore, with insight about private noticing and musing. We know from those who have studied the history of books and reading practices that annotation was both ubiquitous and habitual by the 1500s, not long after the invention of the printing press and the growth of print culture. Such Medieval annotation also included drolleries , or small decorative images, drawn in the margins; what information might we glean from killer rabbits? 4

Figure 7: Drollery/killer rabbit

By the 1600s, “graffiti” among the early modern book routinely provided information by adding detail, indicating references (particularly to scripture and classical literature), emphasizing importance, translating or clarifying terminology, and organizing the text. 5

As with annotation today, notes can provide information about the reader and the reader’s private or social reading practices, about the text and relevant scholarly or political contexts, or maybe about a flower once pressed between the pages of a book.

Forms that Inform

As we will discuss throughout this chapter, what kind of information annotation provides, the contexts in which this information is written and received, and the modes through which this information is interpreted collectively influence how annotation is authored, understood, and trusted. To more easily examine the forms of annotation that provide information - as well as to foreground terminology used throughout the book - it’s useful at this point to distinguish among a few types of notes that, in both historic and contemporary contexts, have been added to texts.

In her oft-cited Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books , Heather Jackson, a professor of English at the University of Toronto, presents an extensive study of book annotation from 1700 into the twentieth century. Jackson focuses exclusively upon marginalia , or discursive and responsive notes written by hand anywhere in a book (and not only in the book’s margin). While non-verbal markings, including evidence of readers’ attention and engagement via asterisks or characters, are not marginalia according to Jackson, we do consider this repertoire of signs and symbols an important form of annotation (particularly among digital texts and contexts). Among book marginalia, however, Jackson categorizes three “basic particles:” the gloss , the rubric , and the scholium . Glosses, rubrics, and scholia each provide different types of information.

Remarking upon the complex relationships among readers, text, and annotation, the scholar James Nohrnberg once suggested: “Everything we read is thus a gloss upon, or a translation of, some original improvement upon silence.” 6 While that may be true, in our book we appreciate Jackson’s suggestion that a gloss serves the explicit purposes of translation and explanation. Glosses, in her assessment, were often added to assist book readers with foreign and obscure words. The utility of glosses is underscored by the historian Anthony Grafton, who observed that “the margins of manuscripts and early printed texts in theology, law, and medicine swarm with glosses which, like the historian’s footnote, enable the reader to work backwards from the finished argument to the texts it rests on.” 7 Glosses are literal and instructive. And in their more expansive and curated form, glosses comprise what we know of today as a glossary.

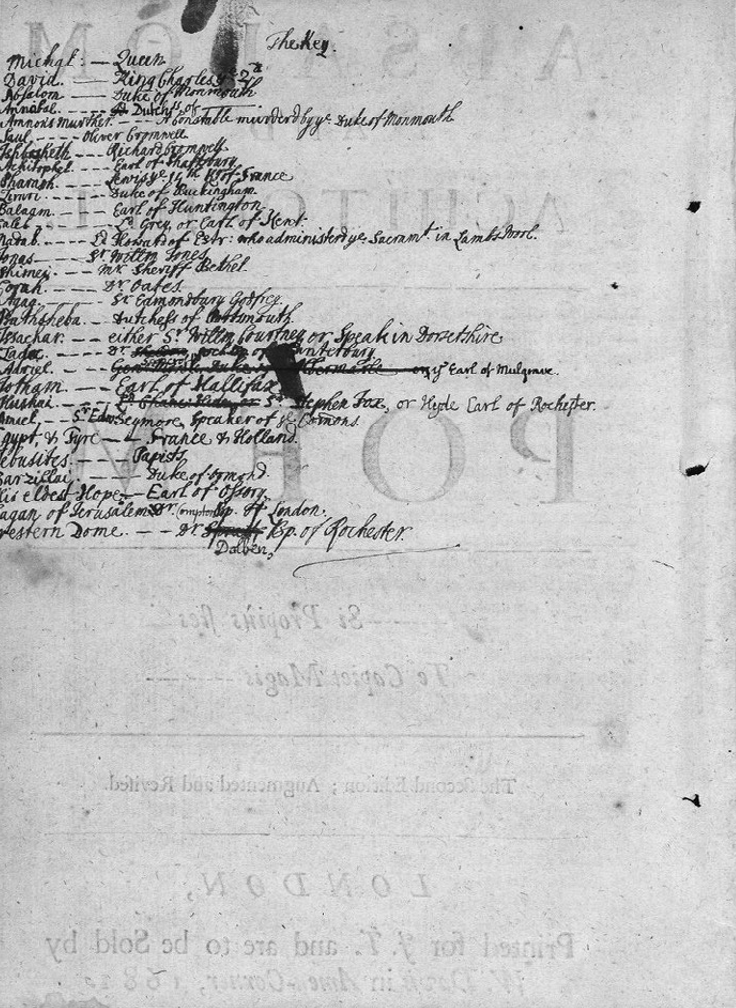

In addition to the gloss, book marginalia may also include a second form of annotation known as a rubric. The Latin rubrica translates as “red” and is the traditional color of rubrics found throughout medieval manuscript annotation. Jackson describes rubrication as the “scribal practice of writing or marking certain words in red,” with rubrics often corresponding to chapters, sections, or headings. 8 The scholar of medieval literature Stephen Nichols suggests rubrics are an “extradiegetic intervention,” intentionally written in a color of ink different from the main text (hence red) so as to provide “metacritical perspective.” 9 Rubricated manuscripts, like the thirteenth century French manuscript in Figure 8 (also further proof that doodling in the margins is a time-honored phenomenon), demonstrate how such medieval annotation predated forms of book marginalia by centuries. Together, and in a more contemporary print context, a group of rubrics becomes a book’s index.

Figure 8: French manuscript

A third form of marginalia that provides information is the scholium. Often referred to using the plural scholia, this type of annotation introduces to the text a new note, according to Jackson, “From outside the work that some scholar (usually) has judged relevant to it.” 10 Scholia can elucidate an idea, share a useful example, provide a historical reference, or either affirm or contradict the author. Among famous instances of scholia are those added to the oldest copy of Homer’s Iliad , known as the Venetus A. This 645-page parchment book, written by Byzantine Greek scribes in the tenth century, includes both the full text of the Iliad and two sets of marginal scholia based upon the scholarship of Aristarchus. 11 Scholia, when gathered together as complementary to a source text, established the literary genre of commentary. 12

As discussed, our interest in annotation extends beyond book marginalia and print culture. Accordingly, our survey of annotation forms that inform should also include more than glosses, rubrics, and scholia (and drolleries of killer rabbits). Recall that we introduced annotation as multimodal notes in our previous introduction. Annotation, even when written, may be added to texts that communicate in multiple complementary modes. The history of cinema and the development of the motion picture industry relied upon text that was filmed and then manually edited into a movie. Silent era films featured intertitles , or text that shared characters’ dialogue or explained narrative elements. One of the most famous intertitles in movie history is still featured in films produced today: “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away….”

Other types of annotation added to movies and television include subtitles that provide translation from one language to another. Textual and graphical information - picture the always-crawling news ticker - appear via annotation in the lower third of many broadcasts. Furthermore, multimodal annotation is critical for information accessibility. Closed captioning is a form of annotation that provides needed visual information, including the ability to read along when watching a public television at the gym or bar. And Twitter now allows users to add text descriptions to a tweet’s image that can be read aloud by assistive screen reading technology.

Forms of annotation - like subtitles and closed captions - provide information. This is why we previously suggested annotation is an everyday activity. Among scholarly traditions, forms of marginalia provide intellectual lineage to substantiate claims and offer the academic receipts relevant to skeptics and stalwart researchers. And annotation provides information privately or for self-interest. Whether doodling atop assigned course materials or adjusting a recipe, annotation can elevate a text from generic to personally sacred. As Edgar Allen Poe wrote, in 1844, “In the marginalia , too, we talk only to ourselves; we therefore talk freshly - boldly - originally - with abandonnement - without conceit.” 13

Figure 9: Poe quote

Another form of annotation that informs are labels. Labels provide various kinds of information. When you’re at the grocery store, a label informs you that the red stuff in that jar is strawberry jam, rather than cherry. If you’re training a computer algorithm using image samples, a label will inform the program “this is a cat,” and not a cheeseburger - despite some visual similarity and the former perhaps having the latter.

Labels are like a gloss, literal and instructive. As a note added to a text, labels provide useful and contextual information. Texting a friend with your iPhone? Apple’s Messages app allows you to label a message with symbols - like a heart or a thumbs up - to add information.

Figure 10: text label

Writing computer code? The programming language Java includes a set of standard annotations, all of which begin with the @ symbol, to label code and provide additional information about how certain methods should be performed. You likely read labels as annotation added to graphs and other visualizations, as with the graph of global GDP featuring labeled historical events and geographic regions. These are just some examples of the plethora of labels appended to texts in everyday contexts.

Figure 11: GDP

When you text a friend, that message includes a time stamp, a confirmation that it was “delivered,” and - depending on whether your friend has the feature enabled - a confirmation that the recipient read the message. This addition of labeled information is increasingly automated. Similarly, when using social networks we often know when a message was sent, from what location, and even from what kind of device. This additional information is conveyed through words, numbers, and symbols - including emojis and GIFs - added as labels to the primary message. As discussed in our introduction, symbols like the “Like” buttons of Twitter and Facebook layer a label upon a text message. As everyday forms of annotation, these labels reflect the pervasiveness of notes attached to texts both automatically and also purposefully. This additional information imperceptibly shifts our relationship to texts and notes.

Let’s consider in more detail two important uses of annotation as labeling: machine learning and scientific research. Both cases underscore the ubiquity of annotation and the utility of labeling to make meaning and produce new knowledge.

Have you ridden in an autonomous vehicle? Maybe you only trust self-driving cars as far as you could throw one. Whatever the case, the inevitable growth in autonomous transportation - among ride-hailing services, long-haul trucking, and autopilot features in luxury cars - will be aided, in part, by annotation. How so?

Consider all the various road signs - and the myriad colors, shapes, lights, and electronic messages of those signs - that influence your ability to safely commute from home to work and back again. Then add to that all the other vehicles, unanticipated obstacles, cyclists, and pedestrians on the go. How do artificial intelligence (AI) systems that pilot an autonomous vehicle distinguish among these variables to make intelligent, safe, and accurate decisions? The AI needs to learn from lots and lots of data. 14 And whether with AI that powers autonomous transportation, customer service bots, precision agriculture, product recommendations, or targeted advertising, that data need to be labeled.

In simplest terms, annotation in the area of machine learning is the process of labeling data. Data like text, images, or audio are routinely gathered from cameras, sensors, and social media. And these data are often unstructured. In order to train AI systems to make sense of and also make informed decisions based upon these data, it’s necessary for data to be identified. That’s were annotation plays a role. And so, too, many people whose jobs are primarily dedicated to labeling data. The manual labeling of data - that is, annotation by people - remains a preferred method, though it is time-intensive, not error-proof, and may be biased. 15 Because automated annotation - annotation by AI - is much faster, much cheaper, and ever-more accurate, there is vigorous debate about the merits of manual versus automated data labeling. In some instances, people check samples of automatically labeled data to ensure AI accuracy, or people rely upon automated annotation suggestions to improve their labeling. 16

There are now numerous data annotation companies specializing in all manner of services, technologies, and processes for labeling data. And business is booming, both in the United States and globally. 17 Companies like Infolks and iMerit employ thousands of workers across India who manually label images using techniques like bounding box and contour annotation. The labeled images will train autonomous vehicle algorithms to better identify road obstacles and conditions. 18 And techniques for semantically tagging data go beyond mere labeling to add new information so that AI can learn to establish links, filter, and make inferences or predictions. Billions of images, billions of text segments, and billions of social media data are now annotated each year to power the intelligent algorithms that many of us take for granted as we shop, work, commute, watch recommended movies, and listen to suggested playlists.

Just as labeling has helped advance business innovation, so too has data annotation fueled scientific research and discovery.

One of the most famous examples of data labeling is the Human Genome Project, the effort that successfully identified and mapped all the genes comprising human DNA. To do so, scientists used genome annotation processes that added information - such as the name, location, and function of genes - to labeled and sequenced genetic material. 19 Techniques for the manual and automatic labeling of genetic information continue to improve the accuracy, speed, and scale of such annotation, as with RNA and proteins. 20 Similar processes have established databases of annotated genomes for vertebrates like mice and chimpanzees, 21 as well as for worms and Drosophilidae , the most commonly studied laboratory organism. 22