OUTSIDE FESTIVAL JUNE 1-2

Don't miss Thundercat + Fleet Foxes, adventure films, experiences, and more!

GET TICKETS

Women Writing About the Wild: 25 Essential Authors

A primer on who to start reading and who you've been overlooking for too long.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! >","name":"in-content-cta","type":"link"}}'>Download the app .

Women who write about the wild cannot be easily labeled. They are conservationists, scientists, and explorers; historians, poets, and novelists; ramblers, scholars, and spiritual seekers. They are hard to pin down but for their willingness to be “unladylike,” to question, and to seek.

The following list is in no way definitive, but if you want a primer on some of the best nature writing you probably haven’t read yet, you’d do well to start with these 25 women. We present them in order from historical to contemporary.

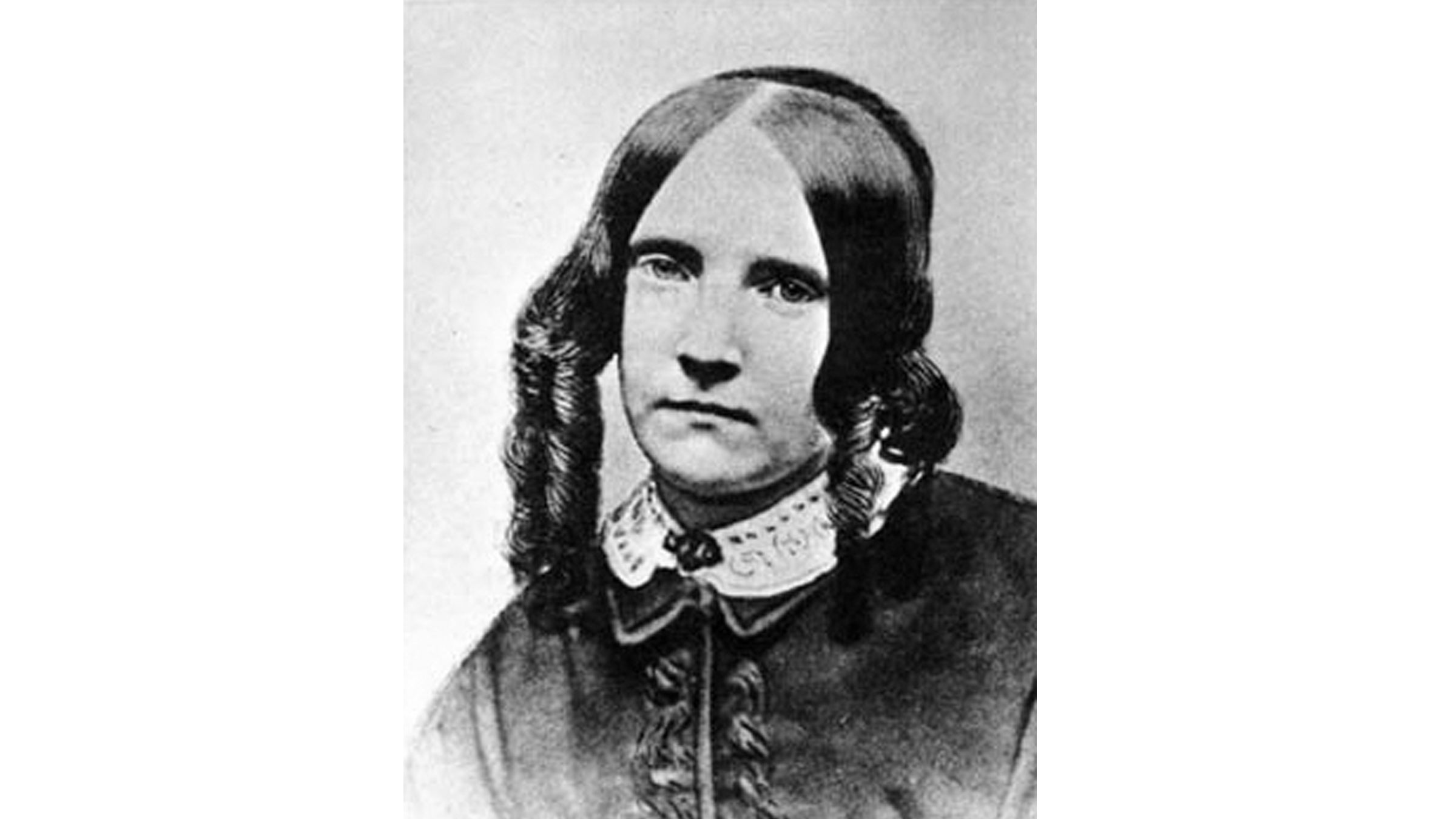

Susan Fenimore Cooper

Henry David Thoreau is considered to be the father of American environmentalism, but he owes much of his philosophy to nature writers who came before him—and one writer in particular is overdue for credit. For his 1854 book Walden , Thoreau consulted Rural Hours , written in 1850 by Susan Fenimore Cooper, daughter of novelist James Fenimore Cooper. Rural Hours is a record of a year around Cooperstown, New York, where she lived, and it’s the first American book of place-based nature observations.

Despite its anonymous publication “by a Lady” and Cooper’s status as an amateur naturalist, the book caught the attention of leading scientists of the time. Cooper lamented the changing landscape and anticipated concepts central to ecology when few others did. And she did so personally and lyrically: “The varied foliage clothing in tender wreaths every naked branch, the pale mosses reviving, a thousand young plants rising above the blighted herbage of last year in cheerful succession.” Choose the 1998 University of Georgia Press edition of Rural Hours —the 1968 version cuts 40 percent of the original text and much of Cooper’s environmental commentary.

Gene Stratton-Porter

At a time when most women were homemakers, Gene Stratton-Porter was a prolific novelist, naturalist, and conservationist. She also wrote at a time when the Limberlost wetlands and swamps of her native Indiana were vanishing: 13,000 acres of this biodiverse area were drained for agriculture by 1913. Before they disappeared, Stratton-Porter captured the wetlands’ rich habitat by setting her internationally popular fiction there. This includes two novels: Freckles (1904) and A Girl of the Limberlost (1909), the latter of which influenced many young girls, including author Annie Dillard, profiled below, and was adapted to film four times. The self-reliant teenage heroine, Elnora, loved the outdoors, especially hunting moths. Stratton-Porter made a fortune from these romantic novels, with a stunning 10 million copies sold by 1924. She also wrote ten natural history books between 1907 and 1925. Stratton-Porter was the first American woman to form a movie and production company, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions, Inc., and used her position to help conserve parts of the Limberlands you see in Indiana today.

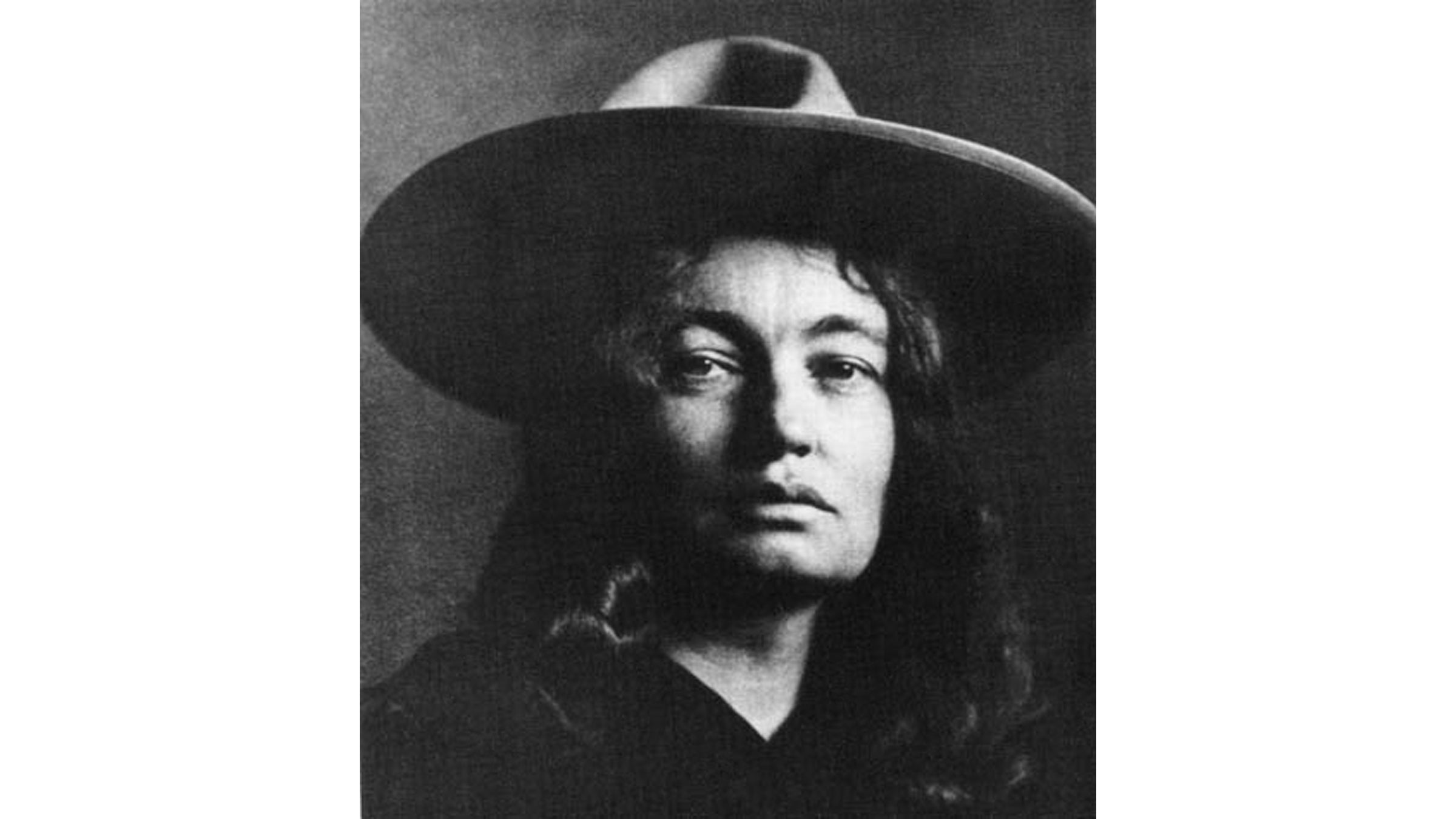

Mary Austin

Anyone interested in the natural history of Southern California—what came before sprawl, smog, and Kardashians—should pick up Mary Austin’s 1903 classic The Land of Little Rain . More than a century ago, Austin presciently captured a disappearing cultural and physical landscape: the people, plants, politics, and sense of place in California’s Owens Valley. She did so ten years before the city of Los Angeles diverted the Owens River in 1913, a period in history known as the California Water Wars and immortalized in the film Chinatown . Austin disregarded prescribed gender roles about how women should explore and talk about the natural world, and she did it with wit, verve, and lyricism. You can hear her wry voice here, channeling Jane Austen: “It is the proper destiny of every considerable stream in the West to become an irrigating ditch.” She is known for writing essays, poetry, plays, and novels; for her pioneering work in science fiction; and as an advocate of indigenous cultures.

Karen Blixen-Isak Dinesen

Baroness Karen von Blixen-Finecke was also Baroness Badass: She shot lions, had a love affair with English game hunter Denys Finch Hatton, and was enamored with the idea of vultures picking her remains clean when she died. She wrote under the pen name Isak Dinesen in Danish, French, and English, including the superlative Out of Africa , her 1937 memoir made into a film about running a 4,000-acre coffee plantation in British East Africa, now Kenya, from 1914 to 1931. Though some readers feel that a European arrogance appears at times in her writing, she wrote with great feeling and affection about the people and landscape of the African continent: “The sky was rarely more than pale blue or violet, with a profusion of mighty, weightless, ever-changing clouds towering up and sailing on it, but it has blue vigour in it, and at a short distance it painted the ranges of hills and the woods a fresh deep blue.”

Nan Shepherd

“It’s a grand thing, to get leave to live.” —Nan Shepherd

Men have written hundreds of mountaineering books, but who wrote one of the best? A Scottish poet and novelist named Anna “Nan” Shepherd. The Living Mountain is her meditation on high and holy places: a walk into rather than up mountains, a caress rather than a conquer of peaks, a whisper of “let’s see closer” rather than a testosterone-fueled bugle of “ I did it!”

She writes, “Often the mountain gives itself most completely when I have no destination but have gone out merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend, with no intention but to be with him.” Shepherd was a localist who deeply immersed herself in the Cairngorms, Scotland’s eastern Highlands. She swam in streams, watched wildlife, and slept outdoors—a deep engagement recounted in luminescent prose. The Living Mountain was written during World War II, when Shepherd often went “stravaigin”—a Scottish term for wandering. For reasons unknown, she left the manuscript in a drawer for nearly 40 years. It was published late in her life, in 1977. Today, Shepherd’s writing is justifiably experiencing a renaissance—so much so that the Royal Bank of Scotland issued a new £5 note with her portrait in 2016.

Rachel Carson

“The sedge is wither’d from the lake, And no birds sing.” —John Keats, “La Belle Dame sans Merci”

Rachel Carson’s day job was in marine biology, and she wrote the prize-winning book The Sea Around Us (1951), which spent 86 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. But Carson is best known for her 1961 book, Silent Spring , which directly led to the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. With a title inspired by a Keats poem, Silent Spring originated when dead birds began turning up in the garden of one of Carson’s friends after rampant spraying of the pesticide DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane). A landmark in the environmental movement, Carson’s book demonstrated the harmful environmental effects of pesticides including DDT, leading to its ban. In the book, she asks, “Why should we tolerate a diet of weak poisons, a home of insipid surroundings, a circle of acquaintance who are not quite our enemies, the noise of motors with just enough relief to prevent insanity? Who would want to live in a world which is just not quite fatal?” In 2006, Discover named Silent Spring one of the 25 greatest science books of all time.

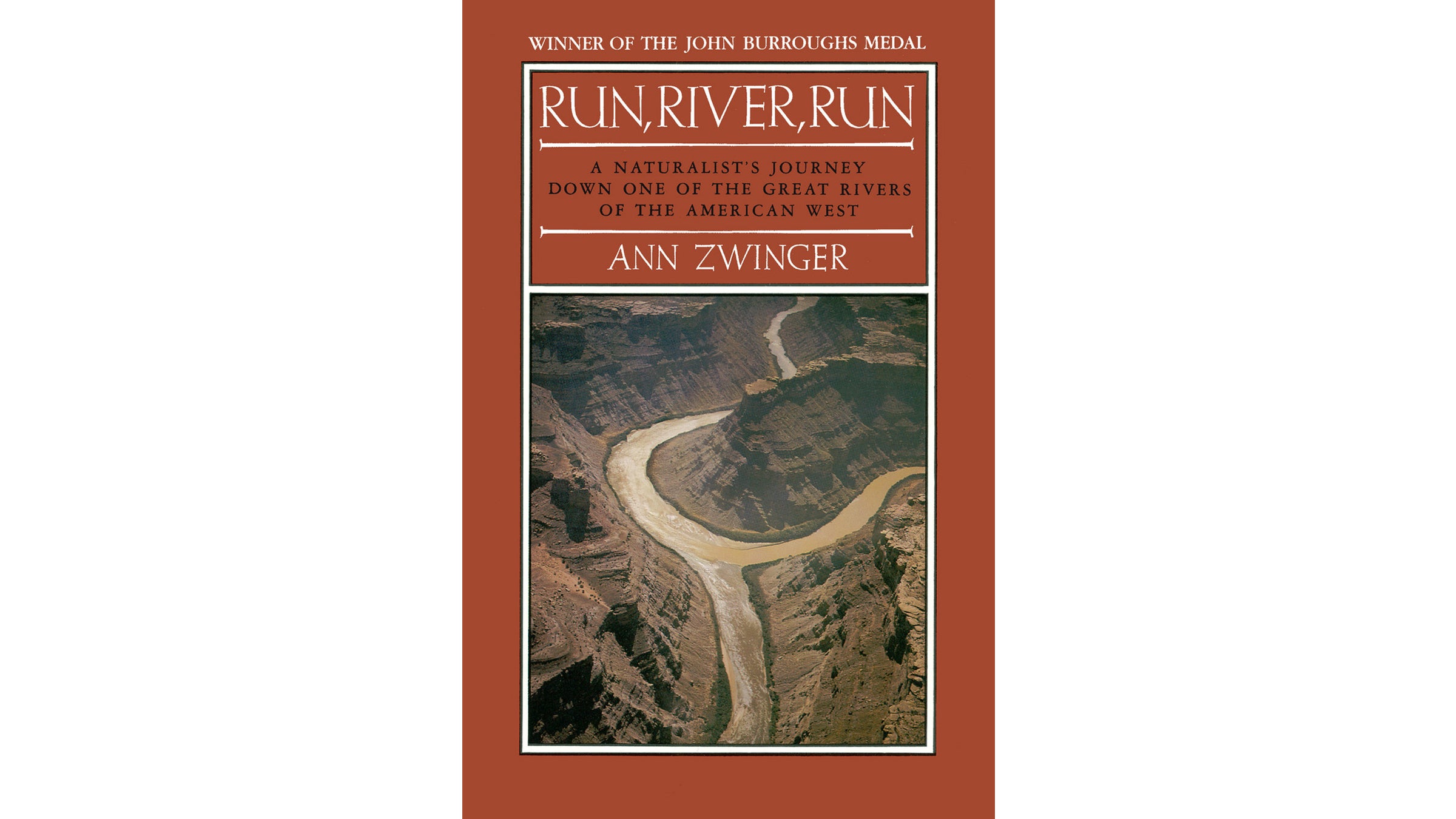

Ann Haymond Zwinger

Ann Haymond Zwinger was studying for a doctorate at Harvard when she met her husband, an Air Force pilot. As a military wife, she raised three daughters during their transfers around the country, finally settling down in Colorado Springs in 1960. When the couple bought 40 acres, Zwinger started cataloging and illustrating plants she discovered there—the beginning of a career writing natural histories of mountains, rivers, deserts, and canyon lands of the American West. Over 30 years, she wrote more than 20 books about her quiet observations of the wild. Meticulous and graceful, Zwinger’s writing integrated geology, botany, archaeology, and history along with personal reflections. Start by reading her 1975 book, Run, River, Run: A Naturalist’s Journey Down One of the Great Rivers of the West . You’ll feel as if you’re in the boat with her: “Raw, open sand dunes spread over the right bank, white prickly poppy and masses of yellow mustard and sand-verbena blooming across them.”

Annie Dillard

You feel as though you’re sleepwalking through life. You decide you need to get off the grid. As you head for the solitude of a cabin, bring Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard. It is, like Thoreau’s Walden , a “meteorological journal of [her] mind” (in her own words), a meditation, and a nonfiction book about seeing the world more intimately. At age 29, Dillard won a Pulitzer Prize for Pilgrim , and the book remains one of the finest in nature narratives. What sets Dillard apart is her desire to behold the sacred and divine along a creek in the Virginia woods. She observes her own way of seeing in poetic, scientific, mystical ways: “I had been my whole life a bell, and never knew it until at that moment I was lifted and struck.” Edward Abbey called Dillard the “true heir of the Master” (Thoreau), and she has been compared to Gerard Manly Hopkins, Virginia Woolf, John Donne, and William Blake.

Alison Hawthorne Deming

“What it takes to dazzle us, masters of dazzle, all of us here together at the top of the world, is a night without neon or mercury lamps.” —“Mt. Lemmon, Steward Observatory, 1990”

Descended from the great American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, Alison Hawthorne Deming is a rare interdisciplinary cross-thinker: a poet who writes about science. From the miniscule to the stellar, she explores science, the physical world, and poetry with exquisite observations and memorable juxtapositions. With seven volumes of poetry and five collections of essays, there is no one best place to begin exploring her work, though the essay “Science and Poetry: A View from the Divide” is a good one. As the title suggests, it coalesces Deming’s thinking about the creative process and shared language of the two disciplines. Also good: Writing the Sacred into the Real (2001), in which she writes passionately about the importance of nature writing in reconnecting people to the natural world and enhancing our spiritual lives, and her most recent work, Stairway to Heaven (2016), a collection of poems reflecting on the loss of her mother and brother.

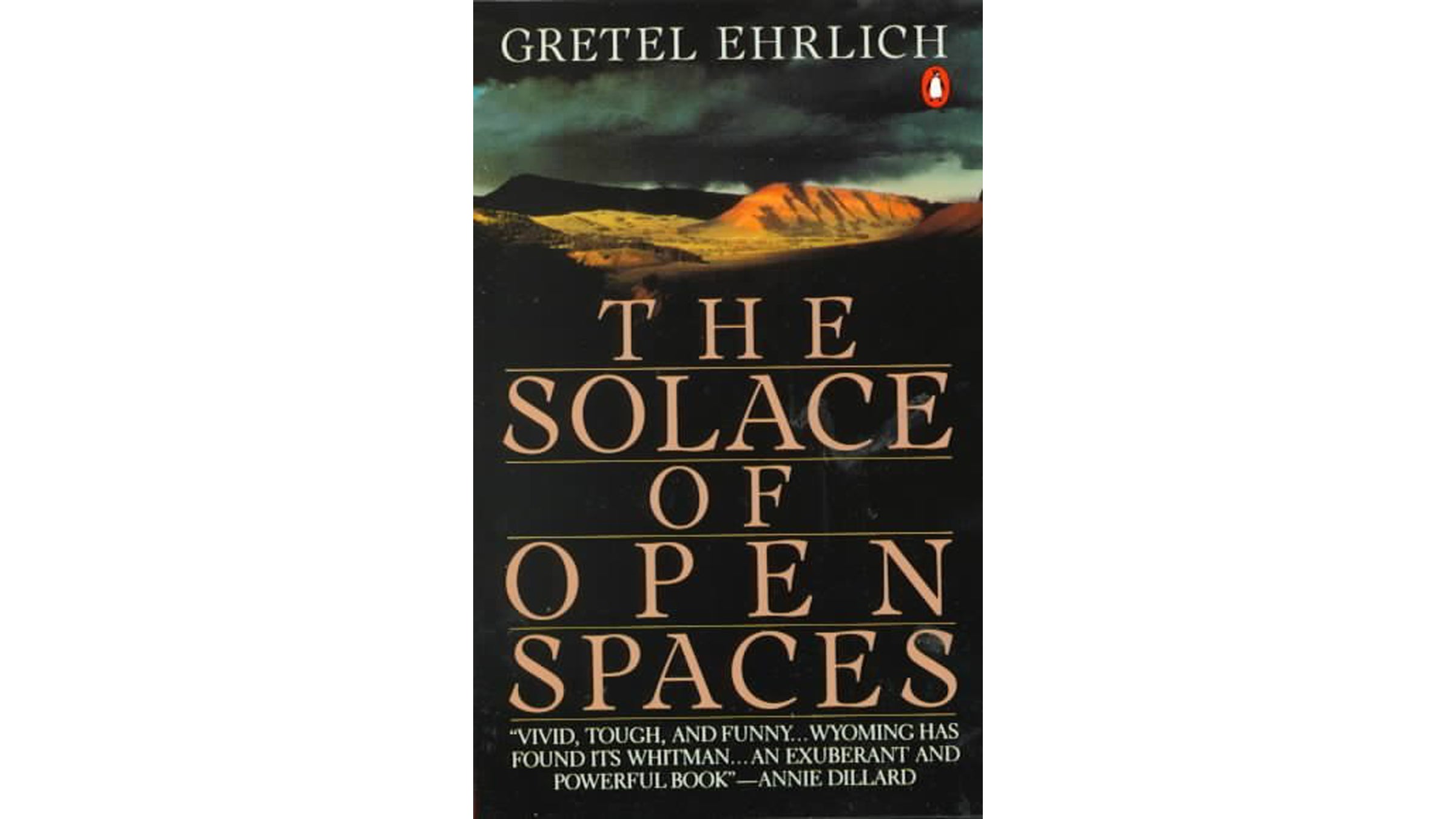

Gretel Ehrlich

Gretel Ehrlich debuted in 1985 with The Solace of Open Spaces . It is a bareback, elegant collection of essays—a mix of memoir, meditation, and poetry—set in Wyoming and capturing the stoic people who call the arid landscape home. After the death of the man she loves, Ehrlich throws herself into hard ranch work—delivering lambs and calves, punching cattle, learning to ride. You can practically smell pungent sagebrush and feel the texture of dirty sheep’s wool as she works to regain personal happiness. To herd sheep, Ehrlich observes, “is to discover a new human gear somewhere between second and reverse—a slow, steady trot of keenness with no speed.” She has a knack for describing the people and places of Wyoming with mystic expression: “The lessons of impermanence taught me this: loss constitutes an odd kind of fullness; despair empties into an unquenchable appetite for life.” Ehrlich’s 11 other books shimmer with a keen perspective on travel and place, including her 1991 narrative nonfiction, Islands, the Universe, Home —ten essays on ritual, nature and philosophy—and A Match to the Heart (1994), an unsentimental account of healing after being struck by lightning.

Kathleen Norris

“Nature, in Dakota, can indeed be an experience of the Holy.”

Don’t shut the book if you feel a prairie wind blow through you while reading Dakota: A Spiritual Geography by poet and essayist Kathleen Norris. It may happen. The book is a prairie-based spiritual meditation about learning to see more in less. In 1974, Norris and her husband moved from New York City to her grandparent’s farm in isolated Lemmon, South Dakota, where she discovers a community of Benedictine monks and revives her Protestant faith. “Maybe the desert wisdom of the Dakotas can teach us to love anyway, to love what is dying, in the face of death, and not pretend that things are other than they are.” Norris’s spiritual quest continued beyond this book when she became a Benedictine oblate in 1986 and wrote The Cloister Walk in 1997 and Amazing Grace: A Vocabulary of Faith in 1999.

Diane Ackerman

A grad school friend once argued, “Diane Ackerman is just too lush.” And I said, “That’s precisely why I’d like her.” If you’re in the mood for a velvety, layered wine by someone who revels in playing with language as much as writing about the physical world, reach for Ackerman’s books. One of the finest narrative nonfiction writers (you may know her bestselling book The Zookeeper’s Wife or Pulitzer finalist One Hundred Names for Love ), Ackerman also ponders diverse subjects in natural history. In The Natural History of the Senses , she encourages readers to see the common with fresh eyes: “Don’t think of night as the absence of day; think of it as a kind of freedom. Turned away from our sun, we see the dawning of far flung galaxies. We are no longer blinded to the star coated universe we inhabit.”

Leslie Marmon Silko

Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony is the story of a shell-shocked World War II veteran trying to regain his peace of mind. When first published in 1977, it deeply resonated with returning Vietnam vets and has gained more relevance as mental health and post-traumatic stress syndrome in vets is better understood. The story follows Tayo, a vet of mixed Laguna-white ancestry who has returned home to his reservation, having lost his will to live after enduring the 65-mile Bataan Death March and a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. Alternating between prose and poetry, the book tells the events of Tayo’s life and shows how ancient Laguna rituals reconnect him to his Pueblo people, plants, and animals. Silko is regarded as the premiere figure in the Native American Renaissance. A Laguna Pueblo, Mexican, and white storyteller, she infuses all her work—novels, poems, films, short stories, and essays—with concerns for traditional Native American culture and the restorative power of ancient rituals. Raised in the sparse beauty of a New Mexican plateau and a debut recipient of a MacArthur Genius Award in 1981, Silko deftly explores complex relationships between humans and nature.

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Robin Wall Kimmerer blends her scientific understanding as a professor of environmental and forest biology with her heritage as a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. Her first book, Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses , won the prestigious John Burroughs Medal for nature writing. Her second, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of Plants , won the Sigurd F. Olsen Nature Writing Award. In both books, Kimmerer weaves close observations of nature with indigenous views that invite us to reflect on our relationship with plants, animals, and the land—“an ancient conversation between mosses and rocks … About light and shadow and the drift of continents … an interface of immensity and minuteness, of past and present, softness and hardness, stillness and vibrancy.” Kimmerer manages to invoke ecological spirituality while never veering toward unsubstantiated facts (that’s the scientist in her).

Amy Stewart

Earthworms, wicked bugs, deadly plants. The flower industry. Botanical ingredients of the world’s great drinks. These are subjects of Amy Stewart’s bestselling books. For Stewart, a Texas transplant in California with a trademark wit, the story of the natural world is the grandest and most important human story. “Our quest to understand the natural world, to preserve it, and even to profit from it and make use of it, is in some ways the only story,” Stewart said in an email exchange. A personal favorite of mine is The Drunken Botanist: The Plants That Create the World’s Great Drinks , filled with liqueur recipes and horticultural history. We learn how to plant citrus and sloes, and how to make a sloe gin fizz or a red lion hybrid. It’s neither easy nor recommended, but I now plant my garden with a cocktail glass in one hand and a spade in the other.

Carolyn Finney

What percentage of visitors to America’s national parks are black? Seven percent, according to a survey commissioned by the National Park Service. If black people comprise twice that percentage of the U.S. population, why don’t more people of color venture into America’s public lands, and does that mean they aren’t engaged with the natural environment? These are potent questions of race, identity, and connection that Carolyn Finney, a writer, performer, and cultural geographer, addresses in her 2014 book, Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors . A mixture of scholarship, memoir, and history, the book is an academic yet probing read, braiding analysis with interviews to trace the environmental legacy of slavery, racial violence, and Jim Crow segregation while also celebrating contributions black Americans have made to the environment.

Terry Tempest Williams

“I am slowly, painfully discovering that my refuge is not found in my mother, my grandmother, of even the birds of Bear River. My refuge exists in my capacity to love. If I can learn to love death then I can begin to find refuge in change.”

By 1994, nine members of Terry Tempest Williams’s family had undergone mastectomies. Seven died of cancer. In Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place , her sixth book, Williams weaves memoir and natural history to tell the dual narrative of her mother’s cancer from atomic testing and the flooding of the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. Rooted in the sprawling landscape of her native Utah, the book pivots between the natural and unnatural, between a family devastated by exposure to 1950s atomic bomb testing and a bird refuge despoiled by developers. And she writes in such a shimmering manner that decades after reading Refuge for the first time, I can still see the egrets, owls, and herons on the Great Salt Lake. It’s also there that Williams once found a dead swan, placed its body in the shape of a crucifix with two black stones over the eyes, and wrote, “Using my own saliva as my mother and grandmother had done to wash my face, I washed the swan’s black bill and feet until they shone like patent leather.” Refuge has become a classic of American nature writing in its meditative search for meaning in the rhythms of life and death.

Janisse Ray

“My homeland is about as ugly as a place gets,” writes Janisse Ray at the beginning of her first book, Ecology of a Cracker Childhood (2000). That home was a junkyard in rural southern Georgia, where Ray writes about growing up in a poor, white, fundamentalist Christian family. It’s also a book about the longleaf pine ecosystem, 99 percent of which is gone. Ray mourns the apocalyptic deforestation of these pines, a valuable tree to merchants and the U.S. Navy. It grew from Virginia to Florida to Texas and has been replaced by faster-growing commercial pines. The author of six books, Ray focuses her work on rural life, agriculture, human rights, and environmental sustainability. What sets her apart as a nature writer? “Southerners in general have a deep relationship with land, history, and place,” Ray said. “Which makes nature very important to the Southern psyche. Because of the terrain, our emphasis is more botanic than geologic, more rural than urban, and more deeply rooted in story rather than statistic, generally speaking.”

Helen MacDonald

“Vast flocks of fieldfares netted the sky, turning it to something strangely like a sixteenth-century sleeve sewn with pearls.”

By page 50 of H Is for Hawk , savoring each sentence like pearls on a string, you realize you’re holding a new classic in nature writing. H is the third book for Helen MacDonald, a British poet, illustrator, falconer, and historian. Her first, Shaler’s Fish (2001), is a collection of poetry, and her second, Falcon (2006), is nonfiction—and it didn’t just put her on the map, but rocketed her to international acclaim. The book masterfully chronicles the collapse of reality when MacDonald’s father, who shared her passion for birding, unexpectedly dies on a London street. To deal with her grief, she throws herself into taming and training a goshawk, a bird she calls “a Victorian melodrama” and “as muscled as a pit bull, and intimidating as hell.” Taking seven years to write, H is, simply, a masterpiece. It also stands apart from much nature writing genre for its dark, sweary, and funny bits—traits practitioners of more traditional nature writing often shy away from, but shouldn’t. What can we expect next from MacDonald? She hasn’t decided yet. “Whatever it will be,” she told me, “I think it will build on one of the deepest themes in H Is for Hawk : investigating how we unconsciously use the natural world as a mirror of our own selves and concerns, and how this relates to the way we give value to particular landscapes and creatures.”

Camille T. Dungy

“I am never not thinking about nature,” Camille T. Dungy wrote in an email, “because I don’t understand a way we can be honest about who we are without understanding that we are nature.” A professor at Colorado State University, Dungy has written four poetry collections and edited Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry (2009). This widely influential anthology features nearly 200 poems, from 18th-century slave Phillis Wheatley to recent poet laureate Rita Dove. It challenges the notion that the tradition of nature writing has been solely grounded in the pastoral or wild landscapes of America and Europe. The voices within the collection show nature as a devastating legacy of slavery, with people forced to work the land; at the same time, portraits emerge of writers who saw nature as a source of hope, with seeds of survival. Dungy’s poetry is vivid, personal, and lucid and stays with you long after you close the book. The poem “Trophic Cascade” appears to be about a changing ecosystem after the introduction of wolves to Yellowstone, but the last lines deliver a curveball: “All this life born from one hungry animal, this whole, new landscape, the course of the river changed, I know this. I reintroduced myself to myself, this time a mother. After which, nothing was ever the same.” Her debut collection of personal essays, Guidebook to Relative Strangers: Journeys into Race, Motherhood, and History , was published in June.

Andrea Wulf

“All my books are about the relationship between humankind and nature,” said Andrea Wulf, a historian and writer living in Britain. “I dislike the categories that are imposed upon books, such as ‘biography,’ ‘history of science,’ ‘garden history,’ or ‘nature writing.’ I hope that we can transcend these artificial boundaries.” A prize-winning writer, Wulf is the author of five natural history books, including The Brother Gardeners (2008) and The Founding Gardeners: The Revolutionary Generation, Nature, and the Shaping of the American Nation (2012). It is her detailed and arresting 2015 book, The Invention of Nature: How Alexander von Humboldt Revolutionized Our World , that has garnered the most attention. Wulf pulls the explorer von Humboldt from oblivion and writes in great depth about why his ideas were so astonishing in the mid-19th century yet commonplace now: “It is almost as though his ideas have become so manifest that the man behind them has disappeared.”

Katharine Norbury

Following a miscarriage, a breast cancer diagnosis, and a letter from her birth mother, English writer and film editor Katharine Norbury set out on a journey: to follow rivers from sea to source in the Llyn Peninsula of Northwest Wales in the company of her nine-year-old daughter. This walking journey was meant to be a kind of family memory book that Norbury felt she might bind with leaves and shells, but it grew into an exquisite and profound reflection on the healing power of nature during times of grief and loss. The Fish Ladder: A Journey Upstream is Norbury’s life-affirming personal narrative about marriage, motherhood, adoption, and self-discovery. Part travelogue and healing meditation, Norbury’s place writing is lush, sensual, and vivid: “Each retreating wave was an apnoeic gasp, gravel lungs filled with water, drowning without panic.” Her next book—untitled as of yet—is about the circus and belonging.

Melissa Harrison

The British are obsessed with walking, weather, and the countryside. It’s not surprising that a very good book about moody mists, damp drizzles, and downright deluges would be widely embraced and showered with praise. That book is Rain: Four Walks in English Weather (2016) by English novelist and journalist Melissa Harrison. A patient and poetic guide, she invites readers to explore and reimagine one of the essential elements of our world, reminding us that to “experience the countryside on fair days and never foul is to understand only half its story.” Her third book, Rain , was nominated for the Wainwright Prize, an award given to the best writing on the outdoors, nature, and UK-based travel writing. Harrison has also written two nature novels: Clay (2013) and At Hawthorn Time (2015), the latter shortlisted for the Costa Novel Award. Hawthorn examines old secrets and a crumbling marriage against the unchanging backdrop of nature: “He remembered the graceful elms,” she writes. “So did the rooks, you could hear the loss of them in their chatter still. Things didn’t always turn out as you feared, though; the countryside was still full of saplings, but fugitive, sheltered in hedgerows and abetted by taller trees.”

Elena Passarello

A poet, professor, and actor, Elena Passarello is one of the finest essayists working today. Her second book, Animals Strike Curious Poses , is an exquisite collection of 16 essays weaving human and animal history together in narrative nonfiction that is playful, poignant, and deeply researched. Readers of this book as well as her first, Let Me Clear My Throat (2013), will not be surprised to learn that Passarello is a recipient of the Whiting Award for Nonfiction, a literary prize given to emerging writers with great promise. In Animals Strike Curious Poses , she takes us on a journey to a breathtaking range of places: the imagined mindset of an “endling” (the last of a species), the seemingly lost “crucial glance” between humans and wild animals, and her own childhood memories of “Lancelot the Living Unicorn.” In typical good humor, Passarello told me she brings to the practice of nature writing “a layperson’s sense of uncertainty, wonder, and often wrongheadedness.” What fascinates her is the nature of human thought and obsession, be it a song, a speech, or a salamander. “That’s why I’m as likely to write about the social practices of birdwatchers as I am the birds they seek.” What’s she writing now? Passarello said her next venture will take her outside “to do something a little crazy, something for which I have to undergo training.” Watch for it.

Amy Liptrot

After years of hedonism and drowning in booze in London, Amy Liptrot washes ashore on her native Orkney Islands in Scotland to try to save herself. Her debut book, The Outrun —winner of the 2016 Wainwright Prize for best nature, travel, and outdoor writing—is raw and beautiful, a painful rehab memoir. It follows Liptrot’s recovery and reconnection with the landscape she sought to escape for years. In atmospheric writing, she describes swimming in the cold sea, tracking puffins and arctic terns, and observing the night sky: “I’ve swapped disco lights for celestial lights but I’m still surrounded by dancers. I am orbited by 67 moons.” The best descriptive writers have close, repeated observations of particular place; Liptrot watches tides, winds, clouds, wildlife, and more. Learning folklore and rural traditions of the islands also enhances her new, celebratory sense of place.

When you buy something using the retail links in our stories, we may earn a small commission. We do not accept money for editorial gear reviews. Read more about our policy.

Popular on Outside Online

Enjoy coverage of racing, history, food, culture, travel, and tech with access to unlimited digital content from Outside Network's iconic brands.

Healthy Living

- Clean Eating

- Vegetarian Times

- Yoga Journal

- Fly Fishing Film Tour

- National Park Trips

- Warren Miller

- Fastest Known Time

- Trail Runner

- Women's Running

- Bicycle Retailer & Industry News

- FinisherPix

- Outside Events Cycling Series

- Outside Shop

© 2024 Outside Interactive, Inc

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book News & Features

The workings of nature: naturalist writing and making sense of the world.

Genevieve Valentine

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

"In every generation and among every nation, there are a few individuals with the desire to study the workings of nature; if they did not exist, those nations would perish."

-- Al-Jahiz, The Book of Animals

In 185 AD, Chinese astronomers recorded a supernova. Among more detached details of its appearance, there is this: "It was like a large bamboo mat. It displayed the five colors, both pleasing and otherwise."

The attempt to ground the unknown within the familiar — and the editorial aside of "otherwise" — cuts to the heart of naturalist writing. Nearly 2000 years later, Carl Sagan did the same in Cosmos , condensing astronomy to its component parts: facts and wonder.

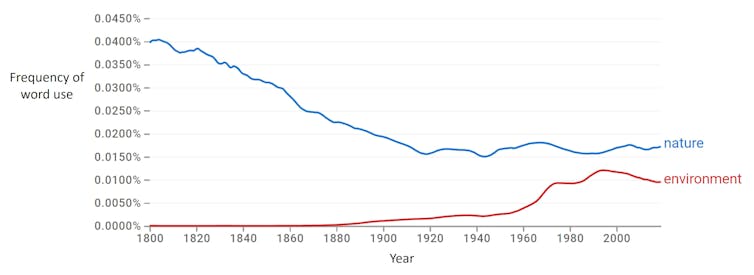

We've been curious about the natural world since before recorded time; the history of naturalism is human history. By the ninth century, al-Jahiz's multi-volume History of Animals combined zoological folklore with scientific observation, including theories of natural selection. In the early 20th century, Sioux author Zitkala-Ša wrote landscapes intertwined with the personal, which became a model for the form. In 1962, Rachel Carson's ecological manifesto Silent Spring was a deciding factor in banning DDT.

The best naturalist writing delivers both a secondhand thrill of obsession and a jolt of protectiveness for what's been discovered. Some of it reveals as much about the author as the surroundings. (Carl Linnaeus' 1811 Tour of Lapland manuscript cuts off a paragraph about wedding customs mid-sentence, picking up again with a breathless catalog of marsh plants.) And naturalists themselves are shaped by the lure of landscapes on the page. Robert MacFarlane's Landmarks explores the British countryside using others' writing as an interior map that challenges him to approach familiar places in new ways.

We love reading about nature for the same reason naturalists love being ankle-deep in marshes: Nature provides enough order to soothe and enough entropy to surprise. It's also why so many involve a person in the landscape; understanding our place in the world is as important as understanding the world itself. We read the work of naturalists to capture that sense of discovery made familiar. They present worlds we've never seen, and make us care as if they were our own backyards.

Not every naturalist sets out to be an activist; this is a literary tradition as much as a scientific one. But there are threads that connect naturalist literature, across continents and centuries. It's driven by an environmental curiosity that integrates the scientific and the spiritual; facts inspire wonder, rather than quench it. And every piece of naturalist literature, from al-Jahiz to today, makes a case for preserving the world it sees.

The Invention of Nature

Some naturalists actually do try to encompass the world entire. In The Invention of Nature , Andrea Wulf follows Alexander Humboldt's expeditions in Latin America and European royal courts, painting a portrait of a man whose hunger for knowledge — and constant pontificating about it — bordered on caricature. Humboldt's legacy is the 'web of life' his work conveyed to a lay audience. That interconnectedness made him an early conservationist; by 1800 he was noting adverse effects "when forests are destroyed, as they are everywhere in America by European planters, with an imprudent precipitation."

But he wasn't the first to catalog the systems of life. A century before Humboldt, German-born naturalist Maria Sybilla Merian was in Surinam, recording her life's passion: butterflies, moths, and insects. Chrysalis , Kim Todd's biography of this amateur scientist who established the idea of a life cycle, aims for a sly impression of Merian, down to the subject matter: "Insects," Todd explains, "generally gave off a whiff of vice." Merian's engravings made life cycles palpable for a public who still believed rotten meat spontaneously transformed into flies; it was impressive enough to change assumptions about the natural world (though Merian's credit waned as male scientists began absorbing her work into their own).

Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. This is the dynamic at the heart of Annie Dillard's Pilgrim at Tinker Creek , which carries a touch of the hymnal (and a grim streak that has a grandmother in Merian's engraving of a tarantula devouring a bird), and Barbara Hurd's Stirring the Mud , a love letter swamps, bogs, and "the damp edges of what is most commonly praised." And few naturalists write themselves into their landscapes quite so drily as M. Krishnan. The essays in Of Birds and Birdsong carry a sense of magical realism; always scientifically rigorous (his bird descriptions are those of a man looking for a particular friend in a crowd of thousands), Krishnan writes himself as a resigned meddler in avian affairs; he could try to be invisible among nature's bounty, but then who'd train his pigeons?

Of course, some writers have to fight to be seen on the landscape at all. Enter The Colors of Nature , an anthology of nature writing by people of color edited by Alison H. Deming and Lauret E. Savoy, providing deeply personal connections to — or disconnects from — nature. Jamaica Kincaid's "In History" considers naturalism in the aftermath of colonialism, asking a crucial question for naturalism in a global context: "What should history mean to someone who looks like me?" And Joseph Bruchac's travel diary is pragmatism shot through with hope; "Our old words keep returning to the land."

The Colors of Nature

For others, the internal landscape and that hope for the natural world must be rediscovered in tandem. In Braiding Sweetgrass , botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer tackles everything from sustainable agriculture to pond scum as a reflection of her Potawatomi heritage, which carries a stewardship "which could not be taken by history: the knowing that we belonged to the land." That sense of connection, or the loss of it, is the spine of the book: mucking out a pond is a microcosm, agriculture becomes rumination on symbiosis, and mast fruiting of pecan trees parallels human and plant communities.

It's a book absorbed with the unfolding of the world to observant eyes — that sense of discovery that draws us in. Happily for armchair naturalists, mysteries of the natural world never stop unfolding; but increasingly, a sense of impending doom accompanies the delight of knowledge. Kimmerer mentions a language between trees as something awaiting more specific study; it arrives later this year in Peter Wohlleben's The Hidden Life of Trees . A no-nonsense writing style — he came, he studied, here's how to date a forest via its weevil population — frames a deeply conservationist argument: Trees harbor not only ecosystems, but feelings, vocabulary, and etiquette. Hidden Life is designed to be an arboreal Silent Spring .

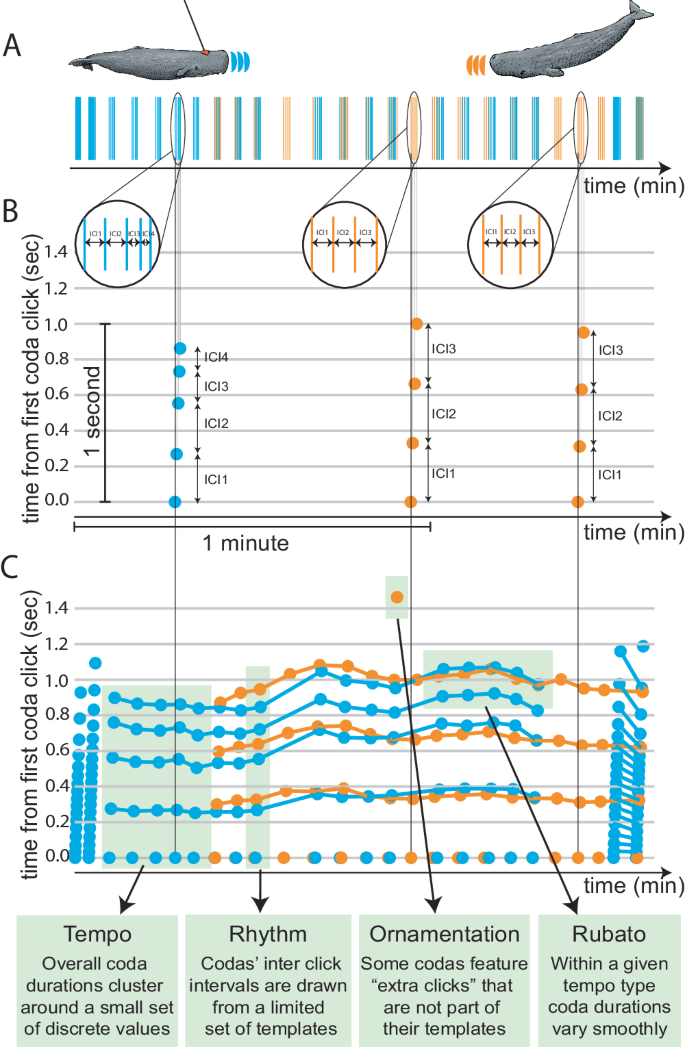

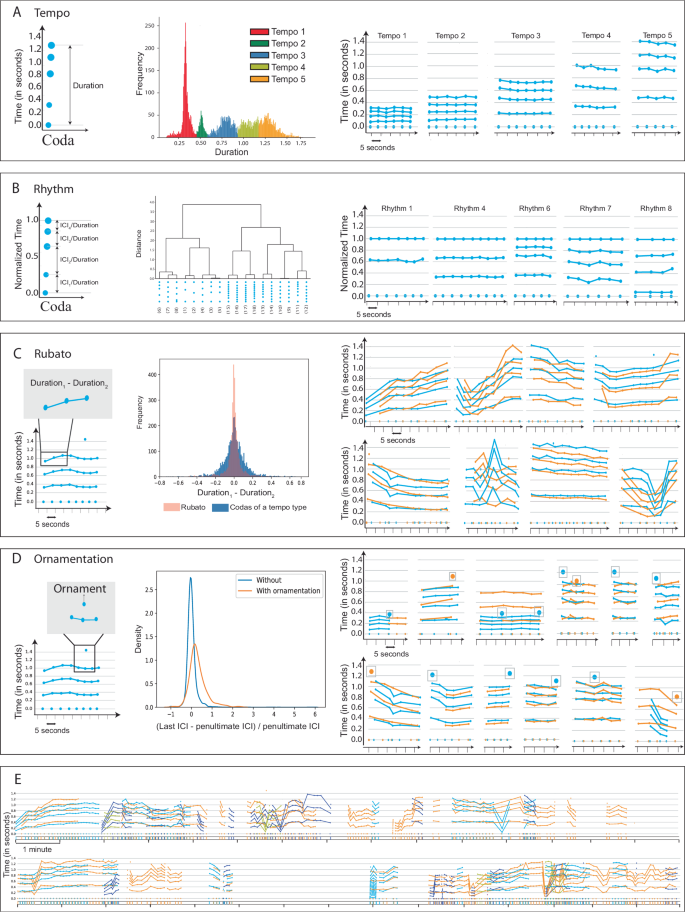

For some places, however, no revelations are yet possible; the world being studied is simply too mysterious to be yet wholly understood. With meditative prose, 1986's Arctic Dreams chronicled Barry Lopez's expeditions in an ecosystem so punishing half an animal population can die every winter, and so otherworldly animal fat is preserved on bones after a century. "Something eerie ties us to the world of animals," he says, and it's both a warning and a promise. In The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Deep, Philip Hoare's marine obsession is similarly dreamlike; for him, what we know about whales and how they make us feel is deeply linked. After all, our 'discovery' of them is still in its first blush. Sperm whales were first filmed in 1984; "We knew what the world looked like before we knew what the whale looked like." The only absolute conclusion in his book is a stern one: Humanity's damaging effects on nature and its fascination with the unknown has been devastating; if we're going to keep whales long enough to know them, that fascination will have to take a more protective turn.

To write about the world around us is to write about people, whether cataloging the unknown or coming to terms with one's backyard. These narratives are crucial, especially now — stories of the worth of nature, even just as a mirror of ourselves, build a narrative in which nature's something worth saving. It's imperfect; making nature an object rather than a subject prevents us from seeing ourselves as part of natural patterns of cause and effect. But in The Colors of Nature, Aileen Suzara pins it down: "The landscape is a narrative, not a narrator, because it has no human voice." The human voice that looked at the dark and saw a dying star is heard 2000 years later. If we're going to have another 2000 years, there's no time like the present to start listening.

Genevieve Valentine's latest novel is Icon.

- Upcoming Events

- Get Tickets

- Tickets & Hours

- Parking & Directions

- Accessibility

- AWM Exclusives

- Watch Past Events

- American Writers Festival

- Venue Rentals

- Adult Group Experiences

- Corporate Experiences

- Field Trips (K-12)

- In-Person Permanent Exhibits

- In-Person Temporary Exhibits

- Online Exhibits

- Book Club Reading Recommendations

- AWM Author Talks

- Nation of Writers

- Dead Writer Drama

- Affiliate Museums

- In-Person Field Trips

- Virtual Field Trips

- Resources by Grade Level

- Resources by Exhibit

- Inquiry-Based Curriculum

- Using Primary Sources

- Educational Updates

- Current Competition

- Past Winners

- My America Curriculum

- Dark Testament Curriculum

- Donor Societies

- Apply to Volunteer

- OnWord Annual Benefit

- Planned Giving

- Sponsorship

- History & Mission

- Diversity & Equity

- National Advisory Council

- Curating Team

- Board of Trustees

- Jobs & Volunteering

Blog , Book Club Reading Recommendations , Other Recommendations , Recommendations

Six environmental authors who should be on your reading list.

As the days lengthen and the sun shines higher in the afternoon sky, birds begin to chatter and whistle returning to their northern homes. The Harbinger of Spring has graced our yards and greenspaces. There is no better time than now, especially because we are remaining indoors for the good of our communities, to delve into a book on the topic of the environment. Now that most of the hustle and bustle of the cities have dwindled to the occasional grocery store attendee and some people lounging in the park, there have been many many more occurrences of wild animals returning to the urban landscape, and natural spaces in urban settings becoming cleaner and more habitable to our fellow earth dwellers.

The resilience of nature shines through in these uncertain times. With these six authors one can find stories of strength, wonder, and excitement all pointing towards environmental themes and ways the human race can help or harm our planet and ourselves in the process.

This list is also available on Bookshop.org , which benefits independent bookstores. We also strongly encourage you to support your local bookstore by ordering through them online directly. They need our help more than ever, and we need them to stick around.

By Elizabeth Brownfield

Barbara Kingsolver

Barbara Kingsolver’s novels often focus on both the impacts of global climate change on everyday rural citizens and intricate and strained familial bonds. The central themes of her novels tend to be about changes in the local environment and characters surrounded by political and social issues, many of which are environmental. The Poisonwood Bible , a book about a missionary family moving from the U.S. state of Georgia to the Congo during the fight for Congolese independence in the 1950s, is by far her most famous novel, however her more recent novels, Flight Behavior and Unsheltered reflect the uncertain times ahead and individuals uncovering adversity and abuse within the very environment in which they are rooted.

In her writing Kingsolver enjoys exploring the many different landscapes of places she has lived including rural Appalachia, the Congo, and Arizona. Her relatable characters are often discovering the climate injustices within their own backyards, or struggling to understand the new environment in which they have arrived. She has also written several non-fiction and short story accounts of her time living exclusively off local food sources and thinking about the ecological relationships between humans and nature.

Suggested reading: Flight Behavior

Mary Hunter Austin

If you’ve read Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire then you should read The Land of Little Rain by Mary Hunter Austin next. Austin was one of the few women nature writers of the 19th century. Obsessed with everything about the desert, she observes the mysticism, allure, and deadly nature of the Mojave Desert. Utilizing illustrative, enchanting, and haunting imagery from her time in the desert, Austin weaves tales of the harsh, unlivable environment with the flora and fauna that have chosen and adapted to endure these unrelenting conditions.

If you need more reason to read her, in addition to advocating for human connection with nature and the rights of the people who live there, namely Native American Tribes, she was a proponent for women’s and immigrants rights. She produced every type of writing: plays, children’s books, essays, non-fiction. She wrote on water management, the mistreatment of Native Americans and the injustices and social restrictions of womanhood. Her life was full of hardships and she was unconventional in every way. She lived all over the world, argued often with John Muir, and kept company with Herbert Hoover, H.G. Wells, and Jack London. People she has influenced range from Willa Cather to prominent landscape photographer Ansel Adams to contemporary environmental writers such as Gary Synder.

Suggested reading: The Land of Little Rain

Michael Pollan

In preparation for spring and summer and arguably all the best foods to come back in season, I would recommend reading Micheal Pollan’s books. Throughout his many books, Pollan has explored topics such as the domestication of our food, the ways food can affect our thinking, and how the modern American supermarket has evolved to include corn in almost everything. He has investigated how weeds are linked to the very spaces that humans occupy. In elegant, well-thought prose, Pollan successfully conveys how to think more critically about the important food choices we make everyday and the ways that nature, by product of food and consumption, is a part of our everyday lives.

Suggested reading: The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals

Harriet A. Washington

In her previous books, Washington focuses on work in the medical field, often about analyzing the mistreatment of African-Americans from the colonial period to today, secrets of the medical trade and destigmatizing mental health. However, in her most recent book Washington concentrates on how chemicals and pollutants are disproportionately affecting communities of color in America as a result of environmental racism. Washington writes primarily about the ways that chemicals can affect children and adults even if they are exposed to less than the determined threshold. Unlike the other authors on this list, she directs attention more on the detrimental effects of humans on themselves and the earth.

Suggested reading: A Terrible Thing to Waste: Environmental Racism and Its Assault on the American Mind

Wendell Berry

If you’ve already read Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac , next on your list should be some of Wendell Berry’s books. Although the environment is that of the farms between the rolling hills of Kentucky and the sloping banks of the Kentucky River Valley, Berry, much like Leopold, concentrates on the American cultural norms surrounding agriculture, farming and nature and his criticisms remain noteworthy to this day.

Berry is an author, poet, essayist, environmental activist, farmer, and cultural critic. With insights into the back-to-the-land movement in the 1970’s, thoughts on sustainable farming and agriculture and illustrating a way of life that’s realistic for the future of agriculture within his writings, Berry emphasizes a connection to the land, sustainable agriculture and roots within your local environment. Descended from generations of farmers, he strongly advocates for anti-modernism, localization, and the education of farmers, bringing up points that the average city dweller today, inundated with sleek new technology and car commercials that romanticize rural landscapes, could never fully understand.

Suggested reading: The Unsettling of America: Culture & Agriculture

Carl Hiaasen

Known for his best selling Young Adult novels such as Hoot and Flush and themes of crime, mystery, environmentalism, and crooked politicians, Carl Hiassen has a book for everyone from youth to adult. Full of action and adventure, Hiaasen has some of the best books for learning about environmental justice and local knowledge of land. Oftentimes his books are set in his native Florida and utilizes endangered or localized species to inform the plot. Hoot is a personal favorite. Set in Florida three unlikely middle schoolers band together to stop the construction of a Pancake House franchise in the middle of the endangered Burrowing Owls habitat.

Suggested reading: Hoot

Who are your favorite environmentally conscious writers? Let us know in the comments!

Visit our Reading Recommendations page for more book lists.

2 thoughts on “ Six Environmental Authors Who Should Be On Your Reading List ”

Beautiful visions, but a world of 8 billion needs more than words… incentives to grow from apex predators to cosmic gardeners. Humanity isn’t prepared for the Milky Way, manage environment on Earth sustainably. Ideology not enough: takes economic drivers: Green Household Behaviour tax offset and compulsory measurement of ecological footprint to cost Earth repair into products

Thank you very much. This is so of much help. More power!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Search for:

Username or email address *

Password *

Remember me Log in

Lost your password?

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Nature » Nature Writing

Browse book recommendations:

Nature Writing

- Plants, Trees & Flowers

- Rocks & Minerals

- The Prehistoric World

- The Solar System & Space

Last updated: May 06, 2024

Nature writing, celebrating and meditating on the non-human environment and our relationship with it, has a long literary pedigree, stretching back to the 18 th century. Beginning there, Lucy Newlyn discusses William and Dorothy Wordsworth , how brother and sister influenced each other’s writing and their commitment to writing about the every day and the sights and sounds of their environment. Laura Dassow Walls looks at Henry David Thoreau , an early advocate of simple living and ecology. T C Boyle chooses his best books on man and nature , and talks about why the Dodo didn’t have a chance and whether it really matters if lions, tigers and polar bears become extinct (it does).

Our nature interviews cover diverse parts of the world. Sarah Wheeler talks about the polar regions , and Michael Jacobs talks about the Andes . Paul Brassley discusses the English countryside and Hari Kunzru chooses his best books on the American desert .

Robert Macfarlane talks about wild places and Sara Maitland discusses silence . Jeremy Mynott looks at birdwatching and David George Haskell chooses his best books on trees .

More generally, Amy Liptrot chooses her best books on nature writing , Charles Foster his best nature books of 2017 , 2018 and 2019 , while M G Leonard chooses her the best nature books for kids .

The best books on Local Adventures , recommended by Alastair Humphreys

The forest unseen: a year's watch in nature by david george haskell, the path: a one-mile walk through the universe by chet raymo, on looking: eleven walks with expert eyes by alexandra horowitz, pilgrim at tinker creek by annie dillard, the backyard adventurer by beau miles.

Wonderful as it would be to climb Mount Everest or row across the Atlantic, not all of us will get the chance to go on an epic adventure. But that doesn't mean we can't go exploring. Alastair Humphreys , the British adventurer, explains the concept of 'local adventure' and recommends books that give a feel for what it's about and why it's worth pursuing.

Wonderful as it would be to climb Mount Everest or row across the Atlantic, not all of us will get the chance to go on an epic adventure. But that doesn’t mean we can’t go exploring. Alastair Humphreys, the British adventurer, explains the concept of ‘local adventure’ and recommends books that give a feel for what it’s about and why it’s worth pursuing.

The best books on The Scottish Highlands , recommended by Annie Worsley

The living mountain by nan shepherd, the poems of norman maccaig ed. ewen maccaig, sea room by adam nicolson, song of the rolling earth: a highland odyssey by john lister-kaye, at the loch of the green corrie by andrew greig.

The Scottish Highlands are known for the stark splendour of the landscape and the bellowing of the stags. They have inspired many classic works of poetry and nature writing, says Annie Worsley —the author of a memoir set on Scotland's rugged north west coast. Here, she recommends five books on the Scottish Highlands that portray the people and their place.

The Scottish Highlands are known for the stark splendour of the landscape and the bellowing of the stags. They have inspired many classic works of poetry and nature writing, says Annie Worsley—the author of a memoir set on Scotland’s rugged north west coast. Here, she recommends five books on the Scottish Highlands that portray the people and their place.

The Best Nature Memoirs , recommended by Victoria Bennett

Belonging: natural histories of place, identity and home by amanda thomson, among flowers: a walk in the himalayas by jamaica kincaid, thin places by kerri ní dochartaigh, trace: memory, history, race, and the american landscape by lauret savoy, upstream: selected essays by mary oliver.

Nature is intrinsic to our experience of being alive and reading about it allows us to connect not just with the natural world but with ourselves. Here Victoria Bennett , author of All My Wild Mothers, a memoir of grief and creating an apothecary garden, recommends five other nature memoirs, highlighting personal and reflective prose by writers including Lauret Savoy, Mary Oliver, and Jamaica Kincaid.

Nature is intrinsic to our experience of being alive and reading about it allows us to connect not just with the natural world but with ourselves. Here Victoria Bennett, author of All My Wild Mothers, a memoir of grief and creating an apothecary garden, recommends five other nature memoirs, highlighting personal and reflective prose by writers including Lauret Savoy, Mary Oliver, and Jamaica Kincaid.

Amy Liptrot chooses the best of Nature Writing

Ring of bright water by gavin maxwell, the drowned world by j. g. ballard, findings by kathleen jamie, feral: rewilding the land, the sea, and human life by george monbiot, the orkney book of birds by tim dean and tracy hall.

Amy Liptrot , whose bestselling memoir The Outrun won the 2016 Wainwright Prize for nature writing, talks to Five Books about her favourite writing about landscape—and how her immersion in island life helped her recover from alcoholism.

Amy Liptrot, whose bestselling memoir The Outrun won the 2016 Wainwright Prize for nature writing, talks to Five Books about her favourite writing about landscape—and how her immersion in island life helped her recover from alcoholism.

The best books on Sense of Place , recommended by Patrick Galbraith

South and west: from a notebook by joan didion, the crofter and the laird by john mcphee, the dark months of may by tom pickard, salmon: a fish, the earth, and the history of their common fate by mark kurlansky, jock of the bushveld by percy fitzpatrick.

Novelists, non-fiction writers and poets all attempt to create immersive and atmospheric settings in their books—what is called a 'sense of place' in literary terms. Here, the British journalist Patrick Galbraith selects five books that explore and evoke a sense of place—including works by Joan Didion, Mark Kurlansky and John McPhee.

Novelists, non-fiction writers and poets all attempt to create immersive and atmospheric settings in their books—what is called a ‘sense of place’ in literary terms. Here, the British journalist Patrick Galbraith selects five books that explore and evoke a sense of place—including works by Joan Didion, Mark Kurlansky and John McPhee.

The best books on Natural History , recommended by David George Haskell

The outermost house: a year of life on the great beach of cape cod by henry beston, dark emu: aboriginal australians and the birth of agriculture by bruce pascoe, a natural history of the future: what the laws of biology tell us about the destiny of the human species by rob dunn.

Natural history can offer a "portal into wonder and astonishment," says David George Haskell , the biologist and award-winning author of nonfiction works including Sounds Wild and Broken and The Forest Unseen . But natural history books, in the past, have also been guilty of reinforcing prejudices. Here he recommends five natural history books that celebrate the diversity of life.

Natural history can offer a “portal into wonder and astonishment,” says David George Haskell, the biologist and award-winning author of nonfiction works including Sounds Wild and Broken and The Forest Unseen . But natural history books, in the past, have also been guilty of reinforcing prejudices. Here he recommends five natural history books that celebrate the diversity of life.

The Best Books of Ocean Journalism , recommended by Laura Trethewey

The brilliant abyss: exploring the majestic hidden life of the deep ocean, and the looming threat that imperils it by helen scales, the outlaw ocean: journeys across the last untamed frontier by ian urbina, mapping the deep by robert kunzig, deep: freediving, renegade science, and what the ocean tells us about ourselves by james nestor, the wave: in pursuit of the rogues, freaks, and giants of the ocean by susan casey.

Humans have mapped only 25 percent of the seafloor, so the ocean is ripe for exploration and investigation. Environmental journalist and author Laura Trethewey recommends five books by 'ocean journalists' that explore the life, crime and science of the seas.

Humans have mapped only 25 percent of the seafloor, so the ocean is ripe for exploration and investigation. Environmental journalist and author Laura Trethewey recommends five books by ‘ocean journalists’ that explore the life, crime and science of the seas.

The best books on Islands , recommended by Gavin Francis

'the voyage of st brendan,' in the age of bede edited by j.f. webb and d.h. farmer, selkirk's island: the true and strange adventures of the real robinson crusoe by diana souhami, a woman in the polar night by christiane ritter, atlas of remote islands: fifty islands i have never set foot on and never will by judith schalansky.

Generations of writers, explorers and armchair travellers have found a focal point of fascination in the idea of the remote island. Why so? Gavin Francis , the award-winning writer, explains the everlasting appeal of the lonely isle – and why the fantasy is at least as powerful as the salt-sprayed reality – as he selects five of the best books on islands.

Generations of writers, explorers and armchair travellers have found a focal point of fascination in the idea of the remote island. Why so? Gavin Francis, the award-winning writer, explains the everlasting appeal of the lonely isle – and why the fantasy is at least as powerful as the salt-sprayed reality – as he selects five of the best books on islands.

The Best Books For Environmental Learning , recommended by Mitchell Thomashow

Braiding sweetgrass: indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants by robin wall kimmerer, earth's wild music: celebrating and defending the songs of the natural world by kathleen dean moore, the next great migration: the beauty and terror of life on the move by sonia shah, landmarks by robert macfarlane.

We are surrounded by nature but it's easy to miss it and spend time either in our heads or on screens. Here Mitchell Thomashow , a longtime teacher of environmental learning, picks books to broaden our vistas and help us see the natural world with fresh eyes.

We are surrounded by nature but it’s easy to miss it and spend time either in our heads or on screens. Here Mitchell Thomashow, a longtime teacher of environmental learning, picks books to broaden our vistas and help us see the natural world with fresh eyes.

The best books on Summer , recommended by Melissa Harrison

The summer book by tove jansson, the go-between by l p hartley, to the river: a journey beneath the surface by olivia laing, summer by ali smith, the hill of summer by j a baker.

Temperatures ratcheting, tinderbox conditions, a pressure cooker atmosphere... summer is a handy literary shorthand for rising tensions. But in the natural world, summer is a quiet time when the flowers die back and the fruits and seeds are ripening. Here, Melissa Harrison —the novelist, nature writer and podcaster—recommends five of the best summer books, for those who like to read in step with the seasons.

Temperatures ratcheting, tinderbox conditions, a pressure cooker atmosphere… summer is a handy literary shorthand for rising tensions. But in the natural world, summer is a quiet time when the flowers die back and the fruits and seeds are ripening. Here, Melissa Harrison—the novelist, nature writer and podcaster—recommends five of the best summer books, for those who like to read in step with the seasons.

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

What is Nature Writing?

Definition and Examples

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Nature writing is a form of creative nonfiction in which the natural environment (or a narrator 's encounter with the natural environment) serves as the dominant subject.

"In critical practice," says Michael P. Branch, "the term 'nature writing' has usually been reserved for a brand of nature representation that is deemed literary, written in the speculative personal voice , and presented in the form of the nonfiction essay . Such nature writing is frequently pastoral or romantic in its philosophical assumptions, tends to be modern or even ecological in its sensibility, and is often in service to an explicit or implicit preservationist agenda" ("Before Nature Writing," in Beyond Nature Writing: Expanding the Boundaries of Ecocriticism , ed. by K. Armbruster and K.R. Wallace, 2001).

Examples of Nature Writing:

- At the Turn of the Year, by William Sharp

- The Battle of the Ants, by Henry David Thoreau

- Hours of Spring, by Richard Jefferies

- The House-Martin, by Gilbert White

- In Mammoth Cave, by John Burroughs

- An Island Garden, by Celia Thaxter

- January in the Sussex Woods, by Richard Jefferies

- The Land of Little Rain, by Mary Austin

- Migration, by Barry Lopez

- The Passenger Pigeon, by John James Audubon

- Rural Hours, by Susan Fenimore Cooper

- Where I Lived, and What I Lived For, by Henry David Thoreau

Observations:

- "Gilbert White established the pastoral dimension of nature writing in the late 18th century and remains the patron saint of English nature writing. Henry David Thoreau was an equally crucial figure in mid-19th century America . . .. "The second half of the 19th century saw the origins of what we today call the environmental movement. Two of its most influential American voices were John Muir and John Burroughs , literary sons of Thoreau, though hardly twins. . . . "In the early 20th century the activist voice and prophetic anger of nature writers who saw, in Muir's words, that 'the money changers were in the temple' continued to grow. Building upon the principles of scientific ecology that were being developed in the 1930s and 1940s, Rachel Carson and Aldo Leopold sought to create a literature in which appreciation of nature's wholeness would lead to ethical principles and social programs. "Today, nature writing in America flourishes as never before. Nonfiction may well be the most vital form of current American literature, and a notable proportion of the best writers of nonfiction practice nature writing." (J. Elder and R. Finch, Introduction, The Norton Book of Nature Writing . Norton, 2002)

"Human Writing . . . in Nature"

- "By cordoning nature off as something separate from ourselves and by writing about it that way, we kill both the genre and a part of ourselves. The best writing in this genre is not really 'nature writing' anyway but human writing that just happens to take place in nature. And the reason we are still talking about [Thoreau's] Walden 150 years later is as much for the personal story as the pastoral one: a single human being, wrestling mightily with himself, trying to figure out how best to live during his brief time on earth, and, not least of all, a human being who has the nerve, talent, and raw ambition to put that wrestling match on display on the printed page. The human spilling over into the wild, the wild informing the human; the two always intermingling. There's something to celebrate." (David Gessner, "Sick of Nature." The Boston Globe , Aug. 1, 2004)

Confessions of a Nature Writer

- "I do not believe that the solution to the world's ills is a return to some previous age of mankind. But I do doubt that any solution is possible unless we think of ourselves in the context of living nature "Perhaps that suggests an answer to the question what a 'nature writer' is. He is not a sentimentalist who says that 'nature never did betray the heart that loved her.' Neither is he simply a scientist classifying animals or reporting on the behavior of birds just because certain facts can be ascertained. He is a writer whose subject is the natural context of human life, a man who tries to communicate his observations and his thoughts in the presence of nature as part of his attempt to make himself more aware of that context. 'Nature writing' is nothing really new. It has always existed in literature. But it has tended in the course of the last century to become specialized partly because so much writing that is not specifically 'nature writing' does not present the natural context at all; because so many novels and so many treatises describe man as an economic unit, a political unit, or as a member of some social class but not as a living creature surrounded by other living things." (Joseph Wood Krutch, "Some Unsentimental Confessions of a Nature Writer." New York Herald Tribune Book Review , 1952)

- Creative Nonfiction

- What Is Literary Journalism?

- The Conservation Movement in America

- Defining Nonfiction Writing

- A Guide to All Types of Narration, With Examples

- What You Should Know About Travel Writing

- The Essay: History and Definition

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- Biography of Henry David Thoreau, American Essayist

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- Thoreau's 'Walden': 'The Battle of the Ants'

- Genres in Literature

- Must Reads If You Like 'Walden'

- Top 5 Books about Social Protest

- Tips on Great Writing: Setting the Scene

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Nature writing is booming – but must a walk in the woods always be meaningful?

When so many of us struggle to find time and money to head outdoors, nature writing offers us vicarious enchantment – regardless of reality

N ature, as both a place and an idea, has become fraught with issues of privilege. Not everyone can access it, nor can they always afford to romanticise it. As biodiversity plummets, our attention becomes bittersweet, leaving nature lovers trapped in an increasingly tragic love story. Yet for any difficulty we may have in facing up to our collective destruction, writing about nature is booming. As readers, we relish these secondhand wanderings, recounted in gorgeous prose. We witness the author’s wonder, and aspire to similar experiences: the natural world as cure, as balm, as wise mentor; wilderness as a fount of authenticity in which we might find our wilder, realer selves.

My own relationship with nature writing is complicated. I am disappointed by my hesitancy when it comes to these books. After all, that most heady brew, where sublime language renders nature’s glories anew is one I personally aspire to concoct as a writer. And I’m often enchanted by writing that achieves it, such as Dorothy Hartley’s 1939 book Made in England , a favourite of mine. Hartley’s descriptions of landscapes and details as she strides out to document dwindling crafts range from the matter-of-fact to the downright fanciful. But all speak of a sharp eye and a guileless joy that make me wish I could tramp alongside her, spotting the small marvels she points out along the way. We might stop and notice the “tiny green tentative fingers” of growing things, or “the crackling cat-ice in the cart ruts” ourselves, but she is not going to linger over them on our behalf – she has work to do. Whether she is enchanted by her surroundings or not, we must infer; she will not tell. Whether you are enchanted is up to you.

Yet so much contemporary nature writing (Hartley sallied out almost a century ago) invites us – sometimes explicitly – to wonder not just at the natural world, but at the author’s experience. Nature writing offers us vicarious enchantment, for how many of us really have the time, the money and the tenacity to make regular, lengthy forays into the wild?

In Crow Country, Mark Cocker’s beautiful and epiphanic account of his growing obsession with rooks, this familiar bird that any of us might encounter in our urban lives becomes magical, “unsheathed entirely from any sense of ordinariness”. As he watches the flock (“an entoptic vision”), it “stirs something edgy” into his sense of wonder. For Cocker, “the underlying goal of any outing is to have an encounter of some meaning”.

He is right, of course. We all long for meaning, and the natural world is a good place to seek it out. But experiencing meaning in nature, being enchanted by her myriad forms, now feels aspirational. I suspect my resistance in the face of nature writing stems from stubbornness: against the implication that if only I connected properly with nature, I would be elevated somehow. On some days, a walk through the woods or along the shore can be disappointing, or even unpleasant, and that is all right. Enchantment is not everywhere all the time; it is an inner state that relies on mood and receptivity quite as much as the appearance of a fox or a grey seal or a charismatic oak.

Nature can also be found anywhere, if we are inclined to look at a certain slant. Books such as Edgelands , by poets Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts, or Clay by Melissa Harrison , remind us of this. While Clay is a novel, it is bursting with nature writing, showing us a scrubby city park in which “every tree and fencepost and path and thicket was charged with an almost mystical significance” for the boy protagonist. He yearns to belong to the world of squirrels and birds that abuts his housing estate. Edgelands celebrates the scraps of unruly wasteland that sidle up against the city – both Farley and Roberts having haunted such places during childhoods when they “wondered where the countryside actually was, or if it really existed”.

There is no doubting that a spot of communing with nature is good for us. Full immersion, then, might be even better. (Though there is nothing like a struggle to get warm and dry, or find your way to safety, to do away with the hunt for meaning.) Has the proliferation of nature writing led to a proliferation of countryside explorers? Are we following the example of intrepid writers and becoming re-enchanted with the world as a result? I rather hope so, though the cynic in me suspects that where nature is not Instagrammable, some will not bother to tread. Having feasted on the intense dramas and exquisite scenery of an Attenborough documentary, a poke around in a rockpool may lose its lure.

Though access to many wild places remains a privilege, access to enchantment and meaning need not be. The more we idolise extreme or unusual experiences of the natural world, the less inclined we will be to bother looking for meaning in our ordinary lives, on our own street, in our local patch of park. But a place that appears thoroughly disenchanting to one person may bewitch another, if they tilt their heads. Robert McFarlane and Jackie Morris’s The Lost Words is an exemplar, explicitly offering us words as magic keys to open up the natural world. It is no accident that this a spell book, since spells alter reality using words. As Ursula Le Guin had it: “Magic consists in this, the true naming of a thing.” Our world may not have much room for magic, but we all speak, write and read the language of enchantment – if we choose to see it that way.

- Science and nature books

- Robert Macfarlane

Most viewed

100 Greatest Books of American Nature Writing

- American Nature Writing

Some Other Important American Books About Nature

Major Anthologies of American Nature Writing

Nature poets.

- 2023 Winners

- 2024 Submissions

- 2023 Shortlist

- 2023 Longlist

- Sponsors & Partners

10th James Cropper Wainwright Prize Announces Winners as Wild Places, Remarkable Habitats and Passionate Advocacy for our Planet are Celebrated

- About the awards

- Previous winners

- Campaign materials

Understanding Ourselves and Our World: Why Nature Writing Matters

Nature writing is in its golden age, but as most of us know, the planet is sinking into an era of darkness. This flourishing of a genre is surely, and hopefully, a testament to the increased value people are placing on our environment, and a sign of the focus being ploughed into conserving it. So many writers are providing vital solutions to protecting our planet, and helping the individual to value and conserve local environments.

“I’m in awe at the skill and passion that writers are demonstrating, using beautiful language and good old fashioned story-telling to help readers understand and connect with ecological concepts and critical conservation issues that might otherwise seem dry and impenetrable.” – Craig Bennett, CEO of Wildlife Trusts

And where works are not polemic or directly calling audiences to action, nature writing is still incredibly important. Nature writing focused on the solace and healing powers that the outdoors can offer us, and our personal relationship to it, is radical in itself.

“Sometimes we forget that as individuals fighting for change, something as simple as recommending a book you loved that gives someone a connection to the natural world can be as powerful as being out on the streets marching with others.” – Roisin Taylor, co-director for UK Youth for Nature

Placing increased value on our natural world is a reevaluation of the ways in which we live. Modern living has left many of us dissatisfied; where urban environments fall short, nature can offer us something else – a new way of seeing the world, living within it, and connecting to it. Observing and noticing nature’s small acts and moments can be wondrous and restorative, decentring us, and taking our mind elsewhere. The very values of environmental communities seem quite divorced from the capitalist structures under which most of us toll. As Robert Macfarlane writes, these are acts of ‘placing community over commodity, modesty over mastery, connection over consumption, the deep over the shallow’.

“The current nature writing highlights a better understanding of the natural world and our place in it. In particular, we see titles that show nature’s importance in providing a restorative environment for individuals and communities.” – Amber Harrison, Co-founder of Folde Dorset

Nature writing has given us a chance to evaluate how we belong in the physical world, the history of the land, the movement of people, and the formation of community. It is wrapped up in our political, social, historical, and philosophical understandings of land and home. As we find new ways to grapple with these issues, a diverse array of people are reclaiming their right to natural spaces, and their stories within them.