- FCUS Courses

- Register for FCUS Course

- What is the ICN?

- The ICN Story

- ICN Hot cases

- Semantic sMatter

- ECG Proving Ground

- ICU Radiology Cases

- Game Changing Evidence

- Pharmacology

- Past Papers

- Approaches to Questions

- Clinical Exam

- Clinical Governance

- Past Papers with Answers

- The ICN meta feed

- Conferences

- Websites & Blogs

- Books & Journals

- Clinical Calculators

Clinical Cases

This section is a collection of critical care clinical cases to test yourself and hopefully get some new ideas.

Please leave feedback and comments, and if you want to put your own hot cases up, please get in touch and we can make it happen.

Can you work out the cause of this DVT?

Pulmonary Artery Catheters: PAC traps for young snake charmers

End-o-bed-o-gram – Case 3

Spot Diagnosis #2

End-o-bed-o-gram – case 2.

The NEJM Critical Care Challenge: Case 11 (Answer)

Spot diagnosis #1, the nejm critical care challenge: case 11 (end of life care), nejm critical care challenge case 10 (sdh) answer, the nejm critical care challenge: case 10 (acute sdh), icu-acquired weakness: nejm critical care challenge case 9 (question and answer).

Nutrition: NEJM Critical Care Challenge Case 8 Answer

End-o-bed-o-gram 1, the nejm critical care challenge: case 8, coagulopathy: nejm critical care challenge case 7 answer, coagulopathy: nejm critical care challenge case 7, icu sedation: nejm critical care challenge case 6 answer, icu sedation: nejm critical care challenge case 6, acute liver failure: nejm critical care challenge case 5 answer, acute liver failure: nejm critical care challenge case 5, ventilation: nejm critical care challenge case 4 answer.

Haemodynamic Monitoring: NEJM Critical Care Challenge Case 3 ANSWER

Haemodynamic monitoring: the nejm critical care challenge case 3, resuscitation fluid: nejm critical care challenge case 2 answer.

The NEJM Critical Care Challenge: Case 2

Septic shock: nejm critical care challenge case 1 answer, septic shock: nejm critical care challenge case 1.

The NEJM Critical Care Challenge: Case 1

Hot Case #14 – I’m pregnant … HELLP!

Hot Case #13 – To bust or not to bust?

ICN Hot Case #12 – Pull my finger!

Hot Case #11 – Testing testing

ICN Hot Case #10

ICN Hot Case #9

ICN Hot Case #8

ICN Hot Case #7

ICN Hot Case # 6

The nejm critical care challenge: case 4.

ICN Hot Case #5

September Case of the month

ICN Hot Case #4

ICN Hot Case #3

- What is ICN

- The Team

- ICN NSW

- ICN QLD

- ICN VIC

- ICN WA

- ICN NZ

- ICN UK

- Lung US

- Exam Help

- Clinical Cases

- Echo Cases

- Echo Guide

- ICU Radiology

- Game Changing Evidence

- ICN Metafeed

- Simulation Resouces

- SMACC Posters

- Audio

- Video

- Pecha Kuchas

- End-o-Bed-o-Gram

- ICU Primary Exam

- CICM Fellowship

- ANZCA Fellowship

- Paeds Fellowship

- Emergency Primary

- Anaesthetics Primary

® 2024 The Intensive Care Network || All rights reserved || Disclaimer || Site Map || Contact ICN Support

Log in with your credentials

or Create an account

Forgot your details?

Create account.

- Medical Books

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Case Studies in Critical Care Nursing: A Guide for Application and Review 3rd Edition

- Each chapter contains the case presentation, questions and answers, and references.

- Each case study includes patient assessment and history of the disorder, laboratory observations and results, and pharmacological options for the patient.

- Comprehensive discussion and evaluation of the critical thinking questions follow each case study.

- Internet resources are included throughout the case studies to further the user's access to information on a variety of disorders.

- Contains an all-inclusive glossary of key critical care abbreviations.

- ISBN-10 0721603440

- ISBN-13 978-0721603445

- Edition 3rd

- Publisher Saunders

- Publication date March 5, 2004

- Language English

- Dimensions 8.5 x 1 x 10.5 inches

- Print length 528 pages

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Saunders; 3rd edition (March 5, 2004)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 528 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0721603440

- ISBN-13 : 978-0721603445

- Item Weight : 2.87 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.5 x 1 x 10.5 inches

- #278 in Nursing Critical & Intensive care

- #341 in Critical Care

- #5,113 in Core

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- CPD articles

- CPD Quizzes

- Expert advice

- Clinical placements

- Study skills

- Clinical skills

- University life

- Person-centred care

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Book review Previous Next

Case studies in critical care nursing, maureen eby.

Case Studies in Critical Care Nursing is an exciting book for the critical care nurse who is striving to develop skills in analysing the complex needs of the critically ill patient. It will enable nurses to play a vital role in co-ordinating and focusing the efforts of the many health care workers toward realistic patient-orientated goals.

Nursing Standard . 5, 45, 43-43. doi: 10.7748/ns.5.45.43.s58

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

31 July 1991 / Vol 5 issue 45

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Case Studies in Critical Care Nursing

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Innovative solutions: using case studies to generate increased nurse's clinical decision-making ability in critical care

Affiliation.

- 1 Family Nurse Practitioner Specialty, Fairfield University School of Nursing, Fairfield, CT 06824, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 20395734

- DOI: 10.1097/DCC.0b013e3181d24d86

Learning to care for critically ill patients requires a high level of critical thinking, clinical decision-making ability, and a substantial knowledge base. At this nursing school, an elective Critical Care Nursing course for last-semester seniors was designed to include active learning strategies, focusing on the use of case studies to facilitate learning. Results indicate significantly improved final examination scores for those involved with the case-study pedagogy. In addition, students identified enhanced communication skills. Two complex cases are presented for others to use with their educational programs.

Critical care nurses’ communication experiences with patients and families in an intensive care unit: A qualitative study

Hye jin yoo.

1 Department of Nursing, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea

Oak Bun Lim

Jae lan shim.

2 College of Medicine, Department of Nursing, Dongguk University, Gyeongju, South Korea

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

This study evaluated the communication experiences of critical care nurses while caring for patients in an intensive care unit setting. We have collected qualitative data from 16 critical care nurses working in the intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital in Seoul, Korea, through two focus-group discussions and four in-depth individual interviews. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, and data were analyzed using the Colaizzi’s method. Three themes of nurses’ communication experiences were identified: facing unexpected communication difficulties, learning through trial and error, and recognizing communication experiences as being essential for care. Nurses recognized that communication is essential for quality care. Our findings indicate that critical care nurses should continuously aim to improve their existing skills regarding communication with patients and their care givers and acquire new communication skills to aid patient care.

Introduction

Critical care nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs) care for critically-ill patients, and their work scope can include communicating with patients’ loved ones and care givers [ 1 ]. In such settings, nurses must make timely judgments based on their expertise, and this requires a high level of communication competency to comprehensively evaluate the needs of patients and their families [ 2 , 3 ]. The objective of nurses’ communication is to optimize the care provided to patients [ 4 ]. Therapeutic communication, a fundamental component of nursing, involves the use of specific strategies to encourage patients to express feelings and ideas and to convey acceptance and respect. In building an effective therapeutic relationship, a focus on the patient and a genuine display of empathy is required [ 5 ]. Empathy is the ability to understand and share another person’s emotions. To convey empathy towards a patient, one must accurately perceive the patient’s situation, communicate that perception to the patient, and act on the perception to help the patient [ 6 ]. Effective communication based on empathy not only contributes greatly to the patient's recovery [ 3 , 5 – 7 ], but also has a positive effect of improving job satisfaction by nursing with confidence [ 8 ] In contrast, inefficient communication leads to complaints and anxiety in patients and can also lead to other negative outcomes, such as extended hospital stays, increased mortality, burnout, job stress, and turnover [ 9 , 10 ].

Therefore, communication experiences need investigation since effective communication is an essential for critical care nurses. Nurses use curative communication skills to provide new information, encourage understanding of patient’s responses to health troubles, explore choices for care, help in decision making, and facilitate patient wellbeing [ 11 ]. Particularly, patient- and family-centered communication contributes to promoting patient safety and improving the quality of care [ 12 , 13 ]. However, communication skills are relatively poorly developed among critical care nurses compared to nurses in wards and younger and less experienced nurses than in their older and more experienced counterparts [ 3 , 7 , 14 – 16 ]. This calls for an examination of the overall communication experiences of critical care nurses.

To date, most studies on the communication of critical care nurses have been quantitative and have evaluated work performance, association with burnout, and factors that hinder communication [ 2 – 4 , 7 ]. A qualitative study has examined communications with families of ICU patients in Korea [ 17 ], while an international study has identified factors that promote or hinder communication between nurses and families of ICU patients [ 16 , 18 ]; however, few studies have been conducted on participant-oriented communication (including patients and families). Nurses’ communication with patients and their families in a clinical setting is complex and cannot be understood solely on the basis of questionnaire surveys; therefore, these communication experiences must be studied in depth.

This study explored critical care nurses’ communication experiences with patients and their families using an in-depth qualitative research methodology. This study will help to enhance communication skills of critical care nurses, thereby improving the quality of care in an ICU setting.

Materials and methods

This study employed a qualitative descriptive design using focus-group interviews (FGIs) and in-depth individual interviews and was performed according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist [ 19 ]. An FGI is a research methodology in which individuals engage in an intensive and in-depth discussion of a specific topic to explore their experiences and identify common themes based on the interactions among group members [ 20 ]. Individual in-depth interviews were also conducted to complement the content identified in FGIs and further explore the deeper information developed based on experiences at the individual level.

Participants

Sixteen critical care trained nurses providing direct care to patients in an ICU of a tertiary hospital in Seoul were included in this study. The purpose of this study and the contents of the questionnaire were explained to them, and they voluntarily agreed to participate and complete the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) nurses with a hearing problem; 2) nurses with less than 1 year of clinical experience; and 3) nurses diagnosed with psychiatric disorders.

Snowball sampling—in which participants recruit other participants who can vividly share their experiences regarding the topic under investigation—was used. Six participants for the first FGI, six for the second FGI, and four for the individual in-depth interviews were recruited. All participants were women (mean age = 29.0 years old; mean nursing experience = 4.5 years). Their characteristics are listed in Table 1 .

Data collection

Developing interview questions.

The interview questions were structured according to the guidelines developed for the focus-group methodology [ 21 ]: 1) introductory questions, 2) transitional questions, 3) key questions, and 4) ending questions. The questions were reviewed by a nursing professor with extensive experience in qualitative research and three critical care nurses with more than 10 years of ICU experience ( Table 2 ). These questions were also used for individual face-to-face in-depth interviews.

Conducting FGIs and individual interviews

The two FGIs and four individual interviews were conducted between July 20, 2019 and September 30, 2019. The FGIs were moderated by the principal female investigator and were conducted in a quiet conference room where participants were gathered around a table to encourage them to talk freely. The FGIs were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent, and the recordings were transcribed and analyzed immediately after. Similar content was observed from the two rounds of FGIs, and we continued the discussion until no new topics emerged.

To complement the FGIs and verify the results of the analysis, we also conducted individual interviews of four participants. One assistant helped in facilitating the interviews and took notes. The duration of each interview was about 60–90 minutes.

Ethical considerations and investigator training and preparation

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Asan Medical Center (approval no. 2019–0859). Prior to data collection, participants provided written informed consent and were informed in advance that the interviews would be audio-recorded, their participation would remain confidential, the recordings and transcripts would only be used for research purposes, the data would be securely stored under a double lock and would be accessed by the investigators only, and personal information would be deleted upon the completion of the study to eliminate any possibility of a privacy breach. The collected data were coded and stored to be accessed by the investigators only to prevent leakage of any personal information.

The authors of this study are nurses with more than 10 years of ICU experience and a deep understanding of critical care. The principal investigator took a qualitative research course in graduate school and has conducted multiple qualitative studies to enhance her qualitative research experience.

Data analysis

We utilized Colaizzi’s [ 22 ] method of phenomenological analysis to understand and describe the fundamentals and meaning of nurses’ communication experiences with patients and families. Data analysis was conducted in seven steps: 1) Recording and transcription of the in-depth interviews (all authors read the transcripts repeatedly to better understand the participants’ meaning); 2) Collection of meaningful statements from phrases and sentences containing phenomena relating to the communication experiences in the ICU. We extracted statements overlapping with statements of similar meaning—taking representative ones of similar statements—and omitted the rest; 3) Searching for other interpretations of participant statements using various contexts; 4) Extraction of themes from relevant meanings and development of a coding tree, with the meanings organized into themes; 5) Organization of similar topics into a more general and abstract collection of themes; 6) Validation of the collection of themes by cross-checking and comparing with the original data; 7) After integrating the analyzed content into one technique, the overall structure of the findings was described.

During data analysis, we received advice on the use of language or result of analyzing from a nursing professor with extensive experience in qualitative research and had the data verified by three participants to establish the universality and validity of the identified themes.

Establishing precision

The credibility, fittingness, auditability, and confirmability of the study were evaluated to analyze our findings [ 23 ]. To increase credibility, we conducted the interviews in a quiet place to focus on participants’ statements and help participants feel comfortable during interviews; to establish the universality and validity of the identified themes, data verification was performed by three participants. To ensure uniformity in data, participants who could provide detailed accounts of their experiences were selected, and the data were collected and analyzed until saturation was achieved (i.e., no new content emerged). To ensure auditability, the raw data for the identified themes were presented in the results, such that the readers could understand the decision-making process. To ensure confirmability, our preconceptions or biases regarding the participants’ statements were consistently reviewed to minimize the impact of bias and maintain neutrality.

After analyzing the communication experiences of 16 critical care nurses, three major themes emerged: facing unexpected communication difficulties, learning through trial and error, and recognizing communication experiences as being essential for care. The results are summarized in Table 3 .

The results of this study are schematized based on Travelbee's Human-to-Human Relationship Model [ 24 , 25 ] ( Fig 1 ), which suggests that human-to-human interaction is at a developmental stage. In this study, communication between patients and their families and experienced nurses in ICUs promotes human-to-human connections, leading to a genuine caring relationship through interaction, empathy, listening, sharing, and respect, which are all therapeutic communication skills.

Theme 1: Facing unexpected communication difficulties

Nurses experienced more difficulties in communicating with patients and their families and caregivers than in performing essential nursing activities (e.g., medication administration, suction, and various mechanical operations) The communication difficulties they experienced were either nurse-, patient- and family-, or system-related. Distinct problems in an ICU are related to urgency; for example, hemodynamically unstable patients or patients with respiratory failure or those suffering from a cardiac arrest may be prioritized.

Nurse-related factor: True intentions were not conveyed as wished

Although nurses intend to treat patients and their families with empathy, they frequently lead one-way conversations when pressed for time in the ICU. In addition, their usual way of talking, such as their dialect and intonation, can sometimes be misunderstood and cause offense. Participants experienced difficulties communicating their sincerity to patients and their families.

“Oftentimes, I only say what I have to say instead of what the caregivers really want to know when I’m pressed for time to convey my thoughts and go on to the next patient to explain things to the other patient.” (Participant 2)

“I usually speak loudly, and I speak in dialect; so, things I say are not delivered gently…I try to be careful because my dialect can seem more aggressive than the Seoul dialect; but it’s not easy to fix what I have used for all my life at once.” (Participant 3)

Nurse-related factor: Hesitant to provide physical comfort

Participants were not familiar with using non-verbal communication. The participants realized the importance of both verbal communication and physical contact in providing care, but the application of both these communication styles was not easy in clinical practice.

“I want to console the caregivers of patients who pass away; but I just can’t because I get shy. I feel like I’m overstepping, and when I’m contemplating whether I can really speak to their emotions, the caregiver has already left the ICU in many cases.” (Participant 6)

“I’m really bad at physical contact even with my close friends; but I’m even worse when it comes to patients and caregivers. Because of my tendency, there are times when I hesitate to touch patients while providing care.” (Participant 7)

Patient- and family-related factor: Mechanical ventilation hindering communication with the patient

Mechanical ventilators were the greatest obstruction to communication in ICU. Although it is normal for patients on a mechanical ventilator to lose the ability to speak, patients and their families did not understand how mechanical ventilators work and were frustrated that they could not communicate freely with the patient. Participants expressed difficulty in communicating with patients in ways other than verbal communication as well.

“Patients who are on mechanical ventilation can’t talk as they want and do not have enough strength in their hands to write correctly; so, even if I try to listen to them, I just can’t understand what they are saying. You know in that game where people wear headphones playing loud music and try to communicate with one another—words completely deviant from the original word are conveyed. It just feels like that.” (Participant 9)

“Patients on mechanical ventilation and who thus cannot communicate are the most difficult. The patient keeps talking; so, it hinders respiration—the ventilator alarm keeps going off, the stomach becomes gassy, and the patient has to take the tube off and vomit later. No matter how much I explain, there are patients or caregivers who tell me that the tube in the throat is making [it] hard [for them] to breathe or [they] ask me to take it off just once and put it back on, and these patients are really difficult. There is no way to communicate if they cannot accept mechanical ventilators even if I explain.” (Participant 8)

Patient- and family-related factor: Caregivers’ negative responses to nurses

It was also burdensome for nurses to communicate with extremely stressed caregivers and loved ones, especially when patients were in a critical state. Despite the role of nurses in helping patients during health recovery, caregivers’ negative responses to nurses, such as blaming them and speaking and behaving aggressively, intimidated the participants and ultimately discouraged conversations.

“I can manage the patients’ poor vital signs by working hard but communicating with sensitive caregivers who project their anxiety about the patient’s state onto nurses doesn’t go as I wish, so, it’s really difficult and burdensome.” (Participant 6)

“When the patient is in a bad state, caregivers sometimes want to not accept it and project their feelings onto the nurses, and in such cases, there are no words that can console them. Even approaching the caregivers is a burden, and I get kind of intimidated.” (Participant 5)

System-related factor: Lack of experience and a mismatch between theory and practice

Participants have learned the importance of communication during training; however, they had trouble appropriately applying the learned concepts in their workplace. Participants in this study were in their 20s and 30s, with limited life and social experiences, and felt the gap between theory and practice in communicating with patients and families in ICU.

“Talking to the patient or caregiver was the most challenging thing when I was new…it is impossible for nurses with not much life experience to communicate skillfully.” (Participant 10)

“It would be nice if the real-world conversation proceeds in the way shown in our textbook; but it doesn’t in most cases. So, it is more practical to observe and learn from what other nurses do in the actual field.” (Participant 2)

System-related factor: Intense visiting hours in limited time

The 30-minute ICU visiting period is the only time when patients and families can talk to one another. Although nurses are well trained to care for the patients to the best of their ability, caregivers distrust the nurses’ ability to care for patients since caregivers only have a limited amount of visiting time, thus hindering effective communication. Some participants even experienced mental trauma following short but unforgettable interactions with caregivers.

“…the caregiver browbeat me and intimidated me for doing so. This gave me a mental trauma for visiting hours…I didn’t know how to start a conversation and the visiting hours were really stressful for me.” (Participant 3)

“The caregivers don’t stay in the ICU for 24 hours; so, once they begin to doubt our nursing practice, we cannot continue our conversation with them…” (Participant 11)

System-related factor: Urgent workplace that deprioritizes communication

The ICU is a unit for treating critically-ill patients; therefore, ICU nurses were more focused on tasks directly linked to maintaining patients’ health, such as stabilizing vital signs, than on communication. Participants frequently encountered emergency situations, in which they could not idly stay around to communicate with one patient because another required immediate assistance, i.e., they faced a reality in which they had to prioritize another patients’ health over communication with one.

“…I’m really pressed for time when the patient keeps writing things I can’t understand with their weak hands…I don’t have time to spare even if I want to listen to them.” (Participant 12)

“Vital signs are the utmost priority in [the] ICU. I’m on my feet the entire shift and don’t even have time to go to the restroom…During early ICU treatment, there are a lot of emergency situations; so, communication is way down in the priority list.” (Participant 5)

Theme 2: Learning through trial and error

The negative experiences arising from communicating with various individuals sometimes forced nurses to think twice about their vocation; however, due to a sense of responsibility, they tried to engage in therapeutic communication and to overcome difficulties.

Fundamental doubts about the nursing profession

Experiencing unfriendly and confrontational conversations with patients and caregivers was intolerable for participants. These experiences were shocking enough to make them fundamentally question their decision to choose and stay in the nursing profession.

“I felt so disappointed and frustrated when patients or caregivers bombard[ed] rude comments at me with complete disregard of what I have done over a long period…I can’t sleep well at night and my values as [a] nurse are shaken from their root.” (Participant 14)

“It becomes so difficult the moment communication fails and mutual trust is lost. Maybe I could survive if this is just with one patient or caregiver; but the afterimage lingers with me persistently while I’m working…I came to think whether I could continue nursing.” (Participant 7)

Finding out which communication style is better suited for patients and their families

Nurses learned how to resolve communication-related difficulties that they encountered from their seniors and mentors and tried to communicate better from their position at the nursing station.

“A senior nurse of mine was talking to a caregiver who was really concerned, and she was using affirmations like ‘Oh, really’ and ‘I see’ with a relaxed facial expression, and the caregiver would spill her heart out to her. That’s when I thought that empathy is to express responses to what the other person is saying.” (Participant 10)

“I can feel that I am able to bond with patients’ families when I tell them about the patient’s daily living, such as how much the patient had slept, eaten, and whether the patient was not in pain, during visiting hours.” (Participant 13)

Knowhow learned through persistent effort

Nursing activities, such as taking vital signs and performing aspiration and intravenous injection, are learned over time; however, it is impossible to acquire therapeutic communication skills without personal effort and interactive experiences in the field.

“I’m reading a book about conversation and am learning about how to express empathy and understand other people…Nursing skills are developed and improved over time; but it’s not easy to enhance communication without personal effort or change in perception.” (Participant 16)

“Communication is an indispensable part of nursing. If you want to provide high-quality care, you need to enhance your communication skills first.” (Participant 15)

Theme 3: Recognizing communication experiences as being essential for care

Nursing and communication are inseparable. Although communication is a challenge while caring for ICU patients, therapeutic communication is important for the patients’ and their families’ overall wellbeing. In an ICU, communication based on empathy and experience is a significant component that helps patients perceive their illnesses more positively.

Empathy garnered through various clinical experiences

Since participants met many patients and their families in the ICU, they were able to communicate. Participants understood patients’ discomfort and learn why it was difficult for them to communicate and to comfort and assure unease families who could not observe the patient's condition. However, it was a necessary communication method in the ICU. Participants realized the value and importance of their words.

“…his endotracheal tube was touching his throat and was so uncomfortable: his mouth was dry, he couldn’t talk, and his arms were tied; so, he thought the only way to communicate was to use his legs and that’s why he was kicking. I felt really sorry…” (Participant 7)

“I gave a little detailed explanation to the caregiver during visiting hours and she thanked me overwhelmingly. I feel that, because this is the ICU, patients and caregivers can be encouraged and discouraged by the words of the medical professionals.” (Participant 9)

The power of active listening

Although the ability to handle tasks promptly is important, listening to patients amid the hectic work schedule in the ICU is also an important nursing skill. Critical care nurses realized that listening to patients and caregivers without saying anything is also meaningful and therapeutic.

“I was listening to the caregiver the entire duration of the visiting hour…She said that she just had to open up to someone to talk about her frustrations, and that my listening to her was a huge consolation for her.” (Participant 12)

“While listening to the caregiver and showing empathy every day at the same time, I was able to witness that the caregiver who had been aggressive and edgy changed in a way to trust in and depend on the nurse more.” (Participant 16)

Mediator between physicians, patients, and caregivers

Participants were at the center of communication, serving as the bridge connecting physicians to patients and patients to caregivers. They served as mediators, explaining the doctors’ comments to the caregivers, and providing details regarding the patients’ state to families. Participants helped maintain a close and balanced relationship between the doctor, the patients, and their families by conveying messages not effectively communicated by the doctor or patients.

“Caregivers would not ask any questions to the doctor in the ICU and would ask me instead once the doctor is gone. They would ask, ‘what did the doctor say?’ and ask me for an explanation.” (Participant 4)

“The patients can’t say everything they want; so, as nurses, we are the mediators between patients and caregivers…Tell[ing] the family about things that happened when they were not around the patient is meaningful.” (Participant 14)

Expressing warmth and respect

Participants have experienced sharing emotions with the patient's family as well as with the patient during disease improvement and exacerbation.

In particular, sincere actions, such as staying with the families of patients who died or those whose condition was deteriorating, led to more genuine relationships, as respect for human life was expressed.

“When patients whom we have spent a long time [with] are about to pass away, we cry for them and we stay beside them in their final moments…Showing respect for a person’s final moments of life and expressing our hearts is meaningful, and it is something critical care nurses must do.” (Participant 16)

“When the patient’s state worsened and…his daughter was sobbing next to him…I softly touched her shoulder, and she really thanked me. As I saw the patient’s family grieve, I just expressed how I felt, and, fortunately, my intention was well conveyed” (Participant 4)

This study evaluated critical care nurses’ communication skills and experiences with patients and their caregivers. Based on the two FGIs and four individual in-depth interviews, three themes have been identified: 1) facing unexpected communication difficulties; 2) learning through trial and error; and 3) recognizing communication experiences as being essential for care

For theme 1, we examined nurse-, patient-, family-, and system-related (i.e., pertaining to hospital resources and education) factors. Theme 1 can be considered as the communication involving human-to-human interaction, as mentioned in Travelbee [ 24 , 25 ], that takes place at an incomplete stage. First, critical care nurses struggled with balancing their heavy workload and communicating with patients and their families. In Korea, an ICU nurse, on an average, cares for two to four patients, which is higher than in some other countries, wherein an ICU nurse cares for one or two patients at the most; thus, the Korean work environment for ICU nurses is more stressful [ 26 ]. This limits the amount of time nurses may have to communicate and interact with their patients and caregivers. Misunderstandings are also common owing to the patients’ inability to speak while intubated and to use of regional dialects. Patients and caregivers want to hear specific and comprehensible information from health professionals regarding the treatment procedures in the ICU [ 17 , 27 ]. However, previous studies [ 4 , 28 ] have reported that critical care nurses experience communication difficulties due to high mental pressure due to work, time constraints, and the inability to use their own language; these are consistent with our findings. As nurses are required to interact with patients having various needs, they need to learn how to communicate verbally and nonverbally in a sophisticated manner [ 27 ], and hospital managers should implement practical communication programs in the ICU.

Communication between nurses and their patients in the ICU is also often adversely affected by the therapeutic environment, such as patient emergencies and the use of mechanical ventilation [ 27 , 28 ]. Mechanical ventilators are one of the greatest obstacles to communication. Although they are essential for critically-ill patients who are incapable of spontaneous breathing, they affect their ability to speak [ 29 ]; therefore, these patients need to employ other strategies for communication, such as using facial expressions and lip movements, which make communication extremely difficult [ 27 , 30 ]. Our participants strived to understand the needs of critically-ill patients through verbal and nonverbal communication, such as writing and body language. However, when the intentions were not conveyed properly, some patients responded aggressively, hindering respiratory treatment and ultimately prolonging treatment. This is in line with many previous findings [ 29 , 31 , 32 ] indicating that patients’ failure to effectively express their needs to nurses or their family members triggers negative emotions. In addition, participants had trouble interacting with caregivers who were extremely tense and sensitive. According to Lee and Yi [ 17 ], families of critically-ill patients experience fear and anxiety regarding the patients’ health state and strive to save the patient. Thus, nurses must consider this when addressing vulnerable patients and their families and must actively identify and resolve causes of discomfort in patients on mechanical ventilation (i.e., by using appropriate analgesics/sedatives and removing the ventilator). Further, considering a systematic review revealing that electronic communication devices enable efficient communication with critically-ill patients through touch or eye blinks [ 33 ], Korea should also keep abreast with technological advances in communication technology.

Concerning theme 2, as participants experienced emotional exhaustion from being misunderstood or unfairly criticized by patients and their families, they contemplated and doubted the occupational values of nursing. Park and Lee [ 7 ] found that higher job satisfaction for ICU nurses is associated with better communication. This is consistent with our participants’ doubt for choosing the nursing profession. However, instead of giving up on this profession, they closely observed the effective communication skills of more experienced nurses, actively learned about therapeutic communication through books and videos, and applied their learnings during practice. Similar results were reported by Park and Oh [ 3 ] that patient-centered communication competency among critical care nurses was the highest when a biopsychosocial perspective, focused on delivery of factual information, was followed and the lowest in the therapeutic alliance domain, which is required for performing cooperative care with patients. Therapeutic communication provided by nurses to patients and their families in the ICU effectively diminished their psychological burden and fostered positive responses from families [ 34 ]. Currently, ICUs implement a systematic education system for nurses that focuses on therapeutic techniques, such as hemodynamic monitoring, mechanical ventilation care, aspiration, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; however, they lack a program targeting effective therapeutic communication with patients and caregivers. The communication difficulties experienced by nurses will persist without this additional program; thus, its implementation is critical to improve patient satisfaction and nursing quality of care. Further, instead of coercing unilateral effort from critical care nurses, nurse managers should pay attention to nurses’ emotional wellbeing and promptly develop systems to offset potential burnout, such as voluntary counseling systems or measures to “refresh” nurses.

Concerning theme 3, participants learned that communication is a challenging but essential aspect of critical care. The concept of communication resonates through Travelbee’s model [ 24 , 25 ]. Getting to know another human being is as important as performing procedures. A nurse must establish a rapport with the patient and the patient’s caregivers, otherwise he or she will not know the patient’s needs. As a place where life-and-death decisions are made, the ICU induces anxiety in critically-ill patients and their caregivers. Hence, nurses should fully empathize with patients and their caregivers [ 4 , 5 , 17 ].

Travelbee [ 24 , 25 ] emphasized the relationship between the nurse and the patient by establishing the Human-to-Human relationship model, which gives meaning to disease and suffering based on empathy, compassion, and rapport building. In addition, it presents concepts, such as disease, hope, human-to-human relations, communication, interaction, patient’s needs, perception, pain, finding meaning, therapeutic use of communication, and self-actualization. The participants cultivated empathy and active listening skills when speaking with patients and their families, and, as they spend more time doing so, their quality of care and nonverbal communication skills (such as eye contact, soft touch, and tears) improve and became more genuine. Our findings are consistent with the meaning of human-centered care suggested by Jang and Kim [ 35 ], which involves paying close attention to and protecting patients’ lives, deeply empathizing with patients from a humanistic perspective, and being sincere. The experience of nursing, including active interaction, has a positive impact on establishing the roles and caring attitudes of professional nurses [ 36 ], which is significant for critical care nurses. Patient-family-centered care, which has been confirmed to positively promote critically-ill patients’ recovery worldwide [ 1 ], is possible when nurses engage in therapeutic communication with patients and their families through dynamic interactions [ 34 , 37 ]. Therefore, critical care nurses and nurse managers should pay attention to communication and develop an effective communication course that can be applied in clinical practice. To do this, first, it is necessary to hire appropriate nursing personnel for active therapeutic communication with the patients and their families in an ICU. Second, continuous, and diverse educational opportunities should be provided to critical care nurses, along with policy strategies. For example, at the organizational level, it is necessary to develop manuals on how to deal with difficult situations by gathering challenging communication cases from actual clinical practice. Simulation education for communication is an important component of the nursing curriculum.

Limitations

First, this study included a small number of participants; however, we ensured that the maximum data was collected from these participants. Second, specific information was collected from only those nurses who provided direct care in the ICU of a general hospital in a large city in Korea. The homogeneity and dynamics of the focus groups may have resulted in congruent opinions. Third, because the experiences of nurses from only one hospital were analyzed, caution should be exercised in generalizing our results and applying them to other hospitals in Korea. Therefore, follow-up studies with larger sample sizes and more representative participants are warranted.

This qualitative study explored critical care nurses’ communication skills and experiences with patients and caregivers from various perspectives. Although these nurses felt discouraged by the unexpected communication difficulties with patients and their families, they recognized that they could address these difficulties by improving their communication skills over time through experience and learning. They realized that empathy, active listening, and physical interaction with patients and their families enabled meaningful communication and have gradually learned that effective communication is an indispensable tool in providing nursing care to critically-ill patients.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments.

The authors would like to thank all the participants for their time and contribution in this study.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Dongguk University Nursing Academy-Industry Cooperation Research Fund of 2018.The funder had no role in study design, data collectionand analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript

Data Availability

LOGIN

Annual Report

- Board of Directors

- Nomination Process

- Organizational Structure

- ATS Policies

- ATS Website

- MyATS Tutorial

- ATS Experts

- Press Releases

Member Newsletters

- ATS in the News

- ATS Conference News

- Embargo Policy

ATS Social Media

Breathe easy podcasts, ethics & coi, health equity, industry resources.

- Value of Collaboration

- Corporate Members

- Advertising Opportunities

- Clinical Trials

- Financial Disclosure

In Memoriam

Global health.

- International Trainee Scholarships (ITS)

- MECOR Program

- Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS)

- 2019 Latin American Critical Care Conference

Peer Organizations

Careers at ats, affordable care act, ats comments and testimony, forum of international respiratory societies, tobacco control, tuberculosis, washington letter.

- Clinical Resources

- ATS Quick Hits

- Asthma Center

Best of ATS Video Lecture Series

- Coronavirus

- Critical Care

- Disaster Related Resources

- Disease Related Resources

- Resources for Patients

- Resources for Practices

- Vaccine Resource Center

- Career Development

- Resident & Medical Students

- Junior Faculty

- Training Program Directors

- ATS Reading List

- ATS Scholarships

- ATS Virtual Network

ATS Podcasts

- ATS Webinars

- Professional Accreditation

Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT)

- Calendar of Events

Patient Resources

- Asthma Today

- Breathing in America

- Fact Sheets: A-Z

- Fact Sheets: Topic Specific

- Patient Videos

- Other Patient Resources

Lung Disease Week

Public advisory roundtable.

- PAR Publications

- PAR at the ATS Conference

Assemblies & Sections

- Abstract Scholarships

- ATS Mentoring Programs

- ATS Official Documents

- ATS Interest Groups

- Genetics and Genomics

- Medical Education

- Terrorism and Inhalation Disasters

- Allergy, Immunology & Inflammation

- Behavioral Science and Health Services Research

- Clinical Problems

- Environmental, Occupational & Population Health

- Pulmonary Circulation

- Pulmonary Infections and Tuberculosis

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology

- Respiratory Structure & Function

- Sleep & Respiratory Neurobiology

- Thoracic Oncology

- Joint ATS/CHEST Clinical Practice Committee

- Clinicians Advisory

- Council of Chapter Representatives

- Documents Development and Implementation

- Drug/Device Discovery and Development

- Environmental Health Policy

- Ethics and Conflict of Interest

- Health Equity and Diversity Committee

- Health Policy

- International Conference Committee

- International Health

- Members In Transition and Training

- View more...

- Membership Benefits

- Categories & Fees

- Special Membership Programs

- Renew Your Membership

- Update Your Profile

- ATS DocMatter Community

- Respiratory Medicine Book Series

- Elizabeth A. Rich, MD Award

- Member Directory

- ATS Career Center

- Welcome Trainees

- ATS Wellness

- Thoracic Society Chapters

- Chapter Publications

- CME Sponsorship

Corporate Membership

Clinical cases, professionals.

- Respiratory Health Awards

- Clinicians Chat

- Ethics and COI

- Pulmonary Function Testing

- ATS Resources

- Live from the CCD

- Pediatric Division Directors

Massive Pulmonary Embolism

Claire L. Keating, M.D.

Jennifer A. Cunningham, M.D.

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

HISTORY: 55-year-old female nursing home resident with past medical history of AIDS, dilated cardiomyopathy (estimated left ventricular ejection fraction 15% on a previous transthoracic echocardiogram), and prior deep venous thrombosis (DVT) was found to be hypotensive and in respiratory distress while at her skilled nursing facility.

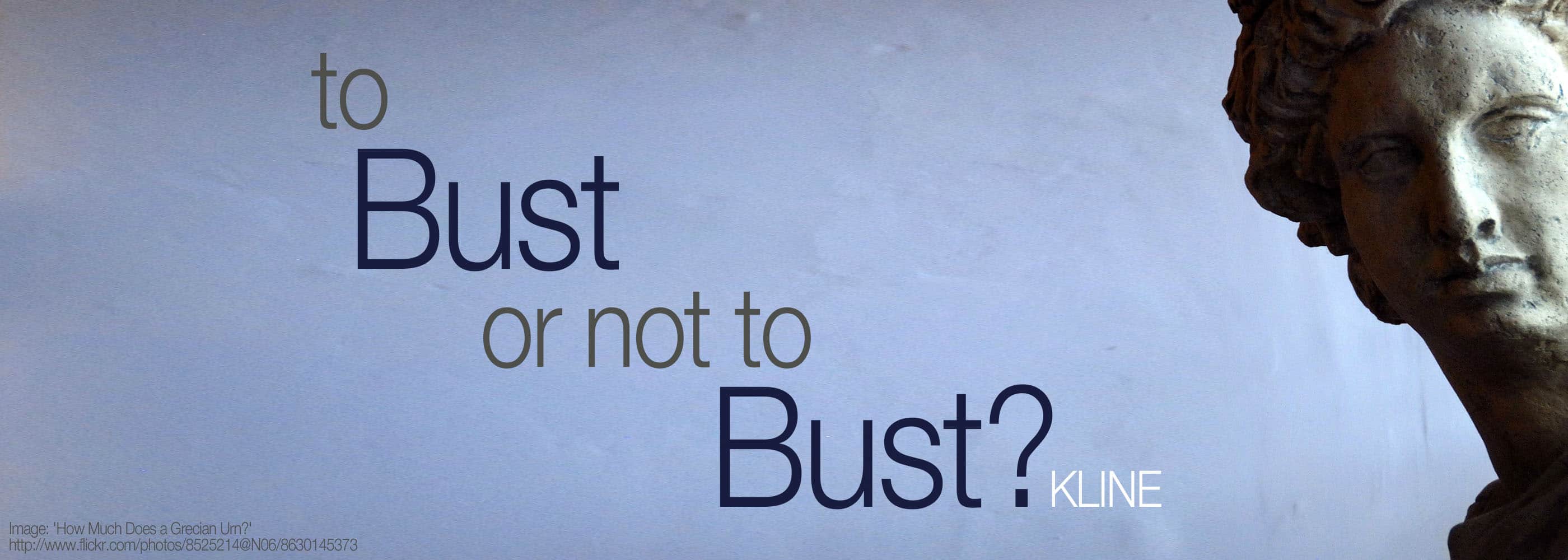

She was brought to the emergency department, where vital signs were notable for temperature of 100.9ºF, HR=142/min, BP=90/60 mmHg after intravenous fluids, with oxygen saturation of 99% while breathing 100% oxygen via non-rebreather mask. Computed tomography of the chest with pulmonary angiogram protocol (Figure 1) revealed large, thrombi in the right main and left main pulmonary arteries with incomplete occlusion, in addition to multiple segmental thrombi in right upper, middle and lower lobes. No lower extremity deep vein thromboses were noted on venogram. Anticoagulation was initiated and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management.

FIGURE 1: CT scan of the chest demonstrating pulmonary emboli in bilateral main pulmonary artery

What distinguishes massive from submassive pulmonary embolism?

- the presence of hypoxemia

- the presence of right ventricular dysfunction

- the presence of shock

- the presence of pulmonary hypertension

- the presence of concurrent deep venous thrombosis

Answer to Question 1

Correct answer: C

The main criteria defining a massive pulmonary embolism are signs of hemodynamic compromise [1]. These include:

-Arterial hypotension defined as systolic arterial blood pressure <90mmHg or a drop in systolic arterial blood pressure of at least 40mmHg for at least 15 minutes (mortality 15%) -Cardiogenic shock as manifested by tissue hypoperfusion and hypoxia, altered level of consciousness, oliguria, or cool, clammy extremities (mortality 25%) -Circulatory collapse requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation (mortality 65%)

Patients with submassive pulmonary emboli are normotensive with signs of right ventricular dysfunction present (see below).

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY: AIDS (CD4+ cell count=20/mm3) Multiple cerebrovascular infarcts with residual expressive aphasia and hemiparesis Dilated cardiomyopathy (presumed HIV-related) Hypertension Chronic kidney disease with baseline serum creatinine of 1.5 mg/dL Past DVT (not on anticoagulation for unclear reasons)

MEDICATIONS: Clopidogrel ASA Enalapril Furosemide Levetiracetam Abacavir Lamivudine Zidovudine Efavirenz

PHYSICAL EXAM: Upon admission to ICU Vitals: T=100.1ºF, HR=112/min, BP=91/63 mmHg, RR=28/min, SpO2=96% on 100% oxygen via nonrebreather mask General: awake, nonverbal, dyspneic and diaphoretic HEENT: Eyes deviated left, pupils 3mm and reactive, JVP estimated at 8cm H2O Heart: tachycardic, regular with frequent ectopy, grade 3/6 holosystolic murmur and S3 gallop present, point of maximal impulse displaced laterally Lungs: coarse breath sounds bilaterally Abdomen: soft, nontender, hypoactive bowel sounds, pulsatile liver, brown guaiac negative stool Extremities: right upper extremity with decreased tone, 1+ edema in lower extremities bilaterally, all extremities cool to touch Neurologic: withdrawal to pain in all extremities, spontaneous eye opening, non-attentive, nonverbal and not following commands.

ADMISSION LABORATORY VALUES: White blood count 14,600/mm3 Hemoglobin 10.6 g/dL Platelets 125,000/ mm3

Sodium 134 mmol/L Potassium 4.6 mmol/L Chloride 107 mmol/L Bicarbonate 13 mmol/L Blood urea nitrogen 45 mg/dL Creatinine 2.8 mg/dL (baseline 1.5) Serum glucose 102 mg/dL Troponin 2.7 ng/mL (upper limit normal = 0.08) BNP 1,944 pg/mL (upper limit normal = 100-400)

Arterial Blood Gases: Emergency Room (on 100% oxygen via non-rebreather mask): pH=7.32 PaCO2=25 mmHg PaO2=250 mmHg

ICU (prior to intubation, on 100% oxygen via non-rebreather mask): pH=7.04 PaCO2=38 mmHg PaO2=71 mmHg

What echocardiogram findings are seen in submassive and massive pulmonary embolism?

- right ventricular dilation

- right ventricular hypokinesis with sparing of the right ventricular apex (McConnell sign)

- loss of inspiratory collapse on inferior vena cava

- paradoxical septal wall motion

- all of the above

Answer to Question 2

Correct answer: E

Doppler echocardiogram can be useful in supporting the diagnosis of submassive and massive pulmonary embolism, especially in the cases where a contrast chest CT cannot be performed immediately. Findings on Doppler echocardiogram demonstrate acute right ventricular pressure overload in the absence of left ventricular or mitral valve disease with or without increased pulmonary artery pressures. These findings typically occur only after >30% of the pulmonary vascular cross-sectional area is impaired and include [2]:

- right ventricular dilatation (larger than the left ventricle from the apical or subcostal view) and hypertrophy (about 6 mm; normal <4mm)

- right pulmonary artery dilatation

- paradoxical septal wall motion (interventricular septum bulges towards the left ventricle)

- loss of inspiratory collapse of inferior vena cava

- elevated pulmonary artery systolic pressure as estimated by the gradient across the tricuspid valve

- small difference in LV area during diastole and systole (low cardiac output)

- patent foramen ovale

What is the preferred hemodynamic support for hypotension in massive pulmonary embolism?

- intravenous fluids

- norepinephrine

- inotropic agents, such as isoproteronol

- vasopressin

- intra-aortic balloon counter-pulsation device (IABP)

Answer to Question 3

Correct answer: B

Norepinephrine is the preferred agent for hemodynamic support in massive pulmonary embolism with hypotension. This is based on several studies using canine models of pulmonary embolism [4-6], where isoproterenol or norepinephrine were administered for hemodynamic support in acute pulmonary embolism. Success in achieving hemodynamic stability and improvement in ventricular wall function was higher in dogs receiving infusions of norepinephrine. The effect is hypothesized to be due to increased systemic pressures, resulting in improved coronary perfusion and improved right ventricular function. In patients with less severe hypotension and more severe cardiac dysfunction, inotropic agents may be considered as an adjunct or alternative to norepinephrine [6-11]. Newer inotropic agents, such as amrinone, which act as both inotropic agent and pulmonary vasodilator have shown promise in animal studies and case reports [12,13].

A number of detrimental effects of intravenous fluids have been documented in animal studies, including decreased cardiac output and diminished right coronary artery blood flow due to increased right ventricular dilation [4-9]. In the face of diminished right coronary artery flow, worsening right ventricular ischemia can lead to diminished RV systolic function, establishing a vicious cycle of auto-aggravation. One study in humans [14], however, suggested that a 500 ml fluid load may initially improve cardiac output among patients with massive PE, although the long-term effects of fluid administration on cardiac function and hemodynamics are unclear. Most authors would agree that intravenous fluids must be used with caution in patients with massive PE [15-17].

HOSPITAL COURSE After admission to the ICU, the patient received an intravenous infusion of unfractionated heparin drip and an intravenous infusion of norepinephrine at 5 micrograms/minute for hemodynamic support. A Foley catheter was placed with urine output remaining <0.5 mL/kg/hour despite a trial of intravenous fluid resuscitation. Bedside transthoracic echocardiogram was performed and demonstrated a dilated left ventricle with depressed systolic function with an estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 15% (unchanged from baseline echo), in addition to a new finding of moderate right ventricular and right atrial dilatation with a calculated RV systolic pressure of 58mmHg (increased RV dysfunction from the prior study). There was moderate tricuspid regurgitation and a dilated inferior vena cava noted. Consideration was given to systemic thrombolysis due to the presence of persistent hypotension and end organ dysfunction, however, with a therapeutic partial thromboplastin time (PTT) on heparin, massive hemoptysis (>250 cc with >2g/dL hemoglobin drop) developed. The trachea was urgently intubated and heparin was discontinued. Interventional radiology was consulted for catheter thrombectomy and inferior vena caval (IVC) filter placement.

In cases of massive pulmonary embolism, what options remain when systemic thrombolysis cannot be performed safely?

- surgical embolectomy

- catheter-directed thrombolysis

- percutaneous embolectomy

- percutaneous thrombus fragmentation

Answer to Question 4

Correct answer: E

Surgical embolectomy: Surgical embolectomy involves transection of the main pulmonary artery via sternotomy incision with manual extraction of thromboembolism. Although in the past, peri-operative mortality was a high as 57%, some experienced centers now report peri-operative mortality of approximately 6% [33]. However, with the use of cardiopulmonary bypass and increasing surgical expertise, mortality and morbidity from surgical embolectomy can be minimized,[18,19] and may offer benefit particularly to those patients with evidence of pulmonary hypertension [18].

Historically, surgical embolectomy was the only available option for patients who fail or who have contraindications to systemic thrombolysis. It is not clear what role it will play in the future given the advent of other interventional options (listed below).

Catheter-directed thrombolysis: This technique requires placement of an intra-arterial catheter to the site of the embolus with bolus and infusion of a thrombolytic agent [20]. Catheter-directed thrombolysis usually requires concurrent intravenous unfractionated heparin administration.

Small studies, including case series and controlled trials, have evaluated the efficacy of intrapulmonary thrombolysis [21-23]. Although clinical endpoints such as mortality were not evaluated, these studies suggest equivalent or superior radiographic resolution of thrombolysis compared to systemic thrombolysis. Bleeding complication rates were low following intrapulmonary thrombolysis, suggesting that catheter-directed thrombolysis may be possible even in patients who have contraindications to systemic thrombolysis [29]. It is noteworthy, however, that these regimens also utilized systemic anticoagulation. Therefore, caution must be exercised in extrapolating the results of these small studies to patients with contraindications to systemic thrombolysis or anticoagulation. Further investigation into the safety of this technique in high risk patient populations is needed.

Percutaneous aspiration thrombectomy or fragmentation: When systemic or intrapulmonary thrombolysis and surgical embolectomy are not possible, there are a number of interventional options available that aim to rapidly relieve central obstruction and restore hemodynamic stability [20].

Greenfield embolectomy catheter [20] : This catheter (Boston Scientific/Meditech; Watertown, MA) is inserted into the site of the thrombus, and with manual suction using a large syringe retrieves the clot, which is then removed en bloc through the venotomy site or vascular sheath.

Rotatable pigtail catheter [20] : The pigtail tip of this catheter (Cook Europe; Bjaeverskov, Denmark) is rotated either by hand or by an attachable low-speed electric catheter to disrupt the intrapulmonary clot into smaller fragments which then migrate into the distal pulmonary circulation. The catheter can be advanced into peripheral pulmonary branches and manually rotated to further clot fragmentation.

Rheolytic thrombectomy catheters [20] : The Angiojet system (Possis; Minneapolis, MN) uses the Venturi effect to perform thrombectomy. This is a double lumen catheter, of which the inner smaller catheter directs a high-velocity stream of saline. The high-pressure generated by the smaller lumen catheter creates a low pressure state in the larger catheter resulting in a vortex and promotion of fragmentation and aspiration of the thrombus.

What are the most recent American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines on placement of IVC filters in pulmonary embolism?

- routine use of retrievable IVC filter in patients with PE

- use of IVC filter among patients with a contraindication to anticoagulation

- use of IVC filter among patients with recurrent PE despite adequate anticoagulation

Answer to Question 5

Correct answer: D

The official recommendation from the 7th ACCP conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy [30] is as follows: “In pulmonary embolism patients with a contraindication for, or a complication of anticoagulant therapy as well in those with recurrent thromboembolism despite adequate anticoagulation, we suggest placement of an IVC filter.”

Although this received only a Grade 2C recommendation (with low or very low evidence), there is general consensus within the pulmonary community that a patient at high risk for death due to recurrent pulmonary embolism may also benefit from placement of an IVC filter. This is based on a clinical trial of 400 patients with known deep vein thrombosis (with or without concomitant pulmonary embolism) randomized to IVC filter placement or anticoagulation alone. Concurrent placement of an IVC filter lowered the rate of new pulmonary embolism at day 12. There was no difference in PE rates at 2 years, although there was a higher incidence of DVT in the IVC filter group [31]. Although there was no difference in short-term mortality observed, patients with massive PE were not included in this study. Therefore, the use of a retrievable IVC filter [32] is a reasonable option among patients with severe hemodynamic compromise due to PE to prevent a recurrent catastrophic thromboembolism.

The patient required mechanically-assisted ventilation with a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 0.6 and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 10 cmH20 to maintain the arterial oxygen saturation >90%. Due to persistent hypotension after a trial of fluid resuscitation, norepinephrine was continued. A trial infusion of dobutamine was limited by prolonged runs of non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT). The patient’s urine output remained minimal. Interventional radiology placed an IVC filter but declined to perform a catheter thrombectomy due to the patient’s baseline depressed cardiac function.

Norepinephrine was discontinued by ICU day 6 and the patient’s oxygenation slowly improved, and mechanical ventilation was successfully discontinued on ICU day 8. Renal function improved without need for dialysis. Heparin was reintroduced before patient was discharged from the ICU without recurrence of hemoptysis. The patient recovered to her baseline status and was discharged on hospital day 39.

REFERENCES:

1. Kucher N and Goldhaber SZ. Management of massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation 2005; 112: e28-e32.

2. Goldhaber SZ. Echocardiography in the management of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136: 691–700.

3. Kasper W et al . Distinguishing between acute and subacute massive pulmonary embolism by conventional and Doppler echocardiography. Br. Heart J . 1993; 70: 352-6.

4. Molloy WD et al. Treatment of shock in a canine model of pulmonary embolism. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984; 130: 870-4.

5. Rosenberg JC et al. Isoproterenol and norepinephrine therapy for pulmonary embolism shock. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1971; 62: 144-58.

6. Imamoto et al. Treatment of canine acute pulmonary embolic shock – effects of isoproterenol and norepinephrine on hemodynamics and ventricular wall motion. Jpn Circ J 1990; 54: 1246-57.

7. Manier G and Castaing Y. Influence of cardiac output on oxygen exchange in acute pulmonary embolism. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992; 145: 130-6.

8. Ducas J et al. Pulmonary vascular pressure-flow characteristics. Effects of dopamine before and after pulmonary embolism. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992; 145: 307-12.

9. Ghigone M et al. Volume expansion versus norepinephrine in treatment of a low cardiac output complicating an acute increase in right ventricular afterload in dogs. Anesthesiology 1984; 60: 132-5.

10. Jardin F et al. Dobutamine: a hemodynamic evaluation in pulmonary embolism shock. Crit Care Med 1985; 13: 1009-12.

11. Prewitt RM. Hemodynamic management in pulmonary embolism and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. Crit Care Med 1990; 18: S61-9.

12. Wolfe MW et al. Hemodynamic effects of amrinone in a canine model of massive pulmonary embolism. Chest 1992; 102: 274-8.

13. Spence TH et al. Pulmonary embolism: improvement in hemodynamic function with amrinone therapy. South Med J 1989; 82: 1267-8.

14. Mercat A et al. Hemodynamic effects of fluid loading in acute massive pulmonary embolism. Crit Care Med 1999; 11: 339-45.

15. Piazza G and Goldhaber SZ. The acutely decompensated right ventricle. Chest 2005; 128: 1836-52.

16. Mebazaa A et al. Acute right ventricular failure – from pathophysiology to new treatments. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 185-96.

17. Layish DT and Tapson VF. Pharmacologic hemodynamic support in massive pulmonary embolism. Chest 1997; 111: 218-24.

18. Jamieson SW et al. Experience and results of 150 pulmonary thromboendarterectomy operations over a 29 month period. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993; 106: 116-27.

19. Gulba DC et al. Medical compared with surgical treatment for massive pulmonary embolism. Lancet 1994; 114: 576-7.

20. Uflacker, R. Interventional Therapy for Pulmonary Embolism . J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001; 12:147-164

21. Gonzalez-Juanatey J et al. Treatment of massive pulmonary thromboembolism with low intrapulmonary dosages of urokinase. Chest 1992; 102: 341-6.

22. Verstaete M et al. Intravenous and intrapulmonary recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation 1998; 77: 353-60.

23. McCotter CJ et al. Intrapulmonary artery infusion of urokinase for treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: a review of 26 patients with and without contraindications to systemic thrombolytic therapy. Clin Cardiol 1999; 22: 661-4.

24. Kucher, N. Catheter embolectomy for acute pulmonary embolism . Chest 2007; 132: 657-663.

25. Greenfield LJ et al. Long-term experience with transvenous catheter pulmonary embolectomy. J Vasc Surg 1993; 18: 450-8.

26. Murphy JM et al. Percutaneous catheter and guidewire fragmentation with local administration of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator as a treatment for massive pulmonary embolism. Eur Radiol 1999; 9: 959-64.

27. Stock KW et al. Massive pulmonary embolism: treatment with thrombus fragmentation and local fibrinolysis with recombinant human-tissue plasminogen activator. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1997; 20: 364-8.

28. Schmitz-Rode T et al. Fragmentation of massive pulmonary embolism using a pigtail rotation catheter. Chest 1998; 114: 1427-36.

29. Cela MC et al. Nonsurgical pulmonary embolectomy. In : Cope C, ed. Current Techniques in Interventional Radiology. Philadelphia: Current Medicine, 1994; 12: 2-8.

30. Buller HR et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004; 126(3 Suppl):401S-428S.

31. Decousus H. et al . A clinical trial of vena caval filters in the prevention of pulmonary embolism in patients with proximal deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1998; 338(7):409-15.

32. Mismetti P et al. A prospective long-term study of 220 patients with a retrievable vena cava filter for secondary prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest 2007; 131: 223-9.

33. Leacche M et al. Modern surgical treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: results in 47 consecutive patients after rapid diagnosis and aggressive surgical approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005; 129:1018-23.

The American Thoracic Society improves global health by advancing research, patient care, and public health in pulmonary disease, critical illness, and sleep disorders. Founded in 1905 to combat TB, the ATS has grown to tackle asthma, COPD, lung cancer, sepsis, acute respiratory distress, and sleep apnea, among other diseases.

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY 25 Broadway New York, NY 10004 United States of America Phone: +1 (212) 315-8600 Fax: +1 (212) 315-6498 Email: [email protected]

Privacy Statement | Term of Use | COI Conference Code of Conduct

Nursing Case Study Examples and Solutions

- Premium Academia

- August 17, 2023

- Nursing Essay Examples

NursingStudy.org is your ultimate resource for nursing case study examples and solutions. Whether you’re a nursing student, a seasoned nurse looking to enhance your skills, or a healthcare professional seeking in-depth case studies, our comprehensive collection has got you covered. Explore our extensive category of nursing case study examples and solutions to gain valuable insights, improve your critical thinking abilities, and enhance your overall clinical knowledge.

Comprehensive Nursing Case Studies

Discover a wide range of comprehensive nursing case study examples and solutions that cover various medical specialties and scenarios. These meticulously crafted case studies offer real-life patient scenarios, providing you with a deeper understanding of nursing practices and clinical decision-making processes. Each case study presents a unique set of challenges and opportunities for learning, making them an invaluable resource for nursing education and professional development.

- Nursing Case Study Analysis [10 Examples & How-To Guides] What is a case study analysis? A case study analysis is a detailed examination of a specific real-world situation or event. It is typically used in business or nursing school to help students learn how to analyze complex problems and make decisions based on limited information.

- State three nursing diagnoses using taxonomy of North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) that are appropriate, formatted correctly, prioritized, and are based on the case study. NUR 403 Week 2 Individual Assignment Case Study comprises: Resources: The case study found on p. 131 in Nursing Theory and the Case Study Grid on the Materials page of the student website Complete the Case Study Grid. List five factors of patient history that demonstrates nursing needs.

- Neuro Case Study

- Endocrine Case Study

- Anxiety & Depression Case Study

- Ethical dilemma

- A Puerto Rican Woman With Comorbid Addiction

- Tina Jones Comprehensive SOAP Note

- Insomnia 31 year old Male

- Chest Pain Assessment

Pediatric Nursing Case Studies

In this section, delve into the world of pediatric nursing through our engaging and informative case studies. Gain valuable insights into caring for infants, children, and adolescents, as you explore the complexities of pediatric healthcare. Our pediatric nursing case studies highlight common pediatric conditions, ethical dilemmas, and evidence-based interventions, enabling you to enhance your pediatric nursing skills and deliver optimal care to young patients.

- Case on Pediatrics : Part 1& 2 Solutions

- Pediatric Infant Reflux : History and Physical – Assignment 1 Solution

- Otitis Media Pediatrics Toddler – NSG 5441 Reflection Assignment/Discussion – Solution

- Pediatric Patient With Strep – NSG 5441 Reflection Assignment/Discussion

- Pediatric Urinary Tract infections (UTI) -NSG 5441 Reflection Assignment/Discussion – Solution

- Week 3 discussion-Practical Application in critical care/pediatrics

- Cough Assessmen t

Mental Health Nursing Case Study Examples

Mental health nursing plays a crucial role in promoting emotional well-being and providing care for individuals with mental health conditions. Immerse yourself in our mental health nursing case studies, which encompass a wide range of psychiatric disorders, therapeutic approaches, and psychosocial interventions. These case studies offer a holistic view of mental health nursing, equipping you with the knowledge and skills to support individuals on their journey to recovery.

- Psychiatric Nursing: Roles and Importance in Providing Mental Health Care

- Mental Health Access and Gun Violence Prevention

- Fundamentals of neurotransmission as it relates to prescribing psychotropic medications for clients with acute and chronic mental health conditions – Unit 8 Discussion – Reflection

- Unit 7 Discussion- Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Mental Health Care – Solution

- Ethical and Legal Foundations of PMHNP Care Across the Lifespan Assignment – Analyze salient ethical and legal issues in psychiatric-mental health practice | Solution

- Pathways Mental Health Case Study – Review evaluation and management documentation for a patient and perform a crosswalk of codes – Solution

- Analyze salient ethical and legal issues in psychiatric-mental health practice

- SOAP notes for Mental Health Examples

- compare and contrast two mental health theories

- Environmental Factors and Health Promotion Presentation: Accident Prevention and Safety Promotion for Parents and Caregivers of Infants

Geriatric Nursing Case Studies

As the population ages, the demand for geriatric nursing expertise continues to rise. Our geriatric nursing case studies focus on the unique challenges faced by older adults, such as chronic illnesses, cognitive impairments, and end-of-life care. By exploring these case studies, you’ll develop a deeper understanding of geriatric nursing principles, evidence-based gerontological interventions, and strategies for promoting optimal health and well-being in older adults.

- M5 Assignment: Elderly Driver

- HE003: Delivery of Services – Emmanuel is 55-year-old man Case – With Solution The Extent of Evidence-Based Data for Proposed Interventions – Sample Assignment 1 Solution

- Planning Model for Population Health Management Veterans Diagnosed with Non cancerous chronic pain – Part 1 & 2 Solutions

- PHI 413 Case Study Fetal Abnormality Essay

- Insomnia Response and Insomnia

- Analysis of a Pertinent Healthcare Issue: Short Staffing

- Paraphrenia as a Side of the Schizophrenia – Week 4 Solution

- Module 6 Pharm Assignment: Special Populations

- Public Health Nursing Roles and Responsibilities in Disaster Response – Assignment 2 Solution

- Theory Guided Practice – Assignment 2 Solution

- How can healthcare facilities establish a culture of safety – Solution