Writing A Case Study

Types Of Case Study

Understand the Types of Case Study Here

People also read

A Complete Case Study Writing Guide With Examples

Simple Case Study Format for Students to Follow

Brilliant Case Study Examples and Templates For Your Help

Case studies are effective research methods that focus on one specific case over time. This gives a detailed view that's great for learning.

Writing a case study is a very useful form of study in the educational process. With real-life examples, students can learn more effectively.

A case study also has different types and forms. As a rule of thumb, all of them require a detailed and convincing answer based on a thorough analysis.

In this blog, we are going to discuss the different types of case study research methods in detail.

So, let’s dive right in!

- 1. Understanding Case Studies

- 2. What are the Types of Case Study?

- 3. Types of Subjects of Case Study

- 4. Benefits of Case Study for Students

Understanding Case Studies

Case studies are a type of research methodology. Case study research designs examine subjects, projects, or organizations to provide an analysis based on the evidence.

It allows you to get insight into what causes any subject’s decisions and actions. This makes case studies a great way for students to develop their research skills.

A case study focuses on a single project for an extended period, which allows students to explore the topic in depth.

What are the Types of Case Study?

Multiple case studies are used for different purposes. The main purpose of case studies is to analyze problems within the boundaries of a specific organization, environment, or situation.

Many aspects of a case study such as data collection and analysis, qualitative research questions, etc. are dependent on the researcher and what the study is looking to address.

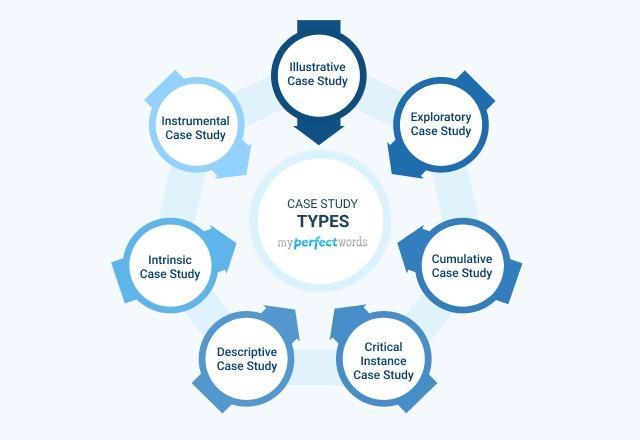

Case studies can be divided into the following categories:

Illustrative Case Study

Exploratory case study, cumulative case study, critical instance case study, descriptive case study, intrinsic case study, instrumental case study.

Let’s take a look at the detailed description of each type of case study with examples.

An illustrative case study is used to examine a familiar case to help others understand it. It is one of the main types of case studies in research methodology and is primarily descriptive.

In this type of case study, usually, one or two instances are used to explain what a situation is like.

Here is an example to help you understand it better:

Illustrative Case Study Example

An exploratory case study is usually done before a larger-scale research. These types of case studies are very popular in the social sciences like political science and primarily focus on real-life contexts and situations.

This method is useful in identifying research questions and methods for a large and complex study.

Let’s take a look at this example to help you have a better understanding:

Exploratory Case Study Example

A cumulative case study is one of the main types of case studies in qualitative research. It is used to collect information from different sources at different times.

This case study aims to summarize the past studies without spending additional cost and time on new investigations.

Let’s take a look at the example below:

Cumulative Case Study Example

Critical instances case studies are used to determine the cause and consequence of an event.

The main reason for this type of case study is to investigate one or more sources with unique interests and sometimes with no interest in general.

Take a look at this example below:

Critical Instance Case Study Example

When you have a hypothesis, you can design a descriptive study. It aims to find connections between the subject being studied and a theory.

After making these connections, the study can be concluded. The results of the descriptive case study will usually suggest how to develop a theory further.

This example can help you understand the concept better:

Descriptive Case Study Example

Intrinsic studies are more commonly used in psychology, healthcare, or social work. So, if you were looking for types of case studies in sociology, or types of case studies in social research, this is it.

The focus of intrinsic studies is on the individual. The aim of such studies is not only to understand the subject better but also their history and how they interact with their environment.

Here is an example to help you understand;

Intrinsic Case Study Example

This type of case study is mostly used in qualitative research. In an instrumental case study, the specific case is selected to provide information about the research question.

It offers a lens through which researchers can explore complex concepts, theories, or generalizations.

Take a look at the example below to have a better understanding of the concepts:

Instrumental Case Study Example

Review some case study examples to help you understand how a specific case study is conducted.

Types of Subjects of Case Study

In general, there are 5 types of subjects that case studies address. Every case study fits into the following subject categories.

- Person: This type of study focuses on one subject or individual and can use several research methods to determine the outcome.

- Group: This type of study takes into account a group of individuals. This could be a group of friends, coworkers, or family.

- Location: The main focus of this type of study is the place. It also takes into account how and why people use the place.

- Organization: This study focuses on an organization or company. This could also include the company employees or people who work in an event at the organization.

- Event: This type of study focuses on a specific event. It could be societal or cultural and examines how it affects the surroundings.

Benefits of Case Study for Students

Here's a closer look at the multitude of benefits students can have with case studies:

Real-world Application

Case studies serve as a crucial link between theory and practice. By immersing themselves in real-world scenarios, students can apply theoretical knowledge to practical situations.

Critical Thinking Skills

Analyzing case studies demands critical thinking and informed decision-making. Students cultivate the ability to evaluate information, identify key factors, and develop well-reasoned solutions – essential skills in both academic and professional contexts.

Enhanced Problem-solving Abilities

Case studies often present complex problems that require creative and strategic solutions. Engaging with these challenges refines students' problem-solving skills, encouraging them to think innovatively and develop effective approaches.

Holistic Understanding

Going beyond theoretical concepts, case studies provide a holistic view of a subject. Students gain insights into the multifaceted aspects of a situation, helping them connect the dots and understand the broader context.

Exposure to Diverse Perspectives

Case studies often encompass a variety of industries, cultures, and situations. This exposure broadens students' perspectives, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the world and the challenges faced by different entities.

So there you have it!

We have explored different types of case studies and their examples. Case studies act as the tools to understand and deal with the many challenges and opportunities around us.

Case studies are being used more and more in colleges and universities to help students understand how a hypothetical event can influence a person, group, or organization in real life.

Not everyone can handle the case study writing assignment easily. It is even scary to think that your time and work could be wasted if you don't do the case study paper right.

Our essay writing service online is here to make your academic journey easier.

Let us worry about your essay and buy case study today to ease your stress and achieve academic success.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Dr. Barbara is a highly experienced writer and author who holds a Ph.D. degree in public health from an Ivy League school. She has worked in the medical field for many years, conducting extensive research on various health topics. Her writing has been featured in several top-tier publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

What is case study research?

Last updated

8 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Suppose a company receives a spike in the number of customer complaints, or medical experts discover an outbreak of illness affecting children but are not quite sure of the reason. In both cases, carrying out a case study could be the best way to get answers.

Organization

Case studies can be carried out across different disciplines, including education, medicine, sociology, and business.

Most case studies employ qualitative methods, but quantitative methods can also be used. Researchers can then describe, compare, evaluate, and identify patterns or cause-and-effect relationships between the various variables under study. They can then use this knowledge to decide what action to take.

Another thing to note is that case studies are generally singular in their focus. This means they narrow focus to a particular area, making them highly subjective. You cannot always generalize the results of a case study and apply them to a larger population. However, they are valuable tools to illustrate a principle or develop a thesis.

Analyze case study research

Dovetail streamlines case study research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What are the different types of case study designs?

Researchers can choose from a variety of case study designs. The design they choose is dependent on what questions they need to answer, the context of the research environment, how much data they already have, and what resources are available.

Here are the common types of case study design:

Explanatory

An explanatory case study is an initial explanation of the how or why that is behind something. This design is commonly used when studying a real-life phenomenon or event. Once the organization understands the reasons behind a phenomenon, it can then make changes to enhance or eliminate the variables causing it.

Here is an example: How is co-teaching implemented in elementary schools? The title for a case study of this subject could be “Case Study of the Implementation of Co-Teaching in Elementary Schools.”

Descriptive

An illustrative or descriptive case study helps researchers shed light on an unfamiliar object or subject after a period of time. The case study provides an in-depth review of the issue at hand and adds real-world examples in the area the researcher wants the audience to understand.

The researcher makes no inferences or causal statements about the object or subject under review. This type of design is often used to understand cultural shifts.

Here is an example: How did people cope with the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami? This case study could be titled "A Case Study of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami and its Effect on the Indonesian Population."

Exploratory

Exploratory research is also called a pilot case study. It is usually the first step within a larger research project, often relying on questionnaires and surveys . Researchers use exploratory research to help narrow down their focus, define parameters, draft a specific research question , and/or identify variables in a larger study. This research design usually covers a wider area than others, and focuses on the ‘what’ and ‘who’ of a topic.

Here is an example: How do nutrition and socialization in early childhood affect learning in children? The title of the exploratory study may be “Case Study of the Effects of Nutrition and Socialization on Learning in Early Childhood.”

An intrinsic case study is specifically designed to look at a unique and special phenomenon. At the start of the study, the researcher defines the phenomenon and the uniqueness that differentiates it from others.

In this case, researchers do not attempt to generalize, compare, or challenge the existing assumptions. Instead, they explore the unique variables to enhance understanding. Here is an example: “Case Study of Volcanic Lightning.”

This design can also be identified as a cumulative case study. It uses information from past studies or observations of groups of people in certain settings as the foundation of the new study. Given that it takes multiple areas into account, it allows for greater generalization than a single case study.

The researchers also get an in-depth look at a particular subject from different viewpoints. Here is an example: “Case Study of how PTSD affected Vietnam and Gulf War Veterans Differently Due to Advances in Military Technology.”

Critical instance

A critical case study incorporates both explanatory and intrinsic study designs. It does not have predetermined purposes beyond an investigation of the said subject. It can be used for a deeper explanation of the cause-and-effect relationship. It can also be used to question a common assumption or myth.

The findings can then be used further to generalize whether they would also apply in a different environment. Here is an example: “What Effect Does Prolonged Use of Social Media Have on the Mind of American Youth?”

Instrumental

Instrumental research attempts to achieve goals beyond understanding the object at hand. Researchers explore a larger subject through different, separate studies and use the findings to understand its relationship to another subject. This type of design also provides insight into an issue or helps refine a theory.

For example, you may want to determine if violent behavior in children predisposes them to crime later in life. The focus is on the relationship between children and violent behavior, and why certain children do become violent. Here is an example: “Violence Breeds Violence: Childhood Exposure and Participation in Adult Crime.”

Evaluation case study design is employed to research the effects of a program, policy, or intervention, and assess its effectiveness and impact on future decision-making.

For example, you might want to see whether children learn times tables quicker through an educational game on their iPad versus a more teacher-led intervention. Here is an example: “An Investigation of the Impact of an iPad Multiplication Game for Primary School Children.”

- When do you use case studies?

Case studies are ideal when you want to gain a contextual, concrete, or in-depth understanding of a particular subject. It helps you understand the characteristics, implications, and meanings of the subject.

They are also an excellent choice for those writing a thesis or dissertation, as they help keep the project focused on a particular area when resources or time may be too limited to cover a wider one. You may have to conduct several case studies to explore different aspects of the subject in question and understand the problem.

- What are the steps to follow when conducting a case study?

1. Select a case

Once you identify the problem at hand and come up with questions, identify the case you will focus on. The study can provide insights into the subject at hand, challenge existing assumptions, propose a course of action, and/or open up new areas for further research.

2. Create a theoretical framework

While you will be focusing on a specific detail, the case study design you choose should be linked to existing knowledge on the topic. This prevents it from becoming an isolated description and allows for enhancing the existing information.

It may expand the current theory by bringing up new ideas or concepts, challenge established assumptions, or exemplify a theory by exploring how it answers the problem at hand. A theoretical framework starts with a literature review of the sources relevant to the topic in focus. This helps in identifying key concepts to guide analysis and interpretation.

3. Collect the data

Case studies are frequently supplemented with qualitative data such as observations, interviews, and a review of both primary and secondary sources such as official records, news articles, and photographs. There may also be quantitative data —this data assists in understanding the case thoroughly.

4. Analyze your case

The results of the research depend on the research design. Most case studies are structured with chapters or topic headings for easy explanation and presentation. Others may be written as narratives to allow researchers to explore various angles of the topic and analyze its meanings and implications.

In all areas, always give a detailed contextual understanding of the case and connect it to the existing theory and literature before discussing how it fits into your problem area.

- What are some case study examples?

What are the best approaches for introducing our product into the Kenyan market?

How does the change in marketing strategy aid in increasing the sales volumes of product Y?

How can teachers enhance student participation in classrooms?

How does poverty affect literacy levels in children?

Case study topics

Case study of product marketing strategies in the Kenyan market

Case study of the effects of a marketing strategy change on product Y sales volumes

Case study of X school teachers that encourage active student participation in the classroom

Case study of the effects of poverty on literacy levels in children

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Guide to case studies

What is a case study.

A case study is an in depth focussed study of a person, group, or situation that has been studied over time within its real-life context.

There are different types of case study:

- Illustrative case studies describe an unfamiliar situation in order to help people understand it.

- Critical instance case studies focus on a unique case, without a generalised purpose.

- Exploratory case studies are preliminary projects to help guide a future, larger-scale project. They aim to identify research questions and possible research approaches.

We are often looking to develop patient stories as case studies and these will use qualitative methods such as interviews to find specific details and descriptions of how your subject is affected.

Patient stories are illustrative or critical instance case studies. For example, an illustrative case study might focus on a patient with an eating disorder to provide a subjective view to better help trainee nutritionists understand the illness. A critical instance case study might focus on a patient with a very rare or uniquely complex condition or how a single patient is affected by an injury.

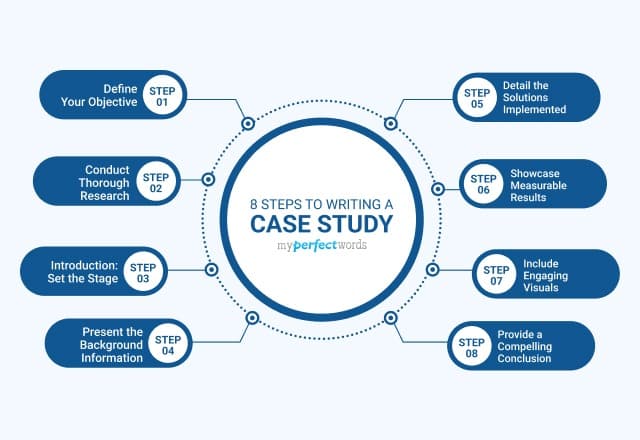

How do you do a case study?

1. get prepared.

- Be very clear about the purpose of the case study, why you are doing it and what it will be used for?

- Think about the questions you want to answer? What are your research or evaluation questions?

- Determine what kind of case study will best suit your needs? Illustrative, Critical Instance or Exploratory?

- Define the subject of study – is it an individual, a small group of people, or a specific situation?

- Determine if you need ethical approval to conduct this case study – you may be asked to prove that the case study will do no harm to its participant(s).

2. Get designing!

- Finalise your research or evaluation questions – i.e. what you want to know at the end of the study. Limit these to a manageable number – no more than 4 or 5.

- Think about where you will find the information you need to answer your questions. Interviewing research subjects and/ or observing will likely be the central methods of your case study, but do you need to look to additional data sources as well? For example, desk research or evidence/literature reviewing, interviewing experts, other fieldwork and so on.

- Create a plan outlining how you will gather the information you need to answer your research or evaluation questions. Include a timeframe and be clear that you have the resources and equipment to carry out the work. Depending on the nature of the case study or the topic being studied a case study may require several meetings/interviews over a period of many months, or it might need just a one off interview. What does yours need?

- Decide on the exact subject of the study. Is this a specific person or a small group of people? If yes, plan how you will get in touch with them and invite them to take part in the case study. How flexible can you be in terms of time and travel? Does this limit your access to potential participants?

- Design interview questions that are open and will enable the participant to provide in-depth answers. Avoid questions that can be answered with a single yes or no and make sure the questions are flexible and allow the participant to talk openly and freely.

3. Get recruiting!

- You may have a specific individual in mind, or specific criteria. You will need to invite people to participate and make very clear that they are able to withdraw at any point.

- You will need consent from the participants. Make sure the purpose of the case study, why you are doing it and what it will be used, the methods and time frames are extremely clear to the potential participants. You will need written consent that demonstrates that the participant understands this. Additionally, if you intend to digitally record an interview or take notes, make sure you have permission from the participants’ first.

- If your central method is observation, this will be open observation – the participant must be aware of your presence and agreed to it – you are not allowed to observe without the participants’ permission!

4. Get conducting!

- Interviewing – Agree a mutually suitable time and venue for the case study interview. This may be a one off or the first of many over several months. Make sure the participant is in an environment they are comfortable and able to talk in. Equally important, however is that the environment is safe for you and is conducive to conducting a case study interview – i.e. If it is a private space, are you safe? If it is a public space make sure it is not too noisy or likely to be affected by interruptions.

- Decide what is the best method of recording the interview information – digital recording is less intrusive and you can engage better in the conversation, than if you attempt to just take notes. Taking notes can mean that your concentration is focused on the writing rather than the listening and you can miss vital points. It can also be off-putting for the participant if there is no eye contact because you are scribing throughout the conversation. However, some participants will not like to be digitally recorded – so it is best to discuss this with them first. If you are digitally recording always test the equipment first. Even if you are digitally recording you will still need to take notes on key points, or things that you would like to investigate further, questions that arise or points at which you don’t want to interrupt the conversation or anything that will not be captured by the recording, such as body language or other observations.

- Depending on the total length of your case study, you might hold a one off interview, interview weekly, once every month or two, or just once or twice a year. Begin with the interview questions you prepared in the preparation and design phases, then iterate to dig deeper into the topics. Ask about experience and meaning — ask the participant what it’s like to go through the experience you’re studying and what the experience means to them. Later interviews are an opportunity to ask questions that fill gaps in your knowledge, or that are particularly relevant to the development of the case study or in answering your questions.

- Observing – recording observation can be done manually – i.e. taking notes – or digitally via a camcorder or similar. It is important to capture detail about the subject/participant and their interactions with others and the environment, their behaviour and other context an detail that is relevant to your questions.

5. Get analysing!

- Write up your notes or transcribe (Interviews), make notes (video) from your digital recording. Remember that if you are transcribing it is important to include pauses, laughter and other descriptive sounds and commentary on tone and intonation to better convey the story. Include the contextual information / the external environment and other observations that are important. Such as when and where the interview took place (you will not necessarily make this public) and any issues that arose such as interruptions that affected the interview or if there were multiple interviews anything of significance that happened in the periods between interviews.

- Thematically code (look for themes) and look for key parts of the interviews that will answer your original questions. Also be very aware that the may be new or unexpected information that has come through the process that is very important or interesting.

- Arrange the notes or transcriptions from the interviews and, or observations into a case study. It is not likely that you will be able to use the transcriptions without reorganising them, but if you are rewriting the story in your own words, be careful not to lose the meaning and language that reflects the participant.

6. Get sign off!

- Once you have drafted your case study make sure the participant(s) have sight of it and an opportunity to say whether you have captured their story and are representing it/them as they would like.

7. Get disseminating!

- More information about disseminating evaluations and case studies can be found on the Evaluation Toolkit site .

- Remember case studies are not designed for large group studies or statistical analysis and do not aim to answer a research question definitively.

- Do background/context research where possible.

- Establishing trust with participants is crucial and can result in less inhibited behaviour. Observing people in their home, workplaces, or other “natural” environments may be more effective than bringing them to a laboratory or office.

- Be aware that if you are observing it is likely that because subjects know they are being studied, their behaviour will change.

- Take notes -Extensive notes during observation will be vital.

- Take notes even if you are digitally recoding an interview to capture your own thinking, points to follow up on or observations.

- In some case studies, it may be appropriate to ask the participant to record experiences in a diary – especially if there are periods between your interviews or observations that you wish to capture data on.

- Stay rigorous. A case study may feel less data-driven than a medical trial or a scientific experiment, but attention to rigor and valid methodology remains vital.

- When reviewing your notes, discard possible conclusions that do not have detailed observation or evidence backing them up.

- A case study might reveal new and unexpected results, and lead to research taking new directions.

- A case study cannot be generalised to fit a whole population.

- Since you aren’t conducting a statistical analysis, you do not need to recruit a diverse cross-section of society. You should be aware of any biases in your small sample, and make them clear in your report, but they do not invalidate your research.

- Useful resource: ‘Case Study Research: Design and Methods’, Robert K Yin, SAGE publications 2013.

Case studies

Find inspiration for your own evaluation with these real life examples

Guidance from a range of organisations for in-depth advice

Services and support

Knowledgeable organisations who may be able to help you

Training resources

Want to learn more? Our training resources are a good place to start

The Evaluation and Evidence toolkits go hand in hand. Using and generating evidence to inform decision making is vital to improving services and people’s lives.

The toolkits have been developed by the NHS Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire Integrated Care Board (BNSSG ICB), the National Institute for Health and Care Research Applied Research Collaboration West (NIHR ARC West) and Health Innovation West of England .

We use cookies to give you the best experience of our website. By browsing you agree to our use of cookies.

Types of Case Studies

There are several different types of case studies, as well as several types of subjects of case studies. We will investigate each type in this article.

Different Types of Case Studies

There are several types of case studies, each differing from each other based on the hypothesis and/or thesis to be proved. It is also possible for types of case studies to overlap each other.

Each of the following types of cases can be used in any field or discipline. Whether it is psychology, business or the arts, the type of case study can apply to any field.

Explanatory

The explanatory case study focuses on an explanation for a question or a phenomenon. Basically put, an explanatory case study is 1 + 1 = 2. The results are not up for interpretation.

A case study with a person or group would not be explanatory, as with humans, there will always be variables. There are always small variances that cannot be explained.

However, event case studies can be explanatory. For example, let's say a certain automobile has a series of crashes that are caused by faulty brakes. All of the crashes are a result of brakes not being effective on icy roads.

What kind of case study is explanatory? Think of an example of an explanatory case study that could be done today

When developing the case study, the researcher will explain the crash, and the detailed causes of the brake failure. They will investigate what actions caused the brakes to fail, and what actions could have been taken to prevent the failure.

Other car companies could then use this case study to better understand what makes brakes fail. When designing safer products, looking to past failures is an excellent way to ensure similar mistakes are not made.

The same can be said for other safety issues in cars. There was a time when cars did not have seatbelts. The process to get seatbelts required in all cars started with a case study! The same can be said about airbags and collapsible steering columns. They all began with a case study that lead to larger research, and eventual change.

Exploratory

An exploratory case study is usually the precursor to a formal, large-scale research project. The case study's goal is to prove that further investigation is necessary.

For example, an exploratory case study could be done on veterans coming home from active combat. Researchers are aware that these vets have PTSD, and are aware that the actions of war are what cause PTSD. Beyond that, they do not know if certain wartime activities are more likely to contribute to PTSD than others.

For an exploratory case study, the researcher could develop a study that certain war events are more likely to cause PTSD. Once that is demonstrated, a large-scale research project could be done to determine which events are most likely to cause PTSD.

Exploratory case studies are very popular in psychology and the social sciences. Psychologists are always looking for better ways to treat their patients, and exploratory studies allow them to research new ideas or theories.

Multiple-Case Studies or Collective Studies

Multiple case or collective studies use information from different studies to formulate the case for a new study. The use of past studies allows additional information without needing to spend more time and money on additional studies.

Using the PTSD issue again is an excellent example of a collective study. When studying what contributes most to wartime PTSD, a researcher could use case studies from different war. For instance, studies about PTSD in WW2 vets, Persian Gulf War vets, and Vietnam vets could provide an excellent sampling of which wartime activities are most likely to cause PTSD.

If a multiple case study on vets was done with vets from the Vietnam War, the Persian Gulf War, and the Iraq War, and it was determined the vets from Vietnam had much less PTSD, what could be inferred?

Furthermore, this type of study could uncover differences as well. For example, a researcher might find that veterans who serve in the Middle East are more likely to suffer a certain type of ailment. Or perhaps, that veterans who served with large platoons were more likely to suffer from PTSD than veterans who served in smaller platoons.

An intrinsic case study is the study of a case wherein the subject itself is the primary interest. The "Genie" case is an example of this. The study wasn't so much about psychology, but about Genie herself, and how her experiences shaped who she was.

Genie is the topic. Genie is what the researchers are interested in, and what their readers will be most interested in. When the researchers started the study, they didn't know what they would find.

They asked the question…"If a child is never introduced to language during the crucial first years of life, can they acquire language skills when they are older?" When they met Genie, they didn't know the answer to that question.

Instrumental

An instrumental case study uses a case to gain insights into a phenomenon. For example, a researcher interested in child obesity rates might set up a study with middle school students and an exercise program. In this case, the children and the exercise program are not the focus. The focus is learning the relationship between children and exercise, and why certain children become obese.

What is an example of an instrumental case study?

Focus on the results, not the topic!

Types of Subjects of Case Studies

There are generally five different types of case studies, and the subjects that they address. Every case study, whether explanatory or exploratory, or intrinsic or instrumental, fits into one of these five groups. These are:

Person – This type of study focuses on one particular individual. This case study would use several types of research to determine an outcome.

The best example of a person case is the "Genie" case study. Again, "Genie" was a 13-year-old girl who was discovered by social services in Los Angeles in 1970. Her father believed her to be mentally retarded, and therefore locked her in a room without any kind of stimulation. She was never nourished or cared for in any way. If she made a noise, she was beaten.

When "Genie" was discovered, child development specialists wanted to learn as much as possible about how her experiences contributed to her physical, emotional and mental health. They also wanted to learn about her language skills. She had no form of language when she was found, she only grunted. The study would determine whether or not she could learn language skills at the age of 13.

Since Genie was placed in a children's hospital, many different clinicians could observe her. In addition, researchers were able to interview the few people who did have contact with Genie and would be able to gather whatever background information was available.

This case study is still one of the most valuable in all of child development. Since it would be impossible to conduct this type of research with a healthy child, the information garnered from Genie's case is invaluable.

Group – This type of study focuses on a group of people. This could be a family, a group or friends, or even coworkers.

An example of this type of case study would be the uncontacted tribes of Indians in the Peruvian and Brazilian rainforest. These tribes have never had any modern contact. Therefore, there is a great interest to study them.

Scientists would be interested in just about every facet of their lives. How do they cook, how do they make clothing, how do they make tools and weapons. Also, doing psychological and emotional research would be interesting. However, because so few of these tribes exist, no one is contacting them for research. For now, all research is done observationally.

If a researcher wanted to study uncontacted Indian tribes, and could only observe the subjects, what type of observations should be made?

Location – This type of study focuses on a place, and how and why people use the place.

For example, many case studies have been done about Siberia, and the people who live there. Siberia is a cold and barren place in northern Russia, and it is considered the most difficult place to live in the world. Studying the location, and it's weather and people can help other people learn how to live with extreme weather and isolation.

Location studies can also be done on locations that are facing some kind of change. For example, a case study could be done on Alaska, and whether the state is seeing the effects of climate change.

Another type of study that could be done in Alaska is how the environment changes as population increases. Geographers and those interested in population growth often do these case studies.

Organization/Company – This type of study focuses on a business or an organization. This could include the people who work for the company, or an event that occurred at the organization.

An excellent example of this type of case study is Enron. Enron was one of the largest energy company's in the United States, when it was discovered that executives at the company were fraudulently reporting the company's accounting numbers.

Once the fraud was uncovered, investigators discovered willful and systematic corruption that caused the collapse of Enron, as well as their financial auditors, Arthur Andersen. The fraud was so severe that the top executives of the company were sentenced to prison.

This type of case study is used by accountants, auditors, financiers, as well as business students, in order to learn how such a large company could get away with committing such a serious case of corporate fraud for as long as they did. It can also be looked at from a psychological standpoint, as it is interesting to learn why the executives took the large risks that they took.

Most company or organization case studies are done for business purposes. In fact, in many business schools, such as Harvard Business School, students learn by the case method, which is the study of case studies. They learn how to solve business problems by studying the cases of businesses that either survived the same problem, or one that didn't survive the problem.

Event – This type of study focuses on an event, whether cultural or societal, and how it affects those that are affected by it. An example would be the Tylenol cyanide scandal. This event affected Johnson & Johnson, the parent company, as well as the public at large.

The case study would detail the events of the scandal, and more specifically, what management at Johnson & Johnson did to correct the problem. To this day, when a company experiences a large public relations scandal, they look to the Tylenol case study to learn how they managed to survive the scandal.

A very popular topic for case studies was the events of September 11 th . There were studies in almost all of the different types of research studies.

Obviously the event itself was a very popular topic. It was important to learn what lead up to the event, and how best to proven it from happening in the future. These studies are not only important to the U.S. government, but to other governments hoping to prevent terrorism in their countries.

Planning A Case Study

You have decided that you want to research and write a case study. Now what? In this section you will learn how to plan and organize a research case study.

Selecting a Case

The first step is to choose the subject, topic or case. You will want to choose a topic that is interesting to you, and a topic that would be of interest to your potential audience. Ideally you have a passion for the topic, as then you will better understand the issues surrounding the topic, and which resources would be most successful in the study.

You also must choose a topic that would be of interest to a large number of people. You want your case study to reach as large an audience as possible, and a topic that is of interest to just a few people will not have a very large reach. One of the goals of a case study is to reach as many people as possible.

Who is your audience?

Are you trying to reach the layperson? Or are you trying to reach other professionals in your field? Your audience will help determine the topic you choose.

If you are writing a case study that is looking for ways to lower rates of child obesity, who is your audience?

If you are writing a psychology case study, you must consider whether your audience will have the intellectual skills to understand the information in the case. Does your audience know the vocabulary of psychology? Do they understand the processes and structure of the field?

You want your audience to have as much general knowledge as possible. When it comes time to write the case study, you may have to spend some time defining and explaining terms that might be unfamiliar to the audience.

Lastly, when selecting a topic you do not want to choose a topic that is very old. Current topics are always the most interesting, so if your topic is more than 5-10 years old, you might want to consider a newer topic. If you choose an older topic, you must ask yourself what new and valuable information do you bring to the older topic, and is it relevant and necessary.

Determine Research Goals

What type of case study do you plan to do?

An illustrative case study will examine an unfamiliar case in order to help others understand it. For example, a case study of a veteran with PTSD can be used to help new therapists better understand what veterans experience.

An exploratory case study is a preliminary project that will be the precursor to a larger study in the future. For example, a case study could be done challenging the efficacy of different therapy methods for vets with PTSD. Once the study is complete, a larger study could be done on whichever method was most effective.

A critical instance case focuses on a unique case that doesn't have a predetermined purpose. For example, a vet with an incredibly severe case of PTSD could be studied to find ways to treat his condition.

Ethics are a large part of the case study process, and most case studies require ethical approval. This approval usually comes from the institution or department the researcher works for. Many universities and research institutions have ethics oversight departments. They will require you to prove that you will not harm your study subjects or participants.

This should be done even if the case study is on an older subject. Sometimes publishing new studies can cause harm to the original participants. Regardless of your personal feelings, it is essential the project is brought to the ethics department to ensure your project can proceed safely.

Developing the Case Study

Once you have your topic, it is time to start planning and developing the study. This process will be different depending on what type of case study you are planning to do. For thissection, we will assume a psychological case study, as most case studies are based on the psychological model.

Once you have the topic, it is time to ask yourself some questions. What question do you want to answer with the study?

For example, a researcher is considering a case study about PTSD in veterans. The topic is PTSD in veterans. What questions could be asked?

Do veterans from Middle Eastern wars suffer greater instances of PTSD?

Do younger soldiers have higher instances of PTSD?

Does the length of the tour effect the severity of PTSD?

Each of these questions is a viable question, and finding the answers, or the possible answers, would be helpful for both psychologists and veterans who suffer from PTSD.

Research Notebook

1. What is the background of the case study? Who requested the study to be done and why? What industry is the study in, and where will the study take place?

2. What is the problem that needs a solution? What is the situation, and what are the risks?

3. What questions are required to analyze the problem? What questions might the reader of the study have? What questions might colleagues have?

4. What tools are required to analyze the problem? Is data analysis necessary?

5. What is your current knowledge about the problem or situation? How much background information do you need to procure? How will you obtain this background info?

6. What other information do you need to know to successfully complete the study?