Violence against women must stop; five stories of strength and survival

Facebook Twitter Print Email

Conflicts, humanitarian crises and increasing climate-related disasters have led to higher levels of violence against women and girls (VAWG), which has only intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing into sharp focus the urgent need to stem the scourge.

Globally, nearly one-in-three women have experienced violence, with crises driving the numbers even higher.

Gender-based violence (GBV), the most pervasive violation of human rights, is neither natural, nor inevitable, and must be prevented.

Marking the 16 Days of Activism to combat violence against women and girls, UN Women is showcasing the voices of five survivors, each of whose names has been changed to protect their identity. Be forewarned that each character sketch includes descriptions of gender-based violence.

‘Convinced’ she would be killed

From the Argentine province of Chaco, 48-year-old mother of seven, Diana suffered for 28 years before finally deciding to separate from her abusive partner.

“I wasn't afraid that he would beat me, I was convinced that he would kill me,” she said.

At first, she hesitated to file a police complaint for fear of how he might react, but as she learned more about the services provided by a local shelter, she realized that she could escape her tormentor. She also decided to press charges.

Living with an abusive father, her children also suffered psychological stress and economic hardship.

Leaving was not easy, but with the support of a social workers, a local shelter and a safe space to recover, Diana got a job as an administrative assistant in a municipal office.

Accelerate gender equality

- Violence against women and girls is preventable.

- Comprehensive strategies are needed to tackle root causes, transform harmful social norms, provide services for survivors and end impunity.

- Evidence shows that strong, autonomous women’s rights movements are critical to thwarting and eliminating VAWG.

- The Generation Equality Forum needs support to stem the VAWG violence.

“I admit that it was difficult, but with the [mental health] support, legal aid and skills training, I healed a lot,” she explained.

Essential services for survivors of domestic violence are a lifeline.

“I no longer feel like a prisoner, cornered, or betrayed. There are so many things one goes through as a victim, including the psychological [persecution] but now I know that I can accomplish whatever I set my mind to”.

Diana is among 199 women survivors housed at a shelter affiliated with the Inter-American Shelter Network, supported by UN Women through the Spotlight Initiative in Latin America. The shelter has also provided psychosocial support and legal assistance to more than 1,057 women since 2017.

Diana’s full story is here .

Survivor now ‘excited about what lies ahead’

Meanwhile, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept through Bangladesh, triggering a VAWG surge, many shelters and essential services shut down

Romela had been married to a cruel, torturous man.

“When I was pregnant, he punched me so hard I ended up losing my baby...I wanted to end my life”, she said.

She finally escaped when her brother took her to the Tarango women’s shelter, which in partnership with UN Women, was able to expand its integrated programme to provide safe temporary accommodations, legal and medical services, and vocational training to abused women who were looking for a fresh start.

Living in an abusive relationship often erodes women’s choices, self-esteem and potential. Romela had found a place where she could live safely with her 4-year-old daughter.

Opening a new chapter in her life, she reflected, “other people always told me how to dress, where to go, and how to live my life. Now, I know these choices rest in my hands”.

“ I feel confident, my life is more enjoyable ,” said the emancipated woman.

Tarango houses 30–35 survivors at any given time and delivers 24/7 services that help them recover from trauma, regain their dignity, learn new skills, and get job placement and a two-month cash grant to build their economic resilience.

“Our job is to make women feel safe and empowered, and to treat them with the utmost respect and empathy,” said Programme Coordinator Nazlee Nipa.

Click here for more on her story.

Uphill battle with in-laws

Goretti returned to western Kenya in 2001 to bury her husband and, as dictated by local culture, remained in the family’s homestead.

“But they wouldn’t give me food. Everything I came with from Nairobi – clothes, household items – was taken from me and divided between the family,” she recounted.

For nearly 20 years after her husband’s death, Goretti was trapped in a life of abuse until her in-laws they beat her so badly that she was hospitalized and unable to work.

Afraid to go to law enforcement, Goretti instead reached out to a local human rights defender, who helped her get medical attention and report the case to the local authorities.

They wouldn’t give me food. Everything...was taken from me and divided between the family – Survivor

However, she quickly discovered that her in-laws had already forged with the police an agreement in her name to withdraw the case.

“But I cannot even write”, Goretti said.

Human rights defenders in Kenya are often the first responders to violations, including GBV. Since 2019, UN Women and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights ( OHCHR ) have been supporting grass-roots organizations that provide legal training and capacity-building to better assist survivors.

In addition to reporting the issue to local police and the courts, human rights defender Caren Omanga, who was trained by one of these organizations, also contacted the local elders.

“I was almost arrested when confronting the officer-in-charge”, Ms. Omanga explained. But knowing that the community would be against Goretti, she started “the alternative dispute-resolution process, while pushing the case to court”.

Finally, with her case settled out of court, Goretti received an agreement granting her the property and land title that she had lost in her marriage dowry, and the perpetrators were forced to pay fines to avoid prison.

“It is like beginning a new life after 20 years, and my son is feeling more secure… I’m thinking of planting some trees to safeguard the plot and building a poultry house”, she said.

Read Goretti’s story in its entirety here.

Raising consciousness

In Moldova, sexual harassment and violence are taboo topics and, fearing blame or stigmatization, victims rarely report incidents.

At age 14, Milena was raped by her boyfriend in Chisinau. She was unaware that her violation was a sexual assault and continued to see her abuser for another six months before breaking up. Then she tried to forget it.

“This memory was blocked, as if nothing happened”, until two years later, upon seeing an Instagram video that triggered flashbacks of her own assault, she said.

Almost one-in-five men in Moldova have sexually abused a girl or a woman, including in romantic relationships, according to 2019 research co-published by UN Women.

Determined to understand what had happened to her, Milena learned more about sexual harassment and abuse, and later began raising awareness in her community.

Last year, she joined a UN Women youth mentorship programme, where she was trained on gender equality and human rights and learned to identify abuse and challenge sexist comments and harassment.

Milena went on to develop a self-help guide for sexual violence survivors , which, informed by survivors aged 12 – 21, offers practical guidance to seek help, report abuse, and access trauma recovery resources.

Against the backdrop of cultural victim-blaming, which prevents those who need it from getting help, the mentoring programme focuses on feminist values and diversity, and addresses the root causes of the gender inequalities and stereotypes that perpetuate GBV and discrimination.

“The programme has shown that youth activism and engagement is key to eliminating gender inequalities in our societies”, explained Dominika Stojanoska, UN Women Country Representative in Moldova.

Read more about Milena here .

Support survivors, break the cycle of violence

A 2019 national survey revealed that only three-out-of-100 sexual violence survivors in Morocco report incidents to the police as they fear being shamed or blamed and lack trust in the justice system.

Layla began a relationship with the head of a company she worked for. He told her he loved her, and she trusted him.

“But he hit me whenever I disagreed with him. I endured everything, from sexual violence to emotional abuse…he made me believe that I stood no chance against him”, she said.

Pregnant, unmarried and lonely, Layla finally went to the police.

To her great relief, a female police officer met her, and said that there was a solution.

“I will never forget that. It has become my motto in life. Her words encouraged me to tell her the whole story. She listened to me with great care and attention”, continued Layla.

She was referred to a local shelter for single mothers where she got a second chance.

Two years ago, she gave birth to a daughter, and more recently completed her Bachelor’s Degree in mathematics.

“I was studying while taking care of my baby at the single mother’s shelter”, she said, holding her daughter’s hand.

UN Women maintains that building trust and confidence in the police is an integral part of crime prevention and community safety.

When professionally trained police handle GBV cases, survivors are more likely to report abuse and seek justice, health and psychosocial services that help break the cycle of violence while sending a clear message that it is a punishable crime.

Over the past few years, the General Directorate of National Security, supported by UN Women, has restructured the national police force to better support women survivors and prevent VAWG.

Today, all 440 district police stations have dedicated personnel who refer women survivors to the nearest specialized unit.

“It takes a lot of determination and courage for women to ask the police for support”, said Saliha Najeh, Police Chief at Casablanca Police Unit for Women Victims of Violence, who, after specialized training through the UN Women programme, now trains her police officers to use a survivor-centred approach in GBV cases.

As of 2021, 30 senior police officers and heads of units have been trained through the programme.

“Our role is to give survivors all the time they need to feel safe and comfortable, and for them to trust us enough to tell their story”, she said.

Prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, Morocco has also expanded channels for survivors to report and access justice remotely through a 24-hour toll-free helpline, an electronic complaints mechanism, and online court sessions.

Click here for the full story.

These stories were originally published by UN Women.

- violence against women

- gender-based violence

SAFETY ALERT: If you are in danger, please use a safer computer and consider calling 911. The National Domestic Violence Hotline at 1-800-799-7233 / TTY 1-800-787-3224 or the StrongHearts Native Helpline at 1−844-762-8483 (call or text) are available to assist you.

Please review these safety tips .

Research & Evidence

NRCDV works to strengthen researcher/practitioner collaborations that advance the field’s knowledge of, access to, and input in research that informs policy and practice at all levels. We also identify and develop guidance and tools to help domestic violence programs and coalitions better evaluate their work, including by using participatory action research approaches that directly tap the diverse expertise of a community to frame and guide evaluation efforts.

Safety & Privacy in a Digital World

Immigrant Survivors of Domestic Violence

Teen Dating Violence

Housing and Domestic Violence

Domestic Violence in LGBTQ Communities

Trans and Non-Binary Survivors

The Difference Between Surviving & Not Surviving

Earned Income Tax Credit & Other Tax Credits

For an extensive list of research & evidence materials check out the research & statistics section on VAWnet

The Domestic Violence Evidence Project (DVEP) is a multi-faceted, multi-year and highly collaborative effort designed to assist state coalitions, local domestic violence programs, researchers, and other allied individuals and organizations better respond to the growing emphasis on identifying and integrating evidence-based practice into their work. DVEP brings together research, evaluation, practice and theory to inform critical thinking and enhance the field's knowledge to better serve survivors and their families.

The Community Based Participatory Research Toolkit (CBPR) is for researchers and practitioners across disciplines and social locations who are working in academic, policy, community, or practice-based settings. In particular, the toolkit provides support to emerging researchers as they consider whether and how to take a CBPR approach and what it might mean in the context of their professional roles and settings. Domestic violence advocates will also find useful information on the CBPR approach and how it can help answer important questions about your work.

For over two decades, the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence has operated VAWnet , an online library focused on violence against women and other forms of gender-based violence. VAWnet.org has long been identified as an unparalleled, comprehensive, go-to source of information and resources for anti-violence advocates, human service professionals, educators, faith leaders, and others interested in ending domestic and sexual violence.

Safe Housing Partnerships , the website of the Domestic Violence and Housing Technical Assistance Consortium , includes the latest research and evidence on the intersection of domestic and sexual violence, housing, and homelessness. You can also find new research exploring different aspects of efforts to expand housing options for domestic and sexual violence survivors, including the use of flexible funding approaches, DV Housing First and rapid rehousing, DV Transitional Housing, and mobile advocacy.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10 Working with Survivors of Gender-Based Violence

Dessie clark, ph.d., & joshua brown, lcsw, the purpose of this case study is to explore the process and outcomes of a collaboration between researchers and a community-based organization serving survivors of gender-based violence, fort bend women’s center., the big picture.

Gender-based violence is a rapidly growing social concern and even more so as the world continues to grapple with the effects of Covid-19. The implications of gender-based violence are too numerous to name here, but there are several special considerations for this population, including attrition (this population can be more transient than others), high caseload and rate of burnout for front line workers, as well as the physical and psychological effects of abuse, including traumatic brain injury (TBI) and initial reluctance to trust others. Further, gaps in existing work with survivors of gender-based violence include a mismatch between the expectations of researchers and the realities of those who are on the frontlines in these organizations and the people that they serve. The purpose of this case study is to explore the process and outcomes of a collaboration between researchers and a community-based organization serving survivors of gender-based violence, Fort Bend Women’s Center . We propose that focusing attention on communication, trust, buy-in, and burnout are critical for collaborations between researchers and community organizations that serve survivors of gender-based violence.

It is important to understand that collaborations, such as the one detailed in this case study, do not begin by happenstance. Strong collaborations can take time to develop. For this reason, the authors find it important to explain the origins of this project. In 2012, Abeer Monem (now former) Chief Programs Officer of the Fort Bend Women’s Center (FBWC) began to explore reasons why a portion of the agency’s Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) survivors were struggling to progress toward self-sufficiency, despite the agency’s existing program offerings such as case management and counseling. As the agency explored the reasons behind the lack of progress, it became clear that one of the main reasons could be potential traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the survivor population. Eager to confirm their suspicion, agency personnel embarked on the discovery and research phases of the intervention’s lifecycle.

It was first deemed necessary to determine if agency survivors indeed exhibited a likelihood of traumatic brain injury. FBWC personnel began administering the HELPS Screening Tool for Traumatic Brain Injury (HELPS) (M. Picard, D. Scarisbrick, R. Paluck, International Center for the Disabled, TBI-NET, and U.S. Department of Education, Rehabilitation Services Administration). The HELPS Screening Tool is a simple tool designed to be given by professionals who are not TBI experts. FBWC personnel began by offering the HELPS upon intake to survivors seeking services. The initial findings found that over 50% of survivors screened positive for a potential brain injury incident. With this knowledge, FBWC program leadership began exploring neurofeedback as an innovative approach to assisting survivors exhibiting symptoms of TBI. FBWC approached another non-profit organization that was focused on researching and propagating neurofeedback in public school-based settings. After deliberations between leadership groups, a budget and project plan was finalized.

FBWC leadership began seeking funding from various sources and, after several attempts over approximately 18 months, two sources (one governmental, one non-governmental) agreed to fund the initial work of the neurofeedback project. Initial funding covered the neurofeedback equipment as well as the cost of setup, training, and mentoring by a board-certified neurofeedback clinician. In late 2014, FBWC began an initial pilot program to determine the impact and efficacy of a neurofeedback training program for Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) survivors with potential brain injury in an agency setting.

In 2017, I (Dessie Clark) traveled to Houston, Texas where she was introduced to Abeer Monem, the previous Chief Programs Officer of FBWC. During this meeting, Abeer shared information about an innovative neurofeedback program that was happening at FBWC. She described the approach and noted that they had been collecting data on the program to try to assess efficacy and impact. Dessie was intrigued and agreed to visit the site later that week. Upon arrival, Dessie was introduced to Joshua Brown, a board-certified neurofeedback clinician, who was the Director of Special Initiatives (now Chief Programs Officer) and one of the founders of the neurofeedback program. After multiple discussions, an agreement was reached between the two parties to begin a collaboration.

Community Assets & Needs

Fort Bend Women’s Center provides comprehensive services for survivors such as emergency shelter, case management, counseling, housing services, and legal aid. It is important to acknowledge that there are components of Fort Bend Women’s Center that are unique to the way the agency approaches service provision. Community assets will vary widely, even amongst similar populations. That being said, we believe the following assets are important to intimate partner violence survivors generally. First, FBWC emphasizes a trauma-informed care approach to working with survivors. The service model is voluntary (as opposed to other models that may have mandatory or compulsory services) and non-judgmental. Specifically, at FBWC, there was existing trust between staff and survivors. This is largely due to a rules reduction , trauma-informed care model that focuses on enhancing internal motivation in survivors and open and honest communication with staff. This helps to create a culture where survivors feel willing and able to be more open about their experiences and the challenges they are facing. Important elements of this model include the offering of voluntary services and non-judgmental advocacy. This model has led to survivors developing a vested interest in the success of FBWC as an agency. Many survivors participated in the research because they felt motivated to share with others their positive experiences at FBWC. Also, many survivors return to FBWC to volunteer following service provision. Please note that the intrinsic motivation to stay involved with FBWC is not a common phenomenon in this community. This illustrates the importance of continual work on trust, safety, and confidentiality.

The IPV survivor community has myriad needs, and no one IPV community will have the same needs. For this partnership, there were several key needs of the survivors at Fort Bend Women’s Center that became vital to address in order to successfully implement the partnership. These needs included trust, safety, confidentiality, and adaptability. Given the trauma that survivors have experienced, these components need to be taken into consideration in interactions with other survivors, staff, and members of the research team.

The survivor population at Fort Bend Women’s Center have experienced violence from a family member and/or sexual assault. FBWC data suggests that over half of the survivors seeking services at FBWC have experienced multiple traumatic experiences. Additionally, some survivors may have had difficult experiences with the justice system, the medical establishment, and other helping professionals. Experiences of trauma can cause distrust from the survivor when seeking services. Additionally, there is a high incidence of mental health disorders in survivors, including paranoia, that can impede the creation of a trusting relationship. Establishing trust became a vital step in survivor recruitment. For effective recruitment, it was imperative that survivors trusted that their information would be kept in confidence and that what they were being asked to participate in would not harm them. As previously mentioned, a culture of trust already existed between survivors and staff. The research team was able to build on this by including staff in the research collaboration. Staff members were included in project development, which allowed them to have a deeper understanding of the work. Staff’s enthusiasm for the collaboration, which was shared with survivors, helped extend the pre-existing trust that survivors had with staff members to the research collaboration.

Safety is of utmost importance to survivors who are fleeing violence. While one might only think of physical safety with this population, it is also important to take psychological safety into account. Steps were taken in this program to ensure that participating survivors understood the likelihood of any psychological harm due to sharing their traumatic experiences. Mental health staff was identified on a rotating basis to act as an on-call resource should survivors need it.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality of personal information directly involves trust and safety. Many survivors in our program feared for their lives and did not want anyone to know where they were or what they were doing. It is important when working with this population to ensure confidentiality. This is not only ethically and legally important, it is also important in building a long-lasting program. When thinking about effective confidentiality, one should consider their applicable agency, state, and federal confidentiality rules and regulations. At a minimum, it is important to execute a confidentiality agreement with the participant.

Collaborative Partners

To begin the process of engaging in effective research collaborations, it is often difficult to identify an effective community partner, and it is a somewhat arduous process. While individuals and organizations in academia understand the merits of research, this is not always the case for community organizations. Even in cases where community organizations recognize these benefits, there may be barriers, such as trust, due to historical harms done to communities by researchers. Additionally, community organizations often face strains due to limited resources or capacity to support research which researchers may fail to acknowledge or understand. These issues can create barriers for researchers who are interested in partnering with organizations that have survivor populations. This also causes issues for community organizations who may be less likely to have access to research, including best practices, given academic publishing practices.

Building understanding and trust between researchers and community partners is at the heart of a successful collaboration. A solid research partnership with a community organization requires buy-in from both sides. Whether from the perspective of the community organization or the researcher, it is imperative to find a partner that communicates effectively. This involves clearly defining each party’s expectations upfront, making sure that the terms that are used are clearly understood (including any potential jargon), and discussing the importance of flexibility in timelines. A great example of the lack of work on building understanding and trust is the story of the (now-defunct) nonprofit Southwest Health Technology Foundation (SWHTF) in which one author, Joshua Brown, was an employee. SWHTF was a small organization that was focused on evaluating the effectiveness of neurofeedback in existing systems (such as public schools). SWHTF began several data-driven pilot projects without the assistance of a research partner. These data showed the potential positive effects of neurofeedback interventions on behavior and academic performance. However, these data never saw the light of day. SWHTF leadership attempted to partner with four different research institutions to analyze the data. All four attempts ultimately failed without yielding tangible results. This was due to a failure on the part of SWHTF and the researchers to build trust and understanding through defining clear expectations, clearly understanding each party’s role, and agreeing on expected outcomes.

An important part of building trust is approaching a partnership with strategies that are aimed at the education of staff and survivors who will be involved. While SWHTF is a relevant example, the focus of this case study is the project conducted with Fort Bend Women’s Center (FBWC). We found the most effective approach to building trust and understanding was to focus on educating staff about our project first. We identified the case managers as those staff who have the most contact with survivors and have built up the most trust. When educating staff members, we found that it wasn’t as important that they fully understood all the specifics of the project but, rather, that they had enough of a basic level of knowledge about the project to introduce the information to the survivor. Because case managers had built up trust with the survivors, the survivors were much more likely to take the recommendation of the case manager and enroll in the program. Because our case managers were not subject experts, survivors were willing to speak to researchers even without an understanding of the specifics. The specifics were provided by researchers and program staff before enrollment.

In order to understand how a community navigates issues related to gender-based violence, it is important to understand the ways in which the culture of that community may impact their perspective. The key stakeholders in this project included the funding entities, the Chief Programs Officer, the Neurofeedback program Lead, and members of the Neurofeedback team. The population consisted of survivors of gender-based violence; both those who had completed a neurofeedback program and those who had not yet done so but desired to do so in the future. This research collaboration was between researchers at Michigan State University and Fort Bend Women’s Center. The organization, which served as the primary setting for the project, provides emergency shelter, housing/rental assistance, and supportive services. The project was predominantly made up of those located within the agency as staff members while researchers at Michigan State University primarily served as guides and consultants for the research portion of the project. For this project, funders included the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, the George Foundation, the Simmons Foundation, and the Office for Victims of Crime.

Project Description

This case study involved a multi-year collaboration. During the initial six-months, a series of site visits were conducted with the goal of researchers getting to know staff members of the community organization, as well as the survivors who received services from the organization. Before engaging in any research, a multi-day feedback session was held in which staff members from the organization gave feedback on the research including the approach, questions, assessment tools, and logistics of how the research would be conducted. In these sessions, it became clear that given the population being served at this site, to include high numbers of disabled or immigrant survivors, there would need to be adjustments for accessibility and safety. Other barriers specific to this collaboration included staff burdens, the distance between researcher and community partner, and various considerations given the population such as trauma responses, trauma history, and the relatively transient nature of the population. Additionally, the research and data collection experience of the staff at the community organization was limited. These conversations were critical in helping the community organization familiarize themselves with the research and the researcher obtain a better understanding of the unique strains the organization was facing in conducting the research. As such, novel processes had to be developed and reinforced to ensure adequate data collection and analysis. We involved considerations for a variety of perspectives that may be shared by survivors in our data collection approach. We would do this in the future, with more frequent check-ins with participants and staff.

The collaboration consisted of frequent communication between the researchers and the organization. Additionally, site visits happened semi-annually. Key outcomes included – efficacy of the intervention was established, adaptive technology was created, and we found evidence of a successful collaboration. The neurofeedback intervention resulted in statistically significant decreases in depression, anxiety, PTSD, and disability symptomology for survivors. Survivors also experienced normalization of brain activity. This provides evidence that neurofeedback can benefit the well-being of survivors. Given the distance between Michigan and Texas, a system was created for checking in, transferring data, and ensuring that all necessary tasks were completed. A particularly novel component of this collaboration was the creation of an app for mobile phones that allowed for data to be transferred securely from Texas, in areas where Wi-Fi may not be present, to Michigan. The creation of a mobile phone app can be replicated. This was an important aspect of conducting research with a population where safety was critical, and Wi-Fi may not always be accessible. Finishing the project, and creating tools to do so, is in itself an indicator that the collaboration was successful. However, this project resulted in a host of other products such as publications, technical reports, presentations, and an awarded grant which also indicate that this collaboration produced well-recognized resources. Not a traditional metric, but one of great importance to the authors is the fact that both the agency and the researchers wish to work together in the future.

Lessons Learned

Over the course of the 3-year collaboration, we learned many lessons about conducting rigorous research with community partners who serve survivors of gender-based violence. However, we highlight the four biggest takeaways from our collaboration – (1) communication, (2) trust, (3) buy-in, and (4) resources. It’s important to note that there is no such thing as a perfect collaboration. Collaborations can be successful, produce important results, and still face challenges. It’s important to note that there is no such thing as a perfect collaboration. Collaborations can be successful, produce important results, and still face challenges. That is true of our collaboration, in which we did face challenges. For domestic violence agencies, there is one overarching consideration that impacts the four takeaways we will discuss below – turnover and movement of staff. Turnover and movement of staff is relatively common in community agencies and that means that there is a constant need to set and reset expectations to make sure everyone has the same information about the project and what is expected of them. These expectations need to be reinforced frequently to ensure there are no issues that need to be addressed. For example, in the first 3 years of our collaboration, we experienced 3 different neurofeedback team leads and have seen the neurofeedback clinical team have full turnover twice. Our experience underlines the importance of consistently resetting expectations.

Communication

We have found in collaborations with multiple parties, particularly those that are conducted long-distance, communication is perhaps the most important ingredient for success. How do you work collaboratively when not in the same space? For us, it was critical to use technology. We used secure platforms to share information and have important conversations. However, having conversations is not enough. It is important these conversations do not use jargon. For example, there are certain technical terms that researchers or practitioners may use which are not clear and can lead to confusion. It’s also important to share perspectives on what the priorities are for different parties. For example, researchers may be worried about things such as missing data whereas counselors may be more willing to collect minimal data in an effort to move on to the next survivor more quickly or to protect survivor confidentiality. Communication is complicated, especially at a distance. It’s important to realize you may do the best you can and still have problems communicating. Defining modes of communication, and what expectations are, is also critical. For example, what constitutes an email versus a call, how frequent those communications will be, and what expectations are for when those communications will be returned.

It is critical that there is trust between all parties. The survivors must trust the community partner and the researchers, the community partners must trust the researchers, and the researchers must trust the community partners and the survivors. This can create a complex web of dynamics that can be vulnerable to changes and miscommunications. In our collaboration, there were moments where trust and understanding between the researchers and the community partners were limited. In retrospect, it was important for community partners and researchers to sit down and share their perspectives and approach to work. For example, researchers may be more focused on details like completing paperwork properly or recruitment and retention of participants. Whereas, community partners may be more focused on completing interventions or connecting survivors to resources. In both cases, these duties are appropriate for the position but given the rapidly changing needs of survivors, the priorities may not be in alignment across groups. It is critical for both parties to understand where the other is coming from and trust that the necessary steps for the project will be completed. Collaborations should tackle this issue by communicating freely and openly and not resulting in micromanaging or avoiding these issues. Collaborators must trust that all members of the collaboration will do their part and be transparent if and when issues arise. In our case, this impacted survivors’ access to the project because at times, due to other survivor or agency demands, staff members were not actively talking to survivors about the project and what it may entail to become involved and learn more.

Ensuring that researchers, community stakeholders, and survivors have bought into the project and understand the project plan is important in ensuring things run smoothly. While the project itself may involve conducting research, it’s important to elicit feedback from the other collaborators at all aspects of the process. In our case, we asked staff members and survivors to provide feedback on the project design and survey. We hosted a multi-day training to talk through the process, the questions we were asking, and gather feedback on what we should know to inform the project moving forward. However, as referenced above, these agencies may experience frequent turnover of staff movement. As such, is it important to check in about buy-in over the course of the project – but particularly when there are transitions.

Working with community partners, who are often over-burdened and under-resourced, requires acknowledgment and supplementation from other collaborators. In our case, it was important for the researchers to design and adjust the project to best meet the needs of the community partner and survivors. We did this by:

- Taking over aspects of the project like data collection to the extent that was allowable given distance and travel,

- Hiring staff members as research assistants to help with data collection; and

- Creating a phone application that allowed for information necessary for the project to be directly transmitted to a secure server at MSU.

While for many of our lessons learned, we have concrete suggestions for future work, we do find ourselves with one lesson we have learned but have not solved. A constant challenge on this project was learning how to deal with staff burnout – both in their roles and in regard to the research project. For example, as we’ve mentioned staff at these agencies are often overburdened and under-resourced. Participating in research can exacerbate these issues and lead to a faster rate of burnout or what we observed and have called “research fatigue”. We believe that having a place to vent frustrations about the research project so they may be dealt with is a promising thought. However, this is a bit complicated as it seems that staff may be unsure of the appropriate avenue to share these concerns – whether it should be their agency supervisor or a member of the research team.

Research Process

A relatively unique aspect of this project was the willingness of staff to engage in all aspects of the research process. Members of FBWC were engaged throughout the entire process from project conceptualization to dissemination of information. The key stakeholder, Joshua Brown, was eager to be involved in research. However, this was only possible because Dessie Clark suggested the possibility and Joshua didn’t know that it is unusual for community partners to be involved. This highlights the importance for researchers and community partners to be talking about research, the degree to which each member wants to be involved, and what expectations will be. The authors of this chapter had many conversations about authorship on all the produced works and what workload and timeline would look like to live up to these expectations.

Looking Forward

As we continue to move forward, we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge the impacts of COVID-19 on the intimate partner survivors, the agencies (such as Fort Bend Women’s Center) that serve them, and research for those housed in a University setting. Before COVID-19 we imagined continuing our work in many of the same ways. We had applied for future grants and dreamed of expanding our work to examine the children’s neurofeedback program at Fort Bend Women’s Center. While we hope that eventually conducting our work, in-person, will continue, it seems prudent to reimagine what working together will look like in our altered state. It is the intention of the authors to continue collaborating. However, this may require adjusting to continue working in a virtual matter. Given the fact that technology has already been an important part of our process as long-distance partners, we hope that future work uses those technologies (digital survey platform, phone app for information transfer, etc.) to continue to collect important information that ultimately benefits survivors and their communities.

Recommendations

While gender-based violence is often examined at the individual level, communities play an important role in how gender-based violence is addressed and how survivors are supported. Communities can be a tremendous source of support for survivors by providing social support through which these individuals can access resources, and connect to services. In this way, communities have the potential to be a tremendous source of support for survivors. Or, in contrast, communities can impose substantial barriers on survivors and their families. Since structurally, communities are located closest to survivors, understanding how gender-based violence is addressed by, and within, communities is important in understanding and confronting gender-based violence as a society. The nature of this work was relatively clinical in nature (e.g. neurofeedback) where community relationships and community-engaged research are not a typical fixture. This effort provides suggestions for how those in clinical disciplines, like clinical psychology or social work, may conduct work with community psychologists that are more interdisciplinary in nature.

Further recommendations include:

- Examining how those who do more clinical/individual work may engage with communities,

- The use of technology to conduct and engage in community work, and

- How researchers may do work in communities that is rigorous, such as the waitlist control trial done here, and is not limited to that which can be done inside a lab.

A frequent conversation between the authors of this article was about the wall that exists between researchers and communities. Often, it is assumed that communities do not value or understand research. Or, conversely, that any research that can be done in community settings is not rigorous or worthwhile. Our experiences show the inaccuracy of these assumptions. Fort Bend Women’s Center created the neurofeedback program with research in mind. They implemented best practices and collected necessary data. While they didn’t have the resources to compile and analyze the data in ways that could be presented to the scientific community – they were certainly open and eager for the opportunity. Additionally, the research that has been done in this collaboration so far has been recognized widely and invited to contribute to special issues and conference keynotes – a marker of success in the scientific community. This was successful because people, located in very different spaces, were willing to discuss how they could meet in the middle to accomplish a common goal. The experiences of survivors happen in real-world settings and it was important to capture their lived experiences in that setting.

It is important to take the time on the front end to develop a plan. But, also, recognizing that plan likely will change. There should be explicit plans for action with turnover and communication. The priorities of the work should be established and reinforced. This includes defining what priorities are overlapping, and what priorities are important to researchers and community partners so they can work together effectively. Given the fluid nature of research, domestic violence organizations, and survivors it is important for everyone to be willing to adapt. Researchers may be forced to make changes to the research plan, particularly to meet staff and survivors’ needs. The agency may need to adapt to ensure that the research components fit into their own expectations and be willing to give feedback if they do not so adjustments can be made.

Implications for Community Psychology

There has been a multitude of promising results from this project including, establishing the efficacy of the intervention, creation of adaptive technology, and evidence of successful collaboration. In our case, researchers and community partners have published and presented in academic spaces and created a technical report for practitioners. Community psychology theory often focuses on engaging local communities that are relatively close to the research team. This case study has implications for how to do community-engaged research over a long distance using various technologies. This has the potential to further the conversation on how we can engage and work with communities when physical access may not be possible. This is important as funding and travel can pose barriers to certain populations and novel ways of doing this work may present additional opportunities for other researchers.

The authors of this case story believe that finding creative ways to manage mostly virtual relationships, as we have done here, has always been a critical component of doing community psychology work. However, as we wrote this chapter during COVID-19 we realized that what has been important to those of us striving to reach vulnerable populations in hard-to-reach locations is now a standard challenge. While community psychology has always pushed innovative ways to do community work, limited conversations have evolved on how adaptive technology could and should be used to try to ensure successful collaborations, particularly collaborations across distance.

From Theory to Practice Reflections and Questions

- Gender-based violence is a rapidly growing social concern and even more so as the world continues to grapple with the effects of Covid-19 (Clark & Brown, 2021). How does the discussion in this case study challenge your thinking regarding traumatic brain injury (TBI) and gender-based violence?

- Reflect upon conversations you have heard and/or had on gender-based violence. List 3-5 statements you have heard. Based on these statements what would you consider about society’s response to this issue? If you have not heard any stereotypical or other statements, research 3-5 statements and answer the same question.

- How would you go about creating an alternate setting to address this challenge in the community?

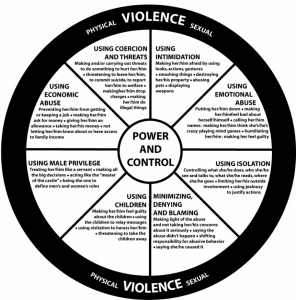

Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (n.d.).The Domestic Violence Power and Control Wheel https://www.thehotline.org/identify-abuse/power-and-control/

Case Studies in Community Psychology Practice: A Global Lens Copyright © 2021 by See Contributors Page for list of authors (Edited by Geraldine Palmer, Todd Rogers, Judah Viola, and Maronica Engel) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

Important Safety Information

QUICK CLOSE at the top of the page will exit this site immediately and take you to google.co.uk.

This will not hide the fact that you have been on our website.

If you are worried someone will know you are trying to find help, please read our instructions on how to browse safely. Follow the "Browse safely" link at the top of the screen.

Continue to site

- Skip to navigation

- Skip to content

- Browse safely

In their own words

Sometimes it helps to read other people’s stories. These case studies of domestic abuse highlight some real stories.

Psychological abuse - Marianna's story

Physical abuse - jenny's story, sexual abuse - husna's story, financial abuse - halima's story, emotional abuse - jane's story.

Are you in an abusive relationship?

Women’s Aid have a checklist that can help you identify if you are in an abusive relationship.

- Are you in danger now?

- Are you looking for legal advice about domestic abuse?

- Are you looking for local support about domestic abuse?

- What is domestic abuse?

- Open access

- Published: 20 June 2023

A qualitative quantitative mixed methods study of domestic violence against women

- Mina Shayestefar 1 ,

- Mohadese Saffari 1 ,

- Razieh Gholamhosseinzadeh 2 ,

- Monir Nobahar 3 , 4 ,

- Majid Mirmohammadkhani 4 ,

- Seyed Hossein Shahcheragh 5 &

- Zahra Khosravi 6

BMC Women's Health volume 23 , Article number: 322 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

8359 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication. Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society. The objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan.

This study was conducted as mixed research (cross-sectional descriptive and phenomenological qualitative methods) to investigate domestic violence against women, and some related factors (quantitative) and experiences of such violence (qualitative) simultaneously in Semnan. In quantitative study, cluster sampling was conducted based on the areas covered by health centers from married women living in Semnan since March 2021 to March 2022 using Domestic Violence Questionnaire. Then, the obtained data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics. In qualitative study by phenomenological approach and purposive sampling until data saturation, 9 women were selected who had referred to the counseling units of Semnan health centers due to domestic violence, since March 2021 to March 2022 and in-depth and semi-structured interviews were conducted. The conducted interviews were analyzed using Colaizzi’s 7-step method.

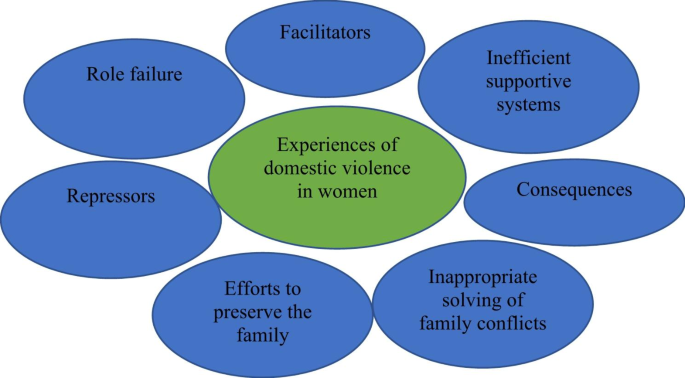

In qualitative study, seven themes were found including “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems”. In quantitative study, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage had a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of the number of children had a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). Also, increasing the level of female education and income both independently showed a significant relationship with increasing the score of violence.

Conclusions

Some of the variables of violence against women are known and the need for prevention and plans to take action before their occurrence is well felt. Also, supportive mechanisms with objective and taboo-breaking results should be implemented to minimize harm to women, and their children and families seriously.

Peer Review reports

Violence against women by husbands (physical, sexual and psychological violence) is one of the basic problems of public health and violation of women’s human rights. It is estimated that 35% of women and almost one out of every three women aged 15–49 experience physical or sexual violence by their spouse or non-spouse sexual violence in their lifetime [ 1 ]. This is a nationwide public health issue, and nearly every healthcare worker will encounter a patient who has suffered from some type of domestic or family violence. Unfortunately, different forms of family violence are often interconnected. The “cycle of abuse” frequently persists from children who witness it to their adult relationships, and ultimately to the care of the elderly [ 2 ]. This violence includes a range of physical, sexual and psychological actions, control, threats, aggression, abuse, and rape [ 3 ].

Violence against women is one of the most widespread, persistent, and detrimental violations of human rights in today’s world, which has not been reported in most cases due to impunity, silence, stigma and shame, even in the age of social communication [ 3 ]. In the United States of America, more than one in three women (35.6%) experience rape, physical violence, and intimate partner violence (IPV) during their lifetime. Compared to men, women are nearly twice as likely (13.8% vs. 24.3%) to experience severe physical violence such as choking, burns, and threats with knives or guns [ 4 ]. The higher prevalence of violence against women can be due to the situational deprivation of women in patriarchal societies [ 5 ]. The prevalence of domestic violence in Iran reported 22.9%. The maximum of prevalence estimated in Tehran and Zahedan, respectively [ 6 ]. Currently, Iran has high levels of violence against women, and the provinces with the highest rates of unemployment and poverty also have the highest levels of violence against women [ 7 ].

Domestic violence against women harms individuals, families, and society [ 8 ]. Violence against women leads to physical, sexual, psychological harm or suffering, including threats, coercion and arbitrary deprivation of their freedom in public and private life. Also, such violence is associated with harmful effects on women’s sexual reproductive health, including sexually transmitted infection such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), abortion, unsafe childbirth, and risky sexual behaviors [ 9 ]. There are high levels of psychological, sexual and physical domestic abuse among pregnant women [ 10 ]. Also, women with postpartum depression are significantly more likely to experience domestic violence during pregnancy [ 11 ].

Prompt attention to women’s health and rights at all levels is necessary, which reduces this problem and its risk factors [ 12 ]. Because women prefer to remain silent about domestic violence and there is a need to introduce immediate prevention programs to end domestic violence [ 13 ]. violence against women, which is an important public health problem, and concerns about human rights require careful study and the application of appropriate policies [ 14 ]. Also, the efforts to change the circumstances in which women face domestic violence remain significantly insufficient [ 15 ]. Given that few clear studies on violence against women and at the same time interviews with these people regarding their life experiences are available, the authors attempted to planning this research aims to investigate the prevalence and experiences of domestic violence against women in Semnan with the research question of “What is the prevalence of domestic violence against women in Semnan, and what are their experiences of such violence?”, so that their results can be used in part of the future planning in the health system of the society.

This study is a combination of cross-sectional and phenomenology studies in order to investigate the amount of domestic violence against women and some related factors (quantitative) and their experience of this violence (qualitative) simultaneously in the Semnan city. This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences with ethic code of IR.SEMUMS.REC.1397.182. The researcher introduced herself to the research participants, explained the purpose of the study, and then obtained informed written consent. It was assured to the research units that the collected information will be anonymous and kept confidential. The participants were informed that participation in the study was entirely voluntary, so they can withdraw from the study at any time with confidence. The participants were notified that more than one interview session may be necessary. To increase the trustworthiness of the study, Guba and Lincoln’s criteria for rigor, including credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [ 16 ], were applied throughout the research process. The COREQ checklist was used to assess the present study quality. The researchers used observational notes for reflexivity and it preserved in all phases of this qualitative research process.

Qualitative method

Based on the phenomenological approach and with the purposeful sampling method, nine women who had referred to the counseling units of healthcare centers in Semnan city due to domestic violence in February 2021 to March 2022 were participated in the present study. The inclusion criteria for the study included marriage, a history of visiting a health center consultant due to domestic violence, and consent to participate in the study and unwillingness to participate in the study was the exclusion criteria. Each participant invited to the study by a telephone conversation about study aims and researcher information. The interviews place selected through agreement of the participant and the researcher and a place with the least environmental disturbance. Before starting each interview, the informed consent and all of the ethical considerations, including the purpose of the research, voluntary participation, confidentiality of the information were completely explained and they were asked to sign the written consent form. The participants were interviewed by depth, semi-structured and face-to-face interviews based on the main research question. Interviews were conducted by a female health services researcher with a background in nursing (M.Sh.). Data collection was continued until the data saturation and no new data appeared. Only the participants and the researcher were present during the interviews. All interviews were recorded by a MP3 Player by permission of the participants before starting. Interviews were not repeated. No additional field notes were taken during or after the interview.

The age range of the participants was from 38 to 55 years and their average age was 40 years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in table below (Table 1 ).

Five interviews in the courtyards of healthcare centers, 2 interviews in the park, and 2 interviews at the participants’ homes were conducted. The duration of the interviews varied from 45 min to one hour. The main research question was “What is your experience about domestic violence?“. According to the research progress some other questions were asked in line with the main question of the research.

The conducted interviews were analyzed by using the 7 steps Colizzi’s method [ 17 ]. In order to empathize with the participants, each interview was read several times and transcribed. Then two researchers (M.Sh. and M.N.) extracted the phrases that were directly related to the phenomenon of domestic violence against women independently and distinguished from other sentences by underlining them. Then these codes were organized into thematic clusters and the formulated concepts were sorted into specific thematic categories.

In the final stage, in order to make the data reliable, the researcher again referred to 2 participants and checked their agreement with their perceptions of the content. Also, possible important contents were discussed and clarified, and in this way, agreement and approval of the samples was obtained.

Quantitative method

The cross-sectional study was implemented from February 2021 to March 2022 with cluster sampling of married women in areas of 3 healthcare centers in Semnan city. Those participants who were married and agreed with the written and verbal informed consent about the ethical considerations were included to the study. The questionnaire was completed by the participants in paper and online form.

The instrument was the standard questionnaire of domestic violence against women by Mohseni Tabrizi et al. [ 18 ]. In the questionnaire, questions 1–10, 11–36, 37–65 and 66–71 related to sociodemographic information, types of spousal abuse (psychological, economical, physical and sexual violence), patriarchal beliefs and traditions and family upbringing and learning violence, respectively. In total, this questionnaire has 71 items.

The scoring of the questionnaire has two parts and the answers to them are based on the Likert scale. Questions 11–36 and 66–71 are answered with always [ 4 ] to never (0) and questions 37–65 with completely agree [ 4 ] to completely disagree (0). The minimum and maximum score is 0 and 300, respectively. The total score of 0–60, 61–120 and higher than 121 demonstrates low, moderate and severe domestic violence against women, respectively [ 18 ].

In the study by Tabrizi et al., to evaluate the validity and reliability of this questionnaire, researchers tried to measure the face validity of the scale by the previous research. Those items and questions which their accuracies were confirmed by social science professors and experts used in the research, finally. The total Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.183, which confirmed that the reliability of the questions and items of the questionnaire is sufficient [ 18 ].

Descriptive data were reported using mean, standard deviation, frequency and percentage. Then, to measure the relationship between the variables, χ2 and Pearson tests also variance and regression analysis were performed. All analysis were performed by using SPSS version 26 and the significance level was considered as p < 0.05.

Qualitative results

According to the third step of Colaizzi’s 7-step method, the researcher attempted to conceptualize and formulate the extracted meanings. In this step, the primary codes were extracted from the important sentences related to the phenomenon of violence against women, which were marked by underlining, which are shown below as examples of this stage and coding.

The primary code of indifference to the father’s role was extracted from the following sentences. This is indifference in the role of the father in front of the children.

“Some time ago, I told him that our daughter is single-sided deaf. She has a doctor’s appointment; I have to take her to the doctor. He said that I don’t have money to give you. He doesn’t force himself to make money anyway” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“He didn’t value his own children. He didn’t think about his older children” (p 4, 54 yrs).

The primary code extracted here included lack of commitment in the role of head of the household. This is irresponsibility towards the family and meeting their needs.

“My husband was fired from work after 10 years due to disorder and laziness. Since then, he has not found a suitable job. Every time he went to work, he was fired after a month because of laziness” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“In the evening, he used to get dressed and go out, and he didn’t come back until late. Some nights, I was so afraid of being alone that I put a knife under my pillow when I slept” (p 2, 33 yrs).

A total of 246 primary codes were extracted from the interviews in the third step. In the fourth step, the researchers put the formulated concepts (primary codes) into 85 specific sub-categories.

Twenty-three categories were extracted from 85 sub-categories. In the sixth step, the concepts of the fifth step were integrated and formed seven themes (Table 2 ).

These themes included “Facilitators”, “Role failure”, “Repressors”, “Efforts to preserve the family”, “Inappropriate solving of family conflicts”, “Consequences”, and “Inefficient supportive systems” (Fig. 1 ).

Themes of domestic violence against women

Some of the statements of the participants on the theme of “ Facilitators” are listed below:

Husband’s criminal record

“He got his death sentence for drugs. But, at last it was ended for 10 years” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Inappropriate age for marriage

“At the age of thirteen, I married a boy who was 25 years old” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My first husband obeyed her parents. I was 12–13 years old” (p 3, 32 yrs).

“I couldn’t do anything. I was humiliated” (p 1, 38 yrs).

“A bridegroom came. The mother was against. She said, I am young. My older sister is not married yet, but I was eager to get married. I don’t know, maybe my father’s house was boring for me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“My parents used to argue badly. They blamed each other and I always wanted to run away from these arguments. I didn’t have the patience to talk to mom or dad and calm them down” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Overdependence

“My husband’s parents don’t stop interfering, but my husband doesn’t say anything because he is a student of his father. My husband is self-employed and works with his father on a truck” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“Every time I argue with my husband because of lack of money, my mother-in-law supported her son and brought him up very spoiled and lazy” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Bitter memories

“After three years, my mother married her friend with my uncle’s insistence and went to Shiraz. But, his condition was that she did not have the right to bring his daughter with her. In fact, my mother also got married out of necessity” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Some of their other statements related to “ Role failure” are mentioned below:

Lack of commitment to different roles

“I got angry several times and went to my father’s house because of my husband’s bad financial status and the fact that he doesn’t feel responsible to work and always says that he cannot find a job” (p 6, 48 yrs).

“I saw that he does not want to change in any way” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“No matter how kind I am, it does not work” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Repressors” are listed below:

Fear and silence

“My mother always forced me to continue living with my husband. Finally, my father had been poor. She all said that you didn’t listen to me when you wanted to get married, so you don’t have the right to get angry and come to me, I’m miserable enough” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“Because I suffered a lot in my first marital life. I was very humiliated. I said I would be fine with that. To be kind” (p1, 38 yrs).

“Well, I tell myself that he gets angry sometimes” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Shame from society

“I don’t want my daughter-in-law to know. She is not a relative” (p 4, 54 yrs).

Some of the statements of the participants regarding the theme of “ Efforts to preserve the family” are listed below:

Hope and trust

“I always hope in God and I am patient” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Efforts for children

“My divorce took a month. We got a divorce. I forgave my dowry and took my children instead” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Inappropriate solving of family conflicts” are listed below:

Child-bearing thoughts

“My husband wanted to take me to a doctor to treat me. But my father-in-law refused and said that instead of doing this and spending money, marry again. Marriage in the clans was much easier than any other work” (p 8, 25 yrs).

Lack of effective communication

“I was nervous about him, but I didn’t say anything” (p 5, 39 yrs).

“Now I am satisfied with my life and thank God it is better to listen to people’s words. Now there is someone above me so that people don’t talk behind me” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding the “ Consequences” are listed below:

Harm to children

“My eldest daughter, who was about 7–8 years old, behaved differently. Oh, I was angry. My children are mentally depressed and argue” (p 5, 39 yrs).

After divorce

“Even though I got a divorce, my mother and I came to a remote area due to the fear of what my family would say” (p 2, 33 yrs).

Social harm

“I work at a retirement center for living expenses” (p 2, 33 yrs).

“I had to go to clean the houses” (p 5, 39 yrs).

Non-acceptance in the family

“The children’s relationship with their father became bad. Because every time they saw their father sitting at home smoking, they got angry” (p 7, 55 yrs).

Emotional harm

“When I look back, I regret why I was not careful in my choice” (p 7, 55 yrs).

“I felt very bad. For being married to a man who is not bound by the family and is capricious” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Some of their other statements regarding “ Inefficient supportive systems” are listed below:

Inappropriate family support

“We didn’t have children. I was at my father’s house for about a month. After a month, when I came home, I saw that my husband had married again. I cried a lot that day. He said, God, I had to. I love you. My heart is broken, I have no one to share my words” (p 8, 25 yrs).

“My brother-in-law was like himself. His parents had also died. His sister did not listen at all” (p 4, 54 yrs).

“I didn’t have anyone and I was alone” (p 1, 38 yrs).

Inefficiency of social systems

“That day he argued with me, picked me up and threw me down some stairs in the middle of the yard. He came closer, sat on my stomach, grabbed my neck with both of his hands and wanted to strangle me. Until a long time later, I had kidney problems and my neck was bruised by her hand. Given that my aunt and her family were with us in a building, but she had no desire to testify and was afraid” (p 3, 32 yrs).

Undesired training and advice

“I told my mother, you just said no, how old I was? You never insisted on me and you didn’t listen to me that this man is not good for you” (p 9, 36 yrs).

Quantitative results

In the present study, 376 married women living in Semnan city participated in this study. The mean age of participants was 38.52 ± 10.38 years. The youngest participant was 18 and the oldest was 73 years old. The maximum age difference was 16 years. The years of marriage varied from one year to 40 years. Also, the number of children varied from no children to 7. The majority of them had 2 children (109, 29%). The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in the table below (Table 3 ).

The frequency distribution (number and percentage) of the participants in terms of the level of violence was as follows. 89 participants (23.7%) had experienced low violence, 59 participants (15.7%) had experienced moderate violence, and 228 participants (60.6%) had experienced severe violence.

Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of the questionnaire was 0.988. The mean and standard deviation of the total score of the questionnaire was 143.60 ± 74.70 with a range of 3-244. The relationship between the total score of the questionnaire and its fields, and some demographic variables is summarized in the table below (Table 4 ).

As shown in the table above, the variables of age, age difference and number of years of marriage have a positive and significant relationship, and the variable of number of children has a negative and significant relationship with the total score and all fields of the questionnaire (p < 0.05). However, the variable of education level difference showed no significant relationship with the total score and any of the fields. Also, the highest average score is related to patriarchal beliefs compared to other fields.

The comparison of the average total scores separately according to each variable showed the significant average difference in the variables of the previous marriage history of the woman, the result of the previous marriage of the woman, the education of the woman, the education of the man, the income of the woman, the income of the man, and the physical disease of the man (p < 0.05).

In the regression model, two variables remained in the final model, indicating the relationship between the variables and violence score and the importance of these two variables. An increase in women’s education and income level both independently show a significant relationship with an increase in violence score (Table 5 ).

The results of analysis of variance to compare the scores of each field of violence in the subgroups of the participants also showed that the experience and result of the woman’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with physical violence and tradition and family upbringing, the experience of the man’s previous marriage has a significant relationship with patriarchal belief, the education level of the woman has a significant relationship with all fields and the level of education of the man has a significant relationship with all fields except tradition and family upbringing (p < 0.05).

According to the results of both quantitative and qualitative studies, variables such as the young age of the woman and a large age difference are very important factors leading to an increase in violence. At a younger age, girls are afraid of the stigma of society and family, and being forced to remain silent can lead to an increase in domestic violence. As Gandhi et al. (2021) stated in their study in the same field, a lower marriage age leads to many vulnerabilities in women. Early marriage is a global problem associated with a wide range of health and social consequences, including violence for adolescent girls and women [ 12 ]. Also, Ahmadi et al. (2017) found similar findings, reporting a significant association among IPV and women age ≤ 40 years [ 19 ].

Two others categories of “Facilitators” in the present study were “Husband’s criminal record” and “Overdependence” which had a sub-category of “Forced cohabitation”. Ahmadi et al. (2017) reported in their population-based study in Iran that husband’s addiction and rented-householders have a significant association with IPV [ 19 ].

The patriarchal beliefs, which are rooted in the tradition and culture of society and family upbringing, scored the highest in relation to domestic violence in this study. On the other hand, in qualitative study, “Normalcy” of men’s anger and harassment of women in society is one of the “Repressors” of women to express violence. In the quantitative study, the increase in the women’s education and income level were predictors of the increase in violence. Although domestic violence is more common in some sections of society, women with a wide range of ages, different levels of education, and at different levels of society face this problem, most of which are not reported. Bukuluki et al. (2021) showed that women who agreed that it is good for a man to control his partner were more likely to experience physical violence [ 20 ].

Domestic violence leads to “Consequences” such as “Harm to children”, “Emotional harm”, “Social harm” to women and even “Non-acceptance in their own family”. Because divorce is a taboo in Iranian culture and the fear of humiliating women forces them to remain silent against domestic violence. Balsarkar (2021) stated that the fear of violence can prevent women from continuing their studies, working or exercising their political rights [ 8 ]. Also, Walker-Descarte et al. (2021) recognized domestic violence as a type of child maltreatment, and these abusive behaviors are associated with mental and physical health consequences [ 21 ].

On the other hand and based on the “Lack of effective communication” category, ignoring the role of the counselor in solving family conflicts and challenges in the life of couples in the present study was expressed by women with reasons such as lack of knowledge and family resistance to counseling. Several pathologies are needed to investigate increased domestic violence in situations such as during women’s pregnancy or infertility. Because the use of counseling for couples as a suitable solution should be considered along with their life challenges. Lin et al. (2022) stated that pregnant women were exposed to domestic violence for low birth weight in full term delivery. Spouse violence screening in the perinatal health care system should be considered important, especially for women who have had full-term low birth weight infants [ 22 ].

Also, lack of knowledge and low level of education have been found as other factors of violence in this study, which is very prominent in both qualitative and quantitative studies. Because the social systems and information about the existing laws should be followed properly in society to act as a deterrent. Psychological training and especially anger control and resilience skills during education at a younger age for girls and boys should be included in educational materials to determine the positive results in society in the long term. Manouchehri et al. (2022) stated that it seems necessary to train men about the negative impact of domestic violence on the current and future status of the family [ 23 ]. Balsarkar (2021) also stated that men and women who have not had the opportunity to question gender roles, attitudes and beliefs cannot change such things. Women who are unaware of their rights cannot claim. Governments and organizations cannot adequately address these issues without access to standards, guidelines and tools [ 8 ]. Machado et al. (2021) also stated that gender socialization reinforces gender inequalities and affects the behavior of men and women. So, highlighting this problem in different fields, especially in primary health care services, is a way to prevent IPV against women [ 24 ].