Press ESC to close

How to Conduct an Effective Literature Review for Your EPQ: A Step-by-Step Guide

- backlinkworks

- Writing Articles & Reviews

- September 23, 2023

Introduction

A literature review is an important component of any Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) project. IT involves researching and analyzing existing literature and scholarly works relevant to your topic. A well-conducted literature review can provide a solid foundation for your EPQ, helping you to identify gaps in the research, establish the context for your study, and build a strong theoretical framework.

Why is a literature review important?

Conducting an effective literature review is crucial for several reasons:

- Identifying existing knowledge: A literature review enables you to familiarize yourself with the existing research and theories related to your topic. This helps you understand what is already known, what gaps exist in the literature, and how your project can contribute to the field.

- Guiding your research: A well-constructed literature review can help you determine the direction and scope of your EPQ project. IT serves as a roadmap, assisting you in identifying the key concepts, theories, and methodologies that are relevant to your research.

- Building a theoretical framework: A literature review allows you to identify and analyze different theories and perspectives related to your topic. This helps you establish a strong theoretical foundation for your project and provides a basis for your analysis and interpretation of the data.

- Supporting your arguments: By citing relevant literature, you can support your arguments and claims with evidence from authoritative sources. This enhances the credibility and reliability of your EPQ project.

Step-by-Step Guide to Conducting an Effective Literature Review

1. define your research question.

The first step in conducting a literature review is to clearly define your research question or objective. This will help you narrow down your search and focus on the most relevant sources.

2. Develop a search strategy

Once you have defined your research question, you need to develop a search strategy to identify relevant literature. Start by brainstorming keywords and phrases related to your topic. Use synonyms and variations of these terms to broaden your search.

Next, identify the most appropriate sources for your research. These may include academic databases, libraries, online journals, books, and relevant websites. Consider both primary and secondary sources to ensure comprehensive coverage of your topic.

3. Conduct a literature search

Using your search strategy, begin exploring the identified sources. Start with academic databases like PubMed, Google Scholar, or JSTOR, as they provide access to a wide range of scholarly articles and research papers.

Make use of advanced search tools and filters to refine your search results. Take note of the relevant sources, including the title, authors, and abstracts, for further evaluation and analysis.

4. Evaluate the literature

After conducting the initial search, IT is important to critically evaluate the literature to determine its relevance, reliability, and credibility. Consider the following criteria:

- Publication date: Ensure that the sources you use are up-to-date and relevant to your research. However, older articles can be included to provide historical context or trace the development of a particular theory.

- Author credentials: Evaluate the expertise, qualifications, and reputation of the authors. Look for authors who are recognized authorities in the field.

- Research design and methodology: Assess the rigor and validity of the research methods used in the studies. Consider whether the sample size, data collection techniques, and analysis methods are appropriate and reliable.

- Consistency and relevance: Look for common themes, findings, and arguments across the literature. Ensure that the sources you select directly address your research question and contribute to the overall understanding of your topic.

5. Organize and synthesize the literature

Once you have evaluated the literature, IT is important to organize and synthesize the information. Create a clear structure for your literature review, categorizing the sources according to themes, theories, or methodologies.

Identify the main arguments, theories, and findings from each source, and compare and contrast them. Look for patterns and connections that emerge across the literature. This will help you build a coherent narrative and identify any gaps or debates in the existing research.

6. Write your literature review

With a clear synthesis of the literature, you can now begin writing your literature review. Follow a logical structure, starting with an introduction that provides an overview of the topic and states your research question or objective.

Organize the body of your literature review according to the themes, theories, or methodologies you have identified. Present the key findings and arguments from each source, critically analyzing and synthesizing the information.

Finally, conclude your literature review by summarizing the main points and highlighting the gaps or areas for further research. Make sure to cite all the sources you have referenced in a consistent citation style, such as APA or MLA.

A well-conducted literature review is a crucial step in any EPQ project. IT helps you identify and analyze the existing knowledge related to your topic, guides your research, builds a theoretical framework, and supports your arguments with credible evidence. By following the step-by-step guide outlined in this article, you can conduct an effective literature review that enhances the quality and impact of your EPQ project.

Q: How many sources should I include in my literature review?

The number of sources you include in your literature review largely depends on the scope of your research and the depth of existing literature on your topic. Aim for a balance between comprehensiveness and relevance. Include enough sources to demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the topic, but also focus on the most influential and recent works.

Q: How do I avoid plagiarism in my literature review?

To avoid plagiarism, IT is essential to properly attribute the ideas, opinions, and findings of other authors. Make sure to cite all the sources you have referenced in a consistent citation style, such as APA or MLA. Paraphrase and summarize the information in your own words, and use quotation marks for direct quotations. Always provide a clear citation whenever you use someone else’s work.

Q: Can I include non-academic sources in my literature review?

While academic sources are generally preferred for a literature review, IT might be relevant to include some non-academic sources, such as government reports, industry publications, or reputable websites. However, ensure that these sources are reliable, authoritative, and directly contribute to your research question.

Q: How do I determine the quality of a source?

When evaluating the quality of a source, consider the publication date, author credentials, research design and methodology, consistency and relevance to your research question. Look for peer-reviewed articles from reputable journals and books from renowned publishers. Assess the reliability and credibility of the sources by checking the reputation of the authors and the publication venues.

Q: Does the literature review come before or after the data collection?

The literature review usually comes before data collection in the research process. IT provides the theoretical and conceptual background for your study, helping you design your research methodology and data collection instruments. However, IT is important to continuously review and update the literature as your project progresses, as new studies and findings might emerge.

Introduction to Maya 3D: A Beginner’s Guide

10 best free one page wordpress themes for a stunning website.

Recent Posts

- Driving Organic Growth: How a Digital SEO Agency Can Drive Traffic to Your Website

- Mastering Local SEO for Web Agencies: Reaching Your Target Market

- The Ultimate Guide to Unlocking Powerful Backlinks for Your Website

- SEO vs. Paid Advertising: Finding the Right Balance for Your Web Marketing Strategy

- Discover the Secret Weapon for Local SEO Success: Local Link Building Services

Popular Posts

Shocking Secret Revealed: How Article PHP ID Can Transform Your Website!

Unlocking the Secrets to Boosting Your Alexa Rank, Google Pagerank, and Domain Age – See How You Can Dominate the Web!

Uncovering the Top Secret Tricks for Mastering SPIP PHP – You Won’t Believe What You’re Missing Out On!

The Ultimate Collection of Free Themes for Google Sites

Discover the Shocking Truth About Your Website’s Ranking – You Won’t Believe What This Checker Reveals!

Explore topics.

- Backlinks (2,425)

- Blog (2,744)

- Computers (5,318)

- Digital Marketing (7,741)

- Internet (6,340)

- Website (4,705)

- Wordpress (4,705)

- Writing Articles & Reviews (4,208)

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

EPQs: finding and using evidence

Finding the evidence that will help you understand a topic or answer a question is an important stage in the research process. And once you have found it, you will need to examine it closely and carefully, to judge how reliable it is and whether it is useful to help you answer your question.

The Extended Project Qualification (EPQ) is an opportunity for you to work independently on a topic that really interests you or that you think is important. It is equivalent to an A-level qualification. These articles are designed to help you if you are enrolled on an EPQ.

See previous article in series: Designing your research question

Before working through this article, you should have settled on your research question .

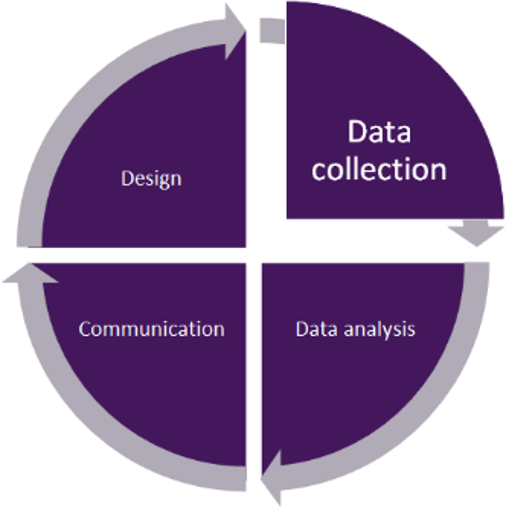

This article will support you through the next steps in the research cycle (Figure 1): collecting evidence (or data) to help you answer your question and starting your analysis of that evidence. First, let’s look at collecting data.

What is already known about your topic?

The first step in answering a research question is usually to do a ‘literature review’ or ‘research review’.

These articles focus on the ‘research review’ type of EPQ, in which collecting and analysing evidence from what other people have written will be a major part of what you do.

Researchers need to do research reviews for two reasons. First, they want to uncover what is already known. A lot is already known about some topics and they want to be sure that they are researching a novel question. Second, they want to get a balanced view of what is known, rather than jumping in and relying on the first pieces of information they find.

A literature review starts with focused and serious reading, to help you develop your knowledge and understanding of the topic, and begin to gather evidence that will help you answer your question.

Julia , a researcher in AstrobiologyOU, whose research explores the possibilities for habitable environments in the Solar System, demonstrates how she starts a literature review. As you read through, think about the process Julia describes and how you could apply the steps she takes to your EPQ research review.

- Starting a literature review.

When you’re starting a literature review, where do you look for evidence?

Any literature review requires a well-defined topic. Let’s assume the topic is something in planetary science!

Find an exciting topic: https://solarsystem.nasa.gov provides a good overview of our Solar System. Let’s pick Mars.

Define a specific question. How did Valles Marineris form?

Learn about Valles Marineris. You can use Wikipedia as a starting point and look up the references given there.

Use Google Scholar to find specific literature (e.g. search words such as *formation of Valles Marineris*). Look up research cited in the papers you read if they are also relevant to your topic. Make sure you always cite your sources.

My colleague Julia is a research fellow in AstrobiologyOU. She uses computer modelling to understand geological processes on planets such as Venus and Mars. For her, the process of starting a literature review is all about starting broad and gradually narrowing down. So, assuming that the topic is something in planetary science, start with something that gives you an overview. In this case, it’s the whole solar system. Then gradually coming in a step, first of all, focusing on one planet: Mars. Coming down to something on that planet; how did Valles Marineris form? And then having decided on the specific topic, learning more about it, Julia suggests using Wikipedia as a starting point, but looking up references given from it, and then using Google Scholar or other research engines to find specific literature, to look up research, and to find papers that are relevant to your topic.

Comments on Julia’s approach

You’ll notice that Julia starts from the ‘big picture’ and gradually focuses down to more specific material. This is very similar to the process you followed in article 1 ( Designing your research question ) to move from ‘this is a topic I’m interested in’ to ‘this is the question I want to ask’.

You’ll also notice that Julia moves from a quite open, broad source of evidence (Wikipedia) to using more serious sources (Google Scholar). There’s more on where and how to look for evidence in Section 4.

You will know that Wikipedia, despite having information about hundreds of thousands of topics, is not a 100% reliable source. Wikipedia can be a good place to start your research, get your ideas moving and find places where you can look for more information, but you should always cross-check any information you find there against another source.

Finding keywords.

With so much information available online, how do you begin finding relevant material? Most researchers start by assembling a collection of keywords that relate to the topic and can be used to search for more information. But how do you find those all-important keywords?

In some ways, deciding on your keywords is like the ‘ten words’ activity you used in Article 1 to help you move from topic to question.

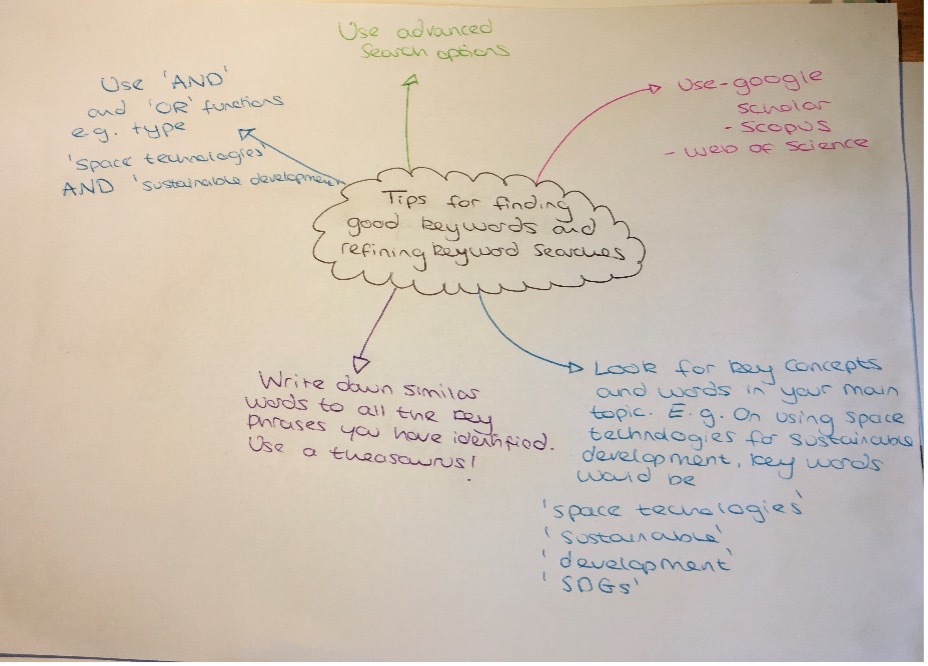

- Watch how Devyani creates a mind map

- Ann’s summary

Photo of mind map

But how do you come up with those all-important keywords? Devyani, who is a PhD student in AstrobiologyOU, gave me a few thoughts. As a PhD student, she’s just been through this process herself.

She suggested looking for key concepts and words in the main topic, perhaps splitting your question up and looking at separate elements of it. So for her, space technologies, sustainable development, SDGs, would be good keywords. Perhaps writing down similar words to the keywords that you've identified, using a thesaurus to help you find alternatives.

Once you start searching, using things like Google Scholar or the Web of Science, you can use advanced search options such as ‘and’ and ‘or’ functions to help you link topics that you need to look for.

We’ll come on to different places you can actually do your searches in a couple of minutes.

You might want to try Devyani’s method, or you could try this quick activity from The Open University to get started on finding good keywords.

Going back to the example research question we used in Article 1: ‘ How did young people use social media for activism?: comparing the content of Instagram posts on #blacklivesmatter and #FridaysForFuture during 2020’

What keywords might you use to search for relevant material to help answer this question? Perhaps you’d come up with ideas like “social media”, “activism”, “black lives matter”, “Fridays for future”.

As you can see, keywords can sometimes be more than one word!

Searching for evidence.

Having identified your keywords, the next step is to use them to start searching for evidence that will help you answer your research question.

Evidence can come from many sources: books; academic articles (often called ‘papers’); reports from businesses, charities and other organisations; newspaper articles; radio and television; websites; social media … the list could go on!

With so much material out there, it’s helpful to make a plan before you start your search. Think about:

- the keywords you will use

- the most useful places to search

- the time you have available for searching.

Keeping track .

You will gather a lot of information, so you should keep good records. Knowing what you’ve looked for, where you looked and what you found there will help you avoid repeating something you’ve already done. You’ll also be able to fully acknowledge the sources you have used in your research (this will be discussed further in Article 3 ). Make notes of:

- what keywords and combinations of keywords you used (your ‘search terms’)

- where you looked

- what documents you downloaded or read online

- notes you made about what you read.

You could keep a record in a simple table, perhaps on a spreadsheet (you can download an example here ).

For any documents you find, you’ll also find it useful to keep records of:

- the name of the author(s)

- when it was published

- the title of the article, report, book or chapter

- where it was published – i.e., the title of the journal, book or website

- a link to the document or its DOI (digital object identifier)

- (for books) the name of the publishing company and where it’s based.

The digital object identifier (DOI): You might not have come across a DOI before. Most academic articles have a DOI – a unique string of numbers and letters that is permanently attached to an article. If you paste a DOI into a browser, it will take you straight to that article. Try this one: https://doi.org/10.14324/RFA.05.2.14

When it comes to writing up your dissertation, these notes can be good evidence in themselves, showing how you carried out your review, so it’s sensible to get your record-keeping method set up before you begin searching.

Where should I search?

It’s very likely that you will carry out your search using online resources. But there are so many to choose from that it can be difficult to know where to start.

- Search engines

- University repositories

- Social media

- Researchers’ websites

- Scholarly databases

- Collections

- Journal websites

You can use the well-known search engines, such as Google, Bing or Yahoo, but you will get more reliable results if you use a specialised search engine such as Google Scholar , which returns links to articles and academic papers produced by researchers in universities and research institutions.

Many of the papers, articles, newspaper pieces and other items that you will find in your searching – but not all – will be open access, which means they are free to view and you can download them.

Many universities have repositories that store the work of researchers at that university. The Open University’s repository is called Open Research Online (ORO) . Most UK and international universities have something similar. Universities maintain these repositories because they want to make the work of their researchers available for others to use.

Repositories are often looked after by the university’s library team, so if you can’t find the repository easily, try looking on the library pages on the university website.

Online repositories usually allow you to search by a topic, or by the name of the author if you are trying to get hold of a particular resource.

If you’re interested in the work of a particular research group (such as AstrobiologyOU ) or a specific researcher, you’ll often find them on social media. Most research groups keep copies of work published by their researchers; it’s always worth contacting them. Explain that you want to use the research for your EPQ.

Researchers often have their own websites ( here’s an example ), which you can find using a search engine. If you can’t get hold of an article that you need for your work, email the researcher. Researchers are often willing to share copies of their work to help other researchers, so explain that you want to use it for your EPQ.

Many researchers keep copies of their papers and articles on networking sites such as ResearchGate , which also allow you to search by topic. However, these records are kept up to date by the researchers themselves, so you should always check against another source if you can.

Professional databases, such as Web of Science and EBSCO , bring together research from thousands of researchers across the world.

However, you will have to create an account, or pay a subscription to make full use of sites like this, which might not be practical for you.

If you find the researcher on the database but the paper you want isn’t there, use the database’s facilities to contact the researcher. Again, tell them why you want to read the article.

Universities and research institutions are increasingly bringing their resources together into large collections.

CORE is the world’s largest collection of open access research papers and articles.

ARXIV.org has more than a million articles, mainly in physics, mathematics and engineering.

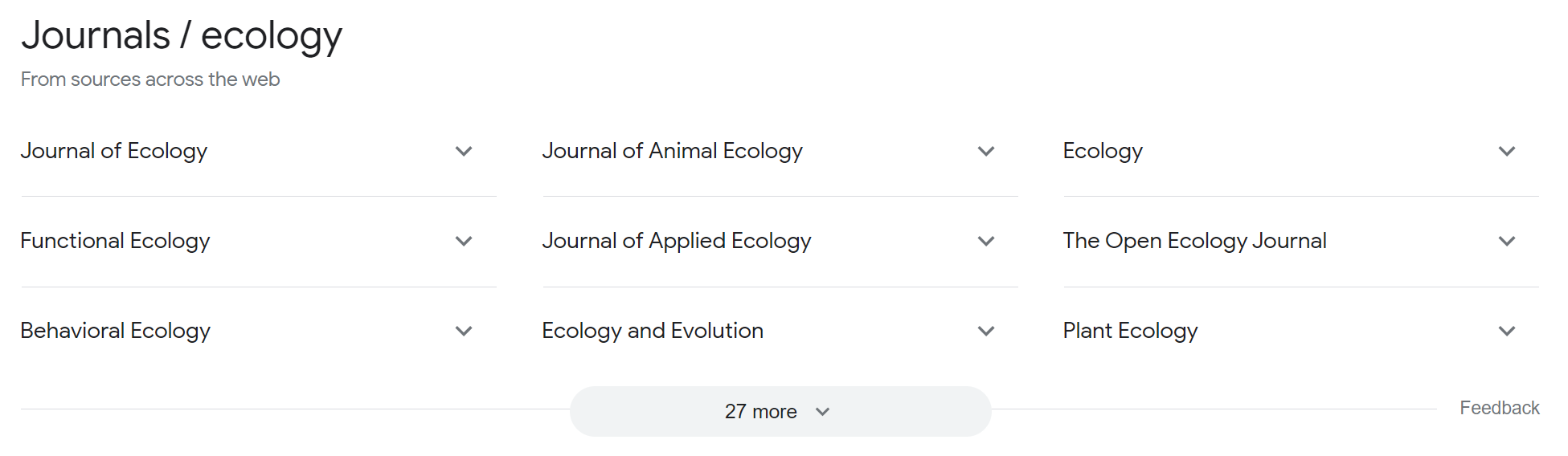

Journals are the places where researchers publish the articles that discuss their research. There are many thousands of academic journals in existence, covering every topic imaginable.

For example, try typing the phrase "ecology journal" (complete with speech marks) into a search engine. You will find a long list of possible titles is returned.

On the journals’ websites, you can search by topic to find relevant articles. If you are searching for a specific paper, and know the journal it was published in, you can use the journal’s search function to find it. However, many journals are commercial organisations and keep articles behind a ‘paywall’, meaning they are only available to people or institutions that subscribe to them.

Fortunately, more and more journals (for example PLoS – Public Library of Science ) are fully open access and many journals make some articles freely available.

Print media: If you’re looking for material published in newspapers or magazines, first try the website of the newspaper or search for their digital archive. If you can’t find it online, try your local public library; they often have access to hard-copy archives or can advise you where to find them.

Book publishers: There are many academic publishers, such as Ubiquity Press , that produce open access books you can download.

Organisations: research funders, such as the Wellcome Trust , make available copies of papers and reports written by their researchers. Other organisations’ websites, such as those from the government or charities, often have copies of project reports or annual reports available.

Public libraries: Finally, don’t forget your local public library. Even if they don't have the exact article or book you’re looking for on the premises, they have trained librarians who can help you find it or suggest alternative routes to get the information you need.

Refining your search.

Even if you use very specific keywords, an online search might return hundreds, if not thousands of results. How can you cut hundreds of results down to a sensible level?

Focusing and refining the keywords you use for your search will help you be realistic, making the best possible use of the limited time you have available for the EPQ, and cutting down your results to an amount that you can realistically deal with.

- Thoughts from Michael

Here are Michael’s key tactics for refining your searches:

- Linking several search terms to narrow down your search.

- Starting broad and then refining – he used a personal example where he started by looking for ‘bacteria associated with plants’ and narrowed down to ‘bacteria associated with peas’.

- Keeping track of your topics and sub-topics with a list, spreadsheet or mind map.

- Remembering you don’t have to read every single resource you find.

My colleague Michael, who’s a microbiologist, is particularly interested in looking at life in extreme environments on Earth that might be similar to places such as Mars.

He had some useful ideas on how to start refining your searches. He suggests linking search terms, so when searching online you can use symbols such as the plus sign and quotation marks that are incredibly helpful. Typing in ‘this’ plus ‘ that’ will return results that have both of those elements. Conversely, typing ‘this’ minus ‘ that’ will mean you only get results that include the phrase ‘this’. You can use quote marks to make phrases stick together, so quote marks "this stuff" and plus quote marks "that thing", will enable you to find papers that refer to both of those topics.

Michael also suggested it’s good to start broad and then refine searches. For example, for his PhD, he had to write several chapters for his thesis about bacteria that are associated with plants. The first searches were in the obvious place ‘plant-associated bacteria’, which he then refined to think about specific types of plant, such as ‘pea-associated bacteria’ or ‘legume-associated bacteria’. Those initial searches and papers allowed him to identify other useful terms that then meant he could be even more specific with his searches. For example, searching for ‘nitrogen’ plus ‘ plant-associated bacteria’ or ‘legumes’ minus ‘ disease’.

When searching, he also suggested it’s really helpful to keep track of topics and subtopics with a list, spreadsheet or a mind map. Whatever works for you. He found this helped him keep his notes organised and meant he didn’t have to repeat searches, because he had a record of what he had looked for.

But the most important point, he felt, was not to feel overwhelmed when doing a literature review. It’s possible to turn up hundreds of papers on any topic, but you don’t have to read all of them. As a start, he suggested that you look for review papers. These are papers in which the authors have pulled together material from several other sources. They give a really good introduction and overview of a topic, and can give you some clues on where to look next.

Practising searching using Google Scholar.

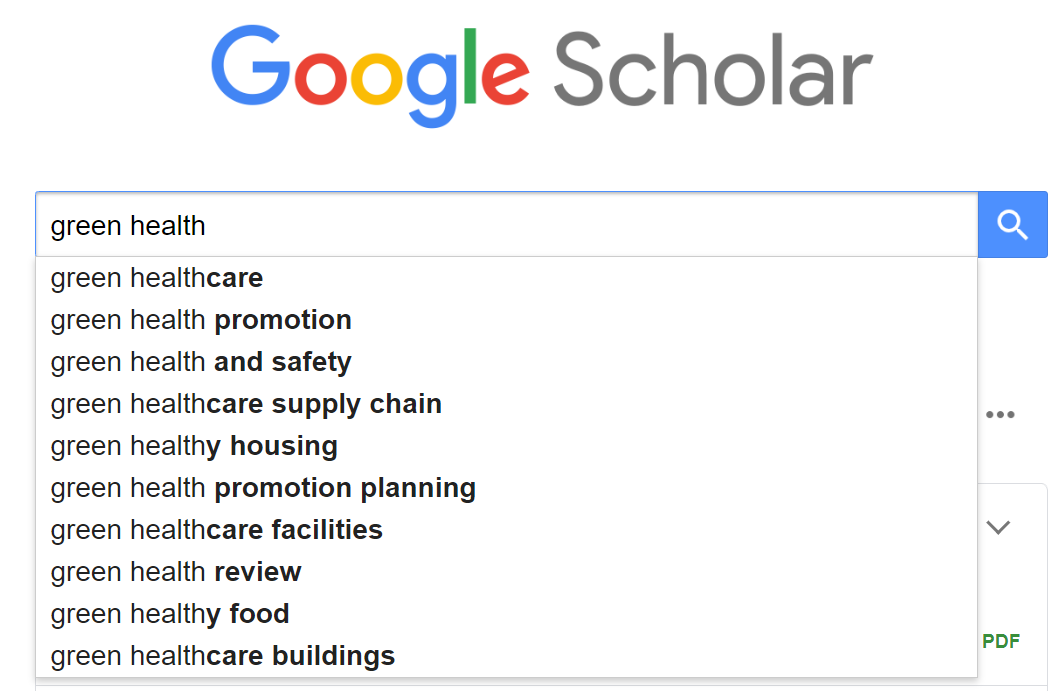

Google Scholar is a freely-available search engine that only returns links to scholarly literature, so it’s a good place to practise your searching techniques.

Imagine that you have decided to research this question:

What are the health benefits of people spending time in nature?

What are the keywords you could use in your search? You might think of:

- health

- nature therapy

- green health

- forest bathing

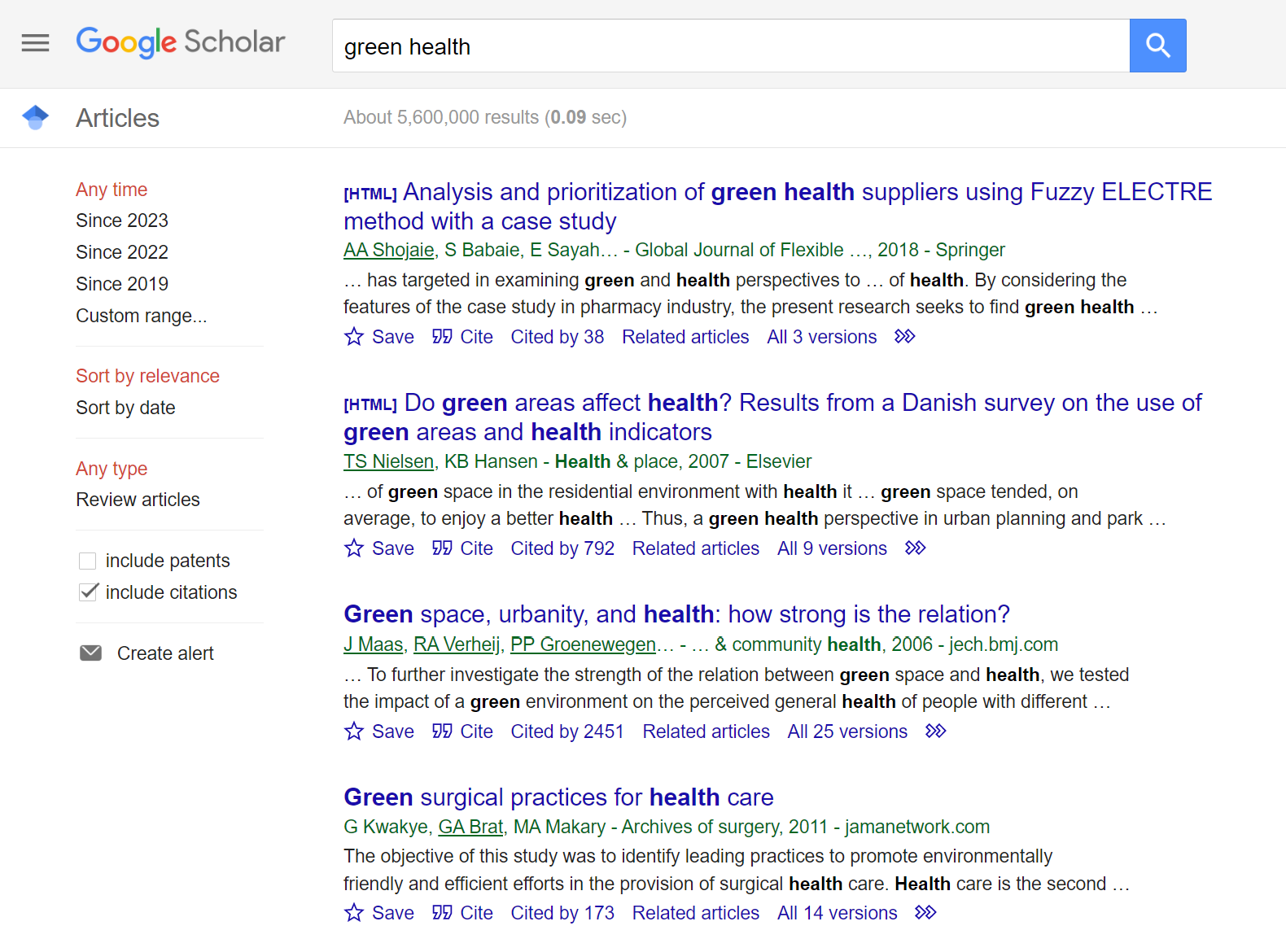

Experiment with entering the search terms into Google Scholar . For example, type the words ‘ green health ’ into the search box and press enter.

Using a simple search term like this can generate a long list of articles. In this example (Figure 10) it was somewhere around five million, which is far too many for you to review meaningfully!

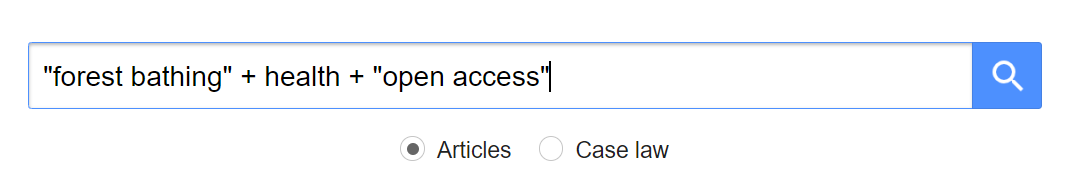

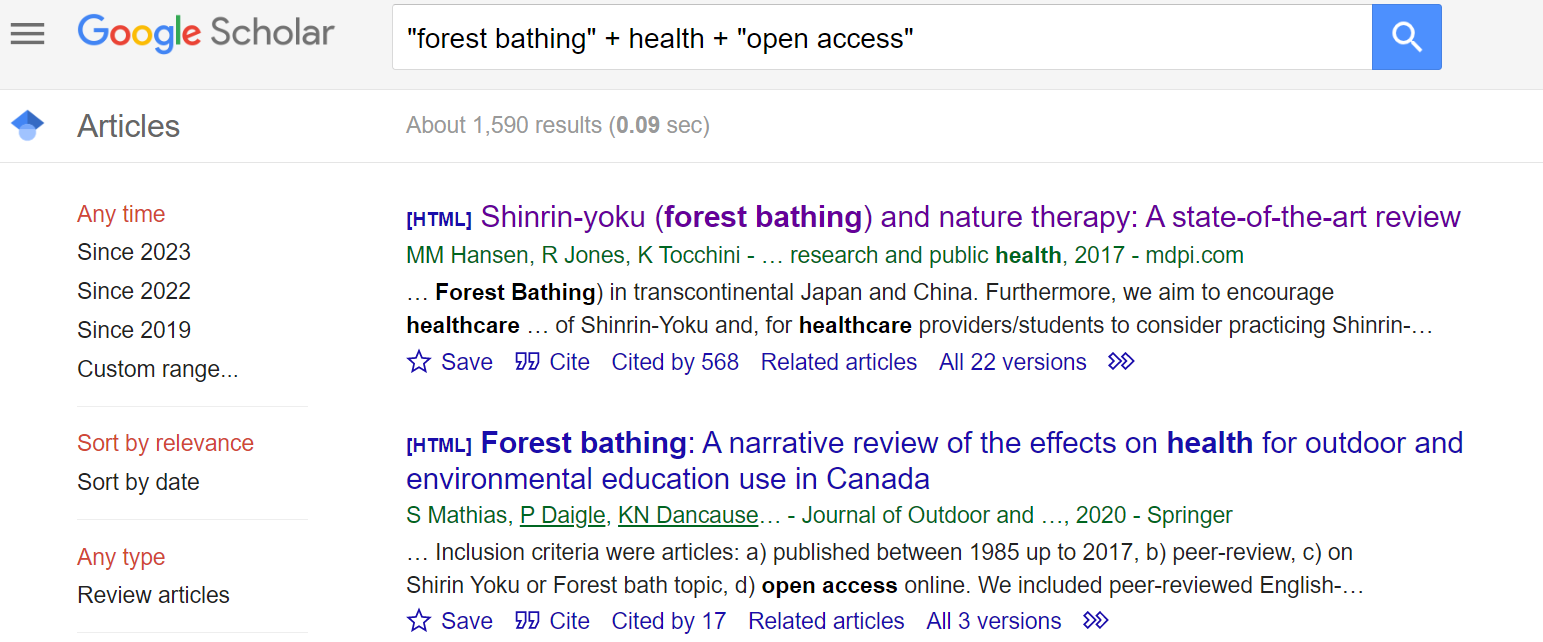

Combining search terms and using punctuation to keep two or more words together can help you focus your search and return fewer results to look through. Try typing “forest bathing” + health + ”open access” into the search bar:

Quote marks (“…”) keep words together. With quote marks (“forest bathing”) the search will return articles about forest bathing. Without them (forest bathing), you’d get articles on woodland and swimming pools (among other things!).

Using the + symbol combines “ forest bathing” AND health. Adding + “ open access ” means you will only see results where you have free access to the full article.

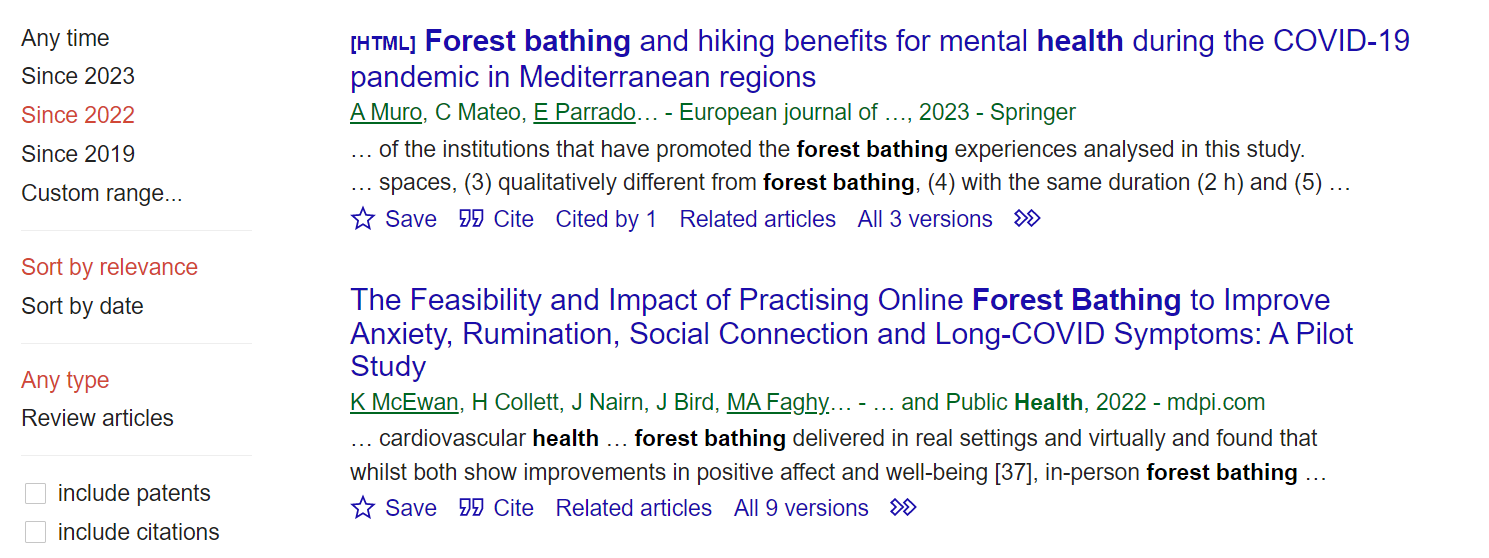

This cuts down the number of results to around 1600 (Figure 12):

You can then click on the search results to access the articles. Clicking the top link brings up an article about forest bathing (at time of writing – the top result may well have changed since then).

To refine your search even further, Google Scholar has filters you can use to tweak your search. For example, if you are only interested in very recent material, you could filter so that only material published after 2021 is shown. This is useful if you want to access material published in a particular time range.

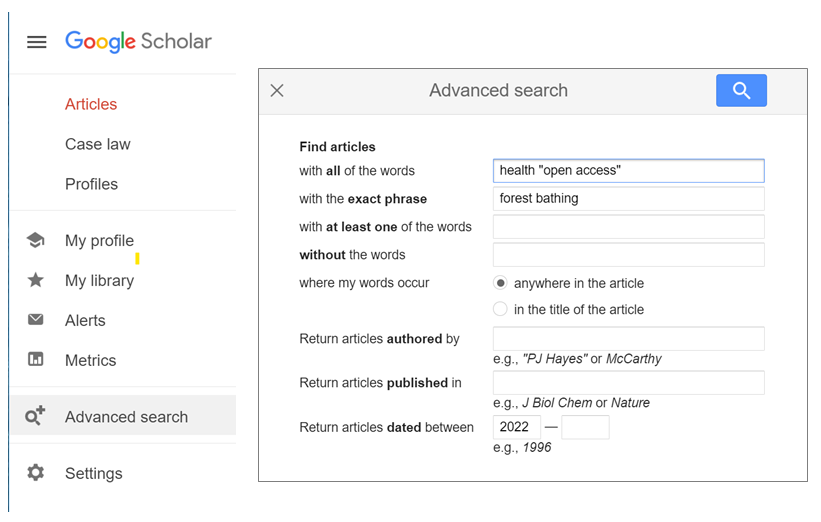

Most search engines or search facilities on repositories, collections or websites have an advanced search function that allows you to refine your search to cut down the number of results to something more useful. You can search for material published before or since a specific date, include or exclude specific words, or look for articles by a specific author.

To access advanced search on Google Scholar, click on the menu hamburger in the top left.

What is the right number of resources to include in your EPQ research?

It’s difficult to give an exact number of resources you should aim to use in your EPQ research. You could keep going for ever – new articles come from researchers in a constant stream! A rule of thumb is to stop reading when you sense you are no longer finding new ideas.

Credibility.

Even a refined search is likely to throw up lots of material from a range of sources. Wherever your material comes from, you should always scrutinise it carefully. But how do you decide what you can trust (therefore making it useful), and what you can’t?

Assessing a source’s credibility is a good place to start. Making sure you draw your evidence from credible, believable, trustworthy sources is very important for your research.

Quiz: judging credibility.

Comments on credibility of sources.

In order of least to most credible, below we explain why each source is credible or not:

- Tabloid newspaper article: this kind of reporting puts a priority on the sensational and doesn't always give a full and balanced story.

- Podcast: podcasts often present the podcaster’s personal opinion, and it’s not always obvious whether that’s based on research.

- Popular science books: authors usually draw material from a range of sources, and sometimes interview the researchers to get a first-hand view.

- New Scientist article: this magazine has a good reputation for serious science journalism, and the articles usually have links to the original research so the reader can investigate further for themselves.

- Original research paper: research papers usually give the reader the evidence that the researchers gathered, so the reader can review it for themselves.

Judging credibility – Thomas’ thoughts.

Thomas, who is a lecturer in space governance, discusses the credibility of materials. As you watch his video, listen out for the ways in which he judges credibility.

‘How do you judge the credibility of a source? That is, what questions do you ask yourself when you read or review a source?’

So this is one of the more important questions for any researcher, particularly one in the humanities such as myself. It’s also one of the hardest, especially when you’re just starting out because the honest answer is: it’s experience. I’ve learned enough about my field that I can differentiate between ‘I don’t agree with this’ and ‘this is nonsense’ but obviously that wasn’t always the case. So in the early days, in high school and undergraduate, there are a few things you can look at to get an understanding of what makes a good source. First port of call is always what your teachers and lecturers recommend, they’ve got that experience that you don’t have, so they’ll be pushing you in the right direction. Pay attention to how those sources are written, that’ll give you clues as to what makes a good source.

But how to find them on your own? Well again, when just starting out, it’s best to be conservative, to err on the side of caution, so there are a few things you can look to. First is publisher. Academic presses (like Oxford University Press) specialise in publishing scholarly work, so that acts as a form of quality filter. Author is another one. Who is this person, why are they qualified to write an article or a book on this topic? There are other indicators you can use. For example: are there footnotes, references, a bibliography? What sort of sources do they use? How up-to-date are they?

Then there’s the work itself. Is it well-structured and thought out? Do they actually make an argument? Do they explain their reasoning to you, or do they just declare things to be true? ("Well of course it’s true, I said it" – it happens more often than you would think it does!)

Finally, you need to read widely and broadly. You need to read authors you agree with, and authors that you disagree with, and then work out what you think. Gradually you’ll be able to work out what constitutes a good source without being dependent upon some of these indicators – which is good, they’re not ironclad rules; some excellent works of history have been written by people without history degrees. And more importantly, you’ll be able to discern the difference between ‘I don’t agree with this’ and ‘this is nonsense’.

Thomas’ main points

Thomas’ main points were:

- Ask people you trust, such as teachers, what they recommend.

- Look at the quality of the writing – good sources are well-written and well-structured, with evidence to back up the arguments they present.

- Go to reputable sources such as academic publishers.

- Look at the writer’s qualifications on the topic.

- Look at the sources the writer has used.

- Read lots for yourself and build your ability to judge gradually.

Judging credibility – Charlotte's thoughts.

Charlotte, who is a researcher in geochemistry, also has some thoughts about how she judges credibility.

- Thoughts from Charlotte

Figure 16 Charlotte, a researcher in geochemistry Show description A photograph of Charlotte

- the data support the conclusion the authors have come to

- the methods are appropriate and up-to-date

- they haven’t cherry-picked the best data and ignored others

- the authors don’t have any financial interest in coming to a particular conclusion.

If it’s an area she’s less familiar with, she starts with newspapers, online news and experts. She looks for:

- links to the original research

- what qualifies the writer to be an expert in that area

- whether other experts agree with the author

- any hint of conspiracy theories

- whether the authors have any financial interest in a particular conclusion.

Another colleague, Charlotte, who’s interested in extremophiles – life that lives in very extreme environments on Earth – said that for her, essentially the rule of thumb that she uses is, one: peer-reviewed research. This is a term that means that the paper, before it’s published, has been looked at by two or three colleagues who are knowledgeable in the area. They offer comments and the original authors are then able to improve what they’ve written.

Peer-reviewed research is typically what’s published in academic journals, and that’s the most credible source. Everything else; social media, newspapers, online news forums, is less credible. Charlotte says that when she is reading or researching in the field that she’s an expert in – geochemistry – she always develops her ideas using peer-reviewed academic articles, asking herself: do their data support their conclusions? Are they using the most appropriate and up-to-date methods?

Are there signs that they’re cherry-picking the best data, or ignoring data that doesn’t quite fit what they want it to be? And, super important: do the researchers have financial interests in the conclusions? You might not necessarily trust someone who was working for a toothpaste firm to give you the absolute disinterested best data on tooth decay.

However, Charlotte said that when she’s reading about a topic that’s outside her field of expertise, perhaps in something in health and medicine, she finds it much harder to read and understand the peer-reviewed literature, as sadly it will often use specialist language or jargon. Therefore, in such situations, she often uses a larger range of sources, which might well include newspapers, online news, and things written by people who have been deemed experts.

In that case, some of the questions she asks herself are things like: does the expert or the news article refer back to the original research? Is the news article or expert giving an opinion that’s backed up by a range of research? If it’s someone giving their opinion, what qualifies them to give that opinion? Is there anything about conspiracy theories? Those red flags that Thomas talked about. And again, do the authors seem to have a financial interest in the opinion that they’re pulling out? If the sources she looks at refer to specific academic articles, it makes her think that these sources may be more credible than those that don’t. And if the experts on news articles are spreading an idea that feels like conspiracy, has been widely debunked, or for which there is very limited evidence, then she doesn’t count that as a credible source.

- Similarities and differences

- Similarities

- Differences

What are the similarities and differences between how Charlotte and Thomas judge credibility? Charlotte is a science researcher, whereas Thomas is a law researcher – do you think this affects their processes?

Thomas and Charlotte both:

look at where the article has come from – a reputable source or one where work is reviewed by experts

consider the writer’s qualifications to be an expert on a subject

review whether other experts or sources agree with the writer

- check that the arguments or conclusions are supported by data.

Charlotte will look for links to the original research and any evidence of financial interests.

Thomas will look at the quality of the writing and the structure of the article.

Whether you use PROMPT, RAVEN or another method of assessing credibility, this will help you determine that you have the best sources possible for your project. Then it is time to get started reading for the literature review.

More about the PROMPT checklist

PROMPT stands for:

- P resentation: Is it clearly written, and can you follow it?

- R elevance: Does it meet your needs? Tip: for a speedy check, read the first and last sections (often called the Introduction and Conclusion) and decide whether it’s worth reading the rest.

- O bjectivity: Does the author make their position clear? Are there any ‘hidden’ interests such as advertising or sponsors?

- M ethod: Is there any information about how the work was done? For example, if the paper is about the results of a survey, do they tell you what the questions were?

- P rovenance: Where does the article come from – university? Government? News media? Someone’s personal website? How much can you trust the source?

- T imeliness: W hen was the information produced? Could it be out of date? Have ideas changed? (But remember that old is not necessarily bad; you could use older information to compare with current thinking.)

Try using the PROMPT checklist on the articles you have found.

There is more information about PROMPT on the OU’s Library Services website. Click here for a downloadable and printable version.

- Reading critically

A good research review is more than just a list of ‘she says this ... they say that … he says the other’. It’s an opportunity to test and show the strength of different arguments and the contribution they have made to your thinking.

The key is to critically read the material you have found.

The aim of critical reading is to assess the strength of the evidence and the argument. It is just as useful to conclude that a study, or an article, presents very strong evidence and a well-reasoned argument as it is to identify the studies or articles that are weak.

As you read, it is useful to keep asking yourself questions such as:

Why am I reading this? – Because it’s interesting? Useful? Has good information for me?

Do I trust the source? – What evidence do I have that the source is trustworthy?

What claims are the authors making? – Have they included their conclusions?

Do I think those claims are trustworthy? – Have the authors given me the evidence they are basing their claims on so I can judge for myself?

Imagine you were researching the question: ‘what is the influence of advertising on people’s consumption of junk food?’

Remembering that you will find material from a range of sources. Here we’ll use an article from the Guardian newspaper’s website.

What information in the article do you think would be relevant or useful to help you answer this question? Use the questions in the ‘Reading critically’ tab to help you reflect.

What did you think about as you read the article?

You might have picked up points such as:

- Why am I reading this?

- It is about the effect of advertising on people buying junk food, so it is relevant to the question.

- Do I trust the source?

- It comes from the Guardian , a well-known UK newspaper.

- The writer is named, so you could check on other things they have written – for example, if they specialise in writing articles about food or have a background in food science.

- What claims are the authors making?

- That a ban on junk food advertising has led to a reduction in purchasing of unhealthy food.

- Do I think those claims are trustworthy?

- The article mentions that the research was done by researchers at a university – you could look for them on the university website.

- One of the researchers is named and there is a quote from them.

At this stage, no one expects you to come up with all these possibilities! But keep those critical questions at the front of your mind as you search for and examine the evidence. Remember to ask:

For more ideas on how to judge the credibility of the material you find and think critically about the contents, watch this short video on critical thinking , produced by the BBC and The Open University. It discusses five key strategies you can use to sharpen your critical thinking.

In this article, we have looked at the second part of the research cycle – how to find the evidence that will help you answer your research question, and how you can start to read it critically and analyse its relevance to your question. When you have finished searching, reading and analysing, you are ready to move on to the next step: writing your dissertation.

Other articles in this series...

EPQs: designing your research question

You’ve already decided to do an EPQ, so it might seem a little odd to start this resource by asking you to consider why you want to do a research project. People do an EPQ for all sorts of reasons. Why do you want to do an EPQ?

EPQs: writing up your dissertation

You have collected and analysed your evidence and considered it in relation to your research question. The next step is to communicate all that you have done. Your dissertation is the element of the EPQ that is read and assessed by others who haven’t been involved in your research.

EPQs: why give a presentation?

What are the guidelines for the presentation?

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Wednesday, 3 May 2023

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'Photo of Julia' - Copyright: AstrobiologyOU

- Image 'Photo of Mars' - Copyright: Image by WikiImages from Pixabay

- Image 'Photo of Valles Marineris' - Copyright: Image by Alexander Antropov from Pixabay

- Image 'Devyani's mindmap' - Copyright: Devyani Gajjar, AstrobiologyOU

- Image 'Scattering of keywords printed out and cut up' - Copyright: The Open University

- Image 'An illustration depicting the research process' - Copyright: Ann Grand

- Image 'Photo of Michael, a researcher from AstrobiologyOU.' - Copyright: Michael Macey

- Image 'Photo of Charlotte' - Copyright: AstrobiologyOU

- Image 'EPQs: why give a presentation?' - Alphabet Yellow © Betta0147 | Dreamstime.com under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'EPQs: writing up your dissertation' - © Betta0147 | Dreamstime.com under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'EPQs: finding and using evidence' - Alphabet Yellow © Betta0147 | Dreamstime.com under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'EPQs: designing your research question' - © Betta0147 | Dreamstime.com under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

How To Write An EPQ Essay (Step-by-Step Guide)

In A-Level by Think Student Editor March 29, 2019 8 Comments

Whatever the reasons were for you choosing to write an EPQ, the grade you get is most definitely important to you. That is why I have written this (hopefully) detailed guide on how to write an EPQ.

1. Think Of An EPQ Topic That Genuinely Interests You

It’s important to choose an EPQ you’re interested in, or you may run into some problems . Many students take EPQs each year, and many students fail because they make this mistake.

If you don’t take an EPQ you’re interested in, you’ll have no motivation to work on it . This will be because you start to want to do other things, anything instead of your EPQ.

Think about revision, for example. Is it interesting? Nope. Would you rather be playing videogames, watching Netflix, or literally anything else? Yeah, me too.

If you’re not motivated to write your EPQ essay, then you’ll either not do it or do it badly. If you don’t work hard for it, you won’t get good marks – and therefore there’s less point in even taking it in the first place .

If you find an EPQ topic to write your essay on that genuinely peaks your interest, you’ll find it much easier to get better grades in it.

A more interesting EPQ essay topic will mean that your focus is better . This will result in a better EPQ, meaning more marks when you hand it in.

You’ll also enjoy the EPQ a lot more if you find it interesting . You’ll find the whole experience a lot more fun, and therefore a lot easier too.

To find an EPQ topic that genuinely interests you, you just have to think about what you like. There are lots of different things you can do, but you only get to choose once – so choose carefully.

And if you’re really stuck on ideas, take a look at this list of 600+ EPQ ideas that guarantee an A* . Any of these ideas will be great for your EPQ, so just choose one that interests you and that you’ll actually enjoy.

2. Create A Mind Map Surrounding Your EPQ Topic

A mind map is where you write down everything you know about a topic . In this case, you’d be writing down all the ideas and concepts surrounding your EPQ topic.

That way you can see everything you need to write about in your EPQ essay. You’re essentially making a mood board for whatever EPQ idea you’ve chosen, and it will help you get in the right mindset for the task ahead.

Mind maps are most commonly used to identify gaps in your knowledge . Students tend to use them when revising to work out what they don’t know, whilst also helping them consolidate what they do know.

In terms of your EPQ essay, a mind map will provide a loose structure for you to follow . You’ll come up with lots of different things you can write about, and that will make the essay a lot easier.

In addition to this, whilst creating your mind map you may even decide to change your topic entirely. You might find that the topic you’ve chosen isn’t giving you any idea inspiration, and so you move on to a different topic.

To make sure you get your mind maps right, you might want to follow this helpful guideline . It’s mainly about studying, but the same things can be said for planning your EPQ essay.

Don’t try rushing in to your EPQ essay without first creating a mind map . Mind maps are more useful than most students think…

Mind maps will help you avoid getting lost in what you’ve written, what you’ve missed, and what you’re planning on doing. You can use your EPQ topic mind maps as a sort of checklist as you write your EPQ essay.

3. Use Your Mind Map To Think Of A Question Related To Your Main EPQ Topic

Many students forget to think about this, but it’s probably the most important part of your EPQ . If you get this bit wrong, you can say goodbye to a good grade in your EPQ.

The question relating to your EPQ topic of choice is what you’ll spend your time working on . The 5000 words you write will be about this question, and so it really needs to be a good one.

If you don’t make it a question that interests you, then you’ll find it harder to write as much about it. Find a question that genuinely peaks your interest (relating to your EPQ of course) and the rest will come naturally.

It’s also important, however, that you choose a question where there’s a lot to write about . If you choose a question with lots to write about, you can use that to your advantage when trying to reach those 5000 words.

However, if you don’t choose a question where there’s a lot to write about, you’ll find that your EPQ is slow and drains you. Not only that, but it’ll probably be worse in terms of grade too.

I’d suggest doing a little background research into your question before you start writing your EPQ essay . Just check that there’s lots to write about and then you can avoid starting something you can’t finish.

As a general rule, you’ll want questions that don’t have definitive answers. If you can find a question that is inconclusive, you’re onto a winner.

If you can’t be bothered to look up EPQ questions, then there’s an alternative . Take a look at this list of 600+ EPQ ideas that guarantee an A* .

4. Write Down Subtitles That Relate To Your Main EPQ Question

Writing down subtitles for your EPQ question means that you’ll have a better idea of what’s actually going into your EPQ essay .

When you create your subtitles for your EPQ essay, you’re essentially writing down all the mini-topics you’ll write about. You split up the massive 5000 word count into smaller, more manageable parts.

I’d suggest making as many subtitles as you can that relate to your main EPQ question. Just go for a massive brainstorm ( potentially using your mind map ) to try and come up with lots of subtitles.

That way you maximize the chances of you making some actually good subtitles. You’ll have lots of options to choose from, and your EPQ will benefit from having such a varied range of points.

You also put yourself in the right mindset for your EPQ essay . You’ll be much more open to different ideas and approaches whilst actually writing the EPQ, and examiners will see this and give you extra credit.

However, you need to make sure that the subtitles you’re writing actually relate to your EPQ question . If they don’t, you could run into some serious problems.

If you choose to work on a subtitle that doesn’t wholly relate to your EPQ question, you risk filling up your word count with irrelevant information. That means less room for the important stuff, and less marks for you.

Make sure you check all your subtitles before you start writing . Work out what the plan is before you start writing, so that you don’t have to rewrite a large portion of your EPQ essay.

So grab a pen and paper, sit down, put on some nice music, and get to writing those subtitles.

5. Triple Check That Every Subtitle Question Actually Relates To The Main EPQ Topic

By this point, you should have around 16 subtitles that you want to include in your EPQ essay . 16 subtitles will give you a nice 300 word per subtitle guide, give or take a few.

Any more subtitles, and you run the risk of overcomplicating your EPQ. Any fewer, and you’ll struggle to reach that gargantuan 5000 word count.

It’s essential that you break down your EPQ essay into smaller modules like this, to make it easier for you in the long term. 16 subtitles will mean the best productivity for you when you actually come to write your EPQ essay .

The next step is to order your subtitles, for easier reading. You’ll want to make the layout of your subtitles as sensible and as easy to follow as possible for your examiner .

If you please your examiner like this, they’ll be more inclined to give you more marks. They mark you on your written communication, and therefore you’ll want to make sure you’re communicating the most effective way.

Try ordering your subtitles by the order of most important to least important . Laying out your subtitles this way will show your examiner that you’ve really thought about your EPQ and understand what they want to see.

Alternatively, you could lay out your subtitles chronologically . What I mean by this is that you start with your question, move onto research, then explanations, and finally a conclusion.

This is probably the best way to lay out your EPQ essay subtitles . It’s the easiest way to follow the process you went through, and examiners like to see EPQ essays that are laid out like this.

It’s how I laid my EPQ essay subtitles out, and I got an A* – so I’d suggest doing the same.

6. Allocate A Word Count To Each Element Of Your EPQ Structure

You’ll want an introductory paragraph to start with, and that should only take about 200-300 words . Don’t go overboard with your introduction, as you should aim to make the bulk of your essay about your EPQ question.

I’ve already mentioned it, but you want to write about 300 words per subtitle . This is the perfect amount of words to write if you want the EPQ essay to go as smoothly as possible.

16 subtitles at 300 words each will put you at just under 5000 words – 4800, to be exact. That will leave you just enough room to add a short introduction too.

You can go for less subtitles, but that means a higher word count for each individual subtitle . If you make your word count per subtitle too high, then you’ll struggle when it comes to actually writing your EPQ essay.

You could also try more subtitles if you want, but that then means you’d write less per subtitle . That means there’s less room for all your explanation, and less marks when you hand it in.

I’d recommend keeping your subtitle count between 14 and 18 . That way you give yourself the best chances of your EPQ being easier to write.

You also make it easier for you to enjoy, too. Making your EPQ essay subtitles this long means you’ll find it easier and less monotonous, and therefore you’ll enjoy it more.

The word count of each element in your EPQ essay has an impact on your productivity and focus, too . Generally, the shorter the piece of writing you have to do, the more productive you’ll be.

Setting yourself short-term goals like this will help you stay focused and make your EPQ that little bit better. It’s worth setting effective word counts for your EPQ essay elements for those extra marks .

7. Research, Research ( And A Little Bit More Research )

Research should make up about 40%-50% of your total EPQ essay . That’s a lot of research, and you can see from this figure that quality research is crucial to your success.

The reason research takes up so much space is because you need to explore all opportunities within your question. Research will help you develop ideas and improve your knowledge of the subject, helping you to better answer your EPQ essay question.

And besides, who doesn’t want help reaching the massive 5000 word count?

There are many ways to research, with the most common being the internet, and books . Both ways of researching are valid and useful, but you still need to be careful.

Especially with the internet, you may come across facts and information that isn’t entirely accurate. This is because anybody can access anything, and usually the information you see online is edited by people who aren’t professionals.

Try to stay away from websites like Wikipedia, where anybody can change the information you see . There are much better alternatives out there, like Google Scholar for example.

Whereas with books, they have to go through a long-winded process to ensure they’re accurate . Books tend to be slightly more reliable than the internet, especially if they have an ‘exam-board approved’ label on them.

I’d also recommend keeping track of all the sources of your information, as you’ll have to write a bibliography at the end of your EPQ .

What that basically means is that you have to reference each individual source of information after you’ve written your EPQ essay. That’s just so examiners can check to see if you’re plagiarising any content, in case you were wondering.

8. Check That Your EPQ Structure Still Makes Sense

You should have around 16 subtitles ready to go, in chronological order or order of importance . I’d suggest chronological order, but that’s up to you.

You should also have space to add an introduction and conclusion paragraphs . They shouldn’t take up too much space, but still leave some room for you to add them in.

You’ll actually want to wait until the end of your EPQ essay to write either of these paragraphs, so it might help to add placeholders until you get to writing them.

Around 7 of your subtitles should be based on research . You’ll want to leave yourself a nice amount of in-depth research, whilst also allowing room for all that explanation.

If you don’t give the right proportions for your research and explanation subtitles, your EPQ can become lopsided. Examiners will easily spot this and take away precious marks.

You’ll want your conclusion to be longer than your introduction, as you’re essentially summing up all that you’ve written . Your conclusion should be about the same size as your subtitles, but maybe just a little bit bigger.

If all else fails, just read through your structure and think about it from an examiners’ point of view. Does it all make sense? Are the subtitles in a sensible order? Have you left space for your introduction and conclusion paragraphs?

If you reckon you’ve got all these elements in the right order and the right sizes, you should be good to go. Just keep a clear focus on your EPQ essay question, and you can’t go wrong.

9 . Write Down The Answers To Each Of Your Subtitles

Start with your subtitles to get the main bulk of your EPQ essay underway . The quicker you get your subtitles done, the sooner you can finish your EPQ.

Starting your subtitles first is a good idea, as they make up most of your EPQ. You’ll want to get them done first, and then you have time after that to work on the finer details.

As I’ve said, your subtitles should be around 300 words long . This will allow you just enough space to answer the subtitle, without repeating yourself or going overboard.

If you go too far over 300 words, you risk either repeating yourself or just extending your points so much that your words become empty. Empty words = no marks, which is what you definitely don’t want.

If you don’t write 300 words, the points you make are likely to be underdeveloped. This means you can’t get into the top band of marks no matter how good what you’re saying is – there’s just simply not enough of it.

Of course, if you think you can express yourself in more or less than 300 words, go for it . Everybody’s different, and some people have better writing skills than others.

The amount of words you write per subtitle can also depend on how many subtitles you have . If you have less subtitles, you write more words per subtitle, and vice versa – simple maths.

Try to explore every possibility within your subtitle. The more routes you go down and the further the detail you go into, the more marks you’ll get from the examiner.

10 . Write The Introduction And Conclusion Paragraphs

Your introduction paragraph needs to be slightly shorter than your average subtitle paragraph . Usually about 200-300 words, the introduction will basically talk about what’s to come in your EPQ essay.

If you make your introduction too long, you waste space that you might need for your research/explanations. You also take up space that could be used for your conclusion, which is very important.

It’s a good idea to write your introduction paragraph after you’ve written all of your subtitles . It may sound odd, but there’s method to the madness.

If you write your introductory paragraph last, it’ll be a lot more accurate than if you’d have done it at the start. You’ll know exactly what’s in your EPQ, and therefore your introduction can accurately ‘introduce’ your essay .

Your conclusion paragraph should be slightly longer than your average subtitle, and definitely longer than your introduction . I’d say about 400 words, your conclusion should sum up everything you’ve talked about in your EPQ essay.

Your conclusion should essentially answer the question you asked at the start of your EPQ essay. You should aim to include everything you talked about in your other subtitles (that’s why it’s a little bit longer).

You’ll obviously want to write your conclusion paragraph after everything else, or you’ll have nothing to conclude. Once you get on to your conclusion, you’re on the home stretch.

11. Get Someone To Proof Read It To Make Sure There Are No Errors

Proof reading your EPQ essay is so, so, SO important to your success . If you don’t proof read your EPQ essay, you may miss some pretty crucial mistakes…

I’m not just talking about the spelling mistakes you may have made (although you might want to fix those too). I mean the mistakes where you contradict yourself, go off topic, or even just get your facts wrong.

I’m sure I don’t need to explain it, but these mistakes will cost you dearly when your EPQ gets examined . Sometimes just a few marks can be the difference between an A and an A*, so you need to maximize your chances of success.

A good way to ensure your EPQ essay is perfect is to get someone else to look through it. Having a second opinion ensures that everything you’ve written is accurate and concise, and it’s better than just checking through it yourself.

If you rely on your own methods of checking through your work, you’re more likely to miss mistakes . Having a fresh perspective on your work broadens the chances of catching every mistake you make.

It doesn’t matter who you get to check your work . You can ask friends, family, or even your teachers/tutor – just get it proof read before you send it off to be marked .

If you need to check through it for spelling mistakes or wording issues, there’s a handy little trick I used for my EPQ essay. Paste your entire essay into google translate, and have it read out to you .

That way you can listen and check for anything that’s not quite right, and sort it out in time for your EPQ essay to be examined.

Thanks so much for the help !

This is so, so helpful, thanks so much!

How many resources should I have for my EPQ?

20-25 should be the right number

Hi, thanks for the cool tips! I will definitely keep it for myself

Hello, thanks for the cool advice, but the most difficult thing for me is 1 point – to think through the topic itself. Therefore, already at the first stage, I give up and turn to the college essay writing service. This service helped me more than once or twice. My friends also use it. Also, it is difficult for me to create a mental map, which is in point 2. Therefore, I would rather spend my writing time on purposes that are useful to me.

This is so useful! I have been working on my EPQ over the past few weeks and have had a few big quandries about how I should go about forming an answer to my question and this has made it much clearer. Thank you!

EPQ Guide: Expressing your ideas

- The Inquiry Process

- Developing a line of inquiry

- Finding and selecting sources

- Working with ideas

Expressing your ideas

This is the stage you have been building towards - writing your report. Although that is largely the focus of this page , it is not all there is to the EPQ.

Your EPQ will be assessed on:

- Your completed Production Log

- if your project is a research based written report of any kind (e.g. a science investigation or an essay) it should be approximately 5,000 words long

- If your project is an artefact, it must be accomapanied by a research based written report of a minimum of 1,000 words. For artefacts, you may include photos showing various stages of the production process as well as the final product. You do not need to submit a large artefact as evidence - photographs or other media are fine.

- If your product was itself a presentation then you still need to produce a presentation about the process of producing it!

- Your presentation must be delivered live to a non-specialist audience and might use flipcharts or posters, presentation tools such as PowerPoint or Prezi or short video clips. The evidence for your presentation will include a record in your Production Log of questions your supervisor asked and how you responded.

Am I ready?

Am I ready to start writing my essay?

Before you start writing, think:

- Is my investigation largely complete? As you write you may find that you need a few additional resources or information to support your argument, but you should not sta rt to write until you are largely sure where your argument is going.

- Have I filled in a Research Organiser (which you will find on the Working with Ideas tab)? This will help you to organise your thoughts and make sure you understand the argument you intend to make and have the evidence to support it. While not compulsory, it makes writing your final essay significantly easier.

- Do I understand how to write in an appropriate academic style? Guidance is given in the Academic Writing box below.

- Do I know how to import my sources from my Investigative Journal? Don't waste time putting all your citation data in again! Import all your sources as you set up your document. There are helpsheets in the Resources for PC / Mac users boxes to the right.

You should use the Oakham APAv3 Academic Writing Template (below) rather than a generic Word template to set up your essay.

(The image below is taken from the EE LibGuide, but the template is just as useful for EPQs)

Citing and referencing

There are many different ways to acknowledge the sources you use. These are called referencing styles . You are free to use any recognised referencing style you wish for your EPQ, but Oakham's 'house style' is APA. We suggest you use this because we already have a lot of support in place for it. APA is an 'Author-date' system, meaning that you show which source you have used by putting the author and date in brackets after it in your text, and then put the full reference in an alphabetical list at the end of the essay. The Library does not support 'footnote referencing', where you put all the information in a footnote at the bottom of the page. If you want help with this then please talk to the member of staff who suggested that you use it.

For detailed information and guidance on how to use sources in your writing and how to cite and reference them accurately using the tools in Microsoft Word, consult the Citing and Referencing LibGuide . This site includes information about how to reference all sorts of different kinds of sources, including videos and works of art, and what to do if you are using a source written in a language that is not the language of your essay. It also gives some examples of how to use in-text citations , whether quoting, paraphrasing or just referring to a source more generally, and how to use the automatic citing and referencing tools in Word .

Academic writing

Stages in an academic essay

Your thesis is the point you want to make. It emerges from your research and your task is to use the evidence you have found to establish it as the most reasonable response to that research.

In both approaches, you must state the research question in your introduction, and make sure you return to it in your conclusion .

Sections required in your essay

Have a look at the Formal Presentation guide in the sidebar for a guide to laying out your essay.

Paragraph Structure

Paragraphs themselves have a structure - the most common you will have come across is likely to be PEEL. The letters often stand for slightly different things in different subjects, but the idea is largely the same - introduce your main idea for the paragraph ( Point ), justify it with Evidence and/or Examples , and Evaluate this evidence. Finally, Link back to the Research Question and/or Link forward to the next paragraph.

This is not the only way to write a paragraph and, with experience, you will soon find that your argument develops a flow of its own that does not require a formula - indeed, your essay would be very dull if every paragraph followed exactly the same structure. However, this structure can be a useful scaffold to get you started and make sure you don't miss anything important.

The structure of academic writing

Note that the following graphic was originally produced for the IB Extended Essay, but is equally applicable to the EPQ.

Planning your essay

It is vital to plan your essay before you start writing. An essay plan provides an outline of your argument and how it develops.

What sections and subsections do you need?

Although this might change as you write your essay, you should not start writing until you have your overall structure. Then think about roughly how you are going to divide your 5000 words between the different sections. 5000 words seems like a lot before you start writing, but it is much easier to write to the limit, section by section, than to try to cut your essay down once it is written.

What will the reader will expect to see and where?

Look back at your checklist and think about where in your essay you are planning to include the required information. Make sure the flow of your essay makes sense to a reader who may be a subject expert but knows little about your topic. Have you included background information? Details of experimental methods? Arguments and counter arguments?

Now get writing!

You've read all the guidance. You've made your plan. Now you have a blank screen in front of you and you just need to get started! Start with the section you think you will find easiest to write and work outwards from there, or follow the steps below to get started. Don't forget to write with the word limit in mind though.

What if you are writing lots of paragraphs but your essay just doesn't seem to be coming together?

1. Condense each paragraph into a short statement or bullet point. This is the skeleton structure of your essay.

2. Look at the order of the statements.

- Is the order logical?

- Does each point follow another in a sensible order?

- Do you need to change the order?

- Do you need to add paragraphs?

- Do you need to remove paragraphs?

3. Add, subtract and rearrange the paragraphs until your structure makes sense.

4. Redraft using your new paragraph order.

Image by OpenClipart-Vectors from Pixabay

Willard, D. (2003) My journey to and b eyond tenure in a secular university . Retrieved from: www.dwillard.org/articles/individual/my-journey-to-and-beyond-tenure-in-a-secular-university . Accessed: 9th May 2020

Oh no! It's too long!!

If you haven't managed to write to the word limit and are suddenly faced with cutting down an essay that is over the word limit, try these tips on concise writing from Purdue Online Writing Lab.

Use the menu on the left of this page from Purdue OWL to browse the four very practical pages on writing concisely and one on the Paramedic Method for reducing your word count.

AQA Guide to completing the Production Log: Expressing your ideas

AQA copyright notice

The presentation above contains slides from the AQA presentation Teaching slides: how to complete the production log (available from the AQA EPQ Teaching and Learning Resources website ). These slides are Copyright © 2020 AQA and its licensors. All rights reserved.

A downloadable copy of the Production Log can be found here , on the Home tab of this guide.

Formal presentation

Guides for PC users

- Citing and Referencing in Word 2016 for Windows

- Managing Sources in Word 2016 for Windows

- Creating a Table of Contents in Word 2016 for Windows

Guides for Mac users

- Managing Sources in Word 2016 for Mac

- Citing and Referencing in Word 2016 for Mac

- << Previous: Working with ideas

- Next: Reflecting >>

- Last Updated: Feb 27, 2023 2:28 PM

- URL: https://oakham-rutland.libguides.com/EPQ

Smallbone Library homepage

Search the Library Catalogue

Access our Subscription Databases

Normal term-time Library opening hours: Mon-Fri: 08:30-21:15 Sat: 08:00-16:00 Sun: 14:00-18:00 (Summer Term only)

How To Write An EPQ Essay & Dissertation (9 Steps)

Writing an EPQ essay involves several steps to ensure a well-structured and compelling piece.

Here is a 9-step guide to help you write an effective EPQ essay:

- Brainstorm EPQ topic ideas : Choose an engaging topic that interests you and is relevant to your academic or career goals.

- Conduct research : Gather information from various sources to support your arguments and provide evidence.

- Create a structure : Organise your essay with a clear introduction, main body, and conclusion. Outline the main points and arguments you will cover in each section.

- Write an introduction : Begin your essay with an introductory paragraph that introduces the topic, outlines the scope of the essay, and provides an overview of the structure 4 .

- Develop the main body : Write the main body of the essay, focusing on presenting your arguments, evidence, and analysis. Ensure each paragraph has a clear topic sentence and flows logically from one point to the next.

- Use proper referencing : Cite your sources correctly to avoid plagiarism and demonstrate your research skills.

- Write a conclusion : Summarise your main points and answer the question you posed at the beginning of the essay.

- Review and revise : Proofread your essay for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. Ensure your arguments are clear, coherent, and well-supported 1 .

- Seek feedback : Ask a teacher, tutor, or peer to review your essay and provide constructive feedback to help you improve your work

The article below is designed to help you develop a strong foundation for writing your EPQ essay by providing practical tips and guidance from an expert in the field.

You’ll learn about key elements such as structure, formatting, research methods, argumentation techniques and more so that you can craft a compelling paper that stands out from the crowd.

By following these steps, you’ll have all the tools necessary to make sure your EPQ essay stands out and meets its desired goals.

- 1 Understanding The EPQ Essay Requirements

- 2.1 Organizing Ideas

- 2.2 Outlining Content

- 3 Formatting Your Essay

- 4 Researching For Your Essay

- 5 Developing Your Argument

- 6 Crafting A Compelling Conclusion

- 7 Writing a good EPQ essay

Understanding The EPQ Essay Requirements

Navigating the world of EPQ essay writing can be intimidating, and even overwhelming at times! But never fear – with a little bit of knowledge and preparation you’ll find yourself soaring towards success.

At its core, crafting an effective EPQ essay comes down to analyzing expectations and exploring options. It’s important to take into account the specific requirements for your topic or course; many professors will have different standards that need to be met.

Once you’re clear on what needs to be accomplished, it’s time to get creative – start brainstorming ideas and looking for relevant sources that support them. Be sure to record everything as you go along so you don’t forget any key details later on in the process.

Research is essential here, but make sure not to lose sight of the bigger picture: Your paper should still reflect your unique perspective and originality. With this approach, you can create an engaging work that will stand out from the crowd — one which takes readers on a journey of exploration through freedom-filled imagination!

Structuring Your EPQ Essay

Organizing your ideas is an important part of writing an EPQ essay.

Start by making a list of the main points you want to make and then organize them into groups that fit with your argument.

Once you have your ideas organized, you can start outlining the content. This will help you create a logical flow of information and ensure that your essay is structured in a clear and concise way.

It’ll also make it easier to write the actual essay, and make sure that you haven’t skipped any important points.

Organizing Ideas

Organizing your ideas is an important part of writing a successful EPQ essay. Before you start jotting down notes or typing away on your computer, identify the sources that will be most useful in completing your project.