Policies to deal with economic crisis

A look at various economic policies to deal with an economic crisis, such as a fall in GDP.

Economic crisis could involve

- Lack of economic growth/recession

- High Unemployment

- Long-term structural deficits

- Lack of confidence in finance and consumer sector.

- Rapid devaluation

Solutions to economic crisis

- Government investment in new infrastructure (e.g. New Deal in the 1930s) helps to stimulate demand and creates jobs.

- Income tax cuts – increasing the disposable income of workers, encouraging them to spend.

- Cutting interest rates – makes borrowing cheaper and should increase the disposable income of firms and households – leading to higher spending.

- Quantitative easing – when Central Bank creates money and buys bonds to reduce bond yields and

- Helicopter money – when the central bank creates (prints) money and gives it to everyone in the economy.

- Free market supply-side policies – reducing government intervention in the economy, e.g. lower taxes

- Interventionist policies – government spending on education and training

- IMF bailout – IMF give money to stem the loss of confidence and implement structural adjustment policies, e.g. better tax collection, privatisation, price liberalisation.

- Government bailout of industries/banks. To prevent loss of confidence in financial sectors.

Example – March 2020

In March 2020, the coronavirus has caused a sharp shock to demand – leading to recessionary pressures. It has caused a plummet in the oil price and the stock market falls. Some sectors of the economy have been particularly hard hit – travel, leisure, the gig economy. It is not known whether it will prove a temporary blip or turn into a full-scale recession. What is the best response to this crisis?

- Interest rate cut – The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve have cut interest rates. This will provide some relief to businesses and homeowners (they will have lower mortgage costs). However, it is unlikely to stimulate demand or make that much difference. In a difficult climate, business won’t start investing because of a minor cut in interest rates. Many gig-economy workers will not notice the interest rate cut. In essence, the interest rate cut is outweighed by negative sentiment.

- Income tax cut . Proposed by the White House, a payroll (income) tax cut increases disposable income and in theory, may encourage spending. However, an income tax cut doesn’t help those most affected by the crisis. Those made unemployed or the self-employed who see a fall in income. Also, many householders will probably save the tax cut – because of low confidence and uncertainty.

- Helicopter Money . This involves the Central Bank creating money and giving a fixed amount to everyone. This avoids means-testing and means those badly affected will get some income. In normal circumstances, printing money causes inflation. But, at the moment, there is a greater threat from deflationary pressures.

- Higher unemployment/sickness benefits . Higher benefits for those sick or unemployed – and make it easier to claim benefits. This will make big difference to those on the fringes of the economy. It will enable them to keep spending and pay their rent. Higher benefits are disliked by those who think it creates disincentives to work.

- Expansionary fiscal policy – Higher spending on public investment can kickstart the economy. But, this is a slow policy to act.

- Rent relief/mortgage relief – – Since this may prove to be a very short-run but steep crisis, the other option is to force banks to allow those with lost income to delay paying rent/mortgage relief or the government can offer relief on tax bills and rates. This could make a difference between bankruptcy and surviving for firms on the edge after fall in demand.

To some extent, there are no policies that can prevent a slump in demand, when you get a crisis like this. But, the government can

- Mitigate the effects for those left with no income – direct payment, rent relief, tax relief

- Prevent the temporary slump turning into larger-scale recession – if the private sector cuts back investment, there is a role for both monetary and fiscal policy to provide additional demand.

Example of 2008/09 Recession

The first policy response was a cut in interest rates. In the UK, rates fell from 5% to 0.5%

In theory, lower interest rates make borrowing cheaper, and this should encourage consumption and investment. In the long term this may lead to higher growth.

However, cutting interest rates was not particularly effective in 2008/09. This was because

- Interest rates were lower but banks didn’t want to lend – there was a shortage of funds.

- Time lags involved – homeowners on fixed rate mortgages don’t notice for perhaps 2 years.

- Consumers had an inelastic response to lower rates, people didn’t want to spend because of economic climate

There was also a government bailout out for banks to prevent a loss of confidence in the financial system. This was a significant factor in preventing the crisis escalating.

Fiscal policy

In 2009 the UK, the government cut the rate of VAT to provide a fiscal stimulus.

In the US, there was a modest fiscal stimulus from the Obama administration.

The US also agreed to bailout large car firms which were at risk of going bankrupt. Bailing out car firms cost a lot, but it prevented a further rise in unemployment in the car and related industries.

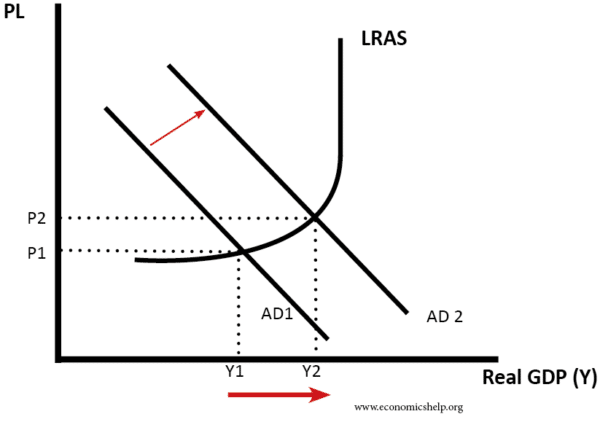

It helped mitigate the effect of falling income and provide some receovery. In theory, lower taxes should increase consumer disposable income and therefore help increase Aggregate Demand (AD).

The recovery in the US was strong than the Eurozone, where governments were more concerned about levels of government borrowing and there was no real fiscal stimulus.

The drawback of fiscal policy is that developing countries may already have large public debts and therefore they may be nervous about borrowing more. In the Eurozone this was a big factor.

Fiscal policy can also be ineffective in increasing AD, for various reasons. See: limitations of fiscal policy

Supply Side Policies

Some economic crisis arise from structural problems in the economy. For example, they may involve

- Corruption and failure to raise sufficient tax revenue

- Lack of competitiveness (e.g. rising wage costs)

- Poor productivity growth

- Low levels of education and training

In these cases, countries may not just need an increase in Aggregate demand, but also to reform the supply side of the economy to improve competitiveness. Therefore, it may be necessary to pursue policies such as:

- Education and training – increase skills and mobility of labour.

- Reduce the power of trades unions and minimum wages to reduce labour costs

- Reduce labour market protection which increases costs of labour and discourages firms from employing workers.

- Privatisation and deregulation

Devaluation

Devaluation is a policy to reduce the value of the exchange rate. This has the advantage of:

- Reducing the cost of exports and improving competitiveness

- Helping to boost export demand and therefore increase aggregate demand and economic growth.

For example, countries in the Euro-zone such as Italy, Greece and Spain have suffered from a decline in competitiveness which has contributed to lower growth and higher unemployment.

The drawback of devaluation is that it can cause inflationary pressures, but if an economy is experiencing low growth, then inflation may not be a problem.

Dealing with a debt crisis

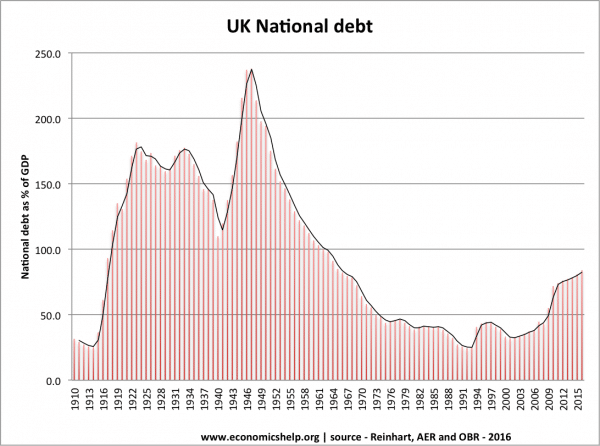

UK National debt – grew significantly during First and Second World War – long period of economic growth enabled the economy to pay off debt.

Many countries are making the mistake of trying to solve long term structural deficits, by sacrificing short term growth. In the name of long term structural change, governments are deflating the economy at a time when they should be doing the opposite.

The UK and US should be setting out plans to reduce the long term deficit, but this should not be involving short term cuts in spending on important capital investment. These long term policies should involve:

- Raising retirement age in response to an ageing population.

- Evaluating automatic health care spending in the US.

- Seeking to move people off long term benefit (e.g. helping those on disability allowance find less taxing jobs)

- Planned tax rises which are appropriate for incentives, efficiency and equality. e.g. US should be planning to raise tax on petrol, and tax on those high income earners who have befitted from recent tax cuts.

These kind of policies are sustainable and actually, make a big difference to long term budget situation. If you sell off assets or stop current capital investment projects, it is a very limited benefit to the long term budget. But, if you make changes to retirement age or entitlement spending this isn’t just a one off benefit, but a permanent improvement to the government’s fiscal position.

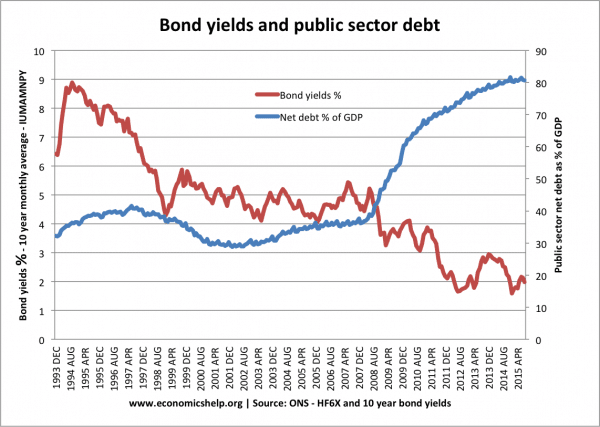

Bond yields in the UK and US are near record lows . If the government came up with plans to improve long term budget situation over next 20 years, markets would be willing to lend for short-term economic recovery.

Higher debt leads to lower bond yields (lower borrowing costs)

- Problems in recovering from recessions

- Policies to overcome recessions

What can we do to prevent another global financial crisis?

Christine Lagarde has called for a “new multilateralism” to weather the storms of the future Image: REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} David Lipton

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Financial and Monetary Systems is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, financial and monetary systems.

The global economy faces a number of complex challenges from technological change and globalization, and the lingering effects of the 2008-9 financial crisis. At the same time, we are witnessing lower levels of trust in the core institutions that have helped to deliver tremendous growth and prosperity over the past 40 years. These developments threaten to fragment the international order that has governed the global economy.

The symptoms of this fragmentation include rising trade tensions, discord with and within some multilateral institutions, and a dilution of efforts to address the profound cross-border challenges of the 21st century, such as climate change, cyber-crime, and refugee flows. The question inevitably arises: if this is occurring at a time of solid global growth and relative financial stability, what might the next economic downturn produce?

History suggests such a downturn is somewhere over the horizon, and recent signs of slowing global growth should underline the imperative to prepare for unexpected developments.

The distrust of institutions is not confined to the multilateral realm. National governance has in many respects fallen into disrepute – witness the turmoil resulting from recent elections in many countries. If we are to forestall the next economic downturn, and mitigate the impact when it arrives, countries need to shore up their defenses now.

These defenses comprise financial firepower, policies to fight crises and regulatory regimes, many put in place after the global financial crisis. However, as matters stand now, there is no guarantee that they will be sufficient to keep a “garden variety” recession from becoming another full-blown systemic crisis.

On monetary policy, there is considerable discussion about how central banks can respond to a deep or prolonged downturn. For example, past US recessions have been met with 500 basis points or more of Federal Reserve easing, and in the global financial crisis, the central banks used their balance sheet extensively. However, with policy rates still so low in so many countries and balance sheet normalization still underway, that same policy response may not be available.

Some suggest that unconventional monetary measures may provide the scope to respond to a crisis through negative rates, forward guidance pledges to hold rates at lower levels longer than justified by inflation targets or policy rules, or other innovations. But with the effectiveness of these ideas at best uncertain, there is reason for concern about the potency of monetary policy.

The next line of defense is fiscal policy, where many observers insist that the room for maneuver has been narrowing in the advanced economies. Public debt has risen – notably in the US in the wake of tax cuts and spending increases. Indeed, in many countries, deficits remain too high to stabilize or reduce debt. At the same time, if the next slowdown creates unemployment and economic slack, we should expect the multipliers to grow. That would restore some potency to fiscal policy, even at high debt levels. However, we should not expect governments to have the room in their budgets to respond as they did 10 years ago. With high sovereign debt levels, fiscal stimulus may be a hard sell politically.

One lingering resentment growing out of the global financial crisis was the perception that bankers were saved at the expense of the average worker. As a result, a future recession that endangers the finances of small businesses or homeowners would likely lead to calls to help relieve debt burdens. Supporting a larger share of the economy could further stress already stretched public finances, but failing to do so could deepen political divides.

If recession once again threatens the stability of banks, the recourse to bailouts is now limited in law, following financial regulatory reforms that call for bail-ins of owners and lenders. But those new systems remain underfunded and untested.

We should not lose sight of the fact that the impairment of key US capital markets during the global financial crisis, which might have produced crippling spillovers across the globe, was robustly contained by unorthodox central bank actions supported by backstop funding from national treasuries. The capacity to do so again also is unlikely to be readily available.

The point is that national policy options and public financial resources may be much more constrained than in the past. The right lesson to take from that possibility is for each country to be much more careful to sustain growth, to limit vulnerabilities and to prepare for whatever may come.

Another takeaway is the importance of multilateral preparedness and action. Institutions like the IMF have played a crucial role in responding to crises and keeping the global economy on track. The ability to respond effectively to these challenges has required a constant process of reform that needs to continue.

In the face of the discontent with multilateralism in some advanced economies, it is essential for the process of IMF evolution to continue – across the range of lending, analytical and research activities – so that we continue to meet our core mission of supporting global growth and financial stability. This will become all the more important if national policy tools prove insufficient to meet a crisis.

The IMF’s lending capacity was increased during the global financial crisis to about $1 trillion – a forceful response from our membership at a time of dire need. From that point of view, it was encouraging that the G20, at the November meeting in Buenos Aires, restated its commitment to support the global financial safety net, with a strong and adequately financed IMF at its center.

IMF managing director Christine Lagarde has called for a “new multilateralism”, one that is dedicated to improving the lives of all this world’s citizens and ensures that the economic benefits of globalization and technology are shared much more broadly. This is an essential goal, and one element is to ensure that we can prevent future crises – and respond effectively to the next recession. This is a practical and pragmatic way to overcome distrust in institutions and build a shared and prosperous future.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Economic Growth .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

UK leaves recession with fastest growth in 3 years, and other economics stories to read

Kate Whiting

May 10, 2024

How a pair of reading glasses could increase your income

Emma Charlton

May 8, 2024

Why shifting from prediction to foresight can help us plan for future disruption

Roger Spitz

May 3, 2024

5 ways businesses can help to alleviate poverty

Sreevas Sahasranamam and Vivek Soundararajan

The state of world prosperity: 4 key data points you need to understand

Wolfgang Fengler and Homi Kharas

Money matters: Your guide to financial literacy

Meagan Andrews and Haleh Nazeri

- The Econofact Network

- EF for Educators

- In the News

- Immigration

- Environment

- Fiscal Policy

- EF Explains

- Econofact Chats

- EF Roundtable

How do Economic Crises End?

We are now in the acute economic phase of a crisis that is unprecedented in modern times — a health crisis from the coronavirus pandemic that has sparked a follow-on economic crisis . The virus represents both a supply shock (as people are forced not to work and supply chains are disrupted by the need for social distancing) and a demand shock (as incomes plunge, people are unable to go out, and economic uncertainty surges). Moreover, these shocks have put severe strains on the financial system. Against this backdrop, the economic outlook has darkened considerably since the pandemic burst into public view, and many macro forecasters now expect a deep and painful recession as economic activity is abruptly curtailed. While much remains unknown about the spread and severity of the coronavirus crisis, and even though there are clear differences from the current situation, we can look at two past economic crises — the Financial Crisis and the Great Depression — to draw lessons. History suggests that two ingredients are needed to stanch the acute phase of an economic crisis; a transparent resolution of the underlying cause of the crisis and a dramatic economic policy response that both mitigates the economic damage and causes a shift in business and consumer sentiment.

History suggests two ingredients are needed to stanch the acute phase of an economic crisis; a resolution of the underlying cause and a dramatic economic policy response that mitigates the economic damage and causes a shift in sentiment.

- The Great Depression began with a financial panic that was ignited by the stock market collapse in October 1929. That panic quickly led to a run on banks and many bank failures. Indeed, the number of banks operating in the United States at the end of 1933 was down by almost half from its total in 1929 . In turn, the economy turned down sharply, with real GDP falling more than 25 percent between 1929 and 1933 .

- The economic policy response at the outset of the Great Depression was muted. Little fiscal stimulus was put in place, and the Federal Reserve allowed the money supply to contract precipitously. This ended when President Franklin Roosevelt took office in March 1933. One of his first acts was to declare a bank holiday that required all banks to close temporarily. During the holiday, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act that, among other things, introduced deposit insurance. Those steps brought the banking crisis to an end. At about the same time, the economy turned up, with Industrial Production picking up in April (just one month after the bank holiday) and real GDP began rising starting in 1934 (only annual data for GDP available before 1947). The economy began to recover once the underlying problem of the banking crisis was addressed but, unfortunately, this did not occur until 1933. Delay proved very costly, and this experience informed subsequent policy responses, including the immediate response to the financial meltdown in September 2008 .

- The Financial and Economic Crisis that emerged in 2007 and became acute in the autumn of 2008 had its origins in the vulnerabilities arising from housing finance and the financial engineering built on these assets. A primary trigger of the Financial Crisis related to subprime mortgages and the complex and opaque securities created to support the financing of those mortgages. As the bubble in house prices burst, the value of these securities came into question and by September of 2008 the solvency and liquidity of many financial institutions holding those securities came into question as well. The financial panic in the wake of the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 served as a trigger for the most acute phase of the crisis as financial markets seized up in the midst of great uncertainty about the solvency of financial institutions due to the extensive and opaque web of connections among banks and lending institutions.

- In the wake of the Lehman collapse, the economy spiraled down. Real GDP fell at an annual rate of more than 8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008. Private nonfarm employment plunged by more than 700,00 in both November and December of that year. The economy was in recession for a total of 6 quarters — the longest recession since the Second World War — and the unemployment rate remained above 6 percent until the fall of 2014. The collapse of Lehman Brothers and the resulting financial meltdown quickly spread across the world to other advanced economies. Governments acted in concert to address this.

- There were two key aspects to the U.S. response: massive economic policy intervention and a dramatic demonstration that the underlying problem (fear of insolvency of big financial institutions) was under control. The economic policy intervention had many components. Congress passed the Troubled Asset Relief Program (known as TARP) in October of 2008, making $700 billion available to support financial institutions. The Federal Reserve dropped the federal funds rate — the short-term interest rate it controls — to near zero in an effort to make credit as cheap as possible, purchased massive amounts of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to provide liquidity and put downward pressure on longer-term borrowing costs, and created numerous special programs that provided targeted credit to struggling segments of the financial markets. In February 2009, Congress approved a huge economic stimulus program that included about $800 billion of new spending and tax cuts.

- Bank Stress Tests in May 2009 bolstered confidence in the health of United States financial institutions. To reveal and publicize information about the health of major financial institutions, the Federal Reserve instituted the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (more commonly known as Stress Tests) in 2009. These tests were designed to establish how banks would fare under adverse scenarios in which economic and financial condition worsened significantly. The results of the first Stress Test were released in May 2009, and they demonstrated that major financial institutions had sufficient capital to weather a bad storm. Unfortunately, similar efforts in Europe failed to offer the same results because the tests there were seen as less credible (no banks failed the stress tests in Europe).

- The economy began to recover in the wake of these efforts. With massive economic policy intervention and transparent evidence that the financial institutions were on sounder footing, the economy turned up and began a long and slow recovery, with real GDP growth turning positive in the third quarter of 2009. Consumer and business sentiment also began to recover, with the Michigan Survey of Consumer Sentiment turning up noticeably in the second half of 2009 .

- There are important differences between the economic fallout from the coronavirus crisis and these earlier crises. Because the current crisis did not originate in financial markets but from a virus, the resolution of the underlying cause depends primarily on public health and medical responses. Moreover, taking steps to alleviate the health crisis, through social distancing, exacerbates the economic crisis. These differences make the response to the acute phase of the economic crisis more challenging. As has been widely noted , efforts to stimulate demand are not helpful in a time when many people are sheltering at home. That being said, government spending can still play a crucial role in confronting the economic fallout. Efforts to slow the pandemic are slashing incomes for many workers and revenues for many businesses. Providing substantial income support to these groups will serve as a financial lifeline to those facing especially dire consequences in the short run. This support will also help sustain businesses that would otherwise be viable but for the precipitous drop in revenue.

What this Means:

The need to respond forcefully to the current economic shock, which is not identical to the precipitating shocks in 1929 and 2008, is nonetheless vital. The economic fallout from this pandemic cannot be resolved fully until the pandemic itself comes under control. But the acute phase of the economic crisis must be addressed immediately. History suggests that successfully ending the acute stage will demand big, bold, and timely economic policy responses.

Unemployment Insurance Fixes to Address the Coronavirus Fallout

Related content, what information does the yield curve yield (updated).

by Michael Klein

Fed Policy: Is it Time to Take Away the Punch Bowl? (UPDATE)

by Kenneth Kuttner

What Can the Employment Report Tell Us?

by Karen Dynan and Miriam Wasserman

How Low Can We Go? Prospects for Negative Interest Rates

Why is inflation so low, responsiveness of the safety net during downturns: lessons from the great recession.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Dear Life Kit

- Life Skills

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

How to deal with money struggles during a financial crisis

Jannese Torres-Rodriguez

Explore Life Kit

This story comes from Life Kit , NPR's podcast to help make life better — covering everything from exercise to raising kids to making friends. For more, sign up for the newsletter .

Navigating a financial crisis can be overwhelming. How do you decide what expenses should be prioritized? Should you tap into your retirement accounts? What about asking friends or family for financial help? Should you apply for a payday loan?

The first step of creating your emergency plan is understanding your essential needs. "Traditionally, financial experts say, 'Try to pay all your bills, pay them on time.' And we just drill that into people's heads until they lose their job." says personal finance columnist Michelle Singletary."When you don't have enough income, you just pay for what you need, a roof over your head and food on a table."

Her new book, What To Do With Your Money When Crisis Hits: A Survival Guide , is an emergency field guide for your money. It's intended to help you tackle the issues you'd likely face in the event of a job or income loss, which many people experienced during the ongoing pandemic.

"There are plenty of great personal finance books out there," says Singletary. "But when you're in the middle of a crisis, when you're trying to figure out what to pay, you're not going to grab a book on retirement savings and read it, you know, 200 pages of that."

In the book, Singletary also explains her approach to managing money like she's in a perpetual recession. It's not so much about living in fear but more about being prepared to face financial crises at all times. "I have to always be prepared for the worst and hope for the best," she says.

Life Kit spoke with Singletary about her new book and advice on navigating financial crises. Highlights from our conversation are below, edited for brevity and clarity.

Jannese Torres-Rodriguez: One of the first places that people might turn to for financial support is friends and family. When is the right time to ask for a loan versus a financial gift?

Michelle Singletary: There is never a right time to ask for a loan. If you're in a financial crisis, go to the people who love you and care for you and say, "I've lost my job. I don't know when I can pay you back. I don't want to make a promise that I'm going to break and hurt our relationship." I think you, people will be surprised at the number of folks in their life that would be absolutely willing to help.

Emotions, Money, And What It Means To Be 'Financially Whole'

What is the best way to respond when someone asks you for financial help?

If you find yourself on this side of the conversation, relieve people of that need to pay you back. Whenever anybody approaches me, I say right away, "this is not a loan." If I write them a check, I write on the memo line in capital letters, NOT A LOAN. Just as a reminder to them that it's OK that you came to me. I had the resources. I wouldn't give you what I can't afford. I release them of that obligation and we never speak about it again. If you're going to help someone, don't keep bringing it up, because if you do, the person feels like they have to pay you back. So just don't say anything.

If You're Drowning In Debt, There's A Way Out

People might be tempted to turn to predatory lending options like payday loans or title loans. Why should we avoid these at all costs?

Payday loans are loans that are given to people based on their next paycheck. Title loans use your vehicle's title as collateral to guarantee the loan. What happens in that situation is say you've got a car that's worth $5,000 and you borrow $500, but you default on that? Now they take your $5,000 for that $500 loan.

Title loans are particularly dangerous for two reasons. One, when you look at the fees and you annualize those fees and turn them into an interest rate, you will see that those fees translate to interest rates of anywhere from 300 percent to 1000 percent. If you were in trouble and someone said, "Hey, I'm going to lend you money at 300 percent," you wouldn't do it. Two, if you're in a jam and you don't have enough money now, you're pledging money from your next paycheck, you're already behind. How are you going to catch up? Studies show that many people end up in a debt cycle with these loans.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by NPR(@npr)

What are your thoughts on taking 401k loans or early withdrawals from your retirement accounts in order to make ends meet?

In the book, I talk about where to go before you reach that point. But if you've tapped everybody that you could or there is nobody to tap, if you have no savings, then that is a source of money that you can tap. It's not ideal. I'd hope and pray that you don't have to do it. But if you do, go ahead and do it, because sometimes you gotta do what you got to do. Now, don't take a lot of the money. Take it little by little as you need it.

Can you walk us through the order of succession when it comes to who you should be talking to, what resources you should be accessing when you're in a financial crisis?

First, go through all of your savings — all of it. That's why it's there. Then, go to friends and family and ask them to help you out. Many churches, synagogues and religious organizations have funds that they set aside for members in need. Tap into state and federal funds, apply for unemployment benefits if necessary, apply for welfare, Medicaid. Use those resources. That's why they're there. If none of that is available, then you can tap your retirement funds. It's going to cost you. But it's there.

Spend Savvier, Save Smarter: 5 Tips To Stop Stress-Spending

I think there's a lot of confusion around whether an emergency fund is enough as far as savings go. How many types of savings accounts should people have in order to be able to adequately deal with emergencies?

I like to have my money in different savings "pots." It is a way to organize my savings and also prevent me from tapping money that I shouldn't be tapping. I have something called a "Life happens pot," which is different from the emergency fund. "Life happens" is the pot of money for when life happens, like your car breaks down. That's the pot that you reach for in those situations, because a lot of times, people don't have the emergency funds when they get in a crisis because they've been dipping into it.

People are always asking me, "I've got all this money, but it just is not earning anything." That's not that money's purpose. Don't worry about that. Its job is to be there risk-free. I make sure that I'm investing and getting growth in my other "pots" of money like my retirement account and my children's college fund.

How To Save For Your Kid's College Education

What are common financial scams that we should look out for?

In many communities, particularly minority communities, there are Ponzi and pyramid schemes like the sou-sou, which is a savings technique that many immigrants use where people pool their money and somebody gets the pot of savings every month. Now, people have used that to create these pyramid schemes where, say, you put in five hundred and they promise you four thousand dollars. If they say "I can guarantee you return," you are about to be scammed. Scammers know that people feel like they're behind the curve. They know that people are anxious to grow their money. They know that people are behind in savings. And so they're eager to find a quick fix, a quick way to make money. And they play on that. They play on your trust.

It's A Good Time To Save More. Here's How

Do you have any final words of advice?

I don't want you to feel guilty. I want you to feel energized. I want you to feel motivated. Don't just say, "Oh, that's right," and then go back and do the same thing. Take it slow. I'm telling you a whole bunch of stuff that requires a lot of money and discipline. Once you develop that habit, when you start to make money or you get back on track, then it'll become easier, because you have more money at hand. All of us will encounter some sort of financial emergency. And if you're prepared next time around, you can find yourself in a much better situation.

The audio portion of this episode was produced by Clare Marie Schneider. Engineering support was provided by Patrick Murray.

We'd love to hear from you. If you have a good life hack, leave us a voicemail at 202-216-9823, or email us at [email protected]. Your tip could appear in an upcoming episode.

If you love Life Kit and want more, subscribe to our newsletter .

- Life Kit: Money

Helping Countries Cope with Multiple Crises

Photo credit: Shutterstock

This year’s Spring Meetings of the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund took place at a time of overlapping global crises. The war in Ukraine has compounded concerns about inflation, COVID-19, climate change, and debt, with many other countries also facing fragility and conflict.

The chair’s statement issued on Friday by the Development Committee, a ministerial-level forum that represents 189 member countries of the two organizations, noted that the impacts will be felt most in low- and middle-income countries, especially by their most vulnerable people, including women and children. The statement added that economic recovery is at risk amid geopolitical tensions, with investment, trade, and growth affected, even as countries face further risks from the pandemic and uneven deployment of vaccines.

While the war and its repercussions were top of mind, the Spring Meetings also convened a series of public events to advance dialogue on major, ongoing development challenges. Policy makers, experts, influencers, and other key stakeholders discussed digital development, climate action, trade and subsidies, fragility, debt, and human capital. Among key takeaways from the meetings :

- Digital technologies are transforming many jobs and services ; they can help enable long-term growth and prosperity, as well as build resilience to crises. But many people in developing countries remain unconnected or are not yet benefiting. A collective commitment from the public and private sectors is needed to close the gaps and build an equitable digital economy for all.

- To address both climate change and development , we need to move from high-level commitments to real, tangible action, including large-scale investments that support a low-carbon transition and build resilience.

- Fragile and conflict-affected economies need investment and a vibrant private sector to create jobs, generate economic growth, and build infrastructure. Forced displacement is a global crisis, but inclusive policies and investment can enable refugees to help bring about social and economic prosperity.

- To make debt work for development , we must allow for rapid debt restructuring; support medium-term reductions in unsustainable debt burdens; and create better practices so that future borrowing is sustainable, with stronger transparency and accountability for debt contracts.

- Countries have been innovative in building and protecting human capital – the knowledge, skills, and health that people need to achieve their potential – even as COVID-19 has reversed many of their gains. Sustained political commitment and financing is needed to shore up human capital and support stronger, more inclusive growth.

In his Warsaw speech , Malpass urged countries to take action to avert a global food crisis, to keep markets open, and to encourage investment inflows. He stressed that countries need to broaden the investment base and avoid concentrating wealth and income in narrow segments of the population. He also noted that ensuring security and stability involves constant effort to strengthen institutions, reduce inequality, and raise living standards. In concluding, he emphasized that World Bank Group is a committed partner in these efforts: “You should count on us, as we count on you to support innovative approaches to the front lines of development. It is here that we can win the battles against the multiple crises we are facing.”

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

IMAGES

VIDEO