Case report

Case reports submitted to BMC Veterinary Research should make a contribution to medical knowledge and must have educational value or highlight the need for a change in clinical practice or diagnostic/prognostic approaches. We will not consider reports on topics that have already been well characterised or where other, similar, cases have already been published.

BMC Veterinary Research will not consider case reports describing preventive or therapeutic interventions, as these generally require stronger evidence.

BMC Veterinary Research welcomes well-described and novel reports of cases that include the following:

• Unreported or unusual side effects or adverse interactions involving medications.

• Unexpected or unusual presentations of a disease.

• New associations or variations in disease processes.

• Presentations, diagnoses and/or management of new and emerging diseases.

• An unexpected association between diseases or symptoms.

• An unexpected event in the course of observing or treating an animal.

• Findings that shed new light on the possible pathogenesis of a disease or an adverse effect.

Authors must describe how the case report is rare or unusual as well as its educational and/or scientific merits in the covering letter that will accompany the submission of the manuscript. Case report submissions will be assessed by the Editors and will be sent for peer review if considered appropriate for the journal.

Case reports should include relevant positive and negative findings from history, examination and investigation, and can include clinical photographs. Case reports should include an up-to-date review of all previous cases in the field.

BMC Veterinary Research strongly supports open research, including transparency and openness in reporting. Further details of our Data availability policy can be found on the journal's About page.

Preparing your manuscript

The information below details the section headings that you should include in your manuscript and what information should be within each section.

Please note that your manuscript must include a 'Declarations' section including all of the subheadings (please see below for more information).

Title page

The title page should:

- "A versus B in the treatment of C: a randomized controlled trial", "X is a risk factor for Y: a case control study", "What is the impact of factor X on subject Y: A systematic review, A case report etc."

- or, for non-clinical or non-research studies: a description of what the article reports

- if a collaboration group should be listed as an author, please list the Group name as an author. If you would like the names of the individual members of the Group to be searchable through their individual PubMed records, please include this information in the “Acknowledgements” section in accordance with the instructions below

- Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT , do not currently satisfy our authorship criteria . Notably an attribution of authorship carries with it accountability for the work, which cannot be effectively applied to LLMs. Use of an LLM should be properly documented in the Methods section (and if a Methods section is not available, in a suitable alternative part) of the manuscript

- indicate the corresponding author

The Abstract should not exceed 350 words. Please minimize the use of abbreviations and do not cite references in the abstract. The abstract must include the following separate sections:

- Background: why the case should be reported and its novelty

- Case presentation: a brief description of the patient’s clinical and demographic details, the diagnosis, any interventions and the outcomes

- Conclusions: a brief summary of the clinical impact or potential implications of the case report

Keywords

Three to ten keywords representing the main content of the article.

The Background section should explain the background to the case report or study, its aims, a summary of the existing literature.

Case presentation

This section should include a description of the patient’s relevant demographic details, medical history, symptoms and signs, treatment or intervention, outcomes and any other significant details.

Discussion and Conclusions

This should discuss the relevant existing literature and should state clearly the main conclusions, including an explanation of their relevance or importance to the field.

List of abbreviations

If abbreviations are used in the text they should be defined in the text at first use, and a list of abbreviations should be provided.

Declarations

All manuscripts must contain the following sections under the heading 'Declarations':

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication, availability of data and materials, competing interests, authors' contributions, acknowledgements.

- Authors' information (optional)

Please see below for details on the information to be included in these sections.

If any of the sections are not relevant to your manuscript, please include the heading and write 'Not applicable' for that section.

Manuscripts reporting studies involving human participants, human data or human tissue must:

- include a statement on ethics approval and consent (even where the need for approval was waived)

- include the name of the ethics committee that approved the study and the committee’s reference number if appropriate

Studies involving animals must include a statement on ethics approval and for experimental studies involving client-owned animals, authors must also include a statement on informed consent from the client or owner.

See our editorial policies for more information.

If your manuscript does not report on or involve the use of any animal or human data or tissue, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

If your manuscript contains any individual person’s data in any form (including any individual details, images or videos), consent for publication must be obtained from that person, or in the case of children, their parent or legal guardian. All presentations of case reports must have consent for publication.

You can use your institutional consent form or our consent form if you prefer. You should not send the form to us on submission, but we may request to see a copy at any stage (including after publication).

See our editorial policies for more information on consent for publication.

If your manuscript does not contain data from any individual person, please state “Not applicable” in this section.

All manuscripts must include an ‘Availability of data and materials’ statement. Data availability statements should include information on where data supporting the results reported in the article can be found including, where applicable, hyperlinks to publicly archived datasets analysed or generated during the study. By data we mean the minimal dataset that would be necessary to interpret, replicate and build upon the findings reported in the article. We recognise it is not always possible to share research data publicly, for instance when individual privacy could be compromised, and in such instances data availability should still be stated in the manuscript along with any conditions for access.

Authors are also encouraged to preserve search strings on searchRxiv https://searchrxiv.org/ , an archive to support researchers to report, store and share their searches consistently and to enable them to review and re-use existing searches. searchRxiv enables researchers to obtain a digital object identifier (DOI) for their search, allowing it to be cited.

Data availability statements can take one of the following forms (or a combination of more than one if required for multiple datasets):

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]

- The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

- The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

- Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- The data that support the findings of this study are available from [third party name] but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [third party name].

- Not applicable. If your manuscript does not contain any data, please state 'Not applicable' in this section.

More examples of template data availability statements, which include examples of openly available and restricted access datasets, are available here .

BioMed Central strongly encourages the citation of any publicly available data on which the conclusions of the paper rely in the manuscript. Data citations should include a persistent identifier (such as a DOI) and should ideally be included in the reference list. Citations of datasets, when they appear in the reference list, should include the minimum information recommended by DataCite and follow journal style. Dataset identifiers including DOIs should be expressed as full URLs. For example:

Hao Z, AghaKouchak A, Nakhjiri N, Farahmand A. Global integrated drought monitoring and prediction system (GIDMaPS) data sets. figshare. 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.853801

With the corresponding text in the Availability of data and materials statement:

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the [NAME] repository, [PERSISTENT WEB LINK TO DATASETS]. [Reference number]

If you wish to co-submit a data note describing your data to be published in BMC Research Notes , you can do so by visiting our submission portal . Data notes support open data and help authors to comply with funder policies on data sharing. Co-published data notes will be linked to the research article the data support ( example ).

All financial and non-financial competing interests must be declared in this section.

See our editorial policies for a full explanation of competing interests. If you are unsure whether you or any of your co-authors have a competing interest please contact the editorial office.

Please use the authors initials to refer to each authors' competing interests in this section.

If you do not have any competing interests, please state "The authors declare that they have no competing interests" in this section.

All sources of funding for the research reported should be declared. If the funder has a specific role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript, this should be declared.

The individual contributions of authors to the manuscript should be specified in this section. Guidance and criteria for authorship can be found in our editorial policies .

Please use initials to refer to each author's contribution in this section, for example: "FC analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the hematological disease and the transplant. RH performed the histological examination of the kidney, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript."

Please acknowledge anyone who contributed towards the article who does not meet the criteria for authorship including anyone who provided professional writing services or materials.

Authors should obtain permission to acknowledge from all those mentioned in the Acknowledgements section.

See our editorial policies for a full explanation of acknowledgements and authorship criteria.

If you do not have anyone to acknowledge, please write "Not applicable" in this section.

Group authorship (for manuscripts involving a collaboration group): if you would like the names of the individual members of a collaboration Group to be searchable through their individual PubMed records, please ensure that the title of the collaboration Group is included on the title page and in the submission system and also include collaborating author names as the last paragraph of the “Acknowledgements” section. Please add authors in the format First Name, Middle initial(s) (optional), Last Name. You can add institution or country information for each author if you wish, but this should be consistent across all authors.

Please note that individual names may not be present in the PubMed record at the time a published article is initially included in PubMed as it takes PubMed additional time to code this information.

Authors' information

This section is optional.

You may choose to use this section to include any relevant information about the author(s) that may aid the reader's interpretation of the article, and understand the standpoint of the author(s). This may include details about the authors' qualifications, current positions they hold at institutions or societies, or any other relevant background information. Please refer to authors using their initials. Note this section should not be used to describe any competing interests.

Footnotes can be used to give additional information, which may include the citation of a reference included in the reference list. They should not consist solely of a reference citation, and they should never include the bibliographic details of a reference. They should also not contain any figures or tables.

Footnotes to the text are numbered consecutively; those to tables should be indicated by superscript lower-case letters (or asterisks for significance values and other statistical data). Footnotes to the title or the authors of the article are not given reference symbols.

Always use footnotes instead of endnotes.

Examples of the Vancouver reference style are shown below.

See our editorial policies for author guidance on good citation practice

Web links and URLs: All web links and URLs, including links to the authors' own websites, should be given a reference number and included in the reference list rather than within the text of the manuscript. They should be provided in full, including both the title of the site and the URL, as well as the date the site was accessed, in the following format: The Mouse Tumor Biology Database. http://tumor.informatics.jax.org/mtbwi/index.do . Accessed 20 May 2013. If an author or group of authors can clearly be associated with a web link, such as for weblogs, then they should be included in the reference.

Example reference style:

Article within a journal

Smith JJ. The world of science. Am J Sci. 1999;36:234-5.

Article within a journal (no page numbers)

Rohrmann S, Overvad K, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Jakobsen MU, Egeberg R, Tjønneland A, et al. Meat consumption and mortality - results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. BMC Medicine. 2013;11:63.

Article within a journal by DOI

Slifka MK, Whitton JL. Clinical implications of dysregulated cytokine production. Dig J Mol Med. 2000; doi:10.1007/s801090000086.

Article within a journal supplement

Frumin AM, Nussbaum J, Esposito M. Functional asplenia: demonstration of splenic activity by bone marrow scan. Blood 1979;59 Suppl 1:26-32.

Book chapter, or an article within a book

Wyllie AH, Kerr JFR, Currie AR. Cell death: the significance of apoptosis. In: Bourne GH, Danielli JF, Jeon KW, editors. International review of cytology. London: Academic; 1980. p. 251-306.

OnlineFirst chapter in a series (without a volume designation but with a DOI)

Saito Y, Hyuga H. Rate equation approaches to amplification of enantiomeric excess and chiral symmetry breaking. Top Curr Chem. 2007. doi:10.1007/128_2006_108.

Complete book, authored

Blenkinsopp A, Paxton P. Symptoms in the pharmacy: a guide to the management of common illness. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1998.

Online document

Doe J. Title of subordinate document. In: The dictionary of substances and their effects. Royal Society of Chemistry. 1999. http://www.rsc.org/dose/title of subordinate document. Accessed 15 Jan 1999.

Online database

Healthwise Knowledgebase. US Pharmacopeia, Rockville. 1998. http://www.healthwise.org. Accessed 21 Sept 1998.

Supplementary material/private homepage

Doe J. Title of supplementary material. 2000. http://www.privatehomepage.com. Accessed 22 Feb 2000.

University site

Doe, J: Title of preprint. http://www.uni-heidelberg.de/mydata.html (1999). Accessed 25 Dec 1999.

Doe, J: Trivial HTTP, RFC2169. ftp://ftp.isi.edu/in-notes/rfc2169.txt (1999). Accessed 12 Nov 1999.

Organization site

ISSN International Centre: The ISSN register. http://www.issn.org (2006). Accessed 20 Feb 2007.

Dataset with persistent identifier

Zheng L-Y, Guo X-S, He B, Sun L-J, Peng Y, Dong S-S, et al. Genome data from sweet and grain sorghum (Sorghum bicolor). GigaScience Database. 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.5524/100012 .

Figures, tables and additional files

See General formatting guidelines for information on how to format figures, tables and additional files.

Submit manuscript

Important information

Editorial board

For authors

For editorial board members

For reviewers

- Manuscript editing services

Annual Journal Metrics

2022 Citation Impact 2.6 - 2-year Impact Factor 2.9 - 5-year Impact Factor 1.091 - SNIP (Source Normalized Impact per Paper) 0.668 - SJR (SCImago Journal Rank)

2023 Speed 46 days submission to first editorial decision for all manuscripts (Median) 224 days submission to accept (Median)

2023 Usage 2,869,703 downloads 1,231 Altmetric mentions

- Follow us on Twitter

BMC Veterinary Research

ISSN: 1746-6148

- General enquiries: [email protected]

We have detected that you are using a browser that is no longer supported , and recommend you upgrade your browser or get a better browser . This site has been developed inline with current standards and best practice, therefore we cannot guarantee you will not experience issues with some functions.

- Which VNCA membership is right for you?

- Join online today

- Why join the VNCA?

- Exclusive benefits for VNCA members

- Recognised qualifications

- Code of Professional Conduct

- Get involved

- Access the HR Helpline

- Shop Online

- VNCA Scholarships

- 2024 VNCA Professional Development Scholarships

- 2024 VNCA Helen Power Future Leader Scholarship

- MyCPDTracker - members only

- MyVNCAgroups

- International Keynote Speakers

- CPD Points and Certificate

- 31st VNCA Conference

- CPD calendar

- Veterinary Nurse & Technician Awareness Week 2023

- Vet Nurse/Technician of the Year Awards

- What is the AVNAT Registration Scheme?

- About the AVN Scheme

- Become an AVN

- Maintenance of accreditation

- Re-accreditation

- Apply for NIAG points

- What is a Veterinary Nurse?

- Becoming a Veterinary Nurse

- The Veterinary Nurse Qualification

- VNCA Day One Competency Standards

- Training Providers

- Which Training Organisation to choose

- Recognition of Prior Learning

- For Overseas Trained Veterinary Nurses

- Radiation User Licensing

- Wellness Hub - Welcome

- Member Assistance Program (EAP)

- About the AVNJ

- AVNJ online - current issue (members only)

- Past Issues (Members Only)

- Subscribe to the AVNJ

Author Guidelines

- Advertise with the VNCA

- About VNCA's HR Resources

- HR Helpline

- HR Articles

- HR Webinars

- Wellness Hub

- VNCA Climate Action Resources

- VNCA Position Statements

- Latest news

- Annual General Meetings

- Board of Directors

- Partner with us

- member login

The Editorial Committee warmly welcome submissions from VNCA members and the broader veterinary industry for publication in the AVNJ.

How to write a technical article.

A technical article describes procedures of a specific interest that might be of benefit to other veterinary nurses by enabling them to learn about the latest or different methods of practice in a particular case.

Download here.

How to write a short article

A short article refers to a one-page article outlining hints, tips, techniques or procedures that you may use or have seen used that would be of benefit to other veterinary nurses in their workplace.

How to write a case report

Veterinary Nurses who would like to apply for AVN accreditation or have a case study published in the AVNJ can download guidelines on how to write a case study here.

How to write a book review

Writing a review for a clinical text book allows evaluation of a book for one’s own purposes as well as for others by expressing views or opinions regarding the book’s scope, layout and relevancy. The aim should be to help the reader determine whether or not the book is appropriate for their resource needs. The format of such a review should be easy to read, to the point and displayed in relevant paragraphs.

Permission forms

If you wish to submit an article or photograph for publication in the AVNJ please submit the relevant permission form:

- Model release form

- AVNJ Permission form.

Email the AVNJ Editor - [email protected] - for further information.

VNCA Partners

The VNCA gratefully acknowledges the support of our partners:

Click here to find out more about partnering with us.

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Writing patient care reports: author guidelines for vns.

Perdi Welsh

View articles

Published patient care reports (PCRs) (also known as case reports) can provide a valuable means for veterinary nurses to share their clinical experiences, increase their knowledge and contribute to the establishment of an evidence-based approach to veterinary nursing practice. This article is the first of a two-part series which aims to inform readers of the benefits of writing and publishing PCRs and give potential authors an overview of the format and conventions of academic writing required for these reports. In particular, this first article discusses the recommendation made by the authors that veterinary nurses adopt an appropriate writing style and language in these reports in an attempt to foster a more patient focussed and holistic approach to the provision of evidence-based veterinary nursing care.

Veterinary nursing in the UK is taking some of the first crucial steps towards professionalization with the recent introduction of registration of members, impending disciplinary procedures and amendments to the law which specifically refer to the work of veterinary nurses. Each of these developments is significant and each is an essential component in the evolution towards professional status, but there are several other crucial elements that veterinary nurses need to implement before they can secure this status ( Branscombe, 2010; Clarke, 2010; Banks, 2010/11 ). One well-documented condition is that a profession has its own unique body of knowledge and evidence base on which to base its clinical and professional practice ( Hern, 2000; Mahony, 2003; Holmes and Cockcroft, 2004; Pullen, 2006 ).

Peer-reviewed journals such as The Veterinary Nurse provide a hugely significant advancement for veterinary nursing's endeavour towards professional recognition. Published case reports can assist veterinary nursing practitioners to gain a deeper knowledge and understanding of their clinical veterinary nursing practice, share and foster good practice and start to build an evidence base on the care that should be provided to patients ( Dias, 2010 ; Jamjoom et al, 2010). There is an undercurrent of negative attitude held by some medical journals that case reports do not provide a robust source of evidence base compared with primary research studies, but there are those that argue that despite their anecdotal nature, case reports still play a hugely important part in the development of a profession, and provide a noteworthy method of sharing knowledge and generating an evidence base ( White, 2004 ; Jamjoom et al, 2010). The authors of this article believe that at this stage in the journey toward professionalization, publishing case reports provides a powerful way of creating a knowledge base and will help define the role of the veterinary nurse in particular in relation to patient care. Case reports have the potential to provide a number of different groups within any profession tangible benefits; for student veterinary nurses such reports can help develop students' knowledge and understanding about specific conditions (Jamjoom et al, 2010) and provide them with opportunity to develop skills in academic and scientific writing. For practitioners they provide a means of creating a record of clinical practice and to convey unusual or challenging patient presentations to their colleagues (White, 2004). When published in journals, such as this, they help others in the profession develop specialist knowledge and highlight issues which can then be further explored through research studies ( Cohen, 2006 ).

Traditionally, patient care reports are called ‘case’ reports by the majority of other professions, including the veterinary and paramedical professions. The authors of this article suggest that veterinary nurses, in their endeavour to move towards a more holistic and patient-focussed approach to the delivery of their nursing care, should steer clear of using the term ‘case’ which identifies patients by their condition rather than recognizing them as sentient beings with specific requirements of their own (which may or may not be related to the disease or disorder they present with). Referring to a patient as ‘the GSD with the fracture’ could be considered to foster a medical approach ( Orpet and Welsh, 2011 ) and it is becoming more widely recognized in veterinary nursing that the medical model is an out dated and inappropriate way to approach patient care ( Jeffery, 2006 ; Pullen, 2006). If the terminology used by the profession contributes in part to the way we provide care for our patients, then the authors recommend that the vocabulary we adopt fosters a more patient-focussed approach. As a simple example, a typical title for a case report might be ‘Case report of diabetes insipidus’, whereas a more patient-focussed approach would be to use a title such as ‘Patient care report of the nursing care provided to feline patient with diabetes insipidus’. Therefore, it is suggested that the terminology patient care report (PCR) would be a more appropriate way to refer to these types of report.

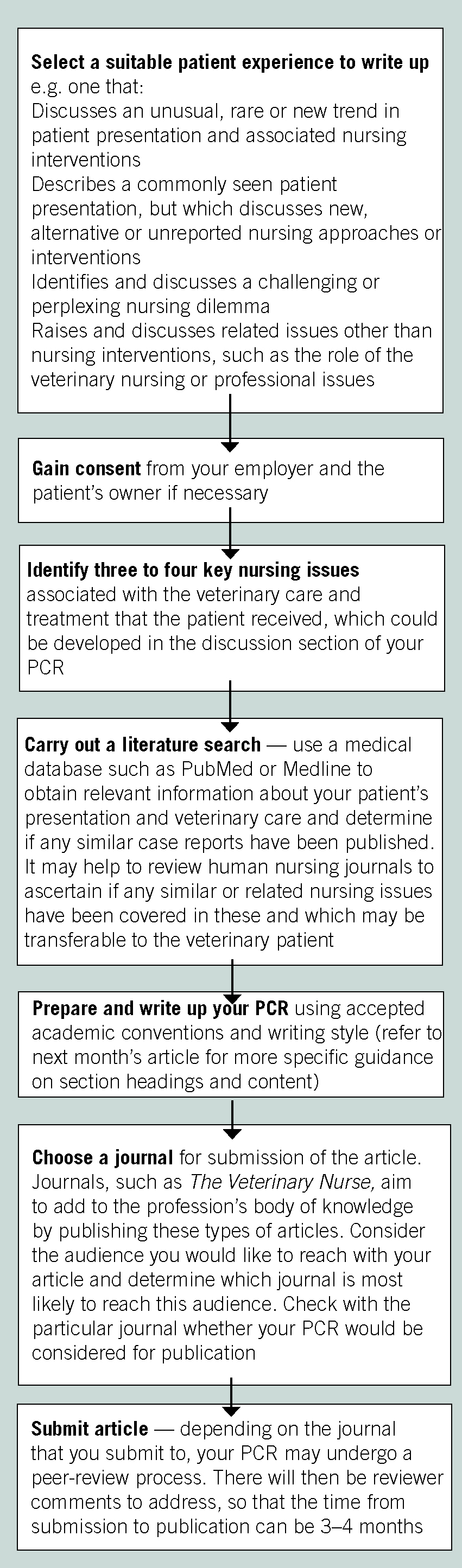

For those new to writing for this type of publication, the task of preparing this type of report can be daunting and time consuming. As Budgell (2008) points out, these types of reports should ideally written by those working in clinical practice, but too often clinical practitioners have little experience or confidence in writing for academic journals and struggle to find the time to write up their experiences in a format suitable for peer-reviewed journals (White, 2004). The aim of these guidelines is to help all veterinary nurses, and particularly those working at the front line of veterinary nursing practice, master some of the conventions of academic writing and become more efficient at writing high quality and reliable reports to a publishable standard. It should be noted that these are guidance notes, intended to help the novice writer achieve a document of a certain academic standard. They should not be considered the definitive word on writing PCRs and any veterinary nurses considering writing up such reports should check first with the publisher for any specific requirements ( Figure 1 ).

What are PCRs?

PCRs provide a written account of a practitioner's observations and experiences while nursing a particular patient. These reports should not only identify the patient's presenting problems and description of what was done, but also show how the author has integrated and applied theory and an evidence base into the nursing care provided for the patient while under their care. Crucially, PCRs should demonstrate that the author has critically evaluated the nursing intervention that took place and provide some recommendations for future practice. When authors provide not only a written description of what happened, but also provide a critical evaluation of the nursing care provided to a particular patient (by jusification and discussion of alternatives to the care provided using an appropriate evidence base), PCRs have the potential to enable veterinary nurses to gain fresh and improved insight into clinical practice. This could be described as a way of undertaking reflective practice. As advocated by Schön (1987) and many others since, reflection of one's personal and professional practice helps develop one's own, and also the audience's knowledge and understanding of clinical and professional practice. Burns and Bulman (2000) advocate, reflection is a way to stimulate a more critical approach to clinical practice and McBrien (2007) suggests that reflection on daily activities can be self empowering and help members of a profession gain control over some of the issues and complexities of their day-to-day work.

Which patients should PCRs be written about?

Those new to writing PCRs report that they find it difficult to know which patient experiences warrant writing up for publication. PCRs should reflect aspects of the VNs clinical work which were either entirely managed by them or in which they had significant involvement. The authors recommend that those new to writing this type of report should select a patient experience which is sufficiently complex to allow adequate analysis, but not one with multiple problems or that is so overly complex that it becomes too difficult to write a well-structured, reflective review within any word limit imposed by the publisher. The most informative PCRs are not necessarily about the most unusual or complex patients. Sharing good practice about the care of patients seen every day will stimulate further discussion and hopefully start to create an evidence base for patient care.

What should the focus of a PCR be?

The focus of a PCR should be based around how the patient was managed and provide a critical evaluation of the nursing intervention carried out. It may be appropriate to focus the report on one particular nursing domain, for example, a surgical PCR should primarily centre on the nursing considerations of the patient related to the pre-, peri- and post-surgical period rather than digressing into any considerations relating to the anaesthesia. PCRs should not be a lengthy description of the diagnosis and/or treatments given by the veterinary surgeon but should instead focus on discussion of the nursing interventions taken and the care provided. Discussion and reflection of some of the complex problems faced while nursing the patient should be provided with exploration of alternative approaches to nursing care that might have been taken.

What academic style and presentation is expected?

Published PCRs should follow accepted academic conventions using suitable language and vocabulary. PCRs should be written in the third person, in past tense. The structure of the report should be coherent, logical and organized, using headings and subheadings to break the report up into appropriate sections (see next month's follow-up article). As with any published material, the content should be entirely the author's own work to avoid plagiarism, and statements, opinions and the ideas and work of others should be referenced appropriately. Work should be spell and grammar-checked (UK English). Proof reading is essential as word processing programs do not always pick up spelling or grammatical errors. Individual journals will specify the minimum and maximum number of words permitted.

Are there conventions that need to be adhered to?

There are certain conventions which are particular to writing any medical/veterinary case reports and these should be followed:

- Abbreviations and acronyms should be written in full for the first mention in the text, followed by the abbreviation in brackets. The abbreviated form can be used from then on. In general, words should not be abbreviated unless they are used repeatedly (three or more times). Exceptions to this rule are abbreviations used frequently in professional conversation, for example, an electrocardiogram is called an ECG in conversation and may be referred to in this way from the start in some journals. Many journals supply a list of abbreviations that can be used without qualification. Check the journal's author guidelines

- The full scientific name of the genus and species must be formatted in italics and written in full when first mentioned in the text. Thereafter, it may be written in its genus abbreviation. For example, Staphylococcus intermedius — S. intermedius. The genus should be capitalized in both cases and the species should be in lower case

- Writing units of measurement, e.g. ml, kg, etc. All measurements should follow the SI units system (Systeme International d'Units). Metric units should be used for all measurements such as weight, volume and length. A space should be left between the number and the unit (except for percentage and degrees temperature where no space is required). Generally percent should be written in full rather than as % when the number is written out in full (again check journal style) — in tables all number are written out as arabic numerals with the % sign. Temperatures should be provided in degrees Celsius and written as °C

- Drugs should be referred to by their generic name, with trade name provided in parentheses after the first mention of the drug in the text. The generic name alone may be used in the text thereafter. Where relevant, the author may include the strength, dose and route of the drug.

Photographs, radiographs, illustrations and tables may be included in PCRs. If they are clear and accompanied by a legend they can be an excellent addition. However, the anonymity of any clients, colleagues or patients must be maintained (i.e. do not include any information or identifiable features) unless consent has been obtained to use the images.

Authors are also advised to obtain permission from their employers and/or the supervizing veterinary surgeon before submitting a PCR for publication.

PCRs have the potential to make a significant contribution to the development of a patient care evidence base so desperately needed by veterinary nurses today in their journey toward professional status. PCRs should ideally be written by those working in clinical practice as a way to share and develop best practice in patient care. However, many veterinary nurse practitioners are unfamiliar or inexperienced with writing this type of report for publication and are unclear of some of the formalities of academic writing. This article is the first of a two-part series and provides readers with an overview of some of the reported benefits of writing and publishing these types of reports particularly for any vocation progressing toward professionalization. Potential authors are also provided with some guidelines on the content and language style that these reports should contain.

In the next edition, part two of this series will provide readers with more practical guidelines and instruction to help them record and critically reflect on their experiences of patient care to help them create PCRs suitable for publication.

Related content

Writing patient care reports: author guidelines for vns part 2, an evaluation of henderson's nursing needs model and how it can be adapted for use in veterinary nursing, using the ability model to design and implement a patient care plan, evidence-based practice in veterinary nursing.

Veterinary Clinical Cases

Your browser is out-of-date!

Update your browser to view this website correctly. Update my browser now

In every case, be it writing a veterinary expert report on the scientific interpretation of laboratory data or standing up in court acting as an expert witness on behalf of the court, I find that I am learning more about the subject than I have from reference books. This article is intended to help general […]

Writing an expert report

Some important pointers for completing a veterinary expert report, using an example case

In every case, be it writing a veterinary expert report on the scientific interpretation of laboratory data or standing up in court acting as an expert witness on behalf of the court, I find that I am learning more about the subject than I have from reference books.

This article is intended to help general practitioners who are involved in forensic matters benefit from examples of what can happen afterwards.

Animal Welfare Act 2006

A large number of welfare investigations are carried out under the provisions of this Act. A very important part of the practical enforcement of issues affecting the welfare of animals is the ability to remove them from the environment in which suffering is being caused or likely to be caused.

Section 18 of the Act defines the powers available to (properly appointed) inspectors and (police) officers. Note that an “inspector”, for the purposes of this Act, and defined in section 51 of the Act, is currently likely to be a state veterinary service inspector or an inspector authorised by a local authority.

A welfare worker, for example someone employed by the RSPCA, PDSA or RSPB, is not considered to be an inspector under the provisions of this Act and therefore must rely on an officer or an inspector to exercise various powers, such as set out in section 18 of the Act, legally. These workers have no powers of entry onto premises such as homes, gardens and farms.

The relevant part of section 18, powers in relation to animals in distress, is subsection 5: “An inspector or a constable may take a protected animal into possession if a veterinary surgeon certifies— (a) that it is suffering, or (b) that it is likely to suffer if its circumstances do not change.”

If you, a veterinary surgeon, are aiding an animal welfare worker or other inspector or officer in a case involving the welfare of animals, you may be asked to complete a section 18(5) certificate under the Act. This procedure is very important; it will allow the inspector or officer (but not the welfare worker) to take into possession (seize from the owner or keeper) the animal whose welfare you consider to be compromised. The officer or inspector will, usually, immediately pass that animal into the care of the welfare worker. It is often the case that you will be asked to carry out a forensic clinical examination of the animal so you can fully document its state of health.

The s18(5) certificate is often saved on a practice management system as a blank pro forma or you may be presented with a blank form at the scene. Figure 1 shows an example that is, in my experience, typical of the completed certificates issued by veterinary surgeons and used in court as evidence supporting a criminal investigation and prosecution.

A very important part of the practical enforcement of issues affecting the welfare of animals is the ability to remove them from the environment in which suffering is being caused or likely to be caused

RCVS guidelines

The RCVS produces some very comprehensive guidelines in its Code of Professional Conduct. Chapter 21 – “Certification” – details the 10 Principles of Certification as well as paragraphs with commentary and advice (eg 21.3).

21.3 includes the statement “The simple act of signing their names on documents should be approached with care and accuracy” and 21.5 details “Veterinarians should also familiarise themselves with the form of certificate they are being asked to sign and any accompanying Notes for Guidance, instructions or advice from the relevant Competent Authority.”

In my opinion, Figure 1 shows a number of obvious deviations from the RCVS certificate requirements. The list of deviations I have compiled is probably not complete (I do not believe that I have seen everything yet), but I offer it here as an indication of what is actually done. I have provided my commentary as to why I think there are problems with relying on this certificate in the forensic arena and have given advice on how to avoid criticism.

Deviations in Figure 1 from RCVS guidelines

“Print Name” and “Signed” transposed

21.3 not satisfied. I know this is picky and obvious, but it may be seen by others as indicating a lack of attention to detail by the veterinarian responsible, which may be reflected in other parts of the certificate (as was the case in this example). If your errors lead to you being challenged in court, not only are you going to be embarrassed but it may not reflect well on the profession.

Exhibit number

The certificate describes “puppies in a cage”, however, their exhibit numbers are not properly listed. Is it four puppies: “AF-1” and “2” and “3” and “4”; or five: “AF” and “1” and “2” and “3” and “4”; or four: “AF-1” and “AF-2” etc? This is contrary to principle 10. Certificates should clearly identify the subject being certified. There are four sections on this pro forma so why was each exhibit (puppy) not given its own, unique entry? If there were more than four individuals then a second certificate should have been prepared.

Description

The number of puppies is not defined (and there is not enough certainty regarding the exhibit numbers to be certain of that number). Each of the puppies is not identified in sufficient detail to enable the individual to be “clearly identifiable” (unique markings, microchip, colour, sex, etc) – contrary to principle 10. The use of hospital collars (temporary plastic collars on which identification marks may be written in indelible pen) is commonplace, cheap and very reliable. If all the puppies were very similar and no alternatives available, then simply marking each with a felt pen or nail varnish (mark on the left ear = AF-1, on right ear = AF-2, etc) would suffice. The certificate clearly alludes to the singular “animal” for each part of the document, ie “The animal is likely…”, so, to lump many individuals together is not consistent with the format of the certificate. The effort required to detail each individual into a separate part of a certificate and follow its format is part of the discipline required of you.

Parts of the certificate left incomplete

This is contrary to principle 6. A simple score-through of the blanks would have prevented this criticism.

No mention of the subsection of section 18

It is not noted to which subsection the certificate applies (the certificate may be used for subsection 3 or 5). If the document was intended to be an s18(5) certificate, then that should have been indicated.

No copy made of the certificate

This is contrary to principles 1 and 8. I have not yet been aware of a single veterinary surgeon copying certificates such as this for their own records. Certainly, copies are made (usually by the prosecuting agency), however, the originals invariably are issued at the scene without this requirement having been met. Most mobile phones can take photographs, which can be printed later, and there are many apps (some free) which will produce PDF files of photographic images taken on mobiles.

Address of issuing veterinarian missing

This is contrary to principle 6. Again, I have yet to see a single s18(5) certificate with such information included. Even if you have not brought your practice stamp with you, you should add the practice details in longhand as you may not be the only “J Smith MRCVS” in the UK that day.

Certificate completed and signed in black ink

This is contrary to principle 6. Make sure you have a pen of any colour other than black to hand when completing these certificates.

No unique certificate identifier

This is contrary to principle 8. The certificate itself is an item of evidence and should be given a unique identifier (which, if necessary, could then be associated with an exhibit number or may even be an exhibit in its own right) by you. Your initials and a number will do, but be sure to record the identification in your contemporaneous notes.

Circumstances of issuing of a certificate

I have compiled a few points from my experiences in court regarding these certificates. I am not legally trained or qualified, so my comments here are “for information only” and must be verified by a legal professional if their content is intended to be relied upon.

Firstly, if you intend to issue an s18(5) certificate, you must issue it as a signed paper document, completed properly, to the officer or inspector before they try to take possession of the animals to which the certificate applies. It is not sufficient to issue a “verbal” certificate, eg “Yes officer, I do believe that the puppies in that cage are likely to suffer if their circumstances do not change, pursuant to s18(5) of the AWA 2006.”

If the officer or inspector relies on your verbal statement (even if you prepare a written certificate later and provide it after the fact), it may be argued in court that the seizure was unlawful and that the evidence obtained as a result should be excluded from the hearing. This could jeopardise the hard work, time, effort and money expended in collecting that evidence.

Try to do as much homework as possible before undertaking welfare cases. You are the professional and you owe it to everyone concerned to be aware of the rules and responsibilities that forensic work may demand. Familiarise yourself with the relevant parts of the Animal Welfare Act 2006 and its accompanying documents. Find out if you have the correct paperwork, make sure you have appropriate equipment (including a blue biro) and the “visit kit”.

If you are in doubt as how to proceed, stop. Ask for help and advice; organisations such as the RCVS, BVA, BSAVA and VDS are all there to help and are the best placed to do so. Do not be pressurised into doing something that you are not comfortable with.

Finally, examine the animal. The 1st Principle of Certification states that “A veterinarian should certify only those matters which: … b) can be ascertained by him or her personally; …”. Whether or not you think it is necessary to state the obvious, it will be much better received by a court if you could say that you turned up at an animal welfare crime scene with, at least, a stethoscope and thermometer, and could document that you used them.

Your favourite columns

Have you heard about our IVP Membership?

A wide range of veterinary CPD and resources by leading veterinary professionals.

Stress-free CPD tracking and certification, you’ll wonder how you coped without it.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Veterinary Medicine Case Study

Mrs. Edelstein is curious about vaccinating him against Lyme disease and asks you for your recommendation. Your clinic does not yet have a protocol for the Lyme vaccine and you would like to do more research.

For accessible versions of these activities, please refer to our document Step 1: Ask – Accessible Case Studies .

Evidence-Based Practice Copyright © by Various Authors - See Each Chapter Attribution is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing as a Veterinary Technician

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This section is intended to provide veterinary technicians with guidelines for writing the patient care plan portion of the veterinary medical record. As there is no standardized format for writing a veterinary care plan, the following principles are only one example of how a care plan may be formulated. These principles have been adapted from materials developed by veterinary technology instructor/academic advisor Jamelyn Schoenbeck Walsh and veterinary instructional technologist Margaret Lump of Purdue University’s Veterinary Technology Program .

Veterinary medical records must be complete, accurate, orderly, and legible and should give a description of what was done, when, by whom, why, how, and where. Because they are legal documents, certain conventions must be followed when recording information. Of concern are legal issues surrounding documentation.

A patient’s record is a compilation of all written information, reports, and communication regarding the patient’s care, and it should render a full understanding of the patient’s health status. To this end, a patient care plan should include, but is not limited to, the following parts:

- Patient signalment and client information

- History and presenting chief complaint

- Current health status and history

- Past, birth, and referral history

- Patient assessment

- Technician evaluation

- Interventions

- Rationale for interventions

- Continued patient reassessment

- Desired resolutions

- Progress notes

- Discharge planning

- Legal issues of documentation

- Sample care plan example

Each of the sections above contains guidelines on what information to include and how, as well as relevant examples of how a specific case might be documented.

A complete sample patient care plan will be available soon. Please note this PDF is a sample and should not be used as a template. For formatting questions, consult your instructor.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

<img alt="Settings" srcSet="/_next/static/media/settings-icon.948bffc5.svg 1x, /_next/static/media/settings-icon.948bffc5.svg 2x" src="/_next/static/media/settings ...

Through the development of medicine both veterinary and medicine, case reports have provided a way of relaying clinical experience and disseminating knowledge, and in some cases, have provided pivotal observations changing medical understanding and practice. They are essentially a written 'case rounds', using history and presentation of ...

Case reports should include relevant positive and negative findings from history, examination and investigation, and can include clinical photographs. Case reports should include an up-to-date review of all previous cases in the field. BMC Veterinary Research strongly supports open research, including transparency and openness in reporting.

Case studies help to educate the public and document information for future use. The format of a case study depends upon the information gathered. The following items may be included in a case study: Abstract - a summary of the paper. Use keywords so that an indexer can cross reference the study. Include: Description of the condition. Diagnosis.

CARE guidelines for case reports: explanation and elaboration document. Background: Well-written and transparent case reports (1) reveal early signals of potential benefits, harms, and information on the use of resources; (2) provide information for clinical research and clinical practice guidelines, and (3) inform medical education.

Your study design must be appropriate for answering the research question. Prospective, retrospective, and descriptive study designs, as well as randomized clinical trials, cohort studies, meta-analyses, and other types of studies, approach a problem in different ways; each has strengths and limitations.

Evidence - based veterinary medicine (case studies) is being increasingly used to evaluate therapies. The research committee of the AHVMA has established the goal of increasing published case studies in CAVM. This will help practi-tioners of CAVM as well as be a guide to legislative bodies. A publishable case report contains:

Writing a review for a clinical text book allows evaluation of a book for one's own purposes as well as for others by expressing views or opinions regarding the book's scope, layout and relevancy. The aim should be to help the reader determine whether or not the book is appropriate for their resource needs. The format of such a review ...

Veterinary Medicine Case Study. In the past case studies and activities you have: identified the PICO components of your patient scenario, formulated a clinical question, found an appropriate article to answer your question, and critically appraised the article. Now, it's time to apply what you've learned to your patient.

Veterinary Record Case Reports is an online resource that publishes articles in all fields of veterinary medicine and surgery so that veterinary professionals, researchers and others can easily find important information on both common and rare conditions. All articles are peer reviewed. Journal Metrics.

A case report should communicate a novel occurrence, manifestation or management of a case. The goal is to add to the body of knowledge of an existing or newly recognised condition, whether as documentation of a single clinical episode, or as part of a series of clinically similar events.

Overview. Veterinary Record Case Reports is an online resource that publishes articles in all fields of veterinary medicine and surgery so that veterinary professionals, researchers and others can easily find important information on both common and rare conditions. Articles may be about a single animal, herd, flock or other group of animals managed together.

Microsoft Word - SOAP handout.doc. Tips for SOAP Writing. The VMTH physical exam sheet uses a check list system, but in practice, you will want to develop a systematic written format to make sure that you describe all relevant exam findings, even when they are normal. During your 4th year, in order to develop your ability to generate ...

This journal's articles appear in a wide range of abstracting and indexing databases, and are covered by numerous other services that aid discovery and access. Find out more about where and how the content of this journal is available. Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine publishes case reports and case series in all areas of veterinary medicine.

Abstract. Published patient care reports (PCRs) (also known as case reports) can provide a valuable means for veterinary nurses to share their clinical experiences, increase their knowledge and contribute to the establishment of an evidence-based approach to veterinary nursing practice. This article is the first of a two-part series which aims ...

All articles should be accompanied by five to six high-resolution pictures. A 100-word abstract should also be included for every article. This is not simply a repeat of the introduction, but should summarise your article and for clinical research should give the reader a synopsis of your project including the results.

Welcome to the Veterinary Clinical Cases portal, a site that is dedicated to case materials for on-line learning. We aim to offer a wide variety of interactive cases for veterinarians and veterinary students to work through, with progressive disclosure of information as you would normally obtain during a face to face consultation with the owner ...

8 min read. In every case, be it writing a veterinary expert report on the scientific interpretation of laboratory data or standing up in court acting as an expert witness on behalf of the court, I find that I am learning more about the subject than I have from reference books. This article is intended to help general practitioners who are ...

Activity: Use the CASP UK's Systematic Review Checklist to critically appraise this article. For an accessible version of this activity, please refer to our document Step 3: Appraise - Accessible Case Studies. After you have completed the case study, go to Step 4: Apply.

Veterinary Medicine Case Study. A new client, Mrs. Edelstein brings in "Mr. Bojangles", an energetic 5 year-old male Golden Retriever with whom she has just moved from North Dakota. They walk outdoors in wooded areas daily and she reports frequently finding ticks on him after walks. She is diligent about preventative medications for fleas ...

Writing as a Veterinary Technician. This section is intended to provide veterinary technicians with guidelines for writing the patient care plan portion of the veterinary medical record. As there is no standardized format for writing a veterinary care plan, the following principles are only one example of how a care plan may be formulated.

Case examples: 10-year old male neutered Keeshond, 23.5 kg; 11-year-old male Beagle, 17 kg. Hyperthyroidism and the feline kidney. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Nephrology and Urology. Hyperthyroidism is a common condition of senior and geriatric cats that is present in 6% of cats over the age of nine years old.

Rare case of ocular onchocerciasis in a dog from south Texas. January 25, 2023 by Mallory Pfeifer. Rare case of ocular onchocerciasis in a dog from south Texas Erin Edwards, DVM, MS, DACVP and Mindy Borst, LVT A formalin-fixed globe from an 11-year-old, castrated male, Pitbull dog was submitted to the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Diagnostic ….