- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Writing a Literature Review

When writing a research paper on a specific topic, you will often need to include an overview of any prior research that has been conducted on that topic. For example, if your research paper is describing an experiment on fear conditioning, then you will probably need to provide an overview of prior research on fear conditioning. That overview is typically known as a literature review.

Please note that a full-length literature review article may be suitable for fulfilling the requirements for the Psychology B.S. Degree Research Paper . For further details, please check with your faculty advisor.

Different Types of Literature Reviews

Literature reviews come in many forms. They can be part of a research paper, for example as part of the Introduction section. They can be one chapter of a doctoral dissertation. Literature reviews can also “stand alone” as separate articles by themselves. For instance, some journals such as Annual Review of Psychology , Psychological Bulletin , and others typically publish full-length review articles. Similarly, in courses at UCSD, you may be asked to write a research paper that is itself a literature review (such as, with an instructor’s permission, in fulfillment of the B.S. Degree Research Paper requirement). Alternatively, you may be expected to include a literature review as part of a larger research paper (such as part of an Honors Thesis).

Literature reviews can be written using a variety of different styles. These may differ in the way prior research is reviewed as well as the way in which the literature review is organized. Examples of stylistic variations in literature reviews include:

- Summarization of prior work vs. critical evaluation. In some cases, prior research is simply described and summarized; in other cases, the writer compares, contrasts, and may even critique prior research (for example, discusses their strengths and weaknesses).

- Chronological vs. categorical and other types of organization. In some cases, the literature review begins with the oldest research and advances until it concludes with the latest research. In other cases, research is discussed by category (such as in groupings of closely related studies) without regard for chronological order. In yet other cases, research is discussed in terms of opposing views (such as when different research studies or researchers disagree with one another).

Overall, all literature reviews, whether they are written as a part of a larger work or as separate articles unto themselves, have a common feature: they do not present new research; rather, they provide an overview of prior research on a specific topic .

How to Write a Literature Review

When writing a literature review, it can be helpful to rely on the following steps. Please note that these procedures are not necessarily only for writing a literature review that becomes part of a larger article; they can also be used for writing a full-length article that is itself a literature review (although such reviews are typically more detailed and exhaustive; for more information please refer to the Further Resources section of this page).

Steps for Writing a Literature Review

1. Identify and define the topic that you will be reviewing.

The topic, which is commonly a research question (or problem) of some kind, needs to be identified and defined as clearly as possible. You need to have an idea of what you will be reviewing in order to effectively search for references and to write a coherent summary of the research on it. At this stage it can be helpful to write down a description of the research question, area, or topic that you will be reviewing, as well as to identify any keywords that you will be using to search for relevant research.

2. Conduct a literature search.

Use a range of keywords to search databases such as PsycINFO and any others that may contain relevant articles. You should focus on peer-reviewed, scholarly articles. Published books may also be helpful, but keep in mind that peer-reviewed articles are widely considered to be the “gold standard” of scientific research. Read through titles and abstracts, select and obtain articles (that is, download, copy, or print them out), and save your searches as needed. For more information about this step, please see the Using Databases and Finding Scholarly References section of this website.

3. Read through the research that you have found and take notes.

Absorb as much information as you can. Read through the articles and books that you have found, and as you do, take notes. The notes should include anything that will be helpful in advancing your own thinking about the topic and in helping you write the literature review (such as key points, ideas, or even page numbers that index key information). Some references may turn out to be more helpful than others; you may notice patterns or striking contrasts between different sources ; and some sources may refer to yet other sources of potential interest. This is often the most time-consuming part of the review process. However, it is also where you get to learn about the topic in great detail. For more details about taking notes, please see the “Reading Sources and Taking Notes” section of the Finding Scholarly References page of this website.

4. Organize your notes and thoughts; create an outline.

At this stage, you are close to writing the review itself. However, it is often helpful to first reflect on all the reading that you have done. What patterns stand out? Do the different sources converge on a consensus? Or not? What unresolved questions still remain? You should look over your notes (it may also be helpful to reorganize them), and as you do, to think about how you will present this research in your literature review. Are you going to summarize or critically evaluate? Are you going to use a chronological or other type of organizational structure? It can also be helpful to create an outline of how your literature review will be structured.

5. Write the literature review itself and edit and revise as needed.

The final stage involves writing. When writing, keep in mind that literature reviews are generally characterized by a summary style in which prior research is described sufficiently to explain critical findings but does not include a high level of detail (if readers want to learn about all the specific details of a study, then they can look up the references that you cite and read the original articles themselves). However, the degree of emphasis that is given to individual studies may vary (more or less detail may be warranted depending on how critical or unique a given study was). After you have written a first draft, you should read it carefully and then edit and revise as needed. You may need to repeat this process more than once. It may be helpful to have another person read through your draft(s) and provide feedback.

6. Incorporate the literature review into your research paper draft.

After the literature review is complete, you should incorporate it into your research paper (if you are writing the review as one component of a larger paper). Depending on the stage at which your paper is at, this may involve merging your literature review into a partially complete Introduction section, writing the rest of the paper around the literature review, or other processes.

Further Tips for Writing a Literature Review

Full-length literature reviews

- Many full-length literature review articles use a three-part structure: Introduction (where the topic is identified and any trends or major problems in the literature are introduced), Body (where the studies that comprise the literature on that topic are discussed), and Discussion or Conclusion (where major patterns and points are discussed and the general state of what is known about the topic is summarized)

Literature reviews as part of a larger paper

- An “express method” of writing a literature review for a research paper is as follows: first, write a one paragraph description of each article that you read. Second, choose how you will order all the paragraphs and combine them in one document. Third, add transitions between the paragraphs, as well as an introductory and concluding paragraph. 1

- A literature review that is part of a larger research paper typically does not have to be exhaustive. Rather, it should contain most or all of the significant studies about a research topic but not tangential or loosely related ones. 2 Generally, literature reviews should be sufficient for the reader to understand the major issues and key findings about a research topic. You may however need to confer with your instructor or editor to determine how comprehensive you need to be.

Benefits of Literature Reviews

By summarizing prior research on a topic, literature reviews have multiple benefits. These include:

- Literature reviews help readers understand what is known about a topic without having to find and read through multiple sources.

- Literature reviews help “set the stage” for later reading about new research on a given topic (such as if they are placed in the Introduction of a larger research paper). In other words, they provide helpful background and context.

- Literature reviews can also help the writer learn about a given topic while in the process of preparing the review itself. In the act of research and writing the literature review, the writer gains expertise on the topic .

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

- UCSD Library Psychology Research Guide: Literature Reviews

External Resources

- Developing and Writing a Literature Review from N Carolina A&T State University

- Example of a Short Literature Review from York College CUNY

- How to Write a Review of Literature from UW-Madison

- Writing a Literature Review from UC Santa Cruz

- Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149. doi : 1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

1 Ashton, W. Writing a short literature review . [PDF]

2 carver, l. (2014). writing the research paper [workshop]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Research Paper Structure

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

In order to help minimize spread of the coronavirus and protect our campus community, Cowles Library is adjusting our services, hours, and building access. Read more...

- Research, Study, Learning

- Archives & Special Collections

- Cowles Library

- Find Journal Articles

- Find Articles in Related Disciplines

- Find Streaming Video

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Organizations, Associations, Societies

- For Faculty

What is a Literature Review?

Description.

A literature review, also called a review article or review of literature, surveys the existing research on a topic. The term "literature" in this context refers to published research or scholarship in a particular discipline, rather than "fiction" (like American Literature) or an individual work of literature. In general, literature reviews are most common in the sciences and social sciences.

Literature reviews may be written as standalone works, or as part of a scholarly article or research paper. In either case, the purpose of the review is to summarize and synthesize the key scholarly work that has already been done on the topic at hand. The literature review may also include some analysis and interpretation. A literature review is not a summary of every piece of scholarly research on a topic.

Why are literature reviews useful?

Literature reviews can be very helpful for newer researchers or those unfamiliar with a field by synthesizing the existing research on a given topic, providing the reader with connections and relationships among previous scholarship. Reviews can also be useful to veteran researchers by identifying potentials gaps in the research or steering future research questions toward unexplored areas. If a literature review is part of a scholarly article, it should include an explanation of how the current article adds to the conversation. (From: https://researchguides.drake.edu/englit/criticism)

How is a literature review different from a research article?

Research articles: "are empirical articles that describe one or several related studies on a specific, quantitative, testable research question....they are typically organized into four text sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion." Source: https://psych.uw.edu/storage/writing_center/litrev.pdf)

Steps for Writing a Literature Review

1. Identify and define the topic that you will be reviewing.

The topic, which is commonly a research question (or problem) of some kind, needs to be identified and defined as clearly as possible. You need to have an idea of what you will be reviewing in order to effectively search for references and to write a coherent summary of the research on it. At this stage it can be helpful to write down a description of the research question, area, or topic that you will be reviewing, as well as to identify any keywords that you will be using to search for relevant research.

2. Conduct a Literature Search

Use a range of keywords to search databases such as PsycINFO and any others that may contain relevant articles. You should focus on peer-reviewed, scholarly articles . In SuperSearch and most databases, you may find it helpful to select the Advanced Search mode and include "literature review" or "review of the literature" in addition to your other search terms. Published books may also be helpful, but keep in mind that peer-reviewed articles are widely considered to be the “gold standard” of scientific research. Read through titles and abstracts, select and obtain articles (that is, download, copy, or print them out), and save your searches as needed. Most of the databases you will need are linked to from the Cowles Library Psychology Research guide .

3. Read through the research that you have found and take notes.

Absorb as much information as you can. Read through the articles and books that you have found, and as you do, take notes. The notes should include anything that will be helpful in advancing your own thinking about the topic and in helping you write the literature review (such as key points, ideas, or even page numbers that index key information). Some references may turn out to be more helpful than others; you may notice patterns or striking contrasts between different sources; and some sources may refer to yet other sources of potential interest. This is often the most time-consuming part of the review process. However, it is also where you get to learn about the topic in great detail. You may want to use a Citation Manager to help you keep track of the citations you have found.

4. Organize your notes and thoughts; create an outline.

At this stage, you are close to writing the review itself. However, it is often helpful to first reflect on all the reading that you have done. What patterns stand out? Do the different sources converge on a consensus? Or not? What unresolved questions still remain? You should look over your notes (it may also be helpful to reorganize them), and as you do, to think about how you will present this research in your literature review. Are you going to summarize or critically evaluate? Are you going to use a chronological or other type of organizational structure? It can also be helpful to create an outline of how your literature review will be structured.

5. Write the literature review itself and edit and revise as needed.

The final stage involves writing. When writing, keep in mind that literature reviews are generally characterized by a summary style in which prior research is described sufficiently to explain critical findings but does not include a high level of detail (if readers want to learn about all the specific details of a study, then they can look up the references that you cite and read the original articles themselves). However, the degree of emphasis that is given to individual studies may vary (more or less detail may be warranted depending on how critical or unique a given study was). After you have written a first draft, you should read it carefully and then edit and revise as needed. You may need to repeat this process more than once. It may be helpful to have another person read through your draft(s) and provide feedback.

6. Incorporate the literature review into your research paper draft. (note: this step is only if you are using the literature review to write a research paper. Many times the literature review is an end unto itself).

After the literature review is complete, you should incorporate it into your research paper (if you are writing the review as one component of a larger paper). Depending on the stage at which your paper is at, this may involve merging your literature review into a partially complete Introduction section, writing the rest of the paper around the literature review, or other processes.

These steps were taken from: https://psychology.ucsd.edu/undergraduate-program/undergraduate-resources/academic-writing-resources/writing-research-papers/writing-lit-review.html#6.-Incorporate-the-literature-r

- << Previous: Find Streaming Video

- Next: Organizations, Associations, Societies >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.drake.edu/psychology

- 2507 University Avenue

- Des Moines, IA 50311

- (515) 271-2111

Trouble finding something? Try searching , or check out the Get Help page.

Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library

View All Hours | My Library Accounts

Research and Find Materials

Technology and Spaces

Archives and Special Collections

Psychology Research Guide

- Literature Review

- Web Resources

- Library Services

Literature Review Overview

A literature review involves both the literature searching and the writing. The purpose of the literature search is to:

- reveal existing knowledge

- identify areas of consensus and debate

- identify gaps in knowledge

- identify approaches to research design and methodology

- identify other researchers with similar interests

- clarify your future directions for research

List above from Conducting A Literature Search , Information Research Methods and Systems, Penn State University Libraries

A literature review provides an evaluative review and documentation of what has been published by scholars and researchers on a given topic. In reviewing the published literature, the aim is to explain what ideas and knowledge have been gained and shared to date (i.e., hypotheses tested, scientific methods used, results and conclusions), the weakness and strengths of these previous works, and to identify remaining research questions: A literature review provides the context for your research, making clear why your topic deserves further investigation.

Before You Search

- Select and understand your research topic and question.

- Identify the major concepts in your topic and question.

- Brainstorm potential keywords/terms that correspond to those concepts.

- Identify alternative keywords/terms (narrower, broader, or related) to use if your first set of keywords do not work.

- Determine (Boolean*) relationships between terms.

- Begin your search.

- Review your search results.

- Revise & refine your search based on the initial findings.

*Boolean logic provides three ways search terms/phrases can be combined, using the following three operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

Search Process

The type of information you want to find and the practices of your discipline(s) drive the types of sources you seek and where you search.

For most research you will use multiple source types such as: annotated bibliographies; articles from journals, magazines, and newspapers; books; blogs; conference papers; data sets; dissertations; organization, company, or government reports; reference materials; systematic reviews; archival materials; curriculum materials; and more. It can be helpful to develop a comprehensive approach to review different sources and where you will search for each. Below is an example approach.

Utilize Current Awareness Services Identify and browse current issues of the most relevant journals for your topic; Setup email or RSS Alerts, e.g., Journal Table of Contents, Saved Searches

Consult Experts Identify and search for the publications of or contact educators, scholars, librarians, employees etc. at schools, organizations, and agencies

- Annual Reviews and Bibliographies e.g., Annual Review of Psychology

- Internet e.g., Discussion Groups, Listservs, Blogs, social networking sites

- Grant Databases e.g., Foundation Directory Online, Grants.gov

- Conference Proceedings e.g., International Psychological Applications Conference and Trends (InPACT), The European Conference on Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences via IAFOR Research Archive

- Newspaper Indexes e.g., Access World News, Ethnic NewsWatch, New York Times Historical

- Journal Indexes/Databases and EJournal Packages e.g., PsycArticles, ScienceDirect

- Citation Indexes e.g., PsycINFO, Psychiatry Online

- Specialized Data e.g., American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment survey data, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive

- Book Catalogs – e.g., local library catalog or discovery search, WorldCat

- Library Web Scale Discovery Service e.g., OneSearch

- Web Search Engines e.g., Google, Yahoo

- Digital Collections e.g., Archives & Special Collections Digital Collections, Archives of the History of American Psychology

- Associations/Community groups/Institutions/Organizations e.g., American Psychological Association

Remember there is no one portal for all information!

Database Searching Videos, Guides, and Examples

- Comprehensive guide to the database

- Sample Searches

- Searchable Fields

- Education topic guide

- Child Development topic guide

ProQuest (platform for ERIC, PsycINFO, and Dissertations & Theses Global databases, among other databases) search videos:

- Basic Search

- Advanced Search

- Search Results

- Performing Basic Searches

- Performing Advanced Searches

- Search Tips

If you are new to research , check out the Searching for Information tutorials and videos for foundational information.

Finding Empirical Studies

In ERIC : Check the box next to “143: Reports - Research” under "Document type" from the Advanced Search page

In PsycINFO : Check the box next to “Empirical Study” under "Methodology" from the Advanced Search page

In OneSearch : There is not a specific way to limit to empirical studies in OneSearch, you can limit your search results to peer-reviewed journals and or dissertations, and then identify studies by reading the source abstract to determine if you’ve found an empirical study or not.

Summarize Studies in a Meaningful Way

The Writing and Public Speaking Center at UM provides not only tutoring but many other resources for writers and presenters. Three with key tips for writing a literature review are:

- Literature Reviews Defined

- Tracking, Organizing, and Using Sources

- Organizing and Integrating Sources

If you are new to research , check out the Presenting Research and Data tutorials and videos for foundational information. You may also want to consult the Purdue OWL Academic Writing resources or APA Style Workshop content.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Web Resources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 1:20 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lib.umt.edu/psychology

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.3 Reviewing the Research Literature

Learning objectives.

- Define the research literature in psychology and give examples of sources that are part of the research literature and sources that are not.

- Describe and use several methods for finding previous research on a particular research idea or question.

Reviewing the research literature means finding, reading, and summarizing the published research relevant to your question. An empirical research report written in American Psychological Association (APA) style always includes a written literature review, but it is important to review the literature early in the research process for several reasons.

- It can help you turn a research idea into an interesting research question.

- It can tell you if a research question has already been answered.

- It can help you evaluate the interestingness of a research question.

- It can give you ideas for how to conduct your own study.

- It can tell you how your study fits into the research literature.

What Is the Research Literature?

The research literature in any field is all the published research in that field. The research literature in psychology is enormous—including millions of scholarly articles and books dating to the beginning of the field—and it continues to grow. Although its boundaries are somewhat fuzzy, the research literature definitely does not include self-help and other pop psychology books, dictionary and encyclopedia entries, websites, and similar sources that are intended mainly for the general public. These are considered unreliable because they are not reviewed by other researchers and are often based on little more than common sense or personal experience. Wikipedia contains much valuable information, but the fact that its authors are anonymous and its content continually changes makes it unsuitable as a basis of sound scientific research. For our purposes, it helps to define the research literature as consisting almost entirely of two types of sources: articles in professional journals, and scholarly books in psychology and related fields.

Professional Journals

Professional journals are periodicals that publish original research articles. There are thousands of professional journals that publish research in psychology and related fields. They are usually published monthly or quarterly in individual issues, each of which contains several articles. The issues are organized into volumes, which usually consist of all the issues for a calendar year. Some journals are published in hard copy only, others in both hard copy and electronic form, and still others in electronic form only.

Most articles in professional journals are one of two basic types: empirical research reports and review articles. Empirical research reports describe one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors. They introduce a research question, explain why it is interesting, review previous research, describe their method and results, and draw their conclusions. Review articles summarize previously published research on a topic and usually present new ways to organize or explain the results. When a review article is devoted primarily to presenting a new theory, it is often referred to as a theoretical article .

Figure 2.6 Small Sample of the Thousands of Professional Journals That Publish Research in Psychology and Related Fields

Most professional journals in psychology undergo a process of peer review . Researchers who want to publish their work in the journal submit a manuscript to the editor—who is generally an established researcher too—who in turn sends it to two or three experts on the topic. Each reviewer reads the manuscript, writes a critical review, and sends the review back to the editor along with his or her recommendations. The editor then decides whether to accept the article for publication, ask the authors to make changes and resubmit it for further consideration, or reject it outright. In any case, the editor forwards the reviewers’ written comments to the researchers so that they can revise their manuscript accordingly. Peer review is important because it ensures that the work meets basic standards of the field before it can enter the research literature.

Scholarly Books

Scholarly books are books written by researchers and practitioners mainly for use by other researchers and practitioners. A monograph is written by a single author or a small group of authors and usually gives a coherent presentation of a topic much like an extended review article. Edited volumes have an editor or a small group of editors who recruit many authors to write separate chapters on different aspects of the same topic. Although edited volumes can also give a coherent presentation of the topic, it is not unusual for each chapter to take a different perspective or even for the authors of different chapters to openly disagree with each other. In general, scholarly books undergo a peer review process similar to that used by professional journals.

Literature Search Strategies

Using psycinfo and other databases.

The primary method used to search the research literature involves using one or more electronic databases. These include Academic Search Premier, JSTOR, and ProQuest for all academic disciplines, ERIC for education, and PubMed for medicine and related fields. The most important for our purposes, however, is PsycINFO , which is produced by the APA. PsycINFO is so comprehensive—covering thousands of professional journals and scholarly books going back more than 100 years—that for most purposes its content is synonymous with the research literature in psychology. Like most such databases, PsycINFO is usually available through your college or university library.

PsycINFO consists of individual records for each article, book chapter, or book in the database. Each record includes basic publication information, an abstract or summary of the work, and a list of other works cited by that work. A computer interface allows entering one or more search terms and returns any records that contain those search terms. (These interfaces are provided by different vendors and therefore can look somewhat different depending on the library you use.) Each record also contains lists of keywords that describe the content of the work and also a list of index terms. The index terms are especially helpful because they are standardized. Research on differences between women and men, for example, is always indexed under “Human Sex Differences.” Research on touching is always indexed under the term “Physical Contact.” If you do not know the appropriate index terms, PsycINFO includes a thesaurus that can help you find them.

Given that there are nearly three million records in PsycINFO, you may have to try a variety of search terms in different combinations and at different levels of specificity before you find what you are looking for. Imagine, for example, that you are interested in the question of whether women and men differ in terms of their ability to recall experiences from when they were very young. If you were to enter “memory for early experiences” as your search term, PsycINFO would return only six records, most of which are not particularly relevant to your question. However, if you were to enter the search term “memory,” it would return 149,777 records—far too many to look through individually. This is where the thesaurus helps. Entering “memory” into the thesaurus provides several more specific index terms—one of which is “early memories.” While searching for “early memories” among the index terms returns 1,446 records—still too many too look through individually—combining it with “human sex differences” as a second search term returns 37 articles, many of which are highly relevant to the topic.

Depending on the vendor that provides the interface to PsycINFO, you may be able to save, print, or e-mail the relevant PsycINFO records. The records might even contain links to full-text copies of the works themselves. (PsycARTICLES is a database that provides full-text access to articles in all journals published by the APA.) If not, and you want a copy of the work, you will have to find out if your library carries the journal or has the book and the hard copy on the library shelves. Be sure to ask a librarian if you need help.

Using Other Search Techniques

In addition to entering search terms into PsycINFO and other databases, there are several other techniques you can use to search the research literature. First, if you have one good article or book chapter on your topic—a recent review article is best—you can look through the reference list of that article for other relevant articles, books, and book chapters. In fact, you should do this with any relevant article or book chapter you find. You can also start with a classic article or book chapter on your topic, find its record in PsycINFO (by entering the author’s name or article’s title as a search term), and link from there to a list of other works in PsycINFO that cite that classic article. This works because other researchers working on your topic are likely to be aware of the classic article and cite it in their own work. You can also do a general Internet search using search terms related to your topic or the name of a researcher who conducts research on your topic. This might lead you directly to works that are part of the research literature (e.g., articles in open-access journals or posted on researchers’ own websites). The search engine Google Scholar is especially useful for this purpose. A general Internet search might also lead you to websites that are not part of the research literature but might provide references to works that are. Finally, you can talk to people (e.g., your instructor or other faculty members in psychology) who know something about your topic and can suggest relevant articles and book chapters.

What to Search For

When you do a literature review, you need to be selective. Not every article, book chapter, and book that relates to your research idea or question will be worth obtaining, reading, and integrating into your review. Instead, you want to focus on sources that help you do four basic things: (a) refine your research question, (b) identify appropriate research methods, (c) place your research in the context of previous research, and (d) write an effective research report. Several basic principles can help you find the most useful sources.

First, it is best to focus on recent research, keeping in mind that what counts as recent depends on the topic. For newer topics that are actively being studied, “recent” might mean published in the past year or two. For older topics that are receiving less attention right now, “recent” might mean within the past 10 years. You will get a feel for what counts as recent for your topic when you start your literature search. A good general rule, however, is to start with sources published in the past five years. The main exception to this rule would be classic articles that turn up in the reference list of nearly every other source. If other researchers think that this work is important, even though it is old, then by all means you should include it in your review.

Second, you should look for review articles on your topic because they will provide a useful overview of it—often discussing important definitions, results, theories, trends, and controversies—giving you a good sense of where your own research fits into the literature. You should also look for empirical research reports addressing your question or similar questions, which can give you ideas about how to operationally define your variables and collect your data. As a general rule, it is good to use methods that others have already used successfully unless you have good reasons not to. Finally, you should look for sources that provide information that can help you argue for the interestingness of your research question. For a study on the effects of cell phone use on driving ability, for example, you might look for information about how widespread cell phone use is, how frequent and costly motor vehicle crashes are, and so on.

How many sources are enough for your literature review? This is a difficult question because it depends on how extensively your topic has been studied and also on your own goals. One study found that across a variety of professional journals in psychology, the average number of sources cited per article was about 50 (Adair & Vohra, 2003). This gives a rough idea of what professional researchers consider to be adequate. As a student, you might be assigned a much lower minimum number of references to use, but the principles for selecting the most useful ones remain the same.

Key Takeaways

- The research literature in psychology is all the published research in psychology, consisting primarily of articles in professional journals and scholarly books.

- Early in the research process, it is important to conduct a review of the research literature on your topic to refine your research question, identify appropriate research methods, place your question in the context of other research, and prepare to write an effective research report.

- There are several strategies for finding previous research on your topic. Among the best is using PsycINFO, a computer database that catalogs millions of articles, books, and book chapters in psychology and related fields.

- Practice: Use the techniques discussed in this section to find 10 journal articles and book chapters on one of the following research ideas: memory for smells, aggressive driving, the causes of narcissistic personality disorder, the functions of the intraparietal sulcus, or prejudice against the physically handicapped.

Adair, J. G., & Vohra, N. (2003). The explosion of knowledge, references, and citations: Psychology’s unique response to a crisis. American Psychologist, 58 , 15–23.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

University Library

- Research Guides

- Literature Reviews

- Finding Articles

- Finding Books and Media

- Research Methods, Tests, and Statistics

- Citations and APA Style

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Other Resources

- According to Science

- The Scientific Process

- Activity: Scholarly Party

What is a Literature Review?

The scholarly conversation.

A literature review provides an overview of previous research on a topic that critically evaluates, classifies, and compares what has already been published on a particular topic. It allows the author to synthesize and place into context the research and scholarly literature relevant to the topic. It helps map the different approaches to a given question and reveals patterns. It forms the foundation for the author’s subsequent research and justifies the significance of the new investigation.

A literature review can be a short introductory section of a research article or a report or policy paper that focuses on recent research. Or, in the case of dissertations, theses, and review articles, it can be an extensive review of all relevant research.

- The format is usually a bibliographic essay; sources are briefly cited within the body of the essay, with full bibliographic citations at the end.

- The introduction should define the topic and set the context for the literature review. It will include the author's perspective or point of view on the topic, how they have defined the scope of the topic (including what's not included), and how the review will be organized. It can point out overall trends, conflicts in methodology or conclusions, and gaps in the research.

- In the body of the review, the author should organize the research into major topics and subtopics. These groupings may be by subject, (e.g., globalization of clothing manufacturing), type of research (e.g., case studies), methodology (e.g., qualitative), genre, chronology, or other common characteristics. Within these groups, the author can then discuss the merits of each article and analyze and compare the importance of each article to similar ones.

- The conclusion will summarize the main findings, make clear how this review of the literature supports (or not) the research to follow, and may point the direction for further research.

- The list of references will include full citations for all of the items mentioned in the literature review.

Key Questions for a Literature Review

A literature review should try to answer questions such as

- Who are the key researchers on this topic?

- What has been the focus of the research efforts so far and what is the current status?

- How have certain studies built on prior studies? Where are the connections? Are there new interpretations of the research?

- Have there been any controversies or debate about the research? Is there consensus? Are there any contradictions?

- Which areas have been identified as needing further research? Have any pathways been suggested?

- How will your topic uniquely contribute to this body of knowledge?

- Which methodologies have researchers used and which appear to be the most productive?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How does your particular topic fit into the larger context of what has already been done?

- How has the research that has already been done help frame your current investigation ?

Examples of Literature Reviews

Example of a literature review at the beginning of an article: Forbes, C. C., Blanchard, C. M., Mummery, W. K., & Courneya, K. S. (2015, March). Prevalence and correlates of strength exercise among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors . Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), 118+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.sonoma.idm.oclc.org/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&sw=w&u=sonomacsu&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA422059606&asid=27e45873fddc413ac1bebbc129f7649c Example of a comprehensive review of the literature: Wilson, J. L. (2016). An exploration of bullying behaviours in nursing: a review of the literature. British Journal Of Nursing , 25 (6), 303-306. For additional examples, see:

Galvan, J., Galvan, M., & ProQuest. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (Seventh ed.). [Electronic book]

Pan, M., & Lopez, M. (2008). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Pub. [ Q180.55.E9 P36 2008]

Useful Links

- Write a Literature Review (UCSC)

- Literature Reviews (Purdue)

- Literature Reviews: overview (UNC)

- Review of Literature (UW-Madison)

Evidence Matrix for Literature Reviews

The Evidence Matrix can help you organize your research before writing your lit review. Use it to identify patterns and commonalities in the articles you have found--similar methodologies ? common theoretical frameworks ? It helps you make sure that all your major concepts covered. It also helps you see how your research fits into the context of the overall topic.

- Evidence Matrix Special thanks to Dr. Cindy Stearns, SSU Sociology Dept, for permission to use this Matrix as an example.

- << Previous: Citations and APA Style

- Next: Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 2:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sonoma.edu/psychology

- Macquarie University Library

- Subject and Research Guides

Psychological Sciences

- Literature Reviews

- Databases & Journals

- Books and Reference Sources

- Search, Select, Evaluate

- Referencing

- Research Tools

- Tests and Measurements

- Master of Professional Psychology: PSYP8910

- Psychology Honours

Getting started with your Literature Review

- Introduction

- What is a good literature review?

- Future proofing

A literature review is a comprehensive and critical review of literature that provides the theoretical foundation of your chosen topic.

A review will demonstrate that an exhaustive search for literature has been undertaken. It might be used for a thesis, a report, a research essay or a study.

A good literature review is a critical component of academic research, providing a comprehensive and systematic analysis of existing scholarly works on a specific topic. Here are the key elements that make up a good literature review:

Focus and clarity: A good literature review has a clear and well-defined research question or objective. It focuses on a specific topic and provides a coherent and structured analysis of the relevant literature.

I n-depth research: A comprehensive literature review involves an extensive search of relevant sources, including academic journals, books, and reputable online databases. It ensures that a wide range of perspectives and findings are considered.

Critical evaluatio n: A good literature review involves a critical assessment of the quality, credibility, and relevance of the selected sources. It evaluates the methodologies, strengths, weaknesses, and limitations of each study to determine their impact on the overall research.

Synthesis and analysis : A literature review should go beyond summarizing individual studies. It involves synthesizing and analyzing the findings, identifying patterns, themes, and gaps in the existing literature, and presenting a coherent narrative that connects different works.

Contribution to knowledg e: A good literature review not only summarizes existing research but also contributes to the knowledge base. It identifies gaps, inconsistencies, or unresolved debates in the field and suggests avenues for further research.

Clear and concise writing : A well-written literature review presents complex ideas in a clear, concise, and organized manner. It uses appropriate language, avoids jargon, and maintains a logical flow of information.

Proper citation and referencing: Accurate citation and referencing of the reviewed sources are crucial for maintaining academic integrity. Following the appropriate referencing style guidelines ensures consistency and allows readers to access the cited works.

In summary, a good literature review demonstrates a thorough understanding of the topic, critically engages with existing literature, and offers valuable insights for future research.

Where should you search?

The Library uses MultiSearch as an access point to our subscriptions and resources. Using MultiSearch is a good place to start.

You can also search directly in databases. Every discipline has specialist databases and there are also good multidisciplinary databases such as Scopus . Check the Databases page on this guide or ask your Faculty Librarian for advice.

You might also like to consider statistics, government publications or conference proceedings. This will depend on the question you're researching.

What should you read?

Not everything!

- Skim the title, the keywords, the abstract ... know when to pass on something and move on.

- Also know when to stop your literature review. When you start seeing the same material repeated in searches, or no new ideas or perspectives, maybe you have it covered.

Evaluating Literature

You will need to read critically when assessing material for inclusion in your literature review. Each piece of information you look at (whether a journal article, a book, a video, or something else) should be assessed.

- Is the material current?

- Does it have a bias (why was is published)?

- Is the author authoritative?

- Is the journal well regarded in the field (peer reviewed journals are the gold standard but other journals are worthy too).

- Does it provide enough coverage of the topic, or is it basic?

- Will books or journal articles be most useful for your interest area - or do you need to find other materials like government publications, or primary sources?

Analyse the Literature

Once you've read widely on your subject, stop to consider what new insights this knowledge has provided.

- Can you see any ideas emerging more strongly than others?

- Have you changed your position since starting your reading? Perhaps the evidence has made you reconsider your starting viewpoint - or it might have made you more committed to it. However, you should read with an open mind, and be prepared to change your thinking if the evidence points that way.

- Make note of a few points every time you read something. Key arguments or themes. Perhaps a note of ideas you'd like to explore more. You might want to attach this information in the same file we've mentioned in the 'future proofing' tab.

Keep a search diary

Set up a document or spreadsheet to record where you've searched, and also the search strategies you've used. Record the search terms and also the places which have served you well. For instance, is there a particular database which had good coverage?

You may need to repeat searches in the future and this information will help. It might also be requested by your supervisor.

Saving alerts

There are many options for setting up alerts which will help you keep track of new publications by a journal, or an author who is key in your research area, or even when other people cite the papers you have noted (maybe their work will be of interest to you).

These include:

- Table of contents (TOC)

- Citation alerts

- Topic or subject alerts

- Author alert

Developing a comprehensive search strategy

- Before you start

1. Consider the guidance in the "getting started" box above before starting your search.

2. Develop your research question or need.

3. Set up your search diary to record your progress and as a reference guide to come back to.

1. Identify the major concepts from your research question or topic.

Let's say that our topic is: How do alternative energy sources play a role in climate change?

The major concepts will be

- a lternative energy sources

- climate change

2. List synonyms or alternative terms for each concept and organise them in a table like the one below - using a column for each major concept. Use as many columns as you have major concepts.

Tools and tips to assist with this process:

- Run scoping searches for your topic in your favourite database or databases such as Google Scholar or Scopus to identify how the literature can express your concepts. Scan titles, subject headings (if any) and abstracts for words describing the same things as your major concepts.

- Text mining tools including PubMed Reminer especially if you are using a database with MeSH such as Medline or Cochrane. There are many others however.

- As you find something new, add it to the appropriate column on your list to incorporate later in your search.

Create your search strategy from the concepts, synonyms, phrases etc in your Concept Grid

Identify the best databases for your topic. Check the databases tab in the left menu on this Guide.

N.B.The syntax/search tools for your search may depend on the particular database you are searching in. Most databases have a Help screen to assist.

However, the majority of databases will use Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and other commonly used search tools :

- Use "OR" to connect each of your synonyms (eg "climate change" OR "global warming")

- Use "AND" to connect each of your concepts.

- (Use "NOT" to exclude terms - but these should be used sparingly as they can knock out useful results.)

- Use the Truncation symbol * at the end of word roots which might have alternative endings eg: manag* will retrieve: manage; management; managing, managerial etc.

- Use quotes to keep together words of phrases (eg "climate change")

- Group your concepts algebraically using parentheses.

- Consider, is your term alternatively expressed as two words? (eg hydro electricity or hydroelectricity (you should include both!))

So with our question/topic: How do alternative energy sources play a role in climate change?

After identifying our major concepts and synonyms for each and employing some of the tools mentioned above, our constructed search strategy might look something like this:

("alternative energ*" OR "wind power" OR "Solar power" OR "Solar energy" OR Renewabl* OR geothermal OR hydroelectricity OR "hydro electricity") AND ("climate change" OR "global* warm*" or "greenhouse gas*" or "green house gas*")

3. Be prepared to revise, reassess and refine your search strategies after you have run your initial searches to ensure you get the best possible results. If you retrieve too many false results or "noise", try to analyse why. For example, you may have used a word which has alternative meanings.

If you have too many results, you can either add another concept or remove some synonyms

If you have too few results, try searching with fewer concepts (identify the least most important to omit) or add more synonyms.

Your Faculty or Clinical Librarian will be able to assist with this process.

Further reading

- Other sources

- Journal Articles

- Books and Chapters

Related Guides

- Systematic Reviews

- Using MultiSearch

We have guidance on Literature Reviews in StudyWISE . This guides focuses on the writing skills associated with Literature Reviews.

You'll find it on iLearn (Macquarie University's learning portal)

- << Previous: Search, Select, Evaluate

- Next: Referencing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 11:30 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mq.edu.au/psychology

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Psychology 140: developmental psychology: the literature review.

- The Literature Review

- Off-Campus Access

- Finding Articles

- Citations & Bibliographic Software (Zotero)

http://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/psyc140

Quick links.

- Google Scholar This link opens in a new window Search across many disciplines and sources including articles, theses, books, abstracts and court opinions, from academic publishers, professional societies, online repositories, universities and other web sites. more... less... Lists journal articles, books, preprints, and technical reports in many subject areas (though more specialized article databases may cover any given field more completely). Can be used with "Get it at UC" to access the full text of many articles.

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a survey of research on a given topic. It allows you see what has already been written on a topic so that you can draw on that research in your own study. By seeing what has already been written on a topic you will also know how to distinguish your research and engage in an original area of inquiry.

Why do a Literature Review?

A literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You will identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

Elements of a Successful Literature Review

According to Byrne's What makes a successful literature review? you should follow these steps:

- Identify appropriate search terms.

- Search appropriate databases to identify articles on your topic.

- Identify key publications in your area.

- Search the web to identify relevant grey literature. (Grey literature is often found in the public sector and is not traditionally published like academic literature. It is often produced by research organizations.)

- Scan article abstracts and summaries before reading the piece in full.

- Read the relevant articles and take notes.

- Organize by theme.

- Write your review .

from Byrne, D. (2017). What makes a successful literature review?. Project Planner . 10.4135/9781526408518. (via SAGE Research Methods )

Research help

Email : Email your research questions to the Library.

Appointments : Schedule a 30-minute research meeting with a librarian.

Find a subject librarian : Find a library expert in your specific field of study.

Research guides on your topic : Learn more about resources for your topic or subject.

- Next: Off-Campus Access >>

- Last Updated: Feb 28, 2024 3:04 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/psyc140

- SUNY Oswego, Penfield Library

- Resource Guides

Psychology Research Guide

- Literature Reviews

- Research Starters

- Find Tests and Measures

Conducting Literature Reviews

Finding literature reviews in psycinfo, more help on conducting literature reviews.

- How to Read a Scientific Article

- Citing Sources

- Peer Review

Quick Links

- Penfield Library

- Research Guides

- A-Z List of Databases & Indexes

The APA definition of a literature review (from http://www.apa.org/databases/training/method-values.html ):

Survey of previously published literature on a particular topic to define and clarify a particular problem; summarize previous investigations; and to identify relations, contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the literature, and suggest the next step in solving the problem.

Literature Reviews should:

- Key concepts that are being researched

- The areas that are ripe for more research—where the gaps and inconsistencies in the literature are

- A critical analysis of research that has been previously conducted

- Will include primary and secondary research

- Be selective—you’ll review many sources, so pick the most important parts of the articles/books.

- Introduction: Provides an overview of your topic, including the major problems and issues that have been studied.

- Discussion of Methodologies: If there are different types of studies conducted, identifying what types of studies have been conducted is often provided.

- Identification and Discussion of Studies: Provide overview of major studies conducted, and if there have been follow-up studies, identify whether this has supported or disproved results from prior studies.

- Identification of Themes in Literature: If there has been different themes in the literature, these are also discussed in literature reviews. For example, if you were writing a review of treatment of OCD, cognitive-behavioral therapy and drug therapy would be themes to discuss.

- Conclusion/Discussion—Summarize what you’ve found in your review of literature, and identify areas in need of further research or gaps in the literature.

Because literature reviews are a major part of research in psychology, Psycinfo allows you to easily limit to literature reviews. In the advanced search screen, you can select "literature review" as the methodology.

Now all you'll need to do is enter your search terms, and your results should show you many literature reviews conducted by professionals on your topic.

When you find an literature review article that is relevant to your topic, you should look at who the authors cite and who is citing the author, so that you can begin to use their research to help you locate sources and conduct your own literature review. The best way to do that is to use the "Cited References" and "Times Cited" links in Psycinfo, which is pictured below.

This article on procrastination has 423 references, and 48 other articles in psycinfo are citing this literature review. And, the citations are either available in full text or to request through ILL. Check out the article "The Nature of Procrastination" to see how these features work.

By searching for existing literature reviews, and then using the references of those literature reviews to begin your own literature search, you can efficiently gather the best research on a topic. You'll want to keep in mind that you'll need to summarize and analyze the articles you read, and won't be able to use every single article you choose.

You can use the search box below to get started.

Adelphi Library's tutorial, Conducting a Literature Review in Education and the Behavioral Sciences covers how to gather sources from library databases for your literature review.

The University of Toronto also provides "A Few Tips on Conducting a Literature Review" that offers some good advice and questions to ask when conducting a literature review.

Purdue University's Online Writing Lab (OWL) has several resources that discuss literature reviews:

http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/666/01/

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/994/04/ (for grad students, but is still offers some good tips and advice for anyone writing a literature review)

Journal articles (covers more than 1,700 periodicals), chapters, books, dissertations and reports on psychology and related fields.

- PsycINFO This link opens in a new window

- << Previous: Handbooks

- Next: How to Read a Scientific Article >>

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

A Systematic Review of Trajectories of Clinically Relevant Distress Amongst Adults with Cancer: Course and Predictors

- Open access

- Published: 05 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Leah Curran ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6070-1568 1 , 2 ,

- Alison Mahoney 3 , 4 &

- Bradley Hastings 1

215 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

To improve interventions for people with cancer who experience clinically relevant distress, it is important to understand how distress evolves over time and why. This review synthesizes the literature on trajectories of distress in adult patients with cancer. Databases were searched for longitudinal studies using a validated clinical tool to group patients into distress trajectories. Twelve studies were identified reporting trajectories of depression, anxiety, adjustment disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder. Heterogeneity between studies was high, including the timing of baseline assessments and follow-up intervals. Up to 1 in 5 people experienced persistent depression or anxiety. Eight studies examined predictors of trajectories; the most consistent predictor was physical symptoms or functioning. Due to study methodology and heterogeneity, limited conclusions could be drawn about why distress is maintained or emerges for some patients. Future research should use valid clinical measures and assess theoretically driven predictors amendable to interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

A detailed description of the distress trajectory from pre- to post-treatment in breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Post-traumatic growth after cancer: a scoping review of qualitative research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Unsurprisingly, a diagnosis of cancer is often associated with psychological distress, such as symptoms of depression, anxiety, traumatic stress, fear of cancer progression or recurrence (FCR), or death anxiety. While longitudinal studies suggest that rates of distress generally improve over time, a substantial proportion of patients continue to experience clinically relevant distress (Calman et al., 2021 ; Henry et al., 2019 ; Krebber et al., 2014 ; Savard & Ivers, 2013 ). For mental health clinicians, understanding patients’ likely distress trajectory, specifically the timepoints at which distress is likely to emerge and whether the distress is likely to remain clinically relevant, is critical for the design and implementation of mental health and systemic interventions.

There are several gaps in the existing literature about how and why distress evolves amongst cancer patients. Firstly, longitudinal research has mainly reported prevalence data (Niedzwiedz et al., 2019 ), which conflates distress trajectories across different cancer cohorts and is not informative about how distress trajectories evolve for individual patients. For instance, there is evidence that distress increases longitudinally amongst younger patients and those with cancers that are more likely to recur, such as ovarian or oesophageal cancers (Liu et al., 2022 ; Starreveld et al., 2018 ; Watts et al., 2015 ). Additionally, there is scant longitudinal research regarding how distress evolves for individuals with advanced disease receiving novel therapies, who are likely at greater risk for psychological distress (Thewes et al., 2017 ). For example, amongst patients with advanced melanoma who achieved remission on immunotherapy, 64% had clinical levels of anxiety or depression at one point during the following year despite having no active disease (Rogiers et al., 2020 ). However, the distress trajectories and factors associated with recovered or persistent distress could not be ascertained by the data.

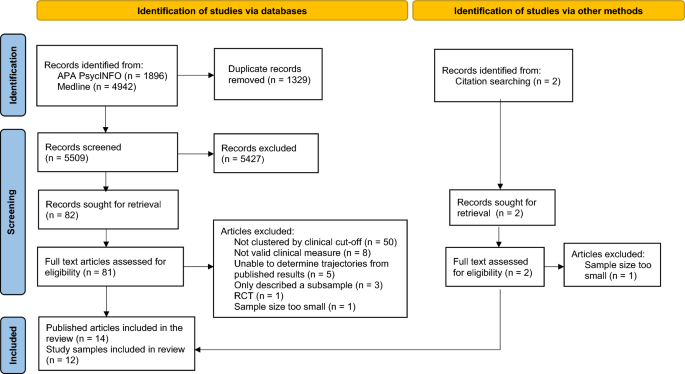

Secondly, longitudinal studies that group patients into distress trajectories vary in method. Some have used clinical cut-off scores and assessed individuals longitudinally at two time points (e.g. Linden et al., 2015 ), resulting in four clinically meaningful trajectories of distress: (1) non-cases (not meeting clinical criteria at either time point), (2) recovered (clinically significant distress at the first timepoint only), (3) persistent (meeting clinical criteria at both time points), and 4) emerging (clinically significant distress at the second timepoint only). In longitudinal studies conducted over more than two timepoints a fluctuating trajectory of distress may also be evident where a person meets clinical criteria at some, but not all, assessments (e.g., Mols et al., 2018 ). However, the majority of longitudinal studies of distress trajectories have used statistical methods, such as latent class growth analysis, to group participants into trajectories rather than utilising pre-determined clinical cut-off scores. Consequently, the number of trajectories identified, and the participants assigned to each trajectory, will differ according to the method used (e.g., Custers et al., 2020 ). Also, statistical analyses identify patterns in samples, so if the average outcome score is low, a statistically derived “persistently high” trajectory may include patients below a clinically meaningful threshold (e.g., Stanton et al., 2015 ). Since distress trajectories identified by statistical methods are difficult to interpret clinically, they have limited utility in informing clinical questions of how and why distress trajectories differ for individual patients.