- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Research skills, searching the literature.

- Note making for dissertations

- Research Data Management

- Copyright and licenses

- Publishing in journals

- Publishing academic books

- Depositing your thesis

- Research metrics

- Build your online profile

- Finding support

Welcome to this module about how to find what you need when searching academic literature

- Planning your search - working out what you want to look for and where you might find it

- Carrying our your search - using different resources to find materials on your research topic

- Evaluating your search and results - deciding if you have found what you need and how they are relevant to your research

- Managing your results - using tools and alerts manage what you have now and what interesting new research might be coming out

- Keeping up to date - using tools to keep up to date with new literature as it is produced and published

Academic information can take many forms such as textbooks, journal articles, datasets, software and much more. In this module we will be focusing on searching for journal articles through different services, including the many academic databases that are available to members of the University of Cambridge. As every discipline will have slightly different ways of sharing and talking about research, we will be covering the fundamental skills around searching the literature. For more subject-specialist help, seek out the relevant library team via our Libraries Directory listings .

To complete this section, you will need:

- Approximately 60 minutes.

- Access to the internet. All the resources used here are available freely.

- Some equipment for jotting down your thoughts, a pen and paper will do, or your phone or another electronic device.

Planning your search

As tempting as it is to start searching, it is important to take some time to plan out your search first, as spending a few minutes making a plan at the start will help you find all the relevant information as efficiently as possibly. There are a range of different techniques you can use for finding the information you need. Considering the techniques you will use and where you will use them can be described as developing or creating a "Search Strategy". Watch this video from the Engineering Library to learn how to create a great search strategy.

Activity - Building your search strategy

Now you have had a chance to think about planning a search strategy, you could think about developing a search strategy for your own research question using our Search Strategy tool . This tool aims to provide prompts for you to build your search strategy to help plan your literature searching. At the end of the activity you will be given the option to email your search strategy to yourself so you have a copy to work from as you progress with your research.

Carrying out your search

Now you have a plan for searching, you can start putting your keywords into a database to see what you find. Remember, what you want to find will influence where you look for it. There are many databases available that cover many different disciplines at once, and others that focus down onto one specific area so consider using several resources together to get really good coverage of your topic.

One good interdisciplinary databases is Scopus. In this video by the Lee Library (Wolfson College), you’ll see the principles we've discussed so far applied in practice. Please note that many databases change how they look from time so if Scopus has changed since you watched this video, the essentials will be the same.

Searching the grey literature

Sometimes you will be working on research that needs you to find what can sometimes be referred to as 'grey literature'. In a nutshell, this kind of literature is anything that has not been produced by a commercial publisher. It can include almost anything including working papers, reports published by government departments, theses and much more. Find these sorts of resources through academic databases is almost impossible as they are often not indexed there. However, many of us have a tool at our fingertips that we use daily to find information - Google!

Google is a very effective search tool, even though it still only indexes a very small proportion of the overall internet. There are techniques to get Google searching to work for you rather than you fighting against its algorithms. Find out more in video from the Biological Sciences Libraries Team!

Knowledge check - what have you remembered so far?

We've covered a lot so you can undertake a quick knowledge check . Answer the questions to see how much you've remembered. If you're not sure about a question, you can revisit the earlier sections to refresh your knowledge

Evaluating your search

Now you've been searching for a little while, it might be worthwhile going back to your original search strategy plan to see if it needs tweaking. What sort of results have you been getting?

You might want to consider the following questions as part of this review:

- Are the results different to what you expected? Why might this be?

- Do you need to refine the search including additional keywords or using post-search filters like dates or topic?

- Are you getting too few results and do you need to broaden the search?

- Is the database suitable for this search, or would there be a more appropriate alternative?

If you are struggling to answer any of these questions, it might be a good time to seek out a subject specialist. As a reminder, you can find a comprehensive listing of the various libraries dotted around the University of Cambridge with many knowledgeable people working within them who will be able to help.

Critically evaluating your results

Even if your search is as good as you can get it right now, and you're definitely using the best resource for your topic, have you taken some time to review the quality of your results? The concept of quality is incredibly subjective, especially depending on your research area. While some people may consider peer review to be a good indicator of rigorous research, others may be more sceptical of it as an overall process.

Consider using a critical evaluation framework to assess what research results you're finding and you can start answering questions around the relevance and quality of a particular piece of work according to your own individual criteria. There are many frameworks out there and the Biological Sciences Libraries Team have a short video looking at one of these called PROMPT from the Open University.

Managing your results

Once you have a set of results that you want to save and keep so you can use them with your research moving forward, managing those resources is a critical next step to ensure that you have them easily to hand and do not lose them at any point during your work. We would strongly recommend that you consider investing in a reference manager to do a lot of this work for you. In essence, a reference manager will help you save results as you work with options for cloud storage of articles, exporting as formatted references for bibliographies and much more!

There are a wide range of reference manager tools out there, with several being free to use, so while we may recommend a few do explore the options yourself to get something that works for you. For an overview of some of the main tools, please visit our Good Academic Practice guide for more information.

Keeping up to date

So far we have considered situations where you are researching a topic at a particular point in time, yet as a researcher you will also need to keep informed about new developments in your field. How can you make sure you capture important new research in the limited time you have available?

With alerts and other such things, there are many options available, some of which we cover in our next video.

Further Resources

We have covered a lot of different things in this module, many of which can be expanded upon and gone into in a lot of depth with a subject expert so here are some resources for you to explore further.

For a complete list of all of the academic databases and resources that the University of Cambridge subscribes to, visit our A-Z Database guide

Visit our dedicated guide on carrying out a systematic review for specialist advice from the Medical Library team

For a comprehensive list of subject libraries across the University of Cambridge , visit our Libraries Directory to find someone to help you with your literature searching needs

There are many training opportunities for researchers across the University of Cambridge, with many sessions advertised on the University Training Booking System . Check it out to see if there is a literature searching session in your research area happening soon. If you can't find one that is relevant to you, ask a subject librarian if they have anything available.

Did you know?

How did you find this Research Skills module

Image Credits: Photo by Daniel Lerman on Unsplash

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Note making for dissertations >>

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2024 9:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/research-skills

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Best Practice for Literature Searching

- Literature Search Best Practice

What is literature searching?

- What are literature reviews?

- Hierarchies of evidence

- 1. Managing references

- 2. Defining your research question

- 3. Where to search

- 4. Search strategy

- 5. Screening results

- 6. Paper acquisition

- 7. Critical appraisal

- Further resources

- Training opportunities and videos

- Join FSTA student advisory board This link opens in a new window

- Chinese This link opens in a new window

- Italian This link opens in a new window

- Persian This link opens in a new window

- Portuguese This link opens in a new window

- Spanish This link opens in a new window

Literature searching is the task of finding relevant information on a topic from the available research literature. Literature searches range from short fact-finding missions to comprehensive and lengthy funded systematic reviews. Or, you may want to establish through a literature review that no one has already done the research you are conducting. If so, a comprehensive search is essential to be sure that this is true.

Whatever the scale, the aim of literature searches is to gain knowledge and aid decision-making. They are embedded in the scientific discovery process. Literature searching is a vital component of what is called "evidence-based practice", where decisions are based on the best available evidence.

What is "literature"?

Research literature writes up research that has been done in order to share it with others around the world. Far more people can read a research article than could ever visit a particular lab, so the article is the vehicle for disseminating the research. A research article describes in detail the research that's been done, and what the researchers think can be concluded from it.

It is important, in literature searching, that you search for research literature . Scientific information is published in different formats for different purposes: in textbooks to teach students; in opinion pieces, sometimes called editorials or commentaries , to persuade peers; in review articles to survey the state of knowledge. An abundance of other literature is available online, but not actually published (by an academic publisher)--this includes things like conference proceedings , working papers, reports and preprints . This type of material is called grey (or gray) literature .

Most of the time what you are looking for for your literature review is research literature (and not opinion pieces, grey literature, or textbook material) that has been published in scholarly peer reviewed journals .

As expertise builds, using a greater diversity of literature becomes more appropriate. For instance, advanced students might use conference proceedings in a literature review to map the direction of new and forthcoming research. The most advanced literature reviews, systematic reviews, need to try to track down unpublished studies to be comprehensive, and a great challenge can be locating not only relevant grey literature, but studies that have been conducted but not published anywhere. If in doubt, always check with a teacher or supervisor about what type of literature you should be including in your search.

Why undertake literature searches?

By undertaking regular literature searches in your area of expertise, or undertaking complex literature reviews, you are:

- Able to provide context for and justify your research

- Exploring new research methods

- Highlighting gaps in existing research

- Checking if research has been done before

- Showing how your research fits with existing evidence

- Identifying flaws and bias in existing research

- Learning about terminology and different concepts related to your field

- Able to track larger trends

- Understanding what the majority of researchers have found on certain questions.

- << Previous: Literature Search Best Practice

- Next: What are literature reviews? >>

- Last Updated: Sep 15, 2023 2:17 PM

- URL: https://ifis.libguides.com/literature_search_best_practice

- My Account |

- StudentHome |

- TutorHome |

- IntranetHome |

- Contact the OU Contact the OU Contact the OU |

- Accessibility Accessibility

Postgraduate

- International

- News & media

- Business & apprenticeships

You are here

Researcher skills, literature searching explained.

- Site Accessibility: Library Research Support

1. What is a literature search?

2. Decide the topic of your search

3. Identify the main concepts in your question

4. Choose a database

What is a literature search?

A literature search is a considered and organised search to find key literature on a topic. To complete a thorough literature search you should:

- define what you are searching for

- decide where to search

- develop a search strategy

- refine your search strategy

- save your search for future use.

For background reading or an introduction to a subject, you can do a shorter and more basic Library search .

Use this guide to work your way through the all the stages of the literature searching process.

You should form a search question before you begin. Reframing your research project into a defined and searchable question will make your literature search more specific and your results more relevant.

Decide the topic of your search

You should start by deciding the topic of your search. This means identifying the broad topic, refining it to establish which particular aspect of the topic interests you, and reframing that topic as a question.

For example:

Broad topic: active learning and engagement in higher education

Main focus topic: international students and online learning

Topic stated as a question: "What is the role of active learning in improving the engagement of international students during online learning?"

Identify the main concepts in your question

Once you have a searchable question, highlight the major concepts. For example: "What is the role of active learning in improving the engagement of international students during online learning ?"

You should then find keywords and phrases to express the different concepts. For example, the concept “active learning” covers a wide range of key terms, including student-based learning, problem solving and paired discussion.

It may be useful to create a concept map. First identify the major concepts within your question and then organise your appropriate key terms.

If you are researching a medicine or health related topic then you might want to use a PICO search model. PICO helps you identify the Patient, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome concepts within your research question.

P atient: Who is the treatment being delivered to? What is happening to the patient?

I ntervention: What treatment is being delivered? What is happening to the patient?

Comparison: How much better is the procedure than another? What are the alternatives?

Outcome: How is the effect measured? What can be achieved?

List synonyms for each concept. You may wish to include variant spellings or endings (plural, singular terms). Exclude parts of the PICO that do not relate to your search question. For example, you may not be drawing any comparisons in your research.

Choose a database

Subject-specific databases are the most effective way to search for journal articles on a topic. However, you can also search the Library for common information sources, such as government documents, grey literature, patents and statistics.

Find the most appropriate databases for your subject

Databases help you to find a broad range of evidence, including peer-reviewed academic articles from all over the world, from many different publishers, and over a long time period.

Databases such as Scopus and Web of Science hold expansive records of research literature, including conference proceedings, letters and grey literature.

Many databases have links to full-text articles where the Library has a subscription.

Other information sources

Go to your subject-specific page to see the most appropriate information sources listed for your subject area. You may need to explore more than one subject page if your topic is multi-disciplinary.

You may find it useful to make a list of which information sources you want to search to find information for your research; a search activity template (DOCX) can help you do this.

- The Research Support Team

- Bibliometrics and alternative metrics

- Researcher visibility

- Advanced Literature Searching

- Reference management tools

Library Research Support team

The Open University

- Study with us

- Supported distance learning

- Funding your studies

- International students

- Global reputation

- Apprenticeships

- Develop your workforce

- Contact the OU

Undergraduate

- Arts and Humanities

- Art History

- Business and Management

- Combined Studies

- Computing and IT

- Counselling

- Creative Writing

- Criminology

- Early Years

- Electronic Engineering

- Engineering

- Environment

- Film and Media

- Health and Social Care

- Health and Wellbeing

- Health Sciences

- International Studies

- Mathematics

- Mental Health

- Nursing and Healthcare

- Religious Studies

- Social Sciences

- Social Work

- Software Engineering

- Sport and Fitness

- Postgraduate study

- Research degrees

- Masters in Art History (MA)

- Masters in Computing (MSc)

- Masters in Creative Writing (MA)

- Masters degree in Education

- Masters in Engineering (MSc)

- Masters in English Literature (MA)

- Masters in History (MA)

- Master of Laws (LLM)

- Masters in Mathematics (MSc)

- Masters in Psychology (MSc)

- A to Z of Masters degrees

- Accessibility statement

- Conditions of use

- Privacy policy

- Cookie policy

- Manage cookie preferences

- Modern slavery act (pdf 149kb)

Follow us on Social media

- Student Policies and Regulations

- Student Charter

- System Status

- Contact the OU Contact the OU

- Modern Slavery Act (pdf 149kb)

© . . .

Library Services

UCL LIBRARY SERVICES

- Guides and databases

- Library skills

Support for dissertations and research projects

Literature searching.

- Resources for your discipline

- Primary sources

- UCL dissertations & theses

- Can't access the resource you need?

- Research methods

- Referencing and reference management

- Writing and digital skills

Further help

Your dissertation or research project will almost certainly require a search for literature on your topic, whether to identify selected research, to undertake a literature review or inform a full systematic review. Literature searches require planning, careful thought about what it is you wish to find out and a robust strategy to ensure you find relevant material.

On this page:

Planning your search.

- Search techniques and developing your search strategy

Literature reviews

Systematic reviews.

Time spent carefully planning your search can save valuable time later on and lead to more relevant results and a more robust search strategy. You should consider the following:

- Analysing your topic and understanding your research question: Carry out a scoping search to help understand your topic and to help define your question more clearly.

- What are the key concepts in your search?

- What terms might be used to describe those concepts? Consider synonyms and alternative spellings.

- If your question relates to health or clinical medicine, you might like to use PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes) to analyse your question:

- Combine your concept terms together using the correct operators , such as AND and OR.

See our Library Skills Essentials guide for support materials and guidance for planning your search, including understanding and defining your topic, and defining search terms.

Search techniques and developing a search strategy

Make sure you are confident about using essential search techniques, including combining search terms, phrase searching and truncation. These will help you find relevant results on your topic. See our guide to search techniques:

- Search techniques

When carrying out a literature search to inform a dissertation or extended piece of research, you will need to think carefully about your search strategy. Have a look at our tutorials and videos to help you develop your literature searching skills:

- Search skills for research: tutorials and videos

When you carry out a literature search you may need to search multiple resources (see Sources and Resources ). Your search strategy will need to be adjusted depending on the resource you are using. For some resources, a simple search will be sufficient, whereas for more complex resources with more content, you may need to develop a sophisticated search strategy, ensuring you use the correct search techniques for that resource. See our guides to selected individual resources for further guidance.

- Search guides to individual resources: bibliographic databases

- What is a literature review?

- Why are literature reviews important?

We also provide support for developing advanced search strategies to ensure comprehensive literature retrieval, including searching for systematic reviews. See our guide to Searching for Systematic Reviews.

- Systematic reviews This guide provides information on systematic review processes and support available from UCL Library Services.

See our library skills training sessions or contact your librarian .

For general enquiries, see Getting Help and contacting us .

Get help and advice with literature searching

- You can email your librarian direct to ask for advice on your search.

- You can also book a virtual appointment with your librarian for more in depth enquiries.

- Email your librarian to request an appointment or fill out our individual consultation request form .

- Find your librarian

- Find your site library Another way to find your local team.

Literature searching training sessions

- View our full calendar and make a booking

Search Explore

Check out our Explore guide to find out more about how to use Explore for your research.

- Explore guide

- << Previous: FAQs

- Next: Sources and resources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 18, 2024 6:08 PM

- URL: https://library-guides.ucl.ac.uk/dissertations

Searching the Literature: The Basics

- Getting Started

- Ask a Question

- Select a Search Resource

- Develop Search Terms

- Execute the Search

- Access/Save Results

- Evaluate & Improve Your Search

- Database Fundamentals This link opens in a new window

- Ovid Medline This link opens in a new window

- CINAHL This link opens in a new window

- Cochrane Library This link opens in a new window

- PubMed This link opens in a new window

- Web of Science This link opens in a new window

- Google Scholar This link opens in a new window

- Additional Resources

What is a Literature Search?

A literature search is the act of gathering existing knowledge or data around a topic or research question.

Regardless of the purpose of your literature search, all searches follow the same basic process:

- Ask a question

- Select a search resource

- Develop search terms

- Execute the search

- Access results

- Evaluate & improve your search

Each page in this guide explores a different step of the process and lays the groundwork for the following steps.

Why Search the Literature?

E.g. "I want to learn more about treatment options available for quitting smoking."

E.g. "I need some statistics for how smoking rates have changed over the last 20 years."

E.g. "I'm designing a research study on the effectiveness of hypnosis for smoking cessation. What's been done before? What areas need further investigation?"

E.g. "I want to gather and synthesize all the existing studies that help answer the following research question: Are support groups more effective than nicotine-replacement products for helping teenagers quit smoking?"

E.g. "What treatment should I recommend to my teenage patient interested in quitting smoking?"

- Next: Ask a Question >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 11:06 AM

- URL: https://hslmcmaster.libguides.com/literature_searching

Address Information

McMaster University 1280 Main Street West HSC 2B Hamilton, Ontario Canada L8S 4K1

Contact Information

Phone: (905) 525-9140 Ext. 22327

Email: [email protected]

Make A Suggestion

Website Feedback

- Plan for research

Find information

- Manage data

- Publish and share

- Research metrics

- Help and site map

Introduction

The literature search process

- Develop an effective search strategy

- Determine the type of information

- Identify where to search

- Search and manage results

- Locate and evaluate

- Keep up-to-date

Library resources and support

Once your research question has been finalised you are ready to search for literature. It is important to be organised in your approach to a literature search. This ensures that you will retrieve relevant information for your research topic.This module describes a six-step approach to finding literature.

- Last Updated: May 9, 2024 8:28 AM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/rstoolkit

Advanced literature searching skills: Introduction

Introduction.

- Starting your search

- Choosing keywords

- Expert searching

- Managing your results

- Referencing and software to help

- How to use Internet sources more effectively and identify high-quality information sources, such as a university library's expert databases.

- Planning an effective search – choosing keywords, considering synonyms, alternative spellings, using search syntax, Boolean logic and truncation.

- Working with the results – filter, sort and evaluate suitability, find new keywords and amend searches – taking a strategic approach.

- Managing search results and exporting references e.g. creating saved searches and alerts; exporting references to bibliographic software.

- Creating and managing citations and references – manually creating references or using 'Cite While You Write' (CWYW) EndNote with Word.

Let's begin with an introduction to the literature searching process and consider the importance of defining your research question.

What is a literature search?

Define your research question(s)

Take, for example, this topic: Are biofuels the answer to falling oil reserves?

You could type this sentence into a database search box, but that is seldom helpful, as the sentence may not contain the most appropriate keywords. Also this single sentence is unlikely to encompass everything that you want to find out. You need to break down the topic into a number of separate questions and then look for the answers. For this example here are some of the questions you could ask:

- What is a biofuel?

- How are they made?

- How much of our fuel is already from biofuel (market share)?

- Could we make enough to replace oil and/or gas?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of using biofuels compared with oil and gas?

- Could we use biofuels for transport?

- What is UK government policy relating to biofuels?

You may find the answers to all of these questions using a single search engine such as Google Scholar or a single Library database, but you are more likely to succeed if you match each question to relevant resources .

Let's move on now to 'starting your search'

- Next: Starting your search >>

- Last Updated: Sep 22, 2021 2:28 PM

- URL: https://library.bath.ac.uk/advanced-research-skills-for-literature-searching

- Library databases

- Library website

Library Guide to Capstone Literature Reviews: Search Skills

Introduction.

In your doctoral capstone project you demonstrate your expertise in your subject area. In the literature review, you show that you are a capable researcher, laying out the current state of research in your field. This requires knowledge of the sources as well as search skills, so that you can locate, retrieve, compare, and synthesize all of the relevant literature.

On this page you will find information on:

- identifying relevant databases

- searching for dissertations

- identifying relevant search terms

- combining search terms

- identifying relevant sources beyond the Walden Library

Identify relevant databases

As you've done research for your courses, you've probably identified a few Library databases that consistently have relevant articles. These databases are a great place to start your literature review research. However, in order to be comprehensive in your research, you'll also want to explore databases outside of your specific subject area.

For example, if you were studying educational leadership and the impact it has on student behavior, here are some of the subject databases that you'd want to search:

- Education databases : to find articles on educational leadership and student behavior

- Business & management databases : to find articles on leadership and its impact on behavior

- Psychology databases : to find articles on what impacts behavior

To learn more about finding subject databases in the Library, please see the Quick Answer on finding databases by subject:

- Quick Answer: How do I find databases by subject?

Search for dissertations

In addition to searching subject databases, you'll want to search the dissertation databases to see if anyone else has done a dissertation on a topic similar to your own. Keep in mind that dissertations can be citation gold mines. If someone else has done research similar to, but not exactly the same, as yours, you can examine their bibliography or reference list. make note of any resources that could be relevant to your own research. You can then locate the original resources cited in the dissertation in order to use them in your own.

In the Walden Library we have two different dissertation search options:

- Dissertations & Theses @ Walden University This database contains the full text of dissertations and theses written by Walden students. It is a great database to search in order to get a feel for what a completed Walden dissertation looks like.

- ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global This database has the full text of over three million dissertations and theses from schools and universities around the world. It will help you determine if anyone else has done research similar to your own.

To learn how to find specific types of capstone projects, please see our Quick Answer that will walk you through that process:

- Quick Answer: What degree codes are used to find completed Walden capstones or dissertations?

If you'd like to see examples of high quality Walden dissertations, please see our Quick Answer on locating award-winning Walden dissertations:

- Quick Answer: Where can I find Walden award-winning dissertations?

Identify search terms

One of the keys to becoming an expert researcher is identifying appropriate search terms or keywords. These allow you to be comprehensive in your searches and find relevant articles in the Library databases.

Break apart your topic

The first step is to break apart your topic into its component parts. For example, if you were researching the impact that school leadership has on the academic progress of at-risk students, your component parts would be:

- school leadership

- academic progress

- at-risk students

Use strategies to create search terms

Once you have broken apart your topic, here are a few strategies that will help you turn each aspect of your topic into relevant search terms :

- brainstorm synonyms

- expand out acronyms

- look at subjects

Brainstorm synonyms

For each aspect of your topic, think of other words or phrases that have a similar meaning. For example, some other terms that could be used to describe school leadership include:

- school administrators

Expand out acronyms

If your topic includes acronyms, like NCLB (No Child Left Behind), you'll want to search using both the acronym and the actual phrase.

Look at subjects

Most of the Library databases assign subjects to materials based on the main topics covered in the materials. These subjects make great search terms, since they will help you find articles on your topic, and not just articles that contain your search terms.

Here is an example of how to find subjects in the ERIC database :

- Then run your search by clicking on the Search button. Note: This search is just to help you identify search terms, so you don't want to add additional search terms or limits to your search.

For more information on identifying search terms, please see our guides on keyword searching and search strategies to develop your literature review:

- Keyword Searching: Keyword Search Strategy

- Literature Review: Develop Your Literature Review: Search Strategies

Combine search terms

Once you have a list of relevant search terms, you can create effective searches by connecting your search terms with the Boolean operators AND , OR , and NOT .

AND is useful for combining the different aspects of your topic. Using AND will find articles that contain all of your search terms.

For example, a search using the following strategy would find articles that combine all three of the search terms:

School Leadership AND At Risk Students AND Academic Progress

OR is useful for connecting synonyms, because it tells the database to search for any of the terms.

For example, a search using the following strategy would find articles that may have any of these search terms; you are telling the database that you don't care which of these topics it finds:

School Leadership OR School Administrators OR Principals

NOT is useful for cutting out results that aren't relevant. For example, if you were only interested in academic progress in K-12, you could get rid of any articles on higher education by using NOT:

Academic Progress NOT Higher Education

To learn more about Boolean operators, please see our Keyword Searching guide with information on Boolean:

- Guide: Keyword Searching: Boolean

Identify relevant sources beyond the Library

No library can have everything you will need to complete your literature review. While we recommend starting your literature review research in the Walden Library, we also encourage you to explore what's available beyond the Library.

As we mentioned on the Scope of the Literature Review page, government agencies, professional organizations, and think tanks can be good sources for information and data. If you already know of relevant agencies or organizations, go ahead and explore their websites to see what information is available.

If you're not aware of relevant agencies or organizations in your field of study, you can use a Google search limited to specific types of websites to help locate helpful information:

- Go to Google .

- Use the following strategies to limit your search to specific types of websites: To search only government websites, enter the following in the search box: site:.gov To search only organization websites, enter the following in the search box: site:.org

- Run your search. That should give you a list of governmental websites that mention education statistics.

Keep in mind that much of what you find online will not be from peer-reviewed sources, and may not be reliable. You'll need to critically evaluate what you find for veracity and relevance. To learn more about evaluating websites, please see our Evaluating Resources guide:

- Evaluating Resources: Websites

- Previous Page: Get & Stay Organized

- Next Page: Gather Resources

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Jump to navigation

IJHN Learning System

Bookmark/search this post.

You are here

Searching the literature | a step-by-step guide.

- Accreditation

- Register/Take course

Searching the Literature doesn't have to be difficult.

Created by librarians and information specialists at the Johns Hopkins Welch Medical Library, this self-paced online series includes ten modules designed to help strengthen your literature search skills. Our experts will share simple steps, effective strategies, and time-saving tips, guiding you every step of the way.

The modules provide everything you need to start your search for evidence and even some guidance on what to do with it once you’ve found it.

Topics include:

- Free and licensed databases

- Developing search strategies

- Citation managers

- Documenting your search

Target Audience

Perfect for anyone wanting to sharpen their literature-searching skills.

*Discounted pricing is available for groups and institutions, contact us for details.

You may also be interested in

Johns hopkins evidence-based practice series | 2022 edition.

The model and tools featured in this course are based on the 4th edition of the JHEBP Model and Guidelines Book released in 2021.

- 2.00 Attendance

Created in partnership between the Welch Medical Library and the Entrepreneurial Library Program

Copyright © 2019 Johns Hopkins University

- Accreditation Statement: The Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s Commission on Accreditation.

- Statement of Contact Hours: This 2.0 contact hour educational activity is provided by The Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing. The 2.0 contact hours will be awarded after the completion of all modules and the submission of the final course evaluation.

- Conflict of Interest: It is the policy of The Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing to require our continuing nursing education program faculty and planning committee members to disclose any financial relationships with companies providing program funding or manufacturers of any commercial products discussed in the program. The planning committee and program faculty report that they do not have financial relationships with manufacturers of any commercial products they discuss in the program.

- Commercial Support: This educational activity has not received any form of commercial support.

- Non-Endorsement of Products: The Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing and the American Nurses Credentialing Center does not endorse the use of any commercial products discussed or displayed in conjunction with this educational activity.

Available Credit

By registering for this course you agree to these terms: All intellectual property and copyright in this Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice program and its accompanying materials and derivatives are held solely by IJHN. These materials may not be modified, redistributed, or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without PRIOR authorization from IJHN.

- Submission Guidelines

safety learning system header

Learning Objectives

(1) Explain steps in conducting a literature search

(2) Identify resources to utilize in a literature search

(3) Perform an online literature search using U of U Health resources

Valentina is a third year pediatric resident who notices that many of the teenagers she sees in clinic use their phones to play games and connect with friends and family members. She wonders if there could be an app for teenagers to manage their chronic diseases, specifically type 1 diabetes. But where does she begin?

What is a literature search?

iterature search is a comprehensive exploration of published literature with the purpose of finding scholarly articles on a specific topic . Managing and organizing selected scholarly works can also be useful.

Why do a literature search?

Literature search is a critical component for any evidence-based project. It helps you to understand the complexity of a clinical issue, gives you insight into the scope of a problem, and provides you with best treatment approaches and the best available evidence on the topic. Without this step, your evidence-based practice project cannot move forward.

Five steps for literature search success

There are several steps involved in conducting a literature search. You may discover more along the way, but these steps will provide a good foundation.

Plan using PICO(T) to develop your clinical question and formulate a search strategy.

Identify a database to search.

Conduct your search in one or more databases.

Select relevant articles .

Organize your results . Remember that searching the literature is a process.

#1: Plan using PICO(T)

The PICO(T) question framework is a formula for developing answerable, researchable questions. Using PICO(T) guides you in your search for evidence and may even help you be more efficient in the process ( Click here to learn all about PICO(T) ).

Once you have your PICO(T) question you can formulate a search strategy by identifying key words, synonyms and subject headings. These can help you determine which databases to use.

#2: Identify a database

For your search, you will need to consult a variety of resources to find information on your topic. While some of these resources will overlap, each also contains unique information that you won’t find in other databases.

The "Big 3" databases: Embase, PubMed, and Scopus are always important to search because they contain large numbers of citations and have a fairly broad scope. ( Click here to access these databases and others in the library's A to Z database.)

In addition to searching these expansive databases, try one that is more topic specific.

We are here to help.

If you are conducting a literature search and are not certain of the details, don't panic! U of U Health has a wealth of resources, including experienced librarians, to help you through the process. Learn more here.

Utah’s Epic-embedded librarian support

Did you know you can request evidence-based information from the library directly through Epic? Contact us through Epic’s Message Basket.

Eccles Health Sciences medical librarians are able to provide expertise in articulating the clinical question, identifying appropriate data sources, and locating the best evidence in the shortest amount of time. You can also send a message to ASK EHSL .

#3: Conduct your search

Now that you have identified pertinent databases, it is time to begin the search!

Use the key words that you’ve identified from your PICO(T) question to start searching. You might start your search broadly, with just a few key words, and then add more once you see the scope of the literature. If the initial search doesn't produce many results, you can play with removing some key words and adding more granular detail.

In our intro case study, Valentina’s population is teenagers with type 1 diabetes and her intervention is a mobile app. Watch the video below to see how Valentina uses the powerful Embase PICO search feature to identify synonyms for type 1 diabetes, mobile apps, and teenagers.

Example of Embase using PICO Why use Embase? This search casts a wider net than most databases for more results.

Common Search Terms and Symbols

AND Includes both keywords Narrows search OR Either keyword/concept Combine synonyms and similar concepts Expands search "Double quotes" Specific phrase Wildcard* Any word ending variants (singular, plural, etc.) Example: nurs* = nurse, nurses, nursing, etc.

Controlled Vocabulary

Want to help make your search more accurate? Try using the controlled vocabulary, or main words or phrases that describe the main themes in an article, within databases. Controlled vocabulary is a standardized hierarchical system. For example, PubMed uses Medical Subject Headings or MeSH terms to “map” keywords to the controlled vocabulary. Not all databases use a controlled vocabulary, but many do. Embase’s controlled vocabulary is called Emtree, and CINAHL’s controlled vocabulary is called CINAHL Headings. Consider focusing the controlled vocabulary as the major topic when using MeSH, Emtree, or CINAHL Headings.

For Valentina’s question, there are MeSH terms for Adolescent, Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1, and Mobile Applications.

Example of PubMed using MeSH MeSH helps focus your PubMed search

Talk with your librarians for more help with searching with controlled vocabularies.

Every database uses filters to help you narrow your search. There are different filters in each database, but they tend to work in similar ways. Use filters to help you refine your search, rather than adding those keywords to the search. Filters include article/publication type, age, language, publication years, and species.

Using filters can help return the most accurate results for your search.

Article/publication types, such as randomized controlled trial, systematic reviews, can be used as filters.

Use an Age Filter, rather than adding “pediatric” or “geriatric” to your search.

Valentina uses the age filter for her question rather than as a keyword in the video below.

Example of a PubMed keyword search using filters PubMed is the most common search because it is the most widely available.

#4: Select relevant articles

Once you have completed your search, you’ll select articles that are relevant to your question. Some databases also include a “similar articles” feature which recommends other articles similar to the article you’re reviewing—this can also be a helpful tool.

When you’ve identified an article that appears relevant to your topic, use the “Snowballing” technique to find additional articles. Snowballing involves reviewing the reference lists of articles from your search.

In other words, look at your key articles and review their reference list for additional key or seminal articles to aid in your search.

#5: Organize your results

As you begin to collect articles during your literature search, it is important to store them in an organized fashion. Most research databases include personalized accounts for storing selected references and search strategies.

Reference managers are a great way to not only keep articles organized, but they also generate in-text citations and bibliographies when writing manuscripts, and provide a platform for sharing references with others working on your project.

A number of reference managers—such as Zotero , EndNote , RefWorks, Mendeley , and Papers are available. EndNote Basic (web-based) is freely available to U of U faculty, staff and students. If you need help with this process, contact a librarian to help you select the reference manager that will best suit your needs.

Using these steps, you’re ready to start your literature search. It is important to remember that there is not a right or wrong way to do the search. Literature searches are an iterative process—it will take some time and negotiation to find what you are looking for. You can always change your approach, or the information resource you are using. The important thing is to just keep trying. And before you get frustrated or give up, contact a librarian . They are here to help!

This article originally appeared May 12, 2020. It was updated to reflect current practice on March 14, 2021.

Tallie Casucci

Barbara wilson.

You have a good idea about what you want to study, compare, understand or change. But where do you go from there? First, you need to be clear about exactly what it is you want to find out. In other words, what question are you attempting to answer? Librarian Tallie Casucci and nursing leaders Gigi Austria and Barb Wilson help us understand how to formulate searchable, answerable questions using the PICO(T) framework.

EBP, or evidence-based practice, is a term we encounter frequently in today’s health care environment. But what does it really mean for the health care provider? College of Nursing interim dean Barbara Wilson and Nurse manager Gigi Austria explain how to integrate EBP into all aspects of patient care.

Frequent and deliberate practice is critical to attaining procedural competency. Cheryl Yang, pediatric emergency medicine fellow, shares a framework for providing trainees with opportunities to learn, practice, and maintain procedural skills, while ensuring high standards for patient safety.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Receive the latest insights in health care equity, improvement, leadership, resilience, and more..

Contact the Accelerate Team

50 North Medical Drive | Salt Lake City, Utah 84132 | 801-587-2157

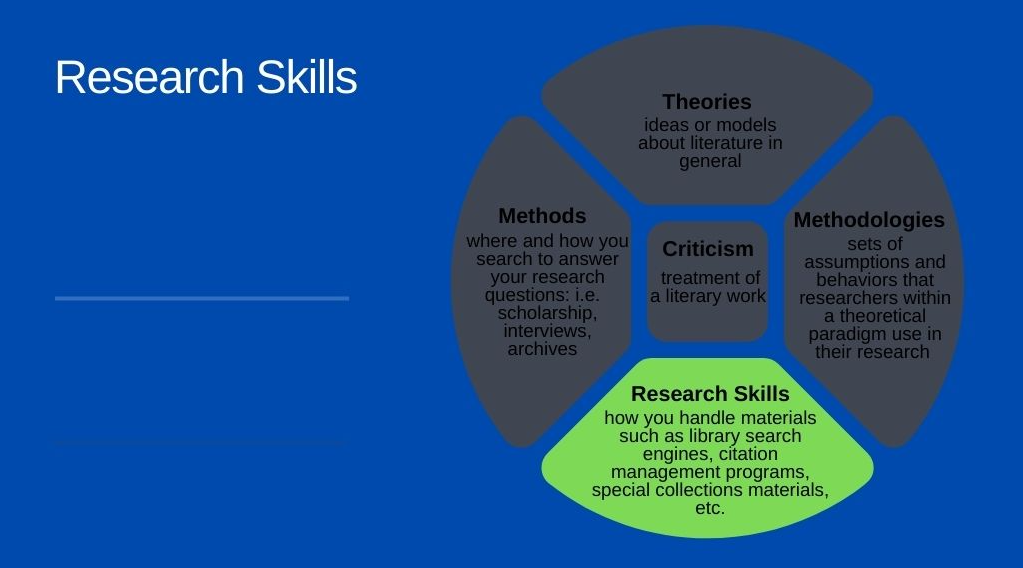

Research Skills

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

We discuss the following topic on this page:

We also provide the following activity:

Research Skills [Refresher]

Research skills are all about gathering evidence. This evidence , composed of facts and the reasoning that connects them, aims to convince your audience to accept your conclusions about the literary work. The most important piece of evidence you need to discuss is the literary work itself, which is a “fact” that you and your audience can examine together. Research means finding additional facts about the literary work and tying them together with reasoning to reach a significant and convincing conclusion.

Literature often presents us with factual difficulties. Sometimes authors revised their works and multiple versions exist. William Blake printed his own works and often changed illustrations and words between each printing. If we are reading a translated work, there may be more than one translation. In other words, we first need to identify which literary “object” we are studying. Electronic databases, such as the William Blake Archive , provide scholars with multiple versions of literary works, as well as plenty of reference sources. They are great places to begin a study!

The kind of evidence we need is directly related to the kind of claim we are making. If we want to claim that a literary work has seen a resurgence of public interest, we will look for historical evidence and quantitative evidence (statistics) to show that sales of the work (or database searches, or library checkouts, etc.) have increased. We may also seek qualitative evidence (such as interviews with booksellers and readers) to report on their impressions. We may look to see if there has been an increase in the number and kinds of adaptations. One example of such a work is Denis Perry’s and Carl Sederholm’s edited volume, Adapting Poe: Re-imaginings in Popular Culture (Spring 2012). If we are claiming that a literary work has a special relationship to a geographic region, we will look for textual evidence, geographic evidence, and historical evidence. See for example, Tom Conley’s The Self-Made Map (University of Minnesota Press 1996), which argues that geographic regions of France played a key role in Miguel de Montaigne’s Essais.

Types of Evidence [1]

Your choice of problem, theory, methodology, and method impact the kinds of evidence you will be seeking. Wendy Belcher identifies the following types:

- Qualitative Evidence: D ata on human behavior collected through direct observation, interviews, documents, and basic ethnography (191). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (2005) is a helpful guide. This area also encompasses audience research. Examples include the journal Reception: Texts, Readers, Audiences, History, the edited volume The Reader in the Text: Essays on Audience and Interpretation (Suleiman, Crosman, eds. 1980), and Media and Print Cultural Consumption in Nineteenth-Century Britain ( Rooney and Gasperini, eds. 2016).

- Quantitative Evidence: Data collected from standardized instruments and statistics, common to education, medicine, sociology, political sciences, psychology, and economics (191). Guides include Best Practices in Quantitative Methods (Osbourne 2007) and Statistics for People Who (Think that They) Hate Statistics (Salkind 2007).

- Historical Evidence: D ata collected from examinations of historical records to uncover the relationship of people to each other and to periods and events, common to all disciplines and collected from archives of primary materials (191). Guides include Historical Evidence and Argument (Henige 2006) and Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace, 2nd Edition (Mills 2009).

- Geographic Evidence: D ata about people’s relationship to places and environments in fields such as archaeology (191). Guides include Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, 5th Edition (Hay and Cope 2021) and Creative Methods for Human Geographers (Benzon, Holton, Wilkinson, eds. 2021).

- Textual Evidence: Data collected from texts about form (genre, plot, etc.), language (diction, rhetoric), purpose (message, function), meaning (symbolism, themes, etc.) and milieu (sources, culture, identity, etc.) (191). Guides include Introduction to Literary Hermeneutics (Szondi 1995) and The Hermeneutic Spiral and Interpretation in Literature and the Visual Arts (O’Toole 2018).

- Artistic Evidence: D ata from images, live performances, etc., used to study physical properties of a work (size, material, form, etc.), purpose (message, function, etc.) meaning (symbolism, etc.), and milieu (sources, culture, etc.) (191). Guides include Interpreting Objects and Collections (Pearce 1994) and Material Culture Studies in America (Schlereth, ed. 1982).

In the following chapters, five through nine, we present instruction for numerous research skills including how to gather research from literary works and from scholarly literature, and other skills such as how to use library search engines, citation management, google scholar, and source evaluation. The main thing to keep in mind for now is that you are gathering quality evidence and putting it together to construct a convincing and compelling argument about a literary work (or works).

For more advice on how to Reason with Evidence, consider the following from WritingCommons.org: [2]

Once you’ve spent sufficient time researching a topic —once you’re familiar with the ongoing scholarly conversation about a topic—then you’re ready to begin thinking about how to reason with the evidence you’ve gathered.

- engage in rhetorical analysis of the outside source(s)

- evaluate the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, purpose of the outside source(s)

- use evidence (e.g., quoting , paraphrasing , summarizing ) to bolster claims

- introduce sources and clarifying their authority

- use an appropriate citation style

For more advice on how to Connect Evidence to your Claims, consider the following from WritingCommons.org: [3]

We can’t, as writers, just stop at a quote, because our readers won’t necessarily know the connection between the point of your project and the quote. As such, we must make the connection for our reader. Here are a few ways to make such a connection:

- Break down ideas

- Connect back to the thesis

- Connect back to the paragraph’s main point

- Point to the author’s purpose

- In the “Back Matter” of this book, you will find a page titled “Rubrics.” On that page, we provide a rubric for Using Evidence for a Research Project. ↵

- Writing Commons. “Logos - Logos Definition.” Writing Commons , 11 Mar. 2022, https://writingcommons.org/article/logos/ . ↵

- Janechek, Jennifer, and Eir-Anne Edgar. “Connecting Evidence to Your Claims.” Writing Commons , 15 May 2021, https://writingcommons.org/section/citation/how-to-cite-sources-in-academic-and-professional-writing/citation-how-to-cnnect-evidence-to-your-claims/ . ↵

Research Skills Copyright © 2021 by Barry Mauer and John Venecek is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Open access

- Published: 14 August 2018

Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies

- Chris Cooper ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0864-5607 1 ,

- Andrew Booth 2 ,

- Jo Varley-Campbell 1 ,

- Nicky Britten 3 &

- Ruth Garside 4

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 18 , Article number: 85 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

203k Accesses

205 Citations

118 Altmetric

Metrics details

Systematic literature searching is recognised as a critical component of the systematic review process. It involves a systematic search for studies and aims for a transparent report of study identification, leaving readers clear about what was done to identify studies, and how the findings of the review are situated in the relevant evidence.

Information specialists and review teams appear to work from a shared and tacit model of the literature search process. How this tacit model has developed and evolved is unclear, and it has not been explicitly examined before.

The purpose of this review is to determine if a shared model of the literature searching process can be detected across systematic review guidance documents and, if so, how this process is reported in the guidance and supported by published studies.

A literature review.

Two types of literature were reviewed: guidance and published studies. Nine guidance documents were identified, including: The Cochrane and Campbell Handbooks. Published studies were identified through ‘pearl growing’, citation chasing, a search of PubMed using the systematic review methods filter, and the authors’ topic knowledge.

The relevant sections within each guidance document were then read and re-read, with the aim of determining key methodological stages. Methodological stages were identified and defined. This data was reviewed to identify agreements and areas of unique guidance between guidance documents. Consensus across multiple guidance documents was used to inform selection of ‘key stages’ in the process of literature searching.

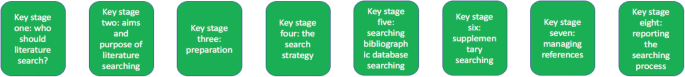

Eight key stages were determined relating specifically to literature searching in systematic reviews. They were: who should literature search, aims and purpose of literature searching, preparation, the search strategy, searching databases, supplementary searching, managing references and reporting the search process.

Conclusions

Eight key stages to the process of literature searching in systematic reviews were identified. These key stages are consistently reported in the nine guidance documents, suggesting consensus on the key stages of literature searching, and therefore the process of literature searching as a whole, in systematic reviews. Further research to determine the suitability of using the same process of literature searching for all types of systematic review is indicated.

Peer Review reports

Systematic literature searching is recognised as a critical component of the systematic review process. It involves a systematic search for studies and aims for a transparent report of study identification, leaving review stakeholders clear about what was done to identify studies, and how the findings of the review are situated in the relevant evidence.

Information specialists and review teams appear to work from a shared and tacit model of the literature search process. How this tacit model has developed and evolved is unclear, and it has not been explicitly examined before. This is in contrast to the information science literature, which has developed information processing models as an explicit basis for dialogue and empirical testing. Without an explicit model, research in the process of systematic literature searching will remain immature and potentially uneven, and the development of shared information models will be assumed but never articulated.

One way of developing such a conceptual model is by formally examining the implicit “programme theory” as embodied in key methodological texts. The aim of this review is therefore to determine if a shared model of the literature searching process in systematic reviews can be detected across guidance documents and, if so, how this process is reported and supported.

Identifying guidance

Key texts (henceforth referred to as “guidance”) were identified based upon their accessibility to, and prominence within, United Kingdom systematic reviewing practice. The United Kingdom occupies a prominent position in the science of health information retrieval, as quantified by such objective measures as the authorship of papers, the number of Cochrane groups based in the UK, membership and leadership of groups such as the Cochrane Information Retrieval Methods Group, the HTA-I Information Specialists’ Group and historic association with such centres as the UK Cochrane Centre, the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Coupled with the linguistic dominance of English within medical and health science and the science of systematic reviews more generally, this offers a justification for a purposive sample that favours UK, European and Australian guidance documents.

Nine guidance documents were identified. These documents provide guidance for different types of reviews, namely: reviews of interventions, reviews of health technologies, reviews of qualitative research studies, reviews of social science topics, and reviews to inform guidance.

Whilst these guidance documents occasionally offer additional guidance on other types of systematic reviews, we have focused on the core and stated aims of these documents as they relate to literature searching. Table 1 sets out: the guidance document, the version audited, their core stated focus, and a bibliographical pointer to the main guidance relating to literature searching.

Once a list of key guidance documents was determined, it was checked by six senior information professionals based in the UK for relevance to current literature searching in systematic reviews.

Identifying supporting studies

In addition to identifying guidance, the authors sought to populate an evidence base of supporting studies (henceforth referred to as “studies”) that contribute to existing search practice. Studies were first identified by the authors from their knowledge on this topic area and, subsequently, through systematic citation chasing key studies (‘pearls’ [ 1 ]) located within each key stage of the search process. These studies are identified in Additional file 1 : Appendix Table 1. Citation chasing was conducted by analysing the bibliography of references for each study (backwards citation chasing) and through Google Scholar (forward citation chasing). A search of PubMed using the systematic review methods filter was undertaken in August 2017 (see Additional file 1 ). The search terms used were: (literature search*[Title/Abstract]) AND sysrev_methods[sb] and 586 results were returned. These results were sifted for relevance to the key stages in Fig. 1 by CC.

The key stages of literature search guidance as identified from nine key texts

Extracting the data

To reveal the implicit process of literature searching within each guidance document, the relevant sections (chapters) on literature searching were read and re-read, with the aim of determining key methodological stages. We defined a key methodological stage as a distinct step in the overall process for which specific guidance is reported, and action is taken, that collectively would result in a completed literature search.

The chapter or section sub-heading for each methodological stage was extracted into a table using the exact language as reported in each guidance document. The lead author (CC) then read and re-read these data, and the paragraphs of the document to which the headings referred, summarising section details. This table was then reviewed, using comparison and contrast to identify agreements and areas of unique guidance. Consensus across multiple guidelines was used to inform selection of ‘key stages’ in the process of literature searching.

Having determined the key stages to literature searching, we then read and re-read the sections relating to literature searching again, extracting specific detail relating to the methodological process of literature searching within each key stage. Again, the guidance was then read and re-read, first on a document-by-document-basis and, secondly, across all the documents above, to identify both commonalities and areas of unique guidance.

Results and discussion

Our findings.

We were able to identify consensus across the guidance on literature searching for systematic reviews suggesting a shared implicit model within the information retrieval community. Whilst the structure of the guidance varies between documents, the same key stages are reported, even where the core focus of each document is different. We were able to identify specific areas of unique guidance, where a document reported guidance not summarised in other documents, together with areas of consensus across guidance.

Unique guidance

Only one document provided guidance on the topic of when to stop searching [ 2 ]. This guidance from 2005 anticipates a topic of increasing importance with the current interest in time-limited (i.e. “rapid”) reviews. Quality assurance (or peer review) of literature searches was only covered in two guidance documents [ 3 , 4 ]. This topic has emerged as increasingly important as indicated by the development of the PRESS instrument [ 5 ]. Text mining was discussed in four guidance documents [ 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] where the automation of some manual review work may offer efficiencies in literature searching [ 8 ].

Agreement between guidance: Defining the key stages of literature searching

Where there was agreement on the process, we determined that this constituted a key stage in the process of literature searching to inform systematic reviews.

From the guidance, we determined eight key stages that relate specifically to literature searching in systematic reviews. These are summarised at Fig. 1 . The data extraction table to inform Fig. 1 is reported in Table 2 . Table 2 reports the areas of common agreement and it demonstrates that the language used to describe key stages and processes varies significantly between guidance documents.

For each key stage, we set out the specific guidance, followed by discussion on how this guidance is situated within the wider literature.

Key stage one: Deciding who should undertake the literature search

The guidance.

Eight documents provided guidance on who should undertake literature searching in systematic reviews [ 2 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The guidance affirms that people with relevant expertise of literature searching should ‘ideally’ be included within the review team [ 6 ]. Information specialists (or information scientists), librarians or trial search co-ordinators (TSCs) are indicated as appropriate researchers in six guidance documents [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ].

How the guidance corresponds to the published studies

The guidance is consistent with studies that call for the involvement of information specialists and librarians in systematic reviews [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ] and which demonstrate how their training as ‘expert searchers’ and ‘analysers and organisers of data’ can be put to good use [ 13 ] in a variety of roles [ 12 , 16 , 20 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. These arguments make sense in the context of the aims and purposes of literature searching in systematic reviews, explored below. The need for ‘thorough’ and ‘replicable’ literature searches was fundamental to the guidance and recurs in key stage two. Studies have found poor reporting, and a lack of replicable literature searches, to be a weakness in systematic reviews [ 17 , 18 , 27 , 28 ] and they argue that involvement of information specialists/ librarians would be associated with better reporting and better quality literature searching. Indeed, Meert et al. [ 29 ] demonstrated that involving a librarian as a co-author to a systematic review correlated with a higher score in the literature searching component of a systematic review [ 29 ]. As ‘new styles’ of rapid and scoping reviews emerge, where decisions on how to search are more iterative and creative, a clear role is made here too [ 30 ].

Knowing where to search for studies was noted as important in the guidance, with no agreement as to the appropriate number of databases to be searched [ 2 , 6 ]. Database (and resource selection more broadly) is acknowledged as a relevant key skill of information specialists and librarians [ 12 , 15 , 16 , 31 ].

Whilst arguments for including information specialists and librarians in the process of systematic review might be considered self-evident, Koffel and Rethlefsen [ 31 ] have questioned if the necessary involvement is actually happening [ 31 ].

Key stage two: Determining the aim and purpose of a literature search

The aim: Five of the nine guidance documents use adjectives such as ‘thorough’, ‘comprehensive’, ‘transparent’ and ‘reproducible’ to define the aim of literature searching [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ]. Analogous phrases were present in a further three guidance documents, namely: ‘to identify the best available evidence’ [ 4 ] or ‘the aim of the literature search is not to retrieve everything. It is to retrieve everything of relevance’ [ 2 ] or ‘A systematic literature search aims to identify all publications relevant to the particular research question’ [ 3 ]. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual was the only guidance document where a clear statement on the aim of literature searching could not be identified. The purpose of literature searching was defined in three guidance documents, namely to minimise bias in the resultant review [ 6 , 8 , 10 ]. Accordingly, eight of nine documents clearly asserted that thorough and comprehensive literature searches are required as a potential mechanism for minimising bias.

The need for thorough and comprehensive literature searches appears as uniform within the eight guidance documents that describe approaches to literature searching in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Reviews of effectiveness (of intervention or cost), accuracy and prognosis, require thorough and comprehensive literature searches to transparently produce a reliable estimate of intervention effect. The belief that all relevant studies have been ‘comprehensively’ identified, and that this process has been ‘transparently’ reported, increases confidence in the estimate of effect and the conclusions that can be drawn [ 32 ]. The supporting literature exploring the need for comprehensive literature searches focuses almost exclusively on reviews of intervention effectiveness and meta-analysis. Different ‘styles’ of review may have different standards however; the alternative, offered by purposive sampling, has been suggested in the specific context of qualitative evidence syntheses [ 33 ].

What is a comprehensive literature search?

Whilst the guidance calls for thorough and comprehensive literature searches, it lacks clarity on what constitutes a thorough and comprehensive literature search, beyond the implication that all of the literature search methods in Table 2 should be used to identify studies. Egger et al. [ 34 ], in an empirical study evaluating the importance of comprehensive literature searches for trials in systematic reviews, defined a comprehensive search for trials as:

a search not restricted to English language;

where Cochrane CENTRAL or at least two other electronic databases had been searched (such as MEDLINE or EMBASE); and

at least one of the following search methods has been used to identify unpublished trials: searches for (I) conference abstracts, (ii) theses, (iii) trials registers; and (iv) contacts with experts in the field [ 34 ].

Tricco et al. (2008) used a similar threshold of bibliographic database searching AND a supplementary search method in a review when examining the risk of bias in systematic reviews. Their criteria were: one database (limited using the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (HSSS)) and handsearching [ 35 ].

Together with the guidance, this would suggest that comprehensive literature searching requires the use of BOTH bibliographic database searching AND supplementary search methods.

Comprehensiveness in literature searching, in the sense of how much searching should be undertaken, remains unclear. Egger et al. recommend that ‘investigators should consider the type of literature search and degree of comprehension that is appropriate for the review in question, taking into account budget and time constraints’ [ 34 ]. This view tallies with the Cochrane Handbook, which stipulates clearly, that study identification should be undertaken ‘within resource limits’ [ 9 ]. This would suggest that the limitations to comprehension are recognised but it raises questions on how this is decided and reported [ 36 ].

What is the point of comprehensive literature searching?

The purpose of thorough and comprehensive literature searches is to avoid missing key studies and to minimize bias [ 6 , 8 , 10 , 34 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] since a systematic review based only on published (or easily accessible) studies may have an exaggerated effect size [ 35 ]. Felson (1992) sets out potential biases that could affect the estimate of effect in a meta-analysis [ 40 ] and Tricco et al. summarize the evidence concerning bias and confounding in systematic reviews [ 35 ]. Egger et al. point to non-publication of studies, publication bias, language bias and MEDLINE bias, as key biases [ 34 , 35 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 ]. Comprehensive searches are not the sole factor to mitigate these biases but their contribution is thought to be significant [ 2 , 32 , 34 ]. Fehrmann (2011) suggests that ‘the search process being described in detail’ and that, where standard comprehensive search techniques have been applied, increases confidence in the search results [ 32 ].

Does comprehensive literature searching work?