Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Sam Altman thinks AI will change the world. All of it.

Categorical thinking can lead to investing errors

How storytelling helps data-driven teams succeed

Credit: Stephen Sauer

Ideas Made to Matter

Climate Change

The 5 greatest challenges to fighting climate change

Kara Baskin

Dec 27, 2019

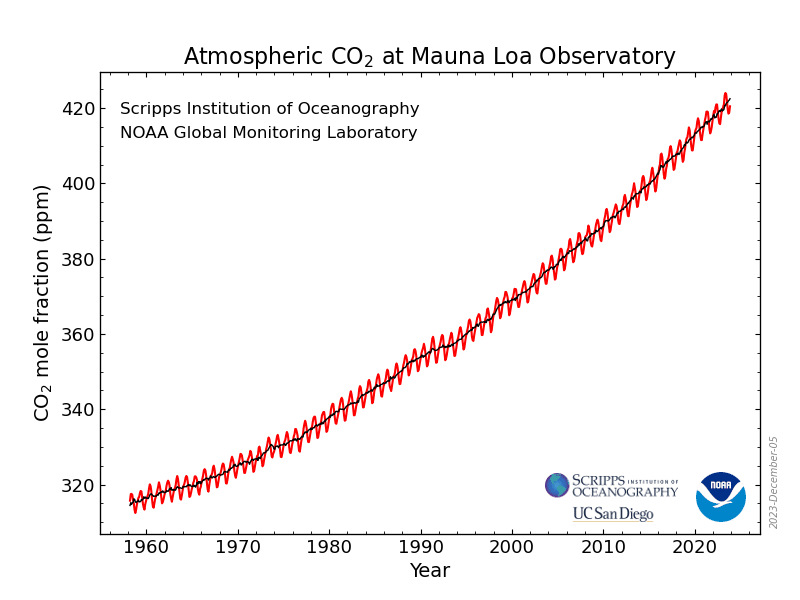

Climate change: Most of the world agrees it’s a danger, but how do we conquer it? What’s holding us back? Christopher Knittel, professor of applied economics at the MIT Sloan School of Management, laid out five of the biggest challenges in a recent interview.

CO2 is a global pollutant that can’t be locally contained

“The first key feature of climate change that puts it at odds with past environmental issues is that it’s a global pollutant, rather than a local pollutant. [Whether] I release a ton of CO2 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, or in London, it does the same damage to the globe,” Knittel said. “Contrast that with local pollutants, where if I release a ton of sulfur dioxide or nitrogen oxide in Cambridge, the majority of the damage stays near Cambridge.”

Thus, CO2 is far harder to manage and regulate.

For now, climate change is still hypothetical

The damage caused by most climate change pollutants will happen in the future. Which means most of us won’t truly be affected by climate change — it’s a hypothetical scenario conveyed in charts and graphs. While we’d like politicians and voters to be moved by altruism, this isn’t always the case. In general, policymakers have little incentive to act.

“People [who stand to be] most harmed by climate change aren’t even born yet. Going back to the policymaker’s perspective, she has much less of an incentive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions because those reductions are going to benefit voters in the future and not her current voters,” Knittel said.

There’s no direct link to a smoking gun

Despite the global threat from climate-altering pollutants, it’s hard for scientists to link them to a specific environmental disaster, Knittel said. Without a definitive culprit, it’s easier for skeptics to ignore or explain away climate change effects.

Developing countries contribute to a large share of pollution

Simply put, this isn’t their top priority.

“We’re asking very poor countries that are worried about where their next meal is coming from, or whether they can send their kids to school, to incur costs to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to benefit the world. And that’s a tough ask for a policymaker inside of a developing country,” he said.

Modern living is part of the problem

It’s a tough pill to swallow, but modern conveniences like electricity, transportation, and air conditioning contribute to climate change, and remedies potentially involve significant sacrifice and lifestyle change.

“Although we’ve seen great strides in reductions in solar costs and batteries for electric vehicles, these are still expensive alternatives. There is no free lunch when it comes to overcoming climate change,” Knittel warned.

Writing in the Los Angeles Times recently, Knittel said, “If an evil genius had set out to design the perfect environmental crisis … those five factors would have made climate change a brilliant choice. But we didn’t need an evil genius. We stumbled into it on our own.”

Read next — Climate experts: Clean tech is here, now we need people power

Related Articles

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The five biggest threats to our natural world … and how we can stop them

From destructive land use to invasive species, scientists have identified the main drivers of biodiversity loss – so that countries can collectively act to tackle them

- Read more on the Cop15 talks to negotiate new UN targets to protect biodiversity in the coming decade

- 1 Changes in land and sea use

- 2 Direct exploitation of natural resources

- 3 The climate crisis

- 4 Pollution

- 5 Invasive species

T he world’s wildlife populations have plummeted by more than two-thirds since 1970 – and there are no signs that this downward trend is slowing. The first phase of Cop15 talks in Kunming this week will lay the groundwork for governments to draw up a global agreement next year to halt the loss of nature. If they are to succeed, they will need to tackle what the IPBES (Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services) has identified as the five key drivers of biodiversity loss: changes in land and sea use; direct exploitation of natural resources; climate change; pollution; and invasion of alien species.

Changes in land and sea use

Clearing the US prairies: ‘On a par with tropical deforestation’

“It’s hidden destruction. We’re still losing grasslands in the US at a rate of half a million acres a year or more.”

Tyler Lark, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, knows what he is talking about. Lark and a team of researchers used satellite data to map the expansion and abandonment of land across the US and discovered that 4m hectares (10m acres) had been destroyed between 2008 and 2016.

Large swathes of the United States’ great prairies continue to be converted into cropland, according to the research, to make way for soya bean, corn and wheat farming.

Changes in land and sea use has been identified as the main driver of “unprecedented” biodiversity and ecosystem change over the past 50 years. Three-quarters of the land-based environment and about 66% of the marine environment have been significantly altered by human actions.

North America’s grasslands – often referred to as prairies – are a case in point. In the US, about half have been converted since European settlement , and the most fertile land is already being used for agriculture. Areas converted more recently are sub-prime agricultural land, with 70% of yields lower than the national average, which means a lot of biodiversity is being lost for diminishing returns.

“Our findings demonstrate a pervasive pattern of encroachment into areas that are increasingly marginal for production but highly significant for wildlife,” Lark and his team wrote in the paper , published in Nature Communications.

Boggier areas of land, or those with uneven terrain, were traditionally left as grassland, but in the past few decades, this marginal land has also been converted. In the US, 88% of cropland expansion takes place on grassland, and much of this is happening in the Great Plains – known as America’s breadbasket – which used to be the most extensive grassland in the world.

What are the five biggest threats to biodiversity?

According to the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity there are five main threats to biodiversity. In descending order these are: changes in land and sea use; direct exploitation of natural resources; climate change; pollution and invasive species.

1. For terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, land-use change has had the largest relative negative impact on nature since 1970. More than a third of the world’s land surface and nearly 75% of freshwater resources are now devoted to crop or livestock production. Alongside a doubling of urban area since 1992, things such as wetlands, scrubland and woodlands – which wildlife relies on – are ironed out from the landscape.

2. The direct exploitation of organisms and non-living materials, including logging, hunting and fishing and the extraction of soils and water are all negatively affecting ecosystems . In marine environments, overfishing is considered to be the most serious driver of biodiversity loss. One quarter of the world’s commercial fisheries are overexploited, according to a 2005 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment .

3. The climate crisis is dismantling ecosystems at every level. Extreme weather events such as tropical storms and flooding are destroying habitats. Warmer temperatures are also changing the timing of natural events – such as the availability of insects and when birds hatch their eggs in spring. The distribution of species and their range is also changing.

4. Many types of pollution are increasing. In marine environments, pollution from agricultural runoff (mainly nitrogen and phosphorus) do huge damage to ecosystems. Agricultural runoff causes toxic algal blooms and even "dead zones" in the worst affected areas. Marine plastic pollution has increased tenfold since 1980, affecting at least 267 species.

5. Since the 17th century, invasive species have contributed to 40% of all known animal extinctions. Nearly one fifth of the Earth’s surface is at risk of plant and animal invasions. Invasive species change the composition of ecosystems by outcompeting native species.

Hotspots for this expansion have included wildlife-rich grasslands in the “prairie pothole” region which stretches between Iowa, Dakota, Montana and southern Canada and is home to more than 50% of North American migratory waterfowl, as well as 96 species of songbird. This cropland expansion has wiped out about 138,000 nesting habitats for waterfowl, researchers estimate.

These grasslands are also a rich habitat for the monarch butterfly – a flagship species for pollinator conservation and a key indicator of overall insect biodiversity. More than 200m milkweed plants, the caterpillar’s only food source, were probably destroyed by cropland expansion, making it one of the leading causes for the monarch’s national decline .

The extent of conversion of grassland in the US makes it a larger emission source than the destruction of the Brazilian Cerrado , according to research from 2019 . About 90% of emissions from grassland conversion comes from carbon lost in the soil, which is released when the grassland is ploughed up.

“The rate of clearing that we’re seeing on these grasslands is on par with things like tropical deforestation, but it often receives far less attention,” says Lark.

Food crop production globally has increased by about 300% since 1970 , despite the negative environmental impacts.

Reducing food waste and eating less meat would help cut the amount of land needed for farming, while researchers say improved management of existing croplands and utilising what is already farmed as best as possible would reduce further expansion.

Lark concludes: “I think there’s a huge opportunity to re-envision our landscapes so that they’re not only providing incredible food production but also mitigating climate change and helping reduce the impacts of the biodiversity crisis by increasing habitats on agricultural land.” PW

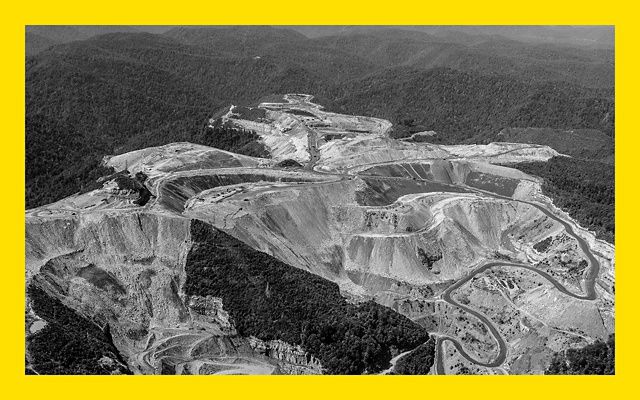

Direct exploitation of natural resources

Groundwater extraction: ‘People don’t see it’

From hunting, fishing and logging to the extraction of oil, gas, coal and water, humanity’s insatiable appetite for the planet’s resources has devastated large parts of the natural world.

While the impacts of many of these actions can often be seen, unsustainable groundwater extraction could be driving a hidden crisis below our feet, experts have warned, wiping out freshwater biodiversity, threatening global food security and causing rivers to run dry.

Farmers and mining companies are pumping vast underground water stores at an unsustainable rate, according to ecologists and hydrologists. About half the world’s population relies on groundwater for drinking water and it helps sustain 40% of irrigation systems for crops .

The consequences for freshwater ecosystems – among the most degraded on the planet – are under-researched as studies have focused on the depletion of groundwater for agriculture.

But a growing body of research indicates that pumping the world’s most extracted resource – water – is causing significant damage to the planet’s ecosystems. A 2017 study of the Ogallala aquifer – an enormous water source underneath eight states in the US Great Plains – found that more than half a century of pumping has caused streams to run dry and a collapse in large fish populations. In 2019, another study estimated that by 2050 between 42% and 79% of watersheds that pump groundwater globally could pass ecological tipping points, without better management.

“The difficulty with groundwater is that people don’t see it and they don’t understand the fragility of it,” says James Dalton, director of the global water programme at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). “Groundwater can be the largest – and sometimes the sole – source in certain types of terrestrial habitats.

“Uganda is luxuriantly green, even during the dry season, but that’s because a lot of it is irrigated with shallow groundwater for agriculture and the ecosystems are reliant on tapping into it.”

According to UPGro (Unlocking the Potential of Groundwater for the Poor), a research programme looking into the management of groundwater in sub-Saharan Africa, 73 of the 98 operational water supply systems in Uganda are dependent on water from below ground. The country shares two transboundary aquifers: the Nile and Lake Victoria basins. At least 592 aquifers are shared across borders around the world.

“Some of the groundwater reserves are huge, so there is time to fix this,” says Dalton. “It’s just there’s no attention to it.”

Inge de Graaf, a hydrologist at Wageningen University, who led the 2019 study into watershed levels, found between 15% to 21% had already passed ecological tipping points, adding that once the effects had become clear for rivers, it was often too late.

“Groundwater is slow because it has to flow through rocks. If you extract water today, it will impact the stream flow maybe in the next five years, in the next 10 years, or in the next decades,” she says. “I think the results of this research and related studies are pretty scary.”

In April, the largest ever assessment of global groundwater wells by researchers from University of California, Santa Barbara, found that up to one in five were at risk of running dry. Scott Jasechko, a hydrologist and lead author on the paper, says that the study focuses on the consequences for humans and more research is needed on biodiversity.

“Millions of wells around the world could run dry with even modest declines in groundwater levels. And that, of course, has cascading implications for livelihoods and access to reliable and convenient water for individuals and ecosystems,” he says. PG

The climate crisis

Climate and biodiversity: ‘Solve both or solve neither’

In 2019, the European heatwave brought 43C heat to Montpellier in France. Great tit chicks in 30 nest boxes starved to death, probably because it was too hot for their parents to catch the food they needed, according to one researcher . Two years later, and 2021’s heatwave appears to have set a European record, pushing temperatures to 48.8C in Sicily in August. Meanwhile, wildfires and heatwaves are stripping the planet of life.

Until now, the destruction of habitats and extraction of resources has had a more significant impact on biodiversity than the climate crisis. This is likely to change over the coming decades as the climate crisis dismantles ecosystems in unpredictable and dramatic ways, according to a review paper published by the Royal Society.

“There are many aspects of ecosystem science where we will not know enough in sufficient time,” the paper says. “Ecosystems are changing so rapidly in response to global change drivers that our research and modelling frameworks are overtaken by empirical, system-altering changes.”

The calls for biodiversity and the climate crisis to be tackled in tandem are growing. “It is clear that we cannot solve [the global biodiversity and climate crises] in isolation – we either solve both or we solve neither,” says Sveinung Rotevatn, Norway’s climate and environment minister, with the launch in June of a report produced by the world’s leading biodiversity and climate experts. Zoological Society of London senior research fellow Dr Nathalie Pettorelli, who led a s tudy on the subject published in the Journal of Applied Ecology in September, says: “The level of interconnectedness between the climate change and biodiversity crises is high and should not be underestimated. This is not just about climate change impacting biodiversity; it is also about the loss of biodiversity deepening the climate crisis.”

Writer Zadie Smith describes every country’s changes as a “local sadness” . Insects no longer fly into the house when the lights are on in the evening, the snowdrops are coming out earlier and some migratory species, such as swallows, are starting to try to stay in the UK for winter. All these individual elements are entwined in a much bigger story of decline.

Our biosphere – the thin film of life on the surface of our planet – is being destabilised by temperature change. On land, rains are altering, extreme weather events are more common, and ecosystems more flammable. Associated changes, including flooding , sea level rise, droughts and storms, are having hugely damaging impacts on biodiversity and its ability to support us.

In the ocean, heatwaves and acidification are stressing organisms and ecosystems already under pressure due to other human activities, such as overfishing and habitat fragmentation.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) landmark report showed that extreme heatwaves that would usually happen every 50 years are already happening every decade. If warming is kept to 1.5C these will happen approximately every five years.

The distributions of almost half (47%) of land-based flightless mammals and almost a quarter of threatened birds, may already have been negatively affected by the climate crisis, the IPBES warns . Five per cent of species are at risk of extinction from 2C warming, climbing to 16% with a 4.3C rise.

Connected, diverse and extensive ecosystems can help stabilise the climate and will have a better chance of thriving in a world permanently altered by rising emissions, say experts. And, as the Royal Society paper says: “Rather than being framed as a victim of climate change, biodiversity can be seen as a key ally in dealing with climate change.” PW

The hidden threat of nitrogen: ‘Slowly eating away at biodiversity’

On the west coast of Scotland, fragments of an ancient rainforest that once stretched along the Atlantic coast of Britain cling on. Its rare mosses, lichens and fungi are perfectly suited to the mild temperatures and steady supply of rainfall, covering the crags, gorges and bark of native woodland. But nitrogen pollution, an invisible menace, threatens the survival of the remaining 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) of Scottish rainforest, along with invasive rhododendron, conifer plantations and deer.

While marine plastic pollution in particular has increased tenfold since 1980 – affecting 44% of seabirds – air, water and soil pollution are all on the rise in some areas. This has led to pollution being singled out as the fourth biggest driver of biodiversity loss.

In Scotland, nitrogen compounds from intensive farming and fossil fuel combustion are dumped on the Scottish rainforest from the sky, killing off the lichen and bryophytes that absorb water from the air and are highly sensitive to atmospheric conditions.

“The temperate rainforest is far from the sources of pollution, yet because it’s so rainy, we’re getting a kind of acid rain effect,” says Jenny Hawley, policy manager at Plantlife, which has called nitrogen pollution in the air “the elephant in the room” of nature conservation. “The nitrogen-rich rain that’s coming down and depositing nitrogen into those habitats is making it impossible for the lichen, fungi, mosses and wildflowers to survive.”

Environmental destruction caused by nitrogen pollution is not limited to the Scottish rainforest. Algal blooms around the world are often caused by runoff from farming, resulting in vast dead zones in oceans and lakes that kill scores of fish and devastate ecosystems. Nitrogen-rich rainwater degrades the ability of peatlands to sequester carbon, the protection of which is a stated climate goal of several governments. Wildflowers adapted to low-nitrogen soils are squeezed out by aggressive nettles and cow parsley, making them less diverse.

About 80% of nitrogen used by humans – through food production, transport, energy and industrial and wastewater processes – is wasted and enters the environment as pollution.

“Nitrogen pollution might not result in huge floods and apocalyptic droughts but we are slowly eating away at biodiversity as we put more and more nitrogen in ecosystems,” says Carly Stevens, a plant ecologist at Lancaster University. “Across the UK, we have shown that habitats that have lots of nitrogen have fewer species in them. We have shown it across Europe. We have shown it across the US. Now we’re showing it in China. We’re creating more and more damage all the time.”

To decrease the amount of nitrogen pollution causing biodiversity loss, governments will commit to halving nutrient runoff by 2030 as part of an agreement for nature currently being negotiated in Kunming. Halting the waste of vast amounts of nitrogen fertiliser in agriculture is a key part of meeting the target, says Kevin Hicks, a senior research fellow at the Stockholm Environment Institute centre at York.

“One of the biggest problems is the flow of nitrogen from farming into watercourses,” Hicks says. “In terms of a nitrogen footprint, the most intensive thing that you can eat is meat. The more meat you eat, the more nitrogen you’re putting into the environment.”

Mark Sutton, a professor at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, says reducing nitrogen pollution also makes economic sense.

“Nitrogen in the atmosphere is 78% of every breath we take. It does nothing, it’s very stable and makes the sky blue. Then there are all these other nitrogen compounds: ammonia, nitrates, nitrous oxide. They create air and water pollution,” he says. He argues that if you price every kilo of nitrogen at $1 (an estimated fertiliser price), and multiply it by the amount of nitrogen pollution lost in the world – 200bn tonnes – it amounts to $200bn (£147bn) every year.

“The goal to cut nitrogen waste in half would save you $100bn,” he says. “I think $100bn a year is a worthwhile saving.” PG

- Invasive species

The problem for islands: ‘We have to be very careful’

On Gough Island in the southern Atlantic Ocean, scores of seabird chicks are eaten by mice every year. The rodents were accidentally introduced by sailors in the 19th century and their population has surged, putting the Tristan albatross – one of the largest of its species – at risk of extinction along with dozens of rare seabirds. Although Tristan albatross chicks are 300 times the size of mice, two-thirds did not fledge in 2020 largely because of the injuries they sustained from the rodents, according to the RSPB .

The situation on the remote island, 2,600km from South Africa, is a grisly warning of the consequences of the human-driven impacts of invasive species on biodiversity. An RSPB-led operation to eradicate mice from the British overseas territory has been completed, using poison to help save the critically endangered albatross and other bird species from injuries they sustain from the rodents. It will be two years before researchers can confirm whether or not the plan has worked. But some conservationists want to explore another controversial option whose application is most advanced in the eradication of malaria : gene drives.

Instead of large-scale trapping or poisoning operations, which have limited effectiveness and can harm other species, gene drives involve introducing genetic code into an invasive population that would make them infertile or all one gender over successive generations. The method has so far been used only in a laboratory setting but at September’s IUCN congress in Marseille, members backed a motion to develop a policy on researching its application and other uses of synthetic biology for conservation.

“If a gene drive were proven to be effective and there were safety mechanisms to limit its deployment, you would introduce multiple individuals on an island whose genes would be inherited by other individuals in the population,” says David Will, an innovation programme manager with Island Conservation , a non-profit dedicated to preventing extinctions by removing invasive species from islands. “Eventually, you would have either an entirely all male or entirely all female population and they would no longer be able to reproduce.”

Nearly one-fifth of the Earth’s surface is at risk of plant and animal invasions and although the problem is worldwide, such as feral pigs wreaking havoc in the southern United States and lionfish in the Mediterranean , islands are often worst affected. The global scale of the issue will be revealed in a UN scientific assessment in 2023.

“We have to be very careful,” says Austin Burt, a professor of evolutionary genetics at Imperial College London, who researches how gene drives can be used to eradicate malaria in mosquito populations. “If you’re going after mice, for example, and you’re targeting mice on an island, you’d need to make sure that none of those modified mice got off the island to cause harm to the mainland population.”

In July, scientists announced they had successfully wiped out a population of malaria-transmitting mosquitoes using a gene drive in a laboratory setting, raising the prospect of self-destructing mosquitoes being released into the wild in the next decade.

Kent Redford, chair of the IUCN Task Force on Synthetic Biology who led an assessment of the use of synthetic biology in conservation, said there are clear risks and opportunities in the field but further research is necessary.

“None of these genetic tools are ever going to be a panacea. Ever. Nor do I think they will ever replace the existing tools,” Redford says, adding: “There is a hope – and I stress hope – that engineered gene drives have the potential to effectively decrease the population sizes of alien invasive species with very limited knock-on effects on other species.” PG

Find more age of extinction coverage here , and follow biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield on Twitter for all the latest news and features

- Biodiversity

- The road to Cop15

- Endangered species

- Endangered habitats

- Climate crisis

- Conservation

Most viewed

Yale Environment Review (YER) is a student-run review that provides weekly updates on environmental research findings.

How and why environmental issues are neglected.

Understanding how and why people fail to recognize the importance of future environmental problems can be used to tailor responses to environmental information problems

By Liz Thomas • July 21, 2013

Original Paper: Jari Lyytimäkia, Petri Tapiob, Timo Assmutha. "Unawareness in environmental protection: The case of light pollution from traffic". Land Use Policy 29:3. (2012) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.10.002

In the future, the world will face many new environmental problems, yet the scientific and policy research community will not necessarily recognize these problems as they come up. Which agendas environmental scientists and policymakers advance depends on many factors, including media attention and socioeconomic and historical dynamics. The identity and the values of the agenda-setters influence which issues are emphasized and which are neglected—purposely or unintentionally. Prioritizing environmental information is made even more difficult since the state of the environment is constantly changing and new scientific findings are constantly coming to light. The issues that do gain recognition may often be informed by outdated or incorrect data, even when more up to date environmental information may exist.

False awareness: a person believes that all the information is accessible and that he has it, even when the information that he has may be insufficient, outdated, or misunderstood. In the case of lighting, a person may think he knows all there is to know about lighting because it is a common aspect of his life—not something that he would question. Many people have not experienced true darkness and perceive artificial lighting to be the norm. The team speculates that because artificial lights have become ubiquitous, scientists have not researched their negative impacts at the same rate as their benefits, even though research on their negative impacts indicate potentially serious problems. One possible solution to this problem is disproving people's inclinations to think of lighting as harmless with numerical estimates, such as the International Energy Agency's estimate that global carbon dioxide emissions from lighting are two-thirds that of motor vehicles.

Deliberate unawareness: People do not find an environmental topic to be important, and thus do not seek out more information on the problem. Even when the problem starts to become a topic of interest, people purposefully set aside the facts. As light pollution starts to become a topic of interest, people may find that changes to address light pollution are too radical and stressful to address. Scientists and practitioners can potentially address this kind of unawareness by framing their arguments in ethical and emotional terms.

Concealed awareness: An actor purposefully omits information and is unable or unwilling to share it with others. This kind of awareness may be motivated by financial issues or a benevolent attempt to secure the public good. Actors may be unable to share information because of a lack of resources or opportunities. For scientists studying lighting, the light-positive paradigm may inhibit scientists from sharing their concerns about light pollution. A critical, open-minded campaign can encourage people to share factual information.

You might like these articles that share the same topics

The policies and measures aiming at reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) have proliferated, resulting in varying interpretations of "safeguards". Now that REDD+ is maturing, direct trade-offs between monetized emissions reductions and social and biodiversity values call for more explicit regulations in this approach to climate change mitigation.

Local leaders must prepare for sea-level rise and coastal disaster management. Besides property damage, issues of social justice will arise because minorities, the poor, and the most vulnerable people are at greater risk than others.

Scientists explore how entrepreneurs and decision makers can make or break how a national park benefits a community

Many conservationists and land planners look to property tax policy to encourage private landowners to keep their land undeveloped. While property tax can hold back the conversion of rural land to some extent, its impact is limited.

- Show search

Speak Up For Nature: Your Guide to Environmental Issues in 2022

Follow this guide on conservation issues and act for your planet.

October 04, 2020

How to Use This Guide

The past couple of years have been a difficult and humbling reminder that no matter where you live, your life is connected to the health of the natural world. When we degrade our planet, we make it more difficult for nature to provide the food, water and air we all rely on.

It doesn’t have to be this way. There are better, smarter paths rooted in science and in nature’s resilience. The more we speak up about these paths to our leaders, the more positive change we can make.

The first step is to start building your understanding of top environmental and conservation issues. No, you don’t need to be able to recite the Clean Water Act by heart.

Dig into the topics in this guide until you’re comfortable with them. Then, take one (or more) of these actions...

5 Things You Can Do

- Talk About These Issues

Let your friends and family know what's important to you and why...maybe they'll join you in speaking up next time! Here's how to talk about climate change.

- Contact Your Local Leaders

Local, state and federal, ask your elected leaders to support the things you care about. They are there to represent you, and they can't do it if you don't talk to them. Learn who's representing you in your state.

- Contact Congress

Weigh in on critical, timely issues. You can call the Capitol switchboard at (202) 224-3121, or send messages on a range of issues through our Action Center.

- Take Our Pledge

Your voice can make a difference. Every single action you take in your community can have a real impact on how we meet the needs of our Earth and everyone on it. Add your voice.

Share Your Thoughts

Use this guide to inform your social network and encourage them to speak up with us. There's power in numbers! You can start by sharing this message!

Climate Change

The science is clear: the more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the warmer it gets. The warmer it gets, the higher our seas, the more intense our storms, the less ice in our Arctic and the more stresses on wildlife. Worse, we're running out of time.

The good news? We know what we need to do and how to do it.

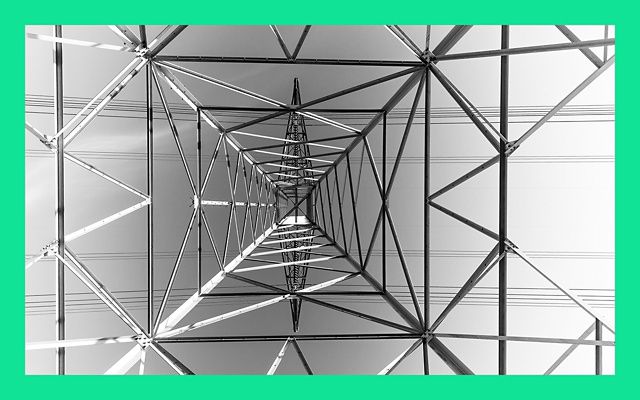

It comes down to switching to cleaner energy like solar, protecting and restoring natural places that can store more carbon, updating our electric grid (which is older than the TV) , and inventing the next great technology.

We put people on the moon. We made supercomputers that fit in your pocket. We are fully capable of doing all of these things, and doing them in time.

5 Ways to Speak Up

- Share this Guide on Twitter

We can do these things if we make it known that we believe in the promise of clean energy, not only to lessen the impacts of climate change but to support jobs and economic growth.

Take action and speak up for climate solutions today. Start with these 5 actions.

Want to Dig Deeper?

Smart climate policy : Reinventing how we generate, transport and use energy resources.

Choosing Clean Energy : New technologies, better choices and lower costs.

Natural Climate Solutions : Conservation, restoration and management of natural lands to reduce emissions.

Grid modernization : Improve reliability and efficiency of our power and reduce costs.

Climate Change FAQs : The best information at hand about climate change's challenges and solutions, from scientists at The Nature Conservancy.

Protecting Our Nation's Land & Water

Back in 1977, conservation and recreation made up 2.5% of the federal government's total budget. Today, it's less than 1%. This doesn't make any sense given that our need for healthy land, clean water and open spaces has dramatically increased as our population has grown.

We’ve had some policy wins (thank you, Great American Outdoors Act) , but our usage demands of lands far outpace the resources coming into them. National and state parks alone host around 1 billion visits each year.

That's hikers, hunters and anglers, but also people going to weddings, reunions and summer camp. Throw in city parks with the baseball games and soccer tournaments and visitor numbers go through the roof.

Outside of being awe-inspiring, public lands clean our water and our air, and they protect us from coastal storms and heavy rains. They also have a massive positive impact on our economy . Outdoor recreation (often on public lands) generates $887 billion in annual consumer spending, directly supporting 7.6 million jobs.

It’s time to better care for the lands that care for us…but how?

There are plenty of ways to put money back into our lands and waters, if we make the right choices today. There's infrastructure investments that include wetlands and trees, not just levees and seawalls . There's tax reforms that incentivize private investment in restoring wetlands and forests or donating land for conservation. But, we need to let our elected officials know this is where we want our money to go.

Take action and speak up for our protecting our lands and waters today. Start with these 5 actions.

Want to dig deeper?

Land and Water Conservation Fund : Standing up for America’s premier conservation program.

Tropical Forest Conservation Act : Protecting tropical forests and biodiversity.

Water management systems : Ensuring sustainable water supplies during drought.

Modernizing fishing data : Using technology to build sustainable fisheries.

Investments in nature : Supporting strong conservation funding and policies.

International conservation funding : Protecting natural resources abroad through U.S. programs.

Tax incentives : Reforming tax policy to incentivize investments in conservation.

Reduce Risks to Communities from Natural Disasters

Stay up to date.

Sign up for our monthly Nature News newsletter:

For the past several years, we've seen more frequent, more intense natural disasters ravage communities across the globe. How many “once-in-a-lifetime” disasters must we encounter…in our lifetimes? And what can we do about it?

Because climate change has made these disasters more intense, we have to prevent the worst warming from happening. And, we have to better protect our communities. To do both of those things, we can turn to nature as a part of the solution. Yes, nature!

Healthy forests filter water and can reduce the risk of megafires. Sand dunes, marshes and reefs naturally protect our coasts from the storm surge that arrives with a hurricane. You might be thinking, I see forests and sand dunes all the time, don't we have enough?

One key word with forests is "healthy." We’ve suppressed natural fires in some forests, making them unhealthy tinderboxes. And while we may have some sandy coastlines, we’ve bulldozed our natural sand dunes and oyster reefs that were our first line of defense for our coasts.

Nature can bounce back if we give it the chance. Just like we must invest in bridges and roads, we must invest in restoring forests and sand dunes. Nature IS infrastructure. Nature IS investment. Nature IS a solution.

And the best part is while nature reduces risk for us, it also cleans our water and air, gives wildlife a home and gives us great parks to visit. We need to ensure consideration of nature and nature-based solutions in community infrastructure projects.

Take action and speak up for our natural infrastructure today. To get started, follow our 5 Ways to Speak Up.

Transportation bill : Advancing nature-based solutions to infrastructure challenges

Natural infrastructure : Protecting communities from storms

Disaster relief funding : Increasing resilience when rebuilding after disasters

National Flood Insurance Program : Planning for floods to reduce risk

Water Resources Development Act : Managing waterways to benefit people and nature

Safeguarding Core Environmental Laws

Before Congress passed environmental laws in the 1960s and 1970s, our air was more polluted than ever and rivers had so many pollutants that they actually caught fire.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle decided that our health and the health of our natural places were basic values. They worked together to create laws like the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Endangered Species Act and others.

Air and water in this country dramatically improved. Species came back from the brink. And generations of Americans have benefited.

Our country’s successful, bipartisan environmental laws are increasingly under attack. Many proposed changes to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and Clean Water Act have no basis in science and would erode the laws’ fundamental protections.

Take action and speak up for core environmental protections today. To get started, follow our 5 Ways to Speak Up.

Foundational environmental laws : Protecting critical conservation policies that keep our water clean and our lands healthy.

Greater sage grouse : Actions to save an iconic Western bird would also reduce threats for people

Sign Our Pledge : Contact your elected officials and speak up for nature.

Advancing Clean Energy

Humanity has been burning fossil fuels (coal, petroleum and natural gas) at an accelerated rate for around 140 years. Scientists have known for many decades that these forms of energy emit greenhouse gases that are unnaturally warming the planet. In 2018, fossil fuels were responsible for 93% of human-caused carbon emissions in the U.S.

Transitioning to clean energies like wind and solar would make an enormous difference in helping the planet avoid the worst effects of climate change, such as extreme droughts, stronger storms and crippling coastal flooding. And yet, renewables make up less than 10% of the nation's energy mix.

Over the last decade, the cost of solar has dropped 92% and wind turbines by nearly 50%. In most parts of the U.S., new renewable energy costs less than coal. The time is right to make the switch.

To quicken and ease this transition, we need to make our power system more reliable by modernizing our century-old electric grid and advancing energy storage. And we need to put those turbines and panels in smart places. We don't need to knock down more forest and prairie; there's enough land already developed to meet our clean energy needs 17 times over.

The benefits of a clean energy shift go way beyond stopping climate change. The shift gives us cleaner air, more consumer choices and more jobs.

Take action and speak up for clean energy today. Start with these 5 actions.

Smart Climate Change Policy : Creating a low-carbon future that benefits everyone.

Modernizing Our Electrical Grid

Our electric grid is the physical network that sends power to our homes and businesses by connecting them in real time to energy plants scattered around the country. This network, much of which is over 75 years old, wasn't built for the technologies our climate-threatened future depends on, like scattered wind turbines and rooftop solar panels.

It's also not efficient or reliable enough for our needs. It doesn’t take a natural disaster to shut the power off. Currently, something as small as a squirrel can cause an outage that ripples into a larger blackout.

Technological advances like the internet allow utilities and consumers to relay real time info about energy supply, demand and cost. This is a trove of useful information but its value is held back by infrastructure older than the television. We can build a modernized electrical grid that turns that information into smarter, more efficient choices that let cleaner energy sources shine.

Small changes to how and when we use energy can save us money and make a huge dent in the carbon emissions that cause climate change.

The U.S. Department of Energy estimates they need an additional $100 billion to fully modernize the grid. That's a lot of money, but those upgrades would save consumers $2 trillion over the next 20 years.

With the current grid causing economic losses of roughly $150 billion a year, there’s never been a better time to start. Let’s bring cutting-edge technology to the grid so it pollutes less, lowers costs for customers and creates jobs.

Take action and speak up for smarter energy today. To get started, follow our 5 Ways to Speak Up.

We no longer need to choose between abundant energy and a cleaner environment. A renewable energy revolution is happening across the United States. Learn what this means.

Your Voice is Critical

If you have a voice, you have a choice. And together, our voices are powerful. Speak up for nature, and for us all.

The Ocean Has Issues: 7 Biggest Problems Facing Our Seas, and How to Fix Them

- California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo

Treehugger / Hilary Allison

- Conservation

- Overfishing

- Shark Finning

- Ocean Acidification

- Dying Coral Reefs

- Mercury Pollution

- Plastic Soup

The oceans are among the biggest resources for life on earth, but they're also our biggest dumping grounds. That kind of paradox could give anyone an identity crisis. We seem to think we can take all the goodies out, put all our garbage in, and the oceans will happily tick away indefinitely. However, while it's true the oceans can provide us with some amazing eco-solutions like alternative energy, our activities place undue stress on these vast bodies of water. Here are the seven biggest problems, plus some light at the end of the tunnel.

1. Overfishing Is Draining the Life From the Water

Overfishing is negatively impacting our oceans. It can cause the extinction of certain species while threatening the survivability of any predators that depend on those species as a source of food. By depleting food sources in such large quantities, we leave less for others, to the point where some marine animals actually starve. Reduction of fishing to ensure sustainable levels is necessary if at risk species are to recover at all.

There is much to be desired in the ways we fish. First, we humans use some pretty destructive methods in how we pull catches, including bottom trawling, which destroys sea floor habitat and scoops up many unwanted fish and animals that end up being tossed aside. We also pull far too many fish to be sustainable, pushing many species to the point of being listed as threatened and endangered.

Of course, we know why we overfish: There are a lot of people who like to eat fish, and a lot of it! Simply put, the more fish, the more money fishermen make. However, there are also less obvious reasons explaining why we overfish, including but not limited to our promotion of certain marine species over others for their purported health benefits.

In order keep the oceans' fisheries healthy, we not only have to know which species can be sustainably eaten, but also how best to catch them. It's our job as eaters to question restaurant servers, sushi chefs, and seafood purveyors about the sources of their fish, and read labels when we buy from store shelves.

2. The Oceans' Most Important Predators Being Killed...But Just for the Fins

Overfishing is an issue that extends beyond familiar species like bluefin tuna and orange roughy. It's also a serious issue with sharks. At least 100 million sharks are killed each year for their fins. It is a common practice to catch sharks, cut off their fins, and toss them back into the ocean where they are left to die. The fins are sold as an ingredient for soup. And the waste is extraordinary.

Sharks are top-of-the-food-chain predators, which means their reproduction rate is slow. Their numbers don't bounce back easily from overfishing. On top of that, their predator status also helps regulate the numbers of other species. When a major predator is taken out of the loop, it's usually the case that species lower on the food chain start to overpopulate their habitat, creating a destructive downward spiral of the ecosystem.

Shark finning is a practice that needs to end if our oceans are to maintain some semblance of balance. Luckily, a growing awareness around the unsustainability of the practice is helping to lower the popularity of shark fin soup.

3. Ocean Acidification Sending Us Back 17 Million Years

Ocean acidification is no small issue. The basic science behind acidification is that the ocean absorbs CO 2 through natural processes, but at the rate at which we're pumping it into the atmosphere through burning fossil fuels, the ocean's pH balance is dropping to the point where some life within the oceans are having trouble coping.

According to NOAA , it is estimated that by the end of this century, surface levels of the oceans could have a pH of about 7.8 (in 2020 the pH level is 8.1). "The last time the ocean pH was this low was during the middle Miocene, 14-17 million years ago. The Earth was several degrees warmer and a major extinction event was occurring."

Freaky, right? At some point in time, there is a tipping point where the oceans become too acidic to support life that can't quickly adjust. In other words, many species are going to be wiped out, from shellfish to corals and the fish that depend on them.

4. Dying Coral Reefs and A Scary Downward Spiral

Keeping the coral reefs healthy is another major buzz topic right now. A focus on how to protect the coral reefs is important considering coral reefs support a huge amount of small sea life, which in turn supports both larger sea life and people, not only for immediate food needs but also economically.

Rapid warming of the ocean surface is a primary cause of coral bleaching, during which corals lose the algae that keep them alive. Figuring out ways to protect this "life support system" is a must for the overall health of the oceans.

5. Ocean Dead Zones Are Everywhere, and Growing

Dead zones are swaths of ocean that don't support life due to hypoxia, or a lack of oxygen. Global warming is a prime suspect for what's behind the shifts in ocean behavior that cause dead zones. The number of dead zones is growing at an alarming rate, with over 500 known to exist, and the number is expected to grow.

Dead zone research underscores the interconnectedness of our planet. It appears that crop biodiversity on land could help prevent dead zones in the ocean by reducing or eliminating the use of fertilizers and pesticides that run off into the open ocean and are part of the cause of dead zones. Knowing what we dump into the oceans is important in being aware of our role in creating areas of lifelessness in an ecosystem upon which we depend.

6. Mercury Pollution Going from Coal to Oceans to Fish to Our Dinner Table

Pollution is running rampant in the oceans but one of the scariest pollutants is mercury because, well, it ends up on the dinner table. The worst part is mercury levels in the oceans are predicted to rise. So where does the mercury come from? You can probably guess. Mainly coal plants. In fact, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, coal and oil- fired power plants are the largest industrial source of mercury pollution in the country. And, mercury has already contaminated water bodies in all 50 states, let alone our oceans. The mercury is absorbed by organisms on the bottom of the food chain and as bigger fish eat bigger fish, it works its way back up the food chain right to us, most notably in the form of tuna.

You can calculate how much tuna you can safely eat , and while the though that calculating your fish intake to avoid poisoning is really depressing, at least we're aware of the dangers so that we can, hopefully, straighten up our act.

7. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch a Swirling Plastic Soup You Can See from Space

One more depressing one before we move on to something fun and exciting. We certainly can't ignore the giant patches of plastic soup the size of Texas sitting smack dab in the middle of the Pacific ocean.

Taking a look at the "Great Pacific Garbage Patch" (which is actually several areas of debris in the North Pacific) is a sobering way to realize there is no "away" when it comes to trash, especially trash that lacks the ability to decompose. The patch was discovered by Captain Charles Moore, who has been actively vocal about it ever since.

Luckily, the Great Pacific Garbage Patch has gotten a lot of attention from eco-organizations, including Project Kaisei , which launched the first clean-up effort and experimentation, and David de Rothschild who sailed a boat made of plastic out to the patch to bring awareness to it.

Geoengineering Our Oceans: What We Do and Don't Know About New Technologies

Now for that light at the end of the tunnel, though some may call it a very dim light, the issue of geoengineering. Ideas have been floated such as dumping limestone in the water to balance out the pH levels of the ocean and to counter the effects of all that CO2 we pump into the air. Back in 2012 we watched as iron filings were dumped into the ocean to see if that'd help spur a large algae bloom and suck up some CO 2 . It didn't. Or rather, it didn't do what we expected it to do.

This is a really controversial area, mainly because we don't know what we don't know. Though that doesn't stop many scientists from saying we have to give it a try.

Research has helped to lay out what some of the risks are in terms of consequences, and in terms of what's just a plain old dumb idea. There are quite a few ideas floating around that claim will save us from ourselves - from ocean iron fertilization to fertilizing trees with nitrogen, from biochar to carbon sinks. But while these ideas hold a seed of promise, they also each hold a sizable nugget of controversy that may or may not keep them from coming seeing the light of day.

Sticking To What We Do Know - Conservation

Of course, good old fashioned conservation efforts will also help us out. Though, looking at the big picture and the extent of the effort required, it might take a lot of gumption to stay optimistic. But optimistic we should be!

It's true that conservation efforts are lagging, but that doesn't mean they're non-existent. Records are even being set for how much marine area is being conserved. It's all just a head nod if we don't implement and enforce the regulations we create, and get even more creative with them. But when we look at what can happen for our oceans when conservation efforts are taken to the max, it's well worth the energy.

Sumaila, U. Rashid and Travis C. Tai. " End Overfishing and Increase the Resilience of the Ocean to Climate Change ." Frontiers in Marine Science , vol. 7, July 2020, doi:10.3389/fmars.2020.00523

Grémillet, David, et al. " Starving Seabirds: Unprofitable Foraging and Its Fitness Consequences in Cape Gannets Competing With Fisheries in the Benguela Upwelling Ecosystem ." Mar Biol, vol. 163, 2016, doi:10.1007/s00227-015-2798-2

Oberle, Ferdinand K.J., et al. " Deciphering the Lithological Consequences of Bottom Trawling to Sedimentary Habitats on the Shelf ." Journal of Marine Systems , vol. 159, 2016, pp. 120-131., doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2015.12.008

Van Houtan, Kyle S, et al. “ Coastal Sharks Supply the Global Shark Fin Trade .” Biology Letters, vol. 16, no. 10, 2020, p. 20200609., doi:10.1098/rsbl.2020.0609

Yokoi, Hiroki, et al. " Impact of Biology Knowledge on the Conservation and Management of Large Pelagic Sharks ." Scientific Reports , vol. 7, no. 1, 2017, doi:10.1038/s41598-017-09427-3

" Ocean Acidification ." National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration .

Sully, Shannon, et al. " A Global Analysis of Coral Bleaching Over the Past Two Decades ." Nature Communications , vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09238-2

Breitburg, Denise, et al. " Declining Oxygen in the Global Ocean and Coastal Waters ." Science , vol. 359, no. 6371, 2018, doi:10.1126/science.aam7240

" Nutrient Pollution: The Sources and Solutions: Agriculture ." Environmental Protection Agency .

" Mercury and Air Toxic Standards: Cleaner Power Plants ." United States Environmental Protection Agency .

Blum, Joel, et al. " Methylmercury production below the mixed layer in the North Pacific Ocean ." Nature Geoscience, vol. 6, 2013, pp. 879–884., doi:10.1038/ngeo1918

" What is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch ?" National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service .

de Rothschild, David. Plastiki: Across the Pacific on Plastic: An Adventure to Save Our Oceans . Chronicle Books. 2011.

Caldeira, Ken et al. " The Science of Geoengineering ." Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences , vol. 41, no. 1, 2013, pp. 231-256., doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105548

Burns, Wil, and Charles R. Corbett. " Antacids for the Sea? Artificial Ocean Alkalinization and Climate Change ." One Earth , vol. 3, no. 2, 2020, pp. 154-156., doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.07.016

Lin, Albert. " Geoengineering: Imperfect Yet Perhaps Important Options For Addressing Climate Change ." Handbook Of U.S. Environmental Policy , 2020, pp. 373-388., doi:10.4337/9781788972840.00036

Emerson, David. " Biogenic Iron Dust: A Novel Approach to Ocean Iron Fertilization as a Means of Large Scale Removal of Carbon Dioxide from the Atmosphere ." Frontiers In Marine Science , vol. 6, 2019, doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00022

- Marine Biome: Types, Plants, and Wildlife

- How Does Mercury Get in Fish?

- Understanding the Sustainable Seafood Industry

- What Is Squalene? Why Is It Controversial?

- 10 Stunning Plants and Sea Creatures on the Ocean Floor

- 11 Incredible Facts About Bull Sharks

- Are Orcas Endangered? Conservation Status and Threats

- Where Are Earth's Largest Nature Reserves?

- 7 Reasons Why We're Lucky to Have Sharks

- 11 Endangered Species That Are Still Hunted for Food

- What Is Ocean Acidification?

- Why the Humphead Wrasse Is Endangered

- Are Bluefin Tuna Endangered? Conservation Status and Outlook

- 'Seaspiracy' Film Reveals Destruction of Marine Life by Overfishing and Pollution

- What Are Ocean Dead Zones? Definition, Causes, and Impact

- Why Are Coral Reefs Dying? And What You Can Do to Help Save Them

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Roger Ware Brockett, 84

Providing community support

A change of mind, heart, and soul

Eyes on tomorrow, voices of today.

Candice Chen ’22 (left) and Noah Secondo ’22.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Harvard students share thoughts, fears, plans to meet environmental challenges

For many, thinking about the world’s environmental future brings concern, even outright alarm.

There have been, after all, decades of increasingly strident warnings by experts and growing, ever-more-obvious signs of the Earth’s shifting climate. Couple this with a perception that past actions to address the problem have been tantamount to baby steps made by a generation of leaders who are still arguing about what to do, and even whether there really is a problem.

It’s no surprise, then, that the next generation of global environmental leaders are preparing for their chance to begin work on the problem in government, business, public health, engineering, and other fields with a real sense of mission and urgency.

The Gazette spoke to students engaged in environmental action in a variety of ways on campus to get their views of the problem today and thoughts on how their activities and work may help us meet the challenge.

Eric Fell and Eliza Spear

Fell is president and Spear is vice president of Harvard Energy Journal Club. Fell is a graduate student at the Harvard John H. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences and Spear is a graduate student in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology.

FELL: For the past three centuries, fossil fuels have enabled massive growth of our civilization to where we are today. But it is now time for a new generation of cleaner-energy technologies to fuel the next chapter of humanity’s story. We’re not too late to solve this environmental challenge, but we definitely shouldn’t procrastinate as much as we have been. I don’t worry about if we’ll get it done, it’s the when. Our survival depends on it. At Harvard, I’ve been interested in the energy-storage problem and have been focusing on developing a grid-scale solution utilizing flow batteries based on organic molecules in the lab of Mike Aziz . We’ll need significant deployment of batteries to enable massive penetration of renewables into the electrical grid.

SPEAR: Processes leading to greenhouse-gas emissions are so deeply entrenched in our way of life that change continues to be incredibly slow. We need to be making dramatic structural changes, and we should all be very worried about that. In the Harvard Energy Journal Club, our focus is energy, so we strive to learn as much as we can about the diverse options for clean-energy generation in various sectors. A really important aspect of that is understanding how much of an impact those technologies, like solar, hydro, and wind, can really have on reducing greenhouse-gas emissions. It’s not always as much as you’d like to believe, and there are still a lot of technical and policy challenges to overcome.

I can’t imagine working on anything else, but the question of what I’ll be working on specifically is on my mind a lot. The photovoltaics field is at a really exciting point where a new technology is just starting to break out onto the market, so there are a lot of opportunities for optimization in terms of performance, safety, and environmental impact. That’s what I’m working on now [in Roy Gordon’s lab ] and I’m really enjoying it. I’ll definitely be in the renewable-energy technology realm. The specifics will depend on where I see the greatest opportunity to make an impact.

Photo (left) courtesy of Kritika Kharbanda; photo by Tiera Satchebell.

Kritika Kharbanda ’23 and Laier-Rayshon Smith ’21

Kharbanda is with the Harvard Student Climate Change Conference, Harvard Circular Economy Symposium. Smith is a member of Climate Leaders Program for Professional Students at Harvard. Both are students at Harvard Graduate School of Design.

KHARBANDA: I come from a country where the most pressing issues are, and will be for a long time, poverty, food shortage, and unemployment born out of corruption, illiteracy, and rapid gentrification. India was the seventh-most-affected country by climate change in 2019. With two-thirds of the population living in rural areas with no access to electricity, even the notion of climate change is unimaginable.

I strongly believe that the answer lies in the conjugality of research and industry. In my field, achieving circularity in the building material processes is the burning concern. The building industry currently contributes to 40 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions, of which 38 percent is contributed by the embedded or embodied energy used for the manufacturing of materials. A part of the Harvard i-lab, I am a co-founder of Cardinal LCA, an early stage life-cycle assessment tool that helps architects and designers visualize this embedded energy in building materials, saving up to 46 percent of the energy from the current workflow. This venture has a strong foundation as a research project for a seminar class I took at the GSD in fall 2020, instructed by Jonathan Grinham. I am currently working as a sustainability engineer at Henning Larsen architects in Copenhagen while on a leave of absence from GSD. In the decades to come, I aspire to continue working on the embodied carbon aspect of the building industry. Devising an avant garde strategy to record the embedded carbon is the key. In the end, whose carbon is it, anyway?

SMITH: The biggest challenges are areas where the threat of climate change intersects with environmental justice. It is important that we ensure that climate-change mitigation and adaptation strategies are equitable, whether it is sea-level rise or the increase in urban heat islands. We should seek to address the threats faced by the most vulnerable communities — the communities least able to resolve the threat themselves. These often tend to be low-income communities and communities of color that for decades have been burdened with bearing the brunt of environmental health hazards.

During my time at Harvard, I have come to understand how urban planning and design can seek to address this challenge. Planners and designers can develop strategies to prioritize communities that are facing a significant climate-change risk, but because of other structural injustices may not be able to access the resources to mitigate the risk. I also learned about climate gentrification: a phenomenon in which people in wealthier communities move to areas with lower risks of climate-change threats that are/were previously lower-income communities. I expect to work on many of these issues, as many are connected and are threats to communities across the country. From disinvestment and economic extraction to the struggle to find quality affordable housing, these injustices allow for significant disparities in life outcomes and dealing with risk.

Lucy Shaw ’21

Shaw is co-president of the HBS Energy and Environment Club. She is a joint-degree student at Harvard Business School and Harvard Kennedy School.

SHAW: I want to see a world where climate change is averted and the environment preserved, without it being at the expense of the development and prosperity of lower-income countries. We have, or are on the cusp of having, many of the financial and technological tools we need to reduce emissions and environmental damage from a wide array of industries, such as agriculture, energy, and transport. The challenge I am most worried about is how we balance economic growth and opportunity with reducing humanity’s environmental impact and share this burden equitably across countries.

I came to Harvard as a joint degree student at the Kennedy School and Business School to be able to see this challenge from two different angles. In my policy-oriented classes, we learned about the opportunities and challenges of global coordination among national governments — the difficulty in enforcing climate agreements, and in allocating and agreeing on who bears the responsibility and the costs of change, but also the huge potential that an international framework with nationally binding laws on environmental protection and carbon-emission reduction could have on changing the behavior of people and businesses. In my business-oriented classes, we learned about the power of business to create change, if there is a driven leadership. We also learned that people and businesses respond to incentives, and the importance of reducing cost of technologies or increasing the cost of not switching to more sustainable technologies — for example, through a tax. After graduate school, I plan to join a leading private equity investor in their growing infrastructure team, which will equip me with tools to understand what makes a good investment in infrastructure and what are the opportunities for reducing the environmental impact of infrastructure while enhancing its value. I hope to one day be involved in shaping environmental and development policy, whether it is on a national or international level.

Photo (left) by Tabitha Soren.

Quinn Lewis ’23 and Suhaas Bhat ’24

Both are with the Student Climate Change Conference, Harvard College.

LEWIS: When I was a kid, I imagined being an adult as a future with a stable house, a fun job, and happy kids. That future didn’t include wildfires that obscured the sun for months, global water shortages, or billionaires escaping to terrariums on Mars. The threats are so great and so assured by inaction that it’s very hard for me to justify doing anything else with my time and attention because very little will matter if there’s 1 billion climate refugees and significant portions of the continental United States become uninhabitable for human life.

For whatever reason, I still feel a great deal of hope around giving it a shot. I can’t imagine not working to mitigate the climate crisis. Media and journalism will play a huge role in raising awareness, as they generate public pressure that can sway those in power. Another route for change is to cut directly to those in power and try to convince them of the urgency of the situation. Given that I am 22 years old, it is much easier to raise public awareness or work in media and journalism than it is to sit down with some of the most powerful people on the planet, who tend to be rather busy. At school, I’m on a team that runs the University-wide Student Climate Change Conference at Harvard, which is a platform for speakers from diverse backgrounds to discuss the climate crisis and ways students and educators can take immediate and effective action. Also, I write about and research challenges and solutions to the climate crisis through the lenses of geopolitics and the global economy, both as a student at the College and as a case writer at the Harvard Business School. Outside of Harvard, I have worked in investigative journalism and at Crooked Media, as well as on political campaigns to indirectly and directly drive urgency around the climate crisis.

BHAT: The failure to act on climate change in the last few decades, despite mountains of scientific evidence, is a consequence of political and institutional cowardice. Fossil fuel companies have obfuscated, misinformed, and lobbied for decades, and governments have failed to act in the best interests of their citizens. Of course, the fight against climate change is complex and multidimensional, requiring scientific, technical, and entrepreneurial expertise, but it will ultimately require systemic change to allow these talents to shine.

At Harvard, my work on climate has been focused on running the Harvard Student Climate Conference, as well as organizing for Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard. My hope for the Climate Conference is to provide students access to speakers who have dedicated their careers to all aspects of the fight against climate change, so that students interested in working on climate have more direction and inspiration for what to do with their careers. We’ve featured Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley, members of the Sunrise Movement, and the CEO of Impossible Foods as some examples of inspiring and impactful people who are working against climate change today.

I organize for FFDH because I believe that serious institutional change is necessary for solving the climate crisis and also because of a sort of patriotism I have for Harvard. I deeply respect and care for this institution, and genuinely believe it is an incredible force for good in the world. At the same time, I believe Harvard has a moral duty to stand against the corporations whose misdeeds and falsification of science have enabled the climate crisis.

Libby Dimenstein ’22

Dimenstein is co-president of Harvard Law School Environmental Law Society.

DIMENSTEIN: Climate change is the one truly existential threat that my generation has had to face. What’s most scary is that we know it’s happening. We know how bad it will be; we know people are already dying from it; and we still have done so little relative to the magnitude of the problem. I also worry that people don’t see climate change as an “everyone problem,” and more as a problem for people who have the time and money to worry about it, when in reality it will harm people who are already disadvantaged the most.

I want to recognize Professor Wendy Jacobs, who recently passed away. Wendy founded HLS’s fantastic Environmental Law and Policy Clinic, and she also created an interdisciplinary class called the Climate Solutions Living Lab. In the lab, groups of students drawn from throughout the University would conduct real-world projects to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions. The class was hard, because actually reducing greenhouse gases is hard, but it taught us about the work that needs to be done. This summer I’m interning with the Environmental Defense Fund’s U.S. Clean Air Team, and I anticipate a lot of my work will revolve around the climate. After graduating, I’m hoping to do environmental litigation, either with a governmental division or a nonprofit, but I also have an interest in policy work: Impact litigation is fascinating and important, but what we need most is sweeping policy change.

Candice Chen ’22 and Noah Secondo ’22

Chen and Secondo are co-directors of the Harvard Environmental Action Committee. Both attend Harvard College.

SECONDO: The environment is fundamental to rural Americans’ identity, but they do not believe — as much as urban Americans — that the government can solve environmental problems. Without the whole country mobilized and enthusiastic, from New Hampshire to Nebraska, we will fail to confront the climate crisis. I have no doubt that we can solve this problem. To rebuild trust between the U.S. government and rural communities, federal departments and agencies need to speak with rural stakeholders, partner with state and local leaders, and foreground rural voices. Through the Harvard College Democrats and the Environmental Action Committee, I have contributed to local advocacy efforts and creative projects, including an environmental art publication.

I hope to work in government to keep the policy development and implementation processes receptive to rural perspectives, including in the environmental arena. At every level of government, if we work with each other in good faith, we will tackle the climate crisis and be better for it.

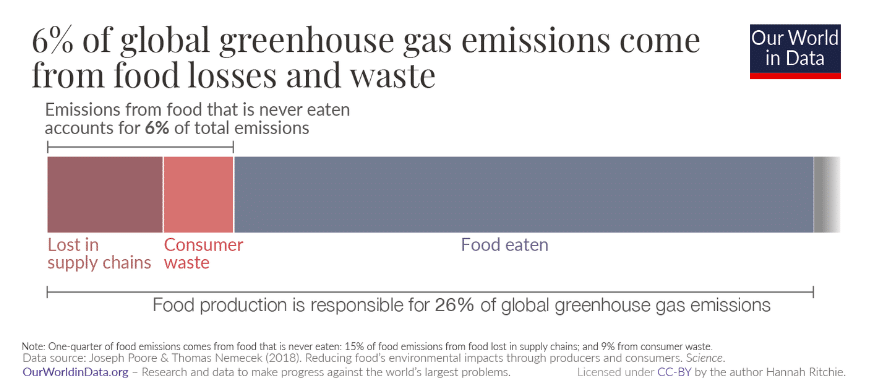

CHEN: I’m passionate about promoting more sustainable, plant-based diets. As individual consumers, we have very little control over the actions of the largest emitters, massive corporations, but we can all collectively make dietary decisions that can avoid a lot of environmental degradation. Our food system is currently very wasteful, and our overreliance on animal agriculture devastates natural ecosystems, produces lots of potent greenhouse gases, and creates many human health hazards from poor animal-waste disposal. I feel like the climate conversation is often focused around the clean energy transition, and while it is certainly the largest component of how we can avoid the worst effects of global warming, the dietary conversation is too often overlooked. A more sustainable future also requires us to rethink agriculture, and especially what types of agriculture our government subsidizes. In the coming years, I hope that more will consider the outsized environmental impact of animal agriculture and will consider making more plant-based food swaps.

To raise awareness of the environmental benefits of adopting a more plant-based diet, I’ve been involved with running a campaign through the Environmental Action Committee called Veguary. Veguary encourages participants to try going vegetarian or vegan for the month of February, and participants receive estimates for how much their carbon/water/land use footprints have changed based on their pledged dietary changes for the month.

Photo (left) courtesy of Cristina Su Liu.

Cristina Su Liu ’22 and James Healy ’21

More like this.

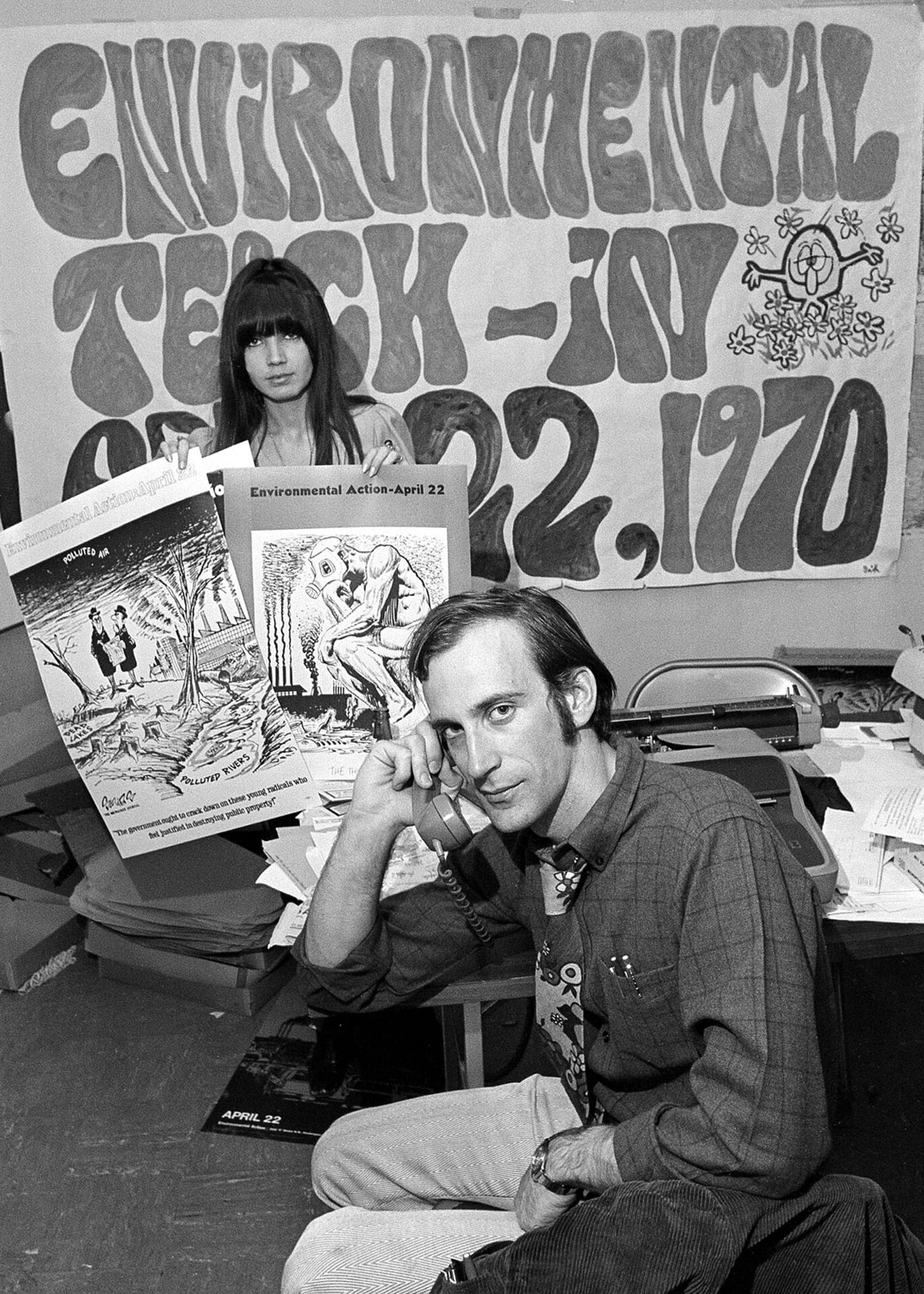

How Earth Day gave birth to environmental movement

The culture of Earth Day

Spirituality, social justice, and climate change meet at the crossroads

Liu is with Harvard Climate Leaders Program for Professional Students. Healy is with the Harvard Student Climate Change Conference. Both are students at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

HEALY: As a public health student I see so many environmental challenges, be it the 90 percent of the world who breathe unhealthy air, or the disproportionate effects of extreme heat on communities of color, or the environmental disruptions to the natural world and the zoonotic disease that humans are increasingly being exposed to. But the central commonality at the heart of all these crises is the climate crisis. Climate change, from the greenhouse-gas emissions to the physical heating of the Earth, is worsening all of these environmental crises. That’s why I call the climate crisis the great exacerbator. While we will all feel the effects of climate change, it will not be felt equally. Whether it’s racial inequity or wealth inequality, the climate crisis is widening these already gaping divides.

Solutions may have to be outside of our current road maps for confronting crises. I have seen the success of individual efforts and private innovation in tackling the COVID-19 pandemic, from individuals wearing masks and social distancing to the huge advances in vaccine development. But for climate change, individual efforts and innovation won’t be enough. I would be in favor of policy reform and coalition-building between new actors. As an overseer of the Harvard Student Climate Change Conference and the Harvard Climate Leaders Program, I’ve aimed to help mobilize Harvard’s diverse community to tackle climate change. I am also researching how climate change makes U.S. temperatures more variable, and how that’s reducing the life expectancies of Medicare recipients. The goal of this research, with Professor Joel Schwartz, will be to understand the effects of climate change on vulnerable communities. I certainly hope to expand on these themes in my future work.