An experiential exercise for teaching theories of work motivation: using a game to teach equity and expectancy theories

Organization Management Journal

ISSN : 2753-8567

Article publication date: 1 July 2020

Issue publication date: 27 November 2020

This paper aims to provide an experiential exercise for management and leadership educators to use in the course of their teaching duties.

Design/methodology/approach

The approach of this classroom teaching method uses an experiential exercise to teach Adams’ equity theory and Vroom’s expectancy theory.

This experiential exercise has proven useful in teaching two major theories of motivation and is often cited as one of the more memorable classes students experience.

Originality/value

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is an original experiential exercise for teaching the equity and expectancy theories of motivation.

- Work motivation

- Equity theory

- Expectancy theory

Experiential exercise

Swain, J. , Kumlien, K. and Bond, A. (2020), "An experiential exercise for teaching theories of work motivation: using a game to teach equity and expectancy theories", Organization Management Journal , Vol. 17 No. 3, pp. 119-132. https://doi.org/10.1108/OMJ-06-2019-0742

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Jordon Swain, Kevin Kumlien and Andrew Bond.

Published in Organization Management Journal . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Theories of work motivation are central to the field of management and are covered in many introductory management, leadership, human resource management and organizational behavior courses ( Benson & Dresdow, 2019 ; Steers, Mowday, & Shapiro, 2004 ; Swain, Bogardus, & Lin, 2019 ). Understanding the concept of work motivation helps undergraduate students prepare for leading and managing others. Teaching these concepts in the classroom allows students to experiment and share ideas with others in a lower-stakes environment than if they were in an actual place of work with other employees. But teaching students theories of work motivation is not easy. First, there are dozens of theories ranging from Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, to self-determination theory, to goal setting theory, to Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory (a.k.a. two-factor theory), to job characteristics theory, just to name a few ( Anderson, 2007 ; Holbrook & Chappell, 2019 ; Latham & Pinder, 2005 ; Locke & Latham, 1990 ). Second, students tend to evaluate the explanatory power of different motivational theories based on how they relate to their work and life experiences ( Anderson, 2007 ). This tendency to view motivation theories through the lens of personal experience poses a challenge for undergraduate level students who have limited work exposure; they often lack the context to make sense of the various motivational theories ( Mills, 2017 ). Therefore, to provide a common experience through which students can understand theories of work motivation, we developed an experiential activity. Specifically, we use an in-class basketball exercise. This experiential approach not only provides a common context for students to reference in applying theories of work motivation, but also incorporates elements of fun and competition, which have been shown to help engage students more fully ( Helms & Haynes, 1990 ; Azriel, Erthal, & Starr, 2005 ).

While there are numerous theories of work motivation ( Latham & Pinder, 2005 ), like others, we have found focusing on too many of these theories during one class overwhelms students and causes them to question academics’ understanding of the topic ( Anderson, 2007 ; Holbrook & Chappell, 2019 ). However, focusing on too few theories also limits students’ education and understanding of why multiple theories of motivation exist. We find that acknowledging the existence of multiple theories is advisable, and we suggest instructors emphasize the complexity of motivation, but that they do not try to force students to learn or apply the details of a large number of theories of motivation in a single class period. Therefore, our exercise focuses on two basic theories of work motivation – Vroom’s Expectancy Theory and Adams’ Equity Theory. We chose to focus on these two theories because they are among the most influential theories of work motivation ( Anderson, 2007 ; Holbrook & Chappell, 2019 ; Miner, 2003 ) and among the most frequently included in management and organizational behavior courses and textbooks ( Miner, 2003 ; Miner, 2005 ).

Theoretical foundation

Both expectancy and equity theories of motivation have been identified as important frameworks for teaching and understanding motivation, and both emphasize the cognitive approach to motivation ( Miner, 2003 ; Stecher & Rosse, 2007 ).

Adams’ equity theory centers on the perception of fairness ( Adams, 1963 ). When people feel they have been fairly treated, they are more likely to be motivated. When they feel they have not been fairly treated, their motivation will suffer. These perceptions of equity are derived from an assessment of personal input and outputs – or what people put into a task compared to what they receive as a result ( Adams, 1963 ; Kanfer & Ryan, 2018 ). Inputs can include things like time, effort, loyalty, enthusiasm and personal sacrifice. Outputs can include but are not limited to, thing likes salary, praise, rewards, recognition, job security, etc. But the theory is more complex than simply the assessment of personal inputs weighed against outputs. Adams’ equity theory also incorporates the concept of perceived equity ( Adams, 1963 ; Kanfer & Ryan, 2018 ). People compare their inputs and outputs to others. If they feel that another person is putting in the same level of effort, but getting more outputs as a result, that person’s motivation may suffer ( Kanfer, 1990 ; Kanfer & Ryan, 2018 ; Stecher & Rosse, 2007 ). This theory can be summarized using a visual equation that highlights how perceived equity can impact motivation ( Appendix 1 ). This same visual equation can help students understand how leaders can influence motivation in their subordinates; how leaders can impact equity. For example, if inequity exists, leaders may require subordinates to reduce personal inputs, or they may adjust the outcomes. They might also counsel their subordinates to change their comparison points (e.g. a low-level worker should not compare herself to a senior VP with 12+ years of experience).

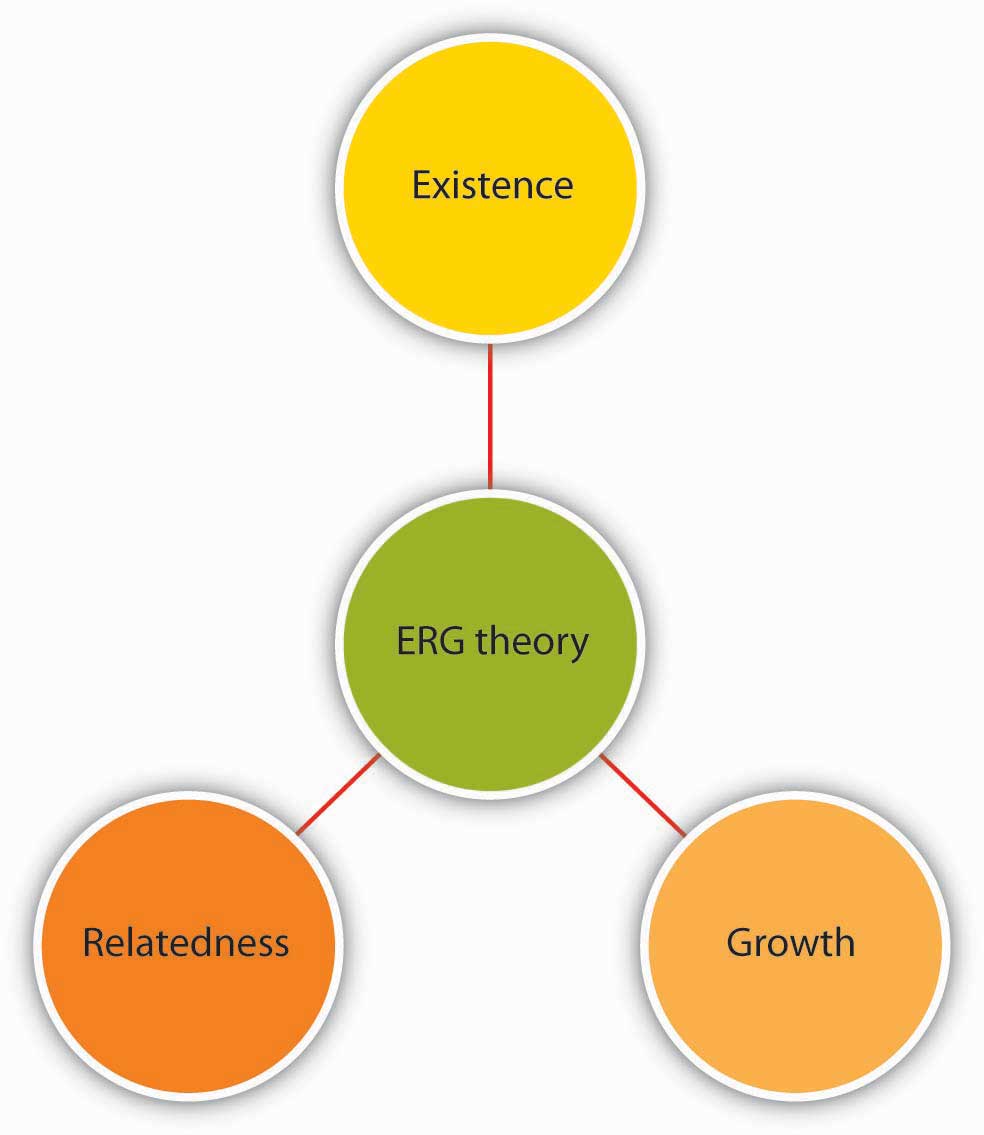

Expectancy : Is the individual properly trained and do they possess the necessary resources to effectively do the job?

Instrumentality : Does the individual trust that they’ll receive what they were promised if they do what they were asked?

Valence : Does the individual value the reward they were promised ( Kanfer & Ryan, 2018 )?

In this exercise, we use a mini basketball game in class to teach students about both Adams’ equity theory and Vroom’s expectancy theory. Using the game in class ensures students have a common context through which to apply and understand these two theories of work motivation. As noted by Stecher & Rosse (2007) , both theories offer compatible frameworks for understanding work motivation, yet they are most often taught as distinct non-related theories. We find that teaching these two theories using the same experiential exercise helps students understand the complexities of motivation. Specifically, this exercise helps students understand how multiple theories can explain motivation issues for the same situation.

Learning objectives

understand the complexity of motivation and its impact on performance;

explain differences in an individual’s motivation and behavior as a function of common psychological forces experienced by people; and

apply knowledge of work motivation theories to address issues of motivation.

Target audience.

This exercise is designed for undergraduate students in introductory courses in leadership, management, human resource management or organizational behavior – wherever theories of work motivation are covered. This approach has been used for over a decade teaching college juniors and seniors in a leadership course. While the approach has not been used to teach graduate students, there is no reason to believe it would not be an effective means for teaching those enrolled in an MBA program.

Class size.

The exercise has been used in classes ranging from 15 to 36 students. As participation by multiple students positively impacts the class, it is recommended the exercise be used for smaller classes. Time could become a factor in larger classes. Furthermore, space could prove a limiting factor in larger classes as some room is needed to set up the game.

Supplies needed.

mini basketball hoop and mini basketball (a trash can and wadded up paper can work if you do not have access to a small hoop and ball);

means for keeping time (stopwatch, wristwatch or wall clock with a second hand);

painter’s tape or note cards to annotate shot positions on the floor in the classroom;

one bag of miniature candy bars; and

slides of equity and expectancy theory to assist in de-brief ( Appendix 1 ).

This exercise as described can be completed in a single 75-min class session. If less time is available, we recommend instructors teach only one of the theories as outlined in this article (conduct only one of the two rounds of the game), covering the other theory during another class period.

a brief overview of work motivation by the instructor (via short lecture or through soliciting input from students to gauge the level of preparation) (10 min);

the first round of the game (10 min);

de-brief and application of equity theory (10 min);

the second round of the game (10 min);

de-brief and application of expectancy theory (10 min);

small group discussion on the future application of theories (15 min); and

structured de-brief of group discussions (10 min).

Student preparation before class.

It is recommended that instructors assign students readings focused on work motivation in advance of the class. A large number of organizational behavior or management textbooks contain chapters on this topic. At a minimum, the assigned reading should cover equity and expectancy theories.

Instructor preparation and classroom setup.

Instructors should set up the classroom with supplies they obtained before beginning class. A visual example of the classroom setup for Rounds 1 and 2 of the exercise can be found in Appendix 2 . The mini-basketball hoop should be located in front of the classroom where all the students can see it. Depending on the size/shape of the classroom, the shooting positions for Rounds 1 and 2 of the exercise can be placed in any location. The shooting position for Round 1 should be a moderately difficult shot, perhaps two to three steps away from the basket. Mark the position with tape or a notecard.

Round 2 requires three different shooting positions. Each position should be marked with tape or a notecard. The first position is the “easy” shot. It should be very close to the basket (1-2 steps in front of the basket). The purpose of this first position is to create the opportunity for a shot that the average person would have lots of confidence in making (high expectancy). The second position should be further away (six to eight steps away from the basket) and potentially behind a row of desks for some added difficulty. The purpose of this second position is to create a shot of medium level difficulty where students are not completely confident (lower expectancy) that they will be able to make it. The third position should be the hardest shot that you can create while still leaving a very small possibility of the shot being made (lowest expectancy). It is recommended you make the student stand outside of a doorway so that they have to shoot a strange trajectory. If your classroom space is not big enough to support making a shot position that is far away from the basket, you can instead add difficulty by requiring the student to wear a blindfold or to shoot backwards. For the positions needed for Round 2 of the exercise, instructors should test the positions and ensure the three different locations are of varying difficulty and that the third position is an extremely difficult (almost impossible) shot to make.

Running the exercise

Introduction to motivational theories (10 min).

Given the number of motivational theories that exist in the academic world, we find it helpful to acknowledge this initially with students to highlight the overall complexity of the topic. In this introduction, instructors can briefly highlight the variety of motivational theories that exist (e.g. expectancy, equity, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, self-determination theory, goal setting theory, Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory, job characteristics theory, etc.). This can be done in any number of ways – asking students to list and/or briefly describe the various theories covered in their assigned reading, etc. Teachers should tailor this introduction based on their specific situation (e.g. the content of assigned reading, length of class, etc.). After talking through the variety of theories that exist, it is important to highlight to students that these theories should be viewed more as a conceptual toolbox for them to use in different situations as opposed to viewing all of these theories as a group of non-congruent viewpoints all competing to be the truest ( Anderson, 2007 ).

After a brief review of the assigned reading(s), instructors can tell students that they are going to play a game to apply what they have learned.

Round 1 of the game (10 min)

Ask all of the students to stand up and tell them to stretch out, limber up, and get prepared for a mini-basketball competition. During this session, the instructor will provide students with an exciting and competitive experience to which they can apply the concepts of Adams’ Equity Theory.

Divide students into four even teams. Have students move around and sit with their team as a group. Explain that Team 1 will compete against Team 2 in a basketball shootout. Establish an incentive of your choice – candy often works well. Show this incentive to the students. Now call Team 1 and Team 2 up to the front of the class and instruct them that:

[…] you can take as many shots as you want at the hoop in 60 seconds, but everybody in your team needs to shoot at least once. The team that ends up with the most baskets made will win. Team 1, you will go first.

Use a stopwatch or watch with a second hand to keep time and instruct members of the opposing team to keep score.

Once Team 1 completes their turn, record their score and call Team 2 forward. Before allowing Team 2 to start their turn, move the shooting spot three paces further away from the basket (move the tape or notecard back three paces).

You will likely experience negative feedback from Team 2 after moving the basket. Common responses include, “this isn’t fair.” Pay close attention to the complaints that they use, these are often very useful to bring up during the discussion portion of the exercise. You might respond lightheartedly with “life isn’t fair” or “what, are you scared?” Allow Team 2 to complete their turn, paying close attention to their affect and comments. If done correctly, Team 2 should lose to Team 1. Congratulate Team 1 on their excellent performance and give each member of Team 1 their prize (a small candy bar works well) and have both Teams 1 and 2 return to their seats.

Now call Team 3 forward. Instruct them that will have 60 s to shoot from the same spot that Team 2 shot from. Keep time and have a member from Team 4 count the baskets. When time is up, record the score. Now call Team 4 forward. Have them shoot from the same spot Team 3 did. Start the clock. However, do not stop the team from shooting after 60 s. Let them continue to shoot for an additional 30 s – or longer – until you hear the members of Teams 1, 2 and 3 start questioning how much time Team 4 is getting to shoot. Record the number of shots made. Team 4 should beat Team 3. Congratulate team 4. Do NOT give Team 4 any candy for winning. Have Teams 3 and 4 return to their seats.

Round 1 de-brief and application of equity theory (10 min)

This is where the instructor begins to apply Adams’ equity theory to the scenario. Ask students if anyone is feeling unsatisfied or unmotivated. You should have several hands go up. If not, remind them of the negative comments you heard during the game – calling on students by name if necessary. Now start to inquire as to why people said what they did.

At this point, the instructor should put up the slide with Adams’ equity theory on it ( Appendix 1 ) and ask students to explain what happened using the equation on the slide. The class should point out several areas where “the equation does not balance.” For example, the inputs for Team 1 were less than the input for Team 2. Team 2 had a harder shot and, therefore, had to provide more inputs (work harder). Students should also point out that the outputs were not even. Team 4 beat Team 3 (just as Team 1 beat Team 2), but Team 4 did not receive the same outcome/reward. Less clear is the factor of Team 4 having more time than Team 3. Ask students how this factor impacts motivation using equity theory.

Pass out candy to all members of the class – to reduce feelings of inequity. Keep three pieces of candy for Round 2.

Round 2 of the game (10 min)

Now tell the class that you are going to ask for three volunteers. Inform the class that if they volunteer and are selected, they have a choice to make – they must choose one of three shooting/prize positions.

Shooting Position #1. Tell the students that if they choose shooting position #1, they get to shoot from the closest spot (and show them where it is). Let them know that they can take three practice shots and that for making a basket, they will receive a piece of candy.

Shooting Position #2. Tell students if they choose this option, they get to shoot from the spot of moderate difficulty and show them where it is. Let them know they get one practice shot and that their prize for making the basket is something of medium desirability – perhaps lunch paid for by the instructor at a local moderately priced restaurant of the student’s choice.

Shooting Position #3. Tell students that if they choose this option, they get to shoot from the most difficult spot and show them where it is. Tell them that they do not get any practice shots from this location. Promise an extremely desirable reward (high valence) and also something that the students may question whether you have the power to give it to them (low instrumentality). A great example is offering them the ability to get out of having to do a major course requirement such as a capstone project or thesis paper. You could also offer something like getting to park in the Dean’s parking spot for the rest of the semester. The creativity behind choosing this third reward is that you want to find the balance of a reward that is extremely high in desirability, but also something that in hindsight students should realize was probably outside of your ability to deliver on that reward (low instrumentality). By creating a reward that is somewhat unrealistic for shooting position #3, the instructor will allow for a follow-on discussion about the power of instrumentality in Vroom’s expectancy theory. If a student questions whether or not they will receive the reward by meeting the performance outcome (making the shot), then their instrumentality will be lower which may alter the position they select to shoot from.

Now that all three shooting positions have been described, pick three volunteers at random and have them come to the front of the room. Ask the first student what option she would like to choose and have her take the shot. Repeat for the second and third students (students can all shoot from the same spot if they desire). After the final volunteer chooses the shooting position and takes the shot, have students return to their seats and prepare for the de-brief.

Round 2 de-brief and application of expectancy theory (10 min).

After the volunteers have returned to their seats, the instructor can display the Vroom’s expectancy theory slide ( Appendix 1 ) to begin shaping the class conversation in terms of Vroom’s expectancy theory.

Individual behavior = the physical act of shooting the basketball;

Performance outcome = making the basketball in the hoop; and

Reward outcome = the prize received based on making the shot from the shooting position the student chose.

Next, ask the students to break down each of the three options in terms of expectancy, instrumentality and valence . The following should come out in the discussion:

Expectancy – Shooting position #1 has the highest expectancy of all three positions. Self-efficacy is increased through multiple practice shots and the close distance makes the shot seem achievable.

Instrumentality – Shooting position #1 should have a high level of instrumentality. Students know you have the candy bar and that you delivered on what you promised during round 1. Therefore, it is likely they trust and believe they will receive the reward candy bar for achieving the performance outcome of making the shot.

Valence – Shooting position #1 likely has the lowest valence of all three positions in terms of overall value. However, valence could run from low to high depending on individual preference. The candy bar may have lower valence if students do not like the particular candy bar.

Expectancy – Lower than shooting position #1 because the shot is more difficult, and the student only gets one practice shot. However, the expectancy of shooting position #2 is still greater than shooting position #3 because the shot is easier and the student still receives a practice shot which raises the student’s confidence in their ability to achieve the performance outcome of making the shot.

Instrumentality – Lower than shooting position #1, but higher than shooting position #3. There might be some trust issues related to whether the students will receive the lunch. As the student does not immediately get the reward of the free lunch by achieving the performance outcome of making the shot, the instrumentality may be low. The instrumentality should still be higher than shooting position #3 because the student should have more trust that the instructor will buy them lunch as compared to not having to write the final paper for the class.

Valence – Should be higher than position 1 since lunch is more expensive than just a candy bar. However, individual preferences again may vary depending on if the students have free time in their schedule or if they would even like to have lunch with their professor.

Expectancy – The lowest of all three positions as there is no practice shot and the difficulty of the shot is so high that students do not really believe that they will be able to make the shot.

Instrumentality – Should be the lowest of all three positions as the reward may seem so great that some students will doubt if the instructor will follow through on giving the reward, or if they even have the power to give out the reward. But this may not be rated by students as low initially.

Valence – The highest of all three positions. The reward of not having to write a final paper, or some other exclusive reward (parking in the Dean’s parking spot) should be viewed as extremely appealing to most students given the high value they place on their time in a busy college schedule.

After going through each of the shooting positions, have the non-participating students in the classroom evaluate the multiplicative factors for each shooting position and ask them if it makes sense why each student chose to shoot from where they did.

Small group discussion on the future application of theories (15 min)

After students have had a chance to run through both games as well as the de-brief for each exercise, it is now time to turn the discussion toward an application of both theories to future leadership situations. Break students back out into the teams they were on for the Adams’ equity theory portion of the class. Instruct the groups they will have 15 min to talk amongst themselves to brainstorm examples of personal experiences or potential future scenarios where they can apply Adams’ equity theory and Vroom’s expectancy theory. Examples that often come up range from peers on group projects receiving the same reward/recognition even though they contributed less, gender discrepancies in pay or promotion, poor incentive systems, etc.

Structured de-brief of group discussion (10 min)

Spend the last 10 min of this class asking each group of the teams to share an example they discussed within their small group. Ensure that you press the students to use the correct terminology when talking about their examples through the lens of either Adams’ equity theory or Vroom’s expectancy theory and ask them how they might positively impact motivation in the scenario they discussed.

Potential challenges.

Challenge : The instructor does not properly manage time for a thorough debrief of each exercise

09:30-09:40. A brief overview of work motivation theories;

09:40-09:50. The first round of the game (Adams’ equity theory);

09:50-10:00. De-brief round one exercise and apply Adams’ equity theory;

10:00-10:10. The second round of the game (Vroom’s expectancy theory);

10:10-10:20. De-brief round two exercise and apply Vroom-s expectancy theory;

10:20-10:35. Small group discussion on the future application of theories; and

10:35-10:45. Structured de-brief of group discussions.

Challenge: A student manages to make the impossible shot

Solution: In the event that a student does make the nearly impossible shot from shooting position #3 (this did happen in one instance and it turned into a viral Instagram video with over 20,000 views) then the instructor needs to be prepared to not follow through on the reward. Instead, the instructor should discuss the concept of instrumentality and how the trust between a leader and their direct reports is essential to ensuring positive motivation in the workplace. This is why it is important that the reward for shooting position #3 is somewhat unbelievable in the first place because it will allow for a great discussion on instrumentality and the belief that achieving a performance outcome will lead to a given reward. The instructor can begin by polling the students to see how many of them completely believed that the reward for shooting position #3 was realistic and attainable. Through this discussion, the instructor can highlight what happens to motivation when managers create extremely difficult goals (low expectancy) with extremely valuable rewards (high valence) to try and motivate their workers. This also provides a strong example to the students of what happens to trust when a leader fails to follow through on a promised reward and how that will impact instrumentality and thus motivation in the future.

Challenge: Students may not have real-life examples to discuss in their groups.

Solution. If group discussion is lagging, the teacher can suggest situations that students may have experienced or direct them to use the internet to find examples and to discuss those instances.

This experiential exercise has proven useful over the past 10 years in providing an introductory look at the complexity of workplace theories of motivation. In semester-end student feedback, this class has been mentioned numerous times as one of the most impactful lessons of the course. Multiple students have commented on the effectiveness of the hands-on exercise in creating a memorable point of reference that makes it easier to retain class learning concepts. In fact, the most recent end of course feedback over one-third of students cited this lesson as the most memorable of the 30-lesson course. Additionally, the in-class exercise provides a common context for students with varying experiences to engage with and allows for the introduction and application of two of the major theories of motivation. Furthermore, the fun, competitive format generates interest and excitement. Note, we have also used miniature golf instead of basketball to teach each theory – having students putt with different equipment, from different distances, and for different prizes. For a brief overview on the setup using mini-golf, please see Appendix 3 . We encourage faculty to have fun with the exercise – it is not just for the students!

Adams’ equity theory

Vroom’s expectancy theory

Setup for Round #1 – Adams’ equity theory

Setup for Round #2 – Vroom’s expectancy theory

Setup for Vroom’s expectancy theory using mini-golf

Appendix 1. Sample slides for use in de-briefing

Appendix 2. sample classroom setups for rounds 1 and 2, appendix 3. instructions for use of mini-golf instead of basketball.

If the classroom does not allow for the setup of the three different shooting positions for the basketball exercise, then it is easy to replace the basketball exercise with a mini-golf option. Below is a brief highlight of the differences in classroom setup for the golf exercise.

putter, golf ball and plastic solo cup;

painter’s tape or note cards to annotate shot positions on the floor in the classroom; and

bag of miniature candy bars.

Round 1 Exercise (Adams’ equity theory)

There are no major changes needed for this round. Simply follow the same instructions for Round 1 of the basketball exercise, except instead of basketball shots replace that with made putts into the solo cup. This will still allow for the same comparison and perceived inequities amongst the four teams that will create a rich discussion on Adams’ equity theory.

Round 2 Exercise (Vroom’s expectancy theory)

Again, there are no major changes needed for this round, other than just replacing the concept of a made basketball shot with a made putt. Below is an example of the three putting positions and how you can still create a similar scenario to the basketball exercise in terms of expectancy , instrumentality and valence for each putting position.

Putting Position #1: Create a short two-foot putt that is fairly easy to make. Allow the student to have three practice putts. This creates an option with high expectancy (an easy putt with practice shots), high instrumentality (the student believes that if they make the putt, they will receive the candy) and low valence (candy is not as valuable as lunch or getting out of writing a final paper).

Putting Position #2: Create a six-foot putt that is not straight on but instead is at a slight angle to the cup so that it is more difficult to make. Allow the student to have only one practice putt. This creates an option with a medium level of expectancy (a slightly more difficult putt), a medium level of instrumentality (the student has to trust that you will actually buy them lunch at some point in the future) and a medium level of valence (the lunch is greater than the candy bar, but most likely not as valuable as not writing the final paper).

Putting Position #3: Create the longest most difficult putt that your classroom will allow. Additionally, tell the students they will receive no practice putts and they will have to putt with the handle end of the putter. This creates an option with a very low level of expectancy (students will have a very low level of belief that they can make the putt given both the distance and the fact that they have to putt with the handle), a low level of instrumentality (again the reward should be so valuable that some students will doubt the reality of actually receiving the reward) and a very high level of valence (the reward should be extremely desirable).

Adams , J. S. ( 1963 ), Toward an understanding of inequity . The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology , 67 ( 5 ), 422 – 436 . doi: 10.1037/h0040968 .

Anderson , M. H. ( 2007 ). Why are there so many theories? A classroom exercise to help students appreciate the need for multiple theories of a management domain . Journal of Management Education , 31 ( 6 ), 757 – 776 . doi: 10.1177/1052562906297705 .

Azriel , J. A. , Erthal , M. J. , & Starr , E. ( 2005 ). Answers, questions, and deceptions: what is the role of games in business education? Journal of Education for Business , 81 ( 1 ), 9 – 13 . doi: 10.3200/JOEB.81.1.9-14 .

Benson , J. , & Dresdow , S. ( 2019 ). Delight and frustration: using personal messages to understand motivation . Management Teaching Review , available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298119851249 doi: 10.1177/2379298119851249 .

Helms , M. , & Haynes , P. J. ( 1990 ). Using a “contest” to foster class participation and motivation . Journal of Management Education , 14 ( 2 ), 117 – 119 . doi: 10.1177/105256298901400212 .

Holbrook , R. L. Jr. , & Chappell , D. ( 2019 ). Sweet rewards: an exercise to demonstrate process theories of motivation . Management Teaching Review , 4 ( 1 ), 49 – 62 . doi: 10.1177/2379298118806632 .

Kanfer , R. ( 1990 ). Motivation theory and industrial and organizational psychology . In Dunnell , M.D. and Hough , L.M. (Eds), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology , 1 , Consulting Psychologists Press , 75 – 170 .

Kanfer , R. , & Cornwell , J. F. ( 2018 ). Work motivation I: definitions, diagnosis, and content theories . In Smith , S. , Cornwell , B. , Britt , B. and Eslinger , E. (Eds), West point leadership , Rowan Technology Solutions .

Kanfer , R. , & Ryan , D. M. ( 2018 ). Work motivation II: situational and process theories . In Smith , S. , Cornwell , B. , Britt , B. , & Eslinger , E. (Eds), West point leadership , Rowan Technology Solutions .

Locke , E. A. , & Latham , G. P. ( 1990 ). Work motivation and satisfaction: light at the end of the tunnel . Psychological Science , 1 ( 4 ), 240 – 246 . doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00207.x .

Latham , G. P. , & Pinder , C. C. ( 2005 ). Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century . Annual Review of Psychology , 56 , 485 – 516 . doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142105 .

Mills , M. J. ( 2017 ). Incentivizing around the globe: educating for the challenge of developing culturally considerate work motivation strategies . Management Teaching Review , 2 ( 3 ), 193 – 201 . doi: 10.1177/2379298117709454 .

Miner , J. B. ( 2003 ), The rated importance, scientific validity, and practical usefulness of organizational behavior theories: a quantitative review . Academy of Management Learning and Education , 2 , 250 – 268 . doi: 10.5465/amle.2003.10932132 .

Miner , J. B. ( 2005 ). Organizational behavior 1: Essential theories of motivation and leadership , M.E. Sharpe .

Stecher , M. D. , & Rosse , J. G. ( 2007 ), Understanding reactions to workplace injustice through process theories of motivation: a teaching module and simulation . Journal of Management Education , 31 ( 6 ), 777 – 796 . doi: 10.1177/1052562906293504 .

Steers , R. M. , Mowday , R. T. , & Shapiro , D. L. ( 2004 ). The future of work motivation theory . The Academy of Management Review , 29 ( 6 ), 379 – 387 . doi: 10.2307/20159049 .

Swain , J. E. , Bogardus , J. A. and Lin , E. ( 2019 ). Come on down: using a trivia game to teach the concept of organizational justice . Management Teaching Review , available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/2379298119892588

Van Eerde , W. , & Thierry , H. ( 1996 ). Vroom’s expectancy models and work-related criteria: a meta-analysis . Journal of Applied Psychology , 81 (5) , 575 . doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.81.5.575 .

Vroom , V. H. ( 1964 ). Work and motivation , Wiley .

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

Use motivation theory to inspire your team’s best work

5 frameworks for understanding the psychology behind that elusive get-up-and-go.

Get stories like this in your inbox

5-second summary

- Motivation theories explore the forces that drive people to work towards a particular outcome.

- These frameworks can help leaders who want to foster a productive environment understand the psychology behind human motivation.

- Here, we’re outlining five of the most common motivation theories and explaining how to put those theories into practice.

A huge part of a leader’s job is creating an environment where productivity thrives and teams are inspired to do their best work. But that uniquely human brand of motivation can be quite slippery – hard to understand, inspire, and harness.

An academic foundation on motivational theory can help, but opening that door exposes you to enough theoretical concepts and esoteric language to make your eyes glaze over.

This practical guide to motivation theories cuts through the jargon to help you get a solid grasp on the fundamentals that fuel your team’s peak performance – and how you can actually put these theories into action.

What is motivation theory?

Motivation theory explores the forces that drive people to work towards a particular outcome. Rather than accepting motivation as an elusive human idiosyncrasy, motivation theories offer a research-backed framework for understanding what, specifically , pushes people forward.

Motivation theory doesn’t describe one specific approach – rather, it’s an umbrella category that covers a slew of theories, each with a different take on the best “recipe” for motivation in the workplace.

CONTENT THEORIES VS. PROCESS THEORIES

At a high level, motivation theories can be split into two distinct categories: content theories and process theories .

- Content theories focus on the things that people need to feel motivated. They look at the factors that encourage and maintain motivated behaviors, like basic needs, rewards, and recognition.

- Process theories focus on individuals’ thought processes that might impact motivation, such as behavioral patterns and expectations.

5 motivation theories to inspire your team

Celebrate those little wins to keep your team motivated

A quick Google search will reveal dozens of different approaches that promise to unlock relentless ambition on your team.

It’s not likely that a single motivation theory will immediately ignite human-productivity hyperdrive. But the psychology happening behind the scenes gives unique insight into the components that influence human motivation. Leaders can then build on that foundation to create an environment that’s conducive to better focus and enthusiasm.

Let’s get into five of the most common and frequently referenced theories.

1. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

One of the most well-known motivation theories, the hierarchy of needs was published by psychologist Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “ A Theory of Human Motivation .”

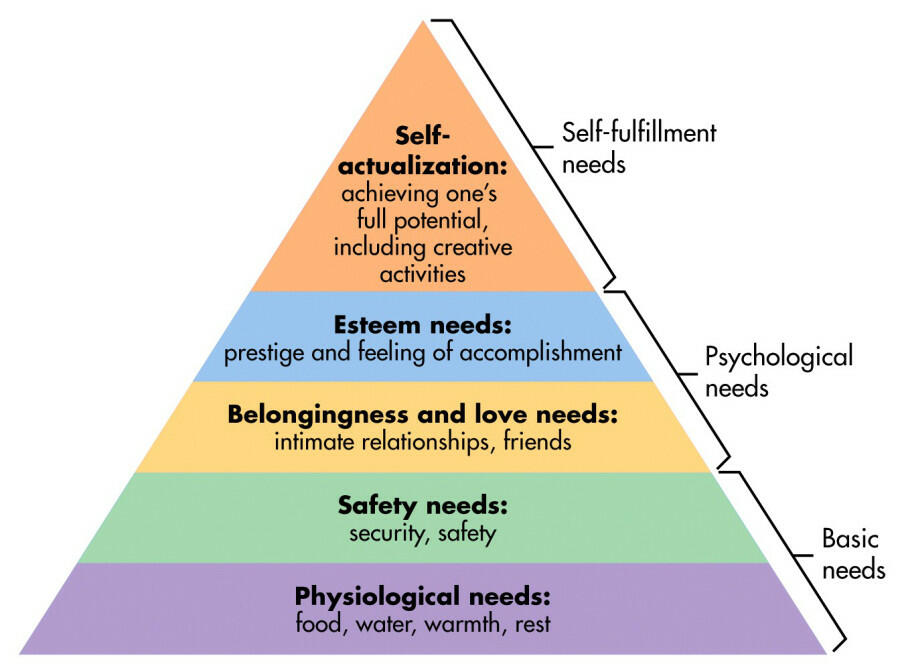

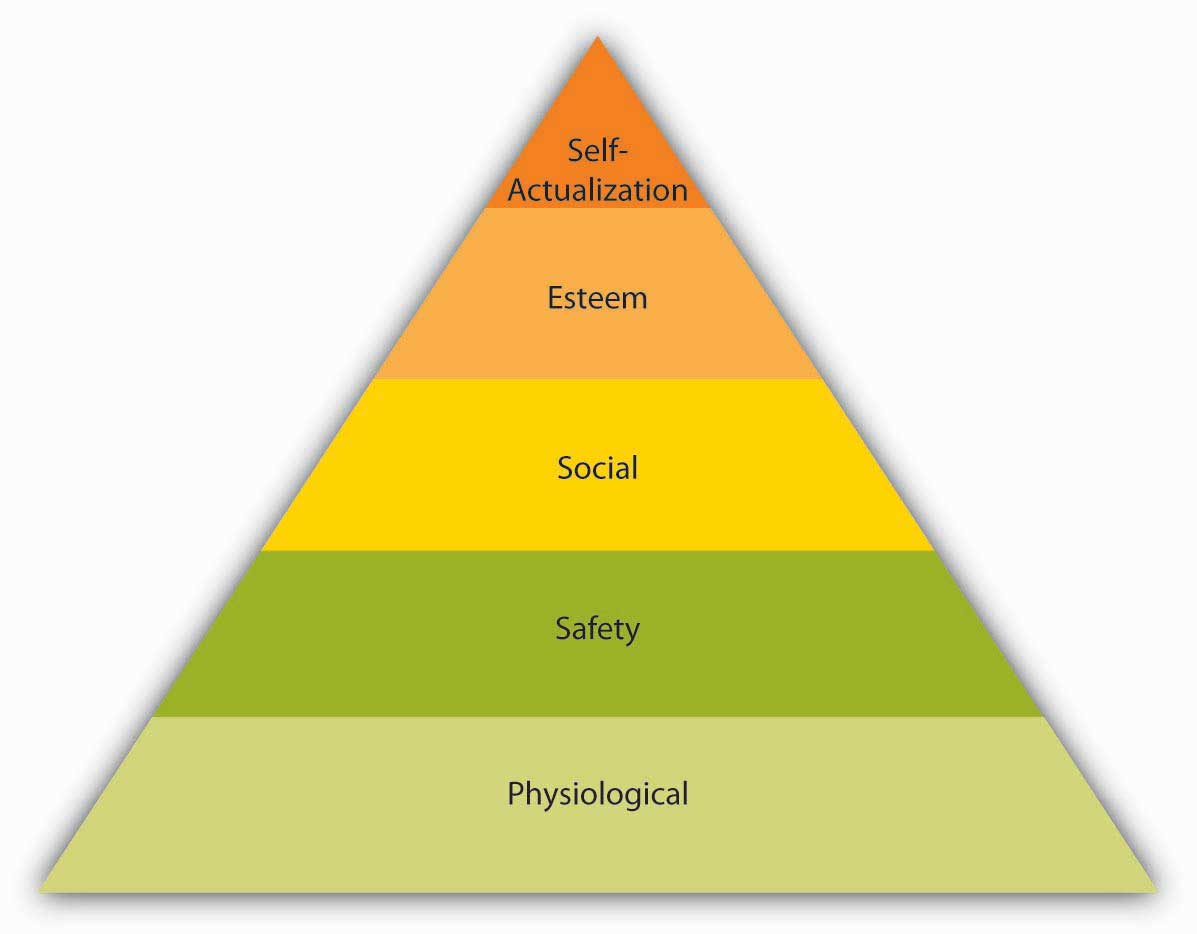

The gist is that Maslow’s hierarchy outlines five tiers of human needs, commonly represented by a pyramid. These five tiers are:

- Physiological needs: Food, water, shelter, air, sleep, clothing, reproduction

- Safety needs: Personal security, employment, resources, health, property

- Love and belonging: Family, friendship, intimacy, a sense of connection

- Esteem: Status, recognition, self-esteem, respect

- Self-actualization: The ability to reach your full potential

As the term “hierarchy” implies, people tend to seek out their basic needs first (which make up the base of the pyramid). After that, they move to the needs in the next tier until they reach the tip of the pyramid.

In this same paper, however, Maslow clarifies that his hierarchy of needs isn’t quite as sequential as the pyramid framework might lead people to believe. One need doesn’t necessarily have to be fully met before the next one becomes pertinent. These human needs do build on each other, but they’re interdependent and not always consecutive. As Maslow himself said , “No need or drive can be treated as if it were isolated or discrete; every drive is related to the state of satisfaction or dissatisfaction of other drives.”

The iconic pyramid associated with Maslow’s theory wasn’t actually created by Maslow — and is even considered somewhat misleading, as you don’t need to “complete” each level before moving forward. The pyramid was popularized decades later by a different psychologist who built upon Maslow’s work along with other management theories.

Maslow’s theory was originally focused on humans’ fundamental needs generally, but in the intervening decades, it’s frequently been adapted and applied to workplaces.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs in practice

The biggest lesson for leaders here is that you need to have the basics in place before anything else. Because Maslow’s tiers build on each other, a promotion won’t do much to motivate your team members if they’re concerned about the safety of their work environment.

Do your team members feel that they have some level of job security? Are they adequately paid? Do they have safe working conditions? Those are the base requirements you need to meet first.

The hierarchy of needs can support a more holistic approach to management, so you can confirm basic needs and then evolve a more nuanced idea of what people need to thrive. Do they have solid connections with you and their colleagues? Do they receive adequate recognition? Do they have some autonomy in their position?

2. Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory (AKA dual-factor or two-factor theory)

Frederick Herzberg, a behavioral scientist, created the motivation-hygiene theory in 1959. The theory is a result of his interviews with a group of employees, in which he asked them two simple questions:

- Think of a time you felt good about your job. What made you feel that way?

- Think of a time you felt bad about your job. What made you feel that way?

Through those interviews, he realized that there are two mutually exclusive factors that influence employee satisfaction or dissatisfaction – hence, this theory is often called the “two-factor” or “dual-factor” theory. He named the factors:

- Hygiene encompasses basic things like working conditions, compensation, supervision, and company policies. When these nuts and bolts are in place, employee satisfaction remains steady – it’s the absence of them that moves the needle. When they’re missing, employee satisfaction decreases.

- Motivators are things like perks, recognition, and opportunity for advancement. These are the factors that, when present, increase employee motivation, productivity, and commitment.

Here’s the easiest way to think of this theory: Hygiene issues will cause dissatisfaction with your employees (and that dissatisfaction will hinder their motivation). Motivators improve satisfaction and motivation – but only when healthy hygiene is in place.

Herzberg’s theory in practice

Herzberg’s two-factor theory is often described as complementary to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as both place an emphasis on ensuring an employee’s basic needs – like security, safety, and pay – are being satisfied.

Maslow’s theory is more descriptive, and gives you a comprehensive understanding of the human needs that drive motivation. Herzberg’s theory focuses specifically on prescriptive takeaways for the workplace, giving managers a simple, two-part framework they can use to confirm the presence of hygiene factors before trying to leverage any motivators.

3. Vroom’s expectancy theory

The premise behind Vroom’s expectancy theory , established by psychologist Victor Vroom in 1964, is pretty straightforward: We make conscious choices about our behavior, and those choices are motivated by our expectations about what will happen. In other words, we make decisions to pursue pleasure and avoid pain.

The nuance lies in Vroom’s finding that people value outcomes differently. To unpack that added layer of complexity, Vroom dug a little deeper to explain two psychological processes that influence motivation:

- Instrumentality: People believe that a reward will correlate to their performance.

- Expectancy: People believe that as they increase their effort, the reward increases too.

Vroom’s theory indicates that people need to be able to anticipate the outcome of their actions and behaviors. And, if you want to boost motivation, they need to care about those outcomes.

Vroom’s expectancy theory in practice

The one thing your career development plan is missing

Remember that everyone on your team might not be motivated by the same rewards, so your first step is to understand what each of your team members value so you can create opportunities for corresponding outcomes. From there, you can set clear expectations that connect performance to their desired rewards. (This is also what a career development plan does, by the way).

Of course, not every single expectation has a reward directly attached to it. Employees are required to fulfill the responsibilities of their jobs simply because…it’s their job.

Vroom’s theory is all about seeking pleasure and minimizing pain. So, in situations where a reward isn’t relevant, make sure employees are in the loop on what the consequences are if expectations aren’t met.

4. Reinforcement theory

The reinforcement theory is a piece of a broader concept called operant conditioning , which is often credited to psychologist, B.F. Skinner. However, Skinner’s work builds on the law of effect , established by Edward Thorndike in 1898.

Despite its convoluted origins, this is another theory with a simple premise: Consequences shape our behaviors. We’ll repeat behaviors that are reinforced, whether that means they lead to a positive outcome (positive reinforcement) or they end or remove a negative outcome (negative reinforcement).

This theory doesn’t focus on our internal drivers – it’s all about cause and effect. If we do something and like the result, we do it again.

Reinforcement theory in practice

Because this theory is so strongly correlated to human nature (hey, you probably weren’t eager to touch a hot stove again after it burned you once, right?), it’s one of the most intuitive to apply on your team.

When an employee does something desirable, reward that behavior – whether in the form of well-deserved recognition, taking a dreaded task off their plate, or offering a more tangible perk like an extra day off.

5. Self-determination theory

5 questions about motivation with Daniel Pink

The self-determination theory , introduced by psychologists Richard Ryan and Edward Deci in their 1985 book , focuses on finding motivation within yourself.

Ryan and Deci argue that motivation shouldn’t necessarily be derived from dangling carrots or waving sticks at people. That type is what they refer to as controlled motivation , in which people choose their behaviors based on external results.

Far more powerful than that, the psychologists argued, is autonomous motivation (also known as intrinsic motivation). Under these circumstances, people feel motivated when their choices are aligned with their internal goals and beliefs. Their behaviors aren’t directed by external approval, rewards, and punishments. Instead, their behaviors are self-determined.

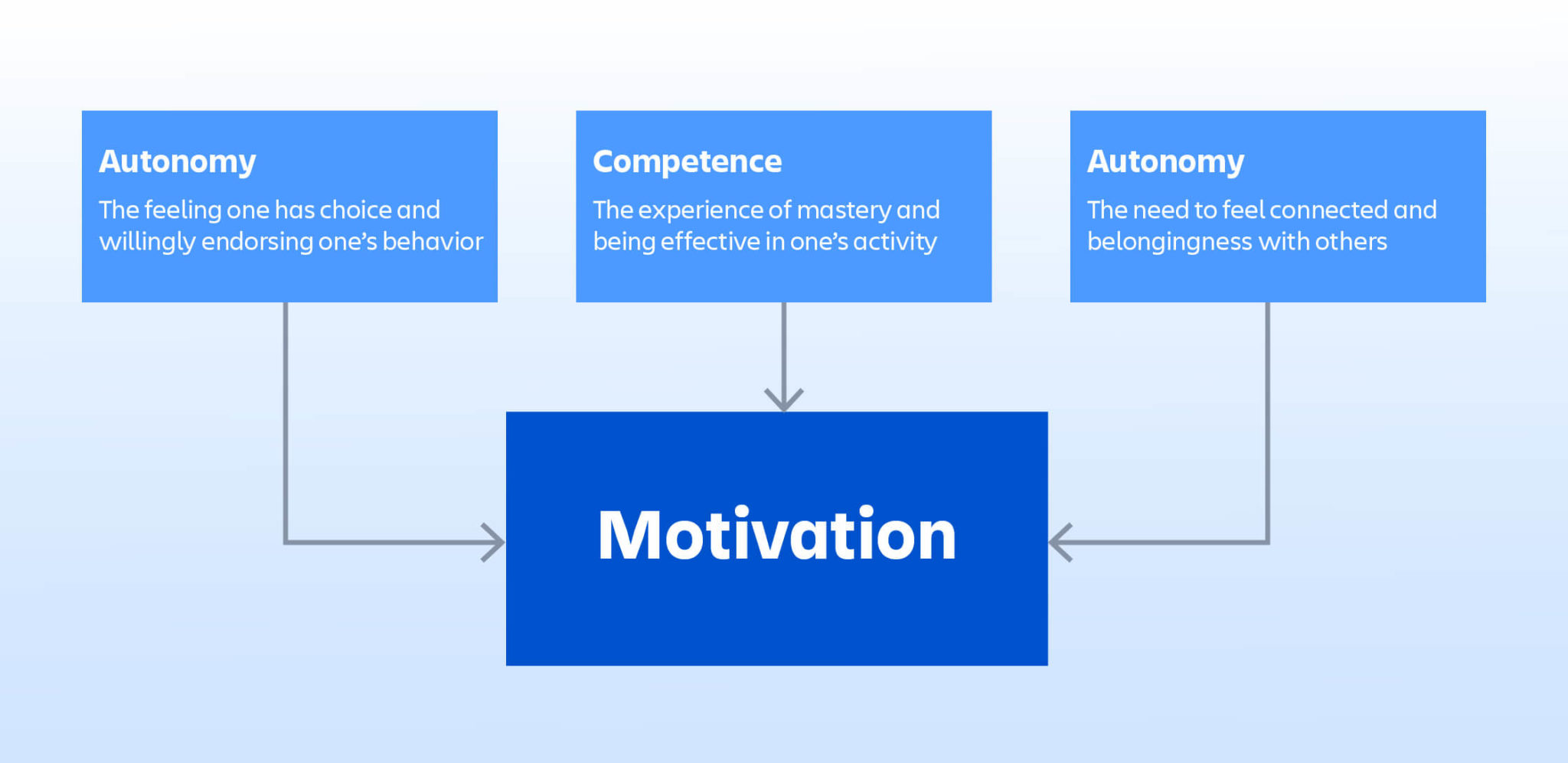

Autonomous motivation doesn’t happen on its own. To get there, people need to have three psychological needs met:

- Autonomy: The feeling that they have a choice and some ownership over their behavior

- Competence: The feeling that they are knowledgeable and capable

- Relatedness: The feeling that they are connected to others

When those three boxes are checked, people are better equipped to pull motivation from within, rather than relying on the external factors that are central to so many other motivation theories.

Self-determination theory in practice

You might guess that meeting those three core psychological needs is crucial for this theory – and there’s no need to overcomplicate it.

Here are a few ideas:

- Autonomy: Give employees flexible schedules and the ability to decide for themselves when and where they do their best work.

- Competence: Offer additional trainings and learning opportunities to continue to refine their skills.

- Relatedness: Provide outlets – whether it’s designated Slack channels or team outings – for team members to bond and get to know each other on a more personal level.

That’s not an exhaustive list. You have room to get creative and find other ways to boost your employees’ sense of ownership, proficiency, and connection.

Motivation doesn’t have to be a mystery

Motivation can feel fickle – like a fleeting phenomenon that magically happens when conditions are just right .

But, as your team’s leader, it’s your responsibility to conjure that “just right” environment where people can perform their best work.

You don’t need to be a mind reader to make that happen. Motivation theory can help you identify methods among the madness and create an environment where a high-level motivation is a constant – not a fluke.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

Employee Motivation: Theories in Practice Case Study

Introduction, theoretical framework, conclusion and recommendations, works cited.

The functioning of any company critically depends on its employees, their performance, and readiness to contribute to the further evolution of the firm. For this reason, modern management primarily focuses on the creation of conditions under which workers will be able to show their best results. Accepting the importance of this approach, one can also admit the reconsideration of the approaches to leadership and motivation as two basic elements needed to create a positive working atmosphere and ensure that all individuals within a team will have the desired level of commitment to achieve the outlined goals and form the basis for the company’s further rise. The importance of these two elements is evidenced by the fact that the emergence of problems in one of these domains along with the gaps in knowledge or critical flaws might precondition the decline in motivation and performance levels along with the collapse of the company.

The offered case study revolves around a similar problem. Rohit Narang, a new worker of Apex Computers, is inspired by a perfect opportunity to continue career growth by working at the more promising character if to compare with his previous employer, Zen Computers. Rohit belongs to a team consisting of five members, including its head Aparna Metha. However, he starts to face the first problems because of the lack of motivation. Having discovered a problem and create a solution for it, he presented it to Aparna, but no feedback was received. The team was also unwilling to discuss it as the leader always offers other solutions that should be accepted by team members without discussions. As far as Rohit has experience of another type of leadership demonstrated by his previous boss, who provided an opportunity to learn by making mistakes, he starts to feel disappointed and demotivated to continue working and create innovative or creative solutions that can be used by the company.

Before analyzing this very situation and answering questions, it is critical to creating the theoretical background preceding the discussion and contributing to its improved understanding. As it has already been stated, the leadership and motivation issues play a critical role in this situation; moreover, they are interconnected, which means that the investigation of the problem is impossible without their comprehension. Thus, the modern approach to leadership states that the central role of any leader is to inspire and motivate his/her followers to ensure the achievement of the best possible results and contribute to the future development of organizations (Gordon 56). There are also various leadership styles that can be utilized depending on the situation and the existing goals. The choice of the correct way to work with employees preconditions success and the ability of a team to accomplish existing tasks effectively (Gordon 78). In such a way, in this case, one can see essential flaws in this aspect as the level of commitment decreases.

Another factor touched upon in the case is motivation. It can be determined as people’s readiness to perform some actions or engage in various activities. It is usually associated with the generation of the particular benefit or satisfaction of a certain need, as all individuals have many motifs or cases for their actions. Speaking about organizations and teams, motivation also plays a critical role in their functioning as it guarantees high effectiveness and readiness to perform multiple tasks (Pinder 45). At the same time, there is a clear understanding that there is a certain complexity peculiar to this sphere and a set of factors that impact motivation. From the case, it becomes clear that Rohit is inspired by the opportunity to engage in new, challenging, and interesting activities that can help him to grow professionally and build a career. These factors can be considered facilitators of motivation; however, the team leaders’ lack of desire to cooperate with a team decreases its levels.

The motivation of a person also depends on his/her current needs. Cogitating this issue, Maslow offers a specific hierarchy outlining factors that should be considered.

In accordance with this model, every individual has five types of demands, which are physiological, safety, belongingness and love, esteem, self-actualization needs (McLeod). Every worker remains in his/her own state of personal development, which means that there are different types of demands he/she has at the moment. However, only satisfaction of hierarchically lower needs can help to achieve the next stage and remain motivated (McLeod). Applying this concept to the proposed situation and the question of motivation of leadership in general, it is possible to state that leaders’ main task is to watch that employees’ basic demands are met while there are also opportunities to satisfy needs for prestige, self-actualization, and career growth. Only under these conditions will workers demonstrate a high level of commitment and desire to perform their functions effectively.

Finally, the case also poses the question of climate or atmosphere within a collective as Rohit’s colleagues have a certain negative impact on his motivation and desire to work. Being sure that leadership style will not alter, they prefer to avoid creative solutions adhering to the recommendations of their leader. This factor deteriorates the atmosphere and contributes to the emergence of critical problems in the future.

What, according to you, were the reasons for Rohit’s disillusionment? Answer the question using Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

In such a way, utilizing this theoretical framework, it can be stated that there were several reasons for Rohit’s disillusionment. Accepting the fact that the primary motive for leaving the previous job was the desire to self-realize and build a more successful career, the absence of opportunities for self-realization can be considered the primary factor is limiting his motivation to work effectively. The utilization of the inappropriate leadership style by Aparna also contributes to the deterioration of the climate within a collective, which is also one of the factors that decrease Rohit’s desire to engage in new work and makes him think about the previous employer who provided workers with the chance to cooperate, discuss, and evolves by using creative approaches.

Applying the concept of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to the case, it is possible to state that Rohit has already fulfilled his basic demands, such as physiological and safety ones. The major reason for his transfer to other work was the desire to build a successful career or self-actualization and esteem demands (McLeod). The existence of opportunities to become a member of a team that creates new approaches together is an ideal motivator for Rohit. However, Aparna’s disregard of the team’s ideas and autocratic leadership style reduces motivation levels as there are no more chances to self-realize and grow professionally. For this reason, Rohit experiences some hardships and is not able to find other factors that can motivate him to work better.

What should Rohit do to resolve his situation? What can a team leader do to ensure high levels of motivation among his/her team members?

One of the possible ways to resolve the situation for Rohit is direct and open communication with his leader to share his problems and explain the negative impact of the selected leadership style on the whole collective. Trustful relations between all employees are the key to the achievement of positive results, which means that the initiation of the group discussion of the existing problems can help to make Aparna think about altering the current approach. To achieve high levels of motivation among group members, the leader should adhere to the transformational leadership style as it provides opportunities for all employees to engage in debates about topical problems and create an innovative solution that would contribute to the achievement of organizational goals (Gordon 123). A gradual increase in motivation levels should be one of Aparna’s major tasks.

Altogether, the given case proves the increased importance of motivation and leadership for the work of organizations. The absence of the opportunity to satisfy current needs might result in the reduction of employees’ desire to demonstrate high-performance levels or solve some tasks creatively. For this reason, it can be recommended to use flexible and inclusive approaches that can help to engage all workers in problem-solving activities and demonstrate to them the importance of their contribution to the further evolution of the company and it’s becoming a leader in the market. Utilization of this approach would help to achieve much better results and ensure that all members of the team will remain motivated to do their best. Additionally, leaders should correctly realize the peculiarities of their teams and monitor their states to be ready to introduce needed changes to avoid stagnation or deterioration of the climate within a collective.

Gordon, Jon. The Power of Positive Leadership: How and Why Positive Leaders Transform Teams and Organizations and Change the World . Wiley, 2017.

McLeod, Saul. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs,” Simply Psychology , 2018, Web.

Pinder, Craig. Work Motivation in Organizational Behavior . 2nd ed., Routledge, 2015.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, September 17). Employee Motivation: Theories in Practice. https://ivypanda.com/essays/employee-motivation-theories-in-practice/

"Employee Motivation: Theories in Practice." IvyPanda , 17 Sept. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/employee-motivation-theories-in-practice/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Employee Motivation: Theories in Practice'. 17 September.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Employee Motivation: Theories in Practice." September 17, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/employee-motivation-theories-in-practice/.

1. IvyPanda . "Employee Motivation: Theories in Practice." September 17, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/employee-motivation-theories-in-practice/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Employee Motivation: Theories in Practice." September 17, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/employee-motivation-theories-in-practice/.

- Collective Bargaining in Education

- The Impact of Motivation in the Workplace

- Collective Bargaining: Strategies and Trends

- Models of Electronic Learning in "ABCs of E-Learning" by Broadbent

- Selection Strategy in Recruitment of Animators

- Communication in a Manufacturing Environment

- Leadership Study: Managing Director Interview

- Effective Manager Qualities Review

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.6(9); 2020 Sep

The application of Herzberg's two-factor theory of motivation to job satisfaction in clinical laboratories in Omani hospitals

Samira alrawahi.

a Learning, Informatics, Management, and Ethics Department (LIME), Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

b Pathology Department, Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Muscat, Oman

Stina Fransson Sellgren

c Karolinska University Hospital, Affiliated to Learning, Informatics, Management, and Ethics Department (LIME), Medical Management Centre (MMC), Stockholm, Sweden

Salem Altouby

d College of Pharmacy and Nursing, University of Nizwa, Scientific Council for Nursing & Midwifery Specialties, Arab Board of Health Specialization, Cardiff University, UK

Nasar Alwahaibi

e Department of Allied Health Sciences, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman

Mats Brommels

f Department of Learning, Informatics, Management, and Ethics (LIME), Medical Management Centre (MMC), Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

Job satisfaction is an important condition for staff retention in most healthcare Organizations. As a concept, job satisfaction is linked to motivation theory. Herzberg's two factor theory of motivation is used in this study to explore what motivational elements are associated with job satisfaction among medical laboratory professionals (MLPs) in Oman.

A mixed-method approach was adopted, and focus group discussions (FGDs) were used for data collection. The FGDs were conducted in the main hospitals in Oman. Data were analyzed by directed content analysis, and frequencies of statements related to factors were calculated for a comparison with the Herzberg theory.

The following job dissatisfaction factors (hygiene) were identified: health and safety, heavy workload, salary, promotion, recognition and organizational policies. The satisfaction (motivators) were: relationships with co-workers, relationship with leaders, and professional development.

Conclusions

The job dissatisfaction reported was resulted from the absence of hygiene factors and some of the motivators in accordance with Hertzberg's theory. Hospital managers need to address these factors, defined by Hertzberg, in order to improve motivation and job satisfaction.

Psychology; Social science; Occupational psychology; Job satisfaction; Motivation; Herzberg; Medical laboratories.

1. Introduction

1.1. background.

The Sultanate of Oman has reached a level of distinction in its health sector, as the Ministry of Health (MOH) established a health system framework by enrolling large numbers of expatriate healthcare professionals and by introducing a referral system throughout its healthcare organizations. The Sultanate's healthcare system requires people management strategies that consider job satisfaction an important factor underpinning of growth, productivity, human resource development, and staff retention. Such strategies must be capable of assessing the satisfaction of any group through various indicators, such as the quality of the health service provided.

The MOH is the main health service provider in Oman (80%) and accounts for 6.3% of total government expenditures ( The Department of Health Information and Statistics, 2016 ).

The Royal Hospital, Khoula Hospital and Al Nahdha Hospital Each has specialty departments that operate as referral points for patients. Additionally, the hospitals provide tertiary and general acute care. The Royal and Khoula Hospitals enjoy maximum autonomy within the MOH, while the Al Nahdha Hospital is an autonomous hospital within the Directorate Office of the Muscat Governorate. Given the status of these hospitals, it is vital that they are staffed with individuals who are committed to their jobs; as a first step, these individuals must be satisfied with their jobs. Job satisfaction is the degree of positive affect that an employee feels towards the organization. It may be a general satisfaction with the job or with specific dimensions of the job or workplace, such as promotions, pay, and relationships with coworkers ( Blaauw et al., 2013 ).

Job satisfaction is described as being key in promoting feelings of fulfillment through promotions, recognition, salaries, and the achievement of goals ( Ausloos and Pekalski, 2007 ). George and Jones (2008) defined job satisfaction as a collection of feelings that people have towards their job. Specifically, with respect to health workers, job satisfaction is known to influence motivation, staff performance, and retention, which in turn affect the successful implementation of health system reform ( Wang et al., 2017 ). Motivation among workers requires an encouraging work environment, which does not happen by chance.

A productive environment can be generated by addressing the factors that influence employee job satisfaction and then designing interventions that can be implemented by managers to include and enhance those factors ( Munyewende et al., 2014 ). Unfortunately, in the health sector, there is poor job satisfaction caused by low income, poor working conditions, and limited opportunities for career development within healthcare organizations ( Hotchkiss et al., 2015 ). A recent study reported that 75.3% of health care workers were dissatisfied with their working environment, salary, promotion and benefits, whereas the relationships with leaders and co-workers were satisfaction factors ( Verma et al., 2019 ). In an earlier study pay, promotion, training and development, relations with supervisors, poor working conditions and organizational policies were the main factors for job dissatisfaction among health workers in eastern Ethiopia ( Geleto et al., 2015 ). Lack of professional development and training opportunities reported by 90% of medical laboratory professionals as the most important factor affecting their job satisfaction ( Marinucci et al., 2013 ). On the other hand, the relationships with leaders and peers contributed most to satisfaction, whereas the salary was a dissatisfaction factor ( Lu et al., 2016 ).

Given this scenario, the purpose of this study was to determine the factors that promote job satisfaction for MLPs and to consider MLPs' work motivation in terms of Herzberg's two-factor theory of motivation. This study is the first of its kind among this group of health professionals in Oman and contributes to developing an understanding of the factors involved in encouraging satisfaction and dissatisfaction in the medical laboratories of the three hospitals concerned. By paying due attention to differences in context, the findings may be generalized to other similar facilities.

1.2. Herzberg's two-factor theory of motivation

Most theories discuss job satisfaction within the context of motivation ( Kian et al., 2014 ). The Herzberg theory has been used as a method to explore job satisfaction among employees ( Lundberg et al., 2009 ) According to Herzberg's theory of motivation applied to the workplace, there are two types of motivating factors: 1) satisfiers (motivators), which are the main drivers of job satisfaction and include achievements, recognition, responsibility, and work advancement, and 2) dissatisfiers (hygiene factors), which are the main causes of job dissatisfaction ( Herzberg, 1966 ) and include factors such as working conditions, salaries, relationships with colleagues, administrative policies, and supervision. Herzberg used this model to explain that an individual at work can be satisfied and dissatisfied at the same time as these two sets of factors work in separate sequences. For example, hygiene factors (dissatisfiers) cannot increase or decrease satisfaction; they can affect only the degree of dissatisfaction. Satisfiers (motivational elements) need to be harmonized with hygiene factors to achieve job satisfaction at work. Managers in healthcare organizations should understand this relationship.

In Maslow's theory of motivation, the lower needs on the proposed pyramid must be met before the higher needs; this idea can be considered parallel to that of motivational and hygiene factors because hygiene factors must be present to allow motivational factors to emerge and thereby prevent job dissatisfaction ( Maslow, 1954 , Maslow, 1954 ). Hence, the motivators in Herzberg's theory are similar to the intrinsic factors (higher needs) in Maslow's theory. The extrinsic factors in Maslow's theory resemble the hygiene factors (dissatisfiers) in Herzberg's two-factor theory.

In 1975, Rogers summarized Herzberg's two-factor theory as follows: “In other words, adequate salary, good working conditions, respected supervisors and likeable co-workers will not produce a satisfied worker; they will only produce a worker who is not dissatisfied. However, their levels must be acceptable in order for the motivation factors to become operative. In other words, like medical hygiene practices, they cannot cure an illness, but they can aid in preventing it” ( Rogers, 1975 ).

1.3. Application of Herzberg's theory in different contexts

Herzberg's two-factor theory has been widely applied in studies on staff satisfaction, but mostly in other industries and for other occupational groups than health professionals. For example, Ruthankoon and Ogunlana tested Herzberg's two factor theory and concluded that different hygiene and motivation factors are applicable in different occupations in the Thai construction industry ( Ruthankoon and Olu Ogunlana, 2003 ). In the Pakistani context, these factors reported to be a strong moderator for job satisfaction among staff in insurance companies ( Rahman et al., 2017 ). Other examples include the hospitality industry ( Hsiao et al., 2016 ) and mobile data services (( Lee et al., 2009 ). We have not found comparable studies in health care, and all types of studies on job satisfaction in clinical laboratories are scarce.

In order to explore the views of medical laboratory professionals on their workplace and what factors had a positive or negative effect on their job satisfaction a series of focus group discussions (FGD) were performed. The advantage of a focus group compared to individual interviews is that the discussion among participants will help to clarify opinions, provoke more in-depth reasoning, and to disclose whether opinions are shared by many. Whilst a focus group discussion is a qualitative research approach, it also enables a semi-quantitative analysis of statements made. This study employs such a mixed-methods approach.

The FGDs were conducted from February to June 2017 at each of the three main MOH hospitals: the Royal, Al Nahdha and Khoula Hospitals.

2.1. Setting and participants

Medical laboratory professionals working in hematology, biochemistry, pathology, and microbiology laboratories including senior and junior staff from the three main hospitals participated in the FGDs: nine groups from the Royal Hospital, five groups from Khoula Hospital, and four groups from Al Nahdha Hospital. Each group had between six and eight participants ( Krueger and Casey, 2015 ).

To obtain this sample, the author sent a letter describing the purpose of the study to the supervisors of each laboratory and asking MLP volunteers. Anonymity (through the use of code names) and confidentiality were strictly observed in recognition of the need for good research ethics and the requirements of Omani and Swedish legislation, as well as to preserve personal integrity. A total of 101 medical laboratory professionals participated in the FGDs. The demography of the participants is exhibited in Appendix I, showing that the participants were representative of all laboratory staff in the three hospitals.

2.2. Focus group discussion (FGD) procedures

The FGDs were moderated by the first author with the support of an observer. The Focus Group discussions gave respondents freedom to express their feelings in order to obtain data representing the purpose of the study. The discussion was facilitated by the first author, following an interview guide, derived from Hertzberg's two factor theory. The FGD sessions lasted between 60 to 90 min. At the end of each discussion, the findings were summarized and shared with the participants (member checking), for validating the results and increasing the credibility of the study ( Birt et al., 2016 ).

2.3. Data analysis

The FGDs were recorded and stored on a USB stick accessible only by the first author. The recorded material was transcribed by the observer and checked against observational and summary notes made by the moderator immediately after each FGD. The transcriptions and additions from the notes were scrutinized by directed content analysis, guided by the Hertzberg two-factor theory. Meaning units expressing opinions of motivating and hygiene factors were identified and condensed into categories and further into themes. Eventually, “cut and paste technique” used manually with a poster and coloured pens ( Krueger, 1996 ). This process was done by the moderator and observer independently. Results were compared and consensus reached after discussions. For each theme, the opinions of FGD participants, were condensed into “statements” and their frequencies were calculated, following the example of Herzberg (1968) . This made it possible to compare the profile of motivating and hygiene factors of medical laboratory professionals with the original theory of Hertzberg.

2.4. Ethics approval and consent to participate

Personal integrity was guaranteed. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants after fully disclosing the purpose of the study. Data storage and handling complied with the requirements of Swedish legislation on research ethics and personal data. The study was approved by the Research and Ethical Review and Approval Committee of MOH in Oman NO: (MH/DGP/R&S/PROPOSAL, 2016).

The FGDs recorded the participant's opinions of the individual needs and other factors that affected their job satisfaction at work; these opinions were condensed into categories and from those eight major themes emerged. (See Table 1 ). The themes are presented together with illustrative citations from the FGDs.

Table 1

Categories and themes related to job satisfaction and job dissatisfaction among medical laboratory professionals at Royal, Khoula, and Al Nahdha Hospitals.

3.1. Laboratory health and safety

From participants’ perspective, the major dissatisfier in each of the three hospitals was a lack of health and safety in the laboratories. Poor ventilation and exposure to toxic chemicals were cited reasons in some departments, as well as the receipt of clinical samples without biohazard labels. The lack of biohazard labels was considered to be due to carelessness of some nurses, posing a risk to the laboratory workers.

“Some specimens are sent to the laboratory without a biohazard label, and only after processing will we know it is infectious, such as HIV” (FGD2, RH).

“We are having ventilation problems in the laboratory while processing specimens” (FGD3, NH).

“It is really not safe working in an infectious environment. I was exposed to a viral infection while processing a sample that had no biohazard sticker, and I was treated for three weeks” (FGD2, KH).

3.2. Professional status (recognition and appreciation)

The MLPs believed that there was no appreciation or recognition of their good performance even though they worked in a risky environment. They received no compensation for their commitment in the face of such risk, and felt that because they worked behind the scenes, clinicians were unaware of the time they spent processing samples or the hazards involved in their work.

“The clinicians shout at us if they need the results; in this hospital, the nurses are more recognized than we are” (FGD1, KH).

“We work behind the scenes, we are not appreciated, and we don't want to be called ‘laboratory technicians’. This name should be changed” (FGD2, RH).

“I feel undervalued in this hospital, and I dislike working in the laboratory” (FGD2, NH).

3.3. Heavy workload

FGDs participants identified workload as another dissatisfier, especially when colleagues took unplanned leave, which lead to the accumulation of samples for processing and for others to handle. In addition, the participants mentioned that the night shift workers were overloaded, irrespective of whether personnel were on leave, because samples referred from other hospitals during the day.

“The unplanned leave for staff causes shortages and heavy workload” (FGD2, RH).

“We are overloaded with a continuous flow of samples during the night shift” (FGD5, KH).

3.4. Professional development and training