Find anything you save across the site in your account

A Ukrainian Novel Looks Between the Lines of War

By Keith Gessen

The incremental Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014 —which began with the seizure of Crimea and continued as a hybrid operation, capitalizing on anti-Kyiv sentiment in eastern Ukraine and backed by an information war, mercenaries, and, ultimately, tanks and rockets—was eventually halted by Ukrainian forces, that summer, about fifty miles from the Russian border. A shaky ceasefire was signed in Minsk, and a so-called “line of contact” emerged. It ran for three hundred miles and separated Ukrainian government-controlled territory from the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. Along this line of contact, Ukrainian troops dug in on one side and Russian-backed troops on the other, with about nineteen miles between them. For more than seven years, with ebbs and flows in their frequency and intensity, the conflict featured sniper fire and shelling and even, toward the end, armed drones, which the Ukrainian government had procured from Turkey.

Andrey Kurkov’s novel “ Grey Bees ” (Deep Vellum) takes place in the area, known as the “gray zone,” between the two armed camps. Sergey Sergeyich is a retired mine-safety inspector turned beekeeper who is one of only two people left in the village of Little Starhorodivka. As Sergeyich recalls the beginning of the fighting, “Something broke in the country, in Kyiv, where nothing had ever been quite right. It broke so badly that painful cracks ran along the country, as if along a sheet of glass, and then blood began to seep through these cracks.”

The village cleared out slowly, then all at once.

The first shell hit the church, and the very next morning people began to leave Little Starhorodivka. First, fathers bundled their wives and children off to safety, wherever they had relatives: Russia, Odessa, Mykolayiv. Then the fathers themselves left, some becoming “separatists,” others refugees. The last to be taken away were the old men and women. They were dragged off weeping and cursing. The noise was awful. And then, one day, things grew so quiet that Sergeyich stepped out onto Lenin Street and was nearly deafened by the silence.

As it turned out, one other person, Pashka, an old schoolmate with whom Sergeyich had never been friendly, had also remained behind. When the book begins, it is 2017, and Sergeyich and Pashka have been alone in the village for almost three years. By Sergeyich’s account, they are keeping the village alive: “If every last person took off, no-one would return.” This way, perhaps, they would. Sergeyich’s house, on Lenin Street, looks out onto the Ukrainian lines, though he can’t quite see them; Pashka’s, on Shevchenko Street, is closer to the separatists. In ways congruent with this accident of geography, the two have slightly different sympathies.

[ Support The New Yorker’s award-winning journalism. Subscribe today » ]

The book, which was published in Ukraine four years ago, opens in a kind of stasis; the reader wonders whether it will be a twenty-first-century “Robinson Crusoe,” in which the two men try to outdo each other in their ability to survive without the comforts of civilization. But soon the gears of the plot start churning. Pashka shows up at Sergeyich’s house with a charged cell phone. How could Pashka possibly have charged it, Sergeyich wonders, when the electricity has been out for years? Pashka explains that the electricity came on in the middle of the night; Sergeyich must have slept through it. Impossible, Sergeyich says. He keeps all his light switches in the on position—the lights would have woken him. Pashka holds his ground. The mystery of the cell phone lingers.

Before long, Sergeyich also has a chance to charge his phone. He receives a surprise visit from a young Ukrainian soldier; because Sergeyich’s yard faces the Ukrainian lines, and because he is often working in it and tending to his bees, the Ukrainian soldier, who introduces himself as Petro, has been watching Sergeyich. They talk about the war and the state of things in Ukraine. Sergeyich has no access to television or the news, and the soldier tells him that people on TV are always arguing, that in the country at large place-names are being changed but otherwise everything is the same. As a gift to Sergeyich, he offers to charge his phone; in return he asks only that Sergeyich let him know if he ever needs help. When Sergeyich gets his phone back, he is left with the dilemma of whom to call.

Sergeyich is an eastern Ukrainian Everyman. He is supremely practical. In loving detail, Kurkov describes Sergeyich’s care for his bees, his nighttime preparations, his careful rationing of his limited provisions. Sergeyich has found himself in a war zone but does not think about politics. He wants nothing to do with the government, and doesn’t even bother to arrange for the delivery of his pension. Gradually, though, he is pulled into politics despite himself. He learns that Pashka has been hanging out with separatists and their Russian backers; Sergeyich disapproves. Meanwhile, his relationship with Petro deepens; when the Ukrainian lines are shelled, Sergeyich uses his cell phone to send the soldier a text. “Alive?” he asks him. “Alive,” Petro texts back. In an attempt to keep their small village up with the times, Sergeyich renames Pashka’s street Lenin, and his own Shevchenko. Pashka, who never liked living on a street named for the national poet of Ukraine, is delighted.

When the shelling becomes too much for Sergeyich’s bees (and maybe for Sergeyich), he decides to take them on a journey. The book becomes a kind of odyssey, with Sergeyich, driving his trusty old Lada, in the role of a Ukrainian Odysseus. First, he navigates various checkpoints and ends up in Ukraine proper. Then he sets up camp in a peaceful, wooded spot and lets his bees fly about and refresh themselves. He even meets a woman, a friendly and practical-minded shopkeeper named Galya, and begins to settle down.

The war follows him. People can tell from his license plate that he is from the Donetsk region, and they are suspicious of him. Eventually, he is forced to take his bees and leave. Recalling a friend he once met at a beekeepers’ convention, he decides to head for Crimea.

If, in the gray zone, people get along and help one another despite inhabiting a denuded, post-apocalyptic landscape, Crimea turns out to be the opposite. It is literally a land of honey—Sergeyich’s bees thrive there—but the threat of the state hangs over everything. Sergeyich’s friend, whom he had hoped to visit, is a Crimean Tatar, and through his family Sergeyich learns how the Russian occupiers—Crimea, as a border guard reminds him, is part of Russia now—deal with people they find inconvenient. They use violence, coercion, enticements. Sergeyich behaves honorably, but during every interaction with the authorities he experiences a kind of fear that he hadn’t known even in the gray zone: “It was a strange, almost inexplicable fear, in that it was purely physical, paralysing his facial muscles but giving rise to no thoughts whatsoever.” Sergeyich “tried to find words that might better explain his fear” of the powers that be, “and not just the powers that be, but the Russian powers that be”—but he finds it impossible. It is an “inarticulate fear,” “a skin-freezing fear.” In the end, Sergeyich escapes their clutches, but only barely, and not totally intact. The Russian security service confiscates one of his beehives, for “inspection,” and returns the bees in an altered state. They seem sickly to Sergeyich, and gray—hence the book’s title—and the healthy bees kick them out of their hives.

“Grey Bees,” although grounded deeply in the disturbing reality of war, sometimes has the feeling of a fable. When it was published, it joined a small shelf of books about the war by Ukrainian writers such as Artem Chapeye, Yevgenia Belorusets, Serhiy Zhadan, and Artem Chekh. “Grey Bees” is a gentle, sometimes ambivalent book about a conflict that had its share of moral complexity. Reading about it now, one feels transported to a more innocent time. Place-names that in “Grey Bees” connote safety and freedom—the port city of Mykolaiv, or the town of Vesele, near where Sergeyich meets Galya—are now under Russian attack or even Russian occupation. The subtle gradations relating to conversations about citizenship and belonging also seem the product of an earlier time. Sergeyich, when he first meets the soldier Petro, has an exchange with him about names. Petro is the Ukrainian version of Peter, and Sergeyich asks if Peter is the soldier’s real name. The soldier says no, Petro is his name:

“Says so in my passport.” “Well, my passport says I’m Serhiy Serhiyovych—but I say I’m Sergey Sergeyich. That’s the difference.” “You probably don’t agree with your passport,” Petro said. “No, I agree with my passport, just not with what it chooses to call me.” “Well, I agree both with my passport and with what it chooses to call me,” the guest said with a smile. It was an easy smile, even disarming—although a rifle hung on the back of his chair.

Petro is entirely at home in Ukraine, whereas Sergeyich, while accepting that he is a Ukrainian citizen, wants to retain his Russian-language identity: Sergey, rather than Serhiy.

This is also, as it happens, Kurkov’s dilemma as an author. Kurkov is a Ukrainian novelist who was born in St. Petersburg, grew up in Kyiv, and writes his fiction in Russian, at a time when Ukrainian-language literature is enjoying a post-Soviet renaissance. He is the president of the Ukrainian branch of PEN and a frequent commentator on Ukraine in the international media, and he has spoken in favor of a multilingual or hybrid identity for Ukraine. But he has also been sensitive to the unavoidable valences of Russian in times of trouble. Russian is “the language of the aggressor,” he said, back in 2014, and returning to the question more recently, in this magazine , he wrote that, for the moment, it didn’t matter what compelling arguments you could make for the Russian language—that many of Ukraine’s defenders spoke it; that countless other people dying and fighting and fleeing from the east of the country spoke it; that Vladimir Putin could not lay sole claim to it—because such arguments were beside the point. Hybrid identity was fine during times of hybrid war; when the missiles started flying, everyone became simply Ukrainian.

War resolves old questions and raises new ones. But mostly it destroys—lives, homes, memories, families. A cult of war can take root only in a place that has forgotten what war is, or maybe never knew in the first place. Ukrainian historians will tell you that, as much as Russia suffered during the German onslaught of the Second World War—in Leningrad, Smolensk, Stalingrad—Ukraine suffered, proportionally, even more. And now, once again, Ukraine is in flames. Nobody can say whether, at the end of this conflagration, Ukraine will regain control of its territory, or whether a new gray zone will be formed. In the Donbas, at least, where Russia has begun a new, large-scale offensive, there is not a lot of basis for optimism.

There is a touching moment in “Grey Bees” when Sergeyich and his bees have settled temporarily in the Ukrainian heartland. Galya, the shopkeeper, comes to their campsite three evenings in a row with food she has prepared for Sergeyich. On the third night, she says that the next day she will be unable to come. Sergeyich assumes she is busy, but it turns out she cannot bring the food because the dish she is preparing is borscht. He will need to come to her place to eat it. Sergeyich agrees.

The eating of the borscht, in Boris Dralyuk’s deft translation, is described with immense pleasure:

Galya’s borscht slayed Sergeyich. There were dried porcini mushrooms swimming in it, and beans, and pieces of veal. He ate it steadily, unhurriedly, occasionally gazing up at her; this was, after all, the first time they had dined together—not like their evenings by the fire, when she had fed him without eating herself. There was a bottle of shop-bought vodka on the table, to accompany the meal. Sergeyich and Galya drank without toasting, half a shot glass at a sip. Galya had also peeled several cloves of garlic, which lay on a saucer beside the bottle and a dish of salt. They ate these cloves in turn—first he would take one, dip it in the salt and place it in his mouth, then she. No conversation arose; there was no need for talk. After the third bowl, Sergeyich realised he had had enough, although, at the same time, he felt he could have overcome a fourth.

It is a scene of total contentment. But this is not a contented book. Bees make honey and a pleasant buzzing sound, yet they can also sting. Sergeyich must soon flee from this refuge, as he must from the next. Finally, he returns to his village, to his home, because someone needs to keep the place going, just in case the war ends, and people decide to come back. ♦

New Yorker Favorites

The day the dinosaurs died .

What if you started itching— and couldn’t stop ?

How a notorious gangster was exposed by his own sister .

Woodstock was overrated .

Diana Nyad’s hundred-and-eleven-mile swim .

Photo Booth: Deana Lawson’s hyper-staged portraits of Black love .

Fiction by Roald Dahl: “The Landlady”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

Books & Fiction

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Michael Schulman

By Jennifer Wilson

By Joyce Carol Oates

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

May 23, 2024

Current Issue

UCLA: Whose Violence?

For two days, UCLA’s pro-Palestine encampment was a site of violent aggression—committed not by the students but against them.

May 11, 2024

Big Germany, What Now?

The post-Wall era is over and everyone, including the Germans, is asking which way Germany—the most powerful country in the European Union—will go.

May 23, 2024 issue

A View from Cairo

The Egyptian government’s repression of its citizens and the Israeli government’s occupation of Palestine are inextricably linked.

May 12, 2024

Inside Uber’s Political Machine

By spending vast sums on political lobbying, Uber has mounted a multi-pronged assault on the regulatory state.

May 9, 2024

Transatlantic Flights

The collected poems of Denise Levertov and Anne Stevenson suggest what a poet can gain by expatriation, in both directions between England and the United States.

Nathan Thrall

Read the article that grew into the book of the same name, this year’s winner of the Pulitzer Prize in General Nonfiction

How Bondage Built the Church

Rachel Swarns’s recent book about a mass sale of enslaved people by Jesuit priests to save Georgetown University reminds us that the legacy of slavery is simultaneously the legacy of resistance.

‘Give Me Joy’

Madonna’s genius is not just for controversy, or for pressing on the fissures in femininity, or for her bold support of once-unpopular causes. It is for doing it all with no apology.

The Whistleblower We Deserve

The ambiguous hero of Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People is a man of science who insists on the primacy of truth and evidence. But he’s also, possibly, a bit of a fascist.

The Woman in the Well

In Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes, a dissatisfied Italian everywoman starts keeping a diary, and eventually her own thoughts become too much to bear.

Triumphs of Skepticism

Hilary Mantel wrote in favor of the doubting, the irreverent, and even the fickle against conservatism, nostalgia, and sentiment.

Perpetual Expectation

The Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s operas have a pervasive aura of waiting for something just out of sight, shrouded in veil upon veil.

Ecstasy’s Odyssey

When the creator of MDMA first experimented with the drug, he felt a mellow sensation that he compared to “a low-calorie martini.”

‘A Long-Tongue Saga’

Over the course of more than a thousand pages, Leon Forrest’s novel Divine Days , reissued after three decades, elicits from the reader every emotion from awe to exasperation.

“Roughly half of the world’s tax havens are directly linked to the UK and responsible for a good share of the estimated $8.7 trillion held offshore. Seeing postwar history through the tax haven helps us understand how empire ended but so little changed.”

Jill Biden is a barrier-breaking national figure. What are we to make of the wholesome, at times bland story she tells about herself?

Choosing Pragmatism Over Textualism

A method of judicial interpretation that looks only to the original meaning of legal texts risks producing a Constitution and laws that no one would want.

Supersize That?

New supertall skyscrapers planned for Manhattan will reduce the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building to the scale of souvenir tchotchkes. With the current glut of unoccupied office space, they may be the last of their kind.

Thoughtfully chosen gifts for readers and writers

Death and Detention on the Texas Border

As Joe Biden and Greg Abbott escalate their standoff over border enforcement, migrants find themselves caught in the middle.

May 5, 2024

More Real Than Life

In Jane Schoenbrun’s films, personal metamorphosis happens on both sides of the screen.

May 4, 2024

The Immunity Con

For the first time in American history, the supreme judicial authority is parsing how much criminality to permit the chief executive.

May 1, 2024

Haiti on the Precipice

The chaos and violence in Haiti today result from years of political interference from abroad and democratic decay at home.

April 27, 2024

Translation Without Angels

Self-Portrait of the US as Conjoined Twins

Voicemail from the Impaled

May 9, 2024 issue

Free from the Archives

“The more militarized we allow law enforcement agents to become, the more likely officers are to use lethal violence against citizens: civilian deaths have been found to increase by about 130 percent when police forces acquire significantly more military equipment.”

The First and Last of Her Kind

The legal academy has tended to be dismissive of Sandra Day O’Connor, arguing that she had no overarching theory of constitutional interpretation. But the Supreme Court is not a law school faculty workshop. She saw herself as a problem-solver.

November 7, 2019 issue

Hail to the Chief

“John Marshall, while hugely instrumental in assuring for the federal judiciary its limited supervisory role over the legislative branch, exhibited a subservience to the executive branch that continues to haunt us.”

November 22, 2018 issue

Law Without History?

How Justice Scalia’s understanding of the Constitution is wrong

October 23, 2014 issue

Bad Man from Olympus

Oliver Wendell Holmes argued that law should be conceived as a means to the attainment of human ends, and that judges should admit that they decide debatable cases on the basis of policy, not of precedent or abstract principle.

July 13, 1995 issue

How to Understand the Dreyfus Affair

“The Dreyfus Affair demonstrates the fragility of reason, of the rights of man, and indeed of civilized values when a nation feels itself under threat from an external or internal enemy.”

June 10, 2010 issue

Holy Hysteria

“From January until October 1898 a convulsion of anti-Semitism ran through France; no major population center was spared, whether there were Jews living in it or not. There were demonstrations and riots, attacks on synagogues and shops; ‘patriots’ encouraged hotelkeepers to evict Jews from their rooms.”

April 10, 2003 issue

The Lesson of the Dreyfus Case

“Another book about the Dreyfus Affair? What could possibly justify loading another volume upon that already over-crowded shelf? The simplest answer is the timelessness of the story. It is a morality tale.”

February 27, 1986 issue

No End to the Affair

“French politics after 1900 were not the same as before. Perhaps even without the Affair, the new forces—socialists demanding reform, syndicalists calling for direct action, a new right-wing anti-democratic nationalism represented by the Action Française, a renewed movement among the Radicals for the final separation of the Roman Church from the French State—these would have begun to make themselves felt; but there seems little doubt that the Dreyfus experience accelerated these developments.”

May 18, 1967 issue

In Harvard Yard

Civil discourse and critical inquiry are not abstract concepts in the encampment. They are active principles.

May 8, 2024

Migrant Workers in Their Own Land

After closing its borders to Palestinians employed in critical sectors, Israel’s government has faced a labor shortage—which is being met by Indian migrant workers.

April 21, 2024

In Gaza’s Hospitals

It’s not easy to work under continuous military attack, to wake up and close your eyes to injuries and corpses, to feel helpless to stop it all.

April 19, 2024

The Road to Famine in Gaza

Hundreds of thousands of people in Gaza are at the brink of famine—a human-made disaster with roots in Israel’s history of using food as a weapon.

March 30, 2024

Anti-Rent Wars, Then and Now

Amid the 1840s economic crisis, landlords tried to drive out tenants in default. The remarkable movement that rose to challenge evictions can be a model for today’s housing activists.

October 25, 2021

Tenants Under Siege: Inside New York City’s Housing Crisis

New York City is in the throes of a humanitarian emergency. The tide of homelessness is only the most visible symptom.

August 17, 2017 issue

Kicked Out in America!

“It is odd that the shortage of low-income housing gets little attention, even among experts on the left. Decent affordable shelter is a primal human need, and its disappearance is one of the most troubling results of growing inequality.”

March 10, 2016 issue

The Rise of the Homeless

“Three years into Ronald Reagan’s first administration, the effects of his social welfare policies—from the elimination of certain nutrition and health programs to the drastic cuts in federal subsidies for the construction of low-income housing—were just being felt in the cities.”

February 16, 1989 issue

Reading, Reading, Reading

“My gold standard for a novel is whether it’s doing something that only a novel can do, or that a novel can do best.”

Dancing on the Page

“How do I capture what happened—and what moved me—during a performance that most of my readers will never have a chance to see?”

Storm Over Columbia

“The only reason we didn’t descend into violence that day was that the students remained calm. They were the only adults in the room.”

A Curious Temperament

“I don’t have any programmatic agenda for art, merely a hope to cut through received patterns of thought.”

April 20, 2024

Into the Cave

Episode Six of “The Critic and Her Publics”

April 9, 2024

A Gender Emergency

Episode Five of “The Critic and Her Publics”

March 26, 2024

The Channeler

Episode Four of “The Critic and Her Publics”

March 12, 2024

‘I Am the Cabbage Writer’

Episode Three of “The Critic and Her Publics”

February 27, 2024

The latest releases from New York Review Books

Loved and Missed

Robert Glück

Pier Paolo Pasolini

An Ordinary Youth

Walter Kempowski

Amelia Rosselli

Poor Helpless Comics!

Ed Subitzky

Safe Havens

Subscribe and save 50%!

Read the latest issue as soon as it’s available, and browse our rich archives. You'll have immediate subscriber-only access to over 1,200 issues and 25,000 articles published since 1963.

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

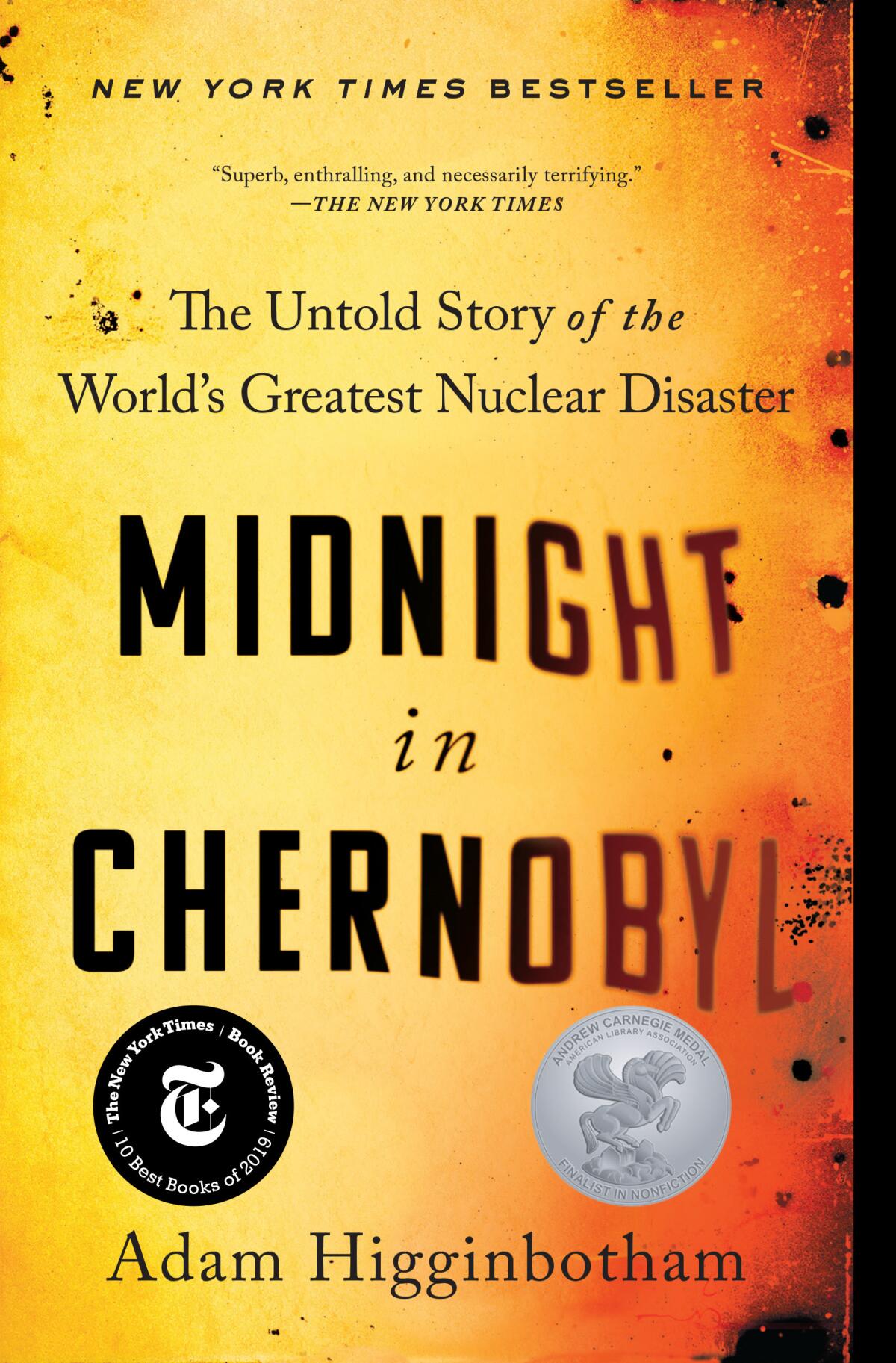

12 essential books on Ukraine, Russia and Putin

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

On the Shelf

A Ukraine invasion reading list

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

If you are an American reader horrified by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine , reaching for a book to explain it all seems like the logical next step. Independent bookstores confirm that logic, reporting a run on titles about Ukraine and Russia. And in the two major library systems I patronize, every title on Ukraine, Russia and Putin I have sought in the last week is checked out, with a lengthy wait for both print and ebook versions. Publishing has yet to offer new books on the Ukraine-Russia struggle, though that is sure to change.

Fortunately, there’s a wealth of recently published, deeply informed titles on the intertwined history of these nations. All you have to do is find them. Here are some of the most noteworthy:

The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine By Serheii Plokhy Basic Books: 448 pages, $20

This readable, detailed and authoritative study by a Harvard professor of Ukrainian history, issued in a revised paperback edition in 2021, is an essential aid in understanding Ukraine’s rich and complicated past. Plokhy covers 2,000 years of Ukrainian history as waves of invaders fought and died grasping for the region’s strategic advantages and natural riches. Those claimants include the Kyivan Rus’ (Vikings that both Ukrainians and Russians reference as ancestors), the Byzantine Empire, the Ottomans, the Mongols, Poles and Lithuanians, Russian tsars, Germans, the Soviet Union and now Vladimir Putin’s Russia. The author expertly analyzes the religious conflicts, nationalism and antisemitism that have shaped and stained the country’s past. And he vividly conveys Ukrainians’ toughness, courage and ruthlessness — by now it must be embedded in their genes — and their long fight to obtain independence from Russia.

Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine By Anne Applebaum Anchor: 608 pages, $18

The winner of the Pulitzer Prize for “Gulag: A History,” Applebaum has deep connections to middle Europe; she lives in Poland, Ukraine’s near neighbor, and is married to a Polish politician. This 2017 book tells the horrific story of Ukraine’s treatment at the hands of Stalin in the 1930s, when the dictator drove its peasants off their farms and into collectives. The result was a catastrophic famine, the most lethal in European history, in which 3 million Ukrainians died.

Everything Flows By Vasily Grossman New York Review Books: 272 pages, $18

Grossman was an acclaimed journalist and novelist who ran afoul of Stalin’s regime. His last novel features characters who step forward to confess the terrible things they did under Stalin, things that seemed rational under the circumstances. One woman’s account re-creates the Ukrainian famine in horrifying detail, making it clear that Stalin’s actions constitute a deliberate and successful genocide.

These books kill tyrants: Azar Nafisi on Putin and how to ‘Read Dangerously’

The author of “Reading Lolita in Tehran” talks about her far-ranging new book, “Read Dangerously,” about the power of books to fight authoritarians.

March 8, 2022

Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin By Timothy Snyder Basic Books: 560 pages, $23

Snyder, a Yale history professor, has published six books that touch on Ukraine and Russia (the latest is 2019’s “ The Road to Unfreedom ”). His 2010 prizewinning history, “Bloodlands,” reexamines the mass killings perpetrated by both Hitler and Stalin in middle Europe between 1930 and 1945, when as many as 14 million noncombatants perished through murder, starvation and imprisonment in death camps — many of them Ukrainians.

Midnight in Chernobyl By Adam Higginbotham Simon & Schuster: 560 pages, $20

As Russia and Ukraine fight in the vicinity of Ukraine’s four nuclear plants, books on Chernobyl have a new sense of urgency. Higginbotham’s critically acclaimed 2019 account of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster reconstructs events on a nearly minute-by-minute timeline.

Voices From Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster By Svetlana Alexievich Dalkey Archive: 240 pages, $20

The Belarusian journalist, genius oral historian and winner of the 2015 Nobel Prize recounts the story of the Chernobyl disaster in kaleidoscopic retrospect via almost 500 interviews with those who lived through it.

In Wartime: Voices From Ukraine By Tim Judah Tim Duggan Books: 290 pages, $12 (Kindle)

This excellent 2015 book by the Economist’s Balkans correspondent ( currently reporting from Kiev ) moves forward from Russia’s 2014 invasion and annexation of Crimea through the Ukrainian civil war that followed to try to understand the history that motivates all sides, including Russians in eastern Ukraine who see Putin as a savior and western Ukrainians determined to fight the Russians at all costs. In Ukraine, “what you believe today depends on what you believe about the past,” writes Judah. A prescient book that combines vivid profiles of Ukrainians with lucid history and on-the-ground journalism.

How photojournalists struggle to capture COVID, Black Lives Matter — and now Ukraine

Photojournalism scholar Lauren Walsh discusses her new book, ‘Through the Lens,’ and the challenges of photographing conflicts ranging from BLM to Ukraine.

Feb. 25, 2022

PUTIN’S RUSSIA

The Man Without a Face By Masha Gessen Riverhead: 352 pages, $18

One of the most astonishing things about this book is that the steel-nerved journalist , now a New Yorker writer, was still living in Russia when it was published in 2012. Gessen digs into Putin’s working-class childhood, his career as a KGB agent, his schooling in politics as a St. Petersburg government official and, after his rise to ruler of Russia, his systematic construction of an authoritarian system that held sway over government, business and the media, harassing, imprisoning and even murdering those who stood in his way.

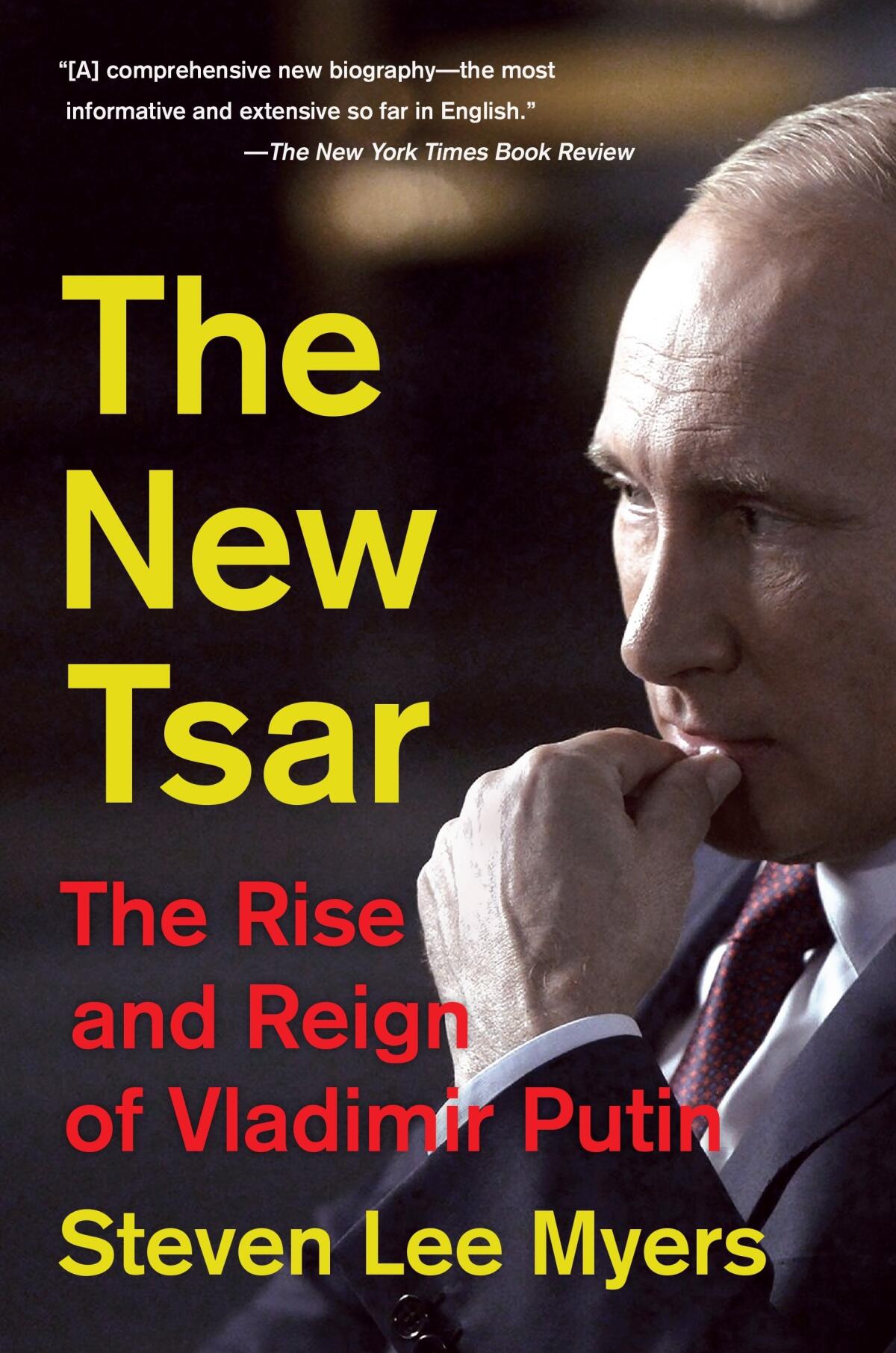

The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin By Steven Lee Myers Vintage: 592 pages, $19

Myers, former Moscow bureau chief for the New York Times, published this meticulously reported and researched biography in 2015. His premise is that what drives Putin is the need for control, which is why the messy processes of democracy threaten and enrage him. The book ends with Russia’s 2014 invasion of the Crimea, a first step in Putin’s drive to eventually reclaim Ukraine.

Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin By Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy Brookings: 543 pages, $34

An expert on Russia who served on the National Security Council during the Trump administration (and famously testified during his first impeachment trial), Hill co-authored this chilling psychological portrait of Putin as an extortionist, exploiter and manipulator who demands absolute loyalty and trusts only himself.

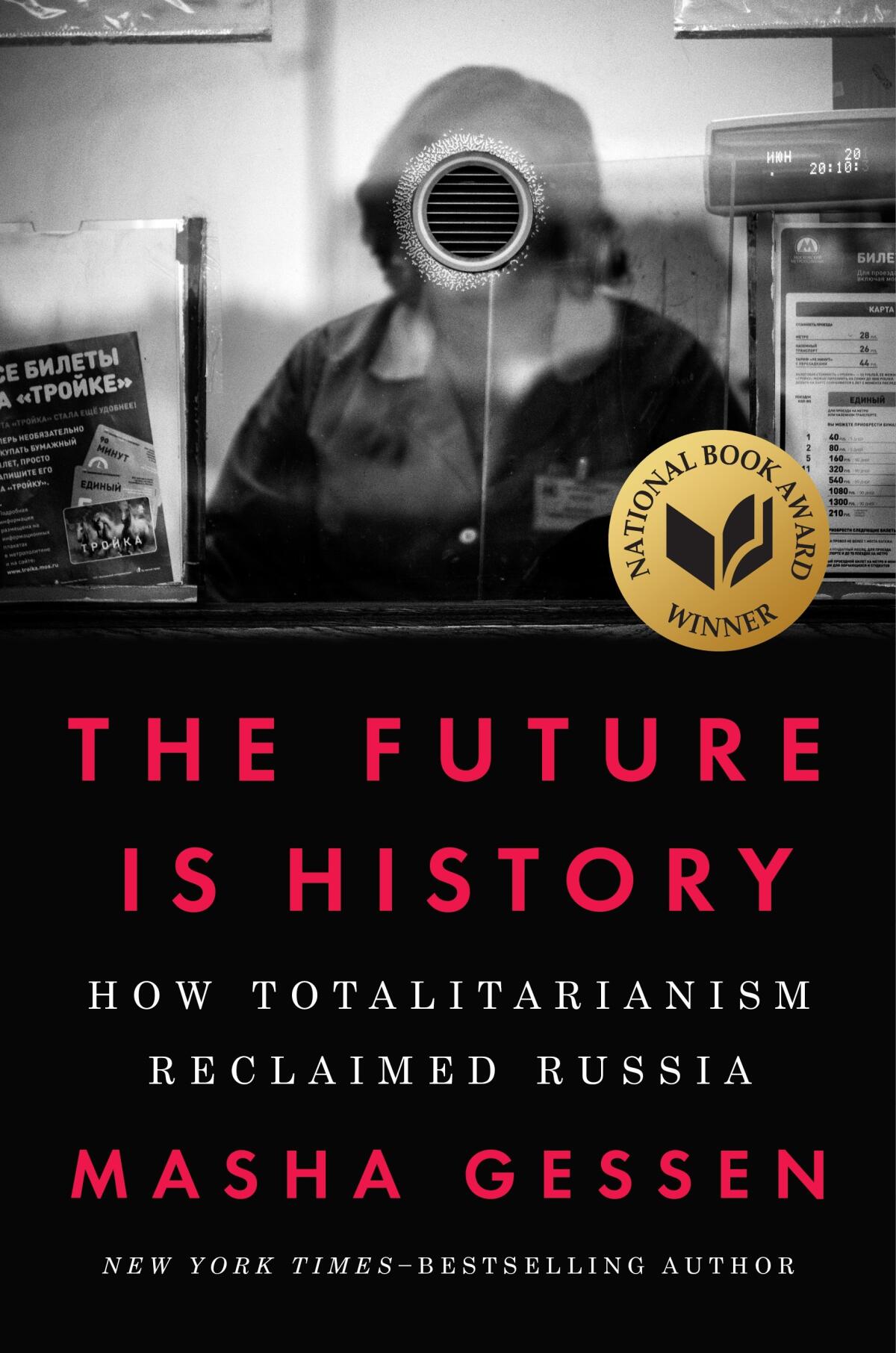

The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia By Masha Gessen Riverhead: 544 pages, $18

Gessen left Russia in 2013 because of its repression of gay families and critical journalists. In this brilliant and sobering account, published in 2017, the author follows four young Russians who spent most of their lives under Putin as he dismantled governing institutions essential to a free and just society, seized control of major businesses, suppressed the independent press and consolidated his wealth and his power. Written with insight and mordant humor, it’s a bleak and frightening portrait of a country in thrall to a ruthless dictator.

Patt Morrison Asks: Vladimir Putin biographer Masha Gessen on Russia, Trump and WikiLeaks

Russia flies a different flag now, but its song remains the same — the tune of the Russian Federation anthem is the old Soviet Union’s, unchanged.

Aug. 3, 2016

Between Two Fires: Truth, Ambition, and Compromise in Putin’s Russia By Joshua Yaffa Crown: 384 pages, $17

This unsettling 2021 book by a Moscow correspondent for the New Yorker gathers profiles of Russians who have ceded some of their ethics and freedoms to Putin. Foremost is Konstantin Ernst, a brilliant TV producer and intellectual who transformed and burnished Putin’s video image, attending high-level Kremlin meetings while running a national news channel broadcasting pro-Putin news and entertainment with a nostalgic view of Russia’s Stalinist past. In these portraits of talented people whose ambitions are warped by Putin’s will, there’s little to suggest any public uprising against Putin because of the war, though that could change as Russia’s elites lose the Western privileges that have become staples of their lives.

More to Read

Op-Comic: The Ukraine war enters its third year

Feb. 24, 2024

Opinion: Ukrainians will fight Russia no matter what. But this is what they need to win

Dec. 27, 2023

This Russian exile fights Putin’s imperialism. If you don’t want to hear from him, he gets it

July 25, 2023

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

System of a Down singer Serj Tankian’s new book details band’s up and downs, and what fuels his activism

May 9, 2024

‘Fallout’ is fun, but the reality of a post-nuclear apocalypse is nightmare fuel

Gavin Newsom is writing a book. Is he hoping to take a page from Obama?

The week’s bestselling books, May 12

May 8, 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Ukraine invasion — explained

The roots of Russia's invasion of Ukraine go back decades and run deep. The current conflict is more than one country fighting to take over another; it is — in the words of one U.S. official — a shift in "the world order." Here are some helpful stories to make sense of it all.

10 books to read about Ukraine

Rina Torchinsky

At Kramers, an independent bookstore in Washington, D.C., a lot of books about Russia and Ukraine are sold out. The books started going off the shelves a little more than a week ago as the world braced for a Russian invasion of Ukraine, general manager Llalan Fowler said.

"People have definitely been picking up the Russian books more, like Putin's People and that sort of title," she told NPR. "A lot of the books that are available to us about Ukraine and Russia and their relationship and their history are out of stock already at our supplier."

Many customers come into the shop knowing what they want, she said. But if you're not sure what to reach for first, here's a roundup of books about Ukraine that you might want to dive into.

I Will Die in a Foreign Land , by Kalani Pickhart

Pickhart's debut novel is on Fowler's to-read list. Named among the New York Public Library's best books of 2021 , I Will Die in a Foreign Land chronicles what Ukrainian protests looked like in 2013 and 2014, as demonstrators pushed for closer ties with NATO and the European Union.

Pickhart told KJZZ 's "The Show" last month that the book has garnered more attention as tensions grew between Russia and Ukraine.

"I think a lot of folks are looking for more information and to sort of understand the conflict in a way that's sort of digestible, essentially just trying to get a sense of the emotional movement of what's going on," Pickhart said.

Lucky Breaks , by Yevgenia Belorusets

A fiction book on Fowler's list, Lucky Breaks , translated from Russian by Eugene Ostashevsky, is a collection of short stories about women living in the aftermath of war in Ukraine. Belorusets, a Ukrainian writer, centers on ordinary lives — a florist, a cosmetologist, a card player, among others.

Hip Hop Ukraine: Music, Race, and African Migration, by Adriana Helbig

Helbig, who chairs the University of Pittsburgh's music department , saw African musicians rapping in Ukrainian during the Orange Revolution in 2004. The revolution followed a presidential election, which many claimed to be corrupt and fraudulent.

Through ethnographic research of music, media and policy, Helbig's book delves into the world of urban music, hip hop parties and dance competitions, along with interracial encounters among African immigrants and the local population.

Jews and Ukrainians in Russia's Literary Borderlands: From the Shtetl Fair to the Petersburg Bookshop , by Amelia Glaser

This book, which covers much of the 19th century and part of the 20th century in Ukraine, explores how those working and writing in Russian, Ukrainian and Yiddish communicated and collaborated at places like commercial markets and fairs. Glaser's study seeks to show that Eastern European literature was much more than just a single language and culture.

Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine, by Anne Applebaum

This book delves into the famine in Ukraine created by Joseph Stalin in the early 1930s, as he sought to destroy the Ukrainian national movement. Nearly 4 million Ukrainians died and many were arrested by Soviet secret police.

On NPR's Fresh Air , Applebaum, a historian and journalist writing about the war in Ukraine for The Atlantic, explained how Vladimir Putin and Stalin saw Ukraine similarly: "as a vector for ideas that could undermine him or threaten him."

Midnight in Chernobyl, by Adam Higginbotham

Higginbotham, a journalist, spent years investigating the aftermath of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. In his book, he digs into the design flaws and Soviet secrecy that contributed to the explosion, as well as the efforts to contain the damage. He spoke to Fresh Air about the novel in 2019.

Death and the Penguin, by Andrey Kurkov Random House UK hide caption

Death and the Penguin, by Andrey Kurkov

Set in Kyiv, this 1966 novel tells the story of Viktor, a man who dreams of becoming a novelist, and his pet penguin, Misha.

Viktor finds a job writing obituaries for people who haven't died yet, but his obits seem to become somewhat of a hit list — the people he writes about start to get murdered. Kurkov spoke to Fresh Air about the book in 2012.

Borderland: A Journey Through the History of Ukraine, by Anna Reid Basic Books hide caption

Borderland: A Journey Through the History of Ukraine, by Anna Reid

Reid's book takes readers back centuries , including the Mongol invasion in 1240 and the Nazi occupation in the 1900s, leading up to the country's independence in 1991 when the Soviet Union fell. The book chronicles Reid's own experiences as a reporter in Kyiv, as well as the voices of peasants, politicians and the survivors of Stalin's famine and Nazi labor camps.

The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine, by Serhii Plokhy

In this 2015 book, Plokhy explores Ukraine's ongoing search for identity and independence. Because the region serves as a strategic connector between the East and West, many groups have historically fought for supremacy on this piece of land, including the Romans, Ottomans, Third Reich and Soviet Union. Plokhy uses these historic conflicts to draw insights on ongoing conflicts and the quest for Ukrainian sovereignty.

Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel, by A. Anatoli (Kuznetsov) Farrar, Straus and Giroux hide caption

Babi Yar: A Document in the Form of a Novel, by A. Anatoli (Kuznetsov)

When the Germans occupied Kyiv in 1941, Kuznetsov was a 12-year-old living in Ukraine's capital city. The teenager witnessed the Nazi war crimes committed against Jews, Roma, Ukrainian nationalists and Soviet prisoners of war. He started documenting what he saw when he was 14, later supplementing his writings with eyewitness and survivor testimonies.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Russo-Ukrainian War by Serhii Plokhy review – the first draft of history

An impressive account of the origins and early stages of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine

A t the time of writing this review, we still await the big Ukrainian counter-offensive. On its success or failure will depend the future course of the war. In February, when the detailed planning for the Big Push was already starting, President Volodymyr Zelenskiy told me how nervous he was about it. Such frankness is typical of him. A charming, natural-seeming former actor, he has brought his professional abilities to the job of representing Ukraine at the highest level: providing the roar, he says, channelling Winston Churchill.

We know that the United States believes Ukraine’s counter-offensive won’t ultimately succeed, because we’ve seen the leaked documents that say so. But, of course, on the morning of 24 February 2022, Washington was sure the Russians would capture Kyiv within days – as were the Russians themselves. Zelenskiy’s decision to stay put, against American advice, was one of the main reasons Ukraine has proved so successful. So, as historian Serhii Plokhy shows in this sober, thoughtful, honest account of the war up to now, was the courage and grit of the 300 Ukrainian soldiers guarding Hostomel Airport outside Kyiv, who shot down several Russian helicopters and ensured that even when the others landed they didn’t have control of the skies.

Basically, though, the Russians defeated themselves, with their shocking incompetence. Some of the tanks destroyed on the approaches to Kyiv contained parade uniforms for the expected victory celebrations, and the invaders brought no more than three days’ worth of food with them. Russian military intelligence had lined up various senior Ukrainians to take control in Kyiv; but when they saw Russia’s failure at Hostomel they backed down abruptly. That morning the Kremlin’s press department had put out a statement talking about the imminent overthrow of “the band of drug addicts and neo-Nazis” that had “taken the whole Ukrainian people hostage”. By the afternoon, when the inhabitants of Kyiv failed to welcome their liberators as Putin had been told to expect, that approach wasn’t looking so good.

Ukraine’s army has done well for three main reasons. Its morale has been sky high. The weaponry that Nato has supplied is mostly a lot better than Russia’s. (To that extent, the Kremlin’s self-pitying claims of being at war with Nato are correct.) The third reason is the remarkable transformation in the military doctrine of the Ukrainian forces. When a high-powered Nato military team visited Kyiv before Russia’s takeover of Crimea in 2014, it found that the Ukrainian army was much like the Russian one, and the Soviet army before them: rather than take a decision and risk punishment, junior officers would pass the buck to their seniors, and the seniors would refer upwards to Moscow. The Nato team taught the Ukrainians that any decision, even a wrong one, was better than no decision at all, and that, cowardice or treachery excepted, there should be no punishment for orders that turned out to be wrong. Liberated by this, the Ukrainian forces have made the Russians look sclerotic and antiquated. Whatever happens now, Putin has demonstrated Russia’s incompetence for the whole world to see.

This book is appearing far too soon to be a definitive account of the war, of course. Plokhy, a Harvard professor of Ukrainian background and the author of the magnificent Chernobyl: History of a Tragedy , says himself that it arose from the “shock, pain, frustration, and anger” caused by the invasion; yet it is a fine, scholarly, unemotional chronicling of the war’s origins and early stages. It comes alive when it uses diaries and testimony from people in places like Bucha, outside Kyiv, where 1,650 were killed, nearly half of them shot at point-blank range, sometimes after unspeakable torture. Yet Plokhy keeps his academic distance. There is no ranting.

Did the US promise Russia it wouldn’t expand Nato beyond the borders of East Germany? If some members of the George HW Bush administration did say this, it was entirely unofficial: no such promises were made public. Should Nato have expanded to take in so much of Russia’s former empire? “You have no idea how desperate the Baltic states, Poland, the Czechs, the Romanians and the others are to join,” a senior Nato diplomat told me at the time. “They’re yelling at us that we’ve got to protect them in case Russia comes calling.” The invasion of Ukraine shows how right they were; Putin’s assurances have turned out to be utterly meaningless. In March 2014, after capturing Crimea in contravention of two international treaties, he promised not to take any more Ukrainian territory. By February 2022 he was calling the whole of Ukraine “historically Russian land”.

The invasion, and its accompanying atrocities, have made any simplistic Elon Musk-style “Crimea for Donbas” deal impossible for years to come. Anything can happen now: a sudden victory for Ukraine, a long and bitter stalemate, the overthrow of Putin, all-out nuclear war. This impressive and valuable book can’t tell us which. But it is a clear, reliable and (in the circumstances) remarkably calm account of how we got here.

- Politics books

- Book of the day

Most viewed

Spend $75 or more for free US shipping

- Open media 1 in modal

The Story of a Life

By konstantin paustovsky , translated from the russian by douglas smith.

Couldn't load pickup availability

In 1943, the Soviet author Konstantin Paustovsky started out on what would prove a masterwork, The Story of a Life , a grand, novelistic memoir of a life spent on the ravaged frontier of Russian history. Eventually expanding to fill six volumes, this extraordinary work of a lifetime would establish Paustovsky as one of Russia’s great writers and lead to a nomination for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Here the first three books of Paustovsky’s epic autobiography—long unavailable in English—appear in a splendid new translation by Douglas Smith. Taking the reader from Paustovsky’s Ukrainian youth, his family struggling on the verge of collapse, through the first stirrings of writerly ambition, to his experiences working as a paramedic on the front lines of World War I and then as a journalist covering Russia’s violent spiral into revolution, this vivid and suspenseful story of coming-of-age in a time of troubles is lifted by the energy and lyricism of Paustovsky’s prose and marked throughout by his deep love of the natural world. The Story of a Life is a dazzling achievement of modern literature.

Additional Book Information

Series: NYRB Classics ISBN: 9781681377223 Pages: 816 Publication Date: February 14, 2023

Paustovsky imbued Soviet literature with tender curiosity about ordinary people and loving care for the natural world. He captured all the beauty, turbulence and injustice of his youth, and the strange blend of horrific violence and intoxicating hope that arrived with the revolution. —Sophie Pinkham, The Washington Post

At its best, The Story of a Life rivals any autobiography in world literature. Its hero is imagination itself. —Gary Saul Morson, Wall Street Journal

The quality of [Paustovsky's] narrative imagination make The Story of a Life , the Proust-length autobiography he started in 1943, a masterpiece. —Julian Evans, Daily Telegraph

In Douglas Smith's revelatory new translation of the first three volumes, late imperial Russia and Ukraine, the Revolution and the Civil War are observed with astounding clarity and originality. . . . Smith's limpid and outstandingly readable translation finally captures this unique voice, and should assure Konstantin Paustovsky's monumental autobiography a substantial new readership. —Polly Jones, TLS

One of the great Russian autobiographies, as fresh now as the day it was written—and the day it was lived. —Julian Barnes

The Story of a Life combines high drama with heroic misadventure in a comico-lyrical amalgam of history and domestic detail that enchants from start to finish. . . . The book is brimful of vivid character sketches, racy incidents and sharp-focused vignettes. Passages of striking lyric beauty. . . . The Story of a Life radiates a terrific vim and thirst for experience. A more gloriously life-affirming book is unlikely to emerge this year. —Ian Thomson, The Spectator

Paustovksy’s gift is in vivid and humane presentation of the numberless figures who populate his life. . . . For Paustovsky, books are like stars in the darkness, and ‘literature draws us closer to the golden age of our thoughts, our feelings and our actions’. He was, unquestionably, a part of that golden age, and now with this lively new translation of his memoir, he can be again. —John Self, The Times

Paustovsky is neither sanguine, nor scathing about communist life, while his prose is highly observational, free from argumentation or theoretical prattle. Instead, he details the emergence of his individual consciousness, dedicated to writing, his country, and the cultivation of a rich inner life, which, set against the developments of early 20th century Ukraine and Russia, makes for a compelling ground-level work of historical testimony. — Matt Janney, The Calvert Journal

A mid-century Soviet Thoreau. —Joshua Yaffa, The New Yorker

Shopping for someone else but not sure what to give them? Give them the gift of choice with a New York Review Books Gift Card.

A membership for yourself or as a gift for a special reader will promise a year of good reading., is there a book that you’d like to see back in print, or that you think we should consider for one of our series let us know.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

- Opens in a new window.

Advertisement

Supported by

editors’ choice

6 New Books We Recommend This Week

Suggested reading from critics and editors at The New York Times.

- Share full article

It’s a happy coincidence that we recommend Becca Rothfeld’s essay collection “All Things Are Too Small” — a critic’s manifesto “in praise of excess,” as her subtitle has it — in the same week that we also recommend Justin Taylor’s maximalist new novel “Reboot,” an exuberant satire of modern society that stuffs everything from fandom to TV retreads to the rise of conspiracy culture into its craw. I don’t know if Rothfeld has read Taylor’s novel, but I get the feeling she would approve. Maybe you will too: In the spirit of “more, bigger, louder,” why not pick those up together?

Our other recommendations this week include a queer baseball romance novel, an up-to-the-minute story about a widower running for the presidency of his local labor union, a graphic novelist’s collection of spare visual stories and, in nonfiction, a foreign policy journalist’s sobering look at global politics in the 21st century. Happy reading. — Gregory Cowles

REBOOT Justin Taylor

This satire of modern media and pop culture follows a former child actor who is trying to revive the TV show that made him famous. Taylor delves into the worlds of online fandom while exploring the inner life of a man seeking redemption — and something meaningful to do.

“His book is, in part, a performance of culture, a mirror America complete with its own highly imagined myths, yet one still rooted in the Second Great Awakening and the country’s earliest literature. It’s a performance full of wit and rigor.”

From Joshua Ferris’s review

Pantheon | $28

YOU SHOULD BE SO LUCKY Cat Sebastian

When a grieving reporter falls for the struggling baseball player he’s been assigned to write about, their romance is like watching a Labrador puppy fall in love with a pampered Persian cat: all eager impulse on one side and arch contrariness on the other.

“People think the ending is what defines a romance, and it does, but that’s not what a romance is for. The end is where you stop, but the journey is why you go. … If you read one romance this spring, make it this one.”

From Olivia Waite’s romance column

Avon | Paperback, $18.99

ALL THINGS ARE TOO SMALL: Essays in Praise of Excess Becca Rothfeld

A striking debut by a young critic who has been heralded as a throwback to an era of livelier discourse. Rothfeld has published widely and works currently as a nonfiction book critic for The Washington Post; her interests range far, but these essays are united by a plea for more excess in all things, especially thought.

“Splendidly immodest in its neo-Romantic agenda — to tear down minimalism and puritanism in its many current varieties. … A carnival of high-low allusion and analysis.”

From David Gates’s review

Metropolitan Books | $27.99

THE RETURN OF GREAT POWERS: Russia, China, and the Next World War Jim Sciutto

Sciutto’s absorbing account of 21st-century brinkmanship takes readers from Ukraine in the days and hours ahead of Russia’s invasion to the waters of the Taiwan Strait where Chinese jets flying overhead raise tensions across the region. It’s a book that should be read by every legislator or presidential nominee sufficiently deluded to think that returning America to its isolationist past or making chummy with Putin is a viable option in today’s world.

“Enough to send those with a front-row view into the old basement bomb shelter. … The stuff of unholy nightmares.”

From Scott Anderson’s review

Dutton | $30

THE SPOILED HEART Sunjeev Sahota

Sahota’s novel is a bracing study of a middle-aged man’s downfall. A grieving widower seems to finally be turning things around for himself as he runs for the top job at his labor union and pursues a love interest. But his election campaign gets entangled in identity politics, and his troubles quickly multiply.

“Sahota has a surgeon’s dexterous hands, and the reader senses his confidence. … A plot-packed, propulsive story.”

From Caoilinn Hughes’s review

Viking | $29

SPIRAL AND OTHER STORIES Aidan Koch

The lush, sparsely worded work of this award-winning graphic novelist less resembles anything recognizably “comic book” than it does a sort of dreamlike oasis of art. Her latest piece of masterful minimalism, constructed from sensuous washes of watercolor, pencil, crayon and collage, pulses with bright pigment and tender melancholy.

“Many of these pages are purely abstract, but when Koch draws details, it’s in startlingly specific and consistent contours that give these stories a breadth of character as well as depiction.”

From Sam Thielman’s graphic novels column

New York Review Comics | $24.95

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30 , yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety .

“Real Americans,” a new novel by Rachel Khong , follows three generations of Chinese Americans as they all fight for self-determination in their own way .

“The Chocolate War,” published 50 years ago, became one of the most challenged books in the United States. Its author, Robert Cormier, spent years fighting attempts to ban it .

Joan Didion’s distinctive prose and sharp eye were tuned to an outsider’s frequency, telling us about ourselves in essays that are almost reflexively skeptical. Here are her essential works .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

Ukraine Has Changed Too Much to Compromise With Russia

My generation has tasted freedom and experienced a competitive, vibrant political life. We can’t be made a part of what Russia has become.

H ere in Ukraine , we often react very emotionally when we hear people in the West calling for peace with Russia. According to some commentators , this would be achieved by means of a “compromise,” entailing Ukrainian “concessions” that would somehow satisfy the Kremlin and stop the war: major territorial giveaways, armed forces reduced to insignificance, no further integration with the West—you name it.

Most of us see such views as extremely naive, given the totalitarian and militaristic nature of Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Having built his rule on war hysteria, land grabs, imperial chauvinism, and global confrontation, Putin is hardly likely to stop even at a deal that most Ukrainians would find entirely unacceptable.

But that leads us to another problem that much of the Western media fail to fully appreciate: Ten years of confrontation with the Kremlin, and especially the past two years of Russia’s full-scale invasion, have fundamentally changed Ukraine. These changes are not superficial or easily swept away.

Read: The one element keeping Ukraine from total defeat

A little more than a decade ago, many young Ukrainians—including those, like myself, from Ukraine’s Russian-speaking east—were angry and restless, itching for something we saw just over the horizon. In high schools and universities, we read Montesquieu and soaked up such tantalizing concepts as the rule of law, democracy, and human rights. Western values felt native to our generation; we were open to the world in a way that our parents had never imagined. Most of them had ventured no farther than Central Asia for their Soviet military service, or maybe Moscow for the 1980 Olympics.

My peers and I wanted our country to have clean streets, polite police, and government officials who would resign at the exposure of petty corruption scandals. We wanted to be able to start businesses without passing money under the table, and to trust that courts of law would render justice. What we did not want were irremovable, lifetime dictators who packed the government with cronies on the take and sent goons to beat us up in the streets.

In Kyiv’s Maidan Square, starting in November 2013 and lasting into February 2014, demonstrators showed their fervor for such a future in what became known as the Revolution of Dignity. Some gave their lives to unseat Viktor Yanukovych, the kleptocratic ruler Moscow supported, and orient Ukraine unequivocally toward the West. At the site of desolation, armloads of flowers commemorated these dead. Yanukovych fled a country that despised him and had spiraled out of his control.

A new Ukraine began—and with it, a decade-long war of independence, as the Kremlin marked our revolution by seizing Crimea and infiltrating the Donbas region in the country’s east. For nearly a decade, Ukraine was fighting on two fronts: a military war against Russia, and an internal struggle for its revolution’s ideals, which meant stamping out corruption, obsolescence, unfreedom—everything that might drag the country back into the past.

Ukraine is still far from achieving all that my generation once dreamed of. But we do live in a country that is radically different from the Russian-influenced Ukraine of 2013—politically, mentally, and culturally. And we are starkly different from Putin’s Russia.

Ukrainians have tasted freedom and experienced a competitive, vibrant political life. We elected a comedian to be our leader after he faced down an old-school political heavyweight in a debate that was held in a giant stadium in downtown Kyiv and aired live to the nation. We’ve reinvented Ukrainian culture, generating new music, poetry, and stand-up comedy. Starting in 2014, we had to build our country’s armed forces almost from scratch; we are insanely proud of them, as they have fought heroically against one of the largest and most brutal war machines in existence.

A few weeks ago , I brought my dog to a veterinarian in Bucha, the town outside Kyiv where Russian forces committed a well-documented massacre in 2022. As the young doctor handled my dog, I noticed a large Ukrainian trident entwined with blue and yellow ribbons tattooed on her wrist under her white sleeve. For my generation of Ukrainians, such national symbols are an expression of pride in all we’ve made and defended.

I was with one of the first groups of journalists to enter Bucha after the Russian retreat in 2022. To describe the atmosphere is very difficult: I remember rot, stillness, a miasma of grief. The Russians had graffitied the letter V everywhere. On a fence along the main street: Those entering the no-go zone shall be executed. V. We followed the Ukrainian police as they broke through doors into premises inhabited only by the dead. Some of the bodies were charred and mutilated. I saw two males and two females lying on the ground, incompletely burned, their mouths open and hands twisted. One looked to be a teenage girl.

Outside the Church of Andrew the Apostle—a white temple that rises high over Bucha—Ukrainian coroners in white hazmat suits carefully removed layers of wet, clayish soil from a mass grave and placed 67 bodies on simple wooden doors under the cold drizzle. A tow truck hoisted the cadavers out one by one, hour by hour. Now and again, the rain would pick up, and the coroners would hastily cover the grave with plastic sheeting stained with dried gore.

“My theory is that there was a very brutal Russian commander in charge of Bucha,” Andriy Nebytov, the chief of police for Kyiv Oblast, told reporters at the church that day. “And they unleashed hell in this place.”

The Continent apartment complex used to be one of the finest in Bucha. I met a guy named Mykola Mosyarevych in a basketball court there. In his 30s and fit, he was a likely target for the Russians—a potential guerrilla fighter or member of the Territorial Defense—and so he’d spent the whole month in a basement. After the Russians left Bucha, on the day of my visit, he sat staring at a pair of ripped Russian fatigues marked with the orange-and-black striped ribbon of Saint George—a symbol of war and love for destruction. He wept. Over and over again, he said: “I just don’t understand. I don’t understand. I don’t understand why they would want to do all this to us.”

We all asked similar questions, and our fragmentary answers could bring little comfort to Mosyarevych or anyone else: lust for power, years of aggressive propaganda, a sense of impunity, a would-be emperor grasping at illusion. Deep down, fear.

Read: Ukraine’s shock will last for generations

Later that day, I walked alone with my camera through what was left of a Russian armored column on Vokzalna Street. Bucha’s defenders recalled that the Russians in this column had been moving carelessly and singing patriotic songs when Ukrainian forces struck their leading and trailing vehicles. The column stopped. The remaining Russian vehicles scrambled like bumper cars to maneuver through the wreckage, find a way out, and save themselves. But Vokzalna Street is narrow: They were trapped. A Ukrainian artillery strike left hardly any vehicle whole. The layer of ash on the ground was so thick that it crunched underfoot like snow.

What used to be a leafy green lane, part of my favorite bicycle route to Bucha and Hostomel, had become a cemetery. But within three weeks, Ukrainian workers had cleared away the rubble and repaved the road. Later, Warren Buffett’s son donated funds for Ukrainian authorities to completely renovate the street and construct new, Scandinavian-style, single-family houses with lawns and picket fences. Online, people posted tens of thousands of likes and comments under images comparing Vokzalna Street during the Russian occupation and after.

Springtime soon came, too, and with it snaking lines of cars, as thousands of people who had fled poured back into their hometown days after its liberation. Young mothers returned with their strollers. Time would absorb the grief and horrors of this war, as it had of so many that had come before.

Even so, I don’t want to think about what will happen to my dog’s veterinarian if the Russians make it back to Bucha. Or what will happen to Ukraine. After everything that’s transpired over the past decade—and especially given what Russia has become—Ukraine must not be made a Russian colony again.

Today’s Russia is a neo-Stalinist dictatorship led by an aging chauvinist. In the grip of his messianic delusion, Putin initiated the biggest European war since World War II. He seeks to eliminate Ukraine not only as an independent nation, but also as an idea. No concessions or compromises are possible with such a vision—not given the kind of country Ukrainians have made and fought to defend.

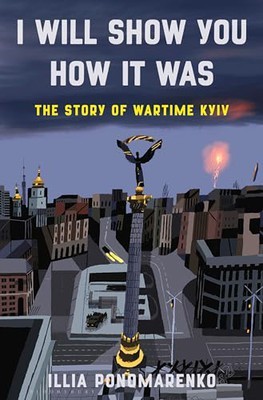

This essay is adapted from I Will Show You How It Was: The Story of Wartime Kyiv , published on May 7 by Bloomsbury.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

COMMENTS

A screenshot of a video released by the Ukrainian Police Department Press Service of military helicopters, apparently Russian, over the outskirts of Kyiv, February 24, 2022. On February 24, six hours after this article was filed, Russia began an all-out attack on Ukraine. Kyiv/Kiev weather forecast : +5C, windy, chances of Russian attack 30% ...

The most thought-provoking of the new crop of books about the war in Ukraine is Alexander Etkind's quick and incisive RUSSIA AGAINST MODERNITY (Polity, 166 pp., paperback, $19.95). The book is ...

Ukraine faces extraordinary challenges, but it also presents a challenge for Europe—and a great opportunity. Tetiana, a young activist I met in Lviv last December, works part-time as a tattooist. People often ask for tattoos of the Ukrainian flag or the country's trident symbol, she told me, but one of the most popular since Russia's full ...

6 Books to Read for Context on Ukraine. Joumana Khatib Reading in Brooklyn. Red Famine, by Anne Applebaum. More than three million Ukrainians died of starvation in the 1930s, the result of an ...

The incremental Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014—which began with the seizure of Crimea and continued as a hybrid operation, capitalizing on anti-Kyiv sentiment in eastern Ukraine and backed ...

The complicated, generous life of Paul Auster, who died on April 30, yielded a body of work of staggering scope and variety. "Real Americans," a new novel by Rachel Khong, follows three ...

In February 2022, the editorial staff at C.P. Publishing in Kyiv was hard at work on THE BEAUTY OF UKRAINE (TENEUES, $70), a book of landscape photography by the Odesa-born Yevhen Samuchenko, when ...

Recent Ukrainian Writing. Alexandra Alter Reading in Brooklyn. Voroshilovgrad, by Serhiy Zhadan. . Zhadan is one of Ukraine's premiere counter culture writers. This novel follows a character ...

The simplest answer is the timelessness of the story. It is a morality tale.". February 27, 1986 issue. "French politics after 1900 were not the same as before. Perhaps even without the Affair, the new forces—socialists demanding reform, syndicalists calling for direct action, a new right-wing anti-democratic nationalism represented by ...

New York Review Books A Memoir of the Warsaw Uprising , by Miron Białoszewski On August 1, 1944, the Polish underground Home Army rose up against German occupiers.

His book Ukraine: The Forging of a Nation is a bestseller at home and was published a few months before Vladimir Putin's all-out attack. It puts Ukraine's past - "permeated with violence ...

Publishing has yet to offer new books on the Ukraine-Russia struggle, though that is sure to change. ... New York Review Books: 272 pages, $18 ... former Moscow bureau chief for the New York Times ...

Named among the New York Public Library's best books of 2021, I Will Die in a Foreign Land chronicles what Ukrainian protests looked like in 2013 and 2014, as demonstrators pushed for closer ties ...

The Russo-Ukraine War by Serhii Plokhy is published by Allen Lane (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply.

January 12, 2024. Welcome to the Books Briefing, our weekly guide to The Atlantic's books coverage. Join us Friday mornings for reading recommendations. A century and a half after they were ...

As Russian forces breached the border with Ukraine late last month, Kate Tsurkan issued an urgent call for help on social media. Tsurkan, a translator who lives in Chernivtsi, a city in western ...

by Konstantin Paustovsky, translated from the Russian by Douglas Smith. $24.95. Available as E-Book Biography & Memoir Russian Literature. Format. Paperback Ebook. Quantity. Add to cart. Add to Wishlist. In 1943, the Soviet author Konstantin Paustovsky started out on what would prove a masterwork, The Story of a Life, a grand, novelistic memoir ...

Description. One of The New York Times' "6 Books to Read for Context on Ukraine" "A short and insightful primer" to the crisis in Ukraine and its implications for both the Crimean Peninsula and Russia's relations with the West (New York Review of Books)The current conflict in Ukraine has spawned the most serious crisis between Russia and the West since the end of the Cold War.

THE RETURN OF GREAT POWERS: Russia, China, and the Next World War Jim Sciutto Sciutto's absorbing account of 21st-century brinkmanship takes readers from Ukraine in the days and hours ahead of ...

Source: Getty. May 7, 2024, 7 AM ET. Here in Ukraine, we often react very emotionally when we hear people in the West calling for peace with Russia. According to some commentators, this would be ...