Taking Math Outdoors: A Natural Learning Environment

by Michèle Mazzocco , Rachel Olson & Sheila Williams Ridge

Early math experiences that occur through outdoor play can help develop children’s math skills and positive math attitudes.

- There are many benefits to supporting early math learning outdoors.

- Caregivers and teachers can help develop young children’s math skills without taking over their outside playtime.

- See examples of how to incorporate nature into math teaching in this short video .

Nature and outdoor spaces offer many opportunities for teachers, parents, and caregivers to engage young children in high-quality math learning. When exploring the outdoors, children naturally play with math in a joyful way that is meaningful to them. Early math experiences that occur through play can help develop children’s math skills and positive math attitudes.

In this blog, we highlight some ways that caregivers can support children’s mathematical thinking during outdoor play. The goal is for caregivers to recognize math opportunities in nature and to support and plan for learning around them.

Supporting Nature-Based Math Education

Caregivers can build on children’s interests and ideas to promote math learning without taking over their outside playtime. Some ways to do this are to support children’s problem-solving, prompt children to reflect on problems, introduce new and relevant words and concepts, and create an environment where children are likely to discover a problem that needs solving in the first place!

For children who enjoy collecting things: Suggest that children pay attention to a certain feature, such as weight, length, or color. “Wow, notice how those leaves are all different sizes?” Then see how children’s thinking inspires them to generate ideas or more questions, such as how they can line up, build, or compare the leaves.

For children who enjoy exploring: Offer a question a child can test. “I wonder why that stick rolls down the hill but the other one does not?” or “I wonder how you can make sure your twig house is big enough for your toy truck to fit inside it.” These suggestions prompt children to consider concepts that support early math development, such as the shape, speed, and density of the rolling stick, or the length and width of the twig house.

For children with high energy: Find ways for children to engage in active learning outdoors. “How far you can throw that ball? How fast can we run from this side to that side? Which tree is the farthest from here? Count your steps to find out!”

Benefits of Outdoor Math Play

Lots of space for fun, energetic play. Early math is playful, in part because it involves creative problem solving that children naturally engage in during free play—especially if their environment is set up for it! [1] Whether your outdoor environment is a natural outdoor space, a constructed playground, or a combination of both, outdoor spaces offer more room to move around compared to typical indoor spaces for preschoolers. Outdoor settings also provide a variety of real life, hands-on materials like leaves, plants, twigs, rocks, holes, hills, puddles, swings, sidewalks, or slides. Caregivers can encourage children to count, examine, and manipulate objects as part of early math discussions on topics like measurement and data collection.

Opportunities for children to develop their own goals and questions. Children naturally gravitate toward outdoor activities that interest them. They are also more motivated to learn and problem-solve when engaged in activities that are interesting to them. For example, one child may enjoy collecting objects in nature, and another child may use the objects to achieve a goal they have in mind, such as using twigs to build a house in the sand box or arranging larger sticks to create a fort.

Teachers and caregivers can help spark children’s ideas by making available tools that invite exploration, such as:

- Shovels left by the dirt so that children can dig holes of different depths and for different purposes.

- Weigh scales left near collections of pinecones and acorns so children can compare weight, size, and surface characteristics between them.

- Collections of items left out so children can sort, toss, roll, or count their newfound treasures.

Recognition that math is meaningful and everywhere. Incorporating natural objects (e.g., leaves, twigs, stones) and naturally occurring landforms (e.g., hills, trees) into children’s learning demonstrates that math is embedded in nature. Further, answering questions that children think of while playing outdoors helps them see math as a tool to solve real-world problems. [2] By using math to solve problems that arise through play, children begin to understand the importance of math in everyday life.

Supports children’s overall development. Children who regularly play outside have opportunities to engage in physical activity, and outdoor play can improve attention skills and elevate mood. [3] Research suggests that physical benefits are especially prominent when playing in natural outdoor environments, such as a forest, compared to surface playgrounds. [4]

See Outdoor Math Learning in Action

Children often initiate outdoor play themselves, but teachers play an important role in guiding children’s learning through their intentional support. In this video , Sheila Williams Ridge, director of the Shirley G. Moore Lab School at the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota, offers guidance for teaching math and problem-solving in playful outdoor settings.

[1] Diamond, A. (2010). The Evidence Base for Improving School Outcomes by Addressing the Whole Child and by Addressing Skills and Attitudes, Not Just Content. Early Education & Development, 21 (5), 780-793. doi:10.1080/10409289.2010.514522

[2] Mathematics Standards. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.corestandards.org/Math/

[3] Burdette, H. L., & Whitaker, R. C. (2005). Resurrecting Free Play in Young Children. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159 (1), 46. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.1.46

[4] Fjortoft, I. (2003). Symposium 19: The interactive nature of motor learning: Landscape as playscape: Motor learning in natural environments. PsycEXTRA Dataset . doi:10.1037/e547922012-109

Related posts

Creating High-Quality Math Center Activities

Teaching Measurement and Data to Young Children

10 Ideas for Promoting Early Math and Peer Collaboration Skills

Join our mailing list to stay updated.

Email Address *

Your Name *

- Parent/Family member Parent/Family member

- Teacher/Early childhood provider Teacher/Early childhood provider

- Family educator Family educator

- Teacher educator Teacher educator

- Researcher Researcher

- Other Other

Boobytrap Label

Outdoor learning has huge benefits for children and teachers — so why isn’t it used in more schools?

PhD Researcher in Medical Studies, Swansea University

Research Assistant in Child Health and Well-being, Swansea University

Professor in Public Health Data Science, Swansea University

Disclosure statement

Emily Marchant receives funding from the ESRC and the National Centre for Population Health and Wellbeing Research (NCPHWR).

Charlotte Todd receives funding from the National Centre for Population Health and Wellbeing Research (NCPHWR).

Sinead Brophy does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Swansea University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

Research shows that healthier and happier children do better in school , and that education is an important determinant of future health . But education is not just about lessons within the four walls of a classroom. The outdoor environment encourages skills such as problem solving and negotiating risk which are important for child development.

But opportunities for children to access the natural environment are diminishing. Children are spending less time outside due to concerns over safety, traffic, crime , and parental worries. Modern environments have reduced amounts of open green spaces too, while technology has increased children’s sedentary time. It is for these reasons and more that many think schools have arguably the greatest potential – and responsibility – to give children access to natural environments.

This is not just about improving break times and PE lessons, however. Across the UK, teachers are getting children outdoors by delivering curriculum-based lessons in school grounds or local areas. A variety of subjects, such as maths, art and science, are all being taken outside.

Although there are no official statistics on how much outdoor learning is used, researchers have seen that its use is increasing . And while it is not part of the country’s curricula for year three onwards in primary schools (age seven up), these outdoor initiatives are supported for all ages by the UK government, which has invested in the Natural Connections project run by Plymouth University, for example, and Nature Friendly Schools run by The WildLife Trusts.

However, despite the support, outdoor learning is still underused in primary schools – particularly in the latter years, when children are aged between seven and 11. So if there are such big benefits to outdoor learning, why isn’t it happening more often? For our recently published study , we spoke to teachers and pupils to find out.

School adventures

Through interviews and focus groups, we asked teachers and pupils their opinions on outdoor learning. The participants we spoke to all take part in the HAPPEN project , our primary school health and education network . These educators and students (aged between nine and 11) engage in outdoor learning – which we classed as teaching the curriculum in the natural environment – for at least an hour a week. Overall, the participants spoke of a wide range of benefits to pupils’ well-being and learning. However, a number of challenges also existed.

The pupils felt a sense of freedom when outside the restricting walls of the classroom. They felt more able to express themselves, and enjoyed being able to move about more too. They also said they felt more engaged and were more positive about the learning experience. In addition, we also heard many say that their well-being and memory were better. One student commented:

When we go out to the woods we don’t really know we’re doing it but we’re actually doing maths and we’re doing English, so it’s just making it educational and fun at the same time.

Teachers meanwhile discussed the different approach to lessons, and how it helped engage all types of learners. They also felt that children have a right to be outdoors – especially at a time when their opportunities to access the natural environment is limited – and schools were in a position to fulfil this.

Importantly, the teachers spoke of increased job satisfaction, and that they felt that it was “just what I came into teaching for”. This is particularly important as teacher well-being is an essential factor in creating stable environments for pupils to learn , and current teacher retention rates are worrying .

Rules and boundaries

At first the teachers had concerns over safety, but once pupils had got used to outdoor learning as part of their lessons, they respected the clear rules and boundaries. However, the teachers also told us that one of the main reasons why they didn’t use outdoor learning more often was because it made it difficult to measure and assess learning outcomes. The narrow measurements that schools are currently judged on conflict with the wider benefits that outdoor learning brings to children’s education and skill development. It is hard to demonstrate the learning from outdoors teaching using current assessment methods. As one teacher said, “there is such a pressure now to have evidence for every session, or something in a box, it is difficult to evidence the learning [outdoors]”.

Funding was also raised an issue as outdoor clothes, teacher training and equipment all need additional resources.

Our findings add to the evidence that just an hour or two of outdoor learning every week engages children, improves their well-being and increases teachers’ job satisfaction. If we want our children to have opportunities where “you don’t even feel like you’re actually learning, you just feel like you are on an adventure” and teachers to “be those people we are, not robots that it felt like we should be”, we need to change the way we think about school lessons. Teaching doesn’t need to follow a rigid classroom format – a simple change like going outside can have tremendous benefits.

- Primary school

- Primary schooling

- Outdoor learning

- primary schools

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Communications and Engagement Officer, Corporate Finance Property and Sustainability

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Rocking and Rolling. Fresh Air, Fun, and Exploration: Why Outdoor Play Is Essential for Healthy Development

You are here

Coteachers Marissa and Kate are out for a walk around the block with a small group of 18- to 30-month-olds. The sky is a brilliant blue and there are bright green grass shoots and spring leaves to touch and smell. Two-and-a-half-year-old Aisha approaches Marissa, eyes shining, clutching a treasured object in her hand. She uncurls her fingers to reveal an acorn. “Look!” she says. “What dis?”

“Wow! That’s an acorn. It fell from the tree last fall,” Marissa answers. “If you plant it in the ground, it will grow into a big tree.”

Aisha discovers two more acorns and shares them with Brady, who is 2 years old. Kate offers Aisha and Brady small bags they can use to collect more acorns and other interesting objects they find during the walk. The group’s progress around the block is slow as the children find twigs, old brown leaves, new green leaves, and more acorns to bring back to the center.

It can be challenging to take young children outside—from naps to mealtimes and sunscreen to mittens, a trip outdoors might feel like too much hassle. Additionally, play outside may seem unruly, overwhelming, or lacking in learning opportunities. But outdoor play is worth the time and effort.

What are the benefits of outdoor play?

1. it invites children to learn science.

As seen in the opening vignette, you don’t have to plan for science lessons when you take young children outside. Children are natural explorers and discoverers, and you can bring whatever interests them back to your early childhood setting for further exploration. By turning their questions into group inquiry projects, you’ll soon have several starting points for emergent curriculum. An acorn won’t grow quickly enough to satisfy a curious child—it takes two months for the first shoots to appear! But there are faster-growing seeds (peas, green beans, corn) perfect for classroom experiments. Picture books like The Carrot Seed , by Ruth Krauss, and Growing Vegetable Soup , by Lois Ehlert, add early literacy to the mix while building children’s vocabulary and knowledge.

2. It creates opportunities for social interaction and collaboration

One-on-one interactions, like the conversation between Aisha and Marissa in the vignette, help build a foundation for future teacher relationships that will occur when children enter school. Marissa’s interest and delight in Aisha’s discovery reinforce Aisha’s knowledge that she’s important and her ideas matter. Outdoor play also provides a chance to practice social and emotional skills with other children, including problem solving, turn taking, encouragement, self-control, safe risk taking, and following the rules of a game. And outdoor play provides opportunities to develop empathy; for example, imagine one child encouraging another to try the slide or a child comforting another who has fallen down while running.

3. It promotes physical health

The obesity rate for US children ages 2 to 5 is 14 percent, and it rises to over 40 percent for middle-aged adults, leading to an increased risk of health problems like diabetes and heart disease (Hales et al. 2017). That’s one reason why the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a “prescription for play” at every well-child visit through age 2 (Yogman et al. 2018, 10) and Nemours Health and Prevention Services recommends daily, supervised outdoor time for children from birth to age 5 (Hughes 2009). Specifically, Nemours calls for toddlers to have at least 30 minutes of structured (adult-led) physical activity and at least 60 minutes of unstructured (child-led) physical activity each day. Outdoor play is a great way to model the joy of physical activity. When children run, jump, climb, throw and kick balls, and ride toys that require balance, they also build gross motor skills and start developing a habit of being active.

4. It invites new contexts for learning

You can use outdoor spaces to create intentional learning activities that are difficult to execute inside. There’s great value in looking at books about nature in the shade of a tree, pouring (and splashing!) water at an outdoor water table, building extra large structures in the sandbox or mud, collecting leaves, watching a parade of ants, and playing pretend on a playground structure. To make the most of your outdoor time, think about creative, joyful, engaging activities that capitalize on children’s need to move and enthusiasm for doing so, while also achieving other curricular goals. For example, you might create a sorting game in which children have to find all the yellow balls and all the red balls hidden on the playground, then sort them into two groups.

5. It promotes better sleep

A study of 2- to 5-year-olds showed that children who play outdoors sleep better at night (Deziel 2017). This may be due to the physical activity, stress reduction, and exposure to natural light that come with playing outdoors (Coyle 2011). You may want to share this information with families—a tired, happy child is one who sleeps well!

6. It gives children a chance to take appropriate risks

Toddlers are all about challenging themselves to do new and difficult things—pet a dog, climb some stairs, venture a little farther away from a caregiver and then return. Playing outside provides opportunities to run faster, climb higher, jump farther, and more—all under the watchful eye of a caring adult.

7. It may lead to better learning outcomes once children return to other activities

Research shows that older children are more attentive and productive in the classroom when recess—indoors or outdoors—is part of the school day (Council on School Health 2013). If older children need a brain break, it follows that younger ones do too.

8. It supports STEM skills

Remember making mud pies and forts when you were a child? The outdoors is the perfect place for big (and messy) projects that support STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) skills, such as building, sand and water play, and investigations of the natural world. Almost any indoor activity can be brought outside for further exploration.

9. It anchors children to the real world

Talking with a child about an illustration of a bird in a picture book is good, but sharing the book and the experience in the real world is even better: “I wonder what that robin is looking for in the grass? Oh, look! It got a worm!” Children develop more comprehensive knowledge about their world when they have a chance to watch, observe, predict, and learn in the moment.

Playing outdoors has benefits for both young children and educators. It’s a refreshing pause in the day’s schedule—time set aside to look and listen, explore and observe, move and let loose. Time spent outside can lead to better physical and mental health, improved sleep, and cognitive, social, and emotional gains for young children. Ensuring that outdoor play is an integral part of your child care and education setting’s daily schedule supports early learning across all domains and unleashes a whole lot of joy—for you and for children!

Think about it

- Reflect on your feelings about being outside. What do you enjoy or dislike about being outdoors?

- What are your goals for outdoor play? (These can differ from day to day, depending on children’s needs, the season, and the spaces and materials you have access to for structured versus unstructured activities.)

- What routines can you create that will assist you in getting children outdoors? (Some programs have outdoor time at the beginning and end of every day so they don’t have to deal with coats and hats in the middle of the day.)

- What classroom/programmatic roadblocks exist that may make it harder to get children outdoors? How might you tackle them?

- How can you share children’s outdoor activities and accomplishments with their families?

- Mix it up: provide a balance of structured play (in which you choose the goals and initiate activities that will meet them) and unstructured play.

- When the weather outside is frightful . . . dress appropriately and make it part of the adventure! For example, observe the sound and smell of rain, the splashes boots make in puddles, and the way rainwater collects on leaves. (If possible, have some extra outdoor gear on hand for children who are not adequately dressed for the conditions.)

- The world is your canvas! Try drawing on the sidewalk with chalk, or use rollers or big brushes to paint with water.

- Start a collection: have children collect specific objects—leaves, pinecones, rocks, or whatever interests them. Use these items for sorting activities when you return to the classroom. Items can be organized by shape, color, or texture.

- Document discoveries: snap photos or take video of children’s discoveries and experiments in the outdoor “classroom.” Post photos or videos in a place where children and their families can see them. Create a classroom book that shows what children are doing and learning outside.

Council on School Health. 2013. “The Crucial Role of Recess in School.” Policy statement. Pediatrics 131 (1). http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/1/183 .

Coyle, K.J. 2011. Green Time for Sleep Time: Three Ways Nature and Outdoor Time Improve Your Child’s Sleep: A Guide for Parents and Caregivers . Reston, VA: National Wildlife Federation. www.nwf.org/~/media/PDFs/Be%20Out%20There/BeOutThere_GreenTimeforSleepTi... .

Deziel, S. 2017. “5 Reasons Why Every Kid Should Play Outside.” Today’s Parent . www.todaysparent.com/kids/kids-health/unexpected-benefits-of-outdoor-play/ .

Hales, C.M., M.D. Carroll, C.D. Fryar, & C.L. Ogden. 2017. “Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2015–2016.” NCHS Data Brief #288. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf .

Hughes, D. 2009. Best Practices for Physical Activity: A Guide to Help Children Grow Up Healthy for Organizations Serving Children and Youth . Newark, DE: Nemours Health and Prevention Services. www.nemours.org/content/dam/nemours/www/filebox/service/preventive/nhps/paguidelines.pdf .

Yogman, M., A. Garner, J. Hutchinson, K. Hirsh-Pasek, & R.M. Golinkoff. 2018. “The Power of Play: A Pediatric Role in Enhancing Development.” Clinical Report. Pediatrics 142 (3): 1–18. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/142/3/e20182058... .

Rocking & Rolling is written by infant and toddler specialists and contributed by ZERO TO THREE, a nonprofit organization working to promote the health and development of infants and toddlers by translating research and knowledge into a range of practical tools and resources for use by the adults who influence the lives of young children. The column can be found online at NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/yc/columns .

Kathy Kinsner has been a reading specialist, an Emmy-winning producer on the PBS series Reading Rainbow , and the person in charge of curriculum development at nonprofit Roads to Success. She has a master’s in education from Bowling Green State University and a master’s in television, radio, and film from Syracuse University. Currently, she is the senior manager of parenting resources at ZERO TO THREE.

Vol. 74, No. 2

Print this article

Taking Math Learning Outdoors into Nature

Nature and outdoor spaces offer many opportunities for teachers, parents, and caregivers to engage young children in high-quality math learning. When exploring the outdoors, children naturally play with math in a joyful way that is meaningful to them. Early math experiences that occur through play can help develop children’s math skills and positive math attitudes.

Caregivers can build on children’s interests and ideas to promote math learning without taking over their outside playtime. Some ways to do this are to support children’s problem-solving, prompt children to reflect on problems, introduce new and relevant words and concepts, and create an environment where children are likely to discover a problem that needs solving in the first place!

See Outdoor Math Learning in Action

Supporting Nature-Based Math Education

Below, we highlight some ways that caregivers can support children’s mathematical thinking during outdoor play. The goal is for caregivers to recognize math opportunities in nature and to support and plan for learning around them.

For children who enjoy collecting things: Suggest that children pay attention to a certain feature, such as weight, length, or color. “Wow, notice how those leaves are all different sizes?” Then see how children’s thinking inspires them to generate ideas or more questions, such as how they can line up, build, or compare the leaves.

For children who enjoy exploring: Offer a question a child can test. “I wonder why that stick rolls down the hill but the other one does not?” or “I wonder how you can make sure your twig house is big enough for your toy truck to fit inside it.” These suggestions prompt children to consider concepts that support early math development, such as the shape, speed, and density of the rolling stick, or the length and width of the twig house.

For children with high energy: Find ways for children to engage in active learning outdoors. “How far you can throw that ball? How fast can we run from this side to that side? Which tree is the farthest from here? Count your steps to find out!”

Benefits of Outdoor Math Play

Lots of space for fun, energetic play. Early math is playful, in part because it involves creative problem solving that children naturally engage in during free play—especially if their environment is set up for it! Whether your outdoor environment is a natural outdoor space, a constructed playground, or a combination of both, outdoor spaces offer more room to move around compared to typical indoor spaces for preschoolers. Outdoor settings also provide a variety of real life, hands-on materials like leaves, plants, twigs, rocks, holes, hills, puddles, swings, sidewalks, or slides. Caregivers can encourage children to count, examine, and manipulate objects as part of early math discussions on topics like measurement and data collection.

Opportunities for children to develop their own goals and questions. Children naturally gravitate toward outdoor activities that interest them. They are also more motivated to learn and problem-solve when engaged in activities that are interesting to them. For example, one child may enjoy collecting objects in nature, and another child may use the objects to achieve a goal they have in mind, such as using twigs to build a house in the sand box or arranging larger sticks to create a fort.

Teachers and caregivers can help spark children’s ideas by making available tools that invite exploration, such as:

- Shovels left by the dirt so that children can dig holes of different depths and for different purposes.

- Weigh scales left near collections of pinecones and acorns so children can compare weight, size, and surface characteristics between them.

- Collections of items left out so children can sort, toss, roll, or count their newfound treasures.

Recognition that math is meaningful and everywhere. Incorporating natural objects (e.g., leaves, twigs, stones) and naturally occurring landforms (e.g., hills, trees) into children’s learning demonstrates that math is embedded in nature. Further, answering questions that children think of while playing outdoors helps them see math as a tool to solve real-world problems. By using math to solve problems that arise through play, children begin to understand the importance of math in everyday life.

Supports children’s overall development. Children who regularly play outside have opportunities to engage in physical activity, and outdoor play can improve attention skills and elevate mood. Research suggests that physical benefits are especially prominent when playing in natural outdoor environments, such as a forest, compared to surface playgrounds.

Resource Authors

Rachel Olson, Michèle Mazzocco , and Sheila Williams Ridge

Join our mailing list to stay updated.

Email Address *

Your Name *

- Parent/Family member Parent/Family member

- Teacher/Early childhood provider Teacher/Early childhood provider

- Family educator Family educator

- Teacher educator Teacher educator

- Researcher Researcher

- Other Other

Boobytrap Label

This site uses cookies to personalize content, provide social media features and to analyze traffic.

Get Your ALL ACCESS Shop Pass here →

45 Outdoor STEM Activities For Kids

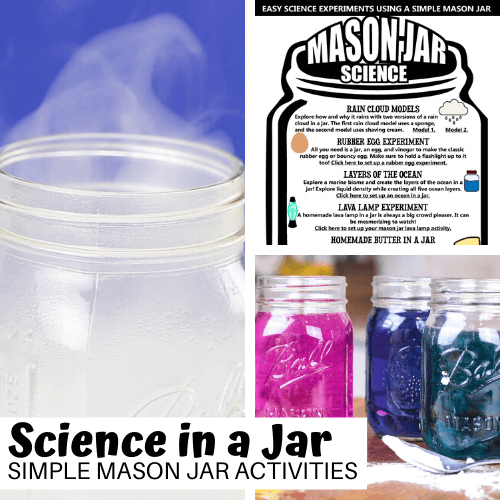

Welcome to our list of amazing outdoor STEM activities to keep your kids busy outside! Get kids outdoors to enjoy the natural world while developing problem-solving, creativity, observation, engineering skills, and more. We love easy and doable STEM projects for kids!

What Is Outdoor STEM?

These outdoor STEM activities can be used for home, school, or camp. Get kids outside and get kids interested in STEM! Take STEM outdoors, on the road, camping, or to the beach, wherever you go, but take it outside this year!

So you might ask, what does STEM stand for? STEM stands for science, technology, engineering, and math. Additionally, you might hear about STEAM , which includes an “A” for art!

We love STEM for kids because of its value and importance for the future. The world needs critical thinkers, doers, and problem solvers. STEM activities help kids better understand science, adapt to the latest technology, and engineer new solutions to solve problems of all sizes. Try our Real World STEM challenge !

Outdoor STEM is one of the best ways to get kids involved and keep them engaged. Below you will find nature STEM activities, outdoor science activities, and ideas for STEM camping activities. We even include some cool outdoor science experiments!

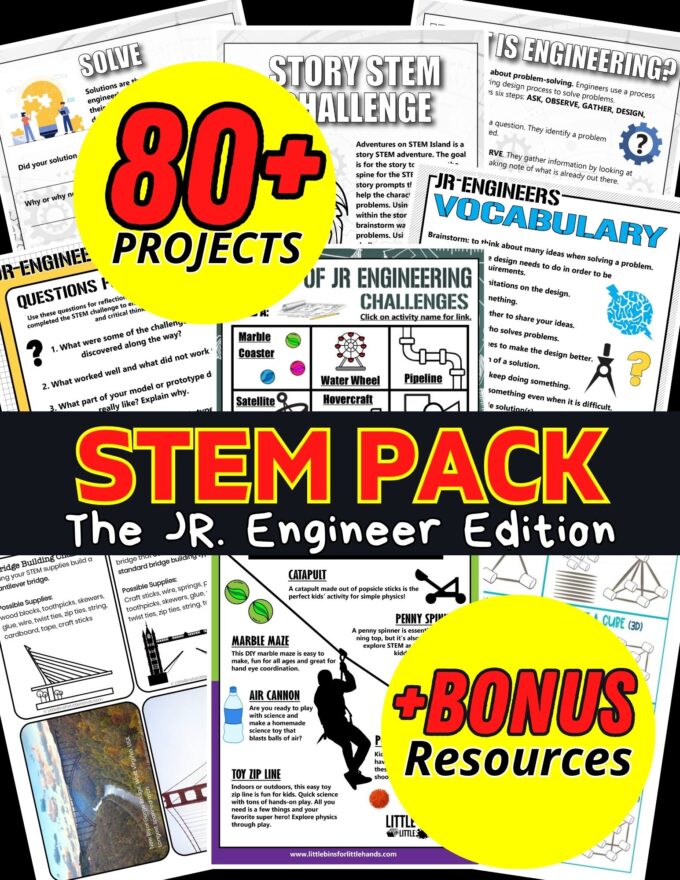

Helpful STEM Resources To Get You Started

Here are a few resources to help you introduce STEM more effectively to your kiddos or students and feel confident when presenting materials. You’ll find helpful free printables throughout.

- Engineering Design Process Explained

- What Is An Engineer

- Engineering Words

- Questions for Reflection (get them talking about it!)

- BEST STEM Books for Kids

- 14 Engineering Books for Kids

- Jr. Engineer Challenge Calendar (Free)

- Must Have STEM Supplies List

Click below to get your free printable STEM challenges!

You’ll find fantastic Nature STEM challenge cards that are meant to be done outdoors!

Outdoor STEM Activities

These outdoor STEM activities provide new ways to incorporate favorite electronics, get dirty, look at nature differently, and explore and experiment. Don’t spend too much time sitting indoors when the weather is beautiful outdoors!

Click on the links below to learn more about each activity.

Outdoor Science Experiments

- Love fizzing and exploding experiments? YES!! All you need are Mentos and coke .

- Or here is another way to do it with diet coke and mentos .

- Take this baking soda and vinegar volcano outdoors.

- Bursting Bags is a great outdoor science experiment.

- Simple outdoor science and a cool chemical reaction with an easy DIY Alka Seltzer rocket !

- Explore surface tension while you blow geometric bubbles !

- Try this color-changing slime outdoors and watch what happens!

- Set up a leakproof bag science experiment .

- Make a bottle rocket and blast off!

- Blow bubble snakes and learn about surface tension.

Nature STEM Activities

- Build an insect hotel .

- Make a cloud viewer and determine if the clouds you can see will bring rain.

- Set up a bird feeder , grab a book, and identify the birds around your house or classroom.

- Start a rock collection and learn about the rocks you find.

- Build your own mason bee house for a few simple supplies and help the pollinators in the garden.

Outdoor Engineering Projects

- Explore physics through play with this homemade Toy Zip Line .

- Design a homemade pulley system and learn about simple machines.

- Make a paper helicopter and see if it flies.

- Craft a paddle boat and watch it move!

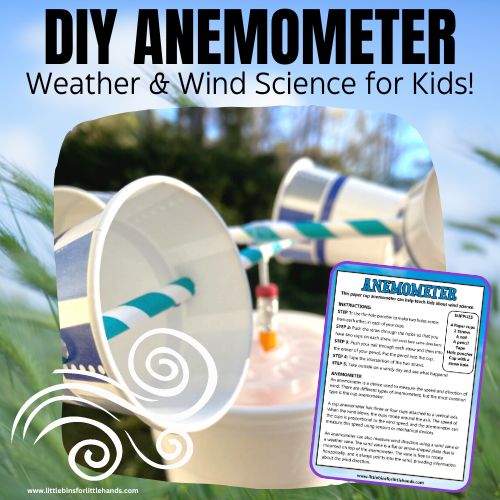

- Test the wind with a DIY Anemometer.

- Make a wind vane .

- Set up a DIY rain gauge .

- Develop those design and planning skills when you build a stick fort .

- Build a solar oven and even try s’mores on it.

- Design and build a water wall .

- Explore forces as you fly a kite .

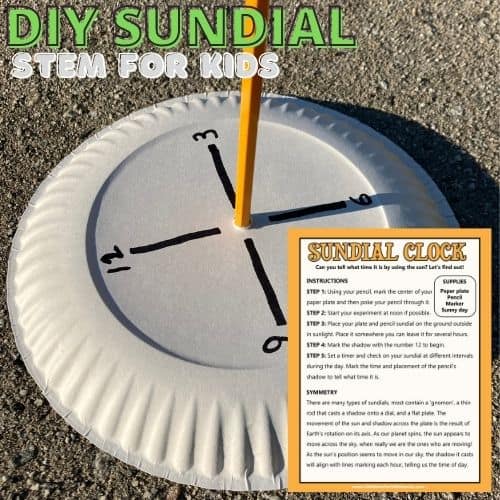

- Alternatively, track the time with a DIY sundial .

More Outdoor STEM Activities

Set up an outdoor STEM camp, explore nature-inspired STEAM, learn about the weather, or study plants.

- Want to set up a STEM camp? Check out these summer science camp ideas !

- Love science? Check out all our summer science experiments .

- Find all our nature activities and plant activities .

- Here’s our list of things to do outside for easy outdoor activities for kids.

- Get creative with these outdoor art activities .

- Design and craft a DIY kaleidoscope for kids or try this spectroscope .

- Record the moon’s phases for the month, or track the weather !

Printable Engineering Projects Pack

Get started with STEM and engineering projects today with this fantastic resource that includes all the information you need to complete more than 50 activities that encourage STEM skills!

Do you have instructions for the Stem challenges please? Particularly catapults.

- Pingback: Principle 3: Putting Some Meaning Back Into Buzzwords: Resilience, Confidence, Independent and Creative – Creative Curriculums Ontario

- Pingback: Spring STEM Activities and Plant Science Activities for Kids

- Pingback: Water Science Activities for Kids STEM

- Pingback: Simple Ways To Take STEAM Outdoors This Summer

Comments are closed.

~ Projects to Try Now! ~

How to teach numeracy outdoors

Ahead of numeracy day, discover 5 ideas for teaching numeracy outdoors from early years to secondary school..

Maths is a brilliant lesson to teach outdoors. With so many different subject areas to explore, nature provides an unbeatable canvas to engage and inspire pupils. From using leaves and pebbles to understand shapes to taking objects from the natural world to support equations, there are countless ways to make numeracy work outside of the classroom.

For many pupils, maths can be a tricky topic. It may feel harder to bring the fun to numeracy compared to a creative subject like literacy . However, stepping outside can lead to learning opportunities that are joyful, messy, engaging, and memorable; all through utilising outdoor tools that are less readily available indoors.

Why teach numeracy outdoors?

There’s no doubt that getting outside is good for us, and we know the key benefits of outdoor learning for improving child development; supporting mental health and wellbeing ; and promoting a more inclusive and engaging learning system. But why is it so valuable to teach numeracy specifically outdoors?

‘Taking maths outside isn’t just about making the subject fun. It also helps children master the very basics of the subject,’ says teacher and educational consultant, Juliet Robertson , author of Messy Maths: A Playful, Outdoor Approach for Early Years . Research shows that there are several core requirements that children need in order to get to grips with maths – all of which can be found outside! These important requirements are:

- Access to concrete materials – for example, rocks, sticks, and leaves for counting, comparing, and measuring

- A pictorial understanding – by learning outside, children can experience mathematical ideas in 3D and from every angle in real life

- An understanding of the language and symbols of numeracy – the real life context of the outdoor classroom can make tricky language a lot easier to get to grips with

So, how do you actually make the transition towards teaching your maths lessons outdoors? We’ve collected five of our favourite outdoor numeracy lesson ideas for you to explore with your pupils. Try them out for Numeracy Day, or use them to celebrate outdoor maths on Outdoor Classroom Day – there’s still time to sign up for May 18!

5 outdoor numeracy lesson ideas

Whether outdoor numeracy is a daily occurrence or something that you share every once in a while, it’s useful to have a selection of lesson plans at your fingertips. Here are five of our ‘go-to’ outdoor maths lesson activities that we love to share with our training partners and attendees. Remember – it’s OK to use our lesson ideas as inspiration rather than instruction! Feel free to ‘take it, break it, and make it your own’!

1. 2D to 3D shapes

This handy lesson idea couldn’t be easier to get started – all you need is sticks and space!

Show your pupils how to create 2D and 3D shapes using sticks from the surrounding area. This is a brilliant way to show children the difference between 2D and 3D, and how you can move shapes from one form to another. The more confident they get, the more complicated shapes you can play around with.

Download 2D to 3D shapes .

2. Building Bridges

Playground covered in puddles ? Perfect!

With Building Bridges, children get the chance to build a bridge that will (or perhaps will not!) hold their weight, enabling them to cross a puddle. No rainy days in the forecast? Ignite your pupils’ imagination by asking them to create a bridge across a tarpaulin ‘raging river’ or a ‘bubbling lava’ blanket instead!

For this hands-on play-based learning activity, you’ll need a range of small and large materials, such as recycling, scrap construction, materials, natural items, and other loose parts . If you want to test the waters before building bodyweight bridges, you could go small-scale and create a microbridge to hold a 500g bag of sugar or similar.

Download Building Bridges .

3. Body Part Angles

If you’re teaching your pupils about angles, why not encourage them to use their own body as a learning resource?

There is a developmental need within children to move , and this active maths resource looks at different ways to harness that innate playfulness to support better understanding of the mathematical concepts of shape, space, and angles. With Body Part Angles, pupils use their bodies to visualise shapes and angles outdoors in the open space, helping them to gain a new perspective. You could even split the children into teams and let them record the shapes that they make by taking photographs!

Download Body Part Angles .

4. Magic Number Square

Gather sticks, chalk, and a range of small tokens (think fir cones, pebbles, feathers, and conkers) for this fun and educational maths activity.

A magic number square is a grid in which every row, column, and diagonal adds up to the same number – the magic number! It’s a novel way for pupils to problem solve through trial and error, consolidate number bonds, and work as a team.

This outdoor maths activity is brilliant for problem solving and data manipulation – it’s one of our most popular lesson plans!

Download Magic Number Square .

5. Mathematical Scavenger Hunt

Who doesn’t love a scavenger hunt? All you need for this outdoor numeracy activity is a list and an inquisitive mind – something that your classroom will undoubtedly have in abundance!

Write out a scavenger list for your pupils, then give them free reign to explore and discover every item. Not only will this strengthen their understanding of shapes, angles, and symmetry, but it’s also a fantastic means of encouraging independence and focus.

Download Mathematical Scavenger Hunt .

Take your outdoor numeracy practice to the next level

We’re delighted to share that we’ve just launched our new membership plans for schools and individuals. If you’re looking to take outdoor learning and play to the next level, this is the perfect opportunity!

With an LtL membership, you’ll gain access to exclusive resources and discounts – including 25% off one in-person training session for LtL School Members and 50% off online training courses for all LtL Members. LtL School Members will also get exclusive eligibility and support for our new LtL Outdoor Learning & Play Champion School award !

Ready to sign up? Visit our membership page to purchase a membership or compare plans.

For more outdoor learning support, take a look at our school stage hubs for early years , primary , and secondary where you will find everything you need to get outside, including lesson ideas , training , and guidance . Don’t forget to sign up to our newsletter to receive the latest outdoor learning news and opportunities direct to your inbox!

- Lesson Ideas

- Publications

- Work For Us

- Annual Reports

- Our Policies

Ground Floor Clarendon House Monarch Way Winchester SO22 5PW

01962 392932 Email us

Charity No. 803270

1 Beta Centre Stirling University Innovation Park Stirling FK9 4NF

01786 465934 Email us

Charity No. SCO38890

Please fill in the form below and someone from the LTL team will be in touch as soon as possible.

Privacy Overview

Play of the Wild

Education is an admirable thing, but it is well to remember from time to time that nothing that is worth knowing can be taught. -Oscar Wilde

Outdoor Maths Activities KS2 – Teaching Maths Outside

I have put together some fun outdoor maths activities for KS2 to support teaching maths outside. Teaching maths outside is a wonderful way to explore different mathematical ideas and practice learning away from the classroom. It also exposes children to the use of maths in real, hands-on situations, and as well as to problem solve. Children need many opportunities to practice their learning in a range of different situations, in order to make connections and to build on their previous experiences. Building stronger connections helps children to develop a more secure understanding and to build confidence ( Haylock & Cockburn, 2017 ).

I have grouped the activities based on different areas of learning. These activities are primarily aimed at children in KS2 children but can be adapted slightly depending on the children’s ages and experiences. You may also want to see my posts, Outdoor Maths Activities KS1 and Outdoor Maths Activities EYFS .

Number & Place Value

- Ones, tens, thousands & decimal places – Children can represent numbers to thousands (and even decimals) using hula hoops and beanbags. They can also use chalk to draw ones, tens, hundreds, thousands places, or sticks to create a number frame for this purpose. Similarly, rocks or other objects can be used to represent values in number frames. What number does this represent? What would you need to do to make 1 more? 10 more? What about 100 more?

- Ones and tenths with sticks – When children are learning about decimals, they can also use number frames to represent values. A bundle of 10 sticks might represent 1 (whole), and 1 stick might represent .1 (tenth). That way, they can see how a whole is broken up into ten parts (1/10) to make .1. *It’s helpful for children to show that .1 is the same as 1/10. How much is shaded? Can you show me in fractions? How would you write this as a decimal?

- Nim – Nim is a mathematical strategy game where two players take turns removing objects from a pile. Each player must take at least one item per turn. The goal is to either take or avoid taking the last object from the pile. Children can play nim with a pile of sticks or rocks. How many did you pick up? Can you figure out a strategy to win?

- Nature skip counting – Children can practice and show visual counting by 2’s, 3’s, 4’s, 5’s, etc. by using natural objects. They may want to use a tens frame for support. E.g., nuts in pairs (2’s), 3 leaf clover (3’s), 4 leaf clover, flower with 5 petals, etc. They can count the blades on the leaves to help them do this. For example, maple and horse chestnut leaves have 5 blades each so these can be used to count in 5’s. Buttercup and clover leaves have 3 blades so children can use them to count in 3’s. It may be helpful to point out that skip counting is the same as repeated addition or multiplication. How many sets of 2 do you have? How much is that altogether? Can you make a number sentence (equation) to represent this?

- Nature Arrays – Children can make arrays to calculate multiplication problems using pinecones, nuts, rocks, etc. Can you make an array to solve a multiplication problem? Can you make an array and then write a multiplication problem to go with it?

- Nature Algebra – 4 leaves = 16, what does each leaf represent? Children can do outdoor chalk problems & code ‘cracking’. What could you do to solve this problem? What type of arithmetic will you need to solve this?

- Stick Fractions – Children can represent fractions by breaking apart sticks into pieces (half, thirds, quarters, etc.). Children can then see how the different the values of fractions look like relative to one another. Which is larger- 1/3 or 1/2? Can you show me? How many quarters make a half.

- Nature fraction board – Children can create a ‘fraction board’ by drawing a shape (such as a square, rectangle, circle or triangle) that can be divided up in equal pieces (they could do halves, thirds, quarters, etc.). They might also use an old frying pan or baking tray filled with dirt or sand that is divided up by drawing lines or using sticks. Children can represent fractions by shading it in, by scraping it, covering it with objects etc. They can then use numbers to represent the corresponding fraction (and decimals) they have made. How much is shaded? Can you write this as a fraction? How would you write this as a decimal?

- Decimals and fractions with tens frame – Children can use a tens frame to represent fractions and decimals. For example, using rocks, one rock could represent .1 or 1/10 so that 10 rocks = 1 whole. How many squares are covered? Can you write this in a fraction? Can you write this as a decimal?

**See my post, Outdoor Problem Solving Activities for KS2 for problems solving activities that involve arithmetic.

Measurement – Teaching Maths Outside

Volume & capacity.

- Potions – Children can use cylinders, measuring cups and other devices to measure ingredients for making ‘potions’. They might also use weighing scales for ingredients such as nuts, pebbles, etc. Potion making is an opportunity to measure weight and volume/capacity. Can you follow the recipe? Can you create your own recipe? What if you add 15 more ml of water- how much will that be in total?

- Displacement – Children can use measuring cylinders, beakers, or cups to explore how to measure the amount of displacement that results when objects are placed into them. They can find the difference between the original volume and the volume that results when the object is placed in the water. What is the volume of the object? How do you know? Can you write an equation to go with this (hint- use subtraction problem when finding the difference)? Do heavier objects always displace more water than lighter ones? How do you know?

- Rain gauge – Children can measure rainfall using a rain gauge. What is the best unit of measurement? Meters, centimetres, or millimetres? Why? Can you keep track, and compare and chart rainfall on different days including using a bar chart? Can you figure out the total rainfall over a week, fortnight or month?

- Exploring syringes with water play – Can you measure the capacity of the syringes? What instrument might you need to help you? Children can explore the relationship between the size/capacity of the syringe and the distance the water can squirt. How can this be measured?

Length & distance

- Make a meter – Children can estimate 1 meter length by using natural objects (e.g. pinecones, sticks or rocks). They can then use a measuring stick or line to check their work.

- Investigate length and weight – Is it true that the larger the pinecone is, the more that it weighs? Children can use scales to see if larger pinecones always weigh more than smaller ones. *They need to decide how to define large vs small (e.g. is it length, width or circumference)? Children could do a similar investigation with rocks or sticks.

- Plant growth – Children can track the growth of plants. Which plant is growing the fastest? How do you know? Can you find the rate of growth? Can you show your data on a chart?

- Finding the height of a tree – Challenge children to measure or calculate the size of a tree. There are several methods including the shadow & calculation method, triangle method or clinometer method. See if they can try several ways and compare their results.

- Measuring jumps – Children can practice measuring how far they can jump to the nearest centimeter or even millimeter. They can figure out who jumps the farthest and by how much. They could find the difference between their jumps to see how much they improve. Who jumped the farthest? Who improved the most? How do you know?

- Angle hunt – Children could also make a ‘right angle’ out of sticks or a piece of square plastic (preferably transparent). Then they can use their angle to identify objects that have right angles, and also identify objects that have angles greater than 90 degrees (obtuse) or less than 90 degrees (acute). Do right angles exist in nature? How do you know?

- Measuring angles outdoors – Children might use a protractor to measure angles outdoors – e.g. angles of branches, the offshoots of plants, or manmade things such as parts of buildings. What’s the smallest angle you can find? The largest? See the forest triangle activity below.

- Stick angles – Children can compare angles with, their own angles made with sticks (demonstrating acute, right, or obtuse angles). Can you make a right angle? Acute? Obtuse? Can you measure it to find the angle?

- Observing the moon & sun – These are some questions for observation, exploration and investigation: The time when the sun sets and rises– Does this change? How do you know? Where on the horizon do you first/last see the sun or the moon? Does this change from day to day? How do you know? Phases of the moon — How does it change? Do you notice any patterns? Children might make a sundial as part of their exploration.

- Stone stacking – Children can make stone towers and even more intricate balancing formations such as arches. This activity is also an excellent way for older children to explore balance and centre of gravity.

- Investigating Circles – Children can measure circles (such as flower pots, or tree stumps) or other circular objects found outside. They can measure the circumference, radius and diameter, and then investigate the relationship between diameter and circumference.

- Large Sidewalk Chalk Shapes – Children can create a large shape (e.g. a square) with masking tape on the pavement. Next they can use masking tape to make other shapes within the larger shape. Finally, for fun they can colour colour in the shapes using sidewalk chalk to make a large picture. How many / what types of shapes have you made? Can you only make triangles? Why or why not? Can you prove it? What do you notice about your picture?

- Forrest Triangles – Children can use ropes between trees in the forest to create triangles. They can measure and calculate perimeters and even explore the relationships between different triangles that they create. Can you change the shape of the triangle? How can you make a larger or smaller triangle? Can you make one with an obtuse or acute angle?

- Egyptian Triangles – Ancient Egyptians made triangles with right-angles using ropes that were knotted into 12 equal lengths. With a 12 knotted rope, what triangles can you make? *With a knot in each corner, what other regular (equal sided and angled) shapes you can make?

- Draw a circle – Challenge children to figure out how to draw an accurate circle outside (eg with chalk on pavement). What would you need to use to make it look terrific (ex. string)? Can you find a different way?

- Venn diagrams with hoops or circles drawn with chalk – Children can explore different variables. You may want to see my post doing this with leaves.

- See above – Plant growth & rain gauge . Children can create data charts using their measurements of plants or rainfall.

I hope that these outdoor maths activities for KS2 have been helpful and that you get to enjoy teaching some maths lessons outside! Good luck!

References – Outdoor Maths Activities KS2 – Teaching Maths Outside

Haylock & Cockburn (2017). Understanding Mathematics for Young Children (5 th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Arithmetic , Data, Patterns & Sorting , Gardening , Geometry , Maths , Measurement , Natural , Number & Place Value , Rocks , School Age , Sticks

Learning Outdoors , learning outside , outdoor learning

5 thoughts on “ Outdoor Maths Activities KS2 – Teaching Maths Outside ” Leave a comment ›

- Pingback: Active Maths Ideas & Outdoor Maths Games – Play of the Wild

- Pingback: Outdoor learning activities: 57 fun and engaging ideas - Hope Education blog

- Pingback: Outdoor Problem Solving Activities KS2- Learning Maths – Play of the Wild

So many wonderful ideas! I am planning to do more outdoor maths activities with my 3-6 y.o. group. Thanks for the inspiration!

Thank you! Let me know how it goes! I’ve always loved doing outdoor lessons. 🙂 I hope you’re doing well!!

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Advertisement

Outdoor learning and psychological resilience: making today’s students better prepared for tomorrow’s world

- Point and counterpoint

- Published: 01 April 2019

- Volume 39 , pages 67–72, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Tonia Gray 1

2181 Accesses

13 Citations

51 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

American Psychological Association (2010). The road to resilience . Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx .

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) (2017). Curriculum Connections: Outdoor Learning. Retrieved from https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/resources/curriculum-connections/portfolios/outdoor-learning/?searchTerm=outdoor+learning#dimension-content .

Black Dog Institute (2016). Mission Australia Youth Mental Health Report 2012–2016 . https://blackdoginstitute.org.au/docs/default-source/research/evidence-and-policy-section/2017-youth-mental-health-report_mission-australia-and-black-dog-institute.pdf?sfvrsn=6 .

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59 , 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1027/0003-066X.59.1.20 .

Article Google Scholar

Booth, J. (2015). Coping strategies and the development of psychological resilience in outdoor education . Honours Thesis, University of Canberra. http://www.canberra.edu.au/researchrepository/items/4cc8017a-3eef-46d6-8a8b-b410271dc7e2/1/

Boyle, I. (2003). The impact of adventure-based training on team cohesion and psychological skills development in elite sporting teams. (Doctoral Dissertation). Wollongong, Australia: University of Wollongong. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/984/

Braus, J., & Milligan-Toffler, S. (2018). The children and nature connection: Why it matters. Ecopsychology., 10 (4), 193–194. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0072 .

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, I. S. (1990). Adventure and the flow experience. In J. C. Miles & S. Priest (Eds.) Adventure education (pp. 149–155). State College: Venture.

Davies, M. (1996). Outdoors: An important context for young children’s development. Early Child Development and Care, 115 (1), 37–49.

Dickson, T., Gray, T. & Mann, K (2008). Australian Outdoor Adventure Activity Benefits Catalogue https://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:MlcPtL33910J:https://outdoorsvictoria.org.au/resources/australian-outdoor-adventure-activity-benefits-catalogue/+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=au&client=safari .

Dowdell, K., Gray, T., & Malone, K. (2011). Nature and its influence on Children’s outdoor play. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education., 15 (2), 24–35 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF03400925 .

Ewert, A., & Yoshino, A. (2011). The influence of short-term adventure-based experiences on levels of resilience. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 11 , 35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2010.532986 .

Ewing, R. (2018). Exploding some of the myths about learning to read: A review of research on the role of phonics . ISBN 978-0-6482555-6-7 Retrieved from https://www.alea.edu.au/documents/item/1869 .

Gray, T. (1997). The impact of an extended stay outdoor education school program upon adolescent participants. (Doctoral Dissertation). Wollongong, Australia: University of Wollongong. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1799 .

Gray, T. (2017). A 30-year retrospective study of the impact of outdoor education upon adolescent participants: Salient lessons from the field. Pathways the Ontario Outdoor Education Journal, Spring, 29 (3), 4–15.

Google Scholar

Gray, T (2018a). Being in nature is good for learning, here's how to get kids off screens and outside. The Conversation. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/being-in-nature-is-good-for-learning-heres-how-to-get-kids-off-screens-and-outside-104935 .

Gray, T. (2018b). Outdoor learning: Not new, just newly important. Curriculum perspectives . https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-018-0054-x .

Gray, T., & Martin, P. (2012). The role and place of outdoor education in the Australian National Curriculum. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 16 (1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03400937 .

Gray, T., & Perusco, D. (1993). Footprints in the sand—Reflecting upon the value of outdoor education in the school curriculum. Australian Council for Health, Physical Education and Recreation National Journal, 40 (1), 17–21.

Gray, T., & Pigott, F. (2018). Lasting lessons in outdoor learning: A facilitation model emerging from 30 years of reflective practice. Ecopsychology., 10 (4), 195–204. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0036 .

Gray, T. Tracey, D., Truong, S., & Ward, K. (2017). Fostering the wellbeing of students with challenging behaviour and/or emotional needs through Acceptance Commitment Therapy and outdoor learning: Research report. Sydney, New South Wales: Centre for Educational Research, School of Education, Western Sydney University. https://doi.org/10.4225/35/5a961c414081

Gray, T., Truong, S., Reid, C., Ward, K., Singh, M. & Jacobs, M. (2018). Vertical Schools and Green Space: Canvassing the Literature . Western Sydney University. https://doi.org/10.26183/5bd93af6a3ca5 .

Haggerty, R. J., Sherrod, L. R., Garmezy, N., & Rutter, M. (1996). Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions. Cambridge . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Haidt, J. & Paresky, P. (2019). By mollycoddling our children, we're fuelling mental illness in teenagers. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/10/by-mollycoddling-our-children-were-fuelling-mental-illness-in-teenagers?CMP=fb_gu&fbclid=IwAR1PhsqsxrXiYIXcFnT9BOtXtK37AKOJE0-V7XO-zCQojCsSFSyAev6Tp04 (Accessed January 28, 2019).

Hattie, J., Marsh, H. W., Neill, J. T., & Richards, G. E. (1997). Adventure education and outward bound: Out-of-class experiences that make a lasting difference. Review of Educational Research, 67 (1), 43–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170619 .

Hayhurst, J., Hunter, J., Kafka, S., & Boyes, M. (2015). Enhancing resilience in youth through a 10-day developmental voyage. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 15 (1), 40–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2013.843143 .

Henley, J. (2010). Why our children need to get outside and engage with nature. The Guardian , https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2010/aug/16/childre-nature-outside-play-health Accessed 23 July, 2018.

Jew, C. L., & Green, K. E. (1998). Effects of risk factors on adolescents’ resiliency and coping. Psychological Reports, 82 , 675–678. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1998.82.2.675 .

Kahn, P. H., & Kellert, S. R. (2002). Children and nature: Psychological, sociocultural and evolutionary investigations . Cambridge: MIT Press.

Book Google Scholar

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kellert, S. R. (1998). A national study of outdoor wilderness experience, Unpublished report, Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies.

Kellert, S. R. (2005). Building for life: Designing and understanding the human- nature connection . Washington: Island Press.

Kellert, S. R., & Wilson, E. O. (1993). The biophilia hypothesis . Washington: Island Press.

Lloyd, A., Truong, S., & Gray. (2018). Take the class outside! A call for place-based outdoor learning in the Australian primary school curriculum. Curriculum Perspectives, 38 , 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-018-0050-1 .

Louv, R. (2011). The Nature Principle: Human restoration and the end of Nature-Deficit Disorder . Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

Maller, C. J., & Townsend, M. (2006). Children’s mental health and wellbeing and hands- on contact with nature: Perceptions of principals and teachers. International Journal of Learning, 12 (4), 359–372.

Malone, K. (2007). The bubble-wrap generation: Children growing up in walled gardens. Environmental Education Research, 13 (4), 513–527.

Neill, J. T. (2008). Enhancing life effectiveness: The impacts of outdoor education programs . (Unpublished doctoral dissertation), Faculty of Education, University of Western Sydney, NSW, Australia. Retrieved from http://wilderdom.com/wiki/Neill_2008_Enhancing_life_effectiveness:_The_impacts_of_outdoor_education_programs .

Neill, J. T., & Dias, K. L. (2001). Adventure education and resilience: The double-edged sword. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 1 , 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729670185200061 .

Neill, J. T., & Heubeck, B. (1998). Adolescent coping styles and outdoor education: Searching for the mechanisms of change. In. Exploring the boundaries of adventure therapy: International perspectives. Proceedings of the International Adventure Therapy Conference (1st, Perth, Australia, July 1997) . Retrieved from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED424067.pdf .

Neilson, T. & Hansen, K. (2007). Do green areas affect health? Results from a Danish survey on the use of green areas and health indicators. Health and Place, 13(4) 839-850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.02.001 .

Nettles, S. M., & Pleck, J. H. (1996). Risk, resilience, and development: The multiple ecologies of black adolescents in the United States. In R. J. Haggerty, L. R. Sherrod, N. Garmezy, & M. Rutter (Eds.), Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions. (pp. 147–181). Cambridge . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57 , 316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x .

Rutter, M. (1993). Resilience: Some conceptual considerations. Journal of Adolescent Health, 14 , 626–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(93)90196-V .

Rutter, M. (1996). Stress research: Accomplishments and tasks ahead. In R. J. Haggerty, L. R. Sherrod, N. Garmezy, & M. Rutter (Eds.), Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions (pp. 354–385). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rutter, M. (2006). Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 1–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1376.002

Ryan, D., & Gray, T. (1993). Integrating outdoor education into the school curriculum - a case study. International Council for Health, Physical Education . Recreation, 29 (2), 6–13.

Scott, M. (2017). Preparing today’s students for tomorrow’s world. Speech delivered at the Trans Tasman Business Circle, 29 June, 2017. Retrieved From: https://education.nsw.gov.au/our-priorities/innovate-for-the-future/education-for-a-changing-world/thoughts-on-the-future/preparing-todays-students-for-tomorrows-world#The3 . Accessed January 28, 2019.

Selhub, E., & Logan, A. (2012). Your Brain on Nature: The Science of Nature's Influence on Your Health, Happiness and Vitality . Somerset, UK: Wiley.

Sheard, M., & Golby, J. (2006). The efficacy of an outdoor adventure education curriculum on selected aspects of positive psychological development. The Journal of Experimental Education, 29 , 187–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/105382590602900208 .

Shellman, A. (2009). Empowerment and resilience: A multi-method approach to understanding processes and outcomes of adventure education program experiences . (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Indiana University, Indiana, MI, USA. Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/33/54/3354905.html .

Sibthorp, J., Paisley, K., Furman, N., & Gookin, J. (2008). Long-term impacts attributed to participation in wilderness education: Preliminary findings from NOLS. In Ninth Biennial Research Symposium (p. 115).

Skehill, C. M. (2001). Resilience, coping with an extended stay outdoor education program, and adolescent mental health. (Unpublished thesis). University Canberra, Canberra, Australia. Retrieved from http://www.wilderdom.com/pdf/Skehill2001ResilienceCopingOutdoorEducation.pdf

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15 , 194–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705500802222972 .

Steinhardt, M., & Dolbier, C. (2008). Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. Journal of American College Health, 56 , 445–453. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.56.44.445-454 .

Taniguchi, S., & Freeman, P. A. (2004). Outdoor education and meaningful learning: Finding the attributes to meaningful learning experiences in an outdoor education program. The Journal of Experimental Education, 26 , 210–211 Retrieved from http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/164/ .

Townsend, M., & Weerasuriya, R. (2010). Beyond blue to Green: The benefits of contact with nature . Deakin University.

Truong, S., Singh, M., Reid, C., Gray, T., & Ward, K. (2018). Vertical schooling and learning transformations in curriculum research: Points and counterpoints in outdoor education and sustainability. Curriculum Perspectives. https://rdcu.be/5RhP .

Wilson, E. O. (1984). Biophilia . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, E. O. ( 2015). E.O. Wilson Explains Why Parks and Nature are Really Good for Your Brain . The Washington Post. Retrieved From: Http://Www.Childrenandnature.Org/2015 /10/01/E-O-Wilson- Explains-Why-Parks-And-Nature-Are-Really-Good-For-Your-Brain/ .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University, Sydney, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tonia Gray .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gray, T. Outdoor learning and psychological resilience: making today’s students better prepared for tomorrow’s world. Curric Perspect 39 , 67–72 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-019-00069-1

Download citation

Published : 01 April 2019

Issue Date : 15 April 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-019-00069-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Outdoor education

- Outdoor learning

- Coping skills

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Curriculum-based outdoor learning for children aged 9-11: A qualitative analysis of pupils’ and teachers’ views

Contributed equally to this work with: Emily Marchant, Charlotte Todd, Sinead Brophy

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Medical School, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

¶ ‡ These authors also contributed equally to this work.

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliation School of Education, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom

Affiliation School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, Swansea University, Swansea, United Kingdom

Affiliation St Thomas Community Primary School, Swansea, United Kingdom

Roles Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Roles Data curation, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- Emily Marchant,

- Charlotte Todd,

- Roxanne Cooksey,

- Samuel Dredge,

- Hope Jones,

- David Reynolds,

- Gareth Stratton,

- Russell Dwyer,

- Ronan Lyons,

- Sinead Brophy

- Published: May 31, 2019

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212242

- See the preprint

- Reader Comments

The relationship between child health, wellbeing and education demonstrates that healthier and happier children achieve higher educational attainment. An engaging curriculum that facilitates children in achieving their academic potential has strong implications for educational outcomes, future employment prospects, and health and wellbeing during adulthood. Outdoor learning is a pedagogical approach used to enrich learning, enhance school engagement and improve pupil health and wellbeing. However, its non-traditional means of achieving curricular aims are not yet recognised beyond the early years by education inspectorates. This requires evidence into its acceptability from those at the forefront of delivery. This study aimed to explore headteachers’, teachers’ and pupils’ views and experiences of an outdoor learning programme within the key stage two curriculum (ages 9–11) in South Wales, United Kingdom. We examine the process of implementation to offer case study evidence through 1:1 interviews with headteachers (n = 3) and teachers (n = 10) and focus groups with pupils aged 9–11 (n = 10) from three primary schools. Interviews and focus groups were conducted at baseline and six months into implementation. Schools introduced regular outdoor learning within the curriculum. This study found a variety of perceived benefits for pupils and schools. Pupils and teachers noticed improvements in pupils’ engagement with learning, concentration and behaviour, as well as positive impacts on health and wellbeing and teachers’ job satisfaction. Curriculum demands including testing and evidencing work were barriers to implementation, in addition to safety concerns, resources and teacher confidence. Participants supported outdoor learning as a curriculum-based programme for older primary school pupils. However, embedding outdoor learning within the curriculum requires education inspectorates to place higher value on this approach in achieving curricular aims, alongside greater acknowledgment of the wider benefits to children which current measurements do not capture.

Citation: Marchant E, Todd C, Cooksey R, Dredge S, Jones H, Reynolds D, et al. (2019) Curriculum-based outdoor learning for children aged 9-11: A qualitative analysis of pupils’ and teachers’ views. PLoS ONE 14(5): e0212242. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212242

Editor: Andrew R. Dalby, University of Westminster, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: January 18, 2019; Accepted: May 21, 2019; Published: May 31, 2019

Copyright: © 2019 Marchant et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data from this research study are not publicly available due to concerns of participant confidentiality. Data from this research study contain information that are identifiable at both the school and individual level. Ethical approval for this research study was granted by the College of Human and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, Swansea University (approval number 070117, email [email protected] ), on the basis that participants’ data was only accessible by the research team. The participants did not consent to having their data publicly available. Requests for access to the data may be directed to the College of Human and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, Swansea University by emailing [email protected] .

Funding: This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/J500197/1] - EM - https://esrc.ukri.org/ and National Centre for Population Health and Wellbeing Research. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

A mutual relationship between health, wellbeing and education exists. Evidence demonstrates that healthier children have higher educational attainment[ 1 ]. This association is mirrored, with research showing the social impact of education on health outcomes throughout the life course[ 1 ]. Thus, investing in a child’s learning has potential in maximising future achievement, employment prospects and health and wellbeing during adulthood. The school setting provides an opportunity to deliver a curriculum that engages children to reach their academic potential and define their future health outcomes and socio-economic pathway, reducing inequalities in health and education.