- University of Michigan Library

- Research Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Search Strategy

- Work with a Search Expert

- Covidence Review Software

- Types of Reviews

- Evidence in a Systematic Review

- Information Sources

Developing an Answerable Question

Creating a search strategy, identifying synonyms & related terms, keywords vs. index terms, combining search terms using boolean operators, a sr search strategy, search limits.

- Managing Records

- Selection Process

- Data Collection Process

- Study Risk of Bias Assessment

- Reporting Results

- For Search Professionals

Validated Search Filters

Depending on your topic, you may be able to save time in constructing your search by using specific search filters (also called "hedges") developed & validated by researchers in the Health Information Research Unit (HiRU) of McMaster University, under contract from the National Library of Medicine. These filters can be found on

- PubMed’s Clinical Queries & Health Services Research Queries pages

- Ovid Medline’s Clinical Queries filters or here

- Embase & PsycINFO

- EBSCOhost’s main search page for CINAHL (Clinical Queries category)

- HiRU’s Nephrology Filters page

- American U of Beirut, esp. for " humans" filters .

- Countway Library of Medicine methodology filters

- InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group Search Filter Resource

- SIGN (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network) filters page

Why Create a Sensitive Search?

In many literature reviews, you try to balance the sensitivity of the search (how many potentially relevant articles you find) & specificit y (how many definitely relevant articles you find ), realizing that you will miss some. In a systematic review, you want a very sensitive search: you are trying to find any potentially relevant article. A systematic review search will:

- contain many synonyms & variants of search terms

- use care in adding search filters

- search multiple resources, databases & grey literature, such as reports & clinical trials

PICO is a good framework to help clarify your systematic review question.

P - Patient, Population or Problem: What are the important characteristics of the patients &/or problem?

I - Intervention: What you plan to do for the patient or problem?

C - Comparison: What, if anything, is the alternative to the intervention?

O - Outcome: What is the outcome that you would like to measure?

Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis.

5-SPICE: the application of an original framework for community health worker program design, quality improvement and research agenda setting.

A well constructed search strategy is the core of your systematic review and will be reported on in the methods section of your paper. The search strategy retrieves the majority of the studies you will assess for eligibility & inclusion. The quality of the search strategy also affects what items may have been missed. Informationists can be partners in this process.

For a systematic review, it is important to broaden your search to maximize the retrieval of relevant results.

Use keywords: How other people might describe a topic?

Identify the appropriate index terms (subject headings) for your topic.

- Index terms differ by database (MeSH, or Medical Subject Headings , Emtree terms , Subject headings) are assigned by experts based on the article's content.

- Check the indexing of sentinel articles (3-6 articles that are fundamental to your topic). Sentinel articles can also be used to test your search results.

Include spelling variations (e.g., behavior, behaviour ).

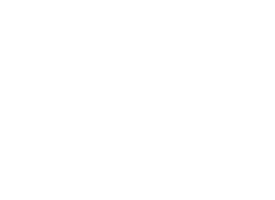

Both types of search terms are useful & both should be used in your search.

Keywords help to broaden your results. They will be searched for at least in journal titles, author names, article titles, & article abstracts. They can also be tagged to search all text.

Index/subject terms help to focus your search appropriately, looking for items that have had a specific term applied by an indexer.

Boolean operators let you combine search terms in specific ways to broaden or narrow your results.

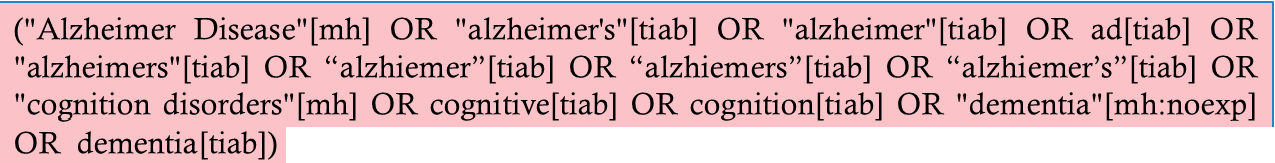

An example of a search string for one concept in a systematic review.

In this example from a PubMed search, [mh] = MeSH & [tiab] = Title/Abstract, a more focused version of a keyword search.

A typical database search limit allows you to narrow results so that you retrieve articles that are most relevant to your research question. Limit types vary by database & include:

- Article/publication type

- Publication dates

In a systematic review search, you should use care when applying limits, as you may lose articles inadvertently. For more information, see, particularly regarding language & format limits. Cochrane 2008 6.4.9

Systematic Reviews

- Introduction

- Review Process: Step by Step

- 1. Planning a Review

- 2. Defining Your Question & Criteria

- 3. Standards & Protocols

Designing Your Search Strategy

Search strategy checklists, pre-search tips, search strategies: filters & hedges, search terms, search strategies: and/or, phrase searching & truncation.

- 5. Locating Published Research

- 6. Locating Grey Literature

- 7. Managing & Documenting Results

- 8. Selecting & Appraising Studies

- 9. Extracting Data

- 10. Writing a Systematic Review

- Tools & Software

- Guides & Tutorials

- Accessing Resources

- Research Assistance

A well designed search strategy is essential to the success of your systematic review. Your strategy should be specific, unbiased, reproducible and will typically include subject headings along with a range of keywords/phrases for each of your concepts.

Your searches should be designed to capture as many studies as possible that meet your criteria.

Chapter 4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions provides detailed guidance for searching and study selection; see Supplement 3.8 Adapting search strategies across databases / sources for translating your search across databases.

Systematic Reviews: Constructing a Search Strategy and Searching for Evidence from the Joanna Briggs Institute provides step-by-step guidance using PubMed as an example database.

General Steps:

- Locate previous/ relevant searches

- Identify your databases

- Develop your search terms and design search

- Evaluate and modify your search

- Document your search ( PRISMA-S Checklist)

- Translate your search for other databases

- Step by Step Systematic Review Search Checklist from MD Anderson Center Library

- PRESS Peer Review Checklist for Search Strategies

Conduct a preliminary set of scoping searches in various databases to test out your search terms (keywords and subject headings) and locate additional terms for your concepts.

Try building a "gold set" of relevant references to help you identify search terms. Sources for this gold set may include:

- Recommended key papers

- Papers by known authors in the field

- Results of preliminary searches from key databases such

- Reviewing references and "cited by" articles lists for key papers

- Articles that have been published in authoritative journals

Hedges/ Filters

- PubMed Special Queries

Hedges are search strings created by experts to help you retrieve specific types of studies or topics; a hedge will filter your results by adding specific search terms, or specific combinations of search terms, to your search.

Hedges can be good starting points but you may need to modify the search string to fit your research. Resources for hedges:

- University of Texas, School of Public Health (study type)

- McMaster University Health Information Research Unit

- The InterTASC Information Specialists' Sub-Group Search Filter Resource

- Pubmed Search Strategies blog

- PubMed Special Queries Topic-Specific PubMed Queries; includes keyword and search strategy examples.

Example: Health Disparities & Minority Health Search Strategies

- Subject Headings

- Keywords Vs. Subject Headings

- Locating Subject Headings

- Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Keyword & Subject Headings Logic Grid

You can use your PICOTS concepts as preliminary search terms. The important terms in this question:

In adults , is screening for depression and feedback of results to providers more effective than no screening and feedback in improving outcomes of major depression in primary care settings?

...might include:

Major depression

Primary Care

(From Lackey, M. (2013). Systematic reviews: Searching the literature [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://guides.lib.unc.edu/ld.php?content_id=258919 )

Your search will include both keywords and subject headings. Controlled vocabulary systems, such as the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) or Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) , use pre-set terms that are used to tag resources on similar subjects. See boxes below for more information on finding and using subject terms.

Not all databases will have subject heading searching and for those that do, the subject heading categories may differ between databases. This is because databases classify articles using different criteria.

Using the keywords from our example, here are some MeSH terms for:

Adults : Adult (A person having attained full growth or maturity. Adults are of 19 through 44 years of age. For a person between 19 and 24 years of age, YOUNG ADULT is available.)

Screening : Mass Screening (Organized periodic procedures performed on large groups of people for the purpose of detecting disease.)

Major depression : Depressive Disorder, Major (Marked depression appearing in the involution period and characterized by hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, and agitation.)

Here is a LCSH subject term for:

Depression : Depression, mental (Dejection ; Depression, Unipolar ; Depressive disorder ; Depressive psychoses ; Melancholia ; Mental depression ; Unipolar depression)

- Most EBSCO databases have a tool to help you discover subject terms . See Academic Search Complete > Subject Terms and Academic Search Complete > Subject Terms: Thesaurus

- Most ProQuest databases have a tool to help you discover subject terms: See PsycInfo > Thesaurus

- When you find a useful article, look at the article's Subject Headings (or Subject or Subject Terms) , and record them as possible terms to use in a subject term search.

Here is an example of the subject terms listed for a systematic review found in PsycINFO, " Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force " (2016).

MeSH are standardized terms that describe the main concepts of PubMed/MedLine articles. Searching with MeSH can increase the precision of your search by providing a consistent way to retrieve articles that may use different terminology or spelling variations.

Note: new articles will not have MeSH terms; the indexing process may take up to a few weeks for newly ingested articles.

Use the MeSH database to locate and build a search using MeSH.

To search the MeSH database:

- Search for 1 concept at a time.

- If you do not see a relevant MeSH in the results, search again with a synonym or related term.

- Click on the MeSH term to view to the complete record, subheadings, broader and narrower terms.

Build a search from the results list or from the MeSH term record to specify subheadings.

- Select the box next to the MeSH term or subheadings that you wish to search and click Add to Search Builder.

- You may need to switch AND to OR , depending on how you would like to combine terms.

- Repeat the above steps to add additional MeSH terms. When your search is ready, click Search PubMed.

Logic Grid with Keywords and Index Terms or Subject Headings from Systematic Reviews: Constructing a Search Strategy and Searching for Evidence.

Bhuiyan, M. U., Stiboy, E., Hassan, M. Z., Chan, M., Islam, M. S., Haider, N., Jaffe, A., & Homaira, N. (2021). Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine , 39 (4), 667–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.078

- Boolean Logic: AND, OR, NOT

- Phrase Searching " "

- Truncation *

- Proximity Searching

AND, OR, NOT

Join together search terms in a logical manner.

AND - narrows searches, used to join dissimilar terms OR - broadens searches, used to join similar terms

NOT - removes results containing specified keywords

#1 "major depression" AND "primary care"

#2 screen* OR feedback

#3 (screen* OR feedback)

AND “major depression”

AND “primary care”

"major depression" NOT suicide

" " To search for specific phrases, enclose them in quotation marks . The database will search for those words together in that order.

“ primary care ”

“ major depression ”

Truncate a word in order to search for different forms of the same word. Many databases use the asterisk * as the truncation symbol.

Add the truncation symbol to the word screen * to search for screen, screens, screening, etc.

You do have to be careful with truncation. If you add the truncation symbol to the word minor* , the database will search for minor, minors, minority, minorities, etc.

Not all databases support proximity searching. You can use these strategies in ProQuest databases such as Sociological Abstracts .

pre/# is used to search for terms in proximity to each other in a specific order; # is replaced with the number of words permitted between the search terms.

Sample Search: parent* pre/2 educational (within 2 words & in order )

- This would retrieve articles with no more than two words between parent* and educational (in this order) e.g. " Parent practices and educational achievement" OR " Parents on Educational Attainment" OR " Parental Values, Educational Attainment" etc.

w/# is used to search for terms in proximity to each other in any order ; # is replaced with the number of words permitted between the search terms.

Sample Search: parent* w/3 educational (within 3 words & in any order )

- This would retrieve articles with no more than three words between parent* and educational (in any order) e.g. "Educational practices of parents" OR "Parents value motivation and education" OR "Educational attainments of Latino parents"

- << Previous: 3. Standards & Protocols

- Next: 5. Locating Published Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/systematic-reviews

Covidence website will be inaccessible as we upgrading our platform on Monday 23rd August at 10am AEST, / 2am CEST/1am BST (Sunday, 15th August 8pm EDT/5pm PDT)

How to write a search strategy for your systematic review

Home | Blog | How To | How to write a search strategy for your systematic review

Practical tips to write a search strategy for your systematic review

With a great review question and a clear set of eligibility criteria already mapped out, it’s now time to plan the search strategy. The medical literature is vast. Your team plans a thorough and methodical search, but you also know that resources and interest in the project are finite. At this stage it might feel like you have a mountain to climb.

The bottom line? You will have to sift through some irrelevant search results to find the studies that you need for your review. Capturing a proportion of irrelevant records in your search is necessary to ensure that it identifies as many relevant records as possible. This is the trade-off of precision versus sensitivity and, because systematic reviews aim to be as comprehensive as possible, it is best to favour sensitivity – more is more.

By now, the size of this task might be sounding alarm bells. The good news is that a range of techniques and web-based tools can help to make searching more efficient and save you time. We’ll look at some of them as we walk through the four main steps of searching for studies:

- Decide where to search

- Write and refine the search

- Run and record the search

- Manage the search results

Searching is a specialist discipline and the information given here is not intended to replace the advice of a skilled professional. Before we look at each of the steps in turn, the most important systematic reviewer pro-tip for searching is:

Pro Tip – Talk to your librarian and do it early!

1. decide where to search .

It’s important to come up with a comprehensive list of sources to search so that you don’t miss anything potentially relevant. In clinical medicine, your first stop will likely be the databases MEDLINE , Embase , and CENTRAL . Depending on the subject of the review, it might also be appropriate to run the search in databases that cover specific geographical regions or specialist areas, such as traditional Chinese medicine.

In addition to these databases, you’ll also search for grey literature (essentially, research that was not published in journals). That’s because your search of bibliographic databases will not find relevant information if it is part of, for example:

- a trials register

- a study that is ongoing

- a thesis or dissertation

- a conference abstract.

Over-reliance on published data introduces bias in favour of positive results. Studies with positive results are more likely to be submitted to journals, published in journals, and therefore indexed in databases. This is publication bias and systematic reviews seek to minimise its effects by searching for grey literature.

2. Write and refine the search

Search terms are derived from key concepts in the review question and from the inclusion and exclusion criteria that are specified in the protocol or research plan.

Keywords will be searched for in the title or abstract of the records in the database. They are often truncated (for example, a search for therap* to find therapy, therapies, therapist). They might also use wildcards to allow for spelling variants and plurals (for example, wom#n to find woman and women). The symbols used to perform truncation and wildcard searches vary by database.

Index terms

Using index terms such as MeSH and Emtree in a search can improve its performance. Indexers with subject area expertise work through databases and tag each record with subject terms from a prespecified controlled vocabulary.

This indexing can save review teams a lot of time that would otherwise be spent sifting through irrelevant records. Using index terms in your search, for example, can help you find the records that are actually about the topic of interest (tagged with the index term) but ignore those that contain only a brief mention of it (not tagged with the index term).

Indexers assign terms based on a careful read of each study, rather than whether or not the study contains certain words. So the index terms enable the retrieval of relevant records that cannot be captured by a simple search for the keyword or phrase.

Use a combination

Relying solely on index terms is not advisable. Doing so could miss a relevant record that for some reason (indexer’s judgment, time lag between a record being listed in a database and being indexed) has not been tagged with an index term that would enable you to retrieve it. Good search strategies include both index terms and keywords.

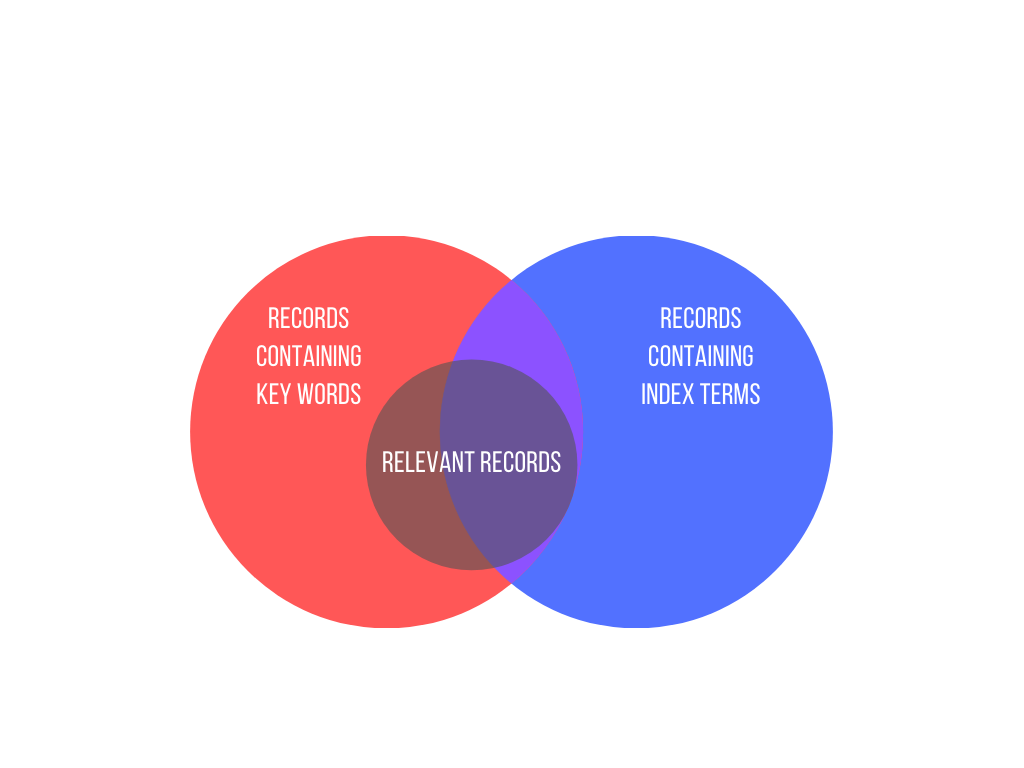

Let’s see how this works in a real review! Figure 2 shows the search strategy for the review ‘Wheat flour fortification with iron and other micronutrients for reducing anaemia and improving iron status in populations’. This strategy combines index terms and keywords using the Boolean operators AND, OR, and NOT. OR is used first to reach as many records as possible before AND and NOT are used to narrow them down.

- Lines 1 and 2: contain MeSH terms (denoted by the initial capitals and the slash at the end).

- Line 3: contains truncated keywords (‘tw’ in this context is an instruction to search the title and abstract fields of the record).

- Line 4: combines the three previous lines using Boolean OR to broaden the search.

- Line 11: combines previous lines using Boolean AND to narrow the search.

- Lines 12 and 13: further narrow the search using Boolean NOT to exclude records of studies with no human subjects.

Writing a search strategy is an iterative process. A good plan is to try out a new strategy and check that it has picked up the key studies that you would expect it to find based on your existing knowledge of the topic area. If it hasn’t, you can explore the reasons for this, revise the strategy, check it for errors, and try it again!

3. Run and record the search

Because of the different ways that individual databases are structured and indexed, a separate search strategy is needed for each database. This adds complexity to the search process, and it is important to keep a careful record of each search strategy as you run it. Search strategies can often be saved in the databases themselves, but it is a good idea to keep an offline copy as a back-up; Covidence allows you to store your search strategies online in your review settings.

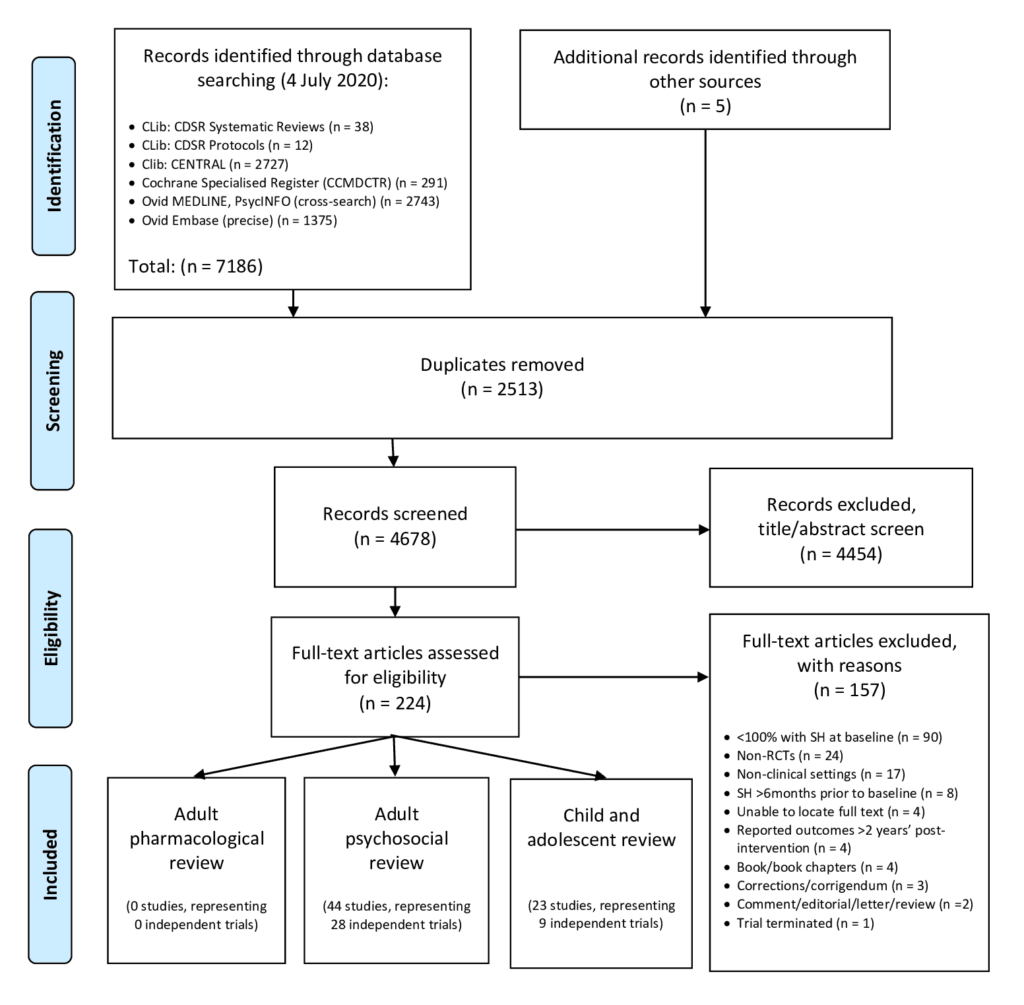

The reporting of the search will be included in the methods section of your review and should follow the PRISMA guidelines. You can download a flow diagram from PRISMA’s website to help you log the number of records retrieved from the search and the subsequent decisions about the inclusion or exclusion of studies. The PRISMA-S extension provides guidance on reporting literature searches.

It is very important that search strategies are reproduced in their entirety (preferably using copy and paste to avoid typos) as part of the published review so that they can be studied and replicated by other researchers. Search strategies are often made available as an appendix because they are long and might otherwise interrupt the flow of the text in the methods section.

4. Manage the search results

Once the search is done and you have recorded the process in enough detail to write up a thorough description in the methods section, you will move on to screening the results. This is an exciting stage in any review because it’s the first glimpse of what the search strategies have found. A large volume of results may be daunting but your search is very likely to have captured some irrelevant studies because of its high sensitivity, as we have already seen. Fortunately, it will be possible to exclude many of these irrelevant studies at the screening stage on the basis of the title and abstract alone 😅.

Search results from multiple databases can be collated in a single spreadsheet for screening. To benefit from process efficiencies, time-saving and easy collaboration with your team, you can import search results into a specialist tool such as Covidence. A key benefit of Covidence is that you can track decisions made about the inclusion or exclusion of studies in a simple workflow and resolve conflicting decisions quickly and transparently. Covidence currently supports three formats for file imports of search results:

- EndNote XML

- PubMed text format

- RIS text format

If you’d like to try this feature of Covidence but don’t have any data yet, you can download some ready-made sample data .

And you’re done!

There is a lot to think about when planning a search strategy. With practice, expert help, and the right tools your team can complete the search process with confidence.

This blog post is part of the Covidence series on how to write a systematic review.

Sign up for a free trial of Covidence today!

[1] Witt KG, Hetrick SE, Rajaram G, Hazell P, Taylor Salisbury TL, Townsend E, Hawton K. Pharmacological interventions for self‐harm in adults . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD013669. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD013669.pub2. Accessed 02 February 2021

Laura Mellor. Portsmouth, UK

Perhaps you'd also like....

Top 5 Tips for High-Quality Systematic Review Data Extraction

Data extraction can be a complex step in the systematic review process. Here are 5 top tips from our experts to help prepare and achieve high quality data extraction.

How to get through study quality assessment Systematic Review

Find out 5 tops tips to conducting quality assessment and why it’s an important step in the systematic review process.

How to extract study data for your systematic review

Learn the basic process and some tips to build data extraction forms for your systematic review with Covidence.

Better systematic review management

Head office, working for an institution or organisation.

Find out why over 350 of the world’s leading institutions are seeing a surge in publications since using Covidence!

Request a consultation with one of our team members and start empowering your researchers:

By using our site you consent to our use of cookies to measure and improve our site’s performance. Please see our Privacy Policy for more information.

- Search this site

- Systematic literature review

- Narrative Review

- Scoping Review

- Systematic Review

- Rapid Review

- Research question

Building your search string

- Optimal use of a literature database

- Fine-tuning your query

- Additional search methods

- Applications for literature review

- Support & contact

Combining keywords with Boolean operators

Conducting a good search requires a bit more than just putting single search terms in a search bar. In order to retrieve specific and targeted information about your topic, you need to logically combine search terms with each other. To do that, you use Boolean operators:

- AND: if you are looking for references in which both search terms appear;

- OR: if you are looking for references containing at least one of the search terms;

- NOT: if you are looking for references in which a particular search term does not occur.

Note: Be careful when using NOT; it may exclude relevant articles by inadvertently (false negatives). A suggestion here is: run the search with and without the NOT, and see the difference by comparing the results in your Search History: how many results are omitted? Are the results that are omitted relevant to your search or not? Based on this, you can decide whether or not the NOT is a useful addition to your search string.

How to build a search string:

- collect search terms and keywords by subtopic;

- combine them with OR;

- place the keywords between parentheses;

- put an AND between the subtopics

Generic example: (... OR ... OR ... OR ... OR ...) AND (... OR ... OR ... OR ...) AND (... OR ... OR ... OR ... OR ...)

With this, you have created a basic search string that you can use for multiple databases. For some databases, you can fine-tune the search string by adding thesaurus terms and/or search fields (see below).

More tips and suggestions

Several techniques exist for fine-tuning your search string. Note that databases often have their own 'rules'. It is advisable to check per database which 'rules' apply to the syntax of your query. These can be found in the HELP or FAQ section of the database in question.

Exact word combination If you only want to find search results that contain the search terms in exactly that order, place your search terms inside double quotation marks ("....."), e.g. "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder."

Pro tip: an exact word combination is actually a strict version of the Boolean AND operator, where the search terms must also occur in that particular order. Therefore, the order of the search terms is not arbitrary, but set by you.

Truncation is a technique that can be used to expand your search; the end of a search term is replaced by a truncation mark, also known as a wildcard. Doing so allows you to efficiently find word variants and thus expand your search. For example:

- child* = child, children, childhood, childhood, child-friendly, childs, child-like

- industr* = industry, industries, industrial

- genetic* = genetic, genetics

Truncation symbols may vary by database, but frequently used symbols include *, !, ? or #.

A wildcard is a symbol that replaces a letter of a word. This is especially useful when a word can be spelled several ways (but mean the same thing), such as in a British variant as an American variant. For example

- wom!n = woman, women

- colo?r = color, color

- latin?= latina, latinx, latine, latino, latines

Search fields When you enter your basic search string into the search bar, your search terms will generally be checked to see if they appear anywhere in the text of the article. This can potentially create a lot of noise. Limiting your search to a to specific search fields will make it more focused. Advanced Search allows you to search only certain fields, e.g. title and/or abstract, keywords, or subject.

For example, "language development disorder"[abstract] AND "primary school"[abstract] AND "teaching materials"[abstract].

Note that each database has its own configuration and search fields, so always tailor your search to the database!

Minilecture Smart search

Useful links and resources

- Useful links

See this link for a great visualization of a search string from a scoping paper .

If you have questions, please contact the Information Specialist Research of your research center , or go to support & contact for more information and advice.

[anchornavigation]

University of Tasmania, Australia

Systematic reviews for health: building search strategies.

- Handbooks / Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Standards for Reporting

- Registering a Protocol

- Tools for Systematic Review

- Online Tutorials & Courses

- Books and Articles about Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Critical Appraisal

- Library Help

- Bibliographic Databases

- Grey Literature

- Handsearching

- Citation Tracking

- 1. Formulate the Research Question

- 2. Identify the Key Concepts

- 3. Develop Search Terms - Free-Text

- 4. Develop Search Terms - Controlled Vocabulary

- 5. Search Fields

- 6. Phrase Searching, Wildcards and Proximity Operators

- 7. Boolean Operators

- 8. Search Limits

- 9. Pilot Search Strategy & Monitor Its Development

- 10. Final Search Strategy

- 11. Adapt Search Syntax

- Documenting Search Strategies

- Handling Results & Storing Papers

Building Search Strategies

Building search strategies is part of the search for studies step..

This tab offers a step-by-step guide to developing a search strategy for a systematic review. The theoretical explanation for each of the steps (left column) is supplemented with an example (right column).

It is recommended to work through the steps sequentially, starting with Step 1 .

Steps of Building Search Strategies

These are the steps required when developing a comprehensive search strategy for a systematic review:

1. Formulate the research question

2. Identify the key concepts

3. Develop search terms - free-text terms

4. Develop search terms - controlled vocabulary terms

5. Search fields

6. Phrase searching, wildcards and proximity operators

7. Boolean operators

8. Search limits

9. Pilot search strategy and monitor its development

10. Final search strategy

11. Adapt search syntax for different databases

Templates / Helpsheets

- Template for Systematic Review search

To illustrate each step for developing a search strategy, the example used in the following 11 steps is (with a slight adaptation):

Aromataris, E & Riitano, D 2014, 'Systematic reviews: Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence', AJN The American Journal of Nursing , vol. 114, no. 5, pp. 49-56.

Additional Resources

A subsection of the Evidence-Based Information Special Interest Group (EBI-SIG) with the European Association of Health Information and Libraries (EAHIL) are working on a project to create living open access Library of Search Strategy Resources :

- Library of Search Strategy Resources (LSSR)

SuRe Info is a web resource that provides research-based information relating to information retrieval aspects of producing systematic reviews. The resource is kept up-to-date by an international team of experienced information specialists.

- SuRe Info - Summarised Research in Information Retrieval for HTA

Other Australian universities have developed extensive guides on building search strategies:

- Plan your search strategy (University of Adelaide)

- Systematic reviews: Search strategy (University of Newcastle)

These videos from the Medical Library at Yale University outline how to build search strategies for a systematic review:

- Systematic Searches #4: Building Search Strategies (Part I)

- Systematic Searches #5: Building Search Strategies (Part II)

- Systematic Searches #6: Building Search Strategies (Part III)

- Systematic Searches #7: Building Search Strategies (Part IV)

- Systematic Searches #8: Building Search Strategies (Part V)

- Systematic Searches #9: Using Filters and Hedges

Need More Help? Book a consultation with a Learning and Research Librarian or contact [email protected] .

- << Previous: Citation Tracking

- Next: 1. Formulate the Research Question >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 1:29 PM

- URL: https://utas.libguides.com/SystematicReviews

Systematic Review

- Library Help

- What is a Systematic Review (SR)?

- Steps of a Systematic Review

- Framing a Research Question

Developing a Search Strategy

- Searching the Literature

- Managing the Process

- Meta-analysis

- Publishing your Systematic Review

Workshop materials

- PICO Worksheet

- Search Strategy Example

- Search Strategy Presentation Slides

- Search strings for demo

Find step-by-step instructions on how to develop a search strategy on p. 44

Errors in search strategies

Salvador-Oliván, J. A., Marco-Cuenca, G., & Arquero-Avilés, R. (2019). Errors in search strategies used in systematic reviews and their effects on information retrieval . Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA , 107 (2), 210–221. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2019.567 .

- Search Term Harvesting

- Text Mining Tools

- Search Filters / Hedges

- Documenting

- Blogs & Discussion Lists

Translating search strategies across databases

- ChatGPT Ask ChatGPT using this prompt, "Covert this search into terms appropriate for the [name] database." Further reading: Wang, S., Scells, H., Koopman, B., & Zuccon, G. (2023). Can ChatGPT write a good boolean query for systematic review literature search?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.03495.

- LitSonar Use the Help section for further guidance on how to use this tool (https://litsonar.com/help). Capable of searching eight different databases simultaneously

- Polyglot Use the Polyglot tool to translate search strings from PubMed across multiple databases. Access the tool's tutorial for more information (https://sr-accelerator.com/#/help/polyglot).

- MEDLINE Transpose Use this tool to translate your MEDLINE (PubMed) search to MEDLINE (Ovid) format or vice versa.

- Database Syntax Guide Guide to translating syntax for multiple databases. From Cochrane.

_____________________________________________________________

Take control of your search and turn off Pubmed's Automatic Term Mapping (ATM) ! It will not include all variant terminology and automatically explodes MeSH terms. Not using ATM allows for clearer documentation of the search method.

For more information on Automatic Term Mapping, watch the video below .

Further readings

- Burns, C. S., Nix, T., Shapiro, R. M., & Huber, J. T. (2021). MEDLINE search retrieval issues: A longitudinal query analysis of five vendor platforms. PLoS ONE , 16 (5), e0234221. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234221

- PubMed Pub ReMiner - Text mining for PubMed to look at commonalities between MeSH terms and keywords

- Go PubMed - Text mining tool for PubMed or MeSH terms. This article explains the features of this text mining tool.

- PubVenn - This tool enables you to explore PubMed using venn diagrams. Also, try Search Workbench .

- Yale MeSH Analyzer - Watch this tutorial (7 min.). This tool allows users to enter up to 20 PubMed ID numbers, which it uses to aggregate the metadata from the associated articles into a spreadsheet. For systematic reviews, it is useful in search strategy development to quickly aggregate the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms associated with relevant articles. While it only works for PubMed, it can be useful for developing searches in medical-adjacent fields, such as psychology, nutrition, and animal health.

- NCBI MeSH on Demand identifies MeSH® terms in your submitted text (abstract or manuscript). MeSH on Demand also lists PubMed similar articles relevant to your submitted text.

- HelioBLAST - This tool finds text records that are similar to the submitted query. Your query is searched against the citations (abstract and titles) in Medline/PubMed and the top matching articles are returned in the results.

- Coremine - It is ideal for those seeking an overview of a complex subject while allowing the possibility to "drill down" to specific details. Instructions

- Carrot2 - This tool can automatically organize search results into topics. It can query PubMed and allows boolean searching.

- SWIFT-Review - Desktop text mining tool specific to systematic reviews. To obtain your free license for SWIFT Review, simply browse to the Sciome Software web page to login and/or create your SWIFT-Review account.

- Voyant - General text mining (this is the download). For the web version go to http://voyant-tools.org

- TerMine - General text mining

- JSTOR Text Analyzer - Recommends journal articles in JSTOR relevant to text.

- CREBP-SRA Word Frequency Analyser (WFA) - This tool helps determine which words you should use to construct and refine a search strategy

- Medline Ranker requires a set of known relevant records with PubMed identifiers and a test set of records (e.g. search results from a highly sensitive search). Medline Ranker sorts the records in the test set and presents those that were most similar to the relevant records first. Medline Ranker also provides a list of discriminating terms which discriminate relevant records from non-relevant records.

_________________________________________________________________________

For more information on text mining tools - review and comparison, read the following article:

Paynter, R., Bañez, L. L., Berliner, E., Erinoff, E., Lege-Matsuura, J., Potter, S., & Uhl, S. (2016). EPC methods: an exploration of the use of text-mining software in systematic reviews .

You might limit to a particular publication type in Pubmed. See a full list of Pubmed publication types .

- Cochrane Handbook Part 2, Section 6.4.11 provides search filters to limit to randomized controlled trials in Medline/PubMed, Medline/Ovid, and Embase

- McMaster - Filters by the Hedges team

- PubMed Systematic Review Filter Search Strategy

- Search Filters from Univ. of Texas School of Public Health

Hedges by Topic (in alphabetical order )

- Prady, S. L., Uphoff, E. P., Power, M., & Golder, S. (2018). Development and validation of a search filter to identify equity-focused studies: Reducing the number needed to screen. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18 (1), 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0567-x

- Health Risk Assessment by Vicky Tessier at the INSPQ

- Effectiveness of Interventions

- van der Mierden, S., Hooijmans, C. R., Tillema, A. H., Rehn, S., Bleich, A., & Leenaars, C. H. (2022). Laboratory animals search filter for different literature databases: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and PsycINFO. Laboratory animals , 56 (3), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/00236772211045485

- Updated Press Checklist (2015) See page 41-42

- IOM Standards for Systematic Reviews

- PRESS Checklist

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement . Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 75 , 40-46.

Systematic Literature Review Worksheet

Use the Database Search Log to record your search terms, search strategy and databases searched.

Guidance on Reporting Systematic Reviews

Cochrane strongly encourages that review authors include a study flow diagram as recommended by the PRISMA statement.

- PRISMA Flow Diagram

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator

- PRISMA Checklist

Other checklists include:

- ARRIVE and DSPC for animal studies

- MOOSE - meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology

- STARLITE - general health policy and clinical practice

- TIDier-PHP - population health and policy interventions

Examples of documented search methodologies:

- Full search strategies for all database searches provided in the Appendices:

Bath, P. & Krishnan, K. (2014). Interventions for deliberately altering blood pressure in acute stroke . Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 10.

- A summary of sources searched and keywords used in the Sources section:

McIntyre, S, Taitz, D, Keogh, J, Goldsmith, S, Badawi, N & Blair, E. (2013). A systematic review of risk factors for cerebral palsy in children born at term in developed countries . Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55( 6), 499-508.

- ACRL Systematic Reviews & Related Methods Interest Group [email protected]

- Cindy Schmidt's Blog: PubMed Search Strategies This blog has been created to share PubMed search strategies. Search strategies posted here are not perfect. They are posted in the hope that others will benefit from the work already put into their creation and/or will offer suggestions for improvements.

- MedTerm Search Assist from the University of Pittsburgh By librarians for librarians - A database to share biomedical terminology and strategies for comprehensive searches.

- MLA expert searching discussion list [email protected] - This discussion list often discusses subject strategies and sometimes search filters.

- PRESS Forum This closed wiki-based forum is a place for librarians to request reviews of systematic review search strategies, and to review the searches of others.

- << Previous: Framing a Research Question

- Next: Searching the Literature >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2024 1:44 PM

- URL: https://lib.guides.umd.edu/SR

Systematic Reviews

- The Research Question

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Original Studies

- Translating

- Deduplication

- Project Management Tools

- Useful Resources

- What is not a systematic review?

Search Strings

Systematic review search strings can be incredibly complex. This is why it is fundamental to have an information specialist on the research team. For an example of a systematic review search strategy, please examine the document below to see additional information from M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Library.

- Example Search String in 3 Databases

- Preliminary Search

- Exhaustive Search

- Hand Search

- Contact Experts

A preliminary search is about planning and developing your protocol . It helps the research team understand what the review would/should entail, and the preliminary search will also give an estimate for the time and funding commitment necessary for the investigation. Researchers should assume an exhaustive search will identify about 2-3 times more the number of citations than the preliminary search.

1. Searching for research trends

You need to see a sample of the research trends within the research area. You don’t know the general scope of the literature until you run a preliminary search. You must also sample these results for information for the background and objectives' section in the protocol.

- A sampling of the preliminary results also helps you formulate the research question. The research question must be shaped by the pre-existing literature because enough pre-existing literature must exist in the first place to attempt to answer the research question.

2. Look to see if a systematic or scoping review already exists

- Look to see if someone has already published a systematic/scoping review on your topic. This is again to analyze the research trends, but it is also important to not duplicate work that is already done.

3. Identifying preliminary MeSH/Subject Headings and keywords/keyphrases

You can identify the preliminary MeSH/subject headings, keywords, and key phrases you will need in your exhaustive search strategy. You will have more terms in your final search, but you must identify the basic subject headings and keywords you will need. This is the information that goes in your Search Methods section of your protocol. What goes in this Search Methods section of the protocol are the terms you found during your preliminary searching phase.

4. Getting test articles

- Select 5-10 test articles from the preliminary search to use to test your future, exhaustive search strategy (i.e. the search to get your citations for your review). These 5-10 test articles should be articles that *should* make it to the end of review based on inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- Researchers may have access to journal subscriptions. Being familiar with a journal and finding articles on the team's topic helps to see what research exists. It can help the information specialist find relevant subject headings and keywords for the search strategy. Additionally, the search strategy that is developed should be able to retrieve these articles that are known to directly address the team's research question.

5. Preparatory contacting of experts

- One of t he goals of contacting experts is to identify unregistered studies with unpublished results. It is important to find experts on the research question because they will know what the current climate is on the research topic. Finally, the research team could benefit from this networking for later stages in the review.

The Exhaustive Search

This is the search designed by a librarian trained on how to design searches for systematic reviews. One goal of an exhaustive search is to identify all publications and as much grey literature as possible that meet study requirements. At least three databases should be utilized to conduct an exhaustive search. Another goal is to document and report the exhaustive search in such a way that it can be replicated for updates and reproduced by others after publication. See the Texas Medical Center Library's S.R. Database and Resources Libguide .

Study types and other considerations

There are many things to consider when searching for and identifying the literature relevant to the research question. Researchers should be familiar with the study types and their uses for systematic reviews.

Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs): A study where there is an initial research question, and there are controls for population and the intervention to be studied. 'Randomized' refers to the population participants, where groups are divided into categories that either receive the studied intervention and those who receive the contemporary treatment or placebo.

Dissertations and unpublished research: The importance of searching for dissertations come into play when there is little research on a new or emerging topic. Additionally, within the published research there may already be problematic bias. Searching within these resources again helps reduce bias within the review.

Non-English studies: There may also be geographical bias in studies. It is important to search non-English studies to identify all the relevant literature for a topic.

Hand Search

Hand searching identifies grey literature like conference proceedings, abstracts for posters, and presented papers not indexed in online databases. Sources to hand search include: subject specific professional association websites; included studies' bibliographies; and topic review bibliographies. Hand searching can be done within research centers such as archives that house information resources out of circulation. It is important to document all sources searched by hand. Information regarding the number of hand searched resources used and where resources are located should be reported within the PRISMA Flow Diagram .

1. Clarification of the data

Some systematic reviews involve a meta-analysis. There may be questions regarding the data produced from the study. Contacting experts to clarify data findings helps develop better accuracy and transparency of the information that will be generated from the systematic review.

There are some systematic reviews, which require image analysis. Images that are used within published journals may not be easily synthesized or examined. The quality of the original image published in the journal article could make analysis difficult. Contacting the researchers for the raw data images will help the systematic review team better conduct image synthetization and analysis.

3. New developments

A systematic review can take 1-2 years. After the search strategy is developed the search has to be deduplicated. When a search is reran, some new articles may be retrieved. Being in contact with the experts helps the systematic review team know what other research is out there, so that information can be put into the review for the principle of transparency.

Caveats for searching

It is important to search three to five databases . The databases and how many you choose to search depends on the topic of the systematic review. Ultimately, be sure you consult with a librarian or information specialist before undertaking your searches for studies.

- << Previous: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Next: Original Studies >>

- Last Updated: Oct 12, 2023 12:30 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sph.uth.tmc.edu/SystematicReviews

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: Where to Search

- Get Started

- Exploratory Search

- Where to Search

- How to Search

- Grey Literature

- What about errata and retractions?

- Eligibility Screening

- Critical Appraisal

- Data Extraction

- Synthesis & Discussion

- Assess Certainty

- Share & Archive

This page provides more information about where to search .

The short answer: Search anywhere that may contain information that can answer your research question(s)

Where to search

- Registries & preprints

- Online resources

- Citation searching

- What about Predatory Journals?

Because most research questions suited for a systematic review will be answerable with primary peer-reviewed empirical research , academic journal databases will likely be your team's primary resource.

Identifying Relevant Databases

A great place to start is your institutions' list of databases - VT's A-Z List of Databases - and subject guides - VT's Subject Guides . For a systematic review, it is important to search in several databases relevant to your research questions , which may mean searching in databases outside of your primary discipline.

Subject librarians can help you to find databases appropriate for your topic! Find VT subject librarian contact information in the accompanying Subject Guide . .

Searching Databases

The exact search 'string' you'll use in each database will depend on the database, because the syntax required by each database will vary. However, the search terms you use and any limitations (e.g., language, geographic location) should remain consistent. Before running your search in each database, it is best to develop a base search strategy, troubleshooting in one or two databases.

For more about designing a search string, go to the How to search tab.

Downloading Results from Databases

In a systematic review, you do not determine the relevance of references in the database itself. Instead, download all references yielded by your search into a citation manager . This process allows for more transparency as the exact yield (count and content) from the comprehensive search is documented and the process for determining relevance is systematic and, in theory, replicable.

Download Limits

Please note that the University Libraries and our vendors implement download limits that may be reached when attempting to perform a comprehensive search via EZProxy . We know these limitations can be frustrating, but they are here to protect services for all users. Learn more by visiting our Collections Management Policy Library Guide.

If you encounter problems with these limits, please contact [email protected]

Gusenbauer M, Haddaway NR. Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources . Res Synth Methods. 2020 Mar;11(2):181-217. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1378. Epub 2020 Jan 28. PMID: 31614060; PMCID: PMC7079055

UX Caucus Database Search Tips

Study Registries & Preprint Archives

For a comprehensive search, it's important to locate and include unpublished to the extent possible in order to reduce the risk of missing important emerging information and to avoid risk of publication bias .

Study registries contain unpublished research , which may (or may not) be considered a type of grey literature in your field. Research may be unpublished for several reasons - for example, the research is still in progress or not ready to publish. Sometimes research is unpublished for other reasons, such as negative or null results, or the study was not considered novel (e.g., replications).

Some health-based study (and clinical trial) registeres include:

- clinicaltrials.gov from the US National Libraries of Medicine

- International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTP) from the World Health Organization

- ISRCTN Registry from BCM Springer Nature

- Australian Clinical Trials from the Australian Government

Preprints are studies that have not yet been peer-reviewed and/or published by a journal. Preprints exist to get research into the community more quickly; much of this material ends up going through the formal peer review and publishing process. Note: it is important to match preprints with their subsequent publication(s) and to not duplicate findings in your synthesis.

Some archives to explore include:

Online Resources

It is best practice to supplement primary searching (done in academic databases) by searching other online resources and web browsing. This kind of searching may result in additional primary research and/or grey literature.

Web search engines and specific websites

While general search engines like Google should never be the primary resource for your search, it is a great way to supplement the results of academic database searches. These searches may yield primary research and grey literature .

Companies like Google tailor search results to individual users, which increase the risk of introducing bias, but there are ways to reduce this risk. For example, log out of your account, use 'incognito' mode (or similar), and/or opt for a search engine that doesn't track your data like DuckDuckGo or StartPage .

In contrast to searches in academic databases, it is more often appropriate to apply artificial limits in web searches, as yields tend to be unmanageable. For example, a team may only review the first 200 records (or 20 pages) . Search strings themselves may also need to be refined to accommodate character limits in both general search engines and specific websites. Exactly how to search specific websites will vary. Note that you can also use general search engines to search within specific websites or even types of websites (e.g., government sites by specifying a .gov url).

Resources for web browsing

- Google Scholar Search Tips

- Bulk Downloading from Google Scholar

- Google Syntax Tips (Sheridan College Library Guide)

- Google Custom/Programmable Search ( instructions from WorldBank/IMF Library Guide )

- Set Google Alerts

- MillionShort ( can remove top hits to find what you're missing )

- Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S (2015) The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0138237. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Piasecki, J., Waligora, M., & Dranseika, V. (2018). Google Search as an Additional Source in Systematic Reviews. Science and engineering ethics , 24 (2), 809–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-0010-4

Citation Searching

Citation searching, also referred to as pearl growing, snowballing, and citation chasing , chaining , or tracking, describes two processes:

Backward citation chasing, where reviewers scan work cited by included references and other relevant reviews, and

Forward citation chasing, where reviewers search for references that cit e the references included in your review and other relevant reviews.

In a comprehensive search, we often find existing reviews (e.g., traditional reviews, scoping reviews, restricted/rapid reviews) on the same topic and/or other systematic reviews on similar topics . Though it is not appropriate to synthesize the reviews themselves in your review, be sure to use them in your citation search .

Citation searching applied to included references (references your team has already identified as relevant). As such, this step does not take place until after reviewing the full-Text of included references.

How to citation search?

Citation searching can be done manually (e.g., reviewing full text) and by using bibliographic databases that index both citations and standard bibliographic data. For example, Web of Science Core Collection provided by Clarivate Analytics, Scopus provided by Elsevier, and Google Scholar (for forward citation searching only).

There are also semi-automated tools available to support this stage, such as Citation Chaser and SpiderCite .

Personal Contacts

Contacting relevant authors and other stakeholders can occur during the:

Comprehensive searching phase to collect unpublished research or other grey literature, and

Eligibility screening , critical appraisal , and data extraction phases as follow-up when there is not enough information provided in an original publication to determine relevance, appraise quality, or extract data properly.

Also consider contacting groups, organizations, committees, listservs, etc.

Predatory Journals

"Predatory journals-also called fraudulent, deceptive, or pseudo-journals-are publications that claim to be legitimate scholarly journals but misrepresent their publishing practices. Some common forms of predatory publishing practices include falsely claiming to provide peer review, hiding information about article processing charges, misrepresenting members of the journal's editorial board, and other violations of copyright or scholarly ethics." ( Elmore & Wetson, 2020 )

For more about predatory journals, check out the GRAD 5124 topic 11.4 Issues in Academic Publishing .

Predatory Journals in Systematic Reviews

Given the description above, it's no surprise that whether or not to include and how to include publications from predatory publishers in systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses. However, the poor practices of a publisher does not necessarily mean the research published there was done poorly. There have been a few recommendations set forth over the years.

Poliani, et al. (2020) recommend to:

- determine whether the journal or publisher is part of COPE, DOAJ, OASP, INASP Journals Online Platform, STM (global voice of scholarly publishing), and

- critically appraise reports from uncertain journals or publishers using a tool like Think, Check, Submit

According to Munn, et al., (2021) , "Options for systematic reviewers could include excluding all studies from suspected predatory journals, applying additional strategies to forensically examine the results of studies published in suspected predatory journals, setting stringent search limits , and applying analytical techniques (such as subgroup or sensitivity analyses) to investigate the impact of suspected predatory journals in a synthesis."

And Rice, et al. (2021) suggest to include "(1) detail methods for addressing predatory journal articles a priori in a study protocol , (2) determine whether included studies are published in open access journals and if they are listed in the directory of open access journals, and (3) conduct a sensitivity analysis with predatory papers excluded from the synthesis."

Elmore SA, Weston EH. Predatory Journals: What They Are and How to Avoid Them . Toxicol Pathol. 2020 Jun;48(4):607-610. doi: 10.1177/0192623320920209. Epub 2020 Apr 22. PMID: 32319351; PMCID: PMC7237319.

John D, Polani Chandrasekar R, Lohmann J, Dazy A. Identifying predatory journals in systematic reviews. In: Advances in Evidence Synthesis: special issue Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020;(9 Suppl 1). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD202001

Munn Z, Barker T, Stern C, Pollock D, Ross-White A, Klugar M, Wiechula R, Aromataris E, Shamseer L. Should I include studies from "predatory" journals in a systematic review? Interim guidance for systematic reviewers. JBI Evid Synth. 2021 Jun 28;19(8):1915-1923. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-21-00138. PMID: 34171895.

Rice, D.B., Skidmore, B. & Cobey, K.D. Dealing with predatory journal articles captured in systematic reviews . Syst Rev 10, 175 (2021). https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.vt.edu/10.1186/s13643-021-01733-2

- << Previous: Comprehensive Search

- Next: How to Search >>

- Last Updated: May 6, 2024 11:56 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.vt.edu/SRMA

Systematic Review

- Systematic reviews

Being systematic

Search terms, choosing databases, finding additional resources.

- Search techniques

- Systematically search databases

- Appraisal & synthesis

- Reporting findings

- Systematic review tools

Searching literature systematically is useful for all types of literature reviews!

However, if you are writing a systematic literature review the search needs to be particularly well planned and structured to ensure it is:

- comprehensive

- transparent

These help ensure bias is eliminated and the review is methodologically sound.

To achieve the above goals, you will need to:

- create a search strategy and ensure it is reviewed by your research group

- document each stage of your literature searching

- report each stage of quality appraisal

Identify the key concepts in your research question

The first step in developing your search strategy is identifying the key concepts your research question covers.

- A preliminary search is often done to understand the topic and to refine your research question.

Identify search terms

Use an iterative process to identify useful search terms for conducting your search.

- Brainstorm keywords and phrases that can describe each concept you have identified in your research question.

- Create a table to record these keywords

- Select your keywords carefully

- Check against inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Repeated testing is required to create a robust search strategy for a systematic review

- Run your search on your primary database and evaluate the first page of records to see how suitable your search is

- Identify reasons for irrelevant results and adjust your keywords accordingly

- Consider whether it would be useful to use broader or narrower terms for your concepts

- Identify keywords in relevant results that you could add to your search to retrieve more relevant resources

Using a concept map or a mind map may help you clarify concepts and the relationships between or within concepts. Watch these YouTube videos for some ideas:

- How to make a concept map (by Lucidchart)

- Make sense of this mess world - mind maps (by Sheng Huang)

Example keywords table:

Research question: What is the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and depression in mothers during the perinatal period?

Revise your strategy/search terms until :

- the results match your research question

- you are confident you will find all the relevant literature on your topic

See Creating search strings for information on how to enter your search terms into databases.

Example search string (using Scopus's Advanced search option) for the terms in the above table:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY("advserse childhood experienc*" OR ACE OR "childhood trauma") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY("perinatal depress*" OR "postpartum depress*" OR "postnatal depress*" OR "maternal mental health" OR "maternal psychological distress") AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(mother* OR women*))

See Subject headings for information on including these database specific terms to your search terms.

Systematic reviewers usually use several databases to search for literature. This ensures that the searching is comprehensive and biases are minimised.

Use both subject-specific and multidisciplinary databases to find resources relevant to your research question:

- Subject-specific databases: in-depth coverage of literature specific to a research field.

- Multi-disciplinary databases: literature from many research fields - help you find resources from disciplines you may not have considered.

Check for databases in your subject area via the Databases tab > Find by subject on the library homepage .

Find the key databases that are often used for systematic reviews in this guide.

Test searches to determine database usefulness. You can consult your Liaison Librarians to finalise the list of databases for your review.

Recommendations:

For all systematic reviews we recommend using Scopus , a high-quality, multidisciplinary database:

- Scopus is an abstract and citation database with links to full text on publisher websites or in other databases.

- Scopus indexes a curated collection of high quality journals along with books and conference proceedings.

- Research outputs are across a range of fields - science, technology, medicine, social science, arts and humanities.

For systematic reviews within the health/biomedical field, we recommend including Medline as one of the databases for your review:

MEDLINE (via Ebsco, via Ovid, via PubMed)

- Medline is the National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) article citation database.

- Medline is hosted individually on a variety of platforms (EBSCO, OVID) and comprises the majority of PubMed.

- Articles in Medline are indexed using MeSH headings. See Subject headings for more information on MeSH.

Note: PubMed contains all of Medline and additional citations, e.g. books, manuscripts, citations that predate Medline.

To ensure your search is comprehensive you may need to search beyond academic databases when conducting a systematic review, particularly to find grey literature (literature not published commercially and outside traditional academic sources such as journals).

Google Scholar

Google Scholar contains academic resources across disciplines and sources types. These come from academic publishers, professional societies, online repositories, universities and web sites.

Use Google Scholar

- as an additional tool to locate relevant publications not included in high-level academic databases

- for finding grey literature such as postgraduate theses and conference proceedings

You can limit your search to the type of websites by using site:ac . nz; site:edu

Note that Google Scholar searches are not as replicable or transparent as academic database searches, and may find large numbers of results.

Other sources of grey literature

- Grey literature checklist (health related grey literature)

- OpenGrey

- Public health Ontario guide to appraising grey literature

- Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS)

- Google search: use it for finding government reports, policies, theses, etc. You can limit your search to a particular type of websites by including site : govt.nz, site: . gov, site: . ac . nz, site: . edu, in your search

Watch our Finding grey literature video (3.49 mins) online.

- << Previous: Planning

- Next: Search techniques >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:49 AM

- URL: https://aut.ac.nz.libguides.com/systematic_reviews

- UNC Libraries

- HSL Academic Process

- Systematic Reviews

- Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

Systematic Reviews: Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

Created by health science librarians.

- Step 1: Complete Pre-Review Tasks

- Step 2: Develop a Protocol

About Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches

Partner with a librarian, systematic searching process, choose a few databases, search with controlled vocabulary and keywords, acknowledge outdated or offensive terminology, helpful tip - building your search, use nesting, boolean operators, and field tags, build your search, translate to other databases and other searching methods, document the search, updating your review.

- Searching FAQs

- Step 4: Manage Citations

- Step 5: Screen Citations

- Step 6: Assess Quality of Included Studies

- Step 7: Extract Data from Included Studies

- Step 8: Write the Review

Check our FAQ's

Email us

Call (919) 962-0800

Make an appointment with a librarian

Request a systematic or scoping review consultation

Search the FAQs

In Step 3, you will design a search strategy to find all of the articles related to your research question. You will:

- Define the main concepts of your topic

- Choose which databases you want to search

- List terms to describe each concept

- Add terms from controlled vocabulary like MeSH

- Use field tags to tell the database where to search for terms

- Combine terms and concepts with Boolean operators AND and OR

- Translate your search strategy to match the format standards for each database

- Save a copy of your search strategy and details about your search

There are many factors to think about when building a strong search strategy for systematic reviews. Librarians are available to provide support with this step of the process.

Click an item below to see how it applies to Step 3: Conduct Literature Searches.

Reporting your review with PRISMA

For PRISMA, there are specific items you will want to report from your search. For this step, review the PRISMA-S checklist.

- PRISMA-S for Searching

- Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used.

- For information on how to document database searches and other search methods on your PRISMA flow diagram, visit our FAQs "How do I document database searches on my PRISMA flow diagram?" and "How do I document a grey literature search for my PRISMA flow diagram?"

Managing your review with Covidence

For this step of the review, in Covidence you can:

- Document searches in Covidence review settings so all team members can view

- Add keywords from your search to be highlighted in green or red while your team screens articles in your review settings

How a librarian can help with Step 3

When designing and conducting literature searches, a librarian can advise you on :

- How to create a search strategy with Boolean operators, database-specific syntax, subject headings, and appropriate keywords

- How to apply previously published systematic review search strategies to your current search

- How to test your search strategy's performance

- How to translate a search strategy from one database's preferred structure to another

The goal of a systematic retrieve is to find all results that are relevant to your topic. Because systematic review searches can be quite extensive and retrieve large numbers of results, an important aspect of systematic searching is limiting the number of irrelevant results that need to be screened. Librarians are experts trained in literature searching and systematic review methodology. Ask us a question or partner with a librarian to save time and improve the quality of your review. Our comparison chart detailing two tiers of partnership provides more information on how librarians can collaborate with and contribute to systematic review teams.

Search Process

- Use controlled vocabulary, if applicable

- Include synonyms/keyword terms

- Choose databases, websites, and/or registries to search

- Translate to other databases

- Search using other methods (e.g. hand searching)

- Validate and peer review the search

Databases can be multidisciplinary or subject specific. Choose the best databases for your research question. Databases index various journals, so in order to be comprehensive, it is important to search multiple databases when conducting a systematic review. Consider searching databases with more diverse or global coverage (i.e., Global Index Medicus) when appropriate. A list of frequently used databases is provided below. You can access UNC Libraries' full listing of databases on the HSL website (arranged alphabetically or by subject ).

Generally speaking, when literature searching, you are not searching the full-text article. Instead, you are searching certain citation data fields, like title, abstract, keyword, controlled vocabulary terms, and more. When developing a literature search, a good place to start is to identify searchable concepts of the research question, and then expand by adding other terms to describe those concepts. Read below for more information and examples on how to develop a literature search, as well as find tips and tricks for developing more comprehensive searches.

Identify search concepts and terms for each

Start by identifying the main concepts of your research question. If unsure, try using a question framework to help identify the main searchable concepts. PICO is one example of a question framework and is used specifically for clinical questions. If your research question doesn't fit into the PICO model well, view other examples of question frameworks and try another!

View our example in PICO format

Question: for patients 65 years and older, does an influenza vaccine reduce the future risk of pneumonia, controlled vocabulary.

Controlled vocabulary is a set of terminology assigned to citations to describe the content of each reference. Searching with controlled vocabulary can improve the relevancy of search results. Many databases assign controlled vocabulary terms to citations, but their naming schema is often specific to each database. For example, the controlled vocabulary system searchable via PubMed is MeSH, or Medical Subject Headings. More information on searching MeSH can be found on the HSL PubMed Ten Tips Legacy Guide .

Note: Controlled vocabulary may be outdated, and some databases allow users to submit requests to update terminology.

View Controlled Vocabulary for our example PICO

As mentioned above, databases with controlled vocabulary often use their own unique system. A listing of controlled vocabulary systems by database is shown below.

Keyword Terms

Not all citations are indexed with controlled vocabulary terms, however, so it is important to combine controlled vocabulary searches with keyword, or text word, searches.

Authors often write about the same topic in varied ways and it is important to add these terms to your search in order to capture most of the literature. For example, consider these elements when developing a list of keyword terms for each concept:

- American versus British spelling

- hyphenated terms

- quality of life

- satisfaction

- vaccination

- influenza vaccination

There are several resources to consider when searching for synonyms. Scan the results of preliminary searches to identify additional terms. Look for synonyms, word variations, and other possibilities in Wikipedia, other encyclopedias or dictionaries, and databases. For example, PubChem lists additional drug names and chemical compounds.

Display Controlled Vocabulary and Keywords for our example PICO

Combining controlled vocabulary and text words in PubMed would look like this:

"Influenza Vaccines"[Mesh] OR "influenza vaccine" OR "influenza vaccines" OR "flu vaccine" OR "flu vaccines" OR "flu shot" OR "flu shots" OR "influenza virus vaccine" OR "influenza virus vaccines"

Social and cultural norms have been rapidly changing around the world. This has led to changes in the vocabulary used, such as when describing people or populations. Library and research terminology changes more slowly, and therefore can be considered outdated, unacceptable, or overly clinical for use in conversation or writing.