- Open access

- Published: 09 August 2022

Risk factors for missed abortion: retrospective analysis of a single institution’s experience

- Wei-Zhen Jiang 1 ,

- Xi-Lin Yang 2 &

- Jian-Ru Luo 1

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology volume 20 , Article number: 115 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

14k Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

To explore the risk factors including the difference between mean gestational sac diameter and crown-rump length for missed abortion.

Hospitalized patients with missed abortion and patients with continuing pregnancy to the second trimester from Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital from June 2018 to June 2021 were retrospectively analyzed. The best cut-off value for age and difference between mean gestational sac diameter and crown-rump length (mGSD-CRL) were obtained by x-tile software. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were adopted to identify the possible risk factors for missed abortion.

Age, gravidity, parity, history of cesarean section, history of recurrent abortion (≥ 3 spontaneous abortions), history of ectopic pregnancy and overweight or obesity (BMI > 24 kg/m 2 ) were related to missed abortion in univariate analysis. However, only age (≥ 30 vs < 30 years: OR = 1.683, 95%CI = 1.017–2.785, P = 0.043, power = 54.4%), BMI (> 24 vs ≤ 24 kg/m 2 : OR = 2.073, 95%CI = 1.056–4.068, P = 0.034, power = 81.3%) and mGSD-CRL (> 20.0vs ≤ 11.7 mm: OR = 2.960, 95% CI = 1.397–6.273, P = 0.005, power = 98.9%; 11.7 < mGSD-CRL ≤ 20.0vs > 20.0 mm: OR = 0.341, 95%CI = 0.172–0.676, P = 0.002, power = 84.8%) were identified as independent risk factors for missed abortion in multivariate analysis.

Patients with age ≥ 30 years, BMI > 24 kg/m 2 or mGSD-CRL > 20 mm had increasing risk for missed abortion, who should be more closely monitored and facilitated with necessary interventions at first trimester or even before conception to reduce the occurrence of missed abortion to have better clinical outcomes.

Missed abortion was a special type of spontaneous abortion that the embryo or fetus has already died but remained in the uterus for days or weeks and with a closed cervical ostium [ 1 ]. Patients might present with or without subtle clinical symptoms such as vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain. Missed abortion, occuring in approximately 8–20% of clinically confirmed intrauterine pregnancies [ 2 ], was often confirmed using ultrasonography.

Missed abortion was undoubtedly a huge physical and psychological setback for women with fertility requirements. Therefore, early identification of women at high risk of missed abortion was pivotal, which might aid in providing possible theoretical basis for implementing clinical measures to prevent missed abortion. Previous studies have revealed that Human Chorionic Gonadotropin(HCG), Estradiol(E2), progesterone, gestational sac diameter(GSD), Crown-Rump Length(CRL), fetal heart rate and yolk sac diameter might be predictive for early pregnancy loss [ 3 , 4 , 5 ] . In addition, the predictive value of mGSD-CRL for early pregnancy outcome in in vitro fertilization(IVF) treatment has been established [ 6 ]. However, most of the current studies have performed univariate analysis to identify the risk factors for early pregnancy loss [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ].

Therefore, we conducted this study to more comprehensively explore the possible high risk factors relating to developing of missed abortion using multivariate logistic regression analysis, hopefully it could be of great help to identification and intervention.

Materials and methods

Data sources.

We reviewed patients from Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital from June 2018 to June 2021. Inclusion criteria of missed abortion group were listed as follows: (1) Not more than 12 weeks gestation; (2) Crown-rump length ≥ seven mm without heartbeat or (3) mean sac diameter ≥ 25 mm without embryo or (4) absence of embryo with heartbeat ≥ two weeks after a scan that showed a gestational sac without a yolk sac or (5) absence of embryo with heartbeat ≥ 11 days after a scan that showed a gestational sac with a yolk sac [ 7 ]. Exclusion criteria of missed abortion group were listed as follows: (1) Incomplete information; (2) multiple pregnancy. Patients with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled as control group: (1) Patients continued pregnancy to the second trimester were included; (2) Incomplete information and multiple pregnancy were excluded. After excluding patients with incomplete information, 307 patients were finally included with 160 patients having missed abortion and 147 with continuing pregnancy to second trimester. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived, but this study was granted by the ethics committee of Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital and the ethics approval number was B2021(26).

Collection of data

Patients’ information regarding age, gravidity, parity, history of vaginal delivery, history of cesarean delivery, history of recurrent abortion (≥ 3 spontaneous abortions), history of induced abortion, history of medication abortion, history of midtrimester induction, history of ectopic pregnancy, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, history of other uterine operations, mode of conception, BMI, mGSD-CRL not more than 12 weeks with live embryo were collected.

Statistical analysis

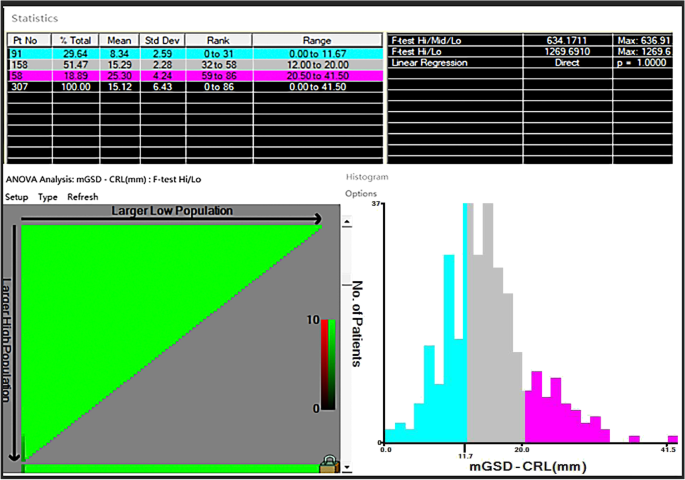

Categorical variables were described as percentages or frequencies and compared using Pearson χ2 test; continues variables were described as medians with interquartile range (IQR) and compared with t test. We identified the cut-off value for age and mGSD-CRL via X-tile software (version 3.6.1; Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA) once maximal chi-square value reached, which was considered to represent the greatest difference in outcomes prediction among the subgroups [ 8 ].

Logistic regression was used to determine independent risk factors for missed abortion. Statistically significant variables from univariate logistic regression analysis ( P < 0.1) were included in the multivariate analysis. Pearson χ2 test, t test and logistic regression were performed using SPSS (version 25.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), X-tile software was uesed to calculate cut-off value. G*Power Analysis program (version 3.1, The G*Power Team, Belgium) was used for power calculation. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was recognized as statistically significant.

Study cohort

A total of 307 patients were finally included in the study with 160 cases having missed abortion and 147 with continuing pregnancy to second trimester (Supplementary Fig. 1 ). The characteristics was listed in Supplementary Table 1 . As a result, 30 years old was the cut-off value for age via X-tile software. Therefore, age was split as age ≥ 30 years and age < 30 years. Similarl y , mGSD-CRL was divided into three subgroups: GSD-CR < 11.7 mm, 11.7 mm ≤ mGSD-CRL ≤ 20.0 mm, GSD-CR > 20.0 mm (Fig. 1 ). Nearly half of the patients were over 30 years old (49.2%). 38.4% of the patients were having first pregnancy, and the majority of the patients had never delivered (71.0%). 11.1% of the patients had a history of vaginal delivery, however, 18.2% of the patients had a history of cesarean section. Of note, 16% of the patients had a BMI > 24 kg/m 2 , 29.6% of the patients had a mGSD-CRL < 11.7 mm and 18.9% had a mGSD-CRL > 20 mm. Moreover, 2.6% of the patients suffering from recurrent abortion and 4.2% had a history of ectopic pregnancy. Besides, 39.1% of the patients had a history of curettage. In total, 52.1% of the patients developed missed abortion (Table 1 ).

mGSD-CRL at diagnosis stratification by X-tile software

Risk factors for missed abortion

In the univariate logistic regression analysis, Age, gravidity, parity, history of cesarean section, history of recurrent abortion, history of ectopic pregnancy, overweight or obesity (BMI > 24 kg/m 2 ) and mGSD-CRL were significantly related to increased risk factors for missed abortion. Furthermore, risk factors identified in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate analysis, which revealed that Age (≥ 30 vs < 30 years: OR = 1.683, 95%CI = 1.017–2.785, P = 0.043, power = 54.4%), BMI (> 24 vs ≤ 24 kg/m 2 : OR = 2.073, 95%CI = 1.056–4.068, P = 0.034, power = 81.3%), mGSD-CRL (> 20.0vs ≤ 11.7 mm: OR = 2.960, 95% CI = 1.397–6.273, P = 0.005, power = 98.9%; 11.7 < mGSD-CRL ≤ 20.0vs > 20.0 mm: OR = 0.341, 95%CI = 0.172–0.676, P = 0.002, power = 84.8%) were independent risk factors for missed abortion (Table 2 ).

Missed abortion, normally presenting without symptoms of threatened abortion such as abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding, was a kind of spontaneous abortion, which were frequently diagnosed using ultrasonography. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the data of 160 missed abortion patients and 147 pregnant women who didn’t have abortion in the first trimester in order to fully establish the possible risk factors for missed abortion, and provide evidence for early identification and intervention for patients with high risk of missed abortion.

In previous studies, it was believed that advanced age was a high risk factor for missed abortion, which might result from the decline of ovarian function and corpus luteum function as age accrued [ 1 , 9 ]. However, previous study also showed that advanced age was not a high risk factor for spontaneous abortion [ 10 ], in which age was divided into advanced age group (> 35 years) and non-advanced age group (≤ 35 years old). Therefore, we hypothesized that there might be a more meaningful cutoff value other than 35 years old to divide the age into two subgroups. As a result, 30 years old, calculated via x-tile, showed significant value in the final multivariate logistic analysis (OR = 1.683, 95%CI = 1.017–2.785, P = 0.043). As controversial regarding age existed in previous studies, our result showing that age > 30 was an independent risk factor for missed abortion seemed solid. And the dropping from 35 to 30 in terms of cut-off value for age might be related to factors like increasing pressure, unhealthy living habits and environmental pollution resulting from social developing [ 2 , 11 ]. Although the cut-off value in our study were not consistent with previous ones, the consensus on older age was a high risk factor for missed abortion was basically reached.

A meta-analysis including 16 studies demonstrated that BMI > 25 kg/m 2 was a high risk factor for abortion [ 12 ], which reported that the missed abortion rate of overweight or obese women was as high as 25–37% [ 13 ]. The participants from our study were childbearing age women from China, so the definition of overweight or obese as BMI > 24 kg/m 2 was used for grouping though the World Health Organization(WHO) defined overweight or obesity as BMI > 25 kg/m 2 [ 14 ]. And the result showed that patients with BMI > 24 kg/m 2 were more likely to have missed abortion than BMI ≤ 24 kg/m 2 (OR = 2.073, 95% CI = 1.056–4.068, P = 0.034), which was consistent with previous studies [ 11 , 12 ]. Therefore, weight control before pregnancy was usually recommended.

Although the effect of mGSD and CRL on missed abortion had been reported [ 3 , 4 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ], there was few studies working on the relationship between mGSD-CRL and missed abortion. Bromley et al.firstly proposed the concept of "small gestational sac" [ 19 ]. And their work revealed that mGSD-CRL < 5 mm in the first trimester was a high risk factor for missed abortion. However, the extremely limited number of included patients in their study might impede the generalization of the conclusion. Similarly, the research from Kapfhamer el also showed that mGSD-CRL < 5 mm was a high risk factor for early pregnancy loss, and further demonstrated that mGSD-CRL > 10 mm was a protective factor for early pregnancy loss [ 6 ]. However, Zhao et al. believed that "large gestational sac"(mGSD-CRL ≥ 18 mm) was related to increasing risk for spontaneous abortion [ 20 ]. Therefore, we used x-tile to find the two optimal cutoff values for mGSD-CRL, which showed that patients with mGSD-CRL > 20 mm was more more likely to have missed abortion than patients with mGSD-CR ≤ 20 mm. And there was no statistical difference between mGSD-CRL < 11.7 mm group and 11.7 ≤ mGSD-CRL ≤ 20.0 mm group. In summary, we were inclined to believe that increasing mGSD-CRL was associated with increasing risk of missed abortion, which should be further validated in the future due to the differences in sample size from previous studies [ 6 , 19 , 20 ].

Age, gravidity, parity, history of cesarean section, history of recurrent abortion, history of ectopic pregnancy, BMI and mGSD-CRL were identified in the univariate analysis. However, only age, BMI and mGSD-CRL were still meaningful in multivariate analysis. What was inconsistent with previous studies in our study was that recurrent abortion was not a high risk factor for missed abortion [ 21 ], which might result from the low incidence of recurrent abortion (missed abortion group vs non-missed abortion group: 7 vs 1) in our study.

One major strength of this study was that stratifying age by x-tile rather than 35 years were firstly recognized for high risk of missed abortion. Other strengths included that mGSD-CRL were analyzed instead of mGSD or CRL independently. On the contrary, This study was inevitably limited by the retrospective nature. In addition, the pathogenic factors for missed abortion was complicated, and some possible high risk factors like immunological or genetic factors could not be obtained.

It is well known that missed abortion is a special type of spontaneous abortion and the ultimate outcome is embryonic arrest. The current knowledge of the missed abortion mostly relates to prevention and treatment, but the classification and severity have not been covered yet according to existing literature and guidelines. The purpose of this paper is to explore the high-risk factors of missed abortion, therefore treatment was barely involved, and we will do more research on the treatment of missed abortion in future work. Overall, We hope that the present study could aid in abortion prediction and treatment decision-making for clinicians.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that age ≥ 30 years old, BMI > 24 kg/m 2 and mGSD-CRL > 20 mm were independent risk factors for missed abortion. This study provided a theoretical basis for clinicians to deliver prompt interventions in childbearing age women during the first trimester or even before pregnancy, so as to reduce the incidence of missed abortion.

Availability of data and material

All data that support the findings of this study were available from the corresponding author via E-mail due to appropriate request.

Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Dashe JS, Hoffman BL, Casey BM, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 25nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2018.

Google Scholar

Fang J, Xie B, Chen B, et al. Biochemical clinical factors associated with missed abortion independent of maternal age: A retrospective study of 795 cases with missed abortion and 694 cases with normal pregnancy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(50):e13573.

Article Google Scholar

Altay MM, Yaz H, Haberal A. The assessment of the gestational sac diameter, crown-rump length, progesterone and fetal heart rate measurements at the 10th gestational week to predict the spontaneous abortion risk. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35(2):287–92.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Papaioannou GI, Syngelaki A, Maiz N, et al. Ultrasonographic prediction of early miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1685–92.

Puget C, Joueidi Y, Bauville E, et al. Serial hCG and progesterone levels to predict early pregnancy outcomes in pregnancies of uncertain viability: A prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;220:100–5.

Kapfhamer JD, Palaniappan S, Summers K, et al. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):130–6.

Doubilet PM, Benson CB, Bourne T, et al. Diagnostic criteria for nonviable pregnancy early in the first trimester. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(15):1443–51.

Zhuang W, Chen J, Li Y, et al. Valuation of lymph node dissection in localized high-risk renal cell cancer using X-tile software. Int Urol Nephrol. 2020;52(2):253–62.

Guifang G, Caixin Y, Yanqing H, et al. A survey of influencing factors of missed abortion during the two-child peak period. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;undefined:1–4.

Yavuz P, Taze M, Salihoglu O. The effect of adolescent and advanced-age pregnancies on maternal and early neonatal clinical data. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2021;undefined:1–7.

Wu J, Hou H, Ritz B, et al. Exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and missed abortion in early pregnancy in a Chinese population. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408(11):2312–8.

Metwally M, Ong KJ, Ledger WL, et al. Does high body mass index increase the risk of miscarriage after spontaneous and assisted conception? A meta-analysis of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(3):714–26.

Hamilton-Fairley D, Kiddy D, Watson H, et al. Association of moderate obesity with a poor pregnancy outcome in women with polycystic ovary syndrome treated with low dose gonadotrophin. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99(2):128–31.

WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:1–253.

Pexsters A, Luts J, Van Schoubroeck D, et al. Clinical implications of intra- and interobserver reproducibility of transvaginal sonographic measurement of gestational sac and crown-rump length at 6–9 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(5):510–5.

Preisler J, Kopeika J, Ismail L, et al. Defining safe criteria to diagnose miscarriage: prospective observational multicentre study. BMJ. 2015;351:4579.

Ouyang Y, Qin J, Lin G, et al. Reference intervals of gestational sac, yolk sac, embryonic length, embryonic heart rate at 6–10 weeks after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):533.

Papaioannou GI, Syngelaki A, Poon LCY, et al. Normal ranges of embryonic length, embryonic heart rate, gestational sac diameter and yolk sac diameter at 6–10 weeks. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2010;28(4):207–19.

Bromley B, Harlow BL, Laboda LA, et al. Small sac size in the first trimester: a predictor of poor fetal outcome. Radiology. 1991;178(2):375–7.

Xuan Z, Liu Lu, Haiqian Li. Clinical Analysis of the Impact of Corpus Luteum, Gestational Sac and Embryo in Early Pregnancy on the Pregnant Outcomes. J Pract Obstetr Gynecolo. 2013;08:595–8.

Li H, Qin S, Xiao F, et al. Predicting first-trimester outcome of embryos with cardiac activity in women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(6):300060520911829.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants, Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital hospital staff, and whoever contributed to this study.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, No.1617 of Riyue Avenue, Qingyang District, Chengdu, 611731, China

Wei-Zhen Jiang & Jian-Ru Luo

Department of Radiation Oncology, Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, 611731, China

Xi-Lin Yang

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conception/design: Wei-Zhen Jiang. Provision of study material or patients: Wei-Zhen Jiang. Collection and/or assembly of data: Wei-Zhen Jiang, Xi-Lin Yang. Data analysis and interpretation: Wei-Zhen Jiang, Xi-Lin Yang. Manuscript writing: Wei-Zhen Jiang. Manuscript revision: Jian-Ru Luo. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jian-Ru Luo .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was waived, but this study was granted by the ethics committee of Chengdu Women's and Children's Central Hospital and the ethics approval number was B2021(26).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that there is on potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: supplementary figure 1..

Flow chart depicting for inclusion of studysubjects. Supplementary Table1. Clinical characteristicsof participants.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Jiang, WZ., Yang, XL. & Luo, JR. Risk factors for missed abortion: retrospective analysis of a single institution’s experience. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 20 , 115 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-022-00987-2

Download citation

Received : 09 January 2022

Accepted : 03 August 2022

Published : 09 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12958-022-00987-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- First trimester pregnancy

- Missed abortion

- Gestational sac

- Crown-rump length

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology

ISSN: 1477-7827

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2017

Misoprostol for medical treatment of missed abortion: a systematic review and network meta-analysis

- Hang-lin Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7882-3072 1 ,

- Sheeba Marwah 2 ,

- Pei Wang 1 ,

- Qiu-meng Wang 1 &

- Xiao-wen Chen 1

Scientific Reports volume 7 , Article number: 1664 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

42 Citations

44 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Drug therapy

- Reproductive disorders

The efficacy and safety of misoprostol alone for missed abortion varied with different regimens. To evaluate existing evidence for the medical management of missed abortion using misoprostol, we undertook a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. The electronic literature search was conducted using PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Embase, EBSCOhost Online Research Databases, Springer Link, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Ovid Medline and Google Scholar. 18 studies of 1802 participants were included in our analysis. Compared with vaginal misoprostol of 800 ug or sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug, lower-dose regimens (200 ug or 400 ug) by any route of administration tend to be significantly less effective in producing abortion within about 24 hours. In terms of efficacy, the most effective treatment was sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug and the least effective was oral misoprostol of 400 ug. In terms of tolerability, vaginal misoprostol of 400 ug was reported with fewer side effects and sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug was reported with more side effects. Misoprostol is a non-invasive, effective medical method for completion of abortion in missed abortion. Sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug or vaginal misoprostol of 800 ug may be a good choice for the first dose. The ideal dose and medication interval of misoprostol however needs to be further researched.

Similar content being viewed by others

Early pregnancy ultrasound measurements and prediction of first trimester pregnancy loss: A logistic model

Pre-eclampsia

Male delayed orgasm and anorgasmia: a practical guide for sexual medicine providers

Introduction.

Missed abortion is defined as unrecognized intrauterine death of the embryo or fetus without expulsion of the products of conception. It constitutes approximately 15% of clinically diagnosed pregnancies 1 . Women experiencing a missed abortion may have no self-awareness due to the lack of obvious symptoms.

With around 95% success rate, surgical evacuation is regarded as the standard treatment for missed abortion, which had been widely performed all over the world in the past 50 years 2 . However, the costs of surgery and hospitalization, as well as the complications associated with surgery and anaesthesia are a major unresolved concern. Besides infection and bleeding, decreased fertility caused by intrauterine adhesions may be unacceptable for women with missed abortion, who have not yet fulfilled their motherhood desires. Some studies have thus suggested that expectant or medical management might be more suitable instead of surgical evacuation 3 , 4 .

Expectant management has been reported with unpredictable success rate ranging from 25–76% 5 , 6 , 7 . Waiting for spontaneous expulsion of the products of conception would waste much time, during which women may suffer uncertainty and anxiety 5 . When additional surgical evacuation is needed owing to failure, they may suffer from an emotional breakdown. It is thus not recommended for missed early miscarriage due to the risks of emergency surgical treatment and blood transfusion 8 .

Misoprostol is a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue which was originally developed to prevent non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs related gastric ulcers. However it has been used for various other indications in obstetrics and gynaecology. Medical management using misoprostol or combined with mifepristone for missed abortion had been widely researched 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 . Some studies have reported that medical treatment with mifepristone and misoprostol in women with missed abortion would increase the incidence of excessive bleeding 11 , 12 , 13 . Apart from this, mifepristone is more expensive which will add to unnecessary expenses.

The efficacy and safety of misoprostol alone for missed abortion was established in many studies 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 . However, route of administration of misoprostol and success rates varied among the studies. It could be given by oral, sublingual or vaginal, while the doses ranged from 100 micrograms to 800 micrograms 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 . The most suitable route and dose of misoprostol for missed abortion is not yet clear. A single dose of 800 micrograms of misoprostol by vaginal or oral for missed abortion was recommended by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 20 . However some studies reported converse opinion, by pointing out that a lower dose or different routes of misoprostol may be equally effective 21 , 22 .

So we evaluated the existing evidence for the medical management of missed abortion using misoprostol, with the hope of finding alternate suitable management strategies for surgical termination, which must be highly effective and with fewer side effects.

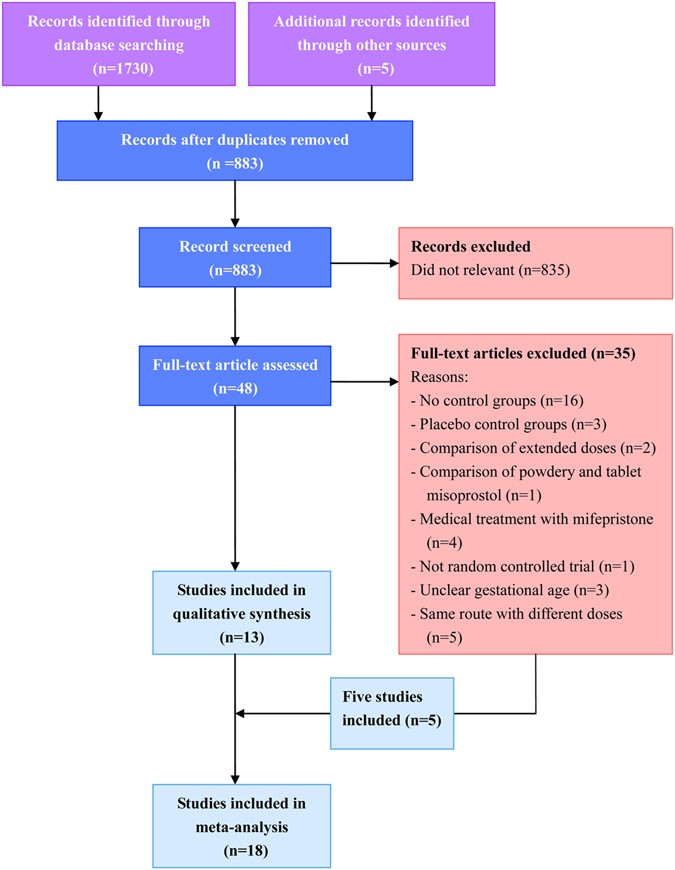

Literature Search

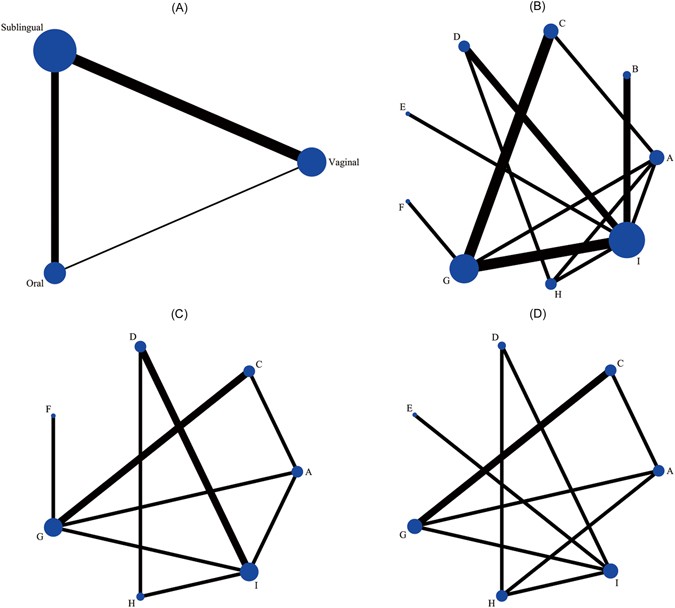

Overall, 1735 articles were identified by the search and 48 potentially eligible articles were retrieved in full text. Of these articles, 35 were excluded for reasons shown in Fig. 1 . The remaining 13 articles met our predefined inclusion criteria. Most of studies compared vaginal route of misoprostol with sublingual or oral route while only one study compared sublingual route with oral route (Fig. 2A ). When it turned to a network meta-analysis, another five articles which compared misoprostol with different doses in the same route were also included in our work. The network diagram of all included studies is shown in Fig. 2B .

Article retrieval and screening.

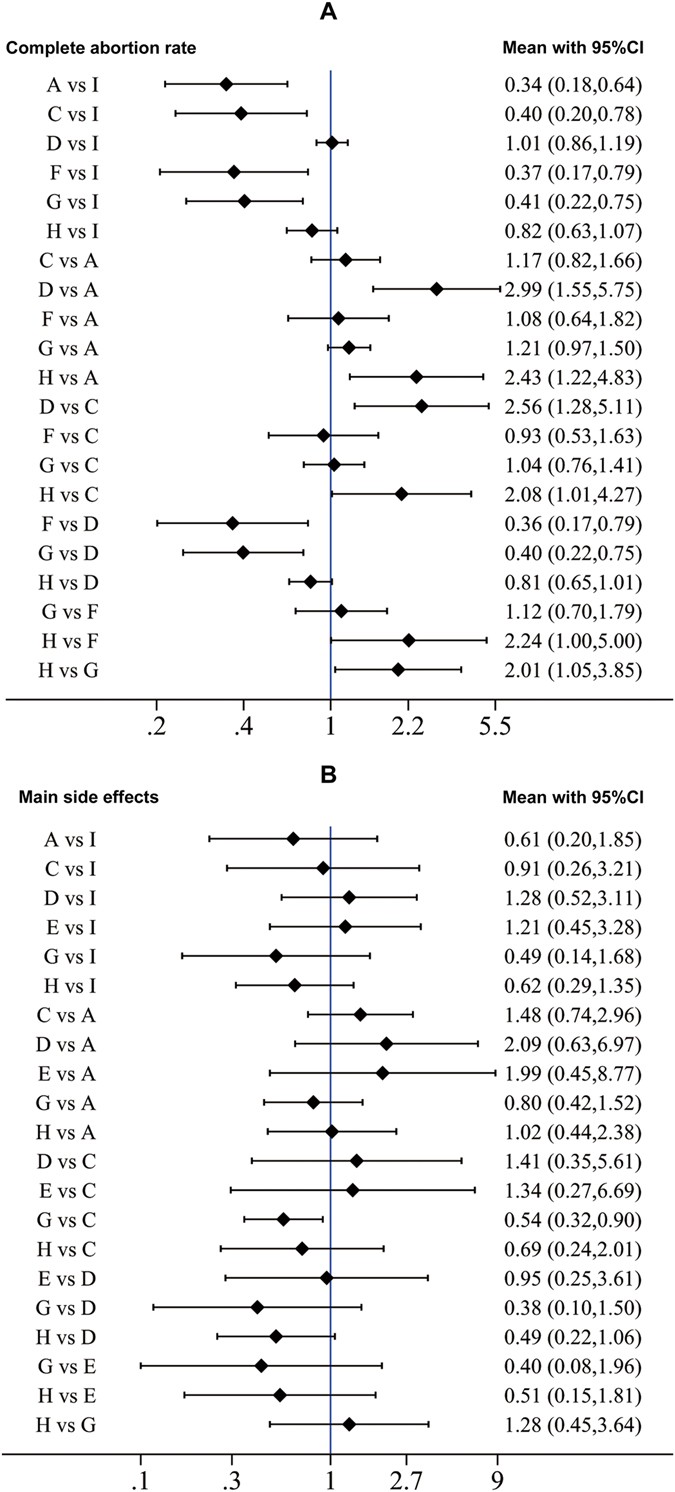

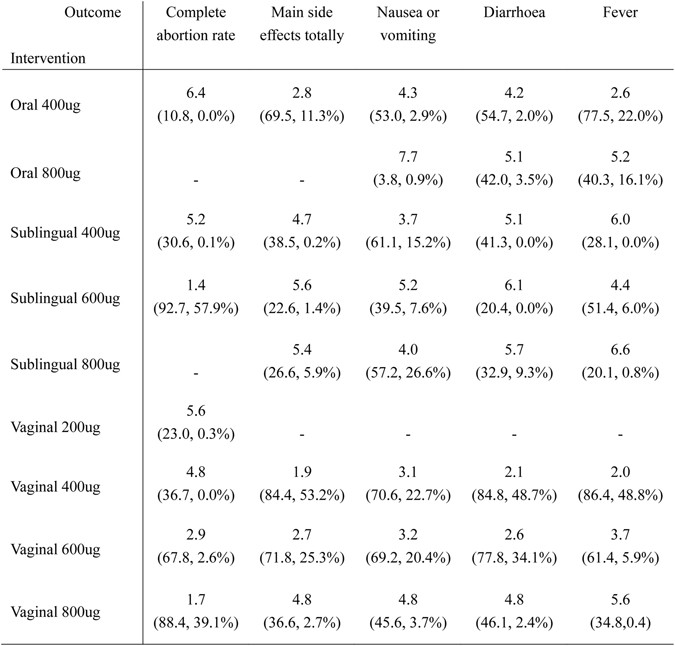

Network diagram of all studies and studies included in analyses of complete abortion rate within about 24 hours and main side effects. ( A ) Studies comparing different routes of misoprostol. ( B ) Studies comparing different routes or doses of misoprostol. ( C ) Complete abortion rate within about 24 hours. ( D ) Main side effects totally. Studies are classified according to the first dose of misoprostol in both groups; The width of the lines is proportional to the number of trials directly comparing each pair of interventions; The size of each node is proportional to the number of trails comparing a single intervention totally. Interventions are sequenced as follows: A. Oral 400 ug; B. Oral 800 ug; C. Sublingual 400 ug; D. Sublingual 600 ug; E. Sublingual 800 ug; F. Vaginal 200 ug; G. Vaginal 400 ug; H. Vaginal 600 ug; I. Vaginal 800 ug.

Study Characteristics

In all, 18 studies of 1802 participants, published between 1999 and 2016, were included in our analysis. The primary characteristics of the studies are tabulated in Supplementary Table S1 . Most of the studies were form India and Thailand. The maximum gestational age of participants in all the studies ranged from 8 weeks to 13 weeks, except one study which reported the outcomes separately according to different trimesters 23 . Interventions in the groups varied in terms of routes, doses and medication intervals and we used the first dose to classify them. In most of studies, complete abortion was defined as complete expulsion of the products of conception without surgical intervention. However in four studies, a less than 15 mm intrauterine tissue diameter on ultrasound scan was taken as the cutof f 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , while one research adopted the criterion for endometrial thickness less than 10 mm 28 . Not all trials reported the same outcomes, especially for the follow-up time. A complete abortion rate within about 24 hours (24 to 28 hours) was mostly mentioned. We calculated it as our primary outcome. There was insufficient data to evaluate for complete abortion rate within 12 hours, 48 hours or 7 days.

For the reported side effects, we could only compare the incidence of nausea or vomiting, diarrhoea and fever. There was insufficient data to analyze other side effects. The mean time taken to abortion was difficult to evaluate due to different follow-up time. For each outcome we have indicated the number of trials contributing data to the network meta-analysis (Fig. 2C and D ). Complete abortion rate within about 24 hours of any intervention and side effects of all the interventions in the analysis are presented in Supplementary Table S2 .

Risk of bias was summarized in Supplementary Table S3 . It was categorized the risk of bias as unclear when no related information reported could be used. Most of the included trials described adequate randomization processes; however most of them were assessed as having an unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment and blinding.

Meta-analysis

The results of the network meta-analysis for the outcomes are presented as forest plots in Fig. 3 . Compared with vaginal misoprostol of 800 ug, lower-dose regimens (200 ug or 400 ug) by any route of administration tend to be significantly less effective in producing abortion within about 24 hours. Similar results can be seen in another comparison with sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug. For the comparison between the two regimens, there is no significant difference (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.19). For the same dose of 600 ug, administration by vaginal route seems to be less effective than sublingual route, however it is not significant (RR 0.81, 95% CI, 0.65 to 1.01). For vaginal misoprostol, doses of 600 ug and 800 ug have no significant differences in producing miscarriage within about 24 hours (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.07). In the analysis of main side effects, significant difference could be seen only in the comparison of vaginal and sublingual misoprostol of 400 ug (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.90). For the same dose of 600 ug, administration by vaginal route seems to accompany with fewer side effects than sublingual route, which is not significant again (RR 0.49, 95% CI, 0.22 to 1.06). In detailed comparison for nausea or vomiting, there were no significant differences observed amongst all the regimens (Supplementary Figure S1 ). For the incidence of diarrhoea, sublingual route seems to be more common than vaginal route with same doses of 600 ug and 400 ug (Supplementary Figure S2 ). For the incidence of fever, sublingual route also seems to be more common than vaginal or oral route with a same dose of 400 ug (Supplementary Figure S3 ).

Network meta-analysis of complete abortion rate within about 24 hours and main side effects. Interventions are sequenced as follows: A. Oral 400 ug; C. Sublingual 400 ug; D. Sublingual 600 ug; E. Sublingual 800 ug; F. Vaginal 200 ug; G. Vaginal 400 ug; H. Vaginal 600 ug; I. Vaginal 800 ug.

Tests of consistency showed that there was no difference between the direct and indirect estimates in all close loops in the analysis of complete abortion rate (Supplementary Figure S4 ). The comparison-adjusted funnel plots of the network meta-analysis for complete abortion rate were not suggestive of any publication bias or small study effect (Supplementary Figure S5 ). The percentage contribution of each direct and indirect comparisons is presented as a table in Supplementary Figure S6 . Inconsistency could be seen in a close loop (sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug, vaginal misoprostol of 600 ug and 800 ug) in the analysis of main side effects (Supplementary Figure S7 ). It was due to the inconsistency in the analysis of nausea or vomiting (Supplementary Figure S8 ). No publication bias or small study effect was found in the analysis of main side effects (Supplementary Figure S9 ).

The results of sensitivity analyses of complete abortion rate were shown in Supplementary Table S4 . In the first sensitivity analysis we excluded one study in which gestational age of the participants was below 8 weeks while in the second we excluded another study in which complete abortion was defined as complete expulsion of the products of conception and endometrial thickness <10 mm. The results were robust for the two sensitivity analyses. When we excluded studies in which only single dose of misoprostol was used in both groups, pre-existed significantly differences disappeared and some of the confidence intervals were wide and across the null line. We reviewed studies related in the close loop with inconsistency, it was impossible to exclude any study for a reasonable argument. In the sensitivity analysis excluding studies with only single dose of misoprostol, the significant difference between vaginal and sublingual misoprostol of 400 ug still existed (Supplementary Table S5 ).

The ranking of interventions based on cumulative probability plots and surfaces under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRAs) is presented in Fig. 4 . In terms of efficacy, the most effective treatment was sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug and the least effective was oral misoprostol of 400 ug. In terms of tolerability, vaginal misoprostol of 400 ug was reported with fewer side effects and sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug was reported with more side effects.

Ranking of all the interventions in network meta-analysis. Information of ranking is located at the intersection of the column-defining outcome and the row-defining intervention; The number in the first row is the ranking of all the interventions; The first number below in brackets is the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) while the second is the probability of the intervention to be the best.

This network meta-analysis represents the most comprehensive synthesis of data for medical treatment using misoprostol for missed abortion. It was found that higher-dose regimens were associated with higher complete abortion rate and more sides effects. Sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug or vaginal misoprostol of 800 ug as the first dose was more effective in producing complete abortion within about 24 hours. However the superiority decreased with multiple doses. It could be explained that a single high-dose of misoprostol might have produced complete abortion in most of women 29 , 30 , 31 . If multiple doses were given, more women with lower-dose misoprostol would convert into complete abortion, which was confirmed by Kovavisarach 30 . We found that the least effective treatment was the oral misopristol of 400 ug. It was due to the liver first-pass effect which greatly reduced the bioavailability of the drug. Alternative routes of administration like vaginal and sublingual avoid the liver first-pass effect because they allow drugs to be absorbed directly into the systemic circulation.

Side effects were most likely to appear in sublingually or orally administered misoprostol. A low dose vaginal misoprostol was reported with the fewest side effects, accompanied by low complete abortion rate 32 . Compared with vaginally or orally administered misoprostol, sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug or 400 ug was associated with more frequent diarrhoea and fever. It was due to the pharmacokinetics of misoprostol, which showed that sublingual misoprostol had the shortest onset of action, the highest peak concentration and greatest bioavailability among the routes of administration 33 .

Vaginal misoprostol of 800 ug was recommend for missed abortion by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence(NICE) and some clinical guidelines 8 , 20 . The results of our meta-analysis lead support to this regimen for medical treatment of missed abortion, however the question of whether sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug is better raises. Apart from this, the incidence of side effects reported was still higher than we expected for these regimens. A variety of methods were researched to increase the efficacy of misoprostol in order to reduce the dose. Some studies discussed the administration of different types of misoprostol, such as gel form and powder form, however the efficacy was not improved 34 , 35 . Some studies discussed the efficacy of moistened misoprostol by acetic acid or normal saline, conclusion was made that vaginal misoprostol either moistened with normal saline or acetic acid was comparable in terms of efficacy and adverse effects 36 , 37 , 38 . Some studies reported different methods to combine misoprostol with laminaria tents or castor oil, however these studies did not focus on the efficacy of these methods to produce abortion for women with missed abortion 39 , 40 .

Limited articles could be found about the efficacy and tolerability of sublingual or oral misoprostol of 800 ug which made us difficult to evaluate. Only in one study it was compared with vaginal misoprostol of 800 ug, the authors found that sublingual misoprostol was as effective as vaginal misoprostol and most side effects were similar in both groups, but heavy bleeding was more common in the sublingual group 41 . Two studies reported that oral misoprostol or vaginal of 800 ug was comparable in terms of efficacy while more side effects were reported in oral misoprostol of 800 ug in one study 42 , 43 . Further research on the efficacy and tolerability of sublingual or oral misoprostol of 800 ug is needed. At present, these regimens should not be regarded as the first-line of medical treatment of missed abortion.

In our work, complete abortion rate was calculated within about 24 hours. Seldom studies reported complete abortion rate within longer follow-up time, they suggested follow-up care to be offered one week following drug administration to ensure the highest success rate 43 , 44 , 45 . Due to the limited amounts of studies, it is difficult to draw any conclusions. The security of waiting at home needs further researched, especially for the incidence of excessive bleeding. For women needed emergency operation, cervical ripening was prepared due to the medical treatment and it is convenient to perform dilatation and curettage 24 , 26 .

Despite the foregoing advantages, serious consideration should be given to the contraindication before planning for medical treatment for women with missed abortion. A missed early miscarriage (<14 weeks of gestation) should be defined by ultrasound findings and suspected ectopic pregnancy must be excluded. Women with unstable hemodynamics, signs of pelvic infections or sepsis also need to be excluded. Detailed medical histories, including the distance between home and hospital, past medical history, previous surgical history, allergic history, medication history, should be recorded. Medical treatment can only be considered in women without following contraindications: known allergy to misoprostol, previous caesarean section, mitral stenosis, hypertension, glaucoma, bronchial asthma, use of non-steroidal drugs and remote areas without hospital around.

All women must be informed of the advantages and disadvantages of surgical and medical treatment. For women who choose medical treatment, hospitalization is not necessary, but the follow-up period will be more important. Pain killers and anti-emetics, such as paracetamol and metoclopramide, should be offered to them as needed 20 . All women should be advised to contact the doctor in case of heavy bleeding or signs of infection. A follow-up visit is recommended to perform within 2 weeks after treatment. Pregnancy test, physical examination of the uterus, and ultrasound should be performed to confirm the status of abortion. In the event of failure, surgical management maybe needed.

One of the strengths of our study is the inclusion of only randomized clinical trial data in a specific population (i.e., women with missed abortion of no more than 14 weeks of gestation). Our meta-analysis included all studies published so far on this topic and statistical tests showed no significant potential publication biases. The protocol of this review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews before the selection of articles.

Limitations of this analysis are obvious. For a net-work meta-analysis, only 18 studies were included in this analysis which might affect the accuracy of the results. For this reason, comparisons could not be performed for some results. Most of the included studies were not double blind. This was therefore a considerable source of bias that may have affected treatment or performance of these women. We classified the interventions according to the first dose, however it is obvious that different max doses or medication intervals will affect the results.

The relation between max doses or medication intervals with complete abortion rate or side effects need to be further researched. Another remaining question is whether there are methods to reduce the incidence of side effects when treated with misoprostol. Further studies should focus on the quality of trails, especially for the blinding of participants and researchers.

In conclusion, misoprostol is a non-invasive, effective medical method for completion of abortion in missed abortion. Sublingual misoprostol of 600 ug or vaginal misoprostol of 800 ug may be a good choice for the first dose. The ideal dose and medication interval of misoprostol however needs to be further researched.

Search strategy and selection criteria

For this meta-analysis, we searched PubMed, the Cochrane Library, Embase, EBSCOhost Online Research Databases, Springer Link, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Ovid Medline and Google Scholar for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published from the date of database inception to August 15th, 2016, comparing different routes of administration of misoprostol in the medical management of missed abortion. We also searched some related journals. No language or publication type limits were applied. The reference lists of selected articles were hand searched to identify any relevant articles. Study authors were contacted to supplement incomplete reports of the original papers. Detailed search strategy can be found in Supplementary Table S6 .

Considering the gestational weeks available for surgical evacuation, women with missed abortion of no more than 14 weeks of gestation who received misoprostol treatment were assessed for inclusion into our meta-analysis. Women with incomplete abortion, threatened abortion or excessive uterine bleeding were excluded. Studies involving medical management with both mifepristone and misoprostol were also excluded.

We considered complete abortion rate for our primary analyses. Complete abortion was defined as complete expulsion of the products of conception without surgical intervention. Our secondary outcome was the side effects of misoprostol reported. The mean induction-abortion time would be also analyzed, if applicable.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers (H-L.W. and P.W.) performed their own search independently. Data extraction and check for accuracy were resolved by other two researchers (Q-M.W. and X.-W.C.). Duplicate or irrelevant articles were excluded by screening of titles and abstracts. All remaining articles were screened in full text. Relevant information from the included trials was extracted with a predefined data extraction sheet. All researchers assessed the risk of bias independently according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 46 . Specifically, attention was focused on seven domains, i.e., random sequence generation, allocation concealment blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of the outcome assessments, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other biases. The review authors’ judgments were categorized as low risk, high risk, or unclear risk of bias. We categorized the risk of bias as unclear when no reported information could be used. The article was reviewed and revised by another researcher (S.M.). Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion within the review team.

Statistical analysis

This study was registered with PROSPERO, number CRD42016046221. The full dataset is available online. After screening of the articles, we found the interventions in included articles were so varied in both the routes and doses of misoprostol that we could not carry out a direct comparison. We chose to perform a network meta-analysis instead. The strategies for data synthesis remained unchanged and the predefined analysis of subgroups with different doses was cancelled.

This network meta-analysis used all the available evidence, both direct and indirect, to evaluate relative effects of different routes or doses of misoprostol 47 , 48 . Statistical analysis was performed with STATA (version 12.0). We used a continuity correction for studies with no events by adding 0.5 to both the events count and the total sample size. We presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous data and the mean difference (MD) for continuous data, both with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Inconsistency between direct and indirect sources of evidence was statistically assessed by calculation of the difference between direct and indirect estimates in all closed loops in the network. Random effects models were used to estimate the inconsistency. If there was no inconsistency between direct and indirect sources of evidence, fixed effects models would be used in further analysis, otherwise random effects models would still be used and sensitivity analyses would be performed to exclude studies with possibilities of causing bias in the close loops. A comparison-adjusted funnel plot was used to detect publication bias and small study effect. We estimated the ranking probabilities for all treatments of being at each possible rank for each intervention and the treatment hierarchy was summarized and presented as surface under the cumulative ranking curve 49 .

Wood, S. L. & Brian, P. H. Medical management of missed abortion: a randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol. 99 , 563–566 (2002).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Joint study of Royal College of general practitioner and Royal College of obstetrician and gynaecologist. Induced abortion operations and their early sequelae. J R Coll Gen Pract . 35 , 175–180 (1985).

Chia, K. V. & Ogbo, V. I. Medical termination of missed abortion. J Obstet Gynaecol. 22 , 184–186, doi: 10.1080/01443610120113382 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Petrou, S., Trinder, J., Brocklehurst, P. & Smith, L. Economic evaluation of alternative management methods of first-trimester miscarriage based on results from the MIST trial. BJOG. 113 , 879–889, doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00998.x (2006).

Jukovic, D., Ross, J. A. & Nicoladies, K. H. Expectant management of missed miscarriage. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 105 , 670–671, doi: 10.1111/bjo.1998.105.issue-6 (1998).

Article Google Scholar

Neilsen, S. & Hahlin, M. Expectant management of first-trimester spontaneous abortion. Lancet. 345 , 84–86, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90060-8 (1995).

Luise, C. et al . Outcome of expectant management of spontaneous first trimester miscarriage: observational study. BMJ. 324 , 873–875, doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.873 (2002).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Huchon, C. et al . Pregnancy loss: French clinical practice guidelines. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 201 , 18–26, doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.015 (2016).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Anderson, J. et al . A randomised controlled trial of oral versus vaginal misoprostol for medical management of early fetal demise. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 107 , S533–S533, doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(09)61912-3 (2009).

Kushwah, D. S., Kushwah, B., Salman, M. T. & Verma, V. K. Acceptability and safety profile of oral and sublingual misoprostol for uterine evacuation following early fetal demise. Indian J Pharmacol. 43 , 306–310, doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.81513 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Leladier, C. et al . Mifepristone (RU 486) induces embryo expulsion in first trimester non-developing pregnancies: a prospective randomised trial. Hum Reprod. 8 , 492–495, doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a138078 (1993).

Gronlund, A. et al . Management of missed abortion: comparison of medical treatment with either mifepristone misoprostol or misoprostol alone with surgical evacuation. A multi-center trial in Copenhagen county, Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 81 , 1060–1065, doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.811111.x (2002).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Nielsen, S., Hahlin, M. & Platz-Christensen, J. J. Unsuccessful treatment of missed abortion with a combination of an antiprogesterone and a prostaglandine E1 analogue. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 104 , 1094–1096, doi: 10.1111/bjo.1997.104.issue-9 (1997).

Tasnee, S., Gul, M. S., Navid, S. & Alam, K. Efficacy and safety of misoprostolin missed miscarriage in terms of blood loss. Rawal Medical Journal 39 , 314–318 (2014).

Google Scholar

Seyam, Y. S., Flamerzi, M. A., Abdallah, M. M. & Ahmed, B. Vaginal misoprostol in the management of first trimester non-viable pregnancy. Qatar Medical Journal. 17 , 14–19 (2007).

Poveda, C. et al . Intrauterine misoprostol: a new high effective treatment of missed abortion. Fertility and Sterility. 76 , S96, doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02284-1 (2001).

Sharma, D., Singhal, S. R. & Rani, X. X. Sublingual misoprostol in management of missed abortion in India. Trop Doct. 37 , 39–40, doi: 10.1258/004947507779952023 (2007).

EI-Sokkary, H. H. Comparison Between Sublingual and Vaginal Administration of Misoprostol in Management of Missed Abortion. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 66 , 24–29, doi: 10.1007/s13224-015-0757-y (2016).

Haberal, A., Celikkanat, H. & Batioglu, S. Oral misoprostol use in early complicated pregnancy. Adv Contracept. 12 , 139–143, doi: 10.1007/BF01849635 (1996).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines. Ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage: diagnosis and initial management. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg154 (2012).

Prasartsakulchai, C. & Tannirandorn, Y. A comparison of vaginal misoprostol 800 microg versus 400 microg in early pregnancy failure: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 87 , S18–23 (2004).

PubMed Google Scholar

Seervi, N. et al . Comparison of different regimes of misoprostol for the termination of early pregnancy failure. Medical Journal Armed Forces India. 70 , 360–363, doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.08.012 (2014).

Shah, N., Azam, S. I. & Khan, N. H. Sublingual versus vaginal misoprostol in the management of missed miscarriage. J Pak Med Assoc. 60 , 113–116 (2010).

Marwah, S. et al . A Comparative Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Vaginal vs Oral Prostaglandin E1 Analogue (Misoprostol) in Management of First Trimester Missed Abortion. J Clin Diagn Res. 10 , Qc14–18, doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18178.7891 (2016).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Akanksha, L., Ramanjeet, K. & Priya, S. A study to compare the clinical outcome of sublingual and vaginal misoprostol in the medical management. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 5 , 491–494 (2016).

Tanha, F. D., Feizi, M. & Shariat, M. Sublingual versus vaginal misoprostol for the management of missed abortion. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 36 , 525–532, doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01229.x (2010).

Rita, G. S. & Kumar, S. A randomised comparison of oral and vaginal misoprostol for medical management of first trimester missed abortion. JK Science 8 , 35–38 (2006).

Ayudhaya, O. P., Herabutya, Y., Chanrachakul, B. & Ayuthaya, N. I. O-Prasertsawat,P. A comparison of the efficacy of sublingual and oral misoprostol 400 microgram in the management of early pregnancy failure: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 89 (Suppl 4), S5–10 (2006).

Hombalegowda, R. B., Samapthkumar, S., Vana, H., Jogi, P. & Ramaiah, R. A randomized controlled trial comparing different doses of intravaginal misoprostol for early pregnancy failure. Contraception. 92 , 364–365, doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.06.051 (2015).

Srikhao, N. & Tannirandorn, Y. A comparison of vaginal misoprostol 800 microg versus 400 microg for anembryonic pregnancy: a randomized comparative trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 88 (Suppl 2), S41–47 (2005).

Kovavisarach, E. & Jamnansiri, C. Intravaginal misoprostol 600 microg and 800 microg for the treatment of early pregnancy failure. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 90 , 208–212, doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.04.016 (2005).

Suchonwanit, P. Comparative study between vaginal misoprostol 200 mg and 400 mg in first trimester intrauterine fetal death and anembryonic gestation. Thai Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 11 , 263 (1999).

Tang, O. S., Schweer, H., Seyberth, H. W., Lee, S. W. & Ho, P. C. Pharmacokinetics of different routes of administration of misoprostol. Hum Reprod. 17 , 332–336, doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.2.332 (2002).

Pongsatha, S. & Tongsong, T. Randomized comparison of dry tablet insertion versus gel form of vaginal misoprostol for second trimester pregnancy termination. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 34 , 199–203, doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00757.x (2008).

Saichua, C. & Phupong, V. A randomized controlled trial comparing powdery sublingual misoprostol and sublingual misoprostol tablet for management of embryonic death or anembryonic pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 280 , 431–435, doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-0947-x (2009).

Bhattacharjee, N. et al . A randomized comparative study on vaginal administration of acetic acid-moistened versus dry misoprostol for mid-trimester pregnancy termination. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 285 , 311–316, doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1949-z (2012).

Pongsatha, S. & Tongsong, T. Randomized controlled study comparing misoprostol moistened with normal saline and with acetic acid for second-trimester pregnancy termination. Is it different? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 37 , 882–886, doi: 10.1111/jog.2011.37.issue-7 (2011).

Creinin, M. D., Carbonell, J. L., Schwartz, J. L., Varela, L. & Tanda, R. A randomized trial of the effect of moistening misoprostol before vaginal administration when used with methotrexate for abortion. Contraception. 59 , 11–16, doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(98)00142-5 (1999).

Jain, J. K. & Mishell, D. R. A comparison of misoprostol with and without laminaria tents for induction of second-trimester abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 175 , 173–177, doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70270-3 (1996).

Jmylyan, M. & Hydry, M. Comparison of the Efficacy of Castor Oil and Vaginal Misoprostol With Vaginal Misopostol Alone for Treatment of Missed Abortion. Arak Medical University Journal. 18 , 30–38 (2015).

Areerat, S. & Teerapat, C. Comparison of sublingual and vaginal misoprostol for termination of early pregnancy failure. Thai J Obstet Gynaecol. 22 , 128–136 (2014).

Mohammed, S. Oral versus vaginal misoprostol for termination of frist trimester missed abortion. MSc for Cairo University . http://www.erepository.cu.edu.eg/index.p-hp/cuth eses/thesis/view/13990 (2013).

Ngoc, N. T., Blum, J., Westheimer, E., Quan, T. T. & Winikoff, B. Medical treatment of missed abortion using misoprostol. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 87 , 138–142, doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.07.015 (2004).

Tang, O. S., Lau, W. N., Ng, E. H., Lee, S. W. & Ho, P. C. A prospective randomized repeated doses of vaginal study to compare the use of with sublingual misoprostol in the management of first trimester silent miscarriages. Hum Reprod. 18 , 176–81, doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg013 (2013).

Tang, O. S. et al . A randomized trial to compare the use of sublingual misoprostol with or without an additional 1 week course for the management of first trimester silent miscarriage. Hum Reprod. 21 , 189–92, doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei303 (2006).

Higgins, J. G. S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews of Interventions (v5.1.0). http://handbook.cochrane.org/ (2011).

Caldwell, D. M., Ades, A. E. & Higgins, J. P. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ. 331 , 897–900, doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7521.897 (2005).

Dias, S., Ades, A., Sutton, A. & Welton, N. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making. 33 , 607–617, doi: 10.1177/0272989X12458724 (2013).

Salanti, G., Ades, A. E. & Ioannidis, J. P. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 64 , 163–171, doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 (2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors who shared their valuable data for the purpose of this meta-analysis.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Hangzhou Women’s Hospital, Hangzhou, 310008, Zhejiang, China

Hang-lin Wu, Pei Wang, Qiu-meng Wang & Xiao-wen Chen

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, VMMC and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, 110029, India

Sheeba Marwah

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

H.-L.W. designed the study, conducted the article searching, and drafted the paper. P.W. conducted the article searching. Q.-M.W. and X.-W.C. analyzed and interpreted the data. S.M. revised the paper. All researchers reviewed the manuscript and participated the discussion within the review team.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hang-lin Wu .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wu, Hl., Marwah, S., Wang, P. et al. Misoprostol for medical treatment of missed abortion: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7 , 1664 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01892-0

Download citation

Received : 27 October 2016

Accepted : 05 April 2017

Published : 10 May 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01892-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The relationship between heavy metals and missed abortion: using mediation of serum hormones.

Biological Trace Element Research (2023)

Effect of obesity on the time to a successful medical abortion with misoprostol in first-trimester missed abortion

- Zekiye Soykan Sert

- Mete Bertizlioğlu

Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics (2022)

Therapie der „missed abortion“ – wo stehen wir?

- Alexander Freis

Gynäkologische Endokrinologie (2021)

Efficacy and safety of myrrh in patients with incomplete abortion: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study

- Homeira Vafaei

- Sara Ajdari

- Shohreh Roozmeh

BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies (2020)

Serum Levels of Collectins Are Sustained During Pregnancy: Surfactant Protein D Levels Are Dysregulated Prior to Missed Abortion

- Kavita Kale

- Pallavi Vishwekar

- Taruna Madan

Reproductive Sciences (2020)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Abortion policy is changing every day. Minors are the most vulnerable– and the least understood

Youth Reproductive Equity kicks off a new research agenda today on minor abortion access

ANN ARBOR – Time magazine ran a profile last summer about “Ashley,” a 13-year-old girl who went nearly mute after she was raped outside of her home in Mississippi: For weeks, she didn’t tell anyone what had happened, and with state abortion bans set into motion following the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, she had no practical options but to deliver the baby before she started seventh grade. The story was one of many that have surfaced to show the human impacts of Dobbs, the U.S. Supreme Court decision that overturned the nationwide right to abortion– but how many teens are in the position of seeking abortions they can’t obtain? How do minors learn about abortion access or decide whether and how to seek reproductive healthcare? How are they navigating and experiencing the changing landscape of abortion access, and restrictions that accrue to minors in particular? We don’t know– because those data do not exist.

Research Gap

Abortion access policy disproportionately affects adolescents, but we know strikingly little about this population. Next month will mark two years since the U.S. Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, and an ocean of research has investigated the impacts of legislation that is changing every day as states press for new policies to restrict or protect abortion access. More than 14,000 articles on “abortion after Dobbs” can be found today on Google Scholar . But the impact of these changes on minors–teens aged 17 or younger with often different legal rights – is a critical area of focus that has been largely overlooked, according to Youth Reproductive Equity, a national collaborative of researchers and clinician-scientists that today launched a report aimed to address this gap.

“Minors are a marginalized group who already face additional barriers to abortion access, have fewer protections, and receive differential treatment under the law,” said lead author Julie Maslowsky, an affiliate of the University of Michigan School of Nursing and the Population Studies Center at the Institute for Social Research. “This is a problem of equity because all people, regardless of age, are entitled to the right of bodily autonomy. It is an issue of scientific rigor because we are systematically excluding one part of the population who are impacted by changing abortion laws from our studies.”

A Research Agenda for Adolescents and Abortion

The new report, “ Adolescence Post-Dobbs: A Policy-Driven Research Agenda for Minor Adolescents and Abortion ,” presents an overview of today’s policy landscape, principles and questions for future research, and recommendations to overcome challenges that limit research and policy change for minors. The report is derived from the proceedings of an expert consensus panel representing key constituencies: Researchers, reproductive health organization leaders, clinicians, law and policy experts, and a group that is not often at the table– young people themselves.

Minors aged 17 or younger account for about 4 percent of all abortions in the formal healthcare system. We know that some 25,000 minors received abortion care each year, prior to Dobbs – but we don’t know how many were unable to obtain a wanted abortion. We know that more than two-thirds of pregnancies to minors are unintended– more than other groups, and that minors’ pregnancies were more likely to end in abortion than adults’ pregnancies, prior to Dobbs . Post- Dobbs , adolescents living in states with severe abortion restrictions or bans are expected to be less likely to access abortion than adults. Adults are more likely to be able to travel to another state or access care through telehealth or online options. In Texas– one of the first states to enact a 6-week abortion ban– adolescents showed the largest decrease in their abortion rate compared to other age groups. In the rapidly shifting state policy environment, minors are often targeted by restrictive policies – like parental consent requirements or new “abortion trafficking” laws that criminalize helping minors cross state lines for abortion access – and they are often left out of protective ones, Maslowsky said. Further, adolescents also face particular barriers to pregnancy prevention– including access to contraception and to comprehensive sex education that includes information about pregnancy prevention and abortion.

The Post- Dobbs Landscape

The Guttmacher Institute yesterday identified “attacks on youth reproductive autonomy” as a key trend in its first quarterly report on state reproductive health policy. Its recent study out last month on the characteristics of adolescents obtaining abortions in the US concluded that this population is “more vulnerable” than adults, and that adolescents navigate unique barriers to both information and logistics to access care. Multiple factors delay abortion care for this age group– including mandated counseling and waiting periods, mandated ultrasound viewing, parental involvement laws, financial barriers, transportation challenges, and limited availability of care. Compared to adults, adolescents are more likely to report not knowing they are pregnant– as some may not recognize signs of pregnancy or have more irregular cycles that make a missed period less concerning. Compared to adults, the Guttmacher study found, adolescents were more likely to report not knowing they were pregnant (57% vs. 43%), not knowing where to obtain an abortion (19% vs. 11%), or that they were looking into insurance (12% vs. 5%). The report was based on Guttmacher’s 2021-22 Abortion Patient Survey, with 6,698 respondents – but because they represent only a small percentage of the population, only 156 minors were included. In reporting the study limitations, the authors acknowledged the data were not nationally representative, the sample included too few minors to do a more comprehensive analysis of the population, and the study did not capture people who wanted abortions but were unable to travel to a facility. While important, this report showcases the prevailing challenge– there is not enough data about adolescents and abortion to provide needed information and perspectives.

Meanwhile, more than half of American adolescents, aged 13 to 19, now live in states with severely restricted or no legal abortion access.

The details of cases involving minors can be found in testimonies provided to lawmakers and in news stories that paint a picture of a policy landscape that may be confusing, hostile, frightening, and dangerous to navigate. Abortion restrictions have impacted women and girls seeking interventions for life-threatening conditions and medications used to make miscarriages safer. In a post- Dobbs case in Florida, a judge denied a 17-year-old a parental consent waiver for an abortion, citing her C-average grades. A highly publicized case just days after the SCOTUS ruling involved a rape victim who fled Ohio to seek an abortion at six-and-a-half weeks in Indianapolis; she was 10 years old .

But while experiences and anecdotes like these accumulate, researchers face particular barriers to gathering evidence about minors and struggle to gather data at scales that are sufficient for robust insights.

Research Challenges

“Minors are a major blindspot in abortion research that need to be addressed,” said Laura Lindberg of the Rutgers School of Public Health, a co-author of the Youth Reproductive Equity report. “We need research that incorporates minors’ experiences, corrects the misperception that minors aren’t competent to make decisions, and guides funders and Institutional Review Boards about feasibility and best practices to break through challenges we face in efforts to conduct needed research.”

Those challenges include small samples of minors in abortion surveillance efforts, age groupings in national data that combine minors and non-minors, research gaps on the systems and contexts involved in minor abortion information, access, and care, and limited focus on the unique experiences of minors and parents navigating those systems, according to Youth Reproductive Equity. Their report includes recommendations and research questions in four areas of policy: access to abortion, access to abortion information, parental/adult involvement, and privacy and confidentiality, a category that includes electronic record sharing and criminalization of self-managed abortion.

Implications

Filling these research gaps may help guide practitioners and policymakers in an era of legislative flux. As of February, 14 states have enacted near-total abortion bans, three states have bans under litigation, and seven have lowered their gestational threshold for abortion to 20 weeks or less. The Supreme Court will rule this year on the closely-watched case that would restrict access to the “abortion pill” mifepristone, and the invocation of 19th-century Comstock Laws in that case by conservative justices was concerning to advocates of reproductive rights. Those laws– which were inactionable under Roe– banned the mailing of “lewd” content and materials for abortion or contraception. Several states– including Oklahoma , Tennessee , Idaho , and Alabama – have moved to consider bills banning minors from crossing state lines to seek abortions without parental consent. A TV response ad entitled “ The Fugitive ,” running in Alabama, includes a scene reminiscent of A Handmaid’s Tale : A highway patrolman pulls over two frightened young women, tapping the driver-side window with a home pregnancy test. Several states will vote on abortion in the upcoming election, and reproductive rights will figure as a top issue.

“It would be useful to have a larger body of research about adolescents and minors who get abortion care in all different kinds of contexts, and all different kinds of policy environments,” said Rachel Jones, a principal research scientist at Guttmacher who focuses on domestic abortion research. Most young people do involve their parents in making decisions about pregnancy, said Jones, but it would help legislators to understand the circumstances of those who don’t. Jones said the Guttmacher study suggested minors may be less likely to opt for medication abortion, but that further research would be needed to understand the replicability and implications of that finding. Given their vulnerability, it would benefit the field if foundations were more proactive about supporting research on minors who have abortions, and the barriers they face, she said.

“Historically, young people have always been the first people dismissed when it comes to reproductive care, including abortion care,” said Kylee Sunderlin of the reproductive justice organization If/When/How , whose role as a Michigan judicial bypass lawyer is to represent pregnant minors who must ask a judge to grant the right to obtain an abortion without state-mandated parental involvement. We see this reflected in the maze of laws around the country requiring parental involvement or judicial bypass, in state bills seeking to block young people’s access to abortion, as well as in ballot measures that focus on increasing abortion access but have negotiated young people out of the expansions– as we saw in the Michigan Reproductive Health Act, she said.

“As a lawyer who relies on research for amicus briefs and policy change, I have a front row seat to the ways that the absence of impactful research on sexual and reproductive health for young people has resulted in profound harm,” said Sunderlin. “The Youth Reproductive Equity report not only shows why, in stark terms, we cannot continue to ignore young people, but it also creates a clear roadmap for equitable and actionable research to remedy this gap.”

“If we understand parent perspectives, we can better inform policies about parental involvement that are often a barrier to adolescents’ desired pregnancy outcomes and result in delays in care,” said Maslowsky. “With young people’s perspectives, we will be able to counter restrictions that are based on a non-evidence based narrative that minors aren’t mature enough to make decisions. There are many questions that need to be asked to support stakeholders, make timely decisions, and understand the long-term impacts of these new restrictions.”

“The most consequential data for the work I do supporting young people is about the harms of forced parental involvement laws, the judicial bypass process, and ultimately, what it means to force a young person into birth. Because without a supportive parent or a judicial bypass, then the state is forcing young people into the incredible trauma of forced birth,” said Sunderlin. “Restricting young people’s bodily autonomy is affirmatively harmful. I hope that by hearing this—either directly from young people or indirectly through research—that the people making decisions about young people’s lives will actually start caring about them.”

With Maslowsky and Lindberg, Emily Mann of the University of South Carolina co-authored the Youth Reproductive Equity report.

This post was written by Tevah Platt of the University of Michigan Population Studies Center at the Institute for Social Research.

- Missed miscarriage

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created Yuranga Weerakkody had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Yuranga Weerakkody had no recorded disclosures.

- Missed abortion

- Early fetal demise

- Early intrauterine fetal demise

- Early loss of pregnancy

A missed miscarriage , sometimes termed a missed abortion 3 , is a situation when there is a non-viable fetus within the uterus , without symptoms of a miscarriage .

Radiographic features

Ultrasound diagnosis of miscarriage should only be considered when either a mean gestation sac diameter is ≥25 mm with no obvious yolk sac or a fetal pole with a crown rump length of ≥7 mm without evidence of fetal cardiac activity.

Transvaginal ultrasound is the mainstay in the diagnosis of miscarriage. Once the diagnosis of miscarriage is made based on the above ultrasound criteria, the patient can then be offered different types of management depending on their clinical status and patient's choice.

Treatment and prognosis