Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

49 10.8 Conclusions

We normally use the word “conclusion” to refer to that last section or paragraph or a document. Actually, however, the word refers more to a specific type of final section. If we were going to be fussy about it, the current chapter should be called “Final Sections,” which covers all possibilities.

There are at least four ways to end a report: a summary, a true conclusion, an afterword, and nothing. Yes, it is possible to end a document with no conclusion (or “final section”) whatsoever. However, in most cases, that is a bit like slamming the phone down without even saying good bye. More often, the final section is some combination of the first three ways of ending the document.

One common way to wrap up a report is to review and summarize the high points. If your report is rather long, complex, heavily detailed, and if you want your readers to come away with the right perspective, a summary is in order. For short reports, summaries can seem absurd—the reader thinks “You’ve just told me that!” Summaries need to read as if time has passed, things have settled down, and the writer is viewing the subject from higher ground.

Figure 1: Summary-type of final section. From a report written in the 1980s.

VIII. SUMMARY

This report has shown that as the supply of fresh water decreases, desalting water will become a necessity. While a number of different methods are in competition with each other, freezing methods of desalination appear to have the greatest potential for the future. The three main freezing techniques are the direct method, the indirect method, and the hydrate method. Each has some advantage over the others, but all three freezing methods have distinct advantages over other methods of desalination. Because freezing methods operate at such low temperatures, scaling and corrosion of pipe and other equipment is greatly reduced. In non-freezing methods, corrosion is a great problem that is difficult and expensive to prevent. Freezing processes also allow the use of plastic and other protective coatings on steel equipment to prevent corrosion, a measure that cannot be taken in other methods that require high operating temperatures. Desalination, as this report has shown, requires much energy, regardless of the method. Therefore, pairing desalination plants with nuclear or solar power resources may be a necessity. Some of the expense of desalination can be offset, however . . .

“True” Conclusions

A “true” conclusion is a logical thing. For example, in the body of a report, you might present conflicting theories and explored the related data. Or you might have compared different models and brands of some product. In the conclusion, the “true” conclusion, you would present your resolution of the conflicting theories, your choice of the best model or brand—your final conclusions.

Figure 2: A “true”-conclusions final section. This type states conclusions based on the discussion contained in the body of the report. (From a report written in the 1980s.)

V. CONCLUSIONS

Solar heating can be an aid in fighting high fuel bills if planned carefully, as has been shown in preceding sections. Every home represents a different set of conditions; the best system for one home may not be the best one for next door. A salesman can make any system appear to be profitable on paper, and therefore prospective buyers must have some general knowledge about solar products. A solar heating system should have as many of the best design features as possible and still be affordable. As explained in this report, the collector should have high transmissivity and yet be durable enough to handle hail storms. Collector insulation should be at least one inch of fiberglass mat. Liquid circulating coils should be at least one inch in diameter if an open loop system is used. The control module should perform all the required functions with no added circuits. Any hot water circulating pumps should be isolated from the electric drive motor by a non-transmitting coupler of some kind. Homeowners should follow the recommendations in the guidelines section carefully. In particular, they should decide how much money they are willing to spend and then arrange their components in their order of importance. Control module designs vary the most in quality and therefore should have first priority. The collector is the second in importance, and care should be taken to ensure compatibility. Careful attention to the details of the design and selection of solar heating devices discussed in this report will enable homeowners to install efficient, productive solar heating systems.

One last possibility for ending a report involves turning to some related topic but discussing it at a very general level. Imagine that you had written a background report on some exciting new technology. In the final section, you might broaden your focus and discuss how that technology might be used, or the problems it might bring about. But the key is to keep it general—don’t force yourself into a whole new detailed section.

Figure 3: Afterword-type final section. The main body of the report discussed technical aspects of using plastics in main structural components of automobiles. This final section explores the future, looking at current developments, speculating on the impact of this trend.

VII. CONCLUSION: FUTURE TRENDS

Everyone seems to agree that the car of the future must weigh even less than today’s down-sized models. According to a recent forecast by the Arthur Anderson Company, the typical car will have lost about 1,000 pounds between 1978 and 1990 [2:40]. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates the loss of another 350 pounds by 1995. To obtain these reductions, automobile manufacturers will have find or develop composites such as fiber-reinforced plastics for the major load-bearing components, particularly the frame and drivetrain components. Ford Motor Company believes that if it is to achieve further growth in the late 1980’s, it must achieve breakthroughs in structural and semistructural load-bearing applications. Some of the breakthroughs Ford sees as needed include improvements in the use of continuous fibers, especially hybridized reinforced materials containing glass and graphite fibers. In addition, Ford hopes to develop a high speed production system for continuous fiber preforms. In the related area of composite technology, researchers at Owens Corning and Hercules are seeking the best combination of hybrid fibers for structural automotive components such as engine and transmission supports, drive shafts, and leaf springs. Tests thus far have led the vice president of Owen Corning’s Composites and Equipment Marketing Division, John B. Jenks, to predict that hybrid composites can compete with metal by the mid-1980’s for both automotive leaf springs and transmission supports. With development in these areas of plastics for automobiles, we can look forward to lighter, less expensive, and more economical cars in the next decade. Such developments might well provide the needed spark to rejuvenate America’s auto industry and to further decrease our rate of petroleum consumption.

Combinations

In practice, the preceding ways of ending reports are often combined. You can analyze final sections of reports and identify elements that summarize, elements that conclude, and elements that discuss something related but at a general level (afterwords).

Here are some possibilities for afterword-type final sections:

- Provide a brief, general look to the future; speculate on future developments.

- Explore solutions to problems that were discussed in the main body of the report.

- Discuss the operation of a mechanism or technology that was described in the main body of the report.

- Provide some cautions, guidelines, tips, or preview of advanced functions.

- Explore the economics, social implications, problems, legal aspects, advantages, disadvantages, benefits, or applications of the report subject (but only generally and briefly).

Revision Checklist for Conclusions

As you reread and revise your conclusions, watch out for problems such as the following:

- If you use an afterword-type last section, make sure you write it at a general enough level that it does not seem like yet another body section of the report.

- Avoid conclusions for which there is no basis (discussion, support) in the body of report.

- Keep final sections brief and general.

Chapter Attribution Information

This chapter was derived by Annemarie Hamlin, Chris Rubio, and Michele DeSilva, Central Oregon Community College, from Online Technical Writing by David McMurrey – CC: BY 4.0

Technical Writing Copyright © 2017 by Allison Gross; Annemarie Hamlin; Billy Merck; Chris Rubio; Jodi Naas; Megan Savage; and Michele DeSilva is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Cookies on our website

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We'd like to set additional cookies to understand how you use our site so we can improve it for everyone. Also, we'd like to serve you some cookies set by other services to show you relevant content.

- Accessibility

- Staff search

- External website

- Schools & services

- Sussex Direct

- Professional services

- Schools and services

- Engineering and Informatics

- Student handbook

- Engineering and Design

- Study guides

Guide to Technical Report Writing

- Back to previous menu

- Guide to Laboratory Writing

School of Engineering and Informatics (for staff and students)

Table of contents

1 Introduction

2 structure, 3 presentation, 4 planning the report, 5 writing the first draft, 6 revising the first draft, 7 diagrams, graphs, tables and mathematics, 8 the report layout, 10 references to diagrams, graphs, tables and equations, 11 originality and plagiarism, 12 finalising the report and proofreading, 13 the summary, 14 proofreading, 15 word processing / desktop publishing, 16 recommended reading.

A technical report is a formal report designed to convey technical information in a clear and easily accessible format. It is divided into sections which allow different readers to access different levels of information. This guide explains the commonly accepted format for a technical report; explains the purposes of the individual sections; and gives hints on how to go about drafting and refining a report in order to produce an accurate, professional document.

A technical report should contain the following sections;

| Title page | Must include the title of the report. Reports for assessment, where the word length has been specified, will often also require the summary word count and the main text word count |

| Summary | A summary of the whole report including important features, results and conclusions |

| Contents | Numbers and lists all section and subsection headings with page numbers |

| Introduction | States the objectives of the report and comments on the way the topic of the report is to be treated. Leads straight into the report itself. Must not be a copy of the introduction in a lab handout. |

| The sections which make up the body of the report | Divided into numbered and headed sections. These sections separate the different main ideas in a logical order |

| Conclusions | A short, logical summing up of the theme(s) developed in the main text |

| References | Details of published sources of material referred to or quoted in the text (including any lecture notes and URL addresses of any websites used. |

| Bibliography | Other published sources of material, including websites, not referred to in the text but useful for background or further reading. |

| Acknowledgements | List of people who helped you research or prepare the report, including your proofreaders |

| Appendices (if appropriate) | Any further material which is essential for full understanding of your report (e.g. large scale diagrams, computer code, raw data, specifications) but not required by a casual reader |

For technical reports required as part of an assessment, the following presentation guidelines are recommended;

| Script | The report must be printed single sided on white A4 paper. Hand written or dot-matrix printed reports are not acceptable. |

| Margins | All four margins must be at least 2.54 cm |

| Page numbers | Do not number the title, summary or contents pages. Number all other pages consecutively starting at 1 |

| Binding | A single staple in the top left corner or 3 staples spaced down the left hand margin. For longer reports (e.g. year 3 project report) binders may be used. |

There are some excellent textbooks contain advice about the writing process and how to begin (see Section 16 ). Here is a checklist of the main stages;

- Collect your information. Sources include laboratory handouts and lecture notes, the University Library, the reference books and journals in the Department office. Keep an accurate record of all the published references which you intend to use in your report, by noting down the following information; Journal article: author(s) title of article name of journal (italic or underlined) year of publication volume number (bold) issue number, if provided (in brackets) page numbers Book: author(s) title of book (italic or underlined) edition, if appropriate publisher year of publication N.B. the listing of recommended textbooks in section 2 contains all this information in the correct format.

- Creative phase of planning. Write down topics and ideas from your researched material in random order. Next arrange them into logical groups. Keep note of topics that do not fit into groups in case they come in useful later. Put the groups into a logical sequence which covers the topic of your report.

- Structuring the report. Using your logical sequence of grouped ideas, write out a rough outline of the report with headings and subheadings.

N.B. the listing of recommended textbooks in Section 16 contains all this information in the correct format.

Who is going to read the report? For coursework assignments, the readers might be fellow students and/or faculty markers. In professional contexts, the readers might be managers, clients, project team members. The answer will affect the content and technical level, and is a major consideration in the level of detail required in the introduction.

Begin writing with the main text, not the introduction. Follow your outline in terms of headings and subheadings. Let the ideas flow; do not worry at this stage about style, spelling or word processing. If you get stuck, go back to your outline plan and make more detailed preparatory notes to get the writing flowing again.

Make rough sketches of diagrams or graphs. Keep a numbered list of references as they are included in your writing and put any quoted material inside quotation marks (see Section 11 ).

Write the Conclusion next, followed by the Introduction. Do not write the Summary at this stage.

This is the stage at which your report will start to take shape as a professional, technical document. In revising what you have drafted you must bear in mind the following, important principle;

- the essence of a successful technical report lies in how accurately and concisely it conveys the intended information to the intended readership.

During year 1, term 1 you will be learning how to write formal English for technical communication. This includes examples of the most common pitfalls in the use of English and how to avoid them. Use what you learn and the recommended books to guide you. Most importantly, when you read through what you have written, you must ask yourself these questions;

- Does that sentence/paragraph/section say what I want and mean it to say? If not, write it in a different way.

- Are there any words/sentences/paragraphs which could be removed without affecting the information which I am trying to convey? If so, remove them.

It is often the case that technical information is most concisely and clearly conveyed by means other than words. Imagine how you would describe an electrical circuit layout using words rather than a circuit diagram. Here are some simple guidelines;

| Diagrams | Keep them simple. Draw them specifically for the report. Put small diagrams after the text reference and as close as possible to it. Think about where to place large diagrams. |

| Graphs | For detailed guidance on graph plotting, see the |

| Tables | Is a table the best way to present your information? Consider graphs, bar charts or pie charts. Dependent tables (small) can be placed within the text, even as part of a sentence. Independent tables (larger) are separated from the text with table numbers and captions. Position them as close as possible to the text reference. Complicated tables should go in an appendix. |

| Mathematics | Only use mathematics where it is the most efficient way to convey the information. Longer mathematical arguments, if they are really necessary, should go into an appendix. You will be provided with lecture handouts on the correct layout for mathematics. |

The appearance of a report is no less important than its content. An attractive, clearly organised report stands a better chance of being read. Use a standard, 12pt, font, such as Times New Roman, for the main text. Use different font sizes, bold, italic and underline where appropriate but not to excess. Too many changes of type style can look very fussy.

Use heading and sub-headings to break up the text and to guide the reader. They should be based on the logical sequence which you identified at the planning stage but with enough sub-headings to break up the material into manageable chunks. The use of numbering and type size and style can clarify the structure as follows;

| devices |

- In the main text you must always refer to any diagram, graph or table which you use.

- Label diagrams and graphs as follows; Figure 1.2 Graph of energy output as a function of wave height. In this example, the second diagram in section 1 would be referred to by "...see figure 1.2..."

- Label tables in a similar fashion; Table 3.1 Performance specifications of a range of commercially available GaAsFET devices In this example, the first table in section 3 might be referred to by "...with reference to the performance specifications provided in Table 3.1..."

- Number equations as follows; F(dB) = 10*log 10 (F) (3.6) In this example, the sixth equation in section 3 might be referred to by "...noise figure in decibels as given by eqn (3.6)..."

Whenever you make use of other people's facts or ideas, you must indicate this in the text with a number which refers to an item in the list of references. Any phrases, sentences or paragraphs which are copied unaltered must be enclosed in quotation marks and referenced by a number. Material which is not reproduced unaltered should not be in quotation marks but must still be referenced. It is not sufficient to list the sources of information at the end of the report; you must indicate the sources of information individually within the report using the reference numbering system.

Information that is not referenced is assumed to be either common knowledge or your own work or ideas; if it is not, then it is assumed to be plagiarised i.e. you have knowingly copied someone else's words, facts or ideas without reference, passing them off as your own. This is a serious offence . If the person copied from is a fellow student, then this offence is known as collusion and is equally serious. Examination boards can, and do, impose penalties for these offences ranging from loss of marks to disqualification from the award of a degree

This warning applies equally to information obtained from the Internet. It is very easy for markers to identify words and images that have been copied directly from web sites. If you do this without acknowledging the source of your information and putting the words in quotation marks then your report will be sent to the Investigating Officer and you may be called before a disciplinary panel.

Your report should now be nearly complete with an introduction, main text in sections, conclusions, properly formatted references and bibliography and any appendices. Now you must add the page numbers, contents and title pages and write the summary.

The summary, with the title, should indicate the scope of the report and give the main results and conclusions. It must be intelligible without the rest of the report. Many people may read, and refer to, a report summary but only a few may read the full report, as often happens in a professional organisation.

- Purpose - a short version of the report and a guide to the report.

- Length - short, typically not more than 100-300 words

- Content - provide information, not just a description of the report.

This refers to the checking of every aspect of a piece of written work from the content to the layout and is an absolutely necessary part of the writing process. You should acquire the habit of never sending or submitting any piece of written work, from email to course work, without at least one and preferably several processes of proofreading. In addition, it is not possible for you, as the author of a long piece of writing, to proofread accurately yourself; you are too familiar with what you have written and will not spot all the mistakes.

When you have finished your report, and before you staple it, you must check it very carefully yourself. You should then give it to someone else, e.g. one of your fellow students, to read carefully and check for any errors in content, style, structure and layout. You should record the name of this person in your acknowledgements.

| Word processing and desktop publishing packages offer great scope for endless revision of a document. This includes words, word order, style and layout. | Word processing and desktop publishing packages never make up for poor or inaccurate content |

| They allow for the incremental production of a long document in portions which are stored and combined later | They can waste a lot of time by slowing down writing and distracting the writer with the mechanics of text and graphics manipulation. |

| They can be used to make a document look stylish and professional. | Excessive use of 'cut and paste' leads to tedious repetition and sloppy writing. |

| They make the process of proofreading and revision extremely straightforward |

Two useful tips;

- Do not bother with style and formatting of a document until the penultimate or final draft.

- Do not try to get graphics finalised until the text content is complete.

- Davies J.W. Communication Skills - A Guide for Engineering and Applied Science Students (2nd ed., Prentice Hall, 2001)

- van Emden J. Effective communication for Science and Technology (Palgrave 2001)

- van Emden J. A Handbook of Writing for Engineers 2nd ed. (Macmillan 1998)

- van Emden J. and Easteal J. Technical Writing and Speaking, an Introduction (McGraw-Hill 1996)

- Pfeiffer W.S. Pocket Guide to Technical Writing (Prentice Hall 1998)

- Eisenberg A. Effective Technical Communication (McGraw-Hill 1992)

Updated and revised by the Department of Engineering & Design, November 2022

School Office: School of Engineering and Informatics, University of Sussex, Chichester 1 Room 002, Falmer, Brighton, BN1 9QJ [email protected] T 01273 (67) 8195 School Office opening hours: School Office open Monday – Friday 09:00-15:00, phone lines open Monday-Friday 09:00-17:00 School Office location [PDF 1.74MB]

Copyright © 2024, University of Sussex

Technical Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Structure Included)

A technical report can either act as a cherry on top of your project or can ruin the entire dough.

Everything depends on how you write and present it.

A technical report is a sole medium through which the audience and readers of your project can understand the entire process of your research or experimentation.

So, you basically have to write a report on how you managed to do that research, steps you followed, events that occurred, etc., taking the reader from the ideation of the process and then to the conclusion or findings.

Sounds exhausting, doesn’t it?

Well hopefully after reading this entire article, it won’t.

However, note that there is no specific standard determined to write a technical report. It depends on the type of project and the preference of your project supervisor.

With that in mind, let’s dig right in!

What is a Technical Report? (Definition)

A technical report is described as a written scientific document that conveys information about technical research in an objective and fact-based manner. This technical report consists of the three key features of a research i.e process, progress, and results associated with it.

Some common areas in which technical reports are used are agriculture, engineering, physical, and biomedical science. So, such complicated information must be conveyed by a report that is easily readable and efficient.

Now, how do we decide on the readability level?

The answer is simple – by knowing our target audience.

A technical report is considered as a product that comes with your research, like a guide for it.

You study the target audience of a product before creating it, right?

Similarly, before writing a technical report, you must keep in mind who your reader is going to be.

Whether it is professors, industry professionals, or even customers looking to buy your project – studying the target audience enables you to start structuring your report. It gives you an idea of the existing knowledge level of the reader and how much information you need to put in the report.

Many people tend to put in fewer efforts in the report than what they did in the actual research..which is only fair.

We mean, you’ve already worked so much, why should you go through the entire process again to create a report?

Well then, let’s move to the second section where we talk about why it is absolutely essential to write a technical report accompanying your project.

Read more: What is a Progress Report and How to Write One?

Importance of Writing a Technical Report

1. efficient communication.

Technical reports are used by industries to convey pertinent information to upper management. This information is then used to make crucial decisions that would impact the company in the future.

Examples of such technical reports include proposals, regulations, manuals, procedures, requests, progress reports, emails, and memos.

2. Evidence for your work

Most of the technical work is backed by software.

However, graduation projects are not.

So, if you’re a student, your technical report acts as the sole evidence of your work. It shows the steps you took for the research and glorifies your efforts for a better evaluation.

3. Organizes the data

A technical report is a concise, factual piece of information that is aligned and designed in a standard manner. It is the one place where all the data of a project is written in a compact manner that is easily understandable by a reader.

4. Tool for evaluation of your work

Professors and supervisors mainly evaluate your research project based on the technical write-up for it. If your report is accurate, clear, and comprehensible, you will surely bag a good grade.

A technical report to research is like Robin to Batman.

Best results occur when both of them work together.

So, how can you write a technical report that leaves the readers in a ‘wow’ mode? Let’s find out!

How to Write a Technical Report?

When writing a technical report, there are two approaches you can follow, depending on what suits you the best.

- Top-down approach- In this, you structure the entire report from title to sub-sections and conclusion and then start putting in the matter in the respective chapters. This allows your thought process to have a defined flow and thus helps in time management as well.

- Evolutionary delivery- This approach is suitable if you’re someone who believes in ‘go with the flow’. Here the author writes and decides as and when the work progresses. This gives you a broad thinking horizon. You can even add and edit certain parts when some new idea or inspiration strikes.

A technical report must have a defined structure that is easy to navigate and clearly portrays the objective of the report. Here is a list of pages, set in the order that you should include in your technical report.

Cover page- It is the face of your project. So, it must contain details like title, name of the author, name of the institution with its logo. It should be a simple yet eye-catching page.

Title page- In addition to all the information on the cover page, the title page also informs the reader about the status of the project. For instance, technical report part 1, final report, etc. The name of the mentor or supervisor is also mentioned on this page.

Abstract- Also referred to as the executive summary, this page gives a concise and clear overview of the project. It is written in such a manner that a person only reading the abstract can gain complete information on the project.

Preface – It is an announcement page wherein you specify that you have given due credits to all the sources and that no part of your research is plagiarised. The findings are of your own experimentation and research.

Dedication- This is an optional page when an author wants to dedicate their study to a loved one. It is a small sentence in the middle of a new page. It is mostly used in theses.

Acknowledgment- Here, you acknowledge the people parties, and institutions who helped you in the process or inspired you for the idea of it.

Table of contents – Each chapter and its subchapter is carefully divided into this section for easy navigation in the project. If you have included symbols, then a similar nomenclature page is also made. Similarly, if you’ve used a lot of graphs and tables, you need to create a separate content page for that. Each of these lists begins on a new page.

Introduction- Finally comes the introduction, marking the beginning of your project. On this page, you must clearly specify the context of the report. It includes specifying the purpose, objectives of the project, the questions you have answered in your report, and sometimes an overview of the report is also provided. Note that your conclusion should answer the objective questions.

Central Chapter(s)- Each chapter should be clearly defined with sub and sub-sub sections if needed. Every section should serve a purpose. While writing the central chapter, keep in mind the following factors:

- Clearly define the purpose of each chapter in its introduction.

- Any assumptions you are taking for this study should be mentioned. For instance, if your report is targeting globally or a specific country. There can be many assumptions in a report. Your work can be disregarded if it is not mentioned every time you talk about the topic.

- Results you portray must be verifiable and not based upon your opinion. (Big no to opinions!)

- Each conclusion drawn must be connected to some central chapter.

Conclusion- The purpose of the conclusion is to basically conclude any and everything that you talked about in your project. Mention the findings of each chapter, objectives reached, and the extent to which the given objectives were reached. Discuss the implications of the findings and the significant contribution your research made.

Appendices- They are used for complete sets of data, long mathematical formulas, tables, and figures. Items in the appendices should be mentioned in the order they were used in the project.

References- This is a very crucial part of your report. It cites the sources from which the information has been taken from. This may be figures, statistics, graphs, or word-to-word sentences. The absence of this section can pose a legal threat for you. While writing references, give due credit to the sources and show your support to other people who have studied the same genres.

Bibliography- Many people tend to get confused between references and bibliography. Let us clear it out for you. References are the actual material you take into your research, previously published by someone else. Whereas a bibliography is an account of all the data you read, got inspired from, or gained knowledge from, which is not necessarily a direct part of your research.

Style ( Pointers to remember )

Let’s take a look at the writing style you should follow while writing a technical report:

- Avoid using slang or informal words. For instance, use ‘cannot’ instead of can’t.

- Use a third-person tone and avoid using words like I, Me.

- Each sentence should be grammatically complete with an object and subject.

- Two sentences should not be linked via a comma.

- Avoid the use of passive voice.

- Tenses should be carefully employed. Use present for something that is still viable and past for something no longer applicable.

- Readers should be kept in mind while writing. Avoid giving them instructions. Your work is to make their work of evaluation easier.

- Abbreviations should be avoided and if used, the full form should be mentioned.

- Understand the difference between a numbered and bulleted list. Numbering is used when something is explained sequence-wise. Whereas bullets are used to just list out points in which sequence is not important.

- All the preliminary pages (title, abstract, preface..) should be named in small roman numerals. ( i, ii, iv..)

- All the other pages should be named in Arabic numerals (1,2,3..) thus, your report begins with 1 – on the introduction page.

- Separate long texts into small paragraphs to keep the reader engaged. A paragraph should not be more than 10 lines.

- Do not incorporate too many fonts. Use standard times new roman 12pt for the text. You can use bold for headlines.

Proofreading

If you think your work ends when the report ends, think again. Proofreading the report is a very important step. While proofreading you see your work from a reader’s point of view and you can correct any small mistakes you might have done while typing. Check everything from content to layout, and style of writing.

Presentation

Finally comes the presentation of the report in which you submit it to an evaluator.

- It should be printed single-sided on an A4 size paper. double side printing looks chaotic and messy.

- Margins should be equal throughout the report.

- You can use single staples on the left side for binding or use binders if the report is long.

AND VOILA! You’re done.

…and don’t worry, if the above process seems like too much for you, Bit.ai is here to help.

Read more: Technical Manual: What, Types & How to Create One? (Steps Included)

Bit.ai : The Ultimate Tool for Writing Technical Reports

What if we tell you that the entire structure of a technical report explained in this article is already done and designed for you!

Yes, you read that right.

With Bit.ai’s 70+ templates , all you have to do is insert your text in a pre-formatted document that has been designed to appeal to the creative nerve of the reader.

You can even add collaborators who can proofread or edit your work in real-time. You can also highlight text, @mention collaborators, and make comments!

Wait, there’s more! When you send your document to the evaluators, you can even trace who read it, how much time they spent on it, and more.

Exciting, isn’t it?

Start making your fabulous technical report with Bit.ai today!

Few technical documents templates you might be interested in:

- Status Report Template

- API Documentation

- Product Requirements Document Template

- Software Design Document Template

- Software Requirements Document Template

- UX Research Template

- Issue Tracker Template

- Release Notes Template

- Statement of Work

- Scope of Work Template

Wrap up(Conclusion)

A well structured and designed report adds credibility to your research work. You can rely on bit.ai for that part.

However, the content is still yours so remember to make it worth it.

After finishing up your report, ask yourself:

Does the abstract summarize the objectives and methods employed in the paper?

Are the objective questions answered in your conclusion?

What are the implications of the findings and how is your work making a change in the way that particular topic is read and conceived?

If you find logical answers to these, then you have done a good job!

Remember, writing isn’t an overnight process. ideas won’t just arrive. Give yourself space and time for inspiration to strike and then write it down. Good writing has no shortcuts, it takes practice.

But at least now that you’ve bit.ai in the back of your pocket, you don’t have to worry about the design and formatting!

Have you written any technical reports before? If yes, what tools did you use? Do let us know by tweeting us @bit_docs.

Further reads:

How To Create An Effective Status Report?

7 Types of Reports Your Business Certainly Needs!

What is Project Status Report Documentation?

Scientific Paper: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps and Format)

Business Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Format)

How to Write Project Reports that ‘Wow’ Your Clients? (Template Included)

Business Report: What is it & How to Write it? (Steps & Format)

Internship Cover Letter: How to Write a Perfect one?

Related posts

Team plan: what is it & how to create it, how bit.ai can improve your team collaboration, remote collaboration guide & tools for distributed team, job description: what is it & how to write it (template included), what is content planning: a complete guide (template included), how to embed google sheets within your documents.

About Bit.ai

Bit.ai is the essential next-gen workplace and document collaboration platform. that helps teams share knowledge by connecting any type of digital content. With this intuitive, cloud-based solution, anyone can work visually and collaborate in real-time while creating internal notes, team projects, knowledge bases, client-facing content, and more.

The smartest online Google Docs and Word alternative, Bit.ai is used in over 100 countries by professionals everywhere, from IT teams creating internal documentation and knowledge bases, to sales and marketing teams sharing client materials and client portals.

👉👉Click Here to Check out Bit.ai.

Recent Posts

Why blog post outlines matter and how to create the best one, maximize classroom collaboration with wikis: a teacher’s guide, how to leverage ai to transform your blog writing, how to create an internal wiki to collect and share knowledge, how to build an effective knowledge base for technical support, 9 knowledge base mistakes: what you need to know to avoid them.

7.4 Technical Reports

Longer technical reports can take on many different forms (and names), but most, such as recommendation and evaluation reports, do essentially the same thing: they provide a careful study of a situation or problem , and often recommend what should be done to improve that situation or problem .

The structural principle fundamental to these types of reports is this: you provide not only your recommendation, choice, or judgment, but also the data, analysis, discussion, and the conclusions leading to it. That way, readers can check your findings, your logic, and your conclusions to make sure your methodology was sound and that they can agree with your recommendation. Your goal is to convince the reader to agree with you by using your careful research, detailed analysis, rhetorical style, and documentation.

Composing Reports

When creating a report of any type, the general problem-solving approach works well for most technical reports; t he steps below in Table 7.4 , generally coincide with how you organize your report’s information.

| 1. Identify the | What is the “unsatisfactory situation” that needs to be improved? |

| 2. Identify the for responding to the need | What is the overall goal? What are the specific, measurable objectives any solution should achieve? What constraints must any solution adhere to? |

| 3. Determine the solution you will examine | Define the scope of your approach to the problem. Identify the possible courses of action that you will examine in your report. You might include the consequences of simply doing nothing. |

| 4. Study how well each meets the | Systematically study each option, and compare how well they meet each of the objectives you have set. Provide a systematic and quantifiable way to compare how well to solution options meet the objectives (weighted objectives chart). |

| 5. Draw based on your analysis | Based on the research presented in your discussion section, sum up your findings and give a comparative evaluation of how well each of the options meets the criteria and addresses the need. |

| 6. Formulate based on your conclusion | Indicate which course of action the reader should take to address the problem, based on your analysis of the data presented in the report. |

Structuring Reports

- INTRODUCTION : T he introduction should clearly indicate the document’s purpose. Your introduction should discuss the “unsatisfactory situation” that has given rise to this report (in other words, the reason(s) for the report), and the requirements that must be met. Your reader may also need some background. Finally, provide an overview of the contents of the report. The following section provides additional information on writing report introductions.

- TECHNICAL BACKGROUND : S ome recommendation or feasibility reports may require technical discussion in order to make the rest of the report meaningful. The dilemma with this kind of information is whether to put it in a section of its own or to fit it into the comparison sections where it is relevant. For example, a discussion of power and speed of tablet computers is going to necessitate some discussion of RAM, megahertz, and processors. Should you put that in a section that compares the tablets according to power and speed? Should you keep the comparison neat and clean, limited strictly to the comparison and the conclusion? Maybe all the technical background can be pitched in its own section—either toward the front of the report or in an appendix.

- REQUIREMENTS AND CRITERIA : A critical part of feasibility and recommendation reports is the discussion of the requirements (objectives and constraints) you’ll use to reach the final decision or recommendation. Here are some examples:

- If you’re trying to recommend a tablet computer for use by employees, your requirements are likely to involve size, cost, hard-disk storage, display quality, durability, and battery function.

- If you’re looking into the feasibility of providing every student at Linn-Benton Community College with a free transportation pass, you’d need define the basic requirements of such a program—what it would be expected to accomplish, problems that it would have to avoid, how much it would cost, and so on.

- If you’re evaluating the recent implementation of a public transit system in your area, you’d need to know what was originally expected of the program and then compare (see “Comparative Analysis” below) its actual results to those requirements.

Requirements can be defined in several ways:

Numerical Values : many requirements are stated as maximum or minimum numerical values. For example, there may be a cost requirement—the tablet should cost no more than $900.

Yes/No Values : some requirements are simply a yes-no question. Does the tablet come equipped with Bluetooth? Is the car equipped with voice recognition?

Ratings Values : in some cases, key considerations cannot be handled either with numerical values or yes/no values. For example, your organization might want a tablet that has an ease-of-use rating of at least “good” by some nationally accepted ratings group. Or you may have to assign ratings yourself.

The requirements section should also discuss how important the individual requirements are in relation to each other. Picture the typical situation where no one option is best in all categories of comparison. One option is cheaper; another has more functions; one has better ease-of-use ratings; another is known to be more durable. Set up your requirements so that they dictate a “winner” from a situation where there is no obvious winner.

- DISCUSSION OF SOLUTION OPTIONS : In certain kinds of feasibility or recommendation reports, you’ll need to explain how you narrowed the field of choices down to the ones your report focuses on. Often, this follows right after the discussion of the requirements. Your basic requirements may well narrow the field down for you. But there may be other considerations that disqualify other options—explain these as well.

Additionally, you may need to provide brief technical descriptions of the options themselves. In this description section, you provide a general discussion of the options so that readers will know something about them. The discussion at this stage is not comparative. It’s just a general orientation to the options. In the tablets example, you might want to give some brief, general specifications on each model about to be compared (see below).

- COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS : O ne of the most important parts of a feasibility or recommendation report is the comparison of the options. Remember that you include this section so that readers can follow the logic of your analysis and come up with different conclusions if they desire. This comparison can be structured using a “block” (whole-to-whole) approach, or an “alternating” (point-by-point) approach.

The comparative section should end with a conclusion that sums up the relative strengths and weaknesses of each option and indicates which option is the best choice in that particular category of comparison. Of course, it won’t always be easy to state a clear winner—you may have to qualify the conclusions in various ways, providing multiple conclusions for different conditions. *NOTE : If you were writing an evaluative report, you wouldn’t be comparing options so much as you’d be comparing the thing being evaluated against the requirements placed upon it and/or the expectations people had of it. For example, if you were evaluating your town’s new public transit system, you might compare what the initiative’s original expectations were with how effectively it has met those expectations.

- SUMMARY TABLE : A fter the individual comparisons, include a summary table that summarizes the conclusions from the comparative analysis section. Some readers are more likely to pay attention to details in a table (like the one above) than in paragraphs; however, you still have to write up a clear summary paragraph of your findings.

- CONCLUSIONS : the conclusions section of a feasibility or recommendation report ties together all of the conclusions you have already reached in each section. In other words, in this section, you restate the individual conclusions. For example, you might note which model had the best price, which had the best battery function, which was most user-friendly, and so on. You could also give a summary of the relative strengths and weakness of each option based on how well they meet the criteria.

The conclusions section must untangle all the conflicting conclusions and somehow reach the final conclusion, which is the one that states the best choice. Thus, the conclusion section first lists the primary conclusions —the simple, single-category ones. Then it must state secondary conclusions —the ones that balance conflicting primary conclusions. For example, if one tablet is the least inexpensive but has poor battery function, but another is the most expensive but has good battery function, which do you choose and why? The secondary conclusion would state the answer to this dilemma.

- RECOMMENDATIONS : the final section states recommendations and directly address the problem outlined in the introduction. These may at times seem repetitive, but remember that some readers may skip right to the recommendation section. Also, there will be some cases where there may be a best choice but you wouldn’t want to recommend it. Early in their history, laptop computers were heavy and unreliable—there may have been one model that was better than the rest, but even it was not worth having. You may want to recommend further research, a pilot project, or a re-design of one of the options discussed.

The recommendation section should outline what further work needs to be done, based solidly on the information presented previously in the report and responding directly to the needs outlined in the beginning. In some cases, you may need to recommend several ranked options based on different possibilities.

For more information on what technical reports are and how to write them, watch “ Technical Report Meaning and Explanation ” from The Audiopedia:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LzvhBAQeWOE

Additional Resources

- “ How to Write A Technical Paper ” by Michael Ernst, University of Washington

- “ Report Design ,” from Online Technical Writing

- “ Engineering Report Guidelines ” (PDF example of a style guide for engineers from Technical Writing Essentials )

| ." [License: CC BY 4.0] " " Uploaded by The Audiopedia, , 21 Mar. 2018, . |

Technical Writing at LBCC Copyright © 2020 by Will Fleming is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Conclusions

This page will support you in satisfying Writing Learning Outcome:

CONCLUSION - Provide an effective conclusion that summarizes the laboratory's purpose, processes, and key findings, and makes appropriate recommendations.

Learning Objectives

You should be able to

Identify technical audience expectations for engineering lab report conclusions.

Describe what makes a conclusion meaningful, especially to a technical audience.

Relate the idea of audience expectations to prior writing instruction.

Write meaningful conclusions for an engineering lab report.

Summarize the important contents of the laboratory report clearly, succinctly, and with sufficient specificity.

Support conclusions with the evidence presented earlier in the lab report.

What is a Meaningful Conclusion in an Engineering Lab Report?

A conclusion is meaningful if it includes a summary of the work (i.e., objective and process) as well as the key findings (i.e., the results of the work and their implications) of the lab work.

The technical audience expects the following features to make the conclusion meaningful.

Restate the objective briefly.

Restate the lab process briefly.

Restate the important results of the lab work briefly, including any significant errors.

Restate the important findings briefly to meet the objective.

Provide brief recommendations for future actions or laboratories.

What Are Some Common Mistakes Seen in Poorly Written Engineering Lab Reports?

No conclusion is included in the report.

The conclusion is missing an important part (i.e., lab o bjective and key results) of the lab.

New data or new discussion is included that was not written in the report body.

Concluding statements do not address the stated objectives of the report.

The conclusion includes opinions only rather than the facts supported by other sections of the report.

Statements are overly general without containing any meaningful takeaways.

Statements are overly specific with the detailed descriptions which are supposed to be in the body.

Sample Conclusions

Why Does the Technical Audience Value Meaningful Conclusions From Engineering Lab Reports?

The technical audience reads the lab report conclusions carefully to take away the writer’s most important information. If the conclusion is well written, they may not need to read any other part of the report or know that they want to read the rest of the report to understand important details.

How Can we Use Engineering Judgment When Drawing Lab Report Conclusions?

In the context of engineering lab reports, engineering judgment can be defined as an application of evidence (i.e., lab data) and engineering principles (i.e., theory) to make decisions. The technical audience can trust the conclusions only when they are based on accurate data. The writer should use appropriate engineering principles when investigating and discussing lab data.

Common Mistakes

The conclusion is missing an important part (i.e., key results) of the lab.

Kim, J., Kim, D., (2019) “How engineering students draw conclusions from lab reports and design project reports in junior-level engineering courses,” The Proceedings of 2019 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Tampa, FL, June 2019. https://peer.asee.org/how-engineering-students-draw-conclusions-from-lab-reports-and-design-project-reports-injunior-level-engineering-courses.pdf

“Argument Papers”, Purdue University, Purdue Online Writing Lab, Argument Papers, https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/common_writing_assignments/argument_papers/conclusions.html

“Student Writing Guide”, University of Minnesota Department of Mechanical Engineering, http://www.me.umn.edu/education/undergraduate/writing/MESWG-Lab.1.5.pdf

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

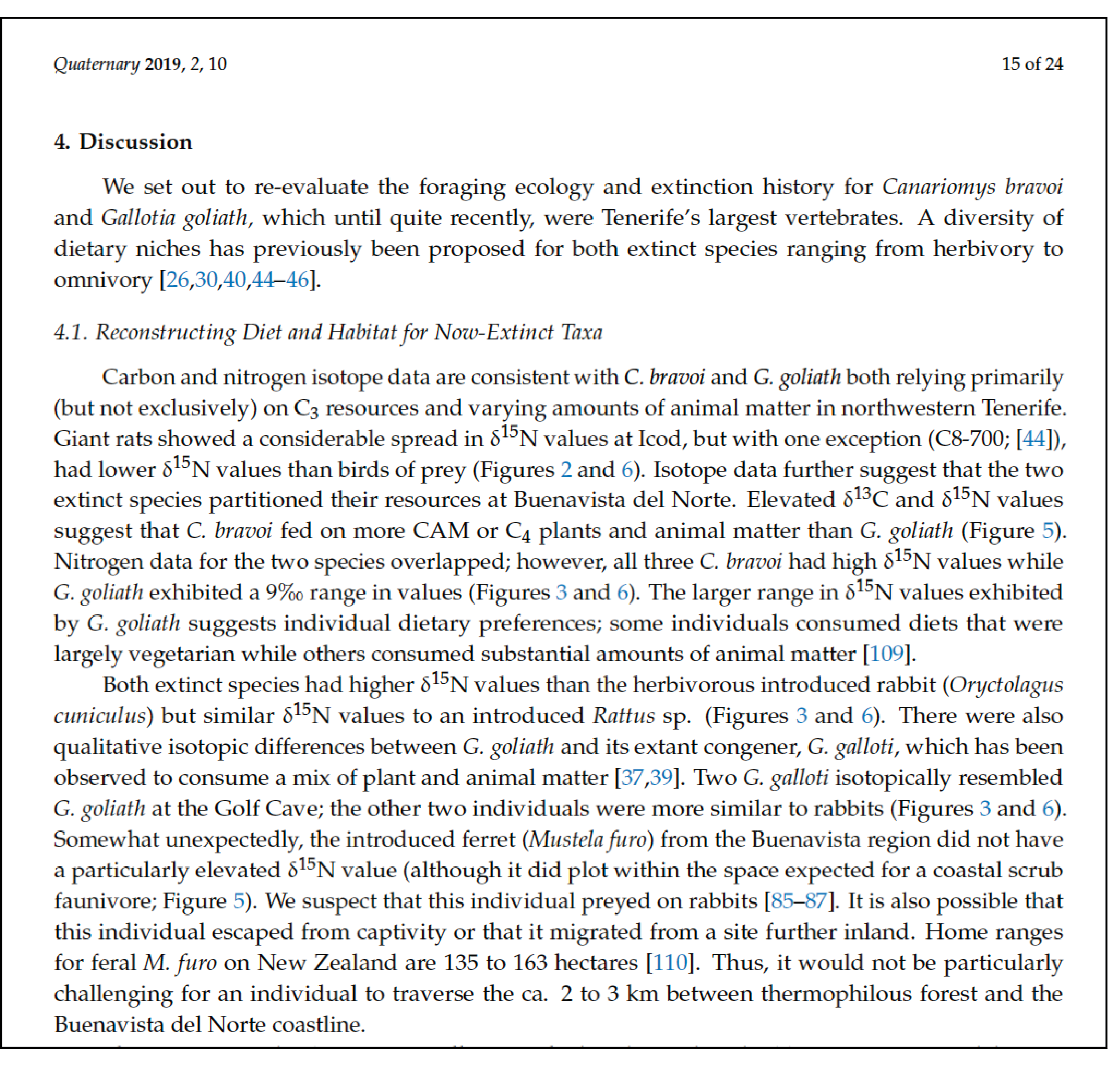

6 Writing the Discussion and Conclusion Sections

6.1 Discussion

This section discusses your results, presenting the “so what,” or “why should the reader care” about your research. This is where you explain what you think the results show. Tell the reader the significance of your document by discussing how the results fit with what is already known as you discussed in your introduction, how the results compare with what is expected, or why are there unexpected results. Here are some words to get you thinking about this section: evaluate, interpret, examine, qualify, etc.

Start by either summarizing the the information in this section or by stating the validity of the hypothesis. This allows readers to see upfront your interpretation of the data. End the discussion by summarizing why the results matter.

Writing tips:

- Summarize the most important findings at the beginning (1-3 sentences)

- Describe patterns and relationships shown in your results

- Explain how results relate to expectations and literature cited in Introduction

- Explain contradictions and exceptions

- Describe need for future research (if no Conclusion section)

- Overgeneralize, use specific supported statements

- Ignore unexpected results or deviations from your data

- Speculate conclusions that cannot be tested in the foreseeable future.

6.2 Conclusion

The Discussion usually serves as the conclusion. If there is a separate conclusion section then it should be brief, only one or two paragraphs. In the conclusion typically authors offer either recommendations or future perspectives for the research. Figs. 2.9 and 2.10 show the Discussion and Conclusion sections from the sample paper.

Technical Writing @ SLCC Copyright © 2020 by Department of English, Linguistics, and Writing Studies at SLCC is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- U of T Home

- Faculty Home

Engineering Communication Program

Conclusions

Students often have difficulty writing the Conclusion of a paper because of concerns with redundancy and about introducing new ideas at the end of the paper. While both are valid concerns, summary and looking forward (or showing future directions for the work done in the paper) are actually functions of the conclusion. The problems then become:

- How to summarize without being completely redundant

- How to look beyond the paper without jumping completely in a different direction

1. Summary: Since the conclusion’s job is to summarize the paper, some redundancy is necessary. However, you are summarizing the paper for a reader who had read the introduction and the body of the report already, and should already have a strong sense of key concepts. Your conclusion, then, is for a more informed reader and should look quite different than the introduction.

In a report on bone tissue engineering, your introduction (see Online Handbook / Components of Documents / Introductions ) and literature reviews (see Online Handbook / Components of Documents / Literature Reviews ) might discuss osteoporosis, along with current methods of treatment and their limitations at length, since this involves developing context and establishing the gap for your paper. It would even likely form a large part of the literature review. Your conclusion, however, might summarize all of this in one sentence, while identifying itself as summary (by virtue of the “as mentioned previously”):

As mentioned previously, current treatments for osteoporosis that attempt to stimulate re-growth of bone are limited because of problems delivering appropriate signaling mechanisms.

A sentence like this in the introduction would create difficulty for most readers – who would not initially know what signaling mechanisms are or what role the play in process for bone growth. But by time they reach the conclusion, the audience should know what they are, as well as the problems with current mechanisms. The above sentence might not work anywhere else in the paper – since it relies on knowledge developed throughout the paper.

Similarly, since you”ve probably spent a fair amount of time and evaluating the solution in the body of the report, a simple reference to the technology is sufficient.

Techniques involving injecting nanoparticles containing bone growth factors at the relevant areas have been shown to be effective, safe, and stable [1,2, 8-10].

This sentence relies on the audience knowing that “effectiveness,” “safety,” and “stability” are the three criteria for a successful delivery method, and also what the terms mean.

These two sentences could form the basis of your conclusion: they review the key elements of an engineering paper (see Accurate Documentation / Conducting and Understanding Research in Engineering ) by going over the situation-problem-solution-evaluation structure very briefly.

The summary could be longer. It might, for example, acknowledge the limitations of this method in current research:

However, research on the use of nanoparticles has yet to be conduct in vivo (in any applications) and bone tissue engineering is still in its infancy as a field of science.

Or, the conclusion might develop any of the above aspects in greater detail. The level of detail you engage in your summary is up to you – a conclusion can be as short as a few sentences and as long as several pages – depending on the length of the paper and the complexity of the subject matter. Prescribing a length for the conclusion is difficult, but it should not exceed 10% of the document itself, and in many cases is significant shorter.

One final note on summarizing your own writing: avoid copying and pasting sentences from the introduction or other parts of your paper into the conclusion. They won’t fit together appropriately because they were taken from a different context, and readers have a knack for spotting duplicated sentences.

2. Looking Forward: The other role of the conclusion in a scientific paper is, in fact, to introduce new avenues of potential study or to explain the potential impacts of your conclusions. This is almost an expectation in scientific papers. It should not, however, be seen as an opportunity to develop these avenues in significant detail, and should be clearly linked to the work described in your paper. In the above example, one might conclude with the following statement:

As researchers conduct more research into nanoparticles for use in drug delivery systems and bone tissue engineering matures as a field, the potential for finding a cure for osteoporosis increases. Specifically, work on matching growth factors with types of nanoparticle compounds and ways of controlling the release of these factors over time should, in the near future, turn bone tissue engineering from a field of research to an actual treatment method.

The final sentence should provide a strong take away statement that allows the audience to remember the main point of the paper – in the above example, the potential for a cure for bone disease and the work that needs to be done to achieve it.

Conclusion: In summary, the two main problems students encounter in writing conclusions are related to the two main functions of that component of a document. In summarizing the paper, the conclusion will exhibit some redundancy: the key is to aim this summary at readers who have read your report. In developing other avenues of study or application, the conclusion may have to introduce new ideas: the key here is to clearly relate these new applications or directions to the content of your report.

© 2024 Faculty of Applied Science and Engineering

- Accessibility

- Student Data Practices

- Website Feedback

Find Study Materials for

- Explanations

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

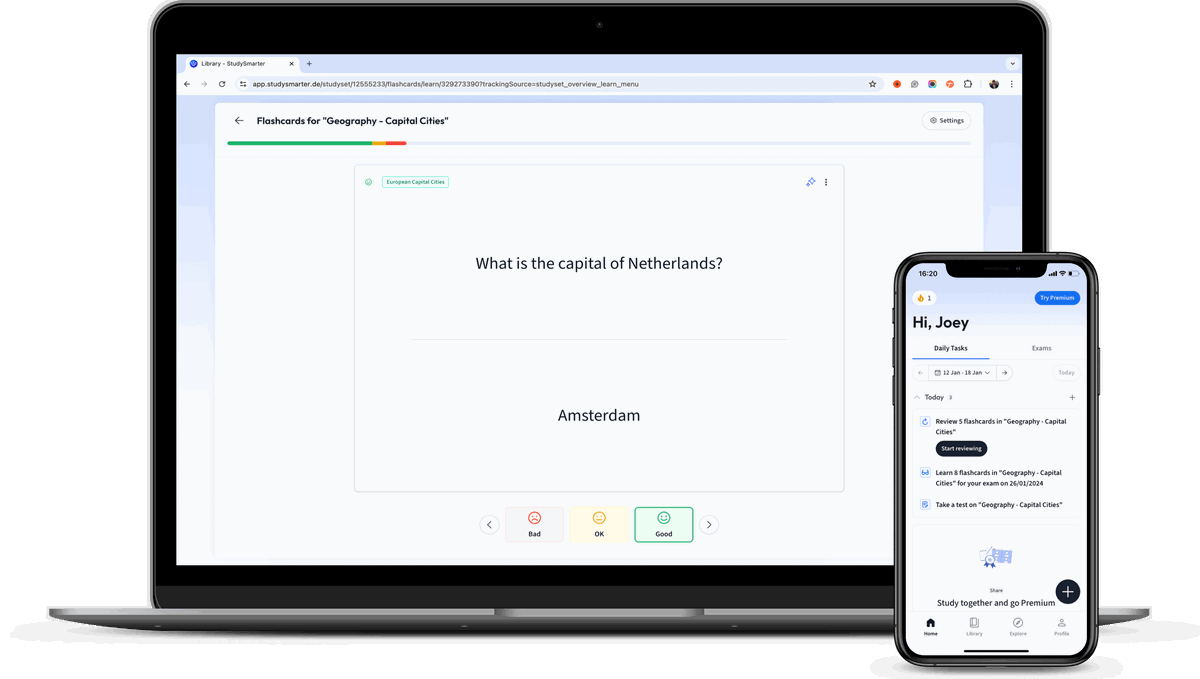

- Flashcards Create and find the best flashcards.

- Notes Create notes faster than ever before.

- Study Sets Everything you need for your studies in one place.

- Study Plans Stop procrastinating with our smart planner features.

- Technical Report

Expand your grasp of effective communication within the engineering sector as you delve into the essentials of a fundamental tool - the technical report. Gain insight into its significance, structure, varied applications across different engineering fields, and master the art of writing one with our comprehensive guide. This in-depth exploration paves the way for a deeper understanding of the concept, offering a practical advantage as you navigate your engineering career. Start your journey to becoming proficient in creating a persuasive technical report, the backbone of professional engineering communication.

Create learning materials about Technical Report with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

- Aerospace Engineering

- Design Engineering

- Engineering Fluid Mechanics

- Engineering Mathematics

- Engineering Thermodynamics

- Materials Engineering

- Professional Engineering

- Accreditation

- Activity Based Costing

- Array in Excel

- Balanced Scorecard

- Business Excellence Model

- Calibration

- Conditional Formatting

- Consumer Protection Act 1987

- Continuous Improvement

- Data Analysis in Engineering

- Data Management

- Data Visualization

- Design of Engineering Experiments

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Elements of Cost

- Embodied Energy

- End of Life Product

- Engineering Institution

- Engineering Law

- Engineering Literature Review

- Engineering Organisations

- Engineering Skills

- Environmental Management System

- Environmental Protection Act 1990

- Error Analysis

- Excel Charts

- Excel Errors

- Excel Formulas

- Excel Operators

- Finance in Engineering

- Financial Management

- Formal Organizational Structure

- Health & Safety at Work Act 1974

- Henry Mintzberg

- IF Function Excel

- INDEX MATCH Excel

- IP Licensing

- ISO 9001 Quality Manual

- Initial Public Offering

- Intellectual Property

- MAX Function Excel

- Machine Guarding

- McKinsey 7S Framework

- Measurement Techniques

- National Measurement Institute

- Network Diagram

- Organizational Strategy Engineering

- Overhead Absorption

- Part Inspection

- Porter's Value Chain

- Professional Conduct

- Professional Development

- Profit and Loss

- Project Control

- Project Life Cycle

- Project Management

- Project Risk Management

- Project Team

- Quality Tools

- Resource Constrained Project Scheduling

- Risk Analysis

- Risk Assessment

- Root Cause Analysis

- Sale of Goods Act 1979

- Situational Factors

- Six Sigma Methodology

- Sources of Error in Experiments

- Standard Cost

- Statistical Process Control

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Engineering

- Surface Texture Measurement

- Sustainable Engineering

- Sustainable Manufacturing

- Technical Presentation

- Trade Secret vs Patent

- Venture Capital

- Viable System Model

- What is Microsoft Excel

- Work Breakdown Structure

- Solid Mechanics

- What is Engineering

Understanding Technical Report: Meaning and Importance in Engineering

What is a technical report: an overview.

Technical Report: A document that describes the process, progress, or results of technical or scientific research. It also includes a detailed analysis and the conclusions drawn from that research.

- Emphasis on research methods and analysis

- Detailed technical information

- Use of jargon and technical terminology

- Targeted towards a specific technical community

| Introduction | Presents the problem, its background, and the context in which it is placed. |

| Methodology | Details the research methods and tools used. |

| Results | Outlines the results of the research. |

| Discussion | Analyzes the results obtained. |

| Conclusion | Summarizes the research and suggests future research. |

Importance of Technical Report in Professional Engineering

Beyond these practical applications, technical reports also serve a critical role in advancing the field of engineering. By sharing their findings with the technical community, engineers can stimulate innovation, inspire new research, and contribute to the evolution of engineering practices.

- Facilitates knowledge sharing within and between organizations

- Allows for the replication of successful projects

- Provides a record of failures, helping to prevent future mistakes

- Establishes a transparent, methodical approach for project documentation

Imagine an engineering project where a new type of engine is being developed. The technical report for this project wouldn't just include specifications of the engine, but a detailed description of the design process, challenges encountered, solutions implemented, and the final testing results. Without this report, the knowledge and experience gained throughout the project can be lost or misunderstood.

Breaking Down the Structure of a Technical Report

Key components of a technical report structure.

- Title Page: Includes the report title, author(s), date, and other relevant information.

- Abstract: Summarises the report in a concise paragraph, allowing readers to quickly grasp the report's purpose and findings.

- Table of Contents: Lists the report sections along with their page numbers for easy navigation.

- Introduction: Lays out the report's purpose, background information, and problem statement.

- Methodology: Details the research methods and tools used in the investigation.

- Results: Presents the findings of the investigation, usually in the form of charts, tables, or other visual data.

- Discussion: Analyses the results, drawing out their implications and responding to the problem statement.

- Conclusion: Summarises the main points and identifies potential avenues for future research.

- References: Lists the sources cited in the report.

- Appendices: Contains any additional information that supports the report, such as raw data or detailed calculations.

Comprehensive Guide to Technical Report Contents

Variations in technical report structure across different engineering fields, a walkthrough on technical report examples, technical report example in civil engineering.

- Introduction : This section presents the background information and objectives of the project. It may include clear details of the project's location, requirements, constraints and the problem statement.

- Design Principles and Calculations: The subsequent part covers the design principles adhered to, calculations, and theoretical models used. For instance, a bridge project could include structural analysis computations like: \( \text{Shear Force} = \text{Load} \times \text{distance} \)

- Materials and Methodologies: This part provides detailed information on the materials used, their properties, and why they were chosen. It also presents construction methodologies used.

- Construction Challenges and Solutions: This section explains any obstacles encountered during the construction phase along with the solutions implemented.

- Cost Analysis: A detailed breakdown of project costs is presented usually in a table format. This includes workforce costs, material costs, and other expenditures.

Technical Report Example in Electronic Engineering

- Introduction: Here, the engineer states the purpose of the project and gives some background information.

- System Design: This section explains the overall system architecture. It's where the initial design of the electronic device or circuit, the choice of components and the rationale behind these choices are explained.

- Theoretical Analysis: In this part, a step-by-step analysis of the circuit or device is conducted using theoretical concepts and mathematical models. For example, Ohm’s law may be used for circuit analysis: \( V = I \times R \).

- Simulation Results: This portion is where the results from simulated tests using software such as MATLAB or Simulink are presented and discussed.

- Physical Implementation and Challenges: The final implementation of the device or circuit is described here, alongside any glitches faced during the implementation, along with their corresponding solutions.

Technical Report Example in Mechanical Engineering

- Introduction: This is where the goal of the report, project objectives, and relevant background information are presented.

- Design and Modelling: This portion details the early design stages of the device, developed models, and any software used in this process such as AutoCAD or SolidWorks.

- Theoretical Predictions: This section deals with theoretical predictions involving calculations and formulas. For instance, for a heat engine project, Carnot's theorem may be used: \(\eta = 1 - \frac{T_c}{T_h} \).

- Manufacturing and Assembly: This is where the actual manufacturing process, assembly of the parts, and any issues encountered during this stage are documented.

- Testing: Details of how the product was tested, its performance data and analysis of the same can be found here.

Exploring Technical Report Applications in the Engineering Domain

Role of technical reports in design processes.

Feasibility studies are preliminary investigations into a proposed plan or project to assess its feasibility, time it would take to complete and cost.

How Technical Reports Facilitate Engineering Research

For example, researching the latest advancements in Bio-medical Engineering? A technical report from a leading university or technology company on a newly developed bio-medical device would be invaluable.

Technical Reports in Project Management: A Crucial Tool

Master the art of writing a technical report in 5 steps, identifying purpose and audience: step 1 in writing a technical report.

The purpose of a report refers to the primary reason a report is written. It could be for updating stakeholders, justifying a design decision, sharing research findings, or even troubleshooting a technical issue.

- What does the reader know already?

- What information will be new to them?

- What jargon or terms might need explaining?

- What do they hope to learn?

Information Gathering and Organisation: Step 2 & 3 in Writing a Technical Report

For instance, if you're working on a report, "Advances in Solar Energy", you may have to experiment with various solar panels, read articles from reputed journals, research how the leading companies in this field work, and so on.

Methodology section delivers the nuts and bolts - what you did, how you did, and why you did. In simple terms, it's your action plan.

Results: This section concentrates on factual data obtained from your work. Excel in expressing this data by deploying tables, graphs, diagrams as needed. For instance a solar power data summary could look something like this:

Drafting and Reviewing: Final Steps in Writing a Technical Report

Technical report - key takeaways.

- The meaning of a technical report: It's a detailed written document that presents the process, progress, and results of technical or scientific research.

- Technical report structure: starts with a Title Page, Abstract, and Table of Contents followed by Introduction, Methodology, Results, Discussion, Conclusion, References, and Appendices.

- Technical report applications: found in engineer design processes, project management , and engineering research providing valuable information about the project's feasibility, developments, and advancements in various fields.

- Example of a technical report: vary based on the field of engineering but usually contains an introduction, methodology, results and discussions, conclusion, and references.

- Five steps to writing a technical report: Identify the report's purpose, carry out the necessary research, organise the information logically, write the report including all necessary sections, and review, revise and proofread the report before finalising.

Flashcards in Technical Report 15

What is a technical report in the context of engineering?

A technical report is a detailed and concise document that gives an overview of the process, progress, and results of technical or scientific research, including a detailed analysis and the conclusions drawn from that research. It usually contains technical terminology and is aimed at a specific technical community.

What are some key elements within a technical report?

A technical report contains several key elements: Introduction (context of the problem), Methodology (research methods and tools used), Results (outcomes of the research), Discussion (analysis of results), and Conclusion (summary and future research suggestions). It also contains a section for experimental results.

What is the importance of technical reports in professional engineering?

Technical reports play a crucial role in engineering. They provide a detailed record of projects, facilitate knowledge sharing, allow the replication of successful projects, and help prevent future mistakes. They also contribute to innovation and the evolution of engineering practices.

What are some of the key components of a technical report structure?

A technical report typically includes: Title page, abstract, table of contents, introduction, methodology, results, discussion, conclusion, references, and appendices. These components may slightly vary depending on the nature of the report or the requirements of the specific engineering field.

What is the purpose of each component of a technical report structure?

Each component serves a specific purpose: The title page provides an overview, the abstract summarises the report, table of contents helps navigate the report, introduction provides context, methodology details the research process, results present the findings, discussion analyses the findings, conclusion summarises the report, references list the used sources, and appendices contain additional information.

Can the structure of a technical report vary across different engineering fields?

Yes, the structure of a technical report can vary slightly across different engineering fields. Specificities of the field might reflect on sections like 'Methodology'. Furthermore, the report's purpose can also influence its structure. For example, a feasibility report could have a section on 'Alternative Solutions'.

Learn with 15 Technical Report flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Technical Report

Test your knowledge with multiple choice flashcards.

Join the StudySmarter App and learn efficiently with millions of flashcards and more!

Keep learning, you are doing great.

Discover learning materials with the free StudySmarter app

About StudySmarter