Facilitating a Successful Transition to Secondary School: (How) Does it Work? A Systematic Literature Review

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 16 June 2017

- Volume 3 , pages 43–56, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Marlau van Rens 1 , 2 ,

- Carla Haelermans 1 , 2 ,

- Wim Groot 1 , 2 &

- Henriëtte Maassen van den Brink 1 , 2

39k Accesses

49 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

For children, the transition from primary to secondary school is sometimes difficult. A problematic transition can have both short- and long-term consequences. Although information from children and their parents about what concerns them can contribute to a smooth transition, this information is rarely shared during the transfer to secondary school. This review examines 30 empirical studies on the effects of interventions to ease the transition process. These are interventions which, in contrast to the usual information about curriculum and test results, focus on what children report about the transition. Our findings suggest that, although their perspectives differ, positive relationships between the stakeholders in the transition process—schools, children and their parents—can help to improve the challenges presented by the transition. It shows the importance to involve all stakeholders in the transition process. However, there is a gap in exchanging information. Little evidence is found on interventions that focus on partnership or cooperation between parents, children and schoolteachers. We conclude that children and their parents are not well represented in the decision making and in the interventions that provide information to the other stakeholders. There is a need for further research on the way children can be partners in the transition process and how they can inform other stakeholders. Researchers also must investigate how this information can be evaluated and what the consequences are for the collaboration between stakeholders in the transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Supporting children’s transition to school age care

A Systematic Review of School Transition Interventions to Improve Mental Health and Wellbeing Outcomes in Children and Young People

Research to Policy: Transition to School Position Statement

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Every year, after the summer break, many children around the world make the transition to secondary school. This is not an uncomplicated step in a child’s development because the transition is accompanied by several changes in both the school environment and in the social context. Children do not only have to get used to a larger building, the different teachers and a larger number of peers. They also have to adapt to the ways of thinking and the way you have to behave in secondary school. These changes can have positive or negative effects on children’s well-being. It has been shown that poorer school and peer transitions can have negative long- term consequences on mental health (Chung et al. 1998 ; Waters et al. 2012 ).

It is important that children can develop themselves according to their abilities. A smooth transition from primary to secondary school contributes to this. Zeedijk et al. ( 2003 ) call the transition to secondary school one of the most difficult transitions in a pupil’s educational career. Children frequently have mixed feelings about the transition. They look forward to secondary school but may also have reservations (Sirsch 2003 ). Children are looking forward to having more freedom, more challenges, and making new friends. At the same time, they are concerned about being picked on and teased by older children, having to work harder, receiving lower grades and being lost in a larger, unfamiliar school (Lucey and Reay 2000 ). Success in navigating this transition cannot only affect children’s academic performance, but also their general sense of well-being and mental health (Waters et al. 2012 ; Zeedijk et al. 2003 ).

Not only children but also society benefits from students who use their talents and do not drop out of school because of underachievement. Unnecessary absenteeism, dropout, grade retention and runoff should be avoided as much as possible (Bosch et al. 2008 ). Children who fail to make a successful transition frequently feel marginalized, unwelcomed, and not respected or valued by others. This may initiate a disengagement process from school (Roderick 1993 , in Anderson et al. 2000 ), lead to poor academic achievement and school dropout (Waters et al. 2012 ) and contribute to conflicts between the child and the school (Roderick 1993 , in Anderson et al. 2000 ).

Since the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN, 1989) was introduced, the involvement of children in decision-making has been an area of growing interest. During the past 30 years, research about self-regulated learning has become popular in educational research and has been integrated into classroom practice to help children to become independent learners (Paris and Paris 2001 ). The aim of this article is to determine what the effect is of the involvement of children in the process to ease the transition to secondary school. Although a number of publications has analyzed students’ perceptions on the transition to secondary school and has made recommendations based on the content of what students say (Ashton 2008 ; Bru et al. 2010 ; Cedzoy and Burden 2005 ), little is known about the role of children as the owners of their learning process.

The Current Study

In this article, we review the literature on the characteristics and interventions that contribute to a smooth transition. The aim of this systematic literature review is to identify empirical studies focusing on the effects of interventions to ease the transition process between primary and secondary school, especially interventions which, in contrast to the usual information about curriculum and test results, “give children a voice”. We distinguish three stakeholders involved in the transition: the children and their parents, primary schools, and secondary schools. We investigate whether children (and their parents) are involved as a partner in the transition process and if this involvement influences the transition.

Several indicators can be used to determine a successful transition. Evangelou et al. ( 2008 ) define a successful transition as consisting of the following five underlying dimensions: (1) After a successful transition children have developed new friendships and improved their self-esteem and self-confidence; (2) they are settled so well in school life that they cause no concern to their parents; (3) interest in school and schoolwork has increased compared with primary school; (4) they are used to their new routines and, (5) the school organization and they experience curriculum continuity. This definition links all stakeholders and their interests, and is therefore used for the purpose of this review.

The stakeholders, with their background characteristics, are the focus of the article. The article is structured as follows: first the factors that influence the transition are described. These are the child- and family characteristics, the preparation and support at school, and the school characteristics and peers. Then interventions that facilitate a successful transition are presented. After that, the article provides a discussion and conclusion.

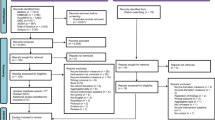

To find relevant literature about the involvement of children in the transition process, online databases Education Research Information Center (ERIC), PsychINDEX and SocINDEX were searched using the terms: transition primary secondary school; trans* primary secondary school (*indicates a wide card option so trans* extracts transition, transfer, transitional, etc.). The keywords were paired with the keywords “child* AND perspectives; child* AND perceptions; child* AND concerns; child* AND experiences”. Database Google Scholar was searched both for a free search and for a snowball search. The search of the databases revealed 202 international studies. After reading the abstracts 57 international studies remained, of which 30 articles published between 1987 and 2011 were found to be relevant. Included were peer-reviewed articles, written in Dutch, English or German and relevant to the research theme.

The main criteria for inclusion were that the study examined typically developing children making the transition to secondary school. Due to different school systems between different countries and ages that children make transitions, an age range of 11–13 was used. Studies were excluded if the children were outside that age range. Studies that focus on a-typically developing children or focus on special groups, special themes or curriculum area were also excluded. Small case studies, containing less than ten children, were excluded as well. This yielded 30 international, mostly descriptive, studies. The studies include various perspectives from parents, children, teachers and principals. They include a range of foci: aspects of the transition, children’s background and personal characteristics (gender, adjustment, well-being and self-esteem, motivation) perceptions and expectations about support, preparedness, bullying, peer and teacher relationships and parental perceptions, involvement, choices and support. Most data are collected by questionnaires and interviews.

The reviewed literature is diverse. The sample sizes differ between N = 10 and N = 7883. Questionnaires and students and teachers reports are frequently used. Most studies are descriptive and only a few studies provide solid evidence. Despite the different perspectives of the reviewed literature and the diverse assumptions of the researchers there is agreement about the key aspects which influence a successful transition. Important aspects are: the involvement of all stakeholders in the interventions and a good communication between all stakeholders (Coffey 2013 ; Green 1997 ; Jindal-Sape and; Miller 2008 ; Lester et al. 2012a ), the formation of a supporting network (Topping 2011 ), priorities for preparedness for autonomy and relatedness (Gillison et al. 2008 ) and for making relationships at secondary school, related to safety and belonging (Ashton 2008 ), awareness for gender differences (Chedzoy and Burden 2005 ; Chung et al. 1998 ) and for children who are vulnerable for a poorer transition (Chung et al. 1998 ; Jindal-Snape and Miller 2008 ; Pratt and George 2005 ; Lester et al. 2012a ; Pellegrini and Long 2002 ; Rudolph et al. 2001 ).

In the transition to secondary school, various stakeholders, who have an interest in a successful transition, are involved. All stakeholders—the children and their parents, primary- and secondary schools—have their own approaches to smoothen the transition. It was clear that the selected articles could be linked to the stakeholders and to their characteristics. Consequently, this classification is used to organise this review. We distinguished the factors that can contribute to a smooth transition and describe if and how they can lead to interventions to facilitate a successful transition.

An overview of the reviewed studies and their characteristics is presented in Table 1 . Table 1 shows, in alphabetical order, per author the theme and the main results of each study. The sample sizes and measures are also indicated.

The transition from primary to secondary school represents a significant challenge to the stakeholders who are involved in the process. The children, parents and teachers have to adapt to the new circumstances. While this process may be stressful, positive interrelationships can help to improve many of the challenges (Coffey 2013 ).

Factors Influencing the Transition

All stakeholders have their own approaches to smoothen the transition, as is shown in Fig. 1 . In this figure we distinguish the three stakeholders, with their background characteristics, who influence the transition and hence the development of the child. For children, it is important that their development continues in accordance with their capabilities. Schools have an interest in a smooth transition because it demonstrates the ability to anticipate the capacity of the feeding/primary school and the adaptive capacity of the secondary/receiving school. Primary schools prepare children to realize their academic potential at secondary school and secondary schools are responsible for curriculum continuity and continuity in attainment. The parents are positioned in the circle of the child because they are inextricably linked with the child. They are the constant factor in all development stages of the child and are ultimately responsible for the education of the child and for the choices involved (Bosch et al. 2008 ).

Stakeholders involved in the transition primary–secondary school

Child- and Family Characteristics

Adjustment difficulties to both school and peer social systems at the beginning of secondary school are related to the personal characteristics of the child (West et al. 2010 ). Changing school, especially if the child moves to a secondary school with fewer children with a similar ethnical background, may have a negative impact on children’s school career. Even children who are doing well in primary school can experience transition disruptions if their ethnic group is smaller at the secondary school (Benner and Graham 2009 , in Hanewald 2013 ). The transition can pose specific problems and concerns for children from minority cultures and can make them vulnerable for a poor transition. Socio-economic factors, socio-ethnic factors/race, gender, prior problem behavior and low academic achievement can all have an impact on the transition to secondary school (Anderson et al. 2000 ).

The factor age does not seem to influence the transition process but self-confidence and academic support do. McGee et al., find that, regardless of age, there appears to be evidence that the transition may lead to a decrease in academic attainment. This seems to be caused by the transition itself (McGee et al. 2004 ). Children, who believe that they cannot exert much influence over their success in school and who experience little academic support, report more school related stress and become more depressed when they experience a transition into secondary school, but not when they remain in the same school (Rudolph et al. 2001 ).

Personal factors, such as socioeconomic status (SES) and gender, particulary seem to be predictive factors for the perceived threat to the transition to secondary school (Sirsch 2003 ). A lower SES may lead to lower achievement (Vaz et al. 2014 ). Among children from low socio-economic (SES) households, 72% did not get used to the routines at secondary school and 58% did not settle in very well (Evangelou et al. 2008 ). Children from higher SES households had the highest score for academic competence while children from socially disadvantaged households were having the lowest scores.

Gender differences are related to subject area. Girls perceive that close friend support and school support declines during the transition period, boys self-report an increase in school problems during that period. School functioning during the transition period is a greater challenge for boys than for girls, while girls struggle to form new friendships with a new set of girls (Martinez et al. 2011 , in Hanewald 2013 ). The majority of children moving to secondary school look forward to more freedom, new challenges, other subjects, different teachers and the opportunity to make new friends. Overall, girls make the transition more easily than boys and seem to be more settled after transition (Marston 2008 , in Hanewald 2013 ).

School climate and school attachment as perceived by children themselves is correlated with misbehavior and aggressiveness. Violence and delinquency are related to negative perceptions of the school climate. Children’s positive perceptions of school climate and academic motivation are linked to teacher support (Hanewald 2013 ). Familiarity with the new school makes the transition easier (Sirsch 2003 ). Teachers and children have different perceptions of where problems lie (Topping 2011 ). Children tend to think there is a problem with the delivery of the programs while teachers tend to think that the students bring the problems with them (McGee et al. 2004 ).

Children showing high levels of psychological distress prior to transition are at a greater risk than their peers for a stressful school transition (Chung et al. 1998 ; Riglin et al. 2013 ). Boys at risk tend to show adjustment problems (academic achievement and school behavior) whereas girls at risk show more generalized adaptive difficulties following the transition (Chung et al. 1998 ). Self-esteem is related to children’s perceived social, physical and cognitive competence (Nottelmann 1987 ).

Children with lower ability and lower self-esteem have more negative school transition experiences which leads to lower levels of attainment and to higher levels of depression. Of all children 3–5% experienced depression and 3–6% was anxious (Lester et al. 2012a ). Anxious children experience peer victimization and thus poorer peer transition more frequently, which leads to lower self-esteem, more depression and anti-social behavior and therefore to a poor transition to secondary school (West et al. 2010 ). Of the children who were victimized 12–21% experienced depression and 16–22% anxiety. Increased victimization at the end of primary school led to increased depression at the beginning of secondary school. Increased depression at the end of primary school leads to increased victimization for boys (Lester et al. 2012a ).

Evangelou et al. ( 2008 ) found that children who experience a successful transition have developed friendships and boosted their self-esteem and confidence after moving to secondary school. These children have received more help from their secondary school to settle in. Most of their primary school friends move with them to the same school and they have one or more older sibling(s) at the same school. They find that the older children at their school are friendly. Children are at risk of not expanding their friendships and boosting their self-esteem and confidence if they experience bullying while in secondary school. Problems with bullying are most acute among children with special education needs (SEN) (Vaz et al. 2014 ). Of them, 37% has problems with bullying, compared with 25% of the children without SEN (Evangelou et al. 2008 ).

Children from low or medium socio-economic status (SES) households are also vulnerable for a less smooth transition into school life if they experience bullying while at secondary school (Evangelou et al. 2008 ) and are less academically competent (Vaz et al. 2014 ). Three of every ten children have experienced bullying during their live (Evangelou et al. 2008 ). Pellegrini and Long ( 2002 ) found disruptions in peer affiliations during transition to secondary school, peer victimization and increased use of aggression by boys possibly to establish peer status. The factors gender, prior problem behavior, low academic achievement, low SES and ethnicity are not independent of one another. They can be combined (and are) in many ways (Evangelou et al. 2008 ). Boys with a high level of psychological distress showed a significant decline in academic attainment and an increase in psychological distress while girls showed a significant increase in only psychological distress (Chung et al. 1998 ).

Parental involvement can affect the transition process and the school achievement before and after the transition. It can be categorized into three dimensions: direct participation, academic encouragement and expectations for attainment (Chen and Gregory 2009 , in Hanewald 2013 ). Children have a smooth transition from primary to secondary school if their parents remain a constant support, monitor their activities and intervene positively (Hanewald 2013 ). Studies in the US have shown the importance of factors at home, such as the presence of books and a place to study, for a successful transition. Parental involvement is seen as important in the transition. Parents need to maintain rules, check on homework, discuss the schoolwork, and monitor their child’s social life and academic progress (McGee et al. 2004 ). This affects children’s school achievement. If parents and schools are not on line parental support is less likely to be effective (McGee 2004 ).

Family support is also linked to achievement after transition. Both school and family should create and keep an environment for reinforcing and renewing children’s academic motivation (Kakavoulis 1998 ). Children from lower SES households often lack parental support including parental interest and participation in the school process, the extent to which they talk with their children about school, and the extent to which parents supplement the learning process with educational activities (Anderson et al. 2000 ).

Children living with both biological parents seem to perceive fewer concerns about the transition to secondary school than their peers from single-parent or blended families. It may be that intact families often have a higher quality of interactions that may prepare the children better to stressful events like the transition to secondary school (Duchesne et al. 2009 , in Hanewald 2013 ).

Preparing for a Successful Transition and Support

In many school systems, in the final grade of primary school children and their parents are advised which secondary school is the most suitable. In making this decision, three parties with desires or preferences are involved: the children, their parents and the teachers. The choice for a secondary school is determined by cognitive competences (performance, and test results), non-cognitive factors (attitudes, motivation, and interests) and the teacher’s judgments (Driessen et al. 2008 ).

Children must be prepared for a successful transition. Children who have the knowledge and skills to succeed at the next level (academic preparedness) and who are able to work by themselves and stay at the task (independence and industriousness) as well as children who conform to adult standards of behavior and effort and children who are able to cope with problems and difficulties are more likely to be successful at the next school level (Simmons and Blyth 1987 ; Ward et al. 1982 ; Snow et al. 1986 ; Timmins 1989 , in Anderson et al. 2000 ).

The literature shows that the environmental context has a stronger effect on the success or failure of a school transition than developmental characteristics (Anderson et al. 2000 ). The relative importance of the environmental context suggests the possibility that educators can contribute greatly to facilitate successful school transitions. However, few efforts have been made to do so (Anderson et al. 2000 ). One of the main features affecting a successful transition is whether children received considerable help from their secondary school. Help can include procedures to help the children to adapt and to know their way at secondary school. Schools organize induction and taster days, and offer information support and assistance by lessons and homework to help children adapt (Evangelou et al. 2008 ).

During the transition children pass through two types of discontinuities: organizational/formal (departmentalization) and social (fear of getting lost, and being victimized) (Anderson et al. 2000 ). The greater the discontinuity the child perceives, the greater the support that is needed. To help vulnerable children cope with, and even benefit from, the period of transition, we need to focus more on the social and personal experiences at this time (Jindal-Snape and Miller 2008 ). There is a need for interventions to improve social and mental health outcomes (Lester et al. 2013 ). Waters et al., ( 2012 ) suggest early detection of children who are vulnerable to a poor transition to enable support, tailored to their particular needs, to increase their connection to the new school environment to minimize the potential of long-term negative implications (Waters et al. 2012 ). Support can be informational, tangible, emotional and social. Regardless of the type of support, parents, peers and/or teachers can provide it (Anderson et al. 2000 ).

There is a consensus in the literature that well designed and implemented transition approaches can assist in the process of supporting students, their families and school staff (Hanewald 2013 ). Most schools have developed systems to ease the transition process. Their emphasis is often on administrative and organizational procedures, in contrast with children and their parents who are especially concerned with personal and social issues (Jindal-Snape and Miller 2008 ). Head teachers frequently pay little attention to peer relationships or the importance of friendship during the transition process (Pratt and George 2005 ). The sensitivity of secondary school teachers to the children’s psychosocial transfer and their awareness of the importance of social relations may well play a significant role in helping children (Chedzoy and Burden 2005 ). Attention should be paid to facilitate the formation of interpersonal relationships between children in the new school (Coffey 2013 ; Tobbell and O’Donnell 2013 ).

An important aspect in the adjustment to a new school is the students’ sense of belonging and their socio-emotional functioning (Cueto et al. 2010 , in Hanewald 2013 ). Children who feel supported by teachers are found to have a positive motivational orientation to schoolwork and to experience positive social and emotional wellbeing (Bru et al. 2010 ). Teachers’ ability to support students is a crucial element for better learning.

The Relationship Between Primary and Secondary School

Coffey ( 2013 ) finds that positive relationships and good communication channels amongst and between the stakeholders before, during and after transition are crucial to improve the transition (Coffey 2013 ). For a smooth transition, the teacher plays a critical role (Coffey 2013 ; Topping 2011 ) and sharing information concerning the child is valuable to support transitions (Chedzoy and Burden 2005 ; Green 1997 ). Nevertheless, information shared between schools is usually generic information on the curriculum rather than information about individual children (Topping 2011 ). Schools generally pay little attention to peer relationships or the importance of friendships (Pratt and George 2005 ). Information from primary to secondary school also needs to provide personal and social factors to make secondary schools alert to children who may be more vulnerable when they move (Jindal-Snape and Miller 2008 ). Although it is known that sharing information, between primary and secondary school, focused on personal and social factors smoothens the transition, less is known about the results when children receive the opportunity to participate actively during the transition trajectory by sharing information with their secondary school teachers.

McGee et al. ( 2004 ) examined schools in New Zealand and found disappointingly few contacts between primary- and secondary schools to manage the transition effectively. In schools where there was contact, it mainly concerned the transfer of information about students, familiarizing students and their parents with the secondary school, sharing facilities and teacher contacts about curriculum and teaching (McGee et al. 2004 ). One of the issues facing secondary school teachers is how much they want to know or should know about their students coming from primary school. Is it best to know very little so as to give students “a fresh start”, or is it best to be well briefed on each student? Teachers at secondary school, faced with children from a variety of feeder schools, tended to start on the same level for all children regardless of previous achievement. This resulted in a loss of continuity in the curriculum because of the transition (Huggins and Knight 1997 , in McGee et al. 2004 ).

McGee et al. ( 2004 ) found that teachers’ expectations often differ between primary and secondary school. Once at secondary school, the children experience the workload as lower, including less homework, than they had expected at primary school. This raises the question of whether primary and secondary teachers understand each other’s work and whether steps should be taken to ensure that they do (Green 1997 ) because previous experience or achievement is often disregarded by secondary schools. This corresponds to the findings from Evangelou et al. ( 2008 ) that secondary schools do not appear to trust the data on children provided by primary schools.

The Formal and the Informal Context: School Characteristics and Peers

There is no consensus about children’s experiences with the transition. On the one hand, the literature shows that most children make the transition to secondary school without difficulties but it can be stressful for some children. Most children report they expected to like going to secondary school, 15% does not expect to like their secondary school (Nottelmann 1987 ). Cedzoy and Burden found 92% of the children looking forward to the transition (Cedzoy and Burden 2005 ). Midway the first term at secondary school, 88% of the children reported to be settled (Coffey 2013 ) and at the end of the first term at secondary school one in ten children did not enjoy the transfer (Cedzoy and Burden 2005 ).

On the other hand, West et al. ( 2010 ) found that the majority of children had some difficulties in dealing effectively with the start of secondary school. A quarter found the experience very difficult. In contrast to other studies (McGee et al. 2004 ) more concerns were expressed about the formal school system than the informal system of peer relations (West et al. 2010 ). McGee et al. ( 2004 ) found that continuity of peer group appears to be associated with continuity of achievement. Low achievers at primary school may do better with a new peer group at secondary school when they are influenced positively by their new peers (McGee et al. 2004 ).

Ashton ( 2008 ) and West et al. ( 2010 ), describe that children’s school and peer concerns constitute two dimensions during the transition, the formal school-system (size of school, different teachers, work volume) and the informal social peer-system (different kids, older teenagers, bullying). Children can be successful in one area but not in the other and higher factor scores on the two dimensions represent poorer transitions.

Children in secondary schools often report a decrease in the sense of school belonging and perceived quality of school life. Children who were bully victims at primary school are more likely to feel less connected in primary school and may expect to feel less connectedness in secondary school (Lester et al. 2012a ). Green ( 1997 ) found that all children at secondary school expressed concerns about making friends. Having friends is important for the security of walking into different rooms as well as who to sit next to. When a child moves to secondary school with some known friends, knows older children at school or has sibling at the same school, some of the anxiety about making friends is alleviated (Green 1997 ). This corresponds to the findings of Pratt and George ( 2005 ), who found that the continuity and development of peer group relations and friendships was the most important factor for children.

Having friends of your own is important because loyal, “real” friends are a protection against being bullied (Mellor and Delamont 2011 ). Mellor and Delamont distinguish rational anxieties (being separated from current friends, anxieties about the curriculum, the buildings and the range of different teachers) and irrational anxieties: myths or scary stories heard from older children. Friendship can serve as a social support. Green ( 1997 ) also reports that some children were concerned about being bullied by older students. Such fears were based on rumors, spread by older students. In reality such bullying did not occur (Green 1997 ). In contrast to the findings of Green ( 1997 ), a large scale survey in 40 countries revealed 10.7% of adolescents reporting involvement in bullying (as perpetrators), 12.6% as victimized and 3.6% as bully victims (Craig et al. 2009 , in Lester et al. 2012a ). Behind the rational anxieties lies the children’s culture with irrational fears, often spread by the stories of older students (Mellor and Delamont 2011 ). The children were particularly concerned about the way in which their behavior at secondary school was perceived by their peers. They did not want to be seen as “a nerd” but rather aimed to seen as being “cool” (Green 1997 ).

Interventions to Facilitate Successful Transitions

To help children who are at risk for a poor transition, interventions that provide adequate information and social support activities, that help forming friendship networks, could be crucial. They could help children coping. Prior to the transition, at primary school, children need to be prepared for holding more responsibility for their learning. They need to learn to think about strategies for learning independently in a more challenging curriculum with clear goals of academic achievement like at secondary school (McGee et al. 2004 ). When children enter secondary school, motivation increases significantly. Both school and family should care for creating and maintaining a highly motivating environment for reinforcing and renewing children’s academic motivation (Kakavoulis 1998 ).

According to Anderson et al. ( 2000 ), interventions to facilitate a successful transition should be comprehensive, should involve parents, and receiving schools should make every effort to create a sense of community belonging (Anderson et al. 2000 ). Parents can contribute to a smooth transition by participating in their child’s schooling. When they do so the child should achieve at a higher level (Coffey 2013 ). Pellegrini and Long ( 2002 ) suggest fostering relationships during the first year of middle school by organizing social and interest-specific events. Effective lines of communication need to be established between parents and the school so that both can work effectively together for the benefit of the children (Coffey 2013 ). Green ( 1997 ) recommends an ongoing information exchange between primary and secondary teachers to facilitate the transition process and to reduce unnecessary discontinuity (Green 1997 ).

Children struggling with the transition need support, provided by multiple groups. Parents can provide support with respect to homework (Coffey 2013 ; Jindale-Sape and; Miller 2008 ; Kakavoulis 1998 ; Pellegrini and Long 2002 ). Takeing into account of existing friendships, when classifying the children, can also support children (Green 1997 ). Teachers at secondary school that are more accessible to students facilitate successful transitions. Simply being available to students is a form of teacher support. Positive peer relationships promote adjustment to the new environment, the secondary school. In supporting these peer relationships teachers can play an important role. Hamm et al. ( 2011 ) in Hanewald ( 2013 ) found that teachers more attuned to peer group affiliations promote more positive contexts and have students with improved views of their school’s social climate and adjustment during the school transition period. Coffey ( 2013 ) noted that the teacher is the key person in helping the child settle.

Lester et al. ( 2012a ) conclude that there is a need for transition programs with a focus on early-targeted interventions to minimize health risks to children from bullying and to minimize the impact on the school environment. They suggest a critical time to implement bullying intervention programs (that address peer support, connectedness to school, pro- victim attitudes and negative outcome expectancies around perpetration) is prior to the transition to, and within the first year of secondary school (Lester et al. 2012a ). Waters et al. ( 2012 ) suggest to develop an intervention based on best practice guidelines, to help children to negotiate the transition.

Many school transition interventions have a single and relatively narrow focus. Essential components of a transition model are: developing a planning team, generating goals and identifying problems, developing a written transition plan, acquiring the support of all those involved in the transition process and evaluating the process (Anderson et al. 2000 ). A focus on relationships and empathic school personnel can ensure that both child and parent concerns are acknowledged and accounted for when planning transition programs (Coffey 2013 ). Topping found that having an external supporting network is crucial for a successful transition (Topping 2011 ).

Some children are vulnerable to poor academic progression and disengagement during the first year of secondary school. Especially children with conduct problems and children who do not like school as well as boys with depressive symptoms and school concerns may need special support (Riglin et al. 2013 ). Preventively oriented school psychologists need to understand different paths of adaption to the school transition in order to identify the characteristics of children at risk and provide them with early intervention services for their specific needs (Chung et al. 1998 ).

The transition to secondary school, an important moment in the lives of young adolescents, is not always successful. Children’s personal characteristics such as ability, self-esteem, depression and anxiety, and gender, as well as family characteristics, can lead to a poorer transition. They can influence the adjustment to the school systems and to the peer/social systems (West et al. 2010 ).

The current study provides evidence about how children are involved in interventions to ease the transition and about the effect of those interventions on the transition process. In this review, we identified empirical studies, focused on the effects of characteristics and interventions to ease the transition from primary to secondary school, especially interventions that give children a voice.

For the purpose of the study we distinguished three stakeholders (children with their parents, and primary and secondary schools) involved in the transition process, who would benefit from a successful transition and can influence it by their background characteristics (Jindale-Snape and Miller 2008 ). Unfortunately, we found little evidence of educational partnership or cooperation between these stakeholders. Although educators can do a great deal to facilitate successful school transitions (Anderson et al. 2000 ), few efforts have been made to work together or to realize effective lines of communication. All stakeholders seem to approach the transition process from their own, different perspective, and adjust interventions according to their own perspectives. The effectiveness of these efforts, however, is rarely evaluated.

The influence on the transition process of school characteristics, such as differences between the primary and secondary school in the school environment and in pedagogical didactic approach, is found barely investigated in the literature. The reviewed authors just give recommendations to facilitate successful transitions, suggestions for practice and targets for school interventions. Schools do not focus as much on their emotional climate as they do on academic requirements. This is particularly remarkable because, although the literature shows the need to help children to develop their social and personal skills and to enhance their self-esteem (Ashton 2008 ; Coffey 2013 ; Gillison et al. 2008 ; Zeedijk et al. 2003 ), there is a lack of proven effective interventions in this area.

Very close links between primary and secondary school teachers are found to be essential for successful transitions (Green 1997 ; Jindale-Snape and; Miller 2008 ). These close links would make them aware of children who are vulnerable for a poor transition (Cedzoy and Burden 2005 ; Chung et al. 1998 ). In practice, this is not obvious. Teachers, who prepare children for the transition or support them after the transition, do not always have sufficient information about the children.

Family backgrounds, including cultural and socio-economic factors, can pose specific transition problems. Children from families in poverty, and from larger and lower educated families, do worse than their peers, especially when they are young compared to their classmates (Topping 2011 ). Their parents, who can be a reliable source of information about their child, are less likely to be involved in school activities and to support school (Topping 2011 ).

Little evidence is found of interventions that focus on partnership or cooperation between parents and schoolteachers during the transition process. There is an agreement about the importance of support from external networks (Topping 2011 ). In particular, the support from the family is described as extremely important (Anderson et al. 2000 ; Coffey 2013 ; Green 1997 ; Jindale-Snape and; Miller 2008 ; Lester et al. 2012a , b ; McGee et al. 2004 ) but is often neglected by schools. Parents usually do not participate in the decisions about the transition.

The involvement of children in decision making by giving them a voice has been an area of growing interest. In the literature on the transition to secondary school, the active role of the child remains somewhat underexplored as few studies have focused on the perspective of the children. The absence of any direct consultation with the children involved in the transition process demonstrates the low priority given to this aspect of transfer. It should be possible for secondary schools to learn from children by asking incoming students about their thoughts about the transition, and ask recently switched students about their experiences and what they can suggest to smoothen the transition for other children. When teachers are able to explore teaching and learning through the eyes of the children, they might be able to develop strategies based on first hand evidence.

The current study is not without of limitations. The analyses of the literature indicate that, to gain insight into the active role of children during the transition, there is a need for further research. Issues such as the way children can be partners in the transition process, how they can inform their stakeholders on an effective way and how this information can be evaluated still have to be investigated. What the consequences are for a successful transition and how the collaboration between stakeholders and educational practice at primary and secondary school can help children who are vulnerable or at risk off a poor transition also needs to be investigated.

Exploring the literature on interventions to improve the transition to secondary school, especially on interventions that give the children a voice, the results of the present study underline that positive relationships and a good communication between all stakeholders are essential to realize a successful transition (Coffey 2013 ; Green 1997 ; Jindale-Snape and; Miller 2008 ; Lester et al. 2012a ). The findings also suggest that, despite agreeing, the children (and their parents) are under-represented both in the decision making and in the interventions that provide information to the other stakeholders, the schools (McGee et al. 2004 ).

To reduce risk factors for vulnerable children and their parents, the findings underscore the need for more social and personal interventions, such as interventions that promote the interpersonal relationships with peers and the sense of belonging at secondary school (Jindale-Snape and Miller 2008 ). Knowing that the environmental context influences a successful transition more than developmental characteristics can contribute to focusing interventions toward improving the transition (Anderson et al. 2000 ). Teachers especially have the opportunity to improve the transition by encouraging the children to participate in decision-making about their transition process. Unfortunately, little effort is still being made to do so.

This study not only provides empirical support for previous studies but also contributes to increasing the awareness of policy makers, school leaders and educators of the importance to involve all stakeholders as equal partners in the interventions to improve the transition process and of the need for communication with children rather than about children. We hope that this will promote a more successful transition of young adolescents to secondary school.

Anderson, L. W., Jacobs, J., Schramm, S., & Splittgerber, F. (2000). School transitions: Beginning of the end or a new beginning? International Journal of Educational Research, 33 , 325–339.

Article Google Scholar

Ashton, R. (2008). Improving the transfer to secondary school: How every child’s voice can matter. Support for Learning, 23 (4), 176–182.

Benner, A. D., & Graham, S. (2009). The transition to high school as a developmental process among multiethnic urban youth. Child Development , 80 (2), 356–476.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bosch, M., Konermann, J., de Wit, C., Rutten, M., & Amsing, M. (2008). Passende Overgang. Een verkenning naar de stand van zaken rond de overgang tussen primair en voortgezet onderwijs . ’s Hertogenbosch: KPC Groep.

Google Scholar

Bru, E., Stornes, T., Munthe, E., & Thuen, E. (2010). Students’ perceptions of teacher support across their transition from primary to secondary school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54 (6), 519–533.

Chedzoy, S. & Burden, R. (2005). Making the move: Assessing student attitudes to primary–secondary school transfer. Research in Education, 74 , 22–35.

Chen, W. B., & Gregory, A. (2009). Parental involvement as a protective factor during the transition to high school. The Journal of Educational Research , 1003 , 53–62.

Chung, H., Elias, M., & Schneider, K. (1998). Patterns of individual adjustment changes during middle school transition. Journal of School Psychology, 36 (1), 83–101.

Coffey, A. (2013) Relationships: The key to successful transition from primary to secondary school? Improving Schools, 16 (3), 261–271.

Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, J., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dastaler, S., Hetland, J., & Simons-Morten, B. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health , 54 , S216–S224.

Cueto, S., Guerrero, G., Sugimaru, C., & Zevallos, A. M. (2010). Sense of belonging and transition to high schools in Peru. International Journal of Educational Development , 30 , 277–287.

Driessen, G., Sleegers, P., & Smit, F. (2008). The transition from primary to secondary education: meritocracy and ethnicity. European Sociological Review, 26 (4), 527–542.

Duchesne, S., Ratelle, C. F., Poitras, S.-C., & Drouin, E. (2009). Early adolescent attachment to parents, emotional problems, and teacher-academic worries about the middle school transition. The Journal of Early Adolescence , 29 (5), 743–766.

Evangelou, M., Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., & Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2008). What makes a successful transition from primary to secondary school? London: Institute of Education, University of London.

Gillison, F., Standage, M., & Skevington, S. (2008). Changes in quality of life and psychological need satisfaction following the transition to secondary school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 78 (1), 149–162.

Green, P. (1997). Moving from the world of the known to the unknown: The transition from primary to secondary school. Melbourne Studies in Education, 38 (2), 67–83.

Hamm, J. V., Farmer, T. W., Dadisman, K., Gravelle, M., & Murray, A. R. (2011). Teachers' attunement to students peer group affiliations as a source of improved student experiences of the school social-affective context following the middle school transition. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychologie , 32 , 267–277.

Hanewald, R. (2013). Transition between primary and secondary school: Why it is important and how it can be supported. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38 (1), 62–74.

Huggins, M., & Knight, P. (1997). Curriculum continuity and transfer for primary to secondary school: The case of history. Educational Studies , 23 (3), 333–348.

Jindal-Snape, D. & Miller, D. (2008). A challenge of living? Understanding the psycho-social processes of the child during primary-secondary transition through resilience and self-esteem theories. Educational Psychology Review, 20 (3), 217–236.

Kakavoulis, A. (1998). Motives for school learning during transition from primary to secondary school. Early Child Development and Care, 145 , 59–66.

Lester, L., Cross, D., Shaw, T., & Dooley, J. (2012a). Adolescent bully-victims: Social health and the transition to secondary school. Cambridge Journal of Education, 42 (2), 213–233.

Lester, L., Dooley, J., Cross, D., & Shaw, T. (2012b). Internalising symptoms: An antecedent or precedent in adolescent peer victimisation. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22 (2), 137–189.

Lester, L., Waters, S., & Cross, D. (2013). The relationship between school connectedness and mental health during the transition to secondary school: A path analyses. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 23 (2), 157–171.

Lucey, H. & Raey, D. (2000). Identities in transition: anxiety and excitement in the move to secondary school. Oxford Review of Education, 26 (2), 191–205.

Marston, J. L. (2008). Perceptions of students and parents involved in primary to secondary school transition programs. Brisbane, QLD: Australian Association for Research in Education, International Education Research Conference, 30 November–4 December.

Martinez, R. S., Aricak, O. T., Graves, M. N., Peters-Myszak, J., & Nellis, L. (2011). Changes in perceived social support and socioemotional adjustment across the elementary to junior high school transition. Youth Adolescence , 40 , 519–530.

McGee, C., Ward, R., Gibbons, J., & Harlow, A. (2004). Transition to secondary school: A literature review . Hamilton: Waikato institute for research in learning curriculum school of education, University of Waikato.

Mellor, D. & Delamont, S. (2011). Old anticipations, new anxieties? A contemporary perspective on primary to secondary transfer. Cambridge Journal of Education, 41 (3), 331–346.

Nottelmann, E. (1987). Competence and self- esteem during transition from childhood to adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 23 (3), 441–450.

Paris, S. G. & Paris, A. H. (2001). Classroom applications of research on self-regulated learning. Journal Educational Psychologist, 36 (20), 89–101.

Pellegrini, A., & Long, D. (2002). A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20 (2), 259–280.

Pratt, S. & George, R. (2005). Transferring friendship: Girls’ and boys’ friendship in the transition from primary to secondary school. Children and Society, 19 (1), 16–26.

Riglin, L., Frederickson, N., Shelton, K., & Rice, F. (2013). A longitudinal study of psychological functioning and academic attainment at the transition to secondary school. Journal of Adolescence, 36 , 2007–2017.

Roderick, M. (1993). The path of dropping out . Westport, CT: Auburn House.

Rudolph, K. D., Lambert, S. F., Clark, A. G., & Kurlakowsky, K. D. (2001). Negotiating the transition to middle school: The role of self-regulatory processes. Child Development, 72 (3), 929–946.

Simmons, R. G., & Blyth, D. A. (1987). Moving into adolescence: The impact of pubertal change and school context . Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Sirsch, U. (2003). The impending transition from primary to secondary school: Challenge or threat? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27 (5), 385–395.

Snow, W. H., Gilchrist, L., Schilling, R. F., Schinke, S. P., & Kelso, C. (1986). Preparing students for the junior high school. Journal of Early Adolescence , 6 (2), 127–137.

Timmins, M. C. (1989). Solid preparation for junior high. Perspectives for Teachers of the Hearing Impaired , 7 , 2–5.

Tobbell, J. & O’Donnell, V. (2013). The formation of interpersonal and learning relationships in the transition from primary to secondary school: Students, teachers and school context. International Journal of Educational Research, 59 , 11–23.

Topping, K. (2011). Primary–secondary transition: Differences between teachers’ and children’s perceptions. Improving Schools, 14 (3), 268–285.

Vaz, S., Parsons, R., Falkmer, T., Passmore, A., & Falkmer, M. (2014). The impact of personal background and school contextual factors on academic competence and mental health functioning across the primary-secondary school transition. PLoS One, 9 (3), e89874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089874 .

Ward, B. A., Mergendoller, J. R., Tikunoff, W. J., Rounds, T. S., Mitman, A. L., & Dadey, G. J. (1982). Junior high school transition study , Executive summary, vol. VII. San Francisco: Far West Laboratory for Educational Research and Development.

Waters, S., Lester, L., Wenden, E., & Cross, D. (2012). A theoretical grounded exploration of the social and emotional outcomes of transition to secondary school. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22 (2), 190–205.

West, P., Sweeting, H., & Young, R. (2010). Transition matters: pupils’ experiences of the primary–secondary school transition in the West of Scotland and consequences for well-being and attainment (2010). Research Articles in Education, 25 (1), 21–50.

Zeedijk, M. S., Gallacher, J., Henderson, M., Hope, G., Husband, B., & Lindsay, K. (2003). Negotiating the transition from primary to secondary school. Perceptions of pupils, parents and teachers. School Psychology International, 24 (1), 67–79.

Download references

Author Contributions

MvR conceived of the study and drafted the manuscript. CH, WG and HMvdB helped to draft the manuscript. All authors participated in the design and coordination of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

TIER, Top Institute for Evidence Based Education Research, Maastricht University, PO Box 616, 6200 MD, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Marlau van Rens, Carla Haelermans, Wim Groot & Henriëtte Maassen van den Brink

TIER, Maastricht University, Kapoenstraat 2, 6211 KW, Maastricht, The Netherlands

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marlau van Rens .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

van Rens, M., Haelermans, C., Groot, W. et al. Facilitating a Successful Transition to Secondary School: (How) Does it Work? A Systematic Literature Review. Adolescent Res Rev 3 , 43–56 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0063-2

Download citation

Received : 11 May 2017

Accepted : 01 June 2017

Published : 16 June 2017

Issue Date : March 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-017-0063-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Primary–secondary school

- Child participation

- Child voice

- Stakeholders

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Corpus ID: 68244205

Transition to secondary school: A literature review

- Clive McGee , R. Ward , +1 author A. Harlow

- Published 2003

130 Citations

Student voices: experiences of solomon islands students in transition from primary school to boarding secondary school.

- Highly Influenced

Transition: a systematic review of literature exploring the experiences of pupils moving from primary to secondary school in the UK

Factors supporting and inhibiting teachers’ use of manipulatives around the primary to post-primary education transition, supporting the transition from primary to secondary school for pupils with social, emotional and behavioural needs: a focus on the socio-emotional aspects of transfer for an adolescent boy, girls’ and boys’ perceptions of the transition from primary to secondary school, facilitating a successful transition to secondary school: (how) does it work a systematic literature review.

- 15 Excerpts

Understanding the school environments that engage and motivate young adolescents

Transfer and transitioning: students' experiences in a secondary school in trinidad and tobago.

- 13 Excerpts

Transition to Secondary School: Student Achievement and Teacher Practice

- 10 Excerpts

173 References

Transitions and the year 7 experience: a report from the 12 to 18 project.

- Highly Influential

The development of a middle school general music curriculum : a synthesis of computer-assisted instruction and music learning theory

Moving from the world of the known to the unknown: the transition from primary to secondary school, negative effects of traditional middle schools on students' motivation, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

How To Do Secondary Research or a Literature Review

- Secondary Research

- Literature Review

- Step 1: Develop topic

- Step 2: Develop your search strategy

- Step 3. Document search strategy and organize results

- Systematic Literature Review Tips

- More Information

Search our FAQ

Make a research appointment.

Schedule a personalized one-on-one research appointment with one of Galvin Library's research specialists.

What is Secondary Research?

Secondary research, also known as a literature review , preliminary research , historical research , background research , desk research , or library research , is research that analyzes or describes prior research. Rather than generating and analyzing new data, secondary research analyzes existing research results to establish the boundaries of knowledge on a topic, to identify trends or new practices, to test mathematical models or train machine learning systems, or to verify facts and figures. Secondary research is also used to justify the need for primary research as well as to justify and support other activities. For example, secondary research may be used to support a proposal to modernize a manufacturing plant, to justify the use of newly a developed treatment for cancer, to strengthen a business proposal, or to validate points made in a speech.

Why Is Secondary Research Important?

Because secondary research is used for so many purposes in so many settings, all professionals will be required to perform it at some point in their careers. For managers and entrepreneurs, regardless of the industry or profession, secondary research is a regular part of worklife, although parts of the research, such as finding the supporting documents, are often delegated to juniors in the organization. For all these reasons, it is essential to learn how to conduct secondary research, even if you are unlikely to ever conduct primary research.

Secondary research is also essential if your main goal is primary research. Research funding is obtained only by using secondary research to show the need for the primary research you want to conduct. In fact, primary research depends on secondary research to prove that it is indeed new and original research and not just a rehash or replication of somebody else’s work.

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Dec 21, 2023 3:46 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/litreview

- Skip to main content

- Accessibility help

Information

We use cookies to collect anonymous data to help us improve your site browsing experience.

Click 'Accept all cookies' to agree to all cookies that collect anonymous data. To only allow the cookies that make the site work, click 'Use essential cookies only.' Visit 'Set cookie preferences' to control specific cookies.

Your cookie preferences have been saved. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

Primary to secondary school transitions: systematic literature review - key findings

Impact of transitions and the factors that support or hinder a successful transition from primary to secondary school.

Primary-Secondary Transitions: A Systematic Literature Review

This report highlights key findings from a systematic literature review on the primary to secondary transition, undertaken by the University of Dundee. The review aimed to provide insight into the impact of transitions and the factors that support or hinder a successful transition. The document is of particular interest to policy makers and professionals working in education.

Main Findings

The key findings from the systematic literature are discussed in terms of the research questions.

Research Question 1: What does the evidence from the UK and other countries suggest about the impact of the primary to secondary transition on educational outcomes and wellbeing?

Most studies report that the transition from primary to secondary school is associated with a decline in educational attainment . However, there are important methodological limitations of existing research. Researchers note that it is difficult to disentangle the impact of other factors, such as socio-economic background, which are known to impact on attainment.

There is some evidence that pupils actually adjust, at least in wellbeing terms after an initial decline in wellbeing outcomes, relatively quickly to the transition. Nevertheless, the transition can impact negatively on perceived school belongingness.

Due to the research design deployed in most studies, we do not know the long-term impact of the primary-secondary transition, or if these effects are sustained as most studies did not collect data beyond the immediate period of starting secondary school.

Research Question 2: What does the research suggest about the experiences of children and young people during their transition from primary to secondary?

Pupils and parents are primarily concerned with changes in relationships during the transition from primary to secondary school.

Several studies have explored peer-related concerns, finding that whilst this is often a primary concern of pupils, the transition can also have a positive effect on opportunities for establishing new friendships. Concerns relating to teacher relationships are also reported by pupils. Whilst pupils may initially respond positively to the opportunities for new relationships with teachers and peers, the effect does not appear to be long lasting.

There is some evidence that a lack of fit between pupils’ development stage and the school environment may impact on how pupils experience the transition from primary to secondary.

Other studies have reported on academic concerns experienced by children. Some have found that pupils experience the changes around curriculum, homework and assessment positive, whilst others find the volume of homework to be problematic.

Most studies suggest that pupils experience a dip in school engagement and motivation in secondary schools, however it is not clear whether this is due to the transition itself or other developmental changes.

Research Question 3: What are the key factors that make a positive or negative contribution to the primary-secondary transition?

The review found that there are a number of individual, interpersonal and school level factors that can support or hinder the transition from primary to secondary school. Overall, the key factors which make a positive or negative contribution to the primary to secondary transition are those situated within the pupil’s ecological system, such as the pupils themselves, family, teachers, peers, and environmental and school factors.

To date, no research has comprehensively explored all these factors within the same study. It is therefore difficult to determine how and to what extent they support or hinder the primary to secondary transition.

Research Question 4: What does the evidence suggest about the differential impact of transition on children facing additional educational barriers such as poverty or additional support needs?

Overall, there exists little research on the differential impact of transition on children facing additional educational barriers.

However, researchers do suggest that children with additional support needs may experience a more difficult transition. There is also evidence that these pupils, and their families, may benefit from differentiated support during the transition from primary to secondary.

Research Question 5: What does international evidence suggest about the characteristics of educational systems that support or hinder the transitional experience?

Most of the research around the characteristics of educational systems that impact on the transition from primary to secondary school provides inconclusive findings.

Existing literature has explored: age at transition; impact of Independent vs public schools; size of school; the impact of through schools versus schools requiring transition to secondary school; and the effect of one primary school or multiple primary schools feeding into a secondary school.

Regardless of these characteristics, a supportive and safe school environment which involves pupils in the transition process was important for smooth transitions.

Methodology

The review was undertaken in accordance with the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre ( EPPI -Centre, 2010) approach to systematic literature reviews.

We searched multiple databases in the Web of Science ( WoS ) - Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts & Humanities Citation Index; Education Resources Information Centre ( ERIC ); from the British Education Index ( BEI ); PsycINFO and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts ( ASSIA ). Key journals in the field such as British Educational Research Journal, and the American Educational Research Journal were scanned,and key and eminent researchers in the field were contacted. Each piece of literature was screened against the inclusion criteria developed when scoping the review. EPPI -Centre weight of evidence ( WoE ) judgments were applied to each of the included studies. After a multiple stage review process, 96 studies were included in this report from the inially identified 4652 studies.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection

Conclusions & Recommendations

There was robust evidence to indicate a decline in pupils’ educational outcomes after they moved to secondary school, along with declines in motivation, school engagement and attitudes towards some subjects, and an increase in levels of school absence. Similarly, there was evidence of a negative impact on wellbeing, including poorer social and emotional health, and higher levels of depression and anxiety. However, whether this impact was as a result of the transition to secondary school and what proportion of pupils experienced this decline were less clear. Further, the link between educational and wellbeing outcomes is not clear.

Recommendations for policy and practice

- Schools transition practices should support the development of a sense of school belonging; this is important for pupils’ educational and wellbeing outcomes.

- Both primary and secondary schools should support pupils in developing strong peer networks through planned activities.

- Schools should provide opportunities which enable pupils to form secure attachments with a number of professionals in primary and secondary schools.

- Ongoing dialogue is required between primary and secondary schools, as well as within secondary schools, to ensure that there is continuity of pedagogical approach.

- The school curriculum and teachers’ pedagogical approach should encourage problem based learning and learning of emotional and social skills.

- The discourse around primary-secondary transitions at national level should also include a focus on positive outcomes.

- Parents should be involved as equal partners in transition planning and preparation.

- Schools should appropriately tailor their transition processes for pupils with additional support needs and be mindful that transitions can trigger additional support needs for some.

Recommendations for future research

- A longitudinal design, capturing data from P6 to S2 should be used.

- Research questions and data collection instruments should focus on both positive and negative aspects of transition.

- Data should be collected from all stakeholders, and should focus on the transitions of everyone.

- In order to disentangle the impact of different factors on the transition to secondary school, research should explore the transition experience across a range of pupils and various education systems.

How to access background or source data

The full report containing all background detail and analysis can be found online at: www.gov.scot/primary-secondary-transitions-report

There is a problem

Thanks for your feedback

Your feedback helps us to improve this website. Do not give any personal information because we cannot reply to you directly.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Problem Behaviours Of Adolescents Of Secondary Schools: A Review

The present article is a review to understand the major dimensions of problem behaviour amongst the adolescent students of secondary schools in classroom and school situations. Problem behaviours amongst adolescent students affect the goals of effective teaching and learning. It leads to lost class and precious study time and at times leads to expulsion from school. Review of the literature found that problem behaviour of adolescent students studying in secondary schools manifest in the form of aggressive-disruptive behaviour, attention deficit disorders, learning difficulties, and various internalizing disorders including social withdrawal, social isolation etc. Fighting, different forms of violence, bullying, lack of concentration, impulsivity, truancy, lying, stealing, smoking and drinking during school hours, use of drugs and alcohol, sneaking out of school, arguing, teasing and tormenting classmates, interfering with others' works, disrespecting elders and teachers, cheating, disobedience and many more such behaviours are reported from the schools all over the world. Basing on the review, major dimensions of problem behaviours were classified as Problem

Related Papers

International Journal of Scientific Research

jeryda anand

Fariha Iram

Present study was conducted to find the profiles and patterns of emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents from general population who had never been reported or diagnosed. A sample of 300 adolescents from public and private schools of Lahore, (13 to 17 years old, Mean=14.8) participated in the study. Participants completed the self-report standardized questionnaires, Youth Self-Report (YSR: Achenbach, & Rescorla, 2001) in Urdu language. The study revealed that majority of the adolescents was found to have normal behavior but a noticeable number of adolescents show emotional and behavioral problems. About 2 to 15% adolescents were found in clinical range and 3 to 10% in border line range of problems. Findings also suggest that in broadband scales externalizing problems were most prevalent in adolescents i.e. 15% and among DSM oriented problems conduct problem and anxiety problem were found most common in adolescents.

Adolescence is a period of stress and storm where both boys and girls face many challenges in their lives. Adolescent students spend nearly eight hours in the school for their academic development. Hence school plays a vital role in moulding the personality of each individual. Hence, the present study aims to know and compare the level of student’s problem of adolescent boys and girls and emphasizes the need for life skills by adopting Descriptive Research Design. The researcher will administer Students Problem Inventory developed by Dr. Harkant Badami in 1977 and the reliability coefficient is 0.832.Hence the researcher has selected one boy’s school and one girl’s school for the study. The universe of the study consist of 400 students studying in IX standard and the researcher collected data from 200 students(boys – 100, Girls – 100) by using stratified proportionate sampling method and data will be analyzed and necessary life skills Intervention will be suggested to promote well being of school students.

Dr.Gladys Colaco

Psycho-social problems have been identified as vital among adolescents at particular times when they enter the Pre-University. The various reasons were examination stress, personal and family life events. Psychosocial health problems are one of the hidden public health problems amongst the children and adolescents. Early identification, diagnosis and interventions are very important for preventing further complications. The aim of the study is to assess the psycho-social problems among adolescent students of selected Pre-University colleges. Taking 286 adolescent students from 3 Pre University Colleges of Belthangady Taluk of Dakshina Kannada district were selected through purposive sampling method. A set of structured questionnaire and Y-PSC was adopted to collect data, which were analyzed using SPSS software. Out of 286 adolescent students 25.5% were suffering with psychosocial dysfunction. Female students (17.5%) were more affected, compared to male students (8%). The psycho-soci...

International Research Journal Commerce arts science

Adolescents are highly vulnerable to psychiatric disorders. This study aimed to explore the prevalence and patterns of behavioural and emotional problems in adolescents. It was also aimed to explore associations between socio environmental stressors and maladaptive outcomes. A school based cross-sectional study was conducted between January and July 2008. A stratified random sampling was done. 1150 adolescents in 12 to 18 year age group in grades 7 to 12 in 10 co-educational schools (government run and private) were the subjects of the study. Behavioural and emotional problems were assessed using Youth Self-Report (2001) questionnaire. Family stressors were assessed using a pre-tested 23 item questionnaire. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed. Multiple logistic regression analysis was also done.

Guru Journal of Behavioral and Social Sciences

Increasing independence from adult controls, rapidly occurring physical and psychological changes, exploration of social issues and concerns, increased focus on activities with a peer group and establishment of a basic self identity contribute to adolescent maladjustment. Factors for adolescent maladjustment include economic instability, parental discord, inadequacy of school offerings, lack of understanding of adolescent psychology on the part of parents and school faculties, and inadequate recreational facilities. This study on psycho-social problems of adolescents with 600 higher secondary students will help the parents, teachers, teacher educators and even the public to be familiar with the problems of adolescents. Findings reveal that adolescents at higher secondary level face more problems from educational and emotional aspects.

Publisher ijmra.us UGC Approved

Education plays very important role in making the man well adjusted in the society. Education in real sense , is to humanize humanity and to make life progressive , cultured and civilized. Everyone want to adjust himself with his environment. The modern education has these objectives. But it is also true that every individual do not have the same potentialities to adjust himself and now a days it is a major problem in our educational institution as well as in our society. The study was conducted with 50 male and female students among the secondary level. For this study a general information schedule , questionnaire and a checklist was formed. The study highlighted the common behavioural problems among the students. It has been found from the study that female students and male students have the different maladjustment problems. The study will provide the knowledge about the different types of maladjustment and their relative causes among secondary level students. It will be helpful for the teacher to understand and overcome different related problems .

Abdul Malek Abdul Rahman

The objective of this study is to examine the phenomenon of aggressive behavior among teenagers; the profile of aggressive teenagers in school; pattern and frequency of aggressive behavior among teenagers in school; measuring psychological preferences in aggressive behavior among teenagers. The number of respondents were 14,520 based on gender, Forms, type of school and area. Male and female students ranging from Form 1, 2 and 4 were taken as samples for the study. The location of the study was divided into five zones i.e. the North Zone, East Zone, Central Zone, South Zone, Zone of Sabah and Zone of Sarawak. Three types of schools involved in the study were the secondary school (SMK), boarding school (SBP) and religious secondary school (SMKA).

International Journal of Case Studies in Business, IT, and Education (IJCSBE)